Содержание

- Exceptions and Error Handling in Dart and Flutter

- Why Have Error & Exception Handling?

- Errors and Exceptions

- Errors

- Examples

- Exceptions

- Examples

- Handling Errors

- Further Reading

- Handling Exceptions

- Finally

- Example Code

- Catch Exception

- Example Code

- Example Code Output

- Catch Exception and Stack Trace

- Strack Trace

- Example Code

- Example Code Output

- Catch Specific Exceptions

- Example Code

- Example Code Output

- Throw Exception

- Example Code

- Rethrow Exception

- Example Code

- Output

- Create Custom Exceptions

- What’s the recommended way in Dart: asserts or throw Errors

- 4 Answers 4

- Background

- Example of throwing an Exception

- Example of throwing an Error

- Example of using asserts

- Summary

- Error vs exception dart

- class

- Dart – Types of Exceptions

- Built-in Exceptions in Dart:

Exceptions and Error Handling in Dart and Flutter

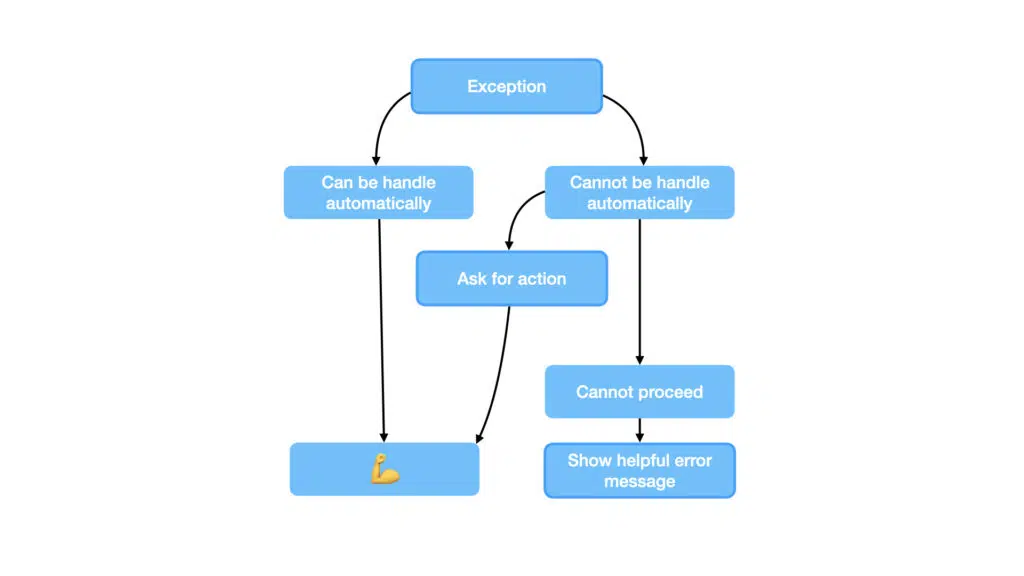

Why Have Error & Exception Handling?

Most software systems are complicated and written by a team of people.

Complexity arises from multiple sources:

- The business domain.

- The act of writing software.

- From multiple people working together, each one having different viewpoints.

- etc

The complexity can result in misunderstandings, errors & exceptions.

This is not the end of the world if the code has good error handling.

- If you don’t handle your errors & exceptions, your software may act unpredictably, and users may suffer a catastrophic error without knowing it or being able to detect when it happened.

- If you do handle your errors & exceptions, the user may able to continue using the program even with the error / exception and the developers can find the problems over time and improve the software.

Good error & exception handling should not blind the end user with technical jargon, but it should also provide enough information for the developers to trace down the problem.

Dart can throw Errors & Exceptions when problems occur running a Dart program. When an Error or an Exception occurs, normal flow of the program is disrupted, and the program terminates abnormally.

Errors and Exceptions

Errors

Errors are serious issues that cannot be caught and ‘dealt with’. Non-recoverable.

Examples

- RangeError – programmatic bug where user is attempting to use an invalid index to retrieve a List element.

- OutOfMemoryError

Exceptions

Exceptions are less-serious issues that can be caught and ‘dealt with’.

Examples

- FormatException – could not parse a String.

Handling Errors

Trying to handle non-recoverable errors is impossible. How can you catch and just handle an out of memory error?

The best thing to do is to log what happened and where so that the developers can deal with them. The approach to this is to add a handler to the top level of your application, for example Sentry or Catcher.

Further Reading

Handling Exceptions

Try to handle these to prevent the application from terminating abruptly. If you want your code to handle exceptions then you need to place it in a ‘try..catch..finally’ block. The finally part is optional.

Finally

Dart also provides a finally block that will always be executed no matter if any exception is thrown or not.

Example Code

Catch Exception

The first argument to the catch is the Exception.

Example Code

Example Code Output

Catch Exception and Stack Trace

The second argument to the catch is the StackTrace.

Strack Trace

A Stack Trace is a list of the method calls that the application was in the middle of when an Exception was thrown. The most useful information is normally shown at the top of StackTraces, so you should always look at them from the ‘top down’. Sometimes this takes a lot of scrolling up!

Example Code

This code catches the Exception and StackTrace.

Example Code Output

Catch Specific Exceptions

If you know you want to catch a specific Exception then you can use an ‘on’ instead of a ‘catch’. Consider leaving a ‘catch’ at the bottom to catch other Exceptions.

You can optionally add the ‘catch(e)’ or catch(e, s)’ after if you want the Exception and StackTrace data as arguments.

Example Code

Example Code Output

Throw Exception

To throw an Exception simply use the ‘throws’ keyword and instantiate the Exception.

Example Code

Rethrow Exception

Once you have caught an Exception, you have the option of rethrowing it so that it bubbles up to the next level. So, you could catch an Exception, log it then rethrow it so it is dealt with at a higher level.

Example Code

Output

Create Custom Exceptions

It is very simple to create your own custom Exception.

Источник

What’s the recommended way in Dart: asserts or throw Errors

Dart explicitly makes a distinction between Error, that signals a problem in your code’s logic and should never happen and should never be caught and Exceptions that signal a problem based on run-time data.

I really like this distinction but I wonder when should I then use assert() functions?

4 Answers 4

Asserts are ways to perform code useful in development only, without hindering the performances of release mode – usually to prevent bad states caused by a missing feature in the type system.

For example, only asserts can be used to do defensive programming and offer a const constructor.

Similarly, some sanity checks are relatively expensive.

In the context of Flutter, for example, you may want to traverse the widget tree to check something on the ancestors of a widget. But that’s costly, for something only useful to a developer.

Doing that check inside an assert allows both performance in release, and utility in development.

Background

- In Dart an Exception is for an expected bad state that may happen at runtime. Because these exceptions are expected, you should catch them and handle them appropriately.

- An Error , on the other hand, is for developers who are using your code. You throw an Error to let them know that they are using your code wrong. As the developer using an API, you shouldn’t catch errors. You should let them crash your app. Let the crash be a message to you that you need to go find out what you’re doing wrong.

- An assert is similar to an Error in that it is for reporting bad states that should never happen. The difference is that asserts are only checked in debug mode. They are completely ignored in production mode.

Read more on the difference between Exception and Error here.

Next, here are a few examples to see how each is used in the Flutter source code.

Example of throwing an Exception

The MissingPluginException here is a planned bad state that might occur. If it happens, users of the platform channel API need to be ready to handle that.

Example of throwing an Error

First every possibility is exhausted and then the error is thrown. This should be theoretically impossible. But if it is thrown, then it is either a sign to the API user that you’re using it wrong, or a sign to the API maintainer that they need to handle another case.

Example of using asserts

The pattern in the Flutter source code is to use asserts liberally in the initializer list in constructors. They are far more common than Errors.

