Содержание

- Grok nginx error log

- Project structure

- Setting up Nginx

- Setting up Logstash

- Running the solution

- Filebeat – a log shipper

- Logstash — swiss-army knife (in this case — for logs)

- Log Data — Nginx log

- GROK pattern primer

- Extract only IP address and timestamp

- What about other logs?

- Parsing the Nginx access log with GROK

- The Setup

- Configure Filebeat

- Configure Logstash

Grok nginx error log

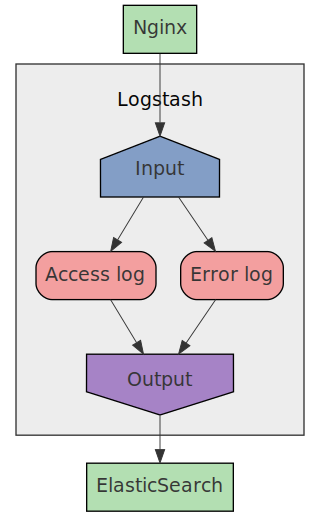

In this article we will setup Nginx to send it’s access and error logs using the syslog standard to Logstash , that stores the logs in ElasticSearch .

The reason why we would want to do this is because:

- It’s easy to setup

- Nginx has builtin support for this

- You don’t need to configure and run a separate program for log collection

We will do this in a step by step manner using Docker and docker-compose locally. And don’t worry, you don’t need to copy all the files manually, there’s a gzipped tar file you can download here (signature) that contains the fully working project.

Project structure

We will setup 3 services using docker-compose :

We will base our Docker containers on the official Docker images for each project. We will use the alpine based images when available to save space.

Let’s start by creating an empty project directory, and then create our docker-compose.yaml file in the root of the project:

Since we will not change the image for ElasticSearch we’ll just use the official image as is.

Setting up Nginx

Let’s setup nginx by first creating the ./nginx directory and then start to work on the nginx config file.

We’ll use a very simple setup where we just serve static files from the directory /nginx/data and then send the access and error logs to Logstash. To be able to find the Logstash container we use Dockers builtin resolver, so we can use the service name we used in docker-compose.yaml .

We’re using a custom log format to include the host so that we can have many nginx instances running and logging to the same Logstash instance.

Also we are tagging the logs so that Logstash will be able to parse the logs correctly depending on whether it’s an access or error log being sent.

Then we’ll just create some static HTML content that will be put in the nginx container:

Now we are ready to create our Dockerfile for the nginx container:

After doing this, our project should have the following structure:

Setting up Logstash

Next we’ll setup Logstash by first creating the ./logstash directory and then start to work on the Logstash configuration file.

We’ll setup Logstash to use:

- 1 input for syslog

- 2 filters to process access and error logs

- 1 output to store the processed logs in ElasticSearch

We will use the Logstash Grok filter plugin to process the incoming nginx logs. Grok is a plugin where you write patterns that extract values from raw data. These patterns are written in a matching language where you define a simplified regular expression and give it a name.

For example, let’s say we want to validate and extract the HTTP method from a string, then we’d write the following grok pattern:

You can then combine these named regular expressions to parse more complex strings. Suppose we want to parse the first line of a HTTP request, that could look like this:

- GET /db HTTP/1.1

- POST /user/login HTTP/1.1

Then we’d define a grok pattern that we write as the text file /etc/logstash/patterns/request_start with the following content:

To use this pattern we simply add a grok configuration to the filter part of the Logstash config file:

We have now told Logstash to match the raw message against our pattern and extract 3 parts of the message. Processing our examples above we’d get the following results:

POST /user/login HTTP/1.1

Here’s how our grok patterns look for nginx access and error logs:

And here’s how we configure Logstash to setup syslog input, our grok patterns and ElasticSearch output:

The parameter program that we base our if-cases on is the tag value that we configured nginx to add to the different types of logs:

The only thing left before we create the Dockerfile is to create the ElasticSearch template to use. This template tells ElasticSearch what fields our different types of log items will have. If you look closely at this template, you’ll notice that all the defined fields exists in the grok filter definition.

Now that we have all of our configurations for Logstash setup, we can create the Dockerfile:

After this, our project should have the following files:

Running the solution

Now we have a complete solution that we just can start with docker-compose . But before we do that we need to increase max_map_count in the Linux kernel, since ElasticSearch needs that:

Then we can just build and start everything:

After all services are ready, we can open up http://localhost:8080 in our web browser and see that HTML-file we created.

After making that request, we can look inside ElasticSearch to make sure there’s log data saved by opening http://localhost:9200/logstash-*/_search/?size=10&pretty=1 in our web browser. We should see something like this:

We have 2 access logs and 1 error log saved in ElasticSearch , with all the different values saved as separate values that can be queried.

Источник

Filebeat – a log shipper

Filebeat is a part of beats family by Elastic. Beats are essentially data shippers. They send chosen data (i.e. logs, metrics, network data, uptime/availabitily monitoring) to a service for further processing or directly into Elasticsearch. Our goal for this post is to work with Nginx access log, so we need Filebeat. When pointed to a log file, Filebeat will read the log lines and forward them to Logstash for further processing. The вЂbeat’ part makes sure that every new line in log file will be sent to Logstash.

Filebeat sits next to the service it’s monitoring, which means you need Filebeat on the same server where Nginx is running. Now for the Filebeat configuration: it’s located in /etc/filebeat/filebeat.yml , written in YAML and is actually straightforward. The configuration file consists of four distinct sections: prospectors, general, output and logging. Under prospectors you have two fields to enter: input_type and paths. Input type can be either log or stdin, and paths are all paths to log files you wish to forward under the same logical group.

Filebeat supports several modules, one of which is Nginx module. This module can parse Nginx access and error logs and ships with a sample dashboard for Kibana (which is a metric visualisation, dashboard and Elasticsearch querying tool). Since we’re on a mission to educate our fellow readers, we’ll leave out this feature in this post.

Logstash — swiss-army knife (in this case — for logs)

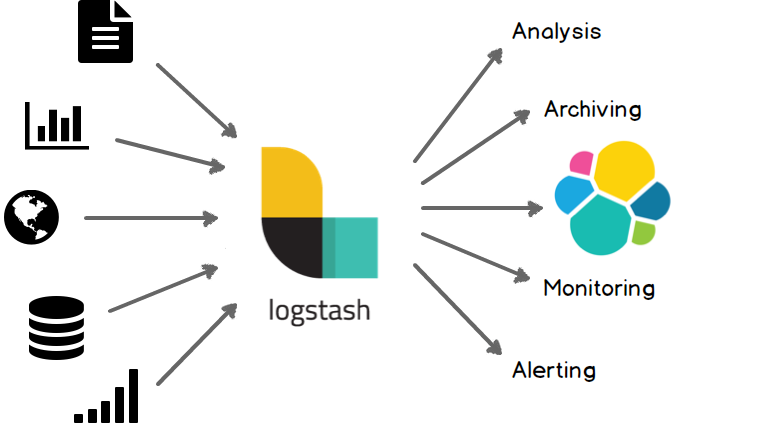

Logstash can be imagined as a processing plant. Or a swiss-army knife. It resembles a virtual space where one can recognize, categorize, restructure, enrich, thus enhance, organize, pack and ship the data again.

Source: Logstash official docs

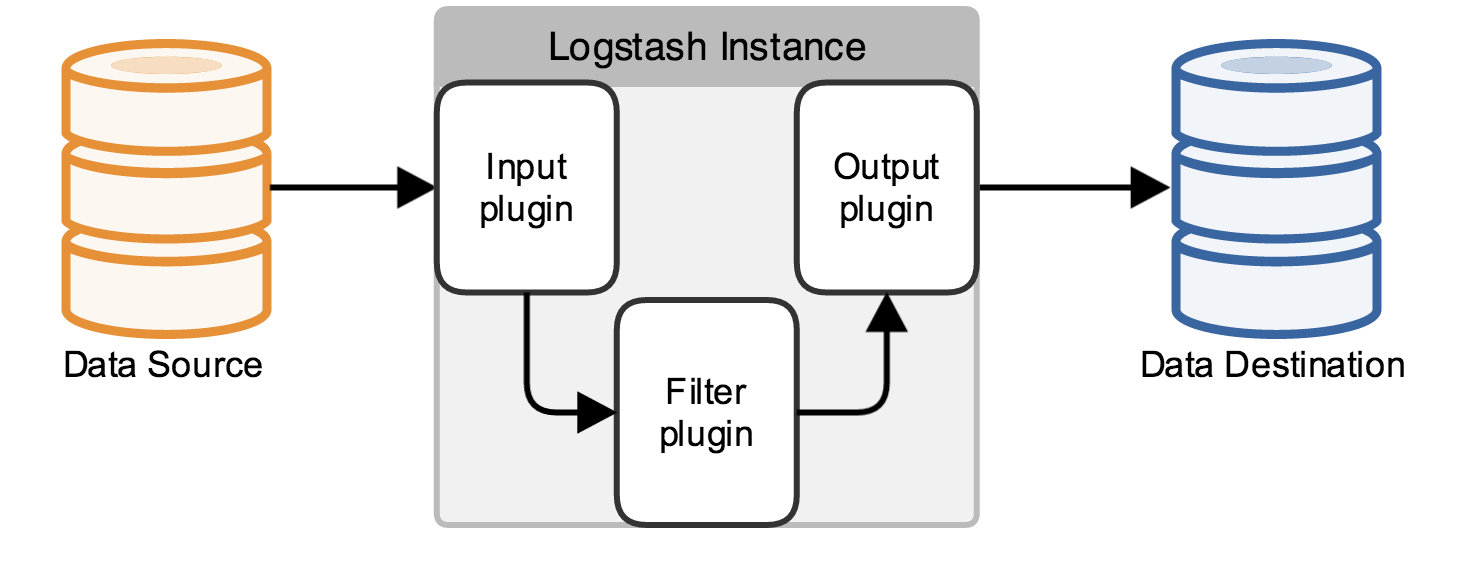

The inside workings of the Logstash reveal a pipeline consisting of three interconnected parts: input, filter and output.

Source: Logstash official docs

If you’re using Ubuntu Linux and have installed through package manager (apt), the configuration file(s) for logstash by default reside in /etc/logstash/conf.d/ directory. The configuration file can be either:

- one file consisting of three distinct parts (input, filter and output),

- smaller configuration files and certain rules then apply about how Logstash combines these into a complete configuration ( input.conf + filter.conf + output.conf ), but we won’t delve into that yet because it leaves the scope of this post.

To achieve the feature of modular configuration, files are usually named with numerical prefix, for example:

Upon starting as a service, Logstash will check the /etc/logstash/conf.d/ location for configuration files and will concatenate all of them by following ascending numerical order found in their names.

Grok is a filter plugin that parses unformatted and flat log data and transforms them into queryable fields and you will most certainly use is for parsing various data.

The definition of word grok is “to understand (something) intuitively or by empathy.” Essentially, grok does exactly that in terms of text – it uses regular expressions to parse text and assign an identifier to them by using the following format: % . The list of grok patterns for Logstash can be found here. There are of course some special characters that can exist in raw data that clash with grok; they must be escaped with a backslash. There is a helpful tool online for debugging and testing your grok pattern.

Logstash has a set of predefined patterns for parsing common applications log formats, such as Apache, MySQL, PostgreSQL, HAProxy, system logs and much more. Users are free to write their own grok patterns if they like.

In this case we’ll work with Nginx log data, configure Filebeat to send this data to Logstash, for which we’ll spend most of the time configuring.

Log Data — Nginx log

Web server logs store valuable usage data — visitor IP address, user agent activity, urls of site visited, HTTP methods used, bytes transferred, various performance parameters (i.e. the time it takes web server to serve some requested content), to name a few.

The flat log file with this valuable data is extremely difficult to read by most humans. Let’s say that a business wants to know where are their most loyal visitors located on the globe and they’ve assigned you with this task. How would you approach this challenge? Or for example, your support department is handling a surge of clients reporting frustratingly slow response time of your web service. How do you filter out which servers are out of the norm by their response time?

Lastly, you may ask yourself: “what does my Nginx log file look like?” If your Nginx configuration is default, then the log format is defined in your /etc/nginx/nginx.conf file as:

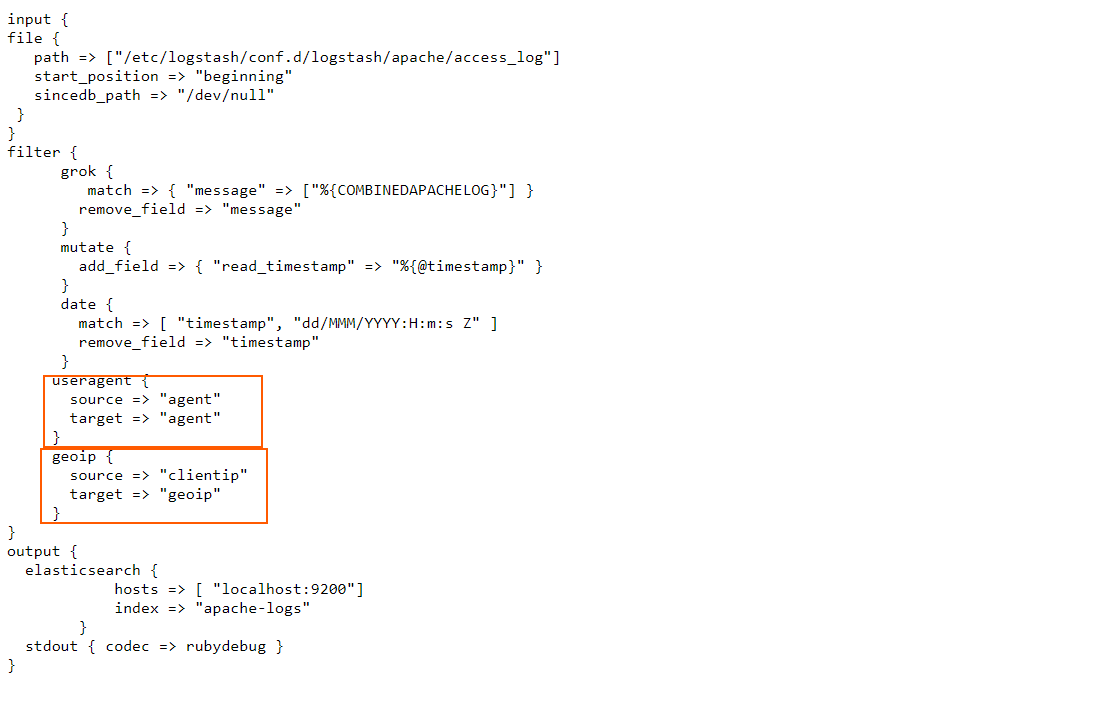

Let’s open the access.log file and check it out. Generated log data with default configuration looks like this:

It may be a good idea to check how is the log format defined in the nginx.conf file before checking the log lines. We’ll use this log line for writing and debugging our grok pattern.

GROK pattern primer

Let’s play: with this one line of Nginx log file, let’s try out some patterns.

Extract only IP address and timestamp

Since we’re currently not interested in knowing information about remote user, we will capture this вЂfield’ and assign it with identifier somedata , but we will disregard the captured content. Also note we had to escape square brackets. Likewise, quotation marks have to be escaped as well (if there are quotation marks in your log file). The end result is this:

What about other logs?

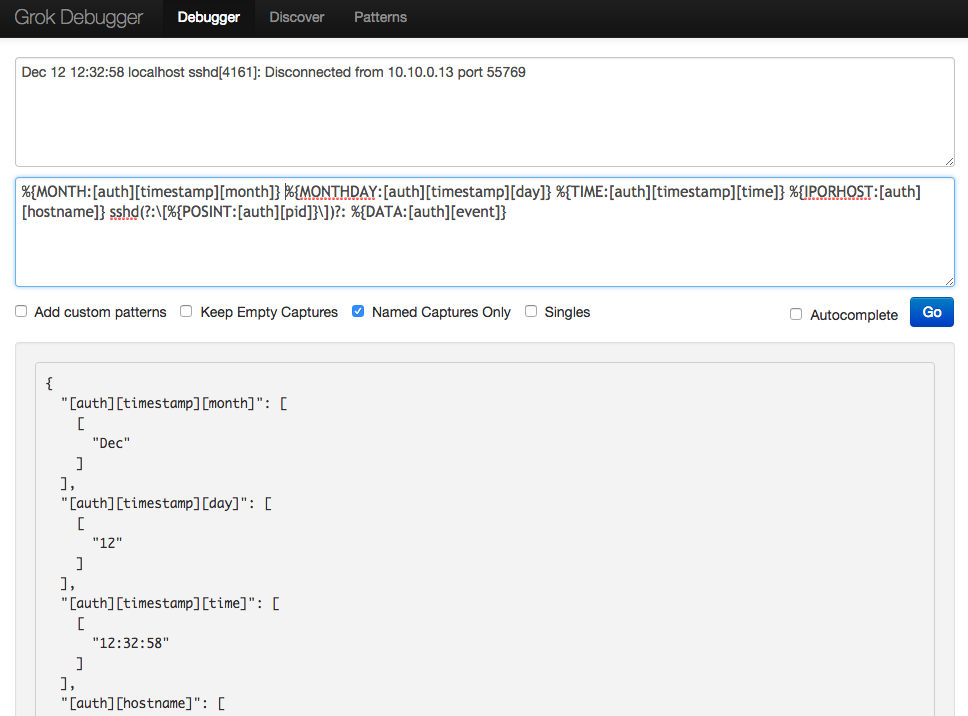

Let’s try parsing one line from /var/log/auth.log file in a similar fashion: The log line is:

Dec 12 12:32:58 localhost sshd[4161]: Disconnected from 10.10.0.13 port 55769

And the pattern is:

The debugger has parsed the data succesfully:

Note that we have different notation for identifiers here. What this means effectively is that we’ve grouped all parsed data into a top-level identifier: auth . The rules are simple: place identifiers in a square brackets and bear in mind that each new bracket represents a new, deeper level structure for the top-level identifier, just like a tree data structure. Here, the top level identifier auth has four second level identifiers: timestamp , hostname , pid and event . Of that four, timestamp has another level down etc.

Sometimes it’s easier for the long run to logically organise identifiers. If you want to know more, Elastic team wrote patterns for auth.log and covered an example for using it here.

