Поможем понять и полюбить химию

Начать учиться

Валентность

Из этой статьи вы узнаете, что называется валентностью в химии, научитесь находить ее значение и использовать для составления химических формул.

Понятие валентности

Валентность — это способность атома химического элемента образовывать определенное число химических связей с другими атомами.

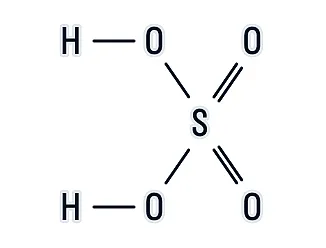

Рассмотрим структурную формулу H2SO4, с помощью которой можно определить, как атомы связаны между собой в веществе:

Исходя из структуры, можно сделать выводы:

-

атомы водорода H имеют одну химическую связь, то есть одновалентны;

-

сера S имеет шесть химических связей, то есть шестивалентна;

-

каждый атом кислорода O имеет две химические связи — двухвалентен.

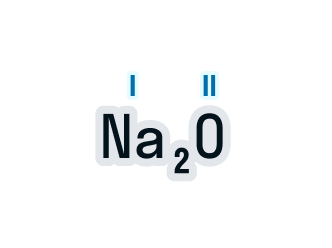

Валентность обозначается римской цифрой над знаком химического элемента в формуле. Например:

Атом натрия имеет валентность, равную 1, а атом кислорода — равную 2.

Получай лайфхаки, статьи, видео и чек-листы по обучению на почту

Полезные подарки для родителей

В колесе фортуны — гарантированные призы, которые помогут наладить учебный процесс и выстроить отношения с ребёнком!

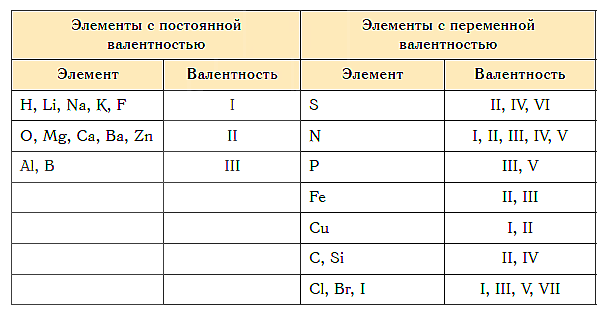

Постоянная и переменная валентность

Среди всех элементов выделяют две группы: с постоянной и переменной валентностью.

У элементов с постоянной валентностью в любом соединении она одинакова. Эти элементы и проявляемую ими валентность придется выучить.

|

Элемент |

Валентность |

|---|---|

|

H, F, Li, Na, K, Ag |

I |

|

O, Be, Mg, Ca, Ba, Zn |

II |

|

Al |

III |

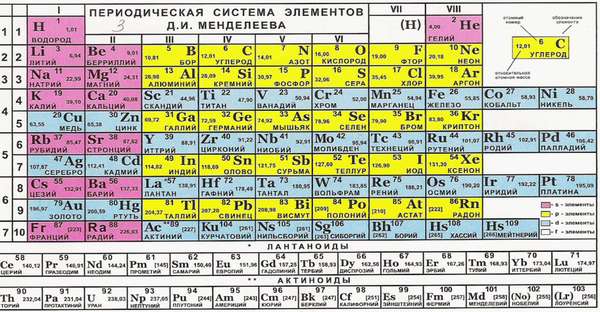

Переменная валентность меняется в зависимости от соединения. Элементов с переменной валентностью большинство. Как правило, они характеризуются высшей, промежуточной и низшей валентностью:

-

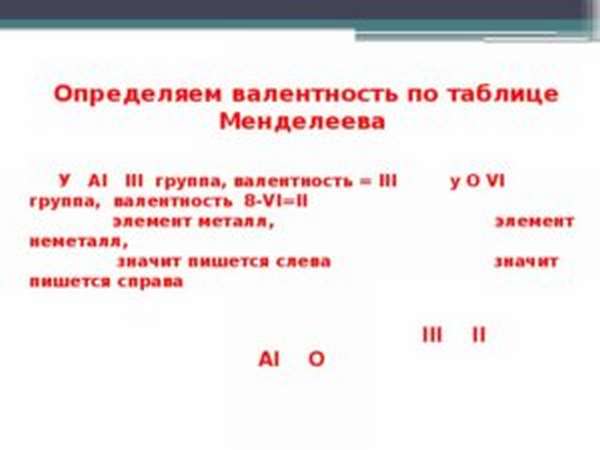

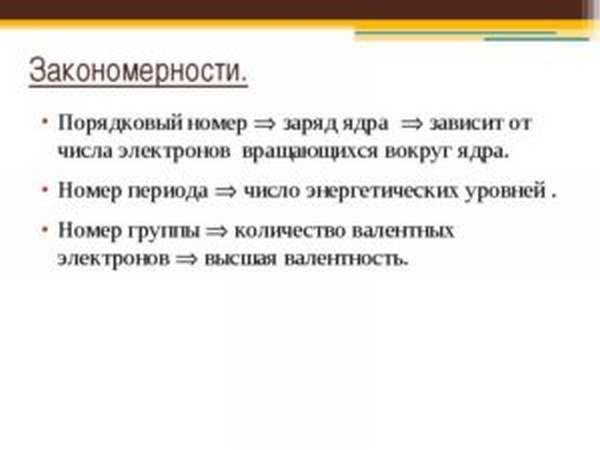

высшая валентность для элементов главных подгрупп совпадает с номером группы (№гр);

-

низшая валентность вычисляется по формуле: 8 − №гр;

-

промежуточная валентность — число между низшей и высшей валентностью. Обычно промежуточные валентности соответствуют четности группы.

Пример: как определить валентность по таблице Менделеева

Сера S располагается в группе VIА таблицы Менделеева. Значит:

-

высшая валентность серы равна VI;

-

вычислим низшую валентность: 8 − 6 = 2. Низшая валентность равна II;

-

сера расположена в группе VI — это четное число. Значит, промежуточными валентностями будут все четные числа между низшей и высшей валентностью. В случае с серой между числами 2 и 6 расположено только одно четное число — 4. Промежуточная валентность серы — IV.

В таблице собрали все возможные валентности для некоторых химических элементов.

|

Элемент |

Валентность |

|---|---|

|

C, Si |

II, IV |

|

N |

I, II, III, IV |

|

P |

III, V |

|

S |

II, IV, VI |

|

Cl, Br, I |

I, III, V, VII |

|

Fe |

II, III |

|

Cu |

I, II |

Обратите внимание

Понятия «степень окисления» и «валентность» — это не одно и то же, хотя в большинстве случаев они численно совпадают. Степень окисления — это условный заряд атома, он бывает положительным или отрицательным. А валентность — способность атома образовывать связи, она не может принимать отрицательные значения.

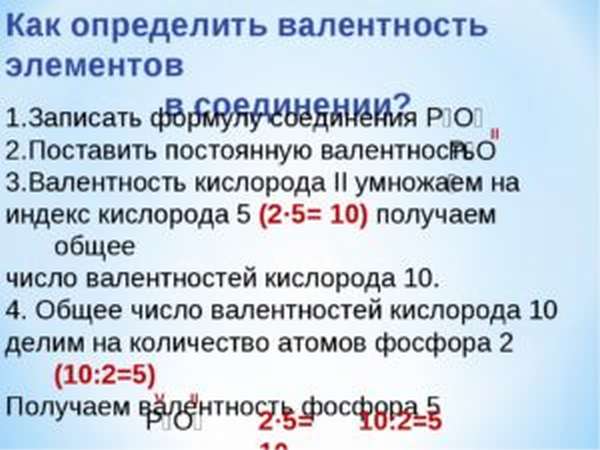

Как определить валентность химического элемента с переменной валентностью в соединении

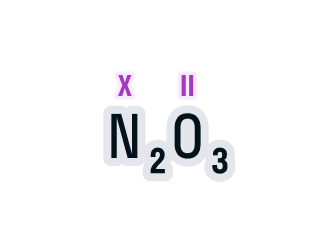

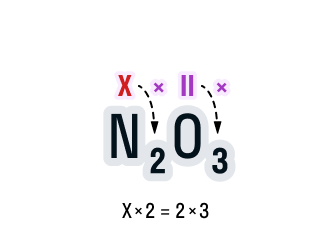

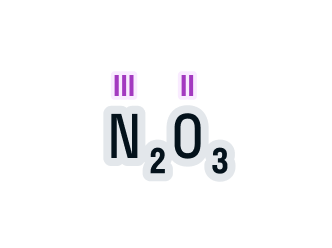

Определим валентность азота в соединении N2O3.

-

Над элементами с постоянной валентностью подпишем ее значение, в нашем случае это кислород:

-

Общее число валентностей каждого элемента в соединении должно совпадать. Находится общее число валентностей с помощью умножения валентности на число атомов данного химического элемента в соединении.

Считаем: общее число валентностей кислорода равно 2 · 3. Значит, общее число валентностей азота в данном соединении будет равно x · 2. Получаем уравнение: х · 2 = 2 · 3.

-

Вычислим х в получившемся уравнении:

2х = 6;

х = 3.

-

Валентность азота в данном химическом соединении равна трем.

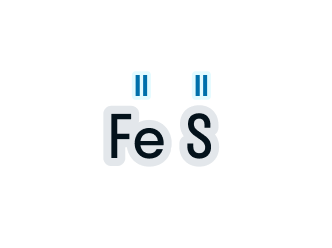

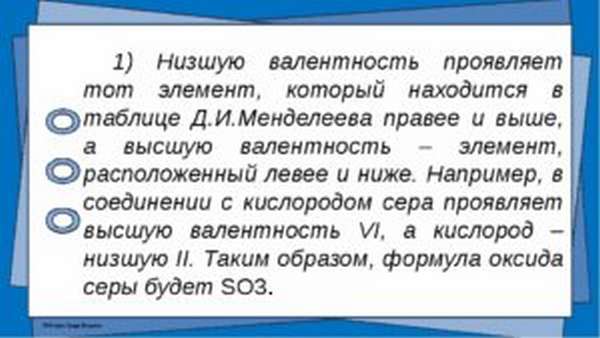

Встречаются бинарные соединения (то есть соединения, состоящие только из двух видов атомов), в которых неизвестны валентности обоих атомов элементов. Как найти валентности химических элементов в этом случае?

