- Главная

- Статьи

- о типичных заданиях

- Error Correction

Что такое error correction?

Error Correction — одна из разновидностей заданий, проверяющих лексические и грамматические знания ученика. Суть задания: прочесть текст/предложение и найти в нем ошибку, если она есть. Существует довольно много вариаций Error Correction. В этой статье мы рассмотрим некоторые из них.

Поиск лишнего слова

Распространенный тип error correction — поиск лишнего слова. Такие задания входили раньше в состав FCE (в современном FCE их уже нет) и касались, в основном, грамматических ошибок. Например, в качестве лишних слов выступали артикли, предлоги, местоимения, вспомогательные глаголы и прочие «мелкие» слова.

В более сложных вариациях вставляются лишние слова, наполненные лексическим смыслом и являющиеся частями каких-нибудь хорошо известных выражений. Такие задания можно найти, например, в экзамене BEC.

Чтобы распознать лексические ошибки, нужно фокусироваться не только на отдельных комбинациях слов, но и на общем смысле. Часто делают так: берется хорошо известное слово, которое однозначно ассоциируется с каким-либо предлогом или глаголом, и вставляется в контекст, где присутствует тот самый предлог или глагол. Таким образом, создается иллюзия, что лексически все верно. Аналогично поступают и с грамматическими конструкциями. Например:

- And that word, through the refining filter of Paris, is all I need to conjure up my mother: as she licked from her lips the residue of some oozing cream cake; as if she held up to herself, like some flimsy, snatched -up dancing partner, a newly bought frock: ‘Isn’t it just divine!’

Словосочетание as if само по себе не вызывает подозрений, это распространенная грамматическая конструкция. Только при оценке общего смысла можно понять, что if в данном предложении является лишним. Именно такие приемы наиболее распространены на олимпиадах.

Найдите лишнее слово:

There are thousands of verbs in English and the most of them are regular.

Ответ

Ответом будет слово the, потому что этот артикль не используется вместе с ‘most of them’.

First task of all, you need to be sure that an event is really the best way to get your message across to customers.

Ответ

Ответом будет слово task, потому что именно оно не вписывается в предложение. В английском языке нет сочетания ‘first task of all’, есть сочетание ‘first of all’. Соответственно, слово ‘task’ является той самой ошибкой, которую нужно найти и выписать.

Customer service is included every employee’s responsibility, and it should be a proactive rather than a reactive strategy.

Ответ

Ответ: included. Слово ‘included’ здесь лишнее, поскольку существует выражение ‘to be somebody’s responsibility’. Кроме того, после included должен быть предлог, а в тексте его нет. При этом существует выражение ‘to be included’, что позволяет слову «маскироваться» и затрудняет поиск ошибки.

Другие виды ошибок

Нахождение лишнего слова — самый распространенный вид error correction, но не единственный. Помимо него есть, например, варианты, когда дается предложение с ошибкой, и нужно просто понять, есть ошибка или нет. Ошибка не обязательно будет в виде лишнего слова. Она может быть стилистической, лексической, пунктуационной, орфографической. Задания такого рода можно встретить, например, на экзамене SAT.

- Because the coach was (A) so preoccupied on (B) developing and practicing trick plays, she did not spend (C) enough time drilling (D) the fundamental skills. (E) No error

В приведенном примере ошибкой является предлог on в пункте (B) — правильным предлогом будет with. В этом задании не требуется исправлять найденную ошибку, но бывают и такие, где требуется. Это, как правило, олимпиадные задания.

Где ошибка?

Although statistical methods can rarely prove (A) causality, they can frequently refute (B) theories by demonstrating that no correlation exists (C) between particular effects (D) and their presumed causes. (E) No error

Ответ

В этом предложении ошибок нет. Правильный ответ — (E).

The project on nuclear energy that Jenna presented (A) to the science fair committee was (B) considered superior to the other students (C), and so (D) she was awarded the blue ribbon. (E) No error

Ответ

Правильный ответ — (C), поскольку слово students должно стоять в притяжательном падеже: students’.

Найти и исправить

Задания на исправление ошибок (не просто на нахождение, а именно на исправление) особенно многочисленны в олимпиадном мире и варьируются от достаточно простых до труднопроходимых.

В относительно простых заданиях текст разбивается на фрагменты (строки, предложения или абзацы), и в каждом фрагменте может находиться только одна ошибка. В более сложных вариантах никакой разбивки на фрагменты нет, и ошибкой может быть что угодно: как присутствие каких-либо слов, так и их отсутствие.

Иногда вам может быть предложено не только найти ошибки в слитном тексте, но также классифицировать их — определить, к какому типу они относятся (например, Tenses, Passive Voice, Spelling).

Если вам попадается задание, которое вы ни разу в жизни не встречали, не торопитесь нервничать: принципы поиска ошибок всегда одни и те же, независимо от особенностей формата. Нужно внимательно прочитать текст целиком, а затем идти по нему шаг за шагом и отслеживать все подозрительные моменты.

Найдите и исправьте 10 ошибок:

The drying East wind, which always had brought hard luck to Eastern Oregon at whichever season it blow, had combed down the plateau grasslands through so much of the winter that it was hard to see any sign of grass ever grown on them. Even though March has come, it still blew, drying the ground deep, shrinking the watercourses, beating back the clouds that might delivered rain, and grinding coarse dust against the fifty odd head of work horses that John brought down from his homestead to turn back into their home pasture while there was still something left of them. The two man, one past sixty and another around sixteen, shouldered the horses through the gate of the home pasture and drew up outside the yard that they had picked wrong time to come.

Ответ

The drying East wind, which always had brought hard luck to Eastern Oregon at whichever whatever season it blow blew had combed down the plateau grasslands through so much of the winter that it was hard to see any sign of grass ever having grown on them. Even though March has had come, it still blew, drying the ground deep, shrinking the watercourses, beating back the clouds that might have delivered rain, and grinding coarse dust against the fifty odd head of work horses that John had brought down from his homestead to turn back into their home pasture while there was still something left of them. The two man men, one past sixty and another the other around sixteen, shouldered the horses through the gate of the home pasture and drew up outside the yard that they had picked the wrong time to come.

Где может встретиться Error Correction?

Error Correction часто встречается на олимпиадах по английскому языку. Оно встречалось и на Всероссийской олимпиаде школьников, и в СПбГУ, и в Плехановской, и в Челябинской, и в «Высшей пробе» — проще найти олимпиады, где этот формат не встречался.

Помимо олимпиад, error correction можно найти в экзаменах SAT и BEC, а также в старых тестах FCE (в новых FCE этот формат убрали).

Как тренироваться?

Чтобы успешно справляться с error correction, нужно владеть и грамматикой, и лексикой. Кроме того, необходимо уметь внимательно читать текст и бороться с одолевающими сомнениями.

Обычно в начале тренировок допускается много ошибок (точнее, ошибки в тексте выпадают из поля зрения). Однако сделав десяток-другой упражнений, человек начинает улавливать, где обычно следует искать подвох, и может найти уже большее количество ошибок. Так что в случае с error correction нужно не только развивать знание языка, но и тренировать скилл нахождения ошибок с помощью практики.

© Екатерина Яковлева, 2016–2022

Students shouldn’t be afraid of using the wrong tense or omitting an article as making mistakes is the proof of learning, but the question is how teachers handle these mistakes. Too much error-correction can demotivate students, on the other hand, to let the conversation flow and not to correct any mistakes can also cause some problems in the future. The difficulty, of course, is in finding the middle ground. What should we correct, when should we correct it, and how should it be corrected?

Step 1 — Identify the reason for making mistakes (what to correct):

1. L1 interference — happens when the learner’s mother tongue affects performance in the target language. For example, learners make grammatical mistakes because they apply the same grammatical patterns as in their L1.

