The Go Blog

Introduction

If you have written any Go code you have probably encountered the built-in error type.

Go code uses error values to indicate an abnormal state.

For example, the os.Open function returns a non-nil error value when

it fails to open a file.

func Open(name string) (file *File, err error)

The following code uses os.Open to open a file.

If an error occurs it calls log.Fatal to print the error message and stop.

f, err := os.Open("filename.ext")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

// do something with the open *File f

You can get a lot done in Go knowing just this about the error type,

but in this article we’ll take a closer look at error and discuss some

good practices for error handling in Go.

The error type

The error type is an interface type. An error variable represents any

value that can describe itself as a string.

Here is the interface’s declaration:

type error interface {

Error() string

}

The error type, as with all built in types,

is predeclared

in the universe block.

The most commonly-used error implementation is the errors

package’s unexported errorString type.

// errorString is a trivial implementation of error.

type errorString struct {

s string

}

func (e *errorString) Error() string {

return e.s

}

You can construct one of these values with the errors.New function.

It takes a string that it converts to an errors.errorString and returns

as an error value.

// New returns an error that formats as the given text.

func New(text string) error {

return &errorString{text}

}

Here’s how you might use errors.New:

func Sqrt(f float64) (float64, error) {

if f < 0 {

return 0, errors.New("math: square root of negative number")

}

// implementation

}

A caller passing a negative argument to Sqrt receives a non-nil error

value (whose concrete representation is an errors.errorString value).

The caller can access the error string (“math:

square root of…”) by calling the error’s Error method,

or by just printing it:

f, err := Sqrt(-1)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

}

The fmt package formats an error value by calling its Error() string method.

It is the error implementation’s responsibility to summarize the context.

The error returned by os.Open formats as “open /etc/passwd:

permission denied,” not just “permission denied.” The error returned by

our Sqrt is missing information about the invalid argument.

To add that information, a useful function is the fmt package’s Errorf.

It formats a string according to Printf’s rules and returns it as an error

created by errors.New.

if f < 0 {

return 0, fmt.Errorf("math: square root of negative number %g", f)

}

In many cases fmt.Errorf is good enough,

but since error is an interface, you can use arbitrary data structures as error values,

to allow callers to inspect the details of the error.

For instance, our hypothetical callers might want to recover the invalid

argument passed to Sqrt.

We can enable that by defining a new error implementation instead of using

errors.errorString:

type NegativeSqrtError float64

func (f NegativeSqrtError) Error() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("math: square root of negative number %g", float64(f))

}

A sophisticated caller can then use a type assertion

to check for a NegativeSqrtError and handle it specially,

while callers that just pass the error to fmt.Println or log.Fatal will

see no change in behavior.

As another example, the json

package specifies a SyntaxError type that the json.Decode function returns

when it encounters a syntax error parsing a JSON blob.

type SyntaxError struct {

msg string // description of error

Offset int64 // error occurred after reading Offset bytes

}

func (e *SyntaxError) Error() string { return e.msg }

The Offset field isn’t even shown in the default formatting of the error,

but callers can use it to add file and line information to their error messages:

if err := dec.Decode(&val); err != nil {

if serr, ok := err.(*json.SyntaxError); ok {

line, col := findLine(f, serr.Offset)

return fmt.Errorf("%s:%d:%d: %v", f.Name(), line, col, err)

}

return err

}

(This is a slightly simplified version of some actual code

from the Camlistore project.)

The error interface requires only a Error method;

specific error implementations might have additional methods.

For instance, the net package returns errors of type error,

following the usual convention, but some of the error implementations have

additional methods defined by the net.Error interface:

package net

type Error interface {

error

Timeout() bool // Is the error a timeout?

Temporary() bool // Is the error temporary?

}

Client code can test for a net.Error with a type assertion and then distinguish

transient network errors from permanent ones.

For instance, a web crawler might sleep and retry when it encounters a temporary

error and give up otherwise.

if nerr, ok := err.(net.Error); ok && nerr.Temporary() {

time.Sleep(1e9)

continue

}

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

Simplifying repetitive error handling

In Go, error handling is important. The language’s design and conventions

encourage you to explicitly check for errors where they occur (as distinct

from the convention in other languages of throwing exceptions and sometimes catching them).

In some cases this makes Go code verbose,

but fortunately there are some techniques you can use to minimize repetitive error handling.

Consider an App Engine

application with an HTTP handler that retrieves a record from the datastore

and formats it with a template.

func init() {

http.HandleFunc("/view", viewRecord)

}

func viewRecord(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

c := appengine.NewContext(r)

key := datastore.NewKey(c, "Record", r.FormValue("id"), 0, nil)

record := new(Record)

if err := datastore.Get(c, key, record); err != nil {

http.Error(w, err.Error(), 500)

return

}

if err := viewTemplate.Execute(w, record); err != nil {

http.Error(w, err.Error(), 500)

}

}

This function handles errors returned by the datastore.Get function and

viewTemplate’s Execute method.

In both cases, it presents a simple error message to the user with the HTTP

status code 500 (“Internal Server Error”).

This looks like a manageable amount of code,

but add some more HTTP handlers and you quickly end up with many copies

of identical error handling code.

To reduce the repetition we can define our own HTTP appHandler type that includes an error return value:

type appHandler func(http.ResponseWriter, *http.Request) error

Then we can change our viewRecord function to return errors:

func viewRecord(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) error {

c := appengine.NewContext(r)

key := datastore.NewKey(c, "Record", r.FormValue("id"), 0, nil)

record := new(Record)

if err := datastore.Get(c, key, record); err != nil {

return err

}

return viewTemplate.Execute(w, record)

}

This is simpler than the original version,

but the http package doesn’t understand

functions that return error.

To fix this we can implement the http.Handler interface’s ServeHTTP

method on appHandler:

func (fn appHandler) ServeHTTP(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

if err := fn(w, r); err != nil {

http.Error(w, err.Error(), 500)

}

}

The ServeHTTP method calls the appHandler function and displays the

returned error (if any) to the user.

Notice that the method’s receiver, fn, is a function.

(Go can do that!) The method invokes the function by calling the receiver

in the expression fn(w, r).