Summary

As I read the Flutter source code, use asserts as preliminary checks in the constructor initializer list and throw errors as a last resort check in the body of methods. Of course this isn’t a hard and fast rule as far as I can see, but it seems to fit the pattern I’ve seen so far.

Источник

Error vs exception dart

Dart code can throw and catch exceptions. If the exception is not caught, the program will be terminated

All of Dart’s exceptions are unchecked exceptions compared to Java. Methods don’t declare exceptions they might throw, and you don’t need to catch any exceptions.

Dart provides Exception and Error types, as well as many predefined subtypes. Of course, you can define your own exceptions. Dart can throw any non null abnormal.

Throw an exception

The following is an example of throwing or throwing an exception:

You can also throw any object:

Note: The type of error or exception should be thrown as much as possible.

Because throwing an exception is an expression, so you can => Throw an exception in the statement and anywhere else in the expression is allowed:

capture

catching exceptions prevents exceptions from being passed (unless you rethrow the exception). Capturing exceptions gives you the opportunity to handle it:

To handle code that might throw multiple types of exceptions, you can specify multiple catch clauses. The first catch clause that matches the type of the thrown object handles the exception. If the catch clause does not specify a type, the clause can handle any type of throw object:

As shown in the previous code, you can use on or catch or both. Used when you need to specify an exception type. Use catch when the exception handler needs an exception object.

You can specify one or two parameters for catch(). The first is the exception thrown, and the second is the stack trace (StackTrace object):

To partially handle the exception while allowing it to propagate, please use rethrow Keywords:

Finally

Whether or not to throw an exception, make sure some code is running, please use finally Clause. If no catch clause matches the exception, the exception is passed after the finally clause is run:

class

Get the type of the object

To get the type of the object at runtime, you can use Object’s runtimeType Property, this property returns Type Object.

Here’s how to declare an instance variable:

All uninitialized instance variables have values of null 。

All instance variables generate an implicit getter method. Non-final instance variables will also generate implicit setter method.

Constructor :

Declare the constructor by creating a function with the same name as the class (in addition, optionally, as an additional identifier as described in the naming constructor). The most common constructor form, the build constructor, creates a new instance of a class:

The pattern of assigning constructor arguments to instance variables is so common, Dart has syntactic sugar, making it simple:

Default constructor

If you have not declared a constructor, it will provide you with a default constructor. The default constructor takes no arguments and calls the no-argument constructor in the superclass.

Constructor is not inherited

The subclass does not inherit constructors from its superclass. Subclasses that declare no constructors have only default (no arguments, no names) constructors.

Named constructor

uses a named constructor to implement multiple constructors for a class or to provide additional sharpness:

Keep in mind that constructors are not inherited, which means that the superclass’s named constructor is not inherited by subclasses. If you want to create a subclass using the named constructor defined in the superclass, you must implement the constructor in the subclass.

Call a non-default superclass constructor

By default, the constructor in a subclass calls the unnamed no-argument constructor of the superclass. The constructor of the superclass is called at the beginning of the constructor body. If the initialization list is also used, it is executed before the superclass is called. In summary, the order of execution is as follows:

- Initialization list

- Superclass’s no-argument constructor

- The no-argument constructor of the main class

If the superclass has no unnamed no-argument constructor, you must manually call one of the superclasses. Specify the superclass constructor after the colon (:), just before the constructor body (if any).

Constant constructor

If your class generates objects that never change, you can make these objects compile-time constants. To do this, define the const constructor and make sure all instance variables are final:

Factory builder

When implementing a constructor that does not always create a new instance of its class, use factory Keyword. For example, a factory constructor might return an instance from the cache, or it might return an instance of a subtype.

The following example demonstrates the factory constructor that returns an object from the cache:

Note: Factory constructor does not have access this 。

Call the factory constructor just like any other constructor:

getters and setters

getter with setter Is a special way to provide read and write access to object properties. Recall that each instance variable has an implicit getter , if appropriate, another setter . you can use it get with set Keyword through implementation getter with setter To create other properties:

Abstract method

Instance, getter, and setter methods can be abstract, define an interface, but leave its implementation to other classes. Abstract methods can only exist in abstract classes.

To make the method abstract, use a semicolon (;) Instead of the method body:

Abstract class

This is an example of a single class that implements multiple interfaces:

Inheritance

use extends Create a subclass, use super To reference the superclass:

Subclasses can override instance methods, getter with setter . you can use it @override A comment to indicate that you are interested in overwriting the member:

Overloaded operator

Note: If overwriting == , it should also be covered Object of hashCode Getter method.

Enumeration type

Each value in the enumeration has an index getter that returns the zero-based position of the value in the enumeration declaration. For example, the first value has index 0 and the second value has index 1:

mixins

Mixins are a way to reuse class code in multiple class hierarchies.

To use mixin, please use with The keyword is followed by one or more mixin names. The following example shows two classes that use mixins:

To implement a mixin, create an extension Object Class, and does not declare a constructor. Use unless you want mixin to be used as a regular class mixin Keywords instead of class 。

To specify that only certain types can be used mixin — For example, your mixin can call methods it doesn’t define, use on To specify the required superclass:

Источник

Dart – Types of Exceptions

Exception is a runtime unwanted event that disrupts the flow of code execution. It can be occurred because of a programmer’s mistake or by wrong user input. To handle such events at runtime is called Exception Handling. For example:- when we try to access the elements from the empty list. Dart Exceptions are the run-time error. It is raised when the program gets execution.

Built-in Exceptions in Dart:

The below table has a listing of principal dart exceptions.

| Sr. | Exceptions | Description |

| 1 | DefferedLoadException | It is thrown when a deferred library fails to load. |

| 2 | FormatException | It is the exception that is thrown when a string or some other data does not have an expected format |

| 3 | IntegerDivisionByZeroException | It is thrown when the number is divided by zero. |

| 4 | IOEException | It is the base class of input-output-related exceptions. |

| 5 | IsolateSpawnException | It is thrown when an isolated cannot be created. |

| 6 | Timeout | It is thrown when a scheduled timeout happens while waiting for an async result. |

Every built-in exception in Dart comes under a pre-defined class named Exception. To prevent the program from exception we make use of try/on/catch blocks in Dart.

- Try: In the try block, we write the logical code that can produce the exception

- Catch: Catch block is written with try block to catch the general exceptions: In other words, if it is not clear what kind of exception will be produced. Catch block is used.

- On: On the block is used when it is 100% sure what kind of exception will be thrown.

- Finally: The final part is always executed, but it is not mandatory.

Example 1: Using a try-on block in the dart.

Источник

keyboard_arrow_down

keyboard_arrow_up

- A basic Dart program

- Important concepts

- Keywords

- Variables

- Default value

- Late variables

- Final and const

- Built-in types

- Numbers

- Strings

- Booleans

- Lists

- Sets

- Maps

- Runes and grapheme clusters

- Symbols

- Functions

- Parameters

- The main() function

- Functions as first-class objects

- Anonymous functions

- Lexical scope

- Lexical closures

- Testing functions for equality

- Return values

- Operators

- Arithmetic operators

- Equality and relational operators

- Type test operators

- Assignment operators

- Logical operators

- Bitwise and shift operators

- Conditional expressions

- Cascade notation

- Other operators

- Control flow statements

- If and else

- For loops

- While and do-while

- Break and continue

- Switch and case

- Assert

- Exceptions

- Throw

- Catch

- Finally

- Classes

- Using class members

- Using constructors

- Getting an object’s type

- Instance variables

- Constructors

- Methods

- Abstract classes

- Implicit interfaces

- Extending a class

- Extension methods

- Enumerated types

- Adding features to a class: mixins

- Class variables and methods

- Generics

- Why use generics?