Read more in “Learner English”, a practical reference guide which compares the relevant features of a student’s own language with English, helping teachers to predict and understand the problems their students have. It has chapters focusing on major problems of pronunciation, grammar, vocabulary and other errors.

2. A developmental error — an error that occurs as a natural part of the learning process when a learner tries to say something that is above their level of language.

3. Overgeneralization of a rule — the process of extending the application of a rule to items that are excluded from it in the language norm.

4. A fossilized error — the process in which incorrect language becomes a habit and cannot easily be corrected.

5. A slip — a mistake made by a learner because they are not attentive or tired.

6. The nature of English — some set collocations, idiomatic expressions may cause errors.

7. Bad model — students learnt poor example and incorrect language from any available resources.

Some tips:

- We shouldn’t correct slips as they happen not because students don’t know the material but are caused by tiredness, inattention or just having too much to think about at the time.

- We should be careful with correcting developmental errors. Making such errors is a natural part of learning a language. You may just ignore them, as the student hasn’t studied the essential material yet or you can just articulate the correct sentence and that you are going to study that grammar or vocabulary later.

- We must correct all other types of mistakes, but don’t try to correct all the mistakes students make, choose ones which are relevant to the lesson/topic/activity.

Step 2 — Choose the best time to correct (when)

There are two kinds of error correction:

- Hot correction — as soon as we notice a student making an error.

- Cold correction (delayed error correction) — in order not to interrupt the learner during a speaking activity- as we are focusing more on oral fluency, we need to monitor and record the language of the learner to focus on the errors when the activity is complete. Conduct an error correction after the activity of at the end of the lesson.

Some tips:

- Use hot error correction during the presentation of the target language or controlled practice, as we are more focused on accuracy here. You should encourage SELF CORRECTION n first and then peer correction if needed, therefore ask CCQs (concept checking questions) that focus on meaning and form.

- Use cold (delayed) error correction while students are doing freer activity. Monitor the students and take notes of mistakes.

Step 3 — Choose an error correction technique (how)

There are many ways to correct errors:

Non verbal:

1. Finger correction — use fingers to show the mistake in the sentence.

2. Gestures — every teacher has a set of gestures to show students they’ve made a mistake. Teachers might gesture backwards with their hands to show students they haven’t used the verb in the past. Students often use the wrong pronouns, for example “She walked your dog.” You can point to yourself with a look of shock or surprise.

3. Facial expressions — when a student makes a mistake you can use an exaggerated facial expression to signal the mistake.

4. Cards (visual reminders) — some students often omit “-s”, “be”, etc. So you can just prepare a card with a big “S” or “AM/IS/ARE” and raise it every time students do this mistake, students instantly know they should go back and say it again. Later, you can just stick an empty card on the desk and point at it when necessary.

5. Visual analysis — write the sentence on the board and highlight indicators, question marks, everything that might help the student to correct the mistake, e.g.:

Verbal:

6. Repeat up to the error — repeat the whole sentence up to the error and make a pause waiting for the student to say the correct word/phrase. If the student has a difficulty correcting the mistake, give options.

S: My mum is really interesting in politics.

T: Your mum is really …

S: Interesting.

T: InterestING or interestED?

7. Demonstrate more examples — elicit or demonstrate more sentences with the same vocabulary or constructions.

S: I love SHocolate.

T: Read the words “chair, chicken”, now read this word “CHocolate”

8. Echoing — echo the mistake with emphasis on the mistake.

S: He like listening to rock music.

T: He LIKE?

S: He likeS listening to rock music.

9. Ask for clarification — ask your student to repeat the sentence.

S: I went to the magazine.

T: Sorry? Where did you go?

10. Recast — reformulate the utterance into a correct version (emphasising the place of the mistake) and encourage to continue the conversation.

S: Yesterday I went in the shop.

T: Oh really, you went TO shop. Which shop?

!!Try to elicit the corrections as much as possible. Get students to fix their own mistakes.

What error correction techniques do you prefer?

In English language teaching, error correction is something which is expected of teachers, so what error correction techniques are there to make the most out of the errors we correct? And how can we make sure that correction is helping our students?

As teachers, we are told that error correction is necessary. However, the value of error correction has long been discussed. Is what we are doing enough or should we stop altogether? In our post-method, eclectic, throw-everything-at-them-and-something-is-bound-to-stick era we need to be aware of the options available so we can decide what is best for us and our students.

Maybe you’re right, maybe you’re wrong

Expert opinions on error correction have evolved over the years. Take a look at these quotes and consider which one most closely represents your personal opinion.

- Like sin, error is to be avoided and its influence overcome, but its presence is to be expected – Brooks (1960)

- Error correction is a serious mistake because it puts students on the defensive and causes them to avoid complex constructions – Krashen (1982)

- You should tell students they are making mistakes, insist on accuracy and ask for repetition – Harmer (1983)

- There is a place for correction, but we should not overestimate it – Ur (1996)

- Feedback on learners’ performance in an instructional environment presents an opportunity for learning to take place – Larsen-Freeman (2003)

- Correction works best when done in context at the time the learner makes the error – Mackay (2007)

From error being seen as sin during the height of audiolingualism to viewing error as opportunity to learn, errors and correction have been a hotly debated topic in the ELT world.

This is why there is such a challenge for teachers. We must withdraw ourselves from our opinions and expectations in order to evaluate students on an individual level when it comes to errors. We then have to balance this with an institutional and cultural expectation to be corrected in the classroom.

Importantly, we have to ensure the learner has understood the correction, internalised it and improved their personal language system or interlanguage.

Interlanguage is a concept that refers to each learner’s personal knowledge of a 2nd language. It is the language which they know as they have learned it with potential for influence from their 1st language and overgeneralization of certain rules learned about their 2nd language. Hence the potential for error.

A learner’s interlanguage is unique to them. It is all they are able to use to communicate and it is what, as teachers, we are aiming to improve in each class, even in each interaction we have with students.

What is an error?

In ELT there have traditionally been two categories, errors and slips.

Errors happen when a learner doesn’t have sufficient knowledge of the language. This could occur when they have never been exposed the language and make an error because they have no prior knowledge to refer to. These are known as attempts. Or errors could come from the language having been acquired incorrectly and as far as they are concerned they are correct. These are fossilized errors.

Slips are the opposite end of the error spectrum. Slips happen when a learner knows the language but due to the speed of conversation or other factors, they say or write something incorrect. These are often self-corrected or ignored. They even happen to native speakers when we mispronounce a word or mix up words in an idiom that we’ve used a million times. One interesting thing to note is that even at the highest bands of C2 level, Cambridge writing scales say that inaccuracies that occur as slips are perfectly acceptable. They are not something to be punished.

Personally, I think there a bit of a gap here. We need something to fill in the middle ground. That is what I refer to as mistakes. Mistakes happen when a learner forgets the language that they have already acquired. It’s not that they don’t have the language, it’s that they haven’t accessed it correctly. Typical mistakes would come from L1 influence and often involve the use of false cognates or word order. The over-application of L1 rules in L2 frequently causes mistakes. This could happen to native speakers too, especially children. The typical example is when they conjugate an irregular past verb incorrectly (e.g. teached) because they have learnt a new rule and they start applying it too much.

When should we correct?

Correcting errors

Errors are the most difficult to correct, because not only are you providing a correction, you are also providing the knowledge necessary to fill the student’s gap in understanding. Errors should always be corrected, however, you need to be very careful about when and how to correct them.

We’ve all been in the situation where we try to correct an error quickly, only to get pulled down a rabbit hole where before we know it the board is covered in example sentences, phonemes and an explanation of the present perfect continuous. So correction of errors has to be structured and formulated in a way that allows students to recognise how to form the correct language, but without breaking the flow of the class.

