The try...catch statement is comprised of a try block and either a catch block, a finally block, or both. The code in the try block is executed first, and if it throws an exception, the code in the catch block will be executed. The code in the finally block will always be executed before control flow exits the entire construct.

Try it

Syntax

try {

tryStatements

} catch (exceptionVar) {

catchStatements

} finally {

finallyStatements

}

tryStatements-

The statements to be executed.

catchStatements-

Statement that is executed if an exception is thrown in the

try-block. exceptionVarOptional-

An optional identifier to hold the caught exception for the associated

catchblock. If thecatchblock does not utilize the exception’s value, you can omit theexceptionVarand its surrounding parentheses, ascatch {...}. finallyStatements-

Statements that are executed before control flow exits the

try...catch...finallyconstruct. These statements execute regardless of whether an exception was thrown or caught.

Description

The try statement always starts with a try block. Then, a catch block or a finally block must be present. It’s also possible to have both catch and finally blocks. This gives us three forms for the try statement:

try...catchtry...finallytry...catch...finally

Unlike other constructs such as if or for, the try, catch, and finally blocks must be blocks, instead of single statements.

try doSomething(); // SyntaxError

catch (e) console.log(e);

A catch-block contains statements that specify what to do if an exception

is thrown in the try-block. If any statement within the

try-block (or in a function called from within the try-block)

throws an exception, control is immediately shifted to the catch-block. If

no exception is thrown in the try-block, the catch-block is

skipped.

The finally block will always execute before control flow exits the try...catch...finally construct. It always executes, regardless of whether an exception was thrown or caught.

You can nest one or more try statements. If an inner try

statement does not have a catch-block, the enclosing try

statement’s catch-block is used instead.

You can also use the try statement to handle JavaScript exceptions. See

the JavaScript Guide for more information

on JavaScript exceptions.

Unconditional catch-block

When a catch-block is used, the catch-block is executed when

any exception is thrown from within the try-block. For example, when the

exception occurs in the following code, control transfers to the

catch-block.

try {

throw "myException"; // generates an exception

} catch (e) {

// statements to handle any exceptions

logMyErrors(e); // pass exception object to error handler

}

The catch-block specifies an identifier (e in the example

above) that holds the value of the exception; this value is only available in the

scope of the catch-block.

Conditional catch-blocks

You can create «Conditional catch-blocks» by combining

try...catch blocks with if...else if...else structures, like

this:

try {

myroutine(); // may throw three types of exceptions

} catch (e) {

if (e instanceof TypeError) {

// statements to handle TypeError exceptions

} else if (e instanceof RangeError) {

// statements to handle RangeError exceptions

} else if (e instanceof EvalError) {

// statements to handle EvalError exceptions

} else {

// statements to handle any unspecified exceptions

logMyErrors(e); // pass exception object to error handler

}

}

A common use case for this is to only catch (and silence) a small subset of expected

errors, and then re-throw the error in other cases:

try {

myRoutine();

} catch (e) {

if (e instanceof RangeError) {

// statements to handle this very common expected error

} else {

throw e; // re-throw the error unchanged

}

}

The exception identifier

When an exception is thrown in the try-block,

exception_var (i.e., the e in catch (e))

holds the exception value. You can use this identifier to get information about the

exception that was thrown. This identifier is only available in the

catch-block’s scope. If you don’t need the

exception value, it could be omitted.

function isValidJSON(text) {

try {

JSON.parse(text);

return true;

} catch {

return false;

}

}

The finally-block

The finally block contains statements to execute after the try block and catch block(s) execute, but before the statements following the try...catch...finally block. Control flow will always enter the finally block, which can proceed in one of the following ways:

- Immediately before the

tryblock finishes execution normally (and no exceptions were thrown); - Immediately before the

catchblock finishes execution normally; - Immediately before a control-flow statement (

return,throw,break,continue) is executed in thetryblock orcatchblock.

If an exception is thrown from the try block, even when there’s no catch block to handle the exception, the finally block still executes, in which case the exception is still thrown immediately after the finally block finishes executing.

The following example shows one use case for the finally-block. The code

opens a file and then executes statements that use the file; the

finally-block makes sure the file always closes after it is used even if an

exception was thrown.

openMyFile();

try {

// tie up a resource

writeMyFile(theData);

} finally {

closeMyFile(); // always close the resource

}

Control flow statements (return, throw, break, continue) in the finally block will «mask» any completion value of the try block or catch block. In this example, the try block tries to return 1, but before returning, the control flow is yielded to the finally block first, so the finally block’s return value is returned instead.

function doIt() {

try {

return 1;

} finally {

return 2;

}

}

doIt(); // returns 2

It is generally a bad idea to have control flow statements in the finally block. Only use it for cleanup code.

Examples

Nested try-blocks

First, let’s see what happens with this:

try {

try {

throw new Error("oops");

} finally {

console.log("finally");

}

} catch (ex) {

console.error("outer", ex.message);

}

// Logs:

// "finally"

// "outer" "oops"

Now, if we already caught the exception in the inner try-block by adding a

catch-block:

try {

try {

throw new Error("oops");

} catch (ex) {

console.error("inner", ex.message);

} finally {

console.log("finally");

}

} catch (ex) {

console.error("outer", ex.message);

}

// Logs:

// "inner" "oops"

// "finally"

And now, let’s rethrow the error.

try {

try {

throw new Error("oops");

} catch (ex) {

console.error("inner", ex.message);

throw ex;

} finally {

console.log("finally");

}

} catch (ex) {

console.error("outer", ex.message);

}

// Logs:

// "inner" "oops"

// "finally"

// "outer" "oops"

Any given exception will be caught only once by the nearest enclosing

catch-block unless it is rethrown. Of course, any new exceptions raised in

the «inner» block (because the code in catch-block may do something that

throws), will be caught by the «outer» block.

Returning from a finally-block

If the finally-block returns a value, this value becomes the return value

of the entire try-catch-finally statement, regardless of any

return statements in the try and catch-blocks.

This includes exceptions thrown inside of the catch-block:

(() => {

try {

try {

throw new Error("oops");

} catch (ex) {

console.error("inner", ex.message);

throw ex;

} finally {

console.log("finally");

return;

}

} catch (ex) {

console.error("outer", ex.message);

}

})();

// Logs:

// "inner" "oops"

// "finally"

The outer «oops» is not thrown because of the return in the finally-block.

The same would apply to any value returned from the catch-block.

Specifications

| Specification |

|---|

| ECMAScript Language Specification # sec-try-statement |

Browser compatibility

BCD tables only load in the browser

See also

В этой статье мы познакомимся с инструкцией для обработки ошибок try...catch и throw для генерирования исключений.

Непойманные ошибки

Ошибке в коде могут возникать по разным причинам. Например, вы отправили запрос на сервер, а он дал сбой и прислал ответ, который привёл к неожиданным последствиям. Кроме этой, могут быть тысячи других, а также свои собственные.