Now when registering viewRecord with the http package we use the Handle

function (instead of HandleFunc) as appHandler is an http.Handler

(not an http.HandlerFunc).

func init() {

http.Handle("/view", appHandler(viewRecord))

}

With this basic error handling infrastructure in place,

we can make it more user friendly.

Rather than just displaying the error string,

it would be better to give the user a simple error message with an appropriate HTTP status code,

while logging the full error to the App Engine developer console for debugging purposes.

To do this we create an appError struct containing an error and some other fields:

type appError struct {

Error error

Message string

Code int

}

Next we modify the appHandler type to return *appError values:

type appHandler func(http.ResponseWriter, *http.Request) *appError

(It’s usually a mistake to pass back the concrete type of an error rather than error,

for reasons discussed in the Go FAQ,

but it’s the right thing to do here because ServeHTTP is the only place

that sees the value and uses its contents.)

And make appHandler’s ServeHTTP method display the appError’s Message

to the user with the correct HTTP status Code and log the full Error

to the developer console:

func (fn appHandler) ServeHTTP(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

if e := fn(w, r); e != nil { // e is *appError, not os.Error.

c := appengine.NewContext(r)

c.Errorf("%v", e.Error)

http.Error(w, e.Message, e.Code)

}

}

Finally, we update viewRecord to the new function signature and have it

return more context when it encounters an error:

func viewRecord(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) *appError {

c := appengine.NewContext(r)

key := datastore.NewKey(c, "Record", r.FormValue("id"), 0, nil)

record := new(Record)

if err := datastore.Get(c, key, record); err != nil {

return &appError{err, "Record not found", 404}

}

if err := viewTemplate.Execute(w, record); err != nil {

return &appError{err, "Can't display record", 500}

}

return nil

}

This version of viewRecord is the same length as the original,

but now each of those lines has specific meaning and we are providing a

friendlier user experience.

It doesn’t end there; we can further improve the error handling in our application. Some ideas:

-

give the error handler a pretty HTML template,

-

make debugging easier by writing the stack trace to the HTTP response when the user is an administrator,

-

write a constructor function for

appErrorthat stores the stack trace for easier debugging, -

recover from panics inside the

appHandler,

logging the error to the console as “Critical,” while telling the user “a

serious error has occurred.” This is a nice touch to avoid exposing the

user to inscrutable error messages caused by programming errors.

See the Defer, Panic, and Recover

article for more details.

Conclusion

Proper error handling is an essential requirement of good software.

By employing the techniques described in this post you should be able to

write more reliable and succinct Go code.

In this article, we’ll take a look at how to handle errors using build-in Golang functionality, how you can extract information from the errors you are receiving and the best practices to do so.

Error handling in Golang is unconventional when compared to other mainstream languages like Javascript, Java and Python. This can make it very difficult for new programmers to grasp Golangs approach of tackling error handling.

In this article, we’ll take a look at how to handle errors using build-in Golang functionality, how you can extract information from the errors you are receiving and the best practices to do so. A basic understanding of Golang is therefore required to follow this article. If you are unsure about any concepts, you can look them up here.

Errors in Golang

Errors indicate an unwanted condition occurring in your application. Let’s say you want to create a temporary directory where you can store some files for your application, but the directory’s creation fails. This is an unwanted condition and is therefore represented using an error.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"ioutil"

)

func main() {

dir, err := ioutil.TempDir("", "temp")

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("failed to create temp dir: %v", err)

}

}

Golang represents errors using the built-in error type, which we will look at closer in the next section. The error is often returned as a second argument of the function, as shown in the example above. Here the TempDir function returns the name of the directory as well as an error variable.

Creating custom errors

As already mentioned errors are represented using the built-in error interface type, which has the following definition:

type error interface {

Error() string

}

The interface contains a single method Error() that returns an error message as a string. Every type that implements the error interface can be used as an error. When printing the error using methods like fmt.Println the Error() method is automatically called by Golang.

There are multiple ways of creating custom error messages in Golang, each with its own advantages and disadvantages.

String-based errors

String-based errors can be created using two out-of-the-box options in Golang and are used for simple errors that just need to return an error message.

err := errors.New("math: divided by zero")

The errors.New() method can be used to create new errors and takes the error message as its only parameter.

err2 := fmt.Errorf("math: %g cannot be divided by zero", x)

fmt.Errorf on the other hand also provides the ability to add formatting to your error message. Above you can see that a parameter can be passed which will be included in the error message.

Custom error with data

You can create your own error type by implementing the Error() function defined in the error interface on your struct. Here is an example:

type PathError struct {

Path string

}

func (e *PathError) Error() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("error in path: %v", e.Path)

}

The PathError implements the Error() function and therefore satisfies the error interface. The implementation of the Error() function now returns a string with the path of the PathError struct. You can now use PathError whenever you want to throw an error.

Here is an elementary example:

package main

import(

"fmt"

)

type PathError struct {

Path string

}

func (e *PathError) Error() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("error in path: %v", e.Path)

}

func throwError() error {

return &PathError{Path: "/test"}

}

func main() {

err := throwError()

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

}

}

You can also check if the error has a specific type using either an if or switch statement:

if err != nil {

switch e := err.(type) {

case *PathError :

// Do something with the path

default:

log.Println(e)

}

}

This will allow you to extract more information from your errors because you can then call all functions that are implemented on the specific error type. For example, if the PathError had a second method called GetInfo you could call it like this.

e.GetInfo()

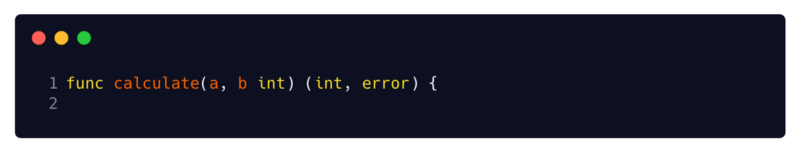

Error handling in functions

Now that you know how to create your own custom errors and extract as much information as possible from errors let’s take a look at how you can handle errors in functions.

