It’s a sadly unhelpful error message and it’s one that you’ll see quite often when learning Python.

What does SyntaxError: invalid syntax mean?

What is Python trying to tell you with this error and how can you fix your code to make Python happy?

What is a SyntaxError in Python?

This is Python’s way of saying «I don’t understand you».

Python knows that what you’ve typed isn’t valid Python code but it’s not sure what advice to give you.

When you’re lucky, your SyntaxError will have some helpful advice in it:

$ python3 greet.py

File "/home/trey/greet.py", line 10

if name == "Trey"

^

SyntaxError: expected ':'

But if you’re unlucky, you’ll see the message invalid syntax with nothing more:

$ python3.9 greet.py

File "/home/trey/greet.py", line 4

name

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

This error message gives us no hints as to what might be going on outside of a line number and a bit of highlighting indicating where Python thinks the error occurred.

Causes of SyntaxError: invalid syntax

What are the likely causes of this mysterious error message?

When my Python students hit this error, the most likely causes are typically:

- Missing a colon (

:) at the end of a line or mixing up other symbols - Missing opening or closing parentheses (

(…)), brackets ([…]), braces ({…}), or quotes ("…") - Misspelled or missing keywords or mistyping syntax within a block or expression

- Attempting to use a reserved keyword as a variable name

- Incorrectly indented code or other whitespace errors

- Treating statements like expressions

- Copying Python code into the REPL or copying from the REPL into a Python file

That’s a lot of options and they’re not the only options.

How should you approach fixing this problem?

Fixing SyntaxError: invalid syntax

The first step in fixing SyntaxErrors is narrowing down the problem.

I usually take the approach of:

- Note the line number and error message from the traceback, keeping in mind that both of these just guesses that Python’s making

- Working through the above list of common causes

- Attempting to read the code as Python would, looking for syntax mistakes

- Narrowing down the problem by removing blocks of code that I suspect may be the culprit

It’s easier to address that dreaded SyntaxError: invalid syntax exception when you’re familiar with its most common causes.

Let’s attempt to build up our intuitions around SyntaxError: invalid syntax by touring the common causes of this error message.

Upgrading Python improves error messages

Before diving into specific errors, note that upgrading your Python version can drastically improve the helpfulness of common error messages.

Take this error message:

$ python3 square.py

File "/home/trey/square.py", line 2

return [

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

On Python 3.10 it looks considerably different:

$ python3.10 square.py

File "/home/trey/square.py", line 1

def square_all(numbers:

^

SyntaxError: '(' was never closed

We’re running the same square.py file in both cases:

def square_all(numbers:

return [

n**2

for n in numbers

]

But Python 3.10 showed a much more helpful message: the line number, the position, and the error message itself are all much clearer for many unclosed parentheses and braces on Python 3.10 and above.

The dreaded missing colon is another example.

Any expression that starts a new block of code needs a : at the end.

Here’s the error that Python 3.9 shows for a missing colon:

$ python3 greet.py

File "/home/trey/greet.py", line 10

if name == "Trey"

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

And here’s the same error in Python 3.10:

$ python3 greet.py

File "/home/trey/greet.py", line 10

if name == "Trey"

^

SyntaxError: expected ':'

Much more helpful, right?

It’s still a SyntaxError exception, but the message is much clearer than simply invalid syntax.

Python 3.10 also includes friendlier error messages when you use = where you likely meant ==:

>>> name = "Trey"

>>> if name = "Trey":

File "<stdin>", line 1

if name = "Trey":

^^^^^^^^^^^^^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax. Maybe you meant '==' or ':=' instead of '='?

Newer Python versions include more helpful error messages for missing commas, inline if expressions, unclosed braces/brackets/parentheses, and more.

If you have the ability to run your code on a newer version of Python, try it out.

It might help you troubleshoot your syntax errors more effectively.

Count your parentheses

Forgetting closing parentheses, brackets, and braces is also a common source of coding errors.

Fortunately, recent Python versions have started noting unclosed brackets in their SyntaxError messages.

When running this code:

def colors():

c = ['red',

'blue',

return c

Python 3.9 used to show simply invalid syntax:

$ python3.9 colors.py

File "/home/trey/colors.py", line 4

return c

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

But Python 3.10 shows a more helpful error message:

$ python3.10 colors.py

File "/home/trey/colors.py", line 2

c = ['red',

^

SyntaxError: '[' was never closed

But sometimes Python can get a little confused when guessing the cause of an error.

Take this populate.py script:

import random

import names

random_list=["a1","a2","a3","b1","b2","b3","c1","c2","c3"]

with open("one.txt","w+") as one,

open("two.txt","w+") as two,

open("three.txt","w+") as three:

for i in range(0,3):

one.write("%sn" "%s" % (names.get_first_name(),

random.choice(random_list))

two.write("%sn" "%s" % (names.get_first_name(),

random.choice(random_list))

three.write("%sn" "%s" % (names.get_first_name(),

random.choice(random_list))

When running this script, Python 3.10 shows this error message:

$ python3.10 populate.py

File "/home/trey/populate.py", line 9

one.write("%sn" "%s" %

^^^^^^^^^^^^^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax. Perhaps you forgot a comma?

The problem is that all 3 of those write method calls are missing closing parentheses.

Count your parentheses!

Many code editors highlight matching parentheses, brackets, and braces (when your cursor is at an opening parentheses the closing one will change color).

Use your code editor to see if each pair of parenthesis matches up properly (and that the one in matches seems correct).

Misspelled, missing, or misplaced keywords

Can you see what’s wrong with this line of code?

>>> drf sum_of_squares(numbers):

File "<stdin>", line 1

drf sum_of_squares(numbers):

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

We were trying to define a function, but we misspelled def as drf.

Python couldn’t figure out what we were trying to do, so it showed us that generic invalid syntax message.

What about this one?

>>> numbers = [2, 1, 3, 4, 7, 11, 18]

>>> squares = [n**2 for numbers]

File "<stdin>", line 1

squares = [n**2 for numbers]

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

Python’s pointing to the end of our comprehension and saying there’s a syntax error.

But why?

Look a bit closer.

There’s something missing in our comprehension.

We meant type this:

>>> numbers = [2, 1, 3, 4, 7, 11, 18]

>>> squares = [n**2 for n in numbers]

We were missing the in in our comprehension’s looping component.

Misspelled keywords and missing keywords often result in that mysterious invalid syntax, but extra keywords can cause trouble as well.

You can’t use reserved words as variable names in Python:

>>> class = "druid"

File "<stdin>", line 1

class = "druid"

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

Python sees that word class and it assumes we’re defining a class.

But then it sees an = sign and gets confused and can’t tell what we’re trying to do, so it throws its hands in the error and yells invalid syntax!

This one is a bit more mysterious:

>>> import urlopen from urllib.request

File "<stdin>", line 1

import urlopen from urllib.request

^^^^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

That looks right, doesn’t it?

So what’s the problem?

In Python the import…from syntax is actually a from…import syntax.

We meant to write this instead:

>>> from urllib.request import urlopen

Watch out for misspelled keywords, missing keywords, and re-arranged syntax.

Also be sure not to use reserved words as variable names (e.g. class, return, and import are invalid variable names).

Subtle spacing problems

Can you see what’s wrong in this code?

>>> class Thing:

... def __init _(self, name, color):

File "<stdin>", line 2

def __init _(self, name, color):

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

Notice the extra space in the function name (__init_ _ instead of __init__)?

Can you identify what’s wrong in this line?

>>> class Thing:

... def__init__(self, name, color):

File "<stdin>", line 2

def__init__(self, name, color):

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

This one might be harder to spot.

Everything on that line is correct except that there’s no space between def and __init__.

When one space character is valid, you can usually use more than one space character as well.

But adding an extra space in the middle of an identifier or removing spaces where there should be spaces can often cause syntax errors.

Forgotten quotes and extra quotes

If you code infrequently, you likely forget to put quotes around your strings often.

This is a very common mistake, so rest assured that you’re not alone!

Forgotten quotes can sometimes result in this cryptic invalid syntax error message:

>>> print(Four!) if n

File "<stdin>", line 1

print(Four!) if n

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

Be careful with quotes within quotes:

>>> question = 'What's that?'

File "<stdin>", line 1

question = 'What's that?'

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

You’ll need to switch to a different quote style (using double quotes for example) or escape those quotes.

Mixing up your symbols

Sometimes your syntax might look correct but you’ve actually confused one bit of syntax for another common bit of syntax.

