From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Error management theory (EMT) is an extensive theory of perception and cognition biases created by David Buss and Martie Haselton. How humans think and make decisions using heuristics and biases may be embedded in the human brain. Error management training is a related area that uses this theory. The objective of it is to encourage trainees to make errors and encourage them in reflection to understand the causes of those errors and to identify suitable strategies to avoid making them in future.[1]

Ebbinghaus–Titchener circles

An example of error management theory is the Ebbinghaus–Titchener circles that can illustrate, a person’s view of which of the (orange) centre circles is bigger is subjective, and can cause a misinterpretation of reality. That is to say, both circles are the same size but each person may interpret the information presented differently depending on which bias they rely on to make the decision.

Various biases in thinking and decision-making have been highlighted by Daniel Kahneman and have been shown to cause cognitive errors in psychological and economic decisions. Cognitive biases in error management theory refer to biases and heuristics that have survived evolutionary history, because they hold some benefits towards reproductive success. Based on Darwinian principles those that «out mate» others have a greater chance of successfully producing offspring. According to this theory, when there are differences in costs of errors made under conditions of uncertainty, selection favours «adaptive biases». Humans are animals, and evolution charts their passage from single celled organisms to the media and technology-consuming organisms of today. These adaption biases ensure that less costly survival or reproductive errors will be committed.

Error management theory asserts that evolved mind-reading agencies will be biased to produce more of one type of inferential error than another.[2] These mind-reading biases have been further researched in terms of the mating world. Error management theory provides a clear explanation for the discovery that men have a tendency to perceive women as having greater sexual interest in them than is present, if they smile or touch them, and females have a tendency to underplay a man’s interest in them, even if it is quite strong. This is based on commitment scepticism. The theory has been much replicated,[failed verification] but the authors are still[when?] testing and refining it.[3] Newer research indicates exceptions as well as gender differences may be significant to the effect, such as postmenopausal effects, the possible projection of sexual and commitment self-interest,[4] and other differences including unrestricted sociosexuality.[5]

Type errors[edit]

In the decision making process, when faced with uncertainty, a subject can make two possible errors: type I or type II.

A type I error is a false positive, thinking that an effect is there, when it is not. For example, acting on a fire alarm that turns out to be false. When someone infers sexual interest, where there is none, then a false-positive error has occurred.

A type II error is a false negative, not seeing an effect where one exists. Ignoring the fire alarm that turns out to be accurate, due to scepticism, illustrates this point. Falsely inferring a lack of intent about sexual interest means a false negative error has occurred.

Sexual overperception bias[edit]

Males[edit]

One of the aims of error management theory is to explain sexual overperception bias.[6] Sexual overperception occurs when a type I error is committed by an individual. An individual committing this type error falsely concludes that someone else has a sexual interest in them.[6] Research has shown that males are more likely than females to commit sexual overperception bias – men tend to overestimate women’s sexual interest while women tend to underestimate men’s.[6] This is theorised to be likely due to the fact that the reproductive costs of sexual underperception are greater for men than the risk of making false positives.[6] Men who perceive themselves as especially high in mate value are especially prone to experiencing this phenomenon. In addition, men who are also more inclined to pursue a short term mating strategy exhibit a more prominent case of sexual overperception bias.[7]: 334

Manipulation[edit]

Differences in perceptions of sexual interest between men and women may be exploited by both genders. Men may present themselves as more emotionally invested in a woman than they actually are in order to gain sexual access to her; 71% of men report engaging in this form of manipulation and 97% of women report having experienced this form of manipulation.[7] Women may present themselves as more sexually interested in a man than they actually are in order to fulfill other needs and wants.[7] The manipulations create conflicts between men and women as to the status of their relationships. Women on the receiving end of emotional manipulation may complain that the relationship is moving too quickly while men on the receiving end of sexual manipulation may complain about «being led on».[7]

Exceptions[edit]

The sister effect[edit]

The sister effect is an exception to male overperception bias. Haselton and Buss (2000) found that sexual overperception bias would not occur when the target the men had to perceive sexual intent from was their sister.[8] They found that the men’s perception of their sister’s sexual intent was lower than their perception of sexual intent from other females. Haselton and Buss (2000) believed that this perception of female sexual interest was most accurate as it fell between women’s perception of women (high interest) and women’s perception of their own sexual interest (low interest).[8] This could be a product of incest-avoidance mechanisms.[7]

Sexual and commitment self-interest[edit]

Sexual underperception in males is also observed, in cases where men report low levels of their own sexual interest.[6] A person’s own level of attraction, rather than their gender, may lead to over or under-perception.[4] The exact mechanism for this is unclear but it is suggested that individuals may project their own level of sexual and commitment interestedness on to their interaction partner, whether they are in a relationship with them or they were strangers before the interaction.[4]

«The Fox and the Grapes»[edit]

The Aesopian fable of The Fox and the Grapes gives another possible explanation as to why males fall victims of underperception. The fable concerns a fox that attempts to eat grapes, but fails to do so, as they are too high. The fox, being too proud to admit defeat, claims that the grapes are «sour» and thus inedible.[4] In a similar fashion, males that expect a female to be uninterested may report less sexual interest, as an attempt at saving face.

Male insensitivity bias[edit]

A different explanation for the presence of both overperception and underperception in men is the male insensitivity bias. Evidence has shown that males lack perceptual sensitivity, so they are more likely to misperceive friendliness as sexual interest, but also more likely to misperceive sexual interest as friendliness, in comparison to females,[9] something that explains the presence of both biases in males.

Sexual underperception bias[edit]

Females[edit]

Women also fall victim to misconceptions during male-female interactions. Haselton and Buss (2000) advocate that these errors primarily stem from women’s perceived desire for a committed relationship by a male counterpart.[7] Women have evolved strategies to protect themselves from deception.[10] One of these evolved strategies is to commit the Skeptical Commitment Bias.

Skeptical commitment bias[edit]

Women’s commitment skepticism arises from the high costs of falsely inferring a mate’s commitment to a relationship. It hypothesizes that women have adapted to be cognitively biased towards under perceiving male interest and commitment. This is due to the high cost of a false positive – a man not being committed and a woman accepting him – that could lead to raising a child without an investing mate, reputational damage and risk reducing chances of future courtship. The cost of a false negative – a man that is committed and a woman rejecting him – is far less costly to the female.

Women are limited to how many children they can have in a lifetime. However, men are not limited and can reproduce multiple times. Therefore, overperception costs are higher for females.[11] This hypothesis is mentioned briefly by Buss (2012).[7]

Females’ commitment skepticism is unique to humans. For other mammals, courtship rituals are not particularly varied and there is no guesswork or ambiguity involved. For instance, a long-tailed manakin bird has a mating dance that is instinctive and intricate and requires a young apprentice to perform as a duet to the female. If the dance is good enough the female will mate with the male, if the duet falls flat then she will not choose him to reproduce with. However, human courtship behaviour is more ambiguous and so requires these types of cognitive biases to avoid costly errors, in this case, sexual deception.[6]

Exceptions[edit]

«Skeptical dad» and «Encouraging mum» hypothesis[edit]

Previously, commitment skepticism and overperception biases were thought of as sex specific. Women would underplay or fail to infer a psychological state that is there in order to prevent a false negative error. Men would over perceive female interest because the reproductive costs of sexual under perception are greater for men than women. Al-Shawaf (2016) stated that this is not what the core logic of the Error Management Theory (EMT) suggests. EMT states that the ancestral cost-benefit matrix of both false positive and false negative errors is what drives the cognitive biases and decision-making processes, not gender which is what it has been defined by.[12]

Imagine a woman is assessing her potential mate’s commitment intent. The woman’s father also has a vested interest in whether she reproduces because he shares genes with her and thus, his reproductive interests extend to his daughter’s mate choice. The father also has to evaluate the costs and benefits of the two types of errors she could make when evaluating her mate’s commitment intent. If the chosen mate sexually deceives and then leaves her then the outcome is more costly for him than if his daughter is more cautious and underestimates intent. Thus, the father might take time before offering his parental seal of approval. The father shows the same skeptical commitment bias as his daughter, favouring the false negative error because it is less costly.

Taking the parental dynamic and switching it from father to mother, the same could be said for sexual overperception bias. A mother has an interest in who her son decides to mate with and therefore will favour the false positive error over false negative. If she fails to detect real interest in the woman, and thus, fails to share this female interest with her son, then it is more costly to her than if she falsely detects sexual interest from a woman towards her son and encourages him to pursue. If her son misses an opportunity, he has missed the chance to pass on his, and in doing so her own, genes. Therefore, the mother shows the same overperception bias as her son, favouring the false positive error because it is less costly.

It is not sex or gender that predicts what type of cognitive bias might be expressed but rather the potential costs to reproductive success.

Postmenopausal females[edit]

Contrasting the evidence for fertile females, skeptical commitment bias does not occur in postmenopausal women. Haselton and Buss (2000)[8] found evidence for the perception biases studying young subjects; however, this was not representative of older females, who have passed through menopause. The reason for this disparity between pre- and postmenopausal females is that fertile females underestimate the intentions of males to invest in the relationship, in order to avoid the costs of pregnancy without support; however, postmenopausal women do not perceive such costs. Their inability to conceive means that there is no reason to underestimate a male’s intentions.

Alternative explanations[edit]

Some recent studies researching error management theory have found men and women’s perceptions of opposite gender sexual and commitment interest may be mitigated by other explanations.[5]

Culture[edit]

With a universal proclivity, it would be possible to document the bias across cultures and «across different demographic groups, including among men varying in age, ethnicity, and education level» within cultures[13] and in females based on their job status, health, levels of education and income equality.[5] When investigated in Norway, one of the world’s most gender egalitarian societies,[5] error management theory and its evolutionary explanation were supported. In addition, the pattern of misperception of men and women held up across demographic groups differing in relationship status (singles versus partnered participants).[5]

Individual differences[edit]

Sexual over-perception relative to under-perception was reported more frequently among younger participants, among singles, and among participants with an unrestricted socio-sexual orientation.[5] Endorsing and being more open to casual sex may have evoked more sexual interest from members of the opposite sex, leading to more frequent reports of sexual overperception.[4] Socially unrestricted male and female high school students were found to report being more subject to sexual harassment as well as sexually harassing others.[5] From this, it is possible that being subject to sexual over-perception may explain the link between socio-sexuality and being subject to sexual harassment.[5]

Projection[edit]

As stated above what was reported about male sexual and commitment self-interest was also true of women. They self-reported levels of sexual interest and desire for commitment which also predicted their perceptions of their partners’ sexual interest and desire for commitment.[14] This implies that instead of males and females falling victims of overperception and underperception respectively, both sexes project their own level of interest onto the individuals they are interacting with.[15]

Reciprocity[edit]

Another explanation that removes overperception and underperception from the picture is how males and females reciprocate the perceived interest in one another. Evidence from speed dating shows that a partner’s level of attraction for an individual, influences the individual’s own interest in that particular partner.[4] Unlike the «fox and the grapes» approach, which explains how underperception occurs in men as a means of face-saving, reciprocity reflects a real shift in the level of interest in a partner as a result of returning the perceived interest.

