Memory gaps and errors refer to the incorrect recall, or complete loss, of information in the memory system for a specific detail and/or event. Memory errors may include remembering events that never occurred, or remembering them differently from the way they actually happened.[1] These errors or gaps can occur due to a number of different reasons, including the emotional involvement in the situation, expectations and environmental changes. As the retention interval between encoding and retrieval of the memory lengthens, there is an increase in both the amount that is forgotten, and the likelihood of a memory error occurring.

OverviewEdit

There are several different types of memory errors, in which people may inaccurately recall details of events that did not occur, or they may simply misattribute the source of a memory. In other instances, imagination of a certain event can create confidence that such an event actually occurred. Causes of such memory errors may be due to certain cognitive factors, such as spreading activation, or to physiological factors, including brain damage, age or emotional factors. Furthermore, memory errors have been reported in individuals with schizophrenia and depression. The consequences of memory errors can have significant implications. Two main areas of concern regarding memory errors are in eyewitness testimony and cases of child abuse.

Types of memory errorsEdit

BlockingEdit

The feeling that a person gets when they know the information, but can not remember a specific detail, like an individual’s name or the name of a place is described as the «tip-of-the-tongue» experience. The tip-of-the-tongue experience is a classic example of blocking, which is a failure to retrieve information that is available in memory even though you are trying to produce it.[2] The information you are trying to remember has been encoded and stored, and a cue is available that would usually trigger its recollection.[2] The information has not faded from memory and a person is not forgetting to retrieve the information.[2] What a person is experiencing is a complete retrieval failure, which makes blocking especially frustrating.[2] Blocking occurs especially often for the names of people and places, because their links to related concepts and knowledge are weaker than for common names.[2] The experience of blocking occurs more often as we get older; this «tip of the tongue» experience is a common complaint amongst 60- and 70-year-olds.[2]

TransienceEdit

Transience refers to forgetting what occurs with the passage of time.[3] Transience occurs during the storage phase of memory, after an experience has been encoded and before it is retrieved.[3] As time passes, the quality of our memory also changes, deteriorating from specific to more general.[3] German philosopher named Hermann Ebbinghaus decided to measure his own memory for lists of nonsense syllables at various times after studying them. He decided to draw out a curve of his forgetting pattern over time. He realized that there is a rapid drop-off in retention during the first tests and there is a slower rate of forgetting later on.[3] Therefore, transience denotes the gradual change of a specific knowledge or idea into more general memories.[4]

AbsentmindednessEdit

Absentmindedness is a gap in attention which causes memory failure. In this situation the information does not disappear from memory, it can later be recalled. But the lack of attention at a specific moment prevents the information from being recalled at that specific moment. A common cause of absentmindedness is a lack of attention.[clarification needed] Attention is vital to encoding information in long-term memory. Without proper attention, material is much less likely to be stored properly and recalled later.[5] When attention is divided, less activity in the lower left frontal lobe diminishes the ability for elaborative memory encoding to take place, and results in absentminded forgetting. More recent research has shown that divided attention also leads to less hippocampal involvement in encoding.[5] A common example of absentmindedness is not remembering to carry out actions that had been planned to be done in the future, for example, picking up grocery items, and remembering times of meetings.[6]

False memoriesEdit

False memories, sometimes referred to as confabulation, refer to the recollection of inaccurate details of an event, or recollection of a whole event that never occurred. Studies investigating this memory error have been able to successfully implant memories among participants that never existed, such as being lost in a mall as a child (termed the lost in the mall technique) or spilling a bowl of punch at a wedding reception.[7] In this case, false memories were implanted among participants by their family members who claimed that the event had happened. This evidence demonstrates the possibility of implanting false memories on individuals by leading them to remember such events that never occurred. This memory error can be particularly worrisome in judicial settings, in which witnesses may have false recollections of a crime after it has happened, especially when told by others that particular things may have happened which did not.[8] Another area of concern regarding false memories is in cases of child abuse.

Problem of biasEdit

The problem of bias, which is the distorting influences of present knowledge, beliefs, and feelings on recollection of previous experiences.[9] Sometimes what people remember from their past says less about what actually happened than about what they personally believe, feel, and the knowledge they have acquired at the present time.[9] An individual’s current moods can bias their memory recall, researchers have found.[9] There are three types of memory biases, consistency bias, change bias and egocentric bias.[9] Consistency bias is the bias to reconstruct the past to fit the present.[9] Change bias is the tendency to exaggerate differences between what we feel or believe in the present and what we previously felt or believed in the past.[9] Egocentric bias is a form of change bias, the tendency to exaggerate the change between the past and the present in order to make ourselves look good in any given situation.[9]

Misinformation effectEdit

The misinformation effect refers to the change in memory due to the presentation of information that is relevant to the target memory, such as leading questions or suggestions.[10] Memories are likely to be altered when questions are worded differently or when inaccurate information is presented. For example, in one experiment participants watched a video of an automobile accident and were then asked questions regarding the accident. When asked how fast the automobiles were driving when they smashed into each other, the speed estimate was higher than when asked how fast the automobiles were driving when they hit, bumped or collided into each other. Similarly, participants were more likely to report there being shattered glass present when the word smashed was used instead of other verbs.[11] Evidently, memory recollection can be altered with misleading information after the event.

Source confusionEdit

Source confusion or unconscious transference,[12] involves the misattribution of the source of a memory. For instance, an individual may recall seeing an event in person when in reality they only witnessed the event on television.[12] Ultimately, the individual has an inability to remember the source of information in which the content and the source become dissociated. This may be more likely for more distant memories, such as childhood memories.[7] In more severe cases of source confusion, you can take fictional stories you heard from when you were younger and assimilated these stories being your childhood. For example, say your father told you stories about his life when he was a child every night before you went to sleep when you were a child. When you grow up, you might mistakenly remember these stories your dad told you as your own and integrate them into your childhood memories.[13]

Imagination inflationEdit

Imagination inflation refers to when a person remembers details of a memory that are exaggerated versions of the actual event or remember an entire memory that never occurred due to the act of imagination.[14] That is, when one imagines an event occurring, their confidence that this event actually did occur increases. One reason for this may be due to the act of imagination increasing the familiarity of the event. When the event seems more familiar, it may become more likely for people to report it actually occurring. For instance, in an experiment participants were asked to imagine playing inside and then running outside toward a window, falling and breaking it, while other participants did not imagine anything. Participants who had imagined this scenario reported an increased level of confidence that the event had actually happened in comparison to those who did not imagine the event.[7] This error can be caused simply by imagining an event.

