Что подарить любимым? Топ идей в Каталоге Onlíner!

Наш мозг — удивительная штука. Это мощнейший инструмент, который невозможно воссоздать искусственным путем. Но и он несовершенен, допускает ошибки. Иногда в сфере долговременного хранения данных — нашей памяти. Порой этот сбой случается в массе — у большого числа людей. Этот феномен известен как эффект Манделы.

Нельсон Мандела прославился благодаря тому, что боролся за права человека, против расовой сегрегации, 27 лет провел в тюрьме, а потом стал первым президентом ЮАР и умер в 2013 году. Вот только большое число людей узнало о последнем факте с удивлением. Они поклясться могли, что Мандела умер еще в тюрьме в 80-е. И даже вспоминают, что видели отрывки с его похорон по ТВ. Помехи в коллективном сознании из альтернативной вселенной? Cбой в матрице? Или же просто проблемы с памятью?

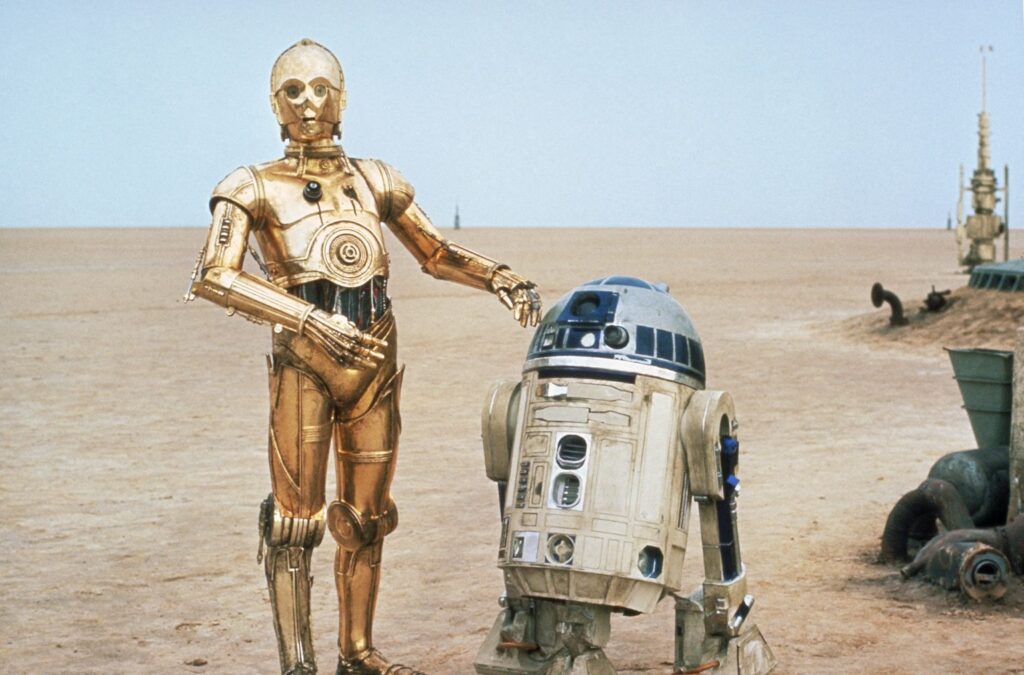

Например, еще в первом по хронологии киноэпизоде «Звездных войн» у позолоченного робота C-3PO была серебряная правая нога ниже колена. Но большинство зрителей (и даже некоторые фанаты) уверены, что он был полностью золотым.

— Я был большим фанатом «ЗВ» и в детстве смотрел их на VHS каждый день после школы, — рассказывает один из фанатов саги 70-х годов. — Думаю, я делал это около 7 месяцев — каждый день один и тот же фильм. Однажды я возвращаюсь домой, включаю фильм и… БАМ. Я просто пялюсь в замешательстве, как C-3PO полностью входит в кадр и у него серебряная нога. Это меня сразу же поражает. Назавтра я пошел в школу и рассказал своим друзьям. Они ответили, что это не так, я ошибаюсь. Но они вернулись домой, посмотрели фильм и на следующий день пришли в школу в таком же замешательстве, что и я.

Энтони Дэниелс, который в девяти фильмах перевоплощался в этого робота, говорил на мировой премьере «Пробуждения силы», что многие фанаты каким-то образом оставили эту деталь без внимания: «Даже фотограф до мозга костей Джон Джей однажды подошел ко мне на съемках и спросил: „Почему ты сегодня нацепил серебряную ногу?“ Он был фотографом и даже не заметил».

Как думаете, что приходит в голову фанатам, которые всю жизнь считают дроида золотым, а затем их понимание о столь важной вещи дает трещину? Появляются теории заговора: мол, это очень удачная интернет-мистификация, заговор съемочной группы, масонов, рептилоидов и т. д.

Конечно же, все намного проще. Просматривая «Звездные войны», зритель просто не концентрировал внимание на ногах C-3PO. Всматривался в его верхнюю половину, которая и отвечает за 95% его харизмы. А потому мозг благополучно полагал, что раз сверху дроид полностью золотой, то и в остальных местах он будет таким же. Да и в декорациях первого фильма «Новая надежда» на это можно было очень легко не обратить внимания из-за обилия песка. Серебряная нога срабатывала как зеркало и отражала не только соседнюю золотую, но и песок пустыни. Мозг просто достраивал картинку, которую разрушил особо внимательный зритель.

Чтобы сделать особенность дроида более приметной, Джей Джей Абрамс предложил в «Пробуждении силы» избавиться от серебряной ноги и использовать красную руку.

Создатели «Новой надежды» хотели наделить C-3PO какой-то особой харизмой, характером, историей, а потому решили заменить ему одну ногу на серебряную. Позже это объяснили тем, что дроид изначально был серебряным, а свое знаменитое покрытие получил где-то в промежутке между четвертым и третьим эпизодом саги по ее хронологии.

Но почему тогда у многих игрушек C-3PO присутствуют две золотые ноги? Все просто: одноцветную фигурку произвести дешевле, чем отдельно раскрашивать детской поделке одну из ног.

«Что дальше? Окажется, что у Чубакки не было усов? Или он курил сигару во всех эпизодах?» — истерично возмущаются под этим же видео зрители, которые помнят две золотые ноги у дроида.

Конечно, куда интереснее объяснять такие изменения в коллективной памяти тем, что какой-то путешественник во времени сломал нашу временную линию. Или ученые на Большом адронном коллайдере все-таки создали разрыв между параллельными мирами. Но правда, как часто бывает, куда более прозаична.

Эффект Манделы принято объяснять ложной памятью — эффектом в психологии, когда у человека развиваются ошибочные воспоминания о событиях или переживаниях, которые либо вовсе не происходили, либо подверглись искажению. Частный случай такой галлюцинации воспоминаний, расстройства памяти — конфабуляции. То, что имело место в реальности, со временем забывается, подвергается эрозии. А пробелы заполняются вымыслами.

— Мы думаем о наших воспоминаниях как о нашей личности, — цитирует Stuff профессора психологии Мэрианн Гарри из Университета Виктории. — Никто не любит сомневаться в том, кто он есть. Как правило, все воспоминания — это реконструкция. Так что все зависит от того, из чего они восстанавливаются, — правды, вымысла, микса.

Конечно, конфабуляции — это скорее из раздела психиатрии. Даже в Международном классификаторе болезней про это есть отдельная запись. Что как бы намекает на связь с психическими заболеваниями. Конфабуляции бывают разного содержания и выраженности: пациент может потеряться во времени и своем возрасте, наполнить свое прошлое фантастическими деталями и т. д. Но хорошая новость для нас заключается в том, что эффект Манделы с болезнями (скорее всего) никак не связан. А имеет место быть простая невнимательность, которая со временем в глобальных масштабах заполняется реконструированными ложными воспоминаниями, полученными в процессе нового опыта человека и социальной дезинформации. Это очень хорошо ложится на ситуацию с C-3PO. Ведь незамеченная серебряная нога осталась такой и благодаря обилию низкопробного мерча с ошибками.

Случаи конфабуляции у здоровых людей возникают чаще с возрастом. Как полагают исследователи, во многом из-за возрастных изменений в медиальной височной доле, включая гиппокамп, префронтальную кору головного мозга. Эти области важны в функционировании нашей памяти. А потому неудивительно, что многие из поколения тру-фанатов «Звездных войн» открывают для себя впервые столь неожиданную деталь про дроида.

Да и культовую фразу «Люк, я твой отец» Дарт Вейдер никогда не произносил. Если вы еще, конечно, этого не знали. Фразу обыгрывают во многих комиксах, мемах, пародиях. Но на самом деле Вейдер в диалоге с Люком произнес: «Нет, я твой отец».

Но в отрыве от контекста и Люка она куда менее понятная и интертекстуальная. Все могло начаться с фильма «Остин Пауэрс» (1999), где главный злодей произносит: «Остин, я твой отец».