Для определения значения валентности необходимо запомнить, что неметаллы в бинарных соединениях, расположенные на втором месте, проявляют свою низшую валентность.

Например, в сульфидах (FeS) сера расположена на втором месте и проявляет низшую валентность, равную двум.

Тогда валентность железа в данном сульфиде можно рассчитать по приведенному выше алгоритму — ее значение равно двум.

В хлоридах (например, AgCl) хлор проявляет низшую валентность, равную единице.

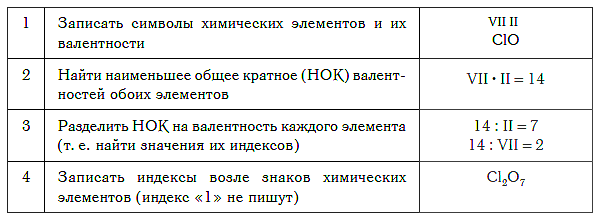

Как составить формулу химического соединения по значениям валентностей элементов

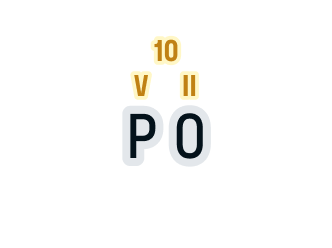

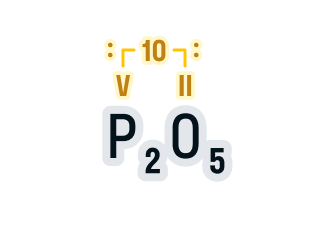

Составим формулу оксида фосфора (V).

-

Записываем обозначения элементов и над ними указываем валентности.

Валентность фосфора в данном соединении указана в названии вещества (V), а валентность кислорода всегда равна II. -

Находим НОК валентностей, в нашем случае 5 · 2 = 10. Для удобства запишем его над формулой:

-

Делим НОК на валентность каждого элемента, а результат записываем в индекс:

10 : 5 = 2 — индекс фосфора;

10 : 2 = 5 — индекс кислорода.

Получаем соединение P2O5.

Вопросы для самопроверки

-

Что такое валентность в химии? Можно ли сказать, что валентность и степень окисления — это одно и то же?

-

Как узнать высшую и низшую валентность какого-либо химического элемента?

-

Назовите три химических элемента с валентностью, равной единице.

-

Среди перечисленных химических элементов выберите те, у которых валентность переменная: K, S, Al, Cu, Ca, P, Si, Mn, Mg, O.

-

Определите значения валентностей каждого химического элемента в следующих соединениях: FeCl3, Cl2O7, CuS, AlP.

-

Составьте химические формулы веществ:

-

Хлорид железа (II).

-

Оксид углерода (IV).

-

Оксид магния.

-

-

Верно ли, что значение высшей валентности химических элементов увеличивается по периоду слева направо в таблице Менделеева?

Тему «Валентность» проходят на уроках химии в 8-м классе, и без ее понимания сложно двигаться дальше, а уж тем более сдавать государственные экзамены. Онлайн-курс подготовки к ЕГЭ по химии от Skysmart поможет освежить знания за все годы школьной программы, заполнить пробелы и снять стресс перед экзаменом. Вводный урок бесплатный!

В уроке 6 «Валентность» из курса «Химия для чайников» дадим определение валентности, научимся ее определять; рассмотрим элементы с постоянной и переменной валентностью, кроме того научимся составлять химические формулы по валентности. Напоминаю, что в прошлом уроке «Химическая формула» мы дали определение химическим формулам и их индексам, а также выяснили различия химических формул веществ молекулярного и немолекулярного строения.

Вы уже знаете, что в химических соединениях атомы разных элементов находятся в определенных числовых соотношениях. От чего зависят эти соотношения?

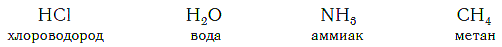

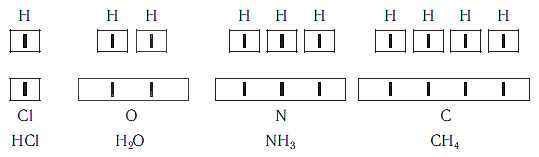

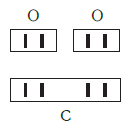

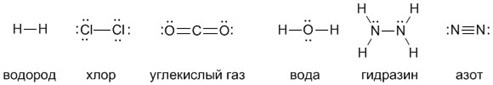

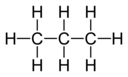

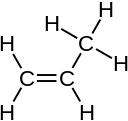

Рассмотрим химические формулы нескольких соединений водорода с атомами других элементов:

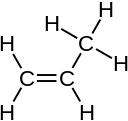

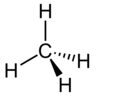

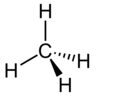

Нетрудно заметить, что атом хлора связан с одним атомом водорода, атом кислорода — с двумя, атом азота — с тремя, а атом углерода — с четырьмя атомами водорода. В то же время в молекуле углекислого газа СО2 атом углерода связан с двумя атомами кислорода. Из этих примеров видно, что атомы обладают разной способностью соединяться с другими атомами. Такая способность атомов выражается с помощью численной характеристики, называемой валентностью.

Валентность — численная характеристика способности атомов данного элемента соединяться с другими атомами.

Поскольку один атом водорода может соединиться только с одним атомом другого элемента, валентность атома водорода принята равной единице. Иначе говорят, что атом водорода обладает одной единицей валентности, т. е. он одновалентен.

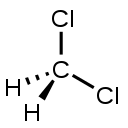

Валентность атома какого-либо другого элемента равна числу соединившихся с ним атомов водорода. Поэтому в молекуле HCl у атома хлора валентность равна единице, а в молекуле H2O у атома кислорода валентность равна двум. По той же причине в молекуле NH3 валентность атома азота равна трем, а в молекуле CH4 валентность атома углерода равна четырем. Если условно обозначить единицу валентности черточкой |, вышесказанное можно изобразить схематически:

Следовательно, валентность атома любого элемента есть число, которое показывает, со сколькими атомами одновалентного элемента связан данный атом в химическом соединении.

Численные значения валентности обозначают римскими цифрами над символами химических элементов:

Содержание

- Определение валентности

- Постоянная и переменная валентность

- Составление химических формул по валентности

Определение валентности

Однако водород образует соединения далеко не со всеми элементами, а вот кислородные соединения есть почти у всех элементов. И во всех таких соединениях атомы кислорода проявляют валентность, равную двум. Зная это, можно определять валентности атомов других элементов в их бинарных соединениях с кислородом. (Бинарными называются соединения, состоящие из атомов двух химических элементов.)

Чтобы это сделать, необходимо соблюдать простое правило: в химической формуле вещества суммарные числа единиц валентности атомов каждого элемента должны быть одинаковыми.

Так, в молекуле воды H2O общее число единиц валентности двух атомов водорода равно произведению валентности одного атома на соответствующий числовой индекс в формуле:

Так же определяют число единиц валентности атома кислорода:

По величине валентности атомов одного элемента можно определить валентность атомов другого элемента. Например, определим валентность атома углерода в молекуле углекислого газа СО2:

Согласно вышеприведенному правилу х·1 = II·2, откуда х = IV.

Существует и другое соединение углерода с кислородом — угарный газ СО, в молекуле которого атом углерода соединен только с одним атомом кислорода:

В этом веществе валентность углерода равна II, так как х·1 = II·1, откуда х = II:

Постоянная и переменная валентность

Как видим, углерод соединяется с разным числом атомов кислорода, т. е. имеет переменную валентность. У большинства элементов валентность — величина переменная. Только у водорода, кислорода и еще нескольких элементов она постоянна (см. таблицу).

Составление химических формул по валентности

Зная валентность элементов, можно составлять формулы их бинарных соединений. Например, необходимо записать формулу кислородного соединения хлора, в котором валентность хлора равна семи. Порядок действий здесь таков.

Еще один пример. Составим формулу соединения кремния с азотом, если валентность кремния равна IV, а азота — III.

Записываем рядом символы элементов в следующем виде:

Затем находим НОК валентностей обоих элементов. Оно равно 12 (IV·III).

Определяем индексы каждого элемента:

Записываем формулу соединения: Si3N4.

В дальнейшем при составлении формул веществ не обязательно указывать цифрами значения валентностей, а необходимые несложные вычисления можно выполнять в уме.

Краткие выводы урока:

- Численной характеристикой способности атомов данного элемента соединяться с другими атомами является валентность.

- Валентность водорода постоянна и равна единице. Валентность кислорода также постоянна и равна двум.

- Валентность большинства остальных элементов не является постоянной. Ее можно определить по формулам их бинарных соединений с водородом или кислородом.

Надеюсь урок 6 «Валентность» был понятным и познавательным. Если у вас возникли вопросы, пишите их в комментарии.

In chemistry, the valence (US spelling) or valency (British spelling) of an element is the measure of its combining capacity with other atoms when it forms chemical compounds or molecules.

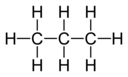

Description

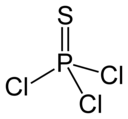

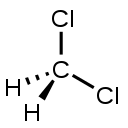

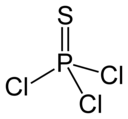

The combining capacity, or affinity of an atom of a given element is determined by the number of hydrogen atoms that it combines with. In methane, carbon has a valence of 4; in ammonia, nitrogen has a valence of 3; in water, oxygen has a valence of 2; and in hydrogen chloride, chlorine has a valence of 1. Chlorine, as it has a valence of one, can be substituted for hydrogen. Phosphorus has a valence of 5 in phosphorus pentachloride, PCl5. Valence diagrams of a compound represent the connectivity of the elements, with lines drawn between two elements, sometimes called bonds, representing a saturated valency for each element.[1] The two tables below show some examples of different compounds, their valence diagrams, and the valences for each element of the compound.

| Compound | H2 Hydrogen |

CH4 Methane |

C3H8 Propane |

C3H6 Propylene |

C2H2 Acetylene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagram |

|

|

|

||

| Valencies |

|

|

|

|

|

| Compound | NH3 Ammonia |

NaCN Sodium cyanide |

PSCl3 Thiophosphoryl chloride |

H2S Hydrogen sulfide |

H2SO4 Sulfuric acid |

H2S2O6 Dithionic acid |

Cl2O7 Dichlorine heptoxide |

XeO4 Xenon tetroxide |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagram |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Valencies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Modern definitions

Valence is defined by the IUPAC as:[2]

- The maximum number of univalent atoms (originally hydrogen or chlorine atoms) that may combine with an atom of the element under consideration, or with a fragment, or for which an atom of this element can be substituted.