Deese–Roediger–McDermott (DRM) paradigmEdit

Deese-Roediger-McDermott paradigm refers to the incorrect recall of features of an event that were not actually present, due to the features being related to a common theme.[15] This paradigm has been demonstrated with the use of word lists and subsequent recognition tests. For example, experiments have shown that if a research participant is presented with the words: bed rest awake tired dream wake snooze snore nap yawn drowsy, there is a high likelihood that the participant will falsely recall that the word sleep was in the list of words. These results show a significant illusion in memory, in which people remember items that were never presented simply due to their relation with other items in a common theme.[1]

Schematic errorsEdit

Schematic errors refer to the use of a schema to help reconstruct parts of an experience that cannot be remembered. This may include parts of the schema that did not actually take place, or aspects of a schema that are stereotypical of an event.[16] Schemas can be described as mental guidelines (scripts) for events that are encountered in daily life.[16] For example, when going to the gas station, there is a general pattern of how things will occur (i.e. turn car off, get out of car, open gas tank, punch the gas button, put nozzle into the tank, fill up the tank, put the nozzle back, close the tank, pay, turn car on, leave). Schemas make the world more predictable, allowing expectations to be formed of how things will enfold and to take note of things that happen out of context.[16] However, schemas also allow for memory errors, in that if certain aspects of a scene or event are missing from memory, people may incorrectly remember having actually seen or experienced them because they are usually a regular aspect of the schema. For example, an individual may not remember paying the waiter, but may believe they have done so, as this is a regular step in the script of going to a restaurant. Similarly, a person may recall seeing a fridge in a picture of a kitchen, even if one was not actually depicted due to existing schemas which suggest that kitchens almost always contain a fridge.[16]

Intrusion errorsEdit

Intrusion errors refer to when information that is related to the theme of a certain memory, but was not actually a part of the original episode, become associated with the event.[17] This makes it difficult to distinguish which elements are in fact part of the original memory. One idea regarding how intrusion errors work is due to a lack of recall inhibition, which allows irrelevant information to be brought to awareness while attempting to remember.[18] Another possible explanation is that intrusion errors result from a lack of new context integration into a viable memory trace, or into an already existing memory trace that is related to the appropriate memory.[18] More explanations involve the temporal aspect of recall, meaning that as the time difference between the study periods of different lists approaches zero, the amount of intrusions between the lists tends to increase,[19] the semantic aspect, meaning that the list of target words may have induced a false recall of non-target words that happen to have a similar or same meaning as the targets,[20] and the similarity aspect, for example subjects who were given list of letters to recall were likely to replace target vowels with non-target vowels.[21]

Intrusion errors can be divided into two categories. The first are known as extra-list errors, which occur when incorrect and non-related items are recalled, and were not part of the word study list.[18] These types of intrusion errors often follow the DRM Paradigm effects, in which the incorrectly recalled items are often thematically related to the study list one is attempting to recall from. Another pattern for extra-list intrusions would be an acoustic similarity pattern, this pattern states that targets that have a similar sound to non-targets may be replaced with those non-targets in recall.[22] One major type of extra-list intrusions is called the «Prior-List Intrusion» (PLI), a PLI occurs when targets from previously studied lists are recalled instead of the targets in the current list. PLIs often follow under the temporal aspect of intrusions in that since they were recalled recently they have a high chance of being recalled now.[19] The second type of intrusion error is known as intra-list errors, which is similar to extra-list errors, except it refers to irrelevant recall for items that were on the word study list.[18] Although these two categories of intrusion errors are based on word list studies in laboratories, the concepts can be extrapolated to real-life situations. Also, the same three factors that play a critical role in correct recall (recency, temporal association and semantic relatedness) play a role in intrusions as well.[19]

Time-slice errorsEdit

Time-slice errors occur when a correct event is in fact recalled; however the event that was asked to be recalled is not the one that is recalled. In other words, the timing of events is incorrectly remembered.[23] As discovered in a study by Brewer (1988), often the event or event details that are recalled occurred within a short time proximity to the memory required to be recalled.[23] There are three possible theories as to why time-slice errors occur. First, they may be a form of interference, in which the memory information from one time impairs the recall of information from a different time.[24] (see interference below). A second theory is that intrusion errors may be responsible, in that memories revolving around a similar time period thus share a common theme, and memories of various points of time within that larger time period become mixed with each other and intrude on each other’s recall. Last, the recall of memories often have holes due to forgotten details. Thus, individuals may be using a script (see schema errors) to help fill in these holes with general knowledge of what they know happened around this time. Since scripts are a time-based knowledge structure, which puts details of a memory in sequence to make it easier to understand, time-slice errors can occur if a detail is mistakenly placed in the wrong sequence.[24]

Personal life effectsEdit

Personal life effects refer to the recall and belief in events as declared by family members or friends for having actually happened.[25] Personal life effects are largely based on suggestive influences from external sources, such as family members or a therapist.[7] Other influential sources may include media or literature stories which involve details that are believed to have been experienced or witnessed, such as a natural disaster close to where one resides, or a situation that is common and could have occurred, such as getting lost as a child. Personal life effects are most powerful when claimed to be true by a family member, and even more powerful when a secondary source confirms the event having happened.[7]

Personal life effects are believed to be a form of source confusion, in which the individual cannot recall where the memory is coming from.[26] Therefore, without being able to confirm the source of the memory, the individual may accept the false memory as true. Three factors may be responsible for the implantation of false autobiographical memories. The first factor is time. As time passes, memories fade. Therefore, source confusion may result due to time delay.[7] The second factor is the imagination inflation effect. As the amount of imagination increases, so does one’s familiarity for the contents of the imagination. Thus, source confusion may also occur due to the individual confusing the source of the memory for being true, when in fact it was imaginary.[26] Lastly, social pressure to recall the memory may affect the individual’s belief in the false memory. For example, with increase in pressure, the individual may lower their criteria for validating a memory, and come to accept a false memory for being true.[26] Personal life effects can be extremely crucial to recognize in cases of recovered memories, especially those of abuse, in which the individual may have been led to believe they had been abused as a child by a therapist during psychological therapy, when in fact they had not been. Personal life effects can also be important in witness testimonies, in which suggestions from authorities may incorrectly implant memories regarding witnesses a particular detail about a crime (see the Childhood Abuse and Eye Witness Testimony sections below).

Memory error relating to foodEdit

In a study done by J. Mojet and E.P. Köster, participants were asked to have a drink, yoghurt, and some biscuits for breakfast. A few hours later, they were asked to identify and the items they had during breakfast out of five variations of the drinks, yoghurts, and biscuits. The results showed that participants remember the texture of the foods much better than for fatty content, although they could discern the difference of both among the different items. Participants were also most certain about foods that they did not have during breakfast, but were the least certain about foods that they said were in their breakfast and about foods that were in their breakfast but were not recognized. This suggests that incidental and implicit memory for foods are more focused on discerning new and potentially unsafe food rather than remembering the details of familiar foods.[27]

CausesEdit

Cognitive factorsEdit

Spreading activationEdit

One theory on how memory works is through a concept called spreading activation. Spreading activation refers to the firing of connected nodes in associated memory links.[28] The theory states that memory is organized in a theoretical web of associated ideas and related features. Each feature, or node, is connected to related features or ideas, which in turn are themselves connected to other related nodes.[29]

Spreading activation can also demonstrate how memory errors may occur. As the network of memory associations increases in the number of connections–the connection density–the likelihood of memory gaps and errors occurring also increases. Put simply, the amount of activation a secondary connection receives depends on how many connections the initial node has associated with it. This is because the initial node must divide the amount of activation it spreads to related nodes by the number of connecting nodes it is associated with. If node 1 has three connecting nodes, and node 2 has 15 connecting nodes, the three connecting nodes from node 1 will receive greater activation levels (the activation level is divided less) than for the 15 connecting nodes from node 2, and the components of these nodes will be more easily brought to mind. What this means is that, with more connections a node has, the more difficulty there is bringing to mind one of its connecting features.[30] This can lead to memory errors, in that if the connection density is so great that there is not enough activation reaching the secondary nodes, then the person may not recall a target memory that is actually present, and a memory error occurs.

Activation levels to secondary nodes is also determined by the strength of the association to the primary node.[28] Some connections have greater association with the primary node (e.g. fire truck and fire or red, versus fire truck and hose or Dalmatian), and thus will receive a greater portion of the divided activation than less associated connections. Thus, associations that receive less activation will be out-competed by associations with stronger connections, and may fail to be brought into awareness, again causing a memory error.

