It is not clear where and when the crossbow originated, but it is believed to have appeared in China and Europe around the 7th to 5th centuries BC. In China the crossbow was one of the primary military weapons from the Warring States period until the end of the Han dynasty, when armies composed of up to 30 to 50 percent crossbowmen were not unheard of. The crossbow lost much of its popularity after the fall of the Han dynasty, likely due to the rise of the more resilient heavy cavalry during the Six Dynasties. One Tang dynasty source recommends a bow to crossbow ratio of five to one as well as the utilization of the countermarch to make up for the crossbow’s lack of speed.[1] The crossbow countermarch technique was further refined in the Song dynasty, but crossbow usage in the military continued to decline after the Mongol conquest of China.[2] Although the crossbow never regained the prominence it once had under the Han, it was never completely phased out either. Even as late as the 17th century, military theorists were still recommending it for wider military adoption, but production had already shifted in favor of firearms and traditional composite bows.[3]

In the Western world a crossbow known as the gastraphetes was described by the Greco-Roman scientist Heron of Alexandria in the 1st century AD. He believed it was the forerunner of the catapult, which places its appearance sometime prior to the 4th century BC during the Classical period.[4] Other than the gastraphetes, the only other evidence of crossbows in ancient Europe are two stone relief carvings from a Roman grave in Gaul and some vague references by Vegetius. Pictish imagery from medieval Scotland dated between the 6th and 9th centuries AD do show what appear to be crossbows, but only for hunting, and not military usage. It’s not clear how widespread crossbows were in Europe prior to the medieval period or if they were even used for warfare. The small body of evidence and the context they provide point to the fact that the ancient European crossbow was primarily a hunting tool or minor siege weapon. An assortment of other ancient European bolt throwers exist such as the ballista, but these were torsion engines and are not considered crossbows. Crossbows are not mentioned in European sources again until 947 as a French weapon during the siege of Senlis.[5] From the 11th century onward, crossbows and crossbowmen occupied a position of high status in medieval European militaries, with the exception of the English and their continued use of the longbow. During the 16th century military crossbows in Europe were superseded by gunpowder weaponry such as cannons and muskets. Hunters continued to carry crossbows for another 150 years due to its silence.[6]

There is a theory that medieval European crossbows originate from China but some differences exist between the two trigger mechanisms used in European and Chinese crossbows.[7]

Terminology[edit]

Han crossbow trigger pieces

A crossbowman or crossbow-maker is sometimes called an arbalist or arbalest.[8]

Arrow, bolt and quarrel are all suitable terms for crossbow projectiles.[8]

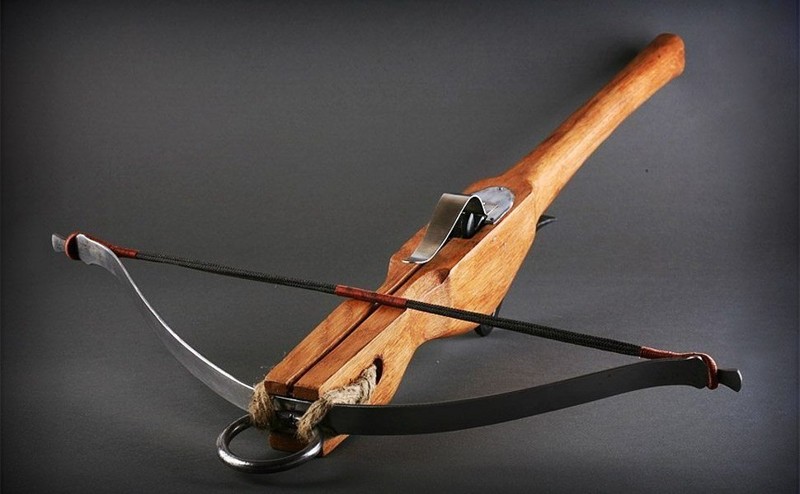

The lath, also called the prod, is the bow of the crossbow. According to W.F. Peterson, the prod came into usage in the 19th century as a result of mistranslating rodd in a 16th-century list of crossbow effects.[8]

The stock is the wooden body on which the bow is mounted, although the medieval tiller is also used.[8]

The lock refers to the release mechanism, including the string, sears, trigger lever, and housing.[8]

China[edit]

Illustration of a Ming volley fire formation using crossbows. From Cheng Zongyou 程宗猷, Jue zhang xin fa 蹶張心法 ca. 1621.

Illustration of another Ming crossbow volley fire formation. From Bi Maokang 畢懋康, Jun qi tu shuo 軍器圖說, ca. 1639.

Warring States[edit]

In terms of archaeological evidence, crossbow locks made of cast bronze have been found in China dating to around 650 BC.[8] They have also been found in Tombs 3 and 12 at Qufu, Shandong, previously the capital of Lu, and date to 6th century BC.[9][10] Bronze crossbow bolts dating from the mid-5th century BC have been found at a Chu burial site in Yutaishan, Jiangling County, Hubei Province.[11] Other early finds of crossbows were discovered in Tomb 138 at Saobatang, Hunan Province, and date to mid-4th century BC.[12][13] It’s possible that these early crossbows used spherical pellets for ammunition. A Western-Han mathematician and music theorist, Jing Fang (78-37 BC), compared the moon to the shape of a round crossbow bullet.[14] Zhuangzi also mentions crossbow bullets.[15]

The earliest Chinese documents mentioning a crossbow were texts from the 4th to 3rd centuries BC attributed to the followers of Mozi. This source refers to the use of a giant crossbow between the 6th and 5th centuries BC, corresponding to the late Spring and Autumn Period. Sun Tzu’s The Art of War (first appearance dated between 500 BC to 300 BC[16]) refers to the characteristics and use of crossbows in chapters 5 and 12 respectively,[17] and compares a drawn crossbow to ‘might.’[18]

The state of Chu favorited elite armoured crossbow units known for their endurance, and were capable of marching 160 km ‘without resting.’[19] Wei’s elite forces were capable of marching over 40 km in one day while wearing heavy armour, a large crossbow with 50 bolts, a helmet, a side sword, and three days worth of rations. Those who met these standards earned an exemption from corvée labor and taxes for their entire family.[20]

Han dynasty[edit]

The Huainanzi advises its readers not to use crossbows in marshland where the surface is soft and it is hard to arm the crossbow with the foot.[21] The Records of the Grand Historian, completed in 94 BC, mentions that Sun Bin defeated Pang Juan by ambushing him with a body of crossbowmen at the Battle of Maling.[22] The Book of Han, finished 111 AD, lists two military treatises on crossbows.[23]

In the 2nd century AD, Chen Yin gave advice on shooting with a crossbow in the Wuyue Chunqiu:

When shooting, the body should be as steady as a board, and the head mobile like an egg [on a table]; the left foot [forward] and the right foot perpendicular to it; the left hand as if leaning against a branch, the right hand as if embracing a child. Then grip the crossbow and take a sight on the enemy, hold the breath and swallow, then breathe out as soon as you have released [the arrow]; in this way you will be unperturbable. Thus after deep concentration, the two things separate, the [arrow] going, and the [bow] staying. When the right hand moves the trigger [in releasing the arrow] the left hand should not know it. One body, yet different functions [of parts], like a man and a girl well matched; such is the Dao of holding the crossbow and shooting accurately.[24]

— Chen Yin

It’s clear from surviving inventory lists in Gansu and Xinjiang that the crossbow was greatly favored by the Han dynasty. For example, in one batch of slips there are only two mentions of bows, but thirty mentions of crossbows.[21] Crossbows were mass-produced in state armories with designs improving as time went on, such as the use of a mulberry wood stock and brass; a crossbow in 1068 could pierce a tree at 140 paces.[25] Crossbows were used in numbers as large as 50,000 starting from the Qin dynasty and upwards of several hundred thousand during the Han.[26] According to one authority, the crossbow had become «nothing less than the standard weapon of the Han armies,» by the second century BC.[27] Han era carved stone images and paintings also contain images of horsemen wielding crossbows. Han soldiers were required to pull an «entry level» crossbow with a draw-weight of 76 kg to qualify as a crossbowman.[8]

| Item | Number | Government |

|---|---|---|

| Crossbow | 537,707 | 11,181 |

| Crossbow bolts | 11,458,424 | 34,265 |

| Bow | 77,521 | |

| Arrows | 1,199,316 | 511 |

-

-

Han crossbow trigger on a crossbow frame

-

Large crossbow trigger (23.49 x 17.78 cm) for mounted crossbows, Han dynasty

Later history[edit]

Korean giant naval crossbow (repeating)

Before the Han Dynasty, the trigger mechanism did not have a Guo (郭, a casing), so that the parts of the trigger mechanism were installed in the wooden frame directly. After the Han Dynasty, the original crossbow has two important design improvements. The first one is to add a bronze casing, and the other is to include a scale table with the shooting range on the trigger mechanism. The parts of the trigger mechanism installed in the bronze casing can provide higher tension than those installed on the wooden frame. As a result, its shooting range has increased greatly. Adding a scale table with the shooting range on the trigger mechanism increases the accuracy of the shooting and helps the shooter to hit the target more easily. After the Han Dynasty, the structures of the original crossbow and trigger mechanism have not changed except that the size became larger to increase the shooting range.[28]

After the Han dynasty, the crossbow lost favor until it experienced a mild resurgence during the Tang dynasty, under which the ideal expeditionary army of 20,000 included 2,200 archers and 2,000 crossbowmen.[29] Li Jing and Li Quan prescribed 20 percent of the infantry to be armed with standard crossbows, which could hit the target half the time at a distance of 345 meters, but had an effective range of 225 meters.[30]

During the Song dynasty, the government attempted to restrict the spread of military crossbows and sought ways to keep armour and crossbows out of private homes.[31] Despite the ban on certain types of crossbows, the weapon experienced an upsurge in civilian usage as both a hunting weapon and pastime. The «romantic young people from rich families, and others who had nothing particular to do» formed crossbow shooting clubs as a way to pass time.[32]

During the late Ming dynasty, no crossbows were mentioned to have been produced in the three-year period from 1619 to 1622. With 21,188,366 taels, the Ming manufactured 25,134 cannons, 8,252 small guns, 6,425 muskets, 4,090 culverins, 98,547 polearms and swords, 26,214 great «horse decapitator» swords, 42,800 bows, 1,000 great axes, 2,284,000 arrows, 180,000 fire arrows, 64,000 bow strings, and hundreds of transport carts.[33]

