You’re way off track here. Silencing errors is almost never a good idea, and manually checking $? explicitly after every single command is enormously cumbersome and easy to forget to do (error prone). Don’t set yourself up to easily make a mistake. If you’re getting lots and lots of red, that means your script kept going when it should have stopped instead. It can no longer do useful work if most of its commands are failing. Continuing a program when it and the system are in an unknown state will have unknown consequences; you could easily leave the system in a corrupt state.

The correct solution is to stop the algorithm on the first error. This principle is called «fail fast,» and PowerShell has a built in mechanism to enable that behavior. It is a setting called the error preference, and setting it to the highest level will make your script (and the child scopes if they don’t override it) behave this way:

$ErrorActionPreference = 'Stop'

This will produce a nice, big error message for your consumption and prevent the following commands from executing the first time something goes wrong, without having to check $? every single time you run a command. This makes the code vastly simpler and more reliable. I put it at the top of every single script I ever write, and you almost certainly should as well.

In the rare cases where you can be absolutely certain that allowing the script to continue makes sense, you can use one of two mechanisms:

catch: This is the better and more flexible mechanism. You can wrap atry/catchblock around multiple commands, allowing the first error to stop the sequence and jump into the handler where you can log it and then otherwise recover from it or rethrow it to bubble the error up even further. You can also limit thecatchto specific errors, meaning that it will only be invoked in specific situations you anticipated rather than any error. (For example, failing to create a file because it already exists warrants a different response than a security failure.)- The common

-ErrorActionparameter: This parameter changes the error handling for one single function call, but you cannot limit it to specific types of errors. You should only use this if you can be certain that the script can continue on any error, not just the ones you can anticipate.

In your case, you probably want one big try/catch block around your entire program. Then your process will stop on the first error and the catch block can log it before exiting. This will remove a lot of duplicate code from your program in addition to cleaning up your log file and terminal output and making your program less likely to cause problems.

Do note that this doesn’t handle the case when external executables fail (exit code nonzero, conventionally), so you do still need to check $LASTEXITCODE if you invoke any. Despite this limitation, the setting still saves a lot of code and effort.

Additional reliability

You might also want to consider using strict mode:

Set-StrictMode -Version Latest

This prevents PowerShell from silently proceeding when you use a non-existent variable and in other weird situations. (See the -Version parameter for details about what it restricts.)

Combining these two settings makes PowerShell much more of fail-fast language, which makes programming in it vastly easier.

- Remove From My Forums

-

Question

-

Get-AdUser -Filter {Enabled -eq $False} | Foreach { Disable-CSUser -identity $_.UserPrincipalName}

How should i write it if i want -ErrorAction ‘silentlycontinue, so i dont get any error messages from users that do not exist in Skype for Business?

All replies

-

Hi Alexander,

you can do this by appending that very parameter to Disable-CSUser:

Get-AdUser -Filter {Enabled -eq $False} | Foreach { Disable-CSUser -identity $_.UserPrincipalName -ErrorAction SilentlyContinue }Please note though, that setting this will cause the script to ignore all

errors. So if it fails for other reasons, you won’t know.For more detailed error-handling, use try/catch statements.

Cheers,

Fred

There’s no place like 127.0.0.1

-

Hopefully when i advance my PowerShell skills, i could write soemthing that only tries to disable a Lync user thats match a AD user.

I still get a error after doing as you sugested:

-

Hi Alexander,

ok, this appears to be somewhat lousy programming, if it doesn’t respect erroraction flags. But nothing we can’t work around (this’ll be a bit more elaborate) …

$Begin = { $tempnote = $global:ErrorActionPreference $global:ErrorActionPreference = 'Stop' } $Process = { try { Disable-CSUser -identity $_.UserPrincipalName } catch { } } $End = { $global:ErrorActionPreference = $tempnote } Get-AdUser -Filter { Enabled -eq $False } | ForEach-Object -Begin $Begin -Process $Process -End $EndNow what the hell is happening here?

Well, ErrorActionPreference is a way to set globally, how cmdlets handle errors (unless they override it with the -ErrorAction parameter). By changing this variable on a global scale, we can often reach poorly written cmdlet that do not respect the the -ErrorAction

parameter.By setting this in the Begin and End blocks, it is only set once when the scriptblock is first run and once after the last item passed through it.