Most of the time errors are not directly handled in functions but are returned as a return value instead. Here we can take advantage of the fact that Golang supports multiple return values for a function. Thus you can return your error alongside the normal result — errors are always returned as the last argument — of the function as follows:

func divide(a, b float64) (float64, error) {

if b == 0 {

return 0.0, errors.New("cannot divide through zero")

}

return a/b, nil

}

The function call will then look similar to this:

func main() {

num, err := divide(100, 0)

if err != nil {

fmt.Printf("error: %s", err.Error())

} else {

fmt.Println("Number: ", num)

}

}

If the returned error is not nil it usually means that there is a problem and you need to handle the error appropriately. This can mean that you use some kind of log message to warn the user, retry the function until it works or close the application entirely depending on the situation. The only drawback is that Golang does not enforce handling the retuned errors, which means that you could just ignore handling errors completely.

Take the following code for example:

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

)

func main() {

num2, _ := divide(100, 0)

fmt.Println("Number: ", num2)

}

The so-called blank identifier is used as an anonymous placeholder and therefore provides a way to ignore values in an assignment and avoid compiler errors in the process. But remember that using the blank identifier instead of probably handling errors is dangerous and should not be done if it can be avoided.

Defer, panic and recover

Go does not have exceptions like many other programming languages, including Java and Javascript but has a comparable mechanism know as ,,Defer, panic and recover». Still the use-cases of panic and recover are very different from exceptions in other programming languages as they should only be used in unexpected and unrecoverable situations.

Defer

A defer statement is a mechanism used to defer a function by putting it into an executed stack once the function that contains the defer statement has finished, either normally by executing a return statement or abnormally panicking. Deferred functions will then be executed in reverse order in which they were deferred.

Take the following function for example:

func processHTML(url string) error {

resp, err := http.Get(url)

if err != nil {

return err

}

ct := resp.Header.Get("Content-Type")

if ct != "text/html" && !strings.HasPrefix(ct, "text/html;") {

resp.Body.Close()

return fmt.Errorf("%s has content type %s which does not match text/html", url, ct)

}

doc, err := html.Parse(resp.Body)

resp.Body.Close()

// ... Process HTML ...

return nil

}

Here you can notice the duplicated resp.Body.Close call, which ensures that the response is properly closed. Once functions grow more complex and have more errors that need to be handled such duplications get more and more problematic to maintain.

Since deferred calls get called once the function has ended, no matter if it succeeded or not it can be used to simplify such calls.

func processHTMLDefer(url string) error {

resp, err := http.Get(url)

if err != nil {

return err

}

defer resp.Body.Close()

ct := resp.Header.Get("Content-Type")

if ct != "text/html" && !strings.HasPrefix(ct, "text/html;") {

return fmt.Errorf("%s has content type %s which does not match text/html", url, ct)

}

doc, err := html.Parse(resp.Body)

// ... Process HTML ...

return nil

}

All deferred functions are executed in reverse order in which they were deferred when the function finishes.

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func main() {

first()

}

func first() {

defer fmt.Println("first")

second()

}

func second() {

defer fmt.Println("second")

third()

}

func third() {

defer fmt.Println("third")

}

Here is the result of running the above program:

third

second

first

Panic

A panic statement signals Golang that your code cannot solve the current problem and it therefore stops the normal execution flow of your code. Once a panic is called, all deferred functions are executed and the program crashes with a log message that includes the panic values (usually an error message) and a stack trace.

As an example Golang will panic when a number is divided by zero.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

divide(5)

}

func divide(x int) {

fmt.Printf("divide(%d) n", x+0/x)

divide(x-1)

}

Once the divide function is called using zero, the program will panic, resulting in the following output.

panic: runtime error: integer divide by zero

goroutine 1 [running]:

main.divide(0x0)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:16 +0xe6

main.divide(0x1)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:17 +0xd6

main.divide(0x2)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:17 +0xd6

main.divide(0x3)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:17 +0xd6

main.divide(0x4)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:17 +0xd6

main.divide(0x5)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:17 +0xd6

main.main()

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:11 +0x31

exit status 2

You can also use the built-in panic function to panic in your own programms. A panic should mostly only be used when something happens that the program didn’t expect and cannot handle.

func getArguments() {

if len(os.Args) == 1 {

panic("Not enough arguments!")

}

}

As already mentioned, deferred functions will be executed before terminating the application, as shown in the following example.

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func main() {

accessSlice([]int{1,2,5,6,7,8}, 0)

}

func accessSlice(slice []int, index int) {

fmt.Printf("item %d, value %d n", index, slice[index])

defer fmt.Printf("defer %d n", index)

accessSlice(slice, index+1)

}

Here is the output of the programm:

item 0, value 1

item 1, value 2

item 2, value 5

item 3, value 6

item 4, value 7

item 5, value 8

defer 5

defer 4

defer 3

defer 2

defer 1

defer 0

panic: runtime error: index out of range [6] with length 6

goroutine 1 [running]:

main.accessSlice(0xc00011df48, 0x6, 0x6, 0x6)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:29 +0x250

main.accessSlice(0xc00011df48, 0x6, 0x6, 0x5)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:31 +0x1eb

main.accessSlice(0xc00011df48, 0x6, 0x6, 0x4)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:31 +0x1eb

main.accessSlice(0xc00011df48, 0x6, 0x6, 0x3)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:31 +0x1eb

main.accessSlice(0xc00011df48, 0x6, 0x6, 0x2)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:31 +0x1eb

main.accessSlice(0xc00011df48, 0x6, 0x6, 0x1)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:31 +0x1eb

main.accessSlice(0xc00011df48, 0x6, 0x6, 0x0)

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:31 +0x1eb

main.main()

C:/Users/gabriel/articles/Golang Error handling/Code/panic/main.go:9 +0x99

exit status 2

Recover

In some rare cases panics should not terminate the application but be recovered instead. For example, a socket server that encounters an unexpected problem could report the error to the clients and then close all connections rather than leaving the clients wondering what just happened.

Panics can therefore be recovered by calling the built-in recover function within a deferred function in the function that is panicking. Recover will then end the current state of panic and return the panic error value.

package main

import "fmt"

func main(){

accessSlice([]int{1,2,5,6,7,8}, 0)

}

func accessSlice(slice []int, index int) {

defer func() {

if p := recover(); p != nil {

fmt.Printf("internal error: %v", p)

}

}()

fmt.Printf("item %d, value %d n", index, slice[index])

defer fmt.Printf("defer %d n", index)

accessSlice(slice, index+1)

}

As you can see after adding a recover function to the function we coded above the program doesn’t exit anymore when the index is out of bounds by recovers instead.

