Recently I’ve been trying to make a new Btrfs filesystem for rolling Borg backups.

Unfortunately after creating a new filesystem I can mount it, but then after unmaount it on for the first time, it’s impossible to mount the second time. dmesg says this:

[pią mar 18 22:46:22 2022] BTRFS info (device sdf1): flagging fs with big metadata feature

[pią mar 18 22:46:22 2022] BTRFS info (device sdf1): enabling disk space caching

[pią mar 18 22:46:22 2022] BTRFS info (device sdf1): setting incompat feature flag for COMPRESS_ZSTD (0x10)

[pią mar 18 22:46:22 2022] BTRFS info (device sdf1): force zstd compression, level 3

[pią mar 18 22:46:22 2022] BTRFS error (device sdf1): cannot disable free space tree

[pią mar 18 22:46:22 2022] BTRFS error (device sdf1): open_ctree failed

I have never had this kind of problem before — I assume this is a bug that was introduced in a recent kernel update on Arch Linux (I’m running kernel 5.16.15-arch1-1 right now).

I really hope this can be resolved quickly, as all my data is stored on Btrfs filesystems and having something like this happening is quite unnerving.

What can I do about this?

From Forza’s ramblings

Improving Copy-on-Write performance

Red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) searching for cached nuts.

Copy-on-Write (CoW) means that the filesystem never overwrites existing data in-place, but instead it writes new data on empty locations. Once the data is written, Btrfs updates the metadata trees to point to the newly written data. This means if there is a crash or power outage, the filesystem will remain intact and no data will remain «half-written» — the filesystem will either have all the old data or all the new data depending on when the crash occurred.

Because of the need to quickly find empty areas to write to, Btrfs keeps track on where on-disk there is free space to write new data. Btrfs solves this by creating a special cache of all the free space on the filesystem. Without this cache, the write performance would suffer greatly.

Space Cache and the Free Space Tree (space_cache=v2)

There are two versions of the Space Cache, The original v1 and then the new modern v2, which is called free space tree.

On large filesystems (many terabytes) and with certain workloads, the performance of the v1 space cache may degrade drastically. This is why the new v2 implementation was created. It uses a new B-tree called the free space tree.

Starting with btrfs-progs 5.15, the free space tree is the default for all newly created filesystems.

Space cache is a filesystem wide option and it is not possible to change this per-subvolume.

How to switch to the Free Space Tree

It is possible to change from Space Cache (v1) to the Free Space Tree (v2).

In order to switch, you have to unmount the filesystem, remove the previous space cache, then mount it with the space_cache=v2 mount option. This will be a permanent change and Btrfs will use the new Free Space Tree on all future mounts once enabled.

Removing the old v1 space cache is done with btrfs check.

# umount /mnt/btrfs # btrfs check --clear-space-cache v1 /dev/device # mount /dev/device /mnt/btrfs -o space_cache=v2

It is enough to run btrfs check --clear-space-cache v1 /dev/device on one of the disks in a multiple disk filesystem.

IMPORTANT! On very large filesystems, the first mount after changing Space Cache can take a long time. Usually several minutes, but there are reports of an hour or more for extreme cases with massive filesystems.

If you want to change your root filesystem you have to boot with a Live USB stick to be able to mount the filesystem, using the above process. The Fedora Workstation Live DVD is a good choice since it has up-to-date Linux kernels and btrfs-progs.

Note: It is possible to change the kernel rootflags in the boot loader to rw,space_cache=v2, but it could leave you with an unbootable system if there is a problem or mistake.

Switching back to Space Cache from Free Space Tree can be done in the same was as before:

# umount /mnt/btrfs # btrfs check --clear-space-cache v2 /dev/device # mount /dev/device /mnt/btrfs -o space_cache=v1

How to enable the Free Space Tree at mkfs time

With btrfs-progs 5.15 and newer, the Free Space Tree is default. There is no need to specify any special options to take advantage of the new cache.

With btrfs-progs 5.7 and later, there is the -R free-space-tree option to enable Free Space Tree as default for new filesystems at mkfs time. With this option, the kernel will automatically use the Free Space Tree without needing any mount options. There is also no need to clear any old Space Cache since it never gets created.

# mkfs.btrfs -R free-space-tree -L my-btrfs /dev/vdb1

btrfs-progs v5.13.1

See http://btrfs.wiki.kernel.org for more information.

Label: my-btrfs

UUID: 80014f0a-dd1d-4f09-ab34-7adeb27585df

Node size: 16384

Sector size: 4096

Filesystem size: 512.00GiB

Block group profiles:

Data: single 8.00MiB

Metadata: DUP 1.00GiB

System: DUP 8.00MiB

SSD detected: no

Zoned device: no

Incompat features: extref, skinny-metadata

Runtime features: free-space-tree

Checksum: crc32c

Number of devices: 1

Devices:

ID SIZE PATH

1 512.00GiB /dev/vdb1

run «btrfs-find-root /dev/vg1/volume_1&> /mnt/iscsi/btrfs-find-root &»

parent transid verify failed on 887020683264 wanted 6011 found 6270

Ignoring transid failure

Couldn't setup extent tree

Couldn't setup device tree

Superblock thinks the generation is 6011

Superblock thinks the level is 1

Found tree root at 887014998016 gen 6011 level 1

Well block 448900530176(gen: 7903 level: 0) seems good, but generation/level doesn't match, want gen: 6011 level: 1

Well block 777465511936(gen: 7844 level: 0) seems good, but generation/level doesn't match, want gen: 6011 level: 1

Well block 503614685184(gen: 7412 level: 0) seems good, but generation/level doesn't match, want gen: 6011 level: 1

Well block 470875013120(gen: 7343 level: 0) seems good, but generation/level doesn't match, want gen: 6011 level: 1

Well block 470870278144(gen: 7341 level: 0) seems good, but generation/level doesn't match, want gen: 6011 level: 1

Well block 471096754176(gen: 7063 level: 0) seems good, but generation/level doesn't match, want gen: 6011 level: 1

Well block 471050649600(gen: 6927 level: 0) seems good, but generation/level doesn't match, want gen: 6011 level: 1

Well block 558475149312(gen: 6774 level: 0) seems good, but generation/level doesn't match, want gen: 6011 level: 1

Well block 886999793664(gen: 6567 level: 0) seems good, but generation/level doesn't match, want gen: 6011 level: 1

Well block 886999777280(gen: 6567 level: 0) seems good, but generation/level doesn't match, want gen: 6011 level: 1

Well block 470921674752(gen: 6291 level: 0) seems good, but generation/level doesn't match, want gen: 6011 level: 1

Well block 887014064128(gen: 6269 level: 0) seems good, but generation/level doesn't match, want gen: 6011 level: 1

Well block 887014031360(gen: 6269 level: 0) seems good, but generation/level doesn't match, want gen: 6011 level: 1

Well block 887014014976(gen: 6269 level: 0) seems good, but generation/level doesn't match, want gen: 6011 level: 1

Well block 887013965824(gen: 6269 level: 0) seems good, but generation/level doesn't match, want gen: 6011 level: 1

Well block 887013326848(gen: 6268 level: 0) seems good, but generation/level doesn't match, want gen: 6011 level: 1

Well block 887013294080(gen: 6268 level: 0) seems good, but generation/level doesn't match, want gen: 6011 level: 1

Well block 887013244928(gen: 6268 level: 0) seems good, but generation/level doesn't match, want gen: 6011 level: 1

Well block 887010803712(gen: 6267 level: 1) seems good, but generation/level doesn't match, want gen: 6011 level: 1

........

1

1

В dmesg заметил такую строчку:

[ 5.956971] BTRFS warning (device sde3): remount supports changing free space tree only from ro to rw

Чего ему не нравиться-то?

Яндекс не помог, поиск по форумам тоже…

cat /etc/fstab

UUID=7A58-9843 /boot/efi vfat umask=0077 0 2

UUID=457b1555-6878-4de9-a7f2-b338037a5417 swap swap defaults,noatime,pri=10 0 0

UUID=2dd11029-ec54-4bc6-ac60-963822c6c114 / btrfs subvol=/@,defaults,max_inline=256,noatime,space_cache=v2,compress-force=zstd:15,discard=async,ssd_spread 0 0

UUID=2dd11029-ec54-4bc6-ac60-963822c6c114 /home btrfs subvol=/@home,defaults,max_inline=256,noatime,space_cache=v2,compress-force=zstd:15,discard=async,ssd_spread 0 0

UUID=2dd11029-ec54-4bc6-ac60-963822c6c114 /var/cache btrfs subvol=/@cache,defaults,max_inline=256,noatime,space_cache=v2,compress-force=zstd:15,discard=async,ssd_spread 0 0

UUID=2dd11029-ec54-4bc6-ac60-963822c6c114 /var/log btrfs subvol=/@log,defaults,max_inline=256,noatime,space_cache=v2,compress-force=zstd:15,discard=async,ssd_spread 0 0

tmpfs /tmp tmpfs defaults,noatime,mode=1777 0 0

Hello,

I’ve had a RAID1 and than converted to RAID0 (on purpose, not critical data, just backups, before I buy more disks to have raid1).

However, I think that the system can’t ‘see’ all the storage. Currently I have one 1TB drive and one 3TB in RAID0 (data, metadata and system in raid1).

