Привет, хабровчане! Уже сегодня в ОТУС стартует курс «Разработчик Golang» и мы считаем это отличным поводом, чтобы поделиться еще одной полезной публикацией по теме. Сегодня поговорим о подходе Go к ошибкам. Начнем!

Освоение прагматической обработки ошибок в вашем Go-коде

Этот пост является частью серии «Перед тем как приступать к Go», где мы исследуем мир Golang, делимся советами и идеями, которые вы должны знать при написании кода на Go, чтобы вам не пришлось набивать собственные шишки.

Я предполагаю, что у вас уже имеется хотя бы базовый опыт работы с Go, но если вы чувствуете, что в какой-то момент вы столкнулись с незнакомым обсуждаемым материалом, не стесняйтесь делать паузу, исследовать тему и возвращаться.

Теперь, когда мы расчистили себе путь, поехали!

Подход Go к обработке ошибок — одна из самых спорных и неправильно используемых фич. В этой статье вы узнаете подход Go к ошибкам, и поймете, как они работают “под капотом”. Вы изучите несколько различных подходов, рассмотрите исходный код Go и стандартную библиотеку, чтобы узнать, как обрабатываются ошибки и как с ними работать. Вы узнаете, почему утверждения типа (Type Assertions) играют важную роль в их обработке, и увидите предстоящие изменения в обработке ошибок, которые планируется ввести в Go 2.

Вступление

Сперва-наперво: ошибки в Go не являются исключениями. Дэйв Чейни написал эпический блогпост об этом, поэтому я отсылаю вас к нему и резюмирую: на других языках вы не можете быть уверены, может ли функция вызвать исключение или нет. Вместо генерации исключений функции Go поддерживают множественные возвращаемые значения, и по соглашению эта возможность обычно используется для возврата результата функции наряду с переменной ошибки.

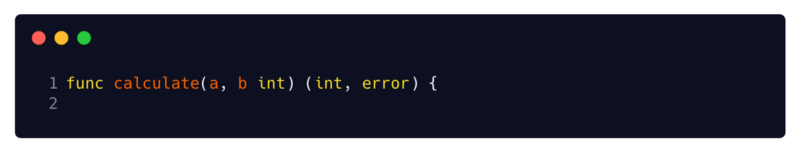

Если по какой-то причине ваша функция может дать сбой, вам, вероятно, следует вернуть из нее предварительно объявленный error-тип. По соглашению, возврат ошибки сигнализирует вызывающей стороне о проблеме, а возврат nil не считается ошибкой. Таким образом, вы дадите вызывающему понять, что возникла проблема, и ему нужно разобраться с ней: кто бы ни вызвал вашу функцию, он знает, что не должен полагаться на результат до проверки на наличие ошибки. Если ошибка не nil, он обязан проверить ее и обработать (логировать, возвращать, обслуживать, вызвать какой-либо механизм повторной попытки/очистки и т. д.).

(3 // обработка ошибки

5 // продолжение)

Эти фрагменты очень распространены в Go, и некоторые рассматривают их в качестве шаблонного кода. Компилятор рассматривает неиспользуемые переменные как ошибки компиляции, поэтому, если вы не собираетесь проверять наличие ошибок, вы должны назначить их пустому идентификатору. Но как бы удобно это ни было, ошибки не следует игнорировать.

( 4 // игнорирование ошибок небезопасно, и вы не должны полагаться на результат прежде, чем проверите наличие ошибок)

результату нельзя доверять до проверки на наличие ошибок

Возврат ошибки вместе с результатами, наряду со строгой системой типов Go, значительно усложняет написание забагованного кода. Вы всегда должны полагать, что значение функции повреждено, если только вы не проверили ошибку, которую она возвратила, и, присваивая ошибку пустому идентификатору, вы явно игнорируете, что значение вашей функции может быть повреждено.

Пустой идентификатор темен и полон ужасов.

У Go действительно есть panic и recover механизмы, которые также описаны в другом подробном посте в блоге Go. Но они не предназначены для имитации исключений. По словам Дейва, «Когда вы паникуете в Go — вы действительно паникуете: это не проблема кого-то другого, это уже геймовер». Они фатальны и приводят к сбою в вашей программе. Роб Пайк придумал поговорку «Не паникуйте», которая говорит сама за себя: вам, вероятно, следует избегать эти механизмы и вместо них возвращать ошибки.

«Ошибки — значения».

«Не просто проверяйте наличие ошибок, а элегантно их обрабатывайте»

«Не паникуйте»

все поговорки Роба Пайка

Под капотом

Интерфейс ошибки

Под капотом тип error — это простой интерфейс с одним методом, и если вы с ним не знакомы, я настоятельно рекомендую просмотреть этот пост в официальном блоге Go.

интерфейс error из исходного кода

Свои собственные ошибки реализовать не сложно. Существуют различные подходы к пользовательским структурам, реализующим метод Error() string . Любая структура, реализующая этот единственный метод, считается допустимым значением ошибки и может быть возвращена как таковая.

Давайте рассмотрим несколько таких подходов.

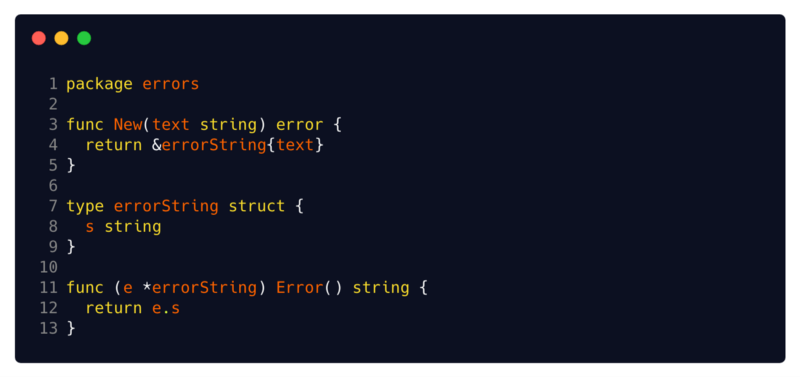

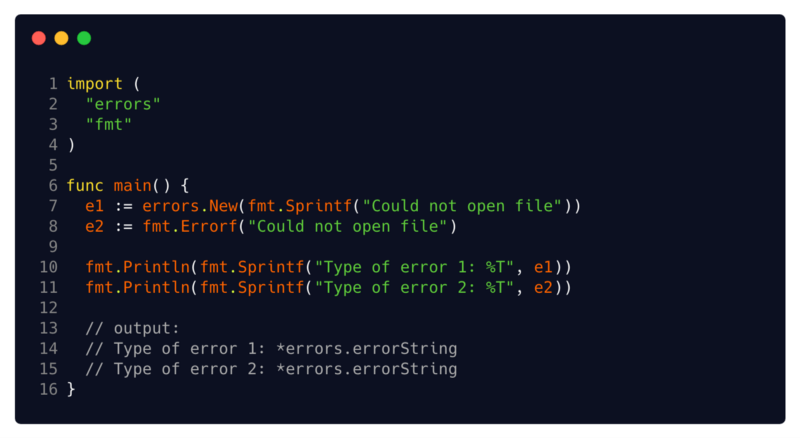

Встроенная структура errorString

Наиболее часто используемая и широко распространенная реализация интерфейса ошибок — это встроенная структура errorString . Это самая простая реализация, о которой вы только можете подумать.

Источник: исходный код Go

Вы можете лицезреть ее упрощенную реализацию здесь. Все, что она делает, это содержит string, и эта строка возвращается методом Error. Эта стринговая ошибка может быть нами отформатирована на основе некоторых данных, скажем, с помощью fmt.Sprintf. Но кроме этого, она не содержит никаких других возможностей. Если вы применили errors.New или fmt.Errorf, значит вы уже использовали ее.

(13// вывод:)

попробуйте

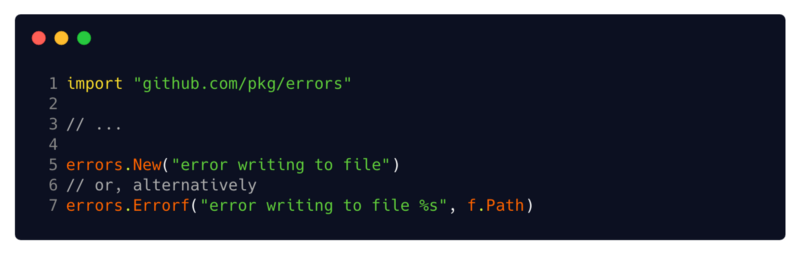

github.com/pkg/errors

Другой простой пример — пакет pkg/errors. Не путать со встроенным пакетом errors, о котором вы узнали ранее, этот пакет предоставляет дополнительные важные возможности, такие как обертка ошибок, развертка, форматирование и запись стек-трейса. Вы можете установить пакет, запустив go get github.com/pkg/errors.

