From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

« » Sonnet 116 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

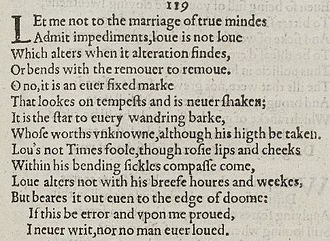

Sonnet 116 in the 1609 Quarto (where it is mis-numbered as 119) |

||||||

|

William Shakespeare’s sonnet 116 was first published in 1609. Its structure and form are a typical example of the Shakespearean sonnet.

The poet begins by stating he does not object to the «marriage of true minds», but maintains that love is not true if it changes with time; true love should be constant, regardless of difficulties. In the seventh line, the poet makes a nautical reference, alluding to love being much like the north star is to sailors. True love is, like the polar star, «ever-fixed». Love is «not Time’s fool», though physical beauty is altered by it.

The movement of 116, like its tone, is careful, controlled, laborious…it defines and redefines its subject in each quatrain, and this subject becomes increasingly vulnerable.[2]

It starts out as motionless and distant, remote, independent; then it moves to be «less remote, more tangible and earthbound»;[2] the final couplet brings a sense of «coming back down to earth». Ideal love is maintained as unchanging throughout the sonnet, and Shakespeare concludes in the final couplet that he is either correct in his estimation of love, or else that no man has ever truly loved.

Structure[edit]

Sonnet 116 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet has three quatrains, followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the typical rhyme scheme of the form abab cdcd efef gg and is composed in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The 10th line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / Within his bending sickle's compass come; (116.10)

This sonnet contains examples of all three metrical variations typically found in literary iambic pentameter of the period. Lines 6 and 8 feature a final extrametrical syllable or feminine ending:

× / × / × / × / × /(×) That looks on tempests and is never shaken; (116.6)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus. (×) = extrametrical syllable.

Line 2 exhibits a mid-line reversal:

× / × / × / / × × / Admit impediments. Love is not love (116.2)

A mid-line reversal can also be found in line 12, while lines 7, 9, and 11 all have potential initial reversals. Finally, line 11 also features a rightward movement of the third ictus (resulting in a four-position figure, × × / /, sometimes referred to as a minor ionic):

/ × × / × × / / × / Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks, (116.11)

The meter demands that line 12’s «even» function as one syllable.[3]

Analysis[edit]

Overview[edit]

Sonnet 116 is one of Shakespeare’s most famous love sonnets, but some scholars have argued the theme has been misunderstood. Hilton Landry believes the appreciation of 116 as a celebration of true love is mistaken,[4] in part because its context in the sequence of adjacent sonnets is not properly considered. Landry acknowledges the sonnet «has the grandeur of generality or a ‘universal significance’,» but cautions that «however timeless and universal its implications may be, we must never forget that Sonnet 116 has a restricted or particular range of meaning simply because it does not stand alone.»[5] Carol Thomas Neely writes that, «Sonnet 116 is part of a sequence which is separate from all the other sonnets of Shakespeare because of their sense of detachment. They aren’t about the action of love and the object of that love is removed in this sequence which consists of Sonnets 94, 116, and 129».[6] This group of three sonnets does not fit the mold of the rest of Shakespeare’s sonnets, therefore, and they defy the typical concept and give a different perspective of what love is and how it is portrayed or experienced. «Though 116 resolves no issues, the poet in this part of the sequence acknowledges and accepts the fallibility of his love more fully than he could acknowledge that of the young man’s earlier».[7]

Other critics of Sonnet 116[8] have argued that one cannot rely on the context of the sonnet to understand its tone. They argue that since «there is no indisputably authoritative sequence to them, we cannot make use of context as positive evidence for one kind of tone or another.»[9] Shakespeare does not attempt to come to any significant conclusion within this particular sonnet because no resolution is needed.