An alternative modern description is:[3]

- The number of hydrogen atoms that can combine with an element in a binary hydride or twice the number of oxygen atoms combining with an element in its oxide or oxides.

This definition differs from the IUPAC definition as an element can be said to have more than one valence.

A very similar modern definition given in a recent article defines the valence of a particular atom in a molecule as «the number of electrons that an atom uses in bonding», with two equivalent formulas for calculating valence:[4]

- valence = number of electrons in valence shell of free atom – number of non-bonding electrons on atom in molecule,

and

- valence = number of bonds + formal charge.

Historical development

The etymology of the words valence (plural valences) and valency (plural valencies) traces back to 1425, meaning «extract, preparation», from Latin valentia «strength, capacity», from the earlier valor «worth, value», and the chemical meaning referring to the «combining power of an element» is recorded from 1884, from German Valenz.[5]

The concept of valence was developed in the second half of the 19th century and helped successfully explain the molecular structure of inorganic and organic compounds.[1]

The quest for the underlying causes of valence led to the modern theories of chemical bonding, including the cubical atom (1902), Lewis structures (1916), valence bond theory (1927), molecular orbitals (1928), valence shell electron pair repulsion theory (1958), and all of the advanced methods of quantum chemistry.

In 1789, William Higgins published views on what he called combinations of «ultimate» particles, which foreshadowed the concept of valency bonds.[6] If, for example, according to Higgins, the force between the ultimate particle of oxygen and the ultimate particle of nitrogen were 6, then the strength of the force would be divided accordingly, and likewise for the other combinations of ultimate particles (see illustration).

The exact inception, however, of the theory of chemical valencies can be traced to an 1852 paper by Edward Frankland, in which he combined the older radical theory with thoughts on chemical affinity to show that certain elements have the tendency to combine with other elements to form compounds containing 3, i.e., in the 3-atom groups (e.g., NO3, NH3, NI3, etc.) or 5, i.e., in the 5-atom groups (e.g., NO5, NH4O, PO5, etc.), equivalents of the attached elements. According to him, this is the manner in which their affinities are best satisfied, and by following these examples and postulates, he declares how obvious it is that[7]

A tendency or law prevails (here), and that, no matter what the characters of the uniting atoms may be, the combining power of the attracting element, if I may be allowed the term, is always satisfied by the same number of these atoms.

This “combining power” was afterwards called quantivalence or valency (and valence by American chemists).[6] In 1857 August Kekulé proposed fixed valences for many elements, such as 4 for carbon, and used them to propose structural formulas for many organic molecules, which are still accepted today.

Most 19th-century chemists defined the valence of an element as the number of its bonds without distinguishing different types of valence or of bond. However, in 1893 Alfred Werner described transition metal coordination complexes such as [Co(NH3)6]Cl3, in which he distinguished principal and subsidiary valences (German: ‘Hauptvalenz’ and ‘Nebenvalenz’), corresponding to the modern concepts of oxidation state and coordination number respectively.

For main-group elements, in 1904 Richard Abegg considered positive and negative valences (maximal and minimal oxidation states), and proposed Abegg’s rule to the effect that their difference is often 8.

Electrons and valence

The Rutherford model of the nuclear atom (1911) showed that the exterior of an atom is occupied by electrons, which suggests that electrons are responsible for the interaction of atoms and the formation of chemical bonds. In 1916, Gilbert N. Lewis explained valence and chemical bonding in terms of a tendency of (main-group) atoms to achieve a stable octet of 8 valence-shell electrons. According to Lewis, covalent bonding leads to octets by the sharing of electrons, and ionic bonding leads to octets by the transfer of electrons from one atom to the other. The term covalence is attributed to Irving Langmuir, who stated in 1919 that «the number of pairs of electrons which any given atom shares with the adjacent atoms is called the covalence of that atom».[8] The prefix co- means «together», so that a co-valent bond means that the atoms share a valence. Subsequent to that, it is now more common to speak of covalent bonds rather than valence, which has fallen out of use in higher-level work from the advances in the theory of chemical bonding, but it is still widely used in elementary studies, where it provides a heuristic introduction to the subject.

In the 1930s, Linus Pauling proposed that there are also polar covalent bonds, which are intermediate between covalent and ionic, and that the degree of ionic character depends on the difference of electronegativity of the two bonded atoms.

Pauling also considered hypervalent molecules, in which main-group elements have apparent valences greater than the maximal of 4 allowed by the octet rule. For example, in the sulfur hexafluoride molecule (SF6), Pauling considered that the sulfur forms 6 true two-electron bonds using sp3d2 hybrid atomic orbitals, which combine one s, three p and two d orbitals. However more recently, quantum-mechanical calculations on this and similar molecules have shown that the role of d orbitals in the bonding is minimal, and that the SF6 molecule should be described as having 6 polar covalent (partly ionic) bonds made from only four orbitals on sulfur (one s and three p) in accordance with the octet rule, together with six orbitals on the fluorines.[9] Similar calculations on transition-metal molecules show that the role of p orbitals is minor, so that one s and five d orbitals on the metal are sufficient to describe the bonding.[10]

Common valences

For elements in the main groups of the periodic table, the valence can vary between 1 and 7.

| Group | Valence 1 | Valence 2 | Valence 3 | Valence 4 | Valence 5 | Valence 6 | Valence 7 | Valence 8 | Typical valences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (I) | NaCl | 1 | |||||||

| 2 (II) | MgCl2 | 2 | |||||||

| 13 (III) | BCl3 AlCl3 Al2O3 |

3 | |||||||

| 14 (IV) | CO | CH4 | 4 | ||||||

| 15 (V) | NO | NH3 PH3 As2O3 |

NO2 | N2O5 PCl5 |

3 and 5 | ||||

| 16 (VI) | H2O H2S |

SO2 | SO3 | 2 and 6 | |||||

| 17 (VII) | HCl | HClO2 | ClO2 | HClO3 | Cl2O7 | 1 and 7 | |||

| 18 (VIII) | XeO4 | 8 |

Many elements have a common valence related to their position in the periodic table, and nowadays this is rationalised by the octet rule.

The Greek/Latin numeral prefixes (mono-/uni-, di-/bi-, tri-/ter-, and so on) are used to describe ions in the charge states 1, 2, 3, and so on, respectively. Polyvalence or multivalence refers to species that are not restricted to a specific number of valence bonds. Species with a single charge are univalent (monovalent). For example, the Cs+ cation is a univalent or monovalent cation, whereas the Ca2+ cation is a divalent cation, and the Fe3+ cation is a trivalent cation. Unlike Cs and Ca, Fe can also exist in other charge states, notably 2+ and 4+, and is thus known as a multivalent (polyvalent) ion.[11] Transition metals and metals to the right are typically multivalent but there is no simple pattern predicting their valency.[12]

| Valence | More common adjective‡ | Less common synonymous adjective‡§ |

|---|---|---|

| 0-valent | zerovalent | nonvalent |

| 1-valent | monovalent | univalent |

| 2-valent | divalent | bivalent |

| 3-valent | trivalent | tervalent |

| 4-valent | tetravalent | quadrivalent |

| 5-valent | pentavalent | quinquevalent, quinquivalent |

| 6-valent | hexavalent | sexivalent |

| 7-valent | heptavalent | septivalent |

| 8-valent | octavalent | — |

| 9-valent | nonavalent | — |

| 10-valent | decavalent | — |

| 12-valent | dodecavalent | — |

| multiple / many / variable | polyvalent | multivalent |

| together | covalent | — |

| not together | noncovalent | — |

† The same adjectives are also used in medicine to refer to vaccine valence, with the slight difference that in the latter sense, quadri- is more common than tetra-.

‡ As demonstrated by hit counts in Google web search and Google Books search corpora (accessed 2017).

§ A few other forms can be found in large English-language corpora (for example, *quintavalent, *quintivalent, *decivalent), but they are not the conventionally established forms in English and thus are not entered in major dictionaries.

Valence versus oxidation state

Because of the ambiguity of the term valence,[13] other notations are currently preferred. Beside the system of oxidation states (also called oxidation numbers) as used in Stock nomenclature for coordination compounds,[14] and the lambda notation, as used in the IUPAC nomenclature of inorganic chemistry,[15] oxidation state is a more clear indication of the electronic state of atoms in a molecule.

The oxidation state of an atom in a molecule gives the number of valence electrons it has gained or lost.[16] In contrast to the valency number, the oxidation state can be positive (for an electropositive atom) or negative (for an electronegative atom).

Elements in a high oxidation state have an oxidation state higher than +4, and also, elements in a high valence state (hypervalent elements) have a valence higher than 4. For example, in perchlorates ClO−4, chlorine has 7 valence bonds (thus, it is heptavalent, in other words, it has valence 7), and it has oxidation state +7; in ruthenium tetroxide RuO4, ruthenium has 8 valence bonds (thus, it is octavalent, in other words, it has valence 8), and it has oxidation state +8.

In some scenarios, the difference between valence and oxidation state arises. Valence and oxidation state of the same atom may not be the same. For example, in disulfur decafluoride molecule S2F10, each sulfur atom has 6 valence bonds (5 single bonds with fluorine atoms and 1 single bond with sulfur atom), thus, each sulfur atom is hexavalent, in other words, it has valence 6, but has oxidation state +5. In dioxygen molecule O2, each oxygen atom has 2 valence bonds, thus, each oxygen atom is divalent, in other words, it has valence 2, but has oxidation state 0. In acetylene H−C≡C−H, each carbon atom has 4 valence bonds (1 single bond with hydrogen atom and 3 single bonds with carbon atom), thus, each carbon atom is tetravalent, in other words, it has valence 4, but has oxidation state −1.