That’s what happened here:

>>> things = {duck='purple', monkey='green'}

File "<stdin>", line 1

things = {duck='purple', monkey='green'}

^^^^^^^^^^^^^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax. Maybe you meant '==' or ':=' instead of '='?

We’re trying to make a dictionary and we’ve accidentally used = instead of : to separate our key-value pairs.

Here’s another dictionary symbol mix up:

>>> states = [

... 'Oregon': 'OR',

File "<stdin>", line 2

'Oregon': 'OR',

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

It looks like we’re trying to define a dictionary, but we started with an open square bracket ([) instead of an open curly brace ({).

Another common syntax mistake is missing periods:

File "/home/trey/file_info.py", line 15

size = path.stat()st_size

^^^^^^^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

We’re trying to access the st_size attribute on the object returned from that path.stat() call, but we’ve forgot to put a . before st_size.

Sometimes syntax errors are due to characters being swapped around:

>>> name = "Trey"

>>> name[]0

File "<stdin>", line 1

name[]0

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

And some syntax errors are due to extra symbols you didn’t intend to write:

>>> name = "Trey"

>>> name.lower.()

File "<stdin>", line 1

name.lower.()

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

We wrote an extra . before our parentheses above.

Indentation errors in disguise

Sometimes a SyntaxError is actually an indentation error in disguise.

For example this code has an else clause that’s too far indented:

import sys

name = sys.argv[1]

if name == "Trey":

print("I know you")

print("Your name is Troy... no, Trent? Trevor??")

else:

print("Hello stranger")

When we run the code we’ll see a SyntaxError:

$ python greet.py

File "/home/trey/greet.py", line 8

else:

^^^^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

Indentation issues often result in IndentationError exceptions, but sometimes they’ll manifest as SyntaxError exceptions instead.

Embedding statements within statements

A «statement» is either a block of Python code or a single line of Python code that can stand on its own.

An «expression» is a chunk of Python code that evaluates to a value.

Expressions contain identifiers (i.e. variables), literals (e.g. [1, 2], "hi", and 4), and operators (e.g. +, in, and *).

In Python we can embed one expression within another.

But some expressions are actually «statements» which must be a line all on their own.

Here we’ve tried to embed one statement within another:

>>> def square_all(numbers):

... return result = [n**2 for n in numbers]

File "<stdin>", line 2

return result = [n**2 for n in numbers]

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

Assignments are statements in Python (result = ... is a statement).

Python’s return is also a statement.

We’ve tried to embed one statement inside another and Python didn’t understand us.

We likely meant either this:

def square_all(numbers):

result = [n**2 for n in numbers]

return result

Or this:

def square_all(numbers):

return [n**2 for n in numbers]

Here’s the same issue with the global statement (see assigning to global variables):

>>> def connect(*args, **kwargs):

... global _connection = sqlite3.connect(*args, **kwargs)

File "<stdin>", line 2

global _connection = sqlite3.connect(*args, **kwargs)

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

And the same issue with the del statement:

trey_count = del counts['Trey']

File "<stdin>", line 1

trey_count = del counts['Trey']

^^^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

If assignment is involves in your statement-inside-a-statement, an assignment expression (via Python’s walrus operator) may be helpful in resolving your issue.

Though often the simplest solution is to split your code into multiple statements over multiple lines.

Errors that appear only in the Python REPL

Some errors are a bit less helpful within the Python REPL.

Take this invalid syntax error:

def square_all(numbers:

return [

File "<stdin>", line 2

return [

^^^^^^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

We’ll see that error within the Python REPL even on Python 3.11.

The issue is that the first line doesn’t have a closing parentheses.

Python 3.10+ would properly point this out if we ran our code from a .py file instead:

$ python3.10 square.py

File "/home/trey/square.py", line 1

def square_all(numbers:

^

SyntaxError: '(' was never closed

But at the REPL Python doesn’t parse our code the same way (it parses block-by-block in the REPL) and sometimes error messages are a bit less helpful within the REPL as a result.

Here’s another REPL-specific error:

>>> def greet(name):

... print(f"Howdy {name}!")

... greet("Trey")

File "<stdin>", line 3

greet("Trey")

^^^^^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

This is valid Python code:

def greet(name):

print(f"Howdy {name}!")

greet("Trey")

But that can’t be copy-pasted directly into the REPL.

In the Python REPL a blank line is needed after a block of code to end that block.

So we’d need to put a newline between the function definition and the function call:

>>> def greet(name):

... print(f"Howdy {name}!")

...

>>> greet("Trey")

Howdy Trey!

Some errors are due to code that feels like it should work in a Python REPL but doesn’t.

For example running python from within your Python REPL doesn’t work:

>>> python greet.py

File "<stdin>", line 1

python greet.py

^^^^^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

>>> python -m pip install django

File "<stdin>", line 1

python -m pip install django

^^^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

The above commands would work from our system command-prompt, but they don’t work within the Python REPL.

If you’re trying to launch Python or send a command to your prompt outside Python (like ls or dir), you’ll need to do it from your system command prompt (Terminal, Powershell, Command Prompt, etc.).

You can only type valid Python code from within the Python REPL.

Problems copy-pasting from the REPL

Copy-pasting from the Python REPL into a .py file will also result in syntax errors.

Here’s we’re running a file that has >>> prefixes before each line:

$ python numbers.py

File "/home/trey/numbers.py", line 1

>>> n = 4

^^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

This isn’t a valid Python program:

>>> n = 4

>>> print(n**2)

But this is a valid Python program:

You’ll need to be careful about empty lines when copy-pasting from a .py file into a Python REPL and you’ll need to be careful about >>> and ... prefixes and command output when copy-pasting from a REPL into a .py file.

The line number is just a «best guess»

It used to be that the line number for an error would usually represent the place that Python got confused about your syntax.

That line number was often one or more lines after the actual error.

In recent versions of Python, the core developers have updated these line numbers in an attempt to make them more accurate.

For example here’s an error on Python 3.9 due to a missing comma:

$ python3.9 greet.py

File "/home/trey/greet.py", line 4

name

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

And here’s the same error in Python 3.10:

$ python3.10 greet.py

File "/home/greet.py", line 3

"Hello there"

^^^^^^^^^^^^^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax. Perhaps you forgot a comma?

Python’s given us a helpful hint on Python 3.10.

But it’s also made a different guess about what line the error is on.

As you can see from the greet.py file, line 3 ("Hello there") is the better guess in this case, as that’s where the comma is needed.

def greet(name):

print(

"Hello there"

name

)

While deciphering tracebacks, keep in mind that the line number is just Python’s best guess as to where the error occurred.

SyntaxError exceptions happen all the time

If your code frequently results in SyntaxError exceptions, don’t fret.

These kinds of exceptions happen all the time.

When you’re newer to Python, you’ll find that it’s often a challenge to remember the exact syntax for the statements you’re writing.

But more experienced Python programmers also experience syntax errors.

I make typos in my code quite often.

I have a linter installed in my text editor to help me catch those typos though.

I recommend searching for a «Python» or «Python linter» extension for your favorite code editor so you can spot these issues quickly every time you save your .py files.

Once you get past syntax errors, you’ll likely hit other types of exceptions. Watch the exception screencast series for more on reading tracebacks and exception handling in Python.

Python известен своим простым синтаксисом. Однако, когда вы изучаете Python в первый раз или когда вы попали на Python с большим опытом работы на другом языке программирования, вы можете столкнуться с некоторыми вещами, которые Python не позволяет. Если вы когда-либо получали + SyntaxError + при попытке запустить код Python, то это руководство может вам помочь. В этом руководстве вы увидите общие примеры неправильного синтаксиса в Python и узнаете, как решить эту проблему.

Неверный синтаксис в Python

Когда вы запускаете ваш код Python, интерпретатор сначала анализирует его, чтобы преобразовать в байтовый код Python, который он затем выполнит. Интерпретатор найдет любой недопустимый синтаксис в Python на этом первом этапе выполнения программы, также известном как этап синтаксического анализа . Если интерпретатор не может успешно проанализировать ваш код Python, это означает, что вы использовали неверный синтаксис где-то в вашем коде. Переводчик попытается показать вам, где произошла эта ошибка.

Когда вы изучаете Python в первый раз, может быть неприятно получить + SyntaxError +. Python попытается помочь вам определить, где в вашем коде указан неверный синтаксис, но предоставляемый им traceback может немного сбить с толку. Иногда код, на который он указывает, вполне подходит.