Quatrain 1[edit]

The sonnet begins without the poet’s apparent acknowledgment of the compelling quality of the emotional union of «true minds». As Helen Vendler has observed, «This famous almost ‘impersonal’ sonnet on the marriage of true minds has usually been read as a definition of true love.»[10] This is not a unique theme of Shakespeare’s sonnets. Carol Neely observes that «Like [sonnet] 94, it defines and redefines its subject in each quatrain and this subject becomes increasingly concrete, attractive and vulnerable.»[2] Shakespeare tends to use negation to define love according to Lukas Erne, «The first and the third [quatrains], it is true, define love negatively: ‘love is not…’; Love’s not…’. The two quatrains are further tied together by the reappearance of the verbs ‘to bend’ and ‘to alter’.»[11] Love is defined in vague terms in the first quatrain.

«The stress on the dialectical definition of what love is not accentuates the dogmatic character of this sonnet with which Shakespeare suggests in verse to his interlocutors what true love is: true love is like a marriage sealed before a higher entity (God or His creation), which testifies to its duration, intensity, stability and resistance. A Love of this type watches over the unstable and peregrine life of men at the mercy of their inner dismay and the real world’s tempests» (E. Passannanti).

Garry Murphy observes that the meaning shifts with the distribution of emphasis. He suggests that in the first line the stress should properly be on «me»: «Let ME not to the marriage of true minds…»; the sonnet then becomes «not just a gentle metaphoric definition but an agitated protest born out of fear of loss and merely conveyed by the means of definition.»[9] C.R. B. Combellack disputes the emphasis placed on the «ME» due to the «absence from the sonnet of another person to stand in contrast. No one else is addressed, described, named, or mentioned.»[12] Murphy also claims that «The unstopped first and second lines suggest urgency in speech, not leisurely meditation.»[9] He writes that the short words when delivered would have the effect of «rapid delivery» rather than «slow rumination». Combellack questions this analysis by asking whether «urgency is not more likely to be expressed in short bursts of speech?» He argues that the words in the sonnet are not intended to be read quickly and that this is simply Murphy’s subjective opinion of the quatrain. Murphy believes the best support of the «sonnet itself being an exclamation» comes from the «O no» which he writes a person would not say without some agitation. Combellack responds that «O no» could be used rather calmly in a statement such as «O no, thank you, but my coffee limit is two cups.»[12] If anything, Combellack suggests, the use of the «O» softens the statement and it would require the use of different grammar to suggest that the sonnet should be understood as rapid speech. (depending on the situation)

The poetic language leaves the sort of love described somewhat indeterminate; «The ‘marriage of true minds’ like the ‘power to hurt’ is troublesomely vague open to a variety of interpretations.»[2] Interpretations include the potential for religious imagery and the love being for God, «Lines one and two echo the Anglican marriage service from the Book of Common Prayer.» The concept of the marriage of true minds is thought to be a highly Christian; according to Erne, «The mental picture thus called up in our minds of the bride and bridegroom standing up front in a church is even reinforced by the insistence on the word alter/altar in the following line.»[11]

In simpler words, according to Nithya The first quatrain defines what love is not. The poet asserts that there should be no obstacles for the union of lovers who are really sincere in their love. He makes it very clear that love which changes according to the force of circumstances is not love at all.

Quatrain 2[edit]