The problem is that if I try to copy a file via SSH it creates an empty file and instantly cancels copying without any message (via MobaXterm). On backup software (via CIFS/samba) it gets stuck in endless loop (Cobian Gravity) or finishes with an error («This operation is not supported» on Paragon) — so I think it may be because of no free space.

What has been done:

Initially there were 4 disks of 1TB each in RAID1. Then, 2 of them were removed, the raid was converted to RAID0, and the 3TB drive was added via btrfs device add, so I think it should have been automatically resized. Then the 1TB drive were removed, so that only 2 disks remained (1TB&3TB).

The df command shows 100% usage (but I know it cant be trusted on BTRFS raids):

[root@flsrv /share]# df

Filesystem Type Size Used Avail Use% Mounted on

/dev/mmcblk0p2 ext4 14G 5.7G 7.5G 44% /

/dev/sdc btrfs 3.7T 1.9T 256K 100% /share

The btrfs filesystem show /share shows:

Total devices 2 FS bytes used 1.81TiB

devid 4 size 931.51GiB used 931.51GiB path /dev/sdc

devid 5 size 2.73TiB used 931.51GiB path /dev/sdb

And the filesystem usage shows:

[root@flsrv /share]# btrfs filesystem usage /share

Overall:

Device size: 3.64TiB

Device allocated: 1.82TiB

Device unallocated: 1.82TiB

Device missing: 0.00B

Used: 1.82TiB

Free (estimated): 1.82TiB (min: 931.50GiB)

Data ratio: 1.00

Metadata ratio: 2.00

Global reserve: 512.00MiB (used: 0.00B)

Data,RAID0: Size:1.81TiB, Used:1.81TiB

/dev/sdb 927.48GiB

/dev/sdc 927.48GiB

Metadata,RAID1: Size:4.00GiB, Used:2.67GiB

/dev/sdb 4.00GiB

/dev/sdc 4.00GiB

System,RAID1: Size:32.00MiB, Used:160.00KiB

/dev/sdb 32.00MiB

/dev/sdc 32.00MiB

Unallocated:

/dev/sdb 1.82TiB

/dev/sdc 1.02MiB

The fdisk wont show any partitions:

[root@flsrv /share]# fdisk -l /dev/sdb

Disk /dev/sdb: 2.7 TiB, 3000592982016 bytes, 5860533168 sectors

Disk model: Hitachi HUA72303

Units: sectors of 1 * 512 = 512 bytes

Sector size (logical/physical): 512 bytes / 512 bytes

I/O size (minimum/optimal): 512 bytes / 512 bytes

[root@flsrv /share]# fdisk -l /dev/sdc

Disk /dev/sdc: 931.5 GiB, 1000204886016 bytes, 1953525168 sectors

Disk model: GB1000EAMYC

Units: sectors of 1 * 512 = 512 bytes

Sector size (logical/physical): 512 bytes / 512 bytes

I/O size (minimum/optimal): 512 bytes / 512 bytes

I’ve tried:

[root@flsrv /share]# btrfs filesystem resize 5:max /share

Resize '/share' of '5:max'

with no success.

I think I’m out of options I could google.

I run BTRFS on my root filesystem (on Linux), mostly for the quick snapshot and restore functionality. Yesterday I ran into a common problem: my drive was suddenly full. I went from 4GB of free space on my system drive to 0 in an instant, causing all sorts of chaos on my system.

This problem happens to lots of people because BTRFS doesn’t have a linear relationship to “free space available”. There are a few concepts that get in the way:

- Compression: BTRFS supports compressing data as it writes. This obviously changes the amount of data that can be stored. — 50MB of text may take only 5MB “room” on the drive.

- Metadata: BTRFS stores your data separately from metadata. Both data and metadata occupy “space”.

- Chunk allocation: BTRFS allocates space for your data in chunks.

- Multiple devices: BTRFS supports multiple devices working together, RAID-style. That means there’s extra information to store for every file. For example, RAID-1 stores two copies of every file, so a 50MB file takes 100MB of space.

- Snapshots: BTRFS can store snapshots of your device, which really store more like a diff from the current state. How much data is in the diff depends on your current state… so the snapshot itself doesn’t have a consistent size.

- Nested volumes: BTRFS lets you divide the filesystem into “subvolumes” — each of which can (someday) have its own RAID configuration.

It’s easy to look at the drive and tell how many MiB of space has not been used yet. But it’s very hard to accurately say how much of your data you can write in that space. For this reason the amount of “free space” reported on BRFS volumes by system utilities like df can jump a lot — like my disappearing 4GiB. Worse, the free space reported by general tools is misleading. BTRFS can run out of space while df still thinks you have lots available.

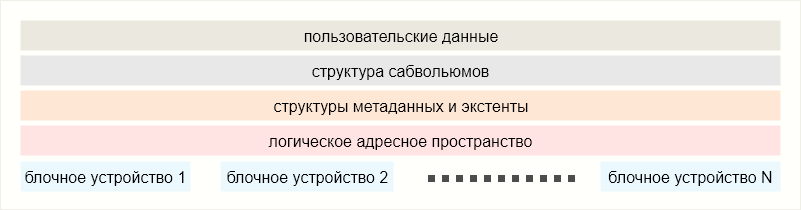

Let’s walk through how BTRFS stores data, to understand the problem a bit better. Then we can solve it with some of BTRFS’ own tools.

How much free space do I have?

Rather than using general tools like df to answer this question, it’s better to get more detail using the btrfs CLI tool.

BTRFS starts out with a big pool of raw storage, and allocates as it goes. You can get a listing of all the devices in a block device like this:

$ sudo btrfs fi show

Label: 'OS' uuid: c0d21ade-5570-41a3-b0cf-a5ce219e7a8e

Total devices 1 FS bytes used 31.74GiB

devid 1 size 48.83GiB used 47.80GiB path /dev/nvme0n1p2

In this case, I only have one physical device involved. You can see that it gives me a total number of bytes allocated, compared to the total size. In another filesystem this might be the number reported to df. Not so with BTRFS! Let’s dig deeper.

$ btrfs fi df /

Data, single: total=45.75GiB, used=30.56GiB

System, single: total=32.00MiB, used=16.00KiB

Metadata, single: total=2.02GiB, used=1.17GiB

GlobalReserve, single: total=89.31MiB, used=0.00B

The “total” values here are the breakdown of what the first command counts as “used”. btrfs fi df shows us of the allocated space, how much is actually storing data, and how much is just empty allocation. In this case: on my 48GiB device, 47GiB is allocated. Of the allocation, 31GiB is actually storing data. Side note: if you’re in a multi-drive situation this command will take into account RAID metadata.

Here’s an easier view:

$ sudo btrfs fi usage /

Overall:

Device size: 48.83GiB

Device allocated: 47.80GiB

Device unallocated: 1.03GiB

Device missing: 0.00B

Used: 31.74GiB

Free (estimated): 16.22GiB (min: 16.22GiB)

Data ratio: 1.00

Metadata ratio: 1.00

Global reserve: 89.31MiB (used: 0.00B)

Data,single: Size:45.75GiB, Used:30.56GiB

/dev/nvme0n1p2 45.75GiB

Metadata,single: Size:2.02GiB, Used:1.18GiB

/dev/nvme0n1p2 2.02GiB

System,single: Size:32.00MiB, Used:16.00KiB

/dev/nvme0n1p2 32.00MiB

Unallocated:

/dev/nvme0n1p2 1.03GiB

This shows the breakdown of space allocated and used across all the devices in this block device. “Overall” is for the whole block device, and that “Free (estimated)” number is what gets reported to df.

This is a problem: most of my normal tools tell me I have 15GB free space. But if I write 1GiB more data, BTRFS will run out of space anyways. This issue is a pain in the ass and hard to diagnose. It’s even harder to fix, since most of the solutions require having some extra space on the device.

Converting unused allocation to free space

So, why does BTRFS allocate so much space to store such a small amount of data? Here I am storing 31GiB of data in 47GiB of allocation, the used/total ratio is 0.66! This is very inefficient. It’s an unfortunate consequence of being a copy-on-write filesystem — BTRFS starts every write in a freshly allocated chunk. But the chunksize is static, and files come in all sizes. So lots of the time, a chunk is incompletely filled. That’s the “allocated but not used” space we’re complaining about.

Fortunately there’s a way to address this problem: BTRFS has a tool to “rebalance” your filesystem. It was originally designed for balancing the data stored across multiple drives (hence the name). It is also useful in single drive configurations though, to rebalance how data is stored within the allocation.

By default, balance will rewrite all the data on the disk. This is probably unnecessary. Chunks will be unevenly filled, but we saw above that the average should be about 66% used. So we’ll filter based on data (-d) usage, and only rebalance chunks that are less than 66% used. That will leave any partially filled chunks which are more-filled than average.

