HTTP response status codes indicate whether a specific HTTP request has been successfully completed.

Responses are grouped in five classes:

- Informational responses (

100–199) - Successful responses (

200–299) - Redirection messages (

300–399) - Client error responses (

400–499) - Server error responses (

500–599)

The status codes listed below are defined by RFC 9110.

Note: If you receive a response that is not in this list, it is a non-standard response, possibly custom to the server’s software.

Information responses

100 Continue-

This interim response indicates that the client should continue the request or ignore the response if the request is already finished.

101 Switching Protocols-

This code is sent in response to an

Upgraderequest header from the client and indicates the protocol the server is switching to. 102 Processing(WebDAV)-

This code indicates that the server has received and is processing the request, but no response is available yet.

103 Early Hints-

This status code is primarily intended to be used with the

Linkheader, letting the user agent start preloading resources while the server prepares a response.

Successful responses

200 OK-

The request succeeded. The result meaning of «success» depends on the HTTP method:

GET: The resource has been fetched and transmitted in the message body.HEAD: The representation headers are included in the response without any message body.PUTorPOST: The resource describing the result of the action is transmitted in the message body.TRACE: The message body contains the request message as received by the server.

201 Created-

The request succeeded, and a new resource was created as a result. This is typically the response sent after

POSTrequests, or somePUTrequests. 202 Accepted-

The request has been received but not yet acted upon.

It is noncommittal, since there is no way in HTTP to later send an asynchronous response indicating the outcome of the request.

It is intended for cases where another process or server handles the request, or for batch processing. -

This response code means the returned metadata is not exactly the same as is available from the origin server, but is collected from a local or a third-party copy.

This is mostly used for mirrors or backups of another resource.

Except for that specific case, the200 OKresponse is preferred to this status. 204 No Content-

There is no content to send for this request, but the headers may be useful.

The user agent may update its cached headers for this resource with the new ones. 205 Reset Content-

Tells the user agent to reset the document which sent this request.

206 Partial Content-

This response code is used when the

Rangeheader is sent from the client to request only part of a resource. 207 Multi-Status(WebDAV)-

Conveys information about multiple resources, for situations where multiple status codes might be appropriate.

208 Already Reported(WebDAV)-

Used inside a

<dav:propstat>response element to avoid repeatedly enumerating the internal members of multiple bindings to the same collection. 226 IM Used(HTTP Delta encoding)-

The server has fulfilled a

GETrequest for the resource, and the response is a representation of the result of one or more instance-manipulations applied to the current instance.

Redirection messages

300 Multiple Choices-

The request has more than one possible response. The user agent or user should choose one of them. (There is no standardized way of choosing one of the responses, but HTML links to the possibilities are recommended so the user can pick.)

301 Moved Permanently-

The URL of the requested resource has been changed permanently. The new URL is given in the response.

302 Found-

This response code means that the URI of requested resource has been changed temporarily.

Further changes in the URI might be made in the future. Therefore, this same URI should be used by the client in future requests. 303 See Other-

The server sent this response to direct the client to get the requested resource at another URI with a GET request.

304 Not Modified-

This is used for caching purposes.

It tells the client that the response has not been modified, so the client can continue to use the same cached version of the response. 305 Use Proxy

Deprecated

-

Defined in a previous version of the HTTP specification to indicate that a requested response must be accessed by a proxy.

It has been deprecated due to security concerns regarding in-band configuration of a proxy. 306 unused-

This response code is no longer used; it is just reserved. It was used in a previous version of the HTTP/1.1 specification.

307 Temporary Redirect-

The server sends this response to direct the client to get the requested resource at another URI with same method that was used in the prior request.

This has the same semantics as the302 FoundHTTP response code, with the exception that the user agent must not change the HTTP method used: if aPOSTwas used in the first request, aPOSTmust be used in the second request. 308 Permanent Redirect-

This means that the resource is now permanently located at another URI, specified by the

Location:HTTP Response header.

This has the same semantics as the301 Moved PermanentlyHTTP response code, with the exception that the user agent must not change the HTTP method used: if aPOSTwas used in the first request, aPOSTmust be used in the second request.

Client error responses

400 Bad Request-

The server cannot or will not process the request due to something that is perceived to be a client error (e.g., malformed request syntax, invalid request message framing, or deceptive request routing).

401 Unauthorized-

Although the HTTP standard specifies «unauthorized», semantically this response means «unauthenticated».

That is, the client must authenticate itself to get the requested response. 402 Payment Required

Experimental

-

This response code is reserved for future use.

The initial aim for creating this code was using it for digital payment systems, however this status code is used very rarely and no standard convention exists. 403 Forbidden-

The client does not have access rights to the content; that is, it is unauthorized, so the server is refusing to give the requested resource.

Unlike401 Unauthorized, the client’s identity is known to the server. 404 Not Found-

The server cannot find the requested resource.

In the browser, this means the URL is not recognized.

In an API, this can also mean that the endpoint is valid but the resource itself does not exist.

Servers may also send this response instead of403 Forbiddento hide the existence of a resource from an unauthorized client.

This response code is probably the most well known due to its frequent occurrence on the web. 405 Method Not Allowed-

The request method is known by the server but is not supported by the target resource.

For example, an API may not allow callingDELETEto remove a resource. 406 Not Acceptable-

This response is sent when the web server, after performing server-driven content negotiation, doesn’t find any content that conforms to the criteria given by the user agent.

407 Proxy Authentication Required-

This is similar to

401 Unauthorizedbut authentication is needed to be done by a proxy. 408 Request Timeout-

This response is sent on an idle connection by some servers, even without any previous request by the client.

It means that the server would like to shut down this unused connection.

This response is used much more since some browsers, like Chrome, Firefox 27+, or IE9, use HTTP pre-connection mechanisms to speed up surfing.

Also note that some servers merely shut down the connection without sending this message. 409 Conflict-

This response is sent when a request conflicts with the current state of the server.

410 Gone-

This response is sent when the requested content has been permanently deleted from server, with no forwarding address.

Clients are expected to remove their caches and links to the resource.

The HTTP specification intends this status code to be used for «limited-time, promotional services».

APIs should not feel compelled to indicate resources that have been deleted with this status code. 411 Length Required-

Server rejected the request because the

Content-Lengthheader field is not defined and the server requires it. 412 Precondition Failed-

The client has indicated preconditions in its headers which the server does not meet.

413 Payload Too Large-

Request entity is larger than limits defined by server.

The server might close the connection or return anRetry-Afterheader field. 414 URI Too Long-

The URI requested by the client is longer than the server is willing to interpret.

415 Unsupported Media Type-

The media format of the requested data is not supported by the server, so the server is rejecting the request.

416 Range Not Satisfiable-

The range specified by the

Rangeheader field in the request cannot be fulfilled.

It’s possible that the range is outside the size of the target URI’s data. 417 Expectation Failed-

This response code means the expectation indicated by the

Expectrequest header field cannot be met by the server. 418 I'm a teapot-

The server refuses the attempt to brew coffee with a teapot.

421 Misdirected Request-

The request was directed at a server that is not able to produce a response.

This can be sent by a server that is not configured to produce responses for the combination of scheme and authority that are included in the request URI. 422 Unprocessable Entity(WebDAV)-

The request was well-formed but was unable to be followed due to semantic errors.

423 Locked(WebDAV)-

The resource that is being accessed is locked.

424 Failed Dependency(WebDAV)-

The request failed due to failure of a previous request.

425 Too Early

Experimental

-

Indicates that the server is unwilling to risk processing a request that might be replayed.

426 Upgrade Required-

The server refuses to perform the request using the current protocol but might be willing to do so after the client upgrades to a different protocol.

The server sends anUpgradeheader in a 426 response to indicate the required protocol(s). 428 Precondition Required-

The origin server requires the request to be conditional.