В тех случаях, когда вам нужно прикрепить стек-трейс или необходимую информацию об отладке к вашим ошибкам, использование функций New или Errorf этого пакета предоставляет ошибки, которые уже записываются в ваш стек-трейс, и вы так же можете прикрепить простые метаданные, используя его возможности форматирования. Errorf реализует интерфейс fmt.Formatter, то есть вы можете отформатировать его, используя руны пакета fmt ( %s, %v, %+v и т. д.).

(//6 или альтернатива)

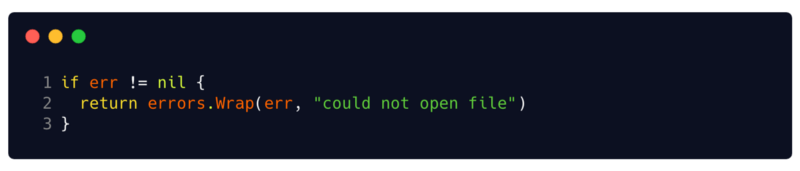

Этот пакет также представляет функции errors.Wrap и errors.Wrapf. Эти функции добавляют контекст к ошибке с помощью сообщения и стек-трейса в том месте, где они были вызваны. Таким образом, вместо простого возврата ошибки, вы можете обернуть ее контекстом и важными отладочными данными.

Обертки ошибок другими ошибками поддерживают Cause() error метод, который возвращает их внутреннюю ошибку. Кроме того, они могут использоваться сerrors.Cause(err error) error функцией, которая извлекает основную внутреннюю ошибку в оборачивающей ошибке.

Работа с ошибками

Утверждение типа

Утверждения типа (Type Assertion) играют важную роль при работе с ошибками. Вы будете использовать их для извлечения информации из интерфейсного значения, а поскольку обработка ошибок связана с пользовательскими реализациями интерфейса error, реализация утверждений на ошибках является очень удобным инструментом.

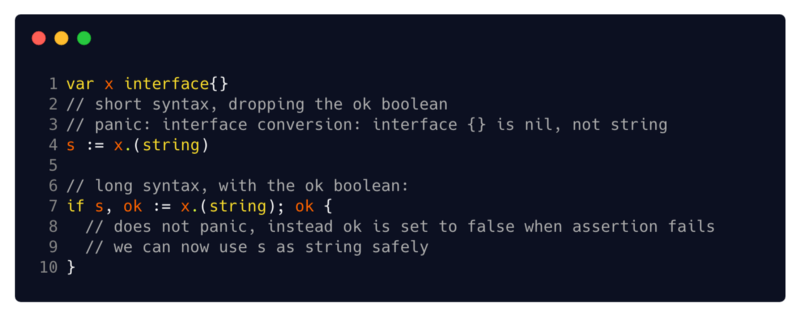

Его синтаксис одинаков для всех его целей — x.(T), если x имеет тип интерфейса. x.(T) утверждает, что x не равен nil и что значение, хранящееся в x, относится к типу T. В следующих нескольких разделах мы рассмотрим два способа использования утверждений типа — с конкретным типом T и с интерфейсом типа T.

(2//сокращенный синтаксис, пропускающий логическую переменную ok

3//паника: преобразование интерфейса: интерфейс {} равен nil, а не string

6//удлиненный синтаксис с логической переменной ok

8//не паникует, вместо этого присваивает ok false, когда утверждение ложно

9// теперь мы можем безопасно использовать s как строку)

песочница: panic при укороченном синтаксисе, безопасный удлинённый синтаксис

Дополнительное примечание, касающееся синтаксиса: утверждение типа может использоваться как с укороченным синтаксисом (который паникует при неудачном утверждении), так и с удлиненным синтаксисом (который использует логическое значение OK для указания успеха или неудачи). Я всегда рекомендую брать удлиненный вместо укороченного, так как я предпочитаю проверять переменную OK, а не разбираться с паникой.

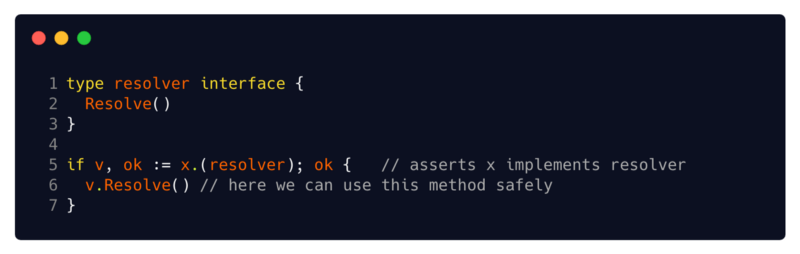

Утверждение с интерфейсом типа T

Выполнение утверждения типа x.(T) с интерфейсом типа T подтверждает, что x реализует интерфейс T. Таким образом, вы можете гарантировать, что интерфейсное значение реализует интерфейс, и только если это так, вы сможете использовать его методы.

(5…// утверждаем, что x реализует интерфейс resolver

6…// здесь мы уже можем безопасно использовать этот метод)

Чтобы понять, как это можно использовать, давайте снова взглянем на pkg/errors. Вы уже знаете этот пакет ошибок, так что давайте углубимся в errors.Cause(err error) error функцию.

Эта функция получает ошибку и извлекает самую внутреннюю ошибку, которую та переносит (ту, которая уже не служит оберткой для другой ошибки). Это может показаться примитивным, но есть много замечательных вещей, которые вы можете извлечь из этой реализации:

источник: pkg/errors

Функция получает значение ошибки, и она не может предполагать, что получаемый ею err аргумент является ошибкой-оберткой (поддерживаемой Cause методом). Поэтому перед вызовом метода Cause необходимо убедиться, что вы имеете дело с ошибкой, которая реализует этот метод. Выполняя утверждение типа в каждой итерации цикла for, вы можете убедиться, что cause переменная поддерживает метод Cause, и может продолжать извлекать из него внутренние ошибки до тех пор, пока не найдете ошибку, у которой нет Cause.

Создавая простой локальный интерфейс, содержащий только те методы, которые вам нужны, и применяя на нем утверждение, ваш код отделен от других зависимостей. Полученный вами аргумент не обязательно должен быть известной структурой, он просто должен быть ошибкой. Любой тип, реализующий методы Error и Cause, подойдет. Таким образом, если вы реализуете Cause метод в своем типе ошибки, вы можете использовать эту функцию с ним без замедлений.

Однако следует помнить об одном небольшом недостатке: интерфейсы могут изменяться, поэтому вам следует тщательно поддерживать код, чтобы ваши утверждения не нарушались. Не забудьте определить свои интерфейсы там, где вы их используете, поддерживать их стройными и аккуратными, и у вас все будет хорошо.

Наконец, если вам нужен только один метод, иногда удобнее сделать утверждение на анонимном интерфейсе, содержащем только метод, на который вы полагаетесь, т. е. v, ok := x.(interface{ F() (int, error) }). Использование анонимных интерфейсов может помочь отделить ваш код от возможных зависимостей и защитить его от возможных изменений в интерфейсах.

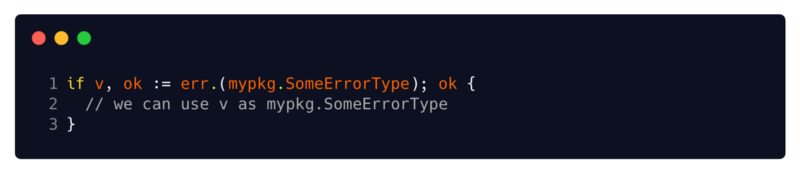

Утверждение с конкретным типом T и Type Switch

Я предваряю этот раздел введением двух похожих шаблонов обработки ошибок, которые страдают от нескольких недостатков и ловушек. Это не значит, что они не распространенные. Оба они могут быть удобными инструментами в небольших проектах, но они плохо масштабируются.

Первый — это второй вариант утверждения типа: выполняется утверждение типа x.(T) с конкретным типом T. Он утверждает, что значение x имеет тип T, или оно может быть преобразовано в тип T.