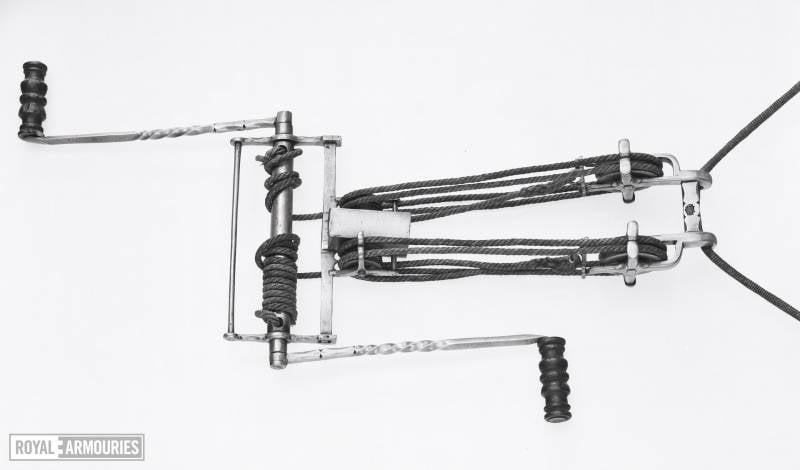

Military crossbows were armed by treading, or basically placing the feet on the bow stave and drawing it using one’s arms and back muscles. During the Song dynasty, stirrups were added for ease of drawing and to mitigate damage to the bow. Alternatively the bow could also be drawn by a belt claw attached to the waist, but this was done lying down, as was the case for all large crossbows. Winch-drawing was used for the large mounted crossbows as seen below, but evidence for its use in Chinese hand-crossbows is scant.[34]

| Army | Chariot | Crossbow | Bow | Cavalry | Assault | Maneuver | Halberd | Spear | Basic infantry | Supply | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal WS | 6,000 | 2,000 | 2,000 | 10,000 | |||||||

| Ideal WS Zhao | 1,300 | 100,000 | 13,000 | 50,000 | 164,300 | ||||||

| Anti-Xiongnu Han (97 BC) | 70,000 | 140,000 | 210,000 | ||||||||

| Later Zhao | 27,000 | 60,000 | 87,000 | ||||||||

| Former Qin | 270,000 | 250,000 | 350,000 | 870,000 | |||||||

| Basic Sui expedition | 4,000 | 8,000 | 8,000 | 20,000 | |||||||

| Basic early Tang expedition | 2,000 | 2,200 | 4,000 | 2,900 | 2,900 | 6,000 | 20,000 |

Advantages and disadvantages[edit]

Now for piercing through hard things and shooting a long distance, and when struggling to defend mountain-passes, where much noise and impetuous strength must be stemmed, there is nothing like the crossbow for success. However, as the drawing (i.e. the arming) is slow, it is difficult to cope with sudden attacks. A crossbow can only be shot off [by a single man] three times before it comes to hand-to-hand weapons. Some have therefore thought crossbows inconvenient for fighting, but truly the inconvenience lay not in the crossbow itself but in the commanders, who did not know how to make use of crossbows. All the military theorists of the Tang maintained that the crossbow had no advantage over hand-to-hand weapons, and they insisted on having long bills and great shields in the front line to repel the charge, and made the crossbowmen to carry sabres and long-hafted weapons. The result was that if the enemy adopted an open-order formation and attacked with hand-to-hand weapons, the soldiers would throw away their crossbows and have recourse to those also. A body of the rearguard was therefore detailed beforehand to go round and collect up the crossbows.[2]

The crossbow allowed archers to shoot bows of greater strength and more accurately as well due to its greater stability, but at the cost of speed.[35]

In 169 BC, Chao Cuo observed that by using the crossbow, it was possible to overcome the Xiongnu:

Of course, in mounted archery [using the short bow] the Yi and the Di are skilful, but the Chinese are good at using nu che. These carriages can be drawn up in the form of a laager which cannot be penetrated by cavalry. Moreover, the crossbows can shoot their bolts to a considerable range, and do more harm [lit. penetrate deeper] than those of the short bow. And again, if the crossbow bolts are picked up by the barbarians they have no way of making use of them. Recently the crossbow has unfortunately fallen into some neglect; we must carefully consider this… The strong crossbow [jing nu] and the [arcuballista shooting] javelins have a long range; something which the bows of the Huns can no way equal. The use of sharp weapons with long and short handles by disciplined companies of armoured soldiers in various combinations, including the drill of crossbow men alternately advancing [to shoot] and retiring [to load]; this is something which the Huns cannot even face. The troops with crossbows ride forward [cai guan shou] and shoot off all their bolts in one direction; this is something which the leather armour and wooden shields of the Huns cannot resist. Then the [horse-archers] dismount and fight forward on foot with sword and bill; this is something which the Huns do not know how to do.[36]

The Wujing Zongyao states that the crossbow used en masse was the most effective weapon against northern nomadic cavalry charges. Even if they failed, the quarrels were too short to be used as regular arrows so they couldn’t be used again by nomadic archers after the battle.[37] The crossbow’s role as an anti-cavalry weapon was later reaffirmed in Medieval Europe when Thomas the Archdeacon recommended them as the optimal weapon against the Mongols.[38] Elite crossbowmen were used to pick off targets as was the case when the Liao Dynasty general Xiao Talin was picked off by a Song crossbowman at the Battle of Shanzhou in 1004.[37]

Repeating crossbow[edit]

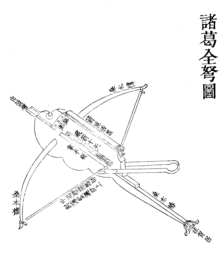

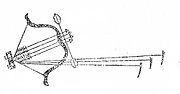

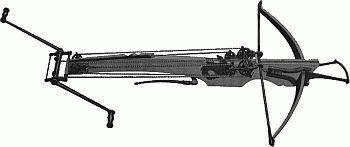

The earliest extant repeating crossbow, a double-shot repeating crossbow excavated from a tomb of the State of Chu, 4th century BC.

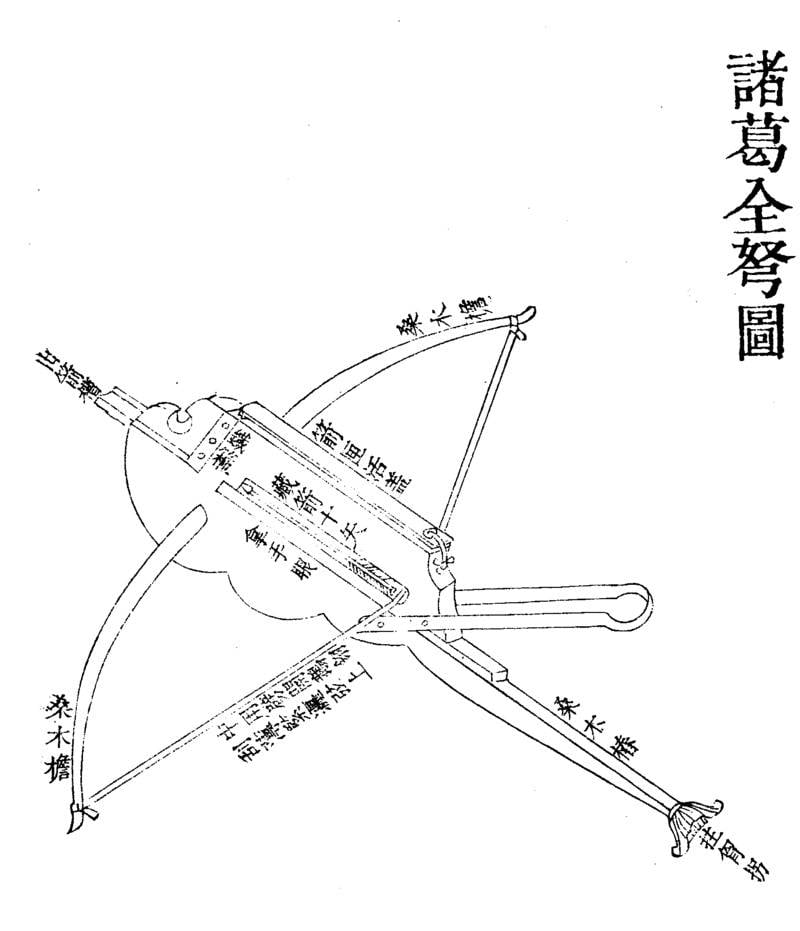

The Zhuge Nu is a handy little weapon that even the Confucian scholar or palace women can use in self-defence… It fires weakly so you have to tip the darts with poison. Once the darts are tipped with «tiger-killing poison», you can shoot it at a horse or a man and as long as you draw blood, your adversary will die immediately. The draw-back to the weapon is its very limited range.[8]

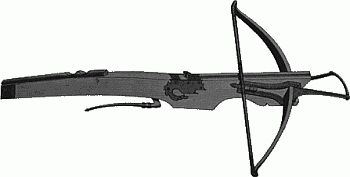

According to the Wu-Yue Chunqiu (history of the Wu-Yue War), written in the Eastern Han dynasty, the repeating crossbow was invented during the Warring States Period by a Mr. Qin from the State of Chu. This is corroborated by the earliest archaeological evidence of repeating crossbows, which was excavated from a Chu burial site at Tomb 47 at Qinjiazui, Hubei Province, and has been dated to the 4th century BC, during the Warring States Period (475 – 220 BC).[39] Unlike repeating crossbows of later eras, the ancient double shot repeating crossbow uses a pistol grip and a rear pulling mechanism for arming. The Ming repeating crossbow uses an arming mechanism which requires its user to push a rear lever upwards and downwards back and forth.[40] Although hand held repeating crossbows were generally weak and required additional poison, probably aconite, for lethality, much larger mounted versions appeared during the Ming dynasty.[8]

In 180 AD, Yang Xuan used a type of repeating crossbow powered by the movement of wheels:

