The throw statement throws a user-defined exception.

Execution of the current function will stop (the statements after throw

won’t be executed), and control will be passed to the first catch

block in the call stack. If no catch block exists among caller functions,

the program will terminate.

Try it

Syntax

expression-

The expression to throw.

Description

Use the throw statement to throw an exception. When you throw an

exception, expression specifies the value of the exception. Each

of the following throws an exception:

throw "Error2"; // generates an exception with a string value

throw 42; // generates an exception with the value 42

throw true; // generates an exception with the value true

throw new Error("Required"); // generates an error object with the message of Required

Also note that the throw statement is affected by

automatic semicolon insertion (ASI)

as no line terminator between the throw keyword and the expression is allowed.

Examples

Throw an object

You can specify an object when you throw an exception. You can then reference the

object’s properties in the catch block. The following example creates an

object of type UserException and uses it in a throw statement.

function UserException(message) {

this.message = message;

this.name = "UserException";

}

function getMonthName(mo) {

mo--; // Adjust month number for array index (1 = Jan, 12 = Dec)

const months = [

"Jan", "Feb", "Mar", "Apr", "May", "Jun",

"Jul", "Aug", "Sep", "Oct", "Nov", "Dec",

];

if (months[mo] !== undefined) {

return months[mo];

} else {

throw new UserException("InvalidMonthNo");

}

}

let monthName;

try {

// statements to try

const myMonth = 15; // 15 is out of bound to raise the exception

monthName = getMonthName(myMonth);

} catch (e) {

monthName = "unknown";

console.error(e.message, e.name); // pass exception object to err handler

}

Another example of throwing an object

The following example tests an input string for a U.S. zip code. If the zip code uses

an invalid format, the throw statement throws an exception by creating an object of type

ZipCodeFormatException.

/*

* Creates a ZipCode object.

*

* Accepted formats for a zip code are:

* 12345

* 12345-6789

* 123456789

* 12345 6789

*

* If the argument passed to the ZipCode constructor does not

* conform to one of these patterns, an exception is thrown.

*/

class ZipCode {

static pattern = /[0-9]{5}([- ]?[0-9]{4})?/;

constructor(zip) {

zip = String(zip);

const match = zip.match(ZipCode.pattern);

if (!match) {

throw new ZipCodeFormatException(zip);

}

// zip code value will be the first match in the string

this.value = match[0];

}

valueOf() {

return this.value;

}

toString() {

return this.value;

}

}

class ZipCodeFormatException extends Error {

constructor(zip) {

super(`${zip} does not conform to the expected format for a zip code`);

}

}

/*

* This could be in a script that validates address data

* for US addresses.

*/

const ZIPCODE_INVALID = -1;

const ZIPCODE_UNKNOWN_ERROR = -2;

function verifyZipCode(z) {

try {

z = new ZipCode(z);

} catch (e) {

const isInvalidCode = e instanceof ZipCodeFormatException;

return isInvalidCode ? ZIPCODE_INVALID : ZIPCODE_UNKNOWN_ERROR;

}

return z;

}

a = verifyZipCode(95060); // 95060

b = verifyZipCode(9560); // -1

c = verifyZipCode("a"); // -1

d = verifyZipCode("95060"); // 95060

e = verifyZipCode("95060 1234"); // 95060 1234

Rethrow an exception

You can use throw to rethrow an exception after you catch it. The

following example catches an exception with a numeric value and rethrows it if the value

is over 50. The rethrown exception propagates up to the enclosing function or to the top

level so that the user sees it.

try {

throw n; // throws an exception with a numeric value

} catch (e) {

if (e <= 50) {

// statements to handle exceptions 1-50

} else {

// cannot handle this exception, so rethrow

throw e;

}

}

Specifications

| Specification |

|---|

| ECMAScript Language Specification # sec-throw-statement |

Browser compatibility

BCD tables only load in the browser

See also

When executing JavaScript code, errors will most definitely occur. These errors can occur due to a fault from the programmer’s side or the input is wrong or even if there is a problem with the logic of the program. But all errors can be solved and to do so we use five statements that will now be explained.

- The try statement lets you test a block of code to check for errors.

- The catch statement lets you handle the error if any are present.

- The throw statement lets you make your own errors.

- The finally statement lets you execute code, after try and catch.

The finally block runs regardless of the result of the try-catch block.