Correcting mistakes

Mistakes should be dealt with completely differently. Mistakes are not due to lack of knowledge. Therefore, if you delay correction, the student will look at the error and instantly know what the problem is. They will think something along the lines of “Oh yeah, I knew that”. So what have we achieved as a teacher at that point? We haven’t helped to fill any gaps in knowledge.

That’s why mistakes should be corrected the moment they are made, even during a fluency activity. If you correctly identified the problem as a mistake, not an error, the correction should be quick and easy.

Correcting slips

Slips don’t need to be corrected at all. Slips are like your mother always confusing you and your sibling’s names. You know that she knows who you are, she just can’t ever seem to get it right. Correcting your mother may be satisfying for you as the corrector, but it’s not going to help her understand better who you are. And it might just make her flustered.

Correction in exam preparation classes

This is a blog about exam preparation after all. In many ways, everything that applies to error correction in general also applies to exam preparation classes. However, if anything, correction is even more important and even more expected. In general, we want our students to achieve successful communication and be intelligible. Unfortunately, for exams, this is often not enough.

The burden of correction falls even harder on the exam teacher. Insist on accuracy and demand the most of your students. They will thank you for it in the end.

Error correction techniques

There are many different types of error correction. Some of these we are taught how to do, while some of them come naturally. Some of them we would use in normal everyday situations.

Have you ever been in a shop and someone walks up to you to ask you where something is because they think you work there? How would you correct that person? You would probably say “I don’t work here” and for some reason apologise for their mistake. What you wouldn’t do is launch into a long explanation of why you choose to be an English teacher, not a shop assistant. And you wouldn’t start miming confusion and pointing across the shop to the employees who do work there.

That’s because certain correction techniques work better in some situations than others. Some work better for one type of error than for another. As teachers in the post-method era, we need to have an extensive bank of error correction techniques that we can dip into whenever we feel it’s necessary.

That’s our responsibility as teachers, to have the knowledge to be able to employ different techniques in different contexts.

Classic error correction techniques

| Metalinguistic explanation S – She has a long black hair. T – Hair is an uncountable noun so it doesn’t take the indefinite article. |

| Repetition S – In the morning, I get up at seven o’clock, clean my tooth, have breakfast and go to work. T – You clean your tooth? |

| Direct explicit correction S – It is dangerous to smoke while you become pregnant. T – While you become pregnant is very different. You mean while you are pregnant. |

| Peer correction During an in class written activity where students complete a letter in pairs: S1 – Feel free to contact me if you are a problem. S2 – I think it’s have a problem. |

| Delayed correction S – The cheerleaders threw up high into the air. T writes the sentence down in a notebook and puts it up on the board after the activity. The whole group corrects the sentence. |

| Recast S – When we won, I was so exciting. T – You were excited. |

| Paralinguistic explanation S – Last night, while I was eating dinner, I started /dʒəʊkɪŋ/ so my friend hit me. T – Makes a facial expression of confusion. Mimes laughing and choking. |

| Elicitation S – Waiter, could you bring me some tissues, please? T – Could you bring me some ……, please? |

| Clarification request S – You can’t sleep in my room because it is too crowded, but you can sleep with my sister. T – Excuse me? |

| Tell them they are wrong Teacher hands out a worksheet S – I hope this the last /ʃɪt/ for today. T – That’s not how you pronounce that word. |

Any and all of these correction techniques are acceptable and recommendable in the classroom. However, it is your role as a teacher to choose the best form of correction for the moment you correct.

Studies have shown, for example, that recasts, despite being the most common form of correction, are often overlooked. Students don’t notice they are being corrected. This happened more often with groups of Italian students than it did with groups of Japanese students. That’s because Japanese students have a significantly different mentality towards learning languages and were more attuned to the recast being an opportunity to learn.

Similarly, some students may like having their errors highlighted and displayed on the board after an activity while for others this could cause substantial embarrassment, thus lowering their motivation and causing them to avoid complex language in future interactions in order to avoid error in the future.

This is why we have to have a bag of tricks when it comes to error correction. There is no one-size-fits-all solution.

Adapted error correction techniques

While all of the above techniques are useful and acceptable depending on the context and circumstances, there is definitely a way to make error correction more interesting and ensure you are improving your students’ interlanguage.

Here are a couple of ideas that I have found to be effective:

Post-it correction

Method:

- Write errors on post-its or small

pieces of paper. - Slip those papers to the pair or

group when they are done with the activity. - They work together to write

corrections on the same paper.

Benefits:

- Students are correcting their own

errors rather than the smartest student in the group correcting everyone’s

errors. - Great for fast finishers.

- Post-its are fun.

Error collection

Method:

- Keep a record of errors on Google

Slides or Quizlet. - Add to this record whenever there is

a recurrent error. - Use as a warmer or cooler to recycle

correction. - Can be adapted into games like

back-to-the-board.

Benefits:

- Helps with fossilised errors.

- Avoids the judgemental effect of

constantly correcting the same mistake. - Can be shared with students.

Stem correction

Method:

- Write only the stem of the incorrect

sentence on the board. - Students think of different ways to

finish the sentence correctly. - The mistake is never explicitly

stated, but the student who made it will probably realise that it was something

they said.

Benefits:

- Helps students upgrade language.

- Forces students to notice the

language. - Takes the pressure off the teacher

and the student.

Anticipation

Method:

- Think about the errors students

always make, especially before a certain grammar point that you have taught

before. - Before the activity write them up on

the board with a big cross through them. Tell the students to be careful about

these mistakes.

Benefits:

- Reminds students to think before

they misspeak. - Can be used as a visual aid if

anyone does make the mistake. - Makes you look like a clairvoyant.

Conclusions

Whether you are teaching 1-to-1, exam preparation or conversation classes, ensure that error correction is present in all your lessons. The expectation for correction is clear and its benefit is established.

One of the best things you can do as a teacher is aid language acquisition through targeted and effective corrective feedback that embraces the concepts of noticing and demanding high while ensuring the advancement of learners’ individual language systems.

Outline:

1- Error & Mistake

2- Sources of Errors

3- Views on Errors/Mistakes

4- Error Correction Types

5- Practical Strategies to Error/mistake correction

1- Error & Mistake :

A mistake can either be a slip of tongue or a temporary deficiency in producing language. Mistakes can occur when learners are tired or when they unwillingly fail to apply grammar while speaking. Generally, mistakes are self-corrected, since learners promptly notice them. If they don’t, a simple hint from the teacher or other learners would suffice to make learners aware of their mistakes and accordingly correct them. On the other hand, an error is a repeated mistake that is suggestive of the learner’s failure to grasp a structure or apply it properly. For instance, if a student says repeatedly,” she musts”, instead of must, it implies that he has not fully grasped the rules governing modals or is not acquainted with them all together.

In concise terms, a mistake is a lapse made at the surface, while an error is a lapse that indicates a deficiency in the deep surface (competence; linguistic knowledge, as Chomsky refers to it)

Now many would wonder; why do learners make errors? What are the sources of errors?

2- Sources of Errors :

Significant body research has been conducted to trace the sources of errors in L2 learning. This substantial body of literature points to three major sources; interlingual interference (interference of the mother tongue), intralingual (overgeneralizations), and context of learning.

Interlingual interference or the interference of L1 in the learning of L2 is a major source of errors. Students, especially beginners, draw from the system of their L1 in order to use and understand L2. This reliance may lead students to utter wrong statements. For instance, many Moroccan students say, ”I have 17 years old”, as an alternative to “I’m 17 years old”. This shows evidently that the source of error is the interference of L1 (Moroccan Standard Arabic) in L2 (English).

Intralingual interference or overgeneralization is one of the most prominent sources of errors. Students gradually learn the grammatical rules of the language. As they do, they form hypotheses about the language on the basis of their prior linguistic language. It often results in them falling in the trap of overgeneralization. A student may say “Information”, believing that forming plural is done by adding s to nouns.