- Using collection literals

- Using parameterized types with constructors

- Generic collections and the types they contain

- Restricting the parameterized type

- Using generic methods

- Libraries and visibility

- Using libraries

- Implementing libraries

- Asynchrony support

- Handling Futures

- Declaring async functions

- Handling Streams

- Generators

- Callable classes

- Isolates

- Typedefs

- Metadata

- Comments

- Single-line comments

- Multi-line comments

- Documentation comments

- Summary

This page shows you how to use each major Dart feature, from

variables and operators to classes and libraries, with the assumption

that you already know how to program in another language.

For a briefer, less complete introduction to the language, see the

language samples page.

To learn more about Dart’s core libraries, see the

library tour.

Whenever you want more details about a language feature,

consult the Dart language specification.

A basic Dart program

The following code uses many of Dart’s most basic features:

// Define a function.

void printInteger(int aNumber) {

print('The number is $aNumber.'); // Print to console.

}

// This is where the app starts executing.

void main() {

var number = 42; // Declare and initialize a variable.

printInteger(number); // Call a function.

}Here’s what this program uses that applies to all (or almost all) Dart

apps:

// This is a comment.- A single-line comment.

Dart also supports multi-line and document comments.

For details, see Comments. void- A special type that indicates a value that’s never used.

Functions likeprintInteger()andmain()that don’t explicitly return a value

have thevoidreturn type. int- Another type, indicating an integer.

Some additional built-in types

areString,List, andbool. 42- A number literal. Number literals are a kind of compile-time constant.

print()- A handy way to display output.

-

'...'(or"...") - A string literal.

-

$variableName(or${expression}) - String interpolation: including a variable or expression’s string

equivalent inside of a string literal. For more information, see

Strings. main()- The special, required, top-level function where app execution

starts. For more information, see

The main() function. var- A way to declare a variable without specifying its type.

The type of this variable (int)

is determined by its initial value (42).

Important concepts

As you learn about the Dart language, keep these facts and concepts in

mind:

-

Everything you can place in a variable is an object, and every

object is an instance of a class. Even numbers, functions, and

nullare objects.

With the exception ofnull(if you enable sound null safety),

all objects inherit from theObjectclass. -

Although Dart is strongly typed, type annotations are optional

because Dart can infer types. In the code above,number

is inferred to be of typeint. -

If you enable null safety,

variables can’t containnullunless you say they can.

You can make a variable nullable by

putting a question mark (?) at the end of its type.

For example, a variable of typeint?might be an integer,

or it might benull.

If you know that an expression never evaluates tonull

but Dart disagrees,

you can add!to assert that it isn’t null

(and to throw an exception if it is).

An example:int x = nullableButNotNullInt! -

When you want to explicitly say

that any type is allowed, use the typeObject?

(if you’ve enabled null safety),Object,

or—if you must defer type checking until runtime—the

special typedynamic. -

Dart supports generic types, like

List<int>(a list of integers)

orList<Object>(a list of objects of any type). -

Dart supports top-level functions (such as

main()), as well as

functions tied to a class or object (static and instance

methods, respectively). You can also create functions within

functions (nested or local functions). -

Similarly, Dart supports top-level variables, as well as variables

tied to a class or object (static and instance variables). Instance

variables are sometimes known as fields or properties. -

Unlike Java, Dart doesn’t have the keywords

public,protected,

andprivate. If an identifier starts with an underscore (_), it’s

private to its library. For details, see

Libraries and visibility. -

Identifiers can start with a letter or underscore (

_), followed by any

combination of those characters plus digits. -

Dart has both expressions (which have runtime values) and

statements (which don’t).

For example, the conditional expression

condition ? expr1 : expr2has a value ofexpr1orexpr2.

Compare that to an if-else statement, which has no value.

A statement often contains one or more expressions,

but an expression can’t directly contain a statement. -

Dart tools can report two kinds of problems: warnings and errors.

Warnings are just indications that your code might not work, but

they don’t prevent your program from executing. Errors can be either

compile-time or run-time. A compile-time error prevents the code

from executing at all; a run-time error results in an

exception being raised while the code executes.

Keywords

The following table lists the words that the Dart language treats specially.

Avoid using these words as identifiers.

However, if necessary, the keywords marked with superscripts can be identifiers:

-

Words with the superscript 1 are contextual keywords,

which have meaning only in specific places.

They’re valid identifiers everywhere. -

Words with the superscript 2 are built-in identifiers.

These keywords are valid identifiers in most places,

but they can’t be used as class or type names, or as import prefixes. -

Words with the superscript 3 are limited reserved words related to

asynchrony support.

You can’t useawaitoryieldas an identifier

in any function body marked withasync,async*, orsync*.

All other words in the table are reserved words,

which can’t be identifiers.

Variables

Here’s an example of creating a variable and initializing it:

Variables store references. The variable called name contains a

reference to a String object with a value of “Bob”.

The type of the name variable is inferred to be String,

but you can change that type by specifying it.

If an object isn’t restricted to a single type,

specify the Object type (or dynamic if necessary).

Another option is to explicitly declare the type that would be inferred:

Default value

Uninitialized variables that have a nullable type

have an initial value of null.

(If you haven’t opted into null safety,

then every variable has a nullable type.)

Even variables with numeric types are initially null,

because numbers—like everything else in Dart—are objects.

int? lineCount;

assert(lineCount == null);If you enable null safety, then you must initialize the values

of non-nullable variables before you use them:

You don’t have to initialize a local variable where it’s declared,

but you do need to assign it a value before it’s used.

For example, the following code is valid because

Dart can detect that lineCount is non-null by the time

it’s passed to print():

int lineCount;

if (weLikeToCount) {

lineCount = countLines();

} else {

lineCount = 0;

}

print(lineCount);Top-level and class variables are lazily initialized;

the initialization code runs

the first time the variable is used.

Late variables

Dart 2.12 added the late modifier, which has two use cases:

- Declaring a non-nullable variable that’s initialized after its declaration.

- Lazily initializing a variable.

Often Dart’s control flow analysis can detect when a non-nullable variable

is set to a non-null value before it’s used,

but sometimes analysis fails.

Two common cases are top-level variables and instance variables:

Dart often can’t determine whether they’re set,

so it doesn’t try.

If you’re sure that a variable is set before it’s used,

but Dart disagrees,

you can fix the error by marking the variable as late:

late String description;

void main() {

description = 'Feijoada!';

print(description);

}When you mark a variable as late but initialize it at its declaration,

then the initializer runs the first time the variable is used.

This lazy initialization is handy in a couple of cases:

- The variable might not be needed,

and initializing it is costly. - You’re initializing an instance variable,

and its initializer needs access tothis.

In the following example,

if the temperature variable is never used,

then the expensive readThermometer() function is never called:

// This is the program's only call to readThermometer().

late String temperature = readThermometer(); // Lazily initialized.Final and const

If you never intend to change a variable, use final or const, either

instead of var or in addition to a type. A final variable can be set

only once; a const variable is a compile-time constant. (Const variables

are implicitly final.)

Here’s an example of creating and setting a final variable:

final name = 'Bob'; // Without a type annotation

final String nickname = 'Bobby';You can’t change the value of a final variable:

name = 'Alice'; // Error: a final variable can only be set once.Use const for variables that you want to be compile-time constants. If

the const variable is at the class level, mark it static const.

Where you declare the variable, set the value to a compile-time constant

such as a number or string literal, a const

variable, or the result of an arithmetic operation on constant numbers:

const bar = 1000000; // Unit of pressure (dynes/cm2)

const double atm = 1.01325 * bar; // Standard atmosphereThe const keyword isn’t just for declaring constant variables.

You can also use it to create constant values,

as well as to declare constructors that create constant values.

Any variable can have a constant value.

var foo = const [];

final bar = const [];

const baz = []; // Equivalent to `const []`You can omit const from the initializing expression of a const declaration,

like for baz above. For details, see DON’T use const redundantly.

