Request and response objects¶

Quick overview¶

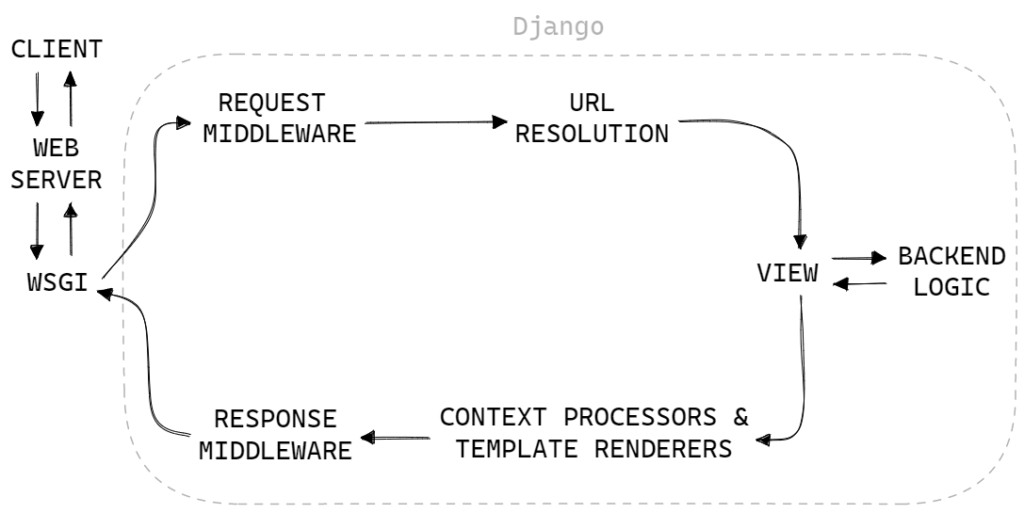

Django uses request and response objects to pass state through the system.

When a page is requested, Django creates an HttpRequest object that

contains metadata about the request. Then Django loads the appropriate view,

passing the HttpRequest as the first argument to the view function.

Each view is responsible for returning an HttpResponse object.

This document explains the APIs for HttpRequest and

HttpResponse objects, which are defined in the django.http

module.

HttpRequest objects¶

-

class

HttpRequest¶

Attributes¶

All attributes should be considered read-only, unless stated otherwise.

-

HttpRequest.scheme¶ -

A string representing the scheme of the request (

httporhttps

usually).

-

HttpRequest.body¶ -

The raw HTTP request body as a bytestring. This is useful for processing

data in different ways than conventional HTML forms: binary images,

XML payload etc. For processing conventional form data, use

HttpRequest.POST.You can also read from an

HttpRequestusing a file-like interface with

HttpRequest.read()orHttpRequest.readline(). Accessing

thebodyattribute after reading the request with either of these I/O

stream methods will produce aRawPostDataException.

-

HttpRequest.path¶ -

A string representing the full path to the requested page, not including

the scheme, domain, or query string.Example:

"/music/bands/the_beatles/"

-

HttpRequest.path_info¶ -

Under some web server configurations, the portion of the URL after the

host name is split up into a script prefix portion and a path info

portion. Thepath_infoattribute always contains the path info portion

of the path, no matter what web server is being used. Using this instead

ofpathcan make your code easier to move between

test and deployment servers.For example, if the

WSGIScriptAliasfor your application is set to

"/minfo", thenpathmight be"/minfo/music/bands/the_beatles/"

andpath_infowould be"/music/bands/the_beatles/".

-

HttpRequest.method¶ -

A string representing the HTTP method used in the request. This is

guaranteed to be uppercase. For example:if request.method == 'GET': do_something() elif request.method == 'POST': do_something_else()

-

HttpRequest.encoding¶ -

A string representing the current encoding used to decode form submission

data (orNone, which means theDEFAULT_CHARSETsetting is

used). You can write to this attribute to change the encoding used when

accessing the form data. Any subsequent attribute accesses (such as reading

fromGETorPOST) will use the newencodingvalue.

Useful if you know the form data is not in theDEFAULT_CHARSET

encoding.

-

HttpRequest.content_type¶ -

A string representing the MIME type of the request, parsed from the

CONTENT_TYPEheader.

-

HttpRequest.content_params¶ -

A dictionary of key/value parameters included in the

CONTENT_TYPE

header.

-

HttpRequest.GET¶ -

A dictionary-like object containing all given HTTP GET parameters. See the

QueryDictdocumentation below.

-

HttpRequest.POST¶ -

A dictionary-like object containing all given HTTP POST parameters,

providing that the request contains form data. See the

QueryDictdocumentation below. If you need to access raw or

non-form data posted in the request, access this through the

HttpRequest.bodyattribute instead.It’s possible that a request can come in via POST with an empty

POST

dictionary – if, say, a form is requested via the POST HTTP method but

does not include form data. Therefore, you shouldn’t useif request.POST

to check for use of the POST method; instead, useif request.method ==(see

"POST"HttpRequest.method).POSTdoes not include file-upload information. SeeFILES.

-

HttpRequest.COOKIES¶ -

A dictionary containing all cookies. Keys and values are strings.

-

HttpRequest.FILES¶ -

A dictionary-like object containing all uploaded files. Each key in

FILESis thenamefrom the<input type="file" name="">. Each

value inFILESis anUploadedFile.See Managing files for more information.

FILESwill only contain data if the request method was POST and the

<form>that posted to the request hadenctype="multipart/form-data".

Otherwise,FILESwill be a blank dictionary-like object.

-

HttpRequest.META¶ -

A dictionary containing all available HTTP headers. Available headers

depend on the client and server, but here are some examples:CONTENT_LENGTH– The length of the request body (as a string).CONTENT_TYPE– The MIME type of the request body.HTTP_ACCEPT– Acceptable content types for the response.HTTP_ACCEPT_ENCODING– Acceptable encodings for the response.HTTP_ACCEPT_LANGUAGE– Acceptable languages for the response.HTTP_HOST– The HTTP Host header sent by the client.HTTP_REFERER– The referring page, if any.HTTP_USER_AGENT– The client’s user-agent string.QUERY_STRING– The query string, as a single (unparsed) string.REMOTE_ADDR– The IP address of the client.REMOTE_HOST– The hostname of the client.REMOTE_USER– The user authenticated by the web server, if any.REQUEST_METHOD– A string such as"GET"or"POST".SERVER_NAME– The hostname of the server.SERVER_PORT– The port of the server (as a string).

With the exception of

CONTENT_LENGTHandCONTENT_TYPE, as given

above, any HTTP headers in the request are converted toMETAkeys by

converting all characters to uppercase, replacing any hyphens with

underscores and adding anHTTP_prefix to the name. So, for example, a

header calledX-Benderwould be mapped to theMETAkey

HTTP_X_BENDER.Note that

runserverstrips all headers with underscores in the

name, so you won’t see them inMETA. This prevents header-spoofing

based on ambiguity between underscores and dashes both being normalizing to

underscores in WSGI environment variables. It matches the behavior of

web servers like Nginx and Apache 2.4+.HttpRequest.headersis a simpler way to access all HTTP-prefixed

headers, plusCONTENT_LENGTHandCONTENT_TYPE.

-

HttpRequest.headers¶ -

A case insensitive, dict-like object that provides access to all

HTTP-prefixed headers (plusContent-LengthandContent-Type) from

the request.The name of each header is stylized with title-casing (e.g.

User-Agent)

when it’s displayed. You can access headers case-insensitively:>>> request.headers {'User-Agent': 'Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_12_6', ...} >>> 'User-Agent' in request.headers True >>> 'user-agent' in request.headers True >>> request.headers['User-Agent'] Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_12_6) >>> request.headers['user-agent'] Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_12_6) >>> request.headers.get('User-Agent') Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_12_6) >>> request.headers.get('user-agent') Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_12_6)

For use in, for example, Django templates, headers can also be looked up

using underscores in place of hyphens:{{ request.headers.user_agent }}

-

HttpRequest.resolver_match¶ -

An instance of

ResolverMatchrepresenting the

resolved URL. This attribute is only set after URL resolving took place,

which means it’s available in all views but not in middleware which are

executed before URL resolving takes place (you can use it in

process_view()though).

Attributes set by application code¶

Django doesn’t set these attributes itself but makes use of them if set by your

application.

-

HttpRequest.current_app¶ -

The

urltemplate tag will use its value as thecurrent_app

argument toreverse().

-

HttpRequest.urlconf¶ -

This will be used as the root URLconf for the current request, overriding

theROOT_URLCONFsetting. See

How Django processes a request for details.urlconfcan be set toNoneto revert any changes made by previous

middleware and return to using theROOT_URLCONF.

-

HttpRequest.exception_reporter_filter¶ -

This will be used instead of

DEFAULT_EXCEPTION_REPORTER_FILTER

for the current request. See Custom error reports for details.

-

HttpRequest.exception_reporter_class¶ -

This will be used instead of

DEFAULT_EXCEPTION_REPORTERfor the

current request. See Custom error reports for details.

Attributes set by middleware¶

Some of the middleware included in Django’s contrib apps set attributes on the

request. If you don’t see the attribute on a request, be sure the appropriate

middleware class is listed in MIDDLEWARE.

-

HttpRequest.session¶ -

From the

SessionMiddleware: A

readable and writable, dictionary-like object that represents the current

session.