Output:

item 0, value 1

item 1, value 2

item 2, value 5

item 3, value 6

item 4, value 7

item 5, value 8

internal error: runtime error: index out of range [6] with length 6defer 5

defer 4

defer 3

defer 2

defer 1

defer 0

Recovering from panics can be useful in some cases, but as a general rule you should try to avoid recovering from panics.

Error wrapping

Golang also allows errors to wrap other errors which provides the functionality to provide additional context to your error messages. This is often used to provide specific information like where the error originated in your program.

You can create wrapped errors by using the %w flag with the fmt.Errorf function as shown in the following example.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

"os"

)

func main() {

err := openFile("non-existing")

if err != nil {

fmt.Printf("error running program: %s n", err.Error())

}

}

func openFile(filename string) error {

if _, err := os.Open(filename); err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("error opening %s: %w", filename, err)

}

return nil

}

The output of the application would now look like the following:

error running program: error opening non-existing: open non-existing: no such file or directory

As you can see the application prints both the new error created using fmt.Errorf as well as the old error message that was passed to the %w flag. Golang also provides the functionality to get the old error message back by unwrapping the error using errors.Unwrap.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

"os"

)

func main() {

err := openFile("non-existing")

if err != nil {

fmt.Printf("error running program: %s n", err.Error())

// Unwrap error

unwrappedErr := errors.Unwrap(err)

fmt.Printf("unwrapped error: %v n", unwrappedErr)

}

}

func openFile(filename string) error {

if _, err := os.Open(filename); err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("error opening %s: %w", filename, err)

}

return nil

}

As you can see the output now also displays the original error.

error running program: error opening non-existing: open non-existing: no such file or directory

unwrapped error: open non-existing: no such file or directory

Errors can be wrapped and unwrapped multiple times, but in most cases wrapping them more than a few times does not make sense.

Casting Errors

Sometimes you will need a way to cast between different error types to for example, access unique information that only that type has. The errors.As function provides an easy and safe way to do so by looking for the first error in the error chain that fits the requirements of the error type. If no match is found the function returns false.

Let’s look at the official errors.As docs example to better understand what is happening.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

"io/fs"

"os"

)

func main(){

// Casting error

if _, err := os.Open("non-existing"); err != nil {

var pathError *os.PathError

if errors.As(err, &pathError) {

fmt.Println("Failed at path:", pathError.Path)

} else {

fmt.Println(err)

}

}

}

Here we try to cast our generic error type to os.PathError so we can access the Path variable that that specific error contains.

Another useful functionality is checking if an error has a specific type. Golang provides the errors.Is function to do exactly that. Here you provide your error as well as the particular error type you want to check. If the error matches the specific type the function will return true, if not it will return false.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

"io/fs"

"os"

)

func main(){

// Check if error is a specific type

if _, err := os.Open("non-existing"); err != nil {

if errors.Is(err, fs.ErrNotExist) {

fmt.Println("file does not exist")

} else {

fmt.Println(err)

}

}

}

After checking, you can adapt your error message accordingly.

Sources

- Golang Blog — Working with Errors in Go 1.13

- The Go Programming language book

- Golang Blog — Defer, Panic, and Recover

- LogRocket — Error handling in Golang

- GolangByExample — Wrapping and Un-wrapping of error in Go

- Golang Documentation — Package errors

Conclusion

You made it all the way until the end! I hope this article helped you understand the basics of Go error handling and why it is an essential topic in application/software development.

If you have found this helpful, please consider recommending and sharing it with other fellow developers and subscribing to my newsletter. If you have any questions or feedback, let me know using my contact form or contact me on Twitter.

Привет, хабровчане! Уже сегодня в ОТУС стартует курс «Разработчик Golang» и мы считаем это отличным поводом, чтобы поделиться еще одной полезной публикацией по теме. Сегодня поговорим о подходе Go к ошибкам. Начнем!

Освоение прагматической обработки ошибок в вашем Go-коде

Этот пост является частью серии «Перед тем как приступать к Go», где мы исследуем мир Golang, делимся советами и идеями, которые вы должны знать при написании кода на Go, чтобы вам не пришлось набивать собственные шишки.

Я предполагаю, что у вас уже имеется хотя бы базовый опыт работы с Go, но если вы чувствуете, что в какой-то момент вы столкнулись с незнакомым обсуждаемым материалом, не стесняйтесь делать паузу, исследовать тему и возвращаться.

Теперь, когда мы расчистили себе путь, поехали!

Подход Go к обработке ошибок — одна из самых спорных и неправильно используемых фич. В этой статье вы узнаете подход Go к ошибкам, и поймете, как они работают “под капотом”. Вы изучите несколько различных подходов, рассмотрите исходный код Go и стандартную библиотеку, чтобы узнать, как обрабатываются ошибки и как с ними работать. Вы узнаете, почему утверждения типа (Type Assertions) играют важную роль в их обработке, и увидите предстоящие изменения в обработке ошибок, которые планируется ввести в Go 2.

Вступление

Сперва-наперво: ошибки в Go не являются исключениями. Дэйв Чейни написал эпический блогпост об этом, поэтому я отсылаю вас к нему и резюмирую: на других языках вы не можете быть уверены, может ли функция вызвать исключение или нет. Вместо генерации исключений функции Go поддерживают множественные возвращаемые значения, и по соглашению эта возможность обычно используется для возврата результата функции наряду с переменной ошибки.

Если по какой-то причине ваша функция может дать сбой, вам, вероятно, следует вернуть из нее предварительно объявленный error-тип. По соглашению, возврат ошибки сигнализирует вызывающей стороне о проблеме, а возврат nil не считается ошибкой. Таким образом, вы дадите вызывающему понять, что возникла проблема, и ему нужно разобраться с ней: кто бы ни вызвал вашу функцию, он знает, что не должен полагаться на результат до проверки на наличие ошибки. Если ошибка не nil, он обязан проверить ее и обработать (логировать, возвращать, обслуживать, вызвать какой-либо механизм повторной попытки/очистки и т. д.).