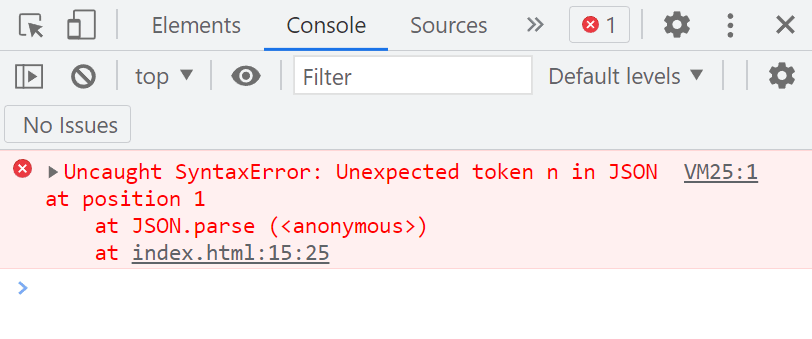

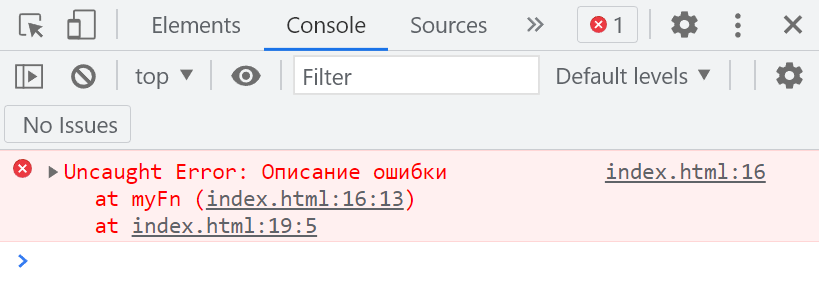

Когда возникает ошибка, выполнение кода прекращается, и эта ошибка выводится в консоль:

const json = '{name:"Александр"}';

const person = JSON.parse(json); // Uncaught SyntaxError: Unexpected token n in JSON at position 1

console.log('Это сообщение мы не увидим!');Выполнение этого примера остановится при парсинге строки JSON. В консоль будет выведена непойманная ошибка (uncaught error). Она так называется, потому что мы её не поймали (не обработали). Дальше код выполняться не будет и сообщение, которые мы выводим с помощью console.log() не отобразится.

Обработка ошибок в JavaScript осуществляется с помощью try...catch.

try...catch – это специальный синтаксис, состоящий из 2 блоков кода:

try {

// блок кода, в котором имеется вероятность возникновения ошибки

} catch(error) {

// этот блок выполняется только в случае возникновения ошибки в блоке try

}Первый блок идёт сразу после ключевого слова try. В этот блок мы помещаем часть кода, в котором есть вероятность возникновения ошибки.

Второй блок располагается за ключевым словом catch. В него помещаем код, который будет выполнен только в том случае, если в первом блоке возникнет ошибка. В круглых скобках после catch указываем параметр error. В этот параметр будет помещена ошибка, которая возникла в блоке try.

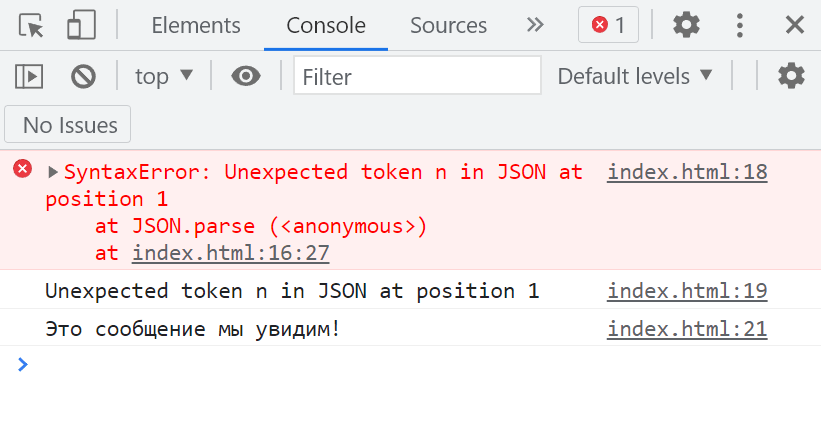

Код, приведённый выше мы обернули в try...catch, а именно ту его часть, в котором может возникнуть ошибка:

const text = '{name:"Александр"}';

try {

const person = JSON.parse(text); // Uncaught SyntaxError: Unexpected token n in JSON at position 1

} catch(error) {

console.error(error);

console.log(error.message);

}

console.log('Это сообщение мы увидим!');Здесь в блоке try произойдет ошибка, так как в данном примере мы специально присвоили переменной text некорректную строку JSON. В catch эта ошибка будет присвоена параметру error, и в нём мы будем просто выводить эту ошибку в консоль с помощью console.error(). Таким образом она будет выведена также красным цветом, но без слова Uncaught, т.к. эта ошибка была поймана.

Ошибка – это объект и у него имеются следующие свойства:

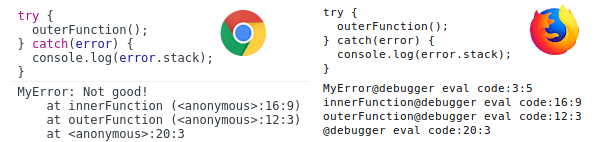

message– описание ошибки;name– тип ошибки, например, RangeError при указании значения выходящего за пределы диапазона;stack– строка стека, которая используется в целях отладки; она позволяет узнать о том, что происходило в скрипте на момент возникновения ошибки.

В этом примере мы также написали инструкцию для вывода описание ошибки error.message в консоль с помощью console.log().

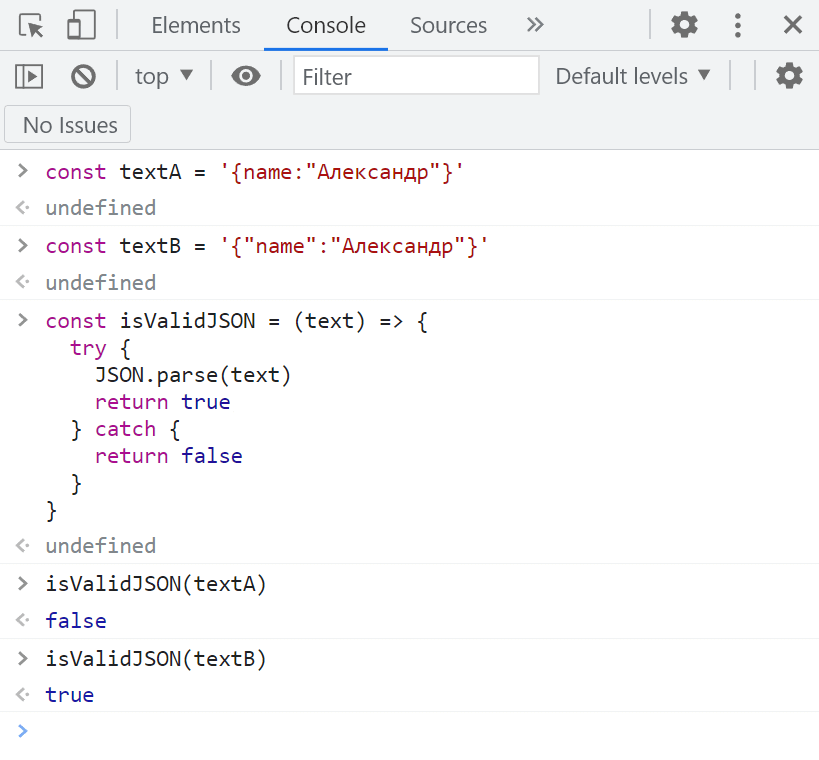

Пример функции для проверки корректности JSON:

const isValidJSON = (text) => {

try {

JSON.parse(text);

return true;

} catch {

return false;

}

}При вызове функции, сначала будет выполняться инструкция JSON.parse(text). Если ошибки не возникнет, то возвратится значение true. В противном случае, интерпретатор перейдёт в секцию catch. В итоге будет возвращено false. Кстати здесь catch записан без указания круглых скобок и параметра внутри них. Эта возможность была добавлена в язык, начиная с версии ECMAScript 2019.