-

HttpRequest.site¶ -

From the

CurrentSiteMiddleware:

An instance ofSiteor

RequestSiteas returned by

get_current_site()

representing the current site.

-

HttpRequest.user¶ -

From the

AuthenticationMiddleware:

An instance ofAUTH_USER_MODELrepresenting the currently

logged-in user. If the user isn’t currently logged in,userwill be set

to an instance ofAnonymousUser. You

can tell them apart with

is_authenticated, like so:if request.user.is_authenticated: ... # Do something for logged-in users. else: ... # Do something for anonymous users.

Methods¶

-

HttpRequest.get_host()¶ -

Returns the originating host of the request using information from the

HTTP_X_FORWARDED_HOST(ifUSE_X_FORWARDED_HOSTis enabled)

andHTTP_HOSTheaders, in that order. If they don’t provide a value,

the method uses a combination ofSERVER_NAMEandSERVER_PORTas

detailed in PEP 3333.Example:

"127.0.0.1:8000"Raises

django.core.exceptions.DisallowedHostif the host is not in

ALLOWED_HOSTSor the domain name is invalid according to

RFC 1034/1035.Note

The

get_host()method fails when the host is

behind multiple proxies. One solution is to use middleware to rewrite

the proxy headers, as in the following example:class MultipleProxyMiddleware: FORWARDED_FOR_FIELDS = [ 'HTTP_X_FORWARDED_FOR', 'HTTP_X_FORWARDED_HOST', 'HTTP_X_FORWARDED_SERVER', ] def __init__(self, get_response): self.get_response = get_response def __call__(self, request): """ Rewrites the proxy headers so that only the most recent proxy is used. """ for field in self.FORWARDED_FOR_FIELDS: if field in request.META: if ',' in request.META[field]: parts = request.META[field].split(',') request.META[field] = parts[-1].strip() return self.get_response(request)

This middleware should be positioned before any other middleware that

relies on the value ofget_host()– for instance,

CommonMiddlewareor

CsrfViewMiddleware.

-

HttpRequest.get_port()¶ -

Returns the originating port of the request using information from the

HTTP_X_FORWARDED_PORT(ifUSE_X_FORWARDED_PORTis enabled)

andSERVER_PORTMETAvariables, in that order.

-

HttpRequest.get_full_path()¶ -

Returns the

path, plus an appended query string, if applicable.Example:

"/music/bands/the_beatles/?print=true"

-

HttpRequest.get_full_path_info()¶ -

Like

get_full_path(), but usespath_infoinstead of

path.Example:

"/minfo/music/bands/the_beatles/?print=true"

-

HttpRequest.build_absolute_uri(location=None)¶ -

Returns the absolute URI form of

location. If no location is provided,

the location will be set torequest.get_full_path().If the location is already an absolute URI, it will not be altered.

Otherwise the absolute URI is built using the server variables available in

this request. For example:>>> request.build_absolute_uri() 'https://example.com/music/bands/the_beatles/?print=true' >>> request.build_absolute_uri('/bands/') 'https://example.com/bands/' >>> request.build_absolute_uri('https://example2.com/bands/') 'https://example2.com/bands/'

Note

Mixing HTTP and HTTPS on the same site is discouraged, therefore

build_absolute_uri()will always generate an

absolute URI with the same scheme the current request has. If you need

to redirect users to HTTPS, it’s best to let your web server redirect

all HTTP traffic to HTTPS.

-

HttpRequest.get_signed_cookie(key, default=RAISE_ERROR, salt=», max_age=None)¶ -

Returns a cookie value for a signed cookie, or raises a

django.core.signing.BadSignatureexception if the signature is

no longer valid. If you provide thedefaultargument the exception

will be suppressed and that default value will be returned instead.The optional

saltargument can be used to provide extra protection

against brute force attacks on your secret key. If supplied, the

max_ageargument will be checked against the signed timestamp

attached to the cookie value to ensure the cookie is not older than

max_ageseconds.For example:

>>> request.get_signed_cookie('name') 'Tony' >>> request.get_signed_cookie('name', salt='name-salt') 'Tony' # assuming cookie was set using the same salt >>> request.get_signed_cookie('nonexistent-cookie') ... KeyError: 'nonexistent-cookie' >>> request.get_signed_cookie('nonexistent-cookie', False) False >>> request.get_signed_cookie('cookie-that-was-tampered-with') ... BadSignature: ... >>> request.get_signed_cookie('name', max_age=60) ... SignatureExpired: Signature age 1677.3839159 > 60 seconds >>> request.get_signed_cookie('name', False, max_age=60) False

See cryptographic signing for more information.

-

HttpRequest.is_secure()¶ -

Returns

Trueif the request is secure; that is, if it was made with

HTTPS.

-

HttpRequest.accepts(mime_type)¶ -

Returns

Trueif the requestAcceptheader matches themime_type

argument:>>> request.accepts('text/html') True

Most browsers send

Accept: */*by default, so this would return

Truefor all content types. Setting an explicitAcceptheader in

API requests can be useful for returning a different content type for those

consumers only. See Content negotiation example of using

accepts()to return different content to API consumers.If a response varies depending on the content of the

Acceptheader and

you are using some form of caching like Django’scache middleware, you should decorate the view with

vary_on_headers('Accept')so that the responses are

properly cached.

-

HttpRequest.read(size=None)¶

-

HttpRequest.readline()¶

-

HttpRequest.readlines()¶

-

HttpRequest.__iter__()¶ -

Methods implementing a file-like interface for reading from an

HttpRequestinstance. This makes it possible to consume an incoming

request in a streaming fashion. A common use-case would be to process a

big XML payload with an iterative parser without constructing a whole

XML tree in memory.Given this standard interface, an

HttpRequestinstance can be

passed directly to an XML parser such as

ElementTree:import xml.etree.ElementTree as ET for element in ET.iterparse(request): process(element)

QueryDict objects¶

-

class

QueryDict¶

In an HttpRequest object, the GET and

POST attributes are instances of django.http.QueryDict,

a dictionary-like class customized to deal with multiple values for the same

key. This is necessary because some HTML form elements, notably

<select multiple>, pass multiple values for the same key.

The QueryDicts at request.POST and request.GET will be immutable

when accessed in a normal request/response cycle. To get a mutable version you

need to use QueryDict.copy().

Methods¶

QueryDict implements all the standard dictionary methods because it’s

a subclass of dictionary. Exceptions are outlined here:

-

QueryDict.__init__(query_string=None, mutable=False, encoding=None)¶ -

Instantiates a

QueryDictobject based onquery_string.>>> QueryDict('a=1&a=2&c=3') <QueryDict: {'a': ['1', '2'], 'c': ['3']}>

If

query_stringis not passed in, the resultingQueryDictwill be

empty (it will have no keys or values).Most

QueryDicts you encounter, and in particular those at

request.POSTandrequest.GET, will be immutable. If you are

instantiating one yourself, you can make it mutable by passing

mutable=Trueto its__init__().Strings for setting both keys and values will be converted from

encoding

tostr. Ifencodingis not set, it defaults to

DEFAULT_CHARSET.

-

classmethod

QueryDict.fromkeys(iterable, value=», mutable=False, encoding=None)¶ -

Creates a new

QueryDictwith keys fromiterableand each value

equal tovalue. For example:>>> QueryDict.fromkeys(['a', 'a', 'b'], value='val') <QueryDict: {'a': ['val', 'val'], 'b': ['val']}>

-

QueryDict.__getitem__(key)¶ -

Returns the value for the given key. If the key has more than one value,

it returns the last value. Raises

django.utils.datastructures.MultiValueDictKeyErrorif the key does not

exist. (This is a subclass of Python’s standardKeyError, so you can

stick to catchingKeyError.)

-

QueryDict.__setitem__(key, value)¶ -

Sets the given key to

[value](a list whose single element is

value). Note that this, as other dictionary functions that have side

effects, can only be called on a mutableQueryDict(such as one that

was created viaQueryDict.copy()).

-

QueryDict.__contains__(key)¶ -

Returns

Trueif the given key is set. This lets you do, e.g.,if "foo".

in request.GET

-

QueryDict.get(key, default=None)¶ -

Uses the same logic as

__getitem__(), with a hook for returning a

default value if the key doesn’t exist.

-

QueryDict.setdefault(key, default=None)¶ -

Like

dict.setdefault(), except it uses__setitem__()internally.

-

QueryDict.update(other_dict)¶ -

Takes either a

QueryDictor a dictionary. Likedict.update(),

except it appends to the current dictionary items rather than replacing

them. For example:>>> q = QueryDict('a=1', mutable=True) >>> q.update({'a': '2'}) >>> q.getlist('a') ['1', '2'] >>> q['a'] # returns the last '2'

-

QueryDict.items()¶ -

Like

dict.items(), except this uses the same last-value logic as

__getitem__()and returns an iterator object instead of a view object.

For example:>>> q = QueryDict('a=1&a=2&a=3') >>> list(q.items()) [('a', '3')]

-

QueryDict.values()¶ -

Like

dict.values(), except this uses the same last-value logic as

__getitem__()and returns an iterator instead of a view object. For

example:>>> q = QueryDict('a=1&a=2&a=3') >>> list(q.values()) ['3']

In addition, QueryDict has the following methods:

-

QueryDict.copy()¶ -

Returns a copy of the object using

copy.deepcopy(). This copy will

be mutable even if the original was not.