The second quatrain explains how love is unchanging according to Nithya, «Love is a star, remote, immovable, self-contained, and perhaps, like the ‘lords and owners of their faces,’ improbably and even somewhat unpleasantly cold and distant.»[2] The second quatrain continues Shakespeare’s attempt to define love, but in a more direct way. Shakespeare mentions «it» in the second quatrain according to Douglas Trevor, «The constancy of love in sonnet 116, the «it» of line five of the poem, is also – for the poet – the poetry, the object of love itself.»[13] Not only is there a direct address to love itself, the style Shakespeare’s contemplation becomes more direct. Erne states, «Lines five to eight stand in contrast to their adjacent quatrains, and they have their special importance by saying what love is rather than what it is not.» This represents a change in Shakespeare’s view that love is completely undefinable. This concept of unchanging love is focused in the statement, «‘[love] is an ever-fixed mark’. This has generally been understood as a sea mark or a beacon.»[11] The image of an ever-fixed mark is elusive, though, and can suggest also a «symbol» whose meaning is well established in the esoteric tradition and Christian iconography. The symbol is in fact an ever-fixed mark that is unbent by climatic changes such as a transient tempest. The ever-fixed mark, from the point of view of this kind of theological reading, cannot symbolize a beacon given that a beacon is subject to erosion and is therefore not eternal. The image of the tempest is allegorically a circumstance and condition, and represents the human life struggling before the fixity of the symbol.(E. Passannanti, 2000) During the Reformation there was dispute about Catholic doctrines, «One of the points of disagreement was precisely that the Reformers rejected the existence of an ever-fixed, or in theological idiom, ‘idelible’ mark which three of the sacraments, according to Catholic teaching, imprint on the soul.»[11] This interpretation makes God the focus of the sonnet as opposed to the typical concept of love.

The compass is also considered an important symbol in the first part of the poem. John Doebler identifies a compass as a symbol that drives the poem, «The first quatrain of this sonnet makes implied use of the compass emblem, a commonplace symbol for constancy during the period in which Shakespeare’s sonnets were composed.»[14] Doebler identifies certain images in the poem with a compass, «In the Renaissance the compass is usually associated with the making of a circle, the ancient symbol of eternity, but in sonnet 116 the emphasis is more upon the contrasting symbolism of the legs of the compass.»[14] The two feet of the compass represent the differences between permanent aspects of love and temporary ones. These differences are explained as, «The physical lovers are caught in a changing world of time, but they are stabilized by spiritual love, which exists in a constant world of eternal ideals.»[14] The sonnet uses imagery like this to create a clearer concept of love in the speaker’s mind.

In simpler words, according to Nithya,The second quatrain elaborates the nature of true love. True love is like a fixed beacon that is not shaken ever by storms. It is the Pole Star that guides every voyaging ship. Its true value is unknown although its altitude is known.

Quatrain 3[edit]

In the third quatrain, «The remover who bends turns out to be the grim reaper, Time, with his bending sickle. What alters are Time’s brief hours and weeks…» and «Only the Day of Judgment (invoked from the sacramental liturgy of marriage) is the proper measure of love’s time».[15] The young man holds the value of beauty over that of love. When he comes to face the fact that the love he felt has changed and become less intense and, in fact, less felt, he changes his mind about this person he’d loved before because what he had felt in his heart wasn’t true. That the object of his affection’s beauty fell to «Time’s Sickle» would not make his feelings change. This fact is supported by Helen Vendler as she wrote, «The second refutational passage, in the third quatrain, proposes indirectly a valuable alternative law, one approved by the poet-speaker, which we may label «the law of inverse constancy»: the more inconstant are time’s alterations (one an hour, one a week), the more constant is love’s endurance, even to the edge of doom».[16] Vendler believes that if the love the young man felt was real it would still be there after the beauty of that love’s object had long faded away, but he «has announced the waning of his own attachment to the speaker, dissolving the «marriage of true minds»»[17] Shakespeare is arguing that if love is true it will stand against all tests of time and adversity, no manner of insignificant details such as the person’s beauty fading could alter or dissolve «the marriage of true minds».

In simpler words, according to Nithya, The third quatrain praises the permanence of spiritual love. Carnal love can die eventually as time harms the physical beauty of the lovers and destroys their charm and loveliness. But, true love remains unaffected by age or youth. Love is not time’s fool because it lasts till the end of one’s life, or even till Doomsday or the day of Judgement.