(2//мы можем использовать v как mypkg.SomeErrorType)

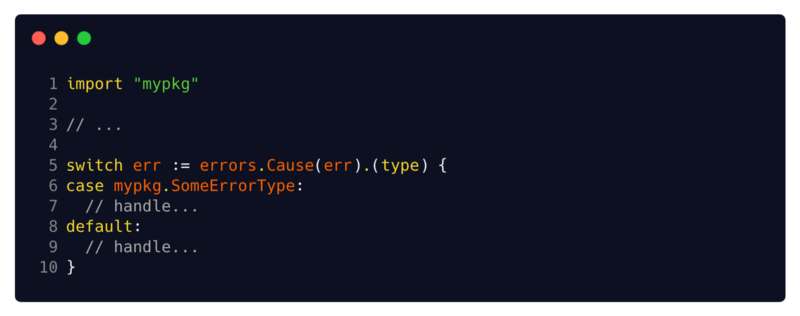

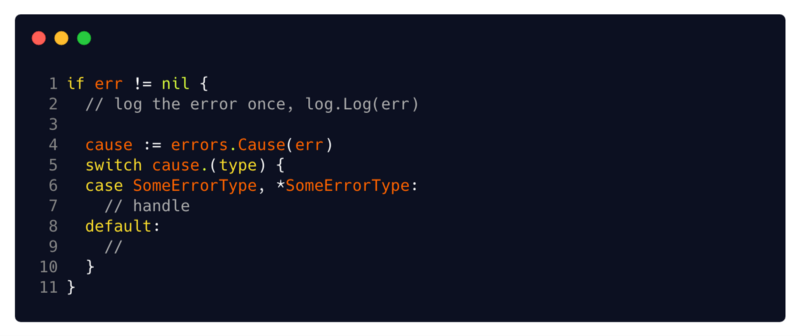

Другой — это шаблон Type Switch. Type Switch объединяют оператор switch с утверждением типа, используя зарезервированное ключевое слово type. Они особенно распространены в обработке ошибок, где знание основного типа переменной ошибки может быть очень полезным.

(3// обработка…

5// обработка…)

Большим недостатком обоих подходов является то, что оба они приводят к связыванию кода со своими зависимостями. Оба примера должны быть знакомы со структурой SomeErrorType (которая, очевидно, должна быть экспортирована) и должны импортировать пакет mypkg.

В обоих подходах при обработке ваших ошибок вы должны быть знакомы с типом и импортировать его пакет. Ситуация усугубляется, когда вы имеете дело с ошибками в обертках, где причиной ошибки может быть ошибка, возникшая из-за внутренней зависимости, о которой вы не знаете и не должны знать.

(7// обработка…

9// обработка…)

Type Switch различают *MyStruct и MyStruct. Поэтому, если вы не уверены, имеете ли вы дело с указателем или фактическим экземпляром структуры, вам придется предоставить оба варианта. Более того, как и в случае с обычными switch, кейсы в Type Switch не проваливаются, но в отличие от обычных Type Switch, использование fallthrough запрещено в Type Switch, поэтому вам придется использовать запятую и предоставлять обе опции, что легко забыть.

Подытожим

Вот и все! Теперь вы знакомы с ошибками и должны быть готовы к устранению любых ошибок, которые ваше приложение Go может выбросить (или фактически вернуть) на ваш путь!

Оба пакета errors представляют простые, но важные подходы к ошибкам в Go, и, если они удовлетворяют вашим потребностям, они являются отличным выбором. Вы можете легко реализовать свои собственные структуры ошибок и пользоваться преимуществами обработки ошибок Go, комбинируя их с pkg/errors.

Когда вы масштабируете простые ошибки, правильное использование утверждений типа может быть отличным инструментом для обработки различных ошибок. Либо с помощью Type Switch, либо путем утверждения поведения ошибки и проверки интерфейсов, которые она реализует.

Что дальше?

Обработка ошибок в Go сейчас очень актуальна. Теперь, когда вы получили основы, вам может быть интересно, что ждет нас в будущем для обработки ошибок Go!

В следующей версии Go 2 этому уделяется много внимания, и вы уже можете взглянуть на черновой вариант. Кроме того, во время dotGo 2019 Марсель ван Лохуизен провел отличную беседу на тему, которую я просто не могу не рекомендовать — «Значения ошибок GO 2 уже сегодня».

Очевидно, есть еще множество подходов, советов и хитростей, и я не могу включить их все в один пост! Несмотря на это, я надеюсь, что вам он понравился, и я увижу вас в следующем выпуске серии «Перед тем как приступать к Go»!

А теперь традиционно ждем ваши комментарии.

Error handling in Go is a little different than other mainstream programming languages like Java, JavaScript, or Python. Go’s built-in errors don’t contain stack traces, nor do they support conventional try/catch methods to handle them. Instead, errors in Go are just values returned by functions, and they can be treated in much the same way as any other datatype — leading to a surprisingly lightweight and simple design.

In this article, I’ll demonstrate the basics of handling errors in Go, as well as some simple strategies you can follow in your code to ensure your program is robust and easy to debug.

The Error Type

The error type in Go is implemented as the following interface:

type error interface {

Error() string

}So basically, an error is anything that implements the Error() method, which returns an error message as a string. It’s that simple!

Constructing Errors

Errors can be constructed on the fly using Go’s built-in errors or fmt packages. For example, the following function uses the errors package to return a new error with a static error message:

package main

import "errors"

func DoSomething() error {

return errors.New("something didn't work")

}Similarly, the fmt package can be used to add dynamic data to the error, such as an int, string, or another error. For example:

package main

import "fmt"

func Divide(a, b int) (int, error) {

if b == 0 {

return 0, fmt.Errorf("can't divide '%d' by zero", a)

}

return a / b, nil

}Note that fmt.Errorf will prove extremely useful when used to wrap another error with the %w format verb — but I’ll get into more detail on that further down in the article.

There are a few other important things to note in the example above.

-

Errors can be returned as

nil, and in fact, it’s the default, or “zero”, value of on error in Go. This is important since checkingif err != nilis the idiomatic way to determine if an error was encountered (replacing thetry/catchstatements you may be familiar with in other programming languages). -

Errors are typically returned as the last argument in a function. Hence in our example above, we return an

intand anerror, in that order. -

When we do return an error, the other arguments returned by the function are typically returned as their default “zero” value. A user of a function may expect that if a non-nil error is returned, then the other arguments returned are not relevant.

-

Lastly, error messages are usually written in lower-case and don’t end in punctuation. Exceptions can be made though, for example when including a proper noun, a function name that begins with a capital letter, etc.

Defining Expected Errors

Another important technique in Go is defining expected Errors so they can be checked for explicitly in other parts of the code. This becomes useful when you need to execute a different branch of code if a certain kind of error is encountered.

Defining Sentinel Errors

Building on the Divide function from earlier, we can improve the error signaling by pre-defining a “Sentinel” error. Calling functions can explicitly check for this error using errors.Is:

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

)

var ErrDivideByZero = errors.New("divide by zero")

func Divide(a, b int) (int, error) {

if b == 0 {

return 0, ErrDivideByZero

}

return a / b, nil

}

func main() {

a, b := 10, 0

result, err := Divide(a, b)

if err != nil {

switch {

case errors.Is(err, ErrDivideByZero):

fmt.Println("divide by zero error")

default:

fmt.Printf("unexpected division error: %sn", err)

}

return

}

fmt.Printf("%d / %d = %dn", a, b, result)

}Defining Custom Error Types

Many error-handling use cases can be covered using the strategy above, however, there can be times when you might want a little more functionality. Perhaps you want an error to carry additional data fields, or maybe the error’s message should populate itself with dynamic values when it’s printed.

You can do that in Go by implementing custom errors type.

Below is a slight rework of the previous example. Notice the new type DivisionError, which implements the Error interface. We can make use of errors.As to check and convert from a standard error to our more specific DivisionError.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

)

type DivisionError struct {

IntA int

IntB int

Msg string

}

func (e *DivisionError) Error() string {

return e.Msg

}

func Divide(a, b int) (int, error) {

if b == 0 {

return 0, &DivisionError{

Msg: fmt.Sprintf("cannot divide '%d' by zero", a),

IntA: a, IntB: b,

}

}

return a / b, nil

}

func main() {

a, b := 10, 0

result, err := Divide(a, b)

if err != nil {

var divErr *DivisionError

switch {

case errors.As(err, &divErr):

fmt.Printf("%d / %d is not mathematically valid: %sn",

divErr.IntA, divErr.IntB, divErr.Error())

default:

fmt.Printf("unexpected division error: %sn", err)

}

return

}

fmt.Printf("%d / %d = %dn", a, b, result)

}Note: when necessary, you can also customize the behavior of the errors.Is and errors.As. See this Go.dev blog for an example.

Another note: errors.Is was added in Go 1.13 and is preferable over checking err == .... More on that below.

Wrapping Errors

In these examples so far, the errors have been created, returned, and handled with a single function call. In other words, the stack of functions involved in “bubbling” up the error is only a single level deep.

Often in real-world programs, there can be many more functions involved — from the function where the error is produced, to where it is eventually handled, and any number of additional functions in-between.

In Go 1.13, several new error APIs were introduced, including errors.Wrap and errors.Unwrap, which are useful in applying additional context to an error as it “bubbles up”, as well as checking for particular error types, regardless of how many times the error has been wrapped.

A bit of history: Before Go 1.13 was released in 2019, the standard library didn’t contain many APIs for working with errors — it was basically just

errors.Newandfmt.Errorf. As such, you may encounter legacy Go programs in the wild that do not implement some of the newer error APIs. Many legacy programs also used 3rd-party error libraries such aspkg/errors. Eventually, a formal proposal was documented in 2018, which suggested many of the features we see today in Go 1.13+.