-

QueryDict.getlist(key, default=None)¶ -

Returns a list of the data with the requested key. Returns an empty list if

the key doesn’t exist anddefaultisNone. It’s guaranteed to

return a list unless the default value provided isn’t a list.

-

QueryDict.setlist(key, list_)¶ -

Sets the given key to

list_(unlike__setitem__()).

-

QueryDict.appendlist(key, item)¶ -

Appends an item to the internal list associated with key.

-

QueryDict.setlistdefault(key, default_list=None)¶ -

Like

setdefault(), except it takes a list of values instead of a

single value.

-

QueryDict.lists()¶ -

Like

items(), except it includes all values, as a list, for each

member of the dictionary. For example:>>> q = QueryDict('a=1&a=2&a=3') >>> q.lists() [('a', ['1', '2', '3'])]

-

QueryDict.pop(key)¶ -

Returns a list of values for the given key and removes them from the

dictionary. RaisesKeyErrorif the key does not exist. For example:>>> q = QueryDict('a=1&a=2&a=3', mutable=True) >>> q.pop('a') ['1', '2', '3']

-

QueryDict.popitem()¶ -

Removes an arbitrary member of the dictionary (since there’s no concept

of ordering), and returns a two value tuple containing the key and a list

of all values for the key. RaisesKeyErrorwhen called on an empty

dictionary. For example:>>> q = QueryDict('a=1&a=2&a=3', mutable=True) >>> q.popitem() ('a', ['1', '2', '3'])

-

QueryDict.dict()¶ -

Returns a

dictrepresentation ofQueryDict. For every (key, list)

pair inQueryDict,dictwill have (key, item), where item is one

element of the list, using the same logic asQueryDict.__getitem__():>>> q = QueryDict('a=1&a=3&a=5') >>> q.dict() {'a': '5'}

-

QueryDict.urlencode(safe=None)¶ -

Returns a string of the data in query string format. For example:

>>> q = QueryDict('a=2&b=3&b=5') >>> q.urlencode() 'a=2&b=3&b=5'

Use the

safeparameter to pass characters which don’t require encoding.

For example:>>> q = QueryDict(mutable=True) >>> q['next'] = '/a&b/' >>> q.urlencode(safe='/') 'next=/a%26b/'

HttpResponse objects¶

-

class

HttpResponse¶

In contrast to HttpRequest objects, which are created automatically by

Django, HttpResponse objects are your responsibility. Each view you

write is responsible for instantiating, populating, and returning an

HttpResponse.

The HttpResponse class lives in the django.http module.

Usage¶

Passing strings¶

Typical usage is to pass the contents of the page, as a string, bytestring,

or memoryview, to the HttpResponse constructor:

>>> from django.http import HttpResponse >>> response = HttpResponse("Here's the text of the web page.") >>> response = HttpResponse("Text only, please.", content_type="text/plain") >>> response = HttpResponse(b'Bytestrings are also accepted.') >>> response = HttpResponse(memoryview(b'Memoryview as well.'))

But if you want to add content incrementally, you can use response as a

file-like object:

>>> response = HttpResponse() >>> response.write("<p>Here's the text of the web page.</p>") >>> response.write("<p>Here's another paragraph.</p>")

Passing iterators¶

Finally, you can pass HttpResponse an iterator rather than strings.

HttpResponse will consume the iterator immediately, store its content as a

string, and discard it. Objects with a close() method such as files and

generators are immediately closed.

If you need the response to be streamed from the iterator to the client, you

must use the StreamingHttpResponse class instead.

Setting header fields¶

To set or remove a header field in your response, use

HttpResponse.headers:

>>> response = HttpResponse() >>> response.headers['Age'] = 120 >>> del response.headers['Age']

You can also manipulate headers by treating your response like a dictionary:

>>> response = HttpResponse() >>> response['Age'] = 120 >>> del response['Age']

This proxies to HttpResponse.headers, and is the original interface offered

by HttpResponse.

When using this interface, unlike a dictionary, del doesn’t raise

KeyError if the header field doesn’t exist.

You can also set headers on instantiation:

>>> response = HttpResponse(headers={'Age': 120})

For setting the Cache-Control and Vary header fields, it is recommended

to use the patch_cache_control() and

patch_vary_headers() methods from

django.utils.cache, since these fields can have multiple, comma-separated

values. The “patch” methods ensure that other values, e.g. added by a

middleware, are not removed.

HTTP header fields cannot contain newlines. An attempt to set a header field

containing a newline character (CR or LF) will raise BadHeaderError

Telling the browser to treat the response as a file attachment¶

To tell the browser to treat the response as a file attachment, set the

Content-Type and Content-Disposition headers. For example, this is how

you might return a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet:

>>> response = HttpResponse(my_data, headers={ ... 'Content-Type': 'application/vnd.ms-excel', ... 'Content-Disposition': 'attachment; filename="foo.xls"', ... })

There’s nothing Django-specific about the Content-Disposition header, but

it’s easy to forget the syntax, so we’ve included it here.

Attributes¶

-

HttpResponse.content¶ -

A bytestring representing the content, encoded from a string if necessary.

-

HttpResponse.headers¶ -

A case insensitive, dict-like object that provides an interface to all

HTTP headers on the response. See Setting header fields.

-

HttpResponse.charset¶ -

A string denoting the charset in which the response will be encoded. If not

given atHttpResponseinstantiation time, it will be extracted from

content_typeand if that is unsuccessful, the

DEFAULT_CHARSETsetting will be used.

-

HttpResponse.status_code¶ -

The HTTP status code for the response.

Unless

reason_phraseis explicitly set, modifying the value of

status_codeoutside the constructor will also modify the value of

reason_phrase.

-

HttpResponse.reason_phrase¶ -

The HTTP reason phrase for the response. It uses the HTTP standard’s default reason phrases.

Unless explicitly set,

reason_phraseis determined by the value of

status_code.

-

HttpResponse.streaming¶ -

This is always

False.This attribute exists so middleware can treat streaming responses

differently from regular responses.

-

HttpResponse.closed¶ -

Trueif the response has been closed.

Methods¶

-

HttpResponse.__init__(content=b», content_type=None, status=200, reason=None, charset=None, headers=None)¶ -

Instantiates an

HttpResponseobject with the given page content,

content type, and headers.contentis most commonly an iterator, bytestring,memoryview,

or string. Other types will be converted to a bytestring by encoding their

string representation. Iterators should return strings or bytestrings and

those will be joined together to form the content of the response.content_typeis the MIME type optionally completed by a character set

encoding and is used to fill the HTTPContent-Typeheader. If not

specified, it is formed by'text/html'and the

DEFAULT_CHARSETsettings, by default:

"text/html; charset=utf-8".statusis the HTTP status code for the response.

You can use Python’shttp.HTTPStatusfor meaningful aliases,

such asHTTPStatus.NO_CONTENT.reasonis the HTTP response phrase. If not provided, a default phrase

will be used.charsetis the charset in which the response will be encoded. If not

given it will be extracted fromcontent_type, and if that

is unsuccessful, theDEFAULT_CHARSETsetting will be used.headersis adictof HTTP headers for the response.

-

HttpResponse.__setitem__(header, value)¶ -

Sets the given header name to the given value. Both

headerand

valueshould be strings.

-

HttpResponse.__delitem__(header)¶ -

Deletes the header with the given name. Fails silently if the header

doesn’t exist. Case-insensitive.

-

HttpResponse.__getitem__(header)¶ -

Returns the value for the given header name. Case-insensitive.

-

HttpResponse.get(header, alternate=None)¶ -

Returns the value for the given header, or an

alternateif the header

doesn’t exist.

-

HttpResponse.has_header(header)¶ -

Returns

TrueorFalsebased on a case-insensitive check for a

header with the given name.

-

HttpResponse.items()¶ -

Acts like

dict.items()for HTTP headers on the response.

-

HttpResponse.setdefault(header, value)¶ -

Sets a header unless it has already been set.

-

HttpResponse.set_cookie(key, value=», max_age=None, expires=None, path=‘/’, domain=None, secure=False, httponly=False, samesite=None)¶ -

Sets a cookie. The parameters are the same as in the

Morselcookie object in the Python standard library.-

max_ageshould be atimedeltaobject, an integer

number of seconds, orNone(default) if the cookie should last only

as long as the client’s browser session. Ifexpiresis not specified,

it will be calculated.Changed in Django 4.1:

Support for

timedeltaobjects was added. -

expiresshould either be a string in the format

"Wdy, DD-Mon-YY HH:MM:SS GMT"or adatetime.datetimeobject

in UTC. Ifexpiresis adatetimeobject, themax_age

will be calculated. -

Use

domainif you want to set a cross-domain cookie. For example,

domain="example.com"will set a cookie that is readable by the

domains www.example.com, blog.example.com, etc. Otherwise, a cookie will

only be readable by the domain that set it. -

Use

secure=Trueif you want the cookie to be only sent to the server

when a request is made with thehttpsscheme. -

Use

httponly=Trueif you want to prevent client-side

JavaScript from having access to the cookie.HttpOnly is a flag included in a Set-Cookie HTTP response header. It’s

part of the RFC 6265 standard for cookies

and can be a useful way to mitigate the risk of a client-side script

accessing the protected cookie data. -

Use

samesite='Strict'orsamesite='Lax'to tell the browser not

to send this cookie when performing a cross-origin request. SameSite

isn’t supported by all browsers, so it’s not a replacement for Django’s

CSRF protection, but rather a defense in depth measure.Use

samesite='None'(string) to explicitly state that this cookie is

sent with all same-site and cross-site requests.

