КАК ОГОНЬ ИЗМЕНИЛ ЖИЗНЬ ЧЕЛОВЕКА

Одним из наиболее важным шагом в развитии человечества стало освоение огня. Благодаря этому факту первобытные люди получили в свои руки грозное оружие против хищников, возможность употреблять в пищу, приготовленную на огне, обогреваться в холода и освещать свои жилища.

Когда человек впервые научился осознанно пользоваться огнём?

Освоили огонь ещё австралопитеки. В Восточной Африке на стоянках древнего человека возле озёр Баринго и Кооби-Фора археологи обнаружили осколки глины, которые явно побывали в огне для придания им твёрдости. Возраст находок — 1,42-1,5 миллиона лет. Были и другие доказательства, которые свидетельствовали об употреблении нашими предками огня.

Однако бесспорные доказательства массового применения огня относятся к более поздним временам. Так, в Южной Африке в пещере Cave of Hearths (что переводится с английского как «Пещера очагов») нашли обгоревшие камни возрастом от 200 до 700 тысяч лет, а в Замбии на стоянке первобытных людей близ водопада Каламбо, были найдены дрова, древесный уголь, обожжённая глина и деревянные изделия, по всей видимости побывавшие в огне. Возраст находок — от 61 до 110 тысяч лет.

Есть и свидетельства применения огня в археологических находках на Ближнем Востоке. Предположительно ещё около 700 тысяч лет и огонь помогал древним людям освещать место для разделки туш животных, добытых на охоте.

Подобные находки в возрасте до полутора миллионов лет есть по всему миру: в Китае, Франции, Венгрии, Испании и других странах.

Как огонь повлиял на жизнь человека?

Дикие животные и кровососущие насекомые боялись огня и дыма и избегали стоянки человека. Люди получили возможность жить в более безопасной и комфортной обстановке.

Современные учёные утверждают, что пища, приготовленная на огне способствовала развитию головного мозга, так как содержащийся в некоторых плодах крахмал лучше усваивался, давал больше энергии и нужных веществ для усиления умственной деятельности.

Также люди стали употреблять в пищу части растений, которые без обработки на огне человек просто не мог есть: стебли, корни, листья. К тому же при варке разрушались некоторые растительные яды, что тоже улучшило качество питания гоминидов, знакомых с огнём.

Температурная обработка убивала и болезнетворные микроорганизмы, живущие в мясе, помогала лучше усваивать животный белок, то есть, человек стал наедаться меньшим количеством пищи и при этом стал реже болеть. Например, зубы стали теперь служить человеку дольше, так как меньше изнашивались на варёной и жареной пище, чем на разжёвывании сырого мяса и растений.

Непривычную точку зрения на причины быстрого распространения первых технологий добычи огня предложили исследователи из Нидерландов.

Освоение огня по праву считается одним из важнейших этапов социальной эволюции человека. С помощью огня люди наконец перестали зависеть от короткого светового дня, научились отпугивать хищников, готовить пищу, обогревать жилище.

Около миллиона лет назад ныне вымершие виды людей уже использовали огонь, однако существует мало доказательств его регулярного и преднамеренного разведения.

Учёные из Лейденского университета в Нидерландах считают, что технология зажигания огня распространилась подобно лесному пожару около 400 тысяч лет назад на территории Африки, Европы и Азии. При этом происходило это совершенно не случайным образом.

Исследователи сделали дерзкий вывод: популяции древних людей обменивались технологиями ещё до появления человека разумного, которого принято считать «изобретателем» культуры и социума.

Авторы работы, опубликованной в издании PNAS, считают освоение огня древними человеческими популяциями первым археологическим признаком культурной диффузии у древних людей.

«До сегодняшнего дня считалось, что культурная диффузия по-настоящему началась лишь 70 тысяч лет назад, когда [по миру] начали распространяться современные люди, Homo sapiens, — объясняет ведущий автор работы Кэтрин Макдональд (Katharine MacDonald) из Лейденского университета. — Однако свидетельства использования огня теперь показывают, что, похоже, это произошло гораздо раньше».

Авторы работы отмечают, что люди начали регулярно использовать огонь со второй половины среднего плейстоцена (около 400 тысяч лет назад). Более ранние признаки использования огня человеком редки и неоднозначны.

Однако в какой-то момент на стоянках древнего человека на территории Северной Африки, Израиля, Азии и Европы начали всё чаще появляться следы разведения огня, такие как обгоревшие кости, уголь и термически обработанная порода.

Конечно же, не исключено, что разрозненные популяции людей на разных континентах получили навык разведения огня независимо друг от друга. Но относительно быстрое его распространение по всему Старому Свету (Европе, Азии и Африке) всё же указывает на то, что этот навык передавался от человека к человеку. Причём таким образом он распространялся даже за пределы отдельной популяции.

Получается, миф о Прометее, укравшем у богов огонь и подарившем его людям, может отчасти отражать реальность: некий первооткрыватель поделился своим «ноу-хау» с другими людьми. И молва пошла по миру…

Кроме того, освоение огня не было единственным навыком, который столь быстро распространился среди разных человеческих популяций того времени.

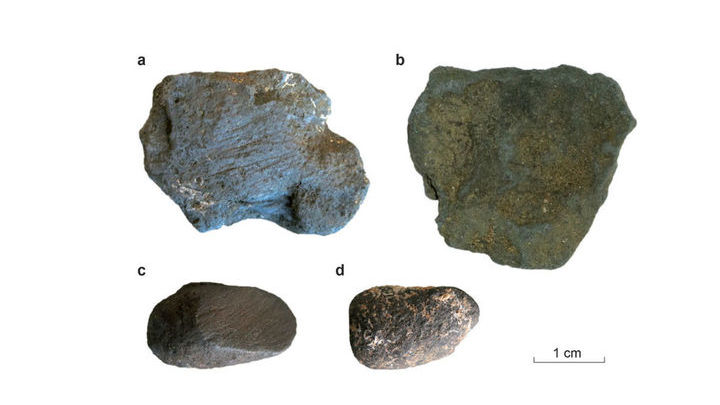

Примерно через 100 тысяч лет после «бума» технологии разжигания огня такое же активное развитие получила индустрия Леваллуа — особая технология обработки каменных орудий.

Ещё быстрее, чем использование огня, индустрия Леваллуа распространилась на территории Северо-Западной Европы и Ближнего Востока. При этом сама технология Леваллуа была гораздо сложнее, чем технология добычи огня: чтобы научиться обрабатывать камень определённым образом, требовались время и наработка опыта.

Это значит, что для передачи новых техник и методов было недостаточно случайных коротких встреч представителей разных человеческих популяций.

Орудие, изготовленное по технологии Леваллуа.

Авторы нового исследования считают, что такое «скоростное» развитие примитивных технологий требовало создания достаточно стабильных социальных связей между популяциями, жившими в разных местах.

Если предположения исследователей из Нидерландов верны, это значит, что масштабные социальные сети существовали ещё до появления Homo sapiens «на мировой арене».

Эта радикальная гипотеза открывает новое поле для пылких научных дискуссий.

Даже если это предположение не получит широкой поддержки, оно, без сомнения, привлечёт внимание к вопросу об уникальности современной человеческой культуры. Ведь, как известно, нет дыма без огня.

К слову, недавно мы сообщали о том, что неандертальцы создавали «предметы искусства» ещё до прихода человека разумного. Также последнее время появляется всё больше генетических свидетельств того, что разные виды древних людей скрещивались между собой. Так, на территории Китая недавно был обнаружен неизвестный ранее вымерший родственник Homo sapiens.