А культовая фраза Жеглова «Ну и рожа у тебя, Шарапов» звучит как «Ну и рожа у тебя, Володя. Ох, рожа».

Эффект Манделы касается не только кинематографа. Иногда страдает и география.

— Прошлую ночь я провел на грани панической атаки, — пишет пользователь Reddit Bambooz_led. — Я хорошо образован. Я много путешествую, я жил во многих странах (в том числе и в Азии). У меня хорошая работа и солидный достаток среднего класса, и я горжусь тем, что являюсь эмоционально стабильным, последовательно рациональным. Но я только что понял, что не узнаю Австралию и Новую Зеландию. Совсем.

Этот бедняга с ужасом увидел, что Новая Зеландия на глобусе находится справа от Австралии, а не слева, как он всегда помнил это место. И он оказался не одинок. Плохое образование и прогулы уроков географии? Возможно, но не обязательно.

Большинство из ныне живущих вряд ли лично слышали знаковую новогоднюю речь президента России Бориса Ельцина в 1999 году. Но в памяти народа одна фраза из той речи отложилась как «Я устал, я ухожу». Хотя на самом деле звучала немного иначе: «Сегодня, в последний день уходящего века, я ухожу. Я сделал все, что мог».

Эффект Манделы является увлекательным примером тех причуд, которые могут происходить с памятью не только одного человека, но и целого сообщества. Иногда факты о нашем мозге оказываются интереснее выдумок об альтернативных вселенных.

Читайте также:

- На Марс полетим на ядерных кораблях? Говорим с экспертом о перспективах применения ядерной энергии

- Почему богатейшая страна мира оказалась уязвимой для COVID-19?

Хроника коронавируса в Беларуси и мире. Все главные новости и статьи здесь

Наш канал в Telegram. Присоединяйтесь!

Быстрая связь с редакцией: читайте паблик-чат Onliner и пишите нам в Viber!

Самые оперативные новости о пандемии и не только в новом сообществе Onliner в Viber. Подключайтесь

Перепечатка текста и фотографий Onliner без разрешения редакции запрещена. nak@onliner.by

Память — коварная вещь, ты удивишься, насколько неверно ты запомнил самые очевидные вещи и события.

30 июля 20225

Подробно про эффект Манделы мы уже рассказывали раньше. Если в двух словах, то сам Нельсон Мандела невиновен: фокусы сыграла социальная память человечества. Когда политический лидер ЮАР скончался 5 декабря 2013 года, миллионы людей во всем мире подивились этому факту: они прекрасно помнили, что он умер лет двадцать тому назад, и даже могли описать в подробностях, как прошли те похороны.

Pink Floyd и Сид Барретт

В июле 2006 эффект Манделы повторился в точности до запятой, и его пережили на себе даже меломаны-россияне. СМИ сообщили о смерти основателя группы Pink Floyd, в то время как многие граждане были уверены, что Сида Барретта убили наркотики бог знает когда. Дескать, именно поэтому Pink Floyd посвятили Барретту альбом Wish You Were Here («Жаль, что тебя здесь нет») в 1975 году.

Однако он был жив, хотя и нездоров. И даже заглядывал в студию во время записи Wish You Were Here, где его никто не узнал.

Бритни Спирс

Бритни Спирс

А не так давно Интернет столкнулся с другим субъектом ложной памяти из мира шоу-бизнеса. Нет, Бритни Спирс не умирала. Просто кому-то пришло в голову расспросить людей, как выглядела молодая певица в знаменитом клипе «Oops!…I Did It Again». Выяснилось, что коллективный разум запомнил ее с нацепленной микрофонной гарнитурой и в клетчатой юбке.

Достаточно посмотреть клип, чтобы понять: описанное даже не близко к истине. Микрофон Бритни постоянно цепляла на живых выступлениях, а воспоминания о школьном наряде пришли из более ранних клипов вроде «…Baby One More Time» и ее фоток в соцсетях. Смешались в кучу кони, люди…

Третья серия похождения Чебурашки — «Шапокляк»

Старуха Шапокляк

Бог с ней, с буржуйской Бритни, а что у нас творится? То же самое.

Российские граждане никогда бы не смогли поймать старуху Шапокляк, так как неверно составляют ее фоторобот. В приметах постоянно указывается наличие зонтика. Чертов зонтик есть даже у памятника Шапокляк в Саранске! Однако достаточно пересмотреть оригинальные мультфильмы про Чебурашку, чтобы увидеть: нет там никакого зонтика! Из аксессуаров у старушки лишь шляпа, сумочка и крыска Лариска.

Екатерина II

Екатерина II

Путают наши люди и собственную историю. Сколько раз за свою жизнь ты слышал байку о том, как Екатерина II продала Аляску американцам?

Так вот, она не при делах. Операцию по продаже земель Аляски провернул император Александр II через 70 лет после ее смерти.

Цитаты из кино

Не бережем мы память о кинематографе и мультиках. Даже вечную классику — «Зеленого слоника» — цитируем неверно. В основном, конечно, путаемся в нюансах, хотя все равно обидно. Примеров не счесть.

«Кавказская пленница, или Новые приключения Шурика». Все помнят фразочку «В моем доме попрошу не выражаться!», хотя в картина она звучит иначе: «В моем доме… не выражаться!»

«Жил-был пес». Душевный финал отмечен напутствием «Ну ты, это.. заходи, если что». Достаточно пересмотреть мультик, чтобы убедиться — на прощание волк бросает: «Спасибо… Ты заходи, если что».

«Звездные войны. Эпизод III: Месть ситхов». Растиражированная в мемах фраза «Ты должен был бороться со злом, а не примкнуть к нему!» отсутствует в сценарии. Вместо нее более пространный драматический монолог Оби-Вана: «Ты был Избранником! Предрекали, что ты уничтожишь ситхов, а не примкнешь к ним. Восстановишь равновесие Силы, а не ввергнешь ее во мрак!»

$

Сколько палочек у доллара? Да что там проверять — набери на клавиатуре и посмотри. Одна, всего одна. А не две, как мысленно рисует разум.

Оба начертания считаются верными, но две палочки — старомодная, пижонская стилизация, она не применяется в кодировках операционных систем и не рисуется на клавишах.

«Иван Грозный убивает своего сына»

«Иван Грозный и сын его Иван 16 ноября 1581 года» — именно так картина Ильи Репина называется во всех каталогах, художественных альбомах и на экспозициях. Хотя сюжет описан верно, не отрицаем.

Ильф и Петров

«Спасение утопающих — дело рук самих утопающих»

Если доковылять до книжного шкафа и взять зачитанный до дыр томик Ильи Ильфа и Евгения Петрова, обнаружится забавное.

Во-первых, упомянутые слова Остап Бендер никогда не произносил. Это был лозунг в клубе «Картонажник» города Васюки.

Во-вторых, слова выглядят совершенно иначе: «Дело помощи утопающим — дело рук самих утопающих» (намек на цитату Карла Маркса: «Освобождение рабочих должно быть делом самих рабочих»).

В оригинале, на наш взгляд, девиз нелепее и смешнее, зря коверкаем.

Кстати, тест: «Знаешь ли ты роман „12 стульев“ как свои 12 пальцев?»

Анна Ахматова

«Одна половина нашей страны сидела, а другая сажала»

Еще минутка русской литературы и поэзии, если ты еще не утомился.

Интеллигенция обожает цитировать Анну Ахматову, хотя не всегда обходится с ней аккуратно. В ее трудах и биографиях не найти такое высказывание. Существует похожее по смыслу: «Арестанты вернутся, и две России глянут друг другу в глаза: та, что сажала, и та, которую посадили».

«Мы вам покажем кузькину мать!»

Сей легенде мы посвятили отдельную статью-разоблачение: «Громкая история про то, как Хрущев стучал ботинком по столу в ООН».

Если в двух словах, то это неправда, слов таких Хрущев с трибуны не кричал и ботинком по ней не стучал. Байка склеена из трех отдельных эпизодов с нашим бывшим генсеком. Ботинок — отдельно, трибуна ООН — отдельно, а «кузькина мать» — из пламенного монолога в Москве, когда туда прибыла американская делегация.

«Денег нет, но вы держитесь»

Перенесемся теперь с этой политикой в наш век. Один из знаменитейших мемов Медведева «Денег нет, но вы держитесь» также по пути растерял свою точность. Сохранилось видео, и ты можешь убедиться в этом самостоятельно.

23 мая 2016 года в Крыму Медведев отвечал гневным пенсионерам следующей тирадой:

«Ее [индексации] нигде нет, мы вообще не принимали, просто денег нет сейчас. Найдем деньги — сделаем индексацию. Вы держитесь здесь. Вам всего доброго, хорошего настроения и здоровья!»

Кстати, в следующие два года пенсию героям репортажа так и не проиндексировали, если верить СМИ.

