@lyschoening It is not ambiguous, that is the purpose of the specification. Consider this scenario:

Given that users with the admin role can create articles

And Mary is an admin user with a valid authentication token

And Mary makes a POST request to /articles

And with the authentication token in the Authorization header

And with a valid JSON formatted request body

The API will return a 200 response code

Then consider this scenario:

Given that users with the editor role cannot create articles

And Bob is an editor and not an admin with a valid authentication token

And Bob makes a POST request to /articles

And with the authentication token in the Authorization header

And with a valid JSON formatted request body

The API will return a 403 response code

In the both scenarios «the server understood the request» because it contained valid parameters and a valid authentication token. However, in the second scenario the server «refuses to authorize it» because the user identified by the token does not have sufficient privileges to create articles.

Also, wouldn’t it be conceivable that someone simply might not wish to give out JWTs to a certain user despite their credentials being correct?

What use would this be unless you’re providing a public, unauthenticated API?

Invalid credentials aren’t necessarily a client error

It depends on the requirements of the request. It is the client’s responsibility to provide an interface to collect the username/password pair to be passed in the body of a request to the authorization endpoint. This endpoint does not require the Authorization header to be supplied in order to get a 200 response. 401 and 403 response codes are tailored to indicate an issue with the presence or value of the Authorization header. Consider this scenario:

Given a user named Janet without an authentication token

And Janet makes a POST request to /articles

And without the Authorization header

And with a valid JSON formatted request body

The API will return a 401 response code

If this scenario happened within the context of your client application, the client would then display an interface to collect the user’s username/password and make a request to the authorization endpoint:

Given a user named Janet without an authentication token

And Janet makes a POST request to /authorize

And with a valid JSON formatted request body containing her username and password

The API will return a 200 response code

And the body will contain a valid authentication token

Now the client application Janet is using can take that token and retry the previous scenario and it would result in a 200 is she had sufficient access privileges or a 403 if she did not.