…around A.D. 180 when Yang Xuan, Grand Protector of Lingling, attempted to suppress heavy rebel activity with badly inadequate forces. Yang’s solution was to load several tens of wagons with sacks of lime and mount automatic crossbows on others. Then, deploying them into a fighting formation, he exploited the wind to engulf the enemy with clouds of lime dust, blinding them, before setting rags on the tails of the horses pulling these driverless artillery wagons alight. Directed into the enemy’s heavily obscured formation, their repeating crossbows (powered by linkage with the wheels) fired repeatedly in random directions, inflicting heavy casualties. Amidst the obviously great confusion the rebels fired back furiously in self-defense, decimating each other before Yang’s forces came up and largely exterminated them.[41]

— Ralph Sawyer

Although the invention of the repeating crossbow has often been attributed to Zhuge Liang, he in fact had nothing to do with it. This misconception is based on a record attributing improvements to the multiple bolt crossbows to him.[42]

During the Ming dynasty, repeating crossbows were used on ships.[41]

Repeating crossbows continued in use until the late Qing dynasty when it became obvious they could not longer compete with firearms.[41]

Mounted crossbow[edit]

Connected double bed crossbows

Large and small Qin crossbow bolts

Large mounted crossbows known as «bed crossbows» were used as early as the Warring States period. Mozi described them as defensive weapons placed on top of the battlements. The Mohist siege crossbow was described as humongous device with frameworks taller than a man and shooting arrows with cords attached so that they could be pulled back. By the Han dynasty, crossbows were used as mobile field artillery and known as «Military Strong Carts».[41] Around the 5th century AD, multiple bows were combined to increase draw weight and length, thus creating the double and triple bow crossbows. Tang versions of this weapon are stated to have obtained a range of 1,160 yards, which is supported by Ata-Malik Juvayni on the use of similar weapons by the Mongols in 1256.[43] According Juvayni, Hulagu Khan brought with him 3,000 giant crossbows from China, for the siege of Nishapur, and a team of Chinese technicians to work a great ‘ox bow’ shooting large bolts a distance of 2,500 paces, which was used at the siege of Maymun Diz.[44] According to the Wujing Zongyao, these weapons had a range of 450 meters while other Song sources give ranges of more than double or even triple that.[45] Constructing these weapons, especially the casting of the large triggers, and their operation required the highest order of technical expertise available at the time. They were primarily used from the 8th to 11th centuries.[46]

Joseph Needham on the range of the triple-bow crossbow:

This range seems credible only with difficulty, yet strangely enough there is a confirmation of it from a Persian source, namely the historian ‘Alā’al-Dīn al-Juwainī, who wrote of what happened when one of the almost impregnable castles of the Assassins was taken by Hulagu Khan. Here, in +1256, the Chinese arcuballistae shot their projectiles 2500 (Arab) paces (1,100 yards) from a position on the top of some mountain… His actual words are: «and a kamān-i-gāu which had been constructed by Cathayan craftsmen, and which had a range of 2500 paces, was brought to bear on those fools, when no other remedy remained, and of the devil-like Heretics many soldiers were burnt by those meteoric shots». The castle in question was not Alamūt itself, but Maimūn-Diz, also in the Elburz range, and it was the strongest military base of the Assassins.[47]

— Joseph Needham

However, Juwaini’s description of the campaign against the Nizaris contains many exaggerations due to his bias against the Nizari Ismailis, and Maimun-Diz was actually not as impregnable as other nearby castles as Alamut and Lamasar, according to Peter Wiley.[48]

Multiple bolt crossbow[edit]

The multiple bolt crossbow appeared around the late 4th century BC. A passage dated to 320 BC states that it was mounted on a three-wheeled carriage and stationed on the ramparts. The crossbow was drawn using a treadle and shot 10-foot long arrows. Other drawing mechanisms such as winches and oxen were also used.[49] Later on pedal release triggers were also used.[50] Although this weapon was able to discharge multiple bolts, it was at the cost of reduced accuracy since the further the arrow was from the center of the bow string, the more off center its trajectory would be.[41] It had a maximum range of 500 yards.[51]

When Qin Shi Huang’s magicians failed to get in touch with «spirits and immortals of the marvellous islands of the Eastern Sea», they excused themselves by saying large monsters blocked their way. Qin Shi Huang personally went out with a multiple bolt crossbow to see these monsters for himself. He found no monsters but killed a big fish.[52]

In 99 BC, they were used as field artillery against attacking nomadic cavalry.[41]

Although Zhuge Liang is often credited with the invention of the repeating crossbow, this is actually due to a mistranslation confusing it with the multiple bolt crossbow. The source actually says Zhuge invented a multiple bolt crossbow that could shoot ten iron bolts simultaneously, each 20 cm long.[41]

In 759 AD, Li Quan described a type of multiple bolt crossbow capable of destroying ramparts and city towers:

The arcuballista is a crossbow of a strength of 12 dan, mounted on a wheeled frame. A winch cable pulls on an iron hook; when the winch is turned round until the string catches on the trigger the crossbow is drawn. On the upper surface of the stock there are seven grooves, the centre carrying the longest arrow. This has a point 7 in. long and 5 in. round, with iron tail fins 5 in. round, and a total length of 3 ft. To left and right there

are three arrows each steadily decreasing in size, all shot forth when the trigger is pulled. Within 700 paces whatever is hit will collapse, even solid things like ramparts and city towers.[50]— Li Quan

In 950 AD, Tao Gu described multiple crossbows connected by a single trigger:

The soldiers at the headquarters of the Xuan Wu army were exceedingly brave. They had crossbow catapults such that when one trigger was released, as many as 12 connected triggers would all go off simultaneously. They used large bolts like strings of pearls, and the range was very great. The Jin people were thoroughly frightened by these machines. Literary writers called them Ji Long Che (Rapid Dragon Carts).[41]

— Tao Gu

The weapon was considered obsolete by 1530.[50]

| Weapon | Shots per minute | Range (m) |

|---|---|---|

| Chinese crossbow | 170–450 | |

| Cavalry crossbow | 150–300 | |

| Repeating crossbow | 28–48 | 73–180 |

| Double shot repeating | 56–96 | 73–180 |

| Weapon | Crew | Draw weight (kg) | Range (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mounted multi-bolt crossbow | 365–460 | ||

| Mounted single-bow crossbow | 4–7 | 250–500 | |

| Mounted double-bow crossbow | 10 | 350–520 | |

| Mounted triple-bow crossbow | 20–100 | 950–1,200 | 460–1,060 |

-

Multi-bolt crossbows connected together

-

Crossbow firing multiple bolts

-

Crossbow battery

-

Multi-bolt ambush crossbow

-

Miniature model of a triple bed crossbow

Countermarch[edit]

Illustration of a rectangular Tang volley fire formation using crossbows. From Li Quan 李筌, Shen ji zhi di tai bai yin jing 神機制敵太白陰經, ca. 759.

The concept of continuous and concerted rotating fire, the countermarch, may have been implemented using crossbows as early as the Han dynasty,[53] but it was not until the Tang dynasty that illustrations of the countermarch appeared.[54] The 759 CE text, Tai bai yin jing (太白陰經) by Tang military official Li Quan (李筌), contains the oldest known depiction and description of the volley fire technique. The illustration shows a rectangular crossbow formation with each circle representing one man. In the front is a line labeled «shooting crossbows» (發弩) and behind that line are rows of crossbowmen, two facing right and two facing left, and they are labeled «loading crossbows» (張弩). The commander (大將軍) is situated in the middle of the formation and to his right and left are vertical rows of drummers (鼓) who coordinate the firing and reloading procedure in procession: who loaded their weapons, stepped forward to the outer ranks, shot, and then retired to reload.[55] According to Li Quan, «the classics say that the crossbow is fury. It is said that its noise is so powerful that it sounds like fury, and that’s why they named it this way,»[56] and by using the volley fire method there is no end to the sound and fury, and the enemy is unable to approach.[56] Here he is referring to the word for «crossbow» nu which is also a homophone for the word for fury, nu.[54]

The encyclopedic text known as the Tongdian by Du You from 801 CE also provides a description of the volley fire technique: «[Crossbow units] should be divided into teams that can concentrate their arrow shooting.… Those in the center of the formations should load [their bows] while those on the outside of the formations should shoot. They take turns, revolving and returning, so that once they’ve loaded they exit [i.e., proceed to the outer ranks] and once they’ve shot they enter [i.e., go within the formations]. In this way, the sound of the crossbow will not cease and the enemy will not harm us.»[54]

Illustration of a Song crossbow volley fire formation divided into firing, advancing, and reloading lines from top to bottom. From Zeng Gongliang 曾公亮, Complete Essentials for the Military Classics Preceding Volume (Wujing Zongyao qian ji 武經總要前集), ca. 1044 CE.

The Wujing Zongyao, written during the Song dynasty, notes that during the Tang period, crossbows were not used to their full effectiveness due to the fear of cavalry charges.[55] The author’s solution was to drill the soldiers to the point where rather than hide behind shieldbearers upon the approach of enemy soldier, they would «plant the feet like a firm mountain, and, unmoving at the front of the battle arrays, shoot thickly to the middle [of the enemy], and none among them will not fall down dead.»[55] The Song volley fire formation was described thus: «Those in the center of the formation should load while those on the outside of the formation should shoot, and when [the enemy gets] close, then they should shelter themselves with small shields [literally side shields, 旁牌], each taking turns and returning, so that those who are loading are within the formation. In this way the crossbows will not cease sounding.»[55] In addition to the Tang formation, the Song illustration also added a new label to the middle line of crossbowmen between the firing and reloading lines, known as the «advancing crossbows.»[57] Both Tang and Song manuals also made aware to the reader that «the accumulated arrows should be shot in a stream, which means that in front of them there must be no standing troops, and across [from them] no horizontal formations.»[57]

Regarding the method of using the crossbow, it cannot be mixed up with hand-to-hand weapons, and it is beneficial when shot from high ground facing downwards. It only needs to be used so that the men within the formation are loading while the men in the front line of the formation are shooting. As they come forward they use shields to protect their flanks. Thus each in their turn they draw their crossbows and come up; then as soon as they have shot bolts they return again into the formation. Thus the sound of the crossbows is incessant and the enemy can hardly even flee. Therefore we have the following drill – shooting rank, advancing rank, loading rank.[2]

The volley fire technique was used to great effect by the Song during the Jin-Song Wars. In the fall of 1131 the Jin commander Wuzhu (兀朮) invaded the Shaanxi region but was defeated by general Wu Jie (吳 玠) and his younger brother Wu Lin (吳璘). The History of Song elaborates on the battle in detail:

[Wu] Jie ordered his commanders to select their most vigorous bowmen and strongest crossbowmen and to divide them up for alternate shooting by turns (分番迭射). They were called the «Standing-Firm Arrow Teams» (駐隊矢), and they shot continuously without cease, as thick as rain pouring down. The enemy fell back a bit, and then [Wu Jie] attacked with cavalry from the side to cut off the [enemy’s] supply routes. [The enemy] crossed the encirclement and retreated, but [Wu Jie] set up ambushes at Shenben and waited. When the Jin troops arrived, [Wu’s] ambushers shot, and the many [enemy] were in chaos. The troops were released to attack at night and greatly defeated them. Wuzhu was struck by a flowing arrow and barely escaped with his life.[58]

After losing half his army Wuzhu escaped back to the north, only to invade again in the following year. Again, he was defeated while trying to breach a strategic pass. The History of Song states that during the battle Wu Jie’s brother Wu Lin «used the Standing-Firm Arrow Teams, who shot alternately, and the arrows fell like rain, and the dead piled up in layers, but the enemy climbed over them and kept climbing up.»[59] This passage is especially noteworthy for its mention of a special technique being utilized as it is one of the very few times that the History of Song has elaborated on a specific tactic.[59]

Southeast Asia[edit]

There is another theory pointing towards an independent Southeast Asian origin for the crossbow based on linguistic evidence:

Throughout the southeastern Asia the crossbow is still used by primitive and tribal peoples both for hunting and war, from the Assamese mountains through Burma, Siam and to the confines of Indo-China. The peoples of the northeastern Asia possess it also, both as weapon and toy, but use it mainly in the form of unattended traps; this is true of the Yakut, Tungus, and Chukchi, even of the Ainu in the east. There seems to be no way of answering the question whether it first arose among the barbaric forefathers of these Asian peoples before the rise of the Chinese culture in their midst, and then underwent its technical development only therein, or whether it spread outwards from China to all the environing peoples. The former seems the more probable hypothesis, given the further linguistic evidence in its support.[60]

Around the third century BC, King An Dương of Âu Lạc (modern-day northern Vietnam) and (modern-day southern China) commissioned a man named Cao Lỗ (or Cao Thông) to construct a crossbow and christened it «Saintly Crossbow of the Supernaturally Luminous Golden Claw» (nỏ thần), which one shot could killed 300 men.[61][62] According to historian Keith Taylor, the crossbow, along with the word for it, seems to have been introduced into China from Austroasiatic peoples in the south around the fourth century BC.[62] However, this is contradicted by crossbow locks found in ancient Chinese Zhou Dynasty tombs dating to the 600s BC. [8]

In 315 AD, Nu Wen taught the Chams how to build fortifications and use crossbows. The Chams would later give the Chinese crossbows as presents on at least one occasion.[31]

Siege crossbows were transmitted to the Chams by Zhi Yangjun, who was shipwrecked on their coast in 1172. He remained there and taught them mounted archery and how to use siege crossbows.[31][63] In 1177 crossbows were used by the Champa in their invasion and sacking of Angkor, the Khmer Empire’s capital.[64][65][66] The Khmer also had double bow crossbows mounted on elephants, which Michel JacqHergoualc’h suggest were elements of Cham mercenaries in Jayavarman VII’s army.[41]

-

Khmer elephant mounted crossbow

-

Khmer elephant mounted crossbow

Europe[edit]

Ancient[edit]

Greece[edit]

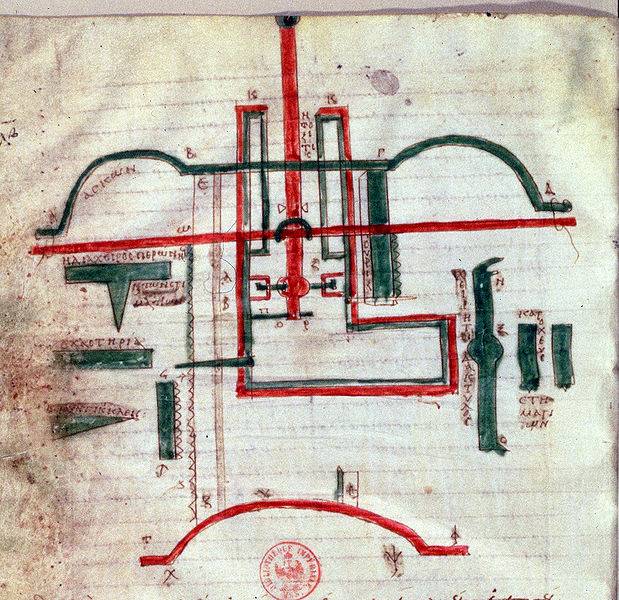

The earliest crossbow-like weapons in Europe probably emerged around the late 5th century BC when the gastraphetes, an ancient Greek crossbow, appeared. The device was described by the Greco-Roman author Heron of Alexandria of Roman Egypt in his Belopoeica («On Catapult-making»), which draws on an earlier account of Greek engineer Ctesibius (fl. 285–222 BC) of Ptolemaic Egypt. According to Heron, the gastraphetes was the forerunner of the later catapult, which places its invention some unknown time prior to 399 BC during Classical Greece.[67] The gastraphetes was a crossbow mounted on a stock divided into a lower and upper section. The lower was a case fixed to the bow while the upper was a slider which had the same dimensions as the case.[68] Meaning «belly-bow»,[68] it was called as such because the concave withdrawal rest at one end of the stock was placed against the stomach of the operator, which he could press to withdraw the slider before attaching a string to the trigger and loading the bolt; this could thus store more energy than regular Greek bows.[69] It was used in the Siege of Motya in 397 BC. This was a key Carthaginian stronghold in Sicily, as described in the 1st century AD by Heron of Alexandria in his book Belopoeica.[70]

Other arrow shooting machines such as the larger ballista and smaller Scorpio also existed starting from around 338 BC, but these are torsion catapults and not considered crossbows.[71][72][73] Arrow-shooting machines (katapeltai) are briefly mentioned by Aeneas Tacticus in his treatise on siegecraft written around 350 BC.[74] An Athenian inventory from 330 to 329 BC includes catapults bolts with heads and flights.[73] Arrow-shooting machines in action are reported from Philip II’s siege of Perinthos in Thrace in 340 BC.[75] At the same time, Greek fortifications began to feature high towers with shuttered windows in the top, presumably to house anti-personnel arrow shooters, as in Aigosthena.[76]

Rome[edit]

The late 4th century Roman author Vegetius provides the only contemporary account of ancient Roman crossbows. In his De Re Militaris, he describes arcubalistarii (crossbowmen) working together with archers and artillerymen.[8] However it is disputed if arcuballistas were even crossbows or just more torsion powered weapons. The idea that the arcuballista was a crossbow is based on the fact that Vegetius refers to it and the manuballista, which was torsion powered, separately. Therefore, if the arcuballista was not like the manuballista, it may have been a crossbow. Some suggest it was the other way around and manuballistas were crossbows.[77] The etymology is not clear and their definitions obscure. Some historians believe neither the arcuballista or manuballista were crossbows.[78] According to Vegetius, these were well known devices, and as such didn’t make the effort to describe them in depth.[79]

On the textual side, there is almost nothing but passing references in the military historian Vegetius (fl. + 386) to ‘manuballistae’ and ‘arcuballistae’ which he said he must decline to describe as they were so well known. His decision was highly regrettable, as no other author of the time makes any mention of them at all. Perhaps the best supposition is that the crossbow was primarily known in late European antiquity as a hunting weapon, and received only local use in certain units of the armies of Theodosius I, with

which Vegetius happened to be acquainted.[79]— Joseph Needham

To date, the only contemporary accounts of the arcuballista – the Roman crossbow – appear in the pages of De Re Militaris, written by Vegetius in the late 4th century AD. Drawing on a miscellany of earlier sources, Vegetius makes frustratingly vague references. He writes at one stage about crossbowmen lining up with other artillerymen (using torsion machines) in line of battle and at another about both sagittarii (regular archers) and arcuballistarii (crossbowmen) working together on siege towers to clear the ramparts of defenders. These are flickering glimpses, however; he gives little indication of the extent to which the arcuballista was used in warfare, or of the numbers of troops in a legion who might have been armed with it.[8]

— Mike Loades

Arrian’s earlier Ars Tactica, written around 136 AD, does mention ‘missiles shot not from a bow but from a machine’ and that this machine was used on horseback while in full gallop. It’s presumed that this was a crossbow.[8]

The only pictorial evidence of Roman arcuballistas comes from sculptural reliefs in Roman Gaul depicting them in hunting scenes. The draw-length of the crossbow depicted is longer than later medieval crossbows and more similar to Greek and Chinese crossbows, but it’s not clear what kind of release mechanism they used. Archaeological evidence suggests they were based on the rolling nut mechanism of medieval Europe.[8]

-

-

Pictish depiction of a hunting crossbow in the bottom right.