Connection densityEdit

The connection densities, or neighbourhood densities[31] of memory arrangements help distinguish which elements are a part of, or related to, the target memory. As the density of neural networks increases, the number of retrieval cues (associated nodes) also increases, which may allow for enhanced memory of the event.[30] However, too many connections can inhibit memory in two ways. First, as described under the sub-section Spreading Activation, the total activation being spread from node 1 to connecting nodes is divided by the number of connections. With a greater number of connections, each connecting node receives less activation, which may result in too little activation for the memory cue to be brought to awareness. Connection strength, in which more strongly connected associations receive more activation than less-related associations, may also prevent specific connections from being brought to awareness due to being out-competed by the stronger associations.[31] Second, with more connections branching from various other nodes, there is a greater probability of linking associated connections of different memories together (transplant errors) so that memory errors occur and incorrect features are recalled.

Retrieval cuesEdit

A retrieval cue is a type of hint that can be used to evoke a memory that has been stored but cannot be recalled. Retrieval cues work by selecting traces or associations in memory that contain specific content. With regards to the theory of spreading activation, retrieval cues use associated nodes to help activate a specific or target node.[32] When no cues are available, recall is greatly reduced, leading to forgetting and possible memory errors. This is called retrieval failure, or cue-dependent forgetting.

Retrieval cues can be divided into two subsets, although they are by no means used independent of each other. The first are called feature cues, in which information of the content of the original memory, or related content, is used to aid recall.[32] The second category is context cues, in which information based on the specific context (environment) in which the memory or learning occurred is used to aid recall.[32]

Although retrieval cues are usually helpful in helping to remember something, they can produce memory errors in three ways. First, incorrect cues can be used, leading to recall of an incorrect memory. Second, although the correct retrieval cues may be used, they may still produce an incorrect memory. This is likely to occur with high connection densities, in which the incorrect (but associated) node was activated and thus recalled, instead of the target memory. Third, the retrieval cue chosen may be correct and associated with the target memory, but it may not have a strong connection to the target memory, and thus may not produce enough activation to produce the target memory.

Encoding specificityEdit

Encoding specificity is when retrieval is successful to the extent that the retrieval cues used to help recall, match the cues the individual used during learning or encoding.[33] Memory errors due to encoding specificity means that the memory is likely not forgotten, however, the specific cues used during encoding the primary event are now unavailable to help remember the event. The cues used during encoding are dependent on the environment of the individual at the time the memory occurred. In context-dependent memory, recall is based on the difference between the encoding and recall environments.[34] Recall for items learned in a particular context is better when recall occurs in the same place as when the initial memory occurred. This is why it is sometimes useful to “return to the scene of the crime” to help witnesses remember details of a crime, or for explaining why going to a specific location such as a residence or community setting, may lead to becoming flooded with memories of things that happened in that context. Recall can also depend on state-dependency, or the conditions of one’s internal environment, at both the time of the event and of recall.[35] For example, if intoxicated at the time the memory actually occurred, recall for details of the event is greater when recalling while intoxicated. Associated with state-dependency, recall can also depend on mood-dependency, in which recall is greater when the mood for when the memory occurred matches the mood during recall.[23] These specific dependencies are based on the fact that the cues used during the initial event can be specific to the context or state one was in. In other words, various features of the environment (both internal and external) can be used to help encode the memory, and thus become retrieval cues. However, if the context or state changes at the time of recall, these cues may no longer be available, and thus recall is hindered.

Transfer-appropriate processingEdit

Memory errors can also depend on the method of encoding used when initially experiencing or learning information, known as transfer-appropriate processing.[36] Encoding processes can occur at three levels: visual form (the letters that make up a word), phonology (the sound of a word), and semantics (the meaning of the word or sentence). With relation to memory errors, the level of processing at the time of encoding and at the time of recall should be the same.[37] Although semantic processing generally produces greater recall that shallower levels of processing, a study by Morris et al. demonstrated that what might be the key factor to greater recall is transfer-appropriate processing–when the level of processing at the original memory/learning time matches the level of processing used to help recall. In other words, if learning occurred by rhyming the target words to other words, then recall is best if testing is also at the phonological level of processing, such as a rhyming recognition test. Thus, memory errors can occur when the levels of processing between encoding and recall do not match.[37]

InterferenceEdit

Interference occurs when specific information inhibits learning and /or recall for a specific memory.[38] There are two forms of interference. First, proactive interference has to do with difficulty in learning new material based on the inability to override information from older memories.[39] In such cases, retrieval cues continue to be associated and aimed at recalling previously learned information, affecting the recall of new material. Retroactive interference is the opposite of proactive interference, in which there is difficulty in the recall of previously learned information based on the interference of newly acquired information. In this case, retrieval cues are associated with the new information and not the older memory.[40] thus affecting recall of older material. Interference of either form can produce memory errors, in which there is interference with the recall of material. In other words, previously used retrieval cues are no longer associated with prior memories, and thus memory confusion or even an inability to recall the memory can occur.

Physiological factorsEdit

Brain damageEdit

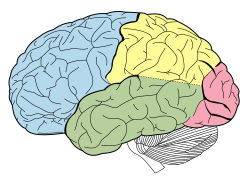

| Lobes of the human brain |

|---|

|

Frontal lobe Temporal lobe Parietal lobe Occipital |

| Damage in the temporal lobe (green) and frontal lobe (blue) are associated with resulting memory errors |

Neuroimaging studies have provided evidence for links between brain damage and memory errors. Brain areas implicated include the frontal lobe and medial-temporal regions of the brain. Such damage may result in significant confabulations and source confusion.[8]

The prefrontal cortex is in charge of making heuristic judgments and systematic judgments, which involve analyzing the qualities of memories and the retrieval and evaluation of supporting or disconfirming information.[8] Thus, if the frontal region is damaged, these abilities will be impaired and memories may not be retrieved or evaluated correctly. For example, one patient who suffered frontal lobe damage after an automobile accident reported memories of the support his family provided for him after the accident, which in reality, was false.[41]

The temporal region of the brain contains the hippocampus, which plays a significant role in memory.[42] Thus, damage in this region may impair the function of this brain structure and result in memory problems.

AgeEdit

Studies have shown that the likelihood of memory errors occurring increases as age increases. Possible reasons for this are increased source confusion for the event and findings that older persons have decreased levels of processing when first presented with new information.[43][44] Source confusion refers to the inability to distinguish how one came upon different information. Older individuals can become confused with where they learnt information (e.g. TV, radio, newspaper, word of mouth, etc.), who presented them with the information (e.g. which of two experimenters presented them with facts and which presented them with irrelevant information), and whether the information came from an imagined source, and is thus not factual, or a real world source.[44] This in itself is a form of memory error but can also create larger memory errors. When an older individual is confused whether the information is factual or was imagined they can begin to accept imagined memories as real and thus begin to rely on new false information.[44]

Levels of processing refers to the manner in which someone encodes information into their memory and how deeply it is encoded.[44] There are three different levels of processing ranging from shallow to deep, deep being stored in long-term memory for a longer period and thus better remembered. The three levels are; visual form, being the shallowest form, phonology, being a medium level of processing, and semantics (meaning), which is the deepest form of processing.[44] The visual form of processing relies on the ability to see information and break it down into its components (e.g. see the word «dog», composed D, O, and G). Phonology relies on creating links to information through sound such as cues and tricks for memory (e.g. Dog rhymes with Fog).[44] Finally, semantics refer to the creation of meaning behind information such as adding detail to allow the information to create links throughout our memory with other memories and thus be held in long-term memory for a longer period (e.g. A dog is a four-legged pet that often chases cats and chews on bones).[44] Older individuals often begin to lose the quick ability to add meaning to new information, which leads to shallower processing and easier forgetting of the information gained.[44] Both of these possible factors can decrease the validity of the memory due to retrieval for details of the event being more difficult to perform. This leads to details of memories being confused with others or lost completely, which lead to many errors in recall of a memory.