(3 // обработка ошибки

5 // продолжение)

Эти фрагменты очень распространены в Go, и некоторые рассматривают их в качестве шаблонного кода. Компилятор рассматривает неиспользуемые переменные как ошибки компиляции, поэтому, если вы не собираетесь проверять наличие ошибок, вы должны назначить их пустому идентификатору. Но как бы удобно это ни было, ошибки не следует игнорировать.

( 4 // игнорирование ошибок небезопасно, и вы не должны полагаться на результат прежде, чем проверите наличие ошибок)

результату нельзя доверять до проверки на наличие ошибок

Возврат ошибки вместе с результатами, наряду со строгой системой типов Go, значительно усложняет написание забагованного кода. Вы всегда должны полагать, что значение функции повреждено, если только вы не проверили ошибку, которую она возвратила, и, присваивая ошибку пустому идентификатору, вы явно игнорируете, что значение вашей функции может быть повреждено.

Пустой идентификатор темен и полон ужасов.

У Go действительно есть panic и recover механизмы, которые также описаны в другом подробном посте в блоге Go. Но они не предназначены для имитации исключений. По словам Дейва, «Когда вы паникуете в Go — вы действительно паникуете: это не проблема кого-то другого, это уже геймовер». Они фатальны и приводят к сбою в вашей программе. Роб Пайк придумал поговорку «Не паникуйте», которая говорит сама за себя: вам, вероятно, следует избегать эти механизмы и вместо них возвращать ошибки.

«Ошибки — значения».

«Не просто проверяйте наличие ошибок, а элегантно их обрабатывайте»

«Не паникуйте»

все поговорки Роба Пайка

Под капотом

Интерфейс ошибки

Под капотом тип error — это простой интерфейс с одним методом, и если вы с ним не знакомы, я настоятельно рекомендую просмотреть этот пост в официальном блоге Go.

интерфейс error из исходного кода

Свои собственные ошибки реализовать не сложно. Существуют различные подходы к пользовательским структурам, реализующим метод Error() string . Любая структура, реализующая этот единственный метод, считается допустимым значением ошибки и может быть возвращена как таковая.

Давайте рассмотрим несколько таких подходов.

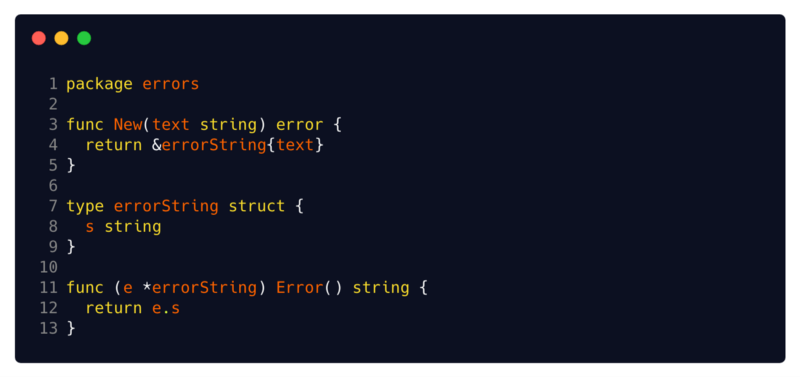

Встроенная структура errorString

Наиболее часто используемая и широко распространенная реализация интерфейса ошибок — это встроенная структура errorString . Это самая простая реализация, о которой вы только можете подумать.

Источник: исходный код Go

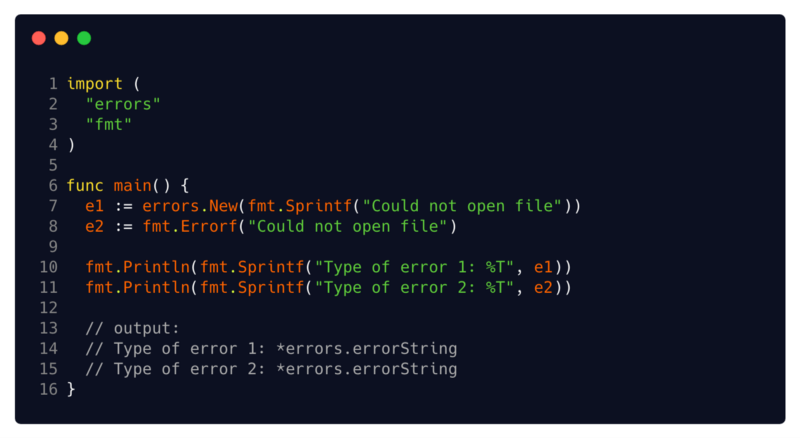

Вы можете лицезреть ее упрощенную реализацию здесь. Все, что она делает, это содержит string, и эта строка возвращается методом Error. Эта стринговая ошибка может быть нами отформатирована на основе некоторых данных, скажем, с помощью fmt.Sprintf. Но кроме этого, она не содержит никаких других возможностей. Если вы применили errors.New или fmt.Errorf, значит вы уже использовали ее.

(13// вывод:)

попробуйте

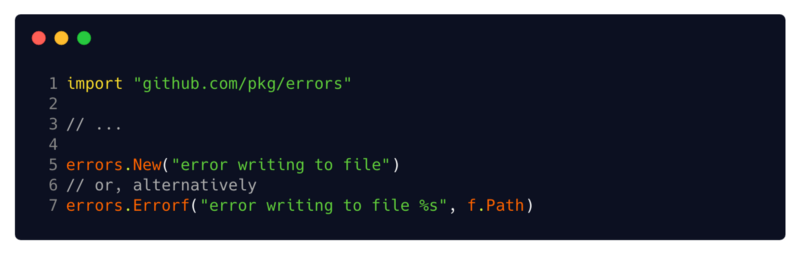

github.com/pkg/errors

Другой простой пример — пакет pkg/errors. Не путать со встроенным пакетом errors, о котором вы узнали ранее, этот пакет предоставляет дополнительные важные возможности, такие как обертка ошибок, развертка, форматирование и запись стек-трейса. Вы можете установить пакет, запустив go get github.com/pkg/errors.

В тех случаях, когда вам нужно прикрепить стек-трейс или необходимую информацию об отладке к вашим ошибкам, использование функций New или Errorf этого пакета предоставляет ошибки, которые уже записываются в ваш стек-трейс, и вы так же можете прикрепить простые метаданные, используя его возможности форматирования. Errorf реализует интерфейс fmt.Formatter, то есть вы можете отформатировать его, используя руны пакета fmt ( %s, %v, %+v и т. д.).