Блок «finally»

В JavaScript возможны три формы инструкции try:

try...catchtry...finallytry...catch...finally

Блок finally выполняется всегда, независимо от того возникли ошибки в try или нет. Он выполняется после try, если ошибок не было, и после catch, если ошибки были. Секция finally не имеет параметров.

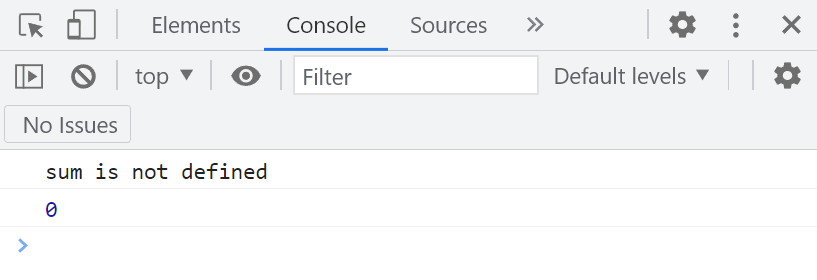

Пример с использованием finally:

let result = 0;

try {

result = sum(10, 20);

console.log('Это сообщение мы не увидим!');

} catch(error) {

console.log(error.message);

} finally {

console.log(result);

}В этом примере произойдет ошибка в секции try, так как sum нигде не определена. После возникновения ошибки интерпретатор перейдём в catch. Здесь с помощью метода console.log() сообщение об ошибке будет выведено в консоль. Затем выполнится инструкция, находящаяся в блоке finally.

В JavaScript имеется также конструкция без catch:

try {

// ...

} finally {

// завершаем какие-то действия

}Инструкция throw

В JavaScript имеется инструкция throw, которая позволяет генерировать ошибку.

Синтаксис инструкции throw:

throw expression;Как правило, в качестве выражения обычно используют встроенный основной класс для ошибок Error или более конкретный, например: RangeError, ReferenceError, SyntaxError, TypeError, URIError или другой.

Создаём новый объект Error и выбрасываем его в качестве исключения:

throw new Error('Какое-то описание ошибки');Пример генерирования синтаксической ошибки:

throw new SyntaxError('Описание ошибки');В качестве выражения можно использовать не только объект ошибки, но и строки, числа, логические значения и другие величины. Но делать это не рекомендуется:

throw 'Значение не является числом';При обнаружении оператора throw выполнение кода прекращается, и ошибка выбрасывается в консоль.

Например, создадим функцию, которая будет просто выбрасывать новую ошибку:

// создаём стрелочную функцию и присваиваем её переменной myFn

const myFn = () => {

throw new Error('Описание ошибки');

}

// вызываем функцию

myFn();

console.log('Это сообщение мы не увидим в консоли!');Для обработки ошибки обернём вызов функции в try...catch:

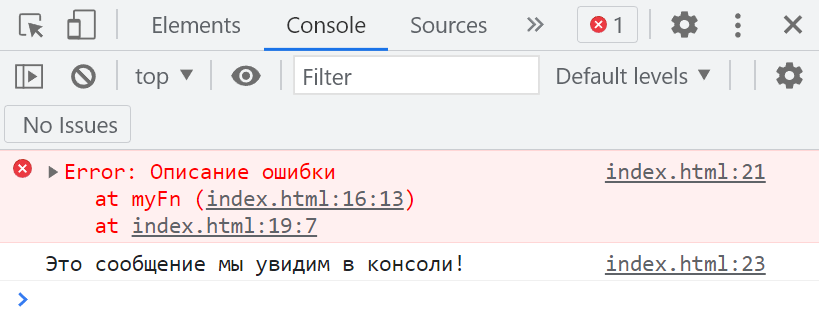

const myFn = () => {

throw new Error('Описание ошибки');

}

try {

myFn();

} catch(error) {

console.error(error);

}

console.log('Это сообщение мы увидим в консоли!');В этом примере вы увидите в консоли ошибку и дальше сообщение, которые мы выводим с помощью console.log(). То есть выполнение кода продолжится.

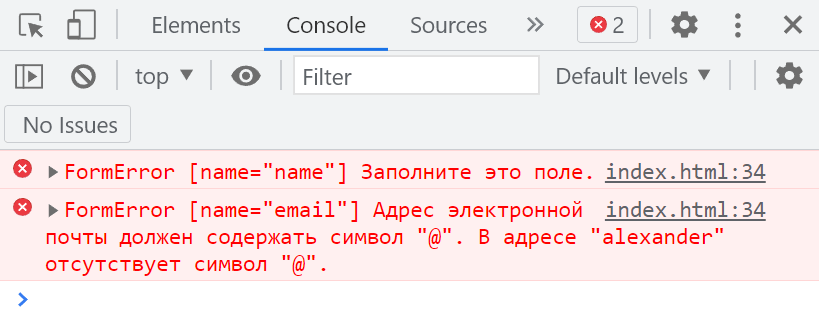

Кроме встроенных классов ошибок можно создать свои собственные, например, путем расширения Error:

class FormError extends Error {

constructor(message) {

super(message);

this.name = 'FormError';

}

}Использование своего класса FormError для отображение ошибок формы:

<form novalidate>

<input type="text" name="name" required>

<input type="email" name="email" required>

<button type="submit">Отправить</button>

</form>

<script>

class FormError extends Error {

constructor(message) {

super(message);

this.name = 'FormError';

}

}

const elForm = document.querySelector('form');

elForm.onsubmit = (e) => {

e.preventDefault();

elForm.querySelectorAll('input').forEach((el) => {

if (!el.checkValidity()) {

try {

throw new FormError(`[name="${el.name}"] ${el.validationMessage}`);

} catch(error) {

console.error(`${error.name} ${error.message}`);

}

}

});

}

</script>Глобальная ловля ошибок

Возникновение ошибок, которые мы никак не обрабатываем с помощью try, можно очень просто перехватить посредством window.onerror:

window.onerror = function(message, source, lineno, colno, error) {

// ...