*Примечание:* Если ваш код *синтаксически* правильный, то вы можете получить другие исключения, которые не являются `+ SyntaxError +`. Чтобы узнать больше о других исключениях Python и о том, как их обрабатывать, ознакомьтесь с https://realpython.com/python-exceptions/[Python Exceptions: Введение].

Вы не можете обрабатывать неправильный синтаксис в Python, как и другие исключения. Даже если вы попытаетесь обернуть блок + try + и + кроме + вокруг кода с неверным синтаксисом, вы все равно увидите, что интерпретатор вызовет + SyntaxError +.

+ SyntaxError + Исключение и трассировка

Когда интерпретатор обнаруживает неверный синтаксис в коде Python, он вызовет исключение + SyntaxError + и предоставит трассировку с некоторой полезной информацией, которая поможет вам отладить ошибку. Вот некоторый код, который содержит недопустимый синтаксис в Python:

1 # theofficefacts.py

2 ages = {

3 'pam': 24,

4 'jim': 24

5 'michael': 43

6 }

7 print(f'Michael is {ages["michael"]} years old.')Вы можете увидеть недопустимый синтаксис в литерале словаря в строке 4. Во второй записи + 'jim' + пропущена запятая. Если вы попытаетесь запустить этот код как есть, вы получите следующую трассировку:

$ python theofficefacts.py

File "theofficefacts.py", line 5

'michael': 43

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntaxОбратите внимание, что сообщение трассировки обнаруживает ошибку в строке 5, а не в строке 4. Интерпретатор Python пытается указать, где находится неправильный синтаксис. Тем не менее, он может только указать, где он впервые заметил проблему. Когда вы получите трассировку + SyntaxError + и код, на который указывает трассировка, выглядит нормально, тогда вы захотите начать движение назад по коду, пока не сможете определить, что не так.

В приведенном выше примере нет проблемы с запятой, в зависимости от того, что следует после нее. Например, нет проблемы с отсутствующей запятой после + 'michael' + в строке 5. Но как только переводчик сталкивается с чем-то, что не имеет смысла, он может лишь указать вам на первое, что он обнаружил, что он не может понять.

*Примечание:* В этом руководстве предполагается, что вы знакомы с основами *tracebacks* в Python. Чтобы узнать больше о трассировке Python и о том, как их читать, ознакомьтесь с https://realpython.com/python-traceback/[Understanding Python Traceback].

Существует несколько элементов трассировки + SyntaxError +, которые могут помочь вам определить, где в вашем коде содержится неверный синтаксис:

-

Имя файла , где встречается неверный синтаксис

-

Номер строки и воспроизводимая строка кода, где возникла проблема

-

Знак (

+ ^ +) в строке ниже воспроизводимого кода, который показывает точку в коде, которая имеет проблему -

Сообщение об ошибке , которое следует за типом исключения

+ SyntaxError +, которое может предоставить информацию, которая поможет вам определить проблему

В приведенном выше примере имя файла было + theofficefacts.py +, номер строки был 5, а каретка указывала на закрывающую кавычку из словарного ключа + michael +. Трассировка + SyntaxError + может не указывать на реальную проблему, но она будет указывать на первое место, где интерпретатор не может понять синтаксис.

Есть два других исключения, которые вы можете увидеть в Python. Они эквивалентны + SyntaxError +, но имеют разные имена:

-

+ +IndentationError -

+ +TabError

Оба эти исключения наследуются от класса + SyntaxError +, но это особые случаи, когда речь идет об отступе. + IndentationError + возникает, когда уровни отступа вашего кода не совпадают. + TabError + возникает, когда ваш код использует и табуляцию, и пробелы в одном файле. Вы познакомитесь с этими исключениями более подробно в следующем разделе.

Общие проблемы с синтаксисом

Когда вы впервые сталкиваетесь с + SyntaxError +, полезно знать, почему возникла проблема и что вы можете сделать, чтобы исправить неверный синтаксис в вашем коде Python. В следующих разделах вы увидите некоторые из наиболее распространенных причин, по которым может быть вызвано «+ SyntaxError +», и способы их устранения.

Неправильное использование оператора присваивания (+ = +)

В Python есть несколько случаев, когда вы не можете назначать объекты. Некоторые примеры присваивают литералам и вызовам функций. В приведенном ниже блоке кода вы можете увидеть несколько примеров, которые пытаются это сделать, и получающиеся в результате трассировки + SyntaxError +:

>>>

>>> len('hello') = 5

File "<stdin>", line 1

SyntaxError: can't assign to function call

>>> 'foo' = 1

File "<stdin>", line 1

SyntaxError: can't assign to literal

>>> 1 = 'foo'

File "<stdin>", line 1

SyntaxError: can't assign to literalПервый пример пытается присвоить значение + 5 + вызову + len () +. Сообщение + SyntaxError + очень полезно в этом случае. Он говорит вам, что вы не можете присвоить значение вызову функции.

Второй и третий примеры пытаются присвоить литералам строку и целое число. То же правило верно и для других литеральных значений. И снова сообщения трассировки указывают, что проблема возникает, когда вы пытаетесь присвоить значение литералу.

*Примечание:* В приведенных выше примерах отсутствует повторяющаяся строка кода и каретка (`+ ^ +`), указывающая на проблему в трассировке. Исключение и обратная трассировка, которые вы видите, будут другими, когда вы находитесь в REPL и пытаетесь выполнить этот код из файла. Если бы этот код был в файле, то вы бы получили повторяющуюся строку кода и указали на проблему, как вы видели в других случаях в этом руководстве.

Вероятно, ваше намерение не состоит в том, чтобы присвоить значение литералу или вызову функции. Например, это может произойти, если вы случайно пропустите дополнительный знак равенства (+ = +), что превратит назначение в сравнение. Сравнение, как вы можете видеть ниже, будет правильным:

>>>

>>> len('hello') == 5

TrueВ большинстве случаев, когда Python сообщает вам, что вы делаете присвоение чему-то, что не может быть назначено, вы сначала можете проверить, чтобы убедиться, что оператор не должен быть логическим выражением. Вы также можете столкнуться с этой проблемой, когда пытаетесь присвоить значение ключевому слову Python, о котором вы расскажете в следующем разделе.

Неправильное написание, отсутствие или неправильное использование ключевых слов Python

Ключевые слова Python — это набор защищенных слов , которые имеют особое значение в Python. Это слова, которые вы не можете использовать в качестве идентификаторов, переменных или имен функций в своем коде. Они являются частью языка и могут использоваться только в контексте, который допускает Python.

Существует три распространенных способа ошибочного использования ключевых слов:

-

Неправильное написание ключевое слово

-

Отсутствует ключевое слово

-

Неправильное использование ключевого слова

Если вы неправильно написали ключевое слово в своем коде Python, вы получите + SyntaxError +. Например, вот что происходит, если вы пишете ключевое слово + for + неправильно:

>>>

>>> fro i in range(10):

File "<stdin>", line 1

fro i in range(10):

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntaxСообщение читается как + SyntaxError: неверный синтаксис +, но это не очень полезно. Трассировка указывает на первое место, где Python может обнаружить, что что-то не так. Чтобы исправить эту ошибку, убедитесь, что все ваши ключевые слова Python написаны правильно.

Другая распространенная проблема с ключевыми словами — это когда вы вообще их пропускаете:

>>>

>>> for i range(10):

File "<stdin>", line 1

for i range(10):

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntaxЕще раз, сообщение об исключении не очень полезно, но трассировка действительно пытается указать вам правильное направление. Если вы отойдете от каретки, то увидите, что ключевое слово + in + отсутствует в синтаксисе цикла + for +.

Вы также можете неправильно использовать защищенное ключевое слово Python. Помните, что ключевые слова разрешено использовать только в определенных ситуациях. Если вы используете их неправильно, у вас будет неправильный синтаксис в коде Python. Типичным примером этого является использование https://realpython.com/python-for-loop/#the-break-and-continue-statements [+ continue + или + break +] вне цикла. Это может легко произойти во время разработки, когда вы реализуете вещи и когда-то перемещаете логику за пределы цикла:

>>>

>>> names = ['pam', 'jim', 'michael']

>>> if 'jim' in names:

... print('jim found')

... break

...

File "<stdin>", line 3

SyntaxError: 'break' outside loop

>>> if 'jim' in names:

... print('jim found')

... continue

...

