Содержание:

- 1 Что такое

- 2 От чего зависит движение Луны

- 3 Чему равно

- 4 Как в древней Греции астрономы рассчитывали расстояние до Луны

- 5 Материалы по теме

- 6 Эволюция методик измерения расстояния до Луны

- 7 Эволюция системы Луна и Земля

- 8 Интересные факты

Что такое

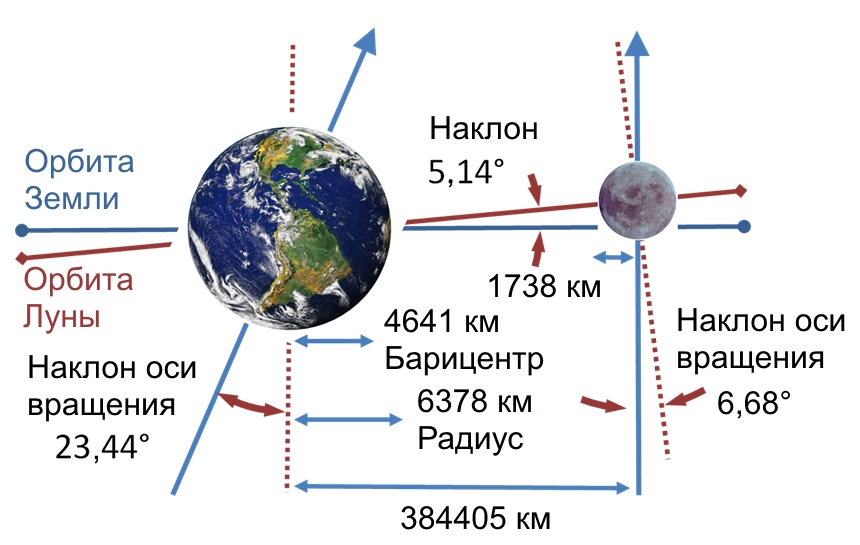

Расстояние от Земли до Луны теоретически измеряется от центра Луны до центра Земли. Измерить это расстояние обычными методами, используемыми в обычной жизни, невозможно. Поэтому дистанция до земного спутника вычислялась по тригонометрическим формулам.

Перигей и апогей Луны

Аналогично Солнцу, Луна испытывает постоянное движение на земном небе вблизи эклиптики. Тем не менее, это движение значительно отличается от движения Солнца. Так плоскости орбит Солнца и Луны различаются на 5 градусов. Казалось бы, вследствие этого траектория Луны на земном небе должна быть похожа в общих чертах на эклиптику, отличаясь от нее только сдвигом на 5 градусов:

В этом движение Луна напоминает движение Солнца – с запада на восток, в противоположном направлении суточному вращению Земли. Но кроме того Луна движется по земному небу гораздо быстрее Солнца. Это связано с тем, что Земля совершает оборот вокруг Солнца примерно за 365 суток (земной год), а Луна вокруг Земли всего за 29 суток (лунный месяц). Это различие и стало стимулом к разбивке эклиптики на 12 зодиакальных созвездий (за один месяц Солнце смещается по эклиптике на 30 градусов). За время лунного месяца происходит полная смена фаз Луны:

Лунные фазы

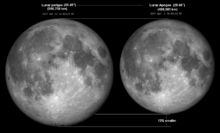

В дополнение к траектории движения Луны добавляется ещё и фактор сильной вытянутости орбиты. Эксцентриситет орбиты Луны составляет 0.05 (для сравнения у Земли этот параметр равен 0.017). Отличие от круговой орбиты Луны приводит к тому, что видимый диаметр Луны постоянно меняется от 29 до 32 угловых минут.

В конечном итоге траектория положения Луны на земном небе постоянно мигрирует относительно фоновых звезд и эклиптики

За сутки Луна смещается относительно звезд на 13 градусов, за час примерно на 0.5 градусов. Современные астрономы часто используют покрытия Луны для оценок угловых диаметров звезд вблизи эклиптики.

От чего зависит движение Луны

Сравнение видимого диаметра Луны на земном небе в перицентре и апоцентре лунной орбиты

Кроме того наблюдаются и колебания наклонения лунной орбиты к эклиптике: примерно на 18 угловых минут каждые 19 лет.

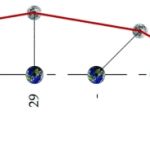

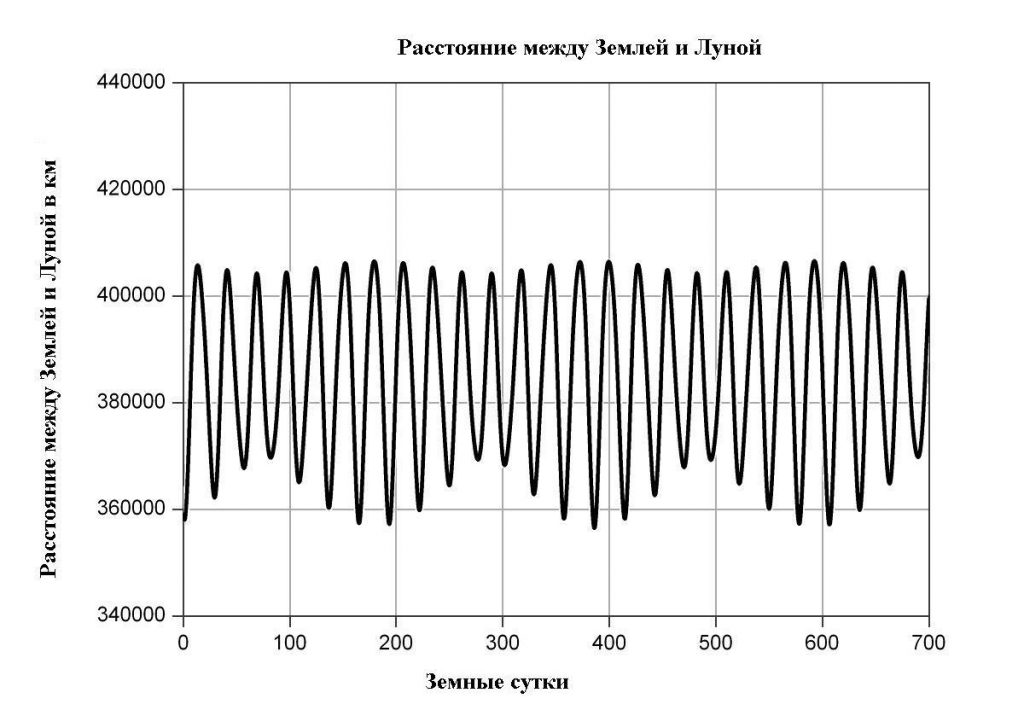

График изменения расстояния между Землей и Луной за 2 года

Чему равно

Свет от Земли до нашего спутника доберется очень быстро – за 1,255 секунд

Космическим кораблям придется потратить на полет к земному спутнику немало времени. До Луны нельзя лететь по прямой – планета будет уходить по орбите в сторону от точки назначения, и путь придется корректировать. При второй космической скорости в 11 км/с (40 000 км/ч) полет теоретически займет около 10 часов, но на деле это будет происходить дольше. Все потому, что корабль на старте постепенно наращивает скорость в атмосфере, доводя ее до значения в 11 км/с, чтобы вырваться из поля тяготения Земли. Затем кораблю придется тормозить при подлете к Луне. Кстати, эта скорость- максимум, чего удалось добиться современным космическим кораблям.

Пресловутый полет американцев на Луну в 1969 году, согласно официальным данным, занял 76 часов. Быстрее всех до Луны удалось долететь аппарату НАСА «Новые горизонты» — за 8 часов 35 минут. Правда, он не приземлился на планетоид, а пролетел мимо – у него была другая миссия.

Свет от Земли до нашего спутника доберется очень быстро – за 1,255 секунд. Но полеты на световых скоростях – пока что из области фантастики.

Можно попытаться представить путь до Луны в привычных величинах. Пешком при скорости 5 км/ч дорога до Луны займет порядка девяти лет. Если поехать на машине на скорость в 100 км/ч, то добираться до земного спутника придется 160 дней. Если бы на Луну летали самолеты, то рейс до нее продлился бы где-то 20 дней.

Как в древней Греции астрономы рассчитывали расстояние до Луны

Расстояние от Земли до Луны

Луна стала первым небесным телом, до которого удалось рассчитать расстояние от Земли. Считается, что первыми это сделали астрономы в Древней Греции.

Измерить расстояние до Луны пытались с незапамятных времен – первым это попытался сделать Аристарх Самосский. Он оценил угол между Луной и Солнцем в 87 градусов, поэтому вышло, что Луна ближе Солнца в 20 раз (косинус угла равного 87 градуса равен 1/20). Ошибка измерений угла привела к 20-кратной ошибке, сегодня известно, что это отношение на самом деле равно 1 к 400 (угол равен примерно 89.8 градусов). Большая ошибка была вызвана трудностью оценок точного углового расстояния между Солнцем и Луной с помощью примитивных астрономических инструментов Древнего мира. Регулярные солнечные затмения к этому времени уже позволили древнегреческим астрономам сделать вывод о том, что угловые диаметры Луны и Солнца примерно одинаковы. В связи с этим Аристарх сделал вывод, что Луна меньше Солнца в 20 раз (на самом деле примерно в 400 раз).

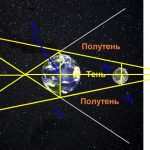

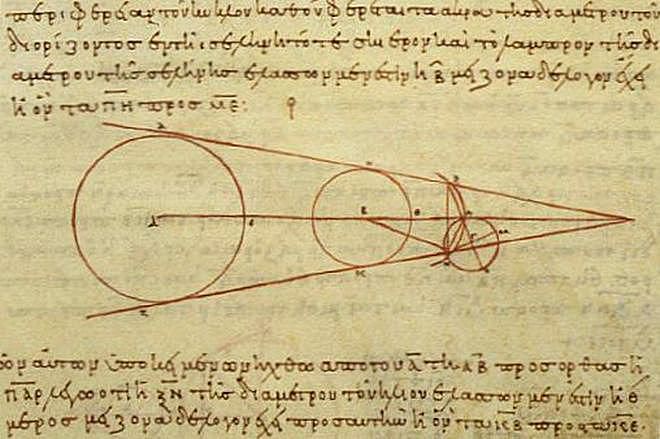

Для вычисления размеров Солнца и Луны относительно Земли Аристарх использовал другой метод. Речь идет о наблюдениях лунных затмений. К этому времени древние астрономы уже догадались о причинах этих явлений: Луна затмевается тенью Земли.

На схеме выше хорошо видно, что разность расстояний с Земли до Солнца и до Луны пропорциональна разнице между радиусами Земли и Солнца и радиусами Земли и её тени на расстояние Луны. Во времена Аристарха уже удалось оценить, что радиус Луны равен примерно 15 угловым минутам, а радиус земной тени составляет 40 угловых минут. То есть размер Луны получался примерно в 3 раза меньше размера Земли. Отсюда зная угловой радиус Луны можно было легко оценить, что Луна находится от Земли примерно в 40 диаметрах Земли. Древние греки могли лишь приблизительно оценить размеры Земли. Так Эратосфен Киренский (276 – 195 годы до нашей эры) на основе различий в максимальной высоте Солнца над горизонтом в Асуане и Александрии во время летнего солнцестояния определил, что радиус Земли близок к 6287 км (современное значение 6371 км). Если подставить это значение в оценку Аристарха насчет расстояния до Луны, то оно будет соответствовать примерно 502 тысяч км (современное значение среднего расстояния от Земли до Луны составляет 384 тысяч км).

Чуть позже математик и астроном II века до н. э. Гиппарх Никейский подсчитал, что расстояние до земного спутника в 60 раз больше, чем радиус нашей планеты. Его расчеты основывались на наблюдениях за движением Луны и его периодических затмениях.

Материалы по теме

Так как в момент затмения Солнце и Луна будут иметь одинаковые угловые размеры, то по правилам подобия треугольников можно найти отношение расстояний до Солнца и до Луны. Эта разница составляет 400 раз. Применяя еще раз эти правила, только уже по отношению к диаметрам Луны и Земли, Гиппарх вычислил, что диаметр Земли больше диаметра Луны в 2,5 раза. Т.е Rл = Rз/2,5.

Под углом в 1′ можно наблюдать предмет, размеры которого в 3 483 раза меньше, чем расстояние до него – эта информация во времена Гиппарха была всем известна. То есть, при наблюдаемом радиусе Луны в 15′ она будет ближе к наблюдателю в 15 раз. Т.е. отношение расстояния до Луны к ее радиусу будет равно 3483/15= 232 или Sл= 232Rл.

Соответственно, дистанция до Луны – это 232* Rз /2,5= 60 радиусов Земли. Это получается 6 371*60=382 260 км. Самое интересное, что измерения, выполненные при помощи современных инструментов, подтвердили правоту античного ученого.

Сейчас измерение дистанции до Луны проводится при помощи лазерных приборов, позволяющих измерить его с точностью до нескольких сантиметров. При этом измерения происходят за очень короткое время – не более 2 секунд, за которое Луна удаляется по орбите примерно на 50 метров от точки отправки лазерного импульса.

Эволюция методик измерения расстояния до Луны

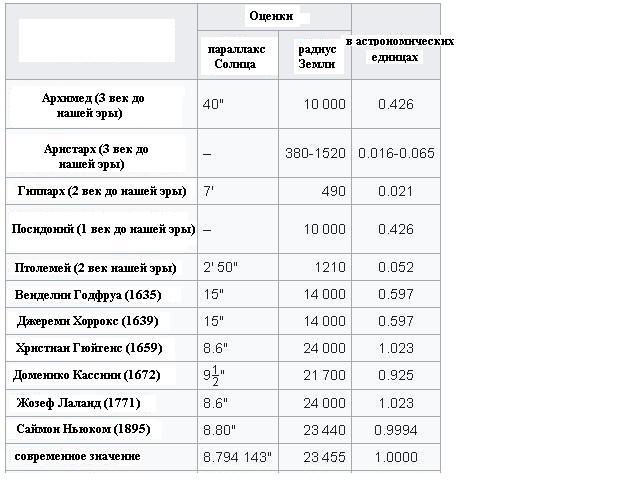

Только с изобретением телескопа астрономы смогли получить более-менее точные значения параметров орбиты Луны и соответствия её размеров с размером Земли.

Пример эволюции астрономической единицы со временем

Более точный метод измерения расстояния до Луны появился в связи с развитием радиолокации. Первая радиолокация Луны была проведены в 1946 году в США и Великобритании. Радиолокация позволяла измерить расстояние до Луны с точностью в несколько километров.

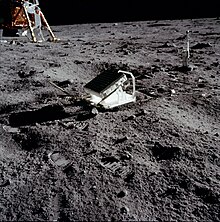

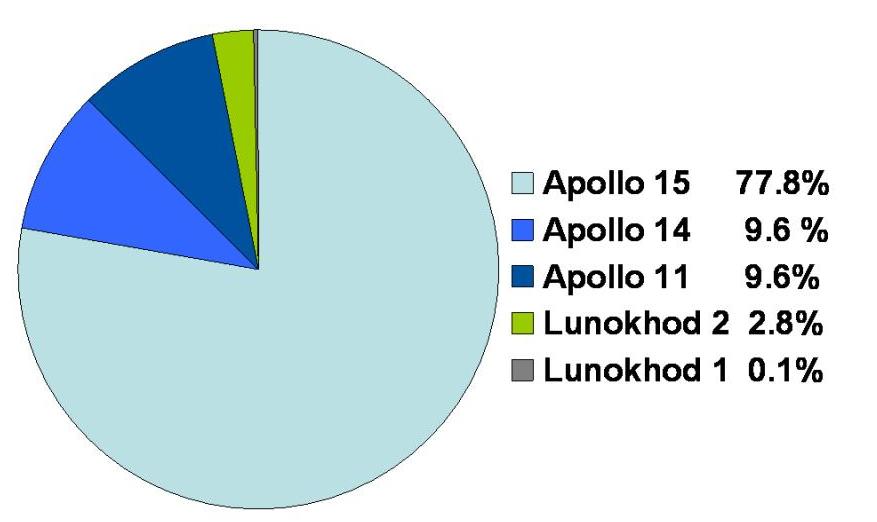

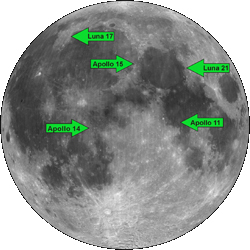

Ещё более точным методом измерения расстояния до Луны стала лазерная локация. Для его реализации в 1960х годах на Луне было установлено несколько уголковых отражателей. Интересно отметить, что первые эксперименты по лазерной локации были проведены ещё до установки уголковых отражателей на поверхности Луны. В 1962-1963 годах в Крымской обсерватории СССР были проведены несколько экспериментов по лазерной локации отдельных лунных кратеров с использованием телескопов диаметром от 0.3 до 2.6 метров. Эти эксперименты смогли определять расстояние до поверхности Луны с точностью в несколько сотен метров. В 1969-1972 годы астронавты программы “Аполлон” доставили на поверхность нашего спутника три уголковых отражателя. Среди них наиболее совершенным был отражатель миссии “Апполон-15”, так как он состоял 300 призм, тогда как два других (миссии “Апполон-11” и “Апполон-14”) только из ста призм каждый.

Карта положения уголковых отражателей

Кроме того в 1970 и 1973 годах СССР доставил на поверхность Луны ещё два французских уголковых отражателя на борту самоходных аппаратов “Луноход-1” и “Луноход-2”, каждый из которых состоял из 14 призм. Использование первого из этих отражателей обладает незаурядной историей. За первые 6 месяцев работы лунохода с отражателем удалось провести около 20 сеансов лазерной локации. Однако затем из-за неудачного положения лунохода вплоть до 2010 года не удавалось использовать отражатель. Лишь снимки нового аппарата LRO помогли уточнить положение лунохода с отражателем, и тем самым возобновить сеансы работы с ним.

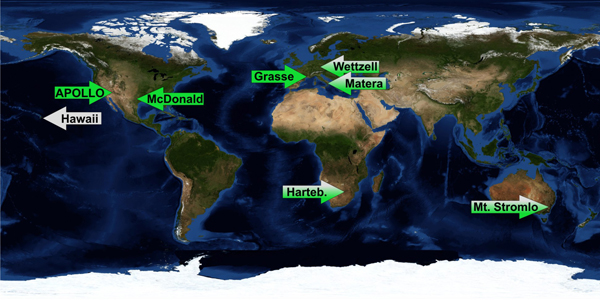

В СССР наибольшее количество сеансов лазерной локации было проведено на 2.6-метровом телескопе Крымской обсерватории. Между 1976 и 1983 годами на этом телескопе было проведено 1400 измерений с погрешностью в 25 сантиметров, затем наблюдения были прекращены в связи со свертыванием советской лунной программы.

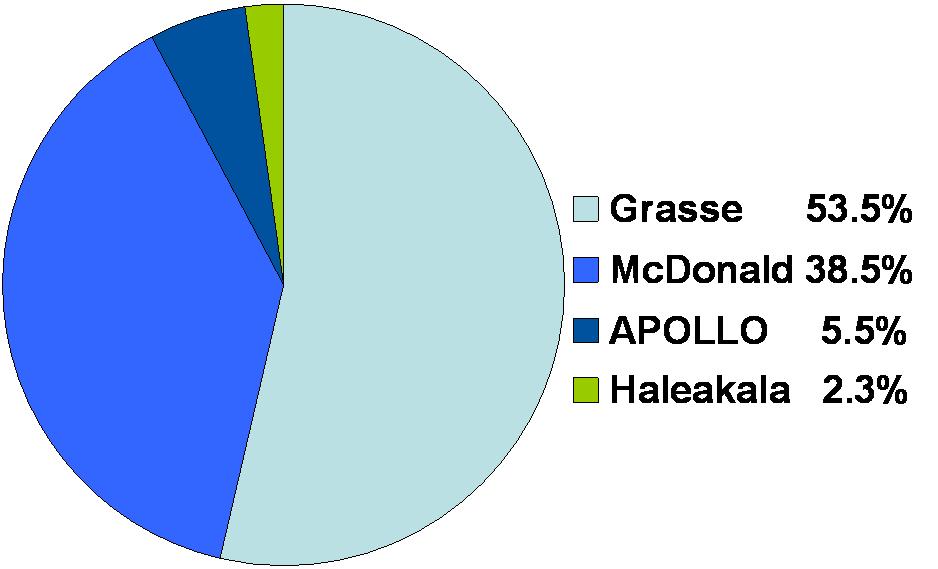

Всего же с 1970 по 2010 годы в мире было проведено примерно 17 тысяч высокоточных сеансов лазерной локации. Большинство из них было связано с уголковым отражателем “Аполонна-15” (как говорилось выше, он является наиболее совершенным – с рекордным количеством призм):

В то же время наиболее точные измерения выполняет инструмент APOLLO, который был установлен на 3.5-метровом телескопе обсерватории Апач Пойнт в 2006 году. Точность его измерений достигает одного миллиметра:

Эволюция системы Луна и Земля

Эволюция системы Луна и Земля

Главной целью всё более точных измерений расстояния до Луны являются попытки более глубокого понимания эволюции орбиты Луны в далеком прошлом и в отдаленном будущем. К настоящему времени астрономы пришли к выводу, что в прошлом Луна находилась в несколько раз ближе к Земле, а так же обладала значительно более коротким периодом вращения (то есть не была приливно захваченной). Этот факт подтверждает импактную версию образования Луны из выброшенного вещества Земли, которая преобладает в наше время. Кроме того, приливное воздействие Луны приводит к тому, что скорость вращения Земли вокруг своей оси постепенно замедляется. Скорость этого процесса составляет увеличение земных суток каждый год на 23 микросекунды. За один год Луна отдаляется от Земли в среднем на 38 миллиметров. Оценивается, что в случае если система Земля-Луна переживет превращение Солнца в красный гигант, то через 50 миллиардов лет земные сутки сравняются с лунным месяцем. В результате Луна и Земля будут всегда повернуты к друг другу только одной стороной, как сейчас наблюдается в системе Плутон-Харон. К этому времени Луна отдалится до, примерно, 600 тысяч километров, а лунный месяц увеличится до 47 суток. Кроме того, предполагается, что испарение земных океанов через 2.3 миллиардов лет приведет к ускорению процесса удаления Луны (земные приливы значительно тормозят процесс).

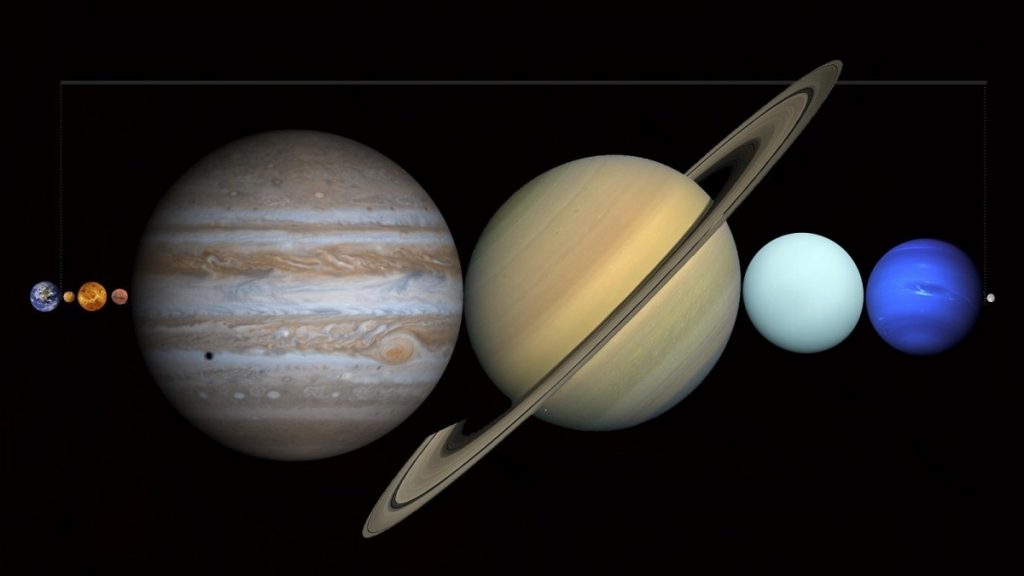

Кроме того, расчеты показывают, что в дальнейшем Луна снова начнет сближаться с Землей по причине приливного взаимодействия с друг другом. При приближении к Земле на 12 тысяч км Луна будет разорвана приливными силами, обломки Луны образуют кольцо наподобие известных колец вокруг планет-гигантов Солнечной Системы. Другие известные спутники Солнечной Системы повторят эту судьбу гораздо раньше. Так Фобосу отводят 20-40 миллионов лет, а Тритону около 2 миллиардов лет.

Интересные факты

Между Землей и Луной можно поместить все остальные планеты Солнечной системы

Каждый год расстояние до земного спутника возрастает в среднем на 4 см. Причины – движение планетоида по спиральной орбите и постепенно падающая мощность гравитационного взаимодействия Земли и Луны.

Между Землей и Луной теоретически можно разместить все планеты Солнечной системы. Если сложить диаметры всех планет, включая Плутон, то получится величина в 382 100 км.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Lunar distance | |

|---|---|

A lunar distance, 384,399 km (238,854 mi), is the Moon’s average distance to Earth. The actual distance varies over the course of its orbit. The image compares the Moon’s apparent size when it is nearest and farthest from Earth. |

|

| General information | |

| Unit system | astronomy |

| Unit of | distance |

| Symbol | LD or  |

| Conversions | |

| 1 LD in … | … is equal to … |

| SI base unit | 384399×103 m |

| Metric system | 384399 km |

| English units | 238854 mi |

| Astronomical unit | 0.002569 au |

The instantaneous Earth–Moon distance, or distance to the Moon, is the distance from the center of Earth to the center of the Moon. Lunar distance (LD or

The semi-major axis has a value of 384,399 km (238,854 mi).[1][2] The time-averaged distance between the centers of Earth and the Moon is 385,000.6 km (239,228.3 mi). The actual distance varies over the course of the orbit of the Moon, from 356,500 km (221,500 mi) at the perigee to 406,700 km (252,700 mi) at apogee, resulting in a differential range of 50,200 km (31,200 mi).[3]

Lunar distance is commonly used to express the distance to near-Earth object encounters.[4] Lunar semi-major axis is an important astronomical datum; the few millimeter precision of the range measurements determines semi-major axis to a few decimeters; it has implications for testing gravitational theories such as general relativity,[5] and for refining other astronomical values, such as the mass,[6] radius,[7] and rotation of Earth.[8] The measurement is also useful in characterizing the lunar radius, as well as the mass of and distance to the Sun.

Millimeter-precision measurements of the lunar distance are made by measuring the time taken for laser beam light to travel between stations on Earth and retroreflectors placed on the Moon. The Moon is spiraling away from Earth at an average rate of 3.8 cm (1.5 in) per year, as detected by the Lunar Laser Ranging experiment.[9][10][11]

Value[edit]

| Unit | Mean value | Uncertainty | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| meter | 3.84399×108 | 1.1 mm | [1] |

| kilometer | 384,399 | 1.1 mm | [1] |

| mile | 238,854 | 0.043 in | [1] |

| Earth radius | 60.32 | [12] | |

| AU | 1/388.6 = 0.00257 | [13][14] | |

| light-second | 1.282 | 37.5×10−12 | [1] |

- An AU is 389 Lunar distances.[15]

- A lightyear is 24,611,700 Lunar distances.[15][16]

- Geostationary Earth Orbit is 42,164 km (26,199 mi) from Earth center, or 1/9.117 LD = 0.10968 LD

Variation[edit]

The instantaneous lunar distance is constantly changing. In fact the true distance between the Moon and Earth can change as quickly as 75 meters per second,[3] or more than 1,000 km (620 mi) in just 6 hours, due to its non-circular orbit.[17] There are other effects that also influence the lunar distance. Some factors are described in this section.

Minimum, mean and maximum distances of the Moon from Earth with its angular diameter as seen from Earth’s surface, to scale

Perturbations and eccentricity[edit]

The distance to the Moon can be measured to an accuracy of 2 mm over a 1-hour sampling period,[18] which results in an overall uncertainty of a decimeter for the semi-major axis. However, due to its elliptical orbit with varying eccentricity, the instantaneous distance varies with monthly periodicity. Furthermore, the distance is perturbed by the gravitational effects of various astronomical bodies – most significantly the Sun and less so Venus and Jupiter. Other forces responsible for minute perturbations are: gravitational attraction to other planets in the Solar System and to asteroids; tidal forces; and relativistic effects.[19][20] The effect of radiation pressure from the Sun contributes an amount of ±3.6 mm to the lunar distance.[18]

Although the instantaneous uncertainty is a few millimeters, the measured lunar distance can change by more than 21,000 km (13,000 mi) from the mean value throughout a typical month. These perturbations are well understood[21] and the lunar distance can be accurately modeled over thousands of years.[19]

Variation of the distance between the centers of the Moon and the Earth over 700 days.

Tidal dissipation[edit]

Through the action of tidal forces, the angular momentum of Earth’s rotation is slowly being transferred to the Moon’s orbit.[22] The result is that Earth’s rate of spin is gradually decreasing (at a rate of 2.4 milliseconds/century),[23][24][25][26] and the lunar orbit is gradually expanding. The current rate of recession is 3.830±0.008 cm per year.[21][24] However, it is believed that this rate has recently increased, as a rate of 3.8 cm/year would imply that the Moon is only 1.5 billion years old, whereas scientific consensus supports an age of about 4 billion years.[27] It is also believed that this anomalously high rate of recession may continue to accelerate.[28]

It is predicted that the lunar distance will continue to increase until (in theory) the Earth and Moon become tidally locked, as are Pluto and Charon. This would occur when the duration of the lunar orbital period equals the rotational period of Earth, which is estimated to be 47 of our current days. The two bodies would then be at equilibrium, and no further rotational energy would be exchanged. However, models predict that 50 billion years would be required to achieve this configuration,[29] which is significantly longer than the expected lifetime of the Solar System.

Orbital history[edit]

Laser measurements show that the average lunar distance is increasing, which implies that the Moon was closer in the past, and that Earth’s days were shorter. Fossil studies of mollusk shells from the Campanian era (80 million years ago) show that there were 372 days (of 23 h 33 min) per year during that time, which implies that the lunar distance was about 60.05 REarth (383,000 km or 238,000 mi).[22] There is geological evidence that the average lunar distance was about 52 REarth (332,000 km or 205,000 mi) during the Precambrian Era; 2500 million years BP.[27]

The giant impact hypothesis, a widely accepted theory, states that the Moon was created as a result of a catastrophic impact between Earth and another planet, resulting in a re-accumulation of fragments at an initial distance of 3.8 REarth (24,000 km or 15,000 mi).[30] In this theory, the initial impact is assumed to have occurred 4.5 billion years ago.[31]

History of measurement[edit]

Until the late 1950s all measurements of lunar distance were based on optical angular measurements: the earliest accurate measurement was by Hipparchus in the 2nd century BC. The space age marked a turning point when the precision of this value was much improved. During the 1950s and 1960s, there were experiments using radar, lasers, and spacecraft, conducted with the benefit of computer processing and modeling.[32]

This section is intended to illustrate some of the historically significant or otherwise interesting methods of determining the lunar distance, and is not intended to be an exhaustive or all-encompassing list.

Parallax[edit]

The oldest method of determining the lunar distance involved measuring the angle between the Moon and a chosen reference point from multiple locations, simultaneously. The synchronization can be coordinated by making measurements at a pre-determined time, or during an event which is observable to all parties. Before accurate mechanical chronometers, the synchronization event was typically a lunar eclipse, or the moment when the Moon crossed the meridian (if the observers shared the same longitude). This measurement technique is known as lunar parallax.

For increased accuracy, certain adjustments must be made, such as adjusting the measured angle to account for refraction and distortion of light passing through the atmosphere.

Lunar eclipse[edit]

Early attempts to measure the distance to the Moon exploited observations of a lunar eclipse combined with knowledge of Earth’s radius and an understanding that the Sun is much further than the Moon. By observing the geometry of a lunar eclipse, the lunar distance can be calculated using trigonometry.

The earliest accounts of attempts to measure the lunar distance using this technique were by Greek astronomer and mathematician Aristarchus of Samos in the 4th century BC[33] and later by Hipparchus, whose calculations produced a result of 59–67 REarth (376000–427000 km or 233000–265000 mi).[34] This method later found its way into the work of Ptolemy,[35] who produced a result of 64+1⁄6 REarth (409000 km or 253000 mi) at its farthest point.[36]

Meridian crossing[edit]

An expedition by French astronomer A.C.D. Crommelin observed lunar meridian transits on the same night from two different locations. Careful measurements from 1905 to 1910 measured the angle of elevation at the moment when a specific lunar crater (Mösting A) crossed the local meridian, from stations at Greenwich and at Cape of Good Hope.[37] A distance was calculated with an uncertainty of 30 km, and this remained the definitive lunar distance value for the next half century.

Occultations[edit]

By recording the instant when the Moon occults a background star, (or similarly, measuring the angle between the Moon and a background star at a predetermined moment) the lunar distance can be determined, as long as the measurements are taken from multiple locations of known separation.

Astronomers O’Keefe and Anderson calculated the lunar distance by observing four occultations from nine locations in 1952.[38] They calculated a semi-major axis of 384407.6±4.7 km (238,859.8 ± 2.9 mi). This value was refined in 1962 by Irene Fischer, who incorporated updated geodetic data to produce a value of 384403.7±2 km (238,857.4 ± 1 mi).[7]

Radar[edit]

Oscilloscope display showing the radar signal.[39] The large pulse on the left is the transmitted signal, the small pulse on the right is the return signal from the Moon. The horizontal axis is time, but is calibrated in miles. It can be seen that the measured range is 238,000 mi (383,000 km), approximately the distance from the Earth to the Moon

The distance to the moon was measured by means of radar first in 1946 as part of Project Diana.[40]

Later, an experiment was conducted in 1957 at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory that used the echo from radar signals to determine the Earth-Moon distance. Radar pulses lasting 2 μs were broadcast from a 50-foot (15 m) diameter radio dish. After the radio waves echoed off the surface of the Moon, the return signal was detected and the delay time measured. From that measurement, the distance could be calculated. In practice, however, the signal-to-noise ratio was so low that an accurate measurement could not be reliably produced.[41]

The experiment was repeated in 1958 at the Royal Radar Establishment, in England. Radar pulses lasting 5 μs were transmitted with a peak power of 2 megawatts, at a repetition rate of 260 pulses per second. After the radio waves echoed off the surface of the Moon, the return signal was detected and the delay time measured. Multiple signals were added together to obtain a reliable signal by superimposing oscilloscope traces onto photographic film. From the measurements, the distance was calculated with an uncertainty of 1.25 km (0.777 mi).[42]

These initial experiments were intended to be proof-of-concept experiments and only lasted one day. Follow-on experiments lasting one month produced a semi-major axis of 384402±1.2 km (238,856 ± 0.75 mi),[43] which was the most precise measurement of the lunar distance at the time.

Laser ranging[edit]

Lunar Laser Ranging Experiment from the Apollo 11 mission

An experiment which measured the round-trip time of flight of laser pulses reflected directly off the surface of the Moon was performed in 1962, by a team from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and a Soviet team at the Crimean Astrophysical Observatory.[44]

During the Apollo missions in 1969, astronauts placed retroreflectors on the surface of the Moon for the purpose of refining the accuracy and precision of this technique. The measurements are ongoing and involve multiple laser facilities. The instantaneous precision of the Lunar Laser Ranging experiments can achieve few millimeter resolution, and is the most reliable method of determining the lunar distance to date. The semi-major axis is determined to be 384,399.0 km.[2]

Amateur astronomers and citizen scientists[edit]

Due to the modern accessibility of accurate timing devices, high resolution digital cameras, GPS receivers, powerful computers and near-instantaneous communication, it has become possible for amateur astronomers to make high accuracy measurements of the lunar distance.

On May 23, 2007, digital photographs of the Moon during a near-occultation of Regulus were taken from two locations, in Greece and England. By measuring the parallax between the Moon and the chosen background star, the lunar distance was calculated.[45]

A more ambitious project called the «Aristarchus Campaign» was conducted during the lunar eclipse of 15 April 2014.[17] During this event, participants were invited to record a series of five digital photographs from moonrise until culmination (the point of greatest altitude).

The method took advantage of the fact that the Moon is actually closest to an observer when it is at its highest point in the sky, compared to when it is on the horizon. Although it appears that the Moon is biggest when it is near the horizon, the opposite is true. This phenomenon is known as the Moon illusion. The reason for the difference in distance is that the distance from the center of the Moon to the center of the Earth is nearly constant throughout the night, but an observer on the surface of Earth is actually 1 Earth radius from the center of Earth. This offset brings them closest to the Moon when it is overhead.

Modern cameras have now reached a resolution level capable of capturing the Moon with enough precision to perceive and more importantly to measure this tiny variation in apparent size. The results of this experiment were calculated as LD = 60.51+3.91

−4.19 REarth. The accepted value for that night was 60.61 REarth, which implied a 3% accuracy. The benefit of this method is that the only measuring equipment needed is a modern digital camera (equipped with an accurate clock, and a GPS receiver).

Other experimental methods of measuring the lunar distance that can be performed by amateur astronomers involve:

- Taking pictures of the Moon before it enters the penumbra and after it is completely eclipsed.

- Measuring, as precisely as possible, the time of the eclipse contacts.

- Taking good pictures of the partial eclipse when the shape and size of the Earth shadow are clearly visible.

- Taking a picture of the Moon including, in the same field of view, Spica and Mars – from various locations.

See also[edit]

- Astronomical unit

- Ephemeris

- Jet Propulsion Laboratory Development Ephemeris

- Lunar Laser Ranging Experiment

- Lunar theory

- On the Sizes and Distances (Aristarchus)

- Orbit of the Moon

- Prutenic Tables of Erasmus Reinhold

- Supermoon

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Battat, J. B. R.; Murphy, T. W.; Adelberger, E. G. (January 2009). «The Apache Point Observatory Lunar Laser-ranging Operation (APOLLO): Two Years of Millimeter-Precision Measurements of the Earth-Moon Range». Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 121 (875): 29–40. Bibcode:2009PASP..121…29B. doi:10.1086/596748. JSTOR 10.1086/596748.

- ^ a b Williams, James G.; Dickey, Jean O. (2002). «Lunar geophysics, geodesy and dynamics». 13th International Workshop on Laser Ranging. Goddard Space Flight Center.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Murphy, T W (1 July 2013). «Lunar laser ranging: the millimeter challenge» (PDF). Reports on Progress in Physics. 76 (7): 2. arXiv:1309.6294. Bibcode:2013RPPh…76g6901M. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/76/7/076901. PMID 23764926. S2CID 15744316.

- ^ «NEO Earth Close Approaches». Neo.jpl.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 2014-03-07. Retrieved 2016-02-22.

- ^ Williams, J. G.; Newhall, X. X.; Dickey, J. O. (15 June 1996). «Relativity parameters determined from lunar laser ranging» (PDF). Physical Review D. 53 (12): 6730–6739. Bibcode:1996PhRvD..53.6730W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.53.6730. PMID 10019959.

- ^ Shuch, H. Paul (July 1991). «Measuring the mass of the earth: the ultimate moonbounce experiment» (PDF). Proceedings, 25th Conference of the Central States VHF Society: 25–30. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ a b Fischer, Irene (August 1962). «Parallax of the moon in terms of a world geodetic system» (PDF). The Astronomical Journal. 67: 373. Bibcode:1962AJ…..67..373F. doi:10.1086/108742.

- ^ Dickey, J. O.; Bender, P. L.; et al. (22 July 1994). «Lunar Laser Ranging: A Continuing Legacy of the Apollo Program» (PDF). Science. 265 (5171): 482–490. Bibcode:1994Sci…265..482D. doi:10.1126/science.265.5171.482. PMID 17781305. S2CID 10157934.

- ^ «Is the Moon moving away from the Earth? When was this discovered? (Intermediate) — Curious About Astronomy? Ask an Astronomer». Curious.astro.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-22.

- ^ C.D. Murray & S.F. Dermott (1999). Solar System Dynamics. Cambridge University Press. p. 184.

- ^ Dickinson, Terence (1993). From the Big Bang to Planet X. Camden East, Ontario: Camden House. pp. 79–81. ISBN 978-0-921820-71-0.

- ^ Lasater, A. Brian (2007). The dream of the West : the ancient heritage and the European achievement in map-making, navigation and science, 1487–1727. Morrisville: Lulu Enterprises. p. 185. ISBN 978-1-4303-1382-3.

- ^ Leslie, William T. Fox ; illustrated by Clare Walker (1983). At the sea’s edge : an introduction to coastal oceanography for the amateur naturalist. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. p. 101. ISBN 978-0130497833.

- ^ Williams, Dr. David R. (18 November 2015). «Planetary Fact Sheet — Ratio to Earth Values». NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ a b Groten, Erwin (1 April 2004). «Fundamental Parameters and Current (2004) Best Estimates of the Parameters of Common Relevance to Astronomy, Geodesy, and Geodynamics by Erwin Groten, IPGD, Darmstadt» (PDF). Journal of Geodesy. 77 (10–11): 724–797. Bibcode:2004JGeod..77..724.. doi:10.1007/s00190-003-0373-y. S2CID 16907886. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ «International Astronomical Union | IAU». www.iau.org. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ a b Zuluaga, Jorge I.; Figueroa, Juan C.; Ferrin, Ignacio (19 May 2014). «The simplest method to measure the geocentric lunar distance: a case of citizen science»: (page needed). arXiv:1405.4580. Bibcode:2014arXiv1405.4580Z.

- ^ a b Reasenberg, R.D.; Chandler, J.F.; et al. (2016). «Modeling and Analysis of the APOLLO Lunar Laser Ranging Data». arXiv:1608.04758 [astro-ph.IM].

- ^ a b Vitagliano, Aldo (1997). «Numerical integration for the real time production of fundamental ephemerides over a wide time span» (PDF). Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 66 (3): 293–308. Bibcode:1996CeMDA..66..293V. doi:10.1007/BF00049383. S2CID 119510653.

- ^ Park, Ryan S.; Folkner, William M.; Williams, James G.; Boggs, Dale H. (2021). «The JPL Planetary and Lunar Ephemerides DE440 and DE441». The Astronomical Journal. 161 (3): 105. Bibcode:2021AJ….161..105P. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/abd414. ISSN 1538-3881.

- ^ a b Folkner, W. M.; Williams, J. G.; et al. (February 2014). «The Planetary and Lunar Ephemerides DE430 and DE431» (PDF). The Interplanetary Network Progress Report. 42–169: 1. Bibcode:2014IPNPR.196C…1F.

- ^ a b Winter, Niels J.; Goderis, Steven; Van Malderen, Stijn J.M.; et al. (18 February 2020). «Subdaily-Scale Chemical Variability in a Rudist Shell: Implications for Rudist Paleobiology and the Cretaceous Day-Night Cycle». Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology. 35 (2). doi:10.1029/2019PA003723.

- ^ Choi, Charles Q. (19 November 2014). «Moon Facts: Fun Information About the Earth’s Moon». Space.com. TechMediaNetworks, Inc. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ a b Williams, James G.; Boggs, Dale H. (2016). «Secular tidal changes in lunar orbit and Earth rotation». Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 126 (1): 89–129. Bibcode:2016CeMDA.126…89W. doi:10.1007/s10569-016-9702-3. ISSN 1572-9478. S2CID 124256137.

- ^ Stephenson, F. R.; Morrison, L. V.; Hohenkerk, C. Y. (2016). «Measurement of the Earth’s rotation: 720 BC to AD 2015». Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 472 (2196): 20160404. Bibcode:2016RSPSA.47260404S. doi:10.1098/rspa.2016.0404. PMC 5247521. PMID 28119545.

- ^ Morrison, L. V.; Stephenson, F. R.; Hohenkerk, C. Y.; Zawilski, M. (2021). «Addendum 2020 to ‘Measurement of the Earth’s rotation: 720 BC to AD 2015». Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 477 (2246): 20200776. Bibcode:2021RSPSA.47700776M. doi:10.1098/rspa.2020.0776. S2CID 231938488.

- ^ a b Walker, James C. G.; Zahnle, Kevin J. (17 April 1986). «Lunar nodal tide and distance to the Moon during the Precambrian» (PDF). Nature. 320 (6063): 600–602. Bibcode:1986Natur.320..600W. doi:10.1038/320600a0. hdl:2027.42/62576. PMID 11540876. S2CID 4350312.

- ^ Bills, B.G. & Ray, R.D. (1999), «Lunar Orbital Evolution: A Synthesis of Recent Results», Geophysical Research Letters, 26 (19): 3045–3048, Bibcode:1999GeoRL..26.3045B, doi:10.1029/1999GL008348

- ^ Cain, Fraser (2016-04-12). «WHEN WILL EARTH LOCK TO THE MOON?». Universe Today. Universe Today. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ^ Canup, R. M. (17 October 2012). «Forming a Moon with an Earth-like Composition via a Giant Impact». Science. 338 (6110): 1052–1055. Bibcode:2012Sci…338.1052C. doi:10.1126/science.1226073. PMC 6476314. PMID 23076098.

- ^

«The Theia Hypothesis: New Evidence Emerges that Earth and Moon Were Once the Same». The Daily Galaxy. 2007-07-05. Retrieved 2013-11-13. - ^ Newhall, X.X; Standish, E.M; Williams, J. G. (Aug 1983). «DE 102 — A numerically integrated ephemeris of the moon and planets spanning forty-four centuries». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 125 (1): 150–167. Bibcode:1983A&A…125..150N. ISSN 0004-6361. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ Gutzwiller, Martin C. (1998). «Moon–Earth–Sun: The oldest three-body problem». Reviews of Modern Physics. 70 (2): 589–639. Bibcode:1998RvMP…70..589G. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.70.589.

- ^ Sheehan, William; Westfall, John (2004). The transits of Venus. Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-1-59102-175-9.

- ^ Webb, Stephen (1999), «3.2 Aristarchus, Hipparchus, and Ptolemy», Measuring the Universe: The Cosmological Distance Ladder, Springer, pp. 27–35, ISBN 978-1-85233-106-1. See in particular p. 33: «Almost everything we know about Hipparchus comes down to us by way of Ptolemy.»

- ^ Helden, Albert van (1986). Measuring the universe : cosmic dimensions from Aristarchus to Halley (Repr. ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-226-84882-2.

- ^ Fischer, Irène (7 November 2008). «The distance of the moon». Bulletin Géodésique. 71 (1): 37–63. Bibcode:1964BGeod..38…37F. doi:10.1007/BF02526081. S2CID 117060032.

- ^ O’Keefe, J. A.; Anderson, J. P. (1952). «The earth’s equatorial radius and the distance of the moon» (PDF). Astronomical Journal. 57: 108–121. Bibcode:1952AJ…..57..108O. doi:10.1086/106720.

- ^ Gootée, Tom (April 1946). «Radar reaches the moon» (PDF). Radio News. Ziff-Davis Publishing Co. 35 (4): 25–27. Bibcode:1946RaNew..35…25G. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- ^ «Project Diana hits the Moon… in 1946». SciHi Blog. 2022-01-10. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- ^ Yaplee, B. S.; Roman, N. G.; Scanlan, T. F.; Craig, K. J. (30 July – 6 August 1958). «A lunar radar study at 10-cm wavelength». Paris Symposium on Radio Astronomy. IAU Symposium no. 9 (9): 19. Bibcode:1959IAUS….9…19Y.

- ^ Hey, J. S.; Hughes, V. A. (30 July – 6 August 1958). «Radar observation of the moon at 10-cm wavelength». Paris Symposium on Radio Astronomy. 9 (9): 13–18. Bibcode:1959IAUS….9…13H. doi:10.1017/s007418090005049x.

- ^ Yaplee, B. S.; Knowles, S. H.; et al. (January 1965). «The mean distance to the Moon as determined by radar». Symposium — International Astronomical Union. 21: 2. Bibcode:1965IAUS…21…81Y. doi:10.1017/S0074180900104826.

- ^ Bender, P. L.; Currie, D. G.; Dicke, R. H.; et al. (October 19, 1973). «The Lunar Laser Ranging Experiment» (PDF). Science. 182 (4109): 229–238. Bibcode:1973Sci…182..229B. doi:10.1126/science.182.4109.229. PMID 17749298. S2CID 32027563. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ Wright, Ernie. «Overhead view of the Earth-Moon system, to scale Lunar Parallax: Estimating the Moon’s Distance». Retrieved 29 February 2016.

External links[edit]

- Wolfram Alpha widget – Current Moon Earth distance

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Lunar distance | |

|---|---|

A lunar distance, 384,399 km (238,854 mi), is the Moon’s average distance to Earth. The actual distance varies over the course of its orbit. The image compares the Moon’s apparent size when it is nearest and farthest from Earth. |

|

| General information | |

| Unit system | astronomy |

| Unit of | distance |

| Symbol | LD or  |

| Conversions | |

| 1 LD in … | … is equal to … |

| SI base unit | 384399×103 m |

| Metric system | 384399 km |

| English units | 238854 mi |

| Astronomical unit | 0.002569 au |

The instantaneous Earth–Moon distance, or distance to the Moon, is the distance from the center of Earth to the center of the Moon. Lunar distance (LD or

The semi-major axis has a value of 384,399 km (238,854 mi).[1][2] The time-averaged distance between the centers of Earth and the Moon is 385,000.6 km (239,228.3 mi). The actual distance varies over the course of the orbit of the Moon, from 356,500 km (221,500 mi) at the perigee to 406,700 km (252,700 mi) at apogee, resulting in a differential range of 50,200 km (31,200 mi).[3]

Lunar distance is commonly used to express the distance to near-Earth object encounters.[4] Lunar semi-major axis is an important astronomical datum; the few millimeter precision of the range measurements determines semi-major axis to a few decimeters; it has implications for testing gravitational theories such as general relativity,[5] and for refining other astronomical values, such as the mass,[6] radius,[7] and rotation of Earth.[8] The measurement is also useful in characterizing the lunar radius, as well as the mass of and distance to the Sun.

Millimeter-precision measurements of the lunar distance are made by measuring the time taken for laser beam light to travel between stations on Earth and retroreflectors placed on the Moon. The Moon is spiraling away from Earth at an average rate of 3.8 cm (1.5 in) per year, as detected by the Lunar Laser Ranging experiment.[9][10][11]

Value[edit]

| Unit | Mean value | Uncertainty | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| meter | 3.84399×108 | 1.1 mm | [1] |

| kilometer | 384,399 | 1.1 mm | [1] |

| mile | 238,854 | 0.043 in | [1] |

| Earth radius | 60.32 | [12] | |

| AU | 1/388.6 = 0.00257 | [13][14] | |

| light-second | 1.282 | 37.5×10−12 | [1] |

- An AU is 389 Lunar distances.[15]

- A lightyear is 24,611,700 Lunar distances.[15][16]

- Geostationary Earth Orbit is 42,164 km (26,199 mi) from Earth center, or 1/9.117 LD = 0.10968 LD

Variation[edit]

The instantaneous lunar distance is constantly changing. In fact the true distance between the Moon and Earth can change as quickly as 75 meters per second,[3] or more than 1,000 km (620 mi) in just 6 hours, due to its non-circular orbit.[17] There are other effects that also influence the lunar distance. Some factors are described in this section.

Minimum, mean and maximum distances of the Moon from Earth with its angular diameter as seen from Earth’s surface, to scale

Perturbations and eccentricity[edit]

The distance to the Moon can be measured to an accuracy of 2 mm over a 1-hour sampling period,[18] which results in an overall uncertainty of a decimeter for the semi-major axis. However, due to its elliptical orbit with varying eccentricity, the instantaneous distance varies with monthly periodicity. Furthermore, the distance is perturbed by the gravitational effects of various astronomical bodies – most significantly the Sun and less so Venus and Jupiter. Other forces responsible for minute perturbations are: gravitational attraction to other planets in the Solar System and to asteroids; tidal forces; and relativistic effects.[19][20] The effect of radiation pressure from the Sun contributes an amount of ±3.6 mm to the lunar distance.[18]

Although the instantaneous uncertainty is a few millimeters, the measured lunar distance can change by more than 21,000 km (13,000 mi) from the mean value throughout a typical month. These perturbations are well understood[21] and the lunar distance can be accurately modeled over thousands of years.[19]

Variation of the distance between the centers of the Moon and the Earth over 700 days.

Tidal dissipation[edit]

Through the action of tidal forces, the angular momentum of Earth’s rotation is slowly being transferred to the Moon’s orbit.[22] The result is that Earth’s rate of spin is gradually decreasing (at a rate of 2.4 milliseconds/century),[23][24][25][26] and the lunar orbit is gradually expanding. The current rate of recession is 3.830±0.008 cm per year.[21][24] However, it is believed that this rate has recently increased, as a rate of 3.8 cm/year would imply that the Moon is only 1.5 billion years old, whereas scientific consensus supports an age of about 4 billion years.[27] It is also believed that this anomalously high rate of recession may continue to accelerate.[28]

It is predicted that the lunar distance will continue to increase until (in theory) the Earth and Moon become tidally locked, as are Pluto and Charon. This would occur when the duration of the lunar orbital period equals the rotational period of Earth, which is estimated to be 47 of our current days. The two bodies would then be at equilibrium, and no further rotational energy would be exchanged. However, models predict that 50 billion years would be required to achieve this configuration,[29] which is significantly longer than the expected lifetime of the Solar System.

Orbital history[edit]

Laser measurements show that the average lunar distance is increasing, which implies that the Moon was closer in the past, and that Earth’s days were shorter. Fossil studies of mollusk shells from the Campanian era (80 million years ago) show that there were 372 days (of 23 h 33 min) per year during that time, which implies that the lunar distance was about 60.05 REarth (383,000 km or 238,000 mi).[22] There is geological evidence that the average lunar distance was about 52 REarth (332,000 km or 205,000 mi) during the Precambrian Era; 2500 million years BP.[27]

The giant impact hypothesis, a widely accepted theory, states that the Moon was created as a result of a catastrophic impact between Earth and another planet, resulting in a re-accumulation of fragments at an initial distance of 3.8 REarth (24,000 km or 15,000 mi).[30] In this theory, the initial impact is assumed to have occurred 4.5 billion years ago.[31]

History of measurement[edit]

Until the late 1950s all measurements of lunar distance were based on optical angular measurements: the earliest accurate measurement was by Hipparchus in the 2nd century BC. The space age marked a turning point when the precision of this value was much improved. During the 1950s and 1960s, there were experiments using radar, lasers, and spacecraft, conducted with the benefit of computer processing and modeling.[32]

This section is intended to illustrate some of the historically significant or otherwise interesting methods of determining the lunar distance, and is not intended to be an exhaustive or all-encompassing list.

Parallax[edit]

The oldest method of determining the lunar distance involved measuring the angle between the Moon and a chosen reference point from multiple locations, simultaneously. The synchronization can be coordinated by making measurements at a pre-determined time, or during an event which is observable to all parties. Before accurate mechanical chronometers, the synchronization event was typically a lunar eclipse, or the moment when the Moon crossed the meridian (if the observers shared the same longitude). This measurement technique is known as lunar parallax.

For increased accuracy, certain adjustments must be made, such as adjusting the measured angle to account for refraction and distortion of light passing through the atmosphere.

Lunar eclipse[edit]

Early attempts to measure the distance to the Moon exploited observations of a lunar eclipse combined with knowledge of Earth’s radius and an understanding that the Sun is much further than the Moon. By observing the geometry of a lunar eclipse, the lunar distance can be calculated using trigonometry.

The earliest accounts of attempts to measure the lunar distance using this technique were by Greek astronomer and mathematician Aristarchus of Samos in the 4th century BC[33] and later by Hipparchus, whose calculations produced a result of 59–67 REarth (376000–427000 km or 233000–265000 mi).[34] This method later found its way into the work of Ptolemy,[35] who produced a result of 64+1⁄6 REarth (409000 km or 253000 mi) at its farthest point.[36]

Meridian crossing[edit]

An expedition by French astronomer A.C.D. Crommelin observed lunar meridian transits on the same night from two different locations. Careful measurements from 1905 to 1910 measured the angle of elevation at the moment when a specific lunar crater (Mösting A) crossed the local meridian, from stations at Greenwich and at Cape of Good Hope.[37] A distance was calculated with an uncertainty of 30 km, and this remained the definitive lunar distance value for the next half century.

Occultations[edit]

By recording the instant when the Moon occults a background star, (or similarly, measuring the angle between the Moon and a background star at a predetermined moment) the lunar distance can be determined, as long as the measurements are taken from multiple locations of known separation.

Astronomers O’Keefe and Anderson calculated the lunar distance by observing four occultations from nine locations in 1952.[38] They calculated a semi-major axis of 384407.6±4.7 km (238,859.8 ± 2.9 mi). This value was refined in 1962 by Irene Fischer, who incorporated updated geodetic data to produce a value of 384403.7±2 km (238,857.4 ± 1 mi).[7]

Radar[edit]

Oscilloscope display showing the radar signal.[39] The large pulse on the left is the transmitted signal, the small pulse on the right is the return signal from the Moon. The horizontal axis is time, but is calibrated in miles. It can be seen that the measured range is 238,000 mi (383,000 km), approximately the distance from the Earth to the Moon

The distance to the moon was measured by means of radar first in 1946 as part of Project Diana.[40]

Later, an experiment was conducted in 1957 at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory that used the echo from radar signals to determine the Earth-Moon distance. Radar pulses lasting 2 μs were broadcast from a 50-foot (15 m) diameter radio dish. After the radio waves echoed off the surface of the Moon, the return signal was detected and the delay time measured. From that measurement, the distance could be calculated. In practice, however, the signal-to-noise ratio was so low that an accurate measurement could not be reliably produced.[41]

The experiment was repeated in 1958 at the Royal Radar Establishment, in England. Radar pulses lasting 5 μs were transmitted with a peak power of 2 megawatts, at a repetition rate of 260 pulses per second. After the radio waves echoed off the surface of the Moon, the return signal was detected and the delay time measured. Multiple signals were added together to obtain a reliable signal by superimposing oscilloscope traces onto photographic film. From the measurements, the distance was calculated with an uncertainty of 1.25 km (0.777 mi).[42]

These initial experiments were intended to be proof-of-concept experiments and only lasted one day. Follow-on experiments lasting one month produced a semi-major axis of 384402±1.2 km (238,856 ± 0.75 mi),[43] which was the most precise measurement of the lunar distance at the time.

Laser ranging[edit]

Lunar Laser Ranging Experiment from the Apollo 11 mission

An experiment which measured the round-trip time of flight of laser pulses reflected directly off the surface of the Moon was performed in 1962, by a team from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and a Soviet team at the Crimean Astrophysical Observatory.[44]

During the Apollo missions in 1969, astronauts placed retroreflectors on the surface of the Moon for the purpose of refining the accuracy and precision of this technique. The measurements are ongoing and involve multiple laser facilities. The instantaneous precision of the Lunar Laser Ranging experiments can achieve few millimeter resolution, and is the most reliable method of determining the lunar distance to date. The semi-major axis is determined to be 384,399.0 km.[2]

Amateur astronomers and citizen scientists[edit]

Due to the modern accessibility of accurate timing devices, high resolution digital cameras, GPS receivers, powerful computers and near-instantaneous communication, it has become possible for amateur astronomers to make high accuracy measurements of the lunar distance.

On May 23, 2007, digital photographs of the Moon during a near-occultation of Regulus were taken from two locations, in Greece and England. By measuring the parallax between the Moon and the chosen background star, the lunar distance was calculated.[45]

A more ambitious project called the «Aristarchus Campaign» was conducted during the lunar eclipse of 15 April 2014.[17] During this event, participants were invited to record a series of five digital photographs from moonrise until culmination (the point of greatest altitude).

The method took advantage of the fact that the Moon is actually closest to an observer when it is at its highest point in the sky, compared to when it is on the horizon. Although it appears that the Moon is biggest when it is near the horizon, the opposite is true. This phenomenon is known as the Moon illusion. The reason for the difference in distance is that the distance from the center of the Moon to the center of the Earth is nearly constant throughout the night, but an observer on the surface of Earth is actually 1 Earth radius from the center of Earth. This offset brings them closest to the Moon when it is overhead.

Modern cameras have now reached a resolution level capable of capturing the Moon with enough precision to perceive and more importantly to measure this tiny variation in apparent size. The results of this experiment were calculated as LD = 60.51+3.91

−4.19 REarth. The accepted value for that night was 60.61 REarth, which implied a 3% accuracy. The benefit of this method is that the only measuring equipment needed is a modern digital camera (equipped with an accurate clock, and a GPS receiver).

Other experimental methods of measuring the lunar distance that can be performed by amateur astronomers involve:

- Taking pictures of the Moon before it enters the penumbra and after it is completely eclipsed.

- Measuring, as precisely as possible, the time of the eclipse contacts.

- Taking good pictures of the partial eclipse when the shape and size of the Earth shadow are clearly visible.

- Taking a picture of the Moon including, in the same field of view, Spica and Mars – from various locations.

See also[edit]

- Astronomical unit

- Ephemeris

- Jet Propulsion Laboratory Development Ephemeris

- Lunar Laser Ranging Experiment

- Lunar theory

- On the Sizes and Distances (Aristarchus)

- Orbit of the Moon

- Prutenic Tables of Erasmus Reinhold

- Supermoon

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Battat, J. B. R.; Murphy, T. W.; Adelberger, E. G. (January 2009). «The Apache Point Observatory Lunar Laser-ranging Operation (APOLLO): Two Years of Millimeter-Precision Measurements of the Earth-Moon Range». Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 121 (875): 29–40. Bibcode:2009PASP..121…29B. doi:10.1086/596748. JSTOR 10.1086/596748.

- ^ a b Williams, James G.; Dickey, Jean O. (2002). «Lunar geophysics, geodesy and dynamics». 13th International Workshop on Laser Ranging. Goddard Space Flight Center.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Murphy, T W (1 July 2013). «Lunar laser ranging: the millimeter challenge» (PDF). Reports on Progress in Physics. 76 (7): 2. arXiv:1309.6294. Bibcode:2013RPPh…76g6901M. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/76/7/076901. PMID 23764926. S2CID 15744316.

- ^ «NEO Earth Close Approaches». Neo.jpl.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 2014-03-07. Retrieved 2016-02-22.

- ^ Williams, J. G.; Newhall, X. X.; Dickey, J. O. (15 June 1996). «Relativity parameters determined from lunar laser ranging» (PDF). Physical Review D. 53 (12): 6730–6739. Bibcode:1996PhRvD..53.6730W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.53.6730. PMID 10019959.

- ^ Shuch, H. Paul (July 1991). «Measuring the mass of the earth: the ultimate moonbounce experiment» (PDF). Proceedings, 25th Conference of the Central States VHF Society: 25–30. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ a b Fischer, Irene (August 1962). «Parallax of the moon in terms of a world geodetic system» (PDF). The Astronomical Journal. 67: 373. Bibcode:1962AJ…..67..373F. doi:10.1086/108742.

- ^ Dickey, J. O.; Bender, P. L.; et al. (22 July 1994). «Lunar Laser Ranging: A Continuing Legacy of the Apollo Program» (PDF). Science. 265 (5171): 482–490. Bibcode:1994Sci…265..482D. doi:10.1126/science.265.5171.482. PMID 17781305. S2CID 10157934.

- ^ «Is the Moon moving away from the Earth? When was this discovered? (Intermediate) — Curious About Astronomy? Ask an Astronomer». Curious.astro.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-22.

- ^ C.D. Murray & S.F. Dermott (1999). Solar System Dynamics. Cambridge University Press. p. 184.

- ^ Dickinson, Terence (1993). From the Big Bang to Planet X. Camden East, Ontario: Camden House. pp. 79–81. ISBN 978-0-921820-71-0.

- ^ Lasater, A. Brian (2007). The dream of the West : the ancient heritage and the European achievement in map-making, navigation and science, 1487–1727. Morrisville: Lulu Enterprises. p. 185. ISBN 978-1-4303-1382-3.

- ^ Leslie, William T. Fox ; illustrated by Clare Walker (1983). At the sea’s edge : an introduction to coastal oceanography for the amateur naturalist. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. p. 101. ISBN 978-0130497833.

- ^ Williams, Dr. David R. (18 November 2015). «Planetary Fact Sheet — Ratio to Earth Values». NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ a b Groten, Erwin (1 April 2004). «Fundamental Parameters and Current (2004) Best Estimates of the Parameters of Common Relevance to Astronomy, Geodesy, and Geodynamics by Erwin Groten, IPGD, Darmstadt» (PDF). Journal of Geodesy. 77 (10–11): 724–797. Bibcode:2004JGeod..77..724.. doi:10.1007/s00190-003-0373-y. S2CID 16907886. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ «International Astronomical Union | IAU». www.iau.org. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ a b Zuluaga, Jorge I.; Figueroa, Juan C.; Ferrin, Ignacio (19 May 2014). «The simplest method to measure the geocentric lunar distance: a case of citizen science»: (page needed). arXiv:1405.4580. Bibcode:2014arXiv1405.4580Z.

- ^ a b Reasenberg, R.D.; Chandler, J.F.; et al. (2016). «Modeling and Analysis of the APOLLO Lunar Laser Ranging Data». arXiv:1608.04758 [astro-ph.IM].

- ^ a b Vitagliano, Aldo (1997). «Numerical integration for the real time production of fundamental ephemerides over a wide time span» (PDF). Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 66 (3): 293–308. Bibcode:1996CeMDA..66..293V. doi:10.1007/BF00049383. S2CID 119510653.

- ^ Park, Ryan S.; Folkner, William M.; Williams, James G.; Boggs, Dale H. (2021). «The JPL Planetary and Lunar Ephemerides DE440 and DE441». The Astronomical Journal. 161 (3): 105. Bibcode:2021AJ….161..105P. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/abd414. ISSN 1538-3881.

- ^ a b Folkner, W. M.; Williams, J. G.; et al. (February 2014). «The Planetary and Lunar Ephemerides DE430 and DE431» (PDF). The Interplanetary Network Progress Report. 42–169: 1. Bibcode:2014IPNPR.196C…1F.

- ^ a b Winter, Niels J.; Goderis, Steven; Van Malderen, Stijn J.M.; et al. (18 February 2020). «Subdaily-Scale Chemical Variability in a Rudist Shell: Implications for Rudist Paleobiology and the Cretaceous Day-Night Cycle». Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology. 35 (2). doi:10.1029/2019PA003723.

- ^ Choi, Charles Q. (19 November 2014). «Moon Facts: Fun Information About the Earth’s Moon». Space.com. TechMediaNetworks, Inc. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ a b Williams, James G.; Boggs, Dale H. (2016). «Secular tidal changes in lunar orbit and Earth rotation». Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 126 (1): 89–129. Bibcode:2016CeMDA.126…89W. doi:10.1007/s10569-016-9702-3. ISSN 1572-9478. S2CID 124256137.

- ^ Stephenson, F. R.; Morrison, L. V.; Hohenkerk, C. Y. (2016). «Measurement of the Earth’s rotation: 720 BC to AD 2015». Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 472 (2196): 20160404. Bibcode:2016RSPSA.47260404S. doi:10.1098/rspa.2016.0404. PMC 5247521. PMID 28119545.

- ^ Morrison, L. V.; Stephenson, F. R.; Hohenkerk, C. Y.; Zawilski, M. (2021). «Addendum 2020 to ‘Measurement of the Earth’s rotation: 720 BC to AD 2015». Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 477 (2246): 20200776. Bibcode:2021RSPSA.47700776M. doi:10.1098/rspa.2020.0776. S2CID 231938488.

- ^ a b Walker, James C. G.; Zahnle, Kevin J. (17 April 1986). «Lunar nodal tide and distance to the Moon during the Precambrian» (PDF). Nature. 320 (6063): 600–602. Bibcode:1986Natur.320..600W. doi:10.1038/320600a0. hdl:2027.42/62576. PMID 11540876. S2CID 4350312.

- ^ Bills, B.G. & Ray, R.D. (1999), «Lunar Orbital Evolution: A Synthesis of Recent Results», Geophysical Research Letters, 26 (19): 3045–3048, Bibcode:1999GeoRL..26.3045B, doi:10.1029/1999GL008348

- ^ Cain, Fraser (2016-04-12). «WHEN WILL EARTH LOCK TO THE MOON?». Universe Today. Universe Today. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ^ Canup, R. M. (17 October 2012). «Forming a Moon with an Earth-like Composition via a Giant Impact». Science. 338 (6110): 1052–1055. Bibcode:2012Sci…338.1052C. doi:10.1126/science.1226073. PMC 6476314. PMID 23076098.

- ^

«The Theia Hypothesis: New Evidence Emerges that Earth and Moon Were Once the Same». The Daily Galaxy. 2007-07-05. Retrieved 2013-11-13. - ^ Newhall, X.X; Standish, E.M; Williams, J. G. (Aug 1983). «DE 102 — A numerically integrated ephemeris of the moon and planets spanning forty-four centuries». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 125 (1): 150–167. Bibcode:1983A&A…125..150N. ISSN 0004-6361. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ Gutzwiller, Martin C. (1998). «Moon–Earth–Sun: The oldest three-body problem». Reviews of Modern Physics. 70 (2): 589–639. Bibcode:1998RvMP…70..589G. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.70.589.

- ^ Sheehan, William; Westfall, John (2004). The transits of Venus. Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-1-59102-175-9.

- ^ Webb, Stephen (1999), «3.2 Aristarchus, Hipparchus, and Ptolemy», Measuring the Universe: The Cosmological Distance Ladder, Springer, pp. 27–35, ISBN 978-1-85233-106-1. See in particular p. 33: «Almost everything we know about Hipparchus comes down to us by way of Ptolemy.»

- ^ Helden, Albert van (1986). Measuring the universe : cosmic dimensions from Aristarchus to Halley (Repr. ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-226-84882-2.

- ^ Fischer, Irène (7 November 2008). «The distance of the moon». Bulletin Géodésique. 71 (1): 37–63. Bibcode:1964BGeod..38…37F. doi:10.1007/BF02526081. S2CID 117060032.

- ^ O’Keefe, J. A.; Anderson, J. P. (1952). «The earth’s equatorial radius and the distance of the moon» (PDF). Astronomical Journal. 57: 108–121. Bibcode:1952AJ…..57..108O. doi:10.1086/106720.

- ^ Gootée, Tom (April 1946). «Radar reaches the moon» (PDF). Radio News. Ziff-Davis Publishing Co. 35 (4): 25–27. Bibcode:1946RaNew..35…25G. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- ^ «Project Diana hits the Moon… in 1946». SciHi Blog. 2022-01-10. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- ^ Yaplee, B. S.; Roman, N. G.; Scanlan, T. F.; Craig, K. J. (30 July – 6 August 1958). «A lunar radar study at 10-cm wavelength». Paris Symposium on Radio Astronomy. IAU Symposium no. 9 (9): 19. Bibcode:1959IAUS….9…19Y.

- ^ Hey, J. S.; Hughes, V. A. (30 July – 6 August 1958). «Radar observation of the moon at 10-cm wavelength». Paris Symposium on Radio Astronomy. 9 (9): 13–18. Bibcode:1959IAUS….9…13H. doi:10.1017/s007418090005049x.

- ^ Yaplee, B. S.; Knowles, S. H.; et al. (January 1965). «The mean distance to the Moon as determined by radar». Symposium — International Astronomical Union. 21: 2. Bibcode:1965IAUS…21…81Y. doi:10.1017/S0074180900104826.

- ^ Bender, P. L.; Currie, D. G.; Dicke, R. H.; et al. (October 19, 1973). «The Lunar Laser Ranging Experiment» (PDF). Science. 182 (4109): 229–238. Bibcode:1973Sci…182..229B. doi:10.1126/science.182.4109.229. PMID 17749298. S2CID 32027563. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ Wright, Ernie. «Overhead view of the Earth-Moon system, to scale Lunar Parallax: Estimating the Moon’s Distance». Retrieved 29 February 2016.

External links[edit]

- Wolfram Alpha widget – Current Moon Earth distance

Человечество с давних времен интересуется космосом и возможностью открытия новых миров. Для многих жителей планеты Земля остается актуальным вопрос, сколько времени лететь до луны. Обо всех интересных фактах расскажет статья.

Содержание

- Расстояние от Земли до Луны

- От чего зависит движение луны

- Чему равно расстояние от Земли до Луны

- Как в древней Греции астрономы рассчитывали расстояние до Луны

- Эволюция методик измерения расстояния до Луны

- Сколько по времени лететь до Луны на ракете

- История полетов на Луну

- Аппараты, способные долететь до Луны

- Технические характеристики

- Почему теперь не летают на Луну

Расстояние от Земли до Луны

Луна является единственным и естественным спутником Земли с незапамятных времен. Также считается самым близким небесным телом к планете. Поэтому большинство людей интересуются, на каком расстоянии луна от земли, на чем можно долететь и сколько займет по времени такое космическое путешествие.

Теоретически, расстояние можно измерить от центра Земли до центра Луны. Но методы измерения, используемые в повседневной жизни, для этого не подходят. Неверно считать расстояние до луны константой, так как оно может меняться в зависимости от времени измерения. Но, несмотря на это, величина имеет два крайних значения – перигей и апогей.

От чего зависит движение луны

Важно отметить в первую очередь, что орбита Луны не является стабильной и неизменной. Происходит это потому что, масса спутника небольшая, и на него действуют постоянные возмущения от более крупных объектов Солнечной Системы.

Орбита Луны также подвержена влиянию со стороны гравитационных полей других планет. В результате этих воздействий на орбите луны происходят колебания между 0.04 и 0.07, периодически каждые 9 лет. Именно поэтому человечество может наблюдать такое явление, как суперлуние.

Важно! Форма орбиты спутника и постоянно уменьшающегося гравитационного поля между Землей и Луной, увеличивает расстояние на 4 сантиметра каждый год.

Чему равно расстояние от Земли до Луны

Чтобы космическим кораблям добраться до луны, потребуется очень много времени. Но при этом свет способен преодолеет расстояние от Земли до Луны всего за 1,255 секунд. Теоретически, на космическом корабле до Луны можно добраться примерно за 10 часов, при условии, что скорость будет 11 км/с.

На самом деле путь займет дольше времени, так как по прямой лететь не получится, и нужно постоянно корректировать путь. Луна находится на расстоянии от Земли в 380 тысяч километров. Но это приблизительная величина, так как значения периодически изменяются.

- Перигей – является ближайшей точкой к Земле, сквозь которую проходит траектория Луны. Расстояние до этой точки составляет 367 047 километров.

- Апогей – дальняя точка траектории, расстояние до которой составляет 405 696 километров.

Как в древней Греции астрономы рассчитывали расстояние до Луны

Принято считать, что древнегреческие астрономы первыми вычислили расстояние до спутника Земли. Аристарх Самосский является первым человеком, который попытался измерить расстояние от Земли до Луны. Он рассчитал, что угол между планетой и ее спутником равен 87 градусам. На самом деле этот расчет оказался неверным из-за использования древних примитивных астрономических инструментов.

Также древние астрономы вычисляли угловые диаметры по регулярным солнечным затмениям. В результате чего, был сделан вывод, что значение угловых диаметров Солнца и Луны практически одинаковые. Аристарх, учитывая эти данные, посчитал, что Луна меньше Солнца в 20 раз. На самом деле спутник Земли меньше солнца примерно в 400 раз.

Эволюция методик измерения расстояния до Луны

Когда был изобретен первый телескоп, астрономы смогли более точно производить измерения. Но более точные вычисления смогли делать только когда начала развиваться радиолокация. Таким методом первые измерения были произведены в 1946 году американскими и британскими астрономами.

В 1960-х годах ученые разработали лазерную локацию, которая позволила осуществлять измерения еще точнее. Чтобы реализовать данный метод измерения, пришлось установить на Луне несколько уголковых отражателей.

Сколько по времени лететь до Луны на ракете

Узнав сколько от Земли до Луны в километрах, становится понятно, что это не такое большое расстояние, как казалось на первый взгляд. Современные космические корабли способны доставить человека на орбиту примерно за 9 часов. Что касается кораблей, серии Аполлон, с помощью которых космические просторы покорялись в 1960-х года, могли доставить человека на Луну в течение 72 часов.

Интересный факт! Если теоретически представить, что полет будет осуществляться на самолете, который развивает скорость 800 километров в час, до поверхности спутника Земли можно было бы добраться за 20 суток.

При поездке на велосипеде со скоростью 20 километров в час, до поверхности Луны можно было бы добраться примерно за 2 года.

Лучик света, направленный с Земли к спутнику способен добраться до его поверхности за доли секунды. Если бы существовали космические аппараты, способные перемещаться с такой скоростью, путешествие на другие планеты было бы более доступным.

История полетов на Луну

В 50-х годах астрономы только предполагали, какое может быть расстояние до Луны. Но позже наука все же сделала шаг к открытиям.

- 1959 год – космический аппарат СССР впервые достиг поверхности Луны. У него было исследовательское назначение без людей на борту.

- 1966 год – впервые удалось советскому космическому аппарату совершить мягкую посадку, после 4 предыдущих крушений. Нужно отметить, что до 1969 года исследователи направляли к спутнику еще 30 космических аппаратов.

- 1969 год – в июле к поверхности Луны был направлен космический корабль Аполлон-11 с людьми на борту. Через месяц состоялась еще одна экспедиция под названием Апполон-12. Тогда космический корабль осуществил вторую высадку людей на Луну.

- 1972 год – состоялась последняя высадка на Луну, которая по счету является шестой. С тех пор нога человека не ступала на поверхность спутника Земли. До настоящего времени к Луне отправляют лишь беспилотные модули, которые доставляют луноходы.

На заметку! Лишь 12 человек смогли побывать на Луне за всю историю исследования спутника Земли.

Аппараты, способные долететь до Луны

Существует несколько летательных аппаратов, а также сверхтяжелых ракет, которые могут достигнуть луны за определенный промежуток времени.

Технические характеристики

Почему теперь не летают на Луну

В 1972 году на Землю вернулся Аполлон-17, и с тех пор больше не было попыток высадки человека на Луну. Существует много версий, почему люди перестали осваивать спутник Земли. Есть мнение, что после того, как на Луну был отправлен Армстронг, СССР проиграли в космической гонке.

Также спустя некоторое время, произошли некоторые изменения в геополитической обстановке между США и Россией. Это привело к тому, что получение господства в космосе перестало быть значимым для обеих стран.

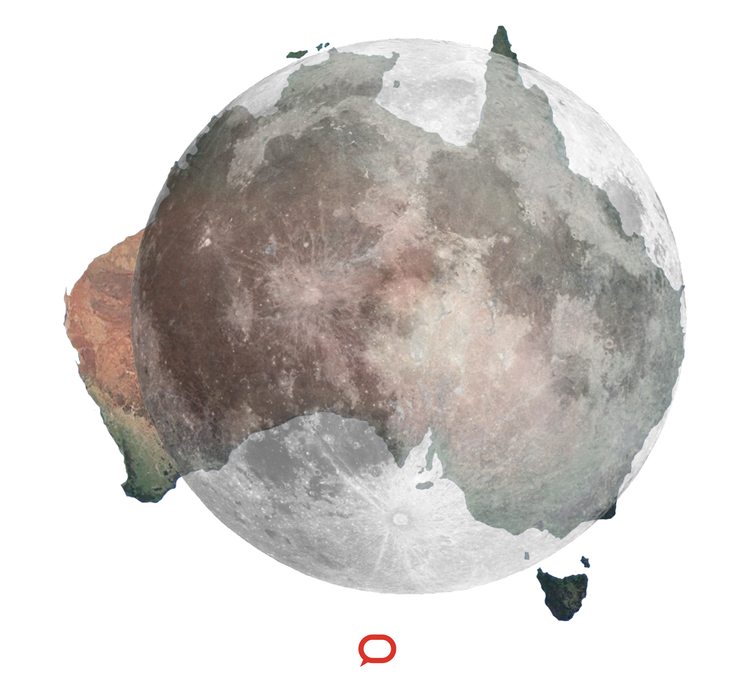

Несмотря на то, что мы можем наблюдать Луну в ночном небе (а иногда и при свете дня), представить ее размер и удаленность от Земли в перспективе довольно сложно.

Насколько велика Луна? Ответ на этот вопрос не так прост, как может показаться на первый взгляд. Так же как и Земля, Луна не является идеально круглой и имеет слегка сплющенную форму (приплюснутый шар). Это означает, что диаметр Луны от полюса к полюсу меньше ее диаметра на экваторе.

Тем не менее, разница между этими диаметрами не велика и составляет всего лишь четыре километра. Экваториальный диаметр Луны составляет примерно 3476км, а полярный – 3472 км. Для простоты понимания это расстояние можно сравнить с похожей по размеру территорией, например, с Австралией.

От побережья к побережью

Расстояние между двумя крайними австралийскими городами, Перт и Брисбен, по прямой составляет 3606 км. Такова протяженность Австралии. Таким образом, если поместить Австралию и Луну рядом, растянув последнюю по диаметру, их протяженность будет примерно одинакова.

С другой стороны, такой взгляд является слишком односторонним. Хотя Луна имеет одинаковую протяженность с Австралией, на самом деле она гораздо больше. Площадь Австралии составляет примерно 7,69 миллионов квадратных километров, тогда как площадь Луны равна 37,94 миллионов квадратных километров, что почти в пять раз превышает территорию Австралии.

Как далеко находится Луна?

Ответ на вопрос о расстоянии до Луны также может показаться сложнее, чем мы думаем. Луна вращается вокруг Земли по эллиптической орбите, то есть ее удаленность от нашей планеты постоянно меняется, причем разница может достигать 50000 км, именно поэтому размер Луны в нашем небе постоянно меняется. Кроме того, орбита Луны подвергается влиянию других объектов Солнечной системы. Кроме того, Луна постепенно отдаляется от Земли в результате приливного влияния.

Более тщательно исследовать последнюю информацию позволили миссии «Аполло». Побывавшие на Луне в 1969 году американские астронавты установили на ее поверхности несколько зеркальных отражателей, которые не требуют энергии и работают до сих пор. Система отражателей расположена так, что отправленный с Земли лазерный луч, отразившись, возвращается назад отправителю.

Вычислив время, которое требуется лазеру, чтобы достичь Луны и попасть обратно, ученые получили возможность очень точно измерять расстояние до Луны и отслеживать удаление Луны от Земли. В результате было установлено, что Луна отдаляется от Земли со скоростью 38 мм в год или около 4 метров в столетие.

Как добраться до Луны

Среднее расстояние между Луной и Землей составляет 384402 км. Попробуем представить эту цифру в сравнении с земными расстояниями.

Если мы захотим добраться все от того же Брисбена до Перта на автомобиле, нам придется преодолеть расстояние в 4310 км, на что потребуется около 46 часов. Для преодоления расстояния, равное расстоянию между Землей и Луной, подобное путешествие придется совершить более 89 раз. На это потребуется пять с половиной месяцев непрерывной езды на автомобиле, без учета пробок и возможных ДТП.

К счастью, астронавты «Аполло-11» не были ограничены австралийскими скоростными нормами, и в 1969 году командный модуль «Колумбия» достиг лунной орбиты всего за три дня и четыре часа.

Солнечное затмение

Экваториальный диаметр Солнца составляет почти 1,4 миллиона километров, что приблизительно в 400 раз превышает диаметр Луны. Любопытно, что расстояние между Землей и Солнцем (равное 149,6 миллионам километров) составляет примерно 400 расстояний между Землей и Луной.

Именно поэтому Луна и Солнце кажутся нам с Земли одинаковыми по размеру. В результате, когда Луна и Солнце находятся на одной линии (как кажется с Земли), мы можем наблюдать удивительное явление – полное затмение Солнца.

К сожалению, ученые пришли к выводу, что в будущем солнечные затмения на Земле прекратятся. Благодаря своему удалению, Луна однажды окажется слишком далеко, чтобы затмевать Солнце. Большинство ученых сходятся во мнении, что это произойдет примерно через 600 миллионов лет.

Луноходы

Несмотря на прогресс в развитии космоса, Луна до сих пор остается единственным небесным телом, по которому ходил человек, причем случилось это полвека лет назад. Спустя пятьдесят лет после первого (и совершенного единственной страной) прилунения из двенадцати побывавших на спутнике Земли человек в живых осталось только четверо.

Хочется надеяться, что в ближайшие годы люди смогут вернуться на Луну и вдохновят новое поколение продолжать изучение нашего ближайшего небесного соседа.

Источник

Эволюция системы Луна и Земля

Эволюция системы Луна и Земля