Below are examples, that illustrate the JavaScript Errors Throw and Try to Catch:

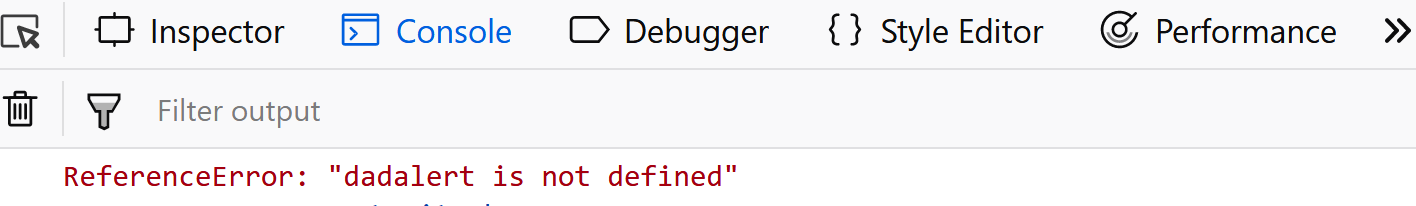

Example 1:

HTML

<script type="text/javascript" charset="utf-8">

try {

dadalert("Welcome Fellow Geek!");

}

catch(err) {

console.log(err);

}

</script>

Output: In the above code, we make use of ‘dadalert’ which is not a reserved keyword and is neither defined hence we get the error.

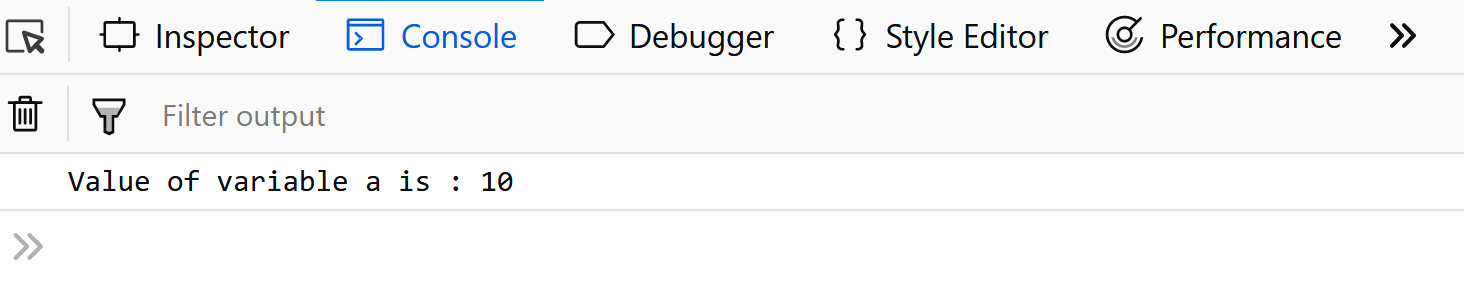

HTML

<script>

function geekFunc() {

let a = 10;

try {

console.log("Value of variable a is : " + a );

}

catch ( e ) {

console.log("Error: " + e.description );

}

}

geekFunc();

</script>

Output: In the above code, our catch block will not run as there’s no error in the above code and hence we get the output ‘Value of variable a is: 10’.

try {

Try Block to check for errors.

}

catch(err) {

Catch Block to display errors.

}

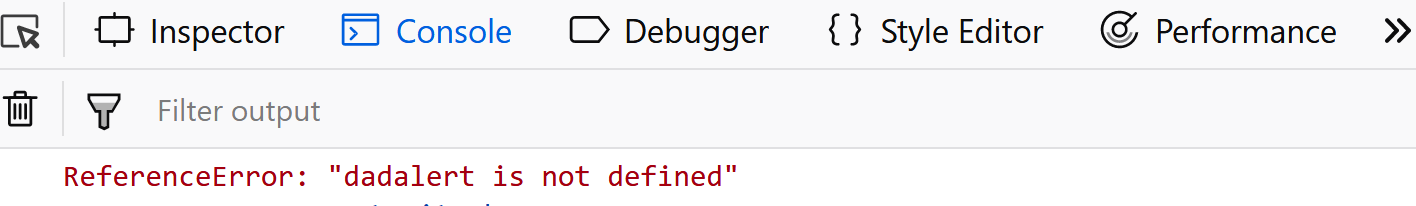

Example: In this example, we will see the usage of try-catch block in javascript.

HTML

<script>

try {

dadalert("Welcome Fellow Geek!");

}

catch(err) {

console.log(err);

}

</script>

Output:

Example: In this example, we will see how a throw statement is used to throw an error in javascript.

HTML

<script>

try {

throw new Error('Yeah... Sorry');

}

catch(e) {

console.log(e);

}

</script>

Output:

try {

Try Block to check for errors.