-

Gallo-Roman crossbow

Medieval[edit]

Depiction of a crossbow at the Battle of Crécy, image created in the 15th century

References to the crossbow are basically nonexistent in Europe from the 5th century until the 10th century. It’s argued that the term solenarion, found in the Strategikon of Maurice, refers to a crossbow. This is disputed by other historians who interpret «the device in question as an arrow guide.»[80] There is however a depiction of a crossbow as a hunting weapon on four Pictish stones from early medieval Scotland (6th to 9th centuries): St. Vigeans no. 1, Glenferness, Shandwick, and Meigle.[81]

The crossbow reappeared again in 947 as a French weapon during the siege of Senlis and again in 984 at the siege of Verdun.[82] They were used at the battle of Hastings in 1066 and had by the 12th century become a common battlefield weapon.[83] The earliest remains of a European crossbow to date were found at Lake Paladru and has been dated to the 11th century.[8]

Crossbows are not mentioned in Byzantine sources until the 11th century. Some believe that the toxoballistra found in Middle Byzantine sources refer to a crossbow, but the evidence is inconclusive.[84] According to Anna Komnene (1083–1153), the crossbow was a new weapon associated with barbarians and was not known to the Greeks:

This cross-bow is a bow of the barbarians quite unknown to the Greeks; and it is not stretched by the right hand pulling the string whilst the left pulls the bow in a contrary direction, but he who stretches this warlike and very far-shooting weapon must lie, one might say, almost on his back and apply both feet strongly against the semi-circle of the bow and with his two hands pull the string with all his might in the contrary direction. In the middle of the string is a socket, a cylindrical kind of cup fitted to the string itself, and about as long as an arrow of considerable size which reaches from the string to the very middle of the bow; and through this arrows of many sorts are shot out. The arrows used with this bow are very short in length, but very thick, fitted in front with a very heavy iron tip. And in discharging them the string shoots them out with enormous violence and force, and whatever these darts chance to hit, they do not fall back, but they pierce through a shield, then cut through a heavy iron corselet and wing their way through and out at the other side. So violent and ineluctable is the discharge of arrows of this kind. Such an arrow has been known to pierce a bronze statue, and if it hits the wall of a very large town, the point of the arrow either protrudes on the inner side or it buries itself in the middle of the wall and is lost. Such then is this monster of a crossbow, and verily a devilish invention. And the wretched man who is struck by it, dies without feeling anything, not even feeling the blow, however strong it be.[85]

— Anna Komnene

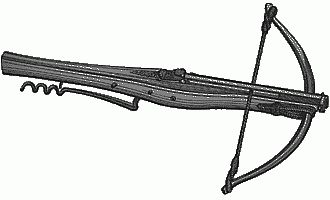

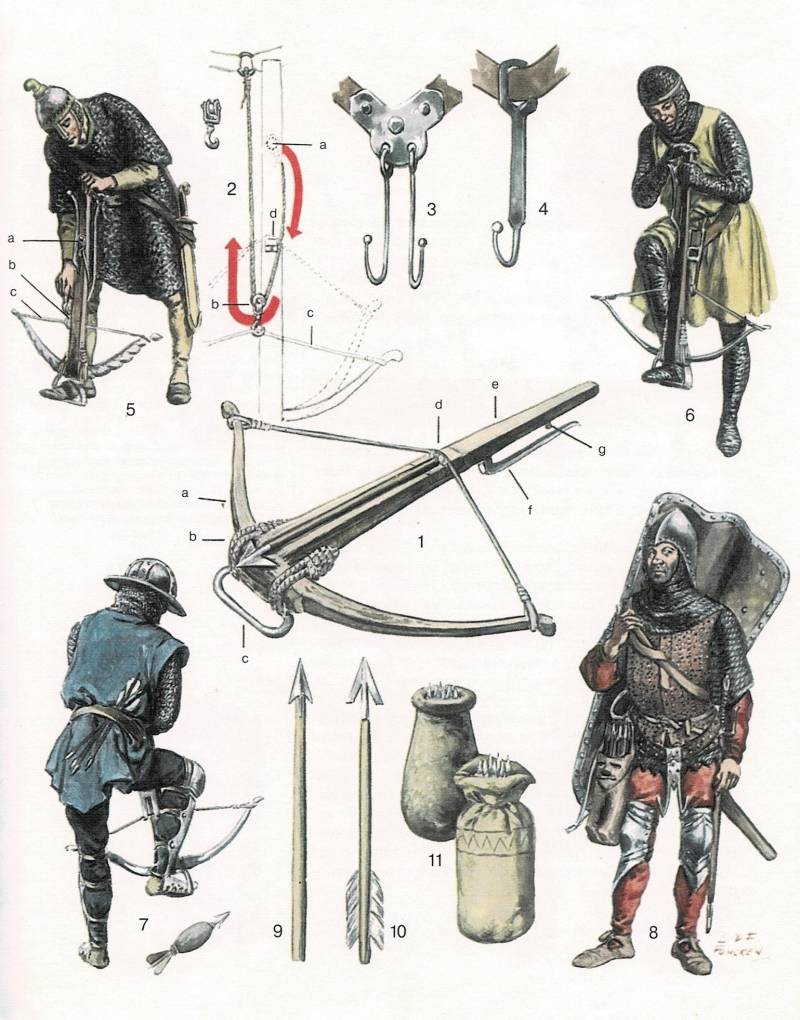

The first medieval European crossbows were made of wood, usually yew or olive wood. Composite lath crossbows began to appear around the end of the 12th century and crossbows with steel laths emerged in the 1300s. Crossbows with steel laths were sometimes referred to as arbalests.[8] These had much higher draw weights than composite bows and required mechanical aids such as the cranequin or windlass for spanning. Usually these could only shoot two bolts per minute versus twelve or more with a skilled archer, often necessitating the use of a pavise to protect the operator from enemy fire. Despite the appearance of stronger bows, wooden laths remained popular into the 1400s due to being less sensitive to the water and cold.[86]

The crossbow superseded hand bows in many European armies during the 12th century, except in England, where the longbow was more popular. Along with polearm weapons made from farming equipment, the crossbow was also a weapon of choice for insurgent peasants such as the Taborites. Genoese crossbowmen, recruited in Genoa and in different parts of northern Italy, were famous mercenaries hired throughout medieval Europe, while the crossbow also played an important role in anti-personnel defense of ships.[87] Some 4,000 crossbowmen joined the Fifth Crusade and 5,000 under Louis IX of France during the Seventh Crusade.[8]

Crossbowmen occupied a high status as professional soldiers and often earned higher pay than other foot soldiers.[88] The rank of the commanding officer of crossbowmen corps was one of the highest positions in many medieval armies, including those of Spain, France, and Italy. Crossbowmen were held in such high regard in Spain that they were granted status on par with the knightly class.[83]

The payment for a crossbow mercenary was higher than for a longbow mercenary, but the longbowman did not have to pay a team of assistants and his equipment was cheaper. Thus the crossbow team was twelve percent less efficient than the longbowman since three of the latter could be part of the army in place of one crossbow team. Furthermore, the prod and bow string of a composite crossbow were subject to damage in rain whereas the longbowman could simply unstring his bow to protect the string. French forces employing the composite crossbow were outmatched by English longbowmen at Crécy in 1346, at Poitiers in 1356 and at Agincourt in 1415. As a result, use of the crossbow declined sharply in France,[86] and the French authorities made attempts to train longbowmen of their own. After the conclusion of the Hundred Years’ War, however, the French largely abandoned the use of the longbow, and consequently the military crossbow saw a resurgence in popularity. The crossbow continued to see use in French armies by both infantry and mounted troops until as late as 1520 when, as with elsewhere in continental Europe, the crossbow would be largely eclipsed by the handgun. Spanish forces in the New World would make extensive use of the crossbow, even after it had largely fallen out of use in Europe. Crossbowmen participated in Hernán Cortés’ conquest of the Aztec Empire and accompanied Francisco Pizarro on his initial expedition to Peru, though by the time of the conquest of Inca Empire in 1532-1523 he would have only a dozen such men remaining in his service.[89]

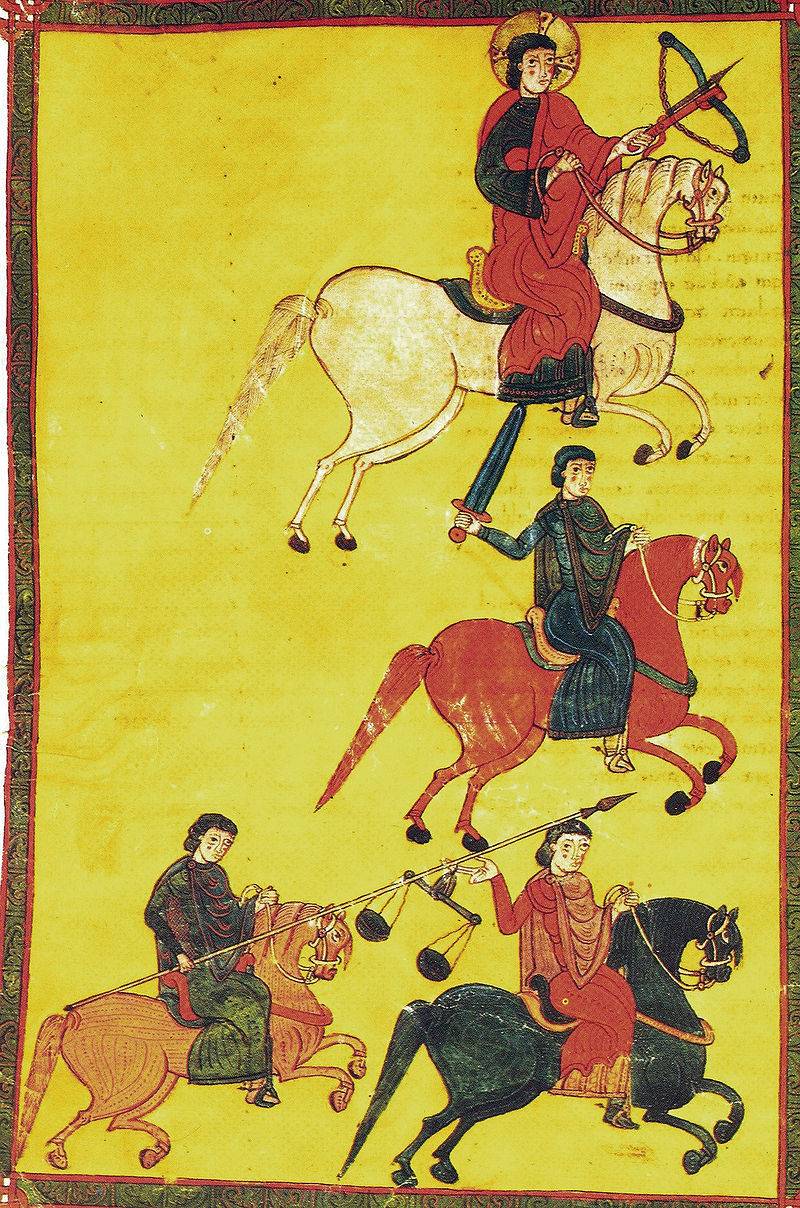

-

Earliest European depiction of cavalry using crossbows, from the Catalan manuscript Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, 1086.