File "<stdin>", line 3

SyntaxError: 'continue' not properly in loopЗдесь Python отлично говорит, что именно не так. Сообщения " 'break' вне цикла " и " 'continue' не в цикле должным образом " помогут вам точно определить, что делать. Если бы этот код был в файле, то Python также имел бы курсор, указывающий прямо на неправильно использованное ключевое слово.

Другой пример — если вы пытаетесь назначить ключевое слово Python переменной или использовать ключевое слово для определения функции:

>>>

>>> pass = True

File "<stdin>", line 1

pass = True

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

>>> def pass():

File "<stdin>", line 1

def pass():

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntaxКогда вы пытаетесь присвоить значение + pass +, или когда вы пытаетесь определить новую функцию с именем + pass +, вы получите ` + SyntaxError + и снова увидеть сообщение + «неверный синтаксис» + `.

Может быть немного сложнее решить этот тип недопустимого синтаксиса в коде Python, потому что код выглядит хорошо снаружи. Если ваш код выглядит хорошо, но вы все еще получаете + SyntaxError +, то вы можете рассмотреть возможность проверки имени переменной или имени функции, которое вы хотите использовать, по списку ключевых слов для версии Python, которую вы используете.

Список защищенных ключевых слов менялся с каждой новой версией Python. Например, в Python 3.6 вы можете использовать + await + в качестве имени переменной или имени функции, но в Python 3.7 это слово было добавлено в список ключевых слов. Теперь, если вы попытаетесь использовать + await + в качестве имени переменной или функции, это вызовет + SyntaxError +, если ваш код для Python 3.7 или более поздней версии.

Другим примером этого является + print +, который отличается в Python 2 от Python 3:

| Version | print Type |

Takes A Value |

|---|---|---|

|

Python 2 |

keyword |

no |

|

Python 3 |

built-in function |

yes |

+ print + — это ключевое слово в Python 2, поэтому вы не можете присвоить ему значение. Однако в Python 3 это встроенная функция, которой можно присваивать значения.

Вы можете запустить следующий код, чтобы увидеть список ключевых слов в любой версии Python, которую вы используете:

import keyword

print(keyword.kwlist)+ keyword + также предоставляет полезную + keyword.iskeyword () +. Если вам просто нужен быстрый способ проверить переменную + pass +, то вы можете использовать следующую однострочную строку:

>>>

>>> import keyword; keyword.iskeyword('pass')

TrueЭтот код быстро сообщит вам, является ли идентификатор, который вы пытаетесь использовать, ключевым словом или нет.

Отсутствующие скобки, скобки и цитаты

Часто причиной неправильного синтаксиса в коде Python являются пропущенные или несовпадающие закрывающие скобки, скобки или кавычки. Их может быть трудно обнаружить в очень длинных строках вложенных скобок или длинных многострочных блоках. Вы можете найти несоответствующие или пропущенные кавычки с помощью обратных трассировок Python:

>>>

>>> message = 'don't'

File "<stdin>", line 1

message = 'don't'

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntaxЗдесь трассировка указывает на неверный код, где после закрывающей одинарной кавычки стоит + t '+. Чтобы это исправить, вы можете сделать одно из двух изменений:

-

Escape одиночная кавычка с обратной косой чертой (

+ 'don ' t '+) -

Окружить всю строку в двойных кавычках (

" не ")

Другая распространенная ошибка — забыть закрыть строку. Как для строк с двойными, так и с одинарными кавычками ситуация и обратная трассировка одинаковы:

>>>

>>> message = "This is an unclosed string

File "<stdin>", line 1

message = "This is an unclosed string

^

SyntaxError: EOL while scanning string literalНа этот раз каретка в трассировке указывает прямо на код проблемы. Сообщение + SyntaxError +, " EOL при сканировании строкового литерала ", немного более конкретно и полезно при определении проблемы. Это означает, что интерпретатор Python дошел до конца строки (EOL) до закрытия открытой строки. Чтобы это исправить, закройте строку с кавычкой, которая совпадает с той, которую вы использовали для ее запуска. В этом случае это будет двойная кавычка (`+» + `).

Кавычки, отсутствующие в инструкциях внутри f-string, также могут привести к неверному синтаксису в Python:

1 # theofficefacts.py

2 ages = {

3 'pam': 24,

4 'jim': 24,

5 'michael': 43

6 }

7 print(f'Michael is {ages["michael]} years old.')Здесь, ссылка на словарь + ages + внутри напечатанной f-строки пропускает закрывающую двойную кавычку из ссылки на ключ. Итоговая трассировка выглядит следующим образом:

$ python theofficefacts.py

File "theofficefacts.py", line 7

print(f'Michael is {ages["michael]} years old.')

^

SyntaxError: f-string: unterminated stringPython идентифицирует проблему и сообщает, что она существует внутри f-строки. Сообщение " неопределенная строка " также указывает на проблему. Каретка в этом случае указывает только на начало струны.

Это может быть не так полезно, как когда каретка указывает на проблемную область струны, но она сужает область поиска. Где-то внутри этой f-строки есть неопределенная строка. Вы просто должны узнать где. Чтобы решить эту проблему, убедитесь, что присутствуют все внутренние кавычки и скобки f-строки.

Ситуация в основном отсутствует в скобках и скобках. Например, если вы исключите закрывающую квадратную скобку из списка, Python обнаружит это и укажет на это. Однако есть несколько вариантов этого. Первый — оставить закрывающую скобку вне списка:

# missing.py

def foo():

return [1, 2, 3

print(foo())Когда вы запустите этот код, вам скажут, что есть проблема с вызовом + print () +:

$ python missing.py

File "missing.py", line 5

print(foo())

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntaxЗдесь происходит то, что Python думает, что список содержит три элемента: + 1 +, + 2 + и +3 print (foo ()) +. Python использует whitespace для логической группировки вещей, и потому что нет запятой или скобки, отделяющей + 3 + от `+ print (foo ()) + `, Python объединяет их вместе как третий элемент списка.

Еще один вариант — добавить запятую после последнего элемента в списке, оставляя при этом закрывающую квадратную скобку:

# missing.py

def foo():

return [1, 2, 3,

print(foo())Теперь вы получаете другую трассировку:

$ python missing.py

File "missing.py", line 6

^

SyntaxError: unexpected EOF while parsingВ предыдущем примере + 3 + и + print (foo ()) + были объединены в один элемент, но здесь вы видите запятую, разделяющую два. Теперь вызов + print (foo ()) + добавляется в качестве четвертого элемента списка, и Python достигает конца файла без закрывающей скобки. В трассировке говорится, что Python дошел до конца файла (EOF), но ожидал чего-то другого.

В этом примере Python ожидал закрывающую скобку (+] +), но повторяющаяся строка и каретка не очень помогают. Отсутствующие круглые скобки и скобки сложно определить Python. Иногда единственное, что вы можете сделать, это начать с каретки и двигаться назад, пока вы не сможете определить, чего не хватает или что нет.

Ошибочный синтаксис словаря

Вы видели ссылку: # syntaxerror-exception-and-traceback [ранее], чтобы вы могли получить + SyntaxError +, если не указывать запятую в словарном элементе. Другая форма недопустимого синтаксиса в словарях Python — это использование знака равенства (+ = +) для разделения ключей и значений вместо двоеточия:

>>>

>>> ages = {'pam'=24}

File "<stdin>", line 1

ages = {'pam'=24}

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntaxЕще раз, это сообщение об ошибке не очень полезно. Повторная линия и каретка, однако, очень полезны! Они указывают прямо на характер проблемы.

Этот тип проблемы распространен, если вы путаете синтаксис Python с синтаксисом других языков программирования. Вы также увидите это, если перепутаете определение словаря с вызовом + dict () +. Чтобы это исправить, вы можете заменить знак равенства двоеточием. Вы также можете переключиться на использование + dict () +:

>>>

>>> ages = dict(pam=24)

>>> ages

{'pam': 24}Вы можете использовать + dict () + для определения словаря, если этот синтаксис более полезен.

Использование неправильного отступа

Существует два подкласса + SyntaxError +, которые конкретно занимаются проблемами отступов:

-

+ +IndentationError -

+ +TabError

В то время как другие языки программирования используют фигурные скобки для обозначения блоков кода, Python использует whitespace. Это означает, что Python ожидает, что пробелы в вашем коде будут вести себя предсказуемо. Он вызовет + IndentationError + , если в блоке кода есть строка с неправильным количеством пробелов:

1 # indentation.py

2 def foo():

3 for i in range(10):

4 print(i)

5 print('done')

6

7 foo()Это может быть сложно увидеть, но в строке 5 есть только два пробела с отступом. Он должен соответствовать выражению цикла + for +, которое на 4 пробела больше. К счастью, Python может легко определить это и быстро расскажет вам, в чем проблема.