By forcing it to stop this way, each error should trigger the try statement and be caught by the catch statement (which does nothing and thus the error is ignored).

Hope that works better for you.

Cheers,

Fred

There’s no place like 127.0.0.1

-

Edited by

Monday, September 21, 2015 11:25 AM

-

Edited by

-

Still an error:

ForEach-Object : The script block cannot be invoked because it contains more than one clause. The Invoke() method can only be used on scrip

t blocks that contain a single clause.

At line:1 char:45

+ Get-AdUser -Filter { Enabled -eq $False } | ForEach-Object {

+ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

+ CategoryInfo : InvalidOperation: (:) [ForEach-Object], PSInvalidOperationException

+ FullyQualifiedErrorId : InvalidOperation,Microsoft.PowerShell.Commands.ForEachObjectCommandBut dont bother, it was just me trying to create a one liner. Just wanted it to look nicer.

Thanks anymway

-

Hi Alexander,

you’re right, sorry, I messed up a little. I fixed it in the previous post — see if that works better for you (it sure runs for me, but I don’t have

Disable-CSUser available here).Cheers,

Fred

There’s no place like 127.0.0.1

-

Hi Alexander,

I think, it’s not always the best solution to simply hide errors. PowerShell has a nice error handling with try/catch. With the following code, you don’t get the error message AND you get a list of users that generated errors:

$Users = Get-AdUser -Filter {Enabled -eq $False} $errorUsers = @() Foreach($User in $Users) { try{ Disable-CSUser -identity $User.UserPrincipalName } catch{ $errorUsers += $User } }Best wishes

Christoph

-

Proposed as answer by

hpotsirhc

Thursday, March 10, 2016 7:44 AM

-

Proposed as answer by

- Introduction to Error Action in PowerShell

- Use the

-ErrorActionParameter in PowerShell - Setting Error Action Preferences in PowerShell

Whether we want to ignore error messages or terminate a script’s execution when an error occurs, Windows PowerShell has plenty of options for dealing with errors. This article will discuss multiple techniques in handling and suppressing errors.

Introduction to Error Action in PowerShell

Even though it is effortless to suppress Windows PowerShell errors, doing so isn’t always the best option (although it can be). If we carelessly tell PowerShell to hide errors, it can cause our script to behave unpredictably.

Suppressing error messages also makes troubleshooting and information gathering a lot more complicated. So tread lightly and be careful about using the following snippets that you will see in this article.

Use the -ErrorAction Parameter in PowerShell

The most common method for dealing with errors is to append the -ErrorAction parameter switch to a cmdlet. The -ErrorAction parameter switch lets PowerShell tell what to do if the cmdlet produces an error.

Command:

Get-Service 'svc_not_existing' -ErrorAction SilentlyContinue

In the command above, we are querying for a service that doesn’t exist. Usually, PowerShell will throw an error if the service doesn’t exist.

Since we use the -ErrorAction parameter, the script will continue as expected, like it doesn’t have an error.

Setting Error Action Preferences in PowerShell

If we need a script to behave in a certain way (such as suppressing errors), we might consider setting up some preference variables. Preference variables act as configuration settings for PowerShell.

We might use a preference variable to control the number of history items that PowerShell retains or force PowerShell to ask the user before performing specific actions.

For example, here is how you can use a preference variable to set the -ErrorAction parameter to SilentlyContinue for the entire session.

Command:

$ErrorActionPreference = 'SilentlyContinue'

There are many other error actions that we can specify for the ErrorAction switch parameter.

Continue: PowerShell will display the error message, but the script will continue to run.Ignore: PowerShell does not produce any error message, writes any error output on the host, and continues execution.Stop: PowerShell will display the error message and stop running the script.Inquire: PowerShell displays the error message but will ask for confirmation first if the user wants to continue.SilentlyContinue: PowerShell silently continues with code execution if the code does not work or has non-terminating errors.Suspend: PowerShell suspends the workflow of the script.

As previously mentioned, the -ErrorAction switch has to be used in conjunction with a PowerShell cmdlet. For instance, we used the Get-Process cmdlet to demonstrate how the ErrorAction switch works.

Powershell ErrorAction это ключ, с помощью которого мы можем обходить часть ошибок. Это помогает остановить скрипт, если будет ошибка.