The Old Way (Before Go 1.13)

It’s easy to see just how useful the new error APIs are in Go 1.13+ by looking at some examples where the old API was limiting.

Let’s consider a simple program that manages a database of users. In this program, we’ll have a few functions involved in the lifecycle of a database error.

For simplicity’s sake, let’s replace what would be a real database with an entirely “fake” database that we import from "example.com/fake/users/db".

Let’s also assume that this fake database already contains some functions for finding and updating user records. And that the user records are defined to be a struct that looks something like:

package db

type User struct {

ID string

Username string

Age int

}

func FindUser(username string) (*User, error) { /* ... */ }

func SetUserAge(user *User, age int) error { /* ... */ }Here’s our example program:

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

"example.com/fake/users/db"

)

func FindUser(username string) (*db.User, error) {

return db.Find(username)

}

func SetUserAge(u *db.User, age int) error {

return db.SetAge(u, age)

}

func FindAndSetUserAge(username string, age int) error {

var user *User

var err error

user, err = FindUser(username)

if err != nil {

return err

}

if err = SetUserAge(user, age); err != nil {

return err

}

return nil

}

func main() {

if err := FindAndSetUserAge("bob@example.com", 21); err != nil {

fmt.Println("failed finding or updating user: %s", err)

return

}

fmt.Println("successfully updated user's age")

}Now, what happens if one of our database operations fails with some malformed request error?

The error check in the main function should catch that and print something like this:

failed finding or updating user: malformed requestBut which of the two database operations produced the error? Unfortunately, we don’t have enough information in our error log to know if it came from FindUser or SetUserAge.

Go 1.13 adds a simple way to add that information.

Errors Are Better Wrapped

The snippet below is refactored so that is uses fmt.Errorf with a %w verb to “wrap” errors as they “bubble up” through the other function calls. This adds the context needed so that it’s possible to deduce which of those database operations failed in the previous example.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

"example.com/fake/users/db"

)

func FindUser(username string) (*db.User, error) {

u, err := db.Find(username)

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("FindUser: failed executing db query: %w", err)

}

return u, nil

}

func SetUserAge(u *db.User, age int) error {

if err := db.SetAge(u, age); err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("SetUserAge: failed executing db update: %w", err)

}

}

func FindAndSetUserAge(username string, age int) error {

var user *User

var err error

user, err = FindUser(username)

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("FindAndSetUserAge: %w", err)

}

if err = SetUserAge(user, age); err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("FindAndSetUserAge: %w", err)

}

return nil

}

func main() {

if err := FindAndSetUserAge("bob@example.com", 21); err != nil {

fmt.Println("failed finding or updating user: %s", err)

return

}

fmt.Println("successfully updated user's age")

}If we re-run the program and encounter the same error, the log should print the following:

failed finding or updating user: FindAndSetUserAge: SetUserAge: failed executing db update: malformed requestNow our message contains enough information that we can see the problem originated in the db.SetUserAge function. Phew! That definitely saved us some time debugging!

If used correctly, error wrapping can provide additional context about the lineage of an error, in ways similar to a traditional stack-trace.

Wrapping also preserves the original error, which means errors.Is and errors.As continue to work, regardless of how many times an error has been wrapped. We can also call errors.Unwrap to return the previous error in the chain.

When To Wrap

Generally, it’s a good idea to wrap an error with at least the function’s name, every time you “bubble it up” — i.e. every time you receive the error from a function and want to continue returning it back up the function chain.

There are some exceptions to the rule, however, where wrapping an error may not be appropriate.

Since wrapping the error always preserves the original error messages, sometimes exposing those underlying issues might be a security, privacy, or even UX concern. In such situations, it could be worth handling the error and returning a new one, rather than wrapping it. This could be the case if you’re writing an open-source library or a REST API where you don’t want the underlying error message to be returned to the 3rd-party user.

While you’re here:

Earthly is the effortless CI/CD framework.

Develop CI/CD pipelines locally and run them anywhere!

Conclusion

That’s a wrap! In summary, here’s the gist of what was covered here:

- Errors in Go are just lightweight pieces of data that implement the

Errorinterface - Predefined errors will improve signaling, allowing us to check which error occurred

- Wrap errors to add enough context to trace through function calls (similar to a stack trace)

I hope you found this guide to effective error handling useful. If you’d like to learn more, I’ve attached some related articles I found interesting during my own journey to robust error handling in Go.

References

- Error handling and Go

- Go 1.13 Errors

- Go Error Doc

- Go By Example: Errors

- Go By Example: Panic

Get notified about new articles!

We won’t send you spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

Александр Тихоненко

Ведущий разработчик трайба «Автоматизация бизнес-процессов» МТС Диджитал

Механизм обработки ошибок в Go отличается от обработки исключений в большинстве языков программирования, ведь в Golang ошибки исключениями не являются. Если говорить в целом, то ошибка в Go — это возвращаемое значение с типомerror, которое демонстрирует сбой. А с точки зрения кода — интерфейс. В качестве ошибки может выступать любой объект, который этому интерфейсу удовлетворяет.

Выглядит это так:

type error interface {

Error() string

}

В данной статье мы рассмотрим наиболее популярные способы работы с ошибками в Golang.

- Как обрабатывать ошибки в Go?

- Создание ошибок

- Оборачивание ошибок

- Проверка типов с Is и As

- Сторонние пакеты по работе с ошибками в Go

- Defer, panic and recover

- После изложенного

Чтобы обработать ошибку в Golang, необходимо сперва вернуть из функции переменную с объявленным типом error и проверить её на nil:

if err != nil {

return err

}Если метод возвращает ошибку, значит, потенциально в его работе может возникнуть проблема, которую нужно обработать. В качестве реализации обработчика может выступать логирование ошибки или более сложные сценарии. Например, переоткрытие установленного сетевого соединения, повторный вызов метода и тому подобные операции.

Если метод возвращает разные типы ошибок, то их нужно проверять отдельно. То есть сначала происходит определение ошибки, а потом для каждого типа пишется свой обработчик.

В Go ошибки возвращаются и проверяются явно. Разработчик сам определяет, какие ошибки метод может вернуть, и реализовать их обработку на вызывающей стороне.

Создание ошибок

Перед тем как обработать ошибку, нужно её создать. В стандартной библиотеке для этого есть две встроенные функции — обе позволяют указывать и отображать сообщение об ошибке:

errors.Newfmt.Errorf

Метод errors.New() создаёт ошибку, принимая в качестве параметра текстовое сообщение.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

)

func main() {

err := errors.New("emit macho dwarf: elf header corrupted")

fmt.Print(err)

}

С помощью метода fmt.Errorf можно добавить дополнительную информацию об ошибке. Данные будут храниться внутри одной конкретной строки.

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func main() {

const name, id = "bueller", 17

err := fmt.Errorf("user %q (id %d) not found", name, id)

fmt.Print(err)

}

Такой способ подходит, если эта дополнительная информация нужна только для логирования на вызывающей стороне. Если же с ней предстоит работать, можно воспользоваться другими механизмами.

Оборачивание ошибок

Поскольку Error — это интерфейс, можно создать удовлетворяющую ему структуру с собственными полями. Тогда на вызывающей стороне этими самыми полями можно будет оперировать.

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

type NotFoundError struct {

UserId int

}

func (err NotFoundError) Error() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("user with id %d not found", err.UserId)

}

func SearchUser(id int) error {

// some logic for search

// ...

// if not found

var err NotFoundError

err.UserId = id

return err

}

func main() {

const id = 17

err := SearchUser(id)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

//type error checking

notFoundErr, ok := err.(NotFoundError)

if ok {

fmt.Println(notFoundErr.UserId)

}

}

}

Представим другую ситуацию. У нас есть метод, который вызывает внутри себя ещё один метод. В каждом из них проверяется своя ошибка. Иногда требуется в метод верхнего уровня передать сразу обе эти ошибки.

В Go есть соглашение о том, что ошибка, которая содержит внутри себя другую ошибку, может реализовать метод Unwrap, который будет возвращать исходную ошибку.