}Это анонимное функциональное выражение будет вызываться каждый раз при возникновении непойманной ошибки. Ей передаются аргументы, которые мы будем получать с помощью следующих параметров:

message— строка, содержащее сообщение об ошибке;source— URL-адрес скрипта или документа, в котором произошла ошибка;linenoиcolno— соответственно номер строки и столбца, в которой произошла ошибка;error— объект ошибки илиnull, если соответствующий объект ошибки недоступен;

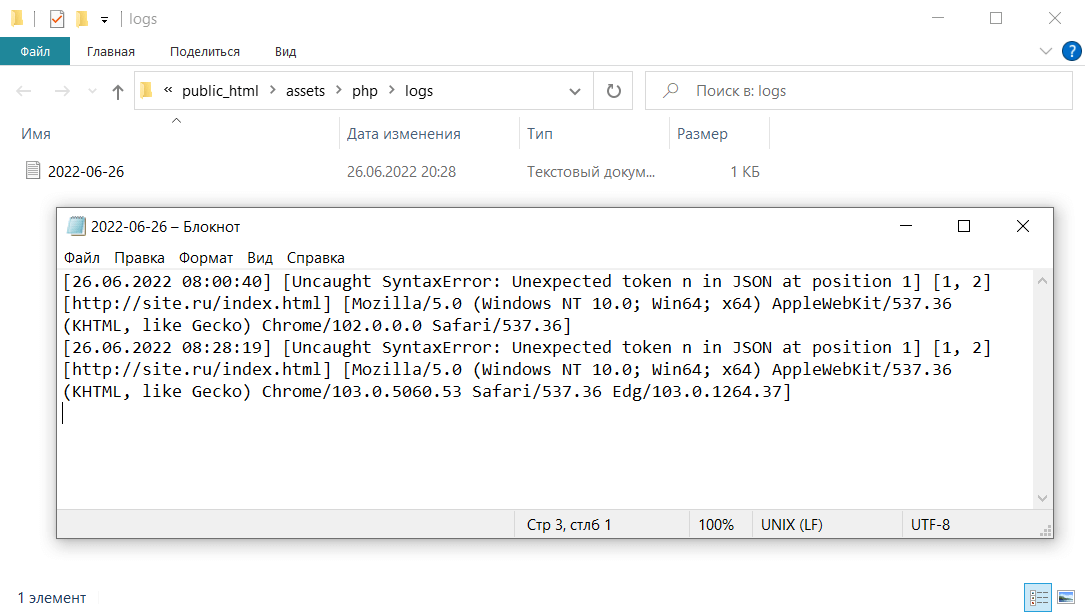

Передача ошибок на сервер

Что делать с этими ошибками? Их, например, можно передавать на сервер для того чтобы позже можно было проанализировать эти ошибки и принять меры по их устранению.

Пример кода для отправки ошибок, возникающих в браузере на сервер через AJAX с использованием fetch:

window.onerror = (message, source, lineno, colno) => {

const err = { message, source, lineno, colno };

fetch('/assets/php/error-log.php', {

method: 'post',

body: JSON.stringify(err)

});

}На сервере, если, например, сайт на PHP, можно написать такой простенький скрипт:

<?php

define('LOG_FILE', 'logs/' . date('Y-m-d') . '.log');

$json = file_get_contents('php://input');

$data = json_decode($json, true);

try {

error_log('[' . date('d.m.Y h:i:s') . '] [' . $data['message'] . '] [' . $data['lineno'] . ', ' . $data['colno'] . '] [' . $data['source'] . '] [' . $_SERVER['HTTP_USER_AGENT'] . ']' . PHP_EOL, 3, LOG_FILE);

} catch(Exception $e) {

$message = implode('; ', $data);

error_log('[' . date('d.m.Y h:i:s') . '] [' . $message . '] [' . $_SERVER['HTTP_USER_AGENT'] . ']' . PHP_EOL, 3, LOG_FILE);

}Его следует сохранить в файл /assets/php/error-log.php, а также в этом каталоге создать папку logs для сохранения в ней логов.

В результате когда на клиенте, то есть в браузере будет возникать JavaScript ошибки, они будут сохраняться на сервер в файл следующим образом:

Обработка ошибок, «try..catch»

Неважно, насколько мы хороши в программировании, иногда наши скрипты содержат ошибки. Они могут возникать из-за наших промахов, неожиданного ввода пользователя, неправильного ответа сервера и по тысяче других причин.

Обычно скрипт в случае ошибки «падает» (сразу же останавливается), с выводом ошибки в консоль.

Но есть синтаксическая конструкция try..catch, которая позволяет «ловить» ошибки и вместо падения делать что-то более осмысленное.

Синтаксис «try..catch»

Конструкция try..catch состоит из двух основных блоков: try, и затем catch:

try { // код... } catch (err) { // обработка ошибки }

Работает она так:

- Сначала выполняется код внутри блока

try {...}. - Если в нём нет ошибок, то блок

catch(err)игнорируется: выполнение доходит до концаtryи потом далее, полностью пропускаяcatch. - Если же в нём возникает ошибка, то выполнение

tryпрерывается, и поток управления переходит в началоcatch(err). Переменнаяerr(можно использовать любое имя) содержит объект ошибки с подробной информацией о произошедшем.

Таким образом, при ошибке в блоке try {…} скрипт не «падает», и мы получаем возможность обработать ошибку внутри catch.

Давайте рассмотрим примеры.

-

Пример без ошибок: выведет

alert(1)и(2):try { alert('Начало блока try'); // *!*(1) <--*/!* // ...код без ошибок alert('Конец блока try'); // *!*(2) <--*/!* } catch(err) { alert('Catch игнорируется, так как нет ошибок'); // (3) }

-

Пример с ошибками: выведет

(1)и(3):try { alert('Начало блока try'); // *!*(1) <--*/!* *!* lalala; // ошибка, переменная не определена! */!* alert('Конец блока try (никогда не выполнится)'); // (2) } catch(err) { alert(`Возникла ошибка!`); // *!*(3) <--*/!* }

««warn header=»try..catch работает только для ошибок, возникающих во время выполнения кода»

Чтобы `try..catch` работал, код должен быть выполнимым. Другими словами, это должен быть корректный JavaScript-код.

Он не сработает, если код синтаксически неверен, например, содержит несовпадающее количество фигурных скобок:

try { {{{{{{{{{{{{ } catch(e) { alert("Движок не может понять этот код, он некорректен"); }

JavaScript-движок сначала читает код, а затем исполняет его. Ошибки, которые возникают во время фазы чтения, называются ошибками парсинга. Их нельзя обработать (изнутри этого кода), потому что движок не понимает код.

Таким образом, try..catch может обрабатывать только ошибки, которые возникают в корректном коде. Такие ошибки называют «ошибками во время выполнения», а иногда «исключениями».

````warn header="`try..catch` работает синхронно"

Исключение, которое произойдёт в коде, запланированном "на будущее", например в `setTimeout`, `try..catch` не поймает:

```js run

try {

setTimeout(function() {

noSuchVariable; // скрипт упадёт тут

}, 1000);

} catch (e) {

alert( "не сработает" );

}

```

Это потому, что функция выполняется позже, когда движок уже покинул конструкцию `try..catch`.

Чтобы поймать исключение внутри запланированной функции, `try..catch` должен находиться внутри самой этой функции:

```js run

setTimeout(function() {

try {

noSuchVariable; // try..catch обрабатывает ошибку!