Кадр из кинофильма «Темный рыцарь»

Хит Леджер

Ну и напоследок опять поговорим об эффекте Манделы в его самой прямолинейной трактовке. Опять о смерти, да.

С самого момента трагической кончины Хита Леджера публика находится в уверенности, что он скончался на съемках «Темного рыцаря», чуть ли не в студии, от нервного переутомления и болеутоляющих.

Фокус памяти в том, что на момент смерти Хит Леджер уже месяц как снимался в следующем фильме — это был «Воображариум доктора Парнаса» режиссера Терри Гильяма. Он там присутствует во многих сценах, остальное за него доиграли Джонни Депп, Колин Фаррелл и Джуд Лоу.

Актер умер, когда отправился на выходные в свои апартаменты в Нью-Йорке 22 января 2008 года.

P.S. Предыдущую статью с другими спецэффектами Манделы можно увидеть здесь: «Что такое эффект Манделы и 10 лучших его примеров».

Путей распространения fakе facts — множество. Один из них получил название «эффект Манделы», суть которого заключается в следующем: масса людей начинает верить в событие, которого, на самом деле, не было, или же оно происходило, но совершенно иначе. Причины возникновения этого феномена до сих пор исследуются: есть как и психологические объяснения, так и мистические. Социальные сети только ускорили процесс распространения ложных фактов, а отсутствие способности критически воспринимать информацию усиливают этот эффект. Т&Р рассказывают о самых известных массовых заблуждениях в истории и объясняют, почему эффект Манделы возникает.

Что такое Эффект Манделы

Эффект Манделы заключается в совпадении воспоминаний у группы людей, противоречащих реальным фактам. Этот феномен стал известен в 2013 году, когда после смерти политического лидера ЮАР Нельсона Манделы массы людей начали утверждать, что он скончался в тюрьме в 80-ых годах 20 века, и некоторые даже помнят трансляцию его похорон по телевизору. На самом же деле политика освободили в 1990 году и он умер в 2013-ом. Тогда ввели термин «эффект Манделы», он до сих пор не имеет единого научного объяснения.

«Эффект Манделы» — это ошибочные воспоминания о событиях, которых не было, при этом люди ощущают сильные переживания и могут воспроизвести все детали

Бессознательное воспроизведение искаженных воспоминаний называется конфабуляцией — и это понятие не стоит путать с эффектом Манделы. Оно не обязательно связано с коллективными воспоминаниями и может возникнуть только у одного человека. «Как правило, все воспоминания реконструируются. Так что все зависит от того, из чего они созданы — правда, вымысел или смесь», — говорит профессор психологии Мэрианн Гарри из Университета Виктории.

В классическом понимании, введенном в психиатрию в 1866 году К.Л. Кальбаумом, конфабуляция — это один из видов парамнезий. Человек сообщает о вымышленных событиях, которых не было. В психиатрии это расстройство памяти, которое может прогрессировать в амнезию.

Клинический психолог Джон Пол Гаррисон отмечал следующее: «Некоторые воспоминания возникают спонтанно, когда мы читаем новости. И нам может показаться, когда мы воспринимаем определенную информацию, что мы владели ею всегда». Это один из способов непроизвольного формирования fake news. Поэтому возникает необходимость проверять не только поступающую нам информацию, но и то, какую информацию распространяем мы.

Британский психолог, первый профессор экспериментальной психологии в университете Кембриджа Фредерик Бартлетт описал процесс забывания и подмены воспоминаний в своей книге «Воспоминания» 1932 года. Барлетт прочитал участникам канадскую народную сказку «Война призраков». Он обнаружил, что слушатели опускали незнакомые детали и искажали информацию, чтобы сделать ее более понятной. Этот процесс называется «усилие за смыслом» (effort after meaning). Иными словами, люди склонны домысливать и скрашивать истории.

Почему это происходит

Теория «испорченного телефона»

Согласно одной из распространенных версий основной причиной Эффекта Манделы является склонность людей непроизвольно создавать fake facts. Людям свойственно передавать информацию в искаженном виде — преувеличивать, придумывать, приукрашивать для того, чтобы сделать свою историю эффектнее. Вскоре они забывают об этой лжи или начинают сами верить в нее. Здесь особое значение имеет сила самовнушения.

Теория перемещения в параллельных мирах

Это фантастическая теория, в которой существуют параллельные реальности, которые накладываются друг на друга. Так, события происходят в одно и то же время, из-за чего феномены искажаются. Когда эти реальности соприкасаются, происходит сбой.

Склонность к манипулированию

Эффекту Манделы подвержены те, у кого не развито критическое мышление и кто не привык перепроверять информацию. Такими людьми гораздо легче манипулировать и создавать ложную картину мира.

Влияние интернета

В диджитал-среде эффект Манделы только усиливается. Неправильные представления с невероятной скоростью набирают обороты. Люди даже создают сообщества, основанные на fake facts. Например, симуляции автокатастрофы принцессы Дианы 1997 года часто ошибочно принимают за реальные кадры. Таким образом, большинство эффектов Манделы связано с ошибками памяти и социальной дезинформацией. Тот факт, что многие неточности являются тривиальными, предполагает, что они являются результатом избирательного внимания или ошибочного вывода.

Исследование, где рассматривали более 100000 новостей, обсуждаемых в Твиттере, показало, что мистификации и слухи каждый раз побеждают правду примерно на 70% Причем ложь распространяли не боты, а реальные люди. Это представление о скорости, с которой fake facts распространяются в Интернете, может помочь объяснить эффект Манделы.

Например, Синдбад действительно снимался в других фильмах в 1990-х годах и появился на постере фильма «Гость» (это было похоже на джинна, что могло бы объяснить ассоциацию с фильмом «Шазам»). Синдбад также нарядился джинном на мероприятие, которое он проводил в 1990-х годах. Когда один человек упомянул этот фильм «Шазам» (вероятно, в Интернете), это изменило воспоминания других людей, которые пытались вспомнить фильмы, которые Синдбад снял в 1990-х годах. Интернет-сообщества распространяли эту информацию, пока она не стала «правдой».

Это объяснение подтверждает, что повторное воспоминание чего-либо укрепляет вашу уверенность в памяти

По мере того, как все больше и больше людей сообщали неверные детали, они включались в воспоминания других людей как факты и укрепляли их уверенность в собственной правоте.

Распространение и потребление фейковой информации может навредить как личности, так и всему обществу. Поэтому возникает острая необходимость в развитии критического мышления — оно позволяет скептически относиться к потребляемой информации и формировать более четкую картину мира.

Ася Казанцева, автор бестселлера «В интернете кто-то неправ», Corpus, 2016

«Информации в мире жутко много, и с каждым годом ее не просто становится больше, но и сам ее объем начинает увеличиваться быстрее… На самом деле единственный навык, на который имеет смысл делать ставку в такой ситуации, — это умение пользоваться поисковыми системами, находить нужную информацию и отличать авторитетные источники от низкокачественных. Чем меньше развит навык перепроверять информацию и разбираться, тем в большей степени человек склонен принимать на веру те концепции, которые ему случайно где-то попались, чем активно пользуются шарлатаны всех мастей».

In psychology, a false memory is a phenomenon where someone recalls something that did not happen or recalls it differently from the way it actually happened. Suggestibility, activation of associated information, the incorporation of misinformation, and source misattribution have been suggested to be several mechanisms underlying a variety of types of false memory.

Early work[edit]

The false memory phenomenon was initially investigated by psychological pioneers Pierre Janet and Sigmund Freud.[1]

Freud was fascinated with memory and all the ways it could be understood, used, and manipulated. Some claim that his studies have been quite influential in contemporary memory research, including the research into the field of false memory.[2] Pierre Janet was a French neurologist also credited with great contributions into memory research. Janet contributed to false memory through his ideas on dissociation and memory retrieval through hypnosis.[3]

In 1974, Elizabeth Loftus and John Palmer conducted a study[4] to investigate the effects of language on the development of false memory. The experiment involved two separate studies.

In the first study, 45 participants were randomly assigned to watch different videos of a car accident, in which separate videos had shown collisions at 20 mph (32 km/h), 30 mph (48 km/h) and 40 mph (64 km/h). Afterwards, participants filled out a survey. The survey asked the question, «About how fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?» The question always asked the same thing, except the verb used to describe the collision varied. Rather than «smashed», other verbs used included «bumped», «collided», «hit», or «contacted». Participants estimated collisions of all speeds to average between 35 mph (56 km/h) to just below 40 mph (64 km/h). If actual speed was the main factor in estimate, it could be assumed that participants would have lower estimates for lower speed collisions. Instead, the word being used to describe the collision seemed to better predict the estimate in speed rather than the speed itself.[4]

The second experiment also showed participants videos of a car accident, but the phrasing of the follow-up questionnaire was critical in participant responses. 150 participants were randomly assigned to three conditions. Those in the first condition were asked the same question as the first study using the verb «smashed». The second group was asked the same question as the first study, replacing «smashed» with «hit». The final group was not asked about the speed of the crashed cars. The researchers then asked the participants if they had seen any broken glass, knowing that there was no broken glass in the video. The responses to this question had shown that the difference between whether broken glass was recalled or not heavily depended on the verb used. A larger sum of participants in the «smashed» group declared that there was broken glass.