# Run it in the background, cause it takes a long time.

$ sudo btrfs balance start -dusage=66 / &

# Check status

$ sudo btrfs balance status -v /

Balance on '/' is running

1 out of about 27 chunks balanced (5 considered), 96% left

Dumping filters: flags 0x1, state 0x1,

# Or be lazy, and have bash report status every 60 seconds.

$ while :; do sudo btrfs balance status -v / ; sleep 60; done

Balance on '/' is running

3 out of about 27 chunks balanced (12 considered), 89% left

Dumping filters: flags 0x1, state 0x1, force is off

DATA (flags 0x2): balancing, usage=66

Balance on '/' is running

4 out of about 27 chunks balanced (13 considered), 85% left

Dumping filters: flags 0x1, state 0x1, force is off

DATA (flags 0x2): balancing, usage=66

...

# When the balance operation finishes:

Done, had to relocate 19 out of 59 chunks

There’s a nice big differnce once it’s finished:

$ btrfs filesystem df /

Data, single: total=32.53GiB, used=30.83GiB

System, single: total=32.00MiB, used=16.00KiB

Metadata, single: total=2.02GiB, used=1.17GiB

GlobalReserve, single: total=84.67MiB, used=0.00B

That’s 15GiB of space allocated for other use. My usage ratio is now 0.94. Huzzah! In some rare cases you may need to do this on the Metadata allocation (use -musage instead of -dusage above).

If you’ve already run out of space

If you have already run out of space, you can’t run a balance! In that caseyou have to get sneaky. Here are your options:

1) Free up space

This is harder than it sounds. If you just delete data, it will probably leave those chunks partially filled and therefore allocated. What you really need is unallocated space. The easiest place to get this is by deleting snapshots. Start from the oldest one, since it will be the biggest.

Once you have a little bit of wiggle room, rebalance a small segment, like Metadata. Then proceed with rebalancing data as described above.

2) Add some space

Don’t forget, a BTRFS volume can span multiple devices! I had to exercise this option recently. Add a device — a flash drive will do, but choose the fastest thing you can — and add it to the BTRFS volume.

# Add your extra drive (/dev/sda).

$ sudo btrfs device add -f /dev/sda /

# Now run the smallest balance operation you can.

$ sudo btrfs balance start -dusage=1 /

Done, had to relocate 1 out of 59 chunks

# Remove the device, and run a proper balance.

$ sudo btrfs device remove /dev/sda /

$ sudo btrfs balance start -dusage=66 /

Done, had to relocate 18 out of 59 chunks

Balance operations usually take a long time — more than an hour is not unusual. It will take even longer with slow flash media involved. For that reason, I use a very low balance filter (-dusage=) in this example. We only need to free up a teensy bit of space to run balance again without the flash disk in the mix.

And this last option is how I saved my computer last night. I hope this helps someone out of a similar predicament someday.

Update to the update: Do not do this! A friendly commentor from the BTRFS community let me know that this is actually a really bad idea, since anything that interrupts your RAM will wreck your filesystem irreparably. Stick with the USB drive solution, above. Thank you @Zygo for the correction, and sorry for anyone who suffered for my learning.

UPDATE: Now that I’ve had to do this a few times, it’s way better to rebalance a full filesystem by adding a ramdisk to it. Not only is it faster than a flash device, it’s also more reliable in most cases… and certainly for my kind of use case (a developer laptop) the important preconditions apply: lots of RAM, reliable power source. Here’s the recipe:

# Create a ramdisk. Make sure /dev/ram0 isn't in use already before doing this!

$ sudo mknod -m 660 /dev/ram0 b 1 0

$ sudo chown root:disk /dev/ram0

# Mount the ramdisk with a concrete size. Otherwise it grows to whatever is needed.

$ sudo mkdir /mnt/ramdisk

$ sudo mount -t ramfs -o size=4G,maxsize=4G /dev/ram0 /mnt/ramdisk

# Create a file on the ramdisk to use as a loopback device.

$ sudo dd if=/dev/zero of /mnt/ramdisk/extend.img bs=4M count=1000

$ sudo losetup -fP /mnt/ramdisk/extend.img

# figure out which loopback device ID is yours

$ sudo losetup -a |grep extend.img

/dev/loop10: [5243078]:8563965 (/mnt/ramdisk/extend.img)

# Add the loopback device to the btrfs filesystem

$ sudo btrfs device add /dev/loop10 /

# Decide on your balance ratio and balance as usual.

$ sudo btrfs fi usage / |head -n 6

Overall:

Device size: 400.91GiB

Device allocated: 396.36GiB

Device unallocated: 4.55GiB

Device missing: 0.00B

Used: 348.91GiB

$ echo 'scale=2;348/396' |bc

.87

$ sudo btrfs balance start -dusage=87 /

Done, had to relocate 46 out of 400 chunks

# Remove the device and destroy it.

$ sudo btrfs device delete /dev/loop0 /

$ sudo losetup -d /dev/loop10

$ sudo umount /mnt/ramdisk

$ sudo rm -rf /dev/ram0

Contents

- 1 Important Questions

- 1.1 I have a problem with my Btrfs filesystem!

- 1.2 I see a warning in dmesg about barriers being disabled when mounting my filesystem. What does that mean?

- 1.3 Help! I ran out of disk space!

- 1.4 Help! Btrfs claims I’m out of space, but it looks like I should have lots left!

- 1.4.1 if your device is small

- 1.4.2 if your device is large (>16GiB)

- 1.5 Are Btrfs changes backported to stable kernel releases?

- 2 Performance vs Correctness

- 2.1 Does Btrfs have data=ordered mode like Ext3?

- 2.2 What are the crash guarantees of overwrite-by-rename?

- 2.3 Why I experience poor performance during file access on filesystem?

- 2.4 What are the crash guarantees of rename?

- 2.5 Can the data=ordered mode be turned off in Btrfs?

- 2.6 What checksum function does Btrfs use?

- 2.7 Can data checksumming be turned off?

- 2.8 Can copy-on-write be turned off for data blocks?

- 2.9 Can I have nodatacow (or chattr +C) but still have checksumming?

- 3 Features

- 3.1 When will Btrfs have a fsck like tool?

- 3.1.1 What’s the difference between btrfsck and fsck.btrfs

- 3.2 Can I use RAID[56] on my Btrfs filesystem?

- 3.3 Is Btrfs optimized for SSD?

- 3.4 Does Btrfs support TRIM/discard?

- 3.5 Does Btrfs support encryption?

- 3.6 Does Btrfs work on top of dm-crypt?

- 3.7 Does Btrfs support deduplication?

- 3.8 Does Btrfs support swap files?

- 3.9 Does grub support Btrfs?

- 3.10 Is it possible to boot to Btrfs without an initramfs?

- 3.11 Compression support in Btrfs

- 3.11.1 Will Btrfs support LZ4?

- 3.1 When will Btrfs have a fsck like tool?

- 4 Common questions

- 4.1 How do I do…?

- 4.2 Is Btrfs stable?

- 4.3 What version of btrfs-progs should I use for my kernel?

- 4.4 Do I have to keep my btrfs-progs at the same version as my kernel?

- 4.5 I have converted my ext4 partition into Btrfs, how do I delete the ext2_saved folder?

- 4.6 How much free space do I have?

- 4.7 or My filesystem is full, and I’ve put almost nothing into it!

- 4.7.1 Understanding free space, using the original tools

- 4.7.2 Understanding free space, using the new tools

- 4.7.3 Understanding free space, using third-party tools

- 4.8 Why is free space so complicated?

- 4.9 Why is there so much space overhead?

- 4.10 How much space will I get with my multi-device configuration?

- 4.11 How much space do I get with unequal devices in RAID-1 mode?

- 4.12 What does «balance» do?

- 4.13 Does a balance operation make the internal B-trees better/faster?

- 4.14 Does a balance operation recompress files?

- 4.15 Do I need to run a balance regularly?

- 4.16 How do I undelete a file?

- 4.17 What is the difference between mount -o ssd and mount -o ssd_spread?

- 4.18 How long will the Btrfs disk format keep changing?

- 4.19 Can I find out compression ratio of a file?

- 4.20 Can I change metadata block size without recreating the filesytem?

- 4.21 Why do I have «single» chunks in my RAID filesystem?

- 4.22 What is the GlobalReserve and why does ‘btrfs fi df’ show it as single even on RAID filesystems?

- 4.23 What is the difference between -c and -p in send?

- 4.24 How do I recover from a «parent transid verify failed» error?

- 4.25 What does «parent transid verify failed» mean?

- 4.25.1 How does this happen?

- 5 Subvolumes

- 5.1 What is a subvolume?

- 5.2 How do I find out which subvolume is mounted?

- 5.3 What is a snapshot?

- 5.3.1 snapshot example

- 5.4 Can I mount subvolumes with different mount options?

- 6 Interaction with partitions, device managers and logical volumes

- 6.1 Btrfs has subvolumes, does this mean I don’t need a logical volume manager and I can create a big Btrfs filesystem on a raw partition?

- 6.2 Does the Btrfs multi-device support make it a «rampant layering violation»?

- 6.3 What are the differences among MD-RAID / device mapper / Btrfs raid?

- 6.3.1 MD-RAID

- 6.3.2 device mapper

- 6.3.3 Btrfs

- 6.4 Case study: btrfs-raid 5/6 versus MD-RAID 5/6

- 7 About the project

- 7.1 What is your affiliation with WinBtrfs

- 7.2 Will Btrfs become a clustered file system

- 8 I’ve heard that …

- 8.1 … files cannot be deleted once the filesystem is full

- 8.2 … Btrfs is broken by design (aka. Edward Shishkin’s «Unbound(?) internal fragmentation in Btrfs»)

Important Questions

I have a problem with my Btrfs filesystem!