This response is intended to prevent the ‘lost update’ problem, where a clientGETs a resource’s state, modifies it andPUTs it back to the server, when meanwhile a third party has modified the state on the server, leading to a conflict. 429 Too Many Requests-

The user has sent too many requests in a given amount of time («rate limiting»).

-

The server is unwilling to process the request because its header fields are too large.

The request may be resubmitted after reducing the size of the request header fields. 451 Unavailable For Legal Reasons-

The user agent requested a resource that cannot legally be provided, such as a web page censored by a government.

Server error responses

500 Internal Server Error-

The server has encountered a situation it does not know how to handle.

501 Not Implemented-

The request method is not supported by the server and cannot be handled. The only methods that servers are required to support (and therefore that must not return this code) are

GETandHEAD. 502 Bad Gateway-

This error response means that the server, while working as a gateway to get a response needed to handle the request, got an invalid response.

503 Service Unavailable-

The server is not ready to handle the request.

Common causes are a server that is down for maintenance or that is overloaded.

Note that together with this response, a user-friendly page explaining the problem should be sent.

This response should be used for temporary conditions and theRetry-AfterHTTP header should, if possible, contain the estimated time before the recovery of the service.

The webmaster must also take care about the caching-related headers that are sent along with this response, as these temporary condition responses should usually not be cached. 504 Gateway Timeout-

This error response is given when the server is acting as a gateway and cannot get a response in time.

505 HTTP Version Not Supported-

The HTTP version used in the request is not supported by the server.

506 Variant Also Negotiates-

The server has an internal configuration error: the chosen variant resource is configured to engage in transparent content negotiation itself, and is therefore not a proper end point in the negotiation process.

507 Insufficient Storage(WebDAV)-

The method could not be performed on the resource because the server is unable to store the representation needed to successfully complete the request.

508 Loop Detected(WebDAV)-

The server detected an infinite loop while processing the request.

510 Not Extended-

Further extensions to the request are required for the server to fulfill it.

511 Network Authentication Required-

Indicates that the client needs to authenticate to gain network access.

Browser compatibility

BCD tables only load in the browser

See also

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This is a list of Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) response status codes. Status codes are issued by a server in response to a client’s request made to the server. It includes codes from IETF Request for Comments (RFCs), other specifications, and some additional codes used in some common applications of the HTTP. The first digit of the status code specifies one of five standard classes of responses. The optional message phrases shown are typical, but any human-readable alternative may be provided, or none at all.

Unless otherwise stated, the status code is part of the HTTP standard (RFC 9110).

The Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) maintains the official registry of HTTP status codes.[1]

All HTTP response status codes are separated into five classes or categories. The first digit of the status code defines the class of response, while the last two digits do not have any classifying or categorization role. There are five classes defined by the standard:

- 1xx informational response – the request was received, continuing process

- 2xx successful – the request was successfully received, understood, and accepted

- 3xx redirection – further action needs to be taken in order to complete the request

- 4xx client error – the request contains bad syntax or cannot be fulfilled

- 5xx server error – the server failed to fulfil an apparently valid request

1xx informational response

An informational response indicates that the request was received and understood. It is issued on a provisional basis while request processing continues. It alerts the client to wait for a final response. The message consists only of the status line and optional header fields, and is terminated by an empty line. As the HTTP/1.0 standard did not define any 1xx status codes, servers must not[note 1] send a 1xx response to an HTTP/1.0 compliant client except under experimental conditions.

- 100 Continue

- The server has received the request headers and the client should proceed to send the request body (in the case of a request for which a body needs to be sent; for example, a POST request). Sending a large request body to a server after a request has been rejected for inappropriate headers would be inefficient. To have a server check the request’s headers, a client must send

Expect: 100-continueas a header in its initial request and receive a100 Continuestatus code in response before sending the body. If the client receives an error code such as 403 (Forbidden) or 405 (Method Not Allowed) then it should not send the request’s body. The response417 Expectation Failedindicates that the request should be repeated without theExpectheader as it indicates that the server does not support expectations (this is the case, for example, of HTTP/1.0 servers).[2] - 101 Switching Protocols

- The requester has asked the server to switch protocols and the server has agreed to do so.

- 102 Processing (WebDAV; RFC 2518)

- A WebDAV request may contain many sub-requests involving file operations, requiring a long time to complete the request. This code indicates that the server has received and is processing the request, but no response is available yet.[3] This prevents the client from timing out and assuming the request was lost.

- 103 Early Hints (RFC 8297)

- Used to return some response headers before final HTTP message.[4]

2xx success

This class of status codes indicates the action requested by the client was received, understood, and accepted.[1]

- 200 OK

- Standard response for successful HTTP requests. The actual response will depend on the request method used. In a GET request, the response will contain an entity corresponding to the requested resource. In a POST request, the response will contain an entity describing or containing the result of the action.

- 201 Created

- The request has been fulfilled, resulting in the creation of a new resource.[5]

- 202 Accepted

- The request has been accepted for processing, but the processing has not been completed. The request might or might not be eventually acted upon, and may be disallowed when processing occurs.

- 203 Non-Authoritative Information (since HTTP/1.1)

- The server is a transforming proxy (e.g. a Web accelerator) that received a 200 OK from its origin, but is returning a modified version of the origin’s response.[6][7]

- 204 No Content

- The server successfully processed the request, and is not returning any content.

- 205 Reset Content

- The server successfully processed the request, asks that the requester reset its document view, and is not returning any content.

- 206 Partial Content

- The server is delivering only part of the resource (byte serving) due to a range header sent by the client. The range header is used by HTTP clients to enable resuming of interrupted downloads, or split a download into multiple simultaneous streams.

- 207 Multi-Status (WebDAV; RFC 4918)

- The message body that follows is by default an XML message and can contain a number of separate response codes, depending on how many sub-requests were made.[8]

- 208 Already Reported (WebDAV; RFC 5842)

- The members of a DAV binding have already been enumerated in a preceding part of the (multistatus) response, and are not being included again.

- 226 IM Used (RFC 3229)

- The server has fulfilled a request for the resource, and the response is a representation of the result of one or more instance-manipulations applied to the current instance.[9]

3xx redirection

This class of status code indicates the client must take additional action to complete the request. Many of these status codes are used in URL redirection.[1]

A user agent may carry out the additional action with no user interaction only if the method used in the second request is GET or HEAD. A user agent may automatically redirect a request. A user agent should detect and intervene to prevent cyclical redirects.[10]

- 300 Multiple Choices

- Indicates multiple options for the resource from which the client may choose (via agent-driven content negotiation). For example, this code could be used to present multiple video format options, to list files with different filename extensions, or to suggest word-sense disambiguation.

- 301 Moved Permanently

- This and all future requests should be directed to the given URI.

- 302 Found (Previously «Moved temporarily»)

- Tells the client to look at (browse to) another URL. The HTTP/1.0 specification (RFC 1945) required the client to perform a temporary redirect with the same method (the original describing phrase was «Moved Temporarily»),[11] but popular browsers implemented 302 redirects by changing the method to GET. Therefore, HTTP/1.1 added status codes 303 and 307 to distinguish between the two behaviours.[10]

- 303 See Other (since HTTP/1.1)

- The response to the request can be found under another URI using the GET method. When received in response to a POST (or PUT/DELETE), the client should presume that the server has received the data and should issue a new GET request to the given URI.

- 304 Not Modified

- Indicates that the resource has not been modified since the version specified by the request headers If-Modified-Since or If-None-Match. In such case, there is no need to retransmit the resource since the client still has a previously-downloaded copy.

- 305 Use Proxy (since HTTP/1.1)

- The requested resource is available only through a proxy, the address for which is provided in the response. For security reasons, many HTTP clients (such as Mozilla Firefox and Internet Explorer) do not obey this status code.

- 306 Switch Proxy

- No longer used. Originally meant «Subsequent requests should use the specified proxy.»

- 307 Temporary Redirect (since HTTP/1.1)

- In this case, the request should be repeated with another URI; however, future requests should still use the original URI. In contrast to how 302 was historically implemented, the request method is not allowed to be changed when reissuing the original request. For example, a POST request should be repeated using another POST request.