In this study, the first point brought up in discussion is that the words used to phrase a question can heavily influence the response given.[4] Second, the study indicates that the phrasing of a question can give expectations to previously ignored details, and therefore, a misconstruction of our memory recall. This indication supports false memory as an existing phenomenon.

Replications in different contexts (such as hockey games instead of car crashes) have shown that different scenarios require different framing effects to produce differing memories.[5]

Manifestations and types[edit]

Presuppositions and the misinformation effect[edit]

A presupposition is an implication through chosen language. If a person is asked, «What shade of blue was the wallet?», the questioner is, in translation, saying, «The wallet was blue. What shade was it?» The question’s phrasing provides the respondent with a supposed «fact». This presupposition creates one of two separate effects: true effect and false effect.

- In true effect, the implication was accurate: the wallet really was blue. That makes the respondent’s recall stronger, more readily available, and easier to extrapolate from. A respondent is more likely to remember a wallet as blue if the prompt said that it was blue, than if the prompt did not say so.

- In false effect, the implication was actually false: the wallet was not blue even though the question asked what shade of blue it was. This convinces the respondent of its truth (i.e., that the wallet was blue), which affects their memory. It can also alter responses to later questions to keep them consistent with the false implication.

Regardless of the effect being true or false, the respondent is attempting to conform to the supplied information, because they assume it to be true.[6]

Loftus’ meta-analysis on language manipulation studies suggested the misinformation effect taking hold on the recall process and products of the human memory. Even the smallest adjustment in a question, such as the article preceding the supposed memory, could alter the responses. For example, having asked someone if they had seen «the» stop sign, rather than «a» stop sign, provided the respondent with a presupposition that there was a stop sign in the scene. This presupposition increased the number of people responding that they had indeed seen the stop sign.[7]

The strength of verbs used in conversation or questioning also has a similar effect on the memory; for example – the words met, bumped, collided, crashed, or smashed would all cause people to remember a car accident at different levels of intensity. The words bumped, hit, grabbed, smacked, or groped would all paint a different picture of a person in the memory of an observer of sexual harassment if questioned about it later. The stronger the word, the more intense the recreation of the experience in the memory is. This in turn could trigger further false memories to better fit the memory created (change how a person looks or how fast a vehicle was moving before an accident).[8]

Word lists[edit]

One can trigger false memories by presenting subjects a continuous list of words. When subjects were presented with a second version of the list and asked if the words had appeared on the previous list, they found that the subjects did not recognize the list correctly. When the words on the two lists were semantically related to each other (e.g. sleep/bed), it was more likely that the subjects did not remember the first list correctly and created false memories (Anisfeld & Knapp, 1963).[9]

In 1998 Kathleen McDermott and Henry Roediger III conducted a similar experiment. Their goal was to intentionally trigger false memories through word lists. They presented subjects with lists to study all containing a large number of words that were semantically related to another word that was not found on the list. For example, if the word that they were trying to trigger was “river” the list would contain words such as flow, current, water, stream, bend, etc. They would then take the lists away and ask the subjects to recall the words on the lists. Almost every time the false memory was triggered and the subjects would end up recalling the target word as part of the list when it was never there. McDermott and Roediger even went as far as informing the subjects of the purpose and details of the experiment, and still the subjects would recall the non listed target word as part of the word list they had studied.[10]

Staged naturalistic events[edit]

Subjects were invited into an office and were told to wait there. After this they had to recall the inventory of the visited office. Subjects recognized objects consistent with the “office schema” although they did not appear in the office. (Brewer & Treyens, 1981)[9]

In another study, subjects were presented with a situation where they witnessed a staged robbery. Half of the subjects witnessed the robbery live while the other half watched a video of the robbery as it took place. After the event, they were sat down and asked to recall what had happened during the robbery. The results surprisingly showed that those who watched the video of the robbery actually recalled more information more accurately than those who were live on the scene. Still false memory presented itself in ways such as subjects seeing things that would fit in a crime scene that were not there, or not recalling things that did not fit the crime scene. This happened with both parties, displaying the idea of staged naturalistic events.[11]

Relational processing[edit]

Memory retrieval has been associated with the brain’s relational processing. In associating two events (in reference to false memory, say tying a testimony to a prior event), there are verbatim and gist representations. Verbatim matches to the individual occurrences (e.g., I do not like dogs because when I was five a chihuahua bit me) and gist matches to general inferences (e.g., I do not like dogs because they are mean). Keeping in line with the fuzzy-trace theory, which suggests false memories are stored in gist representations (which retrieves both true and false recall), Storbeck & Clore (2005) wanted to see how change in mood affected the retrieval of false memories. After using the measure of a word association tool called the Deese–Roediger–McDermott paradigm (DRM), the subjects’ moods were manipulated. Moods were either oriented towards being more positive, more negative, or were left untouched. Findings suggested that a more negative mood made critical details, stored in gist representation, more accessible.[12]

Mandela effect[edit]

The Bologna station clock in Italy, subject of a collective false memory

False memories can sometimes be shared by multiple people. This phenomenon was dubbed the «Mandela effect» by paranormal researcher Fiona Broome, who reported having vivid and detailed memories of news coverage of South African anti-apartheid leader Nelson Mandela dying in prison in the 1980s, despite Mandela actually dying in 2013 after serving as President of South Africa from 1994 to 1999. Broome reported that, since 2010, «perhaps thousands» of other people had written online about having the same memory of Mandela’s death and she speculated that the phenomenon could be evidence of parallel realities.[13][14]

One well-documented example of shared false memories comes from a 2010 study that examined people familiar with the clock at Bologna Centrale railway station, which was damaged in the Bologna massacre bombing in August 1980. In the study, 92% of respondents falsely remembered the clock had remained stopped since the bombing when, in fact, the clock was repaired shortly after the attack. Years later the clock was again stopped and set to the time of the bombing, in observance and commemoration of the bombing.[15]

Other examples include memories of the title of the Berenstain Bears children’s books being spelled «Berenstein»,[16][17] the logo of clothing brand Fruit of the Loom featuring a cornucopia,[18] Darth Vader telling Luke Skywalker, «Luke, I am your father» in the climax of The Empire Strikes Back (he actually says, «No, I am your father» in response to Skywalker’s assertion that Vader had killed his father),[19] Mr. Monopoly wearing a monocle,[20][21][22] and the existence of a 1990s movie titled Shazaam starring comedian Sinbad as a genie[23] (which Snopes suggests could be a confabulation of real memories, possibly including Sinbad wearing a genie-like costume during a TV marathon of Sinbad the Sailor movies in 1994,[24][25] the 1996 film Kazaam featuring a genie played by basketball star Shaquille O’Neal, and the 1960s animated genie-themed series Shazzan).[23][26][27] Likewise, false memories of Mandela’s death could be explained as the subject confabulating him with Steve Biko, another prominent South African anti-apartheid activist who died in prison in 1977.[28][29][30]

Scientists suggest that these are examples of false memories shaped by similar cognitive factors affecting multiple people and families,[17][31][32][33][34] such as social and cognitive reinforcement of incorrect memories[35][36] or false news reports and misleading photographs that influence the formation of memories based on them.[26][37][36][38]

Theories[edit]

Strength hypothesis[edit]

The strength hypothesis states that in strong situations (situations where one course of action is encouraged more than any other course of action due to the objective payoff) people are expected to demonstrate rational behavior, basing their behavior on the objective payoff.[39]

An example of this is the laws of a country. Most of its citizens, no matter how daring, will conform to these laws, because the objective payoff is personal safety.

Construction hypothesis[edit]

The construction hypothesis says that if a true piece of information being provided can alter a respondent’s answer, then so can a false piece of information.[40]

Construction hypothesis has major implications for explanations on the malleability of memory. Upon asking a respondent a question that provides a presupposition, the respondent will provide a recall in accordance with the presupposition (if accepted to exist in the first place). The respondent will recall the object or detail.[40]

Skeleton theory[edit]

Loftus developed what some refer to as «the skeleton theory» after having run an experiment involving 150 subjects from the University of Washington.[40] Loftus noticed that when a presupposition was one of false information it could only be explained by the construction hypothesis and not the strength hypothesis. Loftus then stated that a theory needed to be created for complex visual experiences where the construction hypothesis plays a significantly more important role than situational strength. She presented a diagram as a «skeleton» of this theory, which later became referred to by some as the skeleton theory.

The skeleton theory explains the procedure of how a memory is recalled, which is split into two categories: the acquisition processes and the retrieval processes.