See the Problem FAQ for commonly-encountered problems and solutions.

If that page doesn’t help you, try asking on IRC or the Btrfs mailing list.

Explicitly said: please report bugs and issues to the mailing list (you are not required to subscribe).

Then use Bugzilla which will ensure traceability.

I see a warning in dmesg about barriers being disabled when mounting my filesystem. What does that mean?

Your hard drive has been detected as not supporting barriers. This is a severe condition, which can result in full file-system corruption, not just losing or corrupting data that was being written at the time of the power cut or crash. There is only one certain way to work around this:

Note: Disable the write cache on each drive by running hdparm -W0 /dev/sda against each drive on every boot.

Failure to perform this can result in massive and possibly irrecoverable corruption (especially in the case of encrypted filesystems).

Help! I ran out of disk space!

Help! Btrfs claims I’m out of space, but it looks like I should have lots left!

Free space is a tricky concept in Btrfs. This is especially apparent when running low on it. Read «Why is there so many ways to check the amount of free space» below for the blow-by-blow.

You can look at the tips below, and you can also try Marc MERLIN’s debugging filesystem full page

if your device is small

The best solution for small devices (under about 16 GB) is to reformat the FS with the --mixed option to mkfs.btrfs. This needs a kernel 2.6.37 or later, and similarly recent btrfs-progs.

The main issue is that the allocation units (chunk size) are very large compared to the size of the filesystem, and the allocation can very quickly become full. A btrfs fi balance may get you working again, but it’s probably only a short term fix, as the metadata to data ratio probably won’t match the block allocations.

If you can afford to delete files, you can clobber a file via

echo > /path/to/file

which will recover that space without requiring a new metadata allocation (which would otherwise ENOSPC again).

You might consider remounting with -o compress, and either rewrite particular files in-place, or run a recursive defragmentation which (if an explicit flag is given, or if the filesystem is mounted with compression enabled) will also recompress everything. This may take a while.

if your device is large (>16GiB)

If the filesystem has allocated (but not used) all of the available space, and the metadata is close to full, then df can show lots of free space, but you may still get out of space errors because there isn’t enough metadata available.

To see if this is the case, first look for the amount of allocated space with

# sudo btrfs fi show /dev/device

If this shows the «used» value equal to the «total» value on each device, then everything has been allocated, which is the first condition for this problem.

Secondly, look at the amount of space you have in metadata, as reported by

$ btrfs fi df /mountpoint

If the «used» metadata is close to the «total» value, then that’s the second condition for this problem, and you should read on. What does «close» mean? If the free space in metadata is less than or equal to the block reserve value (typically 512 MiB, but might be something else on a particularly small or large filesystem), then it’s close to full.

If you have full up metadata, and more than 1 GiB of space free in data, as reported by btrfs fi df, then you should be able to free up some of the data allocation with a partial balance:

# btrfs balance start /mountpoint -dlimit=3

We know this isn’t ideal, and there are plans to improve the behavior. Running close to empty is rarely the ideal case, but we can get far closer to full than we do.

Free space cache file is invalid. skip it

If you see something like this when mounting:

BTRFS info (device sdc1): The free space cache file (2159324168192) is invalid. skip it

then you should run btrfs check on your fs. I have been seeing this in dmesg and Data would not allocate new blocks at all. Doing btrfs check fixed this at least for me. I still would hit the bug below afterwards (bug #74101) — that is, Data would normally resize, but sometimes it would fail to do that, and the fs crashed and remounted as ro. Before btrfs check I also resized the fs to smaller than it was and then to the max size using btrfs fi resize, which may have helped part way, but until I ran btrfs check, Data would not resize. Try resizing.

When you haven’t hit the «usual» problem

If the conditions above aren’t true (i.e. there’s plenty of unallocated space, or there’s lots of unused metadata allocation), then you may have hit a known but unresolved bug. If this is the case, please report it to either the mailing list, or IRC. In some cases, it has been possible to deal with the problem, but the approach is new, and we would like more direct contact with people experiencing this particular bug.

The «Data» field in btrfs fi df fills up and doesn’t become larger, and then the bug transpires. This has been reported in the btrfs mailing list (search for the subject 6TB partition, Data only 2TB — aka When you haven’t hit the «usual» problem). Here is a likely bug report: https://bugzilla.kernel.org/show_bug.cgi?id=74101

The bug would only happen after some time, so I was able to move a lot of data onto the fs before btrfs crashed, and then it was just a case of unmounting and mounting again.

Are Btrfs changes backported to stable kernel releases?

Yes, the obviously critical fixes get to the latest stable kernel and sometimes get also applied to the long-term branches. Please note that there’s yet no one appointed and submitting the patches is done on voluntary basis or when the maintainer(s) do that.

Beware that apart from critical fixes, the longterm branches do not receive backports of less important fixes done by the upstream maintainers. You should ask your distro kernel maintainers to do that. A CC of the linux-btrfs mailinglist is a good idea when there are patches selected for a particular longterm kernel and requested for addition to stable trees.

Performance vs Correctness

Does Btrfs have data=ordered mode like Ext3?

In v0.16, Btrfs waits until data extents are on disk before updating metadata. This ensures that stale data isn’t exposed after a crash, and that file data is consistent with the checksums stored in the btree after a crash.

Note that you may get zero-length files after a crash, see the next questions for more info.

Btrfs does not force all dirty data to disk on every fsync or O_SYNC operation, fsync is designed to be fast.

What are the crash guarantees of overwrite-by-rename?

As of August 2014 (v3.17), btrfs requires an explicit fsync after writing the new content and before moving it to overwrite the old data. This behaviour is the same as most other Linux filesystems.

Overwriting an existing file using a rename is atomic, but the new data must be reliably on the disk before the old data is overwritten. Thus, the correct sequence to replace a file named data_file should be:

- Open a new file,

data_file.tmp - Write data to the new file

- Call fsync on it

- Close it

- Rename

data_file.tmpasdata_file

If a crash occurs at any point during this sequence, it will result in either

-

data_filecontains the new content;data_file.tmpdoes not exist, or -

data_filecontains the old content;data_file.tmpmay contain the new content, be zero-length, or not exist at all.

The fsync can be safely omitted only if the FS is mounted with -o flushoncommit.

Why I experience poor performance during file access on filesystem?

By default the file system is mounted with relatime flag, which means it must update files’ metadata during first access on each day. Since updates to metadata are done as COW, if one visits a lot o files, it results in massive and scattered write operations on the underlying media.

You need to mount file system with noatime flag to prevent this from happening.

More details are in Manpage/btrfs(5)#NOTES_ON_GENERIC_MOUNT_OPTIONS

What are the crash guarantees of rename?

Renames NOT overwriting existing files do not give additional guarantees. This means, a sequence like

echo "content" > file.tmp mv file.tmp file # *crash*

will most likely give you a zero-length «file». The sequence can give you either

- Neither file nor file.tmp exists

- Either file.tmp or file exists and is 0-size or contains «content»

For more info see this thread: http://thread.gmane.org/gmane.comp.file-systems.btrfs/5599/focus=5623

Can the data=ordered mode be turned off in Btrfs?

No, it is an important part of keeping data and checksums consistent. The Btrfs data=ordered mode is very fast and turning it off is not required for good performance.

What checksum function does Btrfs use?

Please see this section in manual page.

Can data checksumming be turned off?

Yes, you can disable it by mounting with -o nodatasum. Please note that checksumming is also turned off when the filesystem is mounted with nodatacow.

Can copy-on-write be turned off for data blocks?

Yes, there are several ways how to do that.

Disable it by mounting with nodatacow. This implies nodatasum as well. COW may still happen if a snapshot is taken. However COW will still be maintained for existing files, because the COW status can be modified only for empty or newly created files.

For an empty file, add the NOCOW file attribute (use chattr utility with +C), or you create a new file in a directory with the NOCOW attribute set (then the new file will inherit this attribute).

Now copy the original data into the pre-created file, delete original and rename back.

There is a script you can use to do this [1].

Shell commands may look like this:

touch vm-image.raw chattr +C vm-image.raw fallocate -l10g vm-image.raw

will produce file suitable for a raw VM image — the blocks will be updated in-place and are preallocated.

Can I have nodatacow (or chattr +C) but still have checksumming?

No.

With normal CoW operations, the atomicity is achieved by constructing a completely new metadata tree containing both changes (references to the data, and the csum metadata), and then atomically changing the superblock to point to the new tree.

With nodatacow, that approach doesn’t work, because the new data replaces the old on the physical medium, so you’d have to make the data write atomic with the superblock write — which can’t be done, because it’s (at least) two distinct writes. This means that you have to write the two separately, which then means that there’s a period between the two writes where things can go wrong.

When you write data and metadata separately (which you have to do in the nodatacow case), and the system halts between the two writes, then you either have the new data with the old csum, or the old csum with the new data. Both data and csum are «good», but good from different states of the FS. In both orderings (write data first or write metadata first), the csum doesn’t match the data, and so you now have an I/O error reported when trying to read that data.