- 308 Permanent Redirect

- This and all future requests should be directed to the given URI. 308 parallel the behaviour of 301, but does not allow the HTTP method to change. So, for example, submitting a form to a permanently redirected resource may continue smoothly.

4xx client errors

This class of status code is intended for situations in which the error seems to have been caused by the client. Except when responding to a HEAD request, the server should include an entity containing an explanation of the error situation, and whether it is a temporary or permanent condition. These status codes are applicable to any request method. User agents should display any included entity to the user.

- 400 Bad Request

- The server cannot or will not process the request due to an apparent client error (e.g., malformed request syntax, size too large, invalid request message framing, or deceptive request routing).

- 401 Unauthorized

- Similar to 403 Forbidden, but specifically for use when authentication is required and has failed or has not yet been provided. The response must include a WWW-Authenticate header field containing a challenge applicable to the requested resource. See Basic access authentication and Digest access authentication. 401 semantically means «unauthorised», the user does not have valid authentication credentials for the target resource.

- Some sites incorrectly issue HTTP 401 when an IP address is banned from the website (usually the website domain) and that specific address is refused permission to access a website.[citation needed]

- 402 Payment Required

- Reserved for future use. The original intention was that this code might be used as part of some form of digital cash or micropayment scheme, as proposed, for example, by GNU Taler,[13] but that has not yet happened, and this code is not widely used. Google Developers API uses this status if a particular developer has exceeded the daily limit on requests.[14] Sipgate uses this code if an account does not have sufficient funds to start a call.[15] Shopify uses this code when the store has not paid their fees and is temporarily disabled.[16] Stripe uses this code for failed payments where parameters were correct, for example blocked fraudulent payments.[17]

- 403 Forbidden

- The request contained valid data and was understood by the server, but the server is refusing action. This may be due to the user not having the necessary permissions for a resource or needing an account of some sort, or attempting a prohibited action (e.g. creating a duplicate record where only one is allowed). This code is also typically used if the request provided authentication by answering the WWW-Authenticate header field challenge, but the server did not accept that authentication. The request should not be repeated.

- 404 Not Found

- The requested resource could not be found but may be available in the future. Subsequent requests by the client are permissible.

- 405 Method Not Allowed

- A request method is not supported for the requested resource; for example, a GET request on a form that requires data to be presented via POST, or a PUT request on a read-only resource.

- 406 Not Acceptable

- The requested resource is capable of generating only content not acceptable according to the Accept headers sent in the request. See Content negotiation.

- 407 Proxy Authentication Required

- The client must first authenticate itself with the proxy.

- 408 Request Timeout

- The server timed out waiting for the request. According to HTTP specifications: «The client did not produce a request within the time that the server was prepared to wait. The client MAY repeat the request without modifications at any later time.»

- 409 Conflict

- Indicates that the request could not be processed because of conflict in the current state of the resource, such as an edit conflict between multiple simultaneous updates.

- 410 Gone

- Indicates that the resource requested was previously in use but is no longer available and will not be available again. This should be used when a resource has been intentionally removed and the resource should be purged. Upon receiving a 410 status code, the client should not request the resource in the future. Clients such as search engines should remove the resource from their indices. Most use cases do not require clients and search engines to purge the resource, and a «404 Not Found» may be used instead.

- 411 Length Required

- The request did not specify the length of its content, which is required by the requested resource.

- 412 Precondition Failed

- The server does not meet one of the preconditions that the requester put on the request header fields.

- 413 Payload Too Large

- The request is larger than the server is willing or able to process. Previously called «Request Entity Too Large» in RFC 2616.[18]

- 414 URI Too Long

- The URI provided was too long for the server to process. Often the result of too much data being encoded as a query-string of a GET request, in which case it should be converted to a POST request. Called «Request-URI Too Long» previously in RFC 2616.[19]

- 415 Unsupported Media Type

- The request entity has a media type which the server or resource does not support. For example, the client uploads an image as image/svg+xml, but the server requires that images use a different format.

- 416 Range Not Satisfiable

- The client has asked for a portion of the file (byte serving), but the server cannot supply that portion. For example, if the client asked for a part of the file that lies beyond the end of the file. Called «Requested Range Not Satisfiable» previously RFC 2616.[20]

- 417 Expectation Failed

- The server cannot meet the requirements of the Expect request-header field.[21]

- 418 I’m a teapot (RFC 2324, RFC 7168)

- This code was defined in 1998 as one of the traditional IETF April Fools’ jokes, in RFC 2324, Hyper Text Coffee Pot Control Protocol, and is not expected to be implemented by actual HTTP servers. The RFC specifies this code should be returned by teapots requested to brew coffee.[22] This HTTP status is used as an Easter egg in some websites, such as Google.com’s «I’m a teapot» easter egg.[23][24][25] Sometimes, this status code is also used as a response to a blocked request, instead of the more appropriate 403 Forbidden.[26][27]

- 421 Misdirected Request

- The request was directed at a server that is not able to produce a response (for example because of connection reuse).

- 422 Unprocessable Entity

- The request was well-formed but was unable to be followed due to semantic errors.[8]

- 423 Locked (WebDAV; RFC 4918)

- The resource that is being accessed is locked.[8]

- 424 Failed Dependency (WebDAV; RFC 4918)

- The request failed because it depended on another request and that request failed (e.g., a PROPPATCH).[8]

- 425 Too Early (RFC 8470)

- Indicates that the server is unwilling to risk processing a request that might be replayed.

- 426 Upgrade Required

- The client should switch to a different protocol such as TLS/1.3, given in the Upgrade header field.

- 428 Precondition Required (RFC 6585)

- The origin server requires the request to be conditional. Intended to prevent the ‘lost update’ problem, where a client GETs a resource’s state, modifies it, and PUTs it back to the server, when meanwhile a third party has modified the state on the server, leading to a conflict.[28]

- 429 Too Many Requests (RFC 6585)

- The user has sent too many requests in a given amount of time. Intended for use with rate-limiting schemes.[28]

- 431 Request Header Fields Too Large (RFC 6585)

- The server is unwilling to process the request because either an individual header field, or all the header fields collectively, are too large.[28]

- 451 Unavailable For Legal Reasons (RFC 7725)

- A server operator has received a legal demand to deny access to a resource or to a set of resources that includes the requested resource.[29] The code 451 was chosen as a reference to the novel Fahrenheit 451 (see the Acknowledgements in the RFC).

5xx server errors

The server failed to fulfil a request.

Response status codes beginning with the digit «5» indicate cases in which the server is aware that it has encountered an error or is otherwise incapable of performing the request. Except when responding to a HEAD request, the server should include an entity containing an explanation of the error situation, and indicate whether it is a temporary or permanent condition. Likewise, user agents should display any included entity to the user. These response codes are applicable to any request method.

- 500 Internal Server Error

- A generic error message, given when an unexpected condition was encountered and no more specific message is suitable.

- 501 Not Implemented

- The server either does not recognize the request method, or it lacks the ability to fulfil the request. Usually this implies future availability (e.g., a new feature of a web-service API).

- 502 Bad Gateway

- The server was acting as a gateway or proxy and received an invalid response from the upstream server.

- 503 Service Unavailable

- The server cannot handle the request (because it is overloaded or down for maintenance). Generally, this is a temporary state.[30]

- 504 Gateway Timeout

- The server was acting as a gateway or proxy and did not receive a timely response from the upstream server.

- 505 HTTP Version Not Supported

- The server does not support the HTTP version used in the request.

- 506 Variant Also Negotiates (RFC 2295)

- Transparent content negotiation for the request results in a circular reference.[31]

- 507 Insufficient Storage (WebDAV; RFC 4918)

- The server is unable to store the representation needed to complete the request.[8]

- 508 Loop Detected (WebDAV; RFC 5842)

- The server detected an infinite loop while processing the request (sent instead of 208 Already Reported).