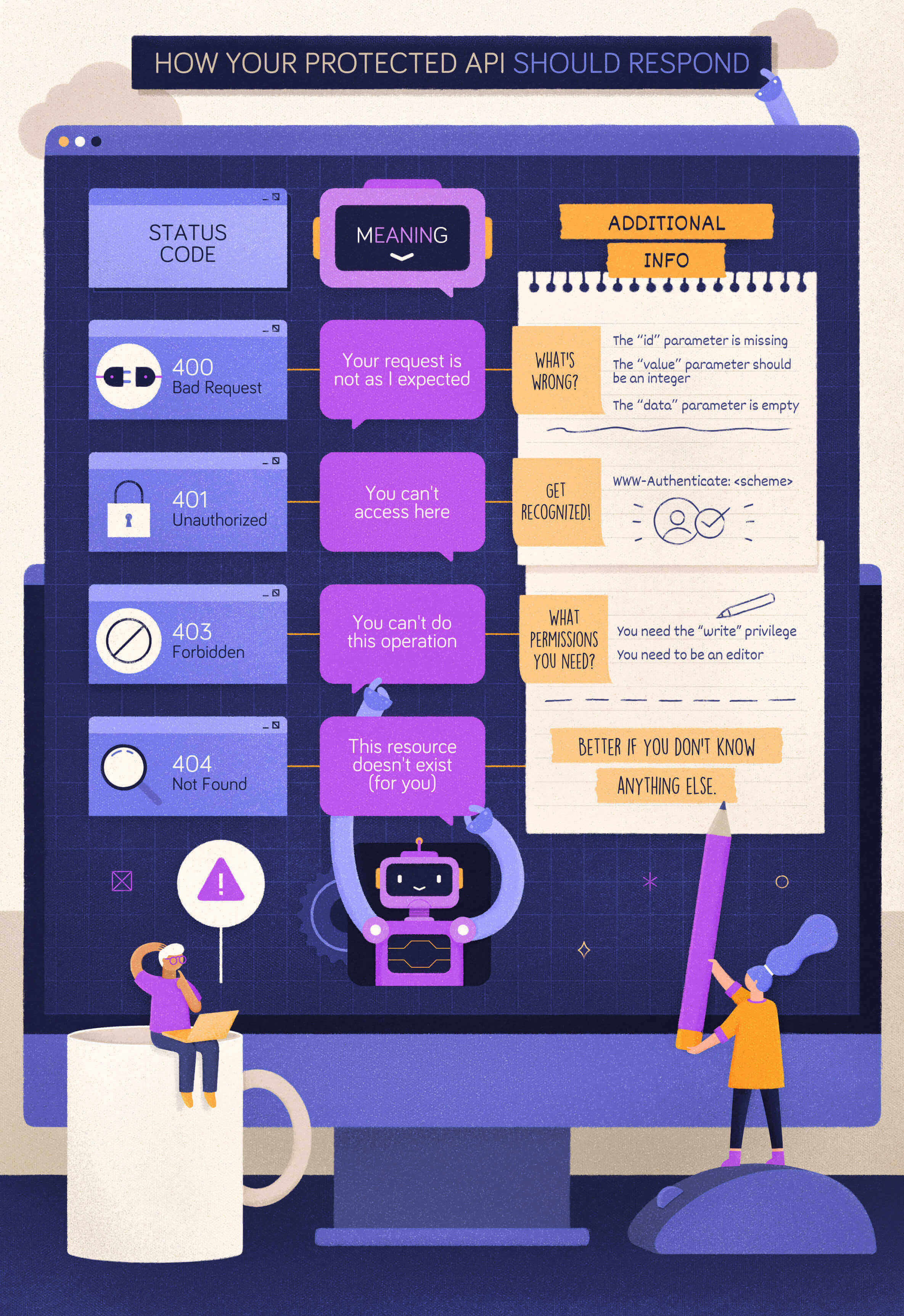

Assume your Web API is protected and a client attempts to access it without the appropriate credentials. How do you deal with this scenario? Most likely, you know you have to return an HTTP status code. But what is the more appropriate one? Should it be 401 Unauthorized or 403 Forbidden? Or maybe something else?

As usual, it depends 🙂. It depends on the specific scenario and also on the security level you want to provide. Let’s go a little deeper.

If you prefer, you can watch a video on the same topic:

Web APIs and HTTP Status Codes

Before going into the specific topic, let’s take a quick look at the rationale of HTTP status codes in general. Most Web APIs are inspired by the REST paradigm. Although the vast majority of them don’t actually implement REST, they usually follow a few RESTful conventions when it comes to HTTP status codes.

The basic principle behind these conventions is that a status code returned in a response must make the client aware of what is going on and what the server expects the client to do next. You can fulfill this principle by giving answers to the following questions:

- Is there a problem or not?

- If there is a problem, on which side is it? On the client or on the server side?

- If there is a problem, what should the client do?

This is a general principle that applies to all the HTTP status codes. For example, if the client receives a 200 OK status code, it knows there was no problem with its request and expects the requested resource representation in the response’s body. If the client receives a 201 Created status code, it knows there was no problem with its request, but the resource representation is not in the response’s body. Similarly, when the client receives a 500 Internal Server Error status code, it knows that this is a problem on the server side, and the client can’t do anything to mitigate it.

In summary, your Web API’s response should provide the client with enough information to realize how it can move forward opportunely.

Let’s consider the case when a client attempts to call a protected API. If the client provides the appropriate credentials (e.g., a valid access token), its request is accepted and processed. What happens when the client has no appropriate credentials? What status code should your API return when a request is not legitimate? What information should it return, and how to guarantee the best security experience?

Fortunately, in the OAuth security context, you have some guidelines. Of course, you can use them even if you don’t use OAuth to secure your API.

«The basic principle behind REST status code conventions is that a status code must make the client aware of what is going on and what the server expects the client to do next»

Tweet This

When to Use 400 Bad Request?

Let’s start with a simple case: a client calls your protected API, omitting a required parameter. In this case, your API should respond with a 400 Bad Request status code. In fact, if that parameter is required, your API can’t even process the client request. The client’s request is malformed.

Your API should return the same status code even when the client provides an unsupported parameter or repeats the same parameter multiple times in its request. In both cases, the client’s request is not as expected and should be refused.

Following the general principle discussed above, the client should be empowered to understand what to do to fix the problem. So, you should add in your response’s body what was wrong with the client’s request. You can provide those details in the format you prefer, such as simple text, XML, JSON, etc. However, using a standard format like the one proposed by the Problem Details for HTTP APIs specifications would be more appropriate to enable uniform problem management across clients.