Warning

RFC 6265 states that user agents should

support cookies of at least 4096 bytes. For many browsers this is also

the maximum size. Django will not raise an exception if there’s an

attempt to store a cookie of more than 4096 bytes, but many browsers

will not set the cookie correctly. -

-

HttpResponse.set_signed_cookie(key, value, salt=», max_age=None, expires=None, path=‘/’, domain=None, secure=False, httponly=False, samesite=None)¶ -

Like

set_cookie(), but

cryptographic signing the cookie before setting

it. Use in conjunction withHttpRequest.get_signed_cookie().

You can use the optionalsaltargument for added key strength, but

you will need to remember to pass it to the corresponding

HttpRequest.get_signed_cookie()call.

-

HttpResponse.delete_cookie(key, path=‘/’, domain=None, samesite=None)¶ -

Deletes the cookie with the given key. Fails silently if the key doesn’t

exist.Due to the way cookies work,

pathanddomainshould be the same

values you used inset_cookie()– otherwise the cookie may not be

deleted.

-

HttpResponse.close()¶ -

This method is called at the end of the request directly by the WSGI

server.

-

HttpResponse.write(content)¶ -

This method makes an

HttpResponseinstance a file-like object.

-

HttpResponse.flush()¶ -

This method makes an

HttpResponseinstance a file-like object.

-

HttpResponse.tell()¶ -

This method makes an

HttpResponseinstance a file-like object.

-

HttpResponse.getvalue()¶ -

Returns the value of

HttpResponse.content. This method makes

anHttpResponseinstance a stream-like object.

-

HttpResponse.readable()¶ -

Always

False. This method makes anHttpResponseinstance a

stream-like object.

-

HttpResponse.seekable()¶ -

Always

False. This method makes anHttpResponseinstance a

stream-like object.

-

HttpResponse.writable()¶ -

Always

True. This method makes anHttpResponseinstance a

stream-like object.

-

HttpResponse.writelines(lines)¶ -

Writes a list of lines to the response. Line separators are not added. This

method makes anHttpResponseinstance a stream-like object.

HttpResponse subclasses¶

Django includes a number of HttpResponse subclasses that handle different

types of HTTP responses. Like HttpResponse, these subclasses live in

django.http.

-

class

HttpResponseRedirect¶ -

The first argument to the constructor is required – the path to redirect

to. This can be a fully qualified URL

(e.g.'https://www.yahoo.com/search/'), an absolute path with no domain

(e.g.'/search/'), or even a relative path (e.g.'search/'). In that

last case, the client browser will reconstruct the full URL itself

according to the current path. SeeHttpResponsefor other optional

constructor arguments. Note that this returns an HTTP status code 302.-

url¶ -

This read-only attribute represents the URL the response will redirect

to (equivalent to theLocationresponse header).

-

-

class

HttpResponsePermanentRedirect¶ -

Like

HttpResponseRedirect, but it returns a permanent redirect

(HTTP status code 301) instead of a “found” redirect (status code 302).

-

class

HttpResponseNotModified¶ -

The constructor doesn’t take any arguments and no content should be added

to this response. Use this to designate that a page hasn’t been modified

since the user’s last request (status code 304).

-

class

HttpResponseBadRequest¶ -

Acts just like

HttpResponsebut uses a 400 status code.

-

class

HttpResponseNotFound¶ -

Acts just like

HttpResponsebut uses a 404 status code.

-

class

HttpResponseForbidden¶ -

Acts just like

HttpResponsebut uses a 403 status code.

-

class

HttpResponseNotAllowed¶ -

Like

HttpResponse, but uses a 405 status code. The first argument

to the constructor is required: a list of permitted methods (e.g.

['GET', 'POST']).

-

class

HttpResponseGone¶ -

Acts just like

HttpResponsebut uses a 410 status code.

-

class

HttpResponseServerError¶ -

Acts just like

HttpResponsebut uses a 500 status code.

Note

If a custom subclass of HttpResponse implements a render

method, Django will treat it as emulating a

SimpleTemplateResponse, and the

render method must itself return a valid response object.

Custom response classes¶

If you find yourself needing a response class that Django doesn’t provide, you

can create it with the help of http.HTTPStatus. For example:

from http import HTTPStatus from django.http import HttpResponse class HttpResponseNoContent(HttpResponse): status_code = HTTPStatus.NO_CONTENT

JsonResponse objects¶

-

class

JsonResponse(data, encoder=DjangoJSONEncoder, safe=True, json_dumps_params=None, **kwargs)¶ -

An

HttpResponsesubclass that helps to create a JSON-encoded

response. It inherits most behavior from its superclass with a couple

differences:Its default

Content-Typeheader is set to application/json.The first parameter,

data, should be adictinstance. If the

safeparameter is set toFalse(see below) it can be any

JSON-serializable object.The

encoder, which defaults to

django.core.serializers.json.DjangoJSONEncoder, will be used to

serialize the data. See JSON serialization for more details about this serializer.The

safeboolean parameter defaults toTrue. If it’s set to

False, any object can be passed for serialization (otherwise only

dictinstances are allowed). IfsafeisTrueand a non-dict

object is passed as the first argument, aTypeErrorwill be raised.The

json_dumps_paramsparameter is a dictionary of keyword arguments

to pass to thejson.dumps()call used to generate the response.

Usage¶

Typical usage could look like:

>>> from django.http import JsonResponse >>> response = JsonResponse({'foo': 'bar'}) >>> response.content b'{"foo": "bar"}'

Serializing non-dictionary objects¶

In order to serialize objects other than dict you must set the safe

parameter to False:

>>> response = JsonResponse([1, 2, 3], safe=False)

Without passing safe=False, a TypeError will be raised.

Note that an API based on dict objects is more extensible, flexible, and

makes it easier to maintain forwards compatibility. Therefore, you should avoid

using non-dict objects in JSON-encoded response.

Warning

Before the 5th edition of ECMAScript it was possible to

poison the JavaScript Array constructor. For this reason, Django does

not allow passing non-dict objects to the

JsonResponse constructor by default. However, most

modern browsers implement ECMAScript 5 which removes this attack vector.

Therefore it is possible to disable this security precaution.

Changing the default JSON encoder¶

If you need to use a different JSON encoder class you can pass the encoder

parameter to the constructor method:

>>> response = JsonResponse(data, encoder=MyJSONEncoder)

StreamingHttpResponse objects¶

-

class

StreamingHttpResponse¶

The StreamingHttpResponse class is used to stream a response from

Django to the browser. You might want to do this if generating the response

takes too long or uses too much memory. For instance, it’s useful for

generating large CSV files.

Performance considerations

Django is designed for short-lived requests. Streaming responses will tie

a worker process for the entire duration of the response. This may result

in poor performance.

Generally speaking, you should perform expensive tasks outside of the

request-response cycle, rather than resorting to a streamed response.

The StreamingHttpResponse is not a subclass of HttpResponse,

because it features a slightly different API. However, it is almost identical,

with the following notable differences:

- It should be given an iterator that yields bytestrings as content.

- You cannot access its content, except by iterating the response object

itself. This should only occur when the response is returned to the client. - It has no

contentattribute. Instead, it has a

streaming_contentattribute. - You cannot use the file-like object

tell()orwrite()methods.

Doing so will raise an exception.

StreamingHttpResponse should only be used in situations where it is

absolutely required that the whole content isn’t iterated before transferring

the data to the client. Because the content can’t be accessed, many

middleware can’t function normally. For example the ETag and

Content-Length headers can’t be generated for streaming responses.

The HttpResponseBase base class is common between

HttpResponse and StreamingHttpResponse.

Attributes¶

-

StreamingHttpResponse.streaming_content¶ -

An iterator of the response content, bytestring encoded according to

HttpResponse.charset.

-

StreamingHttpResponse.status_code¶ -

The HTTP status code for the response.

Unless

reason_phraseis explicitly set, modifying the value of

status_codeoutside the constructor will also modify the value of

reason_phrase.

-

StreamingHttpResponse.reason_phrase¶ -

The HTTP reason phrase for the response. It uses the HTTP standard’s default reason phrases.

Unless explicitly set,

reason_phraseis determined by the value of

status_code.

-

StreamingHttpResponse.streaming¶ -

This is always

True.

FileResponse objects¶

-

class

FileResponse(open_file, as_attachment=False, filename=», **kwargs)¶ -

FileResponseis a subclass ofStreamingHttpResponse

optimized for binary files. It uses wsgi.file_wrapper if provided by the wsgi

server, otherwise it streams the file out in small chunks.If

as_attachment=True, theContent-Dispositionheader is set to

attachment, which asks the browser to offer the file to the user as a

download. Otherwise, aContent-Dispositionheader with a value of

inline(the browser default) will be set only if a filename is

available.If

open_filedoesn’t have a name or if the name ofopen_fileisn’t

appropriate, provide a custom file name using thefilenameparameter.