Other examples[edit]

Similar examples can also be seen in the judgment of whether a noise in the wild was a predator when it was more likely the wind—humans who assumed it was a predator were less likely to be attacked as prey over time than those who were skeptical. This is similar to the animistic fallacy.[clarification needed]

Smoke detectors are designed with this theory in mind. Since the cost of a Type I error (false positive, e.g. a nuisance alarm) is much lower than the cost of a Type II error (false negative, e.g. an undetected fire that could burn a house down), the sensitivity threshold of a smoke detector is designed to error on the side of Type I errors. This explains why nuisance alarms are relatively common.[16]

See also[edit]

- Reinforcement learning

Notes[edit]

- ^ Keith, Nina; Frese, Michael (2008). «Effectiveness of error management training: a meta-analysis». The Journal of Applied Psychology. 93 (1): 59–69. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.59. ISSN 0021-9010. PMID 18211135.

- ^ Buss (2012). Evolutionary Psychology: The New Science of the Mind. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-205-01562-7.

- ^ Haselton, Martie. «Error Management Theory: Overview and Significance». UCLA. Archived from the original on 2006-09-08.

- ^ a b c d e f Luo, S; Zhang, G (2009). «What leads to romantic attraction: Similarity, reciprocity, security, or beauty? Evidence from a speed dating study». Journal of Personality. 77 (4): 933–963. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00570.x. PMID 19558447.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bendixen, M (2014). «Evidence of Systematic Bias in Sexual Over- and Underperception of Naturally Occurring Events: A direct Replication of Haselton (2003) in a more Gender-Equal Culture». Evolutionary Psychology. 12 (5): 1004–21. doi:10.1177/147470491401200510. PMID 25402231.

- ^ a b c d e f Henningsen, David D; Henningsen, Mary Lynn Miller (October 2010). «Testing Error Management Theory: Exploring the Commitment Skepticism Bias and the Sexual Overperception Bias». Human Communication Research. 36 (4): 618–634. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.2010.01391.x.

- ^ a b c d e f g Buss, David (2012). Evolutionary Psychology: The New Science of the Mind. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. ISBN 978-0-205-01562-7.

- ^ a b c Haselton, Martie G.; Buss, David M. (2000). «Error management theory: A new perspective on biases in cross-sex mind reading» (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 78 (1): 81–91. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.78.1.81. PMID 10653507. Archived from the original on 2012-03-24.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Farris, C.; Treat, T. A.; Viken, R. J.; McFall, R. M. (2008). «Perceptual mechanisms that characterize gender differences in decoding women’s sexual intent». Psychol Sci. 19 (4): 348–54. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02092.x. PMC 2890253. PMID 18399887.

- ^ Abbey, Antonia (1982). «Sex Differences in attribution for friendly behaviour: Do males misperceive females’ friendliness?». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 42 (5): 830–835. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.42.5.830.

- ^ Ehrlichman, Howard; Eichenstein, Rosalind (1992). «Private wishes: Gender similarities and differences». Sex Roles. 26 (9–10): 399–422. doi:10.1007/bf00291551. S2CID 144522125. ProQuest 618242868.

- ^ Al-Shawaf, Laith (4 May 2016). «Could there be a male commitment skepticism bias and a female sexual overperception bias? Novel hypotheses based on error management theory». Evolutionary Psychological Science. 2 (3): 237–240. doi:10.1007/s40806-016-0052-x.

- ^ Haselton, M. (2003). «The sexual overperception bias: Evidence of a systematic bias in men from a survey of naturally occurring events». Journal of Research in Personality. 37: 34–47. doi:10.1016/s0092-6566(02)00529-9.

- ^ Koenig, B. L.; Kirkpatrick, L. A.; Ketelaar, T. (2010). «Misperception of sexual and romantic interests in opposite-sex friendships: Four hypotheses». Personal Relationships. 14 (3): 411–429. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00163.x.

- ^ Shotland, R. L.; Craig, J. M. (1988). «Can men and women differentiate friendly and sexually interested behaviour?». Social Psychology Quarterly. 51 (1): 66–73. doi:10.2307/2786985. JSTOR 2786985.

- ^ Gonick, Larry; Smith, Woollcott (1 Jan 1993). The Cartoon Guide to Statistics. ISBN 0062731025.

Further reading[edit]

- Darwin, Charles (1871). The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex (2nd ed.). John Murray. ISBN 978-0-8014-2085-6.

- McKay, R.; Efferson, C. (2010). «The subtleties of error management» (PDF). Evolution & Human Behavior. 31 (5): 309–319. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.04.005. Archived from the original on 2016-06-11.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Johnson, D. D. P.; Blumstein, D. T.; Fowler, J. H.; Haselton, M. G. (2013). «The evolution of error: error management, cognitive constraints, and adaptive decision-making biases». Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 28 (8): 474–481. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2013.05.014. PMID 23787087.

Introduction, Theory, and Hypotheses Development

Errors occur every day, and in every organization. For individuals and organizations alike, it is thus of interest to learn how to deal with errors in order to be successful. Error management can be described as a perspective that pledges for a “useful approach to errors with the goal of reducing future errors, of avoiding negative error consequences and of dealing quickly with error consequences once they occur” (Frese, 1995, p. 113). We consider errors as unintentional deviations from a goal, rule, or standard (Reason et al., 1990; Frese and Zapf, 1994; Hofmann and Frese, 2011; Frese and Keith, 2015). It has to be noted that the error itself may be disentangled from its consequences. Negative error consequences may ultimately include failure (Frese and Keith, 2015). In an organizational context, failure refers to the “termination of an initiative to create organizational value that has fallen short of its goals” (Shepherd et al., 2011, p. 1229). Further, errors can be distinguished from setbacks. In a work environment, setbacks can be described as “task-related disruptions and inhibitions” (Chong et al., 2020, p. 1409). In that sense, a setback shares a similarity with an inefficiency: Given an inefficiency, the goal is ultimately reached. However, the path to reach the goal is not optimal, as it requires more time and/or resources. On the contrary, setbacks require action from the employees: When confronted with setbacks, employees have to “appraise unforeseen problems, unlearn their existing automatic task scripts promptly, develop novel solutions, learn new ways of operations, and adapt to updated rules and advisories” (Chong et al., 2020, p. 1410).

Error management acknowledges that despite best efforts to prevent errors, it is impossible to avoid errors completely (Reason, 1997). This suggests that dealing with errors after they have occurred is necessary. Error management elaborates on the aforementioned idea that errors can be distinguished from their consequences. Thus, errors do not inevitably lead to negative consequences; it is possible to avoid or reduce negative consequences, and even positive consequences can occur. Such positive consequences may be learning from errors (e.g., Sitkin, 1992). What is more, more learning occurs from failure than from success (Shepherd et al., 2011). Studies on error management have mostly focused on effectiveness of error management training for individuals, for example when principles of error management were incorporated in software training (e.g., Keith and Frese, 2008), or on processes and effects of error management on the individual level (e.g., Frese et al., 1991; Dormann and Frese, 1994; Chillarege et al., 2003; Heimbeck et al., 2003; Keith and Frese, 2005; Keith, 2011; for a meta-analysis, see Keith and Frese, 2008).

On a team and organizational level, team and organizational members may share a view on errors (e.g., they may consider errors as learning opportunities) and may have common practices in regard to errors (e.g., to openly discuss an error with colleagues). The norms and practices constitute an organizational culture (House et al., 2004). Organizational culture consists of the following components: First, norms are behavioral prescriptions that organizational members agree on. Second, these organizational norms are internalized by organizational members. Third, the normative ideas are reinforced by organizational members independent of supervisors or outside interventions. Fourth, through practice, the norms produce ‘normative pressure’ to conform (House et al., 2004).

Error management culture1 (van Dyck et al., 2005) denotes one form of organizational culture with regard to errors. Given an error management culture, team members expect errors to happen – therefore, they are more vigilant and are better in anticipating errors. This allows them to detect errors faster. As a rule of thumb, the faster errors are detected, the better the chances to minimize negative error consequences (Keith and Frese, 2011). In field studies, error management culture has been shown to benefit organizational outcomes such as profitability, innovativeness, and safety (e.g., van Dyck et al., 2005; Hofmann and Mark, 2006; Keith and Frese, 2011; Fischer et al., 2018). While field studies have the advantage of high ecological validity, the higher ecological validity comes at the expense of lower internal validity, as external influences can hardly be excluded. This may be problematic, as many factors may play an important role and influence organizational performance, for example the leadership of the company, the industry in which the company operates, as well as other cultural factors that go above and beyond the error management culture. In different terms: While the results of these studies are quite impressive, the question remains whether the effect of error management culture on performance unfolds directly, or whether other variables may explain or modify this effect.

Most of the (field) studies on error management culture studied the effects of error management culture on the aggregated, organizational level instead of the more fine-grained team level (e.g., van Dyck et al., 2005; Fischer et al., 2018). Another shortcoming of these field studies is that the question of how an error management culture can be induced remained unanswered.

Inducing culture is not a trivial issue. There are several components that can go wrong if one wants to develop a (organizational) culture in a team: First, people may not agree on a norm. Therefore, the concept of ‘culture (or climate) strength’ has become important in the organizational culture literature (Schneider et al., 2002). If only a few unit members take the norm for granted, we cannot consider it culture or climate. In fact, one key element of culture is that it is shared and accepted by most (if not all) members of the unit (team, organization, society; e.g., House et al., 2004). Low culture strength of error management culture would thus mean a disagreement on how to consider errors and deal with occurring errors. Even if the mean value of perceived error management culture may be high, a disagreement would mean that not all team members in fact feel they may openly admit errors, or voice ideas without having to fear punishment for errors. For error management culture to truly unfold, both the mean level and culture strength have to be high. (If the mean level was low and culture strength high, this would indicate a culture where errors are considered negatively and have to be prevented.) Second, there may be superficial adjustments to instructions by supervisors (or, in an experimental setting, to the experimental instructions); thus, a certain internalization of the norms needs to take place (Gal’perin, 1967). Superficial adjustments to instructions may look very similar to norms, but should not be confused with culture, because people may merely repeat instructions (e.g., in a manipulation check) and this conformity may just reflect the willingness to participate in a study or the willingness to superficially conform to the supervisor. Third, culture needs to change behavior in the organizational unit: The first and certainly important change in behavior is related to communication behavior in the organizational unit (we further develop this issue in the following paragraph). However, communication behavior is just one prerequisite of organizational culture. Fourth, the willingness to conform to a certain cultural norm may be influenced by (a) the time that one spends practicing the norms in an organizational unit, (b) the adequacy of the organizational norm to the tasks that need to be done, and (c) the convincingness and obvious importance of the organizational norm. These issues have the following implications: First, we need to experiment with various instructions and methods of presenting the norms. Second, we also need to experiment with various tasks to find out which ones can be used for certain normative systems. And third, experimental approaches have inherent weaknesses because the time spent practicing the norms is usually highly limited.