Parsing the Nginx access log with GROK

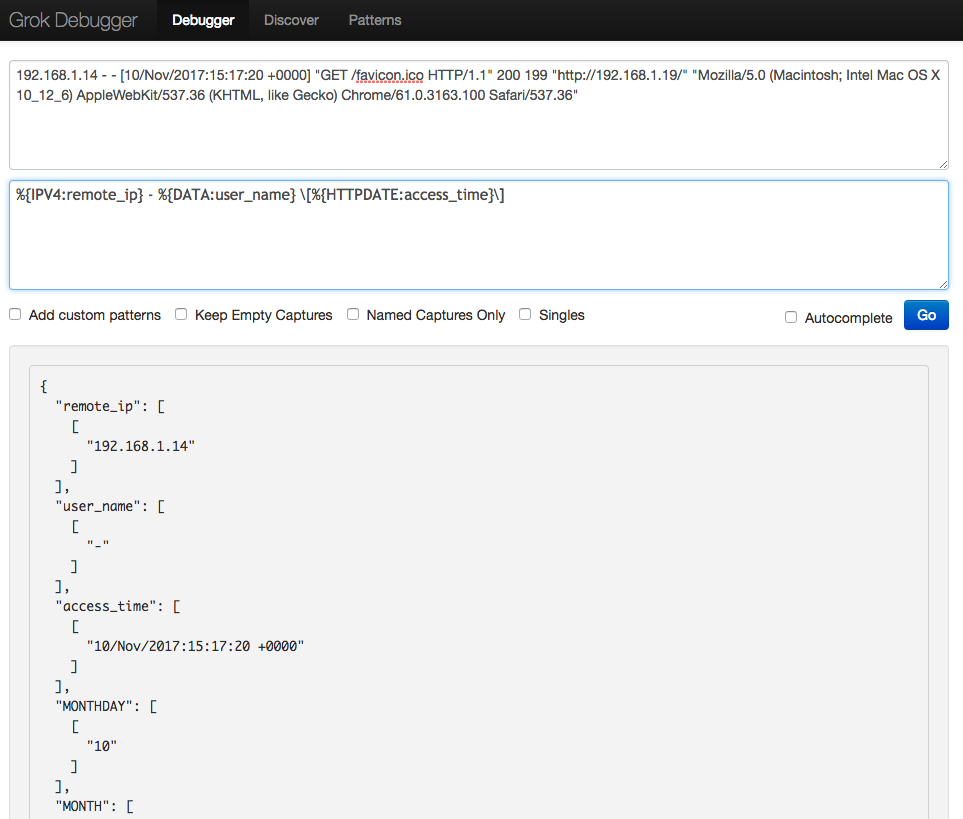

Head back to our original Nginx log.

Let’s suppose we wish to capture all of the available fields from our log line. Using the information we know about nginx combined log format, grok patterns and online grok debugger, we can start typing our grok pattern.

Eventually, we arrive to our complete grok pattern:

Now that we have written the grok pattern, we can start configuring the building blocks of this exercise: Filebeat and Logstash.

The Setup

Configure Filebeat

This is a fairly easy bit. Here’s what the configuration would look like for one Nginx access log. We will only change the prospectors and output section, while leaving the rest at default settings. For input_type we chose log and specified a path to the Nginx access log. To keep things as simple as possible, this concludes the prospectors section.

Next, the output configuration. Filebeat ships logs directly to Elasticsearch by default, so we need to comment out everything under the Elasticsearch output section:

We enable Logstash output configuration, which resides directly under the Elasticsearch output section. You’ll need the IP address of the server Logstash is running on (leave localhost if it’s running on the same server as Filebeat). For sake of simplicity, in this demonstration we’ll run Logstash on the same server as Filebeat (and Nginx), but in production it’s advisable to run Logstash on separate machine (which comes handy when you start considering scaling up).

Back to our one little machine. Uncomment the output.logstash line and hosts line:

That’s it for Filebeat. Restart the Filebeat service and check the output.

See? Told you it’s an easy bit. If you get the output like this, you’re good for the next step, which is…

Configure Logstash

As it has been said in the beginning, we’ll continue with this (rather lengthy) step in the next post. There we’ll configure and test Logstash, point out some tricky aspects while doing so, show how to enrich our data, and finally see what have we gotten out of this pipeline.

Источник

Next we’ll setup Logstash by first creating the ./logstash directory and

then start to work on the Logstash configuration file.

We’ll setup Logstash to use:

- 1 input for

syslog - 2 filters to process access and error logs

- 1 output to store the processed logs in

ElasticSearch

We will use the Logstash Grok filter plugin to process the incoming nginx

logs. Grok is a plugin where you write patterns that extract values from

raw data. These patterns are written in a matching language where you define

a simplified regular expression and give it a name.

For example, let’s say we want to validate and extract the HTTP method from a

string, then we’d write the following grok pattern:

METHOD (OPTIONS|GET|HEAD|POST|PUT|DELETE|TRACE|CONNECT)

You can then combine these named regular expressions to parse more complex

strings. Suppose we want to parse the first line of a HTTP request, that

could look like this:

GET /db HTTP/1.1POST /user/login HTTP/1.1

Then we’d define a grok pattern that we write as the text file

/etc/logstash/patterns/request_start with the following content:

METHOD (OPTIONS|GET|HEAD|POST|PUT|DELETE|TRACE|CONNECT)

REQUEST_START %{METHOD:method} %{DATA:path} HTTP/%{DATA:http_version}

To use this pattern we simply add a grok configuration to the filter

part of the Logstash config file:

filter { grok { patterns_dir => "/etc/logstash/patterns" match => { "message" => "%{REQUEST_START}" } } }

We have now told Logstash to match the raw message against our pattern and

extract 3 parts of the message. Processing our examples above we’d get the

following results:

GET /db HTTP/1.1

{

method: "GET",

path: "/db",

http_version: "1.1"

}

POST /user/login HTTP/1.1

{

method: "POST",

path: "/user/login",

http_version: "1.1"

}

Here’s how our grok patterns look for nginx access and error logs:

logstash/conf/patterns/nginx_access

METHOD (OPTIONS|GET|HEAD|POST|PUT|DELETE|TRACE|CONNECT)

NGINX_ACCESS %{IPORHOST:visitor_ip} - %{USERNAME:remote_user} [%{HTTPDATE:time_local}] "%{DATA:server_name}" "%{METHOD:method} %{URIPATHPARAM:path} HTTP/%{NUMBER:http_version}" %{INT:status} %{INT:body_bytes_sent} "%{URI:referer}" %{QS:user_agent}

logstash/conf/patterns/nginx_error

ERRORDATE %{YEAR}/%{MONTHNUM}/%{MONTHDAY} %{TIME}

NGINX_ERROR %{ERRORDATE:time_local} [%{LOGLEVEL:level}] %{INT:process_id}#%{INT:thread_id}: *(%{INT:connection_id})? %{GREEDYDATA:description}

And here’s how we configure Logstash to setup syslog input, our grok

patterns and ElasticSearch output:

logstash/conf/logstash.conf

input { syslog { host => "logstash" port => 5140 } } filter { if [program] == "nginx_access" { grok { patterns_dir => "/etc/logstash/patterns" match => { "message" => "%{NGINX_ACCESS}" } remove_tag => ["nginx_access", "_grokparsefailure"] add_field => { "type" => "nginx_access" } remove_field => ["program"] } date { match => ["time_local", "dd/MMM/YYYY:HH:mm:ss Z"] target => "@timestamp" remove_field => "time_local" } useragent { source => "user_agent" target => "useragent" remove_field => "user_agent" } } if [program] == "nginx_error" { grok { patterns_dir => "/etc/logstash/patterns" match => { "message" => "%{NGINX_ERROR}" } remove_tag => ["nginx_error", "_grokparsefailure"] add_field => { "type" => "nginx_error" } remove_field => ["program"] } date { match => ["time_local", "YYYY/MM/dd HH:mm:ss"] target => "@timestamp" remove_field => "time_local" } } } output { elasticsearch { hosts => ["http://elasticsearch:9200"] manage_template => true template_overwrite => true template => "/etc/logstash/es_template.json" index => "logstash-%{+YYYY.MM.dd}" } }

The parameter program that we base our if-cases on is the tag value that we

configured nginx to add to the different types of logs:

# Send logs to Logstash access_log syslog:server=logstash:5140,tag=nginx_access logstash; error_log syslog:server=logstash:5140,tag=nginx_error notice;

The only thing left before we create the Dockerfile is to create the

ElasticSearch template to use. This template tells ElasticSearch what fields

our different types of log items will have. If you look closely at this

template, you’ll notice that all the defined fields exists in the grok filter

definition.

logstash/conf/es_template.json

{

"version" : 50001,

"template" : "logstash-*",

"settings" : {

"index" : {

"refresh_interval" : "5s"

}

},

"mappings" : {

"nginx_access" : {

"_all" : {

"enabled" : false,

"norms" : false

},

"properties" : {

"@timestamp" : {

"type" : "date"

},

"body_bytes_sent": {

"type" : "integer"

},

"message" : {

"type" : "text"

},

"host" : {

"type" : "keyword"

},

"server_name" : {

"type" : "keyword"

},

"referer" : {

"type" : "keyword"

},

"remote_user" : {

"type" : "keyword"

},

"method" : {

"type" : "keyword"

},

"path" : {

"type" : "keyword"

},

"http_version" : {

"type" : "keyword"

},

"status" : {

"type" : "short"

},

"tags" : {

"type" : "keyword"

},

"useragent" : {

"dynamic" : true,

"properties" : {

"device" : {

"type" : "keyword"

},

"major" : {

"type" : "short"

},

"minor" : {

"type" : "short"

},

"os" : {

"type" : "keyword"

},

"os_name" : {

"type" : "keyword"

},

"patch" : {

"type" : "short"

}

}

},

"visitor_ip" : {

"type": "ip"

}

}

},

"nginx_error" : {

"_all" : {

"enabled" : false,

"norms" : false

},

"properties" : {

"@timestamp" : {

"type" : "date"

},

"level" : {

"type" : "keyword"

},

"process_id" : {

"type" : "integer"

},

"thread_id" : {

"type" : "integer"

},

"connection_id" : {

"type" : "integer"

},

"message" : {

"type" : "text"

},

"content" : {

"type" : "text"

}

}

}

},

"aliases" : {}

}

Now that we have all of our configurations for Logstash setup, we can create

the Dockerfile:

logstash/Dockerfile

FROM logstash:5.5-alpine ENV PLUGIN_BIN "/usr/share/logstash/bin/logstash-plugin" RUN "$PLUGIN_BIN" install logstash-input-syslog RUN "$PLUGIN_BIN" install logstash-filter-date RUN "$PLUGIN_BIN" install logstash-filter-grok RUN "$PLUGIN_BIN" install logstash-filter-useragent RUN "$PLUGIN_BIN" install logstash-output-elasticsearch COPY ./conf /etc/logstash CMD ["-f", "/etc/logstash/logstash.conf"]

After this, our project should have the following files:

code/nginx-elk-logging

├── docker-compose.yaml

├── logstash

│ ├── conf

│ │ ├── es_template.json

│ │ ├── logstash.conf

│ │ └── patterns

│ │ ├── nginx_access

│ │ └── nginx_error

│ └── Dockerfile

└── nginx

├── conf

│ └── nginx.conf

├── data

│ └── index.html

└── Dockerfile

6 directories, 9 files

In a previous post, we explored the basic concepts behind using Grok patterns with Logstash to parse files. We saw how versatile this combo is and how it can be adapted to process almost anything we want to throw at it. But the first few times you use something, it can be hard to figure out how to configure for your specific use case. Looking at real-world examples can help here, so let’s learn how to use Grok patterns in Logstash to parse common logs we’d often encounter, such as those generated by Nginx, MySQL, Elasticsearch, and others.

First, Some Preparation

We’ll take a look at a lot of example logs and Logstash config files in this post so, if you want to follow along, instead of downloading each one at each step, let’s just copy all of them at once and place them in the “/etc/logstash/conf.d/logstash” directory.

First, install Git if it’s not already installed:

sudo apt update && sudo apt install git

Now let’s download the files and place them in the directory:

sudo git clone https://github.com/coralogix-resources/logstash.git /etc/logstash/conf.d/logstash

NGINX Access Logs

NGINX and Apache are the most popular web servers in the world. So, chances are, we will often have contact with the logs they generate. These logs reveal information about visits to your site like file access requests, NGINX responses to those requests, and information about the actual visitors, including their IP, browser, operating system, etc. This data is helpful for general business intelligence, but also for monitoring for security threats by malicious actors.

Let’s see how a typical Nginx log is structured.

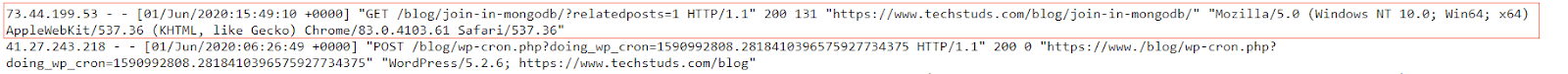

We’ll open the following link in a web browser https://raw.githubusercontent.com/coralogix-resources/logstash/master/nginx/access.log and then copy the first line. Depending on your monitor’s resolution, the first line might actually be broken into two lines, to fit on the screen (otherwise called “line wrapping”). To avoid any mistakes, here is the exact content of the line we will copy:

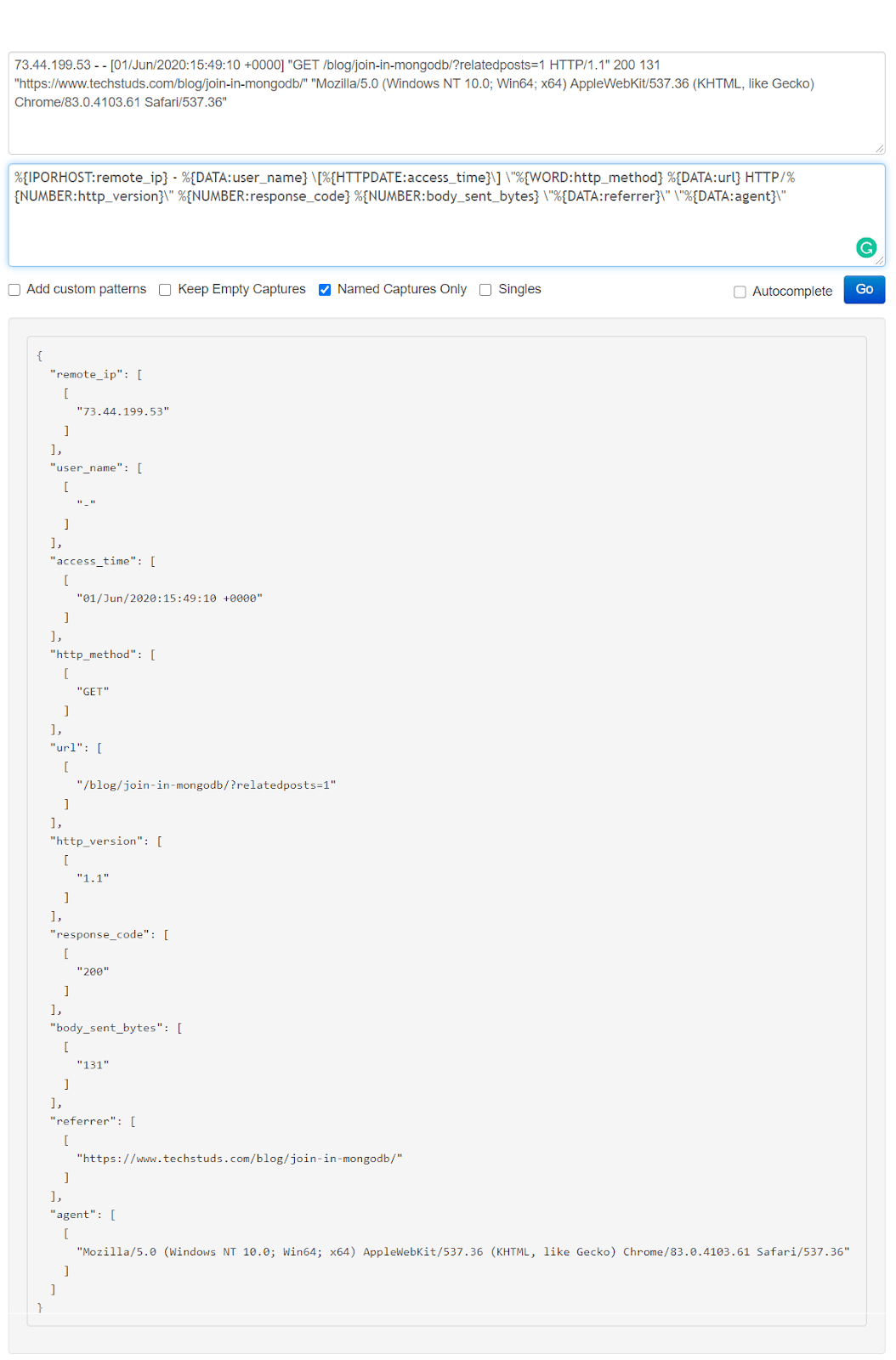

73.44.199.53 - - [01/Jun/2020:15:49:10 +0000] "GET /blog/join-in-mongodb/?relatedposts=1 HTTP/1.1" 200 131 "https://www.techstuds.com/blog/join-in-mongodb/" "Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/83.0.4103.61 Safari/537.36"