Examples

| Compound | Formula | Valence | Oxidation state | Diagram |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen chloride | HCl | H = 1 Cl = 1 | H = +1 Cl = −1 | H−Cl |

| Perchloric acid * | HClO4 | H = 1 Cl = 7 O = 2 | H = +1 Cl = +7 O = −2 |

|

| Methane | CH4 | C = 4 H = 1 | C = −4 H = +1 |

|

| Dichloromethane ** | CH2Cl2 | C = 4 H = 1 Cl = 1 | C = 0 H = +1 Cl = −1 |

|

| Ferrous oxide *** | FeO | Fe = 2 O = 2 | Fe = +2 O = −2 | Fe=O |

| Ferric oxide *** | Fe2O3 | Fe = 3 O = 2 | Fe = +3 O = −2 | O=Fe−O−Fe=O |

| Sodium hydride | NaH | Na = 1 H = 1 | Na = +1 H = −1 | Na−H |

* The perchlorate ion ClO−4 is monovalent, in other words, it has valence 1.

** Valences may also be different from absolute values of oxidation states due to different polarity of bonds. For example, in dichloromethane, CH2Cl2, carbon has valence 4 but oxidation state 0.

*** Iron oxides appear in a crystal structure, so no typical molecule can be identified. In ferrous oxide, Fe has oxidation state +2; in ferric oxide, oxidation state +3.

| Compound | Formula | Valence | Oxidation state | Diagram |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen | H2 | H = 1 | H = 0 | H−H |

| Chlorine | Cl2 | Cl = 1 | Cl = 0 | Cl−Cl |

| Hydrogen peroxide | H2O2 | H = 1 O = 2 | H = +1 O = −1 |

|

| Hydrazine | N2H4 | H = 1 N = 3 | H = +1 N = −2 |

|

| Disulfur decafluoride | S2F10 | S = 6 F = 1 | S = +5 F = −1 |

|

| Dithionic acid | H2S2O6 | S = 6 O = 2 H = 1 | S = +5 O = −2 H = +1 |

|

| Hexachloroethane | C2Cl6 | C = 4 Cl = 1 | C = +3 Cl = −1 |

|

| Ethylene | C2H4 | C = 4 H = 1 | C = −2 H = +1 |

|

| Acetylene | C2H2 | C = 4 H = 1 | C = −1 H = +1 | H−C≡C−H |

| Mercury(I) chloride | Hg2Cl2 | Hg = 2 Cl = 1 | Hg = +1 Cl = −1 | Cl−Hg−Hg−Cl |

«Maximum number of bonds» definition

Frankland took the view that the valence (he used the term «atomicity») of an element was a single value that corresponded to the maximum value observed. The number of unused valencies on atoms of what are now called the p-block elements is generally even, and Frankland suggested that the unused valencies saturated one another. For example, nitrogen has a maximum valence of 5, in forming ammonia two valencies are left unattached; sulfur has a maximum valence of 6, in forming hydrogen sulphide four valencies are left unattached.[17][18]

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) has made several attempts to arrive at an unambiguous definition of valence. The current version, adopted in 1994:[19]

- The maximum number of univalent atoms (originally hydrogen or chlorine atoms) that may combine with an atom of the element under consideration, or with a fragment, or for which an atom of this element can be substituted.[2]

Hydrogen and chlorine were originally used as examples of univalent atoms, because of their nature to form only one single bond. Hydrogen has only one valence electron and can form only one bond with an atom that has an incomplete outer shell. Chlorine has seven valence electrons and can form only one bond with an atom that donates a valence electron to complete chlorine’s outer shell. However, chlorine can also have oxidation states from +1 to +7 and can form more than one bond by donating valence electrons.

Hydrogen has only one valence electron, but it can form bonds with more than one atom. In the bifluoride ion ([HF2]−), for example, it forms a three-center four-electron bond with two fluoride atoms:

- [F−H F− ↔ F− H−F]

Another example is the three-center two-electron bond in diborane (B2H6).

Maximum valences of the elements

Maximum valences for the elements are based on the data from list of oxidation states of the elements. They are shown by the color code at the bottom of the table.

Maximum valences of the elements |

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | ||

| Group → | |||||||||||||||||||

| ↓ Period | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 H |

2 He |

|||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 3 Li |

4 Be |

5 B |

6 C |

7 N |

8 O |

9 F |

10 Ne |

|||||||||||

| 3 | 11 Na |

12 Mg |

13 Al |

14 Si |

15 P |

16 S |

17 Cl |

18 Ar |

|||||||||||

| 4 | 19 K |

20 Ca |

21 Sc |

22 Ti |

23 V |

24 Cr |

25 Mn |

26 Fe |

27 Co |

28 Ni |

29 Cu |

30 Zn |

31 Ga |

32 Ge |

33 As |

34 Se |

35 Br |

36 Kr |

|

| 5 | 37 Rb |

38 Sr |

39 Y |

40 Zr |

41 Nb |

42 Mo |

43 Tc |

44 Ru |

45 Rh |

46 Pd |

47 Ag |

48 Cd |

49 In |

50 Sn |

51 Sb |

52 Te |

53 I |

54 Xe |

|

| 6 | 55 Cs |

56 Ba |

71 Lu |

72 Hf |

73 Ta |

74 W |

75 Re |

76 Os |

77 Ir |

78 Pt |

79 Au |

80 Hg |

81 Tl |

82 Pb |

83 Bi |

84 Po |

85 At |

86 Rn |

|

| 7 | 87 Fr |

88 Ra |

103 Lr |

104 Rf |

105 Db |

106 Sg |

107 Bh |

108 Hs |

109 Mt |

110 Ds |

111 Rg |

112 Cn |

113 Nh |

114 Fl |

115 Mc |

116 Lv |

117 Ts |

118 Og |

|

| 57 La |

58 Ce |

59 Pr |

60 Nd |

61 Pm |

62 Sm |

63 Eu |

64 Gd |

65 Tb |

66 Dy |

67 Ho |

68 Er |

69 Tm |

70 Yb |

||||||

| 89 Ac |

90 Th |

91 Pa |

92 U |

93 Np |

94 Pu |

95 Am |

96 Cm |

97 Bk |

98 Cf |

99 Es |

100 Fm |

101 Md |

102 No |

||||||

| Maximum valences are based on the List of oxidation states of the elements | |||||||||||||||||||

|

Primordial From decay Synthetic Border shows natural occurrence of the element |

See also

- Abegg’s rule

- Oxidation state

References

- ^ a b Partington, James Riddick (1921). A text-book of inorganic chemistry for university students (1st ed.). OL 7221486M.

- ^ a b IUPAC Gold Book definition: valence

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Parkin, Gerard (May 2006). «Valence, Oxidation Number, and Formal Charge: Three Related but Fundamentally Different Concepts». Journal of Chemical Education. 83 (5): 791. doi:10.1021/ed083p791. ISSN 0021-9584.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «valence». Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ a b Partington, J.R. (1989). A Short History of Chemistry. Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-486-65977-1.

- ^ Frankland, E. (1852). «On a New Series of Organic Bodies Containing Metals». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 142: 417–444. doi:10.1098/rstl.1852.0020. S2CID 186210604.

- ^ Langmuir, Irving (1919). «The Arrangement of Electrons in Atoms and Molecules». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 41 (6): 868–934. doi:10.1021/ja02227a002.

- ^ Magnusson, Eric (1990). «Hypercoordinate molecules of second-row elements: d functions or d orbitals?». J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112 (22): 7940–7951. doi:10.1021/ja00178a014.

- ^ Frenking, Gernot; Shaik, Sason, eds. (May 2014). «Chapter 7: Chemical bonding in Transition Metal Compounds». The Chemical Bond: Chemical Bonding Across the Periodic Table. Wiley – VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-33315-8.

- ^ Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, archived from the original on 2020-05-25, retrieved 2017-05-11.

- ^ «Lesson 7: Ions and Their Names». Clackamas Community College. Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ The Free Dictionary: valence

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the «Gold Book») (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) «Oxidation number». doi:10.1351/goldbook.O04363

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the «Gold Book») (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) «Lambda». doi:10.1351/goldbook.L03418

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the «Gold Book») (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) «Oxidation state». doi:10.1351/goldbook.O04365

- ^ Frankland, E. (1870). Lecture notes for chemical students(Google eBook) (2d ed.). J. Van Voorst. p. 21.

- ^ Frankland, E.; Japp, F.R (1885). Inorganic chemistry (1st ed.). pp. 75–85. OL 6994182M.

- ^ Muller, P. (1994). «Glossary of terms used in physical organic chemistry (IUPAC Recommendations 1994)». Pure and Applied Chemistry. 66 (5): 1077–1184. doi:10.1351/pac199466051077. S2CID 195819485.

In chemistry, the valence (US spelling) or valency (British spelling) of an element is the measure of its combining capacity with other atoms when it forms chemical compounds or molecules.

Description

The combining capacity, or affinity of an atom of a given element is determined by the number of hydrogen atoms that it combines with. In methane, carbon has a valence of 4; in ammonia, nitrogen has a valence of 3; in water, oxygen has a valence of 2; and in hydrogen chloride, chlorine has a valence of 1. Chlorine, as it has a valence of one, can be substituted for hydrogen. Phosphorus has a valence of 5 in phosphorus pentachloride, PCl5. Valence diagrams of a compound represent the connectivity of the elements, with lines drawn between two elements, sometimes called bonds, representing a saturated valency for each element.[1] The two tables below show some examples of different compounds, their valence diagrams, and the valences for each element of the compound.

| Compound | H2 Hydrogen |

CH4 Methane |

C3H8 Propane |

C3H6 Propylene |

C2H2 Acetylene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagram |

|

|

|

||

| Valencies |

|

|

|

|

|

| Compound | NH3 Ammonia |

NaCN Sodium cyanide |

PSCl3 Thiophosphoryl chloride |

H2S Hydrogen sulfide |

H2SO4 Sulfuric acid |

H2S2O6 Dithionic acid |

Cl2O7 Dichlorine heptoxide |

XeO4 Xenon tetroxide |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagram |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Valencies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Modern definitions

Valence is defined by the IUPAC as:[2]

- The maximum number of univalent atoms (originally hydrogen or chlorine atoms) that may combine with an atom of the element under consideration, or with a fragment, or for which an atom of this element can be substituted.