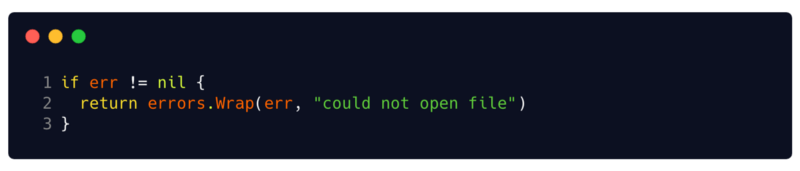

(//6 или альтернатива)

Этот пакет также представляет функции errors.Wrap и errors.Wrapf. Эти функции добавляют контекст к ошибке с помощью сообщения и стек-трейса в том месте, где они были вызваны. Таким образом, вместо простого возврата ошибки, вы можете обернуть ее контекстом и важными отладочными данными.

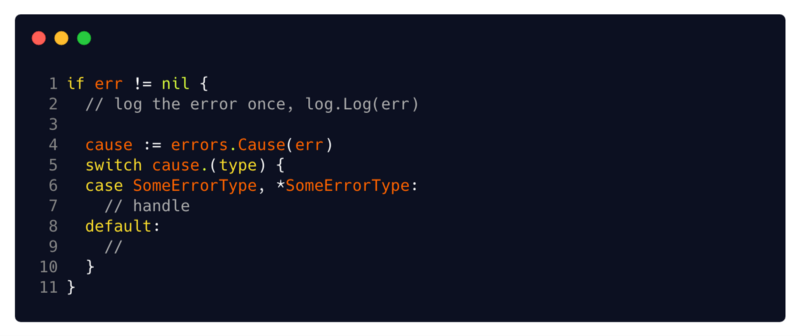

Обертки ошибок другими ошибками поддерживают Cause() error метод, который возвращает их внутреннюю ошибку. Кроме того, они могут использоваться сerrors.Cause(err error) error функцией, которая извлекает основную внутреннюю ошибку в оборачивающей ошибке.

Работа с ошибками

Утверждение типа

Утверждения типа (Type Assertion) играют важную роль при работе с ошибками. Вы будете использовать их для извлечения информации из интерфейсного значения, а поскольку обработка ошибок связана с пользовательскими реализациями интерфейса error, реализация утверждений на ошибках является очень удобным инструментом.

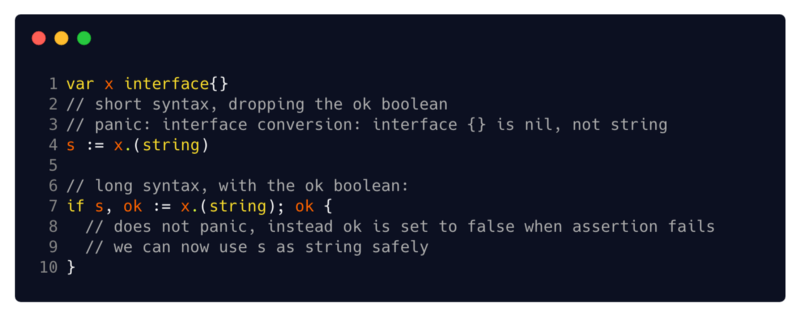

Его синтаксис одинаков для всех его целей — x.(T), если x имеет тип интерфейса. x.(T) утверждает, что x не равен nil и что значение, хранящееся в x, относится к типу T. В следующих нескольких разделах мы рассмотрим два способа использования утверждений типа — с конкретным типом T и с интерфейсом типа T.

(2//сокращенный синтаксис, пропускающий логическую переменную ok

3//паника: преобразование интерфейса: интерфейс {} равен nil, а не string

6//удлиненный синтаксис с логической переменной ok

8//не паникует, вместо этого присваивает ok false, когда утверждение ложно

9// теперь мы можем безопасно использовать s как строку)

песочница: panic при укороченном синтаксисе, безопасный удлинённый синтаксис

Дополнительное примечание, касающееся синтаксиса: утверждение типа может использоваться как с укороченным синтаксисом (который паникует при неудачном утверждении), так и с удлиненным синтаксисом (который использует логическое значение OK для указания успеха или неудачи). Я всегда рекомендую брать удлиненный вместо укороченного, так как я предпочитаю проверять переменную OK, а не разбираться с паникой.

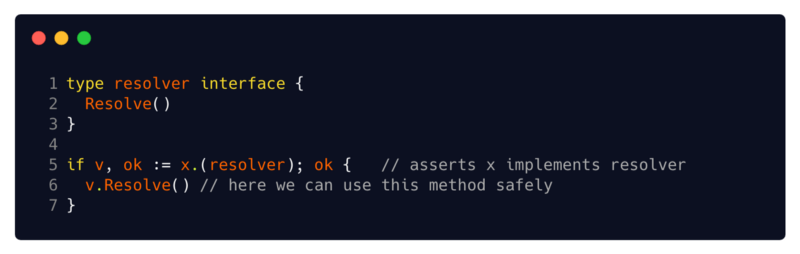

Утверждение с интерфейсом типа T

Выполнение утверждения типа x.(T) с интерфейсом типа T подтверждает, что x реализует интерфейс T. Таким образом, вы можете гарантировать, что интерфейсное значение реализует интерфейс, и только если это так, вы сможете использовать его методы.

(5…// утверждаем, что x реализует интерфейс resolver

6…// здесь мы уже можем безопасно использовать этот метод)

Чтобы понять, как это можно использовать, давайте снова взглянем на pkg/errors. Вы уже знаете этот пакет ошибок, так что давайте углубимся в errors.Cause(err error) error функцию.

Эта функция получает ошибку и извлекает самую внутреннюю ошибку, которую та переносит (ту, которая уже не служит оберткой для другой ошибки). Это может показаться примитивным, но есть много замечательных вещей, которые вы можете извлечь из этой реализации:

источник: pkg/errors

Функция получает значение ошибки, и она не может предполагать, что получаемый ею err аргумент является ошибкой-оберткой (поддерживаемой Cause методом). Поэтому перед вызовом метода Cause необходимо убедиться, что вы имеете дело с ошибкой, которая реализует этот метод. Выполняя утверждение типа в каждой итерации цикла for, вы можете убедиться, что cause переменная поддерживает метод Cause, и может продолжать извлекать из него внутренние ошибки до тех пор, пока не найдете ошибку, у которой нет Cause.