Больше новостей из мира науки вы найдёте в разделе «Наука» на медиаплатформе «Смотрим».

История человечества полна различных загадок, и чем древнее дата, тем таинственнее событие и его обстоятельства, что касается как обретения членораздельной речи и перехода к прямохождению, так и вопроса о том, когда люди научились добывать огонь. О том, что этот навык резко изменил жизнь далеких предков современных людей, спорить не приходится. Улучшилось качество пищи, что не могло не повлиять на продолжительность жизни. В условиях оледенения, приходящегося именно на начальные этапы существования человека, огонь помогал согреться. Незаменим он был и при охоте.

Первобытный человек и огонь

Очень многие природные явления, так или иначе, связаны с огнем. Более миллиона лет назад извержения вулканов происходили чаще, чем сейчас, и представляли серьезную опасность для всех животных, в том числе и для человека. Еще один вариант столкновения с огнем — не менее частые лесные и степные пожары.

Однако если внимательнее присмотреться к мифологии, то выясняется, что первый полученный человеком огонь был небесного происхождения. Наиболее известен греческий миф, согласно которому Прометей похитил искру из кузнечного горна Гефеста и принес ее людям, спрятав в пустой тростинке. Схожие предания имелись и у других народов, в том числе у различных индейских племен, которые не могли контактировать с греками. Ввиду этого предположение, что первобытные люди впервые воспользовались огнем от возгорания чего-либо после удара молнии, рассматривается учеными как наиболее вероятное.

Искусственное разведение огня

Наиболее важным и сложным для первобытного человека было преодолеть природный страх перед огнем. Когда же это произошло, он не мог не обнаружить, что вовсе не обязательно ждать сильной грозы или извержения вулкана: при создании каменных орудий труда в результате ударов одного камня о другой вспыхивали искры. Однако этот способ был очень трудоемким и занимал по меньшей мере час. В областях расселения человека, где существовала высокая влажность, он и вовсе был невозможен.

Еще один физический процесс, дающий представление о том, как древние люди научились добывать огонь, — трение. С течением времени человек удостоверился, что еще сильнее упрощает процедуру не просто трение, а сверление. Для этого использовалось сухое дерево. Упирая в него сухую палку, человек быстро вращал ее между ладоней. В дереве образовывалось углубление, в котором скапливался древесный порошок. При высокой интенсивности движений он вспыхивал, и уже можно было разводить костер.

Поддержание огня

Если вновь обратиться к мифологии, становится ясно, что когда люди научились добывать огонь, они были весьма озабочены его поддержанием. Например, даже римские обычаи требовали, чтобы в храме богини Весты находились жрицы, занятые сохранением неугасимого огня на ее алтаре. Даже возжигание свечей в христианских храмах многими учеными считается пережитком первобытной необходимости хранить огонь.

Этнографические данные показывают: хотя люди научились добывать огонь и максимально упростили этот процесс, сохранение уже имеющегося было в приоритете. Это понятно: не всегда можно было найти подходящие камни или сухое дерево. Между тем без огня племени грозила смерть. Индейцы не только поддерживали неугасимые костры у своих хижин, но и носили с собой тлеющий трут. Скорее всего, так себя вел и первобытный человек.

Проблема датировки

Нельзя окончательно поставить точку в споре о том, в какой период люди научились добывать огонь. Исследователь может рассчитывать только на данные археологии, а от человеческих стоянок возрастом в миллион лет осталось чрезвычайно мало. Именно поэтому ученые предпочитают использовать широкие датировки. Сходясь во мнениях о том, что добывать огонь человек научился в эпоху палеолита, специалисты по истории первобытного общества указывают, что это могло произойти в промежуток с 1,4 млн до 780 тыс. лет назад.

Удревнить это событие на 300 тысяч лет помогли находки в пещере Вондерверк на территории Южноафриканской Республики. Команде археологов под руководством Питера Бомона удалось обнаружить культурный слой, в котором сохранились остатки древесной золы и обугленные кости животных. Дальнейшие исследования показали, что их сожжение происходило непосредственно в пещере, то есть возможность их случайного попадания туда исключена. На стенах пещеры были обнаружены следы копоти.

Человек-первооткрыватель

Благодаря этим открытиям был вновь поставлен вопрос о том, какой человек научился добывать огонь. Миллион лет назад род Homo был представлен различными видами, из которых выжил лишь один — Homo sapiens (Человек разумный). Реконструкция антропогенеза осложняется небольшим количеством материальных свидетельств о существовании того или иного вида, то есть скелетных останков. Ввиду этого существование таких видов, как Homo rudolfensis, является дискуссионным вопросом.

Если расположить на одной шкале этапы антропогенеза и свидетельства о том, когда люди научились добывать огонь, то самая ранняя точка приходится на существование вида Homo erectus (Человек прямоходящий). Но было ли умение добывать огонь уже привычным, или же это происходило от случая к случаю, выяснить пока невозможно.

Значение овладения огнем

Когда люди научились искусственно добывать огонь, их эволюция значительно ускорилась. Изменения затронули даже их внешний вид. Использование огня в приготовлении пищи позволило значительно увеличить расход энергии. Если обычное животное в течении жизни расходует около 125 ккал на килограмм веса, то человек — в шесть раз больше.

Овладение огнем резко выделило человека из ряда других животных. Благодаря огню стало возможным эффективнее преследовать крупных хищников и загонять их в ловушки, защищать свои стоянки от вторжения. Применялся огонь и для обработки деревянных орудий труда, что делало их более прочными и твердыми.

Затронуло это событие и ментальную сферу. Когда люди научились добывать огонь, он сразу же стал объектом поклонения. Стали складываться различные религиозные культы, в которых бог огня занимал центральное положение. Поэтому вряд ли будет натянутым предположение, что именно овладение огнем позволило человеку достичь сегодняшних высот.

«Control of fire» redirects here. For the process of suppressing or extinguishing a fire, see Fire control. For components that assist weapon systems, see Fire-control system.

The control of fire by early humans was a critical technology enabling the evolution of humans. Fire provided a source of warmth and lighting, protection from predators (especially at night), a way to create more advanced hunting tools, and a method for cooking food. These cultural advances allowed human geographic dispersal, cultural innovations, and changes to diet and behavior. Additionally, creating fire allowed human activity to continue into the dark and colder hours of the evening.