Здесь также есть некоторая двусмысленность. Является ли строка + print ('done') + after циклом + for + или inside блоком цикла + for +? Когда вы запустите приведенный выше код, вы увидите следующую ошибку:

$ python indentation.py

File "indentation.py", line 5

print('done')

^

IndentationError: unindent does not match any outer indentation levelХотя трассировка выглядит во многом как трассировка + SyntaxError +, на самом деле это + IndentationError +. Сообщение об ошибке также очень полезно. Он говорит вам, что уровень отступа строки не соответствует ни одному другому уровню отступа. Другими словами, + print ('done') + это отступ с двумя пробелами, но Python не может найти любую другую строку кода, соответствующую этому уровню отступа. Вы можете быстро это исправить, убедившись, что код соответствует ожидаемому уровню отступа.

Другой тип + SyntaxError + — это + TabError + , который вы будете видеть всякий раз, когда есть строка, содержащая либо табуляцию, либо пробелы для отступа, в то время как остальная часть файла содержит другую. Это может скрыться, пока Python не покажет это вам!

Если размер вкладки равен ширине пробелов на каждом уровне отступа, то может показаться, что все строки находятся на одном уровне. Однако, если одна строка имеет отступ с использованием пробелов, а другая — с помощью табуляции, Python укажет на это как на проблему:

1 # indentation.py

2 def foo():

3 for i in range(10):

4 print(i)

5 print('done')

6

7 foo()Здесь строка 5 имеет отступ вместо 4 пробелов. Этот блок кода может выглядеть идеально для вас, или он может выглядеть совершенно неправильно, в зависимости от настроек вашей системы.

Python, однако, сразу заметит проблему. Но прежде чем запускать код, чтобы увидеть, что Python скажет вам, что это неправильно, вам может быть полезно посмотреть пример того, как код выглядит при различных настройках ширины вкладки:

$ tabs 4 # Sets the shell tab width to 4 spaces

$ cat -n indentation.py

1 # indentation.py

2 def foo():

3 for i in range(10)

4 print(i)

5 print('done')

6

7 foo()

$ tabs 8 # Sets the shell tab width to 8 spaces (standard)

$ cat -n indentation.py

1 # indentation.py

2 def foo():

3 for i in range(10)

4 print(i)

5 print('done')

6

7 foo()

$ tabs 3 # Sets the shell tab width to 3 spaces

$ cat -n indentation.py

1 # indentation.py

2 def foo():

3 for i in range(10)

4 print(i)

5 print('done')

6

7 foo()Обратите внимание на разницу в отображении между тремя примерами выше. Большая часть кода использует 4 пробела для каждого уровня отступа, но строка 5 использует одну вкладку во всех трех примерах. Ширина вкладки изменяется в зависимости от настройки tab width :

-

Если ширина вкладки равна 4 , то оператор

+ print +будет выглядеть так, как будто он находится вне цикла+ for +. Консоль выведет+ 'done' +в конце цикла. -

Если ширина табуляции равна 8 , что является стандартным для многих систем, то оператор

+ print +будет выглядеть так, как будто он находится внутри цикла+ for +. Консоль будет печатать+ 'done' +после каждого числа. -

Если ширина табуляции равна 3 , то оператор

+ print +выглядит неуместно. В этом случае строка 5 не соответствует ни одному уровню отступа.

Когда вы запустите код, вы получите следующую ошибку и трассировку:

$ python indentation.py

File "indentation.py", line 5

print('done')

^

TabError: inconsistent use of tabs and spaces in indentationОбратите внимание на + TabError + вместо обычного + SyntaxError +. Python указывает на проблемную строку и дает вам полезное сообщение об ошибке. Это ясно говорит о том, что в одном и том же файле для отступа используется смесь вкладок и пробелов.

Решение этой проблемы состоит в том, чтобы все строки в одном и том же файле кода Python использовали либо табуляции, либо пробелы, но не обе. Для приведенных выше блоков кода исправление будет состоять в том, чтобы удалить вкладку и заменить ее на 4 пробела, которые будут печатать + 'done' + после завершения цикла + for +.

Определение и вызов функций

Вы можете столкнуться с неверным синтаксисом в Python, когда вы определяете или вызываете функции. Например, вы увидите + SyntaxError +, если будете использовать точку с запятой вместо двоеточия в конце определения функции:

>>>

>>> def fun();

File "<stdin>", line 1

def fun();

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntaxТрассировка здесь очень полезна, с помощью каретки, указывающей прямо на символ проблемы. Вы можете очистить этот неверный синтаксис в Python, отключив точку с запятой для двоеточия.

Кроме того, ключевые аргументы как в определениях функций, так и в вызовах функций должны быть в правильном порядке. Аргументы ключевых слов always идут после позиционных аргументов. Отказ от использования этого порядка приведет к + SyntaxError +:

>>>

>>> def fun(a, b):

... print(a, b)

...

>>> fun(a=1, 2)

File "<stdin>", line 1

SyntaxError: positional argument follows keyword argumentЗдесь, еще раз, сообщение об ошибке очень полезно, чтобы рассказать вам точно, что не так со строкой.

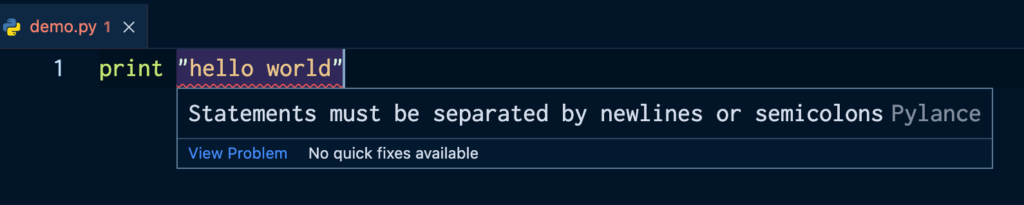

Изменение версий Python

Иногда код, который прекрасно работает в одной версии Python, ломается в более новой версии. Это связано с официальными изменениями в синтаксисе языка. Наиболее известным примером этого является оператор + print +, который перешел от ключевого слова в Python 2 к встроенной функции в Python 3:

>>>

>>> # Valid Python 2 syntax that fails in Python 3

>>> print 'hello'

File "<stdin>", line 1

print 'hello'

^

SyntaxError: Missing parentheses in call to 'print'. Did you mean print('hello')?Это один из примеров, где появляется сообщение об ошибке, сопровождающее + SyntaxError +! Он не только сообщает вам, что в вызове + print + отсутствует скобка, но также предоставляет правильный код, который поможет вам исправить оператор.

Другая проблема, с которой вы можете столкнуться, — это когда вы читаете или изучаете синтаксис, который является допустимым синтаксисом в более новой версии Python, но недопустим в той версии, в которую вы пишете. Примером этого является синтаксис f-string, которого нет в версиях Python до 3.6:

>>>

>>> # Any version of python before 3.6 including 2.7

>>> w ='world'

>>> print(f'hello, {w}')

File "<stdin>", line 1

print(f'hello, {w}')

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntaxВ версиях Python до 3.6 интерпретатор ничего не знает о синтаксисе f-строки и просто предоставляет общее сообщение «» неверный синтаксис «`. Проблема, в данном случае, в том, что код looks прекрасно работает, но он был запущен с более старой версией Python. В случае сомнений перепроверьте, какая версия Python у вас установлена!

Синтаксис Python продолжает развиваться, и в Python 3.8 появилось несколько интересных новых функций:

-

Walrus оператор (выражения присваивания)

-

F-string синтаксис для отладки

*https://docs.python.org/3.8/whatsnew/3.8.html#positional-only-parameters[Positional-only arguments]

Если вы хотите опробовать некоторые из этих новых функций, то вам нужно убедиться, что вы работаете в среде Python 3.8. В противном случае вы получите + SyntaxError +.

Python 3.8 также предоставляет новый* + SyntaxWarning + *. Вы увидите это предупреждение в ситуациях, когда синтаксис допустим, но все еще выглядит подозрительно. Примером этого может быть отсутствие запятой между двумя кортежами в списке. Это будет действительный синтаксис в версиях Python до 3.8, но код вызовет + TypeError +, потому что кортеж не может быть вызван:

>>>

>>> [(1,2)(2,3)]

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'tuple' object is not callableЭтот + TypeError + означает, что вы не можете вызывать кортеж, подобный функции, что, как думает интерпретатор Python, вы делаете.