EmotionEdit

The emotional impact of an event can have a direct impact on how the memory is first encoded, how it is later recalled, and what details of the event are accurately recalled. Highly emotional events tend to be recalled easily due to their emotional impact,[45] as well as their distinctiveness relative to other memories (highly emotional events do not occur on a regular basis, and thus are easily separated from other events that are more commonly met). Emotional events may affect memory not only because of their distinctiveness, but also because of their arousal on the individual.[46] Studies have found that prime or central features of such highly emotional events tend to be accurately recalled, whereas subtle details of the events are not remembered, or are remembered with vague consistency. Memory errors related to highly emotional events are influenced in ways such as:

- Whether the event was positive or negative in nature — The nature of the event can affect memory, negative events tend to be remembered with greater accuracy than positive events.[23]

- Implicit theories of consistency and change — This term was coined by Ross (1989), and is used to describe the phenomena of memory change based on the belief of how the person felt at the time of the event compared to their current feelings about it.[23] In other words, the memory of one’s emotion towards an event can change depending on their current emotional state toward the same event. If a person believes their feelings at both times continue to be the same, then the current emotion to «remember» how they felt about the event at a previous time is used. If feelings are believed to have changed, then recall of the emotional involvement in the past event is adjusted to the current feelings.

- Intrusion errors — This term refers to the inclusion of details that may have been commonly experienced in the event, but not by the individual. For example, in the September 11 terrorist attacks, many people may state that they remember hearing about the attacks on the television news, as this was a common way of finding out this information, whereas they may have actually heard about it from a neighbour or on the radio.[47]

- Mood-congruency — Items/events are better recalled when the mood of the individual at the time of the event and the time of recall are the same. Thus, if the mood at the time of recall does not match the mood experienced at the time the event occurred, there is an increased chance that complete recall will be affected/interrupted.[48]

Memory errors in Abnormal PsychologyEdit

Abnormal psychology is the branch of psychology that studies unusual patterns of behavior, emotion and thought, which may or may not be understood as a mental disorder. Memory errors can commonly be found in types of abnormal psychology such as Alzheimer’s disease, depression, and schizophrenia.

Alzheimer’s diseaseEdit

Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by progressive memory impairment and decline, usually beginning short-term memory.[49] As it is a progressive disease, Alzheimer’s usually begins with memory errors before proceeding to long-term memory stores. One form of memory error occurs in contrast to the theory of retrieval cues in being a reason for the occurrence of memory errors. As noted above, memory errors may be due to the lack of cues that can trigger a memory trace and bring it to awareness. However, studies have shown that the opposite may be true for patients with Alzheimer’s, such that cues may actually decrease perform on

priming tasks.[50] Patients also demonstrate errors known as misattribution errors, otherwise known as source confusion. However, studies show that these misattribution errors are dependent on whether the task is a familiarity or recollection task.[51]

Although patients tend to exhibit a higher level of false recognitions than control groups,[52] researchers have shown that they may exhibit less false-recognition early in the test due to familiarity being slower to develop. However, the observation of increasing instances of misattribution errors can be seen once familiarity does occur.[51] This may be related to the retrieval cue speculation, in that familiar memories often contain cues we know, and thus may be the reason why familiarity can contribute to memory errors. Lastly, many studies have shown that Alzheimer’s patients commonly suffer from intrusion errors. Relative to the findings that retrieval cues may actually hurt recall performance, one study by Kramer et al. showed that intrusions are most commonly associated with cue-recall tasks.[53] This study suggests that cues may lead to intrusions because patients may have a difficult time distinguishing between cues and distractions,[53] which may help explain why cues increase memory errors in patients with Alzheimer’s. Since verbal intrusions are a common aspect of Alzheimer’s,[54] some researchers believe that this characteristic may be helpful in the diagnosis of the disease.[55]

DepressionEdit

Memory errors can occur in patients with depression or with depressive symptoms. Patients with depressive symptoms have a tendency to experience what is known as the negative triad, which is the perspective use of negative schemas and self-concepts to relate to the external world. Due to this negative triad, depressive patients have a tendency to have a much greater focus on, and recall for, negative details and events over positive ones. This may lead to memory errors related to the positive details of memories, impairing the accuracy or even complete recall of such memories. Depressed patients also experience deficits in psychomotor speed and in free recall of material both immediate and delayed. This suggests that material has been encoded but that patients are particularly impaired with regard to search and retrieval processes.[56] Diverse aspects of memory such as short-term memory, long-term memory, semantic memory and implicit memory, have been studied and linked to depression. Short-term memory, a temporary store for newly acquired information, seems to show no major impairments in the case of depressive patients who do seem to complain about poor concentration, which by itself can cause simple memory errors.[56]

Long-term memory, large capacity able to retain information over long periods of time, does however show impairment in the case of depressed individuals. They tend to have difficulties in recall and recognition for both verbal and visuo-spatial material with intervals of a few minutes or even hours creating complex memory errors in relation to speech and surrounding details.[56] Individuals suffering with depression also showed a specific deficit in retrieving information meaningfully organized in their semantic memory, conceptual knowledge about the real world.[56] Therefore, depressive patients can show memory errors for the most meaningful events in their lives, unable to recall these specific moments vividly like someone not suffering from depression might. In the case of implicit memory, when previous information influences ongoing responses, there has been little to no proof of a deficit in relations to depressed individuals.[56]

SchizophreniaEdit

Memory errors, specifically intrusion errors and imagination inflation effects, have been found to occur in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. Intrusion errors can commonly be found in the recall portion of a memory test when a participant includes items that were not on the original list that was presented.[57] These types of errors are linked to problems with self-monitoring, increased positive and disorganized symptoms (confusion within the brain), and poor executive functioning.[57] Intrusion errors are found to be more likely in patients with positive schizophrenic symptoms, which involve an excess of normal bodily functions (e.g. delusions), versus negative schizophrenic symptoms, which involve a decrease in normal bodily functions (e.g. refusal to speak).[58] Possible reasons for this are reduced function in the central executive of the working memory, as well as defects in self-reflectivity, organization and reasoning. Self-reflectivity is the ability to recognize and reason about one’s own thought process, recognize that one has thoughts, and that those thoughts are one’s own and differentiate between cognitive operations.[57] Self-reflectivity has been shown to be one of the biggest deficits faced by schizophrenics and data suggests that verbal memory intrusions are linked to deficits in the ability to identify, organize, and reason about one’s own thoughts in patients with schizophrenia.[57]

Imagination inflation effects were also common memory errors in patients with schizophrenia. This effect refers to events that individuals have imagined so vividly in their minds that this adds belief to the fact that the event truly occurred, although it did not. Possible reasons for this are increased source confusion and/or decreased source recollection of an event, which shows poor use of source-monitoring processes.[59] Source-monitoring processes allow one to distinguish between a memory that we may believe has happened because it seems familiar and one that has truly occurred. In the case of schizophrenics, whose abilities to reason through their thoughts is impaired, something that they have imagined and thus, seems familiar can easily be mistaken for an actual event, especially in the case of quick heuristic processes and snap judgments.[59] Continuously imagining an action or event makes this action more and more familiar thus making it harder for a patient with schizophrenia to distinguish its source, questioning whether it is familiar because they have imagined it or if it is familiar because it happened. This leads to many memory errors for these individuals who are led to believe by their imagination of the event that it is real, has occurred and thus is stored in their memory for that reason.[59]

Consequences of memory errorsEdit

Memory errors often lead to the belief of new memories, which are problematic. In the case of eyewitness testimony new false memories can often lead to wrong information and lack of conviction or wrongful conviction of individuals. Also in the case of child abuse, memory errors can lead to the creation of false traumatic childhood memories, which can lead to false accusations and loss of trust.