Claims for the earliest definitive evidence of control of fire by a member of Homo range from 1.7 to 2.0 million years ago (Mya).[1] Evidence for the «microscopic traces of wood ash» as controlled use of fire by Homo erectus, beginning roughly 1 million years ago, has wide scholarly support.[2][3] Some of the earliest known traces of controlled fire were found at the Daughters of Jacob Bridge, Israel, and dated to ~790,000 years ago.[4] At the site, archaeologists also found the oldest of controlled use of fire to cook food ~780,000 years ago.[5][6] However, some studies suggest cooking started ~1.8 million years ago.[7][8][clarification needed]

Flint blades burned in fires roughly 300,000 years ago were found near fossils of early but not entirely modern Homo sapiens in Morocco.[9] Fire was used regularly and systematically by early modern humans to heat treat silcrete stone to increase its flake-ability for the purpose of toolmaking approximately 164,000 years ago at the South African site of Pinnacle Point.[10] Evidence of widespread control of fire by anatomically modern humans dates to approximately 125,000 years ago.[11]

Control of fire[edit]

The use and control of fire was a gradual process proceeding through more than one stage. One was a change in habitat, from dense forest, where wildfires were common, to savanna (mixed grass/woodland) where wildfires were of higher intensity.[citation needed][clarification needed] Such a change may have occurred about 3 million years ago, when the savanna expanded in East Africa due to cooler and drier climate.[12][13]

The next stage involved interaction with burned landscapes and foraging in the wake of wildfires, as observed in various wild animals.[12][13] In the African savanna, animals that preferentially forage in recently burned areas include savanna chimpanzees (a variety of Pan troglodytes verus),[12][14] vervet monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops)[15] and a variety of birds, some of which also hunt insects and small vertebrates in the wake of grass fires.[14][16]

The next step would be to make some use of residual hot spots that occur in the wake of wildfires. For example, foods found in the wake of wildfires tend to be either burned or undercooked. This might have provided incentives to place undercooked foods on a hotspot or to pull food out of the fire if it was in danger of getting burned. This would require familiarity with fire and its behavior.[17][13]

An early step in the control of fire would have been transporting it from burned to unburned areas and lighting them on fire, providing advantages in food acquisition.[13] Maintaining a fire over an extended period of time, as for a season (such as the dry season), may have led to the development of base campsites. Building a hearth or other fire enclosure such as a circle of stones would have been a later development.[18] The ability to make fire, generally with a friction device with hardwood rubbing against softwood (as in a bow drill), was a later development.[12]

Each of these stages could occur at different intensities, ranging from occasional or «opportunistic» to «habitual» to «obligate» (unable to survive without it).[13][18]

Lower Paleolithic evidence[edit]

Most of the evidence of controlled use of fire during the Lower Paleolithic is uncertain and has limited scholarly support.[19] Some of the evidence is inconclusive because other plausible explanations exist, such as natural processes, for the findings.[20] Recent findings support that the earliest known controlled use of fire took place in Wonderwerk Cave, South Africa, 1.0 Mya.[19][21]

Africa[edit]

Findings from the Wonderwerk Cave site, in the Northern Cape province of South Africa, provide the earliest evidence for controlled use of fire. Intact sediments were analyzed using micromorphological analysis and Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopy (mFTIR) and yielded evidence, in the form of burned bones and ashed plant remains, that burning took place at the site 1.0 Mya.[19]

East African sites, such as Chesowanja near Lake Baringo, Koobi Fora, and Olorgesailie in Kenya, show some possible evidence that fire was controlled by early humans.[20]

In Chesowanja, archaeologists found red clay clasts dated to 1.4 Mya. These clasts must have been heated to 400 °C (750 °F) to harden. However, tree stumps burned in bush fires in East Africa produce clasts, which, when broken by erosion, are like those described at Chesownja. Controlled use of fire at Chesowanja is unproven.[20]

In Koobi Fora, sites show evidence of control of fire by Homo erectus at 1.5 Mya with findings of reddened sediment that could come from heating at 200–400 °C (400–750 °F).[20]

Evidence of possible human control of fire, found at Swartkrans, South Africa,[22] includes several burned bones, including ones with hominin-inflicted cut marks, along with Acheulean and bone tools.[20] This site also shows some of the earliest evidence of carnivorous behavior in H. Erectus.

A «hearth-like depression» that could have been used to burn bones was found at a site in Olorgesailie, Kenya. However, it did not contain any charcoal, and no signs of fire have been observed. Some microscopic charcoal was found, but it could have resulted from a natural brush fire.[20]

In Gadeb, Ethiopia, fragments of welded tuff that appeared to have been burned were found in Locality 8E but refiring of the rocks might have occurred due to local volcanic activity.[20]

In the Middle Awash River Valley, cone-shaped depressions of reddish clay were found that could have been formed by temperatures of 200 °C (400 °F). These features, thought to have been created by burning tree stumps, were hypothesized to have been produced by early hominids lighting tree stumps so they could have fire away from their habitation site. This view is not widely accepted, though.[20] Burned stones are also found in Awash Valley, but volcanic welded tuff is also found in the area, which could explain the burned stones.[20]

Burned flints discovered near Jebel Irhoud, Morocco, dated by thermoluminescence to around 300,000 years old, were discovered in the same sedimentary layer as skulls of early Homo sapiens. Paleoanthropologist Jean-Jacques Hublin believes the flints were used as spear tips and left in fires used by the early humans for cooking food.[9]

Asia[edit]

In Xihoudu in Shanxi Province, China, the black, blue, and grayish-green discoloration of mammalian bones found at the site illustrates the evidence of burning by early hominids. In 1985, at a parallel site in China, Yuanmou in Yunnan Province, archaeologists found blackened mammal bones that date back to 1.7 Mya.[20]

Middle East[edit]

A site at Bnot Ya’akov Bridge, Israel, has been claimed to show that H. erectus or H. ergaster controlled fires between 790,000 and 690,000 BP.[23] An AI powered spectroscopy in archaeology has helped researchers unearth hidden evidence of the use of fire by humans dating 800,000 and 1 million years ago.[24] In an article published in June 2022,[25] researchers from Weizmann Institute of Science, who pioneered the AI application, along with researchers at University of Toronto and Hebrew University of Jerusalem described the use of deep learning models to analyze heat exposure of 26 flint tools that were found in 1970s at the Evron Quarry in the northwest of Israel. The results showed that the tools were heated up to 600°C.[24]

Pacific Islands[edit]

At Trinil, Java, burned wood has been found in layers that carried H. erectus (Java Man) fossils dating from 830,000 to 500,000 BP.[20] The burned wood has been claimed to indicate the use of fire by early hominids.

Middle Paleolithic evidence[edit]

Africa[edit]

The Cave of Hearths in South Africa has burn deposits, which date from 700,000 to 200,000 BP, as do various other sites such as Montagu Cave (200,000 to 58,000 BP) and the Klasies River Mouth (130,000 to 120,000 BP).[20]

Strong evidence comes from Kalambo Falls in Zambia, where several artifacts related to the use of fire by humans have been recovered, including charred logs, charcoal, carbonized grass stems and plants, and wooden implements, which may have been hardened by fire. The site has been dated through radiocarbon dating to between 110,000 BP and 61,000 BP through amino-acid racemization.[20]

Fire was used for heat treatment of silcrete stones to increase their workability before they were knapped into tools by Stillbay culture in South Africa.[26][27][28] These Stillbay sites date back from 164,000 to 72,000 years ago, with the heat treatment of stone beginning by about 164,000 years ago.[26]

Asia[edit]

Evidence at Zhoukoudian cave in China suggests control of fire as early as 460,000 to 230,000 BP.[11] Fire in Zhoukoudian is suggested by the presence of burned bones, burned chipped-stone artifacts, charcoal, ash, and hearths alongside H. erectus fossils in Layer 10, the earliest archaeological horizon at the site.[20][29] This evidence comes from Locality 1, also known as the Peking Man site, where several bones were found to be uniformly black to grey. The extracts from the bones were determined to be characteristic of burned bone rather than manganese staining. These residues also showed IR spectra for oxides, and a bone that was turquoise was reproduced in the laboratory by heating some of the other bones found in Layer 10. At the site, the same effect might have been due to natural heating, as the effect was produced on white, yellow, and black bones.[29]

Layer 10 itself is described as ash with biologically produced silicon, aluminum, iron, and potassium, but wood ash remnants such as siliceous aggregates are missing. Among these are possible hearths «represented by finely laminated silt and clay interbedded with reddish-brown and yellow brown fragments of organic matter, locally mixed with limestone fragments and dark brown finely laminated silt, clay, and organic matter.»[29] The site itself does not show that fires were made in Zhoukoudian, but the association of blackened bones with quartzite artifacts at least shows that humans did control fire at the time of the habitation of the Zhoukoudian cave.