В Python 3.8 этот код все еще вызывает + TypeError +, но теперь вы также увидите + SyntaxWarning +, который указывает, как вы можете решить проблему:

>>>

>>> [(1,2)(2,3)]

<stdin>:1: SyntaxWarning: 'tuple' object is not callable; perhaps you missed a comma?

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'tuple' object is not callableПолезное сообщение, сопровождающее новый + SyntaxWarning +, даже дает подсказку (" возможно, вы пропустили запятую? "), Чтобы указать вам правильное направление!

Заключение

В этом руководстве вы увидели, какую информацию предоставляет обратная связь + SyntaxError +. Вы также видели много распространенных примеров неправильного синтаксиса в Python и каковы решения этих проблем. Это не только ускорит ваш рабочий процесс, но и сделает вас более полезным рецензентом кода!

Когда вы пишете код, попробуйте использовать IDE, который понимает синтаксис Python и предоставляет обратную связь. Если вы поместите многие из недопустимых примеров кода Python из этого руководства в хорошую IDE, то они должны выделить проблемные строки, прежде чем вы даже сможете выполнить свой код.

Получение + SyntaxError + во время изучения Python может быть неприятным, но теперь вы знаете, как понимать сообщения трассировки и с какими формами недопустимого синтаксиса в Python вы можете столкнуться. В следующий раз, когда вы получите + SyntaxError +, у вас будет больше возможностей быстро решить проблему!

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Cool New Features in Python 3.10

Python 3.10 is out! Volunteers have been working on the new version since May 2020 to bring you a better, faster, and more secure Python. As of October 4, 2021, the first official version is available.

Each new version of Python brings a host of changes. You can read about all of them in the documentation. Here, you’ll get to learn about the coolest new features.

In this tutorial, you’ll learn about:

- Debugging with more helpful and precise error messages

- Using structural pattern matching to work with data structures

- Adding more readable and more specific type hints

- Checking the length of sequences when using

zip() - Calculating multivariable statistics

To try out the new features yourself, you need to run Python 3.10. You can get it from the Python homepage. Alternatively, you can use Docker with the latest Python image.

Better Error Messages

Python is often lauded for being a user-friendly programming language. While this is true, there are certain parts of Python that could be friendlier. Python 3.10 comes with a host of more precise and constructive error messages. In this section, you’ll see some of the newest improvements. The full list is available in the documentation.

Think back to writing your first Hello World program in Python:

# hello.py

print("Hello, World!)

Maybe you created a file, added the famous call to print(), and saved it as hello.py. You then ran the program, eager to call yourself a proper Pythonista. However, something went wrong:

$ python hello.py

File "/home/rp/hello.py", line 3

print("Hello, World!)

^

SyntaxError: EOL while scanning string literal

There was a SyntaxError in the code. EOL, what does that even mean? You went back to your code, and after a bit of staring and searching, you realized that there was a missing quotation mark at the end of your string.

One of the more impactful improvements in Python 3.10 is better and more precise error messages for many common issues. If you run your buggy Hello World in Python 3.10, you’ll get a bit more help than in earlier versions of Python:

$ python hello.py

File "/home/rp/hello.py", line 3

print("Hello, World!)

^

SyntaxError: unterminated string literal (detected at line 3)

The error message is still a bit technical, but gone is the mysterious EOL. Instead, the message tells you that you need to terminate your string! There are similar improvements to many different error messages, as you’ll see below.

A SyntaxError is an error raised when your code is parsed, before it even starts to execute. Syntax errors can be tricky to debug because the interpreter provides imprecise or sometimes even misleading error messages. The following code is missing a curly brace to terminate the dictionary:

1# unterminated_dict.py

2

3months = {

4 10: "October",

5 11: "November",

6 12: "December"

7

8print(f"{months[10]} is the tenth month")

The missing closing curly brace that should have been on line 7 is an error. If you run this code with Python 3.9 or earlier, you’ll see the following error message:

File "/home/rp/unterminated_dict.py", line 8

print(f"{months[10]} is the tenth month")

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

The error message highlights line 8, but there are no syntactical problems in line 8! If you’ve experienced your share of syntax errors in Python, you might already know that the trick is to look at the lines before the one Python complains about. In this case, you’re looking for the missing closing brace on line 7.

In Python 3.10, the same code shows a much more helpful and precise error message:

File "/home/rp/unterminated_dict.py", line 3

months = {

^

SyntaxError: '{' was never closed

This points you straight to the offending dictionary and allows you to fix the issue in no time.

There are a few other ways to mess up dictionary syntax. A typical one is forgetting a comma after one of the items:

1# missing_comma.py

2

3months = {

4 10: "October"

5 11: "November",

6 12: "December",

7}

In this code, a comma is missing at the end of line 4. Python 3.10 gives you a clear suggestion on how to fix your code:

File "/home/real_python/missing_comma.py", line 4

10: "October"

^^^^^^^^^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax. Perhaps you forgot a comma?

You can add the missing comma and have your code back up and running in no time.

Another common mistake is using the assignment operator (=) instead of the equality comparison operator (==) when you’re comparing values. Previously, this would just cause another invalid syntax message. In the newest version of Python, you get some more advice:

>>>

>>> if month = "October":

File "<stdin>", line 1

if month = "October":

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax. Maybe you meant '==' or ':=' instead of '='?

The parser suggests that you maybe meant to use a comparison operator or an assignment expression operator instead.

Take note of another nifty improvement in Python 3.10 error messages. The last two examples show how carets (^^^) highlight the whole offending expression. Previously, a single caret symbol (^) indicated just an approximate location.

The final error message improvement that you’ll play with for now is that attribute and name errors can now offer suggestions if you misspell an attribute or a name:

>>>

>>> import math

>>> math.py

AttributeError: module 'math' has no attribute 'py'. Did you mean: 'pi'?

>>> pint

NameError: name 'pint' is not defined. Did you mean: 'print'?

>>> release = "3.10"

>>> relaese

NameError: name 'relaese' is not defined. Did you mean: 'release'?

Note that the suggestions work for both built-in names and names that you define yourself, although they may not be available in all environments. If you like these kinds of suggestions, check out BetterErrorMessages, which offers similar suggestions in even more contexts.

The improvements you’ve seen in this section are just some of the many error messages that have gotten a face-lift. The new Python will be even more user-friendly than before, and hopefully, the new error messages will save you both time and frustration going forward.

Structural Pattern Matching

The biggest new feature in Python 3.10, probably both in terms of controversy and potential impact, is structural pattern matching. Its introduction has sometimes been referred to as switch ... case coming to Python, but you’ll see that structural pattern matching is much more powerful than that.

You’ll see three different examples that together highlight why this feature is called structural pattern matching and show you how you can use this new feature:

- Detecting and deconstructing different structures in your data

- Using different kinds of patterns

- Matching literal patterns

Structural pattern matching is a comprehensive addition to the Python language. To give you a taste of how you can take advantage of it in your own projects, the next three subsections will dive into some of the details. You’ll also see some links that can help you explore in even more depth if you want.

Deconstructing Data Structures

At its core, structural pattern matching is about defining patterns to which your data structures can be matched. In this section, you’ll study a practical example where you’ll work with data that are structured differently, even though the meaning is the same. You’ll define several patterns, and depending on which pattern matches your data, you’ll process your data appropriately.

This section will be a bit light on explanations of the possible patterns. Instead, it will try to give you an impression of the possibilities. The next section will step back and explain the patterns in more detail.

Time to match your first pattern! The following example uses a match ... case block to find the first name of a user by extracting it from a user data structure:

>>>

>>> user = {

... "name": {"first": "Pablo", "last": "Galindo Salgado"},

... "title": "Python 3.10 release manager",

... }

>>> match user:

... case {"name": {"first": first_name}}:

... pass

...

>>> first_name

'Pablo'

You can see structural pattern matching at work in the highlighted lines. user is a small dictionary with user information. The case line specifies a pattern that user is matched against. In this case, you’re looking for a dictionary with a "name" key whose value is a new dictionary. This nested dictionary has a key called "first". The corresponding value is bound to the variable first_name.

For a practical example, say that you’re processing user data where the underlying data model changes over time. Therefore, you need to be able to process different versions of the same data.