Original image link here

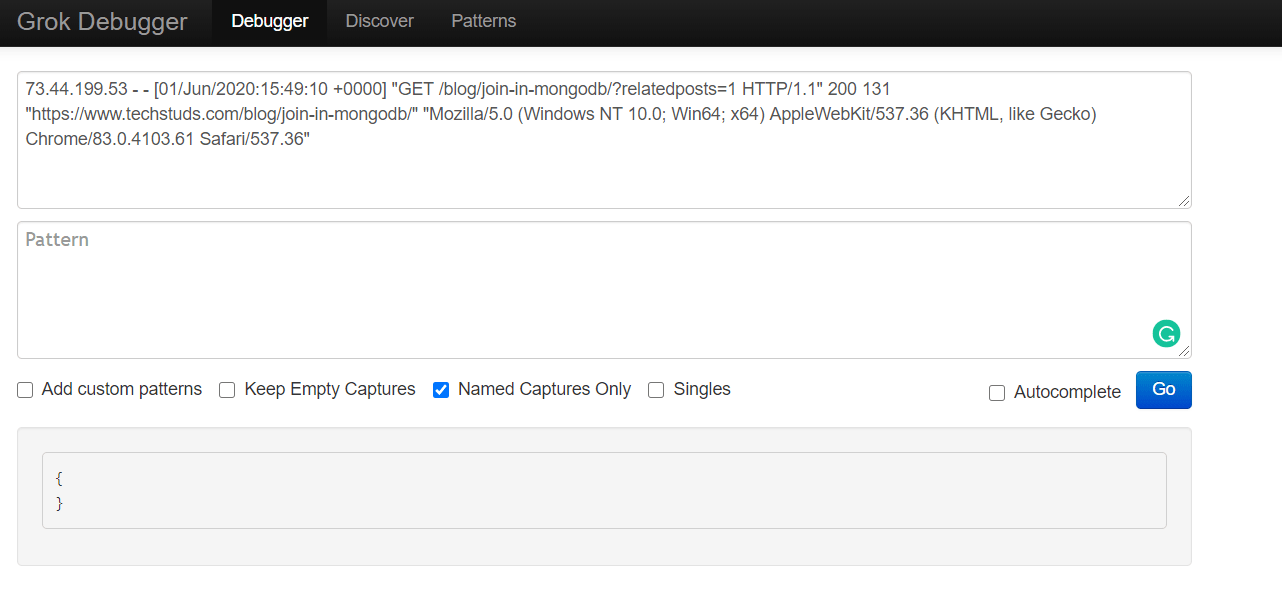

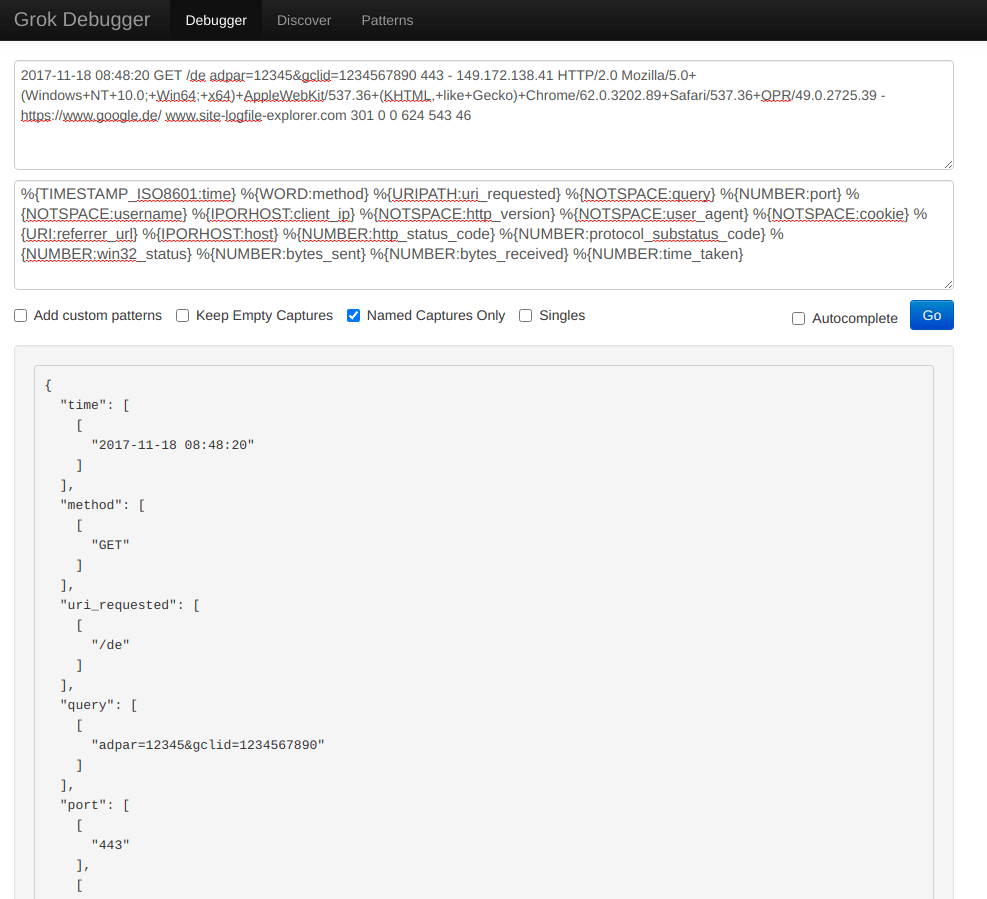

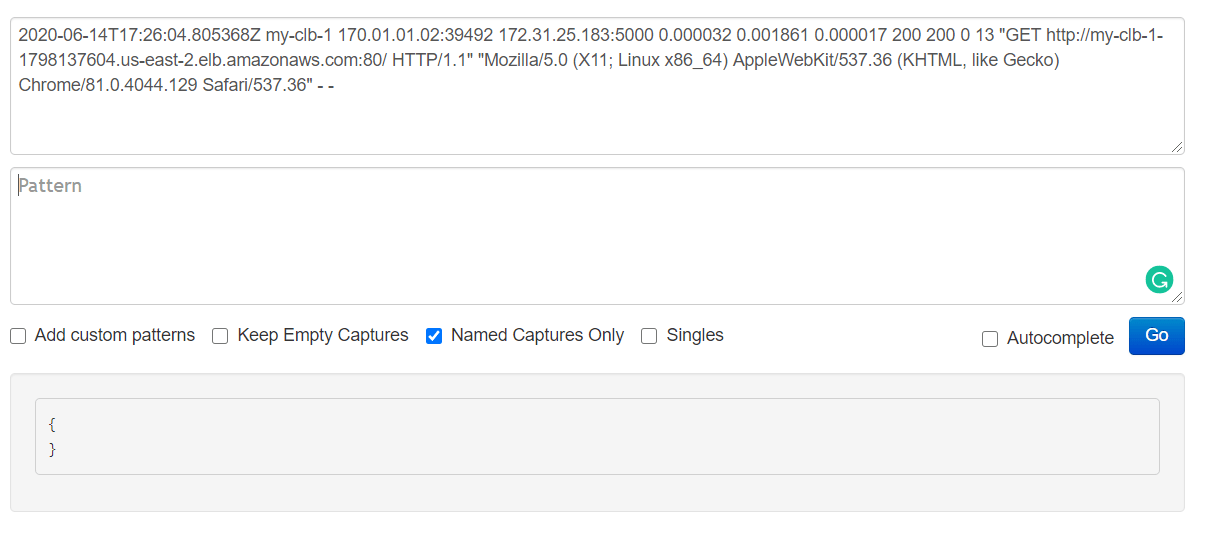

Next, let’s open the Grok Debugger Tool at https://grokdebug.herokuapp.com/ to help us out. In the first field, the input section, we’ll paste the previously copied line.

Original image link here

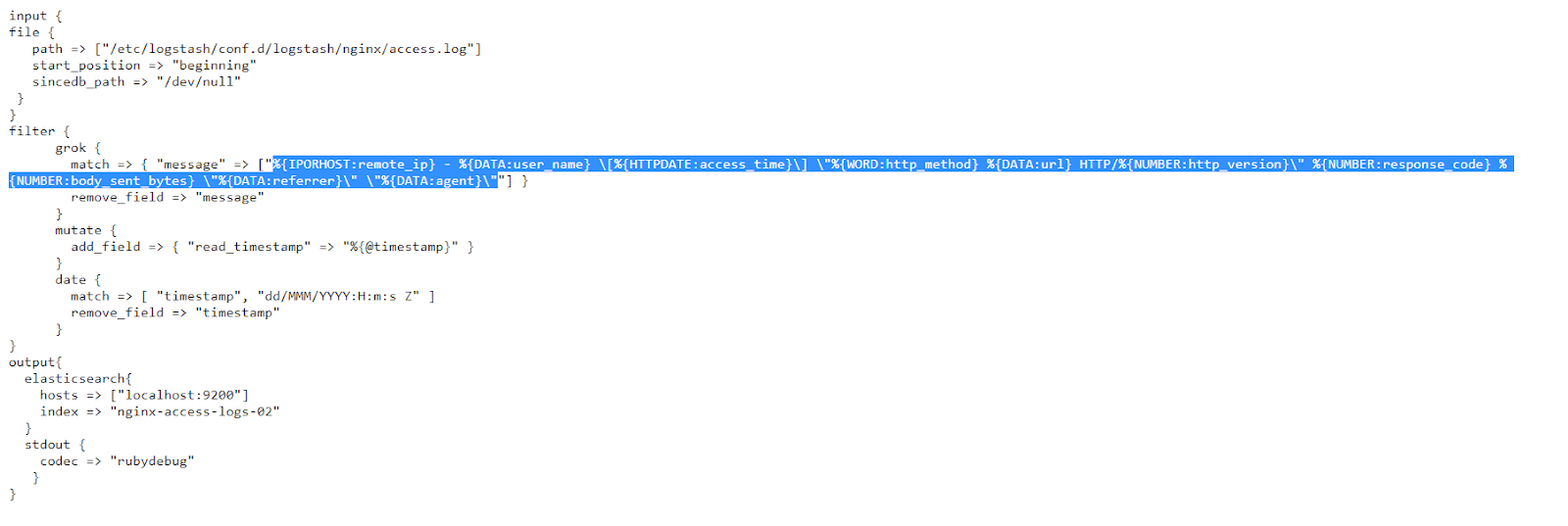

Now let’s have a look at the Logstash config we’ll use to parse our Nginx log: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/coralogix-resources/logstash/master/nginx/nginx-access-final.conf.

From here, we’ll copy the Grok pattern from the “match” section. This is the exact string we should copy:

%{IPORHOST:remote_ip} - %{DATA:user_name} [%{HTTPDATE:access_time}] "%{WORD:http_method} %{DATA:url} HTTP/%{NUMBER:http_version}" %{NUMBER:response_code} %{NUMBER:body_sent_bytes} "%{DATA:referrer}" "%{DATA:agent}"

Original image link

We go back to the https://grokdebug.herokuapp.com/ website and paste the Grok pattern in the second field, the pattern section. We’ll also tick the “Named captures only” checkbox and then click the “Go” button.

Note: For every line you copy and paste, make sure there are no empty lines before (or after) the actual text in the pattern field. Depending on how you copy and paste text, sometimes an empty line might get inserted before or after the copied string, which will make the Grok Debugger fail to parse your text. If this happens, just delete the empty line(s).

Original image link here

This tool is useful to test if our Grok patterns work as intended. It makes it convenient to try out new patterns, or modify existing ones and see in advance if they produce the desired results.

Now that we’ve seen that this correctly separates and extracts the data we need, let’s run Logstash with the configuration created specifically to work with the Nginx log file:

sudo /usr/share/logstash/bin/logstash -f /etc/logstash/conf.d/logstash/nginx/nginx-access-final.conf

The job should finish in a few seconds. When we notice no more output is generated, we can close Logstash by pressing CTRL+C.

Now let’s see how the log file has been parsed and indexed:

curl -XGET "http://localhost:9200/nginx-access-logs-02/_search?pretty" -H 'Content-Type: application/json' -d'{

"size": 1,

"track_total_hits": true,

"query": {

"bool": {

"must_not": [

{

"term": {

"tags.keyword": "_grokparsefailure"

}

}

]

}

}

}'

We’ll see a response similar to the following:

{

"_index" : "nginx-access-logs-02",

"_type" : "_doc",

"_id" : "vvhO2XIBB7MjzkVPHJhV",

"_score" : 0.0,

"_source" : {

"access_time" : "01/Jun/2020:15:49:10 +0000",

"user_name" : "-",

"url" : "/blog/join-in-mongodb/?relatedposts=1",

"path" : "/etc/logstash/conf.d/logstash/nginx/access.log",

"body_sent_bytes" : "131",

"response_code" : "200",

"@version" : "1",

"referrer" : "https://www.techstuds.com/blog/join-in-mongodb/",

"http_version" : "1.1",

"read_timestamp" : "2020-06-21T23:54:33.738Z",

"@timestamp" : "2020-06-21T23:54:33.738Z",

"agent" : "Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/83.0.4103.61 Safari/537.36",

"http_method" : "GET",

"host" : "coralogix",

"remote_ip" : "73.44.199.53"

}

We can see the fields and their associated values neatly extracted by the Grok patterns.

IIS Logs

While we’ll often see Apache and Nginx web servers on the Linux operating system, Microsoft Windows has its own web server included in IIS (Internet Information Services). These generate their own logs that can be helpful to monitor the state and activity of applications. Let’s learn how to parse logs generated by IIS.

Just as before, we will take a look at the sample log file and extract the first useful line: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/coralogix-resources/logstash/master/iis/u_ex171118-sample.log.

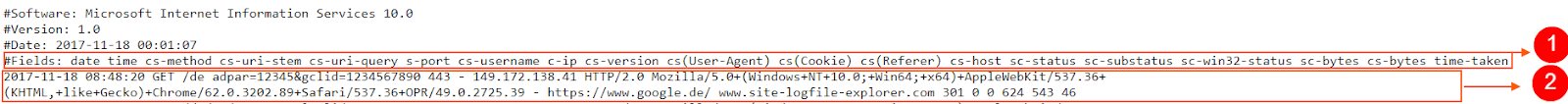

We’ll ignore the first few lines starting with “#” as that is a header, and not actual logged data. The line we’ll extract is the following:

2017-11-18 08:48:20 GET /de adpar=12345&gclid=1234567890 443 - 149.172.138.41 HTTP/2.0 Mozilla/5.0+(Windows+NT+10.0;+Win64;+x64)+AppleWebKit/537.36+(KHTML,+like+Gecko)+Chrome/62.0.3202.89+Safari/537.36+OPR/49.0.2725.39 - https://www.google.de/ www.site-logfile-explorer.com 301 0 0 624 543 46

Original image link here

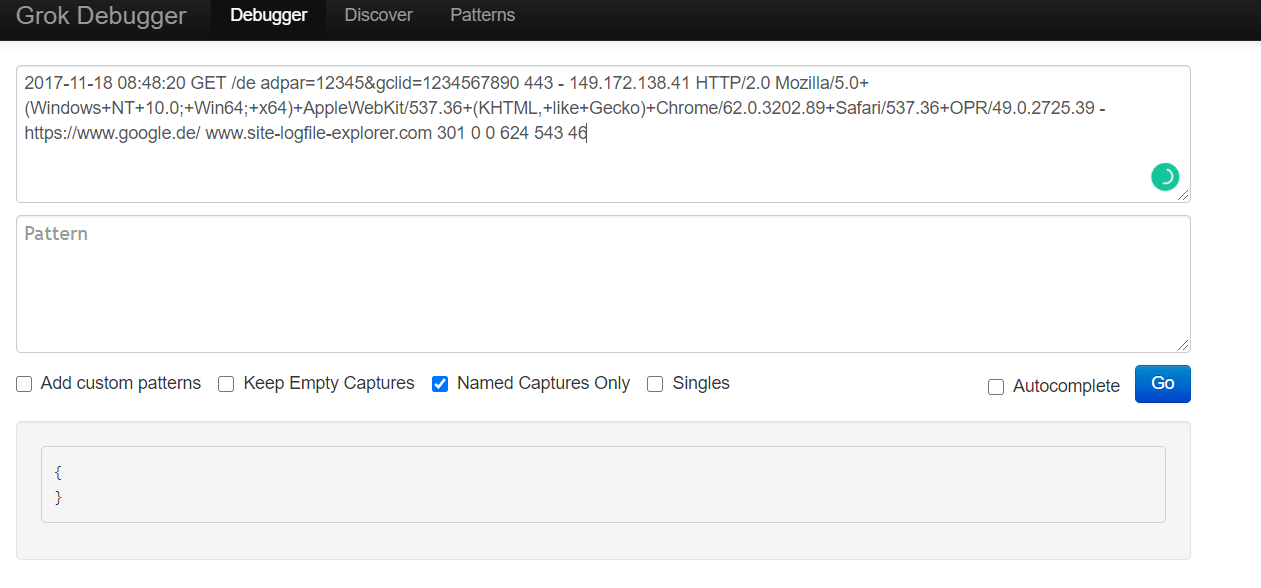

Once again, to take a closer look at how our specific Grok patterns will work, we’ll paste our log line into the Grok Debugger Tool tool, in the first field, the input section.

Original image link here

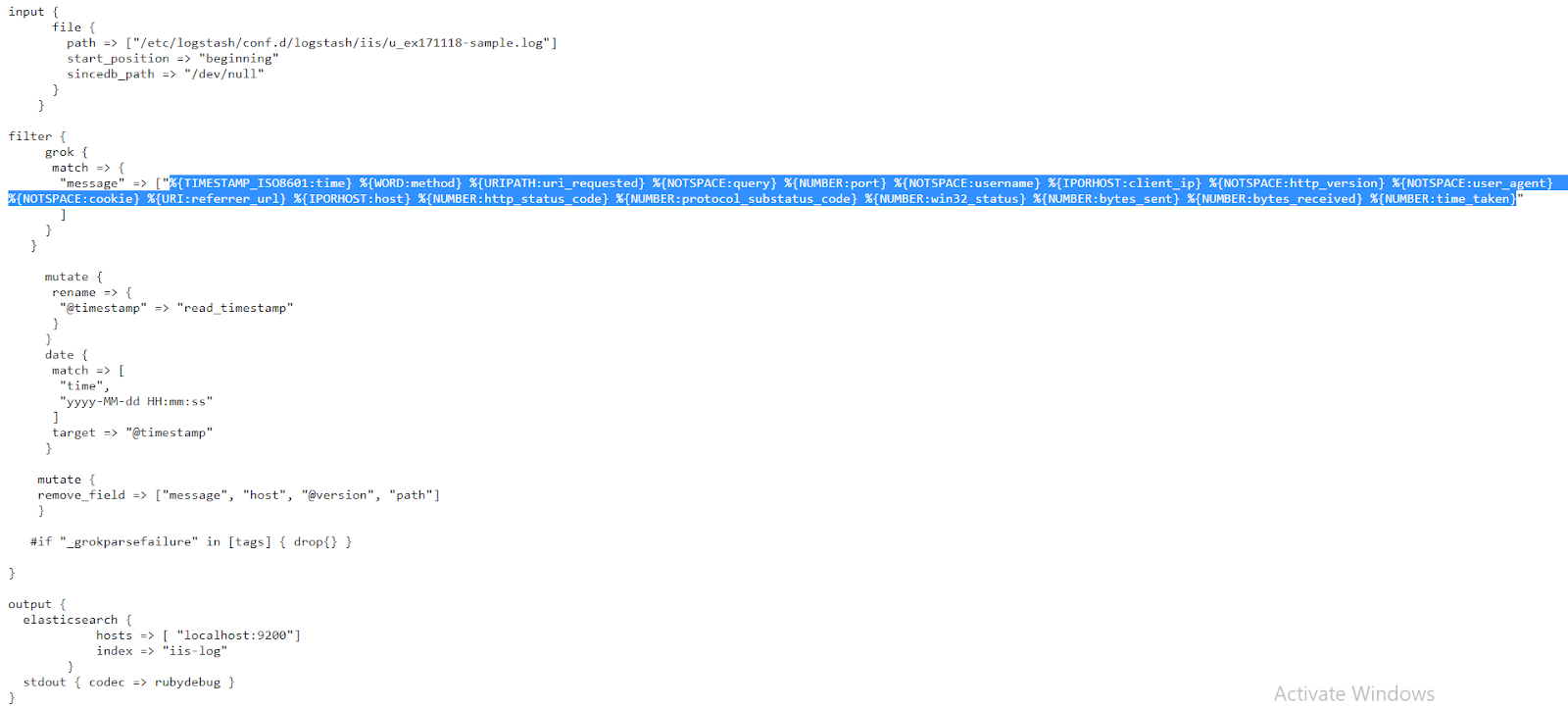

The config file we’ll use to parse the log can be found at https://raw.githubusercontent.com/coralogix-resources/logstash/master/iis/iis-final-working.conf.

Original image link here

Once again, let’s copy the Grok pattern within:

%{TIMESTAMP_ISO8601:time} %{WORD:method} %{URIPATH:uri_requested} %{NOTSPACE:query} %{NUMBER:port} %{NOTSPACE:username} %{IPORHOST:client_ip} %{NOTSPACE:http_version} %{NOTSPACE:user_agent} %{NOTSPACE:cookie} %{URI:referrer_url} %{IPORHOST:host} %{NUMBER:http_status_code} %{NUMBER:protocol_substatus_code} %{NUMBER:win32_status} %{NUMBER:bytes_sent} %{NUMBER:bytes_received} %{NUMBER:time_taken}

…and paste it to the second field in the https://grokdebug.herokuapp.com/ website, the pattern section:

Original Image Link here

Let’s run Logstash and parse this IIS log:

sudo /usr/share/logstash/bin/logstash -f /etc/logstash/conf.d/logstash/iis/iis-final-working.conf

As usual, we’ll wait for a few seconds until the job is done and then press CTRL+C to exit the utility.

Let’s look at the parsed data:

curl -XGET "http://localhost:9200/iis-log/_search?pretty" -H 'Content-Type: application/json' -d'{

"size": 1,

"track_total_hits": true,

"query": {

"bool": {

"must_not": [

{

"term": {

"tags.keyword": "_grokparsefailure"

}

}

]

}

}

}'

A response similar to the following shows us that everything is neatly structured in the index.