- 510 Not Extended (RFC 2774)

- Further extensions to the request are required for the server to fulfill it.[32]

- 511 Network Authentication Required (RFC 6585)

- The client needs to authenticate to gain network access. Intended for use by intercepting proxies used to control access to the network (e.g., «captive portals» used to require agreement to Terms of Service before granting full Internet access via a Wi-Fi hotspot).[28]

Unofficial codes

The following codes are not specified by any standard.

- 419 Page Expired (Laravel Framework)

- Used by the Laravel Framework when a CSRF Token is missing or expired.

- 420 Method Failure (Spring Framework)

- A deprecated response used by the Spring Framework when a method has failed.[33]

- 420 Enhance Your Calm (Twitter)

- Returned by version 1 of the Twitter Search and Trends API when the client is being rate limited; versions 1.1 and later use the 429 Too Many Requests response code instead.[34] The phrase «Enhance your calm» comes from the 1993 movie Demolition Man, and its association with this number is likely a reference to cannabis.[citation needed]

- 430 Request Header Fields Too Large (Shopify)

- Used by Shopify, instead of the 429 Too Many Requests response code, when too many URLs are requested within a certain time frame.[35]

- 450 Blocked by Windows Parental Controls (Microsoft)

- The Microsoft extension code indicated when Windows Parental Controls are turned on and are blocking access to the requested webpage.[36]

- 498 Invalid Token (Esri)

- Returned by ArcGIS for Server. Code 498 indicates an expired or otherwise invalid token.[37]

- 499 Token Required (Esri)

- Returned by ArcGIS for Server. Code 499 indicates that a token is required but was not submitted.[37]

- 509 Bandwidth Limit Exceeded (Apache Web Server/cPanel)

- The server has exceeded the bandwidth specified by the server administrator; this is often used by shared hosting providers to limit the bandwidth of customers.[38]

- 529 Site is overloaded

- Used by Qualys in the SSLLabs server testing API to signal that the site can’t process the request.[39]

- 530 Site is frozen

- Used by the Pantheon Systems web platform to indicate a site that has been frozen due to inactivity.[40]

- 598 (Informal convention) Network read timeout error

- Used by some HTTP proxies to signal a network read timeout behind the proxy to a client in front of the proxy.[41]

- 599 Network Connect Timeout Error

- An error used by some HTTP proxies to signal a network connect timeout behind the proxy to a client in front of the proxy.

Internet Information Services

Microsoft’s Internet Information Services (IIS) web server expands the 4xx error space to signal errors with the client’s request.

- 440 Login Time-out

- The client’s session has expired and must log in again.[42]

- 449 Retry With

- The server cannot honour the request because the user has not provided the required information.[43]

- 451 Redirect

- Used in Exchange ActiveSync when either a more efficient server is available or the server cannot access the users’ mailbox.[44] The client is expected to re-run the HTTP AutoDiscover operation to find a more appropriate server.[45]

IIS sometimes uses additional decimal sub-codes for more specific information,[46] however these sub-codes only appear in the response payload and in documentation, not in the place of an actual HTTP status code.

nginx

The nginx web server software expands the 4xx error space to signal issues with the client’s request.[47][48]

- 444 No Response

- Used internally[49] to instruct the server to return no information to the client and close the connection immediately.

- 494 Request header too large

- Client sent too large request or too long header line.

- 495 SSL Certificate Error

- An expansion of the 400 Bad Request response code, used when the client has provided an invalid client certificate.

- 496 SSL Certificate Required

- An expansion of the 400 Bad Request response code, used when a client certificate is required but not provided.

- 497 HTTP Request Sent to HTTPS Port

- An expansion of the 400 Bad Request response code, used when the client has made a HTTP request to a port listening for HTTPS requests.

- 499 Client Closed Request

- Used when the client has closed the request before the server could send a response.

Cloudflare

Cloudflare’s reverse proxy service expands the 5xx series of errors space to signal issues with the origin server.[50]

- 520 Web Server Returned an Unknown Error

- The origin server returned an empty, unknown, or unexpected response to Cloudflare.[51]

- 521 Web Server Is Down

- The origin server refused connections from Cloudflare. Security solutions at the origin may be blocking legitimate connections from certain Cloudflare IP addresses.

- 522 Connection Timed Out

- Cloudflare timed out contacting the origin server.

- 523 Origin Is Unreachable

- Cloudflare could not reach the origin server; for example, if the DNS records for the origin server are incorrect or missing.

- 524 A Timeout Occurred

- Cloudflare was able to complete a TCP connection to the origin server, but did not receive a timely HTTP response.

- 525 SSL Handshake Failed

- Cloudflare could not negotiate a SSL/TLS handshake with the origin server.

- 526 Invalid SSL Certificate

- Cloudflare could not validate the SSL certificate on the origin web server. Also used by Cloud Foundry’s gorouter.

- 527 Railgun Error

- Error 527 indicates an interrupted connection between Cloudflare and the origin server’s Railgun server.[52]

- 530

- Error 530 is returned along with a 1xxx error.[53]

AWS Elastic Load Balancer

Amazon’s Elastic Load Balancing adds a few custom return codes

- 460

- Client closed the connection with the load balancer before the idle timeout period elapsed. Typically when client timeout is sooner than the Elastic Load Balancer’s timeout.[54]

- 463

- The load balancer received an X-Forwarded-For request header with more than 30 IP addresses.[54]

- 561 Unauthorized

- An error around authentication returned by a server registered with a load balancer. You configured a listener rule to authenticate users, but the identity provider (IdP) returned an error code when authenticating the user.[55]

Caching warning codes (obsoleted)

The following caching related warning codes were specified under RFC 7234. Unlike the other status codes above, these were not sent as the response status in the HTTP protocol, but as part of the «Warning» HTTP header.[56][57]

Since this «Warning» header is often neither sent by servers nor acknowledged by clients, this header and its codes were obsoleted by the HTTP Working Group in 2022 with RFC 9111.[58]

- 110 Response is Stale

- The response provided by a cache is stale (the content’s age exceeds a maximum age set by a Cache-Control header or heuristically chosen lifetime).

- 111 Revalidation Failed

- The cache was unable to validate the response, due to an inability to reach the origin server.

- 112 Disconnected Operation

- The cache is intentionally disconnected from the rest of the network.

- 113 Heuristic Expiration

- The cache heuristically chose a freshness lifetime greater than 24 hours and the response’s age is greater than 24 hours.

- 199 Miscellaneous Warning

- Arbitrary, non-specific warning. The warning text may be logged or presented to the user.

- 214 Transformation Applied

- Added by a proxy if it applies any transformation to the representation, such as changing the content encoding, media type or the like.

- 299 Miscellaneous Persistent Warning

- Same as 199, but indicating a persistent warning.

See also

- Custom error pages

- List of FTP server return codes

- List of HTTP header fields

- List of SMTP server return codes

- Common Log Format

Explanatory notes

- ^ Emphasised words and phrases such as must and should represent interpretation guidelines as given by RFC 2119

References

- ^ a b c «Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) Status Code Registry». Iana.org. Archived from the original on December 11, 2011. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ «RFC 9110: HTTP Semantics and Content, Section 10.1.1 «Expect»«.

- ^ Goland, Yaronn; Whitehead, Jim; Faizi, Asad; Carter, Steve R.; Jensen, Del (February 1999). HTTP Extensions for Distributed Authoring – WEBDAV. IETF. doi:10.17487/RFC2518. RFC 2518. Retrieved October 24, 2009.

- ^ Oku, Kazuho (December 2017). An HTTP Status Code for Indicating Hints. IETF. doi:10.17487/RFC8297. RFC 8297. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ Stewart, Mark; djna. «Create request with POST, which response codes 200 or 201 and content». Stack Overflow. Archived from the original on October 11, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ «RFC 9110: HTTP Semantics and Content, Section 15.3.4».

