Package errors implements functions to manipulate errors.

The New function creates errors whose only content is a text message.

An error e wraps another error if e’s type has one of the methods

Unwrap() error Unwrap() []error

If e.Unwrap() returns a non-nil error w or a slice containing w,

then we say that e wraps w. A nil error returned from e.Unwrap()

indicates that e does not wrap any error. It is invalid for an

Unwrap method to return an []error containing a nil error value.

An easy way to create wrapped errors is to call fmt.Errorf and apply

the %w verb to the error argument:

wrapsErr := fmt.Errorf("... %w ...", ..., err, ...)

Successive unwrapping of an error creates a tree. The Is and As

functions inspect an error’s tree by examining first the error

itself followed by the tree of each of its children in turn

(pre-order, depth-first traversal).

Is examines the tree of its first argument looking for an error that

matches the second. It reports whether it finds a match. It should be

used in preference to simple equality checks:

if errors.Is(err, fs.ErrExist)

is preferable to

if err == fs.ErrExist

because the former will succeed if err wraps fs.ErrExist.

As examines the tree of its first argument looking for an error that can be

assigned to its second argument, which must be a pointer. If it succeeds, it

performs the assignment and returns true. Otherwise, it returns false. The form

var perr *fs.PathError

if errors.As(err, &perr) {

fmt.Println(perr.Path)

}

is preferable to

if perr, ok := err.(*fs.PathError); ok {

fmt.Println(perr.Path)

}

because the former will succeed if err wraps an *fs.PathError.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

// MyError is an error implementation that includes a time and message.

type MyError struct {

When time.Time

What string

}

func (e MyError) Error() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("%v: %v", e.When, e.What)

}

func oops() error {

return MyError{

time.Date(1989, 3, 15, 22, 30, 0, 0, time.UTC),

"the file system has gone away",

}

}

func main() {

if err := oops(); err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

}

}

Output: 1989-03-15 22:30:00 +0000 UTC: the file system has gone away

- func As(err error, target any) bool

- func Is(err, target error) bool

- func Join(errs …error) error

- func New(text string) error

- func Unwrap(err error) error

- Package

- As

- Is

- Join

- New

- New (Errorf)

- Unwrap

This section is empty.

This section is empty.

As finds the first error in err’s tree that matches target, and if one is found, sets

target to that error value and returns true. Otherwise, it returns false.

The tree consists of err itself, followed by the errors obtained by repeatedly

calling Unwrap. When err wraps multiple errors, As examines err followed by a

depth-first traversal of its children.

An error matches target if the error’s concrete value is assignable to the value

pointed to by target, or if the error has a method As(interface{}) bool such that

As(target) returns true. In the latter case, the As method is responsible for

setting target.

An error type might provide an As method so it can be treated as if it were a

different error type.

As panics if target is not a non-nil pointer to either a type that implements

error, or to any interface type.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

"io/fs"

"os"

)

func main() {

if _, err := os.Open("non-existing"); err != nil {

var pathError *fs.PathError

if errors.As(err, &pathError) {

fmt.Println("Failed at path:", pathError.Path)

} else {

fmt.Println(err)

}

}

}

Output: Failed at path: non-existing

Is reports whether any error in err’s tree matches target.

The tree consists of err itself, followed by the errors obtained by repeatedly

calling Unwrap. When err wraps multiple errors, Is examines err followed by a

depth-first traversal of its children.

An error is considered to match a target if it is equal to that target or if

it implements a method Is(error) bool such that Is(target) returns true.

An error type might provide an Is method so it can be treated as equivalent

to an existing error. For example, if MyError defines

func (m MyError) Is(target error) bool { return target == fs.ErrExist }

then Is(MyError{}, fs.ErrExist) returns true. See syscall.Errno.Is for

an example in the standard library. An Is method should only shallowly

compare err and the target and not call Unwrap on either.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

"io/fs"

"os"

)

func main() {

if _, err := os.Open("non-existing"); err != nil {

if errors.Is(err, fs.ErrNotExist) {

fmt.Println("file does not exist")

} else {

fmt.Println(err)

}

}

}

Output: file does not exist

Join returns an error that wraps the given errors.

Any nil error values are discarded.

Join returns nil if errs contains no non-nil values.

The error formats as the concatenation of the strings obtained

by calling the Error method of each element of errs, with a newline

between each string.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

)

func main() {

err1 := errors.New("err1")

err2 := errors.New("err2")

err := errors.Join(err1, err2)

fmt.Println(err)

if errors.Is(err, err1) {

fmt.Println("err is err1")

}

if errors.Is(err, err2) {

fmt.Println("err is err2")

}

}

Output: err1 err2 err is err1 err is err2

New returns an error that formats as the given text.

Each call to New returns a distinct error value even if the text is identical.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

)

func main() {

err := errors.New("emit macho dwarf: elf header corrupted")

if err != nil {

fmt.Print(err)

}

}

Output: emit macho dwarf: elf header corrupted

The fmt package’s Errorf function lets us use the package’s formatting

features to create descriptive error messages.

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func main() {

const name, id = "bimmler", 17

err := fmt.Errorf("user %q (id %d) not found", name, id)

if err != nil {

fmt.Print(err)

}

}

Output: user "bimmler" (id 17) not found

Unwrap returns the result of calling the Unwrap method on err, if err’s

type contains an Unwrap method returning error.

Otherwise, Unwrap returns nil.

Unwrap returns nil if the Unwrap method returns []error.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

)

func main() {

err1 := errors.New("error1")

err2 := fmt.Errorf("error2: [%w]", err1)

fmt.Println(err2)

fmt.Println(errors.Unwrap(err2))

// Output

// error2: [error1]

// error1

}

Output:

This section is empty.

import "errors"

- Overview

- Index

- Examples

Overview ▸

Overview ▾

Package errors implements functions to manipulate errors.

The New function creates errors whose only content is a text message.

An error e wraps another error if e’s type has one of the methods

Unwrap() error Unwrap() []error

If e.Unwrap() returns a non-nil error w or a slice containing w,

then we say that e wraps w. A nil error returned from e.Unwrap()

indicates that e does not wrap any error. It is invalid for an

Unwrap method to return an []error containing a nil error value.

An easy way to create wrapped errors is to call fmt.Errorf and apply

the %w verb to the error argument:

wrapsErr := fmt.Errorf("... %w ...", ..., err, ...)

Successive unwrapping of an error creates a tree. The Is and As

functions inspect an error’s tree by examining first the error

itself followed by the tree of each of its children in turn

(pre-order, depth-first traversal).

Is examines the tree of its first argument looking for an error that

matches the second. It reports whether it finds a match. It should be

used in preference to simple equality checks:

if errors.Is(err, fs.ErrExist)

is preferable to

if err == fs.ErrExist

because the former will succeed if err wraps fs.ErrExist.

As examines the tree of its first argument looking for an error that can be

assigned to its second argument, which must be a pointer. If it succeeds, it

performs the assignment and returns true. Otherwise, it returns false. The form

var perr *fs.PathError

if errors.As(err, &perr) {

fmt.Println(perr.Path)

}

is preferable to

if perr, ok := err.(*fs.PathError); ok {

fmt.Println(perr.Path)

}

because the former will succeed if err wraps an *fs.PathError.

▸ Example

▾ Example

1989-03-15 22:30:00 +0000 UTC: the file system has gone away

Index ▸

func As

¶

1.13

func As(err error, target any) bool

As finds the first error in err’s tree that matches target, and if one is found, sets

target to that error value and returns true. Otherwise, it returns false.

The tree consists of err itself, followed by the errors obtained by repeatedly

calling Unwrap. When err wraps multiple errors, As examines err followed by a

depth-first traversal of its children.

An error matches target if the error’s concrete value is assignable to the value

pointed to by target, or if the error has a method As(interface{}) bool such that

As(target) returns true. In the latter case, the As method is responsible for

setting target.

An error type might provide an As method so it can be treated as if it were a

different error type.

As panics if target is not a non-nil pointer to either a type that implements

error, or to any interface type.

▸ Example

▾ Example

Failed at path: non-existing

func Is

¶

1.13

func Is(err, target error) bool

Is reports whether any error in err’s tree matches target.

The tree consists of err itself, followed by the errors obtained by repeatedly

calling Unwrap. When err wraps multiple errors, Is examines err followed by a

depth-first traversal of its children.

An error is considered to match a target if it is equal to that target or if

it implements a method Is(error) bool such that Is(target) returns true.

An error type might provide an Is method so it can be treated as equivalent

to an existing error. For example, if MyError defines

func (m MyError) Is(target error) bool { return target == fs.ErrExist }

then Is(MyError{}, fs.ErrExist) returns true. See syscall.Errno.Is for

an example in the standard library. An Is method should only shallowly

compare err and the target and not call Unwrap on either.

func Join

¶

1.20

func Join(errs ...error) error

Join returns an error that wraps the given errors.

Any nil error values are discarded.

Join returns nil if errs contains no non-nil values.

The error formats as the concatenation of the strings obtained

by calling the Error method of each element of errs, with a newline

between each string.

