In linguistics, according to J. Richard et al., (2002), an error is the use of a word, speech act or grammatical items in such a way that it seems imperfect and significant of an incomplete learning (184). It is considered by Norrish (1983, p. 7) as a systematic deviation which happens when a learner has not learnt something, and consistently gets it wrong. However, the attempts made to put the error into context have always gone hand in hand with either [language learning and second-language acquisition] processe, Hendrickson (1987:357) mentioned that errors are ‘signals’ that indicate an actual learning process taking place and that the learner has not yet mastered or shown a well-structured [linguistic competence|competence] in the target language.

All the definitions seeme to stress either on the systematic deviations triggered in the language learning process, or its indications of the actual situation of the language learner themselves, which will later help monitoring, be it an applied linguist or particularly the language teacher to solve the problem, respecting one of the approaches argued in the Error Analysis (Anefnaf 2017). The occurrence of errors doesn’t only indicate that the learner has not learned something yet, but also it gives the linguist the idea of whether the teaching method applied was effective or it needs to be changed.

According to Corder (1976), errors signify three things: first to the teacher, in that the learner tells the teacher, if they have undertaken a systematic analysis, how far towards that goal the learner has progressed and, consequently, what remains for them to learn; second, they provide the researcher with evidence of how language is learned or acquired, and what strategies or procedures the learner is employing in their discovery of the language; third, (and in a sense this is their most important aspect) they are indispensable to the learner himself/herself, because the making of errors can be regarded as a device the learner uses in order to learn (p. 167). The occurrence of errors is merely a sign of ‘the present inadequacy of our teaching methods’(Corder 1976, p. 163).

There have been two schools of thought when it comes to error analysis and philosophy; the first one, according to Corder (1967) linked the error commitment with the teaching method, arguing that if the teaching method was adequate, the errors would not be committed; the second, believed that we live in an imperfect world and that error correction is something real and the applied linguist cannot do without it no matter what teaching approach they may use.

Errors vs. mistakes[edit]

Chomsky (1965) made a distinguishing explanation of competence and performance on which, later on, the identification of mistakes and errors will be possible, Chomsky stated that ‘’We thus make a fundamental distinction between competence (the speaker-hearer’s knowledge of his language) and performance (the actual use of language in concrete situations)’’ ( 1956, p. 4). In other words, errors are thought of as indications of an incomplete learning, and that the speaker or hearer has not yet accumulated a satisfied language knowledge which can enable them to avoid linguistics misuse. Relating knowledge with competence was significant enough to represent that the competence of the speaker is judged by means of errors that concern the amount of linguistic data they have been exposed to, however, performance which is the actual use of language does not represent the language knowledge that the speaker has. According to J. Richard et al (2002), people may have the competence to produce an infinitely long sentence but when they actually attempt to use this knowledge (to “perform”) there are many reasons why they restrict the number of adjectives, adverbs, and clauses in any one sentence (2002, 392).

The actual state of the speaker somehow involves and influences the speaker’s performance by either causing a good performance or mistakes. Thus, it is quite obvious that there is some kind of interrelationship between competence and performance; somehow, a speaker can perform well if they have had already satisfied linguistic knowledge. As a support to this, Corder (1967) mentioned that mistakes are of no significance to “the process of language learning’’ (P. 167).

Error analysis approach[edit]

Before the rise of error analysis approach, contrastive analysis had been the dominant approach used in dealing and conceptualizing the learners’ errors in the 1950s, this approach had often gone hand in hand with concept of L1 Interference and precisely the interlingual effect (Anefnaf Z. 2017), it claimed that the main cause of committing errors in the process of second language learning is the L1, in other words, the linguistic background of the language learners badly affects the production in the target language or second language.

X. Fang and J. Xue-mei (2007) pointed out that contrastive analysis hypothesis claimed that the principal barrier to second language acquisition is the interference of the first language system with the second language system and that a scientific, structural comparison of the two languages in question would enable people to predict and describe which are problems and which are not. Error analysis approach overwhelmed and announced the decline of the Contrastive Analysis which was only effective in phonology; and, according to J. Richard et al. (2002), EA developed as a branch of Linguistics in the 1960s and it came to light to argue that the mother tongue was not the main and the only source of the errors committed by the learners. In addition, Hashim, A. (1999) mentioned that the language effect is more complex and these errors can be caused even by the target language itself and by the applied communicative strategies as well as the type and quality of the second language instructions.

The aim of EA according to J. Richard et al. (2002) is, first, to identify strategies which learners use in language learning, in terms of the approaches and strategies used in both of teaching and learning. Second, to try to identify the causes of learners’ errors, that is, investigating the motives behind committing such errors as the first attempt to eradicate them. Third, to obtain information on common difficulties in Language Learning, as an aid to teaching or in the preparation of the teaching materials,

The two major causes of error, coined by the error analysis approach, are the Interlingual error which is an error made by the Learner’s Linguistic background and Native language interference, and the Intralingual error which is the error committed by the learners when they misuse some Target Language rules, considering that the error cause lies within and between the target language itself and the Learners false application of certain target language rules.

Error analysis in SLA was established in the 1960s by Corder and colleagues.[1] Error analysis (EA) was an alternative to contrastive analysis, an approach influenced by behaviorism through which applied linguists sought to use the formal distinctions between the learners’ first and second languages to predict errors. Error analysis showed that contrastive analysis was unable to predict a great majority of errors, although its more valuable aspects have been incorporated into the study of language transfer. A key finding of error analysis has been that many learner errors are produced by learners making faulty inferences about the rules of the new language.

Error analysts distinguish between errors, which are systematic, and mistakes, which are not. They often seek to develop a typology of errors. Error can be classified according to basic type: omissive, additive, substitutive or related to word order. They can be classified by how apparent they are: overt errors such as «I angry» are obvious even out of context, whereas covert errors are evident only in context. Closely related to this is the classification according to domain, the breadth of context which the analyst must examine, and extent, the breadth of the utterance which must be changed in order to fix the error. Errors may also be classified according to the level of language: phonological errors, vocabulary or lexical errors, syntactic errors, and so on. They may be assessed according to the degree to which they interfere with communication: global errors make an utterance difficult to understand, while local errors do not. In the above example, «I angry» would be a local error, since the meaning is apparent.

From the beginning, error analysis was beset with methodological problems. In particular, the above typologies are problematic: from linguistic data alone, it is often impossible to reliably determine what kind of error a learner is making. Also, error analysis can deal effectively only with learner production (speaking and writing) and not with learner reception (listening and reading). Furthermore, it cannot account for learner use of communicative strategies such as avoidance, in which learners simply do not use a form with which they are uncomfortable. For these reasons, although error analysis is still used to investigate specific questions in SLA, the quest for an overarching theory of learner errors has largely been abandoned. In the mid-1970s, Corder and others moved on to a more wide-ranging approach to learner language, known as interlanguage.

Error analysis is closely related to the study of error treatment in language teaching. Today, the study of errors is particularly relevant for focus on form teaching methodology.

In second language acquisition, error analysis studies the types and causes of language errors. Errors are classified[2] according to:

- modality (i.e., level of proficiency in speaking, writing, reading, listening)

- linguistic levels (i.e., pronunciation, grammar, vocabulary, style)

- form (e.g., omission, insertion, substitution)

- type (systematic errors/errors in competence vs. occasional errors/errors in performance)

- cause (e.g., interference, interlanguage)

- norm vs. system

Types of errors[edit]

Linguists have always been attempting to describe the types of errors committed by the language learners, and that is exactly the best way to start with, as it helps out the applied linguist to identify where the problem lies. According to Dulay et al. (1982) errors take place when the learner change the surface structure in a particularly systematic manner (p. 150), thus, the error, no matter what form and type it is, represent a damage at the level of the target language production.

Errors have been classified by J. Richard et al. (2002) into two categories. The Interlingual Error and the Intralingual Error, those two elements refer respectively to the negative influence of both the speaker’s native language, and the target language itself.

Interlingual error is caused by the interference of the native language L1 (also known as interference, linguistic interference, and crosslinguistic influence), whereby the learner tends to use their linguistic knowledge of L1 on some Linguistic features in the target language, however, it often leads to making errors. The example, provided by J. Richard et al. (2002) ‘’ the incorrect French sentence Elle regarde les (“She sees them”), produced according to the word order of English, instead of the correct French sentence Elle les regarde (Literally, “She them sees”). (P. 267) shows the type of errors aroused by the negative effect of the native language interference.