- ^ «RFC 9110: HTTP Semantics and Content, Section 7.7».

- ^ a b c d e Dusseault, Lisa, ed. (June 2007). HTTP Extensions for Web Distributed Authoring and Versioning (WebDAV). IETF. doi:10.17487/RFC4918. RFC 4918. Retrieved October 24, 2009.

- ^ Delta encoding in HTTP. IETF. January 2002. doi:10.17487/RFC3229. RFC 3229. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b «RFC 9110: HTTP Semantics and Content, Section 15.4 «Redirection 3xx»«.

- ^ Berners-Lee, Tim; Fielding, Roy T.; Nielsen, Henrik Frystyk (May 1996). Hypertext Transfer Protocol – HTTP/1.0. IETF. doi:10.17487/RFC1945. RFC 1945. Retrieved October 24, 2009.

- ^ «The GNU Taler tutorial for PHP Web shop developers 0.4.0». docs.taler.net. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- ^ «Google API Standard Error Responses». 2016. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- ^ «Sipgate API Documentation». Archived from the original on July 10, 2018. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- ^ «Shopify Documentation». Archived from the original on July 25, 2018. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- ^ «Stripe API Reference – Errors». stripe.com. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- ^ «RFC2616 on status 413». Tools.ietf.org. Archived from the original on March 7, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ^ «RFC2616 on status 414». Tools.ietf.org. Archived from the original on March 7, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ^ «RFC2616 on status 416». Tools.ietf.org. Archived from the original on March 7, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ^ TheDeadLike. «HTTP/1.1 Status Codes 400 and 417, cannot choose which». serverFault. Archived from the original on October 10, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ Larry Masinter (April 1, 1998). Hyper Text Coffee Pot Control Protocol (HTCPCP/1.0). doi:10.17487/RFC2324. RFC 2324.

Any attempt to brew coffee with a teapot should result in the error code «418 I’m a teapot». The resulting entity body MAY be short and stout.

- ^ I’m a teapot

- ^ Barry Schwartz (August 26, 2014). «New Google Easter Egg For SEO Geeks: Server Status 418, I’m A Teapot». Search Engine Land. Archived from the original on November 15, 2015. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ^ «Google’s Teapot». Retrieved October 23, 2017.[dead link]

- ^ «Enable extra web security on a website». DreamHost. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ «I Went to a Russian Website and All I Got Was This Lousy Teapot». PCMag. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Nottingham, M.; Fielding, R. (April 2012). «RFC 6585 – Additional HTTP Status Codes». Request for Comments. Internet Engineering Task Force. Archived from the original on May 4, 2012. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- ^ Bray, T. (February 2016). «An HTTP Status Code to Report Legal Obstacles». ietf.org. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ alex. «What is the correct HTTP status code to send when a site is down for maintenance?». Stack Overflow. Archived from the original on October 11, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ Holtman, Koen; Mutz, Andrew H. (March 1998). Transparent Content Negotiation in HTTP. IETF. doi:10.17487/RFC2295. RFC 2295. Retrieved October 24, 2009.

- ^ Nielsen, Henrik Frystyk; Leach, Paul; Lawrence, Scott (February 2000). An HTTP Extension Framework. IETF. doi:10.17487/RFC2774. RFC 2774. Retrieved October 24, 2009.

- ^ «Enum HttpStatus». Spring Framework. org.springframework.http. Archived from the original on October 25, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ «Twitter Error Codes & Responses». Twitter. 2014. Archived from the original on September 27, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2014.

- ^ «HTTP Status Codes and SEO: what you need to know». ContentKing. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- ^ «Screenshot of error page». Archived from the original (bmp) on May 11, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ^ a b «Using token-based authentication». ArcGIS Server SOAP SDK. Archived from the original on September 26, 2014. Retrieved September 8, 2014.

- ^ «HTTP Error Codes and Quick Fixes». Docs.cpanel.net. Archived from the original on November 23, 2015. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- ^ «SSL Labs API v3 Documentation». github.com.

- ^ «Platform Considerations | Pantheon Docs». pantheon.io. Archived from the original on January 6, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ^ «HTTP status codes — ascii-code.com». www.ascii-code.com. Archived from the original on January 7, 2017. Retrieved December 23, 2016.

- ^

«Error message when you try to log on to Exchange 2007 by using Outlook Web Access: «440 Login Time-out»«. Microsoft. 2010. Retrieved November 13, 2013. - ^ «2.2.6 449 Retry With Status Code». Microsoft. 2009. Archived from the original on October 5, 2009. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ^ «MS-ASCMD, Section 3.1.5.2.2». Msdn.microsoft.com. Archived from the original on March 26, 2015. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ «Ms-oxdisco». Msdn.microsoft.com. Archived from the original on July 31, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ «The HTTP status codes in IIS 7.0». Microsoft. July 14, 2009. Archived from the original on April 9, 2009. Retrieved April 1, 2009.

- ^ «ngx_http_request.h». nginx 1.9.5 source code. nginx inc. Archived from the original on September 19, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ «ngx_http_special_response.c». nginx 1.9.5 source code. nginx inc. Archived from the original on May 8, 2018. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ «return» directive Archived March 1, 2018, at the Wayback Machine (http_rewrite module) documentation.

- ^ «Troubleshooting: Error Pages». Cloudflare. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ «Error 520: web server returns an unknown error». Cloudflare. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ «527 Error: Railgun Listener to origin error». Cloudflare. Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

- ^ «Error 530». Cloudflare. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ a b «Troubleshoot Your Application Load Balancers – Elastic Load Balancing». docs.aws.amazon.com. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- ^ «Troubleshoot your Application Load Balancers — Elastic Load Balancing». docs.aws.amazon.com. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ «Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP/1.1): Caching». datatracker.ietf.org. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- ^ «Warning — HTTP | MDN». developer.mozilla.org. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

Some text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.5) license.

- ^ «RFC 9111: HTTP Caching, Section 5.5 «Warning»«. June 2022.

External links

- «RFC 9110: HTTP Semantics and Content, Section 15 «Status Codes»«.

- Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) Status Code Registry

Some Background

REST APIs use the Status-Line part of an HTTP response message to inform clients of their request’s overarching result.

RFC 2616 defines the Status-Line syntax as shown below:

Status-Line = HTTP-Version SP Status-Code SP Reason-Phrase CRLF

A great amount of applications are using Restful APIs that are based on the HTTP protocol for connecting their clients. In all the calls, the server and the endpoint at the client both return a call status to the client which can be in the form of:

- The success of API call.

- Failure of API call.

In both the cases, it is necessary to let the client know so that they can proceed to the next step. In the case of a successful API call they can proceed to the next call or whatever their intent was in the first place but in the case of latter they will be forced to modify their call so that the failed call can be recovered.

RestCase

To enable the best user experience for your customer, it is necessary on the part of the developers to make excellent error messages that can help their client to know what they want to do with the information they get. An excellent error message is precise and lets the user know about the nature of the error so that they can figure their way out of it.

A good error message also allows the developers to get their way out of the failed call.

Next step is to know what error messages to integrate into your framework so that the clients on the end point and the developers at the server are constantly made aware of the situation which they are in. in order to do so, the rule of thumb is to keep the error messages to a minimum and only incorporate those error messages which are helpful.

HTTP defines over 40 standard status codes that can be used to convey the results of a client’s request. The status codes are divided into the five categories presented here:

- 1xx: Informational — Communicates transfer protocol-level information

- 2xx: Success -Indicates that the client’s request was accepted successfully.

- 3xx: Redirection — Indicates that the client must take some additional action in order to complete their request.

- 4xx: Client Error — This category of error status codes points the finger at clients.

- 5xx: Server Error — The server takes responsibility for these error status codes.

If you would ask me 5 years ago about HTTP Status codes I would guess that the talk is about web sites, status 404 meaning that some page was not found and etc. But today when someone asks me about HTTP Status codes, it is 99.9% refers to REST API web services development. I have lots of experience in both areas (Website development, REST API web services development) and it is sometimes hard to come to a conclusion about what and how use the errors in REST APIs.