You can’t easily fix this, because when the data and csum don’t match, you need to know the reason they don’t match — is it because the machine was interrupted during write (in which case you can simply compute a good csum from the data and carry on as normal), or is it because the hard disk has been corrupted in some way, completely independently of the crash, and the data is now toast (in which case you shouldn’t fix the I/O error)?

Basically, nodatacow bypasses the very mechanisms that are meant to provide consistency in the filesystem.

Features

(See also the Project ideas page)

When will Btrfs have a fsck like tool?

It does!

The first detailed report on what comprises «btrfsck»

Btrfsck has its own page, go check it out.

Note that in many cases, you don’t want to run fsck. Btrfs is fairly self healing, but when needed check and recovery can be done several ways. Marc MERLIN has written a page that explains the different ways to check and fix a btrfs filesystem.

The btrfsck tool in the git master branch for btrfs-progs is now capable of repairing some types of filesystem breakage. It is not well-tested in real-life situations yet. If you have a broken filesystem, it is probably better to use btrfsck with advice from one of the btrfs developers, just in case something goes wrong. (But even if it does go badly wrong, you’ve still got your backups, right?)

Note that there is also a recovery tool in the btrfs-progs git repository which can often be used to copy essential files out of broken filesystems.

What’s the difference between btrfsck and fsck.btrfs

- btrfsck is the actual utility that is able to check and repair a filesystem

- fsck.btrfs is a utility that should exist for any filesystem type and is called during system setup when the corresponding /etc/fstab entries contain non-zero value for fs_passno. (See fstab(5) for more.)

Traditional filesystems need to run their respective fsck utility in case the filesystem was not unmounted cleanly and the log needs to be replayed before mount. This is not needed for btrfs. You should set fs_passno to 0.

Note, if the fsck.btrfs utility is in fact btrfsck, then the filesystem is unnecessarily checked upon every boot and slows down the whole operation. It is safe to and recommended to turn fsck.btrfs into a no-op, eg. by cp /bin/true /sbin/fsck.btrfs.

Can I use RAID[56] on my Btrfs filesystem?

The parity RAID feature is mostly implemented, but has some problems in the case of power failure (or other unclean shutdown) which lead to damaged data. It is recommended that parity RAID be used only for testing purposes.

See RAID56 for more details.

Is Btrfs optimized for SSD?

There are some optimizations for SSD drives, and you can enable them by mounting with -o ssd. As of 2.6.31-rc1, this mount option will be enabled if Btrfs is able to detect non-rotating storage.

Note that before 4.14 the ssd mount option has a negative impact on usability and lifetime of modern SSDs which have a FTL (Flash Translation Layer). See the ssd section in Gotchas for more information.

Note that -o ssd will not enable TRIM/discard.

Does Btrfs support TRIM/discard?

There are two ways how to apply the discard:

- during normal operation on any space that’s going to be freed, enabled by mount option discard

- on demand via the command fstrim

«-o discard» can have some negative consequences on performance on some SSDs or at least whether it adds worthwhile performance is up for debate depending on who you ask, and makes undeletion/recovery near impossible while being a security problem if you use dm-crypt underneath (see http://asalor.blogspot.com/2011/08/trim-dm-crypt-problems.html ), therefore it is not enabled by default. You are welcome to run your own benchmarks and post them here, with the caveat that they’ll be very SSD firmware specific.

The fstrim way is more flexible as it allows to apply trim on a specific block range, or can be scheduled to time when the filesystem perfomace drop is not critical.

Does Btrfs support encryption?

There are several different ways in which a filesystem can interoperate with encryption to keep your data secure:

- It can operate on top of an encrypted partition (dm-crypt / LUKS) scheme.

- It can be used as a component of a stacked approach (eg. ecryptfs) where a layer above the filesystem transparently provides the encryption.

- It can natively attempt to encrypt file data and associated information such as the file name.

There are advantages and disadvantages to each method, and care should be taken to make sure that the encryption protects against the right threat. In some situations, more than one approach may be needed.

Typically, partition (or entire disk) encryption is used to protect data in case a computer is stolen, a hard disk has to be returned to the manufacturer if it fails under warranty or due to the difficulty of erasing modern drives. Modern hard disks and SSDs transparently remap logical sectors to physical sectors for various reasons, including bad sectors and wear leveling. This means sensitive data can remain on a sector even after an attempt to erase the whole disk. The only protection against these challenges is full disk encryption from the moment you buy the disk. Full disk encryption requires a password for the computer to boot, but the system operates normally after that. All data (except the boot loader and kernel) is encrypted. Btrfs works safely with partition encryption (luks/dm-crypt) since Linux 3.2. Earlier kernels will start up in this mode, but are known to be unsafe and may corrupt due to problems with dm-crypt write barrier support.

Partition encryption does not protect data accessed by a running system — after boot, a user sees the computer normally, without having to enter extra passwords. There may also be some performance impact since all IO must be encrypted, not just important files. For this reason, it’s often preferable to encrypt individual files or folders, so that important files can’t be accessed without the right password while the system is online. If the computer might also be stolen, it may be preferable to use partition encryption as well as file encryption.

Btrfs does not support native file encryption (yet), and there’s nobody actively working on it. It could conceivably be added in the future.

As an alternative, it is possible to use a stacked filesystem (eg. ecryptfs) with btrfs. In this mode, the stacked encryption layer is mounted over a portion of a btrfs volume and transparently applies the security before the data is sent to btrfs. Another similar option is to use the fuse-based filesystem encfs as a encrypting layer on top of btrfs.

Note that a stacked encryption layer (especially using fuse) may be slow, and because the encryption happens before btrfs sees the data, btrfs compression won’t save space (encrypted data is too scrambled). From the point of view of btrfs, the user is just writing files full of noise.

Also keep in mind that if you use partition level encryption and btrfs RAID on top of multiple encrypted partitions, the partition encryption will have to individually encrypt each copy. This may result in somewhat reduced performance compared to a traditional RAID setup where the encryption might be done on top of RAID. Whether the encryption has a significant impact depends on the workload, and note that many newer CPUs have hardware encryption support.

Does Btrfs work on top of dm-crypt?

This is deemed safe since 3.2 kernels. Corruption has been reported before that, so you want a recent kernel. The reason was improper passing of device barriers that are a requirement of the filesystem to guarantee consistency.

If you are trying to mount a btrfs filesystem based on multiple dm-crypted devices, you can see an example script on Marc’s btrfs blog: start-btrfs-dmcrypt.

Does Btrfs support deduplication?

Deduplication is supported, with some limitations. See Deduplication.

Does Btrfs support swap files?

Yes, please see this section in manual page.

Does grub support Btrfs?

In most cases. Grub supports many btrfs configurations, including zlib and lzo compression (but not zstd, depending on the Grub version) and RAID0/1/10 multi-dev filesystems.

If your distribution only provides older versions of Grub, you’ll have to build it for yourself.

grubenv write support (used to track failed boot entries) is lacking, Grub needs btrfs to support a reserved area.

References:

- BtrFS zlib compression support (2010-12-03)

- Add support for LZO compression in GRUB (2011-10-06)

- btrfs: Add zstd support to grub btrfs (2018-11-19)

Is it possible to boot to Btrfs without an initramfs?

With multiple devices, btrfs normally needs an initramfs to perform a device scan. It may be necessary to modprobe (and then rmmod) scsi-wait-scan to work around a race condition. See using Btrfs with multiple devices.

With grub and a single disk, you might not need an initramfs. Grub generates a root=UUID=… command line that the kernel should handle on its own. Some people have also used GPT and root=PARTUUID= specs instead [2].

Compression support in Btrfs

There’s a separate page for compression related questions, Compression.

Will Btrfs support LZ4?

Maybe, if there is a clear benefit compared to existing compression support. Technically there are no obstacles, but supporing a new algorithm has impact on the the userpace tools or bootloader, that has to be justified. There’s a project idea Compression enhancements that targets more than just adding a new compression algorithm.

Reasons against adding simple LZ4 support are stated here and here. Similar holds for snappy compression algorithm, but it performs worse than LZ4 and is not considered anymore.

Common questions

How do I do…?

See also the UseCases page.

Is Btrfs stable?

Short answer: Maybe.

Long answer: Nobody is going to magically stick a label on the btrfs code and say «yes, this is now stable and bug-free». Different people have different concepts of stability: a home user who wants to keep their ripped CDs on it will have a different requirement for stability than a large financial institution running their trading system on it. If you are concerned about stability in commercial production use, you should test btrfs on a testbed system under production workloads to see if it will do what you want of it. In any case, you should join the mailing list (and hang out in IRC) and read through problem reports and follow them to their conclusion to give yourself a good idea of the types of issues that come up, and the degree to which they can be dealt with. Whatever you do, we recommend keeping good, tested, off-system (and off-site) backups.

Pragmatic answer: Many of the developers and testers run btrfs as their primary filesystem for day-to-day usage, or with various forms of real data. With reliable hardware and up-to-date kernels, we see very few unrecoverable problems showing up. As always, keep backups, test them, and be prepared to use them.

When deciding if Btrfs is the right file system for your use case, don’t forget to look at the Status page, which contains an overview of the general status of distinct features of the file system.