The context of learning refers to the materials, atmosphere where the learning takes place, and it also includes the teacher. The atter can also be a source of errors. Teachers’ failure to explain a lesson adequately or clarify it but wrongly, may lead

students to make errors.

3- Views on Errors/Mistakes:

We have now looked at the sources of errors. Now let us see how some teaching approaches/methods consider mistakes or errors.

| Audiolingualism | Communicative Language Learning |

| Errors or mistakes are bad habits that should be avoided by students. Students, who make mistakes/errors, must be penalized. |

Errors are tolerated Mistakes/errors are part and partial of the learning process. They should be used as the basis to constructing knowledge |

4- Error Correction Types

- Self-correction: the teacher may help the student recognize his mistake/error and may also help him correct it.

- Peer-correction: A student may be aided by his peer in identifying and correcting his mistake/error.

- Class-correction: The entire class may pay attention to the utterances of students, identify the mistakes in them, and correct them accordingly.

- Teacher-Correction: When spotting a mistake made by a student, a teacher may intervene in order to correct it.

It is preferable that the teacher makes students aware of their mistakes. If they fail to know their mistakes, a teacher can resort to the entire class group for correction. If other students fail to see the mistake as well, the teacher can then correct him/herself.

5- Practical Strategies to Error/mistake correction :

Repetition:

This is typically used to correct pronunciation mistakes. A teacher may verbally repeat the utterance of a student in order to correct the mistake in it. For example, a beginning-level student may say “I know him”, pronouncing the word “know” as it’s written; a teacher can repeat the word again and correct the students’ pronunciation.

Reformulation :

a teacher may reformulate a mistaken sentence in order to correct it. Example; “I like to playing soccer”; student’s statement. The teacher’s statement would be;”oh, you like to play soccer”.

Body language and facial expressions :

believe or not, body language and facial expressions can help students realize their mistakes. A look of confusion coupled with hand gestures can make students aware of their mistakes.

Students’ repetition :

When a student makes a mistake, a teacher may tell him/her to repeat the utterance and stop him at the mistake he made.

Note-taking :

another useful technique for correcting language blunders is by noting them down. A teacher may take a notebook and write down the recurring mistakes/errors of his/her students so that he/she can, later on, devise a remedial activity to correct them.

Self or Peer-correction:

Do you think it’s pronounced like this, do you agree with this answer?

Error

Correction

Mistakes and Errors

Errors happen when learners try to say something that is

beyond their current level of language processing. Usually, learners cannot

correct errors

themselves because they don’t understand what is wrong. Errors play a necessary

and important

part in language learning. Slips are the result of tiredness, worry or

other

temporary emotions or circumstances. These kinds of mistakes can be corrected

by learners once

they realise they have made them.

Two main reasons why learners make errors.

There are two

main reasons why second language learners make errors. The first reason

is

influence from the learner’s first language (LI) on the

second language. This is called

interference or transfer. Learners may use sound patterns, lexis or

grammatical structures from

their own language in English.

The

second reason why learners make errors is

because they are unconsciously working out

and organizing language, but this process is not yet complete. This kind of

error is called a

developmental error. Learners of whatever mother tongue make these kinds of

errors, which

are often similar to those made by a young first language speaker as part of

their normal

language development. For example, very young first language speakers of

English often make

mistakes with verb forms, saying things such as ‘I goed’ instead of ‘I went’.

Errors such as this

one, in which learners wrongly apply a rule for one item of the language to

another item, are

known as overgeneralisation. Once children develop, these errors

disappear, and as a second

language learner’s language ability increases, these kinds of errors also

disappear.

Errors

are part of learners’ interlanguage, i.e.

the learners’ own version of the second

language which they speak as they learn. It develops and progresses as they learn

more.

Experts think that interlanguage is an essential and unavoidable stage in

language learning, in

other words, interlanguage and errors are necessary to language learning.

Errors

are a natural part of learning. They

usually show that learners are learning and that

their internal mental processes are working on and experimenting with language.

Experts believe that learners can be helped to develop their interlanguage. There

are three main

ways of doing this. Firstly, learners need exposure to lots of

interesting language at the right

level; secondly they need to use language with other people; and thirdly

they need to focus

their attention on the forms of language.

Oral mistakes

Look

at the following examples of learners’ oral mistakes. There are mistakes of

accuracy

(grammar,

pronunciation, vocabulary) and appropriacy. Can you identify them?

1

She like this picture. (Talking about

present habit)

2

Shut up! (Said to a classmate)

3

I wear my suit in the sea.

4

Do you know where is the post office?

5

The dog /bi:t/ me. (Talking about a dog

attacking someone)

Accuracy

Examples

1, 3,4, 5 and 6 all contain examples of inaccurate language.

·

In Example 1 there is a grammar

mistake. The learner has missed the third person s from the

verb. The learner should have said ‘She likes this picture’.

·

Example 2 contains an example of inappropriate

language. Although Example 2 is accurate, there

is a problem with appropriacy. It is rude to say ‘Shut up!’ in the classroom.

The learner should have said ‘Can you be quiet, please?’, or something similar.

·

In Example 3 there is a vocabulary

mistake. The learner has used suit

instead of swimsuit. The learner should

have said “I wear my swimsuit in the sea”.

·

In Example 4 there is a grammar

mistake. The learner has put the subject and verb in the

wrong order in the indirect question. The learner should have said “Do you know

where the

post office is?”

·

In Example 5 there is a pronunciation

mistake. The learner has used the long /i:/ sound when she should have used the

short /I/ sound. The learner should have said ‘The dog /bit/ me’.

Oral correction

Here

are some ways that we can correct oral mistakes:

·

Finger correction. This shows learners where they have made a mistake. We

show one hand to the class and point to each finger in turn as we say each word

in the sentence. One finger is usually used for each word. This technique is

particularly useful when learners have left out a word or when we want them to

use a contraction, for example I’m working rather than l am

working. We bring two fingers together to show

that we want them to bring the two words together.

·

Gestures and/or facial

expressions are useful when we do not want to

interrupt learners too much, but still want to show them that they have made a

slip. A worried look from the teacher can indicate to learners that there is a

problem. It is possible to use many different gestures or facial expressions.

·

Phonemic symbols. Pointing to phonemic symbols is helpful when learners make

pronunciation mistakes, for example using a long vowel /u:/when they should

have used a short one /u/, or when they mispronounce a consonant. You can only

use this technique with learners who are familiar with the relevant phonemic

symbols.

·

Echo correcting means repeating. Repeating what a learner says with rising

intonation can

show the learner that there is a mistake somewhere. You will find this

technique works well when learners have made small slips which you feel

confident they can correct themselves.

·

Identifying the mistake. Sometimes we need to identify the mistake by focusing

learners’ attention on it and telling them that there is a problem. This is a

useful technique for correcting errors. We might say things like ’You can’t say

it like that’ or ‘Are you sure?’ to indicate that they have made a mistake.

·

Not correcting at the time when the

mistake is made. We can use this technique

to give feedback after a fluency activity, for example. It is better not to

correct learners when they are doing fluency activities, but we can make notes

of serious mistakes they make. At the end of the activity, we can say the

mistakes or write them on the board and ask learners what the

problems are.

·

Peer and self-correction. Peer correction is when learners correct each other’s

mistakes.

·

Self-correction is when learners correct their own mistakes. Sometimes we

need to indicate that there is a mistake for the learners to correct it.

Sometimes they notice the mistake themselves and quickly correct it. Peer and

self-correction help learners to become independent of the teacher and more

aware of their own learning needs.

·

Ignoring mistakes. In fluency activities we often ignore all the mistakes

while the activity is in progress, as the important thing is for us to be able

to understand the learners’ ideas and for the learners to get fluency practice.