Particularly in newly formed teams, communication may be influenced by error management culture, which may ultimately increase performance. We believe that this relationship is particularly important for tasks that require creative problem solving for the following reasons: First, a high error management culture may create an environment where people do not fear blame or punishment for erroneous ideas. Due to the lack of fear of reprisal, team members may dare to articulate ideas they would have kept to themselves in an environment where errors are punished. Furthermore, an error management culture can also be beneficial for resolving misunderstandings, as team members of teams high in error management culture may be more likely to actively ask questions and reassure themselves. A high error management culture fosters an atmosphere where communication about errors, exploration and experimentation, and thus the introduction of new ideas, processes or procedures are encouraged (Keith and Frese, 2011). In such a high error management culture, more communication – both formal and informal – should take place. In teams with a high error management culture, team members are more willing to approach others and ask for help when they cannot correct an error by themselves. Open communication can foster quick error detection and error handling (van Dyck et al., 2005). Moreover, error communication represents the most important practice of error management culture (van Dyck et al., 2005). Error communication denotes the tendency to openly discuss errors with others, without the fear of being punished. It can be assumed that sharing potentially harmful information – i.e., that one has made an error – will be reciprocated by the fellow team members. The reciprocation serves two purposes: for one, it reinforces the error management culture, where errors can be shared openly. For another, when error communication is well received by team members, the reciprocation reinforces future error communication. An open discussion of errors may thus foster communication in general.

Second, communication can foster performance: When more ideas are expressed, the final solution may be improved: “effective group processes, particularly those related to communication, increase information and so are essential for high-performing development processes” (Brown and Eisenhardt, 1995, p. 368). Particularly for complex tasks, exchanging ideas and collectively verifying applicability to the problem, the integration of different viewpoints may foster an augmented and common comprehension of the task at hand. This common understanding, combined with the joint pooling of ideas, may enhance performance. For the context of aviation, Foushee (1984) argues that “the process of interaction is related to group performance” (p. 273). Interaction may be particularly important for group performance when tasks require a deeper understanding of the matter, and where the solution is not pre-defined as one clear statement. Such tasks require at least some amount of creativity (West, 2000).

Research on virtual teams supports the importance of communication on team success (e.g., Piccoli et al., 2004; Cramton and Webber, 2005; Horwitz et al., 2006; Marlow et al., 2017; Eisenberg et al., 2019). Moreover, virtual teams exchange information less effectively than traditional teams (Hightower et al., 1998). As traditional team members spend a lot of time in the office together, they have many opportunities for informal communication, for example when taking lunchbreaks together, and maybe even when they meet privately after work. For project teams, the situation may be quite different: many project teams are comprised only for the duration of one specific project. When team members expect no further cooperation and interaction after the completion of the project, motivation and possibilities for informal interaction may be lower than in “regular” work teams. This may be problematic, as “what appear to be merely ‘casual conversations around the water cooler’ often serve to informally exchange the kinds of information and experience that are critical to project coordination. …. [These informal communication channels] help to fill in the details of work, handle exceptions, correct mistakes and bad predictions, and over time mange the ripple effects of previous decisions and actions” (Herbsleb and Grinter, 1999, p. 86). Furthermore, “since designs never exhibit perfect modularity and are never error-free, process execution is rarely flawless, and the world is never completely predictable, informal communication will be essential to maintain project coordination” (Herbsleb and Grinter, 1999, p. 94).

The aim of the present studies is thus (a) to explore how error management culture can be induced, (b) to investigate whether we can replicate the beneficial effect of error management culture on performance found in field studies under standardized conditions, as well as (c) to gain insights into potential variables modifying or explaining this relationship. To address these issues, we conducted two studies with newly formed teams, in which we aim to explore the following research question and hypotheses:

Research Question 1: How can error management culture be induced? (Studies 1 and 2).

Hypothesis 1: Error management culture positively predicts performance. (Studies 1 and 2).

Hypothesis 2: Culture strength moderates the relationship between error management culture and performance. (Studies 1 and 2).

Hypothesis 3: Communication mediates the effect between error management culture and performance. (Study 2).

In both studies, we follow an experimental approach and shift the focus from the organizational to the team level. By grouping strangers into teams – newly forming teams of people who have not known each other before – we have the opportunity to attempt to experimentally induce an error management culture.

We use an abductive approach (e.g., Bamberger, 2019) for our experiments in this field. We do not suggest that we will manage to achieve all aspects of the complex concept of organizational culture within two experiments. Rather, we think that we should get closer to an idea of how to develop an organizational culture of a team.

In Study 1, which we conducted in a laboratory setting, we employed two rational problem solving tasks, for which the degree of correctness varies gradually and can be objectively quantified. Employing two tasks enabled us to explore the duration of potential effects of our manipulation. In Study 2, which we conducted online, we employed one task that requires creative problem solving. We adapted our manipulations from Study 1 to fit the different task and context, and we additionally created a second, “slimmed,” manipulation for error management culture. The design of Study 2 (see below) further allowed us to analyze the amount of communication between the team members. Both rational and creative problem solving are important to attain organizational performance, and are adequate variables to study team behavior in an experimental, yet realistic context (in fact, participants in Study 2 believed to be working on an actual task for an actual company).

The crucial test whether culture has actually unfolded (as opposed to a mere compliance with instructions) examines the culture strength. According to the literature, culture strength should moderate the effects of error management culture on performance (Schneider et al., 2002).

It is highly relevant to study error management culture in an experimental setting, thereby allowing standardization and exclusion of other variables rather than statistically controlling for them. On the team level, different processes may be related to error management culture than to error management on the individual level. Our research contributes to the existing literature in the following ways. First, from an empirical perspective, we attempt to experimentally induce error management culture and to investigate the beneficial effects of error management culture on performance. Second, from a theoretical perspective, by studying how an error management culture can be induced, we aim to shed light on questions regarding the drivers of change and innovation effects. Third, we are among the first ones to explicitly take culture strength into consideration when studying effects of error management culture. Fourth, as field studies have repeatedly demonstrated beneficial effects of error management culture on performance, from a practitioner perspective, the question of how to induce an error management culture is highly relevant.

In the following, we describe the studies we conducted in detail, discuss potential explanations for our results, and provide an outlook for future studies.

Study 1: Error Management Culture and Performance in Terms of Rational Problem Solving

Method

Sample

Participants were 136 students (N = 44 triads and 2 dyads) of a mid-sized German university. Mean age was 22.14 years (SD = 3.20) and 69.1% were female. Most of the participants (67.7%) worked at least part-time. Participants received either EUR 8 (approximately USD 9.50) or partial course credit as compensation.

Experimental Design and Procedure

We invited participants into the laboratory in sessions of three persons each to work on two team tasks, namely, the “NASA Moon Survival Problem” task (Hall and Watson, 1970) and its variation “Survival at Sea.” In both tasks, participants had to rank 15 items of equipment in terms of their importance for survival. The tasks (and similar variations of it) are commonly used to study team decision making processes (e.g., Wanous and Youtz, 1986). For both tasks, expert solutions represent the optimal ranking of the items.

We asked participants to individually complete questionnaires regarding demographics and their attitudes about errors. Then, we grouped individual participants from the same session into teams of three and randomly assigned teams to one of two experimental conditions (between-participants design with one factor: error framing condition): (1) Error management or (2) Error prevention. In the Error management condition, participants were encouraged to make errors while working on the team task and to learn from them. In the Error prevention condition, participants were instructed to avoid errors while working on the team task. We asked participants to write down the most important points of the manipulations, formulated as action principles (Glaub et al., 2014) on a flipchart. Furthermore, we aimed at fostering internalization (e.g., Gal’perin, 1967) of the manipulations by repeating them several times throughout the experiment. After receiving the manipulations and the instructions for the first task (i.e., the NASA Moon Survival Problem), participants were asked to discuss what they had read about errors. Participants then had 20 min to work on the first task. After 20 min, participants were provided with the expert solution for the first task, and asked to calculate the difference of their solution to the expert solution. Participants were informed that these differences were considered as errors. Subsequently, participants individually had to complete questionnaires regarding how they perceived the work environment in the team. After completion of the questionnaires for the first task (see “Measures” section for details), participants received the second task (i.e., Survival at Sea). Again, participants were asked to commonly find a solution, then were provided with the expert solution, and lastly asked to complete questionnaires on the work environment in the team (see “Measures” section for details). Finally, participants were thanked, debriefed and compensated.

Measures

Perceived Error Management Culture

We assessed perceived error management culture after each task with the 17-item Error Management Culture Questionnaire (van Dyck et al., 2005; α = 0.90 after Task 1 and α = 0.91 after Task 2), with slight modifications of item wordings to fit the team context. For example, the original item “After making a mistake, people try to analyze what caused it” was changed to “After making a mistake, people in this team tried to analyze what had caused it.” The Error Management Culture Questionnaire (van Dyck et al., 2005) is commonly used as a measure in organizations (Frese and Keith, 2015). It entails aspects of error competence, learning from errors, analyzing errors, and error communication. Participants responded on a five-point Likert scale. Individual responses were aggregated at the team level. To justify aggregation, we computed within-team agreement for each team using rwg(j) (James et al., 1984, 1993), and reliability of responses among team members with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC; Bliese, 2000). The mean values of rwg(j) = 0.84, ICC(1) = 0.28 and ICC(2) = 0.53 [F(45,90) = 2.13, p < 0.01] for Task 1 and rwg(j) = 0.89, ICC(1) = 0.24 and ICC(2) = 0.48 [F(45,88) = 1.94, p < 0.01] for Task 2 suggested appropriate levels of within-team agreement and reliability (Le Breton and Senter, 2008).

In order to avoid potential confusions with our experimental intervention and independent variable error management framing, we will refer to our measure of error management culture as perceived error management culture.

Team Performance

As a measure of team performance, for each task, we calculated the difference between the team’s solution and the expert solutions (ranging from 0 to 112). We inverted the variable, so that higher values indicate smaller deviations from the expert solution, and thus better performance. In the following, we will refer to this as closeness to the expert solution.

Moderator Variable: Culture Strength

As a measure for culture strength (Schneider et al., 2002), we used rwg(j)-values of each team.

Control Variables

Task Familiarity. As task familiarity could influence performance in the task, we assessed task familiarity as a potential control variable. We asked participants whether they were familiar with the tasks, or had worked on the tasks before. A sample item is “Were you familiar with the ‘NASA Moon Survival Problem’ and the ‘Survival at Sea’ task?” Cronbach’s alpha was 0.79.

Familiarity With Team Members. As we recruited participants for Study 1 on campus, we considered the possibility that some participants may know one or both other team members. As we aimed to study how error management culture unfolds, and assumed that therefore, it was important to newly form teams, we decided to include familiarity with team members as control variable. We assessed if participants were familiar with their team members by asking “How well do you know the two other members of your group?” (from 1 = not at all to 5 = very well).