What version of btrfs-progs should I use for my kernel?

Simply use the latest version.

The userspace tools versions roughly match the kernel releases and should contain support for features introduced in the respective kernel release. The minor versions are bugfix releases or independent updates (eg. documentation, tests).

Do I have to keep my btrfs-progs at the same version as my kernel?

No.

If your btrfs-progs is newer than your kernel, then you may not be able to use some of the features that the btrfs-progs offers, because the kernel doesn’t support them.

If your btrfs-progs is older than your kernel, then you may not be able to use some of the features that the kernel offers, because the btrfs-progs doesn’t support them.

Other than that, there should be no restrictions on which versions work together.

I have converted my ext4 partition into Btrfs, how do I delete the ext2_saved folder?

The folder is a normal btrfs subvolume and you can delete it with the command

btrfs subvolume delete /path/to/btrfs/ext2_saved

How much free space do I have?

or My filesystem is full, and I’ve put almost nothing into it!

Free space in Btrfs is a tricky concept from a traditional viewpoint, owing partly to the features it provides and partly to the difficulty in making too many assumptions about the exact information you need to know at the time.

Understanding free space, using the original tools

Btrfs starts with a pool of raw storage, made up of the space on all the devices in the FS. This is what you see when you run btrfs fi show:

$ sudo btrfs fi show Label: none uuid: 12345678-1234-5678-1234-1234567890ab Total devices 2 FS bytes used 304.48GB devid 1 size 427.24GB used 197.01GB path /dev/sda1 devid 2 size 465.76GB used 197.01GB path /dev/sdc1

The pool is the total size of /dev/sda1 and /dev/sdc1 in this case. The filesystem automatically allocates space out of the pool as it needs it. In this case, it has allocated 394.02 GiB of space (197.01+197.01), out of a total of 893.00 GiB (427.24+465.76) across two devices. The allocation is simply setting aside a region of a disk for some purpose (e.g. «data will be stored in this region»). The output from btrfs fi show, however, doesn’t tell the whole story. The btrfs fi show output only shows how much has been allocated out of the total available space. In order to see how that allocation is used, and how much of it contains useful data, you also need btrfs fi df:

$ btrfs fi df / Metadata, single: total=18.00GB, used=6.10GB Data, single: total=376.00GB, used=298.37GB System, single: total=12.00MB, used=40.00KB

Note that the «total» values here add up to the «used» values in btrfs fi show. The «used» values here tell you how much useful information is stored. The rest is free space available for data (or metadata).

So, in this case, there is 77.63 GiB of space (376-298.37) for data allocated but unused, and a further 498.98 GiB (427.24+465.76-197.01-197.01) unallocated and available for further use. Some of the unallocated space may be used for metadata as the FS grows in size.

The interpretation is slightly more complicated with RAID filesystems. With a RAID filesystem, btrfs fi show still shows the raw disk space being allocated, but btrfs fi df shows the space available for files, so it takes account of the extra space needed by RAID. Here’s a slightly more complex example:

$ sudo btrfs fi show Label: none uuid: b7c23711-6b9e-46a8-b451-4b3f79c7bc46 Total devices 2 FS bytes used 14.67GiB devid 1 size 40.00GiB used 16.01GiB path /dev/sdc1 devid 2 size 40.00GiB used 16.01GiB path /dev/sdd1

$ sudo btrfs fi df /mnt Data, RAID1: total=15.00GiB, used=14.65GiB System, RAID1: total=8.00MiB, used=16.00KiB Metadata, RAID1: total=1.00GiB, used=15.59MiB GlobalReserve, single: total=16.00MiB, used=0.00

Here, we can see that 32.02 GiB of space has been allocated out of the 80 GiB available. The btrfs fi df output tells us that each of Data, Metadata and System have RAID-1 allocation. Now, note that the sum of the «total» values here is much smaller than the allocated space reported by btrfs fi show. This is because RAID-1 stores two copies of every byte written to it, so to store the 14.65 GiB of data in this filesystem, the 15 GiB of data allocation actually takes up 30 GiB of space on the disks. Taking account of this, we find that the total allocation is: (15.00 + 0.008 + 1.00) * 2, which is 32.02 GiB. The GlobalReserve can be ignored in this calculation.

Depending on the RAID level you are using, the «correction» factor will be different:

* single and RAID-0 have no correction * DUP, RAID-1 and RAID-10 store two copies, and need to have the values frombtrfs fi dfdoubled * RAID-5 uses one device for parity, sobtrfs fi dfshould be multiplied by n/(n-1) for an n-device filesystem * RAID-6 uses two devices for parity, sobtrfs fi dfshould be multiplied by n/(n-2) for an n-device filesystem

(Note that the number of devices in use may vary on filesystems with unequal devices, so the values for RAID-5 and RAID-6 may not be correct in that case).

Understanding free space, using the new tools

An all-in-one tool for reporting on free space is available in btrfs-progs from 3.18 onwards. This is btrfs fi usage:

$ sudo btrfs fi usage /mnt Overall: Device size: 80.00GiB Device allocated: 32.02GiB Device unallocated: 47.98GiB Used: 29.33GiB Free (estimated): 24.34GiB (min: 24.34GiB) Data ratio: 2.00 Metadata ratio: 2.00 Global reserve: 16.00MiB (used: 0.00B) Data,RAID1: Size:15.00GiB, Used:14.65GiB /dev/sdc1 15.00GiB /dev/sdd1 15.00GiB Metadata,RAID1: Size:1.00GiB, Used:15.59MiB /dev/sdc1 1.00GiB /dev/sdd1 1.00GiB System,RAID1: Size:8.00MiB, Used:16.00KiB /dev/sdc1 8.00MiB /dev/sdd1 8.00MiB Unallocated: /dev/sdc1 23.99GiB /dev/sdd1 23.99GiB

This is showing the space usage for the same filesystem at the end of the previous section, with two 40 GiB devices. The «Overall» section shows aggregate information for the whole filesystem: There are 80 GiB of raw storage in total, with 32.02 GiB allocated, and 29.33 GiB of that allocation used. The «data ratio» and «metadata ratio» values are the proportion of raw disk space that is used for each byte of data written. For a RAID-1 or RAID-10 filesystem, this should be 2.0; for RAID-5 or RAID-6, this should be somewhere between 1.0 and 1.5. In the example here, the value of 2.0 for data indicates that the 29.34 GiB of used space is holding 14.67 GiB of actual data (29.34 / 2.0).

The «free» value is an estimate of the amount of data that can still be written to this FS, based on the current usage profile. The «min» value is the minimum amount of data that you can expect to be able to get onto the filesystem.

Below the «overall» section, information is shown for each of the types type of allocation, summarised and then broken down by device. In this section, you are seeing the values after the data or metadata ratio is accounted for, so we can see the 14.65 GiB of actual data used, and the 15 GiB of allocated space it lives in. (The small discrepancy with the value we worked out previously can be accounted for by rounding errors).

Understanding free space, using third-party tools

- btdu shows an overview of disk usage by taking random samples.

- btrfs-heatmap creates visualizations of how a btrfs filesystem is using the underlying disk space.

- btsdu measures changed data between two snapshots.

- compsize measures used compression types and effective compression ratio of specified directories.

Why is free space so complicated?

You might think, «My whole disk is RAID-1, so why can’t you just divide everything by 2 and give me a sensible value in df?».

If everything is RAID-1 (or RAID-0, or in general all the same RAID level), then yes, we could give a sane and consistent value from df. However, we have plans to allow per-subvolume and per-file RAID levels. In this case, it becomes impossible to give a sensible estimate as to how much space there is left.

For example, if you have one subvolume as «single», and one as RAID-1, then the first subvolume will consume raw storage at the rate of one byte for each byte of data written. The second subvolume will take two bytes of raw data for each byte of data written. So, if we have 30GiB of raw space available, we could store 30GiB of data on the first subvolume, or 15GiB of data on the second, and there is no way of knowing which it will be until the user writes that data.

So, in general, it is impossible to give an accurate estimate of the amount of free space on any btrfs filesystem. Yes, this sucks. If you have a really good idea for how to make it simple for users to understand how much space they’ve got left, please do let us know, but also please be aware that the finest minds in btrfs development have been thinking about this problem for at least a couple of years, and we haven’t found a simple solution yet.

Why is there so much space overhead?

There are several things meant by this. One is the out-of-space issues discussed above; this is a known deficiency, which can be worked around, and will eventually be worked around properly. The other meaning is the size of the metadata block group, compared to the data block group. Note that you shouldn’t compare the size of the allocations, but rather the used space in the allocations.

There are several considerations:

- The default raid level for the metadata group is dup on single drive systems, and raid1 on multi drive systems. The meaning is the same in both cases: there are two copies of everything in that group. This can be disabled at mkfs time, and it is possible to migrate raid levels online using the Balance_filters.

- There is an overhead to maintaining the checksums (approximately 0.1% – 4 bytes for each 4k block)

- Small files are also written inline into the metadata group. If you have several gigabytes of very small files, this will add up.

[incomplete; disabling features, etc]

How much space will I get with my multi-device configuration?

There is an online tool which can calculate the usable space from your drive configuration. For more details about RAID-1 mode, see the question below.

How much space do I get with unequal devices in RAID-1 mode?