Middle East[edit]

At the Amudian site of Qesem Cave, near the city of Kfar Qasim, Israel, evidence exists of the regular use of fire from before 382,000 BP to around 200,000 BP, at the end of Lower Pleistocene. Large quantities of burned bone and moderately heated soil lumps were found, and the cut marks found on the bones suggest that butchering and prey-defleshing took place near fireplaces.[30] In addition, hominins living in Qesem cave managed to heat their flint to varying temperatures before knapping it into different tools.[31]

Indian Subcontinent[edit]

The earliest evidence for controlled fire use by humans on the Indian subcontinent, dating to between 50,000 and 55,000 years ago, comes from the Main Belan archaeological site, located in the Belan River valley in Uttar Pradesh, India.[32]

Europe[edit]

Multiple sites in Europe, such as Torralba and Ambrona, Spain, and St. Esteve-Janson, France, have also shown evidence of use of fire by later versions of H. erectus. The oldest has been found in England at the site of Beeches Pit, Suffolk; uranium series dating and thermoluminescence dating place the use of fire at 415,000 BP.[33] At Vértesszőlős, Hungary, while no charcoal has been found, burned bones have been discovered dating from c. 350,000 years ago. At Torralba and Ambrona, Spain, objects such as Acheulean stone tools, remains of large mammals such as extinct elephants, charcoal, and wood were discovered.[20] At Terra Amata in France, there is a fireplace with ashes (dated between 380,000 BP and 230,000 BP). At Saint-Estève-Janson in France, there is evidence of five hearths and reddened earth in the Escale Cave; these hearths have been dated to 200,000 BP.[20] Evidence for fire making dates to at least the Middle Paleolithic, with dozens of Neanderthal hand axes from France exhibiting use-wear traces suggesting these tools were struck with the mineral pyrite to produce sparks around 50,000 years ago.[34]

Impact on human evolution[edit]

Cultural innovation[edit]

Uses of fire by early humans[edit]

The discovery of fire came to provide a wide variety of uses for early hominids. Its warmth kept them alive during low nighttime temperatures in colder environments, allowing geographic expansion from tropical and subtropical climates to temperate areas. Its blaze warded off predatory animals, especially in the dark.[35]

Fire also played a major role in changing food habits. Cooking allowed a significant increase in meat consumption and calorie intake.[35] It was soon discovered that meat could also be dried and smoked by fire, preserving it for lean seasons.[36] Fire was even used in manufacturing tools for hunting and butchering.[37] Hominids also learned that starting bush fires to burn large areas could increase land fertility and clear terrain to make hunting easier.[36][38] Evidence shows that early hominids were able to corral and trap prey animals by means of fire.[citation needed] Fire was used to clear out caves prior to living in them, helping to begin the use of shelter.[39] The many uses of fire may have led to specialized social roles, such as the separation of cooking from hunting.[40]

The control of fire enabled important changes in human behavior, health, energy expenditure, and geographic expansion. Hominids could move into much colder regions that would have previously been uninhabitable after the loss of body hair. Evidence of more complex management to change biomes can be found as far back as 200,000 to 100,000 years ago at a minimum.

Tool and weapon making[edit]

Fire also allowed major innovations in tool and weapon manufacture. In an archeological dig that dates to around 400,000 years ago, researchers excavating in the ‘Spear Horizon’ in Schöningen, Germany, unearthed eight wooden spears among a trove of preserved artifacts.[41][42] The spears were found along with stone tools and horse remains, one of which still had a spear through its pelvis. At another dig site located in Lehringen, Germany, a fire-hardened lance was found thrust into the rib cage of a ‘straight-tusked elephant’.[43] These archeological digs provide evidence that the spears were deliberately fire-hardened, allowing early humans to use the spears as thrusting rather than throwing weapons. Researchers further uncovered environmental evidence that these early hunters may have hidden in ambush.[42][44]

More recent evidence dating to roughly 164,000 years ago indicates that early humans in South Africa during the Middle Stone Age used fire to alter the mechanical properties of tool materials applying heat treatment to a fine-grained rock called silcrete.[45] The heated rocks were then tempered into crescent-shaped blades or arrowheads for hunting and butchering prey. This may have been the first time that bow and arrow were used for hunting, with far-ranging impact.[45][46]

Art and ceramics[edit]

Fire was also used in the creation of art. Archaeologists have discovered several 1- to 10-inch Venus figurine statues in Europe dating to the Paleolithic, several carved from stone and ivory, others shaped from clay and then fired. These are some of the earliest examples of ceramics.[47] Fire was also commonly used to create pottery. Although pottery was formerly thought to have begun with the Neolithic around 10,000 years ago, scientists in China discovered pottery fragments in the Xianrendong Cave that were about 20,000 years old.[48] During the Neolithic Age and agricultural revolution about 10,000 years ago, pottery became far more common and widespread, often carved and painted with simple linear designs and geometric shapes.[49]

Social development and nighttime activity[edit]

Fire was an important factor in expanding and developing societies of early hominids. One impact fire might have had was social stratification. The power to make and wield fire may have conferred prestige and social position.[36] Fire also led to a lengthening of daytime activities, and allowed more nighttime activities.[50] Evidence of large hearths indicate that the majority of nighttime was spent around the fire.[51] The increased social interaction from gathering around the fire may have fostered the development of language.[50]

Another effect of fire use on hominid societies was that it required larger groups to work together to maintain the fire, finding fuel, portioning it onto the fire, and re-igniting it when necessary. These larger groups might have included older individuals such as grandparents, who helped to care for children. Ultimately, fire had a significant influence on the size and social interactions of early hominid communities.[50][51]

Exposure to artificial light during later hours of the day changed humans’ circadian rhythms, contributing to a longer waking day.[52] The modern human’s waking day is 16 hours, while many mammals are only awake for half as many hours.[51] Additionally, humans are most awake during the early evening hours, while other primates’ days begin at dawn and end at sundown. Many of these behavioral changes can be attributed to the control of fire and its impact on daylight extension.[51]

The cooking hypothesis[edit]

The cooking hypothesis proposes the idea that the ability to cook allowed for the brain size of hominids to increase over time. This idea was first presented by Friedrich Engels in the article «The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man» and later recapitulated in the book Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human by Richard Wrangham and then in a book by Suzana Herculano-Houzel.[53] Critics of the hypothesis argue that cooking with controlled fire was insufficient to start the increasing brain size trend.

The cooking hypothesis gains support by comparing the nutrients in raw food to the much more easily digested nutrients in cooked food, as in an examination of protein ingestion from raw vs. cooked egg.[54] Scientists have found that among several primates, the restriction of feeding to raw foods during daylight hours limits the metabolic energy available.[55] Genus Homo was able to break through the limit by cooking food to shorten their feeding times and be able to absorb more nutrients to accommodate the increasing need for energy.[56] In addition, scientists argue that the Homo species was also able to obtain nutrients like docosahexaenoic acid from algae that were especially beneficial and critical for brain evolution, and the detoxification of food by the cooking process enabled early humans to access these resources.[57]

Besides the brain, other human organs also demand a high metabolism.[56] During human evolution, the body-mass proportion of different organs changed to allow brain expansion.