The acquisition processes are in three separate steps. First, upon the original encounter, the observer selects a stimulus to focus on. The information that the observer can focus on compared to all of the information occurring in the situation as a whole, is very limited. In other words, a lot is going on around us and we only pick up on a small portion. This forces the observer to begin by selecting a focal point for focus. Second, our visual perception must be translated into statements and descriptions. The statements represent a collection of concepts and objects; they are the link between the event occurrence and the recall. Third, the perceptions are subject to any «external» information being provided before or after the interpretation. This subsequent set of information can reconstruct the memory.[40]

The retrieval processes come in two steps. First, the memory and imagery are regenerated. This perception is subject to what foci the observer has selected, along with the information provided before or after the observation. Second, the linking is initiated by a statement response, «painting a picture» to make sense of what was observed. This retrieval process results in either an accurate memory or a false memory.[40]

Natural factors for the formation of false memories[edit]

Individual differences[edit]

Greater creative imagination and dissociation are known to relate to false memory formation.[41] Creative imagination may lead to vivid details of imagined events. High dissociation may be associated with habitual use of lax response criteria for source decisions due to frequent interruption of attention or consciousness. Social desirability and false memory have also been examined.[42] Social desirability effects may depend on the level of perceived social pressure.[41]

Individuals who feel under greater social pressure may be more likely to acquiesce. Perceived pressure from an authority figure may lower individuals’ criteria for accepting a false event as true. The new individual difference factors include preexisting beliefs about memory, self-evaluation of one’s own memory abilities, trauma symptoms, and attachment styles. Regarding the first of these, metamemory beliefs about the malleability of memory, the nature of trauma memory, and the recoverability of lost memory may influence willingness to accept vague impressions or fragmentary images as recovered memories and thus, might affect the likelihood of accepting false memory.[43] For example, if someone believes that memory once encoded is permanent, and that visualization is an effective way to recover memories, the individual may endorse more liberal criteria for accepting a mental image as true memory. Also, individuals who report themselves as having better everyday memories may feel more compelled to come up with a memory when asked to do so. This may lead to more liberal criteria, making these individuals more susceptible to false memory.

There is some research that shows individual differences in false memory susceptibility are not always large (even on variables that have previously shown differences—such as creative imagination or dissociation[44]), that there appears to be no false memory trait,[45][46] and that even those who have highly superior memory are susceptible to false memories.[47]

Trauma[edit]

A history of trauma is relevant to the issue of false memory. It has been proposed that people with a trauma history or trauma symptoms may be particularly vulnerable to memory deficits, including source-monitoring failures.[48]

Possible associations between attachment styles and reports of false childhood memories were also of interest. Adult attachment styles have been related to memories of early childhood events, suggesting that the encoding or retrieval of such memories may activate the attachment system. It is more difficult for avoidant adults to access negative emotional experiences from childhood, whereas ambivalent adults access these kinds of experiences easily.[49] Consistent with attachment theory, adults with avoidant attachment styles, like their child counterparts, may attempt to suppress physiological and emotional reactions to activation of the attachment system. Significant associations between parental attachment and children’s suggestibility exist. These data, however, do not directly address the issue of whether adults’ or their parents’ attachment styles are related to false childhood memories. Such data nevertheless suggest that greater attachment avoidance may be associated with a stronger tendency to form false memories of childhood.

Sleep deprivation[edit]

Sleep deprivation can also affect the possibility of falsely encoding a memory. In two experiments, participants studied DRM lists (lists of words [e.g., bed, rest, awake, tired] that are semantically associated with a non-presented word) before a night of either sleep or sleep deprivation; testing took place the following day. One study showed higher rates of false recognition in sleep-deprived participants, compared with rested participants.[50]

Sleep deprivation can increase the risk of developing false memories. Specifically, sleep deprivation increased false memories in a misinformation task when participants in a study were sleep deprived during event encoding, but did not have a significant effect when the deprivation occurred after event encoding.[51]

False memory syndrome[edit]

False memory syndrome is defined as false memory being a prevalent part of one’s life in which it affects the person’s mentality and day-to-day life. False memory syndrome differs from false memory in that the syndrome is heavily influential in the orientation of a person’s life, while false memory can occur without this significant effect. The syndrome takes effect because the person believes the influential memory to be true.[52] However, its research is controversial and the syndrome is not included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. False memory is an important part of psychological research because of the ties it has to a large number of mental disorders, such as PTSD.[53] False memory can be declared a syndrome when recall of a false or inaccurate memory takes great effect on a person’s life. Such a false memory can completely alter the orientation of one’s personality and lifestyle.[1][54]

Psychiatry[edit]

Therapists who subscribe to recovered memory theory point to a wide variety of common problems, ranging from eating disorders to sleeplessness, as evidence of repressed memories of sexual abuse.[55] Psychotherapists tried to reveal “repressed memories” in mental therapy patients through “hypnosis, guided imagery, dream interpretation and narco-analysis”. The reasoning was that if abuse couldn’t be remembered, then it needed to be recovered by the therapist. The legal phenomena developed in the 1980s, with civil suits alleging child sexual abuse on the basis of “memories” recovered during psychotherapy. The term “repressed memory therapy” gained momentum and with it social stigma surrounded those accused of abuse. The “therapy” led to other psychological disorders in persons whose memories were recovered.[medical citation needed]

Memories recovered through therapy have become more difficult to distinguish between simply being repressed or having existed in the first place.[citation needed]

Therapists have used strategies such as hypnotherapy, repeated questioning, and bibliotherapy. These strategies may provoke the recovery of nonexistent events or inaccurate memories.[56][57][58] A recent report indicates that similar strategies may have produced false memories in several therapies in the century before the modern controversy on the topic which took place in the 1980s and 1990s.[59]

According to Loftus, there are different possibilities to create false therapy-induced memory. One is the unintentional suggestions of therapists. For example, a therapist might tell their client that, on the basis of their symptoms, it is quite likely that they had been abused as a child. Once this «diagnosis» is made, the therapist sometimes urges the patient to pursue the recalcitrant memories. It is a problem resulting from the fact that people create their own social reality with external information.[60]

The «lost-in-the-mall» technique is another recovery strategy.[clarification needed] This is essentially a repeated suggestion pattern. The person whose memory is to be recovered is persistently said to have gone through an experience even if it may have not happened. This strategy can cause the person to recall the event as having occurred, despite its falsehood.[61]

Hypnosis[edit]

Laurence and Perry conducted a study testing the ability to induce memory recall through hypnosis. Subjects were put into a hypnotic state and later woken up. Observers suggested that the subjects were woken up by a loud noise. Nearly half of the subjects being tested concluded that this was true, despite it being false. However, by therapeutically altering the subject’s state, they may have been led to believe that what they were being told was true.[62] Because of this, the respondent has a false recall.

A 1989 study focusing on hypnotizability and false memory separated accurate and inaccurate memories recalled. In open-ended question formation, 11.5% of subjects recalled the false event suggested by observers. In a multiple-choice format, no participants claimed the false event had happened. This result led to the conclusion that hypnotic suggestions produce shifts in focus, awareness, and attention. Despite this, subjects do not mix fantasy up with reality.[1]

Effects on society[edit]

Legal cases[edit]

Therapy-induced memory recovery has made frequent appearances in legal cases, particularly those regarding sexual abuse.[63] Therapists can often aid in creating a false memory in a victim’s mind, intentionally or unintentionally. They will associate a patient’s behavior with the fact that they have been a victim of sexual abuse, thus helping the memory occur. They use memory enhancement techniques such as hypnosis dream analysis to extract memories of sexual abuse from victims. In Ramona v. Isabella, two therapists wrongly prompted a recall that their patient, Holly Ramona, had been sexually abused by her father. It was suggested that the therapist, Isabella, had implanted one of the sexual abuse memories in Ramona after use of the hypnotic drug sodium amytal. After a nearly unanimous decision, Isabella had been declared negligent towards Holly Ramona. This 1994 legal issue played a massive role in shedding light on the possibility of false memories’ occurrences. [64]

In another legal case where false memories were used, they helped a man to be acquitted of his charges. Joseph Pacely had been accused of breaking into a woman’s home with the intent to sexually assault her. The woman had given her description of the assailant to police shortly after the crime had happened. During the trial, memory researcher Elizabeth Loftus testified that memory is fallible and there were many emotions that played a part in the woman’s description given to police. Loftus has published many studies consistent with her testimony.[40][65][66] These studies suggest that memories can easily be changed around and sometimes eyewitness testimonies are not as reliable as many believe.