Создавая простой локальный интерфейс, содержащий только те методы, которые вам нужны, и применяя на нем утверждение, ваш код отделен от других зависимостей. Полученный вами аргумент не обязательно должен быть известной структурой, он просто должен быть ошибкой. Любой тип, реализующий методы Error и Cause, подойдет. Таким образом, если вы реализуете Cause метод в своем типе ошибки, вы можете использовать эту функцию с ним без замедлений.

Однако следует помнить об одном небольшом недостатке: интерфейсы могут изменяться, поэтому вам следует тщательно поддерживать код, чтобы ваши утверждения не нарушались. Не забудьте определить свои интерфейсы там, где вы их используете, поддерживать их стройными и аккуратными, и у вас все будет хорошо.

Наконец, если вам нужен только один метод, иногда удобнее сделать утверждение на анонимном интерфейсе, содержащем только метод, на который вы полагаетесь, т. е. v, ok := x.(interface{ F() (int, error) }). Использование анонимных интерфейсов может помочь отделить ваш код от возможных зависимостей и защитить его от возможных изменений в интерфейсах.

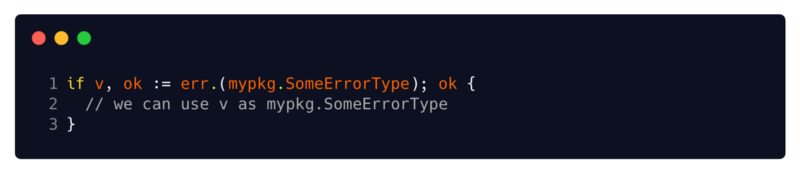

Утверждение с конкретным типом T и Type Switch

Я предваряю этот раздел введением двух похожих шаблонов обработки ошибок, которые страдают от нескольких недостатков и ловушек. Это не значит, что они не распространенные. Оба они могут быть удобными инструментами в небольших проектах, но они плохо масштабируются.

Первый — это второй вариант утверждения типа: выполняется утверждение типа x.(T) с конкретным типом T. Он утверждает, что значение x имеет тип T, или оно может быть преобразовано в тип T.

(2//мы можем использовать v как mypkg.SomeErrorType)

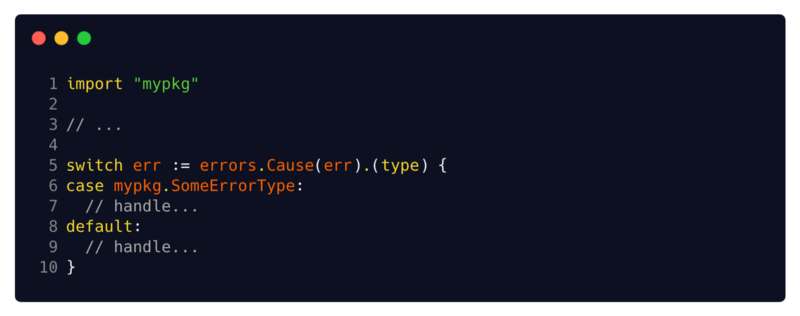

Другой — это шаблон Type Switch. Type Switch объединяют оператор switch с утверждением типа, используя зарезервированное ключевое слово type. Они особенно распространены в обработке ошибок, где знание основного типа переменной ошибки может быть очень полезным.

(3// обработка…

5// обработка…)

Большим недостатком обоих подходов является то, что оба они приводят к связыванию кода со своими зависимостями. Оба примера должны быть знакомы со структурой SomeErrorType (которая, очевидно, должна быть экспортирована) и должны импортировать пакет mypkg.

В обоих подходах при обработке ваших ошибок вы должны быть знакомы с типом и импортировать его пакет. Ситуация усугубляется, когда вы имеете дело с ошибками в обертках, где причиной ошибки может быть ошибка, возникшая из-за внутренней зависимости, о которой вы не знаете и не должны знать.

(7// обработка…

9// обработка…)

Type Switch различают *MyStruct и MyStruct. Поэтому, если вы не уверены, имеете ли вы дело с указателем или фактическим экземпляром структуры, вам придется предоставить оба варианта. Более того, как и в случае с обычными switch, кейсы в Type Switch не проваливаются, но в отличие от обычных Type Switch, использование fallthrough запрещено в Type Switch, поэтому вам придется использовать запятую и предоставлять обе опции, что легко забыть.

Подытожим

Вот и все! Теперь вы знакомы с ошибками и должны быть готовы к устранению любых ошибок, которые ваше приложение Go может выбросить (или фактически вернуть) на ваш путь!

Оба пакета errors представляют простые, но важные подходы к ошибкам в Go, и, если они удовлетворяют вашим потребностям, они являются отличным выбором. Вы можете легко реализовать свои собственные структуры ошибок и пользоваться преимуществами обработки ошибок Go, комбинируя их с pkg/errors.

Когда вы масштабируете простые ошибки, правильное использование утверждений типа может быть отличным инструментом для обработки различных ошибок. Либо с помощью Type Switch, либо путем утверждения поведения ошибки и проверки интерфейсов, которые она реализует.

Что дальше?

Обработка ошибок в Go сейчас очень актуальна. Теперь, когда вы получили основы, вам может быть интересно, что ждет нас в будущем для обработки ошибок Go!

В следующей версии Go 2 этому уделяется много внимания, и вы уже можете взглянуть на черновой вариант. Кроме того, во время dotGo 2019 Марсель ван Лохуизен провел отличную беседу на тему, которую я просто не могу не рекомендовать — «Значения ошибок GO 2 уже сегодня».

Очевидно, есть еще множество подходов, советов и хитростей, и я не могу включить их все в один пост! Несмотря на это, я надеюсь, что вам он понравился, и я увижу вас в следующем выпуске серии «Перед тем как приступать к Go»!

А теперь традиционно ждем ваши комментарии.