We can make a note of frequent mistakes and correct them with the whole class

after the activity. We often also ignore mistakes which are above

the learners’ current level. For example, an elementary learner telling us

about what he did at the weekend might make a guess at how to talk about past

time in English. We would not correct his mistakes because the past simple is a

structure we have not yet taught him. We may also ignore mistakes made by a

particular learner because we think this is best for that

learner, e.g. a weak or shy learner. Finally, we often also ignore slips as

learners can usually correct these themselves.

Written mistakes

Can

you remember how you felt as a learner when your teacher returned a piece of

written work? Many learners say they want to have all their mistakes corrected,

and some teachers still believe it is a good thing to correct every mistake.

But it can be very discouraging for your work to be covered in red marks, with corrections

written in between the lines, and a single word at the end, or maybe just a

tick.

The key question for teachers to ask themselves is

what students learn from this kind of total correction. The answer is probably

very little. If everything is corrected, learners will probably look over their

work without thinking enough about any individual mistakes. Even if they do pay

more attention to the corrections, this method does not involve them in any kind

of learning process — they simply look at the corrections and teachers hope

this means that they will not repeat the same mistakes.

So, what alternative methods can we use?

Selective correction With this method the

teacher still gives the correction, but focuses on one or two areas (e.g. verb

tenses, use of prepositions) while ignoring other mistakes. The students are

told in advance what the correction focus will be, which should make them think

more carefully about those particular aspects when they are writing.

Signposting. One way of getting students to take a

more active part in the correction process is just to indicate where there are

mistakes, leaving students to think about what is wrong with what they have

written and correct it themselves. The ‘signpost’ can be a mark in the margin,

indicating that there is a mistake in a

particular line (or two marks if there are two separate mistakes in one line),

or the mistake can be underlined, giving the student a precise indication of

where the mistake is.

Correction code

Another method that involves students and makes them think about how they can

correct their own work is the use of a ‘correction code’, a set of letters and symbols

which make it clear what kind of mistake they have made. For this method to

work well, it is important to keep the number of symbols to a minimum and for

all the students in the class to know the code. If two colleagues are teaching

the same class, they also need to agree on a common code, so as to avoid any

confusion. In the box below there is an example of a correction code. But it is

only an example — you may prefer to use more or fewer symbols, and to create

some of your own. The important thing is for students to be absolutely clear

about what each of the symbols means.

Correction

code

Gr = grammar

P = punctuation

V = vocabulary (wrong word)

Pr = preposition

? = I don’t understand what you have written. Please

explain.

Sp = spelling

WO = word order

T = wrong verb tense

WF = wrong form

N = number / agreement (singular vs. plural)

л= something missing

0 = not necessary

With both signposting and the correction code,

instead of just handing outcorrections, the teacher introduces an extra stage

of learning, where students have to identify, or at least think about, the kind

of mistake they have made, and correct their own work. We remember things much

better when we have to make an effort to find the answers ourselves. It also

means that rather than correcting every mistake, the teacher has to stop

and think about why the student has made a mistake. Is it just a careless mistake

that could be made by a native writer? In this case it may not even be

necessary to point it out. Or is it an error that is repeated

throughout, which might be because of first language interference? Or is it the

result of the student being ambitious and attempting to find a way of

expressing something which is beyond his or her current level?

If this is the case, the teacher needs to think about whether or not

the student will be able to correct it.

How can self-correction be managed in the

classroom?

Individual self-correction

Students attempt to discover the problems, make

their own corrections (perhaps using a different coloured pen) and return their

work to the teacher. This gives the student the opportunity to reflect on their

mistakes and make improvements to their writing. It also shows the teacher what

the learners are able to do and what still remains difficult or unknown. The

teacher now has to check the corrections, and give the student feedback on

anything that is still wrong or that the student has been unable to improve.

Peer correction

Students work in pairs, or in small groups. They

exchange their papers and attempt to correct each other’s work. Again, the teacher

has to build in an extra checking stage, as students will often not be able to

provide appropriate corrections. But as with individual self-correction, the

students have to go

through a process of reconsidering what they have written.

Whole-class correction

The teacher

selects several common errors made by the students and highlights

them on the board for the whole class. Students then continue to correct their

own work, either individually or in pairs or small groups.

How can the teacher deal with items that students

are unable to correct for

themselves?

One of the ways that you can help students improve their

written work most effectively, is to take a short part of what they have

written, and rewrite it yourself, as you would have written it, without regard

to what they have actually written linguistically, taking only the content of

what they say. Just going back over their mistakes is likely to be less

effective than looking at a simple short piece of language well constructed

which they can compare with their own.

Remedial teaching

If students repeatedly make the same mistakes, or

are unable to correct

themselves, the best response from the teacher may be to use these items as the

basis for planning remedial teaching in future lessons.

Teacher feedback

Once

the students have corrected as much as they can, the teacher can concentrate on

the remaining problems. Rather than just correction, students need to

understand why they have made the mistake and how to put it right. At this

stage students need feedback from the teacher — some kind of explanation of the

particular language point and perhaps one or two examples to show them how the

language should work. Ideally, feedback would take place in a one-to-one

tutorial session, but with a large class this may not be practical, and feedback

can take the form of written notes at the end of the student’s work.

REMEMBER!

· Correct

promptly for accuracy, afterwards for fluency

· Don’t

over-correct

· Re-formulation

is often better than correction

· Give

students the chance to correct themselves

For reference:

· Ken

Lackman «Error Correction Games for Writing»

· Michael

Lewis, Jimmie Hill «Practical Techniques»

· Alan Pulverness « The

TKT Course»

Transcripts

Part 1 — Why correct?

Here’s a question to begin with. Which of these statements do you agree with more? ‘Errors are evidence that learning is taking place’, or ‘Errors are evidence that learning isn’t taking place’? I’m Jo Gakonga from elt-training.com and in this series of three videos I’m going to be looking at error correction. So I’m going to be looking at why you might correct, I’m going to be looking at what you might correct. And finally, of course, perhaps most importantly, I’m going to have a look at how you might correct learner error.

If you take a strictly behavioral approach to language learning, you might think that learners have to avoid error. They need to make sure that they know what they’ve got to do, that they get lots of practice of it, that they’re praised when they do it right and they’re corrected when they make mistakes.

Now, there aren’t many people in education these days who would see learning like this, as just a conditioned response. But error correction is a really important part of language learning — of that whole process. And I think that there are two really good reasons for correcting error. The first one is that it works. Simple as that, it works. There’s lots of really solid research evidence to show that error correction is a very powerful learning tool. I’d really recommend John Hattie’s work ‘Visible Learning’ on this, if you don’t know about it, it’s really, really interesting. And his work shows that feedback error correction is one of the most important ways in which learning happens. Without being corrected, learners errors tend to fossilize, and then they’re difficult to change. And it’s not just about correcting for the sake of it. If you make a lot of error, then for your listener, it’s really hard for them to understand you. And that does cause problems. Maybe they won’t want to listen to you very much either. It makes it more difficult more of an effort to understand, even if those mistakes are small.

The second reason, to focus on error correction — and this is a big one — is that learners expect it and that learners like it. So they won’t usually be corrected — if they’ve got English speaking friends and they’re just talking in a conversation, those friends aren’t usually going to correct them, it would be considered rude probably and certainly probably be irrelevant. So in a classroom is their opportunity to be corrected, and they usually feel quite positive towards teachers who do this. Of course, it depends on how it’s done. But I think that if you correct learners, they feel as if you’re listening to them, and they feel as if you care about their progress. This is really important.

There is a ‘but’, of course — language, as I said, isn’t just about conditioned learning, and if we try to correct every mistake they make, especially at lower levels, they would never say anything. Also it can be rather demotivating. If you correct a lot or if you correct insensitively, then you know learners may end up just giving up. There’s a balance to be had, of course, as in many things in life, but the balance may be further down this end, then you feel naturally inclined to.