Another notable case is Maxine Berry. Maxine grew up in the custody of her mother, who opposed the father having contact with her (Berry & Berry, 2001). When the father expressed his desire to attend his daughter’s high school graduation, the mother enrolled Maxine in therapy, ostensibly to deal with the stress of seeing her father. The therapist pressed Maxine to recover memories of sex abuse by her father. Maxine broke down under the pressure and had to be psychiatrically hospitalized. She underwent tubal ligation, so she would not have children and repeat the cycle of abuse. With the support of her husband and primary care physician, Maxine eventually realized that her memories were false and filed a suit for malpractice. The suit brought to light the mother’s manipulation of mental health professionals to convince Maxine that she had been sexually abused by her father. In February 1997 Maxine Berry sued her therapists[67] and clinic that treated her from 1992 to 1995 and, she says, made her falsely believe she had been sexually and physically abused as a child when no such abuse ever occurred. The lawsuit, filed in February 1997 in Minnehaha Co. Circuit Court South Dakota, states that therapist Lynda O’Connor-Davis had an improper relationship with Berry, both during and after her treatment. The suit also names psychologist Vail Williams, psychiatrist Dr. William Fuller and Charter Hospital and Charter Counseling Center as defendants. Berry and her husband settled out of court[68]

Although there have been many legal cases in which false memory appears to have been a factor, this does not ease the process of distinguishing between false memory and real recall. Sound therapeutic strategy can help this differentiation, by either avoiding known controversial strategies or to disclosing controversy to a subject.[56][1][69]

Harold Merskey published a paper on the ethical issues of recovered-memory therapy.[69] He suggests that if a patient had pre-existing severe issues in their life, it is likely that «deterioration» will occur to a relatively severe extent upon memory recall. This deterioration is a physical parallel to the emotional trauma being surfaced. There may be tears, writhing, or many other forms of physical disturbance. The occurrence of physical deterioration in memory recall coming from a patient with relatively minor issues prior to therapy could be an indication of the recalled memory’s potential falsehood.[69]

Children[edit]

False memory is often considered for trauma victims[70] including those of childhood sexual abuse.[71][72][56][73]

If a child experienced abuse, it is not typical for them to disclose the details of the event when confronted in an open-ended manner.[74] Trying to indirectly prompt a memory recall can lead to the conflict of source attribution, as if repeatedly questioned the child might try to recall a memory to satisfy a question. The stress being put on the child can make recovering an accurate memory more difficult.[71] Some people hypothesize that as the child continuously attempts to remember a memory, they are building a larger file of sources that the memory could be derived from, potentially including sources other than genuine memories. Children that have never been abused but undergo similar response-eliciting techniques can disclose events that never occurred.[74]

One of children’s most notable setbacks in memory recall is source misattribution. Source misattribution is the flaw in deciphering between potential origins of a memory. The source could come from an actual occurring perception, or it can come from an induced and imagined event. Younger children, preschoolers in particular, find it more difficult to discriminate between the two.[75] Lindsay & Johnson (1987) concluded that even children approaching adolescence struggle with this, as well as recalling an existent memory as a witness. Children are significantly more likely to confuse a source between being invented or existent.[76]

Shyamalan, Lamb and Sheldrick (1995) partially re-created a study that involved attempted memory implanting in children. The study comprised a series of interviews concerning a medical procedure that the children may have undergone. The data was scored so that if a child made one false affirmation during the interview, the child was classified as inaccurate. When the medical procedure was described in detail, «only 13% of the children answered ‘yes’ to the question ‘Did you ever have this procedure?'». As to the success of implantation with false ‘memories’, the children «assented to the question for a variety of reasons, a false memory being only one of them. In sum, it is possible that no false memories have been created in children in implanted-memory studies».[77]

Ethics and public opinion[edit]

A 2016 study surveyed the public’s attitude regarding the ethics of planting false memories as an attempt to influence healthy behavior. People were most concerned with the consequences, with 37% saying it was overly manipulative, potentially harmful or traumatic. Their reasons against are that the ends do not justify the means (32%), potential for abuse (14%), lack of consent (10%), practical doubts (8%), better alternative (7%), and free will (3%). Of those who thought implanting false memories would be acceptable, 36% believed the end justified the means, with other reasons being increasing treatment options (6%), people need support (6%), no harm would be done (6%), and it’s no worse than alternatives (5%).[78]

Potential benefits[edit]

Several possible benefits associated with false memory arrive from fuzzy-trace theory and gist memory. Valerie F. Reyna, who coined the terms as an explanation for the DRM paradigm, explains that her findings indicate that reliance on prior knowledge from gist memory can help individuals make safer, well informed choices in terms of risk taking.[79] Other positive traits associated with false memory indicate that individuals have superior organizational processes, heightened creativity, and prime solutions for insight based problems. All of these things indicate that false memories are adaptive and functional.[80] False memories tied to familiar concepts can also potentially aid in future problem solving in a related topic, especially when related to survival.[81]

See also[edit]

- Source-monitoring error, an effect in which memories are incorrectly attributed to different experiences than the ones that caused them.

- Déjà vu, the feeling that one has lived through the present situation before.

- Jamais vu, the feeling of unfamiliarity with recognised memories.

- Cryptomnesia, a memory that is not recognised as such.

- Lost in the mall technique, a memory implantation technique used to demonstrate that false memories can be implanted through suggestions made to experimental subjects in which the subject is told that an older relative was present at the time.

- Memory conformity

- Inception, a science fiction film dealing with the concept of implanting ideas in sleeping individuals.

- Recursion, a science fiction novel by Blake Crouch which includes topics of false memory.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Gleaves, David H.; Smith, Steven M.; Butler, Lisa D.; Spiegel, David (2006). «False and Recovered Memories in the Laboratory and Clinic: A Review of Experimental and Clinical Evidence». Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 11: 3–28. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bph055.

- ^ Knafo, D. (2009). Freud’s memory erased. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 26(2), 171–190. doi:10.1037/a0015557

- ^ Zongwill, O. L. (2019). Memory abnormality. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/science/memory-abnormality Archived 30 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Loftus, Elizabeth F.; Palmer, John C. (1974). «Reconstruction of automobile destruction: An example of the interaction between language and memory». Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 13 (5): 585–589. doi:10.1016/s0022-5371(74)80011-3.

- ^ Goldschmied, Nadav; Sheptock, Mark; Kim, Kacey; Galily, Yair (2017). «Appraising Loftus and Palmer (1974) Post-Event Information versus Concurrent Commentary in the Context of Sport». Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 70 (11): 2347–2356. doi:10.1080/17470218.2016.1237980. PMID 27643483. S2CID 205924157.

- ^ Beaver, David I. (1 April 2011). «Presupposition». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 1 May 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ^ Loftus, Elizabeth, F. (1975). «Reconstructing memory: The incredible eyewitness». Jurimetrics Journal. 15 (3): 188–193.

- ^ Malpass, R. S. (2004). Misinformation effect. Encyclopedia of Applied Psychology. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/misinformation-effect Archived 23 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Lampinen, James M.; Neuschatz, Jeffrey S.; Payne, David G. (1997). «Memory illusions and consciousness: Examining the phenomenology of true and false memories». Current Psychology. 16 (3–4): 181–224. doi:10.1007/s12144-997-1000-5. S2CID 144603817.

- ^ McDermott, K. B., & Roediger III, H. L. (1998). Attempting to avoid illusory memories: Robust false recognition of associates persists under conditions of explicit warnings and immediate testing. Journal of Memory and Language, 39(3), 508-520.

- ^ Ihlebæk, C., Løve, T., Erik Eilertsen, D., & Magnussen, S. (2003). Memory for a staged criminal event witnessed live and on video. Memory, 11(3), 319-327.

- ^ Storbeck, J.; Clore, G.L. (2005). «With Sadness Comes Accuracy; with Happiness, False Memory: Mood and the False Memory Effect». Psychological Science. 16 (10): 785–791. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01615.x. PMID 16181441. S2CID 16608445.

- ^ «Two cognitive psychologists explain the mystery of the ‘Mandela effect’«. The Independent. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ «How a Wild Theory About Nelson Mandela Proves the Existence of Parallel Universes». Big Think. 27 December 2017. Archived from the original on 11 August 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ «Collective representation elicit widespread individual false memories». ResearchGate. Archived from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ Emery, David (24 July 2016). «The Mandela Effect». Snopes. Archived from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ a b «Are you living in an alternate reality? Welcome to the wacky world of the ‘Mandela Effect’«. The Telegraph. London. 20 September 2016. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ Tweed, Carter (29 May 2017). «Did the Fruit of the Loom logo have a cornucopia?». Alternate Memories. Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ Palma, Bethania (20 July 2022). «No, Darth Vader Didn’t Actually Say ‘Luke, I Am Your Father’«. Snopes. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ Prasad, Deepasri; Bainbridge, Wilma A. (2022). «The Visual Mandela Effect as Evidence for Shared and Specific False Memories Across People». Psychological Science. 33 (12): 1971–1988. doi:10.1177/09567976221108944. ISSN 1467-9280. PMID 36219739. S2CID 241793849. Archived from the original on 2023.