} catch {

alert( "ошибка поймана!" );

}

}, 1000);

```

Объект ошибки

Когда возникает ошибка, JavaScript генерирует объект, содержащий её детали. Затем этот объект передаётся как аргумент в блок catch:

try { // ... } catch(err) { // <-- объект ошибки, можно использовать другое название вместо err // ... }

Для всех встроенных ошибок этот объект имеет два основных свойства:

name

: Имя ошибки. Например, для неопределённой переменной это "ReferenceError".

message

: Текстовое сообщение о деталях ошибки.

В большинстве окружений доступны и другие, нестандартные свойства. Одно из самых широко используемых и поддерживаемых — это:

stack

: Текущий стек вызова: строка, содержащая информацию о последовательности вложенных вызовов, которые привели к ошибке. Используется в целях отладки.

Например:

try { *!* lalala; // ошибка, переменная не определена! */!* } catch(err) { alert(err.name); // ReferenceError alert(err.message); // lalala is not defined alert(err.stack); // ReferenceError: lalala is not defined at (...стек вызовов) // Можем также просто вывести ошибку целиком // Ошибка приводится к строке вида "name: message" alert(err); // ReferenceError: lalala is not defined }

Блок «catch» без переменной

[recent browser=new]

Если нам не нужны детали ошибки, в catch можно её пропустить:

try { // ... } catch { // <-- без (err) // ... }

Использование «try..catch»

Давайте рассмотрим реальные случаи использования try..catch.

Как мы уже знаем, JavaScript поддерживает метод JSON.parse(str) для чтения JSON.

Обычно он используется для декодирования данных, полученных по сети, от сервера или из другого источника.

Мы получаем их и вызываем JSON.parse вот так:

let json = '{"name":"John", "age": 30}'; // данные с сервера *!* let user = JSON.parse(json); // преобразовали текстовое представление в JS-объект */!* // теперь user - объект со свойствами из строки alert( user.name ); // John alert( user.age ); // 30

Вы можете найти более детальную информацию о JSON в главе info:json.

Если json некорректен, JSON.parse генерирует ошибку, то есть скрипт «падает».

Устроит ли нас такое поведение? Конечно нет!

Получается, что если вдруг что-то не так с данными, то посетитель никогда (если, конечно, не откроет консоль) об этом не узнает. А люди очень не любят, когда что-то «просто падает» без всякого сообщения об ошибке.

Давайте используем try..catch для обработки ошибки:

let json = "{ некорректный JSON }"; try { *!* let user = JSON.parse(json); // <-- тут возникает ошибка... */!* alert( user.name ); // не сработает } catch (e) { *!* // ...выполнение прыгает сюда alert( "Извините, в данных ошибка, мы попробуем получить их ещё раз." ); alert( e.name ); alert( e.message ); */!* }

Здесь мы используем блок catch только для вывода сообщения, но мы также можем сделать гораздо больше: отправить новый сетевой запрос, предложить посетителю альтернативный способ, отослать информацию об ошибке на сервер для логирования, … Всё лучше, чем просто «падение».

Генерация собственных ошибок

Что если json синтаксически корректен, но не содержит необходимого свойства name?

Например, так:

let json = '{ "age": 30 }'; // данные неполны try { let user = JSON.parse(json); // <-- выполнится без ошибок *!* alert( user.name ); // нет свойства name! */!* } catch (e) { alert( "не выполнится" ); }

Здесь JSON.parse выполнится без ошибок, но на самом деле отсутствие свойства name для нас ошибка.

Для того, чтобы унифицировать обработку ошибок, мы воспользуемся оператором throw.

Оператор «throw»

Оператор throw генерирует ошибку.

Синтаксис:

Технически в качестве объекта ошибки можно передать что угодно. Это может быть даже примитив, число или строка, но всё же лучше, чтобы это был объект, желательно со свойствами name и message (для совместимости со встроенными ошибками).

В JavaScript есть множество встроенных конструкторов для стандартных ошибок: Error, SyntaxError, ReferenceError, TypeError и другие. Можно использовать и их для создания объектов ошибки.

Их синтаксис:

let error = new Error(message); // или let error = new SyntaxError(message); let error = new ReferenceError(message); // ...

Для встроенных ошибок (не для любых объектов, только для ошибок), свойство name — это в точности имя конструктора. А свойство message берётся из аргумента.

Например:

let error = new Error(" Ого, ошибка! o_O"); alert(error.name); // Error alert(error.message); // Ого, ошибка! o_O

Давайте посмотрим, какую ошибку генерирует JSON.parse:

try { JSON.parse("{ bad json o_O }"); } catch(e) { *!* alert(e.name); // SyntaxError */!* alert(e.message); // Unexpected token b in JSON at position 2 }

Как мы видим, это SyntaxError.

В нашем случае отсутствие свойства name — это ошибка, ведь пользователи должны иметь имена.

Сгенерируем её:

let json = '{ "age": 30 }'; // данные неполны try { let user = JSON.parse(json); // <-- выполнится без ошибок if (!user.name) { *!* throw new SyntaxError("Данные неполны: нет имени"); // (*) */!* } alert( user.name ); } catch(e) { alert( "JSON Error: " + e.message ); // JSON Error: Данные неполны: нет имени }

В строке (*) оператор throw генерирует ошибку SyntaxError с сообщением message. Точно такого же вида, как генерирует сам JavaScript. Выполнение блока try немедленно останавливается, и поток управления прыгает в catch.

Теперь блок catch становится единственным местом для обработки всех ошибок: и для JSON.parse и для других случаев.

Проброс исключения

В примере выше мы использовали try..catch для обработки некорректных данных. А что, если в блоке try {...} возникнет другая неожиданная ошибка? Например, программная (неопределённая переменная) или какая-то ещё, а не ошибка, связанная с некорректными данными.

Пример:

let json = '{ "age": 30 }'; // данные неполны try { user = JSON.parse(json); // <-- забыл добавить "let" перед user // ... } catch(err) { alert("JSON Error: " + err); // JSON Error: ReferenceError: user is not defined // (не JSON ошибка на самом деле) }

Конечно, возможно все! Программисты совершают ошибки. Даже в утилитах с открытым исходным кодом, используемых миллионами людей на протяжении десятилетий — вдруг может быть обнаружена ошибка, которая приводит к ужасным взломам.

В нашем случае try..catch предназначен для выявления ошибок, связанных с некорректными данными. Но по своей природе catch получает все свои ошибки из try. Здесь он получает неожиданную ошибку, но всё также показывает то же самое сообщение "JSON Error". Это неправильно и затрудняет отладку кода.

К счастью, мы можем выяснить, какую ошибку мы получили, например, по её свойству name:

try { user = { /*...*/ }; } catch(e) { *!* alert(e.name); // "ReferenceError" из-за неопределённой переменной */!* }

Есть простое правило:

Блок catch должен обрабатывать только те ошибки, которые ему известны, и «пробрасывать» все остальные.

Техника «проброс исключения» выглядит так:

- Блок

catchполучает все ошибки. - В блоке

catch(err) {...}мы анализируем объект ошибкиerr. - Если мы не знаем как её обработать, тогда делаем

throw err.

В коде ниже мы используем проброс исключения, catch обрабатывает только SyntaxError:

let json = '{ "age": 30 }'; // данные неполны try { let user = JSON.parse(json); if (!user.name) { throw new SyntaxError("Данные неполны: нет имени"); } *!* blabla(); // неожиданная ошибка */!* alert( user.name ); } catch(e) { *!* if (e.name == "SyntaxError") { alert( "JSON Error: " + e.message ); } else { throw e; // проброс (*) } */!* }

Ошибка в строке (*) из блока catch «выпадает наружу» и может быть поймана другой внешней конструкцией try..catch (если есть), или «убьёт» скрипт.

Таким образом, блок catch фактически обрабатывает только те ошибки, с которыми он знает, как справляться, и пропускает остальные.

Пример ниже демонстрирует, как такие ошибки могут быть пойманы с помощью ещё одного уровня try..catch:

function readData() { let json = '{ "age": 30 }'; try { // ... *!* blabla(); // ошибка! */!* } catch (e) { // ... if (e.name != 'SyntaxError') { *!* throw e; // проброс исключения (не знаю как это обработать) */!* } } } try { readData(); } catch (e) { *!* alert( "Внешний catch поймал: " + e ); // поймал! */!* }

Здесь readData знает только, как обработать SyntaxError, тогда как внешний блок try..catch знает, как обработать всё.

try..catch..finally

Подождите, это ещё не всё.

Конструкция try..catch может содержать ещё одну секцию: finally.

Если секция есть, то она выполняется в любом случае:

- после

try, если не было ошибок, - после

catch, если ошибки были.

Расширенный синтаксис выглядит следующим образом:

*!*try*/!* { ... пробуем выполнить код... } *!*catch*/!*(e) { ... обрабатываем ошибки ... } *!*finally*/!* { ... выполняем всегда ... }

Попробуйте запустить такой код:

try { alert( 'try' ); if (confirm('Сгенерировать ошибку?')) BAD_CODE(); } catch (e) { alert( 'catch' ); } finally { alert( 'finally' ); }

У кода есть два пути выполнения:

- Если вы ответите на вопрос «Сгенерировать ошибку?» утвердительно, то

try -> catch -> finally. - Если ответите отрицательно, то

try -> finally.

Секцию finally часто используют, когда мы начали что-то делать и хотим завершить это вне зависимости от того, будет ошибка или нет.

Например, мы хотим измерить время, которое занимает функция чисел Фибоначчи fib(n). Естественно, мы можем начать измерения до того, как функция начнёт выполняться и закончить после. Но что делать, если при вызове функции возникла ошибка? В частности, реализация fib(n) в коде ниже возвращает ошибку для отрицательных и для нецелых чисел.

Секция finally отлично подходит для завершения измерений несмотря ни на что.

Здесь finally гарантирует, что время будет измерено корректно в обеих ситуациях — и в случае успешного завершения fib и в случае ошибки:

let num = +prompt("Введите положительное целое число?", 35) let diff, result; function fib(n) { if (n < 0 || Math.trunc(n) != n) { throw new Error("Должно быть целое неотрицательное число"); } return n <= 1 ? n : fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2); } let start = Date.now(); try { result = fib(num); } catch (e) { result = 0; *!* } finally { diff = Date.now() - start; } */!* alert(result || "возникла ошибка"); alert( `Выполнение заняло ${diff}ms` );

Вы можете это проверить, запустив этот код и введя 35 в prompt — код завершится нормально, finally выполнится после try. А затем введите -1 — незамедлительно произойдёт ошибка, выполнение займёт 0ms. Оба измерения выполняются корректно.

Другими словами, неважно как завершилась функция: через return или throw. Секция finally срабатывает в обоих случаях.

«`smart header=»Переменные внутри try..catch..finally локальны»

Обратите внимание, что переменные `result` и `diff` в коде выше объявлены до `try..catch`.

Если переменную объявить в блоке, например, в try, то она не будет доступна после него.