I hope I persuaded you that it is a good idea to correct learner error. So in the next part, let’s go on to see what kind of things you can correct, how you’re going to choose what to correct and why learners perhaps make some of those errors.

Part 2 — What to correct?

Hello again. In the first video in this series, we looked at why you should correct learner error in class. But before we think about how to do this, let’s take a minute to think about what it’s useful to correct. I’m Jo Gakonga from elt-training.com and if you like this, there are lots of other helpful video-based courses and resources on my site.

Learners of English make mistakes, of course, but those errors don’t always have the same cause. So let’s think about the different root causes of those errors. The first one, of course, is just the level of ignorance. The obvious reason for an error is that the learner just hasn’t learned that vocabulary or that form yet. And of course, this is especially true at lower levels. But it can happen with any level of learner.

Here’s an example — ‘I will can come later’. So this learner hasn’t yet learned the phrase ‘be able to’, or they don’t know that we can’t have two modal verbs together. So they’ve done their best to express their meaning, using the words that they do know. Now you understand what they mean, it’s not that difficult to pull apart, but you need to teach them how to say it.

Another very obvious reason that learners make mistakes is that the language they already speak, their L1, is getting in the way. Now this can be manifest in all sorts of ways, pronunciation, of course, is a really huge aspect of this. Languages have different sounds and some just don’t map onto each other. Mostly they don’t map onto each other exactly.

So different sounds can be a major source of error. And this also goes into intonation, word stress, sentence stress, all of those things often have different patterns too. And so that will affect the learners’ L2 English in this case.

Some grammatical forms exist in some languages, but not in others. So articles are a good example. English has them. And it has a plethora of rules of how you use them. But many, many languages do perfectly well without them. And so they’re hard to remember to use if they’re not in your first language.

Between European languages in particular, there are lots of cognates, like ‘table’ in French, and this can be really helpful. But there are also some false friends, words that look the same, but aren’t. So if you know this word in Spanish, you might be expecting ’embarrassed’ to mean the same thing. But it doesn’t.

Another issue is word order, that’s often different between languages, and that’ll cause problems.

The list of these reasons for error is really, really long. And if you teach learners from a particular language group, then of course, it’s a very good idea for you to know something about that language, so that you can see the kinds of difficulties that they’re likely to have — the holes that they’re likely to fall into because of their L1. Preferably, of course, you’d speak their first language yourself.

Some error is caused because learners are experimenting with what they already know, but they’re over generalizing. So, ‘I got on the car’ is incorrect. But it’s a perfectly reasonable assumption, given that ‘I got on the bus’ is perfectly right. So a learner that says ‘they builded a house next door to me’, is making a guess, perfectly reasonable guess, but it’s an incorrect guess that ‘build’ has a regular past tense. It doesn’t.

Another reason that learners may care is just because they make mistakes. They know the language. If you prompt them, they can almost certainly self correct. But they’re trying to make meaning in real time. It’s getting from their brain to their mouth in real time. And it’s just difficult. It’s hard to make that connection fast enough. And so, error occurs. This happens with native speakers too of course. Learners at all levels right up to advanced will do this, for example, leaving out the auxilary ‘do’ in questions, or that notorious third person ‘s’ on the Present Simple.

Why is this important to consider when we choose what to correct? Let’s think about it. If the learner makes the error because they don’t know that form yet, then it’s not an error. They just don’t know it. So the answer is, teach it to them or keep it in mind to teach in a future lesson at least.

If they make the error because of L1 interference, or because of overgeneralization, then it’s very helpful to show them why they made that mistake. It’s like this in your language. But in English, it’s like this. We do say ‘on the bus’, but it’s ‘in a car’.

And finally, if they’ve just slipped up, then a simple facial expression or a recast — ‘how long do you play the guitar?’ — will probably prompt them to self correct.

One final thought before the end of this. And I’ve already said that you can’t and shouldn’t try to correct everything. So how do you choose? I think that there are a few ways to prioritize this. If your target language is the simple past, then you should be correcting that. Second is errors which affect intelligibility. If you can’t understand them, then they need to know because other people won’t understand them either. Third one is the frequency of the error. If they all make this error all of the time, then it’s definitely something you should be correcting. And finally, the likelihood of success. It’s best to save correction for language that they’re ready for. And at a time in the lesson, when it’s likely that they’ll take it on board.

So we’ve looked at the why and we’ve looked at the what of error correction. So now let’s go on to think about how you’re going to do it.

Part 3 — How to correct?

Hello again, this is our third and final video on error correction. We’ve looked at why? And we’ve looked at what? Now, of course, what you want to think about is how you’re going to do it? I’m Jo Gakonga, from elt-training.com and if you like this, there are lots of other videos on the site that you might also find helpful.

Okay, I want you to imagine that you’re in a class and a learner makes an error. What’s the first question? First question is, who is going to correct that error? Now, it could be the learner themselves. It could be one of the other learners in the class, or it could be you as the teacher. Now, who it is, depends a little bit on whether it’s a mistake that the learner can correct themselves, or whether it’s just a slip, or whether it’s something that they don’t know yet. Generally speaking, though, as a rule of thumb, if you think it’s something that they can correct, then try the learner first, then their peers. And if nobody knows, then you tell them, you’re the teacher.

Now, there are a few different ways of doing this. The first is implicit correction. This is called recasting. It’s what parents do to young children all the time. They repeat what they said, but in a correct form. So the teacher says, ‘What did you do at the weekend?’ And a learner says, ‘I go cinema’. And the teacher says, ‘Oh, you went to the cinema’.

Now, there’s mixed research evidence here about whether this is effective or not. It really depends a bit on whether the learner actually notices the correction or not? If you think that they’re likely not to notice or that they haven’t noticed, then you could try something more explicit. ‘What did you do at the weekend?’ ‘I go cinema’. ‘I go cinema?’ Or, ‘there’s an error in that sentence, try again’. Or you could use your fingers to show there’s a mistake. ‘I go cinema’, ‘I went to the cinema’. Or you could use meta linguistic strategies like this — ‘past tense?’

Or if there are pronunciation problems, for example, ‘Look at my teeth see, they’re touching my lip. Now. vvvv… not berry, very’. Or you could point to the symbol on the phonemic chart.

So those are some thoughts about how you could correct, but what about when? Should you correct the error as soon as you hear it, or wait until the activity is finished and have a delayed error correction slot? Again, there’s research here that says that the most effective form of correction is that that happens immediately. But, if the learners are busy engaged in a freer speaking activity, and you don’t want to disturb them, then a delayed error correction activity might be better. I would say again as a rule of thumb, that in the presentation stage, and the control practice stage, that I would do correction on the spot — definitely correct your learners as you hear their mistakes. But when they’re involved in a fluency activity, or a freer practice activity, then collect up those errors, and show them afterwards.

There are a couple of real advantages to this, actually, after a fluency exercise, you could put up on the board about four to six different examples of errors that you heard, especially error with the target language, or error that’s particularly frequent that you think is a good idea to draw their attention to. The advantage of this is that it’s anonymous. If I said that, if I made that mistake, I know it was me. But nobody else in the class except possibly my partner does. So it’s not so embarrassing, so that’s good. It’s also helpful for the other people in the class, they get to benefit from my mistake if you like.

Now, give them some time in pairs to talk about these mistakes and try to correct them together. So it’s again a more learner centered approach to this. You could also use it as a way of drawing attention to good language. So maybe have within those four to six, have one example of some good language that you heard and tell them one of these sentences is correct, and they have to find out which one’s the correct one as well as correcting the mistakes. I think this helps to focus them a bit more as well.

So that’s it, some thoughts about error correction. I hope that this was helpful. If you found it so then there are lots of other videos on my CELTA toolkit that are about classroom management. So you might like those. Please don’t forget to like and subscribe to my YouTube channel and I look forward to seeing you on the site. Thanks very much. Bye bye

Hello Exam Seekers,

What is feedback? How can you give feedback to your students? How do you correct your students? Did you know that there are specific error correction techniques? Well, in this text, I’m talking about the relationship between error correction and feedback, error correction’s place in class, and also some techniques that you can use when correcting students.