}

catch(err) {

Catch Block to display errors.

}

finally {

Finally Block executes regardless of the try / catch result.

}

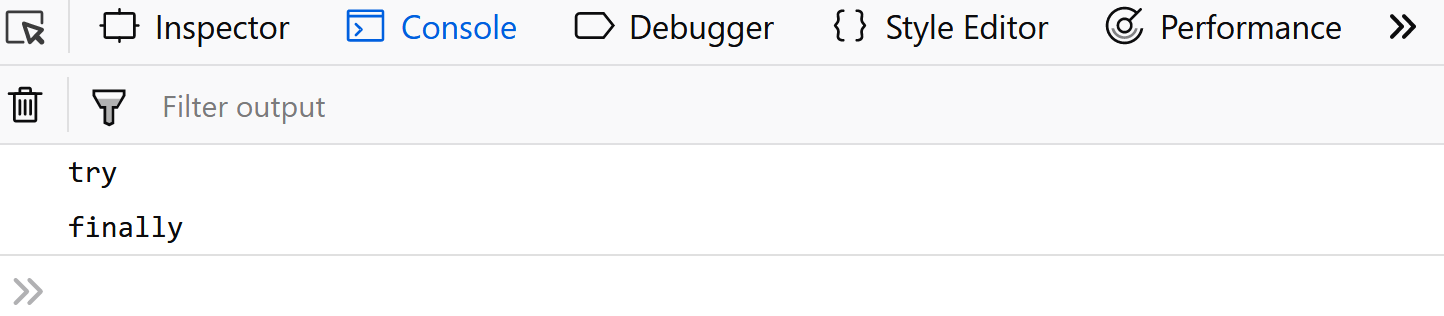

Example: In this example, we will learn about the final statement of Javascript.

HTML

<script>

try {

console.log( 'try' );

} catch (e) {

console.log( 'catch' );

} finally {

console.log( 'finally' );

}

</script>

Output: The Finally Block can also override the message of the catch block so be careful while using it.

Bugs and errors are inevitable in programming. A friend of mine calls them unknown features :).

Call them whatever you want, but I honestly believe that bugs are one of the things that make our work as programmers interesting.

I mean no matter how frustrated you might be trying to debug some code overnight, I am pretty sure you will have a good laugh when you find out that the problem was a simple comma you overlooked, or something like that. Although, an error reported by a client will bring about more of a frown than a smile.

That said, errors can be annoying and a real pain in the behind. That is why in this article, I want to explain something called try / catch in JavaScript.

What is a try/catch block in JavaScript?

A try / catch block is basically used to handle errors in JavaScript. You use this when you don’t want an error in your script to break your code.

While this might look like something you can easily do with an if statement, try/catch gives you a lot of benefits beyond what an if/else statement can do, some of which you will see below.

try{

//...

}catch(e){

//...

}A try statement lets you test a block of code for errors.

A catch statement lets you handle that error. For example:

try{

getData() // getData is not defined

}catch(e){

alert(e)

}This is basically how a try/catch is constructed. You put your code in the try block, and immediately if there is an error, JavaScript gives the catch statement control and it just does whatever you say. In this case, it alerts you to the error.

All JavaScript errors are actually objects that contain two properties: the name (for example, Error, syntaxError, and so on) and the actual error message. That is why when we alert e, we get something like ReferenceError: getData is not defined.

Like every other object in JavaScript, you can decide to access the values differently, for example e.name(ReferenceError) and e.message(getData is not defined).

But honestly this is not really different from what JavaScript will do. Although JavaScript will respect you enough to log the error in the console and not show the alert for the whole world to see :).

What, then, is the benefit of try/catch statements?

How to use try/catch statements

The throw Statement

One of the benefits of try/catch is its ability to display your own custom-created error. This is called (throw error).

In situations where you don’t want this ugly thing that JavaScript displays, you can throw your error (an exception) with the use of the throw statement. This error can be a string, boolean, or object. And if there is an error, the catch statement will display the error you throw.

let num =prompt("insert a number greater than 30 but less than 40")

try {

if(isNaN(num)) throw "Not a number (☉。☉)!"

else if (num>40) throw "Did you even read the instructions ಠ︵ಠ, less than 40"

else if (num <= 30) throw "Greater than 30 (ب_ب)"

}catch(e){

alert(e)

}This is nice, right? But we can take it a step further by actually throwing an error with the JavaScript constructor errors.

Basically JavaScript categorizes errors into six groups:

- EvalError — An error occurred in the eval function.