Также для оборачивания ошибок в fmt.Errorf есть плейсхолдер %w, который и позволяет произвести такую упаковку.:

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

"os"

)

func main() {

err := openFile("non-existing")

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err.Error())

// get internal error

fmt.Println(errors.Unwrap(err))

}

}

func openFile(filename string) error {

if _, err := os.Open(filename); err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("error opening %s: %w", filename, err)

}

return nil

}

Проверка типов с Is и As

В Go 1.13 в пакете Errors появились две функции, которые позволяют определить тип ошибки — чтобы написать тот или иной обработчик:

errors.Iserrors.As

Метод errors.Is, по сути, сравнивает текущую ошибку с заранее заданным значением ошибки:

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

"io/fs"

"os"

)

func main() {

if _, err := os.Open("non-existing"); err != nil {

if errors.Is(err, fs.ErrNotExist) {

fmt.Println("file does not exist")

} else {

fmt.Println(err)

}

}

}

Если это будет та же самая ошибка, то функция вернёт true, если нет — false.

errors.As проверяет, относится ли ошибка к конкретному типу (раньше надо было явно приводить тип ошибки к тому типу, который хотим проверить):

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

"io/fs"

"os"

)

func main() {

if _, err := os.Open("non-existing"); err != nil {

var pathError *fs.PathError

if errors.As(err, &pathError) {

fmt.Println("Failed at path:", pathError.Path)

} else {

fmt.Println(err)

}

}

}

Помимо прочего, эти методы удобны тем, что упрощают работу с упакованными ошибками, позволяя проверить каждую из них за один вызов.

Сторонние пакеты по работе с ошибками в Go

Помимо стандартного пакета Go, есть различные внешние библиотеки, которые расширяют функционал. При принятии решения об их использовании следует отталкиваться от задачи — использование может привести к падению производительности.

В качестве примера можно посмотреть на пакет pkg/errors. Одной из его способностей является логирование stack trace:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"github.com/pkg/errors"

)

func main() {

err := errors.Errorf("whoops: %s", "foo")

fmt.Printf("%+v", err)

}

// Example output:

// whoops: foo

// github.com/pkg/errors_test.ExampleErrorf

// /home/dfc/src/github.com/pkg/errors/example_test.go:101

// testing.runExample

// /home/dfc/go/src/testing/example.go:114

// testing.RunExamples

// /home/dfc/go/src/testing/example.go:38

// testing.(*M).Run

// /home/dfc/go/src/testing/testing.go:744

// main.main

// /github.com/pkg/errors/_test/_testmain.go:102

// runtime.main

// /home/dfc/go/src/runtime/proc.go:183

// runtime.goexit

// /home/dfc/go/src/runtime/asm_amd64.s:2059Defer, panic and recover

Помимо ошибок, о которых позаботился разработчик, в Go существуют аварии (похожи на исключительные ситуации, например, в Java). По сути, это те ошибки, которые разработчик не предусмотрел.

При возникновении таких ошибок Go останавливает выполнение программы и начинает раскручивать стек вызовов до тех пор, пока не завершит работу приложения или не найдёт функцию обработки аварии.

Для работы с такими ошибками существует механизм «defer, panic, recover»

Defer

Defer помещает все вызовы функции в стек приложения. При этом отложенные функции выполняются в обратном порядке — независимо от того, вызвана паника или нет. Это бывает полезно при очистке ресурсов:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"os"

)

func main() {

f := createFile("/tmp/defer.txt")

defer closeFile(f)

writeFile(f)

}

func createFile(p string) *os.File {

fmt.Println("creating")

f, err := os.Create(p)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

return f

}

func writeFile(f *os.File) {

fmt.Println("writing")

fmt.Fprintln(f, "data")

}

func closeFile(f *os.File) {

fmt.Println("closing")

err := f.Close()

if err != nil {

fmt.Fprintf(os.Stderr, "error: %vn", err)

os.Exit(1)

}

}

Panic

Panic сигнализирует о том, что код не может решить текущую проблему, и останавливает выполнение приложения. После вызова оператора выполняются все отложенные функции, и программа завершается с сообщением о причине паники и трассировки стека.

Например, Golang будет «паниковать», когда число делится на ноль:

panic: runtime error: integer divide by zero

goroutine 1 [running]:

main.divide(0x0)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:16 +0xe6

main.divide(0x1)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:17 +0xd6

main.divide(0x2)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:17 +0xd6

main.divide(0x3)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:17 +0xd6

main.divide(0x4)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:17 +0xd6

main.divide(0x5)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:17 +0xd6

main.main()

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:11 +0x31

exit status 2

Также панику можно вызвать явно с помощью метода panic(). Обычно его используют на этапе разработки и тестирования кода — а в конечном варианте убирают.

Recover

Эта функция нужна, чтобы вернуть контроль при панике. В таком случае работа приложения не прекращается, а восстанавливается и продолжается в нормальном режиме.

Recover всегда должна вызываться в функции defer. Чтобы сообщить об ошибке как возвращаемом значении, вы должны вызвать функцию recover в той же горутине, что и паника, получить структуру ошибки из функции восстановления и передать её в переменную:

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

)

func A() {

defer fmt.Println("Then we can't save the earth!")

defer func() {

if x := recover(); x != nil {

fmt.Printf("Panic: %+vn", x)

}

}()

B()

}

func B() {

defer fmt.Println("And if it keeps getting hotter...")

C()

}

func C() {

defer fmt.Println("Turn on the air conditioner...")

Break()

}

func Break() {

defer fmt.Println("If it's more than 30 degrees...")

panic(errors.New("Global Warming!!!"))

}

func main() {

A()

}После изложенного

Можно ли игнорировать ошибки? В теории — да. Но делать это нежелательно. Во-первых, наличие ошибки позволяет узнать, успешно ли выполнился метод. Во-вторых, если метод возвращает полезное значение и ошибку, то, не проверив её, нельзя утверждать, что полезное значение корректно.

Надеемся, приведённые методы обработки ошибок в Go будут вам полезны. Читайте также статью о 5 главных ошибках Junior-разработчика, чтобы не допускать их в начале своего карьерного пути.

import "builtin"

- Overview

- Index

Overview ▸

Overview ▾

Package builtin provides documentation for Go’s predeclared identifiers.

The items documented here are not actually in package builtin

but their descriptions here allow godoc to present documentation

for the language’s special identifiers.

Index ▸

Constants

true and false are the two untyped boolean values.

const (

true = 0 == 0

false = 0 != 0

)

iota is a predeclared identifier representing the untyped integer ordinal

number of the current const specification in a (usually parenthesized)

const declaration. It is zero-indexed.

const iota = 0

Variables

nil is a predeclared identifier representing the zero value for a

pointer, channel, func, interface, map, or slice type.

var nil Type

func append

¶

func append(slice []Type, elems ...Type) []Type

The append built-in function appends elements to the end of a slice. If

it has sufficient capacity, the destination is resliced to accommodate the

new elements. If it does not, a new underlying array will be allocated.

Append returns the updated slice. It is therefore necessary to store the

result of append, often in the variable holding the slice itself:

slice = append(slice, elem1, elem2) slice = append(slice, anotherSlice...)

As a special case, it is legal to append a string to a byte slice, like this:

slice = append([]byte("hello "), "world"...)

func cap

¶

func cap(v Type) int

The cap built-in function returns the capacity of v, according to its type:

Array: the number of elements in v (same as len(v)). Pointer to array: the number of elements in *v (same as len(v)). Slice: the maximum length the slice can reach when resliced; if v is nil, cap(v) is zero. Channel: the channel buffer capacity, in units of elements; if v is nil, cap(v) is zero.

For some arguments, such as a simple array expression, the result can be a

constant. See the Go language specification’s «Length and capacity» section for

details.

func close

¶

func close(c chan<- Type)

The close built-in function closes a channel, which must be either

bidirectional or send-only. It should be executed only by the sender,

never the receiver, and has the effect of shutting down the channel after

the last sent value is received. After the last value has been received

from a closed channel c, any receive from c will succeed without

blocking, returning the zero value for the channel element. The form

x, ok := <-c

will also set ok to false for a closed and empty channel.

func complex

¶

func complex(r, i FloatType) ComplexType

The complex built-in function constructs a complex value from two

floating-point values. The real and imaginary parts must be of the same

size, either float32 or float64 (or assignable to them), and the return

value will be the corresponding complex type (complex64 for float32,

complex128 for float64).

func copy

¶

func copy(dst, src []Type) int

The copy built-in function copies elements from a source slice into a

destination slice. (As a special case, it also will copy bytes from a

string to a slice of bytes.) The source and destination may overlap. Copy

returns the number of elements copied, which will be the minimum of

len(src) and len(dst).

func delete

¶

func delete(m map[Type]Type1, key Type)

The delete built-in function deletes the element with the specified key

(m[key]) from the map. If m is nil or there is no such element, delete

is a no-op.

func imag

¶

func imag(c ComplexType) FloatType

The imag built-in function returns the imaginary part of the complex

number c. The return value will be floating point type corresponding to

the type of c.

func len

¶

func len(v Type) int

The len built-in function returns the length of v, according to its type:

Array: the number of elements in v.

Pointer to array: the number of elements in *v (even if v is nil).

Slice, or map: the number of elements in v; if v is nil, len(v) is zero.

String: the number of bytes in v.

Channel: the number of elements queued (unread) in the channel buffer;

if v is nil, len(v) is zero.