An alternative modern description is:[3]

- The number of hydrogen atoms that can combine with an element in a binary hydride or twice the number of oxygen atoms combining with an element in its oxide or oxides.

This definition differs from the IUPAC definition as an element can be said to have more than one valence.

A very similar modern definition given in a recent article defines the valence of a particular atom in a molecule as «the number of electrons that an atom uses in bonding», with two equivalent formulas for calculating valence:[4]

- valence = number of electrons in valence shell of free atom – number of non-bonding electrons on atom in molecule,

and

- valence = number of bonds + formal charge.

Historical development

The etymology of the words valence (plural valences) and valency (plural valencies) traces back to 1425, meaning «extract, preparation», from Latin valentia «strength, capacity», from the earlier valor «worth, value», and the chemical meaning referring to the «combining power of an element» is recorded from 1884, from German Valenz.[5]

The concept of valence was developed in the second half of the 19th century and helped successfully explain the molecular structure of inorganic and organic compounds.[1]

The quest for the underlying causes of valence led to the modern theories of chemical bonding, including the cubical atom (1902), Lewis structures (1916), valence bond theory (1927), molecular orbitals (1928), valence shell electron pair repulsion theory (1958), and all of the advanced methods of quantum chemistry.

In 1789, William Higgins published views on what he called combinations of «ultimate» particles, which foreshadowed the concept of valency bonds.[6] If, for example, according to Higgins, the force between the ultimate particle of oxygen and the ultimate particle of nitrogen were 6, then the strength of the force would be divided accordingly, and likewise for the other combinations of ultimate particles (see illustration).

The exact inception, however, of the theory of chemical valencies can be traced to an 1852 paper by Edward Frankland, in which he combined the older radical theory with thoughts on chemical affinity to show that certain elements have the tendency to combine with other elements to form compounds containing 3, i.e., in the 3-atom groups (e.g., NO3, NH3, NI3, etc.) or 5, i.e., in the 5-atom groups (e.g., NO5, NH4O, PO5, etc.), equivalents of the attached elements. According to him, this is the manner in which their affinities are best satisfied, and by following these examples and postulates, he declares how obvious it is that[7]

A tendency or law prevails (here), and that, no matter what the characters of the uniting atoms may be, the combining power of the attracting element, if I may be allowed the term, is always satisfied by the same number of these atoms.

This “combining power” was afterwards called quantivalence or valency (and valence by American chemists).[6] In 1857 August Kekulé proposed fixed valences for many elements, such as 4 for carbon, and used them to propose structural formulas for many organic molecules, which are still accepted today.

Most 19th-century chemists defined the valence of an element as the number of its bonds without distinguishing different types of valence or of bond. However, in 1893 Alfred Werner described transition metal coordination complexes such as [Co(NH3)6]Cl3, in which he distinguished principal and subsidiary valences (German: ‘Hauptvalenz’ and ‘Nebenvalenz’), corresponding to the modern concepts of oxidation state and coordination number respectively.

For main-group elements, in 1904 Richard Abegg considered positive and negative valences (maximal and minimal oxidation states), and proposed Abegg’s rule to the effect that their difference is often 8.

Electrons and valence

The Rutherford model of the nuclear atom (1911) showed that the exterior of an atom is occupied by electrons, which suggests that electrons are responsible for the interaction of atoms and the formation of chemical bonds. In 1916, Gilbert N. Lewis explained valence and chemical bonding in terms of a tendency of (main-group) atoms to achieve a stable octet of 8 valence-shell electrons. According to Lewis, covalent bonding leads to octets by the sharing of electrons, and ionic bonding leads to octets by the transfer of electrons from one atom to the other. The term covalence is attributed to Irving Langmuir, who stated in 1919 that «the number of pairs of electrons which any given atom shares with the adjacent atoms is called the covalence of that atom».[8] The prefix co- means «together», so that a co-valent bond means that the atoms share a valence. Subsequent to that, it is now more common to speak of covalent bonds rather than valence, which has fallen out of use in higher-level work from the advances in the theory of chemical bonding, but it is still widely used in elementary studies, where it provides a heuristic introduction to the subject.

In the 1930s, Linus Pauling proposed that there are also polar covalent bonds, which are intermediate between covalent and ionic, and that the degree of ionic character depends on the difference of electronegativity of the two bonded atoms.

Pauling also considered hypervalent molecules, in which main-group elements have apparent valences greater than the maximal of 4 allowed by the octet rule. For example, in the sulfur hexafluoride molecule (SF6), Pauling considered that the sulfur forms 6 true two-electron bonds using sp3d2 hybrid atomic orbitals, which combine one s, three p and two d orbitals. However more recently, quantum-mechanical calculations on this and similar molecules have shown that the role of d orbitals in the bonding is minimal, and that the SF6 molecule should be described as having 6 polar covalent (partly ionic) bonds made from only four orbitals on sulfur (one s and three p) in accordance with the octet rule, together with six orbitals on the fluorines.[9] Similar calculations on transition-metal molecules show that the role of p orbitals is minor, so that one s and five d orbitals on the metal are sufficient to describe the bonding.[10]

Common valences

For elements in the main groups of the periodic table, the valence can vary between 1 and 7.

| Group | Valence 1 | Valence 2 | Valence 3 | Valence 4 | Valence 5 | Valence 6 | Valence 7 | Valence 8 | Typical valences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (I) | NaCl | 1 | |||||||

| 2 (II) | MgCl2 | 2 | |||||||

| 13 (III) | BCl3 AlCl3 Al2O3 |

3 | |||||||

| 14 (IV) | CO | CH4 | 4 | ||||||

| 15 (V) | NO | NH3 PH3 As2O3 |

NO2 | N2O5 PCl5 |

3 and 5 | ||||

| 16 (VI) | H2O H2S |

SO2 | SO3 | 2 and 6 | |||||

| 17 (VII) | HCl | HClO2 | ClO2 | HClO3 | Cl2O7 | 1 and 7 | |||

| 18 (VIII) | XeO4 | 8 |

Many elements have a common valence related to their position in the periodic table, and nowadays this is rationalised by the octet rule.

The Greek/Latin numeral prefixes (mono-/uni-, di-/bi-, tri-/ter-, and so on) are used to describe ions in the charge states 1, 2, 3, and so on, respectively. Polyvalence or multivalence refers to species that are not restricted to a specific number of valence bonds. Species with a single charge are univalent (monovalent). For example, the Cs+ cation is a univalent or monovalent cation, whereas the Ca2+ cation is a divalent cation, and the Fe3+ cation is a trivalent cation. Unlike Cs and Ca, Fe can also exist in other charge states, notably 2+ and 4+, and is thus known as a multivalent (polyvalent) ion.[11] Transition metals and metals to the right are typically multivalent but there is no simple pattern predicting their valency.[12]

| Valence | More common adjective‡ | Less common synonymous adjective‡§ |

|---|---|---|

| 0-valent | zerovalent | nonvalent |

| 1-valent | monovalent | univalent |

| 2-valent | divalent | bivalent |

| 3-valent | trivalent | tervalent |

| 4-valent | tetravalent | quadrivalent |

| 5-valent | pentavalent | quinquevalent, quinquivalent |

| 6-valent | hexavalent | sexivalent |

| 7-valent | heptavalent | septivalent |

| 8-valent | octavalent | — |

| 9-valent | nonavalent | — |

| 10-valent | decavalent | — |

| 12-valent | dodecavalent | — |

| multiple / many / variable | polyvalent | multivalent |

| together | covalent | — |

| not together | noncovalent | — |

† The same adjectives are also used in medicine to refer to vaccine valence, with the slight difference that in the latter sense, quadri- is more common than tetra-.

‡ As demonstrated by hit counts in Google web search and Google Books search corpora (accessed 2017).

§ A few other forms can be found in large English-language corpora (for example, *quintavalent, *quintivalent, *decivalent), but they are not the conventionally established forms in English and thus are not entered in major dictionaries.

Valence versus oxidation state

Because of the ambiguity of the term valence,[13] other notations are currently preferred. Beside the system of oxidation states (also called oxidation numbers) as used in Stock nomenclature for coordination compounds,[14] and the lambda notation, as used in the IUPAC nomenclature of inorganic chemistry,[15] oxidation state is a more clear indication of the electronic state of atoms in a molecule.

The oxidation state of an atom in a molecule gives the number of valence electrons it has gained or lost.[16] In contrast to the valency number, the oxidation state can be positive (for an electropositive atom) or negative (for an electronegative atom).

Elements in a high oxidation state have an oxidation state higher than +4, and also, elements in a high valence state (hypervalent elements) have a valence higher than 4. For example, in perchlorates ClO−4, chlorine has 7 valence bonds (thus, it is heptavalent, in other words, it has valence 7), and it has oxidation state +7; in ruthenium tetroxide RuO4, ruthenium has 8 valence bonds (thus, it is octavalent, in other words, it has valence 8), and it has oxidation state +8.

In some scenarios, the difference between valence and oxidation state arises. Valence and oxidation state of the same atom may not be the same. For example, in disulfur decafluoride molecule S2F10, each sulfur atom has 6 valence bonds (5 single bonds with fluorine atoms and 1 single bond with sulfur atom), thus, each sulfur atom is hexavalent, in other words, it has valence 6, but has oxidation state +5. In dioxygen molecule O2, each oxygen atom has 2 valence bonds, thus, each oxygen atom is divalent, in other words, it has valence 2, but has oxidation state 0. In acetylene H−C≡C−H, each carbon atom has 4 valence bonds (1 single bond with hydrogen atom and 3 single bonds with carbon atom), thus, each carbon atom is tetravalent, in other words, it has valence 4, but has oxidation state −1.

Examples

| Compound | Formula | Valence | Oxidation state | Diagram |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen chloride | HCl | H = 1 Cl = 1 | H = +1 Cl = −1 | H−Cl |

| Perchloric acid * | HClO4 | H = 1 Cl = 7 O = 2 | H = +1 Cl = +7 O = −2 |

|

| Methane | CH4 | C = 4 H = 1 | C = −4 H = +1 |

|

| Dichloromethane ** | CH2Cl2 | C = 4 H = 1 Cl = 1 | C = 0 H = +1 Cl = −1 |

|

| Ferrous oxide *** | FeO | Fe = 2 O = 2 | Fe = +2 O = −2 | Fe=O |

| Ferric oxide *** | Fe2O3 | Fe = 3 O = 2 | Fe = +3 O = −2 | O=Fe−O−Fe=O |

| Sodium hydride | NaH | Na = 1 H = 1 | Na = +1 H = −1 | Na−H |

* The perchlorate ion ClO−4 is monovalent, in other words, it has valence 1.