{

"_index" : "iis-log",

"_type" : "_doc",

"_id" : "6_i62XIBB7MjzkVPS5xL",

"_score" : 0.0,

"_source" : {

"http_version" : "HTTP/2.0",

"query" : "adpar=12345&gclid=1234567890",

"bytes_received" : "543",

"read_timestamp" : "2020-06-22T01:52:43.628Z",

"user_agent" : "Mozilla/5.0+(Windows+NT+10.0;+Win64;+x64)+AppleWebKit/537.36+(KHTML,+like+Gecko)+Chrome/62.0.3202.89+Safari/537.36+OPR/49.0.2725.39",

"uri_requested" : "/de",

"username" : "-",

"time_taken" : "46",

"referrer_url" : "https://www.google.de/",

"client_ip" : "149.172.138.41",

"http_status_code" : "301",

"bytes_sent" : "624",

"time" : "2017-11-18 08:48:20",

"cookie" : "-",

"method" : "GET",

"@timestamp" : "2017-11-18T06:48:20.000Z",

"protocol_substatus_code" : "0",

"win32_status" : "0",

"port" : "443"

}

MongoDB Logs

While not as popular as MySQL, the MongoDB database engine still has a fairly significant market share and is used by many leading companies. The MongoDB logs can help us track the database performance and resource utilization to help with troubleshooting and performance tuning.

Let’s see how a MongoDB log looks like: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/coralogix-resources/logstash/master/mongodb/mongodb.log.

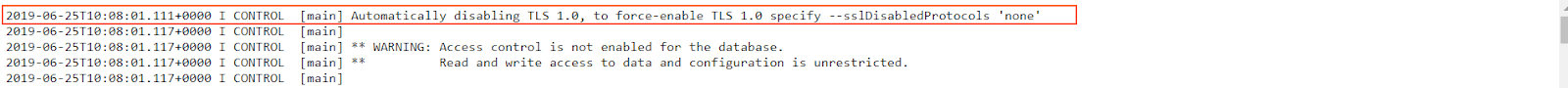

Original image link

We can see fields are structured in a less repetitive and predictable way than in a typical Nginx log.

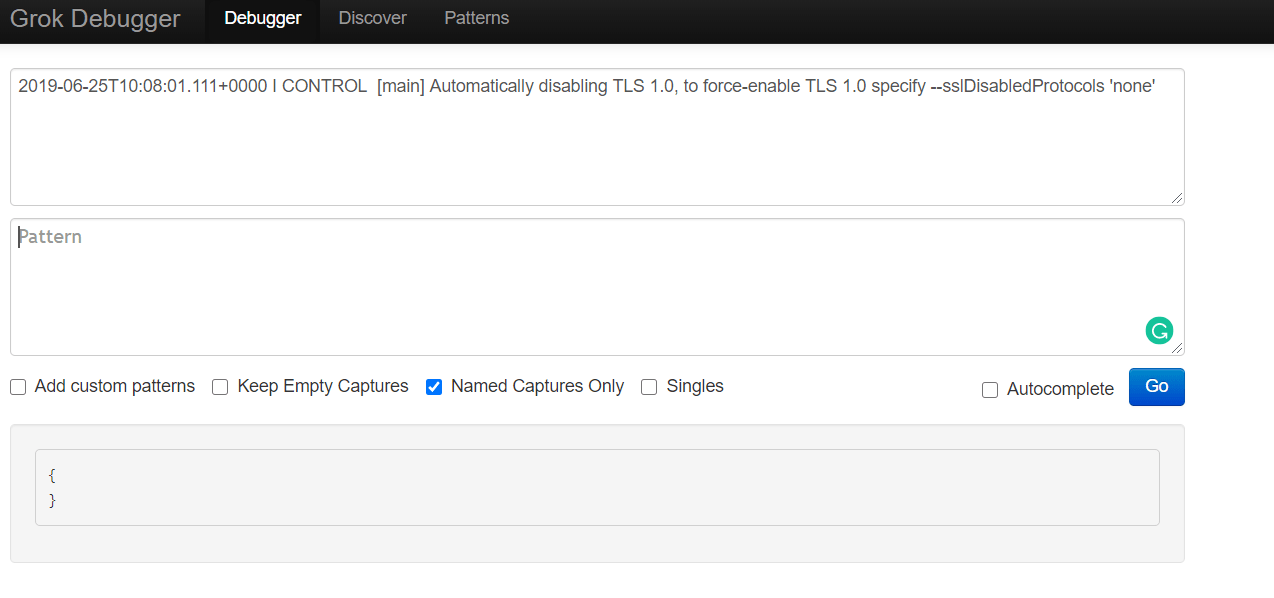

Let’s copy the first line from the log and paste it into the first field of the Grok Debugger Tool website.

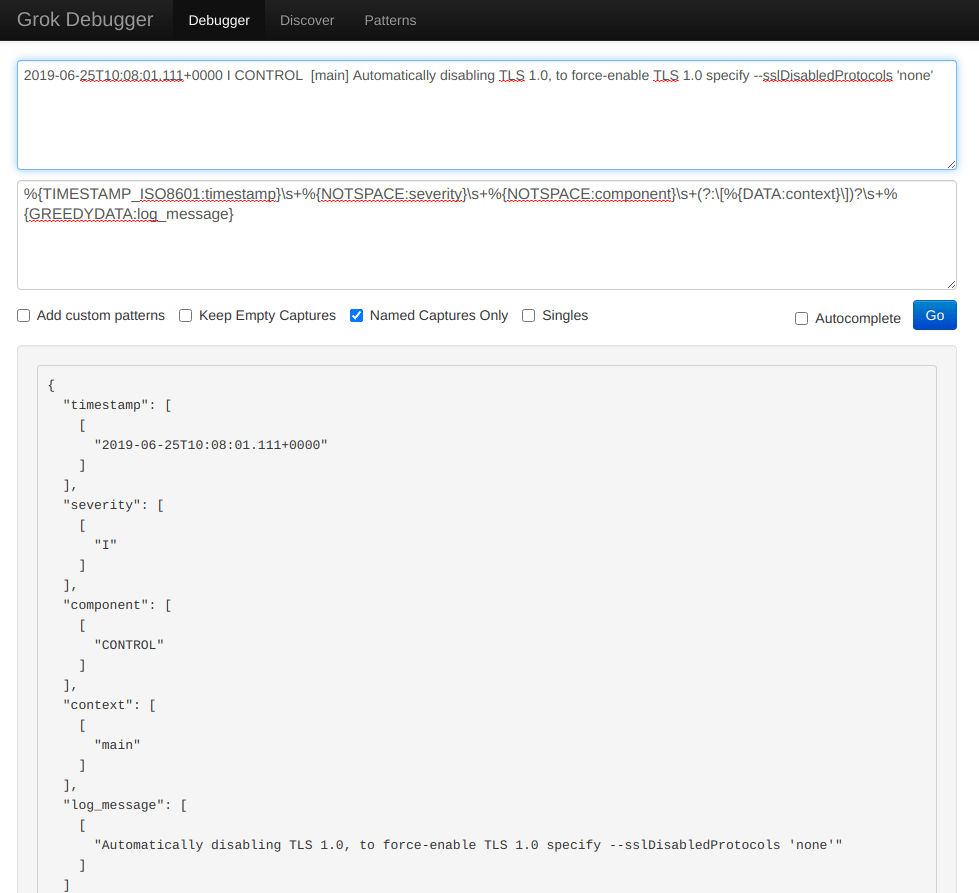

2019-06-25T10:08:01.111+0000 I CONTROL [main] Automatically disabling TLS 1.0, to force-enable TLS 1.0 specify --sslDisabledProtocols 'none'

Original image link

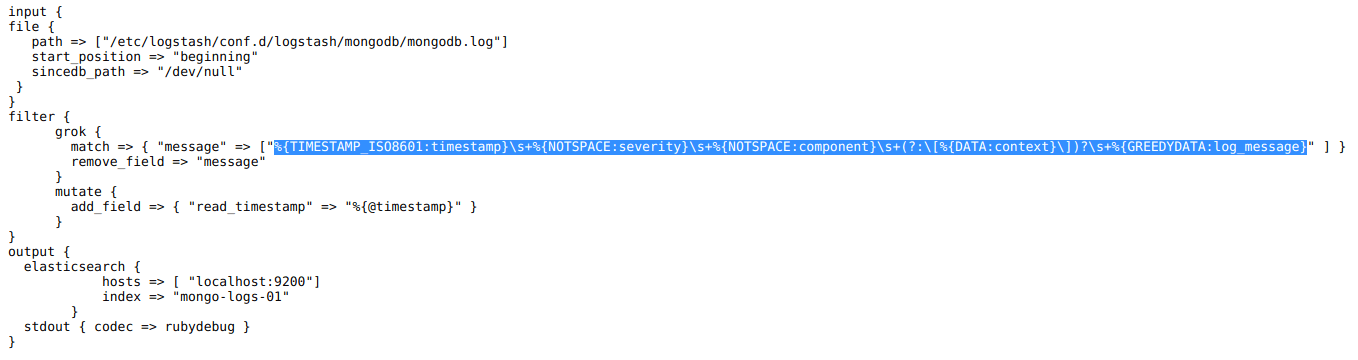

The config file we will use for Logstash, to parse our log, can be found at https://raw.githubusercontent.com/coralogix-resources/logstash/master/mongodb/mongodb-final.conf.

Original image link

And here is the Grok pattern we need to copy:

%{TIMESTAMP_ISO8601:timestamp}s+%{NOTSPACE:severity}s+%{NOTSPACE:component}s+(?:[%{DATA:context}])?s+%{GREEDYDATA:log_message}

As usual, let’s paste it to the second field in the https://grokdebug.herokuapp.com/ website.

Original image link

Let’s run Logstash:

sudo /usr/share/logstash/bin/logstash -f /etc/logstash/conf.d/logstash/mongodb/mongodb-final.conf

When the job is done, we press CTRL+C to exit the program and then we can take a look at how the data was parsed:

curl -XGET "http://localhost:9200/mongo-logs-01/_search?pretty" -H 'Content-Type: application/json' -d'{

"size": 1,

"track_total_hits": true,

"query": {

"bool": {

"must_not": [

{

"term": {

"tags.keyword": "_grokparsefailure"

}

}

]

}

}

}'

The output should be similar to the following:

{

"_index" : "mongo-logs-01",

"_type" : "_doc",

"_id" : "0vjo2XIBB7MjzkVPS6y9",

"_score" : 0.0,

"_source" : {

"log_message" : "Automatically disabling TLS 1.0, to force-enable TLS 1.0 specify --sslDisabledProtocols 'none'",

"@timestamp" : "2020-06-22T02:42:58.604Z",

"timestamp" : "2019-06-25T10:08:01.111+0000",

"context" : "main",

"component" : "CONTROL",

"read_timestamp" : "2020-06-22T02:42:58.604Z",

"@version" : "1",

"path" : "/etc/logstash/conf.d/logstash/mongodb/mongodb.log",

"host" : "coralogix",

"severity" : "I"

}

User Agent Mapping and IP to Geo Location Mapping in Logs

Very often, when a web browser requests a web page from a web server, it also sends a so-called “user agent”. This can contain information such as the operating system used by a user, the device, the web browser name and version and so on. Obviously, this can be very useful data in certain scenarios. For example, it can help you find out if users of a particular operating system are experiencing issues.

Web servers also log the IP addresses of the visitors. While that’s useful to have in raw logs, those numbers themselves are not always useful to humans. They might be nice to have when trying to debug connectivity issues, or block a class of IPs, but for statistics and charts, it might be more relevant to have the geographic location of each IP, like country/city and so on.

Logstash can “transform” user agents like

Mozilla/5.0+(Windows+NT+10.0;+Win64;+x64)+AppleWebKit/537.36+(KHTML,+like+Gecko)+Chrome/62.0.3202.89+Safari/537.36+OPR/49.0.2725.39

to the actual names of the specific operating system, device and/or browser that was used, and other info which is much more easy to read and understand by humans. Likewise, IP addresses can be transformed to estimated geographical locations. The technical term for these transformations is mapping.

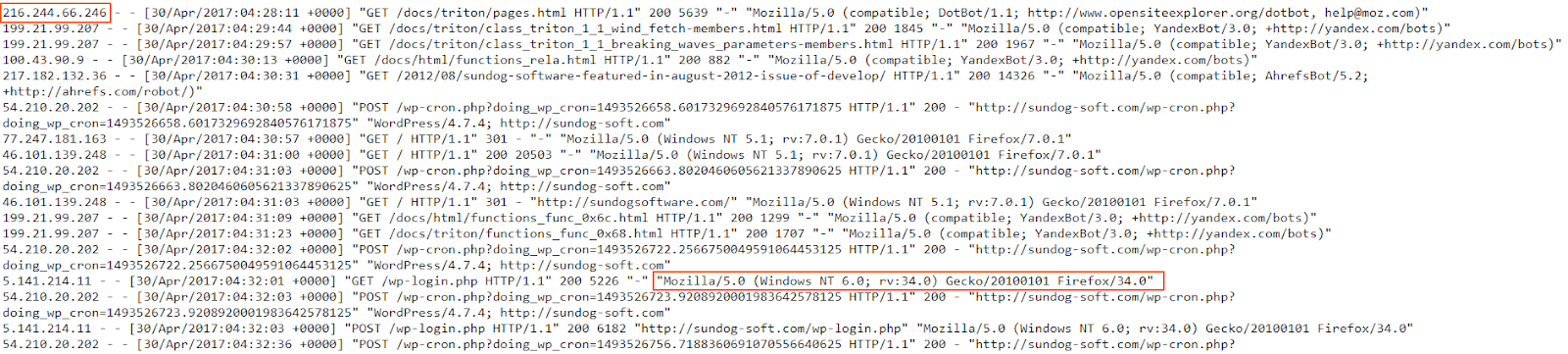

Let’s take a look at an Apache access log: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/coralogix-resources/logstash/master/apache/access_log.

Original image link

We notice IP addresses and user agents all throughout the log. Now let’s see the Logstash config we’ll use to do our mapping magic with this information: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/coralogix-resources/logstash/master/apache/apache-access-enriched.conf.

The interesting entries here can be seen under “useragent” and “geoip“.

Original image link

In the useragent filter section, we simply instruct Logstash to take the contents of the agent field, process them accordingly, and map them back to the agent field.

In the geoip filter, we instruct Logstash to take the information from the clientip field, process it, and then insert the output in a new field, called geoip.

Let’s run Logstash with this config and see what happens:

sudo /usr/share/logstash/bin/logstash -f /etc/logstash/conf.d/logstash/apache/apache-access-enriched.conf

We’ll need to wait for a longer period of time for this to be done as there are many more lines the utility has to process (tens of thousands). As usual, when it’s done, we’ll press CTRL+C to exit.

Now let’s explore how this log was parsed and what was inserted to the index:

curl -XGET "http://localhost:9200/apache-logs/_search?pretty" -H 'Content-Type: application/json' -d'{

"size": 1,

"track_total_hits": true,

"query": {

"bool": {

"must_not": [

{

"term": {

"tags.keyword": "_grokparsefailure"

}

}

]

}

}

}'

The output will be similar to the following:

{

"_index" : "apache-logs",

"_type" : "_doc",

"_id" : "4vgC2nIBB7MjzkVPhtPl",

"_score" : 0.0,

"_source" : {

"verb" : "GET",

"host" : "coralogix",

"response" : "200",

"agent" : {

"name" : "Firefox",

"build" : "",

"device" : "Other",

"os" : "Windows",

"major" : "34",

"minor" : "0",

"os_name" : "Windows"

},

"clientip" : "178.150.5.107",

"ident" : "-",

"bytes" : "5226",

"geoip" : {

"continent_code" : "EU",

"timezone" : "Europe/Kiev",

"country_code3" : "UA",

"country_name" : "Ukraine",

"location" : {

"lat" : 50.4547,

"lon" : 30.5238

},

"region_name" : "Kyiv City",

"city_name" : "Kyiv",

"country_code2" : "UA",

"ip" : "178.150.5.107",

"postal_code" : "04128",

"longitude" : 30.5238,

"region_code" : "30",

"latitude" : 50.4547

},

"referrer" : ""-"",

"auth" : "-",

"httpversion" : "1.1",

"read_timestamp" : "2020-06-22T03:11:37.715Z",

"path" : "/etc/logstash/conf.d/logstash/apache/access_log",

"@timestamp" : "2017-04-30T19:16:43.000Z",

"request" : "/wp-login.php",

"@version" : "1"

}

}

Looking good. We can see the newly added geoip and agent fields are very detailed and very easy to read.