In the next example, you’ll use data from randomuser.me. This is a great API for generating random user data that you can use during testing and development. The API is also an example of an API that has changed over time. You can still access the old versions of the API.

You may expand the collapsed section below to see how you can use requests to obtain different versions of the user data using the API:

You can get a random user from the API using requests as follows:

# random_user.py

import requests

def get_user(version="1.3"):

"""Get random users"""

url = f"https://randomuser.me/api/{version}/?results=1"

response = requests.get(url)

if response:

return response.json()["results"][0]

get_user() gets one random user in JSON format. Note the version parameter. The structure of the returned data has changed quite a bit between earlier versions like "1.1" and the current version "1.3", but in each case, the actual user data are contained in a list inside the "results" array. The function returns the first—and only—user in this list.

At the time of writing, the latest version of the API is 1.3 and the data has the following structure:

{

"gender": "female",

"name": {

"title": "Miss",

"first": "Ilona",

"last": "Jokela"

},

"location": {

"street": {

"number": 4473,

"name": "Mannerheimintie"

},

"city": "Harjavalta",

"state": "Ostrobothnia",

"country": "Finland",

"postcode": 44879,

"coordinates": {

"latitude": "-6.0321",

"longitude": "123.2213"

},

"timezone": {

"offset": "+5:30",

"description": "Bombay, Calcutta, Madras, New Delhi"

}

},

"email": "ilona.jokela@example.com",

"login": {

"uuid": "632b7617-6312-4edf-9c24-d6334a6af52d",

"username": "brownsnake482",

"password": "biatch",

"salt": "ofk518ZW",

"md5": "6d589615ca44f6e583c85d45bf431c54",

"sha1": "cd87c931d579bdff77af96c09e0eea82d1edfc19",

"sha256": "6038ede83d4ce74116faa67fb3b1b2e6f6898e5749b57b5a0312bd46a539214a"

},

"dob": {

"date": "1957-05-20T08:36:09.083Z",

"age": 64

},

"registered": {

"date": "2006-07-30T18:39:20.050Z",

"age": 15

},

"phone": "07-369-318",

"cell": "048-284-01-59",

"id": {

"name": "HETU",

"value": "NaNNA204undefined"

},

"picture": {

"large": "https://randomuser.me/api/portraits/women/28.jpg",

"medium": "https://randomuser.me/api/portraits/med/women/28.jpg",

"thumbnail": "https://randomuser.me/api/portraits/thumb/women/28.jpg"

},

"nat": "FI"

}

One of the members that changed between different versions is "dob", the date of birth. Note that in version 1.3, this is a JSON object with two members, "date" and "age".

Compare the result above with a version 1.1 random user:

{

"gender": "female",

"name": {

"title": "miss",

"first": "ilona",

"last": "jokela"

},

"location": {

"street": "7336 myllypuronkatu",

"city": "kurikka",

"state": "central ostrobothnia",

"postcode": 53740

},

"email": "ilona.jokela@example.com",

"login": {

"username": "blackelephant837",

"password": "sand",

"salt": "yofk518Z",

"md5": "b26367ea967600d679ee3e0b9bda012f",

"sha1": "87d2910595acba5b8e8aa8b00a841bab08580e2f",

"sha256": "73bd0d205d0dc83ae184ae222ff2e9de5ea4039119a962c4f97fabd5bbfa7aca"

},

"dob": "1966-04-17 11:57:01",

"registered": "2005-08-10 10:15:01",

"phone": "04-636-931",

"cell": "048-828-40-15",

"id": {

"name": "HETU",

"value": "366-9204"

},

"picture": {

"large": "https://randomuser.me/api/portraits/women/24.jpg",

"medium": "https://randomuser.me/api/portraits/med/women/24.jpg",

"thumbnail": "https://randomuser.me/api/portraits/thumb/women/24.jpg"

},

"nat": "FI"

}

Observe that in this older format, the value of the "dob" member is a plain string.

In this example, you’ll work with the information about the date of birth (dob) for each user. The structure of these data has changed between different versions of the Random User API:

# Version 1.1

"dob": "1966-04-17 11:57:01"

# Version 1.3

"dob": {"date": "1957-05-20T08:36:09.083Z", "age": 64}

Note that in version 1.1, the date of birth is represented as a simple string, while in version 1.3, it’s a JSON object with two members: "date" and "age". Say that you want to find the age of a user. Depending on the structure of your data, you’d either need to calculate the age based on the date of birth or look up the age if it’s already available.

Traditionally, you would detect the structure of the data with an if test, maybe based on the type of the "dob" field. You can approach this differently in Python 3.10. Now, you can use structural pattern matching instead:

1# random_user.py (continued)

2

3from datetime import datetime

4

5def get_age(user):

6 """Get the age of a user"""

7 match user:

8 case {"dob": {"age": int(age)}}:

9 return age

10 case {"dob": dob}:

11 now = datetime.now()

12 dob_date = datetime.strptime(dob, "%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S")

13 return now.year - dob_date.year

The match ... case construct is new in Python 3.10 and is how you perform structural pattern matching. You start with a match statement that specifies what you want to match. In this example, that’s the user data structure.

One or several case statements follow match. Each case describes one pattern, and the indented block beneath it says what should happen if there’s a match. In this example:

-

Line 8 matches a dictionary with a

"dob"key whose value is another dictionary with an integer (int) item named"age". The nameagecaptures its value. -

Line 10 matches any dictionary with a

"dob"key. The namedobcaptures its value.

One important feature of pattern matching is that at most one pattern will be matched. Since the pattern on line 10 matches any dictionary with "dob", it’s important that the more specific pattern on line 8 comes first.

Before looking closer at the details of the patterns and how they work, try calling get_age() with different data structures to see the result:

>>>

>>> import random_user

>>> users11 = random_user.get_user(version="1.1")

>>> random_user.get_age(users11)

55

>>> users13 = random_user.get_user(version="1.3")

>>> random_user.get_age(users13)

64

Your code can calculate the age correctly for both versions of the user data, which have different dates of birth.

Look closer at those patterns. The first pattern, {"dob": {"age": int(age)}}, matches version 1.3 of the user data:

{

...

"dob": {"date": "1957-05-20T08:36:09.083Z", "age": 64},

...

}

The first pattern is a nested pattern. The outer curly braces say that a dictionary with the key "dob" is required. The corresponding value should be a dictionary. This nested dictionary must match the subpattern {"age": int(age)}. In other words, it needs to have an "age" key with an integer value. That value is bound to the name age.

The second pattern, {"dob": dob}, matches the older version 1.1 of the user data:

{

...

"dob": "1966-04-17 11:57:01",

...

}

This second pattern is a simpler pattern than the first one. Again, the curly braces indicate that it will match a dictionary. However, any dictionary with a "dob" key is matched because there are no other restrictions specified. The value of that key is bound to the name dob.

The main takeaway is that you can describe the structure of your data using mostly familiar notation. One striking change, though, is that you can use names like dob and age, which aren’t yet defined. Instead, values from your data are bound to these names when a pattern matches.

You’ve explored some of the power of structural pattern matching in this example. In the next section, you’ll dive a bit more into the details.

Using Different Kinds of Patterns

You’ve seen an example of how you can use patterns to effectively unravel complicated data structures. Now, you’ll take a step back and look at the building blocks that make up this new feature. Many things come together to make it work. In fact, there are three Python Enhancement Proposals (PEPs) that describe structural pattern matching:

- PEP 634: Specification

- PEP 635: Motivation and Rationale

- PEP 636: Tutorial

These documents give you a lot of background and detail if you’re interested in a deeper dive than what follows.

Patterns are at the center of structural pattern matching. In this section, you’ll learn about some of the different kinds of patterns that exist:

- Mapping patterns match mapping structures like dictionaries.

- Sequence patterns match sequence structures like tuples and lists.

- Capture patterns bind values to names.

- AS patterns bind the value of subpatterns to names.

- OR patterns match one of several different subpatterns.

- Wildcard patterns match anything.

- Class patterns match class structures.

- Value patterns match values stored in attributes.

- Literal patterns match literal values.

You already used several of them in the example in the previous section. In particular, you used mapping patterns to unravel data stored in dictionaries. In this section, you’ll learn more about how some of these work. All the details are available in the PEPs mentioned above.