Errors are a core part of almost every programming language, and how we handle them is a critical part of software development. One of the things that I really enjoy about programming in Go is the implementation of errors and how they are treated: Effective without having unnecessary complexity. This blog post will dive into what errors are and how they can be wrapped (and unwrapped).

What are errors?

Let’s start from the beginning. It’s common to see an error getting returned and handled from a function:

1 2 3 |

func myFunction() error { // ... } |

But what exactly is an error? It is one of the simplest interfaces defined in Go (source code reference):

1 2 3 |

type error interface { Error() string } |

It has a single function Error that takes no parameters and returns a string. That’s it! That’s all there is to implementing the error interface. We’ll see later on how we can implement error to create our own custom error types.

Creating errors

Most of the time you’ll rely on creating errors through one of two ways:

1 |

fmt.Errorf("error doing something") |

Or:

1 |

errors.New("error doing something") |

The former is used when you want to use formatting with the typical fmt verbs. If you aren’t wrapping an error (more on this below) then fmt.Errorf effectively makes a call to errors.New (source code reference). So if you’re not wrapping an error or using any additional formatting then it’s a personal preference.

What do these non-wrapped errors look like? Breaking into the debugger we can analyze them:

1 2 3 |

(dlv) p err1

error(*errors.errorString) *{

s: "error doing something",}

|

The concrete type is *errors.errorString. Let’s take a look at this Go struct in the errors package (source code reference):

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

type errorString struct { s string } func (e *errorString) Error() string { return e.s } |

errorString is a simple implementation having a single string field and because this implements the error interface it defines the Error function, which just returns the struct’s string.

Creating custom error types

What if we want to create custom errors with certain pieces of information? Now that we understand what an error actually is (by implementing the error interface) we can define our own:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

type myCustomError struct { errorMessage string someRandomValue int } func (e *myCustomError) Error() string { return fmt.Sprintf("Message: %s - Random value: %d", e.errorMessage, e.someRandomValue) } |

And we can use them just like any other error in Go:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

func someFunction() error { return &myCustomError{ errorMessage: "hello world", someRandomValue: 13, } } func main() { err := someFunction() fmt.Printf("%v", err) } |

The output of running this code is expected:

1 |

Message: hello world - Random value: 13 |

Error wrapping

In Go it is common to return errors and then keep bubbling that up until it is handled properly (exiting, logging, etc.). Consider this example:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

func doAnotherThing() error { return errors.New("error doing another thing") } func doSomething() error { err := doAnotherThing() return fmt.Errorf("error doing something: %v", err) } func main() { err := doSomething() fmt.Println(err) } |

main makes a call to doSomething, which calls doAnotherThing and takes its error.

Note: It’s common to have error handling with if err != nil ... but I wanted to keep this example as small as possible.

Typically you want to preserve the context of your inner errors (in this case “error doing another thing”) so you might try to do a superficial wrap with fmt.Errorf and the %v verb. In fact, the output seems reasonable:

1 |

error doing something: error doing another thing |

But outside of wrapping the error messages, we’ve lost the inner errors themselves effectively. If we were to analyze err in main, we’d see this:

1 2 3 |

(dlv) p err

error(*errors.errorString) *{

s: "error doing something: error doing another thing",}

|

Most of the time that is typically fine. A superficially wrapper error is ok for logging and troubleshooting. But what happens if you need to programmatically test for a particular error or treat an error as a custom one? With the above approach, that is extremely complicated and error-prone.

The solution to that challenge is by wrapping your errors. To wrap your errors you would use fmt.Errorf with the %w verb. Let’s modify the single line of code in the above example:

1 |

return fmt.Errorf("error doing something: %w", err) |

Now let’s inspect the returned error in main:

1 2 3 4 5 |

(dlv) p err

error(*fmt.wrapError) *{

msg: "error doing something: error doing another thing",

err: error(*errors.errorString) *{

s: "error doing another thing",},}

|

We’re no longer getting the type *errors.errorString. Now we have the type *fmt.wrapError. Let’s take a look at how Go defines wrapError (source code reference):

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

type wrapError struct { msg string err error } func (e *wrapError) Error() string { return e.msg } func (e *wrapError) Unwrap() error { return e.err } |

This adds a couple of new things:

errfield with the typeerror(this will be the inner/wrapped error)Unwrapmethod that gives us access to the inner/wrapped error

This extra wiring gives us a lot of powerful capabilities when dealing with wrapped errors.

Error equality

One of the scenarios that error wrapping unlocks is a really elegant way to test if an error or any inner/wrapped errors are a particular error. We can do that with the errors.Is function:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 |

var errAnotherThing = errors.New("error doing another thing") func doAnotherThing() error { return errAnotherThing } func doSomething() error { err := doAnotherThing() return fmt.Errorf("error doing something: %w", err) } func main() { err := doSomething() if errors.Is(err, errAnotherThing) { fmt.Println("Found error!") } fmt.Println(err) } |

I changed the code of doAnotherThing to return a particular error (errAnotherThing). Even though this error gets wrapped in doSomething, we’re still able to concisely test if the returned error is or wraps errAnotherThing with errors.Is.

errors.Is essentially just loops through the different layers of the error and unwraps, testing to see if it is equal to the target error (source code reference).

Specific error handling

Another scenario is if you have a particular type of error that you want to handle, even if it is wrapped. Using a variation of an earlier example:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 |

type myCustomError struct { errorMessage string someRandomValue int } func (e *myCustomError) Error() string { return fmt.Sprintf("Message: %s - Random value: %d", e.errorMessage, e.someRandomValue) } func doAnotherThing() error { return &myCustomError{ errorMessage: "hello world", someRandomValue: 13, } } func doSomething() error { err := doAnotherThing() return fmt.Errorf("error doing something: %w", err) } func main() { err := doSomething() var customError *myCustomError if errors.As(err, &customError) { fmt.Printf("Custom error random value: %dn", customError.someRandomValue) } fmt.Println(err) } |

This allows us to handle err in main if it (or any wrapped errors) have a concrete type of *myCustomError. The output of running this code:

1 2 |

Custom error random value: 13 error doing something: Message: hello world - Random value: 13 |

Summary

Understanding how errors and error wrapping in Go can go a really long way in implementing them in the best possible way. Using them “the Go way” can lead to code that is easier to maintain and troubleshoot. Enjoy!