You can change the value of a non-final, non-const variable,

even if it used to have a const value:

foo = [1, 2, 3]; // Was const []You can’t change the value of a const variable:

baz = [42]; // Error: Constant variables can't be assigned a value.You can define constants that use

type checks and casts (is and as),

collection if,

and spread operators (... and ...?):

const Object i = 3; // Where i is a const Object with an int value...

const list = [i as int]; // Use a typecast.

const map = {if (i is int) i: 'int'}; // Use is and collection if.

const set = {if (list is List<int>) ...list}; // ...and a spread.For more information on using const to create constant values, see

Lists, Maps, and Classes.

Built-in types

The Dart language has special support for the following:

-

Numbers (

int,double) -

Strings (

String) -

Booleans (

bool) -

Lists (

List, also known as arrays) -

Sets (

Set) -

Maps (

Map) -

Runes (

Runes; often replaced by thecharactersAPI) -

Symbols (

Symbol) - The value

null(Null)

This support includes the ability to create objects using literals.

For example, 'this is a string' is a string literal,

and true is a boolean literal.

Because every variable in Dart refers to an object—an instance of a

class—you can usually use constructors to initialize variables. Some

of the built-in types have their own constructors. For example, you can

use the Map() constructor to create a map.

Some other types also have special roles in the Dart language:

-

Object: The superclass of all Dart classes exceptNull. -

Enum: The superclass of all enums. -

FutureandStream: Used in asynchrony support. -

Iterable: Used in for-in loops and

in synchronous generator functions. -

Never: Indicates that an expression can never

successfully finish evaluating.

Most often used for functions that always throw an exception. -

dynamic: Indicates that you want to disable static checking.

Usually you should useObjectorObject?instead. -

void: Indicates that a value is never used.

Often used as a return type.

The Object, Object?, Null, and Never classes

have special roles in the class hierarchy,

as described in the top-and-bottom section of

Understanding null safety.

Numbers

Dart numbers come in two flavors:

int-

Integer values no larger than 64 bits,

depending on the platform.

On native platforms, values can be from

-263 to 263 — 1.

On the web, integer values are represented as JavaScript numbers

(64-bit floating-point values with no fractional part)

and can be from -253 to 253 — 1. double-

64-bit (double-precision) floating-point numbers, as specified by

the IEEE 754 standard.

Both int and double are subtypes of num.

The num type includes basic operators such as +, -, /, and *,

and is also where you’ll find abs(), ceil(),

and floor(), among other methods.

(Bitwise operators, such as >>, are defined in the int class.)

If num and its subtypes don’t have what you’re looking for, the

dart:math library might.

Integers are numbers without a decimal point. Here are some examples of

defining integer literals:

var x = 1;

var hex = 0xDEADBEEF;If a number includes a decimal, it is a double. Here are some examples

of defining double literals:

var y = 1.1;

var exponents = 1.42e5;You can also declare a variable as a num. If you do this, the variable

can have both integer and double values.

num x = 1; // x can have both int and double values

x += 2.5;Integer literals are automatically converted to doubles when necessary:

double z = 1; // Equivalent to double z = 1.0.Here’s how you turn a string into a number, or vice versa:

// String -> int

var one = int.parse('1');

assert(one == 1);

// String -> double

var onePointOne = double.parse('1.1');

assert(onePointOne == 1.1);

// int -> String

String oneAsString = 1.toString();

assert(oneAsString == '1');

// double -> String

String piAsString = 3.14159.toStringAsFixed(2);

assert(piAsString == '3.14');The int type specifies the traditional bitwise shift (<<, >>, >>>),

complement (~), AND (&), OR (|), and XOR (^) operators,

which are useful for manipulating and masking flags in bit fields.

For example:

assert((3 << 1) == 6); // 0011 << 1 == 0110

assert((3 | 4) == 7); // 0011 | 0100 == 0111

assert((3 & 4) == 0); // 0011 & 0100 == 0000For more examples, see the

bitwise and shift operator section.

Literal numbers are compile-time constants.

Many arithmetic expressions are also compile-time constants,

as long as their operands are

compile-time constants that evaluate to numbers.

const msPerSecond = 1000;

const secondsUntilRetry = 5;

const msUntilRetry = secondsUntilRetry * msPerSecond;For more information, see Numbers in Dart.

Strings

A Dart string (String object) holds a sequence of UTF-16 code units.

You can use either

single or double quotes to create a string:

var s1 = 'Single quotes work well for string literals.';

var s2 = "Double quotes work just as well.";

var s3 = 'It's easy to escape the string delimiter.';

var s4 = "It's even easier to use the other delimiter.";You can put the value of an expression inside a string by using

${expression}. If the expression is an identifier, you can skip

the {}. To get the string corresponding to an object, Dart calls the

object’s toString() method.

var s = 'string interpolation';

assert('Dart has $s, which is very handy.' ==

'Dart has string interpolation, '

'which is very handy.');

assert('That deserves all caps. '

'${s.toUpperCase()} is very handy!' ==

'That deserves all caps. '

'STRING INTERPOLATION is very handy!');You can concatenate strings using adjacent string literals or the +

operator:

var s1 = 'String '

'concatenation'

" works even over line breaks.";

assert(s1 ==

'String concatenation works even over '

'line breaks.');

var s2 = 'The + operator ' + 'works, as well.';

assert(s2 == 'The + operator works, as well.');Another way to create a multi-line string: use a triple quote with

either single or double quotation marks:

var s1 = '''

You can create

multi-line strings like this one.

''';

var s2 = """This is also a

multi-line string.""";You can create a “raw” string by prefixing it with r:

var s = r'In a raw string, not even n gets special treatment.';See Runes and grapheme clusters for details on how

to express Unicode characters in a string.

Literal strings are compile-time constants,

as long as any interpolated expression is a compile-time constant

that evaluates to null or a numeric, string, or boolean value.

// These work in a const string.

const aConstNum = 0;

const aConstBool = true;

const aConstString = 'a constant string';

// These do NOT work in a const string.

var aNum = 0;

var aBool = true;

var aString = 'a string';

const aConstList = [1, 2, 3];

const validConstString = '$aConstNum $aConstBool $aConstString';

// const invalidConstString = '$aNum $aBool $aString $aConstList';For more information on using strings, see

Strings and regular expressions.

Booleans

To represent boolean values, Dart has a type named bool. Only two

objects have type bool: the boolean literals true and false,

which are both compile-time constants.

Dart’s type safety means that you can’t use code like

if (nonbooleanValue) or

assert (nonbooleanValue).

Instead, explicitly check for values, like this:

// Check for an empty string.

var fullName = '';

assert(fullName.isEmpty);

// Check for zero.

var hitPoints = 0;

assert(hitPoints <= 0);

// Check for null.

var unicorn;

assert(unicorn == null);

// Check for NaN.

var iMeantToDoThis = 0 / 0;

assert(iMeantToDoThis.isNaN);Lists

Perhaps the most common collection in nearly every programming language

is the array, or ordered group of objects. In Dart, arrays are

List objects, so most people just call them lists.

Dart list literals are denoted by

a comma separated list of expressions or values,

enclosed in square brackets ([]).

Here’s a simple Dart list:

You can add a comma after the last item in a Dart collection literal.

This trailing comma doesn’t affect the collection,

but it can help prevent copy-paste errors.

var list = [

'Car',

'Boat',

'Plane',

];Lists use zero-based indexing, where 0 is the index of the first value

and list.length - 1 is the index of the last value.

You can get a list’s length using the .length property

and access a list’s values using the subscript operator ([]):

var list = [1, 2, 3];

assert(list.length == 3);

assert(list[1] == 2);

list[1] = 1;

assert(list[1] == 1);To create a list that’s a compile-time constant,

add const before the list literal:

var constantList = const [1, 2, 3];

// constantList[1] = 1; // This line will cause an error.

Dart supports the spread operator (...) and the

null-aware spread operator (...?),

which provide a concise way to insert multiple values into a collection.