Results

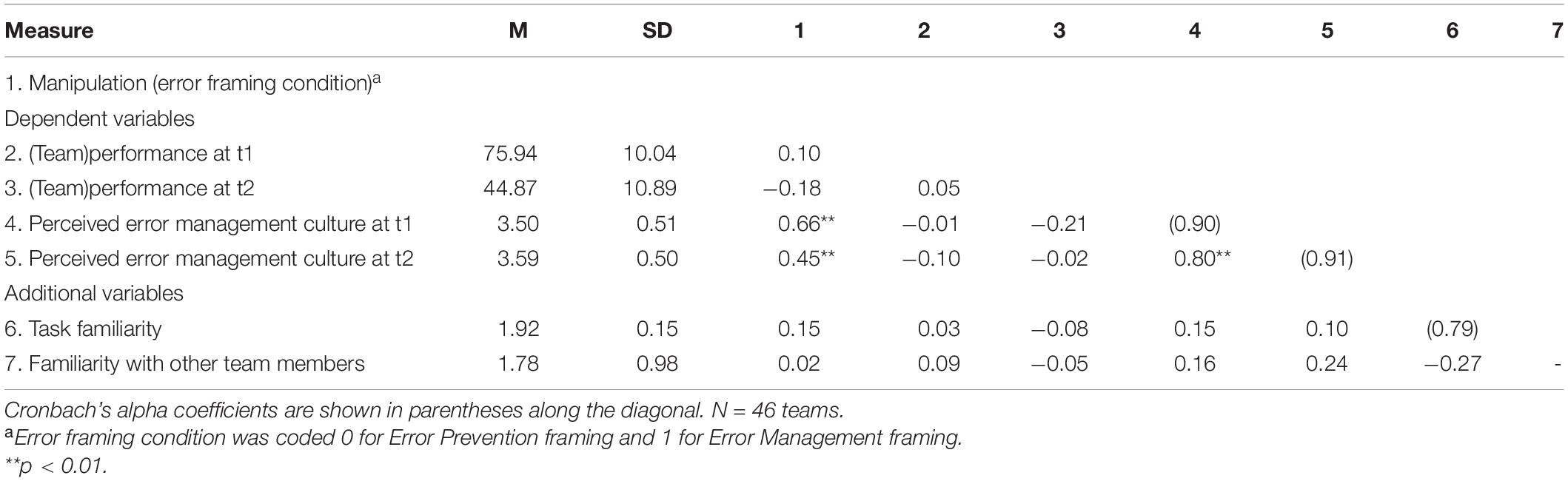

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of Study 1 variables are provided in Tables 1, 2.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of Study 1 variables.

Table 2. Means and standard deviations of dependent and process variables in Study 1 by between-participants factor levels.

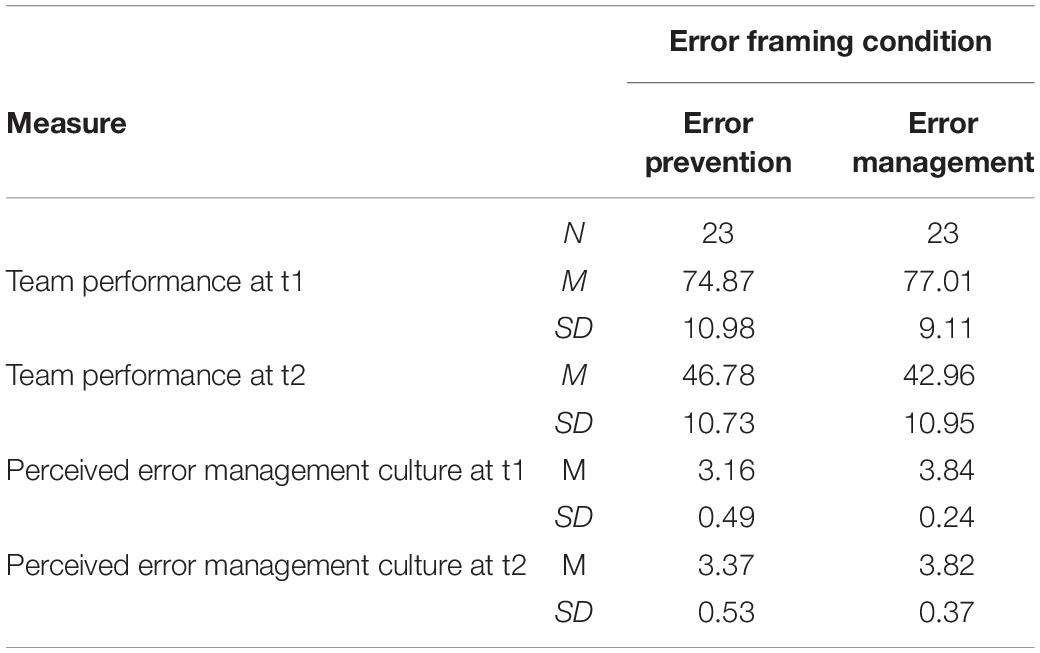

To test whether we succeeded in inducing error management culture (Research Question 1) and if we can find the error management culture and performance link in teams (Hypothesis 1) for a rational problem solving task, we conducted mediation analyses (Preacher and Hayes, 2004), with error framing condition (i.e., Error Management or Error Prevention framing) as predictor variable, perceived error management culture as mediator, and performance (i.e., closeness to the expert solution) as criterion variable. We used 5,000 bootstrap samples and estimated 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (CIs). We included our control variables task familiarity and familiarity with team members in our analyses as covariates.

For the first task, we found that the error management culture manipulation led to a higher level of perceived error management culture for Task 1 than the error prevention culture manipulation, β = 1.28, p < 0.001. We did not find a relationship between perceived error management culture for Task 1 and performance, β = −0.18, p = 0.40. We did not find support for the indirect effect of error framing condition on team performance through perceived error management culture for Task 1, β = −0.23, CI [−0.83, 0.27] (see Table 3).

Table 3. Mediation analysis in Study 1.

For the second task, we found that the error management culture manipulation led to a higher level of perceived error management culture for Task 2 than the error prevention culture manipulation, β = 0.84, p < 0.001. We did not find a relationship between perceived error management culture for Task 2 and performance, β = 0.11, p = 0.55. We did not find support for the indirect effect of error framing condition on team performance through perceived error management culture for Task 2, β = 0.09, CI [−0.23, 0.48] (see Table 3).

While we succeeded in inducing error management culture in terms of an effect of our manipulation on perceived error management culture, we were not able to find a direct effect of error management culture on performance. This is contradictory to our expectations based on findings in field studies (e.g., van Dyck et al., 2005; Fischer et al., 2018). One possibility why we did not find the expected effect is that maybe we did not succeed in actually manipulating error management culture after all. It is possible that the effects we found on perceived error management culture are rather an indicator of superficial compliance with the instructions than an actual change in culture.

In order to test this hypothesis (Hypothesis 2), we decided to take a closer look at culture strength (i.e., the agreement about the groups’ culture between team members; Schneider et al., 2002) regarding error management culture. In order to explore whether error management culture predicted performance in teams with a high culture strength, we tested whether culture strength moderates the relationship between perceived error management culture and performance (Hypothesis 2).

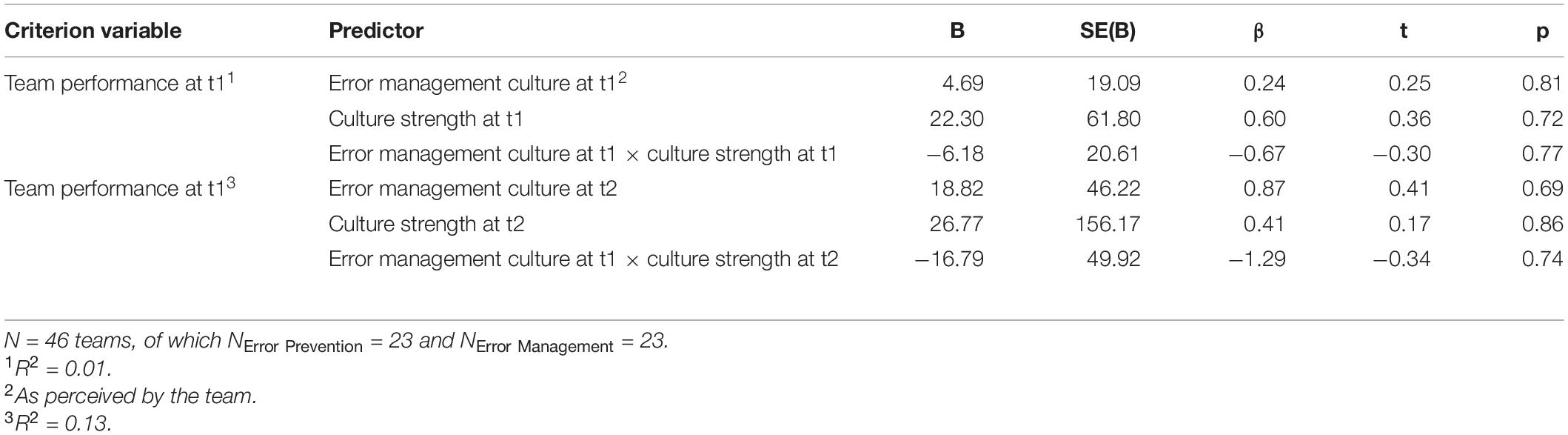

For Task 1, we conducted a moderation analysis using multiple linear regression, with perceived error management culture in Task 1 as predictor, culture strength in terms of rwg(j) as moderator, and performance in Task 1 as criterion variable. We did not find a significant main effect of perceived error management culture (β = 0.24, p = 0.81), nor of culture strength (β = 0.60, p = 0.72). Further, we did not find a significant interaction effect of perceived error management culture and culture strength (β = −0.67, p = 0.77) (R2 = 0.01; F = 0.16, p = 0.92).

Similarly, for Task 2, we conducted a moderation analysis using multiple linear regression, with perceived error management culture in Task 2 as predictor, culture strength in terms of rwg(j) as moderator, and performance in Task 2 as criterion variable. We did not find a significant main effect of perceived error management culture (β = 0.87, p = 0.69), nor of culture strength (β = 0.41, p = 0.87). Further, we did not find a significant interaction effect of perceived error management culture and culture strength (β = −1.28, p = 0.74) (R2 = 0.13; F = 2.01, p = 0.13). Thus, Hypothesis 2 is rejected (see Table 4).

Table 4. Moderation analysis for culture strength in Study 1.

Discussion

In Study 1, we were successful in manipulating error management culture in terms of an effect of our manipulation on perceived error management culture (Research Question 1). However, we could not find a beneficial effect of error management culture on performance in terms of rational problem solving (Hypothesis 1). Our additional analysis did not provide evidence for our speculation of a moderating effect of culture strength on the effect of perceived error management culture on performance. In concrete terms, we did not find evidence that perceived error management culture was beneficial for performance in teams with high culture strength, but not for teams with low culture strength.

We assumed that one of the reasons we did not find an effect of error management culture may lie in the type of tasks we had used – tasks that required rational problem solving. In order to effectively work on tasks that require rational problem solving, more analytic, convergent thinking may be required. Teams, particularly newly formed teams, that work on tasks that require rational problem solving may discuss in a focused, goal-oriented way (Guilford, 1957), and try to avoid errors whenever possible. On the contrary, in tasks that require creative problem solving, such as brainstorming, divergent thinking may be an effective strategy. For effectively conducting brainstorming tasks, it is particularly important that team members voice their ideas, without any limitations or barriers as to whether the idea may be implemented. Open communication is a vital part of error management culture. Therefore, we assumed that error management culture may be particularly beneficial for tasks that require creative problem solving, such as brainstorming. We aimed to address these possibilities in Study 2. As in Study 1, the pattern of results was the same for both tasks, for Study 2, we decided to employ only one task.