````smart header="`finally` и `return`"

Блок `finally` срабатывает при *любом* выходе из `try..catch`, в том числе и `return`.

В примере ниже из `try` происходит `return`, но `finally` получает управление до того, как контроль возвращается во внешний код.

```js run

function func() {

try {

*!*

return 1;

*/!*

} catch (e) {

/* ... */

} finally {

*!*

alert( 'finally' );

*/!*

}

}

alert( func() ); // сначала срабатывает alert из finally, а затем этот код

````smart header="`try..finally`"

Конструкция `try..finally` без секции `catch` также полезна. Мы применяем её, когда не хотим здесь обрабатывать ошибки (пусть выпадут), но хотим быть уверены, что начатые процессы завершились.

```js

function func() {

// начать делать что-то, что требует завершения (например, измерения)

try {

// ...

} finally {

// завершить это, даже если все упадёт

}

}

```

В приведённом выше коде ошибка всегда выпадает наружу, потому что тут нет блока `catch`. Но `finally` отрабатывает до того, как поток управления выйдет из функции.

Глобальный catch

Информация из данной секции не является частью языка JavaScript.

Давайте представим, что произошла фатальная ошибка (программная или что-то ещё ужасное) снаружи try..catch, и скрипт упал.

Существует ли способ отреагировать на такие ситуации? Мы можем захотеть залогировать ошибку, показать что-то пользователю (обычно они не видят сообщение об ошибке) и т.д.

Такого способа нет в спецификации, но обычно окружения предоставляют его, потому что это весьма полезно. Например, в Node.js для этого есть process.on("uncaughtException"). А в браузере мы можем присвоить функцию специальному свойству window.onerror, которая будет вызвана в случае необработанной ошибки.

Синтаксис:

window.onerror = function(message, url, line, col, error) { // ... };

message

: Сообщение об ошибке.

url

: URL скрипта, в котором произошла ошибка.

line, col

: Номера строки и столбца, в которых произошла ошибка.

error

: Объект ошибки.

Пример:

<script> *!* window.onerror = function(message, url, line, col, error) { alert(`${message}n В ${line}:${col} на ${url}`); }; */!* function readData() { badFunc(); // Ой, что-то пошло не так! } readData(); </script>

Роль глобального обработчика window.onerror обычно заключается не в восстановлении выполнения скрипта — это скорее всего невозможно в случае программной ошибки, а в отправке сообщения об ошибке разработчикам.

Существуют также веб-сервисы, которые предоставляют логирование ошибок для таких случаев, такие как https://errorception.com или http://www.muscula.com.

Они работают так:

- Мы регистрируемся в сервисе и получаем небольшой JS-скрипт (или URL скрипта) от них для вставки на страницы.

- Этот JS-скрипт ставит свою функцию

window.onerror. - Когда возникает ошибка, она выполняется и отправляет сетевой запрос с информацией о ней в сервис.

- Мы можем войти в веб-интерфейс сервиса и увидеть ошибки.

Итого

Конструкция try..catch позволяет обрабатывать ошибки во время исполнения кода. Она позволяет запустить код и перехватить ошибки, которые могут в нём возникнуть.

Синтаксис:

try { // исполняем код } catch(err) { // если случилась ошибка, прыгаем сюда // err - это объект ошибки } finally { // выполняется всегда после try/catch }

Секций catch или finally может не быть, то есть более короткие конструкции try..catch и try..finally также корректны.

Объекты ошибок содержат следующие свойства:

message— понятное человеку сообщение.name— строка с именем ошибки (имя конструктора ошибки).stack(нестандартное, но хорошо поддерживается) — стек на момент ошибки.

Если объект ошибки не нужен, мы можем пропустить его, используя catch { вместо catch(err) {.

Мы можем также генерировать собственные ошибки, используя оператор throw. Аргументом throw может быть что угодно, но обычно это объект ошибки, наследуемый от встроенного класса Error. Подробнее о расширении ошибок см. в следующей главе.