▸ Example

▾ Example

err1 err2 err is err1 err is err2

func New

¶

func New(text string) error

New returns an error that formats as the given text.

Each call to New returns a distinct error value even if the text is identical.

▸ Example

▾ Example

emit macho dwarf: elf header corrupted

▸ Example (Errorf)

▾ Example (Errorf)

The fmt package’s Errorf function lets us use the package’s formatting

features to create descriptive error messages.

user "bimmler" (id 17) not found

func Unwrap

¶

1.13

func Unwrap(err error) error

Unwrap returns the result of calling the Unwrap method on err, if err’s

type contains an Unwrap method returning error.

Otherwise, Unwrap returns nil.

Unwrap returns nil if the Unwrap method returns []error.

Should I use %s or %v to format errors?

TL;DR; Neither. Use %w in 99.99% of cases. In the other 0.001% of cases, %v and %s probably «should» behave the same, except when the error value is nil, but there are no guarantees. The friendlier output of %v for nil errors may be reason to prefer %v (see below).

Now for details:

Use %w instead of %v or %s:

As of Go 1.13 (or earlier if you use golang.org/x/xerrors), you can use the %w verb, only for error values, which wraps the error such that it can later be unwrapped with errors.Unwrap, and so that it can be considered with errors.Is and errors.As.

The only times this is inappropriate:

- You must support an older version of Go, and

xerrorsis not an option. - You want to create a unique error, and not wrap an existing one. This might be appropriate, for instance, if you get a

Not founderror from your database when searching for a user, and want to convert this to anUnauthorizedresponse. In such a case, it’s rare that you’d be using the original error value with any formatting verb, though.

Okay, so what about %v and %s?

The details for how %s and %v are implemented are available in the docs. I’ve highlighted the parts relevant to your question.

If the operand is a reflect.Value, the operand is replaced by the concrete value that it holds, and printing continues with the next rule.

If an operand implements the Formatter interface, it will be invoked. Formatter provides fine control of formatting.

If the %v verb is used with the # flag (%#v) and the operand implements the GoStringer interface, that will be invoked.

If the format (which is implicitly %v for Println etc.) is valid for a string (%s %q %v %x %X), the following two rules apply:

If an operand implements the error interface, the Error method will be invoked to convert the object to a string, which will then be formatted as required by the verb (if any).

If an operand implements method String() string, that method will be invoked to convert the object to a string, which will then be formatted as required by the verb (if any).

To summarize, the fmt.*f functions will:

- Look for a

Format()method, and if it exists, they’ll call it. - Look for a

Error()method, and if it exists, they’ll call it. - Look for a

String()method, and if it exists, call it. - Use some default formatting.

So in practice, this means that %s and %v are identical, except when a Format() method exists on the error type (or when the error is nil). When an error does have a Format() method, one might hope that it would produce the same output with %s, %v, and err.Error(), but since this is up to the implementation of the error, there are no guarantees, and thus no «right answer» here.

And finally, if your error type supports the %+v verb variant, then you will, of course, need to use that, if you desire the detailed output.

nil values

While it’s rare to (intentionally) call fmt.*f on a nil error, the behavior does differ between %s and %v:

%s: %!s(<nil>)

%v: <nil>

Playground link

Привет, хабровчане! Уже сегодня в ОТУС стартует курс «Разработчик Golang» и мы считаем это отличным поводом, чтобы поделиться еще одной полезной публикацией по теме. Сегодня поговорим о подходе Go к ошибкам. Начнем!

Освоение прагматической обработки ошибок в вашем Go-коде

Этот пост является частью серии «Перед тем как приступать к Go», где мы исследуем мир Golang, делимся советами и идеями, которые вы должны знать при написании кода на Go, чтобы вам не пришлось набивать собственные шишки.

Я предполагаю, что у вас уже имеется хотя бы базовый опыт работы с Go, но если вы чувствуете, что в какой-то момент вы столкнулись с незнакомым обсуждаемым материалом, не стесняйтесь делать паузу, исследовать тему и возвращаться.

Теперь, когда мы расчистили себе путь, поехали!

Подход Go к обработке ошибок — одна из самых спорных и неправильно используемых фич. В этой статье вы узнаете подход Go к ошибкам, и поймете, как они работают “под капотом”. Вы изучите несколько различных подходов, рассмотрите исходный код Go и стандартную библиотеку, чтобы узнать, как обрабатываются ошибки и как с ними работать. Вы узнаете, почему утверждения типа (Type Assertions) играют важную роль в их обработке, и увидите предстоящие изменения в обработке ошибок, которые планируется ввести в Go 2.

Вступление

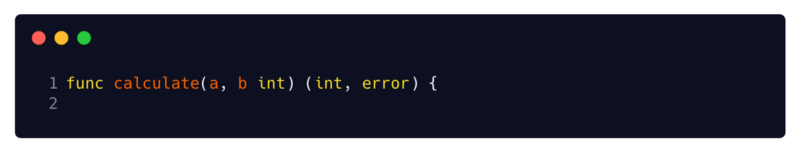

Сперва-наперво: ошибки в Go не являются исключениями. Дэйв Чейни написал эпический блогпост об этом, поэтому я отсылаю вас к нему и резюмирую: на других языках вы не можете быть уверены, может ли функция вызвать исключение или нет. Вместо генерации исключений функции Go поддерживают множественные возвращаемые значения, и по соглашению эта возможность обычно используется для возврата результата функции наряду с переменной ошибки.

Если по какой-то причине ваша функция может дать сбой, вам, вероятно, следует вернуть из нее предварительно объявленный error-тип. По соглашению, возврат ошибки сигнализирует вызывающей стороне о проблеме, а возврат nil не считается ошибкой. Таким образом, вы дадите вызывающему понять, что возникла проблема, и ему нужно разобраться с ней: кто бы ни вызвал вашу функцию, он знает, что не должен полагаться на результат до проверки на наличие ошибки. Если ошибка не nil, он обязан проверить ее и обработать (логировать, возвращать, обслуживать, вызвать какой-либо механизм повторной попытки/очистки и т. д.).

(3 // обработка ошибки

5 // продолжение)

Эти фрагменты очень распространены в Go, и некоторые рассматривают их в качестве шаблонного кода. Компилятор рассматривает неиспользуемые переменные как ошибки компиляции, поэтому, если вы не собираетесь проверять наличие ошибок, вы должны назначить их пустому идентификатору. Но как бы удобно это ни было, ошибки не следует игнорировать.

( 4 // игнорирование ошибок небезопасно, и вы не должны полагаться на результат прежде, чем проверите наличие ошибок)

результату нельзя доверять до проверки на наличие ошибок

Возврат ошибки вместе с результатами, наряду со строгой системой типов Go, значительно усложняет написание забагованного кода. Вы всегда должны полагать, что значение функции повреждено, если только вы не проверили ошибку, которую она возвратила, и, присваивая ошибку пустому идентификатору, вы явно игнорируете, что значение вашей функции может быть повреждено.

Пустой идентификатор темен и полон ужасов.

У Go действительно есть panic и recover механизмы, которые также описаны в другом подробном посте в блоге Go. Но они не предназначены для имитации исключений. По словам Дейва, «Когда вы паникуете в Go — вы действительно паникуете: это не проблема кого-то другого, это уже геймовер». Они фатальны и приводят к сбою в вашей программе. Роб Пайк придумал поговорку «Не паникуйте», которая говорит сама за себя: вам, вероятно, следует избегать эти механизмы и вместо них возвращать ошибки.

«Ошибки — значения».

«Не просто проверяйте наличие ошибок, а элегантно их обрабатывайте»

«Не паникуйте»

все поговорки Роба Пайка

Под капотом

Интерфейс ошибки

Под капотом тип error — это простой интерфейс с одним методом, и если вы с ним не знакомы, я настоятельно рекомендую просмотреть этот пост в официальном блоге Go.

интерфейс error из исходного кода

Свои собственные ошибки реализовать не сложно. Существуют различные подходы к пользовательским структурам, реализующим метод Error() string . Любая структура, реализующая этот единственный метод, считается допустимым значением ошибки и может быть возвращена как таковая.

Давайте рассмотрим несколько таких подходов.

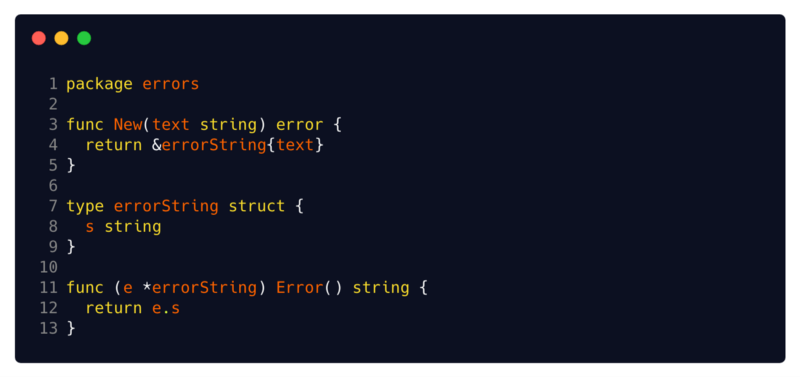

Встроенная структура errorString

Наиболее часто используемая и широко распространенная реализация интерфейса ошибок — это встроенная структура errorString . Это самая простая реализация, о которой вы только можете подумать.