- RangeError — A number out of range has occurred, for example

1.toPrecision(500).toPrecisionbasically gives numbers a decimal value, for example 1.000, and a number cannot have 500 of that. - ReferenceError — Using a variable that has not been declared

- syntaxError — When evaluating a code with a syntax error

- TypeError — If you use a value that is outside the range of expected types: for example

1.toUpperCase() - URI (Uniform Resource Identifier) Error — A URIError is thrown if you use illegal characters in a URI function.

So with all this, we could easily throw an error like throw new Error("Hi there"). In this case the name of the error will be Error and the message Hi there. You could even go ahead and create your own custom error constructor, for example:

function CustomError(message){

this.value ="customError";

this.message=message;

}And you can easily use this anywhere with throw new CustomError("data is not defined").

So far we have learnt about try/catch and how it prevents our script from dying, but that actually depends. Let’s consider this example:

try{

console.log({{}})

}catch(e){

alert(e.message)

}

console.log("This should run after the logged details")But when you try it out, even with the try statement, it still does not work. This is because there are two main types of errors in JavaScript (what I described above –syntaxError and so on – are not really types of errors. You can call them examples of errors): parse-time errors and runtime errors or exceptions.

Parse-time errors are errors that occur inside the code, basically because the engine does not understand the code.

For example, from above, JavaScript does not understand what you mean by {{}}, and because of that, your try / catch has no use here (it won’t work).

On the other hand, runtime errors are errors that occur in valid code, and these are the errors that try/catch will surely find.

try{

y=x+7

} catch(e){

alert("x is not defined")

}

alert("No need to worry, try catch will handle this to prevent your code from breaking")Believe it or not, the above is valid code and the try /catch will handle the error appropriately.

The Finally statement

The finally statement acts like neutral ground, the base point or the final ground for your try/ catch block. With finally, you are basically saying no matter what happens in the try/catch (error or no error), this code in the finally statement should run. For example:

let data=prompt("name")

try{

if(data==="") throw new Error("data is empty")

else alert(`Hi ${data} how do you do today`)

} catch(e){

alert(e)

} finally {

alert("welcome to the try catch article")

}Nesting try blocks

You can also nest try blocks, but like every other nesting in JavaScript (for example if, for, and so on), it tends to get clumsy and unreadable, so I advise against it. But that is just me.

Nesting try blocks gives you the advantage of using just one catch statement for multiple try statements. Although you could also decide to write a catch statement for each try block, like this:

try {

try {

throw new Error('oops');

} catch(e){

console.log(e)

} finally {

console.log('finally');

}

} catch (ex) {

console.log('outer '+ex);

}In this case, there won’t be any error from the outer try block because nothing is wrong with it. The error comes from the inner try block, and it is already taking care of itself (it has it own catch statement). Consider this below:

try {

try {

throw new Error('inner catch error');

} finally {

console.log('finally');

}

} catch (ex) {

console.log(ex);

}This code above works a little bit differently: the error occurs in the inner try block with no catch statement but instead with a finally statement.

Note that try/catch can be written in three different ways: try...catch, try...finally, try...catch...finally), but the error is throw from this inner try.

The finally statement for this inner try will definitely work, because like we said earlier, it works no matter what happens in try/catch. But even though the outer try does not have an error, control is still given to its catch to log an error. And even better, it uses the error we created in the inner try statement because the error is coming from there.

If we were to create an error for the outer try, it would still display the inner error created, except the inner one catches its own error.

You can play around with the code below by commenting out the inner catch.

try {

try {

throw new Error('inner catch error');

} catch(e){ //comment this catch out

console.log(e)

} finally {

console.log('finally');

}

throw new Error("outer catch error")

} catch (ex) {

console.log(ex);

}The Rethrow Error

The catch statement actually catches all errors that come its way, and sometimes we might not want that. For example,

"use strict"

let x=parseInt(prompt("input a number less than 5"))

try{

y=x-10

if(y>=5) throw new Error(" y is not less than 5")

else alert(y)

}catch(e){

alert(e)

}Let’s assume for a second that the number inputted will be less than 5 (the purpose of «use strict» is to indicate that the code should be executed in «strict mode»). With strict mode, you can not, for example, use undeclared variables (source).

I want the try statement to throw an error of y is not… when the value of y is greater than 5 which is close to impossible. The error above should be for y is not less… and not y is undefined.

In situations like this, you can check for the name of the error, and if it is not what you want, rethrow it:

"use strict"

let x = parseInt(prompt("input a number less than 5"))

try{

y=x-10

if(y>=5) throw new Error(" y is not less than 5")

else alert(y)

}catch(e){

if(e instanceof ReferenceError){

throw e

}else alert(e)

}

This will simply rethrow the error for another try statement to catch or break the script here. This is useful when you want to only monitor a particular type of error and other errors that might occur as a result of negligence should break the code.