-

Man hunting with a crossbow in Spain, 12th century

-

Man hunting with a crossbow, 14th century

-

Two men arming a crossbow using a stirrup and shooting a crossbow, 1475

-

Man holding a crossbow, 1530s

Chinese and European crossbows in comparison[edit]

The Chinese crossbow had a longer power stroke, around 51 cm (20 in) or so, compared to the early medieval European crossbow, which typically sat around only 10–18 cm (3.9–7.1 in). This was made possible by the more compact design of the Chinese trigger, which allowed it to sit further back at the rear-end of the tiller. The longer horizontal lever on European crossbows necessitated placing it much further forward. Longer Chinese power strokes were also made possible by the relatively short Chinese composite bow, which could be drawn further back without fear of breaking. Chinese crossbows had draw-weights ranging from 68 to 340 kg (150 to 750 lb).[8][90]

…the Chinese made much more extensive use of the crossbow as an infantry weapon than the Byzantines did, and the Chinese crossbow was a more sophisticated device than its Western counterpart. European crossbows used a revolving nut and one-lever trigger, while Chinese crossbows had a precisely engineered, three-piece bronze mechanism including «an intermediate lever that enabled the bowman to fire a heavy bow with a short, crisp and light pull on the trigger.[80]

— David Graff

When Europeans began fielding crossbows on battlefields in earnest during the 10th century AD, not only were the triggers more cumbersome, the bows were made of wood. However, by the 13th century European crossbows began transitioning to composite bows as well, increasing their draw weight. While still utilizing the rolling nut mechanism, 13th century European composite crossbows were probably not much worse compared to the Chinese crossbow, if at all, in terms of draw-weight. From the 13th century onward, European crossbows made use of spanning mechanisms not seen in China such as the pulley, gaffle, cranequin, and screw. Furthermore, 14th century European crossbows could be made of steel, increasing their draw weights beyond even the heaviest Chinese infantry crossbow. These were accompanied by the cord pulley spanning device. However, the power stroke of the European crossbows remained much lower than that of Chinese crossbows (typically one third of the powerstroke), which limited their power despite increasing draw weights.[8]

For example, a 150-pound (68 kg) draw crossbow with an 11-inch (280 mm) powerstroke can shoot a 400 grain arrow at 205 fps, while a 150-pound draw crossbow with a 12-inch (300 mm) powerstroke can shoot a 400 grain arrow at 235 fps. This translates into a 14.6% increase in power for every 9% increase in powerstroke.[91] Thus, if other factors are equal, a standard Han Dynasty crossbow with a ≈387-pound (176 kg) draw weight and a 20–21-inch (510–530 mm) powerstroke would have comparable levels of power to a medieval European crossbow with a 1,200-pound (540 kg) draw weight and a 6–7-inch (150–180 mm) powerstroke.[92][93]

European crossbows were phased out in the 16th century in favor of arquebuses and muskets. In China, the crossbow was not considered a serious military weapon by the end of the late Ming dynasty, but continued to see limited usage into the 19th century.

| Chinese (7th c. BC-) | Gastraphetes (5th c. BC) | Arcuballista (4th c. AD) | European (10th c.) | European (13th c.) | European (late 14th c.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bow length (cm) | 70-145 | 99 | 122 | 58-91 | 80 | |

| Tiller length (cm) | 60-70 | 25.5 | 95.5 | |||

| Power stroke (cm) | 46-51 | 41 | 10-18 | 16 | ||

| Draw-weight (kg) | 68-340 | 55-90 | 20.5 | 36-90 | 90-270 | 180-680 |

| Range (m) | 170-450 | 230 | 91.5 | 340-411 | ||

| Lock mechanism | bronze vertical trigger | bronze block and lever | rolling nut – bone, antler | rolling nut | rolling nut – metal | |

| Spanning device | winch, stirrup (12th c.), belt claw (late) |

claw & lever | stirrup (12th c.), belt claw (12th c.) |

winch | winch pulleys, gaffle, cranequin, screw, cord pulley (15th c.) |

|

| Crossbow material | composite | composite | wood | composite | steel | |

| Repeating crossbow material | mulberry wood/bamboo |

Japan[edit]

Oyumi were ancient Japanese artillery pieces that first appeared in the seventh century (during the Asuka Period).[94] According to Japanese records, the Oyumi was different from the hand held crossbow also in use during the same time period. A quote from a seventh-century source seems to suggest that the Oyumi may have able to fire multiple arrows at once: «the Oyumi were lined up and fired at random, the arrows fell like rain».[95] A ninth century Japanese artisan named Shimaki no Fubito claimed to have improved on a version of the weapon used by the Chinese; his version could rotate and fire projectiles in multiple directions.[96][97] The last recorded use of the Oyumi was in 1189.[98]

Islamic world[edit]

Mamluk with a crossbow, 12th century

There are no references to crossbows in Islamic texts earlier than the 14th century. Arabs in general were averse to the crossbow and considered it a foreign weapon. They called it qaus al-rijl (foot-drawn bow), qaus al-zanbūrak (bolt bow) and qaus al-faranjīyah (Frankish bow). Although Muslims did have crossbows, there seems to be a split between eastern and western types. Muslims in Spain used the typical European trigger while eastern Muslim crossbows had a more complex trigger mechanism.[99]

Mamluk cavalry used crossbows.[8]

Africa and South America[edit]

In Central Africa simple crossbows were used for hunting and as a scout weapon, previously thought to have been first introduced by the Portuguese. Until recently they were especially in use by different tribes of the pygmy-people, usually with poisoned and relatively small arrows. This silent technique of hunting in the tropical forest is quite similar to that of the South American indigenous hunting method with blow pipe and poisoned arrows. It makes sure not to startle up the prey, for example if a first shot goes astray. Since the small arrow is rarely deadly itself, the animal will drop from the trees after some time because of the poisoning.

In the American South, the crossbow was used by the conquistadors for hunting and warfare when firearms or gunpowder were unavailable because of economic hardships or isolation.[87]

Use of crossbows today[edit]

French soldiers with a Sauterelle bomb-throwing crossbow in 1915.

A whale shot by a modified crossbow bolt

Crossbows today are mostly used for target shooting in modern archery. In some countries they are still used for hunting, such as in most of states within the US, parts of Asia, Europe, Australia and Africa. Crossbows with special projectiles are used in whale research to take blubber biopsy samples without harming the whales or other marine big «game» .[100]

Modern military and paramilitary usage[edit]

Crossbows were eventually replaced in warfare by gunpowder weapons, although early guns had slower rates of fire and much worse accuracy than contemporary crossbows. The Battle of Cerignola in 1503 was largely won by Spain through the use of matchlock firearms, marking the first time a major battle was won through the use of firearms. Later, similar competing tactics would feature harquebusiers or musketeers in formation with pikemen, pitted against cavalry firing pistols or carbines. While the military crossbow had largely been supplanted by firearms on the battlefield by 1525, the sporting crossbow in various forms remained a popular hunting weapon in Europe until the eighteenth century.[101]

A bomb-throwing crossbow called the Sauterelle was used by the French and British armies on the Western Front during World War I. It could throw an F1 grenade or Mills bomb 110–140 m (120–150 yd).[102]

The crossbow is still used in modern times by various militaries,[103][104][105][106] tribal forces[107] and in China even by the police forces. As their worldwide distribution is not restricted by regulations on arms, they are used as silent weapons and for their psychological effect,[108] even reportedly using poisoned projectiles.[109] Crossbows are used for ambush and anti-sniper[110] operations or in conjunction with ropes to establish zip-lines in difficult terrain.[111]

See also[edit]

- Hymn to the Fallen (Jiu Ge)

- Medieval warfare

- Panjagan, a possible crossbow type Sasanian weapon

References[edit]

- ^ Peers 1996, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Needham 1994, p. 121-122.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 155.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 171.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 173.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 174.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 178.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Loades 2018.

- ^ You (1994), 80.

- ^ A Crossbow Mechanism with Some Unique Features from Shandong, China Archived 29 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Asian Traditional Archery Research Network. Retrieved on 2008-08-20.

- ^ Wagner, Donald B. (1993). Iron and Steel in Ancient China: Second Impression, With Corrections. Leiden: E.J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-09632-9. pp. 153, 157–158.

- ^ Mao (1998), 109–110.

- ^ Wright (2001), 159.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd, p. 227.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 89.

- ^ James Clavell, The Art of War, prelude

- ^ «Archived copy». Archived from the original on 4 May 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Needham 1994, p. 34.

- ^ Peers 2006, p. 39.

- ^ Lewis 2007, p. 38.

- ^ a b Needham 1994, p. 141.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 139.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 22.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 138.

- ^ Peers, 130–131.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 143.

- ^ Graff 2002, p. 22.

- ^ Hsiao 2014, p. 221.

- ^ Graff 2002, p. 193.

- ^ Graff 2016, p. 51-52.

- ^ a b c Needham 1994, p. 145.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 146.

- ^ Swope 2014, p. 49.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 150.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 120.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 123-125.

- ^ a b Peers, 130.

- ^ Jackson 2005, p. 71.

- ^ Lin, Yun. «History of the Crossbow,» in Chinese Classics & Culture, 1993, No.4: p. 33–37.

- ^ Unique weapon of the Ming Dynasty – Zhu Ge Nu (諸葛弩), 24 September 2015, retrieved 16 April 2018

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Liang 2006.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 8.

- ^ Turnbull 2002, p. 14.

- ^ Nicolle 2003, p. 23.

- ^ Haw 2013, p. 36-37.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 198.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 177.

- ^ Willey, Peter (2005). Eagle’s Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 75–85. ISBN 978-1-85043-464-1.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 189-190.

- ^ a b c Needham 1994, p. 192.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 176.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 188.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 125.

- ^ a b c Andrade 2016, p. 149.

- ^ a b c d Andrade 2016, p. 150.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 149-150.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 152.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 153-154.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 154.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 135.

- ^ Kelley 2014, p. 88.

- ^ a b Taylor 1983, p. 21.

- ^ Turnbull 2002.

- ^ Grant 2005, p. 100.

- ^ Turnbull 2001, p. 42.

- ^ Turnbull 2001.

- ^ Campbell 2003, pp. 3ff.

- ^ a b DeVries 2003, p. 127.

- ^ DeVries 2003, p. 128.

- ^ Burstein 1999, p. 366.

- ^ Campbell 2005, p. 26-56.

- ^ Campbell 2003, p. 8ff.

- ^ a b Marsden 1969, p. 57.

- ^ Campbell 2003, p. 8.

- ^ Marsden 1969, p. 60.