У меня есть две директории, одна которая существует, а другая нет. Если я выполню поиск файлов, то скрипт выведет ошибку:

$path = 'C:NotExist','C:Exist'

$path | Get-ChildItemGet-ChildItem : Cannot find path ‘C:NotExist’ because it does not exist.

Что бы этого избежать у нас есть ключ ErrorAction со следующими значениями:

- Continue или 0 — значение по умолчанию. Ошибка выводится на экран, но работа скрипта продолжается.

- SilentlyContinue или 1 — ошибка не выводится на экран и скрипт продолжает работу.

- Stop или 2 — останавливает выполнение при ошибке.

- Ignore или 3 — игнорирует ошибки и при этом никакие логи об ошибке не сохраняются.

- Inquire — с этим ключом у нас будет запрос на дальнейшее действия.

- Suspend — работает при режиме Workflow (рабочих процессов). К обычным командлетам не имеет отношения.

Пример со значением по умолчанию:

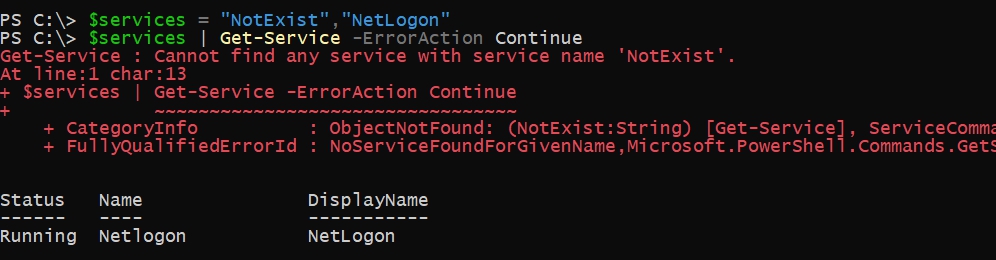

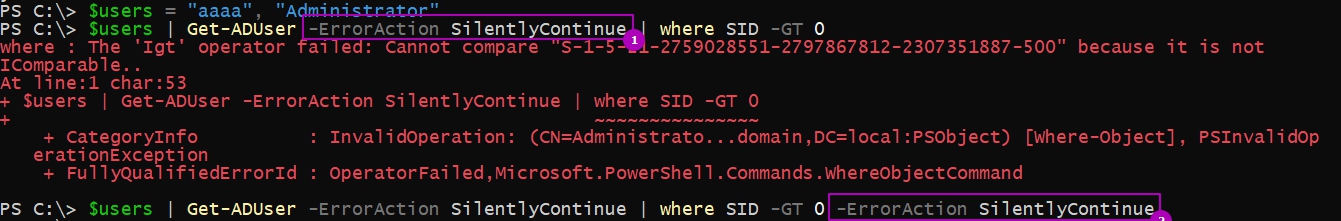

$services = "NotExist","NetLogon"

$services | Get-Service -ErrorAction ContinueВ случае с SilentContinue у нас ошибок не будет:

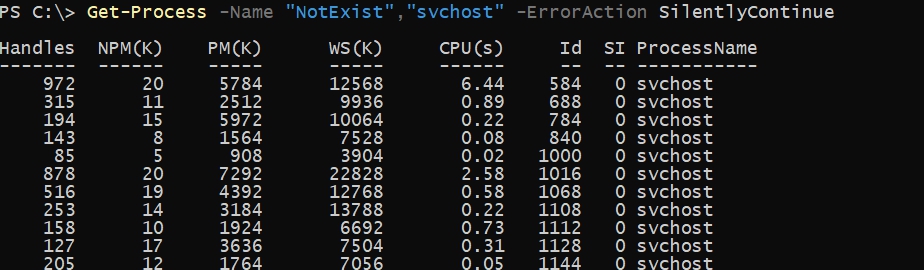

Get-Process -Name "NotExist","svchost" -ErrorAction SilentlyContinueПри этом, конечно, ключ мы должны указывать везде где ожидаем увидеть ошибку:

Если мы выполним такую команду, то все равно получим ошибку, которая остановит процесс:

Get-Variable -Name $null -ErrorAction SilentlyContinueЭто ошибка, которая прерывает процесс и для нее нужно использовать другие методы в виде try и catch.