Note that if you pass a file-like object likeio.BytesIO, it’s your

task toseek()it before passing it toFileResponse.The

Content-LengthandContent-Typeheaders are automatically set

when they can be guessed from contents ofopen_file.

FileResponse accepts any file-like object with binary content, for example

a file open in binary mode like so:

>>> from django.http import FileResponse >>> response = FileResponse(open('myfile.png', 'rb'))

The file will be closed automatically, so don’t open it with a context manager.

Methods¶

-

FileResponse.set_headers(open_file)¶ -

This method is automatically called during the response initialization and

set various headers (Content-Length,Content-Type, and

Content-Disposition) depending onopen_file.

HttpResponseBase class¶

-

class

HttpResponseBase¶

The HttpResponseBase class is common to all Django responses.

It should not be used to create responses directly, but it can be

useful for type-checking.

Объекты запроса и ответа¶

Краткая информация¶

Django использует объекты запроса и ответа для передачи состояния через систему.

Когда страница запрашивается, Django создает объект HttpRequest, содержащий метаданные о запросе. Затем Django загружает соответствующее представление, передавая HttpRequest в качестве первого аргумента функции представления. Каждое представление отвечает за возврат объекта HttpResponse.

Этот документ объясняет API для объектов HttpRequest и HttpResponse, которые определены в модуле django.http.

Объекты HttpRequest¶

-

class

HttpRequest[исходный код]¶

Атрибуты¶

Все атрибуты должны считаться доступными только для чтения, если не указано иное.

-

HttpRequest.scheme¶ -

Строка, представляющая схему запроса (обычно

httpилиhttps).

-

HttpRequest.body¶ -

Необработанное тело HTTP-запроса в виде байтовой строки. Это полезно для обработки данных разными способами, чем обычные формы HTML: двоичные изображения, полезная нагрузка XML и т.д. Для обработки данных обычной формы используйте

HttpRequest.POST.Вы также можете читать из

HttpRequest, используя файловый интерфейсHttpRequest.read()илиHttpRequest.readline(). Доступ к атрибутуbodyпосле чтения запроса с помощью любого из этих методов потока ввода-вывода приведет к возникновению исключенияRawPostDataException.

-

HttpRequest.path¶ -

Строка, представляющая полный путь к запрашиваемой странице, не включая схему, домен или строку запроса.

Например:

"/music/bands/the_beatles/"

-

HttpRequest.path_info¶ -

В некоторых конфигурациях веб-серверов часть URL после имени хоста разделяется на часть префикса скрипта и часть информации о пути. Атрибут

path_infoвсегда содержит информационную часть пути, независимо от того, какой веб-сервер используется. Использование этого атрибута вместоpathможет облегчить перемещение кода между тестовыми и развертывающими серверами.Например, если

WSGIScriptAliasдля вашего приложения установлен на"/minfo", тогдаpathможет быть"/minfo/music/band/the_beatles/"иpath_infoбудет"/music/band/the_beatles/".

-

HttpRequest.method¶ -

Строка, представляющая метод HTTP, используемый в запросе. Это гарантированно будет в верхнем регистре. Например:

if request.method == 'GET': do_something() elif request.method == 'POST': do_something_else()

-

HttpRequest.encoding¶ -

Строка, представляющая текущую кодировку, используемую для декодирования данных отправки формы (или

None, что означает, что используется параметрDEFAULT_CHARSET). Вы можете записать в этот атрибут, чтобы изменить кодировку, используемую при доступе к данным формы. При любом последующем доступе к атрибуту (например, чтение изGETилиPOST) будет использоваться новое значениеencoding. Полезно, если вы знаете, что данные формы не находятся в кодировкеDEFAULT_CHARSET.

-

HttpRequest.content_type¶ -

Строка, представляющая MIME-тип запроса, извлеченная из заголовка

CONTENT_TYPE.

-

HttpRequest.content_params¶ -

Словарь параметров ключ/значение, включенных в заголовок

CONTENT_TYPE.

-

HttpRequest.GET¶ -

Словарный объект, содержащий все заданные параметры HTTP GET. Смотрите документацию

QueryDictниже.

-

HttpRequest.POST¶ -

Подобный словарю объект, содержащий все заданные параметры HTTP POST, при условии, что запрос содержит данные формы. Смотрите документацию

QueryDictниже. Если вам нужно получить доступ к необработанным данным или данным, не относящимся к форме, размещенным в запросе, используйте вместо этого атрибутHttpRequest.body.Возможно, что запрос может поступить через POST с пустым словарем POST — если, скажем, форма запрашивается через метод POST HTTP, но не включает данные формы. Таким образом, не следует использовать

if request.POSTдля проверки использования метода POST; вместо этого используйтеif request.method == "POST"(смотрите attr:HttpRequest.method).POSTне включает информацию о загрузке файла. Смотрите attr:FILES.

-

HttpRequest.COOKIES¶ -

Словарь, содержащий все файлы cookie. Ключи и значения представляют собой строки.

-

HttpRequest.FILES¶ -

Словарный объект, содержащий все загруженные файлы. Каждый ключ в

FILES— этоnameиз<input type="file" name="">. Каждое значение вFILES— этоUploadedFile.Смотрите Управление файлами для получения дополнительной информации.

FILESбудет содержать данные только в том случае, если метод запроса был POST, а<form>, отправленная в запрос, имелаenctype="multipart/form-data". В противном случаеFILESбудет пустым объектом, похожим на словарь.

-

HttpRequest.META¶ -

Словарь, содержащий все доступные заголовки HTTP. Доступные заголовки зависят от клиента и сервера, но вот несколько примеров:

CONTENT_LENGTH— длина тела запроса (в виде строки).CONTENT_TYPE– MIME-тип тела запроса.HTTP_ACCEPT– допустимые типы содержимого для ответа.HTTP_ACCEPT_ENCODING– допустимые кодировки для ответа.HTTP_ACCEPT_LANGUAGE— допустимые языки для ответа.HTTP_HOST– заголовок HTTP-хоста, отправляемый клиентом.HTTP_REFERER– ссылающаяся страница, если есть.HTTP_USER_AGENT— строка агента клиента.QUERY_STRING— строка запроса в виде единственной (неанализируемой) строки.REMOTE_ADDR— IP-адрес клиента.REMOTE_HOST— имя хоста клиента.REMOTE_USER– Пользователь, аутентифицированный веб-сервером, если таковой имеется.REQUEST_METHOD— строка, такая какGETилиPOST.SERVER_NAME— имя хоста сервера.SERVER_PORT– порт сервера (в виде строки).

За исключением

CONTENT_LENGTHиCONTENT_TYPE, как указано выше, любые заголовки HTTP в запросе преобразуются в ключиMETAпутем преобразования всех символов в верхний регистр, замены дефисов символами подчеркивания и добавления символа префиксаHTTP_к имени. Так, например, заголовокX-Benderбудет сопоставлен с ключомMETAHTTP_X_BENDER.Обратите внимание, что

runserverудаляет все заголовки с символами подчеркивания в имени, поэтому вы не увидите их вMETA. Это предотвращает подмену заголовков, основанную на двусмысленности между подчеркиванием и тире, которые нормализуются к подчеркиванию в переменных окружения WSGI. Это соответствует поведению таких веб-серверов, как Nginx и Apache 2.4+.HttpRequest.headers— это более простой способ получить доступ ко всем заголовкам с префиксом HTTP, плюсCONTENT_LENGTHиCONTENT_TYPE.

-

Нечувствительный к регистру объект типа

dict, который обеспечивает доступ ко всем заголовкам с префиксом HTTP (плюсContent-LengthиContent-Type) из запроса.Название каждого заголовка стилизовано с заглавной буквой (например,

User-Agent) при отображении. Вы можете обращаться к заголовкам без учета регистра:>>> request.headers {'User-Agent': 'Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_12_6', ...} >>> 'User-Agent' in request.headers True >>> 'user-agent' in request.headers True >>> request.headers['User-Agent'] Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_12_6) >>> request.headers['user-agent'] Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_12_6) >>> request.headers.get('User-Agent') Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_12_6) >>> request.headers.get('user-agent') Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_12_6)

Для использования, например, в шаблонах Django, заголовки также можно искать с помощью подчеркивания вместо дефисов:

{{ request.headers.user_agent }}

-

HttpRequest.resolver_match¶ -

Экземпляр

ResolverMatch, представляющий разрешенный URL. Этот атрибут устанавливается только после того, как произошло разрешение URL, что означает, что он доступен во всех представлениях, но не в промежуточном программном обеспечении middleware, которое выполняется до того, как происходит разрешение URL (хотя вы можете использовать его вprocess_view()).

Атрибуты, установленные кодом приложения¶

Django сам не устанавливает эти атрибуты, но использует их, если они установлены вашим приложением.

-

HttpRequest.current_app¶ -

Тег шаблона

urlбудет использовать свое значение в качестве аргументаcurrent_appдляreverse().

-

HttpRequest.urlconf¶ -

Он будет использоваться как корневой URLconf для текущего запроса, переопределив параметр

ROOT_URLCONF. Смотрите Как Django обрабатывает запрос для подробностей.Для параметра

urlconfможно задать значениеNone, чтобы отменить любые изменения, сделанные предыдущим промежуточным программным обеспечением, и вернуться к использованиюROOT_URLCONF.