- ^ «The Mandela Effect: Poll shows most Americans misremember Darth Vader quote, Monopoly logo». ABC7 Los Angeles. 5 September 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ Jessica Lyn Bannon, opinion contributor (16 January 2022). «Rich Uncle Pennybags didn’t wear a monocle — and other false memories». The Hill. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ a b Tait, Amelia (21 December 2016). «The movie that doesn’t exist and the Redditors who think it does». New Statesman. London. Archived from the original on 26 March 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ 28 December 1994, on the cable channel TNT; the marathon featured movies including Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977).

- ^ Evon, Dan (28 December 2016). «Did Sinbad Play a Genie in the 1990s Movie ‘Shazaam’?». Snopes. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ a b Aamodt, Caitlin (16 February 2016). «Collective False Memories: What’s Behind the ‘Mandela Effect’?». Discover Magazine. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ Hankins, Sarah (21 March 2017). «If You Remember ‘Shazaam’, The Movie That Doesn’t Exist, You Aren’t Alone». The Odyssey Online. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ Drinkwater, Ken; Dagnall, Neil. «The ‘Mandela effect’ and the science of false memories». The Conversation. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ «Critically Thinking About the Mandela Effect | Psychology Today». www.psychologytoday.com. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ Dimou, Eleni (30 December 2021). «The Science Behind the Reality-Bending Mandela Effect». Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ «Collective False Memories: What’s Behind the ‘Mandela Effect’?». The Crux. 16 February 2017. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ^ Fernando, Gavin (8 November 2016). «Does this picture look a bit off to you?». News.com.au. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ^ Cooke, Henry (12 October 2017). «NZ and the ‘Mandala Effect’: Meet the folks who remember New Zealand being in a different place». Stuff. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ^ Gabbert, Elisa (9 February 2017). «On a Grandma’s House and the Unknowability of the Past». Pacific Standard. Archived from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ Brown, Adam D.; Kouri, Nicole; Hirst, William (23 July 2012). «Memory’s Malleability: Its Role in Shaping Collective Memory and Social Identity». Frontiers in Psychology. 3: 257. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00257. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 3402138. PMID 22837750.

- ^ a b «Can groups of people «remember» something that didn’t happen?». Hopes&Fears. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ «False Memories in the News: Are Pictures Worth MORE Than 1,000 Words?». CogBlog – A Cognitive Psychology Blog. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ Resnick, Brian (20 April 2018). «We’re underestimating the mind-warping potential of fake video». Vox. Archived from the original on 15 March 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ Lozano, J. H. (2018). The situational strength hypothesis and the measurement of personality. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 9(1), 70-79. doi:10.1177/1948550617699256

- ^ a b c d e f Loftus, Elizabeth F. (1975). «Leading questions and the eyewitness report». Cognitive Psychology. 7 (4): 560–572. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(75)90023-7. S2CID 16731808.

- ^ a b Ost, James; Foster, Samantha; Costall, Alan; Bull, Ray (2005). «False reports of childhood events in appropriate interviews». Memory. 13 (7): 700–710. doi:10.1080/09658210444000340. PMID 16191820. S2CID 33621927. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ Paddock, John R.; Terranova, Sophia; Kwok, Rosie; Halpern, David V. (2000). «When Knowing Becomes Remembering: Individual Differences in Susceptibility to Suggestion». The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 161 (4): 453–468. doi:10.1080/00221320009596724. PMID 11117101. S2CID 34798568.

- ^ Ghetti, Simona; Bunge, Silvia A. (2012). «Neural changes underlying the development of episodic memory during middle childhood». Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2 (4): 381–395. doi:10.1016/j.dcn.2012.05.002. PMC 3545705. PMID 22770728.

- ^ Patihis, L.; Frenda, S.; Loftus, E.F. (2018). «False memory tasks do not reliably predict other false memories». Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice. 5 (2): 140–160. doi:10.1037/cns0000147. S2CID 150202452. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ Bernstein, D.M.; Scoboria, A.; Desjarlais, L.; Soucie, K. (2018). ««False memory» is a linguistic convenience». Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice. 5 (2): 161–179. doi:10.1037/cns0000148. S2CID 173992031.

- ^ Patihis, L. (2018). «Why there is no false memory trait and why everyone is susceptible to memory distortions: The dual encoding interference hypothesis». Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice. 5 (2): 180–184. doi:10.1037/cns0000143. S2CID 149974111. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ Patihis, L.; Frenda, S.J.; LePort, A.K.R.; Petersen, N.; Nichols, R.M.; Stark, C.E.L.; McGaugh, J.L.; Loftus, E.F. (2013). «False memories in highly superior autobiographical memory individuals». PNAS. 110 (52): 20947–20952. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11020947P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1314373110. PMC 3876244. PMID 24248358.

- ^ Bremner, J. Douglas; Shobe, Katharine Krause; Kihlstrom, John F. (2000). «False Memories in Women with Self-Reported Childhood Sexual Abuse: An Empirical Study». Psychological Science. 11 (4): 333–337. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00266. PMID 11273395. S2CID 6113518.

- ^ Edelstein, Robin S. (2006). «Attachment and emotional memory: Investigating the source and extent of avoidant memory impairments». Emotion. 6 (2): 340–345. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.498.181. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.6.2.340. PMID 16768567.

- ^ Diekelmann, Susanne; Landolt, Hans-Peter; Lahl, Olaf; Born, Jan; Wagner, Ullrich (23 October 2008). «Sleep Loss Produces False Memories». PLOS ONE. 3 (10): e3512. Bibcode:2008PLoSO…3.3512D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003512. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2567433. PMID 18946511.

- ^ Frenda, Steven J.; Patihis, Lawrence; Loftus, Elizabeth F.; Lewis, Holly C.; Fenn, Kimberly M. (2014). «Sleep Deprivation and False Memories». Psychological Science. 25 (9): 1674–1681. doi:10.1177/0956797614534694. PMID 25031301. S2CID 339864. Archived from the original on 18 October 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ Kaplan, Robert; Manicavasagar, Vijaya (2001). «Is there a false memory syndrome? A review of three cases». Comprehensive Psychiatry. 42 (4): 342–348. doi:10.1053/comp.2001.24588. PMID 11936143.

- ^ Friedman, Matthew J. (1996). «PTSD diagnosis and treatment for mental health clinicians». Community Mental Health Journal. 32 (2): 173–189. doi:10.1007/bf02249755. PMID 8777873. S2CID 143532335.

- ^ Kihlstrom, J.F. (1998). Exhumed memory Archived 1 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine. In S.J. Lynn & K.M. McConkey (Eds.), Truth in memory, (pp. 3-31). New York: Guilford.

- ^ Mertz, Elizabeth; Bowman, Cynthia (1998), The Clinical Corner: Third-Party Liability in Repressed Memory Cases: Recent Legal Developments, doi:10.1037/e300392004-003

- ^ a b c Ware, Robert C. (1995). «Scylla and Charybdis». Journal of Analytical Psychology. 40 (1): 5–22. doi:10.1111/j.1465-5922.1995.00005.x. PMID 7868381.

- ^ McElroy, Susan L.; Keck, Paul E. (1995). «Recovered Memory Therapy: False Memory Syndrome and Other Complications». Psychiatric Annals. 25 (12): 731–735. doi:10.3928/0048-5713-19951201-09.

- ^ Gold, Steven N. (1997). «False memory syndrome: A false dichotomy between science and practice». American Psychologist. 52 (9): 988–989. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.52.9.988.

- ^ Patihis, Lawrence; Younes Burton, Helena J. (2015). «False memories in therapy and hypnosis before 1980». Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2 (2): 153–169. doi:10.1037/cns0000044.

- ^ Loftus, Elizabeth F. (1993). «The reality of repressed memories». American Psychologist. 48 (5): 518–537. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.48.5.518. PMID 8507050.

- ^ Loftus, E.F. (2005). «Planting misinformation in the human mind: A 30-year investigation of the malleability of memory». Learning & Memory. 12 (4): 361–366. doi:10.1101/lm.94705. PMID 16027179.

- ^ Laurence, Jean-Roch; Perry, Campbell (1983). «Hypnotically Created Memory among Highly Hypnotizable Subjects». Science. 222 (4623): 523–524. Bibcode:1983Sci…222..523L. doi:10.1126/science.6623094. PMID 6623094.

- ^ DePrince, Anne P.; Brown, Laura S.; Cheit, Ross E.; Freyd, Jennifer J.; Gold, Steven N.; Pezdek, Kathy; Quina, Kathryn (18 October 2011), «Motivated Forgetting and Misremembering: Perspectives from Betrayal Trauma Theory», True and False Recovered Memories, New York: Springer, vol. 58, pp. 193–242, doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-1195-6_7, ISBN 978-1-4614-1194-9, PMID 22303768

- ^ «Spectral Evidence — The Ramona Case: Incest, Memory, and Truth on Trial in Napa Valley». Women’s Rights Law Reporter. 20: 49. 1998–1999. Archived from the original on 20 November 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ Powers, Peter A.; Andriks, Joyce L.; Loftus, Elizabeth F. (1979). «Eyewitness accounts of females and males» (PDF). Journal of Applied Psychology. 64 (3): 339–347. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.64.3.339. S2CID 31305222.