…

Теги:

#powershell

Q. How can I suppress an error message in PowerShell?

A. To look at other examples on the Internet, you’d think putting this at the top of your script would be the answer:

$ErrorActionPreference = "SilentlyContinue"

Don’t do that. Sure, it’ll suppress errors in your script—ALL of the errors, even helpful ones about syntax errors and so on. Instead, if you anticipate a cmdlet causing an error such as «file not found» or «could not connect» and you don’t want to see the error or deal with it, use the -ErrorAction (or -EA) parameter of that cmdlet:

Get-WmiObject Win32_BIOS -computername localhost,not-online -EA SilentlyContinue

All cmdlets have an -EA parameter. It’s part of the <CommonParameters> listed in every cmdlet’s help.

Do you have a Windows PowerShell question? Find more PowerShell FAQs, articles, and other resources at windowsitpro.com/go/DonJonesPowerShell.

Controlling Error Reporting Behavior and Intercepting Errors

This section briefly demonstrates how to use each of PowerShell’s statements, variables and parameters that are related to the reporting or handling of errors.

The $Error Variable

$Error is an automatic global variable in PowerShell which always contains an ArrayList of zero or more ErrorRecord objects. As new errors occur, they are added to the beginning of this list, so you can always get information about the most recent error by looking at $Error[0]. Both Terminating and Non-Terminating errors will be contained in this list.

Aside from accessing the objects in the list with array syntax, there are two other common tasks that are performed with the $Error variable: you can check how many errors are currently in the list by checking the $Error.Count property, and you can remove all errors from the list with the $Error.Clear() method. For example:

Figure 2.1: Using $Error to access error information, check the count, and clear the list.

If you’re planning to make use of the $Error variable in your scripts, keep in mind that it may already contain information about errors that happened in the current PowerShell session before your script was even started. Also, some people consider it a bad practice to clear the $Error variable inside a script; since it’s a variable global to the PowerShell session, the person that called your script might want to review the contents of $Error after it completes.

ErrorVariable

The ErrorVariable common parameter provides you with an alternative to using the built-in $Error collection. Unlike $Error, your ErrorVariable will only contain errors that occurred from the command you’re calling, instead of potentially having errors from elsewhere in the current PowerShell session. This also avoids having to clear the $Error list (and the breach of etiquette that entails.)

When using ErrorVariable, if you want to append to the error variable instead of overwriting it, place a + sign in front of the variable’s name. Note that you do not use a dollar sign when you pass a variable name to the ErrorVariable parameter, but you do use the dollar sign later when you check its value.

The variable assigned to the ErrorVariable parameter will never be null; if no errors occurred, it will contain an ArrayList object with a Count of 0, as seen in figure 2.2:

Figure 2.2: Demonstrating the use of the ErrorVariable parameter.

$MaximumErrorCount

By default, the $Error variable can only contain a maximum of 256 errors before it starts to lose the oldest ones on the list. You can adjust this behavior by modifying the $MaximumErrorCount variable.

ErrorAction and $ErrorActionPreference

There are several ways you can control PowerShell’s handling / reporting behavior. The ones you will probably use most often are the ErrorAction common parameter and the $ErrorActionPreference variable.

The ErrorAction parameter can be passed to any Cmdlet or Advanced Function, and can have one of the following values: Continue (the default), SilentlyContinue, Stop, Inquire, Ignore (only in PowerShell 3.0 or later), and Suspend (only for workflows; will not be discussed further here.) It affects how the Cmdlet behaves when it produces a non-terminating error.

- The default value of Continue causes the error to be written to the Error stream and added to the $Error variable, and then the Cmdlet continues processing.

- A value of SilentlyContinue only adds the error to the $Error variable; it does not write the error to the Error stream (so it will not be displayed at the console).

- A value of Ignore both suppresses the error message and does not add it to the $Error variable. This option was added with PowerShell 3.0.

- A value of Stop causes non-terminating errors to be treated as terminating errors instead, immediately halting the Cmdlet’s execution. This also enables you to intercept those errors in a Try/Catch or Trap statement, as described later in this section.

- A value of Inquire causes PowerShell to ask the user whether the script should continue or not when an error occurs.