-

HttpRequest.exception_reporter_filter¶ -

Будет использоваться вместо

DEFAULT_EXCEPTION_REPORTER_FILTERдля текущего запроса. Смотрите Пользовательские отчеты об ошибках для подробностей.

-

HttpRequest.exception_reporter_class¶ -

Будет использоваться вместо

DEFAULT_EXCEPTION_REPORTERдля текущего запроса. Смотрите Пользовательские отчеты об ошибках для подробностей.

Атрибуты, установленные промежуточным программным обеспечением middleware¶

Некоторые из middleware, включенного в приложения contrib Django, устанавливают атрибуты по запросу. Если вы не видите атрибут в запросе, убедитесь, что соответствующий класс промежуточного ПО указан в MIDDLEWARE.

-

HttpRequest.session¶ -

Из

SessionMiddleware: читаемый и записываемый, подобный словарю объект, представляющий текущий сеанс.

-

HttpRequest.site¶ -

Из

CurrentSiteMiddleware: экземплярSiteилиRequestSite, возвращенныйget_current_site(), представляющий текущий сайт.

-

HttpRequest.user¶ -

Из

AuthenticationMiddleware: экземплярAUTH_USER_MODEL, представляющий текущего вошедшего в систему пользователя. Если пользователь в настоящее время не вошел в систему,userбудет установлен как экземплярAnonymousUser. Вы можете отличить их друг от друга с помощьюis_authenticated, например:if request.user.is_authenticated: ... # Do something for logged-in users. else: ... # Do something for anonymous users.

Методы¶

-

HttpRequest.get_host()[исходный код]¶ -

Возвращает исходный хост запроса, используя информацию из заголовков

HTTP_X_FORWARDED_HOST(еслиUSE_X_FORWARDED_HOSTвключен) иHTTP_HOSTв указанном порядке. Если они не предоставляют значение, метод использует комбинациюSERVER_NAMEиSERVER_PORT, как подробно описано в PEP 3333.Пример:

"127.0.0.1:8000"Поднимает

django.core.exceptions.DisallowedHost, если хост не находится вALLOWED_HOSTSили доменное имя недопустимо согласно RFC 1034/1035.Примечание

Метод

get_host()не работает, когда хост находится за несколькими прокси. Одним из решений является использование промежуточного программного обеспечения middleware для перезаписи заголовков прокси, как в следующем примере:class MultipleProxyMiddleware: FORWARDED_FOR_FIELDS = [ 'HTTP_X_FORWARDED_FOR', 'HTTP_X_FORWARDED_HOST', 'HTTP_X_FORWARDED_SERVER', ] def __init__(self, get_response): self.get_response = get_response def __call__(self, request): """ Rewrites the proxy headers so that only the most recent proxy is used. """ for field in self.FORWARDED_FOR_FIELDS: if field in request.META: if ',' in request.META[field]: parts = request.META[field].split(',') request.META[field] = parts[-1].strip() return self.get_response(request)

Это промежуточное ПО должно быть расположено перед любым другим промежуточным ПО, которое полагается на значение

get_host()– например,CommonMiddlewareилиCsrfViewMiddleware.

-

HttpRequest.get_port()[исходный код]¶ -

Возвращает исходный порт запроса, используя информацию из переменных

HTTP_X_FORWARDED_PORT(еслиUSE_X_FORWARDED_PORTвключен) иSERVER_PORTиMETAв указанном порядке.

-

HttpRequest.get_full_path()[исходный код]¶ -

Возвращает

pathплюс добавленную строку запроса, если применимо.Пример:

"/music/groups/the_beatles/?print=true"

-

HttpRequest.get_full_path_info()[исходный код]¶ -

Например

get_full_path(), но используетpath_infoвместоpath.Пример:

"/minfo/music/bands/the_beatles/?print=true"

-

HttpRequest.build_absolute_uri(location=None)[исходный код]¶ -

Возвращает абсолютную форму URI для

location. Если местоположение не указано, для него будет установлено значениеrequest.get_full_path().Если местоположение уже является абсолютным URI, оно не будет изменено. В противном случае абсолютный URI создается с использованием переменных сервера, доступных в этом запросе. Например:

>>> request.build_absolute_uri() 'https://example.com/music/bands/the_beatles/?print=true' >>> request.build_absolute_uri('/bands/') 'https://example.com/bands/' >>> request.build_absolute_uri('https://example2.com/bands/') 'https://example2.com/bands/'

Примечание

Смешивание HTTP и HTTPS на одном сайте не рекомендуется, поэтому

build_absolute_uri()всегда будет генерировать абсолютный URI с той же схемой, которую имеет текущий запрос. Если вам нужно перенаправить пользователей на HTTPS, лучше всего позволить вашему веб-серверу перенаправить весь HTTP-трафик на HTTPS.

-

HttpRequest.get_signed_cookie(key, default=RAISE_ERROR, salt=», max_age=None)[исходный код]¶ -

Возвращает значение cookie для подписанного файла cookie или вызывает исключение

django.core.signing.BadSignature, если подпись больше не действительна. Если вы укажете аргументdefault, исключение будет подавлено, и вместо него будет возвращено значение по умолчанию.Необязательный аргумент

saltможет использоваться для обеспечения дополнительной защиты от атак грубой силы на ваш секретный ключ. Если указан аргументmax_age, он будет сравниваться с подписанной меткой времени, прикрепленной к значению куки, чтобы убедиться, что куки не старше, чемmax_ageсекунд.Например:

>>> request.get_signed_cookie('name') 'Tony' >>> request.get_signed_cookie('name', salt='name-salt') 'Tony' # assuming cookie was set using the same salt >>> request.get_signed_cookie('nonexistent-cookie') ... KeyError: 'nonexistent-cookie' >>> request.get_signed_cookie('nonexistent-cookie', False) False >>> request.get_signed_cookie('cookie-that-was-tampered-with') ... BadSignature: ... >>> request.get_signed_cookie('name', max_age=60) ... SignatureExpired: Signature age 1677.3839159 > 60 seconds >>> request.get_signed_cookie('name', False, max_age=60) False

Смотрите криптографическая подпись для получения дополнительной информации.

-

HttpRequest.is_secure()[исходный код]¶ -

Возвращает

True, если запрос безопасен; то есть, если это было сделано с HTTPS.

-

HttpRequest.accepts(mime_type)[исходный код]¶ -

Возвращает

True, если заголовок запросаAcceptсовпадает с аргументомmime_type:>>> request.accepts('text/html') True

Большинство браузеров по умолчанию отправляют

Accept: */*, поэтому для всех типов содержимого будет возвращеноTrue. Установка явного заголовкаAcceptв запросах API может быть полезна для возврата другого типа контента только для этих потребителей. Смотрите Пример переговоров по содержанию для использованияaccepts()для возврата различного контента потребителям API.Если ответ зависит от содержимого заголовка

Acceptи вы используете какую-либо форму кеширования, например, в Djangocache middleware, вам следует декорировать представление с помощьюvar_on_headers('Accept'), чтобы ответы правильно кэшировались.

-

HttpRequest.read(size=None)[исходный код]¶

-

HttpRequest.readline()[исходный код]¶

-

HttpRequest.readlines()[исходный код]¶

-

HttpRequest.__iter__()[исходный код]¶ -

Методы, реализующие файловый интерфейс для чтения из экземпляра

HttpRequest. Это позволяет обрабатывать входящий запрос в потоковом режиме. Распространенным вариантом использования будет обработка больших полезных данных XML с помощью итеративного синтаксического анализатора без построения всего XML-дерева в памяти.Учитывая этот стандартный интерфейс, экземпляр

HttpRequestможет быть передан непосредственно в синтаксический анализатор XML, напримерElementTree:import xml.etree.ElementTree as ET for element in ET.iterparse(request): process(element)

Объекты QueryDict¶

-

class

QueryDict[исходный код]¶

В объекте HttpRequest атрибуты GET и POST являются экземплярами django.http.QueryDict, настроенного класса, подобного словарю для работы с несколькими значениями одного и того же ключа. Это необходимо, поскольку некоторые элементы HTML-формы, в частности <select multiple>, передают несколько значений для одного и того же ключа.

QueryDict в request.POST и request.GET будут неизменными при доступе в обычном цикле запрос/ответ. Чтобы получить изменяемую версию, вам нужно использовать QueryDict.copy().

Методы¶

QueryDict реализует все стандартные методы словаря, потому что это подкласс словаря. Здесь указаны исключения:

-

QueryDict.__init__(query_string=None, mutable=False, encoding=None)[исходный код]¶ -

Создает экземпляр объекта

QueryDictна основеquery_string.>>> QueryDict('a=1&a=2&c=3') <QueryDict: {'a': ['1', '2'], 'c': ['3']}>

Если

query_stringне передан, результирующийQueryDictбудет пустым (у него не будет ключей или значений).Большинство

QueryDict, с которыми вы столкнетесь, и в частности те, которые находятся вrequest.POSTиrequest.GET, будут неизменными. Если вы создаете один экземпляр самостоятельно, вы можете сделать его изменяемым, передав емуmutable=Trueв его «__init__().Строки для установки ключей и значений будут преобразованы из

encodingвstr. Еслиencodingне установлен, по умолчанию используетсяDEFAULT_CHARSET.