** Valences may also be different from absolute values of oxidation states due to different polarity of bonds. For example, in dichloromethane, CH2Cl2, carbon has valence 4 but oxidation state 0.

*** Iron oxides appear in a crystal structure, so no typical molecule can be identified. In ferrous oxide, Fe has oxidation state +2; in ferric oxide, oxidation state +3.

| Compound | Formula | Valence | Oxidation state | Diagram |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen | H2 | H = 1 | H = 0 | H−H |

| Chlorine | Cl2 | Cl = 1 | Cl = 0 | Cl−Cl |

| Hydrogen peroxide | H2O2 | H = 1 O = 2 | H = +1 O = −1 |

|

| Hydrazine | N2H4 | H = 1 N = 3 | H = +1 N = −2 |

|

| Disulfur decafluoride | S2F10 | S = 6 F = 1 | S = +5 F = −1 |

|

| Dithionic acid | H2S2O6 | S = 6 O = 2 H = 1 | S = +5 O = −2 H = +1 |

|

| Hexachloroethane | C2Cl6 | C = 4 Cl = 1 | C = +3 Cl = −1 |

|

| Ethylene | C2H4 | C = 4 H = 1 | C = −2 H = +1 |

|

| Acetylene | C2H2 | C = 4 H = 1 | C = −1 H = +1 | H−C≡C−H |

| Mercury(I) chloride | Hg2Cl2 | Hg = 2 Cl = 1 | Hg = +1 Cl = −1 | Cl−Hg−Hg−Cl |

«Maximum number of bonds» definition

Frankland took the view that the valence (he used the term «atomicity») of an element was a single value that corresponded to the maximum value observed. The number of unused valencies on atoms of what are now called the p-block elements is generally even, and Frankland suggested that the unused valencies saturated one another. For example, nitrogen has a maximum valence of 5, in forming ammonia two valencies are left unattached; sulfur has a maximum valence of 6, in forming hydrogen sulphide four valencies are left unattached.[17][18]

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) has made several attempts to arrive at an unambiguous definition of valence. The current version, adopted in 1994:[19]

- The maximum number of univalent atoms (originally hydrogen or chlorine atoms) that may combine with an atom of the element under consideration, or with a fragment, or for which an atom of this element can be substituted.[2]

Hydrogen and chlorine were originally used as examples of univalent atoms, because of their nature to form only one single bond. Hydrogen has only one valence electron and can form only one bond with an atom that has an incomplete outer shell. Chlorine has seven valence electrons and can form only one bond with an atom that donates a valence electron to complete chlorine’s outer shell. However, chlorine can also have oxidation states from +1 to +7 and can form more than one bond by donating valence electrons.

Hydrogen has only one valence electron, but it can form bonds with more than one atom. In the bifluoride ion ([HF2]−), for example, it forms a three-center four-electron bond with two fluoride atoms:

- [F−H F− ↔ F− H−F]

Another example is the three-center two-electron bond in diborane (B2H6).

Maximum valences of the elements

Maximum valences for the elements are based on the data from list of oxidation states of the elements. They are shown by the color code at the bottom of the table.

Maximum valences of the elements |

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | ||

| Group → | |||||||||||||||||||

| ↓ Period | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 H |

2 He |

|||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 3 Li |

4 Be |

5 B |

6 C |

7 N |

8 O |

9 F |

10 Ne |

|||||||||||

| 3 | 11 Na |

12 Mg |

13 Al |

14 Si |

15 P |

16 S |

17 Cl |

18 Ar |

|||||||||||

| 4 | 19 K |

20 Ca |

21 Sc |

22 Ti |

23 V |

24 Cr |

25 Mn |

26 Fe |

27 Co |

28 Ni |

29 Cu |

30 Zn |

31 Ga |

32 Ge |

33 As |

34 Se |

35 Br |

36 Kr |

|

| 5 | 37 Rb |

38 Sr |

39 Y |

40 Zr |

41 Nb |

42 Mo |

43 Tc |

44 Ru |

45 Rh |

46 Pd |

47 Ag |

48 Cd |

49 In |

50 Sn |

51 Sb |

52 Te |

53 I |

54 Xe |

|

| 6 | 55 Cs |

56 Ba |

71 Lu |

72 Hf |

73 Ta |

74 W |

75 Re |

76 Os |

77 Ir |

78 Pt |

79 Au |

80 Hg |

81 Tl |

82 Pb |

83 Bi |

84 Po |

85 At |

86 Rn |

|

| 7 | 87 Fr |

88 Ra |

103 Lr |

104 Rf |

105 Db |

106 Sg |

107 Bh |

108 Hs |

109 Mt |

110 Ds |

111 Rg |

112 Cn |

113 Nh |

114 Fl |

115 Mc |

116 Lv |

117 Ts |

118 Og |

|

| 57 La |

58 Ce |

59 Pr |

60 Nd |

61 Pm |

62 Sm |

63 Eu |

64 Gd |

65 Tb |

66 Dy |

67 Ho |

68 Er |

69 Tm |

70 Yb |

||||||

| 89 Ac |

90 Th |

91 Pa |

92 U |

93 Np |

94 Pu |

95 Am |

96 Cm |

97 Bk |

98 Cf |

99 Es |

100 Fm |

101 Md |

102 No |

||||||

| Maximum valences are based on the List of oxidation states of the elements | |||||||||||||||||||

|

Primordial From decay Synthetic Border shows natural occurrence of the element |

See also

- Abegg’s rule

- Oxidation state

References

- ^ a b Partington, James Riddick (1921). A text-book of inorganic chemistry for university students (1st ed.). OL 7221486M.

- ^ a b IUPAC Gold Book definition: valence

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Parkin, Gerard (May 2006). «Valence, Oxidation Number, and Formal Charge: Three Related but Fundamentally Different Concepts». Journal of Chemical Education. 83 (5): 791. doi:10.1021/ed083p791. ISSN 0021-9584.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «valence». Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ a b Partington, J.R. (1989). A Short History of Chemistry. Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-486-65977-1.

- ^ Frankland, E. (1852). «On a New Series of Organic Bodies Containing Metals». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 142: 417–444. doi:10.1098/rstl.1852.0020. S2CID 186210604.

- ^ Langmuir, Irving (1919). «The Arrangement of Electrons in Atoms and Molecules». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 41 (6): 868–934. doi:10.1021/ja02227a002.

- ^ Magnusson, Eric (1990). «Hypercoordinate molecules of second-row elements: d functions or d orbitals?». J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112 (22): 7940–7951. doi:10.1021/ja00178a014.

- ^ Frenking, Gernot; Shaik, Sason, eds. (May 2014). «Chapter 7: Chemical bonding in Transition Metal Compounds». The Chemical Bond: Chemical Bonding Across the Periodic Table. Wiley – VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-33315-8.

- ^ Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, archived from the original on 2020-05-25, retrieved 2017-05-11.

- ^ «Lesson 7: Ions and Their Names». Clackamas Community College. Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ The Free Dictionary: valence

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the «Gold Book») (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) «Oxidation number». doi:10.1351/goldbook.O04363

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the «Gold Book») (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) «Lambda». doi:10.1351/goldbook.L03418

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the «Gold Book») (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) «Oxidation state». doi:10.1351/goldbook.O04365

- ^ Frankland, E. (1870). Lecture notes for chemical students(Google eBook) (2d ed.). J. Van Voorst. p. 21.

- ^ Frankland, E.; Japp, F.R (1885). Inorganic chemistry (1st ed.). pp. 75–85. OL 6994182M.

- ^ Muller, P. (1994). «Glossary of terms used in physical organic chemistry (IUPAC Recommendations 1994)». Pure and Applied Chemistry. 66 (5): 1077–1184. doi:10.1351/pac199466051077. S2CID 195819485.

Различные химические элементы отличаются по своей способности создавать химические связи, то есть соединяться с другими атомами. Поэтому в сложных веществах они могут находиться только в определенных соотношениях. Разберемся, как определить валентность по таблице Менделеева.

Что такое валентность?

В качестве единицы используется эта характеристика для водорода, которая принята равной I. Это свойство показывает, с каким числом одновалентных атомов может соединиться данный элемент. Для кислорода эта величина всегда равна II.

Знать эту характеристику необходимо, чтобы верно записывать химические формулы веществ и уравнения реакций. Знание этой величины поможет установить соотношение между числом атомов различных типов в молекуле.

Чем поможет периодическая таблица?

Такие свойства имеют металлы главных подгрупп. Почему? Номер группы соответствует числу электронов на внешней оболочке. Эти электроны называются валентными. Именно они отвечают за возможность соединяться с другими атомами.

Группу составляют элементы с похожим устройством электронной оболочки, а сверху вниз возрастает заряд ядра. В короткопериодной форме каждая группа делится на главную и побочную подгруппы. Представители главных подгрупп — это s и p-элементы, представители побочных подгрупп имеют электроны на d и f-орбиталях.

Как определить валентность химических элементов, если она меняется? Она может совпадать с номером группы или равняться номеру группы минус восемь, а также принимать другие значения.

Важно! Чем выше и правее элемент, тем его свойство образовывать взаимосвязи меньше. Чем он более смещен вниз и влево, тем она больше.

В основном (невозбужденном) состоянии у серы два неспаренных электрона находятся на подуровне 3р. В таком состоянии она может соединиться с двумя атомами водорода и образовать сероводород. Если сера перейдет в более возбужденное состояние, то один электрон перейдет на свободный 3d-подуровень, и неспаренных электронов станет 4.

Сера станет четырехвалентной. Если сообщить ей еще больше энергии, то еще один электрон перейдет с подуровня 3s на 3d. Сера перейдет в еще более возбужденное состояние и станет шестивалентной.

Постоянная и переменная

Иногда способность к образованию химических связей может меняться. Она зависит от того, в какое соединение входит элемент. Например, сера в составе H2S двухвалентна, в составе SO2 четырехвалентна, а в SO3 — шестивалентна. Наибольшее из этих значений называется высшим, а наименьшая — низшим. Высшую и низшую валентности по таблице Менделеева можно установить так: высшая совпадает с номером группы, а низшая равняется 8 минус номер группы.

- У металлов главных подгрупп способность к образованию химических взаимосвязей постоянная.

- У металлов побочных подгрупп — переменная.

- У неметаллов — также переменная. В большинстве случаев она принимает два значения — высшее и низшее, но иногда может быть и большее число вариантов. Примеры — сера, хлор, бром, йод, хром и другие.

Это интересно! Что такое алканы: строение и химические свойства

В соединениях низшую валентность проявляет тот элемент, который находится выше и правее в периодической таблице, соответственно, высшую — тот, который левее и ниже.

Часто способность образовывать химические связи принимает больше двух значений. Тогда по таблице узнать их не получится, а нужно будет выучить. Примеры таких веществ:

- углерод,

- сера,

- хлор,

- бром.

Как определить валентность элемента в формуле соединения? Если она известна для других составляющих вещества, это несложно. Например, требуется рассчитать это свойство для хлора в NaCl. Натрий — элемент главной подгруппы первой группы, поэтому он одновалентен. Следовательно, хлор в этом веществе тоже может создать только одну связь и тоже одновалентен.

Важно! Однако так не всегда можно узнать это свойство для всех атомов в сложном веществе. Для примера возьмем HClO4. Зная свойства водорода, можно только установить, что ClO4 — одновалентный остаток.

Как еще узнать эту величину?

Способность образовывать определенное количество связей не всегда совпадает с номером группы, и в некоторых случаях ее придется просто заучить. Здесь на помощь придет таблица валентности химических элементов, где приведены значения этой величины. В учебнике химии за 8 класс приведены значения способности соединяться с другими атомами наиболее распространенных видов атомов.

| Н, F, Li, Na, K | 1 |

| O, Mg, Ca, Ba, Sr, Zn | 2 |

| B, Al | 3 |

| C, Si | 4 |

| Cu | 1, 2 |

| Fe | 2, 3 |

| Cr | 2, 3, 6 |

| S | 2, 4, 6 |

| N | 3, 4 |

| P | 3, 5 |

| Sn, Pb | 2, 4 |

| Cl, Br, I | 1, 3, 5, 7 |

Применение

Однако рассматриваемое понятие применяют в методических целях. С его помощью легко объяснить, почему атомы разных видов соединяются в тех соотношениях, которые мы наблюдаем, и почему эти соотношения для разных соединений различны. Подарки от онлайн казино можно взять на этой странице — https://www.casinobonus-ruu.com и активировать их после регистрации.

На данный момент подход, согласно которому соединение элементов в новые вещества всегда объяснялось с помощью валентности по таблице Менделеева независимо от типа связи в соединении, устарел. Сейчас мы знаем, что для ионной, ковалентной, металлической связей существуют разные механизмы объединения атомов в молекулы.

Полезное видео

Подведем итоги

По таблице Менделеева определить способность к образованию химических связей возможно не для всех элементов. Для тех, которые проявляют одну валентность по таблице Менделеева, она в большинстве случаев равна номеру группы. Если есть два варианта этой величины, то она может быть равна номеру группы или восемь минус номер группы. Существуют также специальные таблицы, по которым можно узнать эту характеристику.

На уроках химии вы уже познакомились с понятием валентности химических элементов. Мы собрали в одном месте всю полезную информацию по этому вопросу. Используйте ее, когда будете готовиться к ГИА и ЕГЭ.

Валентность и химический анализ

Валентность – способность атомов химических элементов вступать в химические соединения с атомами других элементов. Другими словами, это способность атома образовывать определенное число химических связей с другими атомами.

С латыни слово «валентность» переводится как «сила, способность». Очень верное название, правда?

Понятие «валентность» — одно из основных в химии. Было введено еще до того, как ученым стало известно строение атома (в далеком 1853 году). Поэтому по мере изучения строения атома пережило некоторые изменения.

Так, с точки зрения электронной теории валентность напрямую связана с числом внешних электронов атома элемента. Это значит, что под «валентностью» подразумевают число электронных пар, которыми атом связан с другими атомами.

Зная это, ученые смогли описать природу химической связи. Она заключается в том, что пара атомов вещества делит между собой пару валентных электронов.

Вы спросите, как же химики 19 века смогли описать валентность еще тогда, когда считали, что мельче атома частиц не бывает? Нельзя сказать, что это было так уж просто – они опирались на химический анализ.

Путем химического анализа ученые прошлого определяли состав химического соединения: сколько атомов различных элементов содержится в молекуле рассматриваемого вещества. Для этого нужно было определить, какова точная масса каждого элемента в образце чистого (без примесей) вещества.

Правда, метод этот не без изъянов. Потому что определить подобным образом валентность элемента можно только в его простом соединении со всегда одновалентным водородом (гидрид) или всегда двухвалентным кислородом (оксид). К примеру, валентность азота в NH3 – III, поскольку один атом водорода связан с тремя атомами азота. А валентность углерода в метане (СН4), по тому же принципу, – IV.

Этот метод для определения валентности годится только для простых веществ. А вот в кислотах таким образом мы можем только определить валентность соединений вроде кислотных остатков, но не всех элементов (кроме известной нам валентности водорода) по отдельности.

Как вы уже обратили внимание, обозначается валентность римскими цифрами.

Валентность и кислоты

Поскольку валентность водорода остается неизменной и хорошо вам известна, вы легко сможете определить и валентность кислотного остатка. Так, к примеру, в H2SO3 валентность SO3 – I, в HСlO3 валентность СlO3 – I.

Аналогчиным образом, если известна валентность кислотного остатка, несложно записать правильную формулу кислоты: NO2(I) – HNO2, S4O6 (II) – H2 S4O6.

Валентность и формулы

Понятие валентности имеет смысл только для веществ молекулярной природы и не слишком подходит для описания химических связей в соединениях кластерной, ионной, кристаллической природы и т.п.

Индексы в молекулярных формулах веществ отражают количество атомов элементов, которые входят в их состав. Правильно расставить индексы помогает знание валентности элементов. Таким же образом, глядя на молекулярную формулу и индексы, вы можете назвать валентности входящих в состав элементов.

Вы выполняете такие задания на уроках химии в школе. Например, имея химическую формулу вещества, в котором известна валентность одного из элементов, можно легко определить валентность другого элемента.

Для этого нужно только запомнить, что в веществе молекулярной природы число валентностей обоих элементов равны. Поэтому используйте наименьшее общее кратное (соответсвует числу свободных валентностей, необходимых для соединения), чтобы определить неизвестную вам валентность элемента.

Чтобы было понятно, возьмем формулу оксида железа Fe2O3. Здесь в образовании химической связи участвуют два атома железа с валентностью III и 3 атома кислорода с валентностью II. Наименьшим общим кратным для них является 6.

- Пример: у вас есть формулы Mn2O7. Вам известна валентность кислорода, легко вычислить, что наименьше общее кратное – 14, откуда валентность Mn – VII.

Аналогичным образом можно поступить и наоборот: записать правильную химическую формулу вещества, зная валентности входящих в него элементов.

- Пример: чтобы правильно записать формулу оксида фосфора, учтем валентность кислорода (II) и фосфора (V). Значит, наименьшее общее кратное для Р и О – 10. Следовательно, формула имеет следующий вид: Р2О5.

Хорошо зная свойства элементов, которые они проявляют в различных соединениях, можно определить их валентность даже по внешнему виду таких соединений.

Например: оксиды меди имеют красную (Cu2O) и черную (CuО) окраску. Гидроксиды меди окрашены в желтый (CuОН) и синий (Cu(ОН)2) цвета.

А чтобы ковалентные связи в веществах стали для вас более наглядными и понятными, напишите их структурные формулы. Черточки между элементами изображают возникающие между их атомами связи (валентности):

Характеристики валентности

Сегодня определение валентности элементов базируется на знаниях о строении внешних электронных оболочек их атомов.

Валентность может быть:

- постоянной (металлы главных подгрупп);

- переменной (неметаллы и металлы побочных групп):

- высшая валентность;

- низшая валентность.

Постоянной в различных химических соединениях остается:

- валентность водорода, натрия, калия, фтора (I);

- валентность кислорода, магния, кальция, цинка (II);

- валентность алюминия (III).

А вот валентность железа и меди, брома и хлора, а также многих других элементов изменяется, когда они образуют различные химические соедения.

Валентность и электронная теория

В рамках электронной теории валентность атома определеяется на основании числа непарных электронов, которые участвуют в образовании электронных пар с электронами других атомов.

В образовании химических связей участвуют только электроны, находящиеся на внешней оболочке атома. Поэтому максимальная валентность химического элемента – это число электронов во внешней электронной оболочке его атома.

Понятие валентности тесно связано с Периодическим законом, открытым Д. И. Менделеевым. Если вы внимательно посмотрите на таблицу Менделеева, легко сможете заметить: положение элемента в перодической системе и его валентность неравзрывно связаны. Высшая валентность элементов, которые относятся к одной и тоже группе, соответсвует порядковому номеру группы в периодичнеской системе.

Низшую валентность вы узнаете, когда от числа групп в таблице Менделеева (их восемь) отнимете номер группы элемента, который вас интересует.

Например, валентность многих металлов совпадает с номерами групп в таблице периодических элементов, к которым они относятся.