Study 2: Error Management Culture and Performance in Terms of Creative Problem Solving

We conducted Study 2 as an online experiment with newly formed teams. In Study 2, participants’ task was to create a marketing plan for a certain product (Hubner et al., 2020). While there are some factors that need to be considered when creating a marketing plan (such as who is the target group, how to advertise for the product, where to advertise, etc.), it is a task that requires a considerable amount of creativity. Similar to a brainstorming task, at first, one may collect ideas, and only in a second phase, the ideas are evaluated and selected, before agreeing on a common marketing plan.

We formed teams by grouping individual participants who had not known each other, and we attempted to manipulate error management culture. We had planned to comprise teams of three participants. However, as we had observed that some participants dropped out before the other two team members had shown up, we also used data of dyads, but included team size as control variable.

In Study 2, we employed the same manipulations as in Study 1 (after adapting them to fit the task and context). We additionally created a “slimmed” manipulation for error management culture. The main difference of both error management culture manipulations was that in the “slimmed” version, we did not ask participants to develop, formulate and note action principles for error management. Thereby, we aimed to address the issue that in the online environment, we were not able to control whether participants actually complied with our manipulation and did, in fact, formulate action principles. Different effects for both manipulations may thus suggest that participants in the “regular” error management condition actually complied with the manipulation and formulated action principles, and that these action principles were an important aspect of the manipulation.

Method

Sample

Participants were working adults from the United States recruited online using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Previous research has shown that data gathered from such environments is of acceptable quality (e.g., Buhrmester et al., 2011). We carefully followed specific suggestions that shall help to further enhance this quality: We used attention check items (e.g., “I receive my paycheck from goblins”; Meade and Craig, 2012), a manipulation check that measures understanding of instructions (see below) as a prerequisite to further participate in the experiment, as well as fair compensation (e.g., Aguinis and Lawal, 2012; Cheung et al., 2017). Additionally, in order to statistically control for potentially lower commitment to the participation in the study, we assessed and controlled for goal commitment (see below). The criteria for inclusion of respondents in the survey were age (>18 years) and place of residence (United States). Fourteen participants did not meet our criteria for inclusion and were excluded from further analyses. The final sample consisted of 309 participants (Ntotal = 128 teams, of which ntriads = 53 and ndyads = 75). Mean age of participants was 35.81 years (SD = 11.53) and 43.9% were female2. Participants’ average work-experience was 13.00 years (SD = 10.08) and 32.5% reported to hold a leadership position. Participants received USD 4.50 for participation (which corresponds to an hourly wage of approximately USD 9 and was thus in line with the United States federal minimum wage).

Experimental Design and Procedure

Participants were invited to work on a team task, namely, to develop a marketing plan for a newly developed product (Hubner et al., 2020). The product was fictitious, but as Hubner et al. (2020) demonstrated, participants deem it as realistic and often work enthusiastically on this task. The instructions explained that a start-up is currently working on the marketing concept of its most promising product, but is not sure how to advertise for it. Therefore, the start-up asks the “wisdom of the crowd” for help. Participants were explained that their task is embedded in a research project and that they also have to complete a questionnaire after working on the team task.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of three experimental conditions (between-participants design, one factor error framing condition with three levels): (1) a “slimmed” Error Management framing condition that did not foster internalization, (2) an Error Management framing condition similar to that of Study 1, and (3) an Error Prevention framing condition similar to that of Study 1. Participants who were grouped together received the same manipulation. In order to keep the manipulation realistic and in line with what is common in online environments such as Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, the manipulation was part of the written instructions that participants received for task completion. Our manipulations focused on how participants should deal with errors in the process of the team discussion. In the slimmed Error Management framing manipulation, we encouraged participants to make errors and to learn from them. In the Error Management framing condition similar to that of Study 1, we additionally aimed to foster internalization of the manipulations (e.g., Gal’perin, 1967). For this purpose, we asked participants to write down two error principles on a sheet of paper so they should be able to see them the entire time when working on the team task: “errors are positive” and “talk about errors openly in the team, as you can learn from them.” These principles should serve as guidelines to follow while working on the team task. In the Error Prevention framing condition similar to that of Study 1, participants were instructed to avoid errors. We also asked them to follow two error principles: “avoid errors as they only bother you and slow you down” and “make the marketing plan as perfect as possible” right from the start. We also asked participants to write down the error principles on a sheet of paper so they should be able to see them the entire time when working on the team task.

After reading the instructions, participants were asked to respond to questions assessing the understanding of the instructions. Participants who had received the same manipulation (i.e., either “slimmed” Error Management, Error Management or Error Prevention framing) and answered the questions correctly then arrived on a page containing a built-in chatroom. After the team members arrived on the page with the chatroom, the chat-function was automatically enabled. Participants could start to chat and generate ideas for a marketing plan. The teams had a maximum of 20 min time to complete the task. The chat window was programmed to close automatically 30 min after the first participant had logged in. Three minutes prior to that, participants were informed about the remaining time. After the chatroom closed, participants had to submit the team’s common final ideas on the next page. Subsequently, participants individually had to fill out questionnaires regarding how they perceived the work environment in the team (see “Measures” section for details). Finally, participants were thanked, debriefed and provided with a code for payment on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk.

Measures

Understanding of Instructions

After reading the instructions and before the dependent variable was assessed, participants responded to questions that probed whether participants had understood what the task was about and what the instructions had stated about errors. We asked participants three questions (“What does our most promising product do?,” “What task do you have to accomplish in this project?,” and “What was written in the text about making errors while working in a team?”) and they had to choose the correct answer out of four possibilities. A false answer led to an exclusion from the study, as it indicated that participants had not read the instructions carefully.

Error Management Culture

As in Study 1, we assessed error management culture with the 17-item Error Management Culture Questionnaire (van Dyck et al., 2005; α = 0.94), with slight modifications of item wordings to fit the team context. Participants responded on a five-point Likert scale. Individual responses were aggregated at the team level. To assess whether aggregation is justified, we computed within-team agreement for each team using rwg(j) (James et al., 1984, 1993), and reliability of responses among team members with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC; Bliese, 2000). The mean values of rwg(j) = 0.83, ICC(1) = 0.15 and ICC(2) = 0.30 [F(127,177) = 1.43, p < 0.05] suggested low but still appropriate levels of within-team agreement and reliability (Le Breton and Senter, 2008), justifying aggregation.

Communication

We assumed that teams that communicated more with each other during the brainstorming task may produce more creative ideas. We thus observed the communication of the teams in terms of the number of words exchanged during the group discussion. We analyzed the chat protocols and counted the number of words that the participants exchanged while working on the task. As this is an objective measure, within-team consistency and agreement measures are not applicable.

Dependent Variables

We used two dependent variables as indicators of performance: the quality of the ideas for the marketing plan, and the quantity of the ideas the marketing plan consisted of. We operationalized quality of the ideas by assessing three characteristics of the marketing plans: originality, usefulness, and completeness (Dean et al., 2005). Dean et al. (2005) defined an idea as original when it “rare (…), ingenious, imaginative, or surprising” (p. 663). To assess usefulness, we oriented on Dean et al.’s (2005) definition of workability/feasibility: the idea has to be “easily implemented and does not violate known constraints” (Dean et al., 2005, p. 663). An idea can be considered as complete when it covers aspects such as “who, what, where, when, why, and how” (Dean et al., 2005, p. 663). Two independent raters who were blind to the conditions rated the marketing plans on originality, usefulness, and completeness (all ICCs > 0.70). Subsequently, originality, usefulness, and completeness (α = 0.87) were combined as a measure for the quality of the ideas for the marketing plan. We operationalized quantity of the ideas as the number of ideas submitted for the marketing plan. For this purpose, we counted the number of discrete ideas submitted by the teams.

Moderator Variable: Culture Strength

As in Study 1, we used rwg(j)-values of each team as a measure for culture strength (Schneider et al., 2002).

Control Variables

Team Size. We controlled for team size because the amount of communication in the group may be higher in teams of three members than in teams of two members.

Task Familiarity. We included task familiarity as control variable, because both the quality and the quantity of ideas for the marketing plan may depend on how familiar participants are with similar tasks. We assessed task familiarity with the following three questions: “How familiar are you with creativity tasks, such as the task you were working on?”; “How familiar are you with creativity methods, such as brainstorming?”; “How experienced are you with marketing (from work, university, etc.)?” Participants responded on a five-point Likert scale. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.82.

Goal Commitment. Particularly for studies that are conducted online, the extent to which participants take the task seriously may influence the results. We therefore included goal commitment as control variable. We assessed goal commitment with three items of Hollenbeck et al.’s (1989) nine-item Goal Commitment scale. One sample item is “I was strongly committed to pursuing our goal of submitting a marketing plan.” Participants responded on a five-point Likert scale. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.72.

Results

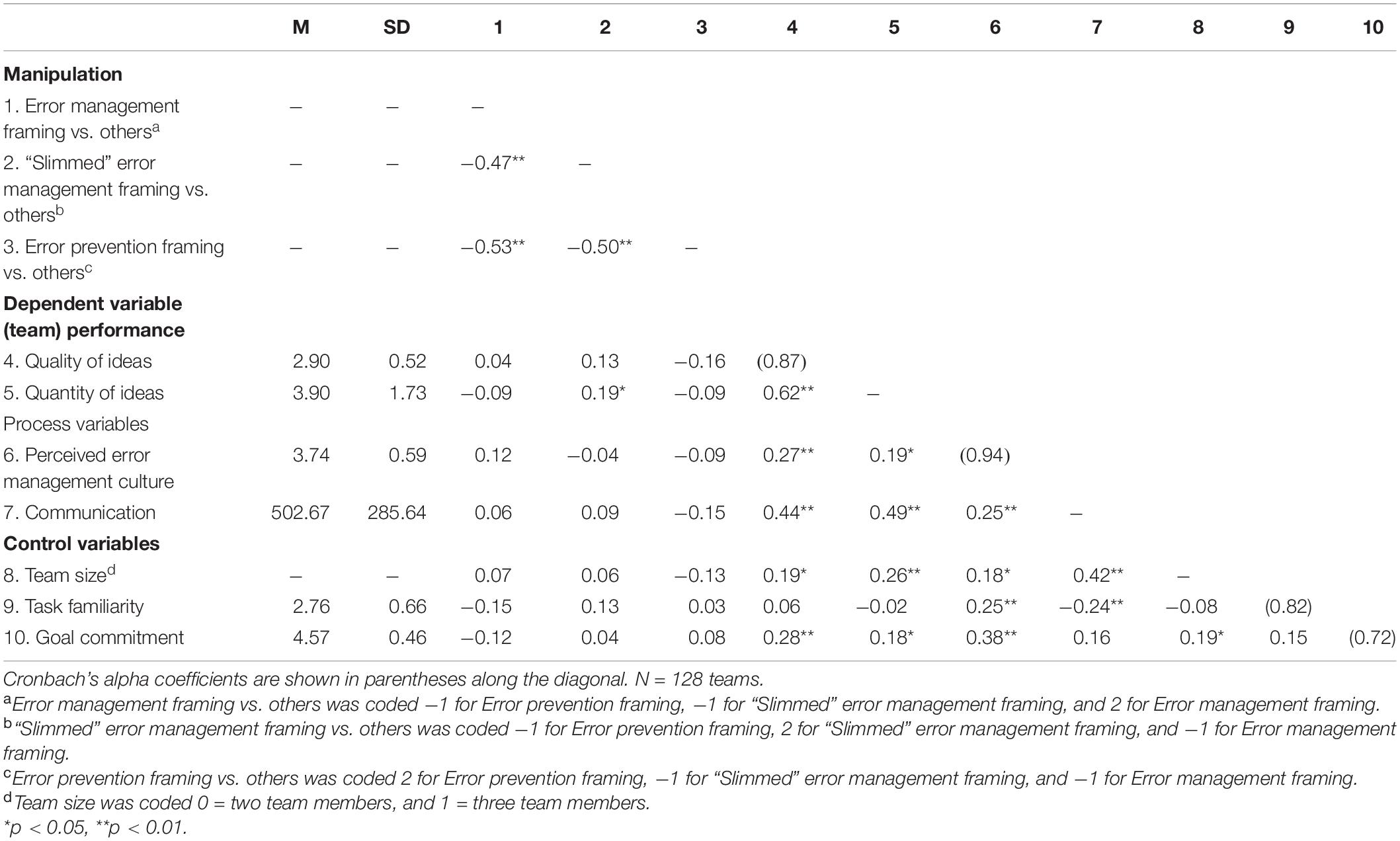

Means, standard deviations, and correlations of Study 2 variables are provided in Tables 5, 6.