For example, if your client calls your API with an empty value for the required data parameter, the API could reply with the following response:

HTTP/1.1 400 Bad Request

Content-Type: application/problem+json

Content-Language: en

{

"type": "https://myapi.com/validation-error",

"title": "Validation error",

"detail": "Your request parameters are not valid.",

"invalid-params": [

{

"name": "data",

"reason": "cannot be blank."

}

]

}When to Use 401 Unauthorized?

Now, let’s assume that the client calls your protected API with a well-formed request but no valid credentials. For example, in the OAuth context, this may fall in one of the following cases:

- An access token is missing.

- An access token is expired, revoked, malformed, or invalid for other reasons.

In both cases, the appropriate status code to reply with is 401 Unauthorized. In the spirit of mutual collaboration between the client and the API, the response must include a hint on how to obtain such authorization. That comes in the form of the WWW-Authenticate header with the specific authentication scheme to use. For example, in the case of OAuth2, the response should look like the following:

HTTP/1.1 401 Unauthorized

WWW-Authenticate: Bearer realm="example"You have to use the Bearer scheme and provide the realm parameter to indicate the set of resources the API is protecting.

If the client request does not include any access token, demonstrating that it wasn’t aware that the API is protected, the API’s response should not include any other information.

On the other hand, if the client’s request includes an expired access token, the API response could include the reason for the denied access, as shown in the following example:

HTTP/1.1 401 Unauthorized

WWW-Authenticate: Bearer realm="example",

error="invalid_token",

error_description="The access token expired"When to Use 403 Forbidden?

Let’s explore a different case now. Assume, for example, that your client sends a request to modify a document and provides a valid access token to the API. However, that token doesn’t include or imply any permission or scope that allows the client to perform the desired action.

In this case, your API should respond with a 403 Forbidden status code. With this status code, your API tells the client that the credentials it provided (e.g., the access token) are valid, but it needs appropriate privileges to perform the requested action.

To help the client understand what to do next, your API may include what privileges are needed in its response. For example, according to the OAuth2 guidelines, your API may include information about the missing scope to access the protected resource.

Try out the most powerful authentication platform for free.Get started →

Security Considerations

When you plan how to respond to your client’s requests, always keep security in mind.

How to deal with response details

A primary security concern is to avoid providing useful information to potential attackers. In other words, returning detailed information in the API responses to attempts to access protected resources may be a security risk.

For example, suppose your API returns a 401 Unauthorized status code with an error description like The access token is expired. In this case, it gives information about the token itself to a potential attacker. The same happens when your API responds with a 403 Forbidden status code and reports the missing scope or privilege.

In other words, sharing this information can improve the collaboration between the client and the server, according to the basic principle of the REST paradigm. However, the same information may be used by malicious attackers to elaborate their attack strategy.

Since this additional information is optional for both the HTTP specifications and the OAuth2 bearer token guidelines, maybe you should think carefully about sharing it. The basic principle on sharing that additional information should be based on the answer to this question: how would the client behave any differently if provided with more information?

For example, in the case of a response with a 401 Unauthorized status code, does the client’s behavior change when it knows that its token is expired or revoked? In any case, it must request a new token. So, adding that information doesn’t change the client’s behavior.

Different is the case with 403 Forbidden. By informing your client that it needs a specific permission, your API makes it learn what to do next, i.e., requesting that additional permission. If your API doesn’t provide this additional information, it will behave differently because it doesn’t know what to do to access that resource.

Don’t let the client know…

Now, assume your client attempts to access a resource that it MUST NOT access at all, for example, because it belongs to another user. What status code should your API return? Should it return a 403 or a 401 status code?

You may be tempted to return a 403 status code anyway. But, actually, you can’t suggest any missing permission because that client has no way to access that resource. So, the 403 status code gives no actual helpful information. You may think that returning a 401 status code makes sense in this case. After all, the resource belongs to another user, so the request should come from a different user.

However, since that resource shouldn’t be reached by the current client, the best option is to hide it. Letting the client (and especially the user behind it) know that resource exists could possibly lead to Insecure Direct Object References (IDOR), an access control vulnerability based on the knowledge of resources you shouldn’t access. Therefore, in these cases, your API should respond with a 404 Not Found status code. This is an option provided by the HTTP specification:

An origin server that wishes to «hide» the current existence of a forbidden target resource MAY instead respond with a status code of 404 (Not Found).