The $ErrorActionPreference variable can be used just like the ErrorAction parameter, with a couple of exceptions: you cannot set $ErrorActionPreference to either Ignore or Suspend. Also, $ErrorActionPreference affects your current scope in addition to any child commands you call; this subtle difference has the effect of allowing you to control the behavior of errors that are produced by .NET methods, or other causes such as PowerShell encountering a «command not found» error.

Figure 2.3 demonstrates the effects of the three most commonly used $ErrorActionPreference settings.

Figure 2.3: Behavior of $ErrorActionPreference

Try/Catch/Finally

The Try/Catch/Finally statements, added in PowerShell 2.0, are the preferred way of handling terminating errors. They cannot be used to handle non-terminating errors, unless you force those errors to become terminating errors with ErrorAction or $ErrorActionPreference set to Stop.

To use Try/Catch/Finally, you start with the «Try» keyword followed by a single PowerShell script block. Following the Try block can be any number of Catch blocks, and either zero or one Finally block. There must be a minimum of either one Catch block or one Finally block; a Try block cannot be used by itself.

The code inside the Try block is executed until it is either complete, or a terminating error occurs. If a terminating error does occur, execution of the code in the Try block stops. PowerShell writes the terminating error to the $Error list, and looks for a matching Catch block (either in the current scope, or in any parent scopes.) If no Catch block exists to handle the error, PowerShell writes the error to the Error stream, the same thing it would have done if the error had occurred outside of a Try block.

Catch blocks can be written to only catch specific types of Exceptions, or to catch all terminating errors. If you do define multiple catch blocks for different exception types, be sure to place the more specific blocks at the top of the list; PowerShell searches catch blocks from top to bottom, and stops as soon as it finds one that is a match.

If a Finally block is included, its code is executed after both the Try and Catch blocks are complete, regardless of whether an error occurred or not. This is primarily intended to perform cleanup of resources (freeing up memory, calling objects’ Close() or Dispose() methods, etc.)

Figure 2.4 demonstrates the use of a Try/Catch/Finally block:

Figure 2.4: Example of using try/catch/finally.

Notice that «Statement after the error» is never displayed, because a terminating error occurred on the previous line. Because the error was based on an IOException, that Catch block was executed, instead of the general «catch-all» block below it. Afterward, the Finally executes and changes the value of $testVariable.

Also notice that while the Catch block specified a type of [System.IO.IOException], the actual exception type was, in this case, [System.IO.DirectoryNotFoundException]. This works because DirectoryNotFoundException is inherited from IOException, the same way all exceptions share the same base type of System.Exception. You can see this in figure 2.5:

Figure 2.5: Showing that IOException is the Base type for DirectoryNotFoundException

Trap

Trap statements were the method of handling terminating errors in PowerShell 1.0. As with Try/Catch/Finally, the Trap statement has no effect on non-terminating errors.

Trap is a bit awkward to use, as it applies to the entire scope where it is defined (and child scopes as well), rather than having the error handling logic kept close to the code that might produce the error the way it is when you use Try/Catch/Finally. For those of you familiar with Visual Basic, Trap is a lot like «On Error Goto». For that reason, Trap statements don’t see a lot of use in modern PowerShell scripts, and I didn’t include them in the test scripts or analysis in Section 3 of this ebook.

For the sake of completeness, here’s an example of how to use Trap:

Figure 2.6: Use of the Trap statement

As you can see, Trap blocks are defined much the same way as Catch blocks, optionally specifying an Exception type. Trap blocks may optionally end with either a Break or Continue statement. If you don’t use either of those, the error is written to the Error stream, and the current script block continues with the next line after the error. If you use Break, as seen in figure 2.5, the error is written to the Error stream, and the rest of the current script block is not executed. If you use Continue, the error is not written to the error stream, and the script block continues execution with the next statement.

The $LASTEXITCODE Variable

When you call an executable program instead of a PowerShell Cmdlet, Script or Function, the $LASTEXITCODE variable automatically contains the process’s exit code. Most processes use the convention of setting an exit code of zero when the code finishes successfully, and non-zero if an error occurred, but this is not guaranteed. It’s up to the developer of the executable to determine what its exit codes mean.

Note that the $LASTEXITCODE variable is only set when you call an executable directly, or via PowerShell’s call operator (&) or the Invoke-Expression cmdlet. If you use another method such as Start-Process or WMI to launch the executable, they have their own ways of communicating the exit code to you, and will not affect the current value of $LASTEXITCODE.