Changes to diet[edit]

Before the advent of fire, the hominid diet was limited to mostly plant parts composed of simple sugars and carbohydrates such as seeds, flowers, and fleshy fruits. Parts of the plant such as stems, mature leaves, enlarged roots, and tubers would have been inaccessible as a food source due to the indigestibility of raw cellulose and starch. Cooking, however, made starchy and fibrous foods edible and greatly increased the diversity of other foods available to early humans. Toxin-containing foods including seeds and similar carbohydrate sources, such as cyanogenic glycosides found in linseed and cassava, were incorporated into their diets as cooking rendered them nontoxic.[58]

Cooking could also kill parasites, reduce the amount of energy required for chewing and digestion, and release more nutrients from plants and meat. Due to the difficulty of chewing raw meat and digesting tough proteins (e.g. collagen) and carbohydrates, the development of cooking served as an effective mechanism to efficiently process meat and allow for its consumption in larger quantities. With its high caloric density and content of important nutrients, meat thus became a staple in the diet of early humans.[59] By increasing digestibility, cooking allowed hominids to maximize the energy gained from consuming foods. Studies show that caloric intake from cooking starches improves 12-35% and 45-78% for protein. As a result of the increases in net energy gain from food consumption, survival and reproductive rates in hominids increased.[60] Through lowering food toxicity and increasing nutritive yield, cooking allowed for an earlier weaning age, permitting females to have more children.[61] In this way, too, it facilitated population growth.

It has been proposed that the use of fire for cooking caused environmental toxins to accumulate in the placenta, which led to a species-wide taboo on human placentophagy around the time of the mastery of fire. Placentophagy is common in other primates.[62]

Biological changes[edit]

Before their use of fire, the hominid species had large premolars, which were used to chew harder foods, such as large seeds. In addition, due to the shape of the molar cusps, the diet is inferred to have been more leaf- or fruit-based. Probably in response to consuming cooked foods, the molar teeth of H. erectus gradually shrank, suggesting that their diet had changed from tougher foods such as crisp root vegetables to softer cooked foods such as meat.[63][64] Cooked foods further selected for the differentiation of their teeth and eventually led to a decreased jaw volume with a variety of smaller teeth in hominids. Today, a smaller jaw volume and teeth size of humans is seen in comparison to other primates.[65]

Due to the increased digestibility of many cooked foods, less digestion was needed to procure the necessary nutrients. As a result, the gastrointestinal tract and organs in the digestive system decreased in size. This is in contrast to other primates, where a larger digestive tract is needed for fermentation of long carbohydrate chains. Thus, humans evolved from the large colons and tracts that are seen in other primates to smaller ones.[66]

According to Wrangham, control of fire allowed hominids to sleep on the ground and in caves instead of trees and led to more time being spent on the ground. This may have contributed to the evolution of bipedalism, as such an ability became increasingly necessary for human activity.[67]

Criticism[edit]

Critics of the hypothesis argue that while a linear increase in brain volume of the genus Homo is seen over time, adding fire control and cooking does not add anything meaningful to the data. Species such as H. ergaster existed with large brain volumes during time periods with little to no evidence of fire for cooking. Little variation exists in the brain sizes of H. erectus dated from periods of weak and strong evidence for cooking.[51] An experiment involving mice fed raw versus cooked meat found that cooking meat did not increase the amount of calories taken up by mice, leading to the study’s conclusion that the energetic gain is the same, if not greater, in raw meat diets than cooked meats.[68] Studies such as this and others have led to criticisms of the hypothesis that state that the increases in human brain-size occurred well before the advent of cooking due to a shift away from the consumption of nuts and berries to the consumption of meat.[69][70] Other anthropologists argue that the evidence suggests that cooking fires began in earnest only 250,000 BP, when ancient hearths, earth ovens, burned animal bones, and flint appear across Europe and the Middle East.[71]

See also[edit]

- Hunting hypothesis

- Savannah hypothesis

- Raw foodism

- Theft of fire

References[edit]

- ^ James, Steven R. (February 1989). «Hominid Use of Fire in the Lower and Middle Pleistocene: A Review of the Evidence» (PDF). Current Anthropology. 30 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1086/203705. S2CID 146473957. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ Luke, Kim. «Evidence That Human Ancestors Used Fire One Million Years Ago». Retrieved 27 October 2013.

An international team led by the University of Toronto and Hebrew University has identified the earliest known evidence of the use of fire by human ancestors. Microscopic traces of wood ash, alongside animal bones and stone tools, were found in a layer dated to one million years ago

- ^ Berna, Francesco (2012). «Microstratigraphic evidence of in situ fire in the Acheulean strata of Wonderwerk Cave, Northern Cape province, South Africa». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (20): E1215-20. doi:10.1073/pnas.1117620109. PMC 3356665. PMID 22474385.

- ^ Goren-Inbar, Naama; Alperson, Nira; Kislev, Mordechai E.; Simchoni, Orit; Melamed, Yoel; Ben-Nun, Adi; Werker, Ella (30 April 2004). «Evidence of Hominin Control of Fire at Gesher Benot Ya’aqov, Israel». Science. 304 (5671): 725–727. Bibcode:2004Sci…304..725G. doi:10.1126/science.1095443. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 15118160. S2CID 8444444.

- ^ «Ancient human relative used fire, surprising discoveries suggest». Washington Post. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ Zohar, Irit; Alperson-Afil, Nira; Goren-Inbar, Naama; Prévost, Marion; Tütken, Thomas; Sisma-Ventura, Guy; Hershkovitz, Israel; Najorka, Jens (December 2022). «Evidence for the cooking of fish 780,000 years ago at Gesher Benot Ya’aqov, Israel». Nature Ecology & Evolution. 6 (12): 2016–2028. doi:10.1038/s41559-022-01910-z. ISSN 2397-334X. PMID 36376603. S2CID 253522354.

- ^ Organ, Chris (22 August 2011). «Phylogenetic rate shifts in feeding time during the evolution of Homo». PNAS. 108 (35): 14555–14559. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10814555O. doi:10.1073/pnas.1107806108. PMC 3167533. PMID 21873223.

- ^ Bentsen, Silje (27 October 2020). «Fire Use». Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Anthropology. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190854584.013.52. ISBN 978-0-19-085458-4.

- ^ a b Zimmer, Carl (7 June 2017). «Oldest Fossils of Homo Sapiens Found in Morocco, Altering History of Our Species». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ^ Brown, Kyle S.; Marean, Curtis W.; Herries, Andy I.R.; Jacobs, Zenobia; Tribolo, Chantal; Braun, David; Roberts, David L.; Meyer, Michael C.; Bernatchez, J. (14 August 2009), «Fire as an Engineering Tool of Early Modern Humans», Science, 325 (5942): 859–862, Bibcode:2009Sci…325..859B, doi:10.1126/science.1175028, hdl:11422/11102, PMID 19679810, S2CID 43916405

- ^ a b «First Control of Fire by Human Beings – How Early?». Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- ^ a b c d Pruetz, Jill D.; Herzog, Nicole M. (2017). «Savanna Chimpanzees at Fongoli, Senegal, Navigate a Fire Landscape». Current Anthropology. 58: S000. doi:10.1086/692112. ISSN 0011-3204. S2CID 148782684.

- ^ a b c d e Parker, Christopher H.; Keefe, Earl R.; Herzog, Nicole M.; O’connell, James F.; Hawkes, Kristen (2016). «The pyrophilic primate hypothesis». Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews. 25 (2): 54–63. doi:10.1002/evan.21475. ISSN 1060-1538. PMID 27061034. S2CID 22744464.