For example, you can use the spread operator (...) to insert

all the values of a list into another list:

var list = [1, 2, 3];

var list2 = [0, ...list];

assert(list2.length == 4);If the expression to the right of the spread operator might be null,

you can avoid exceptions by using a null-aware spread operator (...?):

var list2 = [0, ...?list];

assert(list2.length == 1);For more details and examples of using the spread operator, see the

spread operator proposal.

Dart also offers collection if and collection for,

which you can use to build collections using conditionals (if)

and repetition (for).

Here’s an example of using collection if

to create a list with three or four items in it:

var nav = ['Home', 'Furniture', 'Plants', if (promoActive) 'Outlet'];Here’s an example of using collection for

to manipulate the items of a list before

adding them to another list:

var listOfInts = [1, 2, 3];

var listOfStrings = ['#0', for (var i in listOfInts) '#$i'];

assert(listOfStrings[1] == '#1');For more details and examples of using collection if and for, see the

control flow collections proposal.

The List type has many handy methods for manipulating lists. For more

information about lists, see Generics and

Collections.

Sets

A set in Dart is an unordered collection of unique items.

Dart support for sets is provided by set literals and the

Set type.

Here is a simple Dart set, created using a set literal:

var halogens = {'fluorine', 'chlorine', 'bromine', 'iodine', 'astatine'};To create an empty set, use {} preceded by a type argument,

or assign {} to a variable of type Set:

var names = <String>{};

// Set<String> names = {}; // This works, too.

// var names = {}; // Creates a map, not a set.Add items to an existing set using the add() or addAll() methods:

var elements = <String>{};

elements.add('fluorine');

elements.addAll(halogens);Use .length to get the number of items in the set:

var elements = <String>{};

elements.add('fluorine');

elements.addAll(halogens);

assert(elements.length == 5);To create a set that’s a compile-time constant,

add const before the set literal:

final constantSet = const {

'fluorine',

'chlorine',

'bromine',

'iodine',

'astatine',

};

// constantSet.add('helium'); // This line will cause an error.Sets support spread operators (... and ...?)

and collection if and for,

just like lists do.

For more information, see the

list spread operator and

list collection operator discussions.

For more information about sets, see

Generics and

Sets.

Maps

In general, a map is an object that associates keys and values. Both

keys and values can be any type of object. Each key occurs only once,

but you can use the same value multiple times. Dart support for maps

is provided by map literals and the Map type.

Here are a couple of simple Dart maps, created using map literals:

var gifts = {

// Key: Value

'first': 'partridge',

'second': 'turtledoves',

'fifth': 'golden rings'

};

var nobleGases = {

2: 'helium',

10: 'neon',

18: 'argon',

};You can create the same objects using a Map constructor:

var gifts = Map<String, String>();

gifts['first'] = 'partridge';

gifts['second'] = 'turtledoves';

gifts['fifth'] = 'golden rings';

var nobleGases = Map<int, String>();

nobleGases[2] = 'helium';

nobleGases[10] = 'neon';

nobleGases[18] = 'argon';Add a new key-value pair to an existing map

using the subscript assignment operator ([]=):

var gifts = {'first': 'partridge'};

gifts['fourth'] = 'calling birds'; // Add a key-value pairRetrieve a value from a map using the subscript operator ([]):

var gifts = {'first': 'partridge'};

assert(gifts['first'] == 'partridge');If you look for a key that isn’t in a map, you get null in return:

var gifts = {'first': 'partridge'};

assert(gifts['fifth'] == null);Use .length to get the number of key-value pairs in the map:

var gifts = {'first': 'partridge'};

gifts['fourth'] = 'calling birds';

assert(gifts.length == 2);To create a map that’s a compile-time constant,

add const before the map literal:

final constantMap = const {

2: 'helium',

10: 'neon',

18: 'argon',

};

// constantMap[2] = 'Helium'; // This line will cause an error.Maps support spread operators (... and ...?)

and collection if and for, just like lists do.

For details and examples, see the

spread operator proposal and the

control flow collections proposal.

For more information about maps, see the

generics section and

the library tour’s coverage of

the Maps API.

Runes and grapheme clusters

In Dart, runes expose the Unicode code points of a string.

You can use the characters package

to view or manipulate user-perceived characters,

also known as

Unicode (extended) grapheme clusters.

Unicode defines a unique numeric value for each letter, digit,

and symbol used in all of the world’s writing systems.

Because a Dart string is a sequence of UTF-16 code units,

expressing Unicode code points within a string requires

special syntax.

The usual way to express a Unicode code point is

uXXXX, where XXXX is a 4-digit hexadecimal value.

For example, the heart character (♥) is u2665.

To specify more or less than 4 hex digits,

place the value in curly brackets.

For example, the laughing emoji (😆) is u{1f606}.

If you need to read or write individual Unicode characters,

use the characters getter defined on String

by the characters package.

The returned Characters object is the string as

a sequence of grapheme clusters.

Here’s an example of using the characters API:

import 'package:characters/characters.dart';

void main() {

var hi = 'Hi 🇩🇰';

print(hi);

print('The end of the string: ${hi.substring(hi.length - 1)}');

print('The last character: ${hi.characters.last}');

}The output, depending on your environment, looks something like this:

$ dart run bin/main.dart

Hi 🇩🇰

The end of the string: ???

The last character: 🇩🇰

For details on using the characters package to manipulate strings,

see the example and API reference

for the characters package.

Symbols

A Symbol object

represents an operator or identifier declared in a Dart program. You

might never need to use symbols, but they’re invaluable for APIs that

refer to identifiers by name, because minification changes identifier

names but not identifier symbols.

To get the symbol for an identifier, use a symbol literal, which is just

# followed by the identifier:

#radix

#bar

Symbol literals are compile-time constants.

Functions

Dart is a true object-oriented language, so even functions are objects

and have a type, Function.

This means that functions can be assigned to variables or passed as arguments

to other functions. You can also call an instance of a Dart class as if

it were a function. For details, see Callable classes.

Here’s an example of implementing a function:

bool isNoble(int atomicNumber) {

return _nobleGases[atomicNumber] != null;

}Although Effective Dart recommends

type annotations for public APIs,

the function still works if you omit the types:

isNoble(atomicNumber) {

return _nobleGases[atomicNumber] != null;

}For functions that contain just one expression, you can use a shorthand

syntax:

bool isNoble(int atomicNumber) => _nobleGases[atomicNumber] != null;The => expr syntax is a shorthand for

{ return expr; }. The => notation

is sometimes referred to as arrow syntax.

Parameters

A function can have any number of required positional parameters. These can be

followed either by named parameters or by optional positional parameters

(but not both).

You can use trailing commas when you pass arguments to a function

or when you define function parameters.

Named parameters

Named parameters are optional

unless they’re explicitly marked as required.

When defining a function, use

{param1, param2, …}

to specify named parameters.

If you don’t provide a default value

or mark a named parameter as required,

their types must be nullable

as their default value will be null:

/// Sets the [bold] and [hidden] flags ...

void enableFlags({bool? bold, bool? hidden}) {...}When calling a function,

you can specify named arguments using

paramName: value.

For example:

enableFlags(bold: true, hidden: false);

To define a default value for a named parameter besides null,

use = to specify a default value.

The specified value must be a compile-time constant.

For example:

/// Sets the [bold] and [hidden] flags ...

void enableFlags({bool bold = false, bool hidden = false}) {...}

// bold will be true; hidden will be false.

enableFlags(bold: true);If you instead want a named parameter to be mandatory,

requiring callers to provide a value for the parameter,

annotate them with required:

const Scrollbar({super.key, required Widget child});If someone tries to create a Scrollbar

without specifying the child argument,

then the analyzer reports an issue.

You might want to place positional arguments first,

but Dart doesn’t require it.