Таблица валентности химических элементов

|

Порядковый номер хим. элемента (атомный номер)

|

Наименование |

Химический символ |

Валентность |

| 1

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 |

Водород / Hydrogen

Гелий / Helium Литий / Lithium Бериллий / Beryllium Бор / Boron Углерод / Carbon Азот / Nitrogen Кислород / Oxygen Фтор / Fluorine Неон / Neon Натрий / Sodium Магний / Magnesium Алюминий / Aluminum Кремний / Silicon Фосфор / Phosphorus Сера / Sulfur Хлор / Chlorine Аргон / Argon Калий / Potassium Кальций / Calcium Скандий / Scandium Титан / Titanium Ванадий / Vanadium Хром / Chromium Марганец / Manganese Железо / Iron Кобальт / Cobalt Никель / Nickel Медь / Copper Цинк / Zinc Галлий / Gallium Германий /Germanium Мышьяк / Arsenic Селен / Selenium Бром / Bromine Криптон / Krypton Рубидий / Rubidium Стронций / Strontium Иттрий / Yttrium Цирконий / Zirconium Ниобий / Niobium Молибден / Molybdenum Технеций / Technetium Рутений / Ruthenium Родий / Rhodium Палладий / Palladium Серебро / Silver Кадмий / Cadmium Индий / Indium Олово / Tin Сурьма / Antimony Теллур / Tellurium Иод / Iodine Ксенон / Xenon Цезий / Cesium Барий / Barium Лантан / Lanthanum Церий / Cerium Празеодим / Praseodymium Неодим / Neodymium Прометий / Promethium Самарий / Samarium Европий / Europium Гадолиний / Gadolinium Тербий / Terbium Диспрозий / Dysprosium Гольмий / Holmium Эрбий / Erbium Тулий / Thulium Иттербий / Ytterbium Лютеций / Lutetium Гафний / Hafnium Тантал / Tantalum Вольфрам / Tungsten Рений / Rhenium Осмий / Osmium Иридий / Iridium Платина / Platinum Золото / Gold Ртуть / Mercury Талий / Thallium Свинец / Lead Висмут / Bismuth Полоний / Polonium Астат / Astatine Радон / Radon Франций / Francium Радий / Radium Актиний / Actinium Торий / Thorium Проактиний / Protactinium Уран / Uranium |

H

He Li Be B C N O F Ne Na Mg Al Si P S Cl Ar K Ca Sc Ti V Cr Mn Fe Co Ni Сu Zn Ga Ge As Se Br Kr Rb Sr Y Zr Nb Mo Tc Ru Rh Pd Ag Cd In Sn Sb Te I Xe Cs Ba La Ce Pr Nd Pm Sm Eu Gd Tb Dy Ho Er Tm Yb Lu Hf Ta W Re Os Ir Pt Au Hg Tl Pb Bi Po At Rn Fr Ra Ac Th Pa U |

I

0 I II III (II), IV (I), II, III, IV, V II I 0 I II III (II), IV I, III, V II, IV, VI I, (II), III, (IV), V, VII 0 I II III II, III, IV II, III, IV, V II, III, VI II, (III), IV, VI, VII II, III, (IV), VI II, III, (IV) (I), II, (III), (IV) I, II, (III) II (II), III II, IV (II), III, V (II), IV, VI I, (III), (IV), V 0 I II III (II), (III), IV (II), III, (IV), V (II), III, (IV), (V), VI VI (II), III, IV, (VI), (VII), VIII (II), (III), IV, (VI) II, IV, (VI) I, (II), (III) (I), II (I), (II), III II, IV III, (IV), V (II), IV, VI I, (III), (IV), V, VII 0 I II III III, IV III III, IV III (II), III (II), III III III, IV III III III (II), III (II), III III IV (III), (IV), V (II), (III), (IV), (V), VI (I), II, (III), IV, (V), VI, VII (II), III, IV, VI, VIII (I), (II), III, IV, VI (I), II, (III), IV, VI I, (II), III I, II I, (II), III II, IV (II), III, (IV), (V) II, IV, (VI) нет данных 0 нет данных II III IV V (II), III, IV, (V), VI |

В скобках даны те валентности, которые обладающие ими элементы проявляют редко.

Валентность и степень окисления

Понятие валентности можно считать родственным такой характеристике, как степень окисления. Тем не менее, обе эти характеристики не тождественным друг другу.

Так, говоря о степени окисления, подразумевают, что атом в веществе ионной (что важно) природы имеет некий условный заряд. И если валентность – это нейтральная характеристика, то степень окисления может быть отрицательной, положительной или равной нулю.

Интересно, что для атома одного и того же элемента, в зависимости от элементов, с которыми он образует химическое соединение, валентность и степень окисления могут совпадать (Н2О, СН4 и др.) и различаться (Н2О2, HNO3).

Заключение

Углубляя свои знания о строении атомов, вы глубже и подробнее узнаете и валентность. Эта характеристика химических элементов не является исчерпывающей. Но у нее большое прикладное значение. В чем вы сами не раз убедились, решая задачи и проводя химические опыты на уроках.

Эта статья создана, чтобы помочь вам систематизировать свои знания о валентности. А также напомнить, как можно ее определить и где валентность находит применение.

Надеемся, этот материал окажется для вас полезным при подготовке домашних заданий и самоподготовке к контрольным и экзаменам.

Не забудьте поделиться ссылкой с друзьями в социальных сетях, чтобы они тоже могли воспользоваться этой полезной информацией.

© blog.tutoronline.ru,

при полном или частичном копировании материала ссылка на первоисточник обязательна.

Валентность химических элементов (Таблица)

Валентность химических элементов – это способность у атомов хим. элементов образовывать некоторое число химических связей. Принимает значения от 1 до 8 и не может быть равна 0. Определяется числом электронов атома затраченых на образование хим. связей с другим атомом. Валентность это реальная величина. Обозначается римскими цифрами (I ,II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII).

Как можно определить валентность в соединениях:

— Валентность водорода (H) постоянна всегда 1. Отсюда в соединении H2O валентность O равна 2.

— Валентность кислорода (O) постоянна всегда 2. Отсюда в соединении СО2 валентность С равно 4.

— Высшая валентность всегда равна № группы.

— Низшая валентность равна разности между числом 8 (количество групп в Таблице Менделеева) и номером группы, в которой находится элемент.

— У металлов в подгруппах А таблицы Менделеева, валентность = № группы.

— У неметаллов обычно две валентности: высшая и низшая.

Валентность химических элементов может быть постоянной и переменной. Постоянная в основном у металлов главных подгрупп, переменная у неметаллов и металлов побочных подгруп.

Таблица валентности химических элементов

|

Атомный № |

Химический элемент |

Символ |

Валентность химических элементов |

Примеры соединений |

|

1 |

Водород / Hydrogen |

H |

I |

HF |

|

2 |

Гелий / Helium |

He |

отсутствует |

— |

|

3 |

Литий / Lithium |

Li |

I |

Li2O |

|

4 |

Бериллий / Beryllium |

Be |

II |

BeH2 |

|

5 |

Бор / Boron |

B |

III |

BCl3 |

|

6 |

Углерод / Carbon |

C |

IV, II |

CO2, CH4 |

|

7 |

Азот / Nitrogen |

N |

I, II, III, IV |

NH3 |

|

8 |

Кислород / Oxygen |

O |

II |

H2O, BaO |

|

9 |

Фтор / Fluorine |

F |

I |

HF |

|

10 |

Неон / Neon |

Ne |

отсутствует |

— |

|

11 |

Натрий / Sodium |

Na |

I |

Na2O |

|

12 |

Магний / Magnesium |

Mg |

II |

MgCl2 |

|

13 |

Алюминий / Aluminum |

Al |

III |

Al2O3 |

|

14 |

Кремний / Silicon |

Si |

IV |

SiO2, SiCl4 |

|

15 |

Фосфор / Phosphorus |

P |

III, V |

PH3, P2O5 |

|

16 |

Сера / Sulfur |

S |

VI, IV, II |

H2S, SO3 |

|

17 |

Хлор / Chlorine |

Cl |

I, III, V, VII |

HCl, ClF3 |

|

18 |

Аргон / Argon |

Ar |

отсутствует |

— |

|

19 |

Калий / Potassium |

K |

I |

KBr |

|

20 |

Кальций / Calcium |

Ca |

II |

CaH2 |

|

21 |

Скандий / Scandium |

Sc |

III |

Sc2S3 |

|

22 |

Титан / Titanium |

Ti |

II, III, IV |

Ti2O3, TiH4 |

|

23 |

Ванадий / Vanadium |

V |

II, III, IV, V |

VF5, V2O3 |

|

24 |

Хром / Chromium |

Cr |

II, III, VI |

CrCl2, CrO3 |

|

25 |

Марганец / Manganese |

Mn |

II, III, IV, VI, VII |

Mn2O7, Mn2(SO4)3 |

|

26 |

Железо / Iron |

Fe |

II, III |

FeSO4, FeBr3 |

|

27 |

Кобальт / Cobalt |

Co |

II, III |

CoI2, Co2S3 |

|

28 |

Никель / Nickel |

Ni |

II, III, IV |

NiS, Ni(CO)4 |

|

29 |

Медь / Copper |

Сu |

I, II |

CuS, Cu2O |

|

30 |

Цинк / Zinc |

Zn |

II |

ZnCl2 |

|

31 |

Галлий / Gallium |

Ga |

III |

Ga(OH)3 |

|

32 |

Германий / Germanium |

Ge |

II, IV |

GeBr4, Ge(OH)2 |

|

33 |

Мышьяк / Arsenic |

As |

III, V |

As2S5, H3AsO4 |

|

34 |

Селен / Selenium |

Se |

II, IV, VI, |

H2SeO3 |

|

35 |

Бром / Bromine |

Br |

I, III, V, VII |

HBrO3 |

|

36 |

Криптон / Krypton |

Kr |

VI, IV, II |

KrF2, BaKrO4 |

|

37 |

Рубидий / Rubidium |

Rb |

I |

RbH |

|

38 |

Стронций / Strontium |

Sr |

II |

SrSO4 |

|

39 |

Иттрий / Yttrium |

Y |

III |

Y2O3 |

|

40 |

Цирконий / Zirconium |

Zr |

II, III, IV |

ZrI4, ZrCl2 |

|

41 |

Ниобий / Niobium |

Nb |

I, II, III, IV, V |

NbBr5 |

|

42 |

Молибден / Molybdenum |

Mo |

II, III, IV, V, VI |

Mo2O5, MoF6 |

|

43 |

Технеций / Technetium |

Tc |

I — VII |

Tc2S7 |

|

44 |

Рутений / Ruthenium |

Ru |

II — VIII |

RuO4, RuF5, RuBr3 |

|

45 |

Родий / Rhodium |

Rh |

I, II, III, IV, V |

RhS, RhF3 |

|

46 |

Палладий / Palladium |

Pd |