Источник: исходный код Go

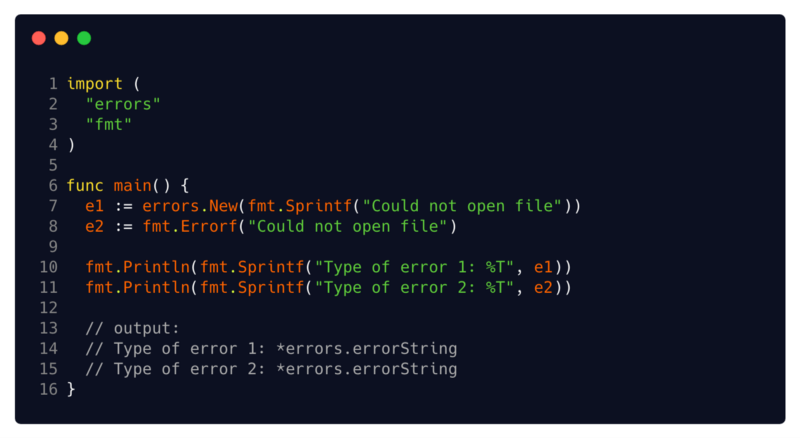

Вы можете лицезреть ее упрощенную реализацию здесь. Все, что она делает, это содержит string, и эта строка возвращается методом Error. Эта стринговая ошибка может быть нами отформатирована на основе некоторых данных, скажем, с помощью fmt.Sprintf. Но кроме этого, она не содержит никаких других возможностей. Если вы применили errors.New или fmt.Errorf, значит вы уже использовали ее.

(13// вывод:)

попробуйте

github.com/pkg/errors

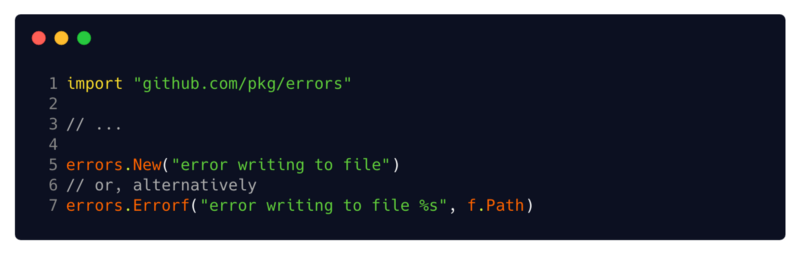

Другой простой пример — пакет pkg/errors. Не путать со встроенным пакетом errors, о котором вы узнали ранее, этот пакет предоставляет дополнительные важные возможности, такие как обертка ошибок, развертка, форматирование и запись стек-трейса. Вы можете установить пакет, запустив go get github.com/pkg/errors.

В тех случаях, когда вам нужно прикрепить стек-трейс или необходимую информацию об отладке к вашим ошибкам, использование функций New или Errorf этого пакета предоставляет ошибки, которые уже записываются в ваш стек-трейс, и вы так же можете прикрепить простые метаданные, используя его возможности форматирования. Errorf реализует интерфейс fmt.Formatter, то есть вы можете отформатировать его, используя руны пакета fmt ( %s, %v, %+v и т. д.).

(//6 или альтернатива)

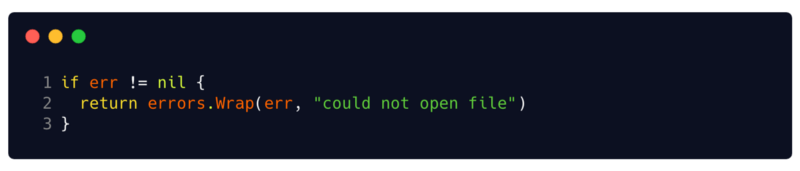

Этот пакет также представляет функции errors.Wrap и errors.Wrapf. Эти функции добавляют контекст к ошибке с помощью сообщения и стек-трейса в том месте, где они были вызваны. Таким образом, вместо простого возврата ошибки, вы можете обернуть ее контекстом и важными отладочными данными.

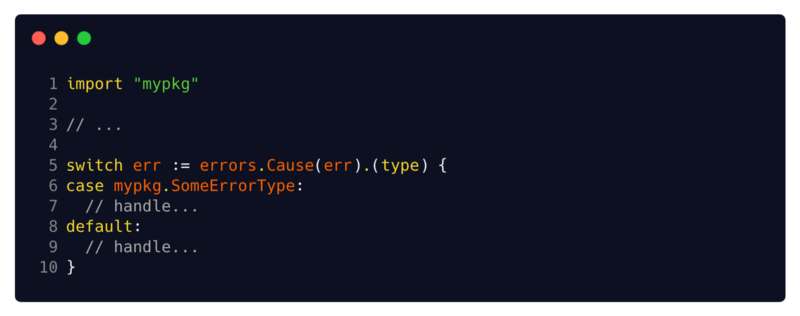

Обертки ошибок другими ошибками поддерживают Cause() error метод, который возвращает их внутреннюю ошибку. Кроме того, они могут использоваться сerrors.Cause(err error) error функцией, которая извлекает основную внутреннюю ошибку в оборачивающей ошибке.

Работа с ошибками

Утверждение типа

Утверждения типа (Type Assertion) играют важную роль при работе с ошибками. Вы будете использовать их для извлечения информации из интерфейсного значения, а поскольку обработка ошибок связана с пользовательскими реализациями интерфейса error, реализация утверждений на ошибках является очень удобным инструментом.

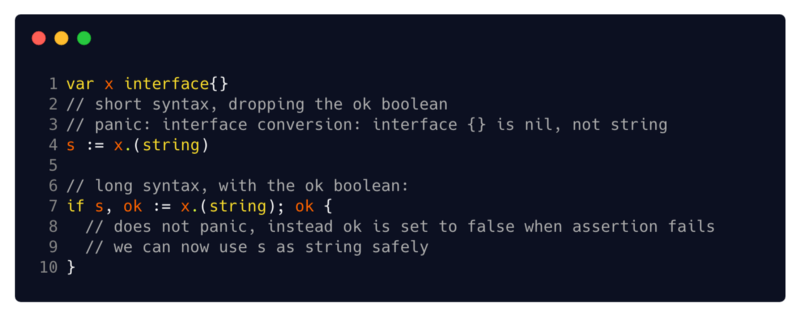

Его синтаксис одинаков для всех его целей — x.(T), если x имеет тип интерфейса. x.(T) утверждает, что x не равен nil и что значение, хранящееся в x, относится к типу T. В следующих нескольких разделах мы рассмотрим два способа использования утверждений типа — с конкретным типом T и с интерфейсом типа T.

(2//сокращенный синтаксис, пропускающий логическую переменную ok

3//паника: преобразование интерфейса: интерфейс {} равен nil, а не string

6//удлиненный синтаксис с логической переменной ok

8//не паникует, вместо этого присваивает ok false, когда утверждение ложно

9// теперь мы можем безопасно использовать s как строку)

песочница: panic при укороченном синтаксисе, безопасный удлинённый синтаксис

Дополнительное примечание, касающееся синтаксиса: утверждение типа может использоваться как с укороченным синтаксисом (который паникует при неудачном утверждении), так и с удлиненным синтаксисом (который использует логическое значение OK для указания успеха или неудачи). Я всегда рекомендую брать удлиненный вместо укороченного, так как я предпочитаю проверять переменную OK, а не разбираться с паникой.

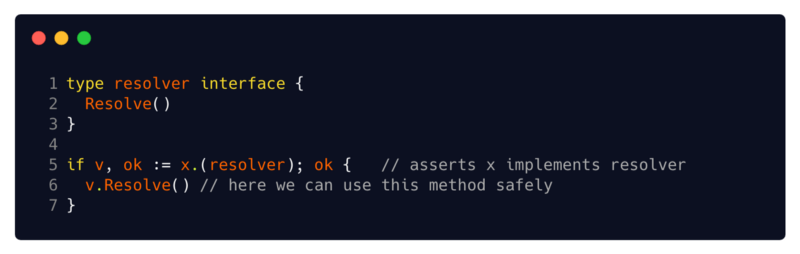

Утверждение с интерфейсом типа T

Выполнение утверждения типа x.(T) с интерфейсом типа T подтверждает, что x реализует интерфейс T. Таким образом, вы можете гарантировать, что интерфейсное значение реализует интерфейс, и только если это так, вы сможете использовать его методы.

(5…// утверждаем, что x реализует интерфейс resolver

6…// здесь мы уже можем безопасно использовать этот метод)

Чтобы понять, как это можно использовать, давайте снова взглянем на pkg/errors. Вы уже знаете этот пакет ошибок, так что давайте углубимся в errors.Cause(err error) error функцию.