There are some cases where this status code is always returned, even if there was an error that occurred. Some believe that returning status codes other than 200 is not good as the client did reach your REST API and got response.

Proper use of the status codes will help with your REST API management and REST API workflow management.

If for example the user asked for “account” and that account was not found there are 2 options to use for returning an error to the user:

-

Return 200 OK Status and in the body return a json containing explanation that the account was not found.

-

Return 404 not found status.

The first solution opens up a question whether the user should work a bit harder to parse the json received and to see whether that json contains error or not. -

There is also a third solution: Return 400 Error — Client Error. I will explain a bit later why this is my favorite solution.

It is understandable that for the user it is easier to check the status code of 404 without any parsing work to do.

I my opinion this solution is actually miss-use of the HTTP protocol

We did reach the REST API, we did got response from the REST API, what happens if the users misspells the URL of the REST API – he will get the 404 status but that is returned not by the REST API itself.

I think that these solutions should be interesting to explore and to see the benefits of one versus the other.

There is also one more solution that is basically my favorite – this one is a combination of the first two solutions, he is also gives better Restful API services automatic testing support because only several status codes are returned, I will try to explain about it.

Error handling Overview

Error responses should include a common HTTP status code, message for the developer, message for the end-user (when appropriate), internal error code (corresponding to some specific internally determined ID), links where developers can find more info. For example:

‘{ «status» : 400,

«developerMessage» : «Verbose, plain language description of the problem. Provide developers suggestions about how to solve their problems here»,

«userMessage» : «This is a message that can be passed along to end-users, if needed.»,

«errorCode» : «444444»,

«moreInfo» : «http://www.example.gov/developer/path/to/help/for/444444,

http://tests.org/node/444444»,

}’

How to think about errors in a pragmatic way with REST?

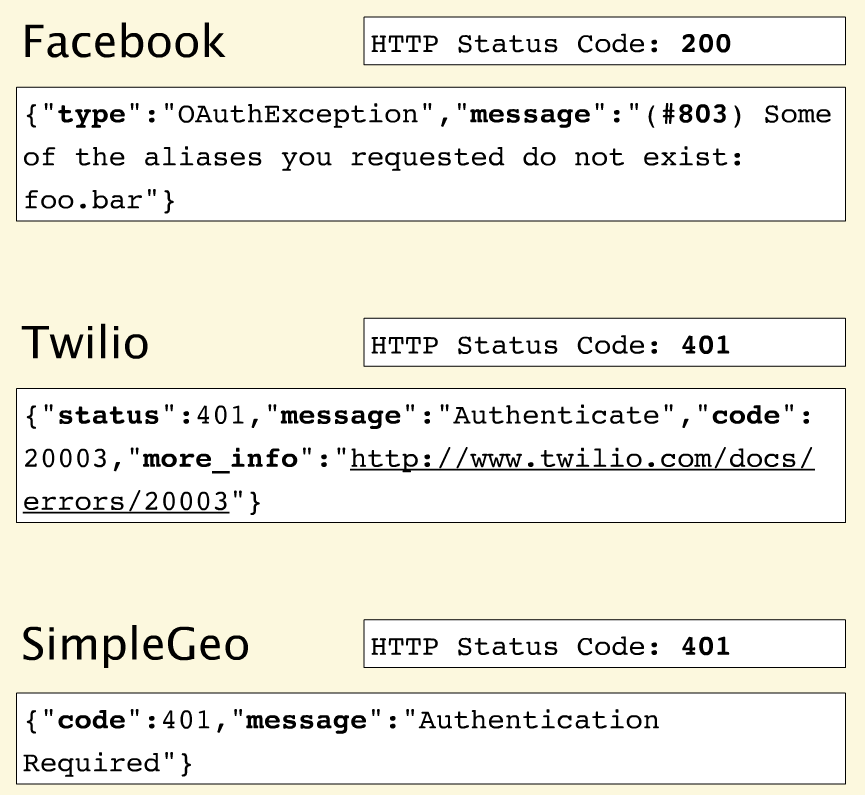

Apigee’s blog post that talks about this issue compares 3 top API providers.

No matter what happens on a Facebook request, you get back the 200 status code — everything is OK. Many error messages also push down into the HTTP response. Here they also throw an #803 error but with no information about what #803 is or how to react to it.

Twilio

Twilio does a great job aligning errors with HTTP status codes. Like Facebook, they provide a more granular error message but with a link that takes you to the documentation. Community commenting and discussion on the documentation helps to build a body of information and adds context for developers experiencing these errors.

SimpleGeo

Provides error codes but with no additional value in the payload.

Error Handling — Best Practises

First of all: Use HTTP status codes! but don’t overuse them.

Use HTTP status codes and try to map them cleanly to relevant standard-based codes.

There are over 70 HTTP status codes. However, most developers don’t have all 70 memorized. So if you choose status codes that are not very common you will force application developers away from building their apps and over to wikipedia to figure out what you’re trying to tell them.

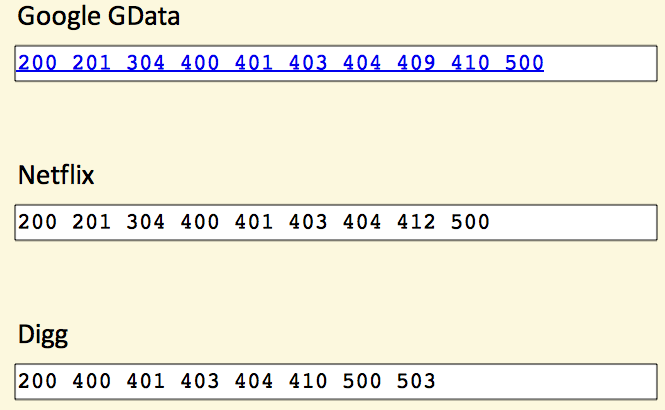

Therefore, most API providers use a small subset.

For example, the Google GData API uses only 10 status codes, Netflix uses 9, and Digg, only 8.

How many status codes should you use for your API?

When you boil it down, there are really only 3 outcomes in the interaction between an app and an API:

- Everything worked

- The application did something wrong

- The API did something wrong

Start by using the following 3 codes. If you need more, add them. But you shouldn’t go beyond 8.

- 200 — OK

- 400 — Bad Request

- 500 — Internal Server Error

Please keep in mind the following rules when using these status codes:

200 (OK) must not be used to communicate errors in the response body

Always make proper use of the HTTP response status codes as specified by the rules in this section. In particular, a REST API must not be compromised in an effort to accommodate less sophisticated HTTP clients.

400 (Bad Request) may be used to indicate nonspecific failure

400 is the generic client-side error status, used when no other 4xx error code is appropriate. For errors in the 4xx category, the response body may contain a document describing the client’s error (unless the request method was HEAD).

500 (Internal Server Error) should be used to indicate API malfunction 500 is the generic REST API error response.

Most web frameworks automatically respond with this response status code whenever they execute some request handler code that raises an exception. A 500 error is never the client’s fault and therefore it is reasonable for the client to retry the exact same request that triggered this response, and hope to get a different response.

If you’re not comfortable reducing all your error conditions to these 3, try adding some more but do not go beyond 8:

- 401 — Unauthorized

- 403 — Forbidden

- 404 — Not Found

Please keep in mind the following rules when using these status codes:

A 401 error response indicates that the client tried to operate on a protected resource without providing the proper authorization. It may have provided the wrong credentials or none at all.

403 (Forbidden) should be used to forbid access regardless of authorization state

A 403 error response indicates that the client’s request is formed correctly, but the REST API refuses to honor it. A 403 response is not a case of insufficient client credentials; that would be 401 (“Unauthorized”). REST APIs use 403 to enforce application-level permissions. For example, a client may be authorized to interact with some, but not all of a REST API’s resources. If the client attempts a resource interaction that is outside of its permitted scope, the REST API should respond with 403.