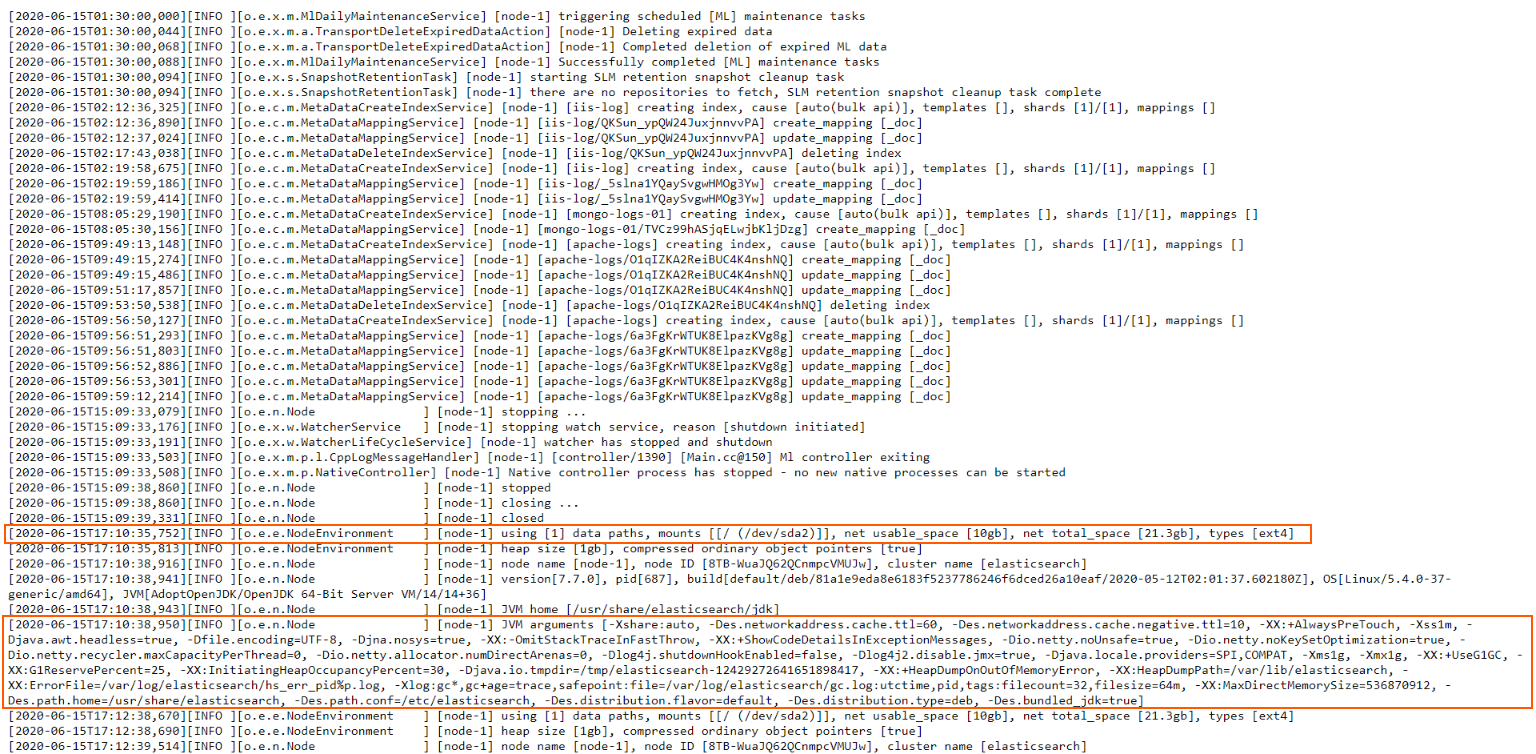

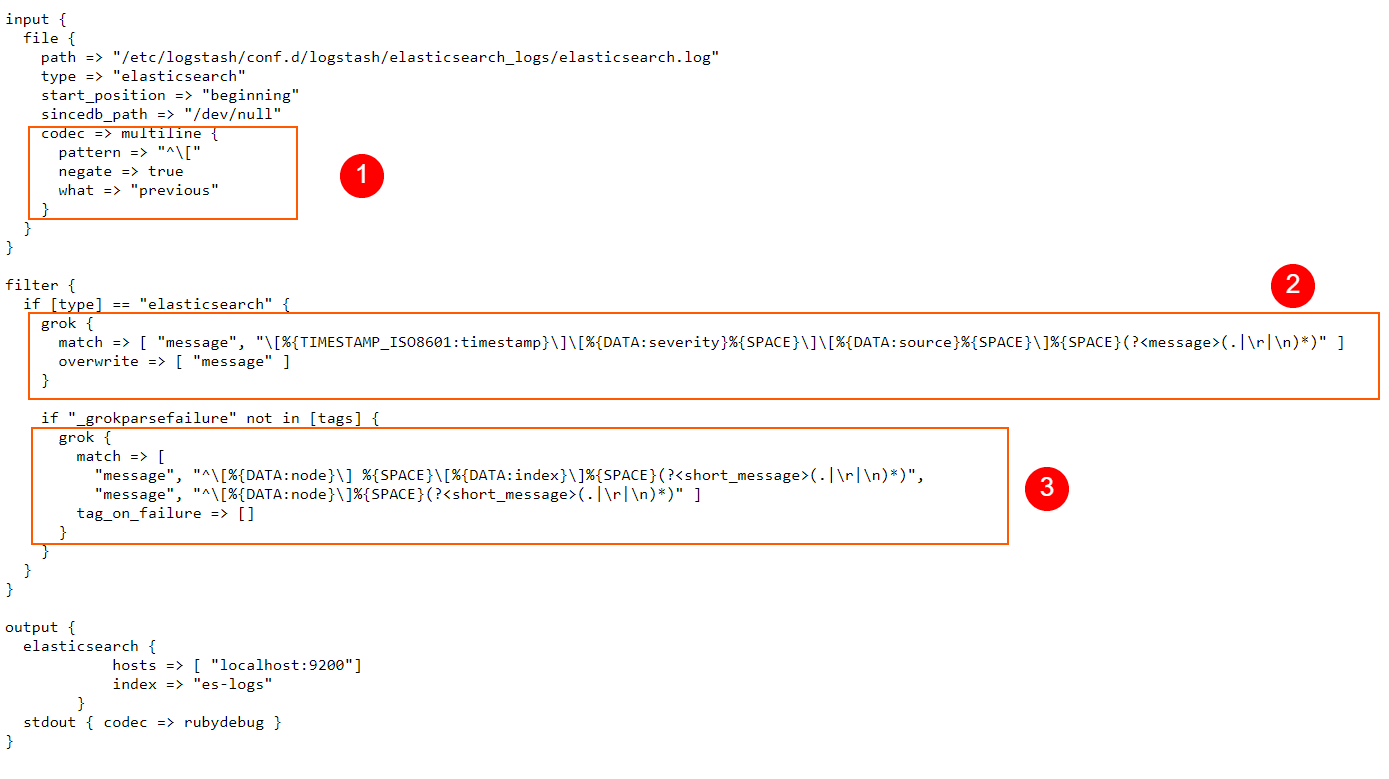

Elasticsearch Logs

We explored many log types, but let’s not forget, Elasticsearch generates logs too which helps us troubleshooting issues, like for example, figuring out why a node hasn’t started. Let’s look at a sample: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/coralogix-resources/logstash/master/elasticsearch_logs/elasticsearch.log.

Original link here

Now, this is slightly different from what we’ve worked with up until now. In all the other logs, each line represented one specific log entry (or message). That meant we could process them line by line and reasonably expect that each logged event is contained within a single line, in its entirety.

Here, however, we sometimes encounter multi-line log entries. This means that a logged event can span across multiple lines, not just one. Fortunately, though, Elasticsearch clearly signals where a logged event begins and where it ends. It does so by using opening [ and closing ] square brackets. If you see that a line opens a square bracket [ but doesn’t close it on the same line, you know that’s a multi-line log entry and it ends on the line that finally uses the closing square bracket ].

Logstash can easily process these logs by using the multiline input codec.

Let’s take a look at the Logstash config we’ll use here: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/coralogix-resources/logstash/master/elasticsearch_logs/es-logs-final.conf.

Original link here

In the codec => multiline section of our config, we define the pattern that instructs Logstash on how to identify multiline log entries. Here, we use a RegEx pattern, but of course, we can also use Grok patterns when we need to.

With negate set to true, a message that matches the pattern is not considered a match for the multiline filter. By default, this is set to false and when it is false, a message that matches the pattern is considered a match for multiline.

“what” can be assigned a value of “previous” or “next“. For example, if we have a match, negate is set to false, and what has a value set to previous, this means that the current matched line belongs to the same event as the previous line.

In a nutshell, what we are doing for our scenario here is telling Logstash that if a line does not start with an opening square bracket [ then the line in the log file is a continuation of the previous line, so these will be grouped in a single event. Logstash will apply a “multiline” tag to such entries, which can be useful for debugging, or other similar purposes if we ever need to know which entry was contained in a single line, and which on multiple lines.

In the filter section we use a typical Grok pattern, just like we did many times before, and replace the message field with the parsed content.

Finally, a second Grok pattern will process the content in the message field even further, extracting things like the logged node name, index name, and so on.

Let’s run Logstash and see all of this in action:

sudo /usr/share/logstash/bin/logstash -f /etc/logstash/conf.d/logstash/elasticsearch_logs/es-logs-final.conf

After the program does its job, we press CTRL+C to exit.

Logstash has now parsed both single-line events and multiline events. We will now see how useful it can be that multiline events have been tagged appropriately. Because of this tag, we can now search entries that contain only single-line events. We do this by specifying in our cURL request that the matches must_not contain the tags called multiline.

curl -XGET "http://localhost:9200/es-test-logs/_search?pretty" -H 'Content-Type: application/json' -d'{

"size": 1,

"query": {

"bool": {

"must_not": [

{

"match": {

"tags": "multiline"

}

}

]

}

}

}'

The output will look something like this:

{

"_index" : "es-test-logs",

"_type" : "_doc",

"_id" : "9voa2nIBB7MjzkVP7ULy",

"_score" : 0.0,

"_source" : {

"node" : "node-1",

"source" : "o.e.x.m.MlDailyMaintenanceService",

"host" : "coralogix",

"@timestamp" : "2020-06-22T03:38:16.842Z",

"@version" : "1",

"message" : "[node-1] triggering scheduled [ML] maintenance tasks",

"timestamp" : "2020-06-15T01:30:00,000",

"short_message" : "triggering scheduled [ML] maintenance tasks",

"type" : "elasticsearch",

"severity" : "INFO",

"path" : "/etc/logstash/conf.d/logstash/elasticsearch_logs/elasticsearch.log"

}

Now let’s filter only the multiline entries:

curl -XGET "http://localhost:9200/es-test-logs/_search?pretty" -H 'Content-Type: application/json' -d'{

"size": 1,

"query": {

"bool": {

"must": [

{

"match": {

"tags": "multiline"

}

}

]

}

}

}'

Output should look similar to this:

{

"_index" : "es-test-logs",

"_type" : "_doc",

"_id" : "Kfoa2nIBB7MjzkVP7UPy",

"_score" : 0.046520013,

"_source" : {

"node" : "node-1",

"source" : "r.suppressed",

"host" : "coralogix",

"@timestamp" : "2020-06-22T03:38:16.968Z",

"@version" : "1",

"message" : "[node-1] path: /.kibana/_count, params: {index=.kibana}norg.elasticsearch.action.search.SearchPhaseExecutionException: all shards failedntat org.elasticsearch.action.search.AbstractSearchAsyncAction.onPhaseFailure(AbstractSearchAsyncAction.java:551) [elasticsearch-7.7.0.jar:7.7.0]ntat org.elasticsearch.action.search.AbstractSearchAsyncAction.executeNextPhase(AbstractSearchAsyncAction.java:309) [elasticsearch-7.7.0.jar:7.7.0]ntat org.elasticsearch.action.search.AbstractSearchAsyncAction.onPhaseDone(AbstractSearchAsyncAction.java:580) [elasticsearch-7.7.0.jar:7.7.0]ntat org.elasticsearch.action.search.AbstractSearchAsyncAction.onShardFailure(AbstractSearchAsyncAction.java:393) [elasticsearch-7.7.0.jar:7.7.0]ntat org.elasticsearch.action.search.AbstractSearchAsyncAction.lambda$performPhaseOnShard$0(AbstractSearchAsyncAction.java:223) [elasticsearch-7.7.0.jar:7.7.0]ntat org.elasticsearch.action.search.AbstractSearchAsyncAction$2.doRun(AbstractSearchAsyncAction.java:288) [elasticsearch-7.7.0.jar:7.7.0]ntat org.elasticsearch.common.util.concurrent.AbstractRunnable.run(AbstractRunnable.java:37) [elasticsearch-7.7.0.jar:7.7.0]ntat org.elasticsearch.common.util.concurrent.TimedRunnable.doRun(TimedRunnable.java:44) [elasticsearch-7.7.0.jar:7.7.0]ntat org.elasticsearch.common.util.concurrent.ThreadContext$ContextPreservingAbstractRunnable.doRun(ThreadContext.java:692) [elasticsearch-7.7.0.jar:7.7.0]ntat org.elasticsearch.common.util.concurrent.AbstractRunnable.run(AbstractRunnable.java:37) [elasticsearch-7.7.0.jar:7.7.0]ntat java.util.concurrent.ThreadPoolExecutor.runWorker(ThreadPoolExecutor.java:1130) [?:?]ntat java.util.concurrent.ThreadPoolExecutor$Worker.run(ThreadPoolExecutor.java:630) [?:?]ntat java.lang.Thread.run(Thread.java:832) [?:?]",

"timestamp" : "2020-06-15T17:13:35,457",

"short_message" : "path: /.kibana/_count, params: {index=.kibana}norg.elasticsearch.action.search.SearchPhaseExecutionException: all shards failedntat org.elasticsearch.action.search.AbstractSearchAsyncAction.onPhaseFailure(AbstractSearchAsyncAction.java:551) [elasticsearch-7.7.0.jar:7.7.0]ntat org.elasticsearch.action.search.AbstractSearchAsyncAction.executeNextPhase(AbstractSearchAsyncAction.java:309) [elasticsearch-7.7.0.jar:7.7.0]ntat org.elasticsearch.action.search.AbstractSearchAsyncAction.onPhaseDone(AbstractSearchAsyncAction.java:580) [elasticsearch-7.7.0.jar:7.7.0]ntat org.elasticsearch.action.search.AbstractSearchAsyncAction.onShardFailure(AbstractSearchAsyncAction.java:393) [elasticsearch-7.7.0.jar:7.7.0]ntat org.elasticsearch.action.search.AbstractSearchAsyncAction.lambda$performPhaseOnShard$0(AbstractSearchAsyncAction.java:223) [elasticsearch-7.7.0.jar:7.7.0]ntat org.elasticsearch.action.search.AbstractSearchAsyncAction$2.doRun(AbstractSearchAsyncAction.java:288) [elasticsearch-7.7.0.jar:7.7.0]ntat org.elasticsearch.common.util.concurrent.AbstractRunnable.run(AbstractRunnable.java:37) [elasticsearch-7.7.0.jar:7.7.0]ntat org.elasticsearch.common.util.concurrent.TimedRunnable.doRun(TimedRunnable.java:44) [elasticsearch-7.7.0.jar:7.7.0]ntat org.elasticsearch.common.util.concurrent.ThreadContext$ContextPreservingAbstractRunnable.doRun(ThreadContext.java:692) [elasticsearch-7.7.0.jar:7.7.0]ntat org.elasticsearch.common.util.concurrent.AbstractRunnable.run(AbstractRunnable.java:37) [elasticsearch-7.7.0.jar:7.7.0]ntat java.util.concurrent.ThreadPoolExecutor.runWorker(ThreadPoolExecutor.java:1130) [?:?]ntat java.util.concurrent.ThreadPoolExecutor$Worker.run(ThreadPoolExecutor.java:630) [?:?]ntat java.lang.Thread.run(Thread.java:832) [?:?]",

"type" : "elasticsearch",

"severity" : "WARN",

"tags" : [

"multiline"

],

"path" : "/etc/logstash/conf.d/logstash/elasticsearch_logs/elasticsearch.log"

}

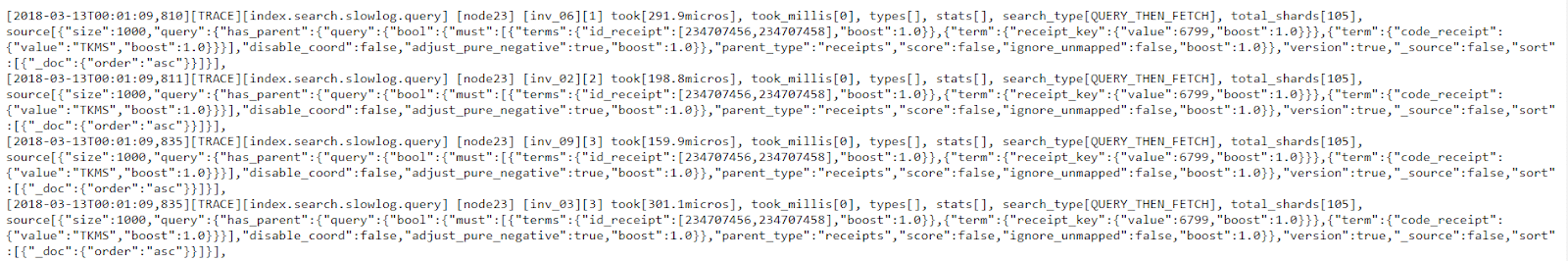

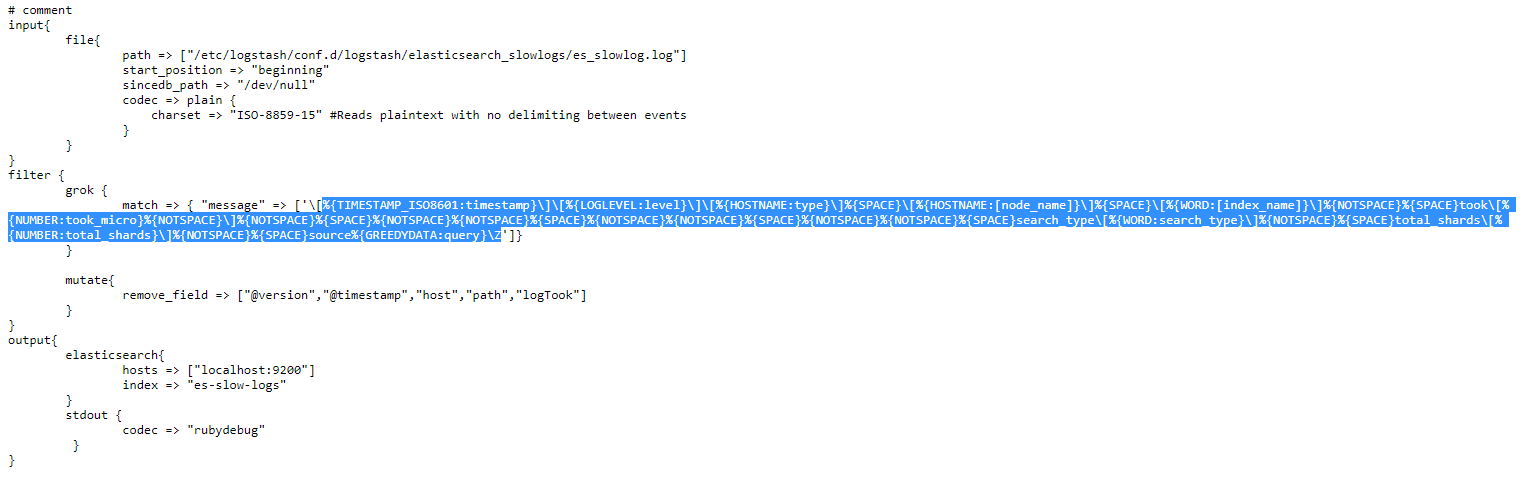

Elasticsearch Slow Logs

Elasticsearch can also generate another type of logs, called slow logs and are used to optimize Elasticsearch search and indexing operations. These are easier to process since they don’t contain multiline messages.

Let’s take a look at a slow log: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/coralogix-resources/logstash/master/elasticsearch_slowlogs/es_slowlog.log.