Dart allows named arguments to be placed anywhere in the

argument list when it suits your API:

repeat(times: 2, () {

...

});Optional positional parameters

Wrapping a set of function parameters in []

marks them as optional positional parameters.

If you don’t provide a default value,

their types must be nullable

as their default value will be null:

String say(String from, String msg, [String? device]) {

var result = '$from says $msg';

if (device != null) {

result = '$result with a $device';

}

return result;

}Here’s an example of calling this function

without the optional parameter:

assert(say('Bob', 'Howdy') == 'Bob says Howdy');And here’s an example of calling this function with the third parameter:

assert(say('Bob', 'Howdy', 'smoke signal') ==

'Bob says Howdy with a smoke signal');To define a default value for an optional positional parameter besides null,

use = to specify a default value.

The specified value must be a compile-time constant.

For example:

String say(String from, String msg, [String device = 'carrier pigeon']) {

var result = '$from says $msg with a $device';

return result;

}

assert(say('Bob', 'Howdy') == 'Bob says Howdy with a carrier pigeon');The main() function

Every app must have a top-level main() function, which serves as the

entrypoint to the app. The main() function returns void and has an

optional List<String> parameter for arguments.

Here’s a simple main() function:

void main() {

print('Hello, World!');

}Here’s an example of the main() function for a command-line app that

takes arguments:

// Run the app like this: dart args.dart 1 test

void main(List<String> arguments) {

print(arguments);

assert(arguments.length == 2);

assert(int.parse(arguments[0]) == 1);

assert(arguments[1] == 'test');

}You can use the args library to

define and parse command-line arguments.

Functions as first-class objects

You can pass a function as a parameter to another function. For example:

void printElement(int element) {

print(element);

}

var list = [1, 2, 3];

// Pass printElement as a parameter.

list.forEach(printElement);You can also assign a function to a variable, such as:

var loudify = (msg) => '!!! ${msg.toUpperCase()} !!!';

assert(loudify('hello') == '!!! HELLO !!!');This example uses an anonymous function.

More about those in the next section.

Anonymous functions

Most functions are named, such as main() or printElement().

You can also create a nameless function

called an anonymous function, or sometimes a lambda or closure.

You might assign an anonymous function to a variable so that,

for example, you can add or remove it from a collection.

An anonymous function looks similar

to a named function—zero or more parameters, separated by commas

and optional type annotations, between parentheses.

The code block that follows contains the function’s body:

([[Type] param1[, …]]) {

codeBlock;

};

The following example defines an anonymous function

with an untyped parameter, item,

and passes it to the map function.

The function, invoked for each item in the list,

converts each string to uppercase.

Then in the anonymous function passed to forEach,

each converted string is printed out alongside its length.

const list = ['apples', 'bananas', 'oranges'];

list.map((item) {

return item.toUpperCase();

}).forEach((item) {

print('$item: ${item.length}');

});Click Run to execute the code.

void main() {

const list = ['apples', 'bananas', 'oranges'];

list.map((item) {

return item.toUpperCase();

}).forEach((item) {

print('$item: ${item.length}');

});

}If the function contains only a single expression or return statement,

you can shorten it using arrow notation.

Paste the following line into DartPad and click Run

to verify that it is functionally equivalent.

list

.map((item) => item.toUpperCase())

.forEach((item) => print('$item: ${item.length}'));Lexical scope

Dart is a lexically scoped language, which means that the scope of

variables is determined statically, simply by the layout of the code.

You can “follow the curly braces outwards” to see if a variable is in

scope.

Here is an example of nested functions with variables at each scope

level:

bool topLevel = true;

void main() {

var insideMain = true;

void myFunction() {

var insideFunction = true;

void nestedFunction() {

var insideNestedFunction = true;

assert(topLevel);

assert(insideMain);

assert(insideFunction);

assert(insideNestedFunction);

}

}

}Notice how nestedFunction() can use variables from every level, all

the way up to the top level.

Lexical closures

A closure is a function object that has access to variables in its

lexical scope, even when the function is used outside of its original

scope.

Functions can close over variables defined in surrounding scopes. In the

following example, makeAdder() captures the variable addBy. Wherever the

returned function goes, it remembers addBy.

/// Returns a function that adds [addBy] to the

/// function's argument.

Function makeAdder(int addBy) {

return (int i) => addBy + i;

}

void main() {

// Create a function that adds 2.

var add2 = makeAdder(2);

// Create a function that adds 4.

var add4 = makeAdder(4);

assert(add2(3) == 5);

assert(add4(3) == 7);

}Testing functions for equality

Here’s an example of testing top-level functions, static methods, and

instance methods for equality:

void foo() {} // A top-level function

class A {

static void bar() {} // A static method

void baz() {} // An instance method

}

void main() {

Function x;

// Comparing top-level functions.

x = foo;

assert(foo == x);

// Comparing static methods.

x = A.bar;

assert(A.bar == x);

// Comparing instance methods.

var v = A(); // Instance #1 of A

var w = A(); // Instance #2 of A

var y = w;

x = w.baz;

// These closures refer to the same instance (#2),

// so they're equal.

assert(y.baz == x);

// These closures refer to different instances,

// so they're unequal.

assert(v.baz != w.baz);

}Return values

All functions return a value. If no return value is specified, the

statement return null; is implicitly appended to the function body.

foo() {}

assert(foo() == null);Operators

Dart supports the operators shown in the following table.

The table shows Dart’s operator associativity

and operator precedence from highest to lowest,

which are an approximation of Dart’s operator relationships.

You can implement many of these operators as class members.

| Description | Operator | Associativity |

|---|---|---|

| unary postfix |

expr++ expr-- () [] ?[] . ?. !

|

None |

| unary prefix |

-expr !expr ~expr ++expr --expr await expr |

None |

| multiplicative |

* / % ~/

|

Left |

| additive |

+ -

|

Left |

| shift |

<< >> >>>

|

Left |

| bitwise AND | & |

Left |

| bitwise XOR | ^ |

Left |

| bitwise OR | | |

Left |

| relational and type test |

>= > <= < as is is!

|

None |

| equality |

== != |

None |

| logical AND | && |

Left |

| logical OR | || |

Left |

| if null | ?? |

Left |

| conditional | expr1 ? expr2 : expr3 |

Right |

| cascade |

.. ?..

|

Left |

| assignment |

= *= /= += -= &= ^= etc.

|

Right |

When you use operators, you create expressions. Here are some examples

of operator expressions:

a++

a + b

a = b

a == b

c ? a : b

a is T

In the operator table,

each operator has higher precedence than the operators in the rows

that follow it. For example, the multiplicative operator % has higher

precedence than (and thus executes before) the equality operator ==,

which has higher precedence than the logical AND operator &&. That

precedence means that the following two lines of code execute the same

way:

// Parentheses improve readability.

if ((n % i == 0) && (d % i == 0)) ...