Эта функция получает ошибку и извлекает самую внутреннюю ошибку, которую та переносит (ту, которая уже не служит оберткой для другой ошибки). Это может показаться примитивным, но есть много замечательных вещей, которые вы можете извлечь из этой реализации:

источник: pkg/errors

Функция получает значение ошибки, и она не может предполагать, что получаемый ею err аргумент является ошибкой-оберткой (поддерживаемой Cause методом). Поэтому перед вызовом метода Cause необходимо убедиться, что вы имеете дело с ошибкой, которая реализует этот метод. Выполняя утверждение типа в каждой итерации цикла for, вы можете убедиться, что cause переменная поддерживает метод Cause, и может продолжать извлекать из него внутренние ошибки до тех пор, пока не найдете ошибку, у которой нет Cause.

Создавая простой локальный интерфейс, содержащий только те методы, которые вам нужны, и применяя на нем утверждение, ваш код отделен от других зависимостей. Полученный вами аргумент не обязательно должен быть известной структурой, он просто должен быть ошибкой. Любой тип, реализующий методы Error и Cause, подойдет. Таким образом, если вы реализуете Cause метод в своем типе ошибки, вы можете использовать эту функцию с ним без замедлений.

Однако следует помнить об одном небольшом недостатке: интерфейсы могут изменяться, поэтому вам следует тщательно поддерживать код, чтобы ваши утверждения не нарушались. Не забудьте определить свои интерфейсы там, где вы их используете, поддерживать их стройными и аккуратными, и у вас все будет хорошо.

Наконец, если вам нужен только один метод, иногда удобнее сделать утверждение на анонимном интерфейсе, содержащем только метод, на который вы полагаетесь, т. е. v, ok := x.(interface{ F() (int, error) }). Использование анонимных интерфейсов может помочь отделить ваш код от возможных зависимостей и защитить его от возможных изменений в интерфейсах.

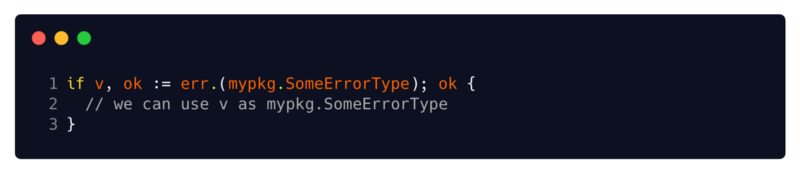

Утверждение с конкретным типом T и Type Switch

Я предваряю этот раздел введением двух похожих шаблонов обработки ошибок, которые страдают от нескольких недостатков и ловушек. Это не значит, что они не распространенные. Оба они могут быть удобными инструментами в небольших проектах, но они плохо масштабируются.

Первый — это второй вариант утверждения типа: выполняется утверждение типа x.(T) с конкретным типом T. Он утверждает, что значение x имеет тип T, или оно может быть преобразовано в тип T.

(2//мы можем использовать v как mypkg.SomeErrorType)

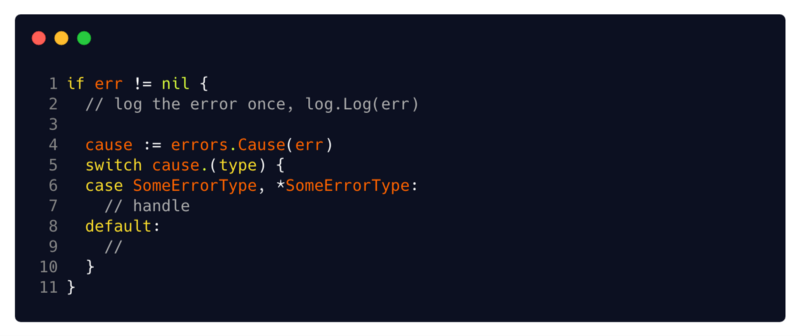

Другой — это шаблон Type Switch. Type Switch объединяют оператор switch с утверждением типа, используя зарезервированное ключевое слово type. Они особенно распространены в обработке ошибок, где знание основного типа переменной ошибки может быть очень полезным.

(3// обработка…

5// обработка…)

Большим недостатком обоих подходов является то, что оба они приводят к связыванию кода со своими зависимостями. Оба примера должны быть знакомы со структурой SomeErrorType (которая, очевидно, должна быть экспортирована) и должны импортировать пакет mypkg.

В обоих подходах при обработке ваших ошибок вы должны быть знакомы с типом и импортировать его пакет. Ситуация усугубляется, когда вы имеете дело с ошибками в обертках, где причиной ошибки может быть ошибка, возникшая из-за внутренней зависимости, о которой вы не знаете и не должны знать.

(7// обработка…

9// обработка…)

Type Switch различают *MyStruct и MyStruct. Поэтому, если вы не уверены, имеете ли вы дело с указателем или фактическим экземпляром структуры, вам придется предоставить оба варианта. Более того, как и в случае с обычными switch, кейсы в Type Switch не проваливаются, но в отличие от обычных Type Switch, использование fallthrough запрещено в Type Switch, поэтому вам придется использовать запятую и предоставлять обе опции, что легко забыть.

Подытожим

Вот и все! Теперь вы знакомы с ошибками и должны быть готовы к устранению любых ошибок, которые ваше приложение Go может выбросить (или фактически вернуть) на ваш путь!

Оба пакета errors представляют простые, но важные подходы к ошибкам в Go, и, если они удовлетворяют вашим потребностям, они являются отличным выбором. Вы можете легко реализовать свои собственные структуры ошибок и пользоваться преимуществами обработки ошибок Go, комбинируя их с pkg/errors.

Когда вы масштабируете простые ошибки, правильное использование утверждений типа может быть отличным инструментом для обработки различных ошибок. Либо с помощью Type Switch, либо путем утверждения поведения ошибки и проверки интерфейсов, которые она реализует.

Что дальше?

Обработка ошибок в Go сейчас очень актуальна. Теперь, когда вы получили основы, вам может быть интересно, что ждет нас в будущем для обработки ошибок Go!

В следующей версии Go 2 этому уделяется много внимания, и вы уже можете взглянуть на черновой вариант. Кроме того, во время dotGo 2019 Марсель ван Лохуизен провел отличную беседу на тему, которую я просто не могу не рекомендовать — «Значения ошибок GO 2 уже сегодня».

Очевидно, есть еще множество подходов, советов и хитростей, и я не могу включить их все в один пост! Несмотря на это, я надеюсь, что вам он понравился, и я увижу вас в следующем выпуске серии «Перед тем как приступать к Go»!

А теперь традиционно ждем ваши комментарии.

Error handling in Go is a little different than other mainstream programming languages like Java, JavaScript, or Python. Go’s built-in errors don’t contain stack traces, nor do they support conventional try/catch methods to handle them. Instead, errors in Go are just values returned by functions, and they can be treated in much the same way as any other datatype — leading to a surprisingly lightweight and simple design.

In this article, I’ll demonstrate the basics of handling errors in Go, as well as some simple strategies you can follow in your code to ensure your program is robust and easy to debug.

The Error Type

The error type in Go is implemented as the following interface:

type error interface {

Error() string

}So basically, an error is anything that implements the Error() method, which returns an error message as a string. It’s that simple!

Constructing Errors

Errors can be constructed on the fly using Go’s built-in errors or fmt packages. For example, the following function uses the errors package to return a new error with a static error message:

package main

import "errors"

func DoSomething() error {

return errors.New("something didn't work")

}Similarly, the fmt package can be used to add dynamic data to the error, such as an int, string, or another error. For example:

package main

import "fmt"

func Divide(a, b int) (int, error) {

if b == 0 {

return 0, fmt.Errorf("can't divide '%d' by zero", a)

}

return a / b, nil

}Note that fmt.Errorf will prove extremely useful when used to wrap another error with the %w format verb — but I’ll get into more detail on that further down in the article.

There are a few other important things to note in the example above.

-

Errors can be returned as

nil, and in fact, it’s the default, or “zero”, value of on error in Go. This is important since checkingif err != nilis the idiomatic way to determine if an error was encountered (replacing thetry/catchstatements you may be familiar with in other programming languages). -

Errors are typically returned as the last argument in a function. Hence in our example above, we return an

intand anerror, in that order. -

When we do return an error, the other arguments returned by the function are typically returned as their default “zero” value. A user of a function may expect that if a non-nil error is returned, then the other arguments returned are not relevant.

-

Lastly, error messages are usually written in lower-case and don’t end in punctuation. Exceptions can be made though, for example when including a proper noun, a function name that begins with a capital letter, etc.

Defining Expected Errors

Another important technique in Go is defining expected Errors so they can be checked for explicitly in other parts of the code. This becomes useful when you need to execute a different branch of code if a certain kind of error is encountered.