-

classmethod

QueryDict.fromkeys(iterable, value=», mutable=False, encoding=None)[исходный код]¶ -

Создает новый

QueryDictс ключами изiterableи каждым значением, равнымvalue. Например:>>> QueryDict.fromkeys(['a', 'a', 'b'], value='val') <QueryDict: {'a': ['val', 'val'], 'b': ['val']}>

-

QueryDict.__getitem__(key)¶ -

Возвращает значение для данного ключа. Если ключ имеет более одного значения, он возвращает последнее значение. Вызывает

django.utils.datastructures.MultiValueDictKeyError, если ключ не существует. (Это подкласс PythonKeyError, поэтому вы можете придерживаться перехватаKeyError.)

-

QueryDict.__setitem__(key, value)[исходный код]¶ -

Устанавливает для данного ключа значение

[значение](список, единственным элементом которого являетсязначение). Обратите внимание, что это, как и другие словарные функции, которые имеют побочные эффекты, можно вызывать только в изменяемомQueryDict(например, в том, который был создан с помощьюQueryDict.copy()).

-

QueryDict.__contains__(key)¶ -

Возвращает

True, если заданный ключ установлен. Это позволяет вам сделать, например,if "foo" in request.GET.

-

QueryDict.get(key, default=None)¶ -

Использует ту же логику, что и

__getitem__(), с ловушкой для возврата значения по умолчанию, если ключ не существует.

-

QueryDict.setdefault(key, default=None)[исходный код]¶ -

Как

dict.setdefault(), за исключением того, что он использует__setitem__()внутри.

-

QueryDict.update(other_dict)¶ -

Принимает либо

QueryDict, либо словарь. Напримерdict.update(), за исключением того, что он добавляет к текущим элементам словаря, а не заменяет их. Например:>>> q = QueryDict('a=1', mutable=True) >>> q.update({'a': '2'}) >>> q.getlist('a') ['1', '2'] >>> q['a'] # returns the last '2'

-

QueryDict.items()¶ -

Похож на

dict.items(), за исключением того, что здесь используется та же логика последнего значения, что и__getitem__(), и возвращается объект-итератор вместо объекта представления. Например:>>> q = QueryDict('a=1&a=2&a=3') >>> list(q.items()) [('a', '3')]

-

QueryDict.values()¶ -

Такой же как и

dict.values(), за исключением того, что здесь используется та же логика последнего значения, что и__getitem__(), и возвращается итератор вместо объекта представления. Например:>>> q = QueryDict('a=1&a=2&a=3') >>> list(q.values()) ['3']

Кроме того, QueryDict имеет следующие методы:

-

QueryDict.copy()[исходный код]¶ -

Возвращает копию объекта, используя

copy.deepcopy(). Эта копия будет изменяемой, даже если оригинал не был.

-

QueryDict.getlist(key, default=None)¶ -

Возвращает список данных с запрошенным ключом. Возвращает пустой список, если ключ не существует, а

defaultравенNone. Гарантируется возврат списка, если только указанное по умолчанию значение не является списком.

-

QueryDict.setlist(key, list_)[исходный код]¶ -

Устанавливает для данного ключа значение

list_(в отличие от__setitem__()).

-

QueryDict.appendlist(key, item)[исходный код]¶ -

Добавляет элемент во внутренний список, связанный с ключом.

-

QueryDict.setlistdefault(key, default_list=None)[исходный код]¶ -

Например

setdefault(), за исключением того, что он принимает список значений вместо одного значения.

-

QueryDict.lists()¶ -

Как

items(), за исключением того, что он включает все значения в виде списка для каждого члена словаря. Например:>>> q = QueryDict('a=1&a=2&a=3') >>> q.lists() [('a', ['1', '2', '3'])]

-

QueryDict.pop(key)[исходный код]¶ -

Возвращает список значений для данного ключа и удаляет их из словаря. Вызывает исключение

KeyError, если ключ не существует. Например:>>> q = QueryDict('a=1&a=2&a=3', mutable=True) >>> q.pop('a') ['1', '2', '3']

-

QueryDict.popitem()[исходный код]¶ -

Удаляет произвольный член словаря (поскольку нет концепции упорядочивания) и возвращает кортеж из двух значений, содержащий ключ и список всех значений для ключа. Вызывает ошибку

KeyErrorпри вызове пустого словаря. Например:>>> q = QueryDict('a=1&a=2&a=3', mutable=True) >>> q.popitem() ('a', ['1', '2', '3'])

-

QueryDict.dict()¶ -

Возвращает представление

QueryDictв видеdict. Для каждой пары (key, list) вQueryDict, уdictбудет (key, item), где элемент — это один элемент списка, используя ту же логику, что иQueryDict.__getitem__():>>> q = QueryDict('a=1&a=3&a=5') >>> q.dict() {'a': '5'}

-

QueryDict.urlencode(safe=None)[исходный код]¶ -

Возвращает строку данных в формате строки запроса. Например:

>>> q = QueryDict('a=2&b=3&b=5') >>> q.urlencode() 'a=2&b=3&b=5'

Используйте параметр

safeдля передачи символов, не требующих кодирования. Например:>>> q = QueryDict(mutable=True) >>> q['next'] = '/a&b/' >>> q.urlencode(safe='/') 'next=/a%26b/'

Объекты HttpResponse¶

-

class

HttpResponse[исходный код]¶

В отличие от объектов HttpRequest, которые автоматически создаются Django, ответственность за объекты HttpResponse лежит на вас. Каждое написанное вами представление отвечает за создание, заполнение и возврат HttpResponse.

Класс HttpResponse находится в модуле django.http.

Применение¶

Передача строк¶

Типичное использование — передача содержимого страницы в виде строки, байтовой строки или memoryview конструктору HttpResponse:

>>> from django.http import HttpResponse >>> response = HttpResponse("Here's the text of the web page.") >>> response = HttpResponse("Text only, please.", content_type="text/plain") >>> response = HttpResponse(b'Bytestrings are also accepted.') >>> response = HttpResponse(memoryview(b'Memoryview as well.'))

Но если вы хотите добавлять контент постепенно, вы можете использовать response как файловый объект:

>>> response = HttpResponse() >>> response.write("<p>Here's the text of the web page.</p>") >>> response.write("<p>Here's another paragraph.</p>")

Передача итераторов¶

Наконец, вы можете передать HttpResponse итератор, а не строки. HttpResponse немедленно использует итератор, сохраняет его содержимое в виде строки и отбрасывает его. Объекты с методом close(), такие как файлы и генераторы, немедленно закрываются.

Если вам нужно, чтобы ответ передавался от итератора клиенту, вы должны вместо этого использовать класс StreamingHttpResponse.

Указание браузеру рассматривать ответ как вложение файла¶

Чтобы браузер обрабатывал ответ как вложение файла, установите заголовки Content-Type и Content-Disposition. Например, вот как вы можете вернуть электронную таблицу Microsoft Excel:

>>> response = HttpResponse(my_data, headers={ ... 'Content-Type': 'application/vnd.ms-excel', ... 'Content-Disposition': 'attachment; filename="foo.xls"', ... })

В заголовке Content-Disposition нет ничего специфичного для Django, но его синтаксис легко забыть, поэтому мы включили его здесь.

Атрибуты¶

-

HttpResponse.content¶ -

Строка байтов, представляющая содержимое, при необходимости закодированное из строки.

-

Нечувствительный к регистру объект типа dict, который предоставляет интерфейс для всех заголовков HTTP в ответе. Смотрите Настройка полей заголовка.

-

HttpResponse.charset¶ -

Строка, обозначающая кодировку, в которой будет закодирован ответ. Если не задан во время создания экземпляра

HttpResponse, он будет извлечен изcontent_type, и если это не удастся, будет использоваться параметрDEFAULT_CHARSET.

-

HttpResponse.status_code¶ -

HTTP status code для ответа.

Если явно не задано

reason_phrase, изменение значенияstatus_codeвне конструктора также изменит значениеreason_phrase.

-

HttpResponse.reason_phrase¶ -

Фраза причины HTTP для ответа. Он использует фразы причины по умолчанию HTTP standard’s.

Если явно не установлено,

reason_phraseопределяется значениемstatus_code.

-

HttpResponse.streaming¶ -

Это всегда

False.Этот атрибут существует, поэтому промежуточное ПО может обрабатывать потоковые ответы иначе, чем обычные ответы.

-

HttpResponse.closed¶ -

True`, если ответ был закрыт.

Методы¶

-

HttpResponse.__init__(content=b», content_type=None, status=200, reason=None, charset=None, headers=None)[исходный код]¶ -

Создает экземпляр объекта

HttpResponseс заданным содержимым страницы, типом содержимого и заголовками.contentчаще всего представляет собой итератор, строку байтов,memoryviewили строку. Другие типы будут преобразованы в байтовую строку путем кодирования их строкового представления. Итераторы должны возвращать строки или байтовые строки, и они будут объединены вместе для формирования содержимого ответа.content_type— это тип MIME, который может быть дополнен кодировкой набора символов и используется для заполнения заголовка HTTPContent-Type. Если не указано, он формируется из'text/html'и настроекDEFAULT_CHARSET, по умолчанию:"text/html; charset=utf-8".status— это HTTP status code для ответа. Вы можете использовать Pythonhttp.HTTPStatusдля значимых псевдонимов, таких какHTTPStatus.NO_CONTENT.reason— это фраза ответа HTTP. Если не указан, будет использоваться фраза по умолчанию.charset— кодировка, в которой будет закодирован ответ. Если не задан, он будет извлечен изcontent_type, и если это не удастся, будет использована настройкаDEFAULT_CHARSET.headers— этоdictзаголовков HTTP для ответа.