For example, this is the strategy adopted by GitHub when you don’t have any permission to access a repository. This approach avoids that an attacker attempts to access the resource again with a slightly different strategy.

How to deal with bad requests

When a client sends a malformed request, you know you should reply with a 400 Bad Request status code. You may be tempted to analyze the request’s correctness before evaluating the client credentials. You shouldn’t do this for a few reasons:

- By evaluating the client credentials before the request’s validity, you avoid your API processing requests that aren’t allowed to be there.

- A potential attacker could figure out how a request should look without being authenticated, even before obtaining or stealing a legitimate access token.

Also, consider that in infrastructures with an API gateway, the client credentials will be evaluated beforehand by the gateway itself, which doesn’t know at all what parameters the API is expecting.

The security measures discussed here must be applied in the production environment. Of course, in the development environment, your API can provide all the information you need to be able to diagnose the causes of an authorization failure.

Recap

Throughout this article, you learned that:

400 Bad Requestis the status code to return when the form of the client request is not as the API expects.401 Unauthorizedis the status code to return when the client provides no credentials or invalid credentials.403 Forbiddenis the status code to return when a client has valid credentials but not enough privileges to perform an action on a resource.

You also learned that some security concerns might arise when your API exposes details that malicious attackers may exploit. In these cases, you may adopt a more restricted strategy by including just the needed details in the response body or even using the 404 Not Found status code instead of 403 Forbidden or 401 Unauthorized.

The following cheat sheet summarizes what you learned:

50

50 people found this article helpful

How to Fix 4xx (Client) and 5xx (Server) HTTP Status Code Errors

Updated on January 18, 2023

HTTP status codes—the 4xx and 5xx varieties—appear when there’s an error loading a web page. These are standard types of errors, so you could see them in any browser, like Edge, Internet Explorer, Firefox, Chrome, Opera, etc.

Microsoft no longer supports Internet Explorer and recommends that you update to the newer Edge browser. Head to their site to download Edge.

Common 4xx and 5xx HTTP Status Codes

Common 4xx and 5xx HTTP status codes are listed below, with helpful tips to help you get past them and on to the web page you were looking for.

| Common HTTP Status Codes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Status Code | Reason Phrase | More Information |

| 400 | Bad Request | The request you sent to the website server (for example, a request to load a web page) was somehow malformed. Since the server couldn’t understand the request, it couldn’t process it and instead gave you the 400 error. |

| 401 | Unauthorized | The page you were trying to access can not be loaded until you first log on with a valid username and password. If you’ve just logged on and received the 401 error, it means that the credentials you entered were invalid. Invalid credentials could mean that you don’t have an account with the website, your username was entered incorrectly, or your password was incorrect. |

| 403 | Forbidden | Accessing the page or resource you were trying to reach is absolutely forbidden. In other words, a 403 error means that you don’t have access to whatever you’re trying to view. |

| 404 | Not Found | The page you were trying to reach could not be found on the website’s server. This is the most popular HTTP status code that you will probably see. The 404 error will often appear as The page cannot be found. |

| 408 | Request Timeout | The request you sent to the website server (like a request to load a web page) timed out. In other words, a 408 error means that connecting to the website took longer than the website’s server was prepared to wait. |

| 500 | Internal Server Error | 500 Internal Server Error is a very general HTTP status code meaning something went wrong on the website’s server, but the server could not be more specific on what the exact problem was. The 500 Internal Server Error message is the most common «server-side» error you’ll see. |

| 502 | Bad Gateway | One server received an invalid response from another server that it was accessing while attempting to load the web page or fill another request by the browser. In other words, the 502 error is an issue between two different servers on the internet that aren’t communicating properly. |

| 503 | Service Unavailable | The website’s server is simply not available at the moment. 503 errors are usually due to a temporary overloading or maintenance of the server. |

| 504 | Gateway Timeout | One server did not receive a timely response from another server that it was accessing while attempting to load the web page or fill another request by the browser. This often means the other server is down or not working properly. |

1xx, 2xx, and 3xx Codes

Codes that begin with 1, 2, and 3 aren’t errors and aren’t usually seen. You can learn more about those here: A Complete List of HTTP Status Lines.

Thanks for letting us know!

Get the Latest Tech News Delivered Every Day

Subscribe