- ^ a b Gowlett, J. A. J. (2016). «The discovery of fire by humans: a long and convoluted process». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 371 (1696): 20150164. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0164. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 4874402. PMID 27216521.

- ^ Herzog, Nicole M.; Parker, Christopher H.; Keefe, Earl R.; Coxworth, James; Barrett, Alan; Hawkes, Kristen (2014). «Fire and home range expansion: A behavioral response to burning among savanna dwelling vervet monkeys (Chlorocebusaethiops)». American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 154 (4): 554–60. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22550. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 24889076.

- ^ Burton, Frances D. (29 September 2011). «2». Fire: The Spark That Ignited Human Evolution. UNM Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-8263-4648-3. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ^ Gowlett, J. A. J.; Brink, J. S.; Caris, Adam; Hoare, Sally; Rucina, S. M. (2017). «Evidence of Burning from Bushfires in Southern and East Africa and Its Relevance to Hominin Evolution». Current Anthropology. 58 (S16): S206–S216. doi:10.1086/692249. ISSN 0011-3204. S2CID 164509111.

- ^ a b Chazan, Michael (2017). «Toward a Long Prehistory of Fire». Current Anthropology. 58: S000. doi:10.1086/691988. ISSN 0011-3204. S2CID 149271414.

- ^ a b c Berna, Francesco; Goldberg, Paul; Horwitz, Liora Kolska; Brink, James; Holt, Sharon; Bamford, Marion; Chazan, Michael (15 May 2012). «Microstratigraphic evidence of in situ fire in the Acheulean strata of Wonderwerk Cave, Northern Cape province, South Africa». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (20): E1215–20. doi:10.1073/pnas.1117620109. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3356665. PMID 22474385.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p James, Steven R. (February 1989). «Hominid Use of Fire in the Lower and Middle Pleistocene: A Review of the Evidence» (PDF). Current Anthropology. 30 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1086/203705. S2CID 146473957. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ Gowlett, J. A. J. (23 May 2016). «The discovery of fire by humans: a long and convoluted process». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 371 (1696): 20150164. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0164. PMC 4874402. PMID 27216521.

- ^ Renfrew and Bahn (2004). Archaeology: Theories, Methods and Practice (Fourth Edition). Thames and Hudson, p. 341

- ^ Rincon, Paul (29 April 2004). «Early human fire skills revealed». BBC News. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- ^ a b «The heat is on: Traces of fire uncovered dating back at least 800,000 years: Using advanced AI techniques, researchers discover one of the earliest pieces of evidence for the use of fire». ScienceDaily. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ Stepka, Zane; Azuri, Ido; Horwitz, Liora Kolska; Chazan, Michael; Natalio, Filipe (21 June 2022). «Hidden signatures of early fire at Evron Quarry (1.0 to 0.8 Mya)». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (25): e2123439119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11923439S. doi:10.1073/pnas.2123439119. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 9231470. PMID 35696581.

- ^ a b Brown, KS; Marean, CW; Herries, AI; Jacobs, Z; Tribolo, C; Braun, D; Roberts, DL; Meyer, MC; Bernatchez, J (2009). «Fire As an Engineering Tool of Early Modern Humans». Science. 325 (5942): 859–62. Bibcode:2009Sci…325..859B. doi:10.1126/science.1175028. hdl:11422/11102. PMID 19679810. S2CID 43916405.

- ^ Webb, J. Domanski M. (2009). «Fire and Stone». Science. 325 (5942): 820–21. Bibcode:2009Sci…325..820W. doi:10.1126/science.1178014. PMID 19679799. S2CID 206521911.

- ^ Callaway. E. (13 August 2009) Earliest fired knives improved stone age tool kit New Scientist, online

- ^ a b c Weiner, S.; Q. Xu; P. Goldberg; J. Liu; O. Bar-Yosef (1998). «Evidence for the Use of Fire at Zhoukoudian, China». Science. 281 (5374): 251–53. Bibcode:1998Sci…281..251W. doi:10.1126/science.281.5374.251. PMID 9657718.

- ^ Karkanas P, Shahack-Gross R, Ayalon A, et al. (August 2007). «Evidence for habitual use of fire at the end of the Lower Paleolithic: site-formation processes at Qesem Cave, Israel» (PDF). J. Hum. Evol. 53 (2): 197–212. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.04.002. PMID 17572475.

- ^ Agam, Aviad; Azuri, Ido; Pinkas, Iddo; Gopher, Avi; Natalio, Filipe (2020). «Estimating temperatures of heated Lower Palaeolithic flint artefacts» (PDF). Nature Human Behaviour. 5 (2): 221–228. doi:10.1038/s41562-020-00955-z. PMID 33020589. S2CID 222160202.

- ^ Jha, Deepak Kumar; Samrat, Rahul; Sanyal, Prasanta (15 January 2021). «The first evidence of controlled use of fire by prehistoric humans during the Middle Paleolithic phase from the Indian subcontinent». Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 562: 110151. Bibcode:2021PPP…562k0151J. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2020.110151. S2CID 229392002. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Preece, R. C. (2006). «Humans in the Hoxnian: habitat, context and fire use at Beeches Pit, West Stow, Suffolk, UK». Journal of Quaternary Science. 21 (5): 485–96. Bibcode:2006JQS….21..485P. doi:10.1002/jqs.1043.

- ^ Sorensen, A. C.; Claud, E.; Soressi, M. (19 July 2018). «Neandertal fire-making technology inferred from microwear analysis». Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 10065. Bibcode:2018NatSR…810065S. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-28342-9. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6053370. PMID 30026576.

- ^ a b «Archaeologists Find Earliest Evidence of Humans Cooking With Fire | DiscoverMagazine.com». Discover Magazine. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ a b c McKenna, Ryan. «Fire and It’s [sic] Value to Early Man». fubini.Swarthmore.edu. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ «When Did Man Discover Fire? Ancestors of Modern Humans Used Fire 350,000 Years Ago, New Study Suggests». International Business Times. 15 December 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ Bellomo, Randy V. (1 July 1994). «Methods of determining early hominid behavioral activities associated with the controlled use of fire at FxJj 20 Main, Koobi Fora, Kenva». Journal of Human Evolution. 27 (1): 173–195. doi:10.1006/jhev.1994.1041.

- ^ Washburn, S. L. (11 October 2013). Social Life of Early Man. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-54361-6.

- ^ Yin, Steph (5 August 2016). «Smoke, Fire and Human Evolution». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ Brown, Kyle S.; Marean, Curtis W.; Herries, Andy I. R.; Jacobs, Zenobia; Tribolo, Chantal; Braun, David; Roberts, David L.; Meyer, Michael C.; Bernatchez, Jocelyn (14 August 2009). «Fire As an Engineering Tool of Early Modern Humans». Science. 325 (5942): 859–862. Bibcode:2009Sci…325..859B. doi:10.1126/science.1175028. hdl:11422/11102. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 19679810. S2CID 43916405.

- ^ a b Schoch, Werner H.; Bigga, Gerlinde; Böhner, Utz; Richter, Pascale; Terberger, Thomas (1 December 2015). «New insights on the wooden weapons from the Paleolithic site of Schöningen». Journal of Human Evolution. Special Issue: Excavations at Schöningen: New Insights into Middle Pleistocene Lifeways in Northern Europe. 89: 214–225. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.08.004. PMID 26442632.