Couplet[edit]

The couplet of Sonnet 116 Shakespeare went about explaining in the inverse. He says the opposite of what it would be natural to say about love. For instance, instead of writing something to the effect of ‘I have written and men have loved’, according to Nelson, Shakespeare chose to write, «I never writ, nor no man ever loved.» Nelson argues that «The existence of the poem itself gives good evidence that the poet has written. It is harder to see, however, how the mere existence of the poem could show that men have loved. In part, whether men have loved depends upon just what love is…Since the poem is concerned with the nature of love, there is a sense in which what the poem says about love, if true, in part determines whether or not men have loved.»[18] Nelson quotes Ingram and Redpath who are in agreement with his statement when they paraphrase the couplet in an extended form: «If this is a judgment (or a heresy), and this can be proved against me, and by citing my own case in evidence, then I’ve never written anything, and no man’s love has ever been real love.»»[18] Vendler states «Therefore, if he himself is in error on the subject of what true love is, then no man has ever loved; certainly the young man (it is implied) has not loved, if he has not loved after the steady fashion urged by the speaker, without alteration, removals, or impediments».[19]

By restating his authority as poet and moral watch almost in a sacramental manner on the theme of love, by the use of a paradox, Shakespeare rejects that he may be wrong in stating that true love is immortal: the fact that he has indeed written a lot to the point of having reached sonnet 116 on the theme of love and acquired fame for that is self evident that the opposite cannot be true, that is: what he says cannot be an error (E. Passannanti). Men too have indeed loved as love is ingrained in poetry and only lyric poets can testify of men’s faculty of experiencing true love (E. Passannanti).

Each of these critics agree in the essence of the Sonnet and its portrayal of what love really is and what it can withstand, for example, the test of time and the fading of physical attraction of the object of our love. The couplet is, therefore, that men have indeed loved both in true and honest affection (this being the most important part of the argument) as well as falsely in the illusions of beauty before just as Shakespeare has written before this sonnet.

According to Nithya, The couplet consisting of the last two lines ends with the assertion of the poet that if his belief is proved to be wrong, he will never write and that no person has ever loved truly.

Notes and references[edit]

- ^ Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- ^ a b c d e Neely 1977.

- ^ Booth 2000, p. 386.

- ^ Landry 1967.

- ^ Landry 1967, p. 98.

- ^ Neely 1977, p. 83.

- ^ Neely 1977, p. 89.

- ^ Murphy 1982.

- ^ a b c Murphy 1982, p. 40.

- ^ Vendler 1997.

- ^ a b c d Erne 2000.

- ^ a b Combellack 1982, p. 13.

- ^ Trevor 2007.

- ^ a b c Doebler 1964.

- ^ Vendler 1997, p. 490.

- ^ Vendler 1997, p. 492.

- ^ Vendler 1997, p. 493.

- ^ a b Nelson & Cling 2000.

- ^ Vendler 1997, p. 491.

Sources[edit]

- Combellack, C.R.B. (1982). «Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116». The Explicator. 41 (1): 12–14. doi:10.1080/00144940.1982.11483617. ISSN 1939-926X.

- Doebler, John (1964). «A Submerged Emblem in Sonnet 116». Shakespeare Quarterly. Folger Shakespeare Library. 15 (1): 109–110. doi:10.2307/2867968. ISSN 1538-3555. JSTOR 2867968.

- Erne, Lukas (2000). «Shakespeare’s ‘Ever-Fixed Mark’: Theological Implications in Sonnet 116». English Studies. Routledge. 81 (4): 293–304. doi:10.1076/0013-838X(200007)81:4;1-F;FT293. ISSN 1744-4217. S2CID 162250320.

- Landry, Hilton (1967). «The Marriage of True Minds: Truth and Error in Sonnet 116». Shakespeare Studies. University of Cincinnati. 3: 98–110.

- Murphy, Garry (1982). «Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116». The Explicator. 39 (1): 39–41. doi:10.1080/00144940.1980.11483423. ISSN 1939-926X.

- Neely, Carol Thomas (1977). «Detachment and Engagement in Shakespeare’s Sonnets: 94, 116, and 129». PMLA. Modern Language Association. 92 (1): 83–95. doi:10.2307/461416. ISSN 0030-8129. JSTOR 461416. S2CID 163308405.