For some arguments, such as a string literal or a simple array expression, the

result can be a constant. See the Go language specification’s «Length and

capacity» section for details.

func make

¶

func make(t Type, size ...IntegerType) Type

The make built-in function allocates and initializes an object of type

slice, map, or chan (only). Like new, the first argument is a type, not a

value. Unlike new, make’s return type is the same as the type of its

argument, not a pointer to it. The specification of the result depends on

the type:

Slice: The size specifies the length. The capacity of the slice is equal to its length. A second integer argument may be provided to specify a different capacity; it must be no smaller than the length. For example, make([]int, 0, 10) allocates an underlying array of size 10 and returns a slice of length 0 and capacity 10 that is backed by this underlying array. Map: An empty map is allocated with enough space to hold the specified number of elements. The size may be omitted, in which case a small starting size is allocated. Channel: The channel's buffer is initialized with the specified buffer capacity. If zero, or the size is omitted, the channel is unbuffered.

func new

¶

func new(Type) *Type

The new built-in function allocates memory. The first argument is a type,

not a value, and the value returned is a pointer to a newly

allocated zero value of that type.

func panic

¶

func panic(v any)

The panic built-in function stops normal execution of the current

goroutine. When a function F calls panic, normal execution of F stops

immediately. Any functions whose execution was deferred by F are run in

the usual way, and then F returns to its caller. To the caller G, the

invocation of F then behaves like a call to panic, terminating G’s

execution and running any deferred functions. This continues until all

functions in the executing goroutine have stopped, in reverse order. At

that point, the program is terminated with a non-zero exit code. This

termination sequence is called panicking and can be controlled by the

built-in function recover.

func print

¶

func print(args ...Type)

The print built-in function formats its arguments in an

implementation-specific way and writes the result to standard error.

Print is useful for bootstrapping and debugging; it is not guaranteed

to stay in the language.

func println

¶

func println(args ...Type)

The println built-in function formats its arguments in an

implementation-specific way and writes the result to standard error.

Spaces are always added between arguments and a newline is appended.

Println is useful for bootstrapping and debugging; it is not guaranteed

to stay in the language.

func real

¶

func real(c ComplexType) FloatType

The real built-in function returns the real part of the complex number c.

The return value will be floating point type corresponding to the type of c.

func recover

¶

func recover() any

The recover built-in function allows a program to manage behavior of a

panicking goroutine. Executing a call to recover inside a deferred

function (but not any function called by it) stops the panicking sequence

by restoring normal execution and retrieves the error value passed to the

call of panic. If recover is called outside the deferred function it will

not stop a panicking sequence. In this case, or when the goroutine is not

panicking, or if the argument supplied to panic was nil, recover returns

nil. Thus the return value from recover reports whether the goroutine is

panicking.

type ComplexType

¶

ComplexType is here for the purposes of documentation only. It is a

stand-in for either complex type: complex64 or complex128.

type ComplexType complex64

type FloatType

¶

FloatType is here for the purposes of documentation only. It is a stand-in

for either float type: float32 or float64.

type FloatType float32

type IntegerType

¶

IntegerType is here for the purposes of documentation only. It is a stand-in

for any integer type: int, uint, int8 etc.

type IntegerType int

type Type

¶

Type is here for the purposes of documentation only. It is a stand-in

for any Go type, but represents the same type for any given function

invocation.

type Type int

type Type1

¶

Type1 is here for the purposes of documentation only. It is a stand-in

for any Go type, but represents the same type for any given function

invocation.

type Type1 int

type any

¶

any is an alias for interface{} and is equivalent to interface{} in all ways.

type any = interface{}

type bool

¶

bool is the set of boolean values, true and false.

type bool bool

type byte

¶

byte is an alias for uint8 and is equivalent to uint8 in all ways. It is

used, by convention, to distinguish byte values from 8-bit unsigned

integer values.

type byte = uint8

type comparable

¶

comparable is an interface that is implemented by all comparable types

(booleans, numbers, strings, pointers, channels, arrays of comparable types,

structs whose fields are all comparable types).

The comparable interface may only be used as a type parameter constraint,

not as the type of a variable.

type comparable interface{ comparable }

type complex128

¶

complex128 is the set of all complex numbers with float64 real and

imaginary parts.

type complex128 complex128

type complex64

¶

complex64 is the set of all complex numbers with float32 real and

imaginary parts.

type complex64 complex64

type error

¶

The error built-in interface type is the conventional interface for

representing an error condition, with the nil value representing no error.

type error interface {

Error() string

}

type float32

¶

float32 is the set of all IEEE-754 32-bit floating-point numbers.

type float32 float32

type float64

¶

float64 is the set of all IEEE-754 64-bit floating-point numbers.

type float64 float64

type int

¶

int is a signed integer type that is at least 32 bits in size. It is a

distinct type, however, and not an alias for, say, int32.

type int int

type int16

¶

int16 is the set of all signed 16-bit integers.

Range: -32768 through 32767.

type int16 int16

type int32

¶

int32 is the set of all signed 32-bit integers.

Range: -2147483648 through 2147483647.

type int32 int32

type int64

¶

int64 is the set of all signed 64-bit integers.

Range: -9223372036854775808 through 9223372036854775807.

type int64 int64

type int8

¶

int8 is the set of all signed 8-bit integers.

Range: -128 through 127.

type int8 int8

type rune

¶

rune is an alias for int32 and is equivalent to int32 in all ways. It is

used, by convention, to distinguish character values from integer values.

type rune = int32

type string

¶

string is the set of all strings of 8-bit bytes, conventionally but not

necessarily representing UTF-8-encoded text. A string may be empty, but

not nil. Values of string type are immutable.

type string string

type uint

¶

uint is an unsigned integer type that is at least 32 bits in size. It is a

distinct type, however, and not an alias for, say, uint32.

type uint uint

type uint16

¶

uint16 is the set of all unsigned 16-bit integers.

Range: 0 through 65535.

type uint16 uint16

type uint32

¶

uint32 is the set of all unsigned 32-bit integers.

Range: 0 through 4294967295.

type uint32 uint32

type uint64

¶

uint64 is the set of all unsigned 64-bit integers.

Range: 0 through 18446744073709551615.

type uint64 uint64

type uint8

¶

uint8 is the set of all unsigned 8-bit integers.

Range: 0 through 255.

type uint8 uint8

type uintptr

¶

uintptr is an integer type that is large enough to hold the bit pattern of

any pointer.

type uintptr uintptr

In this article, we’ll take a look at how to handle errors using build-in Golang functionality, how you can extract information from the errors you are receiving and the best practices to do so.

Error handling in Golang is unconventional when compared to other mainstream languages like Javascript, Java and Python. This can make it very difficult for new programmers to grasp Golangs approach of tackling error handling.

In this article, we’ll take a look at how to handle errors using build-in Golang functionality, how you can extract information from the errors you are receiving and the best practices to do so. A basic understanding of Golang is therefore required to follow this article. If you are unsure about any concepts, you can look them up here.

Errors in Golang

Errors indicate an unwanted condition occurring in your application. Let’s say you want to create a temporary directory where you can store some files for your application, but the directory’s creation fails. This is an unwanted condition and is therefore represented using an error.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"ioutil"

)

func main() {

dir, err := ioutil.TempDir("", "temp")

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("failed to create temp dir: %v", err)

}

}

Golang represents errors using the built-in error type, which we will look at closer in the next section. The error is often returned as a second argument of the function, as shown in the example above. Here the TempDir function returns the name of the directory as well as an error variable.

Creating custom errors

As already mentioned errors are represented using the built-in error interface type, which has the following definition:

type error interface {

Error() string

}

The interface contains a single method Error() that returns an error message as a string. Every type that implements the error interface can be used as an error. When printing the error using methods like fmt.Println the Error() method is automatically called by Golang.

There are multiple ways of creating custom error messages in Golang, each with its own advantages and disadvantages.

String-based errors

String-based errors can be created using two out-of-the-box options in Golang and are used for simple errors that just need to return an error message.

err := errors.New("math: divided by zero")

The errors.New() method can be used to create new errors and takes the error message as its only parameter.

err2 := fmt.Errorf("math: %g cannot be divided by zero", x)

fmt.Errorf on the other hand also provides the ability to add formatting to your error message. Above you can see that a parameter can be passed which will be included in the error message.

Custom error with data

You can create your own error type by implementing the Error() function defined in the error interface on your struct. Here is an example:

type PathError struct {

Path string

}

func (e *PathError) Error() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("error in path: %v", e.Path)

}

The PathError implements the Error() function and therefore satisfies the error interface. The implementation of the Error() function now returns a string with the path of the PathError struct. You can now use PathError whenever you want to throw an error.