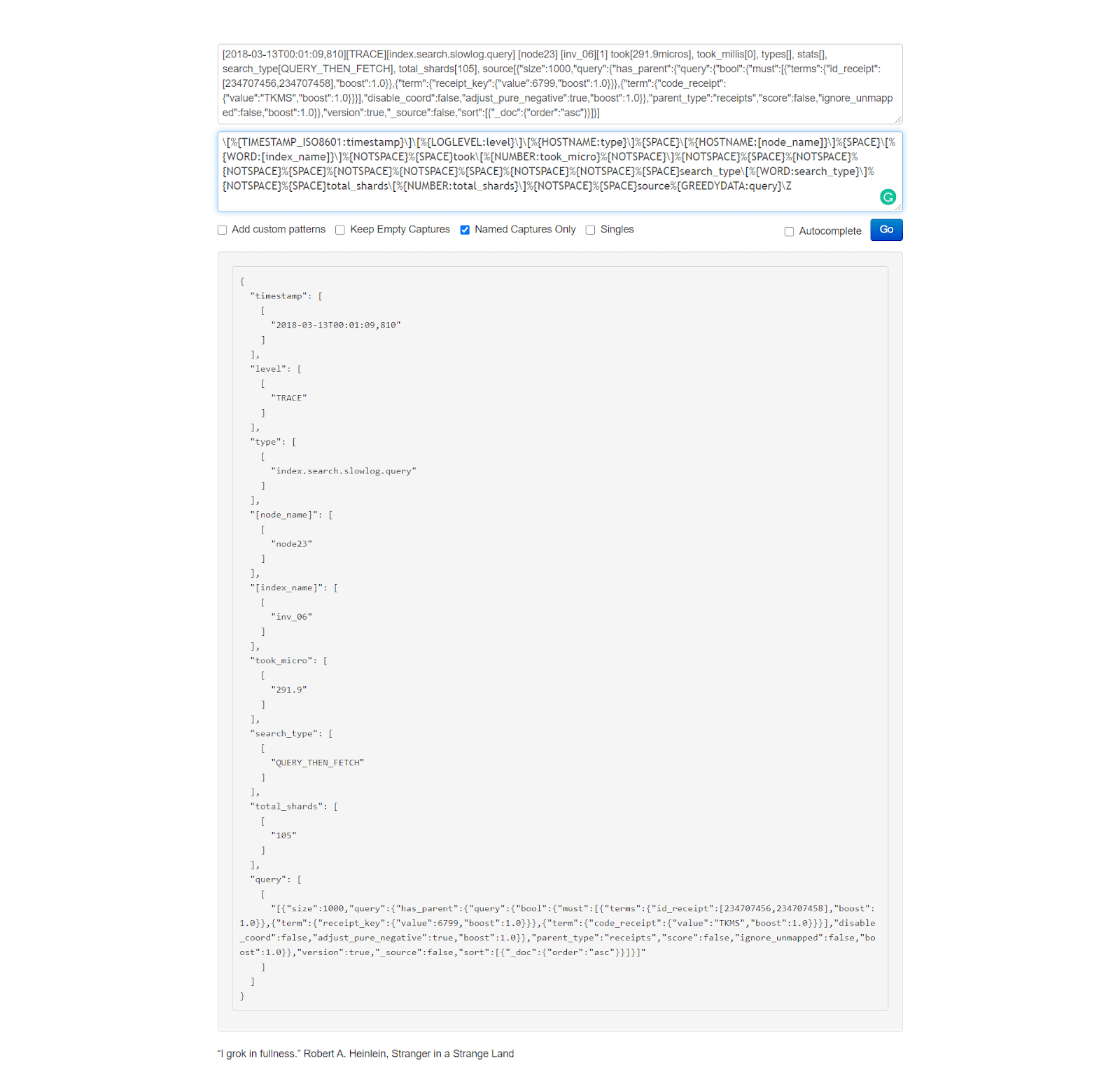

Original image link

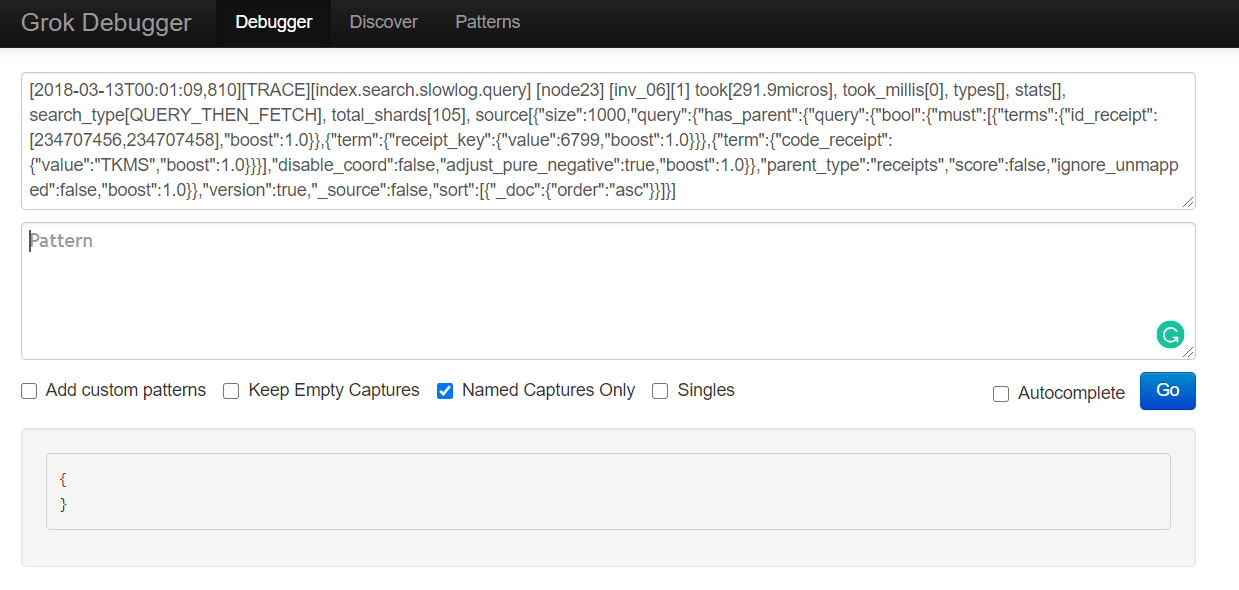

As we did in previous sections, let’s copy the first line and paste it into the first (input) field of the https://grokdebug.herokuapp.com/ website.

[2018-03-13T00:01:09,810][TRACE][index.search.slowlog.query] [node23] [inv_06][1] took[291.9micros], took_millis[0], types[], stats[], search_type[QUERY_THEN_FETCH], total_shards[105], source[{"size":1000,"query":{"has_parent":{"query":{"bool":{"must":[{"terms":{"id_receipt":[234707456,234707458],"boost":1.0}},{"term":{"receipt_key":{"value":6799,"boost":1.0}}},{"term":{"code_receipt":{"value":"TKMS","boost":1.0}}}],"disable_coord":false,"adjust_pure_negative":true,"boost":1.0}},"parent_type":"receipts","score":false,"ignore_unmapped":false,"boost":1.0}},"version":true,"_source":false,"sort":[{"_doc":{"order":"asc"}}]}],

Original image link

Now let’s take a look at the Logstash config we’ll use: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/coralogix-resources/logstash/master/elasticsearch_slowlogs/es-slowlog-final.conf.

Original image link

Let’s copy the Grok pattern within this config and paste it to the second (pattern) field of the https://grokdebug.herokuapp.com/ website.

%{TIMESTAMP_ISO8601:timestamp}][%{LOGLEVEL:level}][%{HOSTNAME:type}]%{SPACE}[%{HOSTNAME:[node_name]}]%{SPACE}[%{WORD:[index_name]}]%{NOTSPACE}%{SPACE}took[%{NUMBER:took_micro}%{NOTSPACE}]%{NOTSPACE}%{SPACE}%{NOTSPACE}%{NOTSPACE}%{SPACE}%{NOTSPACE}%{NOTSPACE}%{SPACE}%{NOTSPACE}%{NOTSPACE}%{SPACE}search_type[%{WORD:search_type}]%{NOTSPACE}%{SPACE}total_shards[%{NUMBER:total_shards}]%{NOTSPACE}%{SPACE}source%{GREEDYDATA:query}Z

Original image link

Now that we saw how this Grok pattern works, let’s run Logstash with our new config file.

sudo /usr/share/logstash/bin/logstash -f /etc/logstash/conf.d/logstash/elasticsearch_slowlogs/es-slowlog-final.conf

As usual, once the parsing is done, we press CTRL+C to exit the application.

Let’s see how the log file was parsed and added to the index:

curl -XGET "http://localhost:9200/es-slow-logs/_search?pretty" -H 'Content-Type: application/json' -d'{ "size": 1}'

The output will look something like this:

{

"_index" : "es-slow-logs",

"_type" : "_doc",

"_id" : "e-JzvHIBocjiYgvgqO4l",

"_score" : 1.0,

"_source" : {

"total_shards" : "105",

"message" : """[2018-03-13T00:01:09,810][TRACE][index.search.slowlog.query] [node23] [inv_06][1] took[291.9micros], took_millis[0], types[], stats[], search_type[QUERY_THEN_FETCH], total_shards[105], source[{"size":1000,"query":{"has_parent":{"query":{"bool":{"must":[{"terms":{"id_receipt":[234707456,234707458],"boost":1.0}},{"term":{"receipt_key":{"value":6799,"boost":1.0}}},{"term":{"code_receipt":{"value":"TKMS","boost":1.0}}}],"disable_coord":false,"adjust_pure_negative":true,"boost":1.0}},"parent_type":"receipts","score":false,"ignore_unmapped":false,"boost":1.0}},"version":true,"_source":false,"sort":[{"_doc":{"order":"asc"}}]}], """,

"node_name" : "node23",

"index_name" : "inv_06",

"level" : "TRACE",

"type" : "index.search.slowlog.query",

"took_micro" : "291.9",

"timestamp" : "2018-03-13T00:01:09,810",

"query" : """[{"size":1000,"query":{"has_parent":{"query":{"bool":{"must":[{"terms":{"id_receipt":[234707456,234707458],"boost":1.0}},{"term":{"receipt_key":{"value":6799,"boost":1.0}}},{"term":{"code_receipt":{"value":"TKMS","boost":1.0}}}],"disable_coord":false,"adjust_pure_negative":true,"boost":1.0}},"parent_type":"receipts","score":false,"ignore_unmapped":false,"boost":1.0}},"version":true,"_source":false,"sort":[{"_doc":{"order":"asc"}}]}], """,

"search_type" : "QUERY_THEN_FETCH"

}

}

MySQL Slow Logs

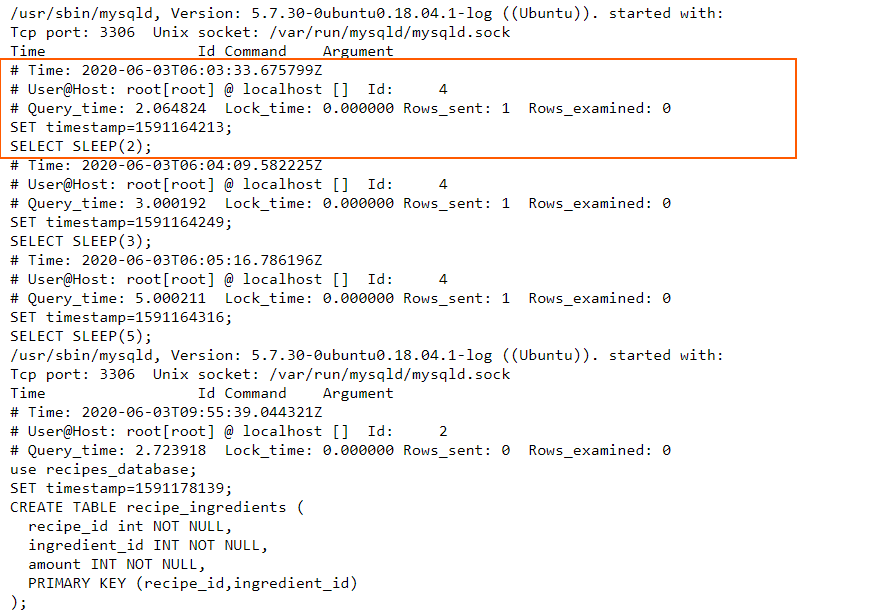

MySQL can also generate slow logs to help with optimization efforts. However, these will log events on multiple lines so we’ll need to use the multiline codec again.

Let’s look at a log file: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/coralogix-resources/logstash/master/mysql_slowlogs/mysql-slow.log.

Original image link here

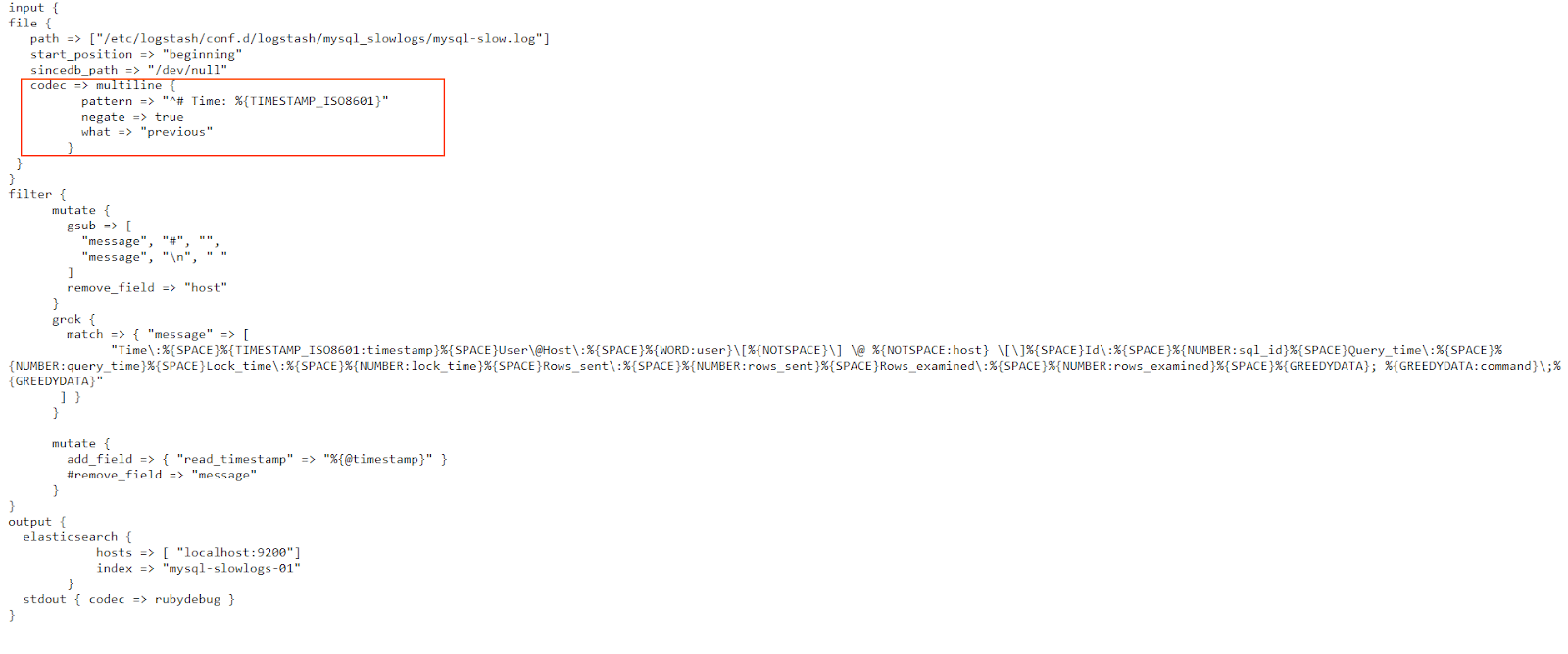

Now let’s look at the Logstash config file: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/coralogix-resources/logstash/master/mysql_slowlogs/mysql-slowlogs.conf.

Original image link

In the multiline codec configuration, we use a Grok pattern. Simply put, we instruct Logstash that if the line doesn’t begin with the “# Time:” string, followed by a timestamp in the TIMESTAMP_ISO8601 format, then this line should be grouped together with previous lines in this event. This makes sense, since all logged events in this slow log begin with that specific timestamp, and then describe what has happened at that time, in the next few lines. Consequently, whenever a new timestamp appears, it signals the end of the current logged event and the beginning of the next.

Let’s run Logstash with this config:

sudo /usr/share/logstash/bin/logstash -f /etc/logstash/conf.d/logstash/mysql_slowlogs/mysql-slowlogs.conf

As always, after the parsing is done, we press CTRL+C to exit the utility.

Let’s look at how the slow log was parsed:

curl -XGET "http://localhost:9200/mysql-slowlogs-01/_search?pretty" -H 'Content-Type: application/json' -d'{

"size":1,

"query": {

"bool": {

"must_not": [

{

"term": {

"tags.keyword": "_grokparsefailure"

}

}

]

}

}

}'

The output should look like this:

{

"_index" : "mysql-slowlogs-01",

"_type" : "_doc",

"_id" : "Zfo42nIBB7MjzkVPGUfK",

"_score" : 0.0,

"_source" : {

"tags" : [

"multiline"

],

"host" : "localhost",

"user" : "root",

"lock_time" : "0.000000",

"timestamp" : "2020-06-03T06:04:09.582225Z",

"read_timestamp" : "2020-06-22T04:10:08.892Z",

"message" : " Time: 2020-06-03T06:04:09.582225Z [email protected]: root[root] @ localhost [] Id: 4 Query_time: 3.000192 Lock_time: 0.000000 Rows_sent: 1 Rows_examined: 0 SET timestamp=1591164249; SELECT SLEEP(3);",

"query_time" : "3.000192",

"rows_examined" : "0",

"path" : "/etc/logstash/conf.d/logstash/mysql_slowlogs/mysql-slow.log",

"sql_id" : "4",

"@version" : "1",

"rows_sent" : "1",

"@timestamp" : "2020-06-22T04:10:08.892Z",

"command" : "SELECT SLEEP(3)"

}

}

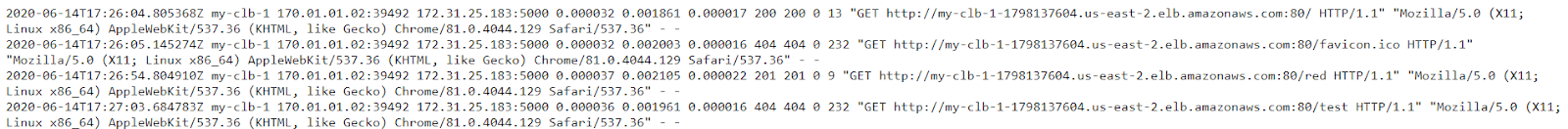

AWS ELB

AWS Elastic Load Balancer is a popular service that intelligently distributes traffic across a number of instances. ELB provides access logs that capture detailed information about requests sent to your load balancer. Each ELB log contains information such as the time the request was received, the client’s IP address, latencies, request paths, and server responses.