Defining Sentinel Errors

Building on the Divide function from earlier, we can improve the error signaling by pre-defining a “Sentinel” error. Calling functions can explicitly check for this error using errors.Is:

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

)

var ErrDivideByZero = errors.New("divide by zero")

func Divide(a, b int) (int, error) {

if b == 0 {

return 0, ErrDivideByZero

}

return a / b, nil

}

func main() {

a, b := 10, 0

result, err := Divide(a, b)

if err != nil {

switch {

case errors.Is(err, ErrDivideByZero):

fmt.Println("divide by zero error")

default:

fmt.Printf("unexpected division error: %sn", err)

}

return

}

fmt.Printf("%d / %d = %dn", a, b, result)

}Defining Custom Error Types

Many error-handling use cases can be covered using the strategy above, however, there can be times when you might want a little more functionality. Perhaps you want an error to carry additional data fields, or maybe the error’s message should populate itself with dynamic values when it’s printed.

You can do that in Go by implementing custom errors type.

Below is a slight rework of the previous example. Notice the new type DivisionError, which implements the Error interface. We can make use of errors.As to check and convert from a standard error to our more specific DivisionError.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

)

type DivisionError struct {

IntA int

IntB int

Msg string

}

func (e *DivisionError) Error() string {

return e.Msg

}

func Divide(a, b int) (int, error) {

if b == 0 {

return 0, &DivisionError{

Msg: fmt.Sprintf("cannot divide '%d' by zero", a),

IntA: a, IntB: b,

}

}

return a / b, nil

}

func main() {

a, b := 10, 0

result, err := Divide(a, b)

if err != nil {

var divErr *DivisionError

switch {

case errors.As(err, &divErr):

fmt.Printf("%d / %d is not mathematically valid: %sn",

divErr.IntA, divErr.IntB, divErr.Error())

default:

fmt.Printf("unexpected division error: %sn", err)

}

return

}

fmt.Printf("%d / %d = %dn", a, b, result)

}Note: when necessary, you can also customize the behavior of the errors.Is and errors.As. See this Go.dev blog for an example.

Another note: errors.Is was added in Go 1.13 and is preferable over checking err == .... More on that below.

Wrapping Errors

In these examples so far, the errors have been created, returned, and handled with a single function call. In other words, the stack of functions involved in “bubbling” up the error is only a single level deep.

Often in real-world programs, there can be many more functions involved — from the function where the error is produced, to where it is eventually handled, and any number of additional functions in-between.

In Go 1.13, several new error APIs were introduced, including errors.Wrap and errors.Unwrap, which are useful in applying additional context to an error as it “bubbles up”, as well as checking for particular error types, regardless of how many times the error has been wrapped.

A bit of history: Before Go 1.13 was released in 2019, the standard library didn’t contain many APIs for working with errors — it was basically just

errors.Newandfmt.Errorf. As such, you may encounter legacy Go programs in the wild that do not implement some of the newer error APIs. Many legacy programs also used 3rd-party error libraries such aspkg/errors. Eventually, a formal proposal was documented in 2018, which suggested many of the features we see today in Go 1.13+.

The Old Way (Before Go 1.13)

It’s easy to see just how useful the new error APIs are in Go 1.13+ by looking at some examples where the old API was limiting.

Let’s consider a simple program that manages a database of users. In this program, we’ll have a few functions involved in the lifecycle of a database error.

For simplicity’s sake, let’s replace what would be a real database with an entirely “fake” database that we import from "example.com/fake/users/db".

Let’s also assume that this fake database already contains some functions for finding and updating user records. And that the user records are defined to be a struct that looks something like:

package db

type User struct {

ID string

Username string

Age int

}

func FindUser(username string) (*User, error) { /* ... */ }

func SetUserAge(user *User, age int) error { /* ... */ }Here’s our example program:

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

"example.com/fake/users/db"

)

func FindUser(username string) (*db.User, error) {

return db.Find(username)

}

func SetUserAge(u *db.User, age int) error {

return db.SetAge(u, age)

}

func FindAndSetUserAge(username string, age int) error {

var user *User

var err error

user, err = FindUser(username)

if err != nil {

return err

}

if err = SetUserAge(user, age); err != nil {

return err

}

return nil

}

func main() {

if err := FindAndSetUserAge("bob@example.com", 21); err != nil {

fmt.Println("failed finding or updating user: %s", err)

return

}

fmt.Println("successfully updated user's age")

}Now, what happens if one of our database operations fails with some malformed request error?

The error check in the main function should catch that and print something like this:

failed finding or updating user: malformed requestBut which of the two database operations produced the error? Unfortunately, we don’t have enough information in our error log to know if it came from FindUser or SetUserAge.

Go 1.13 adds a simple way to add that information.

Errors Are Better Wrapped

The snippet below is refactored so that is uses fmt.Errorf with a %w verb to “wrap” errors as they “bubble up” through the other function calls. This adds the context needed so that it’s possible to deduce which of those database operations failed in the previous example.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

"example.com/fake/users/db"

)

func FindUser(username string) (*db.User, error) {

u, err := db.Find(username)

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("FindUser: failed executing db query: %w", err)

}

return u, nil

}

func SetUserAge(u *db.User, age int) error {

if err := db.SetAge(u, age); err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("SetUserAge: failed executing db update: %w", err)

}

}

func FindAndSetUserAge(username string, age int) error {

var user *User

var err error

user, err = FindUser(username)

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("FindAndSetUserAge: %w", err)

}

if err = SetUserAge(user, age); err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("FindAndSetUserAge: %w", err)

}

return nil

}

func main() {

if err := FindAndSetUserAge("bob@example.com", 21); err != nil {

fmt.Println("failed finding or updating user: %s", err)

return

}

fmt.Println("successfully updated user's age")

}If we re-run the program and encounter the same error, the log should print the following:

failed finding or updating user: FindAndSetUserAge: SetUserAge: failed executing db update: malformed requestNow our message contains enough information that we can see the problem originated in the db.SetUserAge function. Phew! That definitely saved us some time debugging!

If used correctly, error wrapping can provide additional context about the lineage of an error, in ways similar to a traditional stack-trace.

Wrapping also preserves the original error, which means errors.Is and errors.As continue to work, regardless of how many times an error has been wrapped. We can also call errors.Unwrap to return the previous error in the chain.

When To Wrap

Generally, it’s a good idea to wrap an error with at least the function’s name, every time you “bubble it up” — i.e. every time you receive the error from a function and want to continue returning it back up the function chain.

There are some exceptions to the rule, however, where wrapping an error may not be appropriate.

Since wrapping the error always preserves the original error messages, sometimes exposing those underlying issues might be a security, privacy, or even UX concern. In such situations, it could be worth handling the error and returning a new one, rather than wrapping it. This could be the case if you’re writing an open-source library or a REST API where you don’t want the underlying error message to be returned to the 3rd-party user.

While you’re here:

Earthly is the effortless CI/CD framework.

Develop CI/CD pipelines locally and run them anywhere!

Conclusion

That’s a wrap! In summary, here’s the gist of what was covered here:

- Errors in Go are just lightweight pieces of data that implement the

Errorinterface - Predefined errors will improve signaling, allowing us to check which error occurred

- Wrap errors to add enough context to trace through function calls (similar to a stack trace)

I hope you found this guide to effective error handling useful. If you’d like to learn more, I’ve attached some related articles I found interesting during my own journey to robust error handling in Go.

References

- Error handling and Go

- Go 1.13 Errors

- Go Error Doc

- Go By Example: Errors

- Go By Example: Panic

Get notified about new articles!

We won’t send you spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

In this article, we’ll take a look at how to handle errors using build-in Golang functionality, how you can extract information from the errors you are receiving and the best practices to do so.

Error handling in Golang is unconventional when compared to other mainstream languages like Javascript, Java and Python. This can make it very difficult for new programmers to grasp Golangs approach of tackling error handling.

In this article, we’ll take a look at how to handle errors using build-in Golang functionality, how you can extract information from the errors you are receiving and the best practices to do so. A basic understanding of Golang is therefore required to follow this article. If you are unsure about any concepts, you can look them up here.

Errors in Golang

Errors indicate an unwanted condition occurring in your application. Let’s say you want to create a temporary directory where you can store some files for your application, but the directory’s creation fails. This is an unwanted condition and is therefore represented using an error.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"ioutil"

)

func main() {

dir, err := ioutil.TempDir("", "temp")

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("failed to create temp dir: %v", err)

}

}

Golang represents errors using the built-in error type, which we will look at closer in the next section. The error is often returned as a second argument of the function, as shown in the example above. Here the TempDir function returns the name of the directory as well as an error variable.

Creating custom errors

As already mentioned errors are represented using the built-in error interface type, which has the following definition:

type error interface {

Error() string

}

The interface contains a single method Error() that returns an error message as a string. Every type that implements the error interface can be used as an error. When printing the error using methods like fmt.Println the Error() method is automatically called by Golang.

There are multiple ways of creating custom error messages in Golang, each with its own advantages and disadvantages.

String-based errors

String-based errors can be created using two out-of-the-box options in Golang and are used for simple errors that just need to return an error message.

err := errors.New("math: divided by zero")

The errors.New() method can be used to create new errors and takes the error message as its only parameter.

err2 := fmt.Errorf("math: %g cannot be divided by zero", x)

fmt.Errorf on the other hand also provides the ability to add formatting to your error message. Above you can see that a parameter can be passed which will be included in the error message.