For a specific configuration, you can use the online tool to see what will happen.

The general rule of thumb is if your largest device is bigger than all of the others put together, then you will get as much space as all the smaller devices added together. Otherwise, you get half of the space of all of your devices added together.

For example, if you have disks of size 3TB, 1TB, 1TB, your largest disk is 3TB and the sum of the rest is 2TB. In this case, your largest disk is bigger than the sum of the rest, and you will get 2TB of usable space.

If you have disks of size 3TB, 2TB, 2TB, then your largest disk is 3TB and the sum of the rest of 4TB. In this case, your largest disk is smaller than the sum of the rest, and you will get (3+2+2)/2 = 3.5TB of usable space.

If the smaller disks are not the same size, the above holds true for the first case (largest device is bigger than all the others combined), but might not be true if the sum of the rest is larger. In this case, you can apply the rule multiple times.

For example, if you have disks of size 2TB, 1.5TB, 1TB, then the largest disk is 2TB and the sum is 2.5TB, but the smaller devices aren’t equal, so we’ll apply the rule of thumb twice. First, consider the 2TB and the 1.5TB. This set will give us 1.5TB usable and 500GB left over. Now consider the 500GB left over with the 1TB. This set will give us 500GB usable and 500GB left over. Our total set (2TB, 1.5TB, 1TB) will thus yield 2TB usable.

Another example is 3TB, 2TB, 1TB, 1TB. In this, the largest is 3TB and the sum of the rest is 4TB. Applying the rule of thumb twice, we consider the 3TB and the 2TB and get 2TB usable with 1TB left over. We then consider the 1TB left over with the 1TB and the 1TB and get 1.5TB usable with nothing left over. Our total is 3.5TB of usable space.

What does «balance» do?

btrfs filesystem balance is an operation which simply takes all of the data and metadata on the filesystem, and re-writes it in a different place on the disks, passing it through the allocator algorithm on the way. It was originally designed for multi-device filesystems, to spread data more evenly across the devices (i.e. to «balance» their usage). This is particularly useful when adding new devices to a nearly-full filesystem.

Due to the way that balance works, it also has some useful side-effects:

- If there is a lot of allocated but unused data or metadata chunks, a balance may reclaim some of that allocated space. This is the main reason for running a balance on a single-device filesystem.

- On a filesystem with damaged replication (e.g. a RAID-1 FS with a dead and removed disk), it will force the FS to rebuild the missing copy of the data on one of the currently active devices, restoring the RAID-1 capability of the filesystem.

Until at least 3.14, balance is sometimes needed to fix filesystem full issues. See Balance_Filters.

Does a balance operation make the internal B-trees better/faster?

No, balance has nothing at all to do with the B-trees used for storing all of btrfs’s metadata. The B-tree implementation used in btrfs is effectively self-balancing, and won’t lead to imbalanced trees. See the question above for what balance does (and why it’s called «balance»).

Does a balance operation recompress files?

No. Balance moves entire file extents and does not change their contents. If you want to recompress files, use btrfs filesystem defrag with the -c option.

Balance does a defragmentation, but not on a file level rather on the block group level. It can move data from less used block groups to the remaining ones, eg. using the usage balance filter.

Do I need to run a balance regularly?

In general usage, no. A full unfiltered balance typically takes a long time, and will rewrite huge amounts of data unnecessarily. You may wish to run a balance on metadata only (see Balance_Filters) if you find you have very large amounts of metadata space allocated but unused, but this should be a last resort. At some point, this kind of clean-up will be made an automatic background process.

How do I undelete a file?

There is no reliable way of doing this, other than restoring from backups.

However, there are two possible approaches that may work (but probably won’t):

- Unmount the filesystem as soon as possible, and use btrfs-find-root and btrfs restore to find an earlier metadata root and restore the files.

- Unmount the filesystem as soon as possible, and use a file-carving tool (say, PhotoRec or some other carving tool) to find data that looks like the file you deleted.

There is no simple undelete tool for btrfs, and it is likely there never will be. The approaches listed above are unreliable at best. It is far better to ensure that you have good working backups in the first place.

What is the difference between mount -o ssd and mount -o ssd_spread?

Mount -o ssd_spread is more strict about finding a large unused region of the disk for new allocations, which tends to fragment the free space more over time. Mount -o ssd_spread is often faster on the less expensive SSD devices. The default for autodetected SSD devices is mount -o ssd.

How long will the Btrfs disk format keep changing?

The Btrfs disk format is not immutable. However, any changes that are made will not invalidate existing filesystems. If a new feature results in a change to the filesystem format, it will be implemented in a way which is both safe and compatible: filesystems made with the new feature will safely refuse to mount on older kernels which do not support the feature, and existing filesystems will not have the new feature enabled without explicit manual intervention to add the feature to the filesystem.

Can I find out compression ratio of a file?

compsize takes a list of files on a btrfs filesystem and measures used compression types and effective compression ratio: https://github.com/kilobyte/compsize

There’s a patchset http://thread.gmane.org/gmane.comp.file-systems.btrfs/37312 that extends the FIEMAP interface to return the physical length of an extent (ie. the compressed size).

The size obtained is not exact and is rounded up to block size (4KB). The real amount of compressed bytes is not reported and recorded by the filesystem (only the block count) in it’s structures. It is saved in the disk blocks but solely processed by the compression code.

Can I change metadata block size without recreating the filesytem?

No, the value passed to mkfs.btrfs -n SIZE cannot be changed once the filesystem is created. A backup/restore is needed.

Note, that this will likely never be implemented because it would require major updates to the core functionality.

Why do I have «single» chunks in my RAID filesystem?

After mkfs with an old version of mkfs.btrfs, and writing some data to the filesystem, btrfs filesystem df /mountpoint will show something like this:

Data, RAID1: total=3.08TiB, used=3.02TiB Data, single: total=8.00MiB, used=0.00B System, RAID1: total=3.88MiB, used=336.00KiB System, single: total=4.00MiB, used=0.00B Metadata, RAID1: total=4.19GiB, used=3.56GiB Metadata, single: total=8.00MiB, used=0.00B GlobalReserve, single: total=512.00MiB, used=0.00B

The single chunks are perfectly normal, and are a result of the way that mkfs works. They are small, harmless, and will remain unused as the FS grows, so you won’t risk any unreplicated data. You can get rid of them with a balance:

$ btrfs balance start -dusage=0 -musage=0 /mountpoint

(but don’t do this immediately after running mkfs, as you may end up losing your RAID configuration and reverting to single mode — put at least some data on the FS first).

This issue has been fixed in mkfs.btrfs since v4.2.

What is the GlobalReserve and why does ‘btrfs fi df’ show it as single even on RAID filesystems?

The global block reserve is last-resort space for filesystem operations that

may require allocating workspace even on a full filesystem. An example is

removing a file, subvolume or truncating a file. This is mandated by the COW

model, even removing data blocks requires to allocate some metadata blocks

first (and free them once the change is persistent).

The block reserve is only virtual and is not stored on the devices. It’s an

internal notion of Metadata but normally unreachable for the user actions

(besides the ones mentioned above). For ease it’s displayed as single.

The size of global reserve is determined dynamically according to the

filesystem size but is capped at 512MiB. The value used greater than 0

means that it is in use.

What is the difference between -c and -p in send?

It’s easiest to understand if you look at what receive does. Receive takes a stream of instructions, creates a new subvolume, and uses the instructions to modify that subvolume until it looks like the one being sent.

When you use -p, the receiver will take a snapshot of the corresponding subvol, and then use the send stream to modify it. So, if you do this:

btrfs sub snap -r /@A /snaps/@A.1 btrfs send /snaps/@A.1 | btrfs receive /backups btrfs sub snap -r /@A /snaps/@A.2 btrfs send -p /snaps/@A.1 /snaps/@A.2 | btrfs receive /backups

the second receive will first snapshot /backups/@A.1 to /backups/@A.2, and then use the information in the send stream to make it look like /snaps/@A.2.

When you use -c, then receiver will simply use the clone range ioctl (i.e. reflink copies) from data held in the corresponding subvol. So, doing this:

btrfs sub snap -r /@A /snaps/@A.1 btrfs send /snaps/@A.1 | btrfs receive /backups cp --reflink=always /@A/bigfile /@B/bigfile.copy btrfs sub snap -r /@B /snaps/@B.1 btrfs send -c /snaps/@A.1 /snaps/@B.1 | btrfs receive /backups

the second receive will start with a blank subvolume, and build it up from scratch. The send will send all of the metadata of @B.1, but will leave out the data for @B.1/bigfile, because it’s already in the backups filesystem, and can be reflinked from there.

So if you use -c on its own (without -p), all of the metadata of the subvol is sent, but some of the data is assumed to exist on the far side.

If you use -p, then some of the metadata is assumed to exist on the other side as well, in the form of an earlier subvol that can be snapshotted.

How do I recover from a «parent transid verify failed» error?

For example:

parent transid verify failed on 29360128 wanted 1486656 found 1486662

If the second two numbers (wanted 1486656 and found 1486662) are close together (within about 20 of each other), then mounting with

-o ro,usebackuproot

may help. If it’s successful with a read-only mount, then try again without the ro option, for a read-write mount.