- ^ Alperson-Afil, Nira; Goren-Inbar, Naama (1 January 2010). The Acheulian Site of Gesher Benot Ya’aqov Volume II. Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology. Springer Netherlands. pp. 73–98. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.368.7748. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-3765-7_4. ISBN 978-90-481-3764-0.

- ^ Böhner, Utz; Serangeli, Jordi; Richter, Pascale (1 December 2015). «The Spear Horizon: First spatial analysis of the Schöningen site 13 II-4». Journal of Human Evolution. Special Issue: Excavations at Schöningen: New Insights into Middle Pleistocene Lifeways in Northern Europe. 89: 202–213. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.10.001. PMID 26626956.

- ^ a b Delagnes, Anne; Schmidt, Patrick; Douze, Katja; Wurz, Sarah; Bellot-Gurlet, Ludovic; Conard, Nicholas J.; Nickel, Klaus G.; Niekerk, Karen L. van; Henshilwood, Christopher S. (19 October 2016). «Early Evidence for the Extensive Heat Treatment of Silcrete in the Howiesons Poort at Klipdrift Shelter (Layer PBD, 65 ka), South Africa». PLOS ONE. 11 (10): e0163874. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1163874D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0163874. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5070848. PMID 27760210.

- ^ «Humans used fire earlier than previously known | University of Bergen». www.uib.no. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ Jennett, Karen. «Female Figurines of the Upper Paleolithic» (PDF). TxState.Edu. Texas State University, San Marcos. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ «The Earliest Known Pottery». Popular Archaeology. Archived from the original on 8 November 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ Lamoureux, Michael. «What we know of early human society & behavior». Sourcing Innovation. Sourcing Innovation. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ a b c Dunbar, R. I. M.; Gamble, Clive; Gowlett, J. A. J. (13 November 2016). Lucy to Language: The Benchmark Papers. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-965259-4.

- ^ a b c d e Gowlett, J. a. J. (5 June 2016). «The discovery of fire by humans: a long and convoluted process». Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 371 (1696): 20150164. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0164. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 4874402. PMID 27216521.

- ^ Wiessner, Polly W. (30 September 2014). «Embers of society: Firelight talk among the Ju/’hoansi Bushmen». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (39): 14027–14035. doi:10.1073/pnas.1404212111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4191796. PMID 25246574.

- ^ Herculano-Houzel, Suzana (2016). Human AdvantageA New Understanding of How Our Brain Became Remarkable – MIT Press Scholarship. doi:10.7551/mitpress/9780262034258.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-262-03425-8.

- ^ Evenepoel, Pieter; Geypens, Benny; Luypaerts, Anja; Hiele, Martin; Ghoos, Yvo; Rutgeerts, Paul (1 October 1998). «Digestibility of Cooked and Raw Egg Protein in Humans as Assessed by Stable Isotope Techniques». The Journal of Nutrition. 128 (10): 1716–1722. doi:10.1093/jn/128.10.1716. ISSN 0022-3166. PMID 9772141.

- ^ Fonseca-Azevedo, Karina; Herculano-Houzel, Suzana (6 November 2012). «Metabolic constraint imposes tradeoff between body size and number of brain neurons in human evolution». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (45): 18571–18576. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10918571F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1206390109. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3494886. PMID 23090991.

- ^ a b Aiello, Leslie C.; Wheeler, Peter (1 January 1995). «The Expensive-Tissue Hypothesis: The Brain and the Digestive System in Human and Primate Evolution». Current Anthropology. 36 (2): 199–221. doi:10.1086/204350. JSTOR 2744104. S2CID 144317407.

- ^ Bradbury, Joanne (10 May 2011). «Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA): An Ancient Nutrient for the Modern Human Brain». Nutrients. 3 (5): 529–554. doi:10.3390/nu3050529. PMC 3257695. PMID 22254110.

- ^ Stahl, Ann Brower (April 1984). «Hominid Dietary Selection Before Fire». Current Anthropology. 25 (2): 151–168. doi:10.1086/203106. S2CID 84337150.

- ^ Luca, F., G.H. Perry, and A. Di Rienzo. «Evolutionary Adaptations to Dietary Changes.» Annual Review of Nutrition. U.S. National Library of Medicine, 21 August 2010. Weborn 14 November 2016.

- ^ Wrangham, Richard W.; Carmody, Rachel Naomi (2010). «Human adaptation to the control of fire» (PDF). Evolutionary Anthropology. 19 (5): 187–199. doi:10.1002/evan.20275. S2CID 34878981.

- ^ Daniel Lieberman, L’histoire du corps humain, JC Lattès, 2015, p. 99

- ^ Young, Sharon M.; Benyshek, Daniel C.; Lienard, Pierre (May 2012). «The Conspicuous Absence of Placenta Consumption in Human Postpartum Females: The Fire Hypothesis». Ecology of Food and Nutrition. 51 (3): 198–217. doi:10.1080/03670244.2012.661349. PMID 22632060. S2CID 1279726.

- ^ Viegas, Jennifer (22 November 2005). «Homo erectus ate crunchy food». News in Science. abc.net.au. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- ^ «Early Human Evolution: Homo ergaster and erectus». Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- ^ Pickrell, John (19 February 2005). «Human ‘dental chaos’ linked to evolution of cooking». Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- ^ Gibbons, Ann (15 June 2007). «Food for Thought». Science. 316 (5831): 1558–60. doi:10.1126/science.316.5831.1558. PMID 17569838. S2CID 9071168.

- ^ Adler, Jerry. «Why Fire Makes Us Human». Smithsonian. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ Cornélio, Alianda; et al. (2016). «Human Brain Expansion during Evolution Is Independent of Fire Control and Cooking». Frontiers in Neuroscience. 10: 167. doi:10.3389/fnins.2016.00167. PMC 4842772. PMID 27199631.

- ^ «Meat-eating was essential for human evolution, says UC Berkeley anthropologist specializing in diet». 14 June 1999. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- ^ Mann, Neil (15 August 2007). «Meat in the human diet: An anthropological perspective». Nutrition & Dietetics. 64 (Supplement s4): 102–107. doi:10.1111/j.1747-0080.2007.00194.x.

- ^ Pennisi, Elizabeth (26 March 1999). «Human evolution: Did Cooked Tubers Spur the Evolution of Big Brains?». Science. 283 (5410): 2004–2005. doi:10.1126/science.283.5410.2004. PMID 10206901. S2CID 39775701.

External links[edit]

- «How our pact with fire made us what we are» Archived 6 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine—Article by Stephen J Pyne

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian (August

How (and when) did humans first make fire? — archaeologist Andrew Sorensen (Leiden University)

2016).

«Control of fire» redirects here. For the process of suppressing or extinguishing a fire, see Fire control. For components that assist weapon systems, see Fire-control system.

The control of fire by early humans was a critical technology enabling the evolution of humans. Fire provided a source of warmth and lighting, protection from predators (especially at night), a way to create more advanced hunting tools, and a method for cooking food. These cultural advances allowed human geographic dispersal, cultural innovations, and changes to diet and behavior. Additionally, creating fire allowed human activity to continue into the dark and colder hours of the evening.