Let’s look at an example of such a log: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/coralogix-resources/logstash/master/aws_elb/elb_logs.log

Original image link here

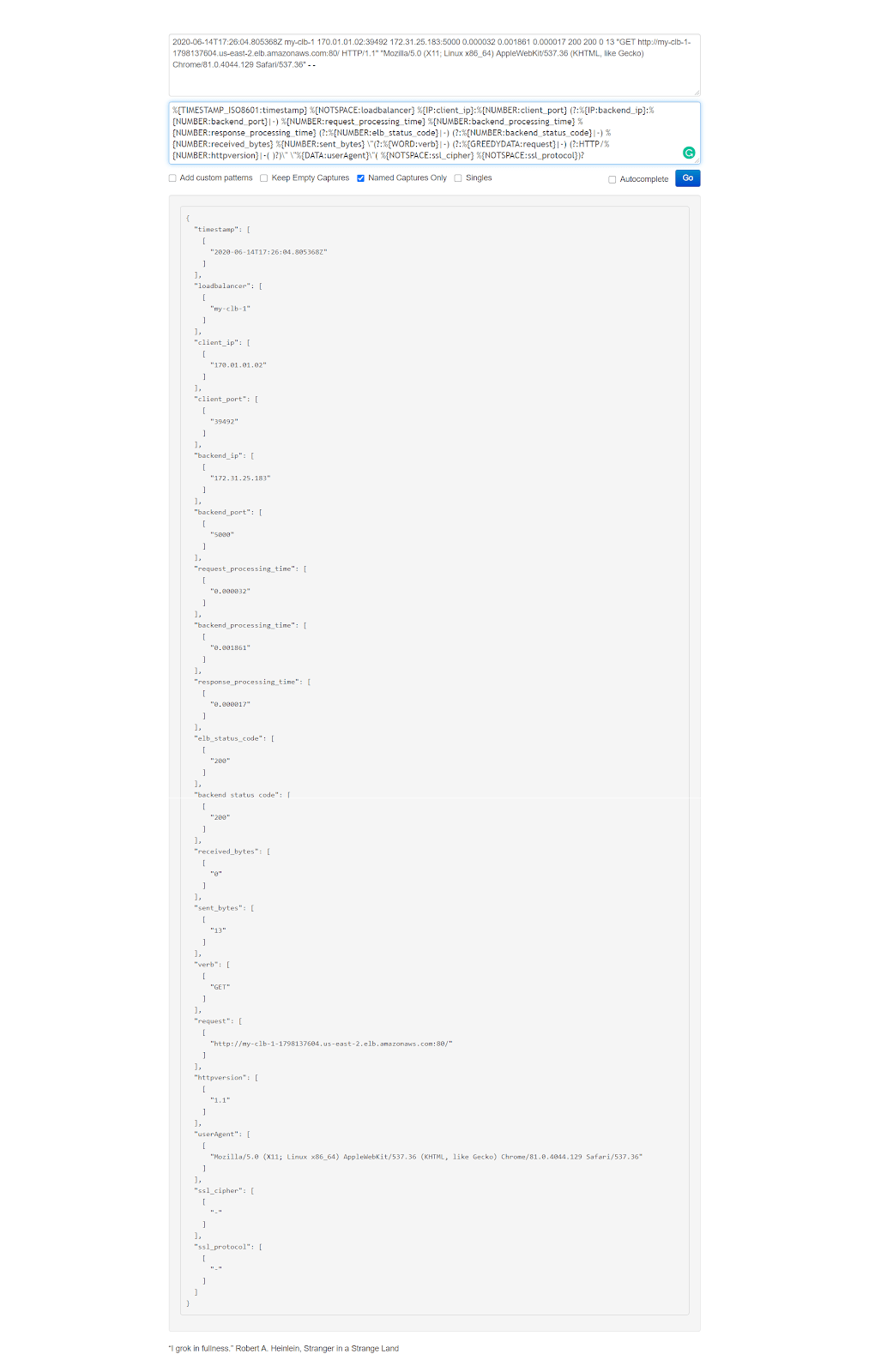

Once again, let’s copy the first line of this log and paste it into the first (input) field of the https://grokdebug.herokuapp.com/ website.

2020-06-14T17:26:04.805368Z my-clb-1 170.01.01.02:39492 172.31.25.183:5000 0.000032 0.001861 0.000017 200 200 0 13 "GET http://my-clb-1-1798137604.us-east-2.elb.amazonaws.com:80/ HTTP/1.1" "Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/81.0.4044.129 Safari/537.36" - -

Original image link here

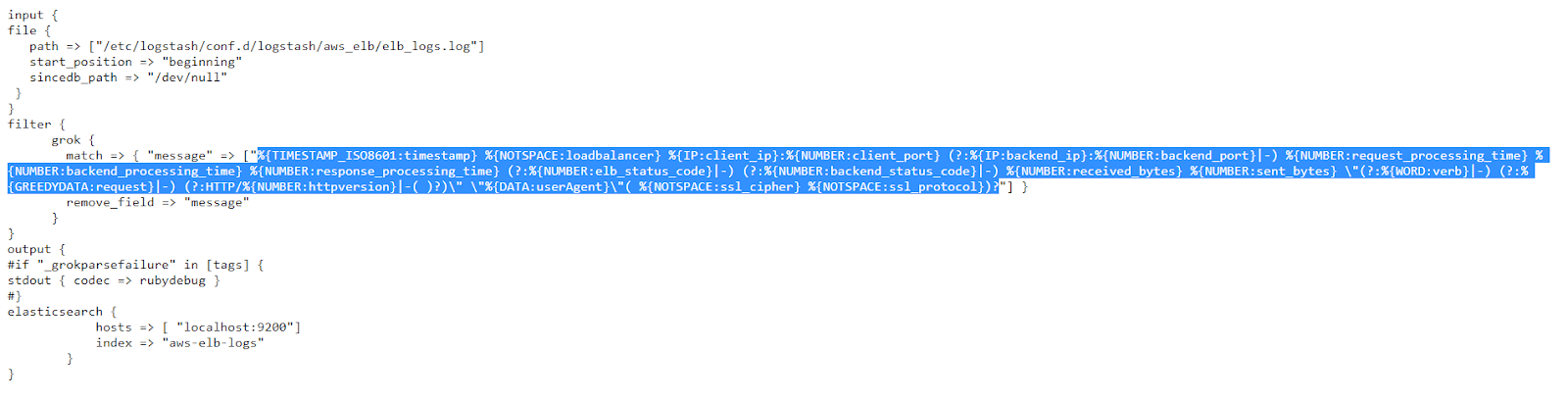

The Logstash config we’ll use is this one: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/coralogix-resources/logstash/master/aws_elb/aws-elb.conf.

Original image link here

From this config, we can copy the Grok pattern and paste it into the second (pattern) field of the https://grokdebug.herokuapp.com/ website.

%{TIMESTAMP_ISO8601:timestamp} %{NOTSPACE:loadbalancer} %{IP:client_ip}:%{NUMBER:client_port} (?:%{IP:backend_ip}:%{NUMBER:backend_port}|-) %{NUMBER:request_processing_time} %{NUMBER:backend_processing_time} %{NUMBER:response_processing_time} (?:%{NUMBER:elb_status_code}|-) (?:%{NUMBER:backend_status_code}|-) %{NUMBER:received_bytes} %{NUMBER:sent_bytes} "(?:%{WORD:verb}|-) (?:%{GREEDYDATA:request}|-) (?:HTTP/%{NUMBER:httpversion}|-( )?)" "%{DATA:userAgent}"( %{NOTSPACE:ssl_cipher} %{NOTSPACE:ssl_protocol})?

Original image link here

Let’s run Logstash:

sudo /usr/share/logstash/bin/logstash -f /etc/logstash/conf.d/logstash/aws_elb/aws-elb.conf

We press CTRL+C once it finishes its job and then take a look at the index to see how the log has been parsed:

curl -XGET "http://localhost:9200/aws-elb-logs/_search?pretty" -H 'Content-Type: application/json' -d'

{

"size": 1,

"query": {

"bool": {

"must_not": [

{

"term": {

"tags": {

"value": "_grokparsefailure"

}

}

}

]

}

}

}'

The output should look similar to this:

{

"_index" : "aws-elb-logs",

"_type" : "_doc",

"_id" : "avpQ2nIBB7MjzkVPIEc-",

"_score" : 0.0,

"_source" : {

"request_processing_time" : "0.000032",

"timestamp" : "2020-06-14T17:26:05.145274Z",

"sent_bytes" : "232",

"@version" : "1",

"userAgent" : "Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/81.0.4044.129 Safari/537.36",

"elb_status_code" : "404",

"ssl_protocol" : "-",

"path" : "/etc/logstash/conf.d/logstash/aws_elb/elb_logs.log",

"response_processing_time" : "0.000016",

"backend_processing_time" : "0.002003",

"client_port" : "39492",

"verb" : "GET",

"received_bytes" : "0",

"backend_ip" : "172.31.25.183",

"backend_status_code" : "404",

"client_ip" : "170.01.01.02",

"backend_port" : "5000",

"host" : "coralogix",

"loadbalancer" : "my-clb-1",

"request" : "http://my-clb-1-1798137604.us-east-2.elb.amazonaws.com:80/favicon.ico",

"ssl_cipher" : "-",

"httpversion" : "1.1",

"@timestamp" : "2020-06-22T04:36:23.160Z"

}

}

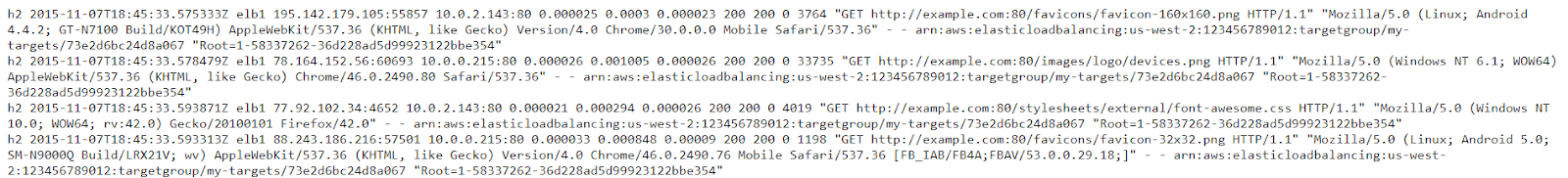

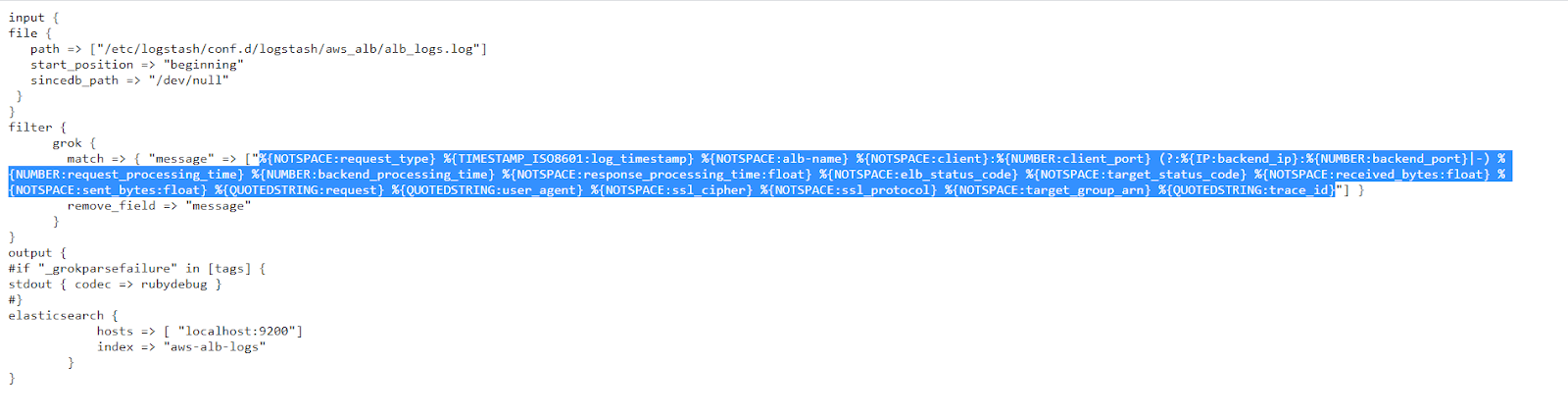

AWS ALB

Amazon also offers an Application Load Balancer that generates its own logs. These are very similar to the ELB logs and we can see an example here: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/coralogix-resources/logstash/master/aws_alb/alb_logs.log.

Original image link here

The config file we will use can be seen here: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/coralogix-resources/logstash/master/aws_alb/aws-alb.conf.

Original image link here

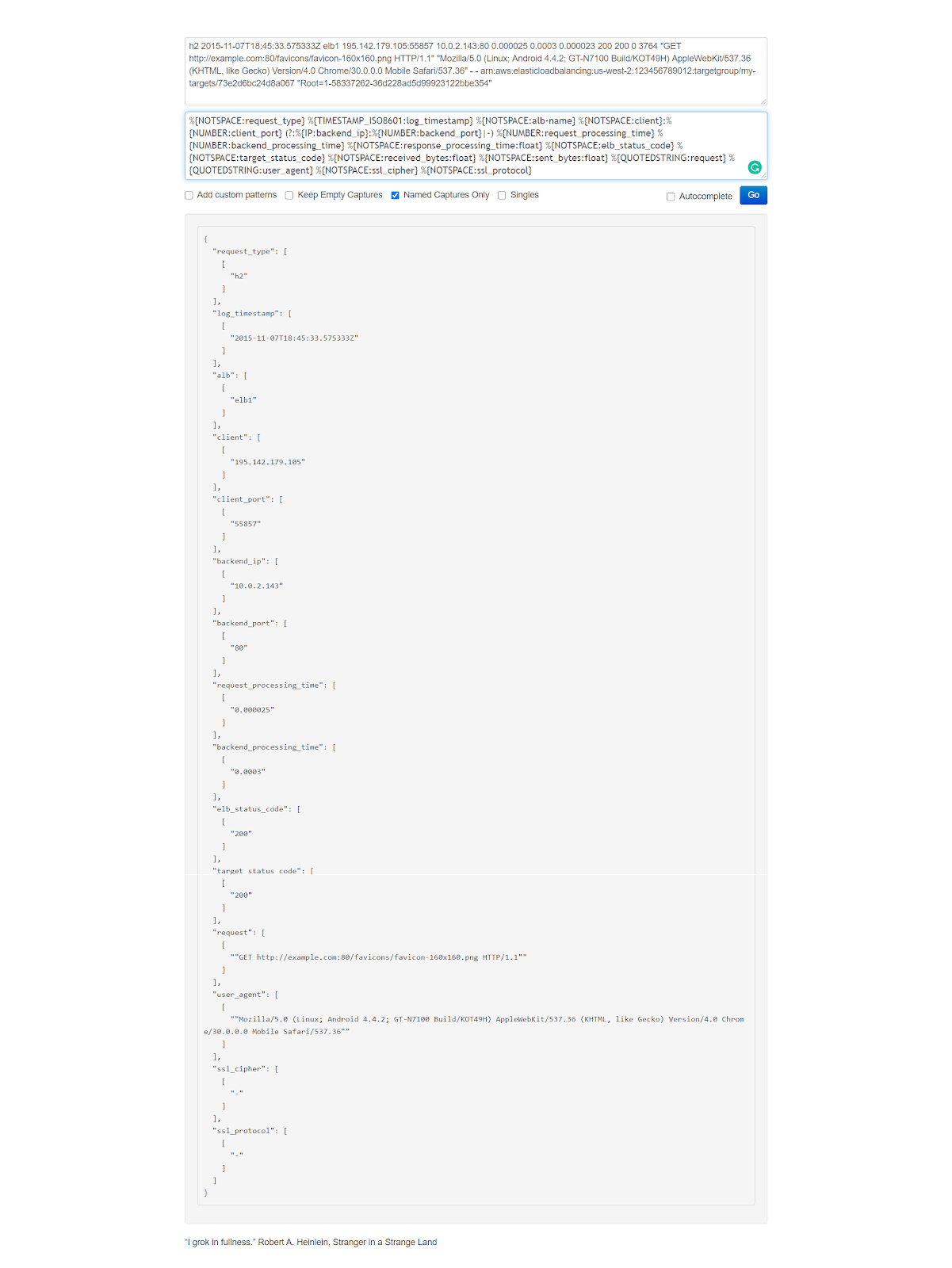

If you want to test things out in the https://grokdebug.herokuapp.com/ website, the input line you can copy and paste into the first field is the following:

h2 2015-11-07T18:45:33.575333Z elb1 195.142.179.105:55857 10.0.2.143:80 0.000025 0.0003 0.000023 200 200 0 3764 "GET http://example.com:80/favicons/favicon-160x160.png HTTP/1.1" "Mozilla/5.0 (Linux; Android 4.4.2; GT-N7100 Build/KOT49H) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/4.0 Chrome/30.0.0.0 Mobile Safari/537.36" - - arn:aws:elasticloadbalancing:us-west-2:123456789012:targetgroup/my-targets/73e2d6bc24d8a067 "Root=1-58337262-36d228ad5d99923122bbe354"

And the Grok pattern is:

%{NOTSPACE:request_type} %{TIMESTAMP_ISO8601:log_timestamp} %{NOTSPACE:alb-name} %{NOTSPACE:client}:%{NUMBER:client_port} (?:%{IP:backend_ip}:%{NUMBER:backend_port}|-) %{NUMBER:request_processing_time} %{NUMBER:backend_processing_time} %{NOTSPACE:response_processing_time:float} %{NOTSPACE:elb_status_code} %{NOTSPACE:target_status_code} %{NOTSPACE:received_bytes:float} %{NOTSPACE:sent_bytes:float} %{QUOTEDSTRING:request} %{QUOTEDSTRING:user_agent} %{NOTSPACE:ssl_cipher} %{NOTSPACE:ssl_protocol} %{NOTSPACE:target_group_arn} %{QUOTEDSTRING:trace_id}

Original image link here

Once again, let’s run Logstash with the new config:

sudo /usr/share/logstash/bin/logstash -f /etc/logstash/conf.d/logstash/aws_alb/aws-alb.conf

We’ll press CTRL+C, once it’s done, and then take a look at how the log has been parsed and imported to the index:

curl -XGET "http://localhost:9200/aws-alb-logs/_search?pretty" -H 'Content-Type: application/json' -d'

{

"size": 1,

"query": {

"bool": {

"must_not": [

{"term": {

"tags": {

"value": "_grokparsefailure"

}

}

}

]

}

}

}'

The output should look something like this:

{

"_index" : "aws-alb-logs",

"_type" : "_doc",

"_id" : "dvpZ2nIBB7MjzkVPF0ex",

"_score" : 0.0,

"_source" : {

"client" : "78.164.152.56",

"path" : "/etc/logstash/conf.d/logstash/aws_alb/alb_logs.log",

"client_port" : "60693",

"ssl_protocol" : "-",

"target_group_arn" : "arn:aws:elasticloadbalancing:us-west-2:123456789012:targetgroup/my-targets/73e2d6bc24d8a067",

"backend_port" : "80",

"trace_id" : ""Root=1-58337262-36d228ad5d99923122bbe354"",

"backend_processing_time" : "0.001005",

"response_processing_time" : 2.6E-5,

"@timestamp" : "2020-06-22T04:46:09.813Z",

"@version" : "1",

"request_processing_time" : "0.000026",

"received_bytes" : 0.0,

"sent_bytes" : 33735.0,

"alb-name" : "elb1",

"log_timestamp" : "2015-11-07T18:45:33.578479Z",

"request_type" : "h2",

"user_agent" : ""Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; WOW64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/46.0.2490.80 Safari/537.36"",

"request" : ""GET http://example.com:80/images/logo/devices.png HTTP/1.1"",

"elb_status_code" : "200",

"ssl_cipher" : "-",

"host" : "coralogix",

"backend_ip" : "10.0.0.215",

"target_status_code" : "200"