Conclusion

In this article, I have tried to explain the following concepts relating to try/catch:

- What try /catch statements are and when they work

- How to throw custom errors

- What the finally statement is and how it works

- How Nesting try / catch statements work

- How to rethrow errors

Thank you for reading. Follow me on twitter @fakoredeDami.

Learn to code for free. freeCodeCamp’s open source curriculum has helped more than 40,000 people get jobs as developers. Get started

Summary: in this tutorial, you’ll learn how to use the JavaScript throw statement to throw an exception.

Introduction to the JavaScript throw statement

The throw statement allows you to throw an exception. Here’s the syntax of the throw statement:

Code language: JavaScript (javascript)

throw expression;

In this syntax, the expression specifies the value of the exception. Typically, you’ll use a new instance of the Error class or its subclasses.

When encountering the throw statement, the JavaScript engine stops executing and passes the control to the first catch block in the call stack. If no catch block exists, the JavaScript engine terminates the script.

Let’s take some examples of using the throw statement.

1) Using the JavaScript throw statement to throw an exception

The following example uses the throw statement to throw an exception in a function:

function add(x, y) { if (typeof x !== 'number') { throw 'The first argument must be a number'; } if (typeof y !== 'number') { throw 'The second argument must be a number'; } return x + y; } const result = add('a', 10); console.log(result);Code language: JavaScript (javascript)

How it works.

First, define the add() function that accepts two arguments and returns the sum of them. The add() function uses the typeof operator to check the type of each argument and throws an exception if the type is not number.

Second, call the add() function and pass a string and a number into it.

Third, show the result to the console.

The script causes an error because the first argument ("a") is not a number:

Uncaught The first argument must be a number

To handle the exception, you can use the try...catch statement. For example:

Code language: JavaScript (javascript)

function add(x, y) { if (typeof x !== 'number') { throw 'The first argument must be a number'; } if (typeof y !== 'number') { throw 'The second argument must be a number'; } return x + y; } try { const result = add('a', 10); console.log(result); } catch (e) { console.log(e); }

Output:

The first argument must be a number

In this example, we place the call to the add() function in a try block. Because the expression in the throw statement is a string, the exception in the catch block is a string as shown in the output.

2) Using JavaScript throw statement to throw an instance of the Error class

In the following example, we throw an instance of the Error class rather than a string in the add() function;

Code language: JavaScript (javascript)

function add(x, y) { if (typeof x !== 'number') { throw new Error('The first argument must be a number'); } if (typeof y !== 'number') { throw new Error('The second argument must be a number'); } return x + y; } try { const result = add('a', 10); console.log(result); } catch (e) { console.log(e.name, ':', e.message); }

Output:

Code language: JavaScript (javascript)

Error : The first argument must be a number

As shown in the output, the exception object in the catch block has the name as Error and the message as the one that we pass to the Error() constructor.

3) Using JavaScript throw statement to throw a user-defined exception

Sometimes, you want to throw a custom error rather than the built-in Error. To do that, you can define a custom error class that extends the Error class and throw a new instance of that class. For example:

First, define the NumberError that extends the Error class:

Code language: JavaScript (javascript)

class NumberError extends Error { constructor(value) { super(`"${value}" is not a valid number`); this.name = 'InvalidNumber'; } }

The constructor() of the NumberError class accepts a value that you’ll pass into it when creating a new instance of the class.

In the constructor() of the NunberError class, we call the constructor of the Error class via the super and pass a string to it. Also, we override the name of the error to the literal string NumberError. If we don’t do this, the name of the NumberError will be Error.

Second, use the NumberError class in the add() function:

Code language: JavaScript (javascript)

function add(x, y) { if (typeof x !== 'number') { throw new NumberError(x); } if (typeof y !== 'number') { throw new NumberError(y); } return x + y; }

In the add() function, we throw an instance of the NumberError class if the argument is not a valid number.

Third, catch the exception thrown by the add() function:

Code language: JavaScript (javascript)

try { const result = add('a', 10); console.log(result); } catch (e) { console.log(e.name, ':', e.message); }

Output:

Code language: JavaScript (javascript)

NumberError : "a" is not a valid number

In this example, the exception name is NumberError and the message is the one that we pass into the super() in the constructor() of the NumberError class.

Summary

- Use the JavaScript

throwstatement to throw a user-define exception.

Was this tutorial helpful ?