This topic is actually one of the ways of giving feedback that you learn during the CELTA Course. You not only learn, but you should use these techniques while teaching your class, and when planning your lessons, you should write the names of the techniques you plan to use.

FEEDBACK AND ERROR CORRECTION: How are they related?

To begin with, it is quite impossible to talk about error correction without talking a little bit about feedback, right? After all, we tend to not only correct our students but also praise them during their learning process. And since feedback is mainly used to bring awareness of students’ improvement and development, both aspects should be considered when talking about the students’ progress in the learning of a foreign language.

Also, I have already talked about errors and how you should not be scared of making mistakes when learning a language – or pretty much anything. This is because mistakes are part of the learning process and it shows that learners are attempting to use the language; therefore they are, one way or the other, making progress. It is by receiving feedback on their performance that they can start realizing what is correct and what is not, so that is why teachers should point out the aspects they excelled in and also the ones they need improvement. As for the teachers, it is also by the mistakes students make by using the language freely that they can evaluate what should have more practice and what has already been learned appropriately.

There are different types of errors, though. They may include, pronunciation, grammar, vocabulary, coherence, and so on. So a tip would be to try and vary the aspects which you are taking into account when giving feedback to students. Additionally, the level of the student should be in mind when they make mistakes. For instance, if it is something they haven’t learned yet, what is the point of bringing the issue up, right? Instead, it is much worthy to focus on things students have already learned and are still having trouble with rather than going too much further and taking the risk of making students confused and demotivated.

Another aspect to think about is the most appropriate time to have these corrections. For example, should you interrupt the student in the middle of their talk or wait for them to finish and correct them at the end of the activity?

Below is an example of how correction done at the wrong moment can impede communication:

ORAL CORRECTION: On The Spot x Delayed Correction

Some mistakes can be corrected right on the spot when students are still talking, while others can be a group problem or something that came up more than once during the lesson and should be worked on later on as a delayed correction.

For instance, if it is a structure that perhaps needs more clarification and that is still an issue for some students rather than something rare, it may be worth writing them on the board and do it as a delayed group correction. On the other hand, if it is something that may have happened as a slip while a student was talking and it is not going to compromise their talk and is not something recurrent, you can do it on the spot and deal with it the moment it happens. It is just important to bear in mind if this correction will be effective or will end up doing more harm than good.

SOME TECHNIQUES: How to correct students effectively

Exercises/Worksheets: One type of correction that can be done is bringing some sentences with the mistakes students usually make and work on them at the beginning or at the end of a lesson so that all of the students have the opportunity to think about the errors and correct them together. Some options could be a fill-in-the-blanks sort of exercise or even one with the sentences for them to spot the mistakes. Another possibility is to work with matching if students have been working with idioms or expressions and still making some mistakes on this issue.

Cuisenaire rods: this may be one of the most versatile ones, mainly because you can use it to work with pretty much everything! You can use it when students are having some issues with the order of a structure, to show the correct position contrasting to the one they are using. Also, you can work with pronunciation patterns, such as word stress – put two blocks on the stressed syllable, for instance-, the stress in a sentence, the syllable division, and even the intonation. Since each block has a different color and size – there are ten different colors and sizes in each set – they can represent each a part of speech, or a different pattern, depending on what you plan to work on.

Fingers/Hands: I believe that gestures can be used for even more situations than Cuisenaire Rods, to be honest. After all, some signs are the same in many places around the world, so it is something that can be helpful in many situations. However, I will tell only a couple of them here. For example, if a student is saying a verb in the present when they should be using the past, you can point your thumb behind your shoulders to have them think about the past situation. Besides, the opposite also works. If you need a student to change the verb for the future, you can also roll your finger forward to indicate that it is about the future.

Another gesture you can use your fingers to correct students is when they are saying a sentence and the position of a word is incorrect. You twist your index and middle finger to point out where it should be – by twisting your finger, students would understand that they were supposed to invert the sentence.

Also, you can use each finger to represent a part of the sentence and stop where the mistake is to have students come up with the most appropriate answer – or even ask them to do it after you give another example with the correct order, for example.

The picture on the side is another example of how we can use fingers. If a student said “I ate too much cookies” you can repeat the sentence by saying “I ate too _____” and hold your ring finger expecting the student to repeat the words or correct him/herself. If the student says the wrong word, with a headshake he/she will understand he did it incorrectly and will try again.

Other students: If you are teaching a big class or even one with a reasonable number of students, you can also use the students themselves to help you with the error correction in a sentence. You may have each student represent one of the words of the sentence, and then the other students have to point out where the mistake is and come up with the correction. This helps reduce TTT (Teaching Talking Time) and also has students more in control of their learning as well since they will be working together to solve the error.

SOME TECHNIQUES TO BE CAREFUL WITH

Some techniques should be used carefully when correcting students. For instance, teachers should mind their tone when students say something incorrect, as the ‘mocking tone’ may inhibit students from developing and even trying with the language. So, echoing students’ mistakes, making fun of them somehow may not only be rude but also silence a student for the rest of the course at times.

Besides that, avoid reactions such as “No!“, “That’s not right,” “You’re wrong,” the moment you listen to a student’s mistake. Wait for the student to finish their sentence and use some more positive stimuli to help them rephrase the sentence or work on what was not correct, such as asking them to try again or even showing them where the mistake is and asking for help to make that right.

So, what do you think about these suggestions? And what about you? Do you use any other error correction technique when working with your students? And during the CELTA? Have you planned on using one, but in the end decided on another? Tell me in the comments. And if you have questions or comments, just leave them in the comment section below.

————x————

That’s it for today! Please like the post and follow the blog on:

- youtube.com/c/ExamSeekers

- facebook.com/ExamSeekers

- instagram.com/ExamSeekers

- twitter.com/ExamSeekers

You can also listen to this post at Anchor!!!