Table 5. Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of Study 2 variables.

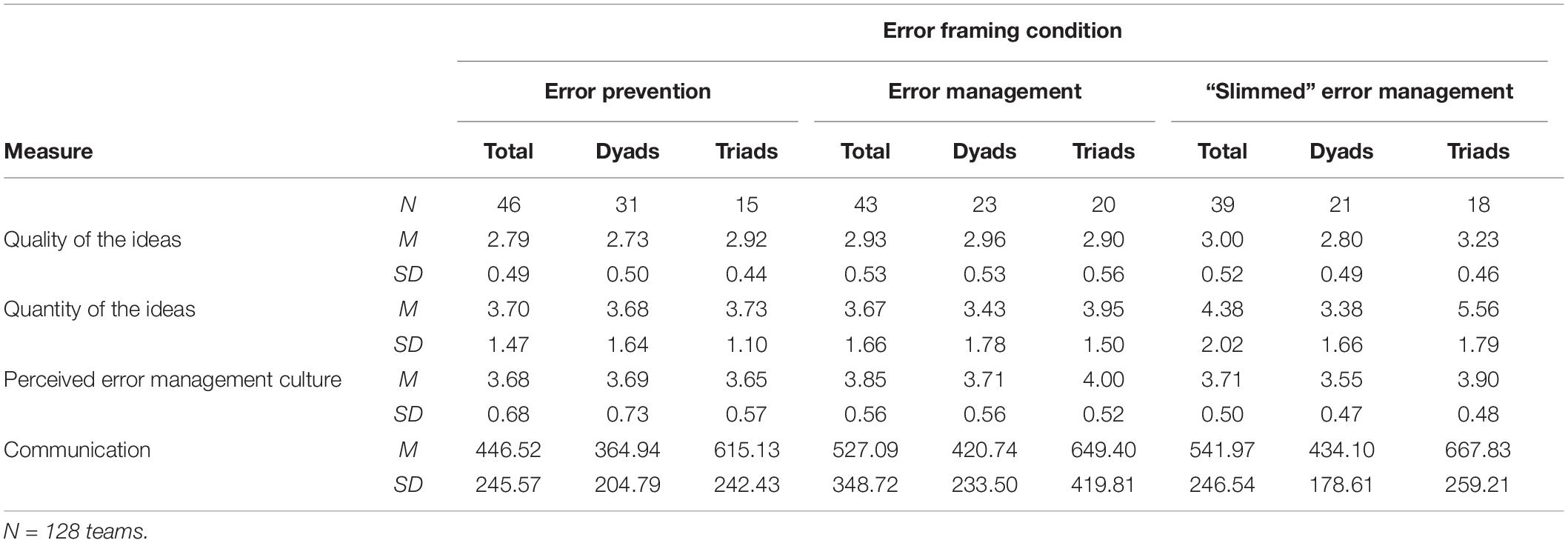

Table 6. Means and standard deviations of dependent and process variables in Study 2 by between-participants factor levels.

To test whether we succeeded in inducing error management culture (Research Question 1) and whether we could find an effect of perceived error management culture on performance (Hypothesis 1), we conducted mediation analyses (Preacher and Hayes, 2004; Hayes and Preacher, 2014) with error framing condition (i.e., Error Management vs. Error Prevention vs. “slimmed” Error Management framing) as predictor variable, perceived error management culture as mediator, and performance (in terms of quality and quantity) as criterion variables. As in Study 1, we used 5,000 bootstrap samples and estimated 95% bootstrap CIs, and we included team size, task familiarity, and goal commitment as covariates. For our multicategorical predictor variable (i.e., error framing condition), we created two dummy variables with indicator coding and the Error Prevention framing as reference category: D1 with codes of (0, 1, 0) for Error Prevention framing, Error Management framing, and “slimmed” Error Management framing, respectively, and D2 with codes of (0, 0, 1) for Error Prevention framing, Error Management framing, and “slimmed” Error Management framing, respectively.