If the usebackuproot doesn’t work, then the FS is basically unrecoverable in its current state with current tools. You should use btrfs restore to refresh your backups, and then restore from them.

What does «parent transid verify failed» mean?

«Parent transid verify failed» is the result of a failed internal consistency check of the filesystem’s metadata.

The way that btrfs works — CoW, or Copy-on-Write — means that when any item of data or metadata is modified, it’s not overwritten in place, but instead is written to some other location, and then the metadata which referenced it is updated to point at the new location. The changed metadata is also updated in the same way: a new copy is written elsewhere, and the things that referenced that item are updated. This process ultimately bubbles up all the btrfs trees, until only the superblock is left to be updated. The superblock(s) are the only things which are overwritten in place, and each one can be done atomically. This process ensures that if you follow the filesystem structures downwards from the superblock, you will always see a completely consistent structure for the filesystem.

Now, if this cascade of writes happened for every single update, btrfs would be orders of magnitude slower than it is. So, for performance reasons, the updates are cached in memory, and every so often the in-memory data is written to disk in a consistent way, and the superblocks on the disk are then updated to point at the new structures. This update of the superblocks is called a transaction in btrfs. Each transaction is given a number, called the transid (or sometimes generation). These transids increase by one on every transaction.

Now, when writing metadata, every metadata block has the current transid embedded in it. The upwards-cascading effect of the CoW process means that in the metadata trees, the transid of every block in the metadata must be lower than or equal to the transid of the block above it in the tree. This is a fundamental property of the design of the filesystem — if it’s not true, then something has broken very badly, and the FS rightly complains (and may prevent the FS from being mounted at all).

How does this happen?

The fundamental problem identified by transid failures is that some metadata block is referenced by an older metadata block. This can happen in a couple of ways.

- The superblock got written out before it should have been, before the trees under it were completely consistent (i.e. before all the cached metadata in RAM was flushed to permanent storage), and then the FS was interrupted in writing out the remainder of the metadata. To ensure that this is the case, btrfs uses a feature called a barrier to impose an ordering on the writes to the hardware. The barrier should ensure that the superblock can’t get written out before all the other metadata has reached the permanent storage. However, (a) the hardware may not implement barriers correctly, or at all — most common on USB storage devices, but has also been seen directly on some drives and controllers, or (b) there might be a bug in btrfs (unlikely, because it’s tested quite thoroughly using tools written specifically to identify this problem).

- The data written to disk was modified (corrupted) in RAM before it was written out to disk. If the transid in a metadata block was modified, or a pointer to another block was changed in a way that happened to hit another metadata block (but an older one, or just the wrong one), then you can see transid failures. This could happen with a faulty computing device (bad RAM, CPU, PSU or power regulation), or it could happen as a result of a bug in some part of the kernel which allowed another part of the kernel to write on data it shouldn’t have written to.

If you see transids close together, then it’s probably the first case above, and mounting with -o usebackuproot may be able to step backwards and use an earlier superblock with a slightly older, non-broken set of trees in it.

If you see wildly different transids, or a transid which is hugely out of proportion, then you probably have the second case, and there’s little hope for in-place recovery (transids don’t increase very fast — once every 30s is the normal behaviour, although it might be somewhat faster than that with lots of snapshotting).

Subvolumes

What is a subvolume?

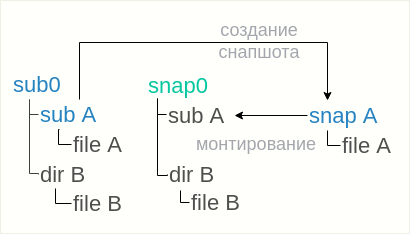

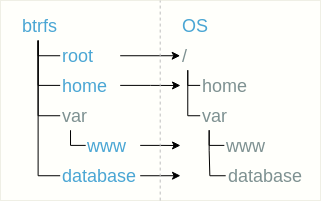

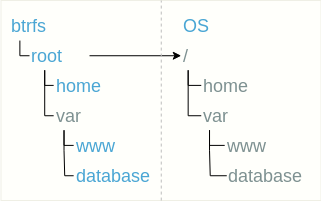

A subvolume is like a directory — it has a name, there’s nothing on it when it is created, and it can hold files and other directories. There’s at least one subvolume in every Btrfs filesystem, the top-level subvolume.

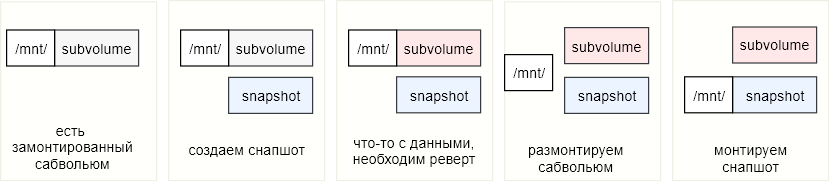

As well as being like directories, subvolumes can be mounted independently of the rest of the filesystem. They are also the unit of snapshotting: you can make an atomic snapshot of a single subvolume, but not a whole tree of them; you can’t make an atomic snapshot of anything smaller than a subvolume (like, say, a single directory).

Subvolumes can be given capacity limits, through the qgroups/quota facility, but otherwise share the single storage pool of the whole btrfs filesystem. They may even share data between themselves (through deduplication or snapshotting).

How do I find out which subvolume is mounted?

A specific subvolume can be mounted by -o subvol=/path/to/subvol option, but currently it’s not implemented to read that path directly from /proc/mounts. If the filesystem is mounted via a /etc/fstab entry, then output of mount command will show the subvol path, as it reads it from /etc/mtab.

Generally working way to read the path, like for bind mounts, is from /proc/self/mountinfo

27 21 0:19 /subv1 /mnt/ker rw,relatime - btrfs /dev/loop0 rw,space_cache

^^^^^^

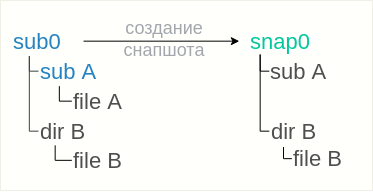

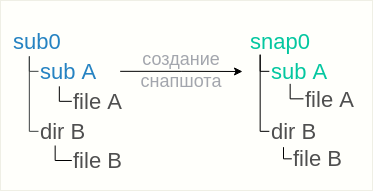

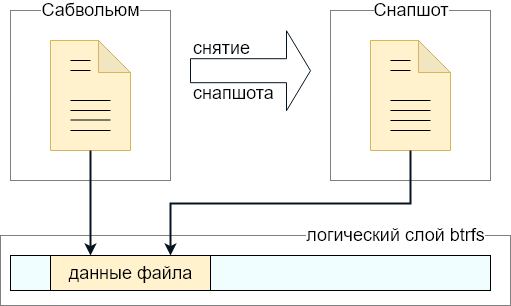

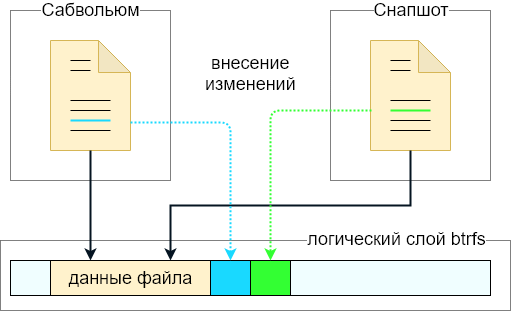

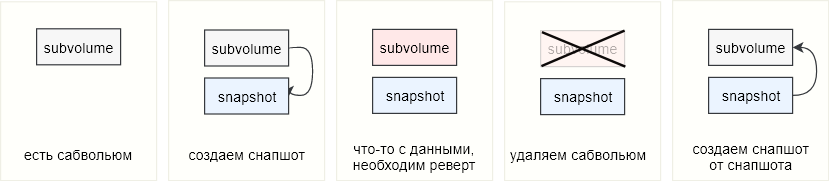

What is a snapshot?

A snapshot is a frozen image of all the files and directories of a subvolume. For example, if you have two files («a» and «b») in a subvolume, you take a snapshot and you delete «b», the file you just deleted is still available in the snapshot you took. The great thing about Btrfs snapshots is you can operate on any files or directories vs lvm when it is the whole logical volume.

Note that a snapshot is not a backup: Snapshots work by use of btrfs’s copy-on-write behaviour. A snapshot and the original it was taken from initially share all of the same data blocks. If that data is damaged in some way (cosmic rays, bad disk sector, accident with dd to the disk), then the snapshot and the original will both be damaged. Snapshots are useful to have local online «copies» of the filesystem that can be referred back to, or to implement a form of deduplication, or to fix the state of a filesystem for making a full backup without anything changing underneath it. They do not in themselves make your data any safer.

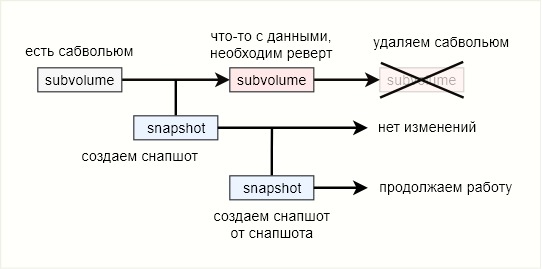

snapshot example