- ^ Loftus, Elizabeth F.; Greene, Edith (1980). «Warning: Even memory for faces may be contagious». Law and Human Behavior. 4 (4): 323–334. doi:10.1007/BF01040624. S2CID 146947540.

- ^ «FMSF Newsletter Archive». False Memory Syndrome Foundation. 1 April 1997. Archived from the original on 9 October 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ «Clipped from Argus-Leader». Argus-Leader. 27 February 1997. p. 27. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Merskey, Harold (1996). «Ethical Issues in the Search for Repressed Memories». American Journal of Psychotherapy. 50 (3): 323–335. doi:10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1996.50.3.323. PMID 8886232.

- ^ Carey, Benedict; Hoffman, Jan (25 September 2018). «They Say Sexual Assault, Kavanaugh Says It Never Happened: Sifting Truth From Memory». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

Memory, by its nature and necessity, is selective, its details subject to revision and dissipation. … «Recollection is always a reconstruction, to some extent — it’s not a videotape that preserves every detail,» said Richard J. McNally, a professor of psychology at Harvard University and the author of Remembering Trauma. «The details are often filled in later, or dismissed, and guessing may become part of the memory.»…Recalling an event draws on some of same areas of the brain that recorded it; in essence, to remember is to relive. Every time the mind summons the encoded experience, it can add details, subtract others and even alter the tone and point of the story. That reassembly, in turn, is freshly stored again, so that the next time it comes to mind it contains those edits. Using memory changes memory, as cognitive scientists say. For a victim, often the only stable elements are emotions and the tunnel-vision details: the dress she wore, the hand over her mouth

- ^ a b Bremner, J.D.; Krystal, J.H.; Charney, D.S.; Southwick, S.M. (1996). «Neural Mechanisms in dissociative amnesia for childhood abuse: Relevance to the current controversy surrounding the «false memory syndrome»«. American Journal of Psychiatry. 153 (7): 71–82. doi:10.1176/ajp.153.7.71. PMID 8659644.

- ^ Davis, Joseph E. (2005). «Victim Narratives and Victim Selves: False Memory Syndrome and the Power of Accounts». Social Problems. 52 (4): 529–548. doi:10.1525/sp.2005.52.4.529.

- ^ Christianson, Sven-åke; Loftus, Elizabeth F. (1987). «Memory for traumatic events». Applied Cognitive Psychology. 1 (4): 225–239. doi:10.1002/acp.2350010402.

- ^ a b Ceci, Stephen J.; Loftus, Elizabeth F.; Leichtman, Michelle D.; Bruck, Maggie (1994). «The Possible Role of Source Misattributions in the Creation of False Beliefs Among Preschoolers». International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 42 (4): 304–320. doi:10.1080/00207149408409361. PMID 7960288.

- ^ Foley, Mary Ann; Johnson, Marcia K. (1985). «Confusions between Memories for Performed and Imagined Actions: A Developmental Comparison». Child Development. 56 (5): 1145–55. doi:10.2307/1130229. JSTOR 1130229. PMID 4053736.

- ^ Lindsay, D. Stephen; Johnson, Marcia K.; Kwon, Paul (1991). «Developmental changes in memory source monitoring». Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 52 (3): 297–318. doi:10.1016/0022-0965(91)90065-z. PMID 1770330.

- ^ Goodman, Gail S; Quas, Jodi D; Redlich, Allison A (1998). «The ethics of conducting ‘false memory’ research with children: a reply to Herrmann and Yoder» (PDF). Applied Cognitive Psychology. 12 (3): 207–217. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0720(199806)12:3<207::AID-ACP523>3.0.CO;2-T. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Nash, Robert A.; Berkowitz, Shari R.; Roche, Simon (2016). «Public Attitudes on the Ethics of Deceptively Planting False Memories to Motivate Healthy Behavior». Applied Cognitive Psychology. 30 (6): 885–897. doi:10.1002/acp.3274. PMC 5215583. PMID 28111495.

- ^ Dodgson, Lindsay. Our brains sometimes create ‘false memories’ — but science suggests we could be better off this way Archived 6 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine” Business Insider.

- ^ “Future Thinking and False Memories.” Psychology Today, Sussex Publishers, www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/time-travelling-apollo/201607/future-thinking-and-false-memories.

- ^ Jarrett, Christian (23 September 2013). «False memories have an upside». British Psychological Society. Archived from the original on 21 November 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

Further reading[edit]

- Bjorklund, D. F. (2014). False-memory Creation in Children and Adults: Theory, Research, and Implications. Psychology Press. ISBN 9781138003224

- Conway, M. A. (1997). Recovered Memories and False Memories. Oxford University Press.

- French, C (2003). «Fantastic Memories: The Relevance of Research into Eyewitness Testimony and False Memories for Reports of Anomalous Experiences» (PDF). Journal of Consciousness Studies. 10: 153–174. ISSN 1355-8250. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Roediger, Henry L.; Marsh, Elizabeth J. (2009). «False memory». Scholarpedia. 4 (8): 3858. Bibcode:2009SchpJ…4.3858I. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.3858.

- Schacter, D. L; Curran, T. (1995). «The Cognitive Neuroscience of False Memories». Psychiatric Annals. 25 (12): 727–731. doi:10.3928/0048-5713-19951201-08.

This audio file was created from a revision of this article dated 30 July 2019, and does not reflect subsequent edits.

In psychology, a false memory is a phenomenon where someone recalls something that did not happen or recalls it differently from the way it actually happened. Suggestibility, activation of associated information, the incorporation of misinformation, and source misattribution have been suggested to be several mechanisms underlying a variety of types of false memory.

Early work[edit]

The false memory phenomenon was initially investigated by psychological pioneers Pierre Janet and Sigmund Freud.[1]

Freud was fascinated with memory and all the ways it could be understood, used, and manipulated. Some claim that his studies have been quite influential in contemporary memory research, including the research into the field of false memory.[2] Pierre Janet was a French neurologist also credited with great contributions into memory research. Janet contributed to false memory through his ideas on dissociation and memory retrieval through hypnosis.[3]

In 1974, Elizabeth Loftus and John Palmer conducted a study[4] to investigate the effects of language on the development of false memory. The experiment involved two separate studies.

In the first study, 45 participants were randomly assigned to watch different videos of a car accident, in which separate videos had shown collisions at 20 mph (32 km/h), 30 mph (48 km/h) and 40 mph (64 km/h). Afterwards, participants filled out a survey. The survey asked the question, «About how fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?» The question always asked the same thing, except the verb used to describe the collision varied. Rather than «smashed», other verbs used included «bumped», «collided», «hit», or «contacted». Participants estimated collisions of all speeds to average between 35 mph (56 km/h) to just below 40 mph (64 km/h). If actual speed was the main factor in estimate, it could be assumed that participants would have lower estimates for lower speed collisions. Instead, the word being used to describe the collision seemed to better predict the estimate in speed rather than the speed itself.[4]

The second experiment also showed participants videos of a car accident, but the phrasing of the follow-up questionnaire was critical in participant responses. 150 participants were randomly assigned to three conditions. Those in the first condition were asked the same question as the first study using the verb «smashed». The second group was asked the same question as the first study, replacing «smashed» with «hit». The final group was not asked about the speed of the crashed cars. The researchers then asked the participants if they had seen any broken glass, knowing that there was no broken glass in the video. The responses to this question had shown that the difference between whether broken glass was recalled or not heavily depended on the verb used. A larger sum of participants in the «smashed» group declared that there was broken glass.

In this study, the first point brought up in discussion is that the words used to phrase a question can heavily influence the response given.[4] Second, the study indicates that the phrasing of a question can give expectations to previously ignored details, and therefore, a misconstruction of our memory recall. This indication supports false memory as an existing phenomenon.

Replications in different contexts (such as hockey games instead of car crashes) have shown that different scenarios require different framing effects to produce differing memories.[5]

Manifestations and types[edit]

Presuppositions and the misinformation effect[edit]

A presupposition is an implication through chosen language. If a person is asked, «What shade of blue was the wallet?», the questioner is, in translation, saying, «The wallet was blue. What shade was it?» The question’s phrasing provides the respondent with a supposed «fact». This presupposition creates one of two separate effects: true effect and false effect.

- In true effect, the implication was accurate: the wallet really was blue. That makes the respondent’s recall stronger, more readily available, and easier to extrapolate from. A respondent is more likely to remember a wallet as blue if the prompt said that it was blue, than if the prompt did not say so.

- In false effect, the implication was actually false: the wallet was not blue even though the question asked what shade of blue it was. This convinces the respondent of its truth (i.e., that the wallet was blue), which affects their memory. It can also alter responses to later questions to keep them consistent with the false implication.

Regardless of the effect being true or false, the respondent is attempting to conform to the supplied information, because they assume it to be true.[6]