404 (Not Found) must be used when a client’s URI cannot be mapped to a resource

The 404 error status code indicates that the REST API can’t map the client’s URI to a resource.

RestCase

Conclusion

I believe that the best solution to handle errors in a REST API web services is the third option, in short:

Use three simple, common response codes indicating (1) success, (2) failure due to client-side problem, (3) failure due to server-side problem:

- 200 — OK

- 400 — Bad Request (Client Error) — A json with error more details should return to the client.

- 401 — Unauthorized

- 500 — Internal Server Error — A json with an error should return to the client only when there is no security risk by doing that.

I think that this solution can also ease the client to handle only these 4 status codes and when getting either 400 or 500 code he should take the response message and parse it in order to see what is the problem exactly and on the other hand the REST API service is simple enough.

The decision of choosing which error messages to incorporate and which to leave is based on sheer insight and intuition. For example: if an app and API only has three outcomes which are; everything worked, the application did not work properly and API did not respond properly then you are only concerned with three error codes. By putting in unnecessary codes, you will only distract the users and force them to consult Google, Wikipedia and other websites.

Most important thing in the case of an error code is that it should be descriptive and it should offer two outputs:

- A plain descriptive sentence explaining the situation in the most precise manner.

- An ‘if-then’ situation where the user knows what to do with the error message once it is returned in an API call.

The error message returned in the result of the API call should be very descriptive and verbal. A code is preferred by the client who is well versed in the programming and web language but in the case of most clients they find it hard to get the code.

As I stated before, 404 is a bit problematic status when talking about Restful APIs. Does this status means that the resource was not found? or that there is not mapping to the requested resource? Everyone can decide what to use and where

Error codes are almost the last thing that you want to see in an API response. Generally speaking, it means one of two things — something was so wrong in your request or your handling that the API simply couldn’t parse the passed data, or the API itself has so many problems that even the most well-formed request is going to fail. In either situation, traffic comes crashing to a halt, and the process of discovering the cause and solution begins.

That being said, errors, whether in code form or simple error response, are a bit like getting a shot — unpleasant, but incredibly useful. Error codes are probably the most useful diagnostic element in the API space, and this is surprising, given how little attention we often pay them.

Today, we’re going to talk about exactly why error responses and handling approaches are so useful and important. We’ll take a look at some common error code classifications the average user will encounter, as well as some examples of these codes in action. We’ll also talk a bit about what makes a “good” error code and what makes a “bad” error code, and how to ensure your error codes are up to snuff.

The Value of Error Codes

As we’ve already said, error codes are extremely useful. Error codes in the response stage of an API is the fundamental way in which a developer can communicate failure to a user. This stage, sitting after the initial request stage, is a direct communication between client and API. It’s often the first and most important step towards not only notifying the user of a failure, but jump-starting the error resolution process.

A user doesn’t choose when an error is generated, or what error it gets — error situations often arise in instances that, to the user, are entirely random and suspect. Error responses thus are the only truly constant, consistent communication the user can depend on when an error has occurred. Error codes have an implied value in the way that they both clarify the situation, and communicate the intended functionality.

Consider for instance an error code such as “401 Unauthorized – Please Pass Token.” In such a response, you understand the point of failure, specifically that the user is unauthorized. Additionally, however, you discover the intended functionality — the API requires a token, and that token must be passed as part of the request in order to gain authorization.

With a simple error code and resolution explanation, you’ve not only communicated the cause of the error, but the intended functionality and method to fix said error — that’s incredibly valuable, especially for the amount of data that is actually returned.

HTTP Status Codes

Before we dive deeper into error codes and what makes a “good” code “good,” we need to address the HTTP Status Codes format. These codes are the most common status codes that the average user will encounter, not just in terms of APIs but in terms of general internet usage. While other protocols exist and have their own system of codes, the HTTP Status Codes dominate API communication, and vendor-specific codes are likely to be derived from these ranges.

1XX – Informational

The 1XX range has two basic functionalities. The first is in the transfer of information pertaining to the protocol state of the connected devices — for instance, 101 Switching Protocols is a status code that notes the client has requested a protocol change from the server, and that the request has been approved. The 1XX range also clarifies the state of the initial request. 100 Continue, for instance, notes that a server has received request headers from a client, and that the server is awaiting the request body.

2XX – Success

The 2XX range notes a range of successes in communication, and packages several responses into specific codes. The first three status codes perfectly demonstrate this range – 200 OK means that a GET or POST request was successful, 201 Created confirms that a request has been fulfilled and a new resource has been created for the client, and 202 Accepted means that the request has been accepted, and that processing has begun.

3XX – Redirection

The 3XX range is all about the status of the resource or endpoint. When this type of status code is sent, it means that the server is still accepting communication, but that the point contacted is not the correct point of entry into the system. 301 Moved Permanently verifies that the client request did in fact reach the correct system, but that this request and all future requests should be handled by a different URI. This is very useful in subdomains and when moving a resource from one server to another.

4XX – Client Error

The 4XX series of error codes is perhaps the most famous due to the iconic 404 Not Found status, which is a well-known marker for URLs and URIs that are incorrectly formed. Other more useful status codes for APIs exist in this range, however.

414 URI Too Long is a common status code, denoting that the data pushed through in a GET request is too long, and should be converted to a POST request. Another common code is 429 Too many Requests, which is used for rate limiting to note a client is attempting too many requests at once, and that their traffic is being rejected.

5XX – Server Error

Finally the 5XX range is reserved for error codes specifically related to the server functionality. Whereas the 4XX range is the client’s responsibility (and thus denotes a client failure), the 5XX range specifically notes failures with the server. Error codes like 502 Bad Gateway, which notes the upstream server has failed and that the current server is a gateway, further expose server functionality as a means of showing where failure is occurring. There are less specific, general failures as well, such as 503 Service Unavailable.

Making a Good Error Code

With a solid understanding of HTTP Status Codes, we can start to dissect what actually makes for a good error code, and what makes for a bad error code. Quality error codes not only communicate what went wrong, but why it went wrong.

Overly opaque error codes are extremely unhelpful. Let’s imagine that you are attempting to make a GET request to an API that handles digital music inventory. You’ve submitted your request to an API that you know routinely accepts your traffic, you’ve passed the correct authorization and authentication credentials, and to the best of your knowledge, the server is ready to respond.

You send your data, and receive the following error code – 400 Bad Request. With no additional data, no further information, what does this actually tell you? It’s in the 4XX range, so you know the problem was on the client side, but it does absolutely nothing to communicate the issue itself other than “bad request.”

This is when a “functional” error code is really not as functional as it should be. That same response could easily be made helpful and transparent with minimal effort — but what would this entail? Good error codes must pass three basic criteria in order to truly be helpful. A quality error code should include:

- An HTTP Status Code, so that the source and realm of the problem can be ascertained with ease;

- An Internal Reference ID for documentation-specific notation of errors. In some cases, this can replace the HTTP Status Code, as long as the internal reference sheet includes the HTTP Status Code scheme or similar reference material.

- Human readable messages that summarize the context, cause, and general solution for the error at hand.

Include Standardized Status Codes

First and foremost, every single error code generated should have an attached status code. While this often takes the form of an internal code, it typically takes the form of a standardized status code in the HTTP Status Code scheme. By noting the status using this very specific standardization, you not only communicate the type of error, you communicate where that error has occurred.

There are certain implications for each of the HTTP Status Code ranges, and these implications give a sense as to the responsibility for said error. 5XX errors, for instance, note that the error is generated from the server, and that the fix is necessarily something to do with server-related data, addressing, etc. 4XX, conversely, notes the problem is with the client, and specifically the request from the client or the status of the client at that moment.

By addressing error codes using a default status, you can give a very useful starting point for even basic users to troubleshoot their errors.