Проброс исключения — это очень важный приём обработки ошибок: блок catch обычно ожидает и знает, как обработать определённый тип ошибок, поэтому он должен пробрасывать дальше ошибки, о которых он не знает.

Даже если у нас нет try..catch, большинство сред позволяют настроить «глобальный» обработчик ошибок, чтобы ловить ошибки, которые «выпадают наружу». В браузере это window.onerror.

Bugs and errors are inevitable in programming. A friend of mine calls them unknown features :).

Call them whatever you want, but I honestly believe that bugs are one of the things that make our work as programmers interesting.

I mean no matter how frustrated you might be trying to debug some code overnight, I am pretty sure you will have a good laugh when you find out that the problem was a simple comma you overlooked, or something like that. Although, an error reported by a client will bring about more of a frown than a smile.

That said, errors can be annoying and a real pain in the behind. That is why in this article, I want to explain something called try / catch in JavaScript.

What is a try/catch block in JavaScript?

A try / catch block is basically used to handle errors in JavaScript. You use this when you don’t want an error in your script to break your code.

While this might look like something you can easily do with an if statement, try/catch gives you a lot of benefits beyond what an if/else statement can do, some of which you will see below.

try{

//...

}catch(e){

//...

}A try statement lets you test a block of code for errors.

A catch statement lets you handle that error. For example:

try{

getData() // getData is not defined

}catch(e){

alert(e)

}This is basically how a try/catch is constructed. You put your code in the try block, and immediately if there is an error, JavaScript gives the catch statement control and it just does whatever you say. In this case, it alerts you to the error.

All JavaScript errors are actually objects that contain two properties: the name (for example, Error, syntaxError, and so on) and the actual error message. That is why when we alert e, we get something like ReferenceError: getData is not defined.

Like every other object in JavaScript, you can decide to access the values differently, for example e.name(ReferenceError) and e.message(getData is not defined).

But honestly this is not really different from what JavaScript will do. Although JavaScript will respect you enough to log the error in the console and not show the alert for the whole world to see :).

What, then, is the benefit of try/catch statements?

How to use try/catch statements

The throw Statement

One of the benefits of try/catch is its ability to display your own custom-created error. This is called (throw error).

In situations where you don’t want this ugly thing that JavaScript displays, you can throw your error (an exception) with the use of the throw statement. This error can be a string, boolean, or object. And if there is an error, the catch statement will display the error you throw.

let num =prompt("insert a number greater than 30 but less than 40")

try {

if(isNaN(num)) throw "Not a number (☉。☉)!"

else if (num>40) throw "Did you even read the instructions ಠ︵ಠ, less than 40"

else if (num <= 30) throw "Greater than 30 (ب_ب)"

}catch(e){

alert(e)

}This is nice, right? But we can take it a step further by actually throwing an error with the JavaScript constructor errors.

Basically JavaScript categorizes errors into six groups:

- EvalError — An error occurred in the eval function.

- RangeError — A number out of range has occurred, for example

1.toPrecision(500).toPrecisionbasically gives numbers a decimal value, for example 1.000, and a number cannot have 500 of that. - ReferenceError — Using a variable that has not been declared

- syntaxError — When evaluating a code with a syntax error

- TypeError — If you use a value that is outside the range of expected types: for example

1.toUpperCase() - URI (Uniform Resource Identifier) Error — A URIError is thrown if you use illegal characters in a URI function.

So with all this, we could easily throw an error like throw new Error("Hi there"). In this case the name of the error will be Error and the message Hi there. You could even go ahead and create your own custom error constructor, for example:

function CustomError(message){

this.value ="customError";

this.message=message;

}And you can easily use this anywhere with throw new CustomError("data is not defined").

So far we have learnt about try/catch and how it prevents our script from dying, but that actually depends. Let’s consider this example:

try{

console.log({{}})

}catch(e){

alert(e.message)

}

console.log("This should run after the logged details")But when you try it out, even with the try statement, it still does not work. This is because there are two main types of errors in JavaScript (what I described above –syntaxError and so on – are not really types of errors. You can call them examples of errors): parse-time errors and runtime errors or exceptions.

Parse-time errors are errors that occur inside the code, basically because the engine does not understand the code.

For example, from above, JavaScript does not understand what you mean by {{}}, and because of that, your try / catch has no use here (it won’t work).

On the other hand, runtime errors are errors that occur in valid code, and these are the errors that try/catch will surely find.

try{

y=x+7

} catch(e){

alert("x is not defined")

}

alert("No need to worry, try catch will handle this to prevent your code from breaking")Believe it or not, the above is valid code and the try /catch will handle the error appropriately.

The Finally statement

The finally statement acts like neutral ground, the base point or the final ground for your try/ catch block. With finally, you are basically saying no matter what happens in the try/catch (error or no error), this code in the finally statement should run. For example:

let data=prompt("name")

try{

if(data==="") throw new Error("data is empty")

else alert(`Hi ${data} how do you do today`)

} catch(e){

alert(e)

} finally {

alert("welcome to the try catch article")

}Nesting try blocks

You can also nest try blocks, but like every other nesting in JavaScript (for example if, for, and so on), it tends to get clumsy and unreadable, so I advise against it. But that is just me.

Nesting try blocks gives you the advantage of using just one catch statement for multiple try statements. Although you could also decide to write a catch statement for each try block, like this:

try {

try {

throw new Error('oops');

} catch(e){

console.log(e)

} finally {

console.log('finally');

}

} catch (ex) {

console.log('outer '+ex);

}In this case, there won’t be any error from the outer try block because nothing is wrong with it. The error comes from the inner try block, and it is already taking care of itself (it has it own catch statement). Consider this below:

try {

try {

throw new Error('inner catch error');

} finally {

console.log('finally');

}

} catch (ex) {

console.log(ex);

}This code above works a little bit differently: the error occurs in the inner try block with no catch statement but instead with a finally statement.

Note that try/catch can be written in three different ways: try...catch, try...finally, try...catch...finally), but the error is throw from this inner try.

The finally statement for this inner try will definitely work, because like we said earlier, it works no matter what happens in try/catch. But even though the outer try does not have an error, control is still given to its catch to log an error. And even better, it uses the error we created in the inner try statement because the error is coming from there.

If we were to create an error for the outer try, it would still display the inner error created, except the inner one catches its own error.

You can play around with the code below by commenting out the inner catch.

try {

try {

throw new Error('inner catch error');

} catch(e){ //comment this catch out

console.log(e)

} finally {

console.log('finally');

}

throw new Error("outer catch error")

} catch (ex) {

console.log(ex);

}The Rethrow Error

The catch statement actually catches all errors that come its way, and sometimes we might not want that. For example,

"use strict"

let x=parseInt(prompt("input a number less than 5"))

try{

y=x-10

if(y>=5) throw new Error(" y is not less than 5")

else alert(y)

}catch(e){

alert(e)

}Let’s assume for a second that the number inputted will be less than 5 (the purpose of «use strict» is to indicate that the code should be executed in «strict mode»). With strict mode, you can not, for example, use undeclared variables (source).

I want the try statement to throw an error of y is not… when the value of y is greater than 5 which is close to impossible. The error above should be for y is not less… and not y is undefined.