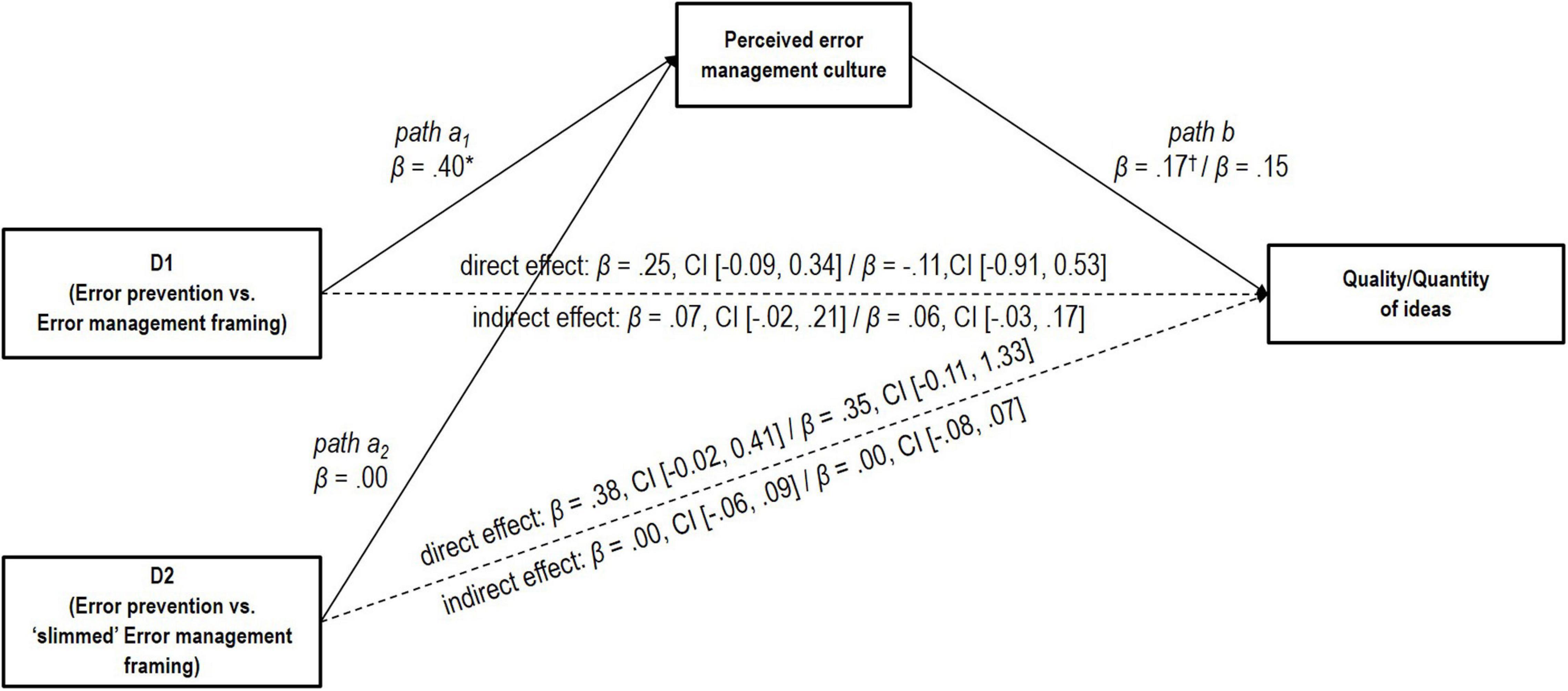

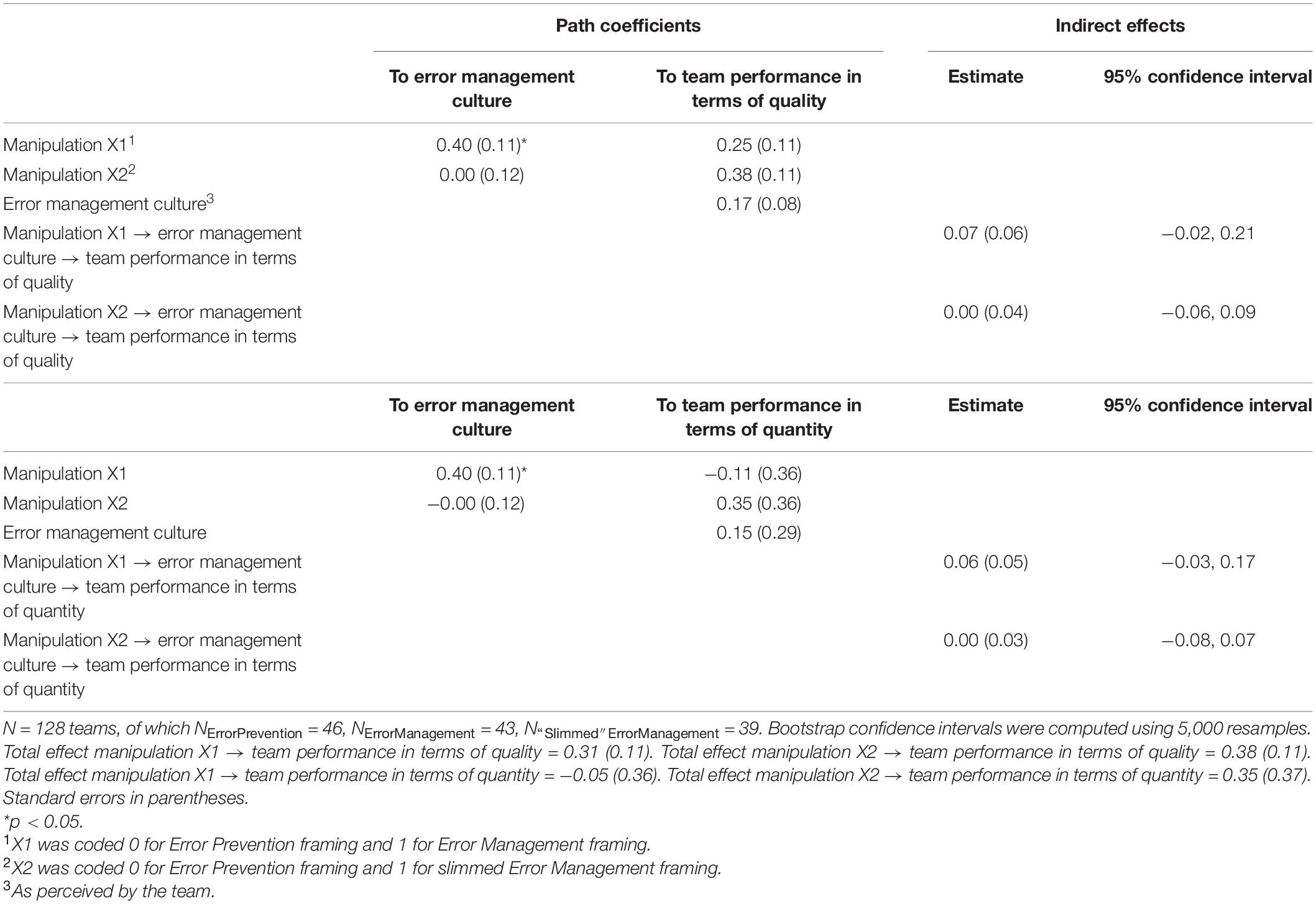

We found that the Error Management framing manipulation led to a higher level of perceived error management culture than the Error Prevention framing manipulation, D1: β = 0.40, p < 0.05 (see Figure 1 path a1). The “slimmed” Error Management framing manipulation did not lead to a higher level of perceived error management culture than the Error Prevention framing manipulation, D2: β = 0.00, p = 0.99 (see Figure 1 path a2). As in Study 1, we could not find the relationship between perceived error management culture and performance, β = 0.17, p = 0.08 for quality of the ideas (see Figure 1 path b), and β = 0.15, p = 0.13 for quantity of the ideas (see Figure 1 path b). We did not find support for the indirect effect of the experimental manipulation on performance (neither in terms of quality nor quantity of the ideas) through perceived error management culture, neither for our first dummy variable (D1) “Error Prevention framing vs. Error Management framing,” β = 0.07, CI [−0.02, 0.21] for quality of the ideas, and β = 0.06, CI [−0.03, 0.17] for quantity of the ideas (see Figure 1), nor for our second dummy variable (D2) “Error Prevention framing vs. “slimmed” Error Management framing” β = 0.00, CI [−0.06, 0.09] for quality of the ideas, and β = 0.00, CI [−0.08, 0.07] for quantity of the ideas (see Table 7 and Figure 1).

Figure 1. Original mediation model in Study 2. The non-significant indirect effect of dummy variable D1 for our manipulation [i.e., error prevention (coded 0) vs. error management framing (coded 1)] and the non-significant indirect effect of dummy variable D2 for our manipulation [i.e., error prevention (coded 0) vs. “slimmed” error management framing (coded 1)] on performance (quality or quantity of ideas) through perceived error management culture in Study 2. The dashed arrows indicate the direct paths between the dummy variables for our manipulation (D1 and D2) and performance. Standardized and partially standardized values and confidence intervals (CI). N = 128 teams, †p < 0.10, *p < 0.05.

Table 7. Mediation analysis in Study 2.

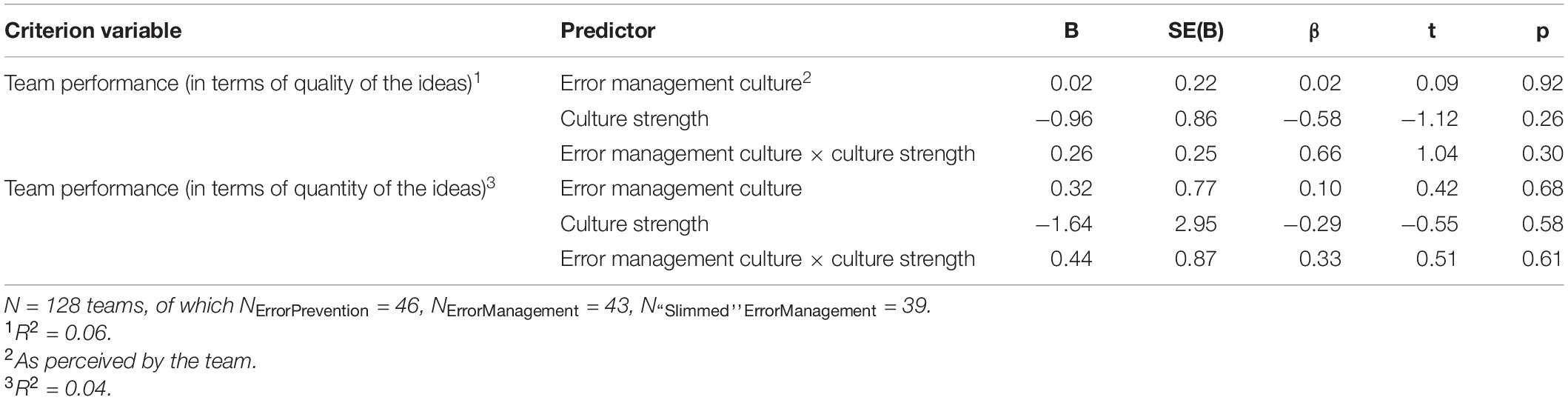

To test whether culture strength moderated the relationship of error management culture and performance (Hypothesis 2), we conducted a moderation analysis using multiple linear regression, with perceived error management culture as predictor, culture strength in terms of rwg(j) as moderator, and performance (both in terms of quality and quantity of the ideas) as criterion variable. For performance in terms of quality of the ideas, we did not find a significant main effect of perceived error management culture (β = 0.02, p = 0.92), nor of culture strength (β = −0.96, p = 0.26). Further, we did not find a significant interaction effect of perceived error management culture and culture strength (β = 0.26, p = 0.30) (R2 = 0.06; F = 2.74, p = 0.05). For performance in terms of quantity of the ideas, we did not find a significant main effect of perceived error management culture (β = 0.32, p = 0.68), nor of culture strength (β = −1.63, p = 0.58). Further, we did not find a significant interaction effect of perceived error management culture and culture strength (β = 0.44, p = 0.61) (R2 = 0.04; F = 1.88, p = 0.14) either. Thus, Hypothesis 2 is rejected (see Table 8).

Table 8. Moderation analysis for culture strength in Study 2.