Here is an elementary example:

package main

import(

"fmt"

)

type PathError struct {

Path string

}

func (e *PathError) Error() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("error in path: %v", e.Path)

}

func throwError() error {

return &PathError{Path: "/test"}

}

func main() {

err := throwError()

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

}

}

You can also check if the error has a specific type using either an if or switch statement:

if err != nil {

switch e := err.(type) {

case *PathError :

// Do something with the path

default:

log.Println(e)

}

}

This will allow you to extract more information from your errors because you can then call all functions that are implemented on the specific error type. For example, if the PathError had a second method called GetInfo you could call it like this.

e.GetInfo()

Error handling in functions

Now that you know how to create your own custom errors and extract as much information as possible from errors let’s take a look at how you can handle errors in functions.

Most of the time errors are not directly handled in functions but are returned as a return value instead. Here we can take advantage of the fact that Golang supports multiple return values for a function. Thus you can return your error alongside the normal result — errors are always returned as the last argument — of the function as follows:

func divide(a, b float64) (float64, error) {

if b == 0 {

return 0.0, errors.New("cannot divide through zero")

}

return a/b, nil

}

The function call will then look similar to this:

func main() {

num, err := divide(100, 0)

if err != nil {

fmt.Printf("error: %s", err.Error())

} else {

fmt.Println("Number: ", num)

}

}

If the returned error is not nil it usually means that there is a problem and you need to handle the error appropriately. This can mean that you use some kind of log message to warn the user, retry the function until it works or close the application entirely depending on the situation. The only drawback is that Golang does not enforce handling the retuned errors, which means that you could just ignore handling errors completely.

Take the following code for example:

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

)

func main() {

num2, _ := divide(100, 0)

fmt.Println("Number: ", num2)

}

The so-called blank identifier is used as an anonymous placeholder and therefore provides a way to ignore values in an assignment and avoid compiler errors in the process. But remember that using the blank identifier instead of probably handling errors is dangerous and should not be done if it can be avoided.

Defer, panic and recover

Go does not have exceptions like many other programming languages, including Java and Javascript but has a comparable mechanism know as ,,Defer, panic and recover». Still the use-cases of panic and recover are very different from exceptions in other programming languages as they should only be used in unexpected and unrecoverable situations.

Defer

A defer statement is a mechanism used to defer a function by putting it into an executed stack once the function that contains the defer statement has finished, either normally by executing a return statement or abnormally panicking. Deferred functions will then be executed in reverse order in which they were deferred.

Take the following function for example:

func processHTML(url string) error {

resp, err := http.Get(url)

if err != nil {

return err

}

ct := resp.Header.Get("Content-Type")

if ct != "text/html" && !strings.HasPrefix(ct, "text/html;") {

resp.Body.Close()

return fmt.Errorf("%s has content type %s which does not match text/html", url, ct)

}

doc, err := html.Parse(resp.Body)

resp.Body.Close()

// ... Process HTML ...

return nil

}

Here you can notice the duplicated resp.Body.Close call, which ensures that the response is properly closed. Once functions grow more complex and have more errors that need to be handled such duplications get more and more problematic to maintain.

Since deferred calls get called once the function has ended, no matter if it succeeded or not it can be used to simplify such calls.

func processHTMLDefer(url string) error {

resp, err := http.Get(url)

if err != nil {

return err

}

defer resp.Body.Close()

ct := resp.Header.Get("Content-Type")

if ct != "text/html" && !strings.HasPrefix(ct, "text/html;") {

return fmt.Errorf("%s has content type %s which does not match text/html", url, ct)

}

doc, err := html.Parse(resp.Body)

// ... Process HTML ...

return nil

}

All deferred functions are executed in reverse order in which they were deferred when the function finishes.

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func main() {

first()

}

func first() {

defer fmt.Println("first")

second()

}

func second() {

defer fmt.Println("second")

third()

}

func third() {

defer fmt.Println("third")

}

Here is the result of running the above program:

third

second

first

Panic

A panic statement signals Golang that your code cannot solve the current problem and it therefore stops the normal execution flow of your code. Once a panic is called, all deferred functions are executed and the program crashes with a log message that includes the panic values (usually an error message) and a stack trace.

As an example Golang will panic when a number is divided by zero.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

divide(5)

}

func divide(x int) {

fmt.Printf("divide(%d) n", x+0/x)

divide(x-1)

}

Once the divide function is called using zero, the program will panic, resulting in the following output.

panic: runtime error: integer divide by zero

goroutine 1 [running]:

main.divide(0x0)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:16 +0xe6

main.divide(0x1)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:17 +0xd6

main.divide(0x2)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:17 +0xd6

main.divide(0x3)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:17 +0xd6

main.divide(0x4)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:17 +0xd6

main.divide(0x5)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:17 +0xd6

main.main()

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:11 +0x31

exit status 2

You can also use the built-in panic function to panic in your own programms. A panic should mostly only be used when something happens that the program didn’t expect and cannot handle.

func getArguments() {

if len(os.Args) == 1 {

panic("Not enough arguments!")

}

}

As already mentioned, deferred functions will be executed before terminating the application, as shown in the following example.

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func main() {

accessSlice([]int{1,2,5,6,7,8}, 0)

}

func accessSlice(slice []int, index int) {

fmt.Printf("item %d, value %d n", index, slice[index])

defer fmt.Printf("defer %d n", index)

accessSlice(slice, index+1)

}

Here is the output of the programm:

item 0, value 1

item 1, value 2

item 2, value 5

item 3, value 6

item 4, value 7

item 5, value 8

defer 5

defer 4

defer 3

defer 2

defer 1

defer 0

panic: runtime error: index out of range [6] with length 6

goroutine 1 [running]:

main.accessSlice(0xc00011df48, 0x6, 0x6, 0x6)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:29 +0x250

main.accessSlice(0xc00011df48, 0x6, 0x6, 0x5)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:31 +0x1eb

main.accessSlice(0xc00011df48, 0x6, 0x6, 0x4)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:31 +0x1eb

main.accessSlice(0xc00011df48, 0x6, 0x6, 0x3)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:31 +0x1eb

main.accessSlice(0xc00011df48, 0x6, 0x6, 0x2)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:31 +0x1eb

main.accessSlice(0xc00011df48, 0x6, 0x6, 0x1)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:31 +0x1eb

main.accessSlice(0xc00011df48, 0x6, 0x6, 0x0)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:31 +0x1eb

main.main()

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:9 +0x99

exit status 2

Recover

In some rare cases panics should not terminate the application but be recovered instead. For example, a socket server that encounters an unexpected problem could report the error to the clients and then close all connections rather than leaving the clients wondering what just happened.

Panics can therefore be recovered by calling the built-in recover function within a deferred function in the function that is panicking. Recover will then end the current state of panic and return the panic error value.

package main

import "fmt"

func main(){

accessSlice([]int{1,2,5,6,7,8}, 0)

}

func accessSlice(slice []int, index int) {

defer func() {

if p := recover(); p != nil {

fmt.Printf("internal error: %v", p)

}

}()

fmt.Printf("item %d, value %d n", index, slice[index])

defer fmt.Printf("defer %d n", index)

accessSlice(slice, index+1)

}

As you can see after adding a recover function to the function we coded above the program doesn’t exit anymore when the index is out of bounds by recovers instead.

Output:

item 0, value 1

item 1, value 2

item 2, value 5

item 3, value 6

item 4, value 7

item 5, value 8

internal error: runtime error: index out of range [6] with length 6defer 5

defer 4

defer 3

defer 2

defer 1

defer 0

Recovering from panics can be useful in some cases, but as a general rule you should try to avoid recovering from panics.

Error wrapping

Golang also allows errors to wrap other errors which provides the functionality to provide additional context to your error messages. This is often used to provide specific information like where the error originated in your program.

You can create wrapped errors by using the %w flag with the fmt.Errorf function as shown in the following example.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

"os"

)

func main() {

err := openFile("non-existing")

if err != nil {

fmt.Printf("error running program: %s n", err.Error())

}

}

func openFile(filename string) error {

if _, err := os.Open(filename); err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("error opening %s: %w", filename, err)

}

return nil

}

The output of the application would now look like the following:

error running program: error opening non-existing: open non-existing: no such file or directory

As you can see the application prints both the new error created using fmt.Errorf as well as the old error message that was passed to the %w flag. Golang also provides the functionality to get the old error message back by unwrapping the error using errors.Unwrap.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

"os"

)

func main() {

err := openFile("non-existing")

if err != nil {

fmt.Printf("error running program: %s n", err.Error())

// Unwrap error

unwrappedErr := errors.Unwrap(err)

fmt.Printf("unwrapped error: %v n", unwrappedErr)

}

}

func openFile(filename string) error {

if _, err := os.Open(filename); err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("error opening %s: %w", filename, err)

}

return nil

}

As you can see the output now also displays the original error.

error running program: error opening non-existing: open non-existing: no such file or directory

unwrapped error: open non-existing: no such file or directory

Errors can be wrapped and unwrapped multiple times, but in most cases wrapping them more than a few times does not make sense.