Have a great week,

Patricia Moura

Make a one-time donation

Thanks for making this possible! 🙂

Donate

Make a monthly donation

Thanks for making this possible! 🙂

Donate monthly

Make a yearly donation

Thanks for making this possible! 🙂

Donate yearly

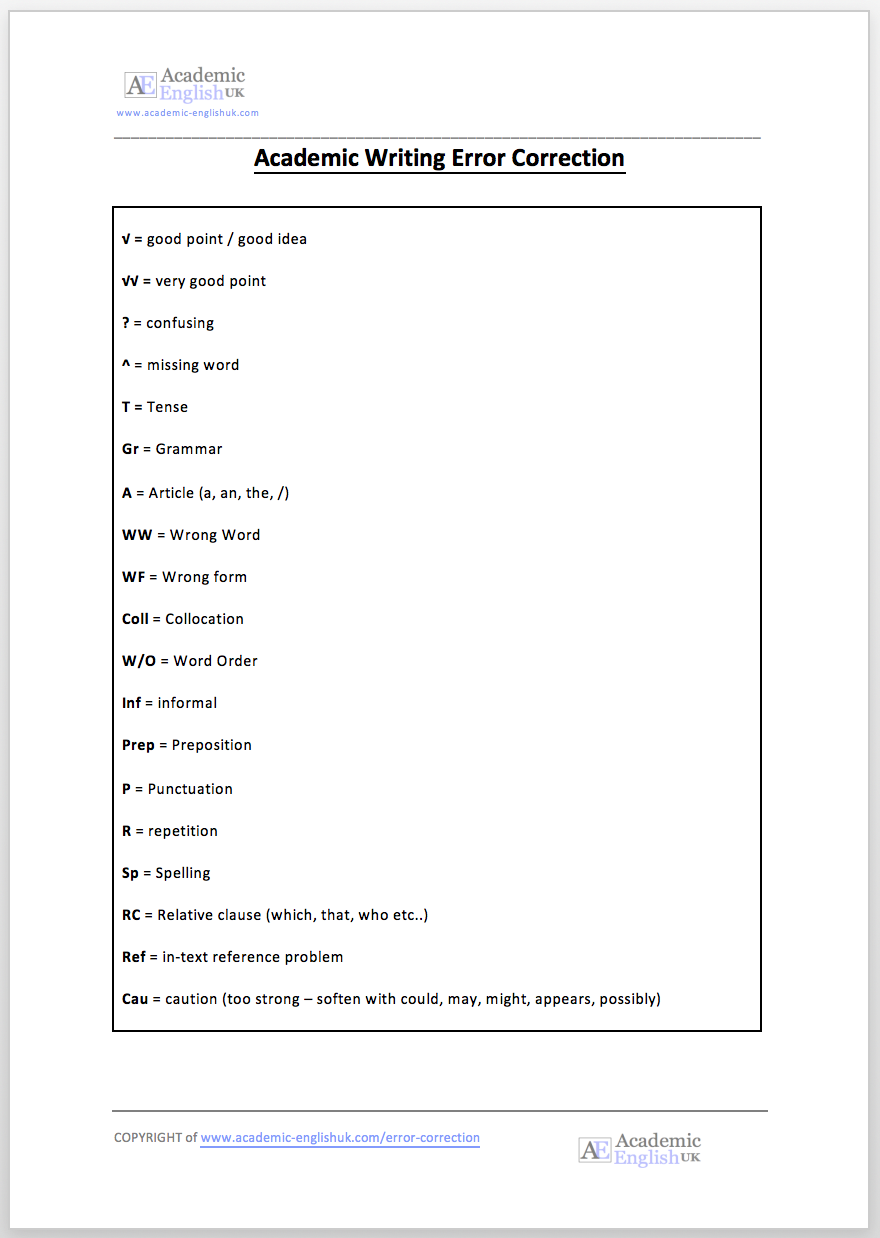

This page includes a standard error correction symbol code. Use these symbols to highlight key mistakes in a student’s work.

This is a 3-way system.

1) Tutor marks the mistakes using the correction code and returns to the student.

2) Student makes correction in a different colour pen and returns to the tutor.

3) Tutor checks the corrections and returns to the student.

Reason: This way the student learns from their mistakes and takes more responsibility in correcting errors and learning from mistakes.

Higher Level Error Correction Practice Worksheet

Error Correction Code 2: High levels practice & answers

Teachers or students: This is a much harder worksheet of 12 sentences with 3 or 4 mistakes in each sentence. Students identify the mistake and try to correct it. TEACHER MEMBERSHIP / INSTITUTIONAL MEMBERSHIP

More digital resources and lessons

Advertisement: (Improve your listening skills: Amazon Audible Special Offer: 30 day free trial)

Introduction

Whenever anyone learns to do something new, it is extremely rare for them to be able to perform it perfectly on their first attempt. The same must also be true with learning a new language. Children acquiring their mother tongue within the critical period will often also make errors, however, they will often naturally be corrected over time.

The Critical Period Hypothesis (CPH), was proposed by Lenneberg in 1967, which suggested the learning of a child’s first language happens naturally before the age of puberty. Although other writers disagree to an extent over where CPH is true, most people accept learning a new language after the Critical Period is over is more difficult (Newport et al 2001).

When Krashen based his “Natural Approach” (Krashen, 1983) on the CPH, he believed that errors were signs that natural development was occurring. Krashen further defined acquisition of a language, as developing language proficiency by communication, as opposed to learning which required formal teaching and error correction. Moerk, (1994) showed that even when acquiring your mother tongue correction is needed to improve. This essay will be looking into what, how and when errors should be corrected.

What should be corrected in language learning?

There is a clear need to give correction however, the impact of too much feedback can also be detrimental to student motivation (Hattie & Yates, 2013). This makes it more important to prioritise which errors to correct. When considering which errors to correct Hendrickson, (1978) suggested correction based on the student’s ability, starting with errors that affect commutation, then common errors, finally errors that will irritate. Following on from this, it is clear that you will need to correct beginners differently from advanced students. Furthermore, it is worth considering abstaining from correcting specific errors until you have introduced that area of knowledge to the students, for example, if you were correcting sentences for students trying to use the past perfect continuous when the students are still coming to grips with the simple past.

Teachers should correct mistakes based on what the students have previously learned, rather than errors they use from trying content they are as yet unready for. This is in line with Chaudron’s work (1988), which summarised students should be corrected when their error is the focus of the lesson. It is also important to correct mistakes in things previously studied, as peers hearing the mistake will question their understanding of what they’d previously learnt (Allwright,1981).

When to correct mistakes in language learning?

I will concentrate on when, to correct errors and mistakes occurring in oral speech, as written mistakes are not as time-sensitive and will be visible for much longer. The time at which you correct may depend on several factors such as what you are teaching. For example, if you happen to be teaching new vocabulary words and a student mispronounced one. You will likely correct the mistake right away, whereas if you were teaching reading fluency and a student mispronounced a word, you would probably wait until the end of the reading to correct it.

Other factors which will determine when teachers choose to correct mistakes are student confidence and class flow. Teachers should be careful not to interrupt the flow of class with excessive feedback. For example, you could share feedback with a single student after the next task has started, this will also help to reduce embarrassment. I should also mention the possibility that if errors are left uncorrected, the students will develop a habit of repeating the same mistakes. This is known as the error becoming fossilised, which will be more difficult to correct, at a later date.

How should teachers correct mistakes?

There are many ways to correct mistakes that occur in oral speech. A teacher will often use many different ways in a single lesson. I will list a few that are commonly used.

-

Echoing, or repeating the mistake, can be used with a questioning tone. This will give the student a chance for self-correction. Echoing is often useful if you believe the mistake was a slip. Common slips like she/he or third person can be brought to students’ attention by this method.

-

Gestures indicating an incorrect tense, for example, behind could mean you were expecting the past tense. Even raising your eyebrows could be a clue that something isn’t correct.

-

Another example I remember reading about a teacher who stuck a big “S” on a wall and pointing to it every time students forgot to use the third person. Later the «S» was removed, but they would still point to the wall. Teachers can agree on gestures with the class previously.

-

Repeating the sentence up until the mistake will give the student a chance to understand where in their sentence the mistake had occurred. This would again give them the opportunity to self-correct.

-

Using fingers again while repeating the sentence to show where a word was missing. Can be used when students miss words like “a” or “the”.

-

Recasting, I am not a fan of this one, as it gives students the correct answer and doesn’t give them a lot of chances to reflect on the mistake. I can see this being used for words that have been mispronounced as they should hear a good model rather than continuing to guess as to what the correct pronunciation is.

-

Contrast the correct and the incorrect forms, for example, “I’m loving it” or “I love it” which do you think is correct? Let’s discuss. (sorry McDonalds).

-

Peer-correction, if the student is unable to self-correct, maybe a peer can help correct it. This can be done by asking another student to help. This may also be achieved by allowing peers to give suggestions and let the student chose which is the correct answer.

Correcting written errors

Similarly, to correcting oral mistakes too much correction can be disheartening for students. Many teachers will use a correcting rubric this can be shared with students so that they try to correct their mistakes. Examples of such a rubric may be using “sp.” to indicate a spelling mistake. It is advantageous for students to have a chance to try to self-correct their mistakes before the teacher looks again to share the correct answers.

Tasks where students share and critique with their classmates’ work is also useful to help students become aware of their mistakes. It’s also useful to help them become more aware of different writing styles and gain ideas for their works. When giving feedback on written work it is important to understand feedback received is not the same as feedback understood. The most effective feedback is that which includes what the next step is (Hattie, 2013).

Conclusion