Eyewitness testimonyEdit

Memory errors can occur in eyewitness testimonies due to a number of features commonly present in a trial, all of which may influence the authenticity of the memory, and may be detrimental to the outcome of the case at hand.

Such features include:

- Leading questions

- refers to how wording of questions can influence how an event is remembered. This can result from a misinformation effect or an imagination inflation effect.[60] The misinformation effect occurs when information is presented after the events in question have occurred which leads to memory errors in later retrieval.[61] Studies have suggested that witnesses may misattribute accuracy to misleading information because the sources of misleading information and witnessed information become confused.[61] Misleading information can be acquired through reading of the newspaper, watching the news, being interviewed or when sitting in the courthouse during the trial. When witnesses are asked to recall specific details of an event they can begin to doubt their memory, which can cause memory errors. Misinformation can manifest itself as a memory leading the individual to believe it as true and witnesses may also begin to doubt their own memories of the event deciding instead that they must be wrong.[61] Memory errors also occur through the imagination inflation effect. As stated earlier, the imagination inflation effect takes place when an individual imagines an event to the point where it is believed as a memory of an actual event.[60] During trial, witnesses hear many different possible occurrences of events and are led to imagine these situations. Through imagining and rehearsal of the occurrences, witnesses may begin to see vividness and validity in the stories simply from rehearsal, not factual memories.[60] This can create problems for witnesses when trying to distinguish between imagined events and the actual occurrence of the events. Small but largely significant details become easily mixed and these occurrences of memory errors can make or break a trial.

- Weapons Focus Effect

- refers to the fact that witnesses are highly likely to pay close attention to the weapon being used during an event, which creates a reduction in the ability to remember other details regarding the crime.[62] This can in turn create memory errors leaving the witness less able to remember details such as what the assailant was wearing or what distinctive features could be found on their body or face. One explanation for why witnesses tend to gravitate toward the weapon being used is said to be that the arousal of the witness is increased.[63] When arousal becomes increased the number of perceptional cues being utilized by the brain decreases.[63] This allows the individual to focus on the weapon cue and ignore other cues such as distinct scars or a bright red shirt. The weapons focus effect can also refer to how the report of the use of weapons in the case can influence the memory of the event, leading to a false memory of having heard a weapon being fired even if the witness did not.[63] For example, if a newspaper reports that the victim was beaten with a hammer, upon reading this, the witness will begin to believe that a hammer was in fact used, even if they at no point saw a hammer. This can cause many memory errors and conflict of stories for witnesses. As a society we believe that newspapers or televised news reports have fact behind them. If they report the hammer being used, a witness might begin to second-guess their memory wondering if they missed the hammer or failed to remember that detail.[62] Also, their story may become mixed with the media’s representation of the story and the knife that they did see will be forgotten and instead be replaced with the hammer that was reported.[63]

- Familiarity Effect

- refers to the tendency of individuals to develop a preference for things simply because they are familiar.[64] This can leave an individual to identify familiar people as guilty, even if they are not. When we are continuously exposed to the same object or person we begin to develop a positive attraction towards said object or person. Simply their familiarity creates a positive sense when re-exposed to the individual or object. In reality one can know very little about a person but by seeing them over and over again can gain unconscious positive recall for their face. This can create memory errors when individuals are asked to identify a criminal and someone familiar to them is placed in the line up. When a familiar face is in among the individuals that the witness is being asked to study, the witness will find himself or herself gravitating towards the familiar face whether or not this is who they witnessed committing the crime. This leaves them more likely to ignore the cues that are leading them towards other individuals and concentrate on the familiar face, resulting in a false accusation. The sense of familiarity can play a large role in the identification of criminals but when the familiarity of a criminal is mixed in with the familiarity of other individuals, choosing the right person can become quite difficult.

Child abuseEdit

Memory errors regarding the recovery of repressed childhood abuse can occur due to post-event suggestions from a trusted source, such as a family member, or more commonly, a mental health professional. Due to possible relationships between childhood abuse and mental illness later in life, some mental health professionals believe in the Freudian theory of repressed memories as a defense mechanism for the anxiety that recall of the abuse would cause. Freud said that repression operates unconsciously in individuals who are not able to recall a threatening situation or may even forget that the abusive individual was ever part of their lives. Therefore, mental health professionals will sometimes seek to uncover possible instances of childhood abuse in patients, which may lead to suggestibility and cause a false memory of childhood abuse to arise, in an attempt to seek a cause to a mental illness.[65] No matter the confidence in the memory, this does not necessarily equate to the memory being true. This is an example of the misinformation effect and false memory effect. The fact that memories are not retrieved as whole entities but rather are reconstructed from information remaining in memory and other related knowledge make them easily susceptible to memory errors.[66] This explains why working with mental health professionals and leading questions can sometimes manifest false memories by creating knowledge of possible events and asking individuals to focus on if these events actually took place.[67] Individuals begin to overthink these situations visualizing them in their mind and overanalyzing them. This in turn leads to the belief of situations and vivid memories. Patients are left with memories they believe are real and new events from their childhood which can lead to stress and trauma in their adult life and loss of relationships with those who are believed to be the abuser.

See alsoEdit

- Amnesia

- False memory syndrome

- Memory implantation

- Memory loss

- Memory and aging

- Memory bias

- Memory conformity

- Kleptomnesia

ReferencesEdit

- ^ a b Roediger, H. L., III, & McDermott, K. B. (1995). Creating false memories: Remembering words not presented in lists. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 21, 803–814

- ^ a b c d e f Schacter, Daniel L. (2011). Psychology Second Edition. New York: Worth Publishers. pp. 246. ISBN 978-1-4292-3719-2.

- ^ a b c d Schacter, Daniel (2011). Psychology 2nd Ed. New York: Worth Publishers. p. 243.

- ^ Schacter, Daniel L.,[«Psychology 2nd Ed.»],»Worth Publishers»,2009,2011.

- ^ a b Schacter, Daniel L., Daniel T. Gilbert, and Daniel M. Wegner. «Chapter 6: Memory.» Psychology. ; Second Edition. N.p.: Worth, Incorporated, 2011. 244-45.

- ^ Schacter, Daniel L., Daniel T. Gilbert, and Daniel M. Wegner. «Chapter 6: Memory.» Psychology. ; Second Edition. N.p.: Worth, Incorporated, 2011. 245.

- ^ a b c d e f Loftus, E. (1997). Creating false memories. Scientific American, 277, 70–75

- ^ a b c Johnson, M. & Raye, C. (1998). False memories and confabulation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 2(4), 137–145

- ^ a b c d e f g Schacter, Daniel L. (2011). Psychology Second Edition. New York: Worth Publishers. pp. 253–254. ISBN 978-1-4292-3719-2.