- Nelson, Jeffrey N.; Cling, Andrew D. (2000). «Love’s Logic Lost: The Couplet of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116». ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes and Reviews. Routledge. 13 (3): 14–19. doi:10.1080/08957690009598107. ISSN 1940-3364. S2CID 162306705.

- Passannanti, Erminia (2020). «William Shakespeare. Sonetto N. 116: Amore come simbolo di verità e resistenza». Academia.edu.

- Trevor, Douglas (2007). «Shakespeare’s Love Objects». In Schoenfeldt, Michael (ed.). A Companion to Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Grand Rapids: Blackwell Limited. doi:10.1111/b.9781405121552.2007.00015.x. ISBN 9781405121552.

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485. — Volume I and Volume II at the Internet Archive

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare’s Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare’s Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951. — 1st edition at the Internet Archive

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover’s Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare’s Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

See also[edit]

- When Love Speaks

External links[edit]

- Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116: (explained in hindi)

- From the British Library and NPR, a reading of Sonnet 116 in a reproduction of Shakespeare’s dialect

Sonnet 116 public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Sonnet 116 in the 1609 Quarto.

This is one of Shakespeare’s best-known love sonnets and a popular choice for reading at wedding ceremonies. It is written as if the first person narrator, the poet, is speaking to one person or perhaps a small intelligent audience about his view of love. It is thought to be an autobiographical poem about Shakespeare’s experience of a loving relationship, probably a young man, although the gender is irrelevant to our understanding of the meaning and the exquisite quality of the composition. However, at the time many sonneteers wrote as an intellectual exercise intended for friends and other writers who were also producing sonnets. It is believed by many not to be the case with Shakespeare’s sonnet sequences, although some dispute this.

About Sonnets

A sonnet is a poem which expresses a thought or idea and develops it, often cleverly and wittily.

The sonnet genre is often, although not always, about ideals or hypothetical situations. It reaches back to the Medieval Romances, where a woman is loved and idealised by a worshipping admirer. For example, Sir Philip Sydney in the Astrophil and Stella sonnet sequence wrote in this mode. Poems were circulated within groups of educated intellectuals and they did not necessarily reflect the poet’s true emotions, but were a form of intellectual showing-off! This may not have been true of all; it is a matter of academic debate today. It is generally believed, however, that Shakespeare’s sonnets were autobiographical.

Sonnets are made up of fourteen lines, each being ten syllables long. Its rhymes are arranged according to one of the following schemes:

• Italian, where eight lines consisting of two quatrains make up the first section of the sonnet, called an octave. This section will explore a problem or an idea. It is followed by the next section of six lines called a sestet, that forms the ‘answer’ or a counter-view. This style of sonnet is also sometimes called a Petrarchan sonnet.

• English, which comprises three quatrains, making twelve lines in total, followed by a rhyming couplet. They too explore an idea. The ‘answer’ or resolution comes in the final couplet. Shakespeare’s sonnets follow this pattern. Edmund Spenser’s sonnets are a variant.

At the break in the sonnet — in Italian after the first eight lines, in English after twelve lines — there is a ‘turn’ or volta, after which there will be a change or new perspective on the preceding idea.

Language

The metre is iambic pentameter, that is five pairs of stressed and unstressed syllables to the line. The effect is stately and rhythmic, and conveys an impression of dignity and seriousness. Shakespeare’s sonnets follow this pattern.

Rhyme Scheme

The rhyming pattern comprises three sets of four lines, forming quatrains, followed by a closed rhyming couplet.

In sonnet 116 it forms ABAB, CDCD, EFEF, GG. This is typical of Shakespeare’s compositions. For contemporary readers today not all the rhymes are perfect because of changed pronunciation, but in Shakespeare’s time they would probably have rhymed perfectly.

This is Sonnet 116 read in Received Pronunciation (contemporary “King’s English”) and Original Pronunciation (as it would have sounded in Shakespeare’s day):

In total, it is believed that Shakespeare wrote 154 sonnets, in addition to the thirty-seven plays that are also attributed to him. Many believe Shakespeare’s sonnets are addressed to two different people he may have known.