Intralingual error is an error that takes place due to a particular misuse of a particular rule of the target language, it is, in fact, quite the opposite of Interlingual error, it puts the target language into focus, the target language in this perspective is thought of as an error cause. Furthermore, J. Richard, et al. (2002) consider it as one which results from ‘’faulty or partial’’ learning of the target language. (p.267) thus the intralingual error is classified as follow:

Overgeneralizations: in linguistics, overgeneralizations error occur when the speaker applies a grammatical rule in cases where it doesn’t apply. Richard et al, (2002) mentioned that they are caused ‘’by extension of target language rules to inappropriate context.’’ (P.185). this kind of errors have been committed while dealing with regular and irregular verbs, as well as the application of plural forms. E.g. (Tooth == Tooths rather than teeth) and (he goes == he goed rather than went).

Simplifications: they result from learners producing simpler linguistic forms than those found in the target language, in other words, learners attempt to be linguistically creative and produce their own poetic sentences/utterances, they may actually be successful in doing it, but it is not necessary the case, Corder (as cited in Mahmoud 2014:276) mentioned that learners do not have the complex system which they could simplify. This kind of errors is committed through both of Omission and addition of some linguistic elements at the level of either the Spelling or grammar. A. Mahmoud (2014) provided examples based on a research conducted on written English of Arabic-speaking second year University students:

- Spelling: omission of silent letters:

- no (= know) * dout (= doubt) * weit (weight)

- Grammar:

- Omission:

- We wait ^ the bus all the time.

- He was ^ clever and has ^ understanding father.

- Addition:

- Students are do their researches every semester.

- Both the boys and the girls they can study together.

- Omission:

Developmental errors: this kind of errors is somehow part of the overgeneralizations, (this later is subtitled into Natural and developmental learning stage errors), D.E are results of normal pattern of development, such as (come = comed) and (break = breaked), D.E indicates that the learner has started developing their linguistic knowledge and fail to reproduce the rules they have lately been exposed to in target language learning.

Induced errors: as known as transfer of training, errors caused by misleading teaching examples, teachers, sometimes, unconditionally, explain a rule without highlighting the exceptions or the intended message they would want to convey. J. Richard et al. (2002) provided an example that occurs at the level of teaching prepositions and particularly ‘’ at ‘’ where the teacher may hold up a box and say ‘’ I am looking at the box ‘’, the students may understand that ‘’ at ‘’ means ‘’ under ‘’, they may later utter ‘’ the cat is at the table ‘’ instead of the cat is under the table.

Errors of avoidance: these errors occur when the learner fail to apply certain target language rules just because they are thought of to be too difficult.

Errors of overproduction: in the early stages of language learning, learners are supposed to have not yet acquired and accumulated a satisfied linguistic knowledge which can enable them to use the finite rules of the target language in order to produce infinite structures, most of the time, beginners overproduce, in such a way, they frequently repeat a particular structure.

Steps[edit]

According to linguist Corder, the following are the steps in any typical EA research:[3]

- collecting samples of learner language

- identifying the errors

- describing the errors

- explaining the errors

- evaluating/correcting the errors

collection of errors:

the nature and quantity of errors is likely to vary depending on whether the data consist of natural, spontaneous language use or careful, elicited language use.

Corder (1973) distinguished two kinds of elicitation:clinical and experimental elicitation.

clinical elicitation involves getting the informant to produce data of any sort, for example by means of general interview or writing a composition.

experimental elicitation involves the use of special instrument to elicit data containing the linguistic features such as a series of pictures which had been designed to elicit specific features.

Bibliography[edit]

- Anefnaf. Z ( 2017) English Learning: Linguistic flaws, Sais Faculty of Arts and Humanities, USMBA, Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/33999467/English_Learning_in_Morocco_Linguistic_Flaws

- Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. P. 4

- Corder, Pit. (1967). the significance of learner’s errors. International Review of Applied Linguistics, 161-170

- Dulay, H., Burt, M., & Krashen, S.D. (1982). Language two. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 150

- Edje, J (1989). Mistakes and Correction. London: Longman. P. 26

- Fang, X. & Xue-mei, J. (2007). Error analysis and the EFL classroom teaching: US-China education review, 4(9), pp. 10–14.

- Hashim, A. (1999). Crosslinguistic influence in the written English of Malay undergraduates: Journal of Modern Languages, 12, (1), pp. 59–76.

- Hendrickson, J.M. (1987). Error correction in foreign language teaching: Recent theory, research, and practice. In M.H. Long & J.C. Richards (Eds.), Methodology in TESOL: A book of readings. Boston: Heinle & Heinle. p. 357

- Norrish, J. (1983). Language learners and their errors. London: Macmillan Press. P. 7

- Richards, J. C. & Schmidt, R. (2002). Dictionary of language teaching and applied linguistics (3rd Ed.). London: Longman.

- Richards J. C., & Rodgers T. S.(2001). Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. (2nd edition), Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK. P. 153

See also[edit]

- Error (linguistics)

- Error treatment (linguistics)

- Second language acquisition

References[edit]

- ^ Corder, S. P. (1967). «The significance of learners’ errors». International Review of Applied Linguistics. 5 (1–4): 160–170. doi:10.1515/iral.1967.5.1-4.161.

- ^ Cf. Bussmann, Hadumod (1996), Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics, London: Routledge, s.v. error analysis. A comprehensive bibliography was published by Bernd Spillner (1991), Error Analysis, Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins.

- ^ Ellis, Rod (1994). The Study of Second Language Acquisition. p. 48. ISBN 9780194371896.

By

Last updated:

January 16, 2022

Today, we’re going to learn how to turn errors into lessons.

We’ll turn bad into good and wrong into right.

Nope, it’s not going to require any magic. It’s going to tap into a branch of applied linguistics called Error Analysis.

But what does this have to do with you, the language learner?

Everything!

Contents

- What’s Error Analysis?

- The Benefits of Applying Error Analysis to Your Language Learning

- 5 Hot Tips for Using Error Analysis to Improve Your Language Learning

-

- 1. Complete Plenty of Tests, Drills and Exercises

- 2. Group Your Errors for Easy Identification

- 3. Keep a Visual Record of Your Thought Processes

- 4. Evaluate Your Errors by Asking Yourself These 3 Questions

- 5. Enlist the Help of a Native Speaker

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

What’s Error Analysis?

Error Analysis (EA) is simply the systematic study of language mistakes. This analysis is done so that the identified errors can be systematically learned from and weeded out.

Stephen Pit Corder is credited with revolutionizing the field of applied linguistics in the 1960s, pointing out the utility of errors in language learning. Yes, language learners have always sought to learn from their mistakes, but Corder bolstered the effort of identifying and evaluating errors. In short, he made it less chancy and haphazard.

The steps of Error Analysis, as suggested by Corder, are:

a. collection of samples

b. identification of errors

c. description of errors

d. explanation of errors

e. evaluation of errors

Linguists basically comb through materials that have been produced by language learners, such as written tests, composed paragraphs and recorded audio. They then identify errors in the content and see if there are patterns that emerge. With the errors displayed in the light of day, explanations for them are posited and some prescriptions for course correction can be given.

Perhaps you aren’t a professional linguist, it’s true, but as a language learner you can actually use Error Analysis to inform your learning.

What linguists do for a class of Middle Eastern students learning English, you can do for yourself. You’re both the linguist and the subject at the same time.

Granted, you won’t necessarily use the rigor of statistics to assess your errors like linguists might, but casually following the above steps can still yield a ton of great information.

Even then, it’s no walk in the park, that’s for sure. This will involve the brutal honesty to admit both your strengths and weaknesses. It’ll require some metacognition on your part—an awareness and understanding of your own thought processes. But the fruits of your labor will be worth it.

Want a little taste of those juicy fruits? Here are some of the benefits of applying Error Analysis to your personal language learning experiences.

The Benefits of Applying Error Analysis to Your Language Learning

Here are the top reasons why error analysis can make for more effective language learning.

- You Can Identify Your Weaknesses

The most obvious value of Error Analysis is that it unequivocally points out your weaknesses. By looking through your mistakes, you can say to yourself, “Ah, this is where I need work.” For example, if you notice plenty of errors in verb conjugation, then you can decide to focus your effort more on that. If the verb conjugation errors are mainly related to certain tenses, then you can plan to hone in on those.

- You Can Identify Your Strengths

Performing your own casual Error Analysis double-checks your knowledge of the target language, giving you a good sense of what you’re already good at. You can always review the topics you’re better at, but you won’t end up devoting an excess of time to these topics anymore. In short, Error Analysis guides the focus of your study, saving you valuable time and effort.

- You Get an Honest Look at Your Progress

Error Analysis provides you with added insights that aren’t easily obtained from other learning approaches. With Error Analysis, you dive deeper. By following the steps of Error Analysis laid out earlier, you can seek overarching patterns. Instead of cursorily looking at overall exercise scores, you’ll carefully look at each one of your slip-ups, then figure out if they’re at all connected, getting a better understanding of your current problem areas.

For example, doing this might help you realize if the grammatical rules of your first language are negatively influencing your acquisition of the target language. By looking at all your errors in a series of exercises, you might discover that a pattern of errors emerges: You’re still applying first language rules of syntax to your target language.

- You Gain a Deeper Understanding of the Language You’re Learning

Finally, Error Analysis increases your ability to recognize nuances in the target language. Noticing, thinking about and studying your errors allows you to split hairs—which can be an excellent thing in language learning. You’ll find yourself thinking things like, “Why is this word appropriate in this context and not in that one?” or “Why is this case an exception to the rule?”

As you can see from the above benefits, there’s much to be gained here. With Error Analysis, you can really make significant leaps in learning and avoid making the same mistakes over and over. Hopefully this will result in you becoming fluent in your target language faster.

So, now that you know about the objectives and benefits of trying Error Analysis out, here are some tips on how to use it all on your own. Let’s find out how to learn a language with Error Analysis in your toolbelt.

5 Hot Tips for Using Error Analysis to Improve Your Language Learning

1. Complete Plenty of Tests, Drills and Exercises

If you’re going to make the most out of Error Analysis, you’d better give yourself plenty of data to work with.

The only way you can get sufficient results is to give yourself a significant amount of material from which to draw conclusions.

A 10-item exercise on prepositions where you get 7/10 items correct doesn’t necessarily mean you’re 70% of the way home. You might need to do much more—or much less—work to really master prepositions. Go through as many exercises as possible on each topic so that you can get a clearer benchmark. Don’t stop until you’re scoring 10/10 consistently.

Written material is the type that best lends itself to Error Analysis, because you’ll actually have a record of the errors and mistakes. Audio recordings comes second, but they’re harder to keep track of and assess accurately.

The good thing is that you can find plenty of exercises and drills online—just like this one for French learners. This resource is certainly not the spiffiest of sites, but what it lacks in finesse it more than makes up for with the great number of tests and exercises you can take. You can easily rack up a solid number of completed French exercises on this site. Another advantage is that it shows you all the questions at the same time, not following the usual one-question-at-a-time format that’s so common on similar sites. There’s also the easy print feature which could come in handy for keeping records and reviewing later. Find a site like this for your target language, and get going!

2. Group Your Errors for Easy Identification

What’s an “error” in the first place? Is it the same thing as a “mistake”?

Linguists have differentiated the two. Do you know the difference?

A mistake is a slip-up, a one-off. It’s situation-specific and can be easily corrected. Even native speakers commit them. A native English speaker could unintentionally blurt out “I drinks the juice,” even though he definitely knows the correct form. Maybe he was just sleepy or distracted. He just made a one-time mistake, and he’ll probably never make the exact same mistake again.

An error is more serious. It signifies a level of incompetence and can’t be corrected quite as easily. The error is part of a pattern and not a one-time event. The person may have intentionally chosen to use that language, thinking it’s perfectly correct. For example, if someone says, “I ate the juice,” “I ate wine” and “I eat milk every day,” they’re consistently confusing two verbs, “to eat” and “to drink.” They still need to study these two verbs and how to use them when differentiating between imbibing liquids and masticating solids.

So, now you know what an error is. That’s what you’ll need to be looking out for. Once you find them, what do you do with yours?

Group them up!

There are tons of potential errors that a language learner could make in any given language. You need to create a system of categorizing your errors that makes sense to you. Coming up with a logical grouping will help you understand where you’re making most of your errors. Seeing the connections between your errors will allow you to keep your focus on a few key areas.

You can group the errors in any manner you like, as long as the groups make sense to you. Maybe you can group similar incidences. Is an error vocabulary-related, or is it grammar-related? If it’s grammar-related, then perhaps you can jot it down next to other errors made with the same part of speech. For example, you can note down all your verb problems together. You can note down all your conjugation problems together. You can note down all your gender-agreement problems together. If one group is getting large, you can even start to create smaller sub-groups.

As you can see, there are many ways to group errors. You’re free to build your own nomenclature. It just has to be personal and meaningful to you—after all, you’ll be the only one to use it.

3. Keep a Visual Record of Your Thought Processes

Now we’re really getting into the deeper levels of Error Analysis here. This will require a certain level of self-awareness on your part. Like I said earlier, Error Analysis requires metacognition, an understanding of your own thought processes. Why do you tend to make the same errors? What was your thinking behind these errors?

Here’s how to go about keeping track of errors and the thought processes behind them.

For example, when you’re speaking and you suddenly take a long pause—not for effect or for thoughtful reasons, but because you’re unsure of what to say—that could be a sign of lacking knowledge or confidence in your language. You’re probably drawing a blank. What word are you unsure about? What caused the pause? What were you just thinking about?

Indicate this moment on a sheet of paper, using your very own words. You could write something like:

forgot the past tense of the word “cut.”

didn’t know what the word for “sleep” is in Chinese.

got tongue-tied trying to pronounce the “rr” sound in a Spanish word.

When you’re answering the questions in a multiple choice exercise and you’re alternating between the choices, this indecision betrays a knowledge gap. It means you still haven’t gotten a good handle on the subject matter in question. Mark down those numbers with a star or a question mark so that when you review you can remind yourself that you had difficulty with that particular item—even if it turns out that you got the correct answer.

It’s these little marks on a sheet of paper that give you a visual of your thought process, heretofore unseen. It’s a record of the areas that are challenging to you and a great way to discover patches of weakness.

4. Evaluate Your Errors by Asking Yourself These 3 Questions

When you do personal Error Analysis, you don’t have a team of linguists positing explanations of why you made this or that error. You only have yourself to investigate and yourself to do the investigation.

You need to ask yourself these questions as you evaluate the error.

a. What rule or principle did I miss?

Asking this question forces you to think about the grammar rules that exist in your target language. It checks if you’ve been the wiser this time and are now aware why an error exists. If you can’t answer this question, then you can’t be sure that the error won’t haunt you some other time.

Note: When considering rules and principles, you should also consider their exceptions.

b. Why did I think my initial answer was correct?

This is another important question to ask when you evaluate the error because it looks into your incomplete understanding of the target language. When you completed the exercise, you did it using your present and personal understanding of the language. Comparing your original reasons to the correct answers hones more of this understanding, eliminating faulty impressions and replacing them with accurate ones.

Note: If you answer this question with, “I only guessed,” then it counts as an even bigger knowledge gap.

c. What should I do so I won’t make the same mistake?

This is the proactive part of the evaluation process. Not only are you now aware and wary of your errors, you’ll be taking active steps to weed out your weaknesses. Think of this part as the “New Year’s resolution” of the process.

Your answers to this question could be something like:

Create flashcards for the rules of this verb conjugation.

Memorize five new words a day. Review them before going to sleep.

Use my language learning app every day, for at least 10 minutes.

Listen to an audio course or podcast on my daily commute.

Most important of all, have the nerve to follow through with your plan. There’s no point in making a resolution and an action plan if you’re not going to resolve to act on it.

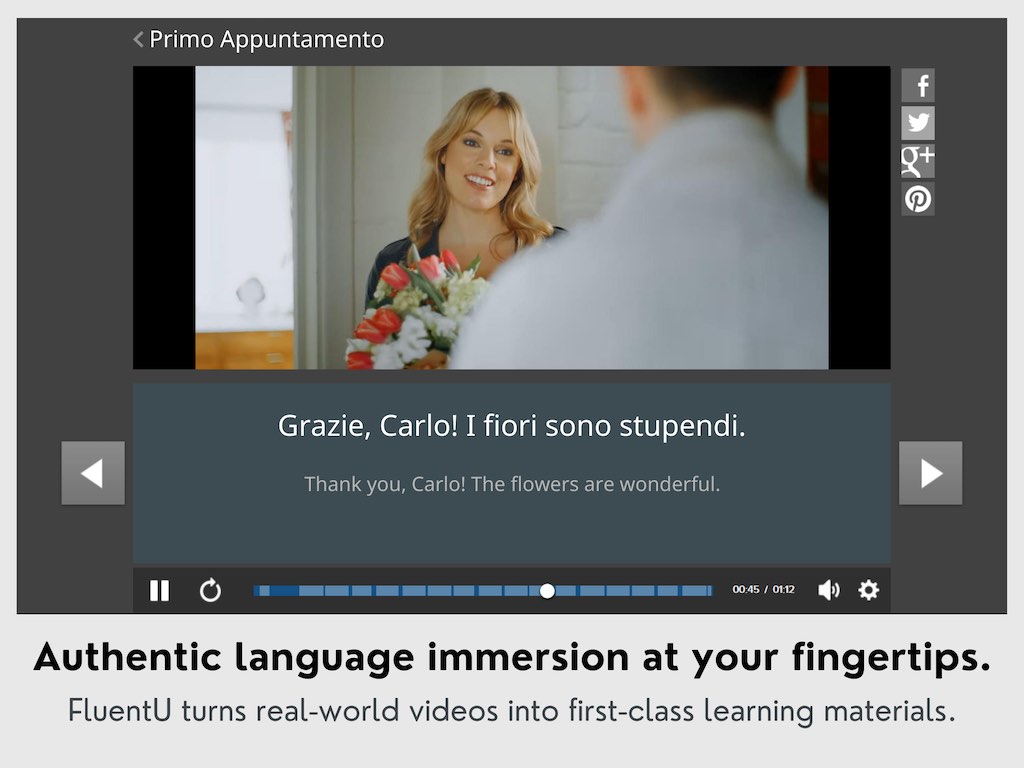

Language learning apps in particular have become a popular and convenient way to accomplish consistent goals and keep you on your toes when it comes to common language fumbles. That’s because apps such as FluentU can actually incorporate most of the above resolutions into one neat package.

In the case of FluentU, the program teaches with authentic videos, meaning you can watch and hear the target language in action. These videos are supplied with interactive subtitles that give you instant access to a word’s definition and usages in example sentences. You can then review material with personalized quizzes or multimedia flashcards.

So if you’re worried about mistakes, push forward and hone your knowledge with reliable resources and constant targeted practice.

5. Enlist the Help of a Native Speaker

You’ve probably had the experience of listening to an English beginner, right?

The mistakes and errors are evident to you, and they poke you like a string out of tune. As a native or fluent speaker, you’ll have a sharp ear for language mistakes in English.

If you’re looking for someone to spot the mistakes and errors you make in your target language, a native speaker will do a great job. Even minor grammatical errors will ring loud bells in their heads.

A native speaker can guide you towards mastering the nuances of your target language. There may be instances when a certain word you’re using is grammatically sound, but to a native speaker it’ll sound a bit off—a little less than natural. They can point out things like this and give you a more appropriate lexicon.

A native speaker can also highlight some of the exceptions to grammatical or syntactical rules that go beyond what can be offered in any textbook. And if you want to learn the most contemporary way of speaking the target language, you’ll certainly want a native speaker to keep you updated.

Luckily, native speakers in any major language are readily available on any language exchange site. A language exchange site is a place where you can trade your innate knowledge of your native language for another person’s native knowledge of your target language. For example, let’s say you’re an English speaker who wants to learn Spanish. You can find a native Spanish speaker who wants to learn how to speak English—thus, an “exchange” takes place. You’re helping another as that person is helping you.

If that sounds great, you’ll definitely want to check out the best online language exchange sites to find your learning partner!

So, there you have it!

Don’t be too hard on yourself and always remember that linguistic errors are never fatal. Nor are they permanent. They’re but signs of an incomplete understanding and can be remedied with a little study.

You’re now ready to face the music and tango with your own linguistic errors.

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

УДК 81-13

И. Е. Абрамова

Метод анализа ошибок в лингвистических исследованиях

Цель статьи — изучить применение метода анализа ошибок в лингвистических исследованиях. Представлен обзор литературы по данной проблематике. Приводятся результаты слухового анализа реализаций английских согласных русскоязычными студентами и их преподавателями. С помощью метода анализа ошибок исследуются особенности влияния произношения преподавателя на носителя языка и группового речевого кода на произношение билингвов.

Ключевые слова: метод анализа ошибок, искусственный билингвизм, преподаватель не носитель языка, малая социальная группа

I. E. Abramova

Error Analysis in Linguistic Research Studies

The purpose of this paper is to consider the using of error analysis in linguistic research studies. First of all it gives a brief overview of the scientific literature on the topic. Then the results of the phonetic experiment testing the production accuracy of English consonants by bilinguals are analyzed. With the help of error analysis we investigate the influence of non-native English teachers’ pronunciation proficiency on the pronunciation of their students and the peculiarities of а social group language code. Finally, some conclusions are made.

Key words: error analysis, artificial bilingualism, phonetic accent, non-native-English-speaking teachers, a small social group.

Те или иные отклонения в речи всегда привлекали лингвистов, давая не только пищу для размышлений, но и эмпирическую базу для теоретических выводов. Не случайно Л. В. Щерба считал, что роль разного рода ошибок в речи, «роль этого отрицательного материала громадна и совершенно еще не оценена в языкознании» [6, с. 259]. Такой исследовательский подход, как анализ ошибок, применяется в лингвистике, лин-гводидактике, в исследованиях по межкультурной коммуникации, социолингвистике.

В рамках внутренней лингвистики метод анализа типичных ошибок в сочетании с сопоставительным или контрастивным методом используется для изучения интерференции. Если с помощью сопоставительного структурно-лингвистического анализа можно выявлять поля вероятностной интерференции, то анализ ошибок позволяет отбирать и классифицировать нестандартные языковые явления в речи билингвов на неродном языке. Это дает возможность исследовать реальный результат интерференции -иностранный акцент, проявляющийся в тех или иных отклонениях от кодифицированной нормы, и определять конкретные проявления интерференции, ее характер. Сочетание двух методов считается обязательным, так как установлено,

что ошибки, прогнозируемые в результате сопоставления, не всегда актуализируются в речи [1]. Однако контрастивный анализ и анализ ошибок во многих случаях имеют узкую теоретическую направленность, носят констатирующий характер и позволяют решить лишь проблему прогноза фонетических нарушений, что недостаточно с практической точки зрения. Как справедливо замечает А. А. Залевская, «представители разных исследовательских подходов неизбежно осознают необходимость выхода за рамки применения отдельных процедур и формирования комплексных программ научных изысканий. При этом в дополнение к КА (контрастивному анализу), АО (анализу ошибок) и ИМ (интроспективным методам) используются наблюдение и эксперимент, привлекаются искусственные языки для выявления принципов переработки человеком незнакомого ему языка и т. д.» [3, с. 310].

Ошибки в иностранном языке рассматриваются специалистами по лингводидактике как «результат неправильной операции выбора языковых средств иностранного языка для выражения правильно запрограммированной мысли» [1, с. 30]. Среди причин неправильного выбора выделяют семантическое, структурное и функцио-

© Абрамова И. Е., 2011

нальное отождествления явлений родного и иностранного языков, а также явлений внутри иностранного языка, наряду с влиянием таких факторов, как переосмысление на почве недопонимания, возникновение неправильных ассоциаций. А. А. Залевская подчеркивает, что овладение языком заключается в формировании навыков через практику и подкрепление. Поскольку ко времени овладения вторым языком навыки пользования первым языком являются прочно установившимися, они оказывают решающее влияние на становление новых навыков второго языка: происходит перенос уже имеющихся навыков, сопоставительный анализ систем двух языков позволяет выявлять факты совпадения и расхождения и обнаруживать «критические моменты», которые необходимо учитывать для предотвращения интерференции [3]. Признан доказанным тот факт, что только часть ошибочных реализаций в речи билингва может быть объяснена за счет влияния родного языка. К такого рода ошибкам относят межъязыковые (interlingual errors), то есть ошибки межъязыковой интерференции. Кроме того, встречается множество ошибок, типичных для речи изучающих иностранный язык, независимо от их родного языка. Ошибки такого рода получили название внутриязыковых (intralingual errors). Подобные ошибочные реализации отражают специфику процесса овладения языком, поэтому их еще определяют и как «ошибки развития» (developmental errors) [3, с. 298].

Анализ фонетических ошибок, как правило, ограничивается лингвистическим и психолингвистическим аспектами, при этом возникновение ошибочных реализаций объясняется фонетической интерференцией, другие факторы во внимание не принимаются. Считается, что характер произносительных ошибок при усвоении иностранного языка зависит от двух основных факторов: 1) от соотношений между фонематическими системами языков и 2) от особенностей фонетической реализации звуков в них, то есть от артикуляторных навыков, характерных для обоих языков [7]. Типологию прогнозируемых ошибок в произношении русскоязычных билингвов разрабатывали многие известные специалисты по фонетике (Г. П. Торсуев, 1950, 1953, 1975 гг.; А. Б. Мишин, 1983, 1985 гг.; В. В. Кулешов, А. Б. Мишин, 1981, 1987 гг.; М. А. Соколова, К. П. Гинтовт, И, с. Тихонова, Р. М. Тихонова, 1997, 2006 гг.; С. Ф. Леонтьева, 2004 г.).

В соответствии с современными требованиями обучение иноязычному произношению должно быть нацелено на естественное, социально и культурно приемлемое звучание иноязычной речи. А. Н. Леонтьев подчеркивал необходимость определения оптимума требований при обучении иностранному языку: «Так, мера для определения требований к фонетике речи — это, как ее называют в теории коммуникации, степень интел-лигибельности речи, то есть ее «понимаемости» собеседником, владеющим данным языком как родным» [5, с. 33].

Определенный интерес к речевым ошибкам проявляют и специалисты по межкультурной коммуникации, разрабатывающие понятия межкультурной компетенции, лингвистической компетенции, коммуникативной значимости ошибок и отклонений. Часть нестандартных явлений в речи билингвов объясняется отсутствием или недостатком точности, то есть лингвистической компетенции коммуникантов. Если же включение в речь некоторых языковых особенностей зависит от уровня межкультурной компетенции говорящего, то их оценивают с точки зрения уместности, то есть обусловленности социокультурным контекстом, и коммуникативной значимости, то есть влияния на эффективность коммуникации.

В социолингвистических исследованиях особое внимание уделяется разного рода ошибочным реализациям, так как некоторые из них традиционно рассматриваются в качестве социолингвистических переменных и социальных маркеров, являющихся основными операционными единицами в исследованиях такого рода (Labov, 1966 г.; Лабов, 1975 г.; Белл, 1980 г.; Trudgill, 2000 г.; Wells, 2000, 2008 гг.). Говоря о формальных средствах исследования внутреннего варьирования в речевом коллективе, У. Лабов писал: «…модели этого варьирования довольно прозрачны и не требуют для своего обнаружения статистического анализа записей речи сотен информантов <…> Основные модели, например, классовой стратификации выявляются уже на выборке в 25 человек. В высшей степени регулярные типы стилистической и социальной стратификации устанавливаются даже в том случае, когда наша индивидуальная ячейка содержит всего пять говорящих, и мы имеем не более чем по 5-10 примеров данной переменной на каждого. С такими регулярными и воспроизводимыми данными мы в состоянии определить, что значит «стилистическое», или «социальное», значение»

[4, с. 115-116]. Социолингвистические переменные характеризуются соотнесенностью, с одной стороны, с определенным уровнем языковой структуры (фонологическим, морфологическим, синтаксическим, лексико-семантическим), с другой — с варьированием социальной структуры или социальных ситуаций. Так, А. С. Герд обратил внимание, что у разных людей сильно различается степень владения литературным языком: даже в официальной речи лекторов, профессоров, учителей, писателей, художников встречается множество фонетических и акцентологических отклонений [2, с. 26].

Далее представлены результаты, полученные в ходе экспериментально-фонетического исследования, проведенного на кафедре иностранных языков гуманитарных факультетов Петрозаводского государственного университета. Цель эксперимента — изучить особенности влияния произношения преподавателя не носителя языка на произношение его студентов при усвоении иноязычной фонетики в аудиторных условиях и характер проявления фонетического акцента в малых социальных группах закрытого типа, к которым относятся учебные группы. Исследование основывается на учете не только реализаций, соответствующих орфоэпическому стандарту, но и ошибочных реализаций английских фонем с применением метода анализа ошибок.

Преподавание фонетики английского языка на кафедре ИЯГФ осуществляется в двух основных режимах. В группах общего профиля (условно обозначенных латинскими буквами А, В, С) фонетика преподается в рамках общеобразовательной дисциплины «английский язык» в русле концепции «аппроксимации». В группах Б и Е, занимающихся по программе дополнительной квалификации «Переводчик в сфере профессиональной коммуникации», преподается отдельная дисциплина «Практическая фонетика».

Материалом исследования стали записи чтения специально подобранных изолированных слов и текста 40 информантами (35 студентов и 5 преподавателей) из пяти академических групп гуманитарных специальностей. Рамки статьи не позволяют рассмотреть все данные, поэтому ограничимся анализом наиболее показательных результатов по реализациям английских согласных.

Как ожидалось, реализации, соответствующие современной орфоэпической норме британского варианта английского языка, наблюдаются в большей мере в речи дикторов из специализиро-

ванных групп Б и Е. Так, учащиеся специализированных групп чаще всего реализуют английские апикально-альвеолярные Ш, М/, /8/, /т/, /1/, /п/. Студенты группы Б произносят эти согласные в 96,9 % от общего числа реализаций, студенты группы Е — в 99,4 %; преподаватели групп Б и Е реализуют только апикально-альвеолярные согласные. Если показатели по группе А в целом мало отличаются от вышеназванных (так, средний показатель среди студентов составил 80,5 %, а в группе преподавателей — 99,4 %), то учащиеся из групп В и С чаще заменяют английские согласные русскими дорсальными переднеязычными. В группе В процент реализаций апикаль-но-альвеолярных согласных составил 62,6 %, в группе С — только 26,9 % от общего числа реализаций; показатели в группе преподавателей -81,6 и 98,7 % соответственно. Обращает на себя внимание следующий факт: реализации некоторых аллофонов согласных фонем отмечены только в произношении учащихся из специализированных групп с углубленным изучением фонетики, что является следствием применения разных методик обучения фонетике английского языка. Так, в группах Б и Е зафиксированы такие нормативные реализации, как предглоттализация конечных [р], [1], [к] и замены конечных /П/, /п^ ^ [пп].

Наиболее частотными ошибочными реализациями английских смычных, вызванными интерферирующим влиянием родного языка, стали: 1) сильное смягчение согласных перед гласными переднего ряда /1:/, Л/, /е/, /ж/; 2) чрезмерное оглушение слабозвонких согласных в конечной позиции; 3) чрезмерная аспирация конечных [рь], Й, [кь]. Указанные типы ошибок относятся к разряду прогнозируемых и наиболее частотны в группах общего профиля. Показательно, что степень распространенности прогнозируемых ошибок в речи студентов почти во всех академических группах в определенной мере соотносится с количеством этих ошибок в речи преподавателей. Например, преподаватель группы А практически не смягчает английские согласные (зафиксировано только 1,6 % случаев чрезмерно сильной палатализации), преподаватель группы В чрезмерно смягчает согласные в 23,9 % случаев, показатели студентов группы А составили 24,1 %, студентов группы В — 49,4 %. В группе С студенты реализуют сильную палатализацию значительно чаще (56,8 %), чем преподаватель (2,4 %). В целом число прогнозируемых ошибочных реализаций в группах общего профиля

существенно превышает показатели в специализированных группах, что свидетельствует как о разной эффективности применяемых методик обучения фонетике английского языка, так и о различном уровне внимания к звуковой стороне речи со стороны преподавателей и самих учащихся.

К частотным ошибкам, вызванным некорректным обучением, были отнесены следующие: 1) озвончение /а/ ^ [Г], /Ь/ ^ [Ьэ], ^ [¿Ч, /у/ ^ [у8], /г/ ^ ^э], /3/ ^ [Зэ], /б/ ^ [бэ] в конечной позиции; 2) чрезмерная аффрикатизация английских переднеязычных смычных взрывных [¿], [а3]. Указанные типы ошибок распространены, прежде всего, в группах общего профиля, причем средние показатели количества ошибок в речи студентов групп специфическим образом коррелируют с числом подобных ошибок в произношении преподавателей. Так, озвончение конечных согласных зафиксировано в произношении студентов группы А в 25,3 % случаев, студентов группы В — в 21,5 %, процентные показатели преподавателей данных групп составили 51,5 и 42 % случаев соответственно, что количественно превышает показатели студентов. Это вызвано стремлением преподавателей предотвратить нарушения по признаку звонкости/глухости и провоцирует слишком звонкое произношение конечных слабозвонких согласных. Данная ошибка преподавателей вызывает соответствующие нарушения у студентов. Этот тип неточных реализаций можно отнести к методическим ошибкам, так как для русского языка нехарактерно звонкое произношение конечных согласных.

В то же время преподаватели специализированных групп не озвончают согласные /а/, /Ь/, /§/, /у/, /е/, /3/, /б/ в конечной позиции (учитывая, что в нормативном произношении характер согласного в конечной позиции определяется долготой гласного), такая ошибка практически не встречается и в речи студентов. Как специфичные акцентные особенности, характерные только для студентов и преподавателей групп Б и Е, следует отметить замену глухих смычных взрывных /р/, /к/ в позиции абсолютного конца на гортанную смычку, что в большей степени характерно для группы Б (студенты имеют показатель 66,4 %, преподаватель — 62,8 %) и также является методической ошибкой.

Особый интерес представляют отдельные реализации, которые можно было бы классифицировать как прогнозируемые, если бы они не встречались в произношении самих носителей

британского варианта английского языка. Речь идет о заменах заднеязычного /д/ на [п] либо на сочетания [п§] и [пк], о заменах межзубных щелевых /9/, /б/ на губно-зубные [у]. Такие замены зафиксированы, прежде всего, в группах общего профиля, в специализированных группах подобные реализации не отмечены. Профессор Дж. Уэллс, отмечая демократизацию современной орфоэпической нормы на Британских островах, описывает вышеуказанные замены /д/ ^ [п§], [пк], /9/ ^ [£], /б/ ^ [у] как широко распространенные, но характерные для территориальных типов произношения [8, р. Х1Х-ХХ]. В произношении дикторов группы Б периодически наблюдалась замена Ш на гортанную смычку в интервокальной позиции, что также классифицируется специалистами по английской фонетике как реализация, характерная для дикторов с невысоким социальным статусом [8, р. 345-346].

Основываясь на экспериментальных данных, полученных с применением метода анализа ошибок, можно сделать вывод, что в условиях искусственного билингвизма имеет место фонетическая вариативность в речи взрослых учащихся, вызванная, помимо лингвистических причин, специфическими условиями обучения и зависящая в определенной мере от особенностей произношения преподавателя иностранного языка, используемой методики обучения фонетике, а также речевых предпочтений студентов, характерных для группового речевого кода конкретной учебной группы. Выявлено несколько основных типов воздействия произношения русскоязычного преподавателя английского языка на произношение студентов: 1) преподаватель успешно преодолевает интерферирующее влияние родного языка в своем произношении и эффективно помогает в этом своим студентам (группы Б, Е); 2) для произношения преподавателя характерен умеренный иностранный акцент, однако хорошее произношение преподавателя не оказывает заметного влияния на произношение его учеников (группа С); 3) студенты реализуют как произносительные ошибки, вызванные интерферирующим влиянием родного языка, так и ошибки обучения; степень распространенности таких ошибок в речи студентов коррелирует с их количеством в речи преподавателя (группы А, В). Проведенный эксперимент дополняет понимание механизмов формирования и проявления фонетической вариативности на продуктивном уровне вне естественной языковой среды, его

результаты могут быть учтены при разработке методик преподавания фонетики.

Библиографический список

1. Будренюк, Г. М. Языковая интерференция и методы ее выявления [Текст] / Г. М. Будренюк, В. М. Григоревский. — Кишинев : Штиинц , 1978. — 126 с.

2. Герд, А. С. Введение в этнолингвистику [Текст] / А. С. Герд. — СПб. : Изд-во СПбГУ , 2005. -456 с.

3. Залевская, А. А. Введение в психолингвистику [Текст] / А. А. Залевская. — М. : Российск. гос. гума-нит. ун-т , 1999. — 382 с.

4. Лабов, У. Исследование языка в его социальном контексте [Текст] / У. Лабов // Новое в лингвистике. Вып. 7. Социолингвистика. — М. : Прогресс , 1975. — С. 96-167.

5. Леонтьев, А. Н. Некоторые вопросы психологии обучения речи на иностранном языке [Текст] / А. Н. Леонтьев // Психологические основы обучения неродному языку : хрестоматия / сост. А. А. Леонтьев. — М. ; Воронеж , 2004. — С. 28-37.

6. Щерба, Л. В. О трояком аспекте языковых явлений и об эксперименте в языкознании [Текст] / Л. В. Щерба // Хрестоматия по истории языкознания XIX-XX вв. / под ред. В. А. Звегинцева. — М. : Просвещение , 1956. — С. 252-264.

7. Weinreich, U. Languages in Contact [Text] / U. Weinreich. — N. Y: Linguistic Circle, 1953 (1st ed.). -148 p.

8. Wells , J. Longman Pronunciation Dictionary [Text] / J. Wells — Barcelona: Longman, 3-d edition. 2008. — 922 p.

В лингвистике, согласно J. Richard et al., (2002), ошибка — это использование слова, речевого акта или грамматических элементов таким образом, что оно кажется несовершенным и значимым для неполного обучения (184). Норриш (1983, с. 7) считает это систематическим отклонением, которое происходит, когда учащийся чему-то не научился и постоянно ошибается. Однако попытки поместить ошибку в контекст всегда шли рука об руку с процессами изучения языка и освоения второго языка, Хендриксон (1987: 357) отметил, что ошибки являются «сигналы», указывающие на то, что происходит реальный процесс обучения и что учащийся еще не усвоил или не продемонстрировал хорошо структурированную компетенцию на целевом языке.

Все определения, казалось, акцентировали внимание либо на систематических отклонениях, возникающих в процессе изучения языка, либо на указаниях на фактическую ситуацию самого изучающего язык, что впоследствии поможет наблюдателю, будь то лингвист-прикладник или, в частности, учителя языка для решения проблемы, соблюдая один из подходов, аргументированных в Анализе ошибок (Anefnaf 2017), появление ошибок не только указывает на то, что учащийся что-то еще не усвоил, но и дает лингвисту представление о том, применяемый метод обучения был эффективным или его необходимо изменить.

Согласно Кордеру (1976) ошибки важны по трем причинам, во-первых, для учителя, поскольку они говорят ему, если он или она проводит систематический анализ, насколько далеко продвинулся ученик к этой цели и, следовательно, то, что ему остается изучить. Во-вторых, они предоставляют исследователю доказательства того, как язык изучается или приобретается, и какие стратегии или процедуры использует учащийся при открытии языка. В-третьих (и в некотором смысле это их самый важный аспект) они незаменимы для самого учащегося, потому что мы можем рассматривать совершение ошибок как средство, которое учащийся использует для обучения (стр. 167). Возникновение ошибок — это просто признаки «нынешней неадекватности наших методов обучения» (Кордер, 1976, стр. 163).

Существуют две школы мысли, когда дело доходит до анализа ошибок и философии, первая, согласно Кордеру (1967), связывает совершение ошибок с методом обучения, утверждая, что если метод обучения был адекватным, то ошибки не будут совершаться, вторая школа считала, что мы живем в несовершенном мире и что исправление ошибок — это что-то реальное, и прикладной лингвист не может обойтись без этого, независимо от того, какой подход к обучению они используют.

Содержание

- 1 Ошибки против ошибок

- 2 Подход к анализу ошибок

- 3 Типы ошибок

- 4 Шага

- 5 Библиография

- 6 См. Также

- 7 Ссылки

Ошибки против ошибок

Хомский (1965) дал отличительное объяснение компетентности и производительности, на основании которого впоследствии будет возможно выявление ошибок и ошибок. Хомский заявил: «Таким образом, мы проводим фундаментальное различие между компетентность (знание говорящим-слушателем своего языка) и производительность (фактическое использование языка в конкретных ситуациях) » (1956, с. 4). Другими словами, ошибки считаются признаком неполного обучения и того, что говорящий или слушающий еще не накопил удовлетворительных языковых знаний, которые могут позволить им избежать неправильного лингвистического использования. Связь знаний с компетенцией была достаточно значительной, чтобы представить, что компетенция говорящего оценивается с помощью ошибок, которые касаются количества лингвистических данных, которым он или она подверглись, однако производительность, которая является фактическим использованием языка, не отражает знание языка, которым владеет говорящий. Согласно Дж. Ричарду и соавторам (2002), люди могут обладать компетенцией для создания бесконечно длинных предложений, но когда они фактически пытаются использовать это знание («выполнять»), существует множество причин, по которым они ограничивают количество прилагательных, наречий., и пункты в одном предложении (2002, 392).

Фактическое состояние говорящего каким-то образом связано с его работой и влияет на нее, вызывая либо хорошее выступление, либо ошибки. Таким образом, совершенно очевидно, что существует некоторая взаимосвязь между компетенцией и эффективностью; каким-то образом говорящий может хорошо выступить, если он или она уже имеют достаточные лингвистические знания. В подтверждение этого Кордер (1967) упомянул, что ошибки не имеют значения для «процесса изучения языка» (стр. 167).

Подход к анализу ошибок

До появления подхода анализа ошибок контрастный анализ был доминирующим подходом, который использовался при рассмотрении и осмыслении ошибок учащихся в 1950-х годах, этот подход часто применялся параллельно вместе с концепцией интерференции L1 и именно межъязыкового эффекта (Anefnaf Z. 2017), он утверждал, что основной причиной совершения ошибок в процессе изучения второго языка является L1, другими словами, лингвистический фон изучающих язык плохо влияет на производство на целевом языке.

Х. Фанг и Дж. Сюэ-мэй (2007) указали, что гипотеза контрастного анализа утверждает, что основным препятствием для овладения вторым языком является вмешательство системы первого языка в систему второго языка и что научное структурное сравнение двух языков в вопрос позволил бы людям предсказать и описать, какие проблемы, а какие нет. Подход к анализу ошибок подавил и объявил упадок контрастного анализа, который был эффективен только в фонологии; и, согласно J. Richard et al. (2002), EA развивалась как отрасль лингвистики в 1960-х годах, и выяснилось, что родной язык не был основным и единственным источником ошибок, совершаемых учащимися. Кроме того, Хашим А. (1999) упомянул, что языковой эффект более сложен, и эти ошибки могут быть вызваны даже самим целевым языком и применяемыми коммуникативными стратегиями, а также типом и качеством инструкций на втором языке.

Цель EA согласно J. Richard et al. (2002), во-первых, чтобы определить стратегии, которые учащиеся используют при изучении языка, с точки зрения подходов и стратегий, используемых как в преподавании, так и в обучении. Во-вторых, попытаться определить причины ошибок учащихся, то есть исследовать мотивы совершения таких ошибок в качестве первой попытки их искоренить. В-третьих, чтобы получить информацию о типичных трудностях в изучении языка, в качестве помощи в обучении или при подготовке учебных материалов,

Двумя основными причинами ошибки, выдвинутыми методом анализа ошибок, являются межъязыковая ошибка. что является ошибкой, связанной с языковым прошлым учащегося и вмешательством на родном языке, а также внутриязыковой ошибкой, которая является ошибкой, совершаемой учащимися при неправильном использовании некоторых правил целевого языка, учитывая, что причина ошибки находится внутри и между самим целевым языком и Ложное применение учащимися определенных правил изучаемого языка.

Анализ ошибок в SLA был разработан в 1960-х годах Кордером и его коллегами. Анализ ошибок (EA) был альтернативой контрастному анализу, подходу, основанному на бихевиоризме, с помощью которого прикладные лингвисты стремились использовать формальные различия между первым и вторым языками учащихся для прогнозирования ошибок.. Анализ ошибок показал, что сравнительный анализ не может предсказать подавляющее большинство ошибок, хотя его более ценные аспекты были включены в исследование языкового перевода. Ключевой вывод анализа ошибок заключался в том, что многие ошибки учащихся возникают из-за того, что учащиеся делают неверные выводы о правилах нового языка.

Аналитики ошибок различают ошибки, которые являются систематическими, и ошибки, которые таковыми не являются. Они часто стремятся разработать типологию ошибок. Ошибка может быть классифицирована по основному типу: пропускающая, аддитивная, замещающая или связанная с порядком слов. Их можно классифицировать по тому, насколько они очевидны: явные ошибки, такие как «Я злюсь», очевидны даже вне контекста, тогда как скрытые ошибки очевидны только в контексте. С этим тесно связана классификация по предметной области, широте контекста, который аналитик должен исследовать, и степени, широте высказывания, которое необходимо изменить, чтобы исправить ошибку. Ошибки также могут быть классифицированы по уровню языка: фонологические ошибки, словарные или лексические ошибки, синтаксические ошибки и т. Д.. Их можно оценивать по степени, в которой они мешают коммуникации : глобальные ошибки затрудняют понимание высказывания, а локальные — нет. В приведенном выше примере фраза «Я злюсь» будет локальной ошибкой, поскольку смысл очевиден.

С самого начала анализ ошибок был связан с методологическими проблемами. В частности, вышеуказанные типологии проблематичны: на основе одних лишь лингвистических данных часто невозможно надежно определить, какую ошибку совершает учащийся. Кроме того, анализ ошибок может эффективно работать только с продукцией учащегося (говорение и письмо ), но не с приемом учащегося (слушание и чтение ). Кроме того, он не может объяснить использование учащимся коммуникативных стратегий, таких как избегание, в которых учащиеся просто не используют форму, с которой им неудобно. По этим причинам, хотя анализ ошибок по-прежнему используется для исследования конкретных вопросов в SLA, поиск всеобъемлющей теории ошибок обучаемого в значительной степени оставлен. В середине 1970-х Кордер и другие перешли к более широкому подходу к языку изучаемого, известному как межъязыковой.

Анализ ошибок тесно связан с изучением обработки ошибок при обучении языку. Сегодня изучение ошибок особенно актуально для методики преподавания формы.

В приобретении второго языка, анализ ошибок изучает типы и причины языковых ошибок. Ошибки классифицируются по:

- модальности (т. Е. Уровню владения речью, письму, чтению, аудированию )

- языковым уровням (т. Е. произношение, грамматика, словарь, стиль )

- форма (например, пропуск, вставка, подстановка)

- тип (систематические ошибки / ошибки в компетенции против случайных ошибок / ошибок в работе)

- причина (например, помехи, межъязыковые )

- нормы по сравнению с системой

Типы ошибок

Лингвисты всегда пытались описать типы ошибок, совершаемых изучающими язык, и это как раз лучший способ начать, поскольку он помогает прикладному лингвисту определить, в чем заключается проблема. (1982) ошибки возникают, когда учащийся изменяет поверхностную структуру особенно систематическим образом (стр. 150), таким образом, ошибка, независимо от ее формы и типа, представляет собой ущерб на уровне производства целевого языка.

Ошибки были en классифицировано J. Richard et al. (2002) на две категории. Межъязыковая ошибка и Внутриязыковая ошибка, эти два элемента, соответственно, относятся к негативному влиянию как родного языка говорящего, так и самого целевого языка.

Межъязыковая ошибка вызвана вмешательством родного языка L1 (также известным как вмешательство, лингвистическое вмешательство и межъязыковое влияние), в результате чего учащийся склонен использовать свои лингвистические знания L1 на некоторых языковых особенностях в целевой язык, однако, это часто приводит к ошибкам. Пример, представленный J. Richard et al. (2002) ‘’ неправильное французское предложение Elle regarde les («Она видит их»), произведенное в соответствии с порядком слов в английском языке, вместо правильного французского предложения Elle les regarde (буквально, «Она их видит»). (Стр. 267) показаны типы ошибок, вызванные негативным влиянием вмешательства на родном языке.

Внутриязыковая ошибка — это ошибка, которая возникает из-за определенного неправильного использования определенного правила целевого языка, фактически, это полная противоположность межъязыковой ошибке, она ставит целевой язык в фокус, целевой язык с этой точки зрения рассматривается как причина ошибки. Кроме того, J. Richard et al. (2002) считают, что это результат «неправильного или частичного» изучения целевого языка. (стр.267) Таким образом, внутриязыковая ошибка классифицируется следующим образом:

Чрезмерное обобщение: в лингвистике ошибка чрезмерного обобщения возникает, когда говорящий применяет грамматическое правило в тех случаях, когда оно не применяется. Ричард и др. (2002) упомянули, что они вызваны «расширением правил целевого языка на несоответствующий контекст» (стр.185). такого рода ошибки допускаются при работе с правильными и неправильными глаголами, а также при применении форм множественного числа. Например. (Зуб == Зубы, а не зубы) и (он идет == он скорее пошел, чем пошел).

Упрощения: они возникают в результате того, что учащиеся создают более простые языковые формы, чем те, которые встречаются в изучаемом языке, другими словами, учащиеся пытаются быть лингвистически креативными и создавать свои собственные поэтические предложения / высказывания, они могут действительно преуспеть в этом Это, но не обязательно, Кордер (цитируется в Mahmoud 2014: 276) отметил, что у учащихся нет сложной системы, которую они могли бы упростить. Ошибки такого рода совершаются как из-за пропусков, так и из-за добавления некоторых лингвистических элементов на уровне орфографии или грамматики. А. Махмуд (2014) привел примеры, основанные на исследовании письменного английского арабоговорящих студентов второго курса университета:

- Орфография: пропуск молчаливых букв:

- нет (= знаю) * dout (= сомневаюсь) * weit (вес)

- Грамматика:

- Упущение:

- Мы все время ждем ^ автобус.

- Он был ^ умен и имел ^ понимающего отца.

- Дополнение:

- Студенты проводят свои исследования каждый семестр.

- И мальчики, и девочки могут учиться вместе.

- Упущение:

Ошибки развития: такого рода ошибки каким-то образом является частью сверхобобщения (позже это будет обозначено как естественные ошибки стадии обучения и стадии развития), DE являются результатами нормального паттерна развития, например (come = comed) и (break = breaked), DE указывает, что учащийся начали развивать свои лингвистические знания и не смогли воспроизвести правила, которым они недавно подвергались при изучении целевого языка.

Индуцированные ошибки: так называемые «перенос обучения», ошибки, вызванные вводящими в заблуждение примерами обучения, иногда учителя безоговорочно объясняют правило, не выделяя исключений или предполагаемого сообщения, которое они хотели бы передать. J. Richard et al. (2002) привели пример, который происходит на уровне обучения предлогов и, в частности, «в», когда учитель может поднять коробку и сказать «Я смотрю на коробку», ученики могут понять, что «на «» означает «под», позже они могут произнести «кошка за столом» вместо «кошка под столом».

Ошибки избегания: эти ошибки возникают, когда учащийся не может применить определенные правила целевого языка только потому, что они считаются слишком сложными.

Ошибки перепроизводства: на ранних этапах изучения языка предполагается, что учащиеся еще не приобрели и не накопили удовлетворительных лингвистических знаний, которые могут позволить им использовать конечные правила целевого языка для получения бесконечных структуры, в большинстве случаев новички перепроизводят, таким образом, они часто повторяют определенную структуру.

Шаги

Согласно лингвисту Corder, следующие шаги в любом типичном исследовании EA:

- сбор образцов изучаемого языка

- выявление ошибок

- описание ошибок

- объяснение ошибок

- оценка / исправление ошибок

совокупность ошибок: характер и количество ошибок могут варьироваться в зависимости от того, состоят ли данные из естественных, спонтанное использование языка или осторожное использование языка.

Кордер (1973) различал два вида выявления: клиническое и экспериментальное. клиническое выявление включает в себя получение информатором данных любого рода, например, посредством общего интервью или написания сочинения. Экспериментальное выявление включает использование специального инструмента для выявления данных, содержащих лингвистические особенности, таких как серия изображений, которые были разработаны для выявления определенных особенностей.

Библиография

- Анефнаф. Z (2017) Изучение английского языка: лингвистические недостатки, факультет искусств и гуманитарных наук Саиса, USMBA, взято с https://www.academia.edu/33999467/English_Learning_in_Morocco_Linguistic_Flaws

- Хомский, Н. (1965). Аспекты теории синтаксиса. Кембридж, Массачусетс: MIT Press. С. 4

- Кордер, Пит. (1967). значимость ошибок учащегося. Международный обзор прикладной лингвистики, 161-170

- Дулай, Х., Берт, М., Крашен, С.Д. (1982). Язык два. Нью-Йорк: Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 150

- Эдже, Дж. (1989). Ошибки и исправления. Лондон: Лонгман. С. 26

- Фанг, X. Сюэ-мэй, J. (2007). Анализ ошибок и преподавание в классе EFL: Обзор образования в США и Китае, 4 (9), стр. 10–14.

- Хашим, А. (1999). Межъязыковое влияние на письменный английский малайских студентов: Journal of Modern Languages, 12, (1), pp. 59–76.

- Hendrickson, J.M. (1987). Исправление ошибок в обучении иностранному языку: последние теории, исследования и практика. В M.H. Лонг и Дж. К. Ричардс (ред.), Методология в TESOL: Книга чтений. Бостон: Хайнле и Хайнле. п. 357

- Норриш, Дж. (1983). Изучающие языки и их ошибки. Лондон: Macmillan Press. P. 7

- Richards, J. C. Schmidt, R. (2002). Словарь по языковому обучению и прикладной лингвистике (3-е изд.). Лондон: Лонгман.

- Ричардс Дж. К. и Роджерс Т. С. (2001). Подходы и методы обучения языкам. (2-е издание), Cambridge University Press: Кембридж, Великобритания. С. 153

См. Также

- Ошибка (лингвистика)

- Обработка ошибок (лингвистика)

- Приобретение второго языка

Ссылки

В лингвистике , согласно J. Richard et al., (2002), ошибка — это использование слова, речевого акта или грамматической единицы таким образом, что это кажется несовершенным и значительным из-за неполного обучения (184). Норриш (1983, стр. 7) рассматривает это как систематическое отклонение, которое происходит, когда учащийся не усвоил что-то и постоянно делает это неправильно. Однако попытки поместить ошибку в контекст всегда шли рука об руку как с изучением языка, так и с процессами овладения вторым языком. что учащийся еще не освоил или не продемонстрировал хорошо структурированную компетенциюна целевом языке.

Все определения, казалось, подчеркивали либо систематические отклонения, возникающие в процессе изучения языка, либо его указания на реальную ситуацию самого изучающего язык, что впоследствии поможет наблюдателю, будь то прикладной лингвист или, в частности, преподаватель языка, решить проблему. Что касается одного из подходов, представленных в Анализе ошибок (Anefnaf 2017), возникновение ошибок не только указывает на то, что учащийся еще что-то не усвоил, но также дает лингвисту представление о том, был ли примененный метод обучения эффективным или нет. его нужно изменить.

Согласно Кордеру (1976), ошибки важны по трем причинам, во-первых, для учителя, поскольку учащийся сообщает ему, если он проводит систематический анализ, насколько далеко продвинулся учащийся к этой цели и, следовательно, что ему остается сделать. учиться. Во-вторых, они предоставляют исследователю доказательства того, как язык изучается или усваивается, и какие стратегии или процедуры использует учащийся при открытии языка. В-третьих (и в некотором смысле это их самый важный аспект), они необходимы для самого учащегося, потому что совершение ошибок можно рассматривать как прием, который учащийся использует для обучения (стр. 167). Возникновение ошибок — это просто признаки «нынешней неадекватности наших методов обучения» (Corder 1976, p. 163).

Когда дело доходит до анализа ошибок и философии, существовало две школы мысли: первая, согласно Кордеру (1967), связывала совершение ошибок с методом обучения, утверждая, что если бы метод обучения был адекватным, ошибки бы не совершались. Вторая школа считала, что мы живем в несовершенном мире и что исправление ошибок — это нечто реальное, без которого прикладной лингвист не может обойтись, какой бы подход к обучению он ни использовал.

Ошибки против ошибок

Хомский (1965) дал четкое объяснение компетентности и производительности, на основе которого впоследствии станет возможным выявление ошибок и ошибок. Хомский заявил, что «таким образом мы проводим фундаментальное различие между компетентностью (знанием говорящим-слушающим своего ) и перформанс (фактическое употребление языка в конкретных ситуациях)» (1956, с. 4). Другими словами, ошибки рассматриваются как признаки неполного обучения и того, что говорящий или слушающий еще не накопил достаточных языковых знаний, которые могли бы позволить им избежать неправильного использования лингвистики. Связывание знаний с компетентностью было достаточно значительным, чтобы представить, что компетентность говорящего оценивается посредством ошибок, связанных с объемом лингвистических данных, с которыми он столкнулся, однако, представление, которое представляет собой фактическое использование языка, не отражает знания языка, которыми обладает говорящий. Согласно Дж. Ричарду и др. (2002), люди могут иметь возможность составить бесконечно длинное предложение, но когда они действительно пытаются использовать это знание («выполнить»), существует множество причин, по которым они ограничивают количество прилагательных, наречий и т. д. , и предложения в любом предложении (2002, 392).

Фактическое состояние говорящего каким-то образом влияет на его выступление, вызывая либо хорошее выступление, либо ошибки. Таким образом, совершенно очевидно, что существует какая-то взаимосвязь между компетентностью и производительностью; каким-то образом говорящий может хорошо выступать, если он уже имеет удовлетворительные лингвистические знания. В подтверждение этого Кордер (1967) упомянул, что ошибки не имеют значения для «процесса изучения языка» (стр. 167).

Подход к анализу ошибок

До появления подхода к анализу ошибок контрастный анализ был доминирующим подходом, используемым для обработки и концептуализации ошибок учащихся в 1950-х годах, этот подход часто шел рука об руку с концепцией интерференции L1 и именно с межъязыковым эффектом (Anefnaf Z. 2017) утверждалось, что основной причиной совершения ошибок в процессе изучения второго языка является L1, другими словами, языковой фон изучающих язык плохо влияет на производство на целевом языке или втором языке.

X. Fang и J. Xue-mei (2007) указали, что гипотеза сравнительного анализа утверждала, что основным препятствием для овладения вторым языком является вмешательство системы первого языка в систему второго языка и что научное структурное сравнение двух рассматриваемые языки позволили бы людям предсказывать и описывать, какие проблемы являются проблемами, а какие нет. Подход к анализу ошибок был подавлен и объявил об упадке контрастного анализа, который был эффективен только в фонологии; и, согласно J. Richard et al. (2002), EA развивался как раздел лингвистики в 1960-х годах, и стало известно, что родной язык не был основным и единственным источником ошибок, совершаемых учащимися. Кроме того, Хашим, А.

Цель ЭА согласно J. Richard et al. (2002), во-первых, определить стратегии, которые учащиеся используют при изучении языка, с точки зрения подходов и стратегий, используемых как в преподавании, так и в обучении. Во-вторых, попытаться выявить причины ошибок учащихся, т. е. исследовать мотивы совершения таких ошибок как первую попытку их искоренения. В-третьих, чтобы получить информацию об общих трудностях в изучении языка, как помощь в обучении или при подготовке учебных материалов,

Двумя основными причинами ошибок, выявленными в рамках подхода к анализу ошибок, являются межъязыковая ошибка, которая является ошибкой, допущенной лингвистическим фоном учащегося и вмешательством родного языка, и внутриязыковая ошибка, которая является ошибкой, совершаемой учащимися, когда они неправильно используют какую-либо цель. Языковые правила, учитывая, что причина ошибки лежит внутри и между самим целевым языком и ложным применением Учащимися определенных правил целевого языка.

Анализ ошибок в SLA был разработан в 1960-х годах Кордером и его коллегами. [1] Анализ ошибок (EA) был альтернативой контрастивному анализу , подходу, на который повлиял бихевиоризм, с помощью которого прикладные лингвисты стремились использовать формальные различия между первым и вторым языками учащихся для прогнозирования ошибок. Анализ ошибок показал, что сравнительный анализ был неспособен предсказать подавляющее большинство ошибок, хотя его более ценные аспекты были включены в изучение языкового переноса . Ключевой вывод анализа ошибок заключается в том, что многие ошибки учащегося возникают из-за того, что учащиеся делают ошибочные выводы о правилах нового языка.