// Harder to read, but equivalent.

if (n % i == 0 && d % i == 0) ...Arithmetic operators

Dart supports the usual arithmetic operators, as shown in the following table.

| Operator | Meaning |

|---|---|

+ |

Add |

- |

Subtract |

-expr |

Unary minus, also known as negation (reverse the sign of the expression) |

* |

Multiply |

/ |

Divide |

~/ |

Divide, returning an integer result |

% |

Get the remainder of an integer division (modulo) |

Example:

assert(2 + 3 == 5);

assert(2 - 3 == -1);

assert(2 * 3 == 6);

assert(5 / 2 == 2.5); // Result is a double

assert(5 ~/ 2 == 2); // Result is an int

assert(5 % 2 == 1); // Remainder

assert('5/2 = ${5 ~/ 2} r ${5 % 2}' == '5/2 = 2 r 1');Dart also supports both prefix and postfix increment and decrement

operators.

| Operator | Meaning |

|---|---|

++var |

var = var + 1 (expression value is var + 1) |

var++ |

var = var + 1 (expression value is var) |

--var |

var = var - 1 (expression value is var - 1) |

var-- |

var = var - 1 (expression value is var) |

Example:

int a;

int b;

a = 0;

b = ++a; // Increment a before b gets its value.

assert(a == b); // 1 == 1

a = 0;

b = a++; // Increment a AFTER b gets its value.

assert(a != b); // 1 != 0

a = 0;

b = --a; // Decrement a before b gets its value.

assert(a == b); // -1 == -1

a = 0;

b = a--; // Decrement a AFTER b gets its value.

assert(a != b); // -1 != 0Equality and relational operators

The following table lists the meanings of equality and relational operators.

| Operator | Meaning |

|---|---|

== |

Equal; see discussion below |

!= |

Not equal |

> |

Greater than |

< |

Less than |

>= |

Greater than or equal to |

<= |

Less than or equal to |

To test whether two objects x and y represent the same thing, use the

== operator. (In the rare case where you need to know whether two

objects are the exact same object, use the identical()

function instead.) Here’s how the == operator works:

-

If x or y is null, return true if both are null, and false if only

one is null. -

Return the result of invoking the

==method on x with the argument y.

(That’s right, operators such as==are methods that

are invoked on their first operand.

For details, see Operators.)

Here’s an example of using each of the equality and relational

operators:

assert(2 == 2);

assert(2 != 3);

assert(3 > 2);

assert(2 < 3);

assert(3 >= 3);

assert(2 <= 3);Type test operators

The as, is, and is! operators are handy for checking types at

runtime.

| Operator | Meaning |

|---|---|

as |

Typecast (also used to specify library prefixes) |

is |

True if the object has the specified type |

is! |

True if the object doesn’t have the specified type |

The result of obj is T is true if obj implements the interface

specified by T. For example, obj is Object? is always true.

Use the as operator to cast an object to a particular type if and only if

you are sure that the object is of that type. Example:

(employee as Person).firstName = 'Bob';If you aren’t sure that the object is of type T, then use is T to check the

type before using the object.

if (employee is Person) {

// Type check

employee.firstName = 'Bob';

}Assignment operators

As you’ve already seen, you can assign values using the = operator.

To assign only if the assigned-to variable is null,

use the ??= operator.

// Assign value to a

a = value;

// Assign value to b if b is null; otherwise, b stays the same

b ??= value;Compound assignment operators such as += combine

an operation with an assignment.

= |

*= |

%= |

>>>= |

^= |

+= |

/= |

<<= |

&= |

|= |

-= |

~/= |

>>= |

Here’s how compound assignment operators work:

| Compound assignment | Equivalent expression | |

|---|---|---|

| For an operator op: | a op= b |

a = a op b |

| Example: | a += b |

a = a + b |

The following example uses assignment and compound assignment

operators:

var a = 2; // Assign using =

a *= 3; // Assign and multiply: a = a * 3

assert(a == 6);Logical operators

You can invert or combine boolean expressions using the logical

operators.

| Operator | Meaning |

|---|---|

!expr |

inverts the following expression (changes false to true, and vice versa) |

|| |

logical OR |

&& |

logical AND |

Here’s an example of using the logical operators:

if (!done && (col == 0 || col == 3)) {

// ...Do something...

}Bitwise and shift operators

You can manipulate the individual bits of numbers in Dart. Usually,

you’d use these bitwise and shift operators with integers.

| Operator | Meaning |

|---|---|

& |

AND |

| |

OR |

^ |

XOR |

~expr |

Unary bitwise complement (0s become 1s; 1s become 0s) |

<< |

Shift left |

>> |

Shift right |

>>> |

Unsigned shift right |

Here’s an example of using bitwise and shift operators:

final value = 0x22;

final bitmask = 0x0f;

assert((value & bitmask) == 0x02); // AND

assert((value & ~bitmask) == 0x20); // AND NOT

assert((value | bitmask) == 0x2f); // OR

assert((value ^ bitmask) == 0x2d); // XOR

assert((value << 4) == 0x220); // Shift left

assert((value >> 4) == 0x02); // Shift right

assert((value >>> 4) == 0x02); // Unsigned shift right

assert((-value >> 4) == -0x03); // Shift right

assert((-value >>> 4) > 0); // Unsigned shift rightConditional expressions

Dart has two operators that let you concisely evaluate expressions

that might otherwise require if-else statements:

condition ? expr1 : expr2- If condition is true, evaluates expr1 (and returns its value);

otherwise, evaluates and returns the value of expr2. expr1 ?? expr2- If expr1 is non-null, returns its value;

otherwise, evaluates and returns the value of expr2.

When you need to assign a value

based on a boolean expression,

consider using ? and :.

var visibility = isPublic ? 'public' : 'private';If the boolean expression tests for null,

consider using ??.

String playerName(String? name) => name ?? 'Guest';The previous example could have been written at least two other ways,

but not as succinctly:

// Slightly longer version uses ?: operator.

String playerName(String? name) => name != null ? name : 'Guest';

// Very long version uses if-else statement.

String playerName(String? name) {

if (name != null) {

return name;

} else {

return 'Guest';

}

}Cascade notation

Cascades (.., ?..) allow you to make a sequence of operations

on the same object. In addition to accessing instance members,

you can also call instance methods on that same object.

This often saves you the step of creating a temporary variable and

allows you to write more fluid code.

Consider the following code:

var paint = Paint()

..color = Colors.black

..strokeCap = StrokeCap.round

..strokeWidth = 5.0;The constructor, Paint(),

returns a Paint object.

The code that follows the cascade notation operates

on this object, ignoring any values that

might be returned.

The previous example is equivalent to this code:

var paint = Paint();

paint.color = Colors.black;

paint.strokeCap = StrokeCap.round;

paint.strokeWidth = 5.0;If the object that the cascade operates on can be null,

then use a null-shorting cascade (?..) for the first operation.

Starting with ?.. guarantees that none of the cascade operations

are attempted on that null object.

querySelector('#confirm') // Get an object.

?..text = 'Confirm' // Use its members.

..classes.add('important')

..onClick.listen((e) => window.alert('Confirmed!'))

..scrollIntoView();The previous code is equivalent to the following:

var button = querySelector('#confirm');

button?.text = 'Confirm';

button?.classes.add('important');

button?.onClick.listen((e) => window.alert('Confirmed!'));

button?.scrollIntoView();You can also nest cascades. For example:

final addressBook = (AddressBookBuilder()

..name = 'jenny'

..email = 'jenny@example.com'

..phone = (PhoneNumberBuilder()

..number = '415-555-0100'

..label = 'home')

.build())

.build();Be careful to construct your cascade on a function that returns

an actual object. For example, the following code fails:

var sb = StringBuffer();

sb.write('foo')

..write('bar'); // Error: method 'write' isn't defined for 'void'.The sb.write() call returns void,

and you can’t construct a cascade on void.

Other operators

You’ve seen most of the remaining operators in other examples:

| Operator | Name | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

() |

Function application | Represents a function call |

[] |

Subscript access | Represents a call to the overridable [] operator; example: fooList[1] passes the int 1 to fooList to access the element at index 1

|

?[] |

Conditional subscript access | Like [], but the leftmost operand can be null; example: fooList?[1] passes the int 1 to fooList to access the element at index 1 unless fooList is null (in which case the expression evaluates to null) |

. |

Member access | Refers to a property of an expression; example: foo.bar selects property bar from expression foo

|

?. |

Conditional member access | Like ., but the leftmost operand can be null; example: foo?.bar selects property bar from expression foo unless foo is null (in which case the value of foo?.bar is null) |

! |

Null assertion operator | Casts an expression to its underlying non-nullable type, throwing a runtime exception if the cast fails; example: foo!.bar asserts foo is non-null and selects the property bar, unless foo is null in which case a runtime exception is thrown |

For more information about the ., ?., and .. operators, see

Classes.