Give Context

First and foremost, an error code must give context. In our example above, 400 Bad Request means nothing. Instead, an error code should give further context. One such way of doing this is by passing this information in the body of the response in the language that is common to the request itself.

For instance, our error code of 400 Bad Request can easily have a JSON body that gives far more useful information to the client:

< HTTP/1.1 400 Bad Request

< Date: Wed, 31 May 2017 19:01:41 GMT

< Server: Apache/2.4.25 (Ubuntu)

< Connection: close

< Transfer-Encoding: chunked

< Content-Type: application/json

{ "error" : "REQUEST - BR0x0071" }

This error code is good, but not great. What does it get right? Well, it supplies context, for starters. Being able to see what the specific type of failure is shows where the user can begin the problem solving process. Additionally, and vitally, it also gives an internal reference ID in the form of “BR0x0071”, which can be internally referenced.

While this is an ok error code, it only meets a fraction of our requirements.

Human Readability

Part of what makes error codes like the one we just created so powerful is that it’s usable by humans and machines alike. Unfortunately, this is a very easy thing to mess up — error codes are typically handled by machines, and so it’s very tempting to simply code for the application rather than for the user of said application.

In our newly formed example, we have a very clear error to handle, but we have an additional issue. While we’ve added context, that context is in the form of machine-readable reference code to an internal error note. The user would have to find the documentation, look up the request code “BRx0071”, and then figure out what went wrong.

We’ve fallen into that trap of coding for the machine. While our code is succinct and is serviceable insomuch as it provides context, it does so at the cost of human readability. With a few tweaks, we could improve the code, while still providing the reference number as we did before:

< HTTP/1.1 400 Bad Request

< Date: Wed, 31 May 2017 19:01:41 GMT

< Server: Apache/2.4.25 (Ubuntu)

< Connection: close

< Transfer-Encoding: chunked

< Content-Type: application/json

{ "error" : "Bad Request - Your request is missing parameters. Please verify and resubmit. Issue Reference Number BR0x0071" }

With such a response, not only do you get the status code, you also get useful, actionable information. In this case, it tells the user the issue lies within their parameters. This at least offers a place to start troubleshooting, and is far more useful than saying “there’s a problem.”

While you still want to provide the issue reference number, especially if you intend on integrating an issue tracker into your development cycle, the actual error itself is much more powerful, and much more effective than simply shooting a bunch of data at the application user and hoping something sticks.

Good Error Examples

Let’s take a look at some awesome error code implementations on some popular systems.

Twitter API is a great example of descriptive error reporting codes. Let’s attempt to send a GET request to retrieve our mentions timeline.

https://api.twitter.com/1.1/statuses/mentions_timeline.jsonWhen this is sent to the Twitter API, we receive the following response:

HTTP/1.1 400 Bad Request

x-connection-hash:

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

set-cookie:

guest_id=xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Date:

Thu, 01 Jun 2017 03:04:23 GMT

Content-Length:

62

x-response-time:

5

strict-transport-security:

max-age=631138519

Connection:

keep-alive

Content-Type:

application/json; charset=utf-8

Server:

tsa_b

{"errors":[{"code":215,"message":"Bad Authentication data."}]}

Looking at this data, we can generally figure out what our issue is. First, we’re told that we’ve submitted a 400 Bad Request. This tells us that the problem is somewhere in our request. Our content length is acceptable, and our response time is well within normal limits. We can see, however, that we’re receiving a unique error code that Twitter itself has denoted — “215”, with an attached message that states “Bad Authentication data”.

This error code supplies both valuable information as to why the error has occurred, and also how to rectify it. Our error lies in the fact that we did not pass any authentication data whatsoever — accordingly, error 215 is referenced, which tells us the fix is to supply said authentication data, but also gives us a number to reference on the internal documentation of the Twitter API.

For another great example, let’s look at another social network. Facebook’s Graph API allows us to do quite a lot as long as we have the proper authentication data. For the purposes of this article, all personal information will be blanked out for security purposes.

First, let’s pass a GET request to ascertain some details about a user:

https://graph.facebook.com/v2.9/me?fields=id%2Cname%2Cpicture%2C%20picture&access_token=xxxxxxxxxxxThis request should give us a few basic fields from this user’s Facebook profile, including id, name, and picture. Instead, we get this error response:

{

"error": {

"message": "Syntax error "Field picture specified more than once. This is only possible before version 2.1" at character 23: id,name,picture,picture",

"type": "OAuthException",

"code": 2500,

"fbtrace_id": "xxxxxxxxxxx"

}

}

While Facebook doesn’t directly pass the HTTP error code in the body, it does pass a lot of useful information. The “message” area notes that we’ve run into a syntax error, specifically that we’ve defined the “picture” field more than once. Additionally, this field lets us know that this behavior was possible in previous versions, which is a very useful tool to communicate to users a change in behavior from previous versions to the current.

Additionally, we are provided both a code and an fbtrace_id that can be used with support to identify specific issues in more complex cases. We’ve also received a specific error type, in this case OAuthException, which can be used to narrow down the specifics of the case even further.

Bing

To show a complex failure response code, let’s send a poorly formed (essentially null) GET request to Bing.

HTTP/1.1 200

Date:

Thu, 01 Jun 2017 03:40:55 GMT

Content-Length:

276

Connection:

keep-alive

Content-Type:

application/json; charset=utf-8

Server:

Microsoft-IIS/10.0

X-Content-Type-Options:

nosniff

{"SearchResponse":{"Version":"2.2","Query":{"SearchTerms":"api error codes"},"Errors":[{"Code":1001,"Message":"Required parameter is missing.","Parameter":"SearchRequest.AppId","HelpUrl":"httpu003au002fu002fmsdn.microsoft.comu002fen-usu002flibraryu002fdd251042.aspx"}]}}

This is a very good error code, perhaps the best of the three we’ve demonstrated here. While we have the error code in the form of “1001”, we also have a message stating that a parameter is missing. This parameter is then specifically noted as “SearchRequestAppId”, and a “HelpUrl” variable is passed as a link to a solution.

In this case, we’ve got the best of all worlds. We have a machine readable error code, a human readable summary, and a direct explanation of both the error itself and where to find more information about the error.

Spotify

Though 5XX errors are somewhat rare in modern production environments, we do have some examples in bug reporting systems. One such report noted a 5XX error generated from the following call:

GET /v1/me/player/currently-playingThis resulted in the following error:

[2017-05-02 13:32:14] production.ERROR: GuzzleHttpExceptionServerException: Server error: `GET https://api.spotify.com/v1/me/player/currently-playing` resulted in a `502 Bad Gateway` response:

{

"error" : {

"status" : 502,

"message" : "Bad gateway."

}

}So what makes this a good error code? While the 502 Bad gateway error seems opaque, the additional data in the header response is where our value is derived. By noting the error occurring in production and its addressed variable, we get a general sense that the issue at hand is one of the server gateway handling an exception rather than anything external to the server. In other words, we know the request entered the system, but was rejected for an internal issue at that specific exception address.

When addressing this issue, it was noted that 502 errors are not abnormal, suggesting this to be an issue with server load or gateway timeouts. In such a case, it’s almost impossible to note granularly all of the possible variables — given that situation, this error code is about the best you could possibly ask for.

Conclusion

Much of an error code structure is stylistic. How you reference links, what error code you generate, and how to display those codes is subject to change from company to company. However, there has been headway to standardize these approaches; the IETF recently published RFC 7807, which outlines how to use a JSON object as way to model problem details within HTTP response. The idea is that by providing more specific machine-readable messages with an error response, the API clients can react to errors more effectively.

In general, the goal with error responses is to create a source of information to not only inform the user of a problem, but of the solution to that problem as well. Simply stating a problem does nothing to fix it – and the same is true of API failures.

The balance then is one of usability and brevity. Being able to fully describe the issue at hand and present a usable solution needs to be balanced with ease of readability and parsability. When that perfect balance is struck, something truly powerful happens.