Custom error with data

You can create your own error type by implementing the Error() function defined in the error interface on your struct. Here is an example:

type PathError struct {

Path string

}

func (e *PathError) Error() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("error in path: %v", e.Path)

}

The PathError implements the Error() function and therefore satisfies the error interface. The implementation of the Error() function now returns a string with the path of the PathError struct. You can now use PathError whenever you want to throw an error.

Here is an elementary example:

package main

import(

"fmt"

)

type PathError struct {

Path string

}

func (e *PathError) Error() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("error in path: %v", e.Path)

}

func throwError() error {

return &PathError{Path: "/test"}

}

func main() {

err := throwError()

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

}

}

You can also check if the error has a specific type using either an if or switch statement:

if err != nil {

switch e := err.(type) {

case *PathError :

// Do something with the path

default:

log.Println(e)

}

}

This will allow you to extract more information from your errors because you can then call all functions that are implemented on the specific error type. For example, if the PathError had a second method called GetInfo you could call it like this.

e.GetInfo()

Error handling in functions

Now that you know how to create your own custom errors and extract as much information as possible from errors let’s take a look at how you can handle errors in functions.

Most of the time errors are not directly handled in functions but are returned as a return value instead. Here we can take advantage of the fact that Golang supports multiple return values for a function. Thus you can return your error alongside the normal result — errors are always returned as the last argument — of the function as follows:

func divide(a, b float64) (float64, error) {

if b == 0 {

return 0.0, errors.New("cannot divide through zero")

}

return a/b, nil

}

The function call will then look similar to this:

func main() {

num, err := divide(100, 0)

if err != nil {

fmt.Printf("error: %s", err.Error())

} else {

fmt.Println("Number: ", num)

}

}

If the returned error is not nil it usually means that there is a problem and you need to handle the error appropriately. This can mean that you use some kind of log message to warn the user, retry the function until it works or close the application entirely depending on the situation. The only drawback is that Golang does not enforce handling the retuned errors, which means that you could just ignore handling errors completely.

Take the following code for example:

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

)

func main() {

num2, _ := divide(100, 0)

fmt.Println("Number: ", num2)

}

The so-called blank identifier is used as an anonymous placeholder and therefore provides a way to ignore values in an assignment and avoid compiler errors in the process. But remember that using the blank identifier instead of probably handling errors is dangerous and should not be done if it can be avoided.

Defer, panic and recover

Go does not have exceptions like many other programming languages, including Java and Javascript but has a comparable mechanism know as ,,Defer, panic and recover». Still the use-cases of panic and recover are very different from exceptions in other programming languages as they should only be used in unexpected and unrecoverable situations.

Defer

A defer statement is a mechanism used to defer a function by putting it into an executed stack once the function that contains the defer statement has finished, either normally by executing a return statement or abnormally panicking. Deferred functions will then be executed in reverse order in which they were deferred.

Take the following function for example:

func processHTML(url string) error {

resp, err := http.Get(url)

if err != nil {

return err

}

ct := resp.Header.Get("Content-Type")

if ct != "text/html" && !strings.HasPrefix(ct, "text/html;") {

resp.Body.Close()

return fmt.Errorf("%s has content type %s which does not match text/html", url, ct)

}

doc, err := html.Parse(resp.Body)

resp.Body.Close()

// ... Process HTML ...

return nil

}

Here you can notice the duplicated resp.Body.Close call, which ensures that the response is properly closed. Once functions grow more complex and have more errors that need to be handled such duplications get more and more problematic to maintain.

Since deferred calls get called once the function has ended, no matter if it succeeded or not it can be used to simplify such calls.

func processHTMLDefer(url string) error {

resp, err := http.Get(url)

if err != nil {

return err

}

defer resp.Body.Close()

ct := resp.Header.Get("Content-Type")

if ct != "text/html" && !strings.HasPrefix(ct, "text/html;") {

return fmt.Errorf("%s has content type %s which does not match text/html", url, ct)

}

doc, err := html.Parse(resp.Body)

// ... Process HTML ...

return nil

}

All deferred functions are executed in reverse order in which they were deferred when the function finishes.

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func main() {

first()

}

func first() {

defer fmt.Println("first")

second()

}

func second() {

defer fmt.Println("second")

third()

}

func third() {

defer fmt.Println("third")

}

Here is the result of running the above program:

third

second

first

Panic

A panic statement signals Golang that your code cannot solve the current problem and it therefore stops the normal execution flow of your code. Once a panic is called, all deferred functions are executed and the program crashes with a log message that includes the panic values (usually an error message) and a stack trace.

As an example Golang will panic when a number is divided by zero.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

divide(5)

}

func divide(x int) {

fmt.Printf("divide(%d) n", x+0/x)

divide(x-1)

}

Once the divide function is called using zero, the program will panic, resulting in the following output.

panic: runtime error: integer divide by zero

goroutine 1 [running]:

main.divide(0x0)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:16 +0xe6

main.divide(0x1)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:17 +0xd6

main.divide(0x2)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:17 +0xd6

main.divide(0x3)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:17 +0xd6

main.divide(0x4)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:17 +0xd6

main.divide(0x5)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:17 +0xd6

main.main()

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:11 +0x31

exit status 2

You can also use the built-in panic function to panic in your own programms. A panic should mostly only be used when something happens that the program didn’t expect and cannot handle.

func getArguments() {

if len(os.Args) == 1 {

panic("Not enough arguments!")

}

}

As already mentioned, deferred functions will be executed before terminating the application, as shown in the following example.

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func main() {

accessSlice([]int{1,2,5,6,7,8}, 0)

}

func accessSlice(slice []int, index int) {

fmt.Printf("item %d, value %d n", index, slice[index])

defer fmt.Printf("defer %d n", index)

accessSlice(slice, index+1)

}

Here is the output of the programm:

item 0, value 1

item 1, value 2

item 2, value 5

item 3, value 6

item 4, value 7

item 5, value 8

defer 5

defer 4

defer 3

defer 2

defer 1

defer 0

panic: runtime error: index out of range [6] with length 6

goroutine 1 [running]:

main.accessSlice(0xc00011df48, 0x6, 0x6, 0x6)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:29 +0x250

main.accessSlice(0xc00011df48, 0x6, 0x6, 0x5)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:31 +0x1eb

main.accessSlice(0xc00011df48, 0x6, 0x6, 0x4)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:31 +0x1eb

main.accessSlice(0xc00011df48, 0x6, 0x6, 0x3)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:31 +0x1eb

main.accessSlice(0xc00011df48, 0x6, 0x6, 0x2)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:31 +0x1eb

main.accessSlice(0xc00011df48, 0x6, 0x6, 0x1)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:31 +0x1eb

main.accessSlice(0xc00011df48, 0x6, 0x6, 0x0)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:31 +0x1eb

main.main()

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:9 +0x99

exit status 2

Recover

In some rare cases panics should not terminate the application but be recovered instead. For example, a socket server that encounters an unexpected problem could report the error to the clients and then close all connections rather than leaving the clients wondering what just happened.

Panics can therefore be recovered by calling the built-in recover function within a deferred function in the function that is panicking. Recover will then end the current state of panic and return the panic error value.

package main

import "fmt"

func main(){

accessSlice([]int{1,2,5,6,7,8}, 0)

}

func accessSlice(slice []int, index int) {

defer func() {

if p := recover(); p != nil {

fmt.Printf("internal error: %v", p)

}

}()

fmt.Printf("item %d, value %d n", index, slice[index])

defer fmt.Printf("defer %d n", index)

accessSlice(slice, index+1)

}

As you can see after adding a recover function to the function we coded above the program doesn’t exit anymore when the index is out of bounds by recovers instead.

Output:

item 0, value 1

item 1, value 2

item 2, value 5

item 3, value 6

item 4, value 7

item 5, value 8

internal error: runtime error: index out of range [6] with length 6defer 5

defer 4

defer 3

defer 2

defer 1

defer 0

Recovering from panics can be useful in some cases, but as a general rule you should try to avoid recovering from panics.

Error wrapping

Golang also allows errors to wrap other errors which provides the functionality to provide additional context to your error messages. This is often used to provide specific information like where the error originated in your program.

You can create wrapped errors by using the %w flag with the fmt.Errorf function as shown in the following example.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

"os"

)

func main() {

err := openFile("non-existing")

if err != nil {

fmt.Printf("error running program: %s n", err.Error())

}

}

func openFile(filename string) error {

if _, err := os.Open(filename); err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("error opening %s: %w", filename, err)

}

return nil

}

The output of the application would now look like the following:

error running program: error opening non-existing: open non-existing: no such file or directory

As you can see the application prints both the new error created using fmt.Errorf as well as the old error message that was passed to the %w flag. Golang also provides the functionality to get the old error message back by unwrapping the error using errors.Unwrap.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

"os"

)

func main() {

err := openFile("non-existing")

if err != nil {

fmt.Printf("error running program: %s n", err.Error())

// Unwrap error

unwrappedErr := errors.Unwrap(err)

fmt.Printf("unwrapped error: %v n", unwrappedErr)

}

}

func openFile(filename string) error {

if _, err := os.Open(filename); err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("error opening %s: %w", filename, err)

}

return nil

}

As you can see the output now also displays the original error.

error running program: error opening non-existing: open non-existing: no such file or directory

unwrapped error: open non-existing: no such file or directory

Errors can be wrapped and unwrapped multiple times, but in most cases wrapping them more than a few times does not make sense.