- ^ Loftus, E. F. & Hoffman, H. G. (1989). Misinformation and memory, the creation of new memories. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 118(1), 100–104

- ^ Loftus, E. F. & Palmer, J. C. (1974). Reconstruction of automobile destruction. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 13, 585–589

- ^ a b Deffenbacher, K.A., Bornstein, B.H., & Penrod, S.D. (2006). Mugshot exposure effects: Retroactive interference, mugshot commitment, source confusion, and unconscious transference. Law and Human Behaviour, 30(3), 287–307

- ^ Daniel L. Schacter, «Searching for memory: the brain, the mind, and the past», (New York, 1996)

- ^ Mazzoni, G. & Memon, A. (2003). Imagination can create false autobiographical memories. Psychological Science, 14(2), 186–188

- ^ Deese, J. (1959). On the prediction of occurrence of particular verbal intrusions in immediate recall. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 58, 17–22

- ^ a b c d Kleider, H.M., Pezdek, K., Goldinger, S.D., & Kirk, A. (2008). Schema-driven source misattribution errors: Remembering the expected from a witnessed event. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 22, 1–20

- ^ Jacobs, D. (1990). Intrusion errors in the figural memory of patients with Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s disease. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 5, 49–57.

- ^ a b c d Stip, E., Corbière, M., Boulay, L. J., Lesage, A., Lecomte, T., Leclerc, C., Richard, N., Cyr, M., & Guillem, F. (2007). Intrusion errors in explicit memory: Their differential relationship with clinical and social outcome in chronic schizophrenia. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 12(2), 112–127

- ^ a b c Kahana et al. (2006). Temporal Associations and Prior list intrusions in Free Recall.

- ^ Smith, Troy, A., Kimball, Daniel, R. Kahana, Michael, J. (2007). The fSAM Model of False Recall.

- ^ Wickelgren, Wayne, A., (1965. Similarity and Intrusions in Short Term Memory for Consonant-Vowel Digrams.

- ^ Wickelgren, Wayne, A., (1965). Acoustic Similarity and Intrusion Errors in Short Term Memory.

- ^ a b c d e Hyman Jr., I.E., & Loftus, E.F. (1998). Errors in autobiographical memory. Clinical Psychology Review, 18(8), 933–947

- ^ a b Greenberg, D.L. (2004). President Bush’s false «flashbulb» memory of 9/11/01. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 18, 363–370

- ^ Laney, C., & Loftus, E.F. (2010). Truth in emotional memories. In B.H. Bornstein (Ed.), Emotion and the Law (pp. 157–183). Leicester: Springer Science + Business Media

- ^ a b c Wade, K.A., & Garry, M. (2005). Strategies for verifying false autobiographical memories. American Journal of Psychology, 118(4), 587–602

- ^ Mojet J, Ko¨ster EP. Sensory memory and food texture. Food Qual Prefer 2005; 16: 251–266. doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2004.04.017.

- ^ a b Dell, G.S. (1986). A spreading-activation theory of retrieval in sentence production. Psychological Review, 93(3), 283–321

- ^ Anderson, J.R. (1983). A spreading activation theory of memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 22, 261–295

- ^ a b Kapatsinski, V. (2004). Frequency, age-of-acquisition, lexicon size, neighborhood density, and speed of processing: towards a domain-general, single mechanism account. High Desert Linguistic Society Conference, 6, 131–150.

- ^ a b Forster, K.I. (1991). The density constraint on form-priming in the naming task: Interference effects from a masked prime. Journal of Memory and Language, 30(1), 1–25.

- ^ a b c Jaimes, A., Omura, K., Nagamine, T., & Hirata, K. (2004). Memory cues for meeting video retrieval. In

Proceedings of the 1st ACM Workshop on Continuous Archival and Retrieval of Personal Experiences

(CARPE) at the ACM International Multimedia Conference - ^ Tulving, E., & Thomson, D.M. (1973). Encoding specificity and retrieval processes in episodic memory. Psychological Review, 80(5), 352–373

- ^ Smith, S.M. (1984). A comparison of two techniques for reducing context-dependent forgetting. Memory and Cognition, 12(5), 477–482.

- ^ Eich, J.E. (1980). The cue-dependent nature of state-dependent retrieval. Memory and Cognition, 8(2), 157–173.

- ^ Thomson, D.M., & Tulving, E. (1970). Associative encoding and retrieval: Weak and strong cues. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 86(2), 255–262.

- ^ a b Moscovitc, M., & Craik, F.I.M. (1976). Depth of processing, retrieval cues, and uniqueness of encoding as factors in recall. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 15, 447–458.

- ^ Baddeley, A.D., & Dale, H.C.A. (1966). The effect of semantic similarity on retro-active interference in long- and short-term memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 5, 417–420.

- ^ Badre, D. & Wagner, A.D. (2005). Frontal lobe mechanisms that resolve proactive interference. Cerebral Cortex, 15, 2003–2012.

- ^ Dewar, M.T., Cowan, N., & Della Sala, S. (2007). Forgetting due to retroactive interference: A fusion of Muller and Pilzecker’s (1900) early insights into everyday forgetting and recent research on anterograde amnesia. Cortex, 43(5), 616–634.

- ^ Conway, M. A., & Tacchi, P. C. (1996). Motivated confabulation. Neurocase, 2, 325–338

- ^ Treves, A. & Rolls, E. T. (1994). Computational analysis of the role of the hippocampus in memory. Neuroscience, 4(3), 374–391

- ^ Kensinger, E.A., & Corkin, S. (2004). The effects of emotional content and aging on false memories. Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioural Neuroscience, 4(1), 1–9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Schacter, D.L., Koutstaal, W., & Norman, K.A. (1997). False memories and aging. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 1(6).

- ^ Kensinger, E.A. (2009). Remembering the details: Effects of emotion. Emotion Review, 1(2), 99–113

- ^ Dolcos, F., & Denkova, E. (2008). Neural correlates of encoding emotional memories: A review of functional neuroimaging evidence. Cell Science, 5(2)

- ^ Schmidt, S.R. (2004). Autobiographical memories for the September 11 attacks: Reconstructive errors and emotional impairment of memory. Memory and Cognition, 32(3), 443–454

- ^ Ruci, L., Tomes, J.L., & Zelenski, J.M. (2009). Mood-congruent false memories in the DRM paradigm. Cognition and Emotion, 23(6), 1153–1165

- ^ Baddeley, A.D., Bressi, S., Della Sala, S., Logie, R., & Spinnler, H. (1991). The decline of working memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain, 114, 2521–2542.

- ^ Mimura, M., & Komatsu, S.I. (2010). Factors of error and effort in memory intervention for patients with Alzheimer’s disease and amnesic syndrome. Psychogeriatrics, 10, 179–186.

- ^ a b Mitchell, J.P., Sullivan, A.L., Schacter, D.L., & Budson, A.E. (2006). Misattribution errors in Alzheimer’s disease: The illusory truth effect. Neuropsychology, 20(2), 185–192.

- ^ Hildebrandt, H., Haldenwanger, A., & Eling, P. (2009). False recognition helps to distinguish patients with Alzheimer’s disease and amnesic mci from patients with other kinds of dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 28(2).

- ^ a b Kramer, J.H., Delis, D.C., Blusewicz, M.J., & Brandt, J. (1988). Verbal memory errors in Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s dementias. Developmental Neuropsychology, 4(1), 1–15.

- ^ Kern, B.S., Gorp, W.G.V., Cummings, J.L., Brown, W.S., & Osato, S.S. (1992). Confabulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain and Cognition, 19(2), 172–182.

- ^ Fuld, P.A., Katzman, R., Davies, P., & Terry, R.D. (2004). Intrusions as a sign of Alzheimer dementia chemical and pathological verification. Annals of Neurology, 11(2), 155–159.