- ^ Josiah Ober: Early Artillery Towers: Messenia, Boiotia, Attica, Megarid, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 91, No. 4. (1987), S. 569–604 (569)

- ^ «Tastes of History: Arcuballista: A Late Roman Crossbow». 15 December 2016.

- ^ Hall 1997, p. 238.

- ^ a b Needham 1994, p. 172.

- ^ a b Graff 2016, p. 52.

- ^ John M. Gilbert, Hunting and Hunting Reserves in Medieval Scotland (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1979), p. 62.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 170.

- ^ a b Payne-Gallwey 1995, p. 48.

- ^ Stouraitis 2018, p. 372-373.

- ^ McKeogh 2002, p. 67.

- ^ a b Robert Hardy (1992). «Longbow: A Social and Military History». Lyons & Burford. ISBN 1-85260-412-3, p. 75

- ^ a b Notes On West African Crossbow Technology

- ^ Robert Hardy (1992). «Longbow: A Social and Military History». Lyons & Burford. ISBN 1-85260-412-3, p. 44

- ^ Paye-Gallwey 1995, p. 48.

- ^ The Crossbow. Bloomsbury. 9 March 2018. ISBN 9781472824622.

- ^ «Crossbows / Draw Weight».

- ^ History & Uniforms, By Bruno Mugnai;

https://books.google.com/books?id=-N4cDQAAQBAJ&pg=PP8&dq=6+stone+crossbow&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiU4K6Wv93gAhUSn-AKHeJmBlsQ6AEIKjAA#v=onepage&q=6%20stone%20crossbow&f=false - ^ Chinese Archery, By Stephen Selby;

https://books.google.com/books?id=wY3sAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA172&dq=han+crossbow&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj3i7W9t93gAhUJm-AKHc4uDeoQ6AEINjAC#v=onepage&q=han%20crossbow%20&f=false - ^ Japanese Castles AD 250—1540, Stephen Turnbull, Peter Dennis, Illustrated by Peter Dennis, Osprey Publishing, 2008 ISBN 9781846032530 P.49

- ^ Japanese Castles AD 250—1540, Stephen Turnbull, Peter Dennis, Illustrated by Peter Dennis, Osprey Publishing, 2008 ISBN 9781846032530 P.49

- ^ Louis, Thomas; Ito, Tommy (August 2008). Samurai: The Code of the Warrior. ISBN 9781402763120.

- ^ Hired Swords: The Rise of Private Warrior Power in Early Japan, By Karl Friday, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992 P.42

- ^ Japanese Castles AD 250–1540, Stephen Turnbull, Peter Dennis, Illustrated by Peter Dennis, Osprey Publishing, 2008 ISBN 9781846032530 P.49

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 175.

- ^ The St. Lawrence

- ^ Payne-Gallwey 1995, p. 48-53.

- ^ The Royal Engineers Journal. The Institution of Royal Engineers. 39: 79. 1925.

- ^ Chinese news report on crossbows.

- ^ Chinese special forces with crossbows.

- ^ Greek soldiers uses crossbow.

- ^ Turkish special ops.

- ^ «Crossbow for women». Archived from the original on 4 June 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ Day Life Serbia report Archived 12 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ bharat-rakshak article on Marine Commandos Archived 25 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Guardian.

- ^ Ejercito prepare for deployment. Archived 5 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

Sources[edit]

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 9781400874446

- Burstein, M. (1999), Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History, Oxford University Press

- Campbell, Duncan (2003), Greek and Roman Artillery 399 BCE-CE 363, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84176-634-8

- Campbell, Duncan (2005), Ancient Siege Warfare, Osprey

- Crombie, Laura (2016), Archery and Crossbow Guilds in Medieval Flanders, Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, ISBN 9781783271047

- DeVries, Kelly (2003), Medieval Military Technology, Broadview Press

- Graff, David A. (2002), Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900, Warfare and History, London: Routledge, ISBN 0415239559

- Graff, David A. (2016), The Eurasian Way of War: Military practice in seventh-century China and Byzantium, Routledge

- Grant, R.G. (2005), Battle: A Visual Journey Through 5,000 Years of Combat, DK Pub.

- Hall, Bert S. (1997), Weapons and Warfare in Renaissance Europe

- Haw, Stephen G. (2013), Cathayan Arrows and Meteors: The Origins of Chinese Rocketry

- Hsiao, Kuo-Hung (2014), Mechanisms in Ancient Chinese Books with Illustrations, Springer

- Jackson, Peter (2005), The Mongols and the West, Pearson Education Limited

- Lewis, Mark Edward (2007), The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

- Taylor, Keith Weller (1983). The Birth of the Vietnam. University of California Press.

- Kelley, Liam C. (2014), «Constructing Local Narratives: Spirits, Dreams, and Prophecies in the Medieval Red River Delta», in Anderson, James A.; Whitmore, John K. (eds.), China’s Encounters on the South and Southwest: Reforging the Fiery Frontier Over Two Millennia, United States: Brills, pp. 78–106

- Liang, Jieming (2006), Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity, Singapore, Republic of Singapore: Leong Kit Meng, ISBN 981-05-5380-3

- Loades, Mike (2018), The Crossbow, Osprey

- Lu, Yongxiang (2015), A History of Chinese Science and Technology Volume 3, Springer

- Marsden, Eric William (1969), Greek and Roman Artillery: Historical Development, The Clarendon Press

- McKeogh, C. (2002), Innocent Civilians: The Morality of Killing in War, Springer

- Needham, Joseph (1994), Science and Civilization in China Volume 5 Part 6, Cambridge University Press

- Nicolle, David (2003), Medieval Siege Weapons (2): Byzantium, the Islamic World & India AD 476-1526, Osprey Publishing

- Payne-Gallwey, Ralph (1995), The Book of the Crossbow, Dover

- Peers, C. J. (1996), Imperial Chinese Armies (2): 590-1260AD, Osprey

- Peers, C.J. (2006), Soldiers of the Dragon: Chinese Armies 1500 BC – AD 1840, Osprey Publishing Ltd

- Schellenberg, Hans Michael (2006), «Diodor von Sizilien 14,42,1 und die Erfindung der Artillerie im Mittelmeerraum» (PDF), Frankfurter Elektronische Rundschau zur Altertumskunde, 3: 14–23

- Stouraitis, Yannis (2018), A Companion to the Byzantine Culture of War

- Swope, Kenneth (2014), The Military Collapse of China’s Ming Dynasty, Routledge

- Turnbull, Stephen (2001), Siege Weapons of the Far East (1) AD 612-1300, Osprey Publishing

- Turnbull, Stephen (2002), Siege Weapons of the Far East (2) AD 960-1644, Osprey Publishing

- Warry, John (1995), Warfare in the Classical World: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Weapons, Warriors, and Warfare in the Ancient Civilizations of Greece and Rome, University of Oklahoma Press

Further reading[edit]

- Nickel, H, ed. (1982). The Art of Chivalry : European arms and armor from the Metropolitan Museum of Art : an exhibition . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The American Federation of Arts.

It is not clear where and when the crossbow originated, but it is believed to have appeared in China and Europe around the 7th to 5th centuries BC. In China the crossbow was one of the primary military weapons from the Warring States period until the end of the Han dynasty, when armies composed of up to 30 to 50 percent crossbowmen were not unheard of. The crossbow lost much of its popularity after the fall of the Han dynasty, likely due to the rise of the more resilient heavy cavalry during the Six Dynasties. One Tang dynasty source recommends a bow to crossbow ratio of five to one as well as the utilization of the countermarch to make up for the crossbow’s lack of speed.[1] The crossbow countermarch technique was further refined in the Song dynasty, but crossbow usage in the military continued to decline after the Mongol conquest of China.[2] Although the crossbow never regained the prominence it once had under the Han, it was never completely phased out either. Even as late as the 17th century, military theorists were still recommending it for wider military adoption, but production had already shifted in favor of firearms and traditional composite bows.[3]

In the Western world a crossbow known as the gastraphetes was described by the Greco-Roman scientist Heron of Alexandria in the 1st century AD. He believed it was the forerunner of the catapult, which places its appearance sometime prior to the 4th century BC during the Classical period.[4] Other than the gastraphetes, the only other evidence of crossbows in ancient Europe are two stone relief carvings from a Roman grave in Gaul and some vague references by Vegetius. Pictish imagery from medieval Scotland dated between the 6th and 9th centuries AD do show what appear to be crossbows, but only for hunting, and not military usage. It’s not clear how widespread crossbows were in Europe prior to the medieval period or if they were even used for warfare. The small body of evidence and the context they provide point to the fact that the ancient European crossbow was primarily a hunting tool or minor siege weapon. An assortment of other ancient European bolt throwers exist such as the ballista, but these were torsion engines and are not considered crossbows. Crossbows are not mentioned in European sources again until 947 as a French weapon during the siege of Senlis.[5] From the 11th century onward, crossbows and crossbowmen occupied a position of high status in medieval European militaries, with the exception of the English and their continued use of the longbow. During the 16th century military crossbows in Europe were superseded by gunpowder weaponry such as cannons and muskets. Hunters continued to carry crossbows for another 150 years due to its silence.[6]

There is a theory that medieval European crossbows originate from China but some differences exist between the two trigger mechanisms used in European and Chinese crossbows.[7]

Terminology[edit]

Han crossbow trigger pieces

A crossbowman or crossbow-maker is sometimes called an arbalist or arbalest.[8]

Arrow, bolt and quarrel are all suitable terms for crossbow projectiles.[8]

The lath, also called the prod, is the bow of the crossbow. According to W.F. Peterson, the prod came into usage in the 19th century as a result of mistranslating rodd in a 16th-century list of crossbow effects.[8]

The stock is the wooden body on which the bow is mounted, although the medieval tiller is also used.[8]

The lock refers to the release mechanism, including the string, sears, trigger lever, and housing.[8]

China[edit]

Illustration of a Ming volley fire formation using crossbows. From Cheng Zongyou 程宗猷, Jue zhang xin fa 蹶張心法 ca. 1621.

Illustration of another Ming crossbow volley fire formation. From Bi Maokang 畢懋康, Jun qi tu shuo 軍器圖說, ca. 1639.