The first 126 sonnets seem to be speaking to a young man with whom Shakespeare was very close. As a result of this, much has been speculated about The Bard’s sexuality; it is to this young man that Sonnet 116 is addressed. The other sonnets Shakespeare wrote are written to a mysterious woman whose identity is unknown. Scholars have referred to her simply as the Dark Woman and must have been written about her identity.

Sonnet 116 William ShakespeareLet me not to the marriage of true mindsAdmit impediments. Love is not loveWhich alters when it alteration finds,Or bends with the remover to remove:O, no! it is an ever-fixed mark,That looks on tempests and is never shaken;It is the star to every wandering bark,Whose worth's unknown, although his height be taken.Love's not Time's fool, though rosy lips and cheeksWithin his bending sickle's compass come;Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks,But bears it out even to the edge of doom. If this be error and upon me proved, I never writ, nor no man ever loved.

Summary

In ‘Sonnet 116: Let me not to the marriage of true minds,’ Shakespeare’s speaker is ruminating on love. He says that love never changes, and if it does, it was not true or real in the first place.

He compares love to a star that is always seen and never changing. It is real and permanent, and it is something on which a person can count. Even though the people in love may change as time passes, their love will not. The speaker closes by saying that no man has ever truly loved before if he is wrong about this.

Themes

Shakespeare used some of his most familiar themes in ‘Sonnet 116’. These include time, love, and the nature of relationships. In the fourteen lines of this sonnet, he delves into what true love is and whether or not it’s real. He uses a metaphor to compare love to a star that’s always present and never changes. He is so confident in this opinion that he asserts no man has ever loved before if he’s wrong. Shakespeare also brings elements of time into the poem. He emphasizes the fact that time knows no boundaries, and even if the people in the relationship change, the love doesn’t.

Historical Background

Many believe the mysterious young man for whom this and many other of Shakespeare’s sonnets were written was the Earl of Southampton, Henry Wriothesly. Wriothesly was Shakespeare’s patron, and The Bard’s Venus and Adonis and Tarquin and Lucrece were both dedicated to the young man.

Structure and Form

This is a true Shakespearean sonnet, also referred to as an Elizabethan or English sonnet. This type of sonnet contains fourteen lines, which are separated into three quatrains (four lines) and end with a rhyming couplet (two lines). The rhyme scheme of this sonnet is abab cdcd efef gg. Like most of Shakespeare’s works, this sonnet is written in iambic pentameter, which means each line consists of ten syllables, and within those ten syllables, there are five pairs, which are called iambs (one stressed syllable followed by an unstressed syllable).

Literary Devices

Shakespeare makes use of several literary devices in ‘Sonnet 116,’ these include but are not limited to alliteration, examples of caesurae, and personification. The first, alliteration, is concerned with the repetition of words that begin with the same consonant sound. For example, “marriage” and “minds” in the first line and “remover” and “remove” in the fourth line.

Caeusrae is used when the poet wants to create a pause in the middle of a line. The second line of the poem is a good example. It reads: “Admit impediments. Love is not love”. There is another example in line eight. It reads: “Whose worth’s unknown, although his height is taken.” The “pause” the poet uses might be marked with punctuation or intuited through the metrical pattern.

Personification is seen in the finals sestet of the poem. There, Shakespeare personifies “Time” and “Love,” something that he does more than once in his 154 sonnets. He refers to them as forces that have the ability to change lives purposefully.

Detailed Analysis

While this sonnet is clumped in with the other sonnets that are assumed to be dedicated to an unknown young man in Shakespeare’s life, this poem does not seem to directly address anyone. In fact, Sonnet 116 seems to be the speaker’s—in this case, perhaps Shakespeare—ruminations on love and what it is. The best way to analyze Shakespeare’s sonnets is to examine them line-by-line, which is what will follow.

In the first two lines, Shakespeare writes,

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments.