Figure 2.7: Using $LASTEXITCODE.

The $? Variable

The $? variable is a Boolean value that is automatically set after each PowerShell statement or pipeline finishes execution. It should be set to True if the previous command was successful, and False if there was an error.

When the previous command was a PowerShell statement, $? will be set to False if any errors occurred (even if ErrorAction was set to SilentlyContinue or Ignore).

If the previous command was a call to a native exe, $? will be set to False if the $LASTEXITCODE variable does not equal zero. If the $LASTEXITCODE variable equals zero, then in theory $? should be set to True. However, if the native command writes something to the standard error stream then $? could be set to False even if $LASTEXITCODE equals zero. For example, the PowerShell ISE will create and append error objects to $Error for standard error stream output and consequently $? will be False regardless of the value of $LASTEXITCODE. Redirecting the standard error stream into a file will result in a similar behavior even when the PowerShell host is the regular console. So it is probably best to test the behavior in your specific environment if you want to rely on $? being set correctly to True.

Just be aware that the value of this variable is reset after every statement. You must check its value immediately after the command you’re interested in, or it will be overwritten (probably to True). Figure 2.8 demonstrates this behavior. The first time $? is checked, it is set to False, because the Get-Item encountered an error. The second time $? was checked, it was set to True, because the previous command was successful; in this case, the previous command was «$?» from the first time the variable’s value was displayed.

Figure 2.8: Demonstrating behavior of the $? variable.

The $? variable doesn’t give you any details about what error occurred; it’s simply a flag that something went wrong. In the case of calling executable programs, you need to be sure that they return an exit code of 0 to indicate success and non-zero to indicate an error before you can rely on the contents of $?.

Summary

That covers all of the techniques you can use to either control error reporting or intercept and handle errors in a PowerShell script. To summarize:

- To intercept and react to non-terminating errors, you check the contents of either the automatic $Error collection, or the variable you specified as the ErrorVariable. This is done after the command completes; you cannot react to a non-terminating error before the Cmdlet or Function finishes its work.

- To intercept and react to terminating errors, you use either Try/Catch/Finally (preferred), or Trap (old and not used much now.) Both of these constructs allow you to specify different script blocks to react to different types of Exceptions.

- Using the ErrorAction parameter, you can change how PowerShell cmdlets and functions report non-terminating errors. Setting this to Stop causes them to become terminating errors instead, which can be intercepted with Try/Catch/Finally or Trap.

- $ErrorActionPreference works like ErrorAction, except it can also affect PowerShell’s behavior when a terminating error occurs, even if those errors came from a .NET method instead of a cmdlet.

- $LASTEXITCODE contains the exit code of external executables. An exit code of zero usually indicates success, but that’s up to the author of the program.

- $? can tell you whether the previous command was successful, though you have to be careful about using it with external commands. If they don’t follow the convention of using an exit code of zero as an indicator of success or if they write to the standard error stream then the resulting value in $? may not be what you expect. You also need to make sure you check the contents of $? immediately after the command you are interested in.

Note: This tip requires PowerShell 3.0 or above.

PowerShell lets you control how it responds to a non-terminating error (an error that does not stop the cmdlet processing) globally via the $ErrorActionPreference preference variable, or at a cmdlet level using the -ErrorAction parameter. Both ways support the following values:

Stop: Displays the error message and stops executing.

Inquire: Displays the error message and asks you whether you want to continue.

Continue: Displays the error message and continues (Default) executing.

SilentlyContinue: No effect. The error message is not displayed and execution continues without interruption.

No matter which value you choose, the error is written to the host and added to the $error variable. Starting with PowerShell 3.0, at a command level only (e.g ErrorAction), we have an additional value: Ignore. When Ignore is specified, the error is neither displayed not added to $error variable.

# check the error count

PS> $error.Count

0

# use SilentlyContinue to ignore the error

PS> Get-ChildItem NoSuchFile -ErrorAction SilentlyContinue

# error is ignored but is added to the $error variable

PS> $error.Count

1

PS> $error.Clear()

# Using Ignore truly discards the error and the error is not added to $error variable

PS> Get-ChildItem NoSuchFile -ErrorAction Ignore

PS> $error.Count

0

Share on: