I have:

foo/

├── __init__.py

├── bar.py

└── baz

├── __init__.py

└── alice.py

In bar.py, I import Alice, which is an empty class with nothing in it but the name attribute set to "Alice".

from baz.alice import Alice

a = Alice()

print(a.name)

This runs properly:

$ python foo/bar.py

Alice

But mypy complains:

$ mypy --version

mypy 0.910

$ mypy --strict .

foo/bar.py:1: error: Cannot find implementation or library stub for module named "baz.alice"

foo/bar.py:1: note: See https://mypy.readthedocs.io/en/stable/running_mypy.html#missing-imports

Found 1 error in 1 file (checked 6 source files)

Why is mypy complaining?

asked Aug 7, 2021 at 20:22

Tom HuibregtseTom Huibregtse

4731 gold badge5 silver badges12 bronze badges

4

mypy has its own search path for imports and does not resolve imports exactly as Python does and it isn’t able to find the baz.alice module. Check the documentation listed in the error message, specifically the section on How imports are found:

The rules for searching for a module

fooare as follows:The search looks in each of the directories in the search path (see

above) until a match is found.

- If a package named

foois found (i.e. a directory foo containing an__init__.pyor__init__.pyifile) that’s a match.- If a stub file named

foo.pyiis found, that’s a match.- If a Python module named

foo.pyis found, that’s a match.

The documentation also states that this in the section on Mapping file paths to modules:

For each file to be checked,

mypywill attempt to associate the file

(e.g.project/foo/bar/baz.py) with a fully qualified module name (e.g.

foo.bar.baz).

There’s a few ways to solve this particular issue:

- As paul41 mentioned in his comment, one option to solve this issue is by providing the fully qualified import (

from foo.baz.alice import Alice), and then running from a top-level module (a.pyfile in the root level). - You could add a

# type: ignoreto the import line. - You can edit the

MYPYPATHvariable to point to thefoodirectory:

(venv) (base) ➜ mypy foo/bar.py --strict

foo/bar.py:3: error: Cannot find implementation or library stub for module named "baz.alice"

foo/bar.py:3: note: See https://mypy.readthedocs.io/en/stable/running_mypy.html#missing-imports

Found 1 error in 1 file (checked 1 source file)

(venv) (base) ➜ export MYPYPATH=foo/

(venv) (base) ➜ mypy foo/bar.py --strict

Success: no issues found in 1 source file

answered Aug 8, 2021 at 3:19

2

Running mypy and managing imports

The :ref:`getting-started` page should have already introduced you

to the basics of how to run mypy — pass in the files and directories

you want to type check via the command line:

$ mypy foo.py bar.py some_directory

This page discusses in more detail how exactly to specify what files

you want mypy to type check, how mypy discovers imported modules,

and recommendations on how to handle any issues you may encounter

along the way.

If you are interested in learning about how to configure the

actual way mypy type checks your code, see our

:ref:`command-line` guide.

Specifying code to be checked

Mypy lets you specify what files it should type check in several different ways.

-

First, you can pass in paths to Python files and directories you

want to type check. For example:$ mypy file_1.py foo/file_2.py file_3.pyi some/directory

The above command tells mypy it should type check all of the provided

files together. In addition, mypy will recursively type check the

entire contents of any provided directories.For more details about how exactly this is done, see

:ref:`Mapping file paths to modules <mapping-paths-to-modules>`. -

Second, you can use the :option:`-m <mypy -m>` flag (long form: :option:`—module <mypy —module>`) to

specify a module name to be type checked. The name of a module

is identical to the name you would use to import that module

within a Python program. For example, running:$ mypy -m html.parser

…will type check the module

html.parser(this happens to be

a library stub).Mypy will use an algorithm very similar to the one Python uses to

find where modules and imports are located on the file system.

For more details, see :ref:`finding-imports`. -

Third, you can use the :option:`-p <mypy -p>` (long form: :option:`—package <mypy —package>`) flag to

specify a package to be (recursively) type checked. This flag

is almost identical to the :option:`-m <mypy -m>` flag except that if you give it

a package name, mypy will recursively type check all submodules

and subpackages of that package. For example, running:$ mypy -p html

…will type check the entire

htmlpackage (of library stubs).

In contrast, if we had used the :option:`-m <mypy -m>` flag, mypy would have type

checked justhtml‘s__init__.pyfile and anything imported

from there.Note that we can specify multiple packages and modules on the

command line. For example:$ mypy --package p.a --package p.b --module c

-

Fourth, you can also instruct mypy to directly type check small

strings as programs by using the :option:`-c <mypy -c>` (long form: :option:`—command <mypy —command>`)

flag. For example:$ mypy -c 'x = [1, 2]; print(x())'

…will type check the above string as a mini-program (and in this case,

will report thatlist[int]is not callable).

You can also use the :confval:`files` option in your :file:`mypy.ini` file to specify which

files to check, in which case you can simply run mypy with no arguments.

Reading a list of files from a file

Finally, any command-line argument starting with @ reads additional

command-line arguments from the file following the @ character.

This is primarily useful if you have a file containing a list of files

that you want to be type-checked: instead of using shell syntax like:

$ mypy $(cat file_of_files.txt)

you can use this instead:

$ mypy @file_of_files.txt

This file can technically also contain any command line flag, not

just file paths. However, if you want to configure many different

flags, the recommended approach is to use a

:ref:`configuration file <config-file>` instead.

Mapping file paths to modules

One of the main ways you can tell mypy what to type check

is by providing mypy a list of paths. For example:

$ mypy file_1.py foo/file_2.py file_3.pyi some/directory

This section describes how exactly mypy maps the provided paths

to modules to type check.

- Mypy will check all paths provided that correspond to files.

- Mypy will recursively discover and check all files ending in

.pyor

.pyiin directory paths provided, after accounting for

:option:`—exclude <mypy —exclude>`. - For each file to be checked, mypy will attempt to associate the file (e.g.

project/foo/bar/baz.py) with a fully qualified module name (e.g.

foo.bar.baz). The directory the package is in (project) is then

added to mypy’s module search paths.

How mypy determines fully qualified module names depends on if the options

:option:`—no-namespace-packages <mypy —no-namespace-packages>` and

:option:`—explicit-package-bases <mypy —explicit-package-bases>` are set.

-

If :option:`—no-namespace-packages <mypy —no-namespace-packages>` is set,

mypy will rely solely upon the presence of__init__.py[i]files to

determine the fully qualified module name. That is, mypy will crawl up the

directory tree for as long as it continues to find__init__.py(or

__init__.pyi) files.For example, if your directory tree consists of

pkg/subpkg/mod.py, mypy

would requirepkg/__init__.pyandpkg/subpkg/__init__.pyto exist in

order correctly associatemod.pywithpkg.subpkg.mod -

The default case. If :option:`—namespace-packages <mypy

—no-namespace-packages>` is on, but :option:`—explicit-package-bases <mypy

—explicit-package-bases>` is off, mypy will allow for the possibility that

directories without__init__.py[i]are packages. Specifically, mypy will

look at all parent directories of the file and use the location of the

highest__init__.py[i]in the directory tree to determine the top-level

package.For example, say your directory tree consists solely of

pkg/__init__.py

andpkg/a/b/c/d/mod.py. When determiningmod.py‘s fully qualified

module name, mypy will look atpkg/__init__.pyand conclude that the

associated module name ispkg.a.b.c.d.mod. -

You’ll notice that the above case still relies on

__init__.py. If

you can’t put an__init__.pyin your top-level package, but still wish to

pass paths (as opposed to packages or modules using the-por-m

flags), :option:`—explicit-package-bases <mypy —explicit-package-bases>`

provides a solution.With :option:`—explicit-package-bases <mypy —explicit-package-bases>`, mypy

will locate the nearest parent directory that is a member of theMYPYPATH

environment variable, the :confval:`mypy_path` config or is the current

working directory. Mypy will then use the relative path to determine the

fully qualified module name.For example, say your directory tree consists solely of

src/namespace_pkg/mod.py. If you run the following command, mypy

will correctly associatemod.pywithnamespace_pkg.mod:$ MYPYPATH=src mypy --namespace-packages --explicit-package-bases .

If you pass a file not ending in .py[i], the module name assumed is

__main__ (matching the behavior of the Python interpreter), unless

:option:`—scripts-are-modules <mypy —scripts-are-modules>` is passed.

Passing :option:`-v <mypy -v>` will show you the files and associated module

names that mypy will check.

How mypy handles imports

When mypy encounters an import statement, it will first

:ref:`attempt to locate <finding-imports>` that module

or type stubs for that module in the file system. Mypy will then

type check the imported module. There are three different outcomes

of this process:

- Mypy is unable to follow the import: the module either does not

exist, or is a third party library that does not use type hints. - Mypy is able to follow and type check the import, but you did

not want mypy to type check that module at all. - Mypy is able to successfully both follow and type check the

module, and you want mypy to type check that module.

The third outcome is what mypy will do in the ideal case. The following

sections will discuss what to do in the other two cases.

Missing imports

When you import a module, mypy may report that it is unable to follow

the import. This can cause errors that look like the following:

main.py:1: error: Skipping analyzing 'django': module is installed, but missing library stubs or py.typed marker main.py:2: error: Library stubs not installed for "requests" main.py:3: error: Cannot find implementation or library stub for module named "this_module_does_not_exist"

If you get any of these errors on an import, mypy will assume the type of that

module is Any, the dynamic type. This means attempting to access any

attribute of the module will automatically succeed:

# Error: Cannot find implementation or library stub for module named 'does_not_exist' import does_not_exist # But this type checks, and x will have type 'Any' x = does_not_exist.foobar()

This can result in mypy failing to warn you about errors in your code. Since

operations on Any result in Any, these dynamic types can propagate

through your code, making type checking less effective. See

:ref:`dynamic-typing` for more information.

The next sections describe what each of these errors means and recommended next steps; scroll to

the section that matches your error.

Missing library stubs or py.typed marker

If you are getting a Skipping analyzing X: module is installed, but missing library stubs or py.typed marker,

error, this means mypy was able to find the module you were importing, but no

corresponding type hints.

Mypy will not try inferring the types of any 3rd party libraries you have installed

unless they either have declared themselves to be

:ref:`PEP 561 compliant stub package <installed-packages>` (e.g. with a py.typed file) or have registered

themselves on typeshed, the repository

of types for the standard library and some 3rd party libraries.

If you are getting this error, try to obtain type hints for the library you’re using:

-

Upgrading the version of the library you’re using, in case a newer version

has started to include type hints. -

Searching to see if there is a :ref:`PEP 561 compliant stub package <installed-packages>`

corresponding to your third party library. Stub packages let you install

type hints independently from the library itself.For example, if you want type hints for the

djangolibrary, you can

install the django-stubs package. -

:ref:`Writing your own stub files <stub-files>` containing type hints for

the library. You can point mypy at your type hints either by passing

them in via the command line, by using the :confval:`files` or :confval:`mypy_path`

config file options, or by

adding the location to theMYPYPATHenvironment variable.These stub files do not need to be complete! A good strategy is to use

:ref:`stubgen <stubgen>`, a program that comes bundled with mypy, to generate a first

rough draft of the stubs. You can then iterate on just the parts of the

library you need.If you want to share your work, you can try contributing your stubs back

to the library — see our documentation on creating

:ref:`PEP 561 compliant packages <installed-packages>`.

If you are unable to find any existing type hints nor have time to write your

own, you can instead suppress the errors.

All this will do is make mypy stop reporting an error on the line containing the

import: the imported module will continue to be of type Any, and mypy may

not catch errors in its use.

-

To suppress a single missing import error, add a

# type: ignoreat the end of the

line containing the import. -

To suppress all missing import errors from a single library, add

a per-module section to your :ref:`mypy config file <config-file>` setting

:confval:`ignore_missing_imports` to True for that library. For example,

suppose your codebase

makes heavy use of an (untyped) library namedfoobar. You can silence

all import errors associated with that library and that library alone by

adding the following section to your config file:[mypy-foobar.*] ignore_missing_imports = True

Note: this option is equivalent to adding a

# type: ignoreto every

import offoobarin your codebase. For more information, see the

documentation about configuring

:ref:`import discovery <config-file-import-discovery>` in config files.

The.*afterfoobarwill ignore imports offoobarmodules

and subpackages in addition to thefoobartop-level package namespace. -

To suppress all missing import errors for all libraries in your codebase,

invoke mypy with the :option:`—ignore-missing-imports <mypy —ignore-missing-imports>` command line flag or set

the :confval:`ignore_missing_imports`

config file option to True

in the global section of your mypy config file:[mypy] ignore_missing_imports = True

We recommend using this approach only as a last resort: it’s equivalent

to adding a# type: ignoreto all unresolved imports in your codebase.

Library stubs not installed

If mypy can’t find stubs for a third-party library, and it knows that stubs exist for

the library, you will get a message like this:

main.py:1: error: Library stubs not installed for "yaml" main.py:1: note: Hint: "python3 -m pip install types-PyYAML" main.py:1: note: (or run "mypy --install-types" to install all missing stub packages)

You can resolve the issue by running the suggested pip commands.

If you’re running mypy in CI, you can ensure the presence of any stub packages

you need the same as you would any other test dependency, e.g. by adding them to

the appropriate requirements.txt file.

Alternatively, add the :option:`—install-types <mypy —install-types>`

to your mypy command to install all known missing stubs:

mypy --install-types

This is slower than explicitly installing stubs, since it effectively

runs mypy twice — the first time to find the missing stubs, and

the second time to type check your code properly after mypy has

installed the stubs. It also can make controlling stub versions harder,

resulting in less reproducible type checking.

By default, :option:`—install-types <mypy —install-types>` shows a confirmation prompt.

Use :option:`—non-interactive <mypy —non-interactive>` to install all suggested

stub packages without asking for confirmation and type check your code:

If you’ve already installed the relevant third-party libraries in an environment

other than the one mypy is running in, you can use :option:`—python-executable

<mypy —python-executable>` flag to point to the Python executable for that

environment, and mypy will find packages installed for that Python executable.

If you’ve installed the relevant stub packages and are still getting this error,

see the :ref:`section below <missing-type-hints-for-third-party-library>`.

Cannot find implementation or library stub

If you are getting a Cannot find implementation or library stub for module

error, this means mypy was not able to find the module you are trying to

import, whether it comes bundled with type hints or not. If you are getting

this error, try:

-

Making sure your import does not contain a typo.

-

If the module is a third party library, making sure that mypy is able

to find the interpreter containing the installed library.For example, if you are running your code in a virtualenv, make sure

to install and use mypy within the virtualenv. Alternatively, if you

want to use a globally installed mypy, set the

:option:`—python-executable <mypy —python-executable>` command

line flag to point the Python interpreter containing your installed

third party packages.You can confirm that you are running mypy from the environment you expect

by running it likepython -m mypy .... You can confirm that you are

installing into the environment you expect by running pip like

python -m pip ....

-

Reading the :ref:`finding-imports` section below to make sure you

understand how exactly mypy searches for and finds modules and modify

how you’re invoking mypy accordingly. -

Directly specifying the directory containing the module you want to

type check from the command line, by using the :confval:`mypy_path`

or :confval:`files` config file options,

or by using theMYPYPATHenvironment variable.Note: if the module you are trying to import is actually a submodule of

some package, you should specify the directory containing the entire package.

For example, suppose you are trying to add the modulefoo.bar.baz

which is located at~/foo-project/src/foo/bar/baz.py. In this case,

you must runmypy ~/foo-project/src(or set theMYPYPATHto

~/foo-project/src.

How imports are found

When mypy encounters an import statement or receives module

names from the command line via the :option:`—module <mypy —module>` or :option:`—package <mypy —package>`

flags, mypy tries to find the module on the file system similar

to the way Python finds it. However, there are some differences.

First, mypy has its own search path.

This is computed from the following items:

- The

MYPYPATHenvironment variable

(a list of directories, colon-separated on UNIX systems, semicolon-separated on Windows). - The :confval:`mypy_path` config file option.

- The directories containing the sources given on the command line

(see :ref:`Mapping file paths to modules <mapping-paths-to-modules>`). - The installed packages marked as safe for type checking (see

:ref:`PEP 561 support <installed-packages>`) - The relevant directories of the

typeshed repo.

Note

You cannot point to a stub-only package (PEP 561) via the MYPYPATH, it must be

installed (see :ref:`PEP 561 support <installed-packages>`)

Second, mypy searches for stub files in addition to regular Python files

and packages.

The rules for searching for a module foo are as follows:

- The search looks in each of the directories in the search path

(see above) until a match is found. - If a package named

foois found (i.e. a directory

foocontaining an__init__.pyor__init__.pyifile)

that’s a match. - If a stub file named

foo.pyiis found, that’s a match. - If a Python module named

foo.pyis found, that’s a match.

These matches are tried in order, so that if multiple matches are found

in the same directory on the search path

(e.g. a package and a Python file, or a stub file and a Python file)

the first one in the above list wins.

In particular, if a Python file and a stub file are both present in the

same directory on the search path, only the stub file is used.

(However, if the files are in different directories, the one found

in the earlier directory is used.)

Setting :confval:`mypy_path`/MYPYPATH is mostly useful in the case

where you want to try running mypy against multiple distinct

sets of files that happen to share some common dependencies.

For example, if you have multiple projects that happen to be

using the same set of work-in-progress stubs, it could be

convenient to just have your MYPYPATH point to a single

directory containing the stubs.

Following imports

Mypy is designed to :ref:`doggedly follow all imports <finding-imports>`,

even if the imported module is not a file you explicitly wanted mypy to check.

For example, suppose we have two modules mycode.foo and mycode.bar:

the former has type hints and the latter does not. We run

:option:`mypy -m mycode.foo <mypy -m>` and mypy discovers that mycode.foo imports

mycode.bar.

How do we want mypy to type check mycode.bar? Mypy’s behaviour here is

configurable — although we strongly recommend using the default —

by using the :option:`—follow-imports <mypy —follow-imports>` flag. This flag

accepts one of four string values:

-

normal(the default, recommended) follows all imports normally and

type checks all top level code (as well as the bodies of all

functions and methods with at least one type annotation in

the signature). -

silentbehaves in the same way asnormalbut will

additionally suppress any error messages. -

skipwill not follow imports and instead will silently

replace the module (and anything imported from it) with an

object of typeAny. -

errorbehaves in the same way asskipbut is not quite as

silent — it will flag the import as an error, like this:main.py:1: note: Import of "mycode.bar" ignored main.py:1: note: (Using --follow-imports=error, module not passed on command line)

If you are starting a new codebase and plan on using type hints from

the start, we recommend you use either :option:`—follow-imports=normal <mypy —follow-imports>`

(the default) or :option:`—follow-imports=error <mypy —follow-imports>`. Either option will help

make sure you are not skipping checking any part of your codebase by

accident.

If you are planning on adding type hints to a large, existing code base,

we recommend you start by trying to make your entire codebase (including

files that do not use type hints) pass under :option:`—follow-imports=normal <mypy —follow-imports>`.

This is usually not too difficult to do: mypy is designed to report as

few error messages as possible when it is looking at unannotated code.

Only if doing this is intractable, we recommend passing mypy just the files

you want to type check and use :option:`—follow-imports=silent <mypy —follow-imports>`. Even if

mypy is unable to perfectly type check a file, it can still glean some

useful information by parsing it (for example, understanding what methods

a given object has). See :ref:`existing-code` for more recommendations.

We do not recommend using skip unless you know what you are doing:

while this option can be quite powerful, it can also cause many

hard-to-debug errors.

Adjusting import following behaviour is often most useful when restricted to

specific modules. This can be accomplished by setting a per-module

:confval:`follow_imports` config option.

Sometimes, MyPy will complains that it cannot do typechecks for installed package.

… error: Cannot find implementation or library stub for module named ‘…’

See also Missing imports in the MyPu docs.

Missing type hints for built-in module

- Update and rerun MyPy.

- File a bug report.

Missing type hints for third party library

If the package you installed does not have type annotations built in, then you can do one of the following.

- Upgrade the package.

- Find stubs that someone wrote for the package and has shared.

- Write your own, at least just for the portion of the package that you need.

- Add an ignore configuration.

Read on below to see those in more detail.

Upgrade

Upgrade the version of the library you’re using, in case a newer version has started to include type hints.

Find subs

Search to see if there is a PEP 561 compliant stub package, corresponding to your third party library.

Stub packages let you install type hints independently from the library itself.

For example, if you want type hints for the

djangolibrary, you can install thedjango-stubspackage.

Write stubs

Write your own stub files containing type hints for the library.

You can point mypy at your type hints either by passing them in via the command line, by using the files or mypy_path config file options, or by adding the location to the MYPYPATH environment variable.

These stub files do not need to be complete! A good strategy is to use stubgen, a program that comes bundled with mypy, to generate a first rough draft of the stubs. You can then iterate on just the parts of the library you need.

- stubgen in the MyPy docs

With MyPy installed, you can run:

It will generate out/foo.pyi. You should place this in the same directory as the script.

See Specifiying what to stub

See also these to to automatically annotate legacy code, according to the docs:

- MonkeyType

- PyAnnotate

Configure to ignore

- To suppress a single missing import error, add this at the end of the line containing the import:

import foo # type: ignoreHandle multi-line import. Note putting the comment after closing bracket doesn’t work.

from foo.bar import ( # type: ignore FIZZ, BUZZ ) - Add to your MyPy Config file for package

foo.[mypy-foo.*] ignore_missing_imports = TrueOr

[mypy-foo] ignore_missing_imports = True - Ignore across libraries:

[mypy] ignore_missing_imports = True

Read the original on my personal blog

Mypy is a static type checker for Python. It acts as a linter, that allows you to write statically typed code, and verify the soundness of your types.

All mypy does is check your type hints. It’s not like TypeScript, which needs to be compiled before it can work. All mypy code is valid Python, no compiler needed.

This gives us the advantage of having types, as you can know for certain that there is no type-mismatch in your code, just as you can in typed, compiled languages like C++ and Java, but you also get the benefit of being Python 🐍✨ (you also get other benefits like null safety!)

For a more detailed explanation on what are types useful for, head over to the blog I wrote previously: Does Python need types?

This article is going to be a deep dive for anyone who wants to learn about mypy, and all of its capabilities.

If you haven’t noticed the article length, this is going to be long. So grab a cup of your favorite beverage, and let’s get straight into it.

Index

-

Setting up mypy

- Using mypy in the terminal

- Using mypy in VSCode

- Primitive types

- Collection types

- Type debugging — Part 1

- Union and Optional

- Any type

-

Miscellaneous types

- Tuple

- TypedDict

- Literal

- Final

- NoReturn

- Typing classes

- Typing namedtuples

- Typing decorators

- Typing generators

- Typing

*argsand**kwargs - Duck types

- Function overloading with

@overload Typetype- Typing pre-existing projects

- Type debugging — Part 2

- Typing context managers

- Typing async functions

-

Making your own Generics

- Generic functions

- Generic classes

- Generic types

- Advanced/Recursive type checking with

Protocol - Further learning

Setting up mypy

All you really need to do to set it up is pip install mypy.

Using mypy in the terminal

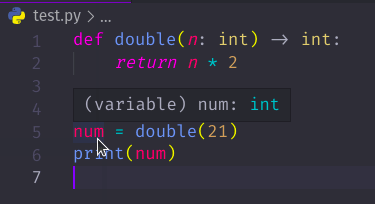

Let’s create a regular python file, and call it test.py:

This doesn’t have any type definitions yet, but let’s run mypy over it to see what it says.

$ mypy test.py

Success: no issues found in 1 source file

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

🤨

Don’t worry though, it’s nothing unexpected. As explained in my previous article, mypy doesn’t force you to add types to your code. But, if it finds types, it will evaluate them.

This can definitely lead to mypy missing entire parts of your code just because you accidentally forgot to add types.

Thankfully, there’s ways to customise mypy to tell it to always check for stuff:

$ mypy --disallow-untyped-defs test.py

test.py:1: error: Function is missing a return type annotation

Found 1 error in 1 file (checked 1 source file)

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

And now it gave us the error we wanted.

There are a lot of these --disallow- arguments that we should be using if we are starting a new project to prevent such mishaps, but mypy gives us an extra powerful one that does it all: --strict

$ mypy --strict test.py

test.py:1: error: Function is missing a return type annotation

test.py:4: error: Call to untyped function "give_number" in typed context

Found 2 errors in 1 file (checked 1 source file)

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

This gave us even more information: the fact that we’re using give_number in our code, which doesn’t have a defined return type, so that piece of code also can have unintended issues.

TL;DR: for starters, use

mypy --strict filename.py

Using mypy in VSCode

VSCode has pretty good integration with mypy. All you need to get mypy working with it is to add this to your settings.json:

...

"python.linting.mypyEnabled": true,

"python.linting.mypyArgs": [

"--ignore-missing-imports",

"--follow-imports=silent",

"--show-column-numbers",

"--strict"

],

...

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Now opening your code folder in python should show you the exact same errors in the «Problems» pane:

Also, if you’re using VSCode I’ll highly suggest installing Pylance from the Extensions panel, it’ll help a lot with tab-completion and getting better insight into your types.

Okay, now on to actually fixing these issues.

Primitive types

The most fundamental types that exist in mypy are the primitive types. To name a few:

intstrfloat-

bool

…

Notice a pattern?

Yup. These are the same exact primitive Python data types that you’re familiar with.

And these are actually all we need to fix our errors:

All we’ve changed is the function’s definition in def:

What this says is «function double takes an argument n which is an int, and the function returns an int.

And running mypy now:

$ mypy --strict test.py

Success: no issues found in 1 source file

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Congratulations, you’ve just written your first type-checked Python program 🎉

We can run the code to verify that it indeed, does work:

$ python test.py

42

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

I should clarify, that mypy does all of its type checking without ever running the code. It is what’s called a static analysis tool (this static is different from the static in «static typing»), and essentially what it means is that it works not by running your python code, but by evaluating your program’s structure. What this means is, if your program does interesting things like making API calls, or deleting files on your system, you can still run mypy over your files and it will have no real-world effect.

What is interesting to note, is that we have declared num in the program as well, but we never told mypy what type it is going to be, and yet it still worked just fine.

We could tell mypy what type it is, like so:

And mypy would be equally happy with this as well. But we don’t have to provide this type, because mypy knows its type already. Because double is only supposed to return an int, mypy inferred it:

And inference is cool. For 80% of the cases, you’ll only be writing types for function and method definitions, as we did in the first example. One notable exception to this is «empty collection types», which we will discuss now.

Collection types

Collection types are how you’re able to add types to collections, such as «a list of strings», or «a dictionary with string keys and boolean values», and so on.

Some collection types include:

ListDictSetDefaultDictDequeCounter

Now these might sound very familiar, these aren’t the same as the builtin collection types (more on that later).

These are all defined in the typing module that comes built-in with Python, and there’s one thing that all of these have in common: they’re generic.

I have an entire section dedicated to generics below, but what it boils down to is that «with generic types, you can pass types inside other types». Here’s how you’d use collection types:

This tells mypy that nums should be a list of integers (List[int]), and that average returns a float.

Here’s a couple more examples:

Remember when I said that empty collections is one of the rare cases that need to be typed? This is because there’s no way for mypy to infer the types in that case:

Since the set has no items to begin with, mypy can’t statically infer what type it should be.

PS:

Small note, if you try to run mypy on the piece of code above, it’ll actually succeed. It’s because the mypy devs are smart, and they added simple cases of look-ahead inference. Meaning, new versions of mypy can figure out such types in simple cases. Keep in mind that it doesn’t always work.

To fix this, you can manually add in the required type:

Note: Starting from Python 3.7, you can add a future import,

from __future__ import annotationsat the top of your files, which will allow you to use the builtin types as generics, i.e. you can uselist[int]instead ofList[int]. If you’re using Python 3.9 or above, you can use this syntax without needing the__future__import at all. However, there are some edge cases where it might not work, so in the meantime I’ll suggest using thetyping.Listvariants. This is detailed in PEP 585.

Type debugging — Part 1

Let’s say you’re reading someone else’s — or your own past self’s — code, and it’s not really apparent what the type of a variable is. The code is using a lot of inference, and it’s using some builtin methods that you don’t exactly remember how they work, bla bla.

Thankfully mypy lets you reveal the type of any variable by using reveal_type:

Running mypy on this piece of code gives us:

$ mypy --strict test.py

test.py:12: note: Revealed type is 'builtins.int'

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Ignore the builtins for now, it’s able to tell us that counts here is an int.

Cool, right? You don’t need to rely on an IDE or VSCode, to use hover to check the types of a variable. A simple terminal and mypy is all you need. (although VSCode internally uses a similar process to this to get all type informations)

However, some of you might be wondering where reveal_type came from. We didn’t import it from typing… is it a new builtin? Is that even valid in python?

And sure enough, if you try to run the code:

py test.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/home/tushar/code/test/test.py", line 12, in <module>

reveal_type(counts)

NameError: name 'reveal_type' is not defined

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

reveal_type is a special «mypy function». Since python doesn’t know about types (type annotations are ignored at runtime), only mypy knows about the types of variables when it runs its type checking. So, only mypy can work with reveal_type.

All this means, is that you should only use reveal_type to debug your code, and remove it when you’re done debugging.

Union and Optional

So far, we have only seen variables and collections that can hold only one type of value. But what about this piece of code?

What’s the type of fav_color in this code?

Let’s try to do a reveal_type:

BTW, since this function has no return statement, its return type is

None.

Running mypy on this:

$ mypy test.py

test.py:5: note: Revealed type is 'Union[builtins.str*, None]'

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

And we get one of our two new types: Union. Specifically, Union[str, None].

All this means, is that fav_color can be one of two different types, either str, or None.

And unions are actually very important for Python, because of how Python does polymorphism. Here’s a simpler example:

$ python test.py

Hi!

This is a test

of polymorphism

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Now let’s add types to it, and learn some things by using our friend reveal_type:

Can you guess the output of the reveal_types?

$ mypy test.py

test.py:4: note: Revealed type is 'Union[builtins.str, builtins.list[builtins.str]]'

test.py:8: note: Revealed type is 'builtins.list[builtins.str]'

test.py:11: note: Revealed type is 'builtins.str'

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Mypy is smart enough, where if you add an isinstance(...) check to a variable, it will correctly assume that the type inside that block is narrowed to that type.

In our case, item was correctly identified as List[str] inside the isinstance block, and str in the else block.

This is an extremely powerful feature of mypy, called Type narrowing.

Now, here’s a more contrived example, a tpye-annotated Python implementation of the builtin function abs:

And that’s everything you need to know about Union.

… so what’s Optional you ask?

Well, Union[X, None] seemed to occur so commonly in Python, that they decided it needs a shorthand. Optional[str] is just a shorter way to write Union[str, None].

Any type

If you ever try to run reveal_type inside an untyped function, this is what happens:

$ mypy test.py

test.py:6: note: Revealed type is 'Any'

test.py:6: note: 'reveal_type' always outputs 'Any' in unchecked functions

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

The revealed type is told to be Any.

Any just means that anything can be passed here. Whatever is passed, mypy should just accept it. In other words, Any turns off type checking.

Of course, this means that if you want to take advantage of mypy, you should avoid using Any as much as you can.

But since Python is inherently a dynamically typed language, in some cases it’s impossible for you to know what the type of something is going to be. For such cases, you can use Any. For example:

You can also use Any as a placeholder value for something while you figure out what it should be, to make mypy happy in the meanwhile. But make sure to get rid of the Any if you can .

Miscellaneous types

Tuple

You might think of tuples as an immutable list, but Python thinks of it in a very different way.

Tuples are different from other collections, as they are essentially a way to represent a collection of data points related to an entity, kinda similar to how a C struct is stored in memory. While other collections usually represent a bunch of objects, tuples usually represent a single object.

A good example is sqlite:

Tuples also come in handy when you want to return multiple values from a function, for example:

Because of these reasons, tuples tend to have a fixed length, with each index having a specific type. (Our sqlite example had an array of length 3 and types int, str and int respectively.

Here’s how you’d type a tuple:

However, sometimes you do have to create variable length tuples. You can use the Tuple[X, ...] syntax for that.

The ... in this case simply means there’s a variable number of elements in the array, but their type is X. For example:

TypedDict

A TypedDict is a dictionary whose keys are always string, and values are of the specified type. At runtime, it behaves exactly like a normal dictionary.

By default, all keys must be present in a TypedDict. It is possible to override this by specifying total=False.

Literal

A Literal represents the type of a literal value. You can use it to constrain already existing types like str and int, to just some specific values of them. Like so:

$ mypy test.py

test.py:7: error: Argument 1 to "i_only_take_5" has incompatible type "Literal[6]"; expected "Literal[5]"

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

This has some interesting use-cases. A notable one is to use it in place of simple enums:

$ mypy test.py

test.py:8: error: Argument 1 to "make_request" has incompatible type "Literal['DLETE']"; expected "Union[Literal['GET'], Literal['POST'], Literal['DELETE']]"

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Oops, you made a typo in 'DELETE'! Don’t worry, mypy saved you an hour of debugging.

Final

Final is an annotation that declares a variable as final. What that means that the variable cannot be re-assigned to. This is similar to final in Java and const in JavaScript.

NoReturn

NoReturn is an interesting type. It’s rarely ever used, but it still needs to exist, for that one time where you might have to use it.

There are cases where you can have a function that might never return. Two possible reasons that I can think of for this are:

- The function always raises an exception, or

- The function is an infinite loop.

Here’s an example of both:

Note that in both these cases, typing the function as -> None will also work. But if you intend for a function to never return anything, you should type it as NoReturn, because then mypy will show an error if the function were to ever have a condition where it does return.

For example, if you edit while True: to be while False: or while some_condition() in the first example, mypy will throw an error:

$ mypy test.py

test.py:6: error: Implicit return in function which does not return

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Typing classes

All class methods are essentially typed just like regular functions, except for self, which is left untyped. Here’s a simple Stack class:

If you’ve never seen the

{x!r}syntax inside f-strings, it’s a way to use therepr()of a value. For more information, pyformat.info is a very good resource for learning Python’s string formatting features.

There’s however, one caveat to typing classes: You can’t normally access the class itself inside the class’ function declarations (because the class hasn’t been finished declaring itself yet, because you’re still declaring its methods).

So something like this isn’t valid Python:

$ mypy --strict test.py

Success: no issues found in 1 source file

$ python test.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/home/tushar/code/test/test.py", line 11, in <module>

class MyClass:

File "/home/tushar/code/test/test.py", line 15, in MyClass

def copy(self) -> MyClass:

NameError: name 'MyClass' is not defined

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

There’s two ways to fix this:

- Turn the classname into a string: The creators of PEP 484 and Mypy knew that such cases exist where you might need to define a return type which doesn’t exist yet. So, mypy is able to check types if they’re wrapped in strings.

- Use

from __future__ import annotations. What this does, is turn on a new feature in Python called «postponed evaluation of type annotations». This essentially makes Python treat all type annotations as strings, storing them in the internal__annotations__attribute. Details are described in PEP 563.

Starting with Python 3.11, the Postponed evaluation behaviour will become default, and you won’t need to have the

__future__import anymore.

Typing namedtuples

namedtuples are a lot like tuples, except every index of their fields is named, and they have some syntactic sugar which allow you to access its properties like attributes on an object:

Since the underlying data structure is a tuple, and there’s no real way to provide any type information to namedtuples, by default this will have a type of Tuple[Any, Any, Any].

To combat this, Python has added a NamedTuple class which you can extend to have the typed equivalent of the same:

Inner workings of NamedTuple:

If you’re curious how NamedTuple works under the hood: age: int is a type declaration, without any assignment (like age : int = 5).

Type declarations inside a function or class don’t actually define the variable, but they add the type annotation to that function or class’ metadata, in the form of a dictionary entry, into x.__annotations__.

Doing print(ishan.__annotations__) in the code above gives us {'name': <class 'str'>, 'age': <class 'int'>, 'bio': <class 'str'>}.

typing.NamedTuple uses these annotations to create the required tuple.

Typing decorators

Decorators are a fairly advanced, but really powerful feature of Python. If you don’t know anything about decorators, I’d recommend you to watch Anthony explains decorators, but I’ll explain it in brief here as well.

A decorator is essentially a function that wraps another function. Decorators can extend the functionalities of pre-existing functions, by running other side-effects whenever the original function is called. A decorator decorates a function by adding new functionality.

A simple example would be to monitor how long a function takes to run:

To be able to type this, we’d need a way to be able to define the type of a function. That way is called Callable.

Callable is a generic type with the following syntax:

Callable[[<list of argument types>], <return type>]

The types of a function’s arguments goes into the first list inside Callable, and the return type follows after. A few examples:

Here’s how you’d implenent the previously-shown time_it decorator:

Note:

Callableis what’s called a Duck Type. What it means, is that you can create your own custom object, and make it a validCallable, by implementing the magic method called__call__. I have a dedicated section where I go in-depth about duck types ahead.

Typing generators

Generators are also a fairly advanced topic to completely cover in this article, and you can watch

Anthony explains generators if you’ve never heard of them. A brief explanation is this:

Generators are a bit like perpetual functions. Instead of returning a value a single time, they yield values out of them, which you can iterate over. When you yield a value from an iterator, its execution pauses. But when another value is requested from the generator, it resumes execution from where it was last paused. When the generator function returns, the iterator stops.

Here’s an example:

To add type annotations to generators, you need typing.Generator. The syntax is as follows:

Generator[yield_type, throw_type, return_type]

With that knowledge, typing this is fairly straightforward:

Since we’re not raising any errors in the generator, throw_type is None. And although the return type is int which is correct, we’re not really using the returned value anyway, so you could use Generator[str, None, None] as well, and skip the return part altogether.

Typing *args and **kwargs

*args and **kwargs is a feature of python that lets you pass any number of arguments and keyword arguments to a function (that’s what the name args and kwargs stands for, but these names are just convention, you can name the variables anything). Anthony explains args and kwargs

All the extra arguments passed to *args get turned into a tuple, and kewyord arguments turn into a dictionay, with the keys being the string keywords:

Since the *args will always be of typle Tuple[X], and **kwargs will always be of type Dict[str, X], we only need to provide one type value X to type them. Here’s a practical example:

Duck types

Duck types are a pretty fundamental concept of python: the entirety of the Python object model is built around the idea of duck types.

Quoting Alex Martelli:

«You don’t really care for IS-A — you really only care for BEHAVES-LIKE-A-(in-this-specific-context), so, if you do test, this behaviour is what you should be testing for.»

What it means is that Python doesn’t really care what the type of an object is, but rather how does it behave.

I had a short note above in typing decorators that mentioned duck typing a function with __call__, now here’s the actual implementation:

PS.

> Running mypy over the above code is going to give a cryptic error about «Special Forms», don’t worry about that right now, we’ll fix this in the Protocol section. All I’m showing right now is that the Python code works.

You can see that Python agrees that both of these functions are «Call-able», i.e. you can call them using the x() syntax. (this is why the type is called Callable, and not something like Function)

What duck types provide you is to be able to define your function parameters and return types not in terms of concrete classes, but in terms of how your object behaves, giving you a lot more flexibility in what kinds of things you can utilize in your code now, and also allows much easier extensibility in the future without making «breaking changes».

A simple example here:

Running this code with Python works just fine. But running mypy over this gives us the following error:

$ mypy test.py

test.py:12: error: Argument 1 to "count_non_empty_strings" has incompatible type "ValuesView[str]"; expected "List[str]"

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

ValuesView is the type when you do dict.values(), and although you could imagine it as a list of strings in this case, it’s not exactly the type List.

In fact, none of the other sequence types like tuple or set are going to work with this code. You could patch it for some of the builtin types by doing strings: Union[List[str], Set[str], ...] and so on, but just how many types will you add? And what about third party/custom types?

The correct solution here is to use a Duck Type (yes, we finally got to the point). The only thing we want to ensure in this case is that the object can be iterated upon (which in Python terms means that it implements the __iter__ magic method), and the right type for that is Iterable:

And now mypy is happy with our code.

There are many, many of these duck types that ship within Python’s typing module, and a few of them include:

-

Sequencefor defining things that can be indexed and reversed, likeListandTuple. -

MutableMapping, for when you have a key-value pair kind-of data structure, likedict, but also others likedefaultdict,OrderedDictandCounterfrom the collections module. -

Collection, if all you care about is having a finite number of items in your data structure, eg. aset,list,dict, or anything from the collections module.

If you haven’t already at this point, you should really look into how python’s syntax and top level functions hook into Python’s object model via

__magic_methods__, for essentially all of Python’s behaviour. The documentation for it is right here, and there’s an excellent talk by James Powell that really dives deep into this concept in the beginning.

Function overloading with @overload

Let’s write a simple add function that supports int‘s and float‘s:

The implementation seems perfectly fine… but mypy isn’t happy with it:

$ test.py:15: error: No overload variant of "__getitem__" of "list" matches argument type "float"

test.py:15: note: Possible overload variants:

test.py:15: note: def __getitem__(self, int) -> int

test.py:15: note: def __getitem__(self, slice) -> List[int]

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

What mypy is trying to tell us here, is that in the line:

print(joined_list[last_index])

last_index could be of type float. And checking with reveal_type, that definitely is the case:

And since it could, mypy won’t allow you to use a possible float value to index a list, because that will error out.

One thing we could do is do an isinstance assertion on our side to convince mypy:

But this will be pretty cumbersome to do at every single place in our code where we use add with int‘s. Also we as programmers know, that passing two int‘s will only ever return an int. But how do we tell mypy that?

Answer: use @overload. The syntax basically replicates what we wanted to say in the paragraph above:

And now mypy knows that add(3, 4) returns an int.

Note that Python has no way to ensure that the code actually always returns an

intwhen it getsintvalues. It’s your job as the programmer providing these overloads, to verify that they are correct. This is why in some cases, usingassert isinstance(...)could be better than doing this, but for most cases@overloadworks fine.Also, in the overload definitions

-> int: ..., the...at the end is a convention for when you provide type stubs for functions and classes, but you could technically write anything as the function body:pass,42, etc. It’ll be ignored either way.

Another good overload example is this:

Type type

Type is a type used to type classes. It derives from python’s way of determining the type of an object at runtime:

You’d usually use

issubclass(x, int)instead oftype(x) == intto check for behaviour, but sometimes knowing the exact type can help, for eg. in optimizations.

Since type(x) returns the class of x, the type of a class C is Type[C]:

We had to use

Anyin 3 places here, and 2 of them can be eliminated by using generics, and we’ll talk about it later on.

Typing pre-existing projects

If you need it, mypy gives you the ability to add types to your project without ever modifying the original source code. It’s done using what’s called «stub files».

Stub files are python-like files, that only contain type-checked variable, function, and class definitions. It’s kindof like a mypy header file.

You can make your own type stubs by creating a .pyi file:

Now, run mypy on the current folder (make sure you have an __init__.py file in the folder, if not, create an empty one).

$ ls

__init__.py test.py test.pyi

$ mypy --strict .

Success: no issues found in 2 source files

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Type debugging — Part 2

Since we are on the topic of projects and folders, let’s discuss another one of pitfalls that you can find yourselves in when using mypy.

The first one is PEP 420

A fact that took me some time to realise, was that for mypy to be able to type-check a folder, the folder must be a module.

Let’s say you find yourself in this situatiion:

$ tree

.

├── test.py

└── utils

└── foo.py

1 directory, 2 files

$ cat test.py

from utils.foo import average

print(average(3, 4))

$ cat utils/foo.py

def average(x: int, y: int) -> float:

return float(x + y) / 2

$ py test.py

3.5

$ mypy test.py

test.py:1: error: Cannot find implementation or library stub for module named 'utils.foo'

test.py:1: note: See https://mypy.readthedocs.io/en/latest/running_mypy.html#missing-imports

Found 1 error in 1 file (checked 1 source file)

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

What’s the problem? Python is able to find utils.foo no problems, why can’t mypy?

The error is very cryptic, but the thing to focus on is the word «module» in the error. utils.foo should be a module, and for that, the utils folder should have an __init__.py, even if it’s empty.

$ tree

.

├── test.py

└── utils

├── foo.py

└── __init__.py

1 directory, 3 files

$ mypy test.py

Success: no issues found in 1 source file

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Now, the same issue re-appears if you’re installing your package via pip, because of a completely different reason:

$ tree ..

..

├── setup.py

├── src

│ └── mypackage

│ ├── __init__.py

│ └── utils

│ ├── foo.py

│ └── __init__.py

└── test

└── test.py

4 directories, 5 files

$ cat ../setup.py

from setuptools import setup, find_packages

setup(

name="mypackage",

packages = find_packages('src'),

package_dir = {"":"src"}

)

$ pip install ..

[...]

successfully installed mypackage-0.0.0

$ cat test.py

from mypackage.utils.foo import average

print(average(3, 4))

$ python test.py

3.5

$ mypy test.py

test.py:1: error: Cannot find implementation or library stub for module named 'mypackage.utils.foo'

test.py:1: note: See https://mypy.readthedocs.io/en/latest/running_mypy.html#missing-imports

Found 1 error in 1 file (checked 1 source file)

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

What now? Every folder has an __init__.py, it’s even installed as a pip package and the code runs, so we know that the module structure is right. What gives?

Well, turns out that pip packages aren’t type checked by mypy by default. This behaviour exists because type definitions are opt-in by default. Python packages aren’t expected to be type-checked, because mypy types are completely optional. If mypy were to assume every package has type hints, it would show possibly dozens of errors because a package doesn’t have proper types, or used type hints for something else, etc.

To opt-in for type checking your package, you need to add an empty py.typed file into your package’s root directory, and also include it as metadata in your setup.py:

$ tree ..

..

├── setup.py

├── src

│ └── mypackage

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── py.typed

│ └── utils

│ ├── foo.py

│ └── __init__.py

└── test

└── test.py

4 directories, 6 files

$ cat ../setup.py

from setuptools import setup, find_packages

setup(

name="mypackage",

packages = find_packages(

where = 'src',

),

package_dir = {"":"src"},

package_data={

"mypackage": ["py.typed"],

}

)

$ mypy test.py

Success: no issues found in 1 source file

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

There’s yet another third pitfall that you might encounter sometimes, which is if a.py declares a class MyClass, and it imports stuff from a file b.py which requires to import MyClass from a.py for type-checking purposes.

This creates an import cycle, and Python gives you an ImportError. To avoid this, simple add an if typing.TYPE_CHECKING: block to the import statement in b.py, since it only needs MyClass for type checking. Also, everywhere you use MyClass, add quotes: 'MyClass' so that Python is happy.

Typing Context managers

Context managers are a way of adding common setup and teardown logic to parts of your code, things like opening and closing database connections, establishing a websocket, and so on. On the surface it might seem simple but it’s a pretty extensive topic, and if you’ve never heard of it before, Anthony covers it here.

To define a context manager, you need to provide two magic methods in your class, namely __enter__ and __exit__. They’re then called automatically at the start and end if your with block.

You might have used a context manager before: with open(filename) as file: — this uses a context manager underneath. Speaking of which, let’s write our own implementation of open:

Typing async functions

The typing module has a duck type for all types that can be awaited: Awaitable.

Just like how a regular function is a Callable, an async function is a Callable that returns an Awaitable:

Generics

Generics (or generic types) is a language feature that lets you «pass types inside other types».

I personally think it is best explained with an example:

Let’s say you have a function that returns the first item in an array. To define this, we need this behaviour:

«Given a list of type List[X], we will be returning an item of type X.»

And that’s exactly what generic types are: defining your return type based on the input type.

Generic functions

We’ve seen make_object from the Type type section before, but we had to use Any to be able to support returning any kind of object that got created by calling cls(*args). But, we don’t actually have to do that, because we can use generics. Here’s how you’d do that:

T = TypeVar('T') is how you declare a generic type in Python. What the function definition now says, is «If i give you a class that makes T‘s, you’ll be returning an object T«.

And sure enough, the reveal_type on the bottom shows that mypy knows c is an object of MyClass.

The generic type name

Tis another convention, you can call it anything.

Another example: largest, which returns the largest item in a list:

This seems good, but mypy isn’t happy:

$ mypy --strict test.py

test.py:10: error: Unsupported left operand type for > ("T")

Found 1 error in 1 file (checked 1 source file)

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

This is because you need to ensure you can do a < b on the objects, to compare them with each other, which isn’t always the case:

>>> {} < {}

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: '<' not supported between instances of 'dict' and 'dict'

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

For this, we need a Duck Type that defines this «a less than b» behaviour.

And although currently Python doesn’t have one such builtin hankfully, there’s a «virtual module» that ships with mypy called _typeshed. It has a lot of extra duck types, along with other mypy-specific features.

Now, mypy will only allow passing lists of objects to this function that can be compared to each other.

If you’re wondering why checking for

<was enough while our code uses>, that’s how python does comparisons. I’m planning to write an article on this later.

Note that _typeshed is not an actual module in Python, so you’ll have to import it by checking if TYPE_CHECKING to ensure python doesn’t give a ModuleNotFoundError. And since SupportsLessThan won’t be defined when Python runs, we had to use it as a string when passed to TypeVar.

At this point you might be interested in how you could implement one of your own such

SupportsXtypes. For that, we have another section below: Protocols.

Generic classes

we implemented a simple Stack class in typing classes, but it only worked for integers. But we can very simply make it work for any type.

To do that, we need mypy to understand what T means inside the class. And for that, we need the class to extend Generic[T], and then provide the concrete type to Stack:

You can pass as many TypeVars to Generic[...] as you need, for eg. to make a generic dictionary, you might use class Dict(Generic[KT, VT]): ...

Generic types

Generic types (a.k.a. Type Aliases) allow you to put a commonly used type in a variable — and then use that variable as if it were that type.

And mypy lets us do that very easily: with literally just an assignment. The generics parts of the type are automatically inferred.

There is an upcoming syntax that makes it clearer that we’re defining a type alias:

Vector: TypeAlias = Tuple[int, int]. This is available starting Python 3.10

Just like how we were able to tell the TypeVar T before to only support types that SupportLessThan, we can also do that

AnyStr is a builtin restricted TypeVar, used to define a unifying type for functions that accept str and bytes:

This is different from Union[str, bytes], because AnyStr represents Any one of those two types at a time, and thus doesn’t concat doesn’t accept the first arg as str and the second as bytes.

Advanced/Recursive type checking with Protocol

We implemented FakeFuncs in the duck types section above, and we used isinstance(FakeFuncs, Callable) to verify that the object indeed, was recognized as a callable.

But what if we need to duck-type methods other than __call__?

If we want to do that with an entire class: That becomes harder. Say we want a «duck-typed class», that «has a get method that returns an int», and so on. We don’t actually have access to the actual class for some reason, like maybe we’re writing helper functions for an API library.

To do that, we need to define a Protocol:

Using this, we were able to type check out code, without ever needing a completed Api implementaton.

This is extremely powerful. We’re essentially defining the structure of object we need, instead of what class it is from, or it inherits from. This gives us the flexibility of duck typing, but on the scale of an entire class.

Remember SupportsLessThan? if you check its implementation in _typeshed, this is it:

Yeah, that’s the entire implementaton.

What this also allows us to do is define Recursive type definitions. The simplest example would be a Tree:

Note that for this simple example, using Protocol wasn’t necessary, as mypy is able to understand simple recursive structures. But for anything more complex than this, like an N-ary tree, you’ll need to use Protocol.

Structural subtyping and all of its features are defined extremely well in PEP 544.

Further learning

If you’re interested in reading even more about types, mypy has excellent documentation, and you should definitely read it for further learning, especially the section on Generics.

I referenced a lot of Anthony Sottile’s videos in this for topics out of reach of this article. He has a YouTube channel where he posts short, and very informative videos about Python.

You can find the source code the typing module here, of all the typing duck types inside the _collections_abc module, and of the extra ones in _typeshed in the typeshed repo.

A topic that I skipped over while talking about TypeVar and generics, is Variance. It’s a topic in type theory that defines how subtypes and generics relate to each other. If you want to learn about it in depth, there’s documentation in mypy docs of course, and there’s two more blogs I found which help grasp the concept, here and here.

A bunch of this material was cross-checked using Python’s official documentation, and honestly their docs are always great. Also, the «Quick search» feature works surprisingly well.

There’s also quite a few typing PEPs you can read, starting with the kingpin: PEP 484, and the accompanying PEP 526. Other PEPs I’ve mentioned in the article above are PEP 585, PEP 563, PEP 420 and PEP 544.

And that’s it!

I’ve worked pretty hard on this article, distilling down everything I’ve learned about mypy in the past year, into a single source of knowledge. If you have any doubts, thoughts, or suggestions, be sure to comment below and I’ll get back to you.

Also, if you read the whole article till here, Thank you! And congratulations, you now know almost everything you’ll need to be able to write fully typed Python code in the future. I hope you liked it ✨

#python #mypy

Вопрос:

Я пытаюсь настроить MYPYPATH для поиска библиотеки, расположенной в другом каталоге. Я импортирую функцию, подобную этой:

from my_module import my_function

Структура файла:

function

|__lib1

| |__lib2

| |__my_module.py

|__function1

|__src

|__index.py <-- this is the file where my_module is imported

Структура файла должна быть такой, потому что это лямбды AWS ( lib1 здесь слой Лямбда).

Я использую следующую конфигурацию tox:

skipsdist = True

envlist = mypy

[testenv]

deps = -r requirements.txt

[testenv:mypy]

commands = mypy --namespace-packages -p function -p test

Я попытался установить:

setenv = MYPYPATH = './function/lib1/lib2'

setenv = MYPYPATH = './function/lib1/lib2/my_module.py'

так же как

mypy_path = 'function/lib1/lib2'

mypy_path = 'function/lib1/lib2/my_module.py'

Я также попробовал полный путь вместо относительного пути.

Тем не менее, я все еще получаю ту же ошибку: error: Cannot find implementation or library stub for module named my_module .

Это не проблема токсичности, так как запуск mypy --namespace-packages -p function -p test в одиночку приводит к той же ошибке.

Есть ли способ заставить это работать?

Комментарии:

1. Всегда полезно добавить команду, которая привела к ошибке. Для проблем, связанных с токсикозом, пожалуйста, укажите выходные данные для

tox -rvv. У вас очень особенная настройка проекта. Было бы намного проще помочь вам, когда вы создаете фиктивное репо с указанными выше файлами/папками, поэтому любой, кто пытается вам помочь, может попробовать это локально.2. Я отредактировал первоначальный пост — проблема заключается в самой конфигурации mypy, а не в токсичности.

3. может быть, вам следует добавить

/full/path/to/lib2вместо относительного пути4. Я попробовал пройти полный путь, но это не помогло

I use .pre-commit-config.yaml file with pre-commit-hooks and mypy in it.

When I run

poetry run pre-commit run -a -v

everything works perfectly

When I do a commit with

git commit -m "test"

it gives me an error saying

tests/test_typeguard_checker.py:2:1: error: Cannot find implementation or library stub for module named "pytest" [import]

tests/test_typeguard_checker.py:2:1: note: See https://mypy.readthedocs.io/en/stable/running_mypy.html#missing-imports

My project folder structure looks as follows

src

----ch_news

--------__init__.py

--------main.py

--------typeguard_checker.py

--------py.typed

tests

----__init__.py

----test_main.py

----test_typeguard_checker.py

----test.....

tox.ini

pyproject.toml

mypy.ini

.flake8

.gitignore

.pre-commit-config.yaml

.pre-commit-config.yaml file

default_language_version:

python: python3.10

default_stages: [commit, push]

repos:

#... Other hooks

- repo: https://github.com/pre-commit/mirrors-mypy

rev: v0.961

hooks:

- args: ["--verbose"]

description: Type checking for Python

id: mypy

Here s what mypy,ini file looks like

# https://mypy.readthedocs.io/en/stable/config_file.html#example-pyproject-toml

[mypy]

show_column_numbers = true

show_error_codes = true

show_error_context = true

strict = true

warn_unreachable = true

pyproject.toml file

[tool.poetry]

name = "ch_news"

version = "0.1.0"

description = "Load news items from various RSS feeds and store them to postgres database"

authors = ["vr <ch@gmail.com>"]

[tool.poetry.dependencies]

python = "^3.10"

[tool.poetry.dev-dependencies]

pytest = "^7.1.2"

coverage = {version = "^6.4.1", extras = ["toml"]}

pytest-cov = "^3.0.0"

tox = "^3.25.1"

pre-commit = "^2.19.0"

typeguard = "^2.13.3"

[tool.coverage.paths]

source = ["src", "*/site-packages"]

[tool.coverage.run]

branch = true

source = ["ch_news"]

[tool.coverage.report]

fail_under = 100

[tool.isort]

atomic = true

balanced_wrapping = true

force_single_line = true

include_trailing_comma = true

line_length = 88

multi_line_output = 3

profile = "black"

[tool.poetry.scripts]

ch-news = "ch_news.main:main"

[build-system]

requires = ["poetry-core>=1.0.0"]

build-backend = "poetry.core.masonry.api"

Can someone please tell me how to fix this error

In a Python file, my first line is:

from flask import Flask

Which triggers an error in the gutter that shows the following message when I drag the cursor over that line:

Cannot find implementation or library stub for module named "flask"

I have installed Flask with Pipenv in a virtual environment. Then I have activated the virtual environment. Running Flask from there works so I assume I have installed it correctly.

I also run Vim from that activated virtual environment:

Running

:py3 import sys, site; print('Version:', sys.version); print('Executable:', sys.executable); print('Site Packages:', site.getsitepackages()) returns:

Version: 3.9.6 (default, Jun 30 2021, 10:22:16)

[GCC 11.1.0]

Executable: /home/bastien/.local/share/virtualenvs/flask-hxySx92r/bin/python3

Site Packages: ['/home/bastien/.local/share/virtualenvs/flask-hxySx92r/lib/python3.9/site-packages']

So I understand Vim is correctly running from the virtual environment.

Installing Flask globally and running Vim again does not trigger that error. So I assume the package from the virtual environment cannot be found.

I use ALE, but after investigating, I’m not sure anymore what is responsible for printing those messages.

Also, youcompleteme stops working when running Vim from the virtual environment. I have set the full python path though.

Any help is appreciated.

calimeroteknik opened this issue 8 months ago · comments

The following pull request (merged) #7644

Caused the following:

from typing import TYPE_CHECKING if TYPE_CHECKING: import wsgiref.types

to go from no error at all to:

repro.py:3: error: Cannot find implementation or library stub for module named "wsgiref.types"

repro.py:3: note: See https://mypy.readthedocs.io/en/stable/running_mypy.html#missing-imports

Found 1 error in 1 file (checked 1 source file)

Using Python 3.10.4, 3.10.5 and any mypy version later than what follows:

This could be bisected between 0.950 and 0.960 through this commit python/mypy@40bbfb5

And further refined to end up at the aforementioned pull request.

I believe the support for 3.10 was insufficiently tested.

wsgiref.types used to be a module that was only available during type checking, but not at runtime. It had been deprecated for a while. Please update your imports to _typeshed.wsgi, our typeshed-internal module. (Python 3.11+ has a wsgiref.types module at runtime, which we only support on these Python versions.)

If I understand correctly:

The new version for this import, that is here to stay in the users’ code until it drops support for every version up to 3.10 (that is, every version released, to this day), goes as follows:

import sys if sys.version_info >= (3, 11): from wsgiref.types import WSGIEnvironment, StartResponse, InputStream else: from typing import TYPE_CHECKING if TYPE_CHECKING: from _typeshed.wsgi import WSGIEnvironment, StartResponse, InputStream

In light of the consequences, could the regression/instant deprecation please be reverted to bridge the gap before 3.11 is released (or even widespread, that is, leaving a small window of deprecation)?

Or could one argue I was using an utterly unsupported feature to begin with?

As bleeding edge as it gets, 3.11 isn’t even released yet, I believe that the timing on this change was exceedingly forceful!

I would argue that a deprecation window of negative size is really too small.

To note, the breaking change here was the addition of this line to VERSIONS, which means that mypy now (correctly) recognises that wsgiref.types only exists on 3.11+:

I suppose we could delete that line, and have mypy erroneously believe for a little longer that wsgiref.types exists on all Python versions. But there’s no mechanism (yet) in a stub to signal to a type checker «this feature is deprecated, please raise a warning if a user imports it». We definitely want to make this change eventually, and it’s always going to be disruptive when we do make it, because of the inability to raise a DeprecationWarning from a stub file.