In situations like this, you can check for the name of the error, and if it is not what you want, rethrow it:

"use strict"

let x = parseInt(prompt("input a number less than 5"))

try{

y=x-10

if(y>=5) throw new Error(" y is not less than 5")

else alert(y)

}catch(e){

if(e instanceof ReferenceError){

throw e

}else alert(e)

}

This will simply rethrow the error for another try statement to catch or break the script here. This is useful when you want to only monitor a particular type of error and other errors that might occur as a result of negligence should break the code.

Conclusion

In this article, I have tried to explain the following concepts relating to try/catch:

- What try /catch statements are and when they work

- How to throw custom errors

- What the finally statement is and how it works

- How Nesting try / catch statements work

- How to rethrow errors

Thank you for reading. Follow me on twitter @fakoredeDami.

Learn to code for free. freeCodeCamp’s open source curriculum has helped more than 40,000 people get jobs as developers. Get started

November 12, 2018

Mistakes happen. That’s a given. According to Murphy’s law, whatever can go wrong, will go wrong. Your job, as a programmer, is to be prepared for that fact. You have a set of tools that are prepared to do precisely that. In this article, we go through them and explain how they work.

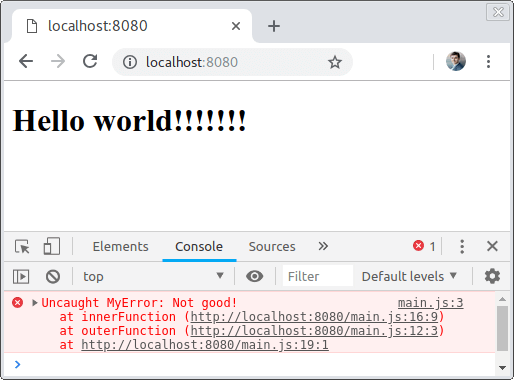

An error

When a runtime error occurs, a new error object is created and thrown. The browser presents you with the file name and the line number in which the problem occurs. Time for some evildoing:

|

cosnole.log(‘Hello world!’); |

I’ve put that code into my DevTools console and got that:

The thing that you might find striking here is the

VM164. If you look it up in the chromium source code you discover that it has no special meaning and occurs if your code is not tied to a particular file. The same thing happens if you are using eval (which you probably shouldn’t do!). Otherwise, it is the name of the file in which the error occurs.

In this example, the ReferenceError is the message name and cosnole is not defined is the message.

Since we refer here to throwing the error, how about we catch it?

If an error is thrown inside of the try block, the execution of the rest of the code is stopped. The error is caught so that you can deal with it inside of the catch block. If no exceptions are thrown in the try block, the catch is skipped.

|

try { cosnole.log(‘Hello world!’); } catch(error) { console.log(error.name); // ReferenceError console.log(error.message); // cosnole is not defined } |

Even though back in the days all declared variables used to have a functional scope (since they were declared using the var keyword, not with const and let), the catch statement is an example of block scope. The catch block receives an identifier called error in the example above. It holds the value of what was thrown in the try block. Since it is a block-scoped, after the catch block finishes executing, the error is no longer available.

If you would like to know more about variable declarations in JavaScript, check out Scopes in JavaScript. Different types of variable declarations

An important thing to keep in mind is that if you don’t provide a variable name for the error in the catch statement, an error is thrown!

Try…catch works only for runtime errors. If the error comescame from the fact that your code is not valid JavaScript, it won’t be caught.

Asynchronous code

The try…catch mechanism can’t be used to intercept errors generated in asynchronous callbacks. This fact is a common source of a misunderstanding.

|

try { setTimeout(() => { cosnole.log(‘Hello world!’); }); } catch(error) { console.log(error); } |

Uncaught ReferenceError: cosnole is not defined at setTimeout

It does not work because the callback function passed to the setTimeout is called asynchronously. By the time it runs, the surrounding try…catch blocks have been already exited. You need to put them in the callback itself.

It is a lot better if you use promises. You can catch your errors using the catch function:

|

function failingFunction(){ return new Promise(() => { cosnole.log(‘Hello world!’); }) } failingFunction() .catch(error => { console.log(error); }); |

If you would like to know more about promises and callbacks check out Explaining promises and callbacks while implementing a sorting algorithm

The try…catch blocks make a comeback to deal with asynchronous code if you use async/await

|

function failingFunction(){ return new Promise(() => { cosnole.log(‘Hello world!’); }) } (async function() { try { await failingFunction(); } catch(error){ console.log(error); } })() |

If you are interested in async/await, read Explaining async/await. Creating dummy promises

Finally

There is one more clause that you can use, and it is finally. It will execute regardless of whether an exception is thrown.

|

let isLoading = true; try { const users = await fetchUsers(); console.log(users); } catch(error){ console.log(‘Fetching users failed’, error); } finally { isLoading = false; } |

If you use the try block, you need to follow it with either the catch statement, the finally block or both. You might think that the finally statement does not serve any purpose, because you can write code just under the try…catch block. The fact is it is not always going to be executed. Examples of that are nested try-blocks.

|

try { try { cosnole.log(‘Hello world!’); // throws an error } finally { console.log(‘Finally’); } console.log(‘Will I run?’); } catch (error) { console.error(error.message); } |

In this example, the

console.log(‘Will I run?’) is not executed, because control is immediately transferred to the outer try’s catch-block. The finally is executed first even in such a case.

For more examples on how finally works, check out the code presented on MDN.

Throwing exceptions

JavaScript allows us to throw our own exceptions using the throw keyword. There is no restriction on the type of data that you throw.

|

try { throw ‘Not good!’; } catch(error) { console.log(error); } |

The Error object

The error that gets thrown when the runtime error occurs inherits from Error.prototype and consists of two properties: the name of the error and the message. The name can be one of the predefined types of errors or a custom one.

The Error.prototype.constructor accept one argument, and it is the error message. If you would like to throw a non-generic error, you can use one of the predefined ones, or define a new one! To do this, you can use ES6 classes:

|

class MyError extends Error { constructor(message) { super(message); this.name = ‘MyError’; } } throw new MyError(‘Not good!’); |

As you can see, the name of the error is now MyError. In Chrome it would be named after you class anyway, even without doing

this.name = ‘MyError’, but it might not work that way in other browsers. When an error is thrown, most browsers display a whole stack so that you can see what exactly happen:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

class MyError extends Error { constructor(message) { super(message); this.name = ‘MyError’; } toString() { return ‘The overriden error message’; } } function outerFunction() { innerFunction(); } function innerFunction() { throw new MyError(‘Not good!’); } outerFunction(); |

The Error.protototype.stack is non-standard, but it is implemented both by Chrome and Firefox.

|

try { outerFunction(); } catch(error) { console.log(error.stack); } |

Since it is not standardized, it behaves differently across browsers, so watch out!

Summary

In this article, we went through handling errors in JavaScript. It included describing how errors work in JavaScript and how to throw them. We’ve also covered the try…catch block and what purpose can the finally block serve. Aside from that, we’ve also explained the Error object in JavaScript and what are its properties, including some non-standardized ones. Hopefully, this will help you handle your errors better.

Previous article

Cross-Origin Resource Sharing. Avoiding Access-Control-Allow-Origin CORS error

Next article

Is eval evil? Just In Time (JIT) compiling