- ^ a b c d e Ilsley, J.E., Moffoot, A.P.R., & O’Carroll, R.E. (1995). An analysis of memory dysfunction in major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 35, 1–9.

- ^ a b c d Fridberg, D.J., Brenner, A., & Lysaker, P.H. (2010). Verbal memory intrusions in schizophrenia: Associations with self-reflectivity, symptomatology, and neurocognition. Psychiatry Research, 179, 6–11.

- ^ Brébion, G., Amador, X., Smith, M.J., Malaspina, D., Sharif, Z. & Gorman, J.M. (1999). Opposite links of positive and negative symptomatology with memory errors in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research, 88, 15–24.

- ^ a b c Mammarella, N., Altamura M., Padalino F.A., Petito A., Fairfield B. & Bellomo A. (2010). False memories in schizophrenia? An imagination inflation study. Psychiatry Research, 179, 267–273.

- ^ a b c Whitehouse, W.G., Orne, E.C., Dinges, D.F. (2010). Extreme cognitive interviewing: A blueprint for false memories through imagination inflation. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 58(3), 269–287

- ^ a b c English, S.M., Nielson, K.A. (2010). Reduction of the misinformation effect by arousal induced after learning. Cognition, 117(2), 237–242.

- ^ a b Loftus, E.F., Loftus, G.R., Messo, J. (1987). Some fact about “weapon focus”. Law and Human Behavior, 11(1), 55–62.

- ^ a b c d Mitchell, K.J., Livosky, M., Mather, M. (1998). The weapon focus effect revisited: The role of novelty. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 3, 287–303

- ^ Moreland, R.L., Zajonc, R.B. (1982). Exposure effects in person perception: Familiarity, similarity, and attraction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 18(5), 395–415

- ^ Lindsay, D.S., & Read, J.D. (1994). Psychotherapy and memories of childhood sexual abuse: A cognitive perspective. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 8, 281–338.

- ^ Hyman Jr., I.E., & Pentland, J. (1996). The role of mental imagery in the creation of false childhood memories. Journal of Memory and Language, 35, 101–117.

- ^ Lindsay, D.S., & Read, J.D. (1995). Memory work and recovered memories of childhood sexual abuse: Scientific evidence and public, professional, and personal issues. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 1(4), 846–908

Memory gaps and errors refer to the incorrect recall, or complete loss, of information in the memory system for a specific detail and/or event. Memory errors may include remembering events that never occurred, or remembering them differently from the way they actually happened.[1] These errors or gaps can occur due to a number of different reasons, including the emotional involvement in the situation, expectations and environmental changes. As the retention interval between encoding and retrieval of the memory lengthens, there is an increase in both the amount that is forgotten, and the likelihood of a memory error occurring.

Overview[edit]

There are several different types of memory errors, in which people may inaccurately recall details of events that did not occur, or they may simply misattribute the source of a memory. In other instances, imagination of a certain event can create confidence that such an event actually occurred. Causes of such memory errors may be due to certain cognitive factors, such as spreading activation, or to physiological factors, including brain damage, age or emotional factors. Furthermore, memory errors have been reported in individuals with schizophrenia and depression. The consequences of memory errors can have significant implications. Two main areas of concern regarding memory errors are in eyewitness testimony and cases of child abuse.

Types of memory errors[edit]

Blocking[edit]

The feeling that a person gets when they know the information, but can not remember a specific detail, like an individual’s name or the name of a place is described as the «tip-of-the-tongue» experience. The tip-of-the-tongue experience is a classic example of blocking, which is a failure to retrieve information that is available in memory even though you are trying to produce it.[2] The information you are trying to remember has been encoded and stored, and a cue is available that would usually trigger its recollection.[2] The information has not faded from memory and a person is not forgetting to retrieve the information.[2] What a person is experiencing is a complete retrieval failure, which makes blocking especially frustrating.[2] Blocking occurs especially often for the names of people and places, because their links to related concepts and knowledge are weaker than for common names.[2] The experience of blocking occurs more often as we get older; this «tip of the tongue» experience is a common complaint amongst 60- and 70-year-olds.[2]

Transience[edit]

Transience refers to forgetting what occurs with the passage of time.[3] Transience occurs during the storage phase of memory, after an experience has been encoded and before it is retrieved.[3] As time passes, the quality of our memory also changes, deteriorating from specific to more general.[3] German philosopher named Hermann Ebbinghaus decided to measure his own memory for lists of nonsense syllables at various times after studying them. He decided to draw out a curve of his forgetting pattern over time. He realized that there is a rapid drop-off in retention during the first tests and there is a slower rate of forgetting later on.[3] Therefore, transience denotes the gradual change of a specific knowledge or idea into more general memories.[4]

Absentmindedness[edit]

Absentmindedness is a gap in attention which causes memory failure. In this situation the information does not disappear from memory, it can later be recalled. But the lack of attention at a specific moment prevents the information from being recalled at that specific moment. A common cause of absentmindedness is a lack of attention.[clarification needed] Attention is vital to encoding information in long-term memory. Without proper attention, material is much less likely to be stored properly and recalled later.[5] When attention is divided, less activity in the lower left frontal lobe diminishes the ability for elaborative memory encoding to take place, and results in absentminded forgetting. More recent research has shown that divided attention also leads to less hippocampal involvement in encoding.[5] A common example of absentmindedness is not remembering to carry out actions that had been planned to be done in the future, for example, picking up grocery items, and remembering times of meetings.[6]

False memories[edit]

False memories, sometimes referred to as confabulation, refer to the recollection of inaccurate details of an event, or recollection of a whole event that never occurred. Studies investigating this memory error have been able to successfully implant memories among participants that never existed, such as being lost in a mall as a child (termed the lost in the mall technique) or spilling a bowl of punch at a wedding reception.[7] In this case, false memories were implanted among participants by their family members who claimed that the event had happened. This evidence demonstrates the possibility of implanting false memories on individuals by leading them to remember such events that never occurred. This memory error can be particularly worrisome in judicial settings, in which witnesses may have false recollections of a crime after it has happened, especially when told by others that particular things may have happened which did not.[8] Another area of concern regarding false memories is in cases of child abuse.

Problem of bias[edit]

The problem of bias, which is the distorting influences of present knowledge, beliefs, and feelings on recollection of previous experiences.[9] Sometimes what people remember from their past says less about what actually happened than about what they personally believe, feel, and the knowledge they have acquired at the present time.[9] An individual’s current moods can bias their memory recall, researchers have found.[9] There are three types of memory biases, consistency bias, change bias and egocentric bias.[9] Consistency bias is the bias to reconstruct the past to fit the present.[9] Change bias is the tendency to exaggerate differences between what we feel or believe in the present and what we previously felt or believed in the past.[9] Egocentric bias is a form of change bias, the tendency to exaggerate the change between the past and the present in order to make ourselves look good in any given situation.[9]

Misinformation effect[edit]

The misinformation effect refers to the change in memory due to the presentation of information that is relevant to the target memory, such as leading questions or suggestions.[10] Memories are likely to be altered when questions are worded differently or when inaccurate information is presented. For example, in one experiment participants watched a video of an automobile accident and were then asked questions regarding the accident. When asked how fast the automobiles were driving when they smashed into each other, the speed estimate was higher than when asked how fast the automobiles were driving when they hit, bumped or collided into each other. Similarly, participants were more likely to report there being shattered glass present when the word smashed was used instead of other verbs.[11] Evidently, memory recollection can be altered with misleading information after the event.