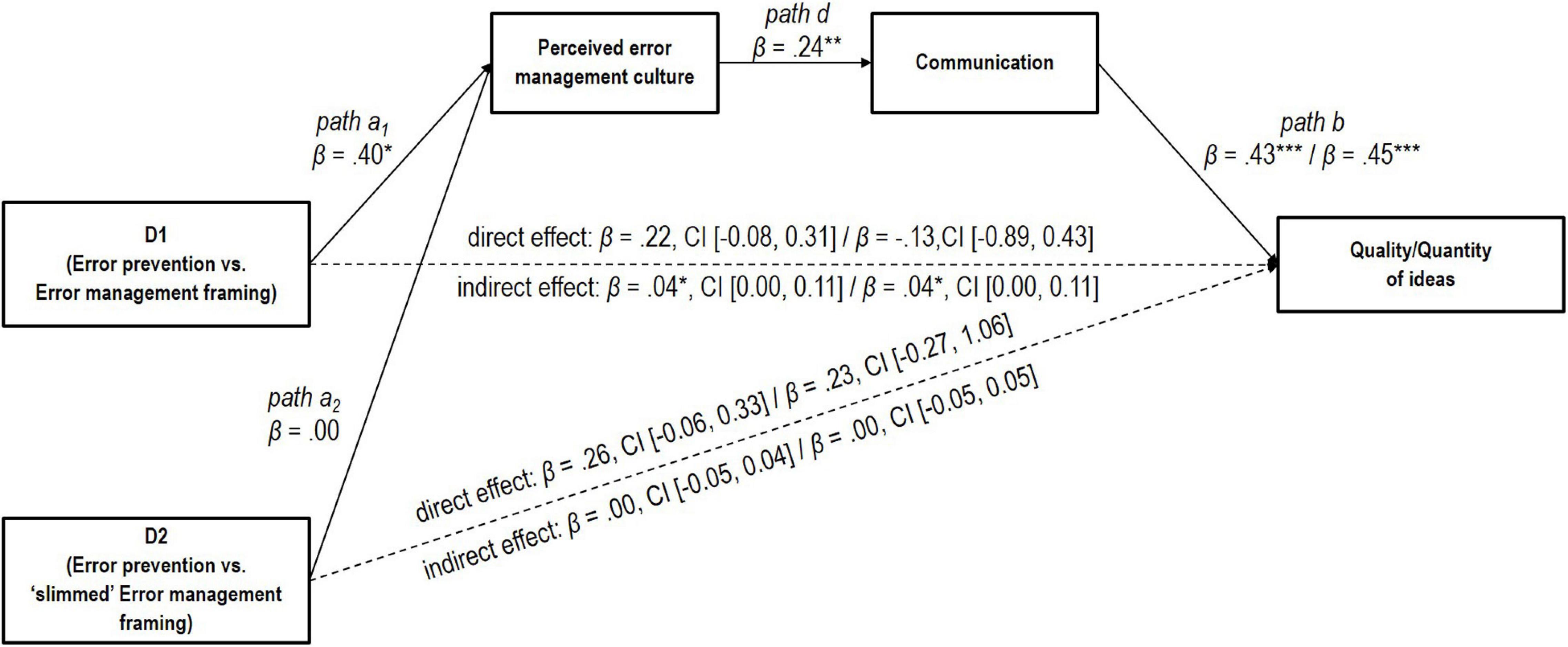

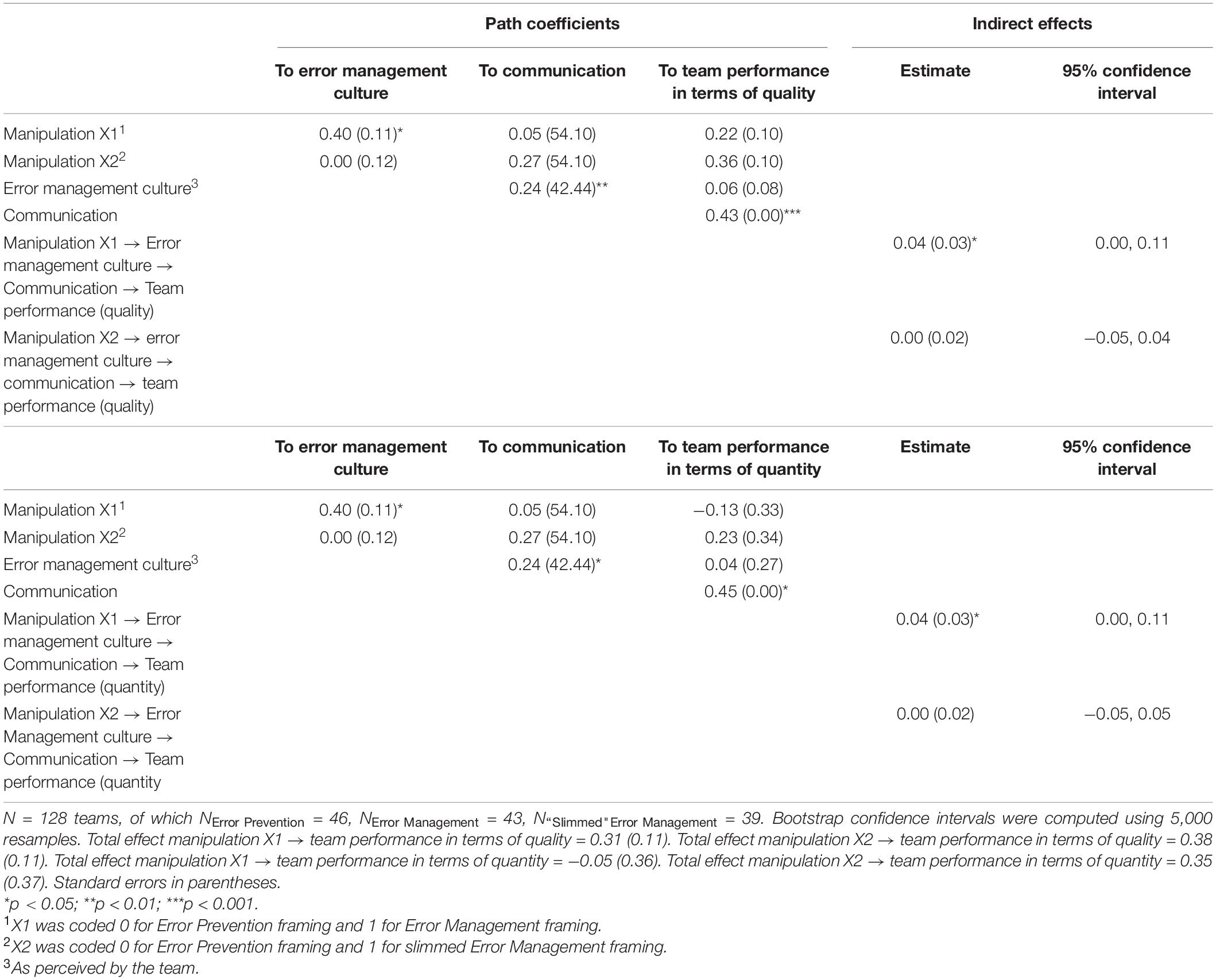

To test whether perceived error management culture affected performance indirectly through communication (Hypothesis 3), we conducted serial mediation analyses (Preacher and Hayes, 2004; Hayes and Preacher, 2014) with error framing condition as predictor, perceived error management culture and communication as mediators, and performance (in terms of quality of the ideas or quantity of the ideas) as criterion variables. We used 5,000 bootstrap samples and estimated 95% bootstrap CIs. We found that the Error Management framing manipulation led to a higher level of perceived error management culture than the Error Prevention framing manipulation, D1: β = 0.40, p < 0.05 (see Figure 2 path a1). The “slimmed” Error Management framing manipulation did not lead to a higher level of perceived error management culture than the Error Prevention framing manipulation, D2: β = 0.00, p = 0.99 (see Figure 2 path a2). Furthermore, perceived error management culture positively predicted communication, β = 0.24, p < 0.01 (see Figure 2 path d), and communication positively predicted performance both in terms of quality of the ideas, β = 0.43, p < 0.001 (see Figure 2 path b), and quantity of the ideas, β = 0.45, p < 0.001 (see Figure 2 path b). The 95% bias corrected confidence interval for the indirect effect excluded zero, indicating a significant indirect relationship for our first dummy variable (D1) “Error Prevention framing vs. Error Management framing” with performance (both in terms of quality of the ideas and quantity of the ideas), β = 0.04, CI [0.00, 0.11] for quality of the ideas, and β = 0.04, CI [0.00, 0.11] for quantity of the ideas (see Figure 2). In other words, the results are consistent with the idea that perceived error management culture and communication mediate the relationship between error framing condition and performance. For our second dummy variable (D2), “Error Prevention framing vs. ‘slimmed’ Error Management framing,” we did not find an indirect relationship with performance (in terms of quality of the ideas or quantity of the ideas), β = 0.00, CI [−0.05, 0.04] for quality of the ideas, and β = 0.00, CI [−0.05, 0.05] for quantity of the ideas (see Table 9 and Figure 2).

Figure 2. Alternative mediation model in Study 2. The significant indirect effect of dummy variable D1 for our manipulation [i.e., error prevention (coded 0) vs. error management framing (coded 1)] and the non-significant indirect effect of dummy variable D2 for our manipulation [i.e., error prevention (coded 0) vs. “slimmed” error management framing (coded 1)] on performance (quality or quantity of ideas) through perceived error management culture and communication in Study 2. The dashed arrows indicate the direct paths between the dummy variables for our manipulation (D1 and D2) and performance. Standardized and partially values and confidence intervals (CI). N = 128 teams, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Table 9. Serial mediation analysis with communication in Study 2.

Discussion

In sum, regarding Research Question 1, we succeeded in inducing error management culture in terms of an effect on perceived error management culture using the same type of manipulation as in Study 1, i.e., our manipulation containing action principles. Our “slimmed” manipulation (that did not ask participants to internalize action principles) was not successful.

In regard to Hypothesis 1, we were not able to find a direct, beneficial effect of error management culture on team performance. As in Study 1, culture strength did not moderate the relationship between error management culture and performance (Hypothesis 2). However, in regard to Hypothesis 3, we found an indirect, beneficial effect through communication in that our manipulation that included action principles fostered perceived error management culture, which increased communication, and communication fostered team performance.3

General Discussion

In the present paper, we investigated whether and how error management culture may be induced in newly formed teams, and if and how error management culture can be beneficial for performance, both in terms of rational and creative problem solving. We found that inducing error management culture is more difficult than expected. Our manipulation that included action principles that aimed to foster internalization was successful in terms of an effect on perceived error management culture. However, we did not find a direct effect of error management culture on performance, as it was previously found in field studies. This raises the question whether we actually succeeded in inducing error management culture, or whether our results rather reflect mere compliance with our instructions. In Study 2, where we included communication as a mediator, we found error management culture to be beneficial for performance indirectly via communication. In both samples, we further tested whether culture strength moderated the effect of error management culture on performance. We did not find the expected moderation effect. In the following, we will discuss our findings in greater detail, and suggest potential theoretical explanations.

Theoretical Contributions

Inducing an Error Management Culture

To the best of our knowledge, the present studies are among the first ones to investigate how an error management culture can be induced. In two studies, we used manipulations that included action principles (Glaub et al., 2014) in regard to dealing with errors – “error principles.” We had explicitly asked participants to write down these principles and follow them throughout working on the task(s). Additionally, we repeated our manipulations several times, and had a “reminder” of the principles visible at all times during the team discussion. By repetition of the main principles of our manipulations, we aimed to foster that participants internalize these principles (Gal’perin, 1967). As in Study 2, our manipulation that did not include these “error principles” was not successful, including such principles seems to be important when inducing error management culture.

It has to be noted that while we succeeded in terms of an effect of our manipulation on perceived error management culture, we did not find an effect (neither of our manipulation, nor of perceived error management culture) on performance. An explanation may either lie in the error management culture and performance relationship, or in the culture strength regarding error management culture. In the following, we discuss both possibilities in greater detail.

The Error Management Culture–Performance Relationship

Contrary to what we had expected based on the literature on error management culture in organizations (e.g., van Dyck et al., 2005; Fischer et al., 2018), we did not find a direct effect of error management culture on performance, neither in terms of rational, nor in terms of creative problem solving. One potential interpretation could be that error management culture is not beneficial for performance. This, however, would be contrary to findings in, for example, the aforementioned field studies. Additionally, experimental evidence on the individual level has repeatedly demonstrated a beneficial effect of error management training on performance (e.g., Keith and Frese, 2005). While we were able to successfully induce error management culture in terms of an effect on perceived error management culture in both studies, only in Study 2, where we included communication as mediating variable, we found that error management culture had an indirect effect on performance in terms of creative problem solving through increased communication among team members.

On the one hand, we were surprised that we did not find the direct effect of error management culture on performance that has been reported non-experimental field studies (e.g., van Dyck et al., 2005; Fischer et al., 2018). On the other hand, there is a major difference between the organizations studied in non-experimental field studies and the teams in our studies: In organizations, the organizational culture is most likely engrained and internalized by the members of the organization. The teams in our study were newly formed and comprised of strangers who had no prior interaction. Consequently, the teams did not have an already internalized culture, thus had to adopt a new culture. It is possible that in such situations where culture has to be newly formed and unfold, error management culture may take more time to fully unfold, or may not be strong enough to directly impact performance – communication may be the key driver.

Culture Strength

Our second potential explanation to why we did not find an effect of error management culture on performance lies in the culture strength, i.e., the agreement about the groups’ culture between team members (Schneider et al., 2002). We thus tested whether culture strength moderates the relationship between perceived error management culture and performance. We did not find culture strength to moderate the relationship of error management culture and performance. In other words, the relationship between perceived error management culture and performance did not depend on team members’ agreement about the group’s culture. This result reinforces our assumption that we did not actually succeed in inducing culture, and the effect of our manipulation on error management culture rather represents participants’ superficial compliance with our instructions. It has to be noted that when controlling for the (lack of) agreement, perceived error management culture was related to increased team performance.

Practical Contributions

An error management culture conveys a constructive view on errors as well as strategies for dealing with errors that have occurred. Negative error consequences, such as failure (Shepherd et al., 2011; Frese and Keith, 2015) shall be prevented, and positive consequences, such as learning from errors, shall be encouraged. Based on the previous findings that error management culture is beneficial for organizational performance, the question of how an error management culture can be induced is important for practitioners.

With our studies, we provide a starting point that outlines what interventions in change processes and mergers and acquisitions should consider and include. Our studies demonstrated that in order to induce error management culture, action principles in regard to errors shall be internalized, and thereby shape culture. These “error principles” may include rules how to deal with errors in the team or organization. For example, these “error principles” may explicitly encourage communicating an error that has occurred. By sharing the error with others – without having to fear blame or other negative consequences – other people may learn from the error. Furthermore, the error, once shared with others, may be used as a starting point to develop new, innovative ideas. Ultimately, this may enhance team or organizational performance.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research

One of the strengths of our studies is that we used different sources for all our variables. In both our studies, our independent variable was an aggregate measure of the respective team members. In Study 1, our dependent variables were objective measures. In Study 2, the dependent variables were assessed and counted by raters, and communication was objectively measured. Thereby, we were able to circumvent the common source bias, which is a problem in many studies.

Furthermore, replication is essential to reduce the likelihood of false-positive findings. In abductive research, (internal) replication is “a viable antidote to what Bliese and Wang (2020) term ‘origination bias,’ or in other words, ‘the practice of viewing findings from a single, original study as being almost sacred,’ even if these findings were exploratory in nature” (Bamberger, 2019, p. 104). In Study 2, we were able to replicate the findings regarding our manipulation containing action principles we obtained in Study 1. Moreover, we were able to extend our model by including communication as well as an indirect effect on performance.