Casting Errors

Sometimes you will need a way to cast between different error types to for example, access unique information that only that type has. The errors.As function provides an easy and safe way to do so by looking for the first error in the error chain that fits the requirements of the error type. If no match is found the function returns false.

Let’s look at the official errors.As docs example to better understand what is happening.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

"io/fs"

"os"

)

func main(){

// Casting error

if _, err := os.Open("non-existing"); err != nil {

var pathError *os.PathError

if errors.As(err, &pathError) {

fmt.Println("Failed at path:", pathError.Path)

} else {

fmt.Println(err)

}

}

}

Here we try to cast our generic error type to os.PathError so we can access the Path variable that that specific error contains.

Another useful functionality is checking if an error has a specific type. Golang provides the errors.Is function to do exactly that. Here you provide your error as well as the particular error type you want to check. If the error matches the specific type the function will return true, if not it will return false.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

"io/fs"

"os"

)

func main(){

// Check if error is a specific type

if _, err := os.Open("non-existing"); err != nil {

if errors.Is(err, fs.ErrNotExist) {

fmt.Println("file does not exist")

} else {

fmt.Println(err)

}

}

}

After checking, you can adapt your error message accordingly.

Sources

- Golang Blog — Working with Errors in Go 1.13

- The Go Programming language book

- Golang Blog — Defer, Panic, and Recover

- LogRocket — Error handling in Golang

- GolangByExample — Wrapping and Un-wrapping of error in Go

- Golang Documentation — Package errors

Conclusion

You made it all the way until the end! I hope this article helped you understand the basics of Go error handling and why it is an essential topic in application/software development.

If you have found this helpful, please consider recommending and sharing it with other fellow developers and subscribing to my newsletter. If you have any questions or feedback, let me know using my contact form or contact me on Twitter.

Обработка ошибок Go как значений хорошо послужила за последнее десятилетие. Хотя поддержка ошибок в стандартной библиотеке была минимальной — только функции errors.New и fmt.Errorf, которые выдают ошибки, содержащие только сообщение, — встроенный интерфейс error позволяет программистам Go добавлять любую информацию, которую они пожелают. Все, что требуется, это тип, который реализует метод Error:

type QueryError struct {

Query string

Err error

}

func (e *QueryError) Error() string {

return e.Query + ": " + e.Err.Error()

}

Типы ошибок, подобные этому, встречаются повсеместно, и информация, которую они хранят, варьируется в широких пределах, от временных меток до имен файлов и адресов серверов. Часто эта информация включает в себя еще одну ошибку более низкого уровня для обеспечения дополнительного контекста.

Шаблон одной ошибки, содержащей другую, настолько распространен в коде Go, что после всестороннего обсуждения в Go 1.13 добавлена явная поддержка. В этом посте описываются дополнения к стандартной библиотеке, обеспечивающие эту поддержку: три новые функции в пакете errors и новый глагол форматирования для fmt.Errorf.

Перед подробным описанием изменений рассмотрим, как ошибки анализируются и конструируются в предыдущих версиях языка.

Ошибки до Go 1.13

Проверки ошибок

Ошибки в Go являются значениями. Программы принимают решения на основе этих значений несколькими способами. Наиболее распространенным является сравнение ошибки с nil, чтобы увидеть, не потерпела ли операция неудачу.

if err != nil {

// что-то пошло не так

}

Иногда мы сравниваем ошибку с известным сторожевым значением, чтобы увидеть, произошла ли конкретная ошибка.

var ErrNotFound = errors.New("not found")

if err == ErrNotFound {

// что-то не найдено

}

Значение ошибки может быть любого типа, который удовлетворяет определенному в языке интерфейсу error. Программа может использовать утверждение типа или переключатель типа для просмотра значения ошибки как более определенного типа.

type NotFoundError struct {

Name string

}

func (e *NotFoundError) Error() string {

return e.Name + ": not found"

}

if e, ok := err.(*NotFoundError); ok {

// e.Name не найдено

}

Добавление информации

Часто функция передает ошибку в стек вызовов при добавлении в нее информации, например, краткое описание того, что происходило, когда произошла ошибка. Простой способ сделать это — создать новую ошибку, которая включает в себя текст предыдущего сообщения:

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("decompress %v: %v", name, err)

}

Создание новой ошибки с помощью fmt.Errorf удаляет все из исходной ошибки, кроме текста. Как мы видели выше с QueryError, иногда мы можем захотеть определить новый тип ошибки, который содержит основную ошибку, сохранив ее для проверки кодом. Опять QueryError:

type QueryError struct {

Query string

Err error

}

Программы могут заглянуть внутрь значения *QueryError, чтобы принимать решения на основе подлежащей ошибки. Иногда вы встретите, что это называется «разворачиванием» («unwrapping») ошибки.

if e, ok := err.(*QueryError); ok && e.Err == ErrPermission {

// запрос не выполнен из-за проблем с правами доступа

}

Тип os.PathError в стандартной библиотеке является одним из примеров ошибки, которая содержит другую.

Ошибки в Go 1.13

Метод Unwrap

Go 1.13 представляет новые функции для errors и fmt пакетов стандартной библиотеки для упрощения работы с ошибками, которые содержат другие ошибки. Наиболее важным из них является соглашение, а не изменение: ошибка, которая содержит другую ошибку, может реализовать метод Unwrap, возвращающий основную ошибку. Если e1.Unwrap() возвращает e2, то мы говорим, что e1 оборачивает e2 (e1 wraps e2), и вы можете развернуть e1 (unwrap e1), чтобы получить e2.

Следуя этому соглашению, мы можем задать типу QueryError метод Unwrap, который возвращает содержащуюся в QueryError ошибку:

func (e *QueryError) Unwrap() error { return e.Err }

Результат развертывания ошибки может сам по себе иметь метод Unwrap; это названо последовательностью ошибок, вызванных повторным развертыванием цепочки ошибок.

Проверка ошибок с Is и As

Пакет errors в Go 1.13 включает две новые функции для проверки ошибок: Is и As.

Функция errors.Is сравнивает ошибку со значением.

// Похоже на:

// if err == ErrNotFound { … }

if errors.Is(err, ErrNotFound) {

// что-то не найдено

}

Функция As проверяет, является ли ошибка определенным типом.

// Похоже на:

// if e, ok := err.(*QueryError); ok { … }

var e *QueryError

if errors.As(err, &e) {

// err является *QueryError,

// а в e устанавливается значение ошибки

}

В простейшем случае функция errors.Is ведет себя как сравнение с дозорной ошибкой, а error.As действует как утверждение типа. Однако при работе с обернутыми ошибками эти функции учитывают все ошибки в цепочке. Еще раз посмотрим на приведенный выше пример развертывания QueryError, чтобы изучить основную ошибку:

if e, ok := err.(*QueryError); ok && e.Err == ErrPermission {

// запрос не выполнен из-за проблем с правами доступа

}

Используя функцию errors.Is, мы можем записать это как:

if errors.Is(err, ErrPermission) {

// err, или какая-то ошибка, которую она содержит,

// является ошибкой прав доступа

}

Пакет errors также включает новую функцию Unwrap, которая возвращает результат вызова метода Unwrap ошибки или nil, если у ошибки нет метода Unwrap. Обычно лучше использовать errors.Is или errors.As, поскольку эти функции будут проверять всю цепочку за один вызов.

Оборачивание ошибок с %w

Как упоминалось ранее, обычно используется функция fmt.Errorf для добавления дополнительной информации об ошибке.

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("decompress %v: %v", name, err)

}

В Go 1.13 функция fmt.Errorf поддерживает новый глагол %w. Когда этот глагол присутствует, ошибка, возвращаемая fmt.Errorf, будет иметь метод Unwrap, возвращающий аргумент %w, который должен быть ошибкой. В остальном, %w идентичен %v.

if err != nil {

// Возвращаем ошибку, которая разворачивается в err.

return fmt.Errorf("decompress %v: %w", name, err)

}

Оборачивание ошибки с %w делает ее доступной для errors.Is и errors.As:

err := fmt.Errorf("access denied: %w”, ErrPermission)

...

if errors.Is(err, ErrPermission) ...

Оборачивать ли ошибки?

При добавлении дополнительного контекста к ошибке, либо с помощью fmt.Errorf, либо путем реализации пользовательского типа, вам необходимо решить, должна ли новая ошибка оборачивать оригинал. На этот вопрос нет однозначного ответа; это зависит от контекста, в котором создается новая ошибка. Оберните ошибку, чтобы показать ее вызывающей стороне. Не оборачивайте ошибку, если это приведет к раскрытию деталей реализации.