These lines are perhaps the most famous in the history of poetry, regardless of whether or not one recognizes them as belonging to Shakespeare. Straight away, Shakespeare uses the metaphor of marriage to compare it to true, real love. He is saying that there is no reason why two people who truly love should not be together; nothing should stand in their way. Perhaps he is speaking about his feelings for the unknown young man for whom the sonnet is written. Shakespeare was unhappily married to Anne Hathaway, and so perhaps he was rationalizing his feelings for the young man by stating there was no reason, even if one is already married, that two people who are truly in love should not be together. The second half of the second line begins a new thought, which is then carried on into the third and fourth lines. He writes,

Love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove.

Shakespeare is continuing with his thought that true love conquers all. In these lines, the speaker is telling the reader that if love changes, it is not truly loved because if it changes, or if someone tries to “remove” it, nothing will change it. Love does not stop just because something is altered. As clichéd as it sounds, true love, real love, lasts forever.

The second quatrain of Sonnet 116 begins with some vivid and beautiful imagery, and it continues with the final thought pondered in the first quatrain. Now that Shakespeare has established what love is not—fleeting and ever-changing—he can now tell us what love is. He writes,

O no, it is an ever fixed mark

That looks on tempests and is never shaken…

Here, Shakespeare tells his readers that love is something that does not shift, change, or move; it is constant and in the same place, and it can weather even the most harrowing of storms or tempests and is never even shaken, let alone defeated. While weak, it can be argued here that Shakespeare decides to personify love since it is something that is intangible and not something that can be defeated by something tangible, such as a storm. In the next line, Shakespeare uses the metaphor of the North Star to discuss love. He writes,

It is the star to every wand’ring bark,

Whose worth’s unknown, although his height be taken.

To Shakespeare, love is the star that guides every bark, or ship, on the water, and while it is priceless, it can be measured. These two lines are interesting and worth noting. Shakespeare concedes that love’s worth is not known, but he says it can be measured. How he neglects to tell his reader, but perhaps he is assuming the reader will understand the different ways in which one can measure love: through time and actions. With that thought, the second quatrain ends.

The third quatrain parallels the first, and Shakespeare returns to telling his readers what love is not. He writes,

Love’s not Time’s fool, though rosy lips and cheeks

Within his bending sickle’s compass come…

Notice the capitalization of the word “Time.” Shakespeare is personifying time as a person, specifically, Death. He says that love is not the fool of time. One’s rosy lips and cheeks will certainly pale with age, as “his bending sickle’s compass come.” Shakespeare’s diction is important here, particularly with his use of the word “sickle.” Who is the person with whom the sickle is most greatly associated? Death. We are assured here that Death will certainly come, but that will not stop love. It may kill the lover, but the love itself is eternal. This thought is continued in lines eleven and twelve, the final two lines of the third quatrain. Shakespeare writes,

Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks,

But bears it out even to the edge of doom.

He is simply stating here that love does not change over the course of time; instead, it continues on even after the world has ended (“the edge of doom”).

Shakespeare uses lines thirteen and fourteen, the final couplet of Sonnet 116, to assert just how truly he believes that love is everlasting and conquers all. He writes,

If this be error and upon me proved

I never writ, nor no man ever loved.

In this part of Sonnet 116, Shakespeare is telling his reader that if someone proves he is wrong about love, then he never wrote the following words, and no man ever loved. He is conveying here that if his words are untrue, nothing else would exist. The words he just wrote would have never been written, and no man would have ever loved before. He is adamant about this, and his tough words are what strengthen the sonnet itself. The speaker and poet himself are convinced that love is real, true, and everlasting.

Similar Poetry

Readers who enjoyed this poem should also look into some of Shakespeare’s most popular sonnets. These include ‘Sonnet 130’ and ‘Sonnet 18‘. The first is recognized by its opening line, “My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun,” while the latter starts with the line “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” Also, make sure to check out our list of 154 Shakespearean Sonnets and our list of the top 10 Greatest Love Poems of All Time.