Source confusion[edit]

Source confusion or unconscious transference,[12] involves the misattribution of the source of a memory. For instance, an individual may recall seeing an event in person when in reality they only witnessed the event on television.[12] Ultimately, the individual has an inability to remember the source of information in which the content and the source become dissociated. This may be more likely for more distant memories, such as childhood memories.[7] In more severe cases of source confusion, you can take fictional stories you heard from when you were younger and assimilated these stories being your childhood. For example, say your father told you stories about his life when he was a child every night before you went to sleep when you were a child. When you grow up, you might mistakenly remember these stories your dad told you as your own and integrate them into your childhood memories.[13]

Imagination inflation[edit]

Imagination inflation refers to when a person remembers details of a memory that are exaggerated versions of the actual event or remember an entire memory that never occurred due to the act of imagination.[14] That is, when one imagines an event occurring, their confidence that this event actually did occur increases. One reason for this may be due to the act of imagination increasing the familiarity of the event. When the event seems more familiar, it may become more likely for people to report it actually occurring. For instance, in an experiment participants were asked to imagine playing inside and then running outside toward a window, falling and breaking it, while other participants did not imagine anything. Participants who had imagined this scenario reported an increased level of confidence that the event had actually happened in comparison to those who did not imagine the event.[7] This error can be caused simply by imagining an event.

Deese–Roediger–McDermott (DRM) paradigm[edit]

Deese-Roediger-McDermott paradigm refers to the incorrect recall of features of an event that were not actually present, due to the features being related to a common theme.[15] This paradigm has been demonstrated with the use of word lists and subsequent recognition tests. For example, experiments have shown that if a research participant is presented with the words: bed rest awake tired dream wake snooze snore nap yawn drowsy, there is a high likelihood that the participant will falsely recall that the word sleep was in the list of words. These results show a significant illusion in memory, in which people remember items that were never presented simply due to their relation with other items in a common theme.[1]

Schematic errors[edit]

Schematic errors refer to the use of a schema to help reconstruct parts of an experience that cannot be remembered. This may include parts of the schema that did not actually take place, or aspects of a schema that are stereotypical of an event.[16] Schemas can be described as mental guidelines (scripts) for events that are encountered in daily life.[16] For example, when going to the gas station, there is a general pattern of how things will occur (i.e. turn car off, get out of car, open gas tank, punch the gas button, put nozzle into the tank, fill up the tank, put the nozzle back, close the tank, pay, turn car on, leave). Schemas make the world more predictable, allowing expectations to be formed of how things will enfold and to take note of things that happen out of context.[16] However, schemas also allow for memory errors, in that if certain aspects of a scene or event are missing from memory, people may incorrectly remember having actually seen or experienced them because they are usually a regular aspect of the schema. For example, an individual may not remember paying the waiter, but may believe they have done so, as this is a regular step in the script of going to a restaurant. Similarly, a person may recall seeing a fridge in a picture of a kitchen, even if one was not actually depicted due to existing schemas which suggest that kitchens almost always contain a fridge.[16]

Intrusion errors[edit]

Intrusion errors refer to when information that is related to the theme of a certain memory, but was not actually a part of the original episode, become associated with the event.[17] This makes it difficult to distinguish which elements are in fact part of the original memory. One idea regarding how intrusion errors work is due to a lack of recall inhibition, which allows irrelevant information to be brought to awareness while attempting to remember.[18] Another possible explanation is that intrusion errors result from a lack of new context integration into a viable memory trace, or into an already existing memory trace that is related to the appropriate memory.[18] More explanations involve the temporal aspect of recall, meaning that as the time difference between the study periods of different lists approaches zero, the amount of intrusions between the lists tends to increase,[19] the semantic aspect, meaning that the list of target words may have induced a false recall of non-target words that happen to have a similar or same meaning as the targets,[20] and the similarity aspect, for example subjects who were given list of letters to recall were likely to replace target vowels with non-target vowels.[21]

Intrusion errors can be divided into two categories. The first are known as extra-list errors, which occur when incorrect and non-related items are recalled, and were not part of the word study list.[18] These types of intrusion errors often follow the DRM Paradigm effects, in which the incorrectly recalled items are often thematically related to the study list one is attempting to recall from. Another pattern for extra-list intrusions would be an acoustic similarity pattern, this pattern states that targets that have a similar sound to non-targets may be replaced with those non-targets in recall.[22] One major type of extra-list intrusions is called the «Prior-List Intrusion» (PLI), a PLI occurs when targets from previously studied lists are recalled instead of the targets in the current list. PLIs often follow under the temporal aspect of intrusions in that since they were recalled recently they have a high chance of being recalled now.[19] The second type of intrusion error is known as intra-list errors, which is similar to extra-list errors, except it refers to irrelevant recall for items that were on the word study list.[18] Although these two categories of intrusion errors are based on word list studies in laboratories, the concepts can be extrapolated to real-life situations. Also, the same three factors that play a critical role in correct recall (recency, temporal association and semantic relatedness) play a role in intrusions as well.[19]

Time-slice errors[edit]

Time-slice errors occur when a correct event is in fact recalled; however the event that was asked to be recalled is not the one that is recalled. In other words, the timing of events is incorrectly remembered.[23] As discovered in a study by Brewer (1988), often the event or event details that are recalled occurred within a short time proximity to the memory required to be recalled.[23] There are three possible theories as to why time-slice errors occur. First, they may be a form of interference, in which the memory information from one time impairs the recall of information from a different time.[24] (see interference below). A second theory is that intrusion errors may be responsible, in that memories revolving around a similar time period thus share a common theme, and memories of various points of time within that larger time period become mixed with each other and intrude on each other’s recall. Last, the recall of memories often have holes due to forgotten details. Thus, individuals may be using a script (see schema errors) to help fill in these holes with general knowledge of what they know happened around this time. Since scripts are a time-based knowledge structure, which puts details of a memory in sequence to make it easier to understand, time-slice errors can occur if a detail is mistakenly placed in the wrong sequence.[24]

Personal life effects[edit]

Personal life effects refer to the recall and belief in events as declared by family members or friends for having actually happened.[25] Personal life effects are largely based on suggestive influences from external sources, such as family members or a therapist.[7] Other influential sources may include media or literature stories which involve details that are believed to have been experienced or witnessed, such as a natural disaster close to where one resides, or a situation that is common and could have occurred, such as getting lost as a child. Personal life effects are most powerful when claimed to be true by a family member, and even more powerful when a secondary source confirms the event having happened.[7]

Personal life effects are believed to be a form of source confusion, in which the individual cannot recall where the memory is coming from.[26] Therefore, without being able to confirm the source of the memory, the individual may accept the false memory as true. Three factors may be responsible for the implantation of false autobiographical memories. The first factor is time. As time passes, memories fade. Therefore, source confusion may result due to time delay.[7] The second factor is the imagination inflation effect. As the amount of imagination increases, so does one’s familiarity for the contents of the imagination. Thus, source confusion may also occur due to the individual confusing the source of the memory for being true, when in fact it was imaginary.[26] Lastly, social pressure to recall the memory may affect the individual’s belief in the false memory. For example, with increase in pressure, the individual may lower their criteria for validating a memory, and come to accept a false memory for being true.[26] Personal life effects can be extremely crucial to recognize in cases of recovered memories, especially those of abuse, in which the individual may have been led to believe they had been abused as a child by a therapist during psychological therapy, when in fact they had not been. Personal life effects can also be important in witness testimonies, in which suggestions from authorities may incorrectly implant memories regarding witnesses a particular detail about a crime (see the Childhood Abuse and Eye Witness Testimony sections below).

Memory error relating to food[edit]