В качестве примера представим функцию Parse, которая считывает сложную структуру данных из io.Reader. Если возникает ошибка, мы хотим сообщить номер строки и столбца, на котором она произошла. Если ошибка возникает при чтении из io.Reader, мы хотим обернуть эту ошибку, чтобы разрешить проверку основной проблемы. Так как вызывающая сторона предоставила функции io.Reader, имеет смысл показать ошибку, вызванную ею.

Напротив, функция, которая делает несколько обращений к базе данных, вероятно, не должна возвращать ошибку, которая разворачивается в результате одного из этих вызовов. Если база данных, используемая функцией, является деталью реализации, то раскрытие этих ошибок является нарушением абстракции. Например, если функция LookupUser вашего пакета pkg использует пакет Go database/sql, то может возникнуть ошибка sql.ErrNoRows. Если вы вернете эту ошибку с помощью fmt.Errorf(«accessing DB: %v», err), то вызывающая сторона не сможет заглянуть внутрь, чтобы найти sql.ErrNoRows. Но если функция вместо этого возвращает fmt.Errorf(«accessing DB: %w», err), то вызывающая сторона может разумно написать

err := pkg.LookupUser(...)

if errors.Is(err, sql.ErrNoRows) …

На этом этапе функция всегда должна возвращать sql.ErrNoRows, если вы не хотите ломать своих клиентов, даже если вы переключаетесь на другой пакет базы данных. Другими словами, оборачивание ошибки делает эту ошибку частью вашего API. Если вы не хотите поддерживать эту ошибку как часть вашего API в будущем, вам не следует оборачивать ошибку.

Важно помнить, что независимо от того, оборачиваете вы или нет, текст ошибки будет одинаковым. Человек, пытающийся понять ошибку, будет иметь ту же информацию в любом случае; выбор заключается в том, предоставлять ли программам дополнительную информацию, чтобы они могли принимать более обоснованные решения, или скрывать эту информацию для сохранения уровня абстракции.

Настройка тестов ошибок с помощью методов Is и As

Функция errors.Is проверяет каждую ошибку в цепочке на соответствие целевому значению. По умолчанию ошибка соответствует цели, если они равны. Кроме того, ошибка в цепочке может объявить, что она соответствует цели путем реализации метода Is.

В качестве примера рассмотрим следующую ошибку, вдохновленную пакетом ошибок Upspin, который сравнивает ошибку с шаблоном, рассматривая только поля, отличные от нуля в шаблоне:

type Error struct {

Path string

User string

}

func (e *Error) Is(target error) bool {

t, ok := target.(*Error)

if !ok {

return false

}

return (e.Path == t.Path || t.Path == "") &&

(e.User == t.User || t.User == "")

}

if errors.Is(err, &Error{User: "someuser"}) {

// поле User в err равно "someuser".

}

Функция errors.As аналогично обращается к методу As при его наличии.

Ошибки и пакеты API

Пакет, который возвращает ошибки (а большинство возвращает) должен описывать, на какие свойства этих ошибок могут положиться программисты. Хорошо разработанный пакет также позволит избежать возврата ошибок со свойствами, на которые нельзя полагаться.

Самая простая спецификация состоит в том, чтобы сказать, что операции либо завершаются успешно, либо завершаются неудачей, возвращая нулевую или ненулевую ошибку соответственно. Во многих случаях дополнительная информация не требуется.

Если мы хотим, чтобы функция возвращала идентифицируемое условие ошибки, такое как «item not found», мы могли бы вернуть ошибку, оборачивающую дозорную ошибку.

var ErrNotFound = errors.New("not found")

// FetchItem возвращает именованный элемент.

//

// Если элемент с таким именем не существует,

// FetchItem возвращает ошибку оборачивающую ErrNotFound.

func FetchItem(name string) (*Item, error) {

if itemNotFound(name) {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("%q: %w", name, ErrNotFound)

}

// ...

}

Существуют и другие паттерны для предоставления ошибок, которые могут быть семантически проверены вызывающей стороной, такие как прямой возврат значения дозорной ошибки, определенного типа или значения, которое можно проверить с помощью predicate функции.

Во всех случаях следует соблюдать осторожность, чтобы не раскрывать внутренние детали пользователю. Как мы уже говорили в разделе «Оборачивать ли ошибку» выше, когда вы возвращаете ошибку из другого пакета, вы должны преобразовать ошибку в форму, которая не раскрывает основную ошибку, если только вы не захотите вернуть эту конкретную ошибку в будущем.

f, err := os.Open(filename)

if err != nil {

// *os.PathError возвращенная от os.Open

// это внутренняя деталь. Чтобы не показывать ее

// вызывающей стороне, упакем ее как новую ошибку

// с тем же текстом.

// Используем глагол форматирования %v, так как

// %w позволит вызывающей стороне

// развернуть исходную *os.PathError.

return fmt.Errorf("%v", err)

}

Если функция определена как возвращающая ошибку, заключающую в себе какую-то дозорную ошибку или тип, не возвращайте основную ошибку напрямую.

var ErrPermission = errors.New("permission denied")

// DoSomething возвращает ошибку,

// оборачивающую ErrPermission, если пользователь

// не имеет прав доступа к чему-либо.

func DoSomething() {

if !userHasPermission() {

// Если возвращаем ErrPermission напрямую,

// вызывающая сторона может прийти

// к зависимости от точного значения ошибки,

// написав подобный код:

//

// if err := pkg.DoSomething(); err == pkg.ErrPermission { … }

//

// Это может вызвать проблемы

// если мы хотим добавить дополнительный

// контекст к ошибке в будущем.

// Чтобы избежать этого возвращаем ошибку,

// оборачивающую дозорную ошибку,

// так что пользователи всегда

// должны развернуть ее:

//

// if err := pkg.DoSomething(); errors.Is(err, pkg.ErrPermission) { ... }

return fmt.Errorf("%w", ErrPermission)

}

// ...

}

Заключение

Несмотря на то, что обсуждаемые изменения касаются только трех функций и глагола форматирования, ожидается, что они значительно улучшат способ обработки ошибок в программах Go. Ожидается, что оборачивание для обеспечения дополнительного контекста станет обычным явлением, помогая программам принимать лучшие решения и помогая программистам быстрее находить ошибки.

Читайте также:

- Основы Go: ошибки

- Эффективный Go: ошибки

- Go 1.13 заметки о релизе

Recently, I was working on a project which required to handle custom errors in golang. unlike other language, golang does explicit error checking.

An error is just a value that a function can return if something unexpected happened.

In golang, errors are values which return errors as normal return value then we handle errors like if err != nil compare to other conventional try/catch method in another language.

Error in Golang

type error interface {

Error() string

}

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

In Go, The error built-in interface type is the conventional interface for representing an error condition, with the nil value representing no error.

It has single Error() method which returns the error message as a string. By implementing this method, we can transform any type we define into an error of our own.

package main

import (

"io/ioutil"

"log"

)

func getFileContent(filename string) ([]byte, error) {

content, err := ioutil.ReadFile(filename)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return content, nil

}

func main() {

content, err := getFileContent("filename.txt")

if err != nil {

log.SetFlags(0)

log.Fatal(err)

}

log.Println(string(content))

}

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

An idiomatic way to handle errors in Go is to return it as the last return value of the function and check for the nil condition.

Creating errors in go

error is an interface type

Golang provides two ways to create errors in standard library using errors.New and fmt.ErrorF.

errors.New

errors.New("new error")

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Go provides the built-in errors package which exports the New function. This function expects an error text message and returns an error.

The returned error can be treated as a string by either accessing err.Error(), or using any of the fmt package functions. Error() method is automatically called by Golang when printing the error using methods like fmt.Println.

var (

ErrNotFound1 = errors.New("not found")

ErrNotFound2 = errors.New("not found")

)

func main() {

fmt.Printf("is identical? : %t", ErrNotFound1 == ErrNotFound2)

}

// Output:

// is identical? : false

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Each call to New, returns a distinct error value even if the text is identical.

func New(text string) error {

return &errorString{text}

}

type errorString struct {

s string

}

func (e *errorString) Error() string {

return e.s

}

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Internally, errors.New creates and returns a pointer to errors.errorString struct invoked with the string passed which implements the error interface.

fmt.ErrorF

number := 100

zero := 0

fmt.Errorf("math: %d cannot be divided by %d", number, zero)

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

fmt.Errorf provides ability to format your error message using format specifier and returns the string as a

value that satisfies error interface.

Custom errors with data in go

As mentioned above, error is an interface type.

Hence, you can create your own error type by implementing the Error() function defined in the error interface on your struct.

So, let’s create our first custom error by implementing error interface.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"os"

)

type MyError struct {

Code int

Msg string

}

func (m *MyError) Error() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("%s: %d", m.Msg, m.Code)

}

func sayHello(name string) (string, error) {

if name == "" {