A capture pattern is used to capture a match to a pattern and bind it to a name. Consider the following recursive function that sums a list of numbers:

1def sum_list(numbers):

2 match numbers:

3 case []:

4 return 0

5 case [first, *rest]:

6 return first + sum_list(rest)

The first case on line 3 matches the empty list and returns 0 as its sum. The second case on line 5 uses a sequence pattern with two capture patterns to match lists with one or more elements. The first element in the list is captured and bound to the name first. The second capture pattern, *rest, uses unpacking syntax to match any number of elements. rest will bind to a list containing all elements of numbers except the first one.

sum_list() calculates the sum of a list of numbers by recursively adding the first number in the list and the sum of the rest of the numbers. You can use it as follows:

>>>

>>> sum_list([4, 5, 9, 4])

22

The sum of 4 + 5 + 9 + 4 is correctly calculated to be 22. As an exercise for yourself, you can try to trace the recursive calls to sum_list() to make sure you understand how the code sums the whole list.

sum_list() handles summing up a list of numbers. Observe what happens if you try to sum anything that isn’t a list:

>>>

>>> print(sum_list("4594"))

None

>>> print(sum_list(4594))

None

Passing a string or a number to sum_list() returns None. This occurs because none of the patterns match, and the execution continues after the match block. That happens to be the end of the function, so sum_list() implicitly returns None.

Often, though, you want to be alerted about failed matches. You can add a catchall pattern as the final case that handles this by raising an error, for example. You can use the underscore (_) as a wildcard pattern that matches anything without binding it to a name. You can add some error handling to sum_list() as follows:

def sum_list(numbers):

match numbers:

case []:

return 0

case [first, *rest]:

return first + sum_list(rest)

case _:

wrong_type = numbers.__class__.__name__

raise ValueError(f"Can only sum lists, not {wrong_type!r}")

The final case will match anything that doesn’t match the first two patterns. This will raise a descriptive error, for instance, if you try to calculate sum_list(4594). This is useful when you need to alert your users that some input was not matched as expected.

Your patterns are still not foolproof, though. Consider what happens if you try to sum a list of strings:

>>>

>>> sum_list(["45", "94"])

TypeError: can only concatenate str (not "int") to str

The base case returns 0, so therefore the summing only works for types that you can add with numbers. Python doesn’t know how to add numbers and text strings together. You can restrict your pattern to only match integers using a class pattern:

def sum_list(numbers):

match numbers:

case []:

return 0

case [int(first), *rest]:

return first + sum_list(rest)

case _:

raise ValueError(f"Can only sum lists of numbers")

Adding int() around first makes sure that the pattern only matches if the value is an integer. This might be too restrictive, though. Your function should be able to sum both integers and floating-point numbers, so how can you allow this in your pattern?

To check whether at least one out of several subpatterns match, you can use an OR pattern. OR patterns consist of two or more subpatterns, and the pattern matches if at least one of the subpatterns does. You can use this to match when the first element is either of type int or type float:

def sum_list(numbers):

match numbers:

case []:

return 0

case [int(first) | float(first), *rest]:

return first + sum_list(rest)

case _:

raise ValueError(f"Can only sum lists of numbers")

You use the pipe symbol (|) to separate the subpatterns in an OR pattern. Your function now allows summing a list of floating-point numbers:

>>>

>>> sum_list([45.94, 46.17, 46.72])

138.82999999999998

There’s a lot of power and flexibility within structural pattern matching, even more than what you’ve seen so far. Some things that aren’t covered in this overview are:

- Using guards to restrict patterns

- Using AS patterns to capture the value of subpatterns

- Using class patterns to match custom enums and data classes

If you’re interested, have a look in the documentation to learn more about these features as well. In the next section, you’ll learn about literal patterns and value patterns.

Matching Literal Patterns

A literal pattern is a pattern that matches a literal object like an explicit string or number. In a sense, this is the most basic kind of pattern and allows you to emulate switch ... case statements seen in other languages. The following example matches a specific name:

def greet(name):

match name:

case "Guido":

print("Hi, Guido!")

case _:

print("Howdy, stranger!")

The first case matches the literal string "Guido". In this case, you use _ as a wildcard to print a generic greeting whenever name is not "Guido". Such literal patterns can sometimes take the place of if ... elif ... else constructs and can play the same role that switch ... case does in some other languages.

One limitation with structural pattern matching is that you can’t directly match values stored in variables. Say that you’ve defined bdfl = "Guido". A pattern like case bdfl: will not match "Guido". Instead, this will be interpreted as a capture pattern that matches anything and binds that value to bdfl, effectively overwriting the old value.

You can, however, use a value pattern to match stored values. A value pattern looks a bit like a capture pattern but uses a previously defined dotted name that holds the value that will be matched against.

You can, for example, use an enumeration to create such dotted names:

import enum

class Pythonista(str, enum.Enum):

BDFL = "Guido"

FLUFL = "Barry"

def greet(name):

match name:

case Pythonista.BDFL:

print("Hi, Guido!")

case _:

print("Howdy, stranger!")

The first case now uses a value pattern to match Pythonista.BDFL, which is "Guido". Note that you can use any dotted name in a value pattern. You could, for example, have used a regular class or a module instead of the enumeration.

To see a bigger example of how to use literal patterns, consider the game of FizzBuzz. This is a counting game where you should replace some numbers with words according to the following rules:

- You replace numbers divisible by 3 with fizz.

- You replace numbers divisible by 5 with buzz.

- You replace numbers divisible by both 3 and 5 with fizzbuzz.

FizzBuzz is sometimes used to introduce conditionals in programming education and as a screening problem in interviews. Even though a solution is quite straightforward, Joel Grus has written a full book about different ways to program the game.

A typical solution in Python will use if ... elif ... else as follows:

def fizzbuzz(number):

mod_3 = number % 3

mod_5 = number % 5

if mod_3 == 0 and mod_5 == 0:

return "fizzbuzz"

elif mod_3 == 0:

return "fizz"

elif mod_5 == 0:

return "buzz"

else:

return str(number)

The % operator calculates the modulus, which you can use to test divisibility. Namely, if a modulus b is 0 for two numbers a and b, then a is divisible by b.

In fizzbuzz(), you calculate number % 3 and number % 5, which you then use to test for divisibility with 3 and 5. Note that you must do the test for divisibility with both 3 and 5 first. If not, numbers that are divisible by both 3 and 5 will be covered by either the "fizz" or the "buzz" cases instead.

You can check that your implementation gives the expected result:

>>>

>>> fizzbuzz(3)

fizz

>>> fizzbuzz(14)

14

>>> fizzbuzz(15)

fizzbuzz

>>> fizzbuzz(92)

92

>>> fizzbuzz(65)

buzz

You can confirm for yourself that 3 is divisible by 3, 65 is divisible by 5, and 15 is divisible by both 3 and 5, while 14 and 92 aren’t divisible by either 3 or 5.

An if ... elif ... else structure where you’re comparing one or a few variables several times over is quite straightforward to rewrite using pattern matching instead. For example, you can do the following:

def fizzbuzz(number):

mod_3 = number % 3

mod_5 = number % 5

match (mod_3, mod_5):

case (0, 0):

return "fizzbuzz"

case (0, _):

return "fizz"

case (_, 0):

return "buzz"

case _:

return str(number)

You match on both mod_3 and mod_5. Each case pattern then matches either the literal number 0 or the wildcard _ on the corresponding values.

Compare and contrast this version with the previous one. Note how the pattern (0, 0) corresponds to the test mod_3 == 0 and mod_5 == 0, while (0, _) corresponds to mod_3 == 0.

As you saw earlier, you can use an OR pattern to match on several different patterns. For example, since mod_3 can only take the values 0, 1, and 2, you can replace case (_, 0) with case (1, 0) | (2, 0). Remember that (0, 0) has already been covered.

The Python core developers have consciously chosen not to include switch ... case statements in the language earlier. However, there are some third-party packages that do, like switchlang, which adds a switch command that also works on earlier versions of Python.

Type Unions, Aliases, and Guards

Reliably, each new Python release brings some improvements to the static typing system. Python 3.10 is no exception. In fact, four different PEPs about typing accompany this new release:

- PEP 604: Allow writing union types as

X | Y - PEP 613: Explicit Type Aliases

- PEP 647: User-Defined Type Guards

- PEP 612: Parameter Specification Variables

PEP 604 will probably be the most widely used of these changes going forward, but you’ll get a brief overview of each of the features in this section.

You can use union types to declare that a variable can have one of several different types. For example, you’ve been able to type hint a function calculating the mean of a list of numbers, floats, or integers as follows:

from typing import List, Union

def mean(numbers: List[Union[float, int]]) -> float:

return sum(numbers) / len(numbers)