-

HttpResponse.__setitem__(header, value)¶ -

Устанавливает заданное имя заголовка в заданное значение.

headerиvalueдолжны быть строками.

-

HttpResponse.__delitem__(header)¶ -

Удаляет заголовок с заданным именем. Если заголовок не существует, происходит автоматическая ошибка. Без учета регистра.

-

HttpResponse.__getitem__(header)¶ -

Возвращает значение для заданного имени заголовка. Без учета регистра.

-

HttpResponse.get(header, alternate=None)¶ -

Возвращает значение для данного заголовка или

alternate, если заголовок не существует.

-

Возвращает

TrueилиFalseна основе проверки без учета регистра для заголовка с заданным именем.

-

HttpResponse.items()¶ -

Действует как

dict.items()для заголовков HTTP в ответе.

-

HttpResponse.setdefault(header, value)¶ -

Устанавливает заголовок, если он еще не установлен.

-

HttpResponse.set_cookie(key, value=», max_age=None, expires=None, path=‘/’, domain=None, secure=False, httponly=False, samesite=None)¶ -

Устанавливает cookie. Параметры такие же, как и в объекте cookie

Morselв стандартной библиотеке Python.-

max_ageдолжен быть объектомtimedelta, целым числом секунд, илиNone(по умолчанию), если cookie должен длиться только до тех пор, пока длится сессия браузера клиента. Еслиexpiresне указано, оно будет вычислено.Changed in Django 4.1:

Добавлена поддержка объектов

timedelta. -

expiresдолжен быть строкой в формате"Wdy, DD-Mon-YY HH:MM:SS GMT"или объектомdatetime.datetimeв формате UTC. Еслиexpiresявляется объектомdatetime, будет вычисленоmax_age. -

Используйте

domain, если хотите установить междоменный файл cookie. Например,domain="example.com"установит файл cookie, доступный для чтения доменам www.example.com, blog.example.com и т.д. В противном случае файл cookie будет доступен для чтения только домену, который установить его. -

Используйте

secure=True, если вы хотите, чтобы cookie отправлялся на сервер только при запросе по схеме ``https. -

Используйте

httponly=True, если вы хотите запретить клиентскому JavaScript доступ к cookie.HttpOnly — это флаг, включенный в заголовок HTTP-ответа Set-Cookie. Это часть стандарта RFC 6265 для файлов cookie и может быть полезным способом снизить риск доступа сценария на стороне клиента к защищенным данным файлов cookie.

-

Используйте

samesite='Strict'илиsamesite='Lax', чтобы указать браузеру не отправлять этот файл cookie при выполнении запроса из разных источников. SameSite поддерживается не всеми браузерами, поэтому он не заменяет защиту Django от CSRF, а, скорее, обеспечивает глубокую защиту.Используйте

samesite='None'(строка), чтобы явно указать, что этот файл cookie отправляется со всеми запросами на одном сайте и между сайтами.

Предупреждение

RFC 6265 утверждает, что пользовательские агенты должны поддерживать файлы cookie размером не менее 4096 байт. Для многих браузеров это также максимальный размер. Django не вызовет исключение, если есть попытка сохранить cookie размером более 4096 байт, но многие браузеры не будут правильно устанавливать cookie.

-

-

HttpResponse.set_signed_cookie(key, value, salt=», max_age=None, expires=None, path=‘/’, domain=None, secure=False, httponly=False, samesite=None)¶ -

Аналогичен

set_cookie(), но криптографически подписывает cookie перед его установкой. Используйте вместе сHttpRequest.get_signed_cookie(). Вы можете использовать необязательный аргументsaltдля добавления силы ключа, но вам нужно будет не забыть передать его в соответствующий вызовHttpRequest.get_signed_cookie().

-

HttpResponse.delete_cookie(key, path=‘/’, domain=None, samesite=None)¶ -

Удаляет куки с заданным ключом. Если ключ не существует, то никаких ошибок не вызывает.

Из-за того, как работают файлы cookie, для параметров

pathиdomainдолжны быть те же значения, которые вы использовали вset_cookie()— в противном случае файл cookie не может быть удален.

-

HttpResponse.close()¶ -

Этот метод вызывается в конце запроса непосредственно сервером WSGI.

-

HttpResponse.write(content)[исходный код]¶ -

Этот метод делает экземпляр

HttpResponseфайловым объектом.

-

HttpResponse.flush()¶ -

Этот метод делает экземпляр

HttpResponseфайловым объектом.

-

HttpResponse.tell()[исходный код]¶ -

Этот метод делает экземпляр

HttpResponseфайловым объектом.

-

HttpResponse.getvalue()[исходный код]¶ -

Возвращает значение

HttpResponse.content. Этот метод делает экземплярHttpResponseподобным потоку объектом.

-

HttpResponse.readable()¶ -

Всегда

False. Этот метод делает экземплярHttpResponseподобным потоку объектом.

-

HttpResponse.seekable()¶ -

Всегда

False. Этот метод делает экземплярHttpResponseподобным потоку объектом.

-

HttpResponse.writable()[исходный код]¶ -

Всегда

True. Этот метод делает экземплярHttpResponseподобным потоку объектом.

-

HttpResponse.writelines(lines)[исходный код]¶ -

Записывает в ответ список строк. Разделители строк не добавляются. Этот метод делает экземпляр

HttpResponseподобным потоку объектом.

Подклассы HttpResponse¶

Django включает несколько подклассов HttpResponse, которые обрабатывают различные типы HTTP-ответов. Как и HttpResponse, эти подклассы находятся в django.http.

-

class

HttpResponseRedirect[исходный код]¶ -

Первый аргумент конструктора обязателен — путь для перенаправления. Это может быть полный URL-адрес (например,

'https://www.yahoo.com/search/'), абсолютный путь без домена (например,'/search/') или даже относительный путь (например,'search/'). В этом последнем случае браузер клиента восстановит сам полный URL-адрес в соответствии с текущим путем. СмотритеHttpResponseдля других необязательных аргументов конструктора. Обратите внимание, что это возвращает код состояния HTTP 302.-

url¶ -

Этот доступный только для чтения атрибут представляет URL-адрес, на который будет перенаправлен ответ (эквивалент заголовка ответа

Location).

-

-

class

HttpResponsePermanentRedirect[исходный код]¶ -

Как и

HttpResponseRedirect, но он возвращает постоянное перенаправление (код статуса HTTP 301) вместо «found» перенаправления (код статуса 302).

-

class

HttpResponseNotModified[исходный код]¶ -

Конструктор не принимает никаких аргументов, и к этому ответу не следует добавлять содержимое. Используйте, чтобы указать, что страница не изменялась с момента последнего запроса пользователя (код состояния 304).

-

class

HttpResponseBadRequest[исходный код]¶ -

Действует так же, как

HttpResponse, но использует код состояния 400.

-

class

HttpResponseNotFound[исходный код]¶ -

Действует так же, как

HttpResponse, но использует код состояния 404.

-

class

HttpResponseForbidden[исходный код]¶ -

Действует так же, как

HttpResponse, но использует код состояния 403.

-

class

HttpResponseNotAllowed[исходный код]¶ -

Как и

HttpResponse, но использует код состояния 405. Первый аргумент конструктора обязателен: список разрешенных методов (например,['GET', 'POST']).

-

class

HttpResponseGone[исходный код]¶ -

Действует так же, как

HttpResponse, но использует код состояния 410.

-

class

HttpResponseServerError[исходный код]¶ -

Действует так же, как

HttpResponse, но использует код состояния 500.

Примечание

Если пользовательский подкласс HttpResponse реализует метод render, Django будет рассматривать его как эмуляцию SimpleTemplateResponse, а метод render должен сам возвращает действительный объект ответа.

Пользовательские классы ответа¶

Если вам нужен класс ответа, который не предоставляет Django, вы можете создать его с помощью http.HTTPStatus. Например:

from http import HTTPStatus from django.http import HttpResponse class HttpResponseNoContent(HttpResponse): status_code = HTTPStatus.NO_CONTENT

Объекты JsonResponse¶

-

class

JsonResponse(data, encoder=DjangoJSONEncoder, safe=True, json_dumps_params=None, **kwargs)[исходный код]¶ -

Подкласс

HttpResponse, который помогает создавать ответ в формате JSON. Он наследует большую часть поведения от своего суперкласса с несколькими отличиями:Его заголовок

Content-Typeпо умолчанию имеет значение application/json.Первый параметр,

data, должен быть экземпляромdict. Если для параметраsafeустановлено значениеFalse(смотрите ниже), это может быть любой JSON-сериализуемый объект.Энкодер, по умолчанию :class:django.core.serializers.json.DjangoJSONEncoder, будет использоваться для сериализации данных. Смотрите JSON сериализация для получения дополнительных сведений об этом сериализаторе.

Логический параметр