Warring States[edit]

In terms of archaeological evidence, crossbow locks made of cast bronze have been found in China dating to around 650 BC.[8] They have also been found in Tombs 3 and 12 at Qufu, Shandong, previously the capital of Lu, and date to 6th century BC.[9][10] Bronze crossbow bolts dating from the mid-5th century BC have been found at a Chu burial site in Yutaishan, Jiangling County, Hubei Province.[11] Other early finds of crossbows were discovered in Tomb 138 at Saobatang, Hunan Province, and date to mid-4th century BC.[12][13] It’s possible that these early crossbows used spherical pellets for ammunition. A Western-Han mathematician and music theorist, Jing Fang (78-37 BC), compared the moon to the shape of a round crossbow bullet.[14] Zhuangzi also mentions crossbow bullets.[15]

The earliest Chinese documents mentioning a crossbow were texts from the 4th to 3rd centuries BC attributed to the followers of Mozi. This source refers to the use of a giant crossbow between the 6th and 5th centuries BC, corresponding to the late Spring and Autumn Period. Sun Tzu’s The Art of War (first appearance dated between 500 BC to 300 BC[16]) refers to the characteristics and use of crossbows in chapters 5 and 12 respectively,[17] and compares a drawn crossbow to ‘might.’[18]

The state of Chu favorited elite armoured crossbow units known for their endurance, and were capable of marching 160 km ‘without resting.’[19] Wei’s elite forces were capable of marching over 40 km in one day while wearing heavy armour, a large crossbow with 50 bolts, a helmet, a side sword, and three days worth of rations. Those who met these standards earned an exemption from corvée labor and taxes for their entire family.[20]

Han dynasty[edit]

The Huainanzi advises its readers not to use crossbows in marshland where the surface is soft and it is hard to arm the crossbow with the foot.[21] The Records of the Grand Historian, completed in 94 BC, mentions that Sun Bin defeated Pang Juan by ambushing him with a body of crossbowmen at the Battle of Maling.[22] The Book of Han, finished 111 AD, lists two military treatises on crossbows.[23]

In the 2nd century AD, Chen Yin gave advice on shooting with a crossbow in the Wuyue Chunqiu:

When shooting, the body should be as steady as a board, and the head mobile like an egg [on a table]; the left foot [forward] and the right foot perpendicular to it; the left hand as if leaning against a branch, the right hand as if embracing a child. Then grip the crossbow and take a sight on the enemy, hold the breath and swallow, then breathe out as soon as you have released [the arrow]; in this way you will be unperturbable. Thus after deep concentration, the two things separate, the [arrow] going, and the [bow] staying. When the right hand moves the trigger [in releasing the arrow] the left hand should not know it. One body, yet different functions [of parts], like a man and a girl well matched; such is the Dao of holding the crossbow and shooting accurately.[24]

— Chen Yin

It’s clear from surviving inventory lists in Gansu and Xinjiang that the crossbow was greatly favored by the Han dynasty. For example, in one batch of slips there are only two mentions of bows, but thirty mentions of crossbows.[21] Crossbows were mass-produced in state armories with designs improving as time went on, such as the use of a mulberry wood stock and brass; a crossbow in 1068 could pierce a tree at 140 paces.[25] Crossbows were used in numbers as large as 50,000 starting from the Qin dynasty and upwards of several hundred thousand during the Han.[26] According to one authority, the crossbow had become «nothing less than the standard weapon of the Han armies,» by the second century BC.[27] Han era carved stone images and paintings also contain images of horsemen wielding crossbows. Han soldiers were required to pull an «entry level» crossbow with a draw-weight of 76 kg to qualify as a crossbowman.[8]

| Item | Number | Government |

|---|---|---|

| Crossbow | 537,707 | 11,181 |

| Crossbow bolts | 11,458,424 | 34,265 |

| Bow | 77,521 | |

| Arrows | 1,199,316 | 511 |

-

-

Han crossbow trigger on a crossbow frame

-

Large crossbow trigger (23.49 x 17.78 cm) for mounted crossbows, Han dynasty

Later history[edit]

Korean giant naval crossbow (repeating)

Before the Han Dynasty, the trigger mechanism did not have a Guo (郭, a casing), so that the parts of the trigger mechanism were installed in the wooden frame directly. After the Han Dynasty, the original crossbow has two important design improvements. The first one is to add a bronze casing, and the other is to include a scale table with the shooting range on the trigger mechanism. The parts of the trigger mechanism installed in the bronze casing can provide higher tension than those installed on the wooden frame. As a result, its shooting range has increased greatly. Adding a scale table with the shooting range on the trigger mechanism increases the accuracy of the shooting and helps the shooter to hit the target more easily. After the Han Dynasty, the structures of the original crossbow and trigger mechanism have not changed except that the size became larger to increase the shooting range.[28]

After the Han dynasty, the crossbow lost favor until it experienced a mild resurgence during the Tang dynasty, under which the ideal expeditionary army of 20,000 included 2,200 archers and 2,000 crossbowmen.[29] Li Jing and Li Quan prescribed 20 percent of the infantry to be armed with standard crossbows, which could hit the target half the time at a distance of 345 meters, but had an effective range of 225 meters.[30]

During the Song dynasty, the government attempted to restrict the spread of military crossbows and sought ways to keep armour and crossbows out of private homes.[31] Despite the ban on certain types of crossbows, the weapon experienced an upsurge in civilian usage as both a hunting weapon and pastime. The «romantic young people from rich families, and others who had nothing particular to do» formed crossbow shooting clubs as a way to pass time.[32]

During the late Ming dynasty, no crossbows were mentioned to have been produced in the three-year period from 1619 to 1622. With 21,188,366 taels, the Ming manufactured 25,134 cannons, 8,252 small guns, 6,425 muskets, 4,090 culverins, 98,547 polearms and swords, 26,214 great «horse decapitator» swords, 42,800 bows, 1,000 great axes, 2,284,000 arrows, 180,000 fire arrows, 64,000 bow strings, and hundreds of transport carts.[33]

Military crossbows were armed by treading, or basically placing the feet on the bow stave and drawing it using one’s arms and back muscles. During the Song dynasty, stirrups were added for ease of drawing and to mitigate damage to the bow. Alternatively the bow could also be drawn by a belt claw attached to the waist, but this was done lying down, as was the case for all large crossbows. Winch-drawing was used for the large mounted crossbows as seen below, but evidence for its use in Chinese hand-crossbows is scant.[34]

| Army | Chariot | Crossbow | Bow | Cavalry | Assault | Maneuver | Halberd | Spear | Basic infantry | Supply | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal WS | 6,000 | 2,000 | 2,000 | 10,000 | |||||||

| Ideal WS Zhao | 1,300 | 100,000 | 13,000 | 50,000 | 164,300 | ||||||

| Anti-Xiongnu Han (97 BC) | 70,000 | 140,000 | 210,000 | ||||||||

| Later Zhao | 27,000 | 60,000 | 87,000 | ||||||||

| Former Qin | 270,000 | 250,000 | 350,000 | 870,000 | |||||||

| Basic Sui expedition | 4,000 | 8,000 | 8,000 | 20,000 | |||||||

| Basic early Tang expedition | 2,000 | 2,200 | 4,000 | 2,900 | 2,900 | 6,000 | 20,000 |

Advantages and disadvantages[edit]

Now for piercing through hard things and shooting a long distance, and when struggling to defend mountain-passes, where much noise and impetuous strength must be stemmed, there is nothing like the crossbow for success. However, as the drawing (i.e. the arming) is slow, it is difficult to cope with sudden attacks. A crossbow can only be shot off [by a single man] three times before it comes to hand-to-hand weapons. Some have therefore thought crossbows inconvenient for fighting, but truly the inconvenience lay not in the crossbow itself but in the commanders, who did not know how to make use of crossbows. All the military theorists of the Tang maintained that the crossbow had no advantage over hand-to-hand weapons, and they insisted on having long bills and great shields in the front line to repel the charge, and made the crossbowmen to carry sabres and long-hafted weapons. The result was that if the enemy adopted an open-order formation and attacked with hand-to-hand weapons, the soldiers would throw away their crossbows and have recourse to those also. A body of the rearguard was therefore detailed beforehand to go round and collect up the crossbows.[2]

The crossbow allowed archers to shoot bows of greater strength and more accurately as well due to its greater stability, but at the cost of speed.[35]

In 169 BC, Chao Cuo observed that by using the crossbow, it was possible to overcome the Xiongnu:

Of course, in mounted archery [using the short bow] the Yi and the Di are skilful, but the Chinese are good at using nu che. These carriages can be drawn up in the form of a laager which cannot be penetrated by cavalry. Moreover, the crossbows can shoot their bolts to a considerable range, and do more harm [lit. penetrate deeper] than those of the short bow. And again, if the crossbow bolts are picked up by the barbarians they have no way of making use of them. Recently the crossbow has unfortunately fallen into some neglect; we must carefully consider this… The strong crossbow [jing nu] and the [arcuballista shooting] javelins have a long range; something which the bows of the Huns can no way equal. The use of sharp weapons with long and short handles by disciplined companies of armoured soldiers in various combinations, including the drill of crossbow men alternately advancing [to shoot] and retiring [to load]; this is something which the Huns cannot even face. The troops with crossbows ride forward [cai guan shou] and shoot off all their bolts in one direction; this is something which the leather armour and wooden shields of the Huns cannot resist. Then the [horse-archers] dismount and fight forward on foot with sword and bill; this is something which the Huns do not know how to do.[36]

The Wujing Zongyao states that the crossbow used en masse was the most effective weapon against northern nomadic cavalry charges. Even if they failed, the quarrels were too short to be used as regular arrows so they couldn’t be used again by nomadic archers after the battle.[37] The crossbow’s role as an anti-cavalry weapon was later reaffirmed in Medieval Europe when Thomas the Archdeacon recommended them as the optimal weapon against the Mongols.[38] Elite crossbowmen were used to pick off targets as was the case when the Liao Dynasty general Xiao Talin was picked off by a Song crossbowman at the Battle of Shanzhou in 1004.[37]

Repeating crossbow[edit]

The earliest extant repeating crossbow, a double-shot repeating crossbow excavated from a tomb of the State of Chu, 4th century BC.

The Zhuge Nu is a handy little weapon that even the Confucian scholar or palace women can use in self-defence… It fires weakly so you have to tip the darts with poison. Once the darts are tipped with «tiger-killing poison», you can shoot it at a horse or a man and as long as you draw blood, your adversary will die immediately. The draw-back to the weapon is its very limited range.[8]