Control flow statements

You can control the flow of your Dart code using any of the following:

-

ifandelse -

forloops -

whileanddo—whileloops -

breakandcontinue -

switchandcase assert

You can also affect the control flow using try-catch and throw, as

explained in Exceptions.

If and else

Dart supports if statements with optional else statements, as the

next sample shows. Also see conditional expressions.

if (isRaining()) {

you.bringRainCoat();

} else if (isSnowing()) {

you.wearJacket();

} else {

car.putTopDown();

}The statement conditions must be expressions

that evaluate to boolean values, nothing else.

See Booleans for more information.

For loops

You can iterate with the standard for loop. For example:

var message = StringBuffer('Dart is fun');

for (var i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

message.write('!');

}Closures inside of Dart’s for loops capture the value of the index,

avoiding a common pitfall found in JavaScript. For example, consider:

var callbacks = [];

for (var i = 0; i < 2; i++) {

callbacks.add(() => print(i));

}

for (final c in callbacks) {

c();

}The output is 0 and then 1, as expected. In contrast, the example

would print 2 and then 2 in JavaScript.

If the object that you are iterating over is an Iterable (such as List or Set)

and if you don’t need to know the current iteration counter,

you can use the for-in form of iteration:

for (final candidate in candidates) {

candidate.interview();

}Iterable classes also have a forEach() method as another option:

var collection = [1, 2, 3];

collection.forEach(print); // 1 2 3While and do-while

A while loop evaluates the condition before the loop:

while (!isDone()) {

doSomething();

}A do—while loop evaluates the condition after the loop:

do {

printLine();

} while (!atEndOfPage());Break and continue

Use break to stop looping:

while (true) {

if (shutDownRequested()) break;

processIncomingRequests();

}Use continue to skip to the next loop iteration:

for (int i = 0; i < candidates.length; i++) {

var candidate = candidates[i];

if (candidate.yearsExperience < 5) {

continue;

}

candidate.interview();

}You might write that example differently if you’re using an

Iterable such as a list or set:

candidates

.where((c) => c.yearsExperience >= 5)

.forEach((c) => c.interview());Switch and case

Switch statements in Dart compare integer, string, or compile-time

constants using ==. The compared objects must all be instances of the

same class (and not of any of its subtypes), and the class must not

override ==.

Enumerated types work well in switch statements.

Each non-empty case clause ends with a break statement, as a rule.

Other valid ways to end a non-empty case clause are a continue,

throw, or return statement.

Use a default clause to execute code when no case clause matches:

var command = 'OPEN';

switch (command) {

case 'CLOSED':

executeClosed();

break;

case 'PENDING':

executePending();

break;

case 'APPROVED':

executeApproved();

break;

case 'DENIED':

executeDenied();

break;

case 'OPEN':

executeOpen();

break;

default:

executeUnknown();

}The following example omits the break statement in a case clause,

thus generating an error:

var command = 'OPEN';

switch (command) {

case 'OPEN':

executeOpen();

// ERROR: Missing break

case 'CLOSED':

executeClosed();

break;

}However, Dart does support empty case clauses, allowing a form of

fall-through:

var command = 'CLOSED';

switch (command) {

case 'CLOSED': // Empty case falls through.

case 'NOW_CLOSED':

// Runs for both CLOSED and NOW_CLOSED.

executeNowClosed();

break;

}If you really want fall-through, you can use a continue statement and

a label:

var command = 'CLOSED';

switch (command) {

case 'CLOSED':

executeClosed();

continue nowClosed;

// Continues executing at the nowClosed label.

nowClosed:

case 'NOW_CLOSED':

// Runs for both CLOSED and NOW_CLOSED.

executeNowClosed();

break;

}A case clause can have local variables, which are visible only inside

the scope of that clause.

Assert

During development, use an assert

statement—assert(condition, optionalMessage);—to

disrupt normal execution if a boolean condition is false.

You can find examples of assert statements throughout this tour.

Here are some more:

// Make sure the variable has a non-null value.

assert(text != null);

// Make sure the value is less than 100.

assert(number < 100);

// Make sure this is an https URL.

assert(urlString.startsWith('https'));To attach a message to an assertion,

add a string as the second argument to assert

(optionally with a trailing comma):

assert(urlString.startsWith('https'),

'URL ($urlString) should start with "https".');The first argument to assert can be any expression that

resolves to a boolean value. If the expression’s value

is true, the assertion succeeds and execution

continues. If it’s false, the assertion fails and an exception (an

AssertionError) is thrown.

When exactly do assertions work?

That depends on the tools and framework you’re using:

- Flutter enables assertions in debug mode.

- Development-only tools such as [

webdev serve][]

typically enable assertions by default. - Some tools, such as

dart runand [dart compile js][]

support assertions through a command-line flag:--enable-asserts.

In production code, assertions are ignored, and

the arguments to assert aren’t evaluated.

Exceptions

Your Dart code can throw and catch exceptions. Exceptions are errors

indicating that something unexpected happened. If the exception isn’t

caught, the isolate that raised the exception is suspended,

and typically the isolate and its program are terminated.

In contrast to Java, all of Dart’s exceptions are unchecked exceptions.

Methods don’t declare which exceptions they might throw, and you aren’t

required to catch any exceptions.

Dart provides Exception and Error

types, as well as numerous predefined subtypes. You can, of course,

define your own exceptions. However, Dart programs can throw any

non-null object—not just Exception and Error objects—as an exception.

Throw

Here’s an example of throwing, or raising, an exception:

throw FormatException('Expected at least 1 section');You can also throw arbitrary objects:

Because throwing an exception is an expression, you can throw exceptions

in => statements, as well as anywhere else that allows expressions:

void distanceTo(Point other) => throw UnimplementedError();Catch

Catching, or capturing, an exception stops the exception from

propagating (unless you rethrow the exception).

Catching an exception gives you a chance to handle it:

try {

breedMoreLlamas();

} on OutOfLlamasException {

buyMoreLlamas();

}To handle code that can throw more than one type of exception, you can

specify multiple catch clauses. The first catch clause that matches the

thrown object’s type handles the exception. If the catch clause does not

specify a type, that clause can handle any type of thrown object:

try {

breedMoreLlamas();

} on OutOfLlamasException {

// A specific exception

buyMoreLlamas();

} on Exception catch (e) {

// Anything else that is an exception

print('Unknown exception: $e');

} catch (e) {

// No specified type, handles all

print('Something really unknown: $e');

}As the preceding code shows, you can use either on or catch or both.

Use on when you need to specify the exception type. Use catch when

your exception handler needs the exception object.

You can specify one or two parameters to catch().

The first is the exception that was thrown,

and the second is the stack trace (a StackTrace object).

try {

// ···

} on Exception catch (e) {

print('Exception details:n $e');

} catch (e, s) {

print('Exception details:n $e');

print('Stack trace:n $s');

}To partially handle an exception,

while allowing it to propagate,

use the rethrow keyword.

void misbehave() {

try {

dynamic foo = true;

print(foo++); // Runtime error

} catch (e) {

print('misbehave() partially handled ${e.runtimeType}.');

rethrow; // Allow callers to see the exception.

}

}

void main() {

try {

misbehave();

} catch (e) {

print('main() finished handling ${e.runtimeType}.');

}

}Finally

To ensure that some code runs whether or not an exception is thrown, use

a finally clause. If no catch clause matches the exception, the

exception is propagated after the finally clause runs:

try {

breedMoreLlamas();

} finally {

// Always clean up, even if an exception is thrown.

cleanLlamaStalls();

}The finally clause runs after any matching catch clauses:

try {

breedMoreLlamas();

} catch (e) {

print('Error: $e'); // Handle the exception first.

} finally {

cleanLlamaStalls(); // Then clean up.

}Learn more by reading the

Exceptions