Casting Errors

Sometimes you will need a way to cast between different error types to for example, access unique information that only that type has. The errors.As function provides an easy and safe way to do so by looking for the first error in the error chain that fits the requirements of the error type. If no match is found the function returns false.

Let’s look at the official errors.As docs example to better understand what is happening.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

"io/fs"

"os"

)

func main(){

// Casting error

if _, err := os.Open("non-existing"); err != nil {

var pathError *os.PathError

if errors.As(err, &pathError) {

fmt.Println("Failed at path:", pathError.Path)

} else {

fmt.Println(err)

}

}

}

Here we try to cast our generic error type to os.PathError so we can access the Path variable that that specific error contains.

Another useful functionality is checking if an error has a specific type. Golang provides the errors.Is function to do exactly that. Here you provide your error as well as the particular error type you want to check. If the error matches the specific type the function will return true, if not it will return false.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

"io/fs"

"os"

)

func main(){

// Check if error is a specific type

if _, err := os.Open("non-existing"); err != nil {

if errors.Is(err, fs.ErrNotExist) {

fmt.Println("file does not exist")

} else {

fmt.Println(err)

}

}

}

After checking, you can adapt your error message accordingly.

Sources

- Golang Blog — Working with Errors in Go 1.13

- The Go Programming language book

- Golang Blog — Defer, Panic, and Recover

- LogRocket — Error handling in Golang

- GolangByExample — Wrapping and Un-wrapping of error in Go

- Golang Documentation — Package errors

Conclusion

You made it all the way until the end! I hope this article helped you understand the basics of Go error handling and why it is an essential topic in application/software development.

If you have found this helpful, please consider recommending and sharing it with other fellow developers and subscribing to my newsletter. If you have any questions or feedback, let me know using my contact form or contact me on Twitter.

Errors are a language-agnostic part that helps to write code in such a way that no unexpected thing happens. When something occurs which is not supported by any means then an error occurs. Errors help to write clean code that increases the maintainability of the program.

What is an error?

An error is a well developed abstract concept which occurs when an exception happens. That is whenever something unexpected happens an error is thrown. Errors are common in every language which basically means it is a concept in the realm of programming.

Why do we need Error?

Errors are a part of any program. An error tells if something unexpected happens. Errors also help maintain code stability and maintainability. Without errors, the programs we use today will be extremely buggy due to a lack of testing.

Golang has support for errors in a really simple way. Go functions returns errors as a second return value. That is the standard way of implementing and using errors in Go. That means the error can be checked immediately before proceeding to the next steps.

Simple Error Methods

There are multiple methods for creating errors. Here we will discuss the simple ones that can be created without much effort.

1. Using the New function

Golang errors package has a function called New() which can be used to create errors easily. Below it is in action.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"errors"

)

func e(v int) (int, error) {

if v == 0 {

return 0, errors.New("Zero cannot be used")

} else {

return 2*v, nil

}

}

func main() {

v, err := e(0)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err, v) // Zero cannot be used 0

}

}

2. Using the Errorf function

The fmt package has an Errorf() method that allows formatted errors as shown below.

fmt.Errorf("Error: Zero not allowed! %v", v) // Error: Zero not allowed! 0

Checking for an Error

To check for an error we simply get the second value of the function and then check the value with the nil. Since the zero value of an error is nil. So, we check if an error is a nil. If it is then no error has occurred and all other cases the error has occurred.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"errors"

)

func e(v int) (int, error) {

return 42, errors.New("42 is unexpected!")

}

func main() {

_, err := e(0)

if err != nil { // check error here

fmt.Println(err) // 42 is unexpected!

}

}

Panic and recover

Panic occurs when an unexpected wrong thing happens. It stops the function execution. Recover is the opposite of it. It allows us to recover the execution from stopping. Below shown code illustrates the concept.

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func f(s string) {

panic(s) // throws panic

}

func main() {

// defer makes the function run at the end

defer func() { // recovers panic

if e := recover(); e != nil {

fmt.Println("Recovered from panic")

}

}()

f("Panic occurs!!!") // throws panic

// output:

// Recovered from panic

}

Creating custom errors

As we have seen earlier the function errors.New() and fmt.Errorf() both can be used to create new errors. But there is another way we can do that. And that is implementing the error interface.

type CustomError struct {

data string

}

func (e *CustomError) Error() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("Error occured due to... %s", e.data)

}

Returning error alongside values

Returning errors are pretty easy in Go. Go supports multiple return values. So we can return any value and error both at the same time and then check the error. Here is a way to do that.

import (

"fmt"

"errors"

)

func returnError() (int, error) { // declare return type here

return 42, errors.New("Error occured!") // return it here

}

func main() {

v, e := returnError()

if e != nil {

fmt.Println(e, v) // Error occured! 42

}

}

Ignoring errors in Golang

Go has the skip (-) operator which allows skipping returned errors at all. Simply using the skip operator helps here.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"errors"

)

func returnError() (int, error) { // declare return type here

return 42, errors.New("Error occured!") // return it here

}

func main() {

v, _ := returnError() // skip error with skip operator

fmt.Println(v) // 42

}

Если вы писали какой-либо код на Go, вы, вероятно, сталкивались со встроенным типом error. Код Go использует значения error, чтобы указать ненормальное состояние. Например, функция os.Open возвращает ненулевое значение error, когда не удается открыть файл.

func Open(name string) (file *File, err error)

Следующий код использует os.Open для открытия файла. Если возникает ошибка, она вызывает log.Fatal, чтобы распечатать сообщение об ошибке и остановить исполнение.

f, err := os.Open("filename.ext")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

// делаем что-либо с открытым *File f

Вы можете многое сделать в Go, зная только это о типе error, но в этом посте мы более подробно рассмотрим error и обсудим некоторые методы обработки ошибок в Go.

Тип error

Тип error — это тип интерфейса. Переменная error представляет любое значение, которое может быть описано как строка. Вот объявление интерфейса:

type error interface {

Error() string

}

Тип error, как и для всех встроенных типов, предварительно объявлен в блоке юниверса (universe block).

Наиболее часто используемая реализация error — это неэкспортируемый тип errorString пакета errors.

// errorString это тривиальная реализация error.

type errorString struct {

s string

}

func (e *errorString) Error() string {

return e.s

}

Вы можете создать одно из этих значений с помощью функции errors.New. Он принимает строку, которая преобразуется в error.errorString и возвращает значение error.

// New возвращает ошибку, которая форматируется как заданный текст.

func New(text string) error {

return &errorString{text}

}

Вот как вы можете использовать errors.New:

func Sqrt(f float64) (float64, error) {

if f < 0 {

return 0, errors.New("math: square root of negative number")

}

// реализация

}

Вызывающая сторона, передающая отрицательный аргумент в Sqrt, получает ненулевое значение ошибки (конкретное представление которого является значением errors.errorString). Вызывающая сторона может получить доступ к строке ошибки («math: square root of…»), вызвав метод Error ошибки или просто распечатав его:

f, err := Sqrt(-1)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

}

Пакет fmt форматирует значение ошибки, вызывая его строковый метод Error().

Ответственность за реализацию ошибки заключается в обобщении контекста. Ошибка, возвращаемая форматом os.Open как «open /etc/passwd: permission denied», а не просто «permission denied». Ошибка, возвращаемая нашим Sqrt, содержит информацию о недопустимом аргументе.

Чтобы добавить эту информацию, полезной функцией является Errorf пакета fmt. Она форматирует строку в соответствии с правилами Printf и возвращает ее как ошибку, созданную errors.New.

if f < 0 {

return 0, fmt.Errorf("math: square root of negative number %g", f)

}

Во многих случаях fmt.Errorf достаточно хорош, но, поскольку error является интерфейсом, вы можете использовать произвольные структуры данных в качестве значений ошибок, чтобы позволить вызывающим абонентам просматривать подробности ошибки.

Например, наши гипотетические пользователи могут захотеть восстановить неверный аргумент, переданный Sqrt. Мы можем включить это, определив новую реализацию ошибок вместо использования errors.errorString:

type NegativeSqrtError float64

func (f NegativeSqrtError) Error() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("math: square root of negative number %g", float64(f))

}

Сложный вызывающий объект может затем использовать утверждение типа, чтобы проверить наличие NegativeSqrtError и обработать его специально, в то время как вызывающие элементы, которые просто передают ошибку в fmt.Println или log.Fatal, не увидят никаких изменений в поведении.

В качестве другого примера, пакет json указывает тип SyntaxError, который функция json.Decode возвращает, когда сталкивается с синтаксической ошибкой при разборе BLOB-объекта JSON.

type SyntaxError struct {

msg string // описание ошибки

Offset int64 // ошибка произошла после чтения Offset байтов

}

func (e *SyntaxError) Error() string { return e.msg }