}

}

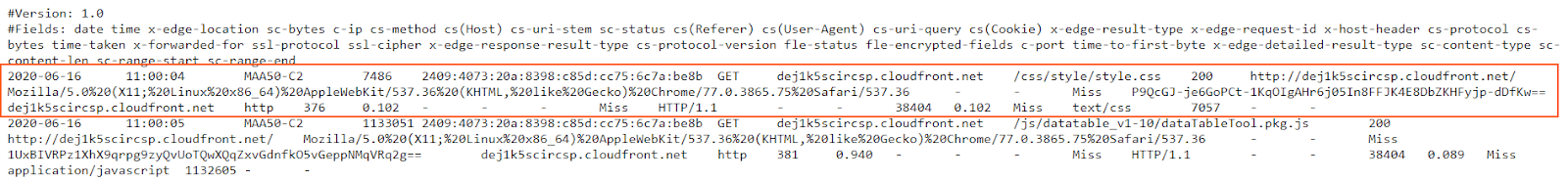

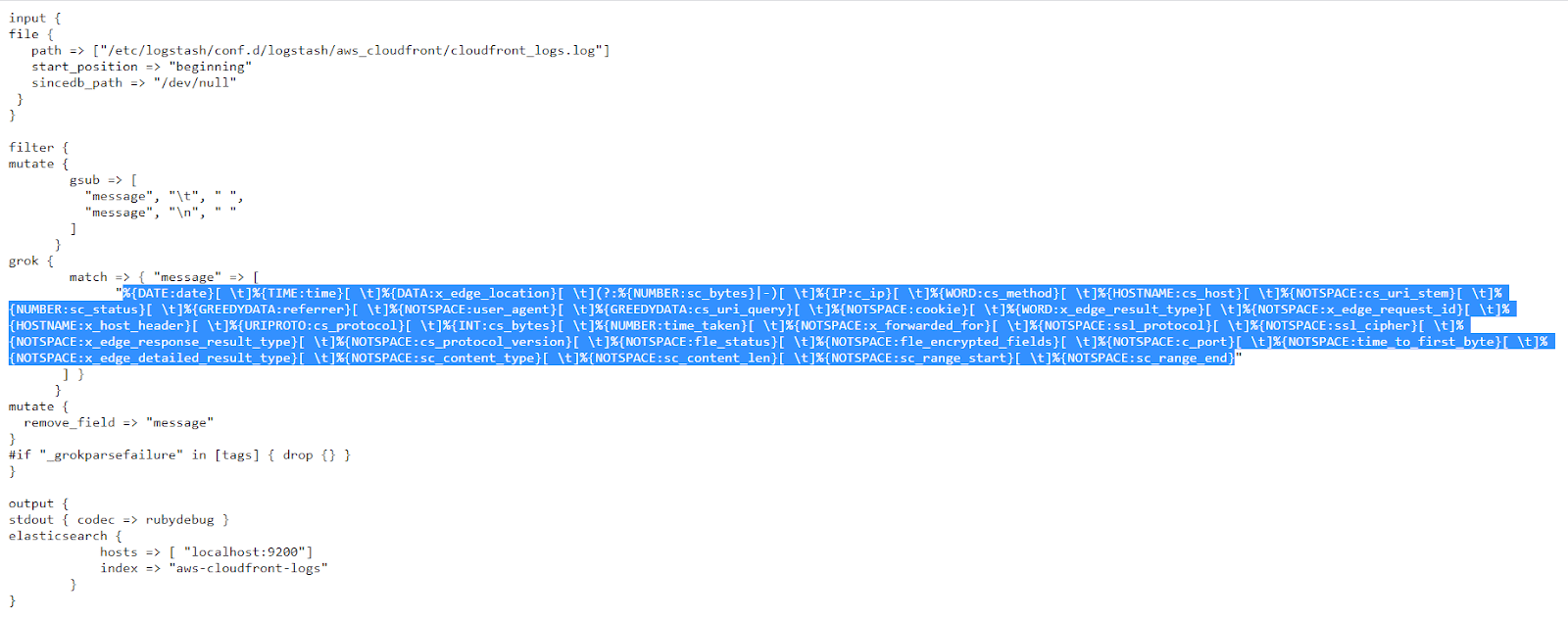

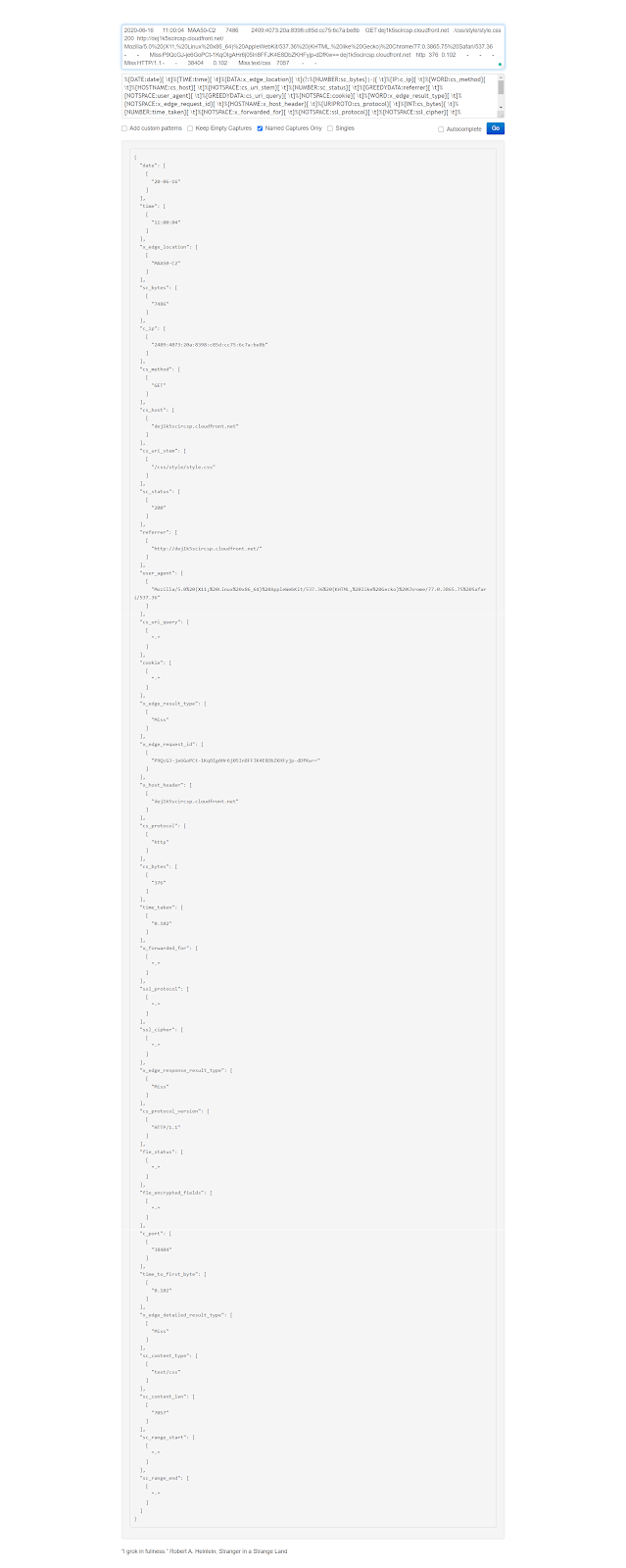

AWS CloudFront

Amazon’s CloudFront content delivery network generates useful logs to help ensure availability, performance, and in security audits.

Here is a sample log: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/coralogix-resources/logstash/master/aws_cloudfront/cloudfront_logs.log.

Original image link here

The Logstash config file can be viewed here: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/coralogix-resources/logstash/master/aws_cloudfront/aws-cloudfront.conf.

Original image link

Once again, If you want to test how things work, in the https://grokdebug.herokuapp.com/ website, the input line you can copy and paste into the first field is this one:

2020-06-16 11:00:04 MAA50-C2 7486 2409:4073:20a:8398:c85d:cc75:6c7a:be8b GET dej1k5scircsp.cloudfront.net /css/style/style.css 200 http://dej1k5scircsp.cloudfront.net/ Mozilla/5.0%20(X11;%20Linux%20x86_64)%20AppleWebKit/537.36%20(KHTML,%20like%20Gecko)%20Chrome/77.0.3865.75%20Safari/537.36 - - Miss P9QcGJ-je6GoPCt-1KqOIgAHr6j05In8FFJK4E8DbZKHFyjp-dDfKw== dej1k5scircsp.cloudfront.net http 376 0.102 - - - Miss HTTP/1.1 - - 38404 0.102 Miss text/css 7057 - -

And the Grok pattern is:

%{DATE:date}[ t]%{TIME:time}[ t]%{DATA:x_edge_location}[ t](?:%{NUMBER:sc_bytes}|-)[ t]%{IP:c_ip}[ t]%{WORD:cs_method}[ t]%{HOSTNAME:cs_host}[ t]%{NOTSPACE:cs_uri_stem}[ t]%{NUMBER:sc_status}[ t]%{GREEDYDATA:referrer}[ t]%{NOTSPACE:user_agent}[ t]%{GREEDYDATA:cs_uri_query}[ t]%{NOTSPACE:cookie}[ t]%{WORD:x_edge_result_type}[ t]%{NOTSPACE:x_edge_request_id}[ t]%{HOSTNAME:x_host_header}[ t]%{URIPROTO:cs_protocol}[ t]%{INT:cs_bytes}[ t]%{NUMBER:time_taken}[ t]%{NOTSPACE:x_forwarded_for}[ t]%{NOTSPACE:ssl_protocol}[ t]%{NOTSPACE:ssl_cipher}[ t]%{NOTSPACE:x_edge_response_result_type}[ t]%{NOTSPACE:cs_protocol_version}[ t]%{NOTSPACE:fle_status}[ t]%{NOTSPACE:fle_encrypted_fields}[ t]%{NOTSPACE:c_port}[ t]%{NOTSPACE:time_to_first_byte}[ t]%{NOTSPACE:x_edge_detailed_result_type}[ t]%{NOTSPACE:sc_content_type}[ t]%{NOTSPACE:sc_content_len}[ t]%{NOTSPACE:sc_range_start}[ t]%{NOTSPACE:sc_range_end}

Original image link here

Now let’s run Logstash:

sudo /usr/share/logstash/bin/logstash -f /etc/logstash/conf.d/logstash/aws_cloudfront/aws-cloudfront.conf

As always, we press CTRL+C once it finishes its job.

Once again, let’s take a look at how the log has been parsed and inserted into the index:

curl -XGET "http://localhost:9200/aws-cloudfront-logs/_search?pretty" -H 'Content-Type: application/json' -d'

{

"query": {

"bool": {

"must_not": [

{"term": {

"tags": {

"value": "_grokparsefailure"

}

}

}

]

}

}

}'

Part of the output should be similar to the following:

{

"_index" : "aws-cloudfront-logs",

"_type" : "_doc",

"_id" : "Da1s4nIBnKKcJetIb-p9",

"_score" : 0.0,

"_source" : {

"time_to_first_byte" : "0.000",

"cs_uri_stem" : "/favicon.ico",

"x_edge_request_id" : "vhpLn3lotn2w4xMOxQg77DfFpeEtvX49mKzz5h7iwNXguHQpxD6QPQ==",

"sc_bytes" : "910",

"@version" : "1",

"cs_host" : "dej1k5scircsp.cloudfront.net",

"c_ip" : "2409:4073:20a:8398:c85d:cc75:6c7a:be8b",

"user_agent" : "Mozilla/5.0%20(X11;%20Linux%20x86_64)%20AppleWebKit/537.36%20(KHTML,%20like%20Gecko)%20Chrome/77.0.3865.75%20Safari/537.36",

"sc_range_start" : "-",

"c_port" : "57406",

"x_edge_result_type" : "Error",

"referrer" : "http://dej1k5scircsp.cloudfront.net/",

"x_edge_location" : "MAA50-C2",

"path" : "/etc/logstash/conf.d/logstash/aws_cloudfront/cloudfront_logs.log",

"cs_protocol" : "http",

"time_taken" : "0.001",

"x_forwarded_for" : "-",

"time" : "10:58:07",

"cookie" : "-",

"sc_status" : "502",

"date" : "20-06-16",

"sc_range_end" : "-",

"x_edge_detailed_result_type" : "Error",

"ssl_cipher" : "-",

"cs_method" : "GET",

"x_host_header" : "dej1k5scircsp.cloudfront.net",

"sc_content_len" : "507",

"ssl_protocol" : "-",

"fle_status" : "-",

"@timestamp" : "2020-06-23T18:24:15.784Z",

"fle_encrypted_fields" : "-",

"cs_bytes" : "389",

"x_edge_response_result_type" : "Error",

"host" : "coralogix",

"cs_uri_query" : "-",

"sc_content_type" : "text/html",

"cs_protocol_version" : "HTTP/1.1"

}

}

Cleaning Up

Before continuing with the next lesson, let’s clean up the resources we created here.

First, we’ll delete the directory where we stored our sample log files and Logstash configurations:

sudo rm -r /etc/logstash/conf.d/logstash/

Next, let’s delete all the new indices we created:

curl -XDELETE localhost:9200/nginx-access-logs-02 curl -XDELETE localhost:9200/iis-log curl -XDELETE localhost:9200/mongo-logs-01 curl -XDELETE localhost:9200/apache-logs curl -XDELETE localhost:9200/es-test-logs curl -XDELETE localhost:9200/es-slow-logs curl -XDELETE localhost:9200/mysql-slowlogs-01 curl -XDELETE localhost:9200/aws-elb-logs curl -XDELETE localhost:9200/aws-alb-logs curl -XDELETE localhost:9200/aws-cloudfront-logs

Conclusion

I hope this arsenal of Grok patterns for common log types are useful for most of your future Logstash needs. Keep in mind that if the log you encounter is just slightly different, only slight changes need to be made to these patterns, which you can use as your starting templates.

In Part 2, we learned about monitoring an Apache Access Log using a File Input Plugin and Grok Filter Plugin.

Now, we will learn a little about creating Grok Filters for Custom Log Format, and more about Centralized Logging, which will require a Central Logstash Server, and various shipper servers, which will be shipping logs to Centralized Logstash.

Making Custom Grok Filter for Custom Log Formats

When you are dealing with different applications, it is possible that Log Formats may differ. Even, the Date Format in the Log may vary from application to application.

So, in that case, we have to create our own Grok Pattern for parsing our log.

Parsing Nginx Error Log

We will use a handy tool known as Grok Debugger for building our pattern. In the already available Grok patterns, we don’t have one for Nginx Error Logs. So, let us make a pattern, that will parse a Nginx Error Log for us.

Let us parse the given below error log from nginx:

2016/08/29 06:25:15 [error] 16854#0: *2676 FastCGI sent in stderr: "Unable to open primary script: /usr/share/nginx/www/example.php (No such file or directory)" while reading response header from upstream, client: 173.245.49.176, server: _, request: "GET /example.php HTTP/1.1", upstream: "fastcgi://unix:/var/run/php5-fpm.sock:", host: "example.com", referrer: "https://example.com/example.php"

The Grok Pattern, that I made using Grok Debugger is as follow:

(?<timestamp>%{YEAR}/%{MONTHNUM}/%{MONTHDAY} %{TIME}) [%{LOGLEVEL:log_level}] %{NUMBER:process_id}#%{NUMBER:thread_id}: (*%{NUMBER:connection_counter} )?(?<error_description>((?!client).)*)(client: %{IPORHOST:client_ip})((?!server).)*(server: %{USERNAME:server_name})((?!request).)*(request: "(?:%{WORD:request_method} %{NOTSPACE:request_uri}(?: HTTP/%{NUMBER:httpversion})?|%{DATA:rawrequest})")((?!upstream).)*(upstream: "(?<upstream>[^"]+)")((?!host).)*(host: "(?<host_name>[^"]+)")((?!referrer).)*(referrer: "(?<referrer>[^"]+)")

After Parsing the Data using this Grok filter, you will see the output as:

{

"timestamp": "2016/08/29 06:25:15",

"log_level": "error",

"process_id": "16854",

"thread_id": "0",

"connection_counter": "2676",

"error_description": "FastCGI sent in stderr: "Unable to open primary script: /usr/share/nginx/www/example.php (No such file or directory)" while reading response header from upstream, ",

"client_ip": "173.245.49.176",

"server_name": "_",

"request_method": "GET",

"request_uri": "/example.php",

"httpversion": "1.1",

"upstream": "fastcgi://unix:/var/run/php5-fpm.sock:",

"host_name": "example.com",

"referrer": "https://example.com/example.php"

}

So, this is how we make use of Grok Filter for different Log Formats. Now, lets move forward to Centralized Logging.

Centralized Logging – Basic Setup

In a very basic setup of Centralized Logging, there is a master Logstash Server which can be used for either of the given 2 purposes:

- Take Logs from Broker, Filter/Parse and Index them to Storage

- Take Logs from Broker and Index them to Storage without parsing

There are multiple Logstash Shippers, which are responsible for sending the Logs to the Broker Server(a persistent storage).

The Broker is responsible for centralized storage for persistence of data, so that you do not lose logs in case of failure. You can use some popular technologies for your broker like Redis, RabbitMQ etc.

When it comes to Filtering and Parsing of Logs, you have 2 choices here:

- Shipper simply forward the Logs and Centralized Logstash Parses/Filters and indexes the data to Storage

- Shipper Parses/Filters the Logs and Centralized Logstash simply indexes the data to Storage

We will go with the 1st approach for our example. The Shippers will act like agents on different servers, so we won’t put much load on them by parsing the logs on them. The Centralized Logstash will serve the purpose for that.

Shipper Configuration

The Shippers will read the Logs, say from a File, and send it to Redis. The Shipper Logstash configuration will look like:

input {

file {

path => ["/path_to_your_log_file.log"]

}

}

output {

redis {

codec => line {

format => "%{message}"

}

data_type => list

host => ["Redis Host IP Here"]

key => "logstash"

}

}

Centralized Logstash Configuration

The Centralized Logstash will fetch the Logs from Redis, performs all the Filtering/Parsing and then send it to ElasticSearch:

input {

redis {

data_type => list

host => ["Redis Host IP here"]

key => "logstash"

}

}

filter {

# Write all the Filters to parse the Logs here

# Example: Parsing Apache Log

grok {

match => {

"message" => "%{COMBINEDAPACHELOG}"

}

}

}

output {

elasticsearch {

hosts => ["Elastic IP here"]

index => "logstash-%{+YYYY.MM}"

document_type => "%{log_type}"

codec => "rubydebug"

}

}

Centralized Logging – Custom Setup

As we will be sending logs from various sources, it is possible that every source doesn’t support java. Also, to avoid having java installed on all the sources, which is required by Shipper(Logstash), we will use some alternate lightweight solution.

Using Syslog-ng

On the machines, where Java is not installed or supported, we will use syslog-ng as our Shipper to monitor our Log files and send them to Centralized Logstash.

Example Syslog-ng Configuration:

@version:3.5

source apache_logs_input {

file("/var/log/apache2/access.log" follow-freq(1) flags(no-parse));

file("/var/log/apache2/error.log" follow-freq(1) flags(no-parse));

};

destination apache_output_tcp_logstash {

tcp("192.168.1.101" port(27015));

};

log {

source(apache_logs_input);

destination(apache_output_tcp_logstash);

};

Using Log4J

On the Java based application, we use Logging utilities like JULI(Java Utility Logging Implementation), Log4J etc, for our logging purposes. You can use these utilities to directly send Logs to Centralized Logstash via TCP. You can send it using SocketAppender or via any other possible way.

Example Log4J Configuration:

log4j.rootLogger = LOG4J_SOCKET log4j.appender.LOG4J_SOCKET = org.apache.log4j.net.SocketAppender log4j.appender.LOG4J_SOCKET.port = 27017 log4j.appender.LOG4J_SOCKET.remoteHost = 192.168.1.101

Centralized Logstash Configuration

Now, we can retrieve these Logs sent by Syslog-ng and Log4J in our Logstash easily using the TCP Input Plugin and Log4j Input Plugin.

Example Configuration:

input {

tcp {

port => 27015

mode => "server"

}

log4j {

mode => "server"

port => 27017

}

}

filter {

# Some Filters here

}

output {

# Output somewhere

elasticsearch {

hosts => ["Elastic IP here"]

index => "logstash-%{+YYYY.MM}"

document_type => "%{log_type}"

codec => "rubydebug"

}

}

What Next?

Now, when we have learned enough about using Logstash to Filter/Parse Logs and send them to ElasticSearch, we will see how we can pull the best out of it using Kibana, in our next blog.

Tags: elasticsearch, kibana, log4j, logging, logs, logstash, syslog, syslog-ng