Claims for the earliest definitive evidence of control of fire by a member of Homo range from 1.7 to 2.0 million years ago (Mya).[1] Evidence for the «microscopic traces of wood ash» as controlled use of fire by Homo erectus, beginning roughly 1 million years ago, has wide scholarly support.[2][3] Some of the earliest known traces of controlled fire were found at the Daughters of Jacob Bridge, Israel, and dated to ~790,000 years ago.[4] At the site, archaeologists also found the oldest of controlled use of fire to cook food ~780,000 years ago.[5][6] However, some studies suggest cooking started ~1.8 million years ago.[7][8][clarification needed]

Flint blades burned in fires roughly 300,000 years ago were found near fossils of early but not entirely modern Homo sapiens in Morocco.[9] Fire was used regularly and systematically by early modern humans to heat treat silcrete stone to increase its flake-ability for the purpose of toolmaking approximately 164,000 years ago at the South African site of Pinnacle Point.[10] Evidence of widespread control of fire by anatomically modern humans dates to approximately 125,000 years ago.[11]

Control of fire[edit]

The use and control of fire was a gradual process proceeding through more than one stage. One was a change in habitat, from dense forest, where wildfires were common, to savanna (mixed grass/woodland) where wildfires were of higher intensity.[citation needed][clarification needed] Such a change may have occurred about 3 million years ago, when the savanna expanded in East Africa due to cooler and drier climate.[12][13]

The next stage involved interaction with burned landscapes and foraging in the wake of wildfires, as observed in various wild animals.[12][13] In the African savanna, animals that preferentially forage in recently burned areas include savanna chimpanzees (a variety of Pan troglodytes verus),[12][14] vervet monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops)[15] and a variety of birds, some of which also hunt insects and small vertebrates in the wake of grass fires.[14][16]

The next step would be to make some use of residual hot spots that occur in the wake of wildfires. For example, foods found in the wake of wildfires tend to be either burned or undercooked. This might have provided incentives to place undercooked foods on a hotspot or to pull food out of the fire if it was in danger of getting burned. This would require familiarity with fire and its behavior.[17][13]

An early step in the control of fire would have been transporting it from burned to unburned areas and lighting them on fire, providing advantages in food acquisition.[13] Maintaining a fire over an extended period of time, as for a season (such as the dry season), may have led to the development of base campsites. Building a hearth or other fire enclosure such as a circle of stones would have been a later development.[18] The ability to make fire, generally with a friction device with hardwood rubbing against softwood (as in a bow drill), was a later development.[12]

Each of these stages could occur at different intensities, ranging from occasional or «opportunistic» to «habitual» to «obligate» (unable to survive without it).[13][18]

Lower Paleolithic evidence[edit]

Most of the evidence of controlled use of fire during the Lower Paleolithic is uncertain and has limited scholarly support.[19] Some of the evidence is inconclusive because other plausible explanations exist, such as natural processes, for the findings.[20] Recent findings support that the earliest known controlled use of fire took place in Wonderwerk Cave, South Africa, 1.0 Mya.[19][21]

Africa[edit]

Findings from the Wonderwerk Cave site, in the Northern Cape province of South Africa, provide the earliest evidence for controlled use of fire. Intact sediments were analyzed using micromorphological analysis and Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopy (mFTIR) and yielded evidence, in the form of burned bones and ashed plant remains, that burning took place at the site 1.0 Mya.[19]

East African sites, such as Chesowanja near Lake Baringo, Koobi Fora, and Olorgesailie in Kenya, show some possible evidence that fire was controlled by early humans.[20]

In Chesowanja, archaeologists found red clay clasts dated to 1.4 Mya. These clasts must have been heated to 400 °C (750 °F) to harden. However, tree stumps burned in bush fires in East Africa produce clasts, which, when broken by erosion, are like those described at Chesownja. Controlled use of fire at Chesowanja is unproven.[20]

In Koobi Fora, sites show evidence of control of fire by Homo erectus at 1.5 Mya with findings of reddened sediment that could come from heating at 200–400 °C (400–750 °F).[20]

Evidence of possible human control of fire, found at Swartkrans, South Africa,[22] includes several burned bones, including ones with hominin-inflicted cut marks, along with Acheulean and bone tools.[20] This site also shows some of the earliest evidence of carnivorous behavior in H. Erectus.

A «hearth-like depression» that could have been used to burn bones was found at a site in Olorgesailie, Kenya. However, it did not contain any charcoal, and no signs of fire have been observed. Some microscopic charcoal was found, but it could have resulted from a natural brush fire.[20]

In Gadeb, Ethiopia, fragments of welded tuff that appeared to have been burned were found in Locality 8E but refiring of the rocks might have occurred due to local volcanic activity.[20]

In the Middle Awash River Valley, cone-shaped depressions of reddish clay were found that could have been formed by temperatures of 200 °C (400 °F). These features, thought to have been created by burning tree stumps, were hypothesized to have been produced by early hominids lighting tree stumps so they could have fire away from their habitation site. This view is not widely accepted, though.[20] Burned stones are also found in Awash Valley, but volcanic welded tuff is also found in the area, which could explain the burned stones.[20]

Burned flints discovered near Jebel Irhoud, Morocco, dated by thermoluminescence to around 300,000 years old, were discovered in the same sedimentary layer as skulls of early Homo sapiens. Paleoanthropologist Jean-Jacques Hublin believes the flints were used as spear tips and left in fires used by the early humans for cooking food.[9]

Asia[edit]

In Xihoudu in Shanxi Province, China, the black, blue, and grayish-green discoloration of mammalian bones found at the site illustrates the evidence of burning by early hominids. In 1985, at a parallel site in China, Yuanmou in Yunnan Province, archaeologists found blackened mammal bones that date back to 1.7 Mya.[20]

Middle East[edit]

A site at Bnot Ya’akov Bridge, Israel, has been claimed to show that H. erectus or H. ergaster controlled fires between 790,000 and 690,000 BP.[23] An AI powered spectroscopy in archaeology has helped researchers unearth hidden evidence of the use of fire by humans dating 800,000 and 1 million years ago.[24] In an article published in June 2022,[25] researchers from Weizmann Institute of Science, who pioneered the AI application, along with researchers at University of Toronto and Hebrew University of Jerusalem described the use of deep learning models to analyze heat exposure of 26 flint tools that were found in 1970s at the Evron Quarry in the northwest of Israel. The results showed that the tools were heated up to 600°C.[24]

Pacific Islands[edit]

At Trinil, Java, burned wood has been found in layers that carried H. erectus (Java Man) fossils dating from 830,000 to 500,000 BP.[20] The burned wood has been claimed to indicate the use of fire by early hominids.

Middle Paleolithic evidence[edit]

Africa[edit]

The Cave of Hearths in South Africa has burn deposits, which date from 700,000 to 200,000 BP, as do various other sites such as Montagu Cave (200,000 to 58,000 BP) and the Klasies River Mouth (130,000 to 120,000 BP).[20]

Strong evidence comes from Kalambo Falls in Zambia, where several artifacts related to the use of fire by humans have been recovered, including charred logs, charcoal, carbonized grass stems and plants, and wooden implements, which may have been hardened by fire. The site has been dated through radiocarbon dating to between 110,000 BP and 61,000 BP through amino-acid racemization.[20]

Fire was used for heat treatment of silcrete stones to increase their workability before they were knapped into tools by Stillbay culture in South Africa.[26][27][28] These Stillbay sites date back from 164,000 to 72,000 years ago, with the heat treatment of stone beginning by about 164,000 years ago.[26]

Asia[edit]

Evidence at Zhoukoudian cave in China suggests control of fire as early as 460,000 to 230,000 BP.[11] Fire in Zhoukoudian is suggested by the presence of burned bones, burned chipped-stone artifacts, charcoal, ash, and hearths alongside H. erectus fossils in Layer 10, the earliest archaeological horizon at the site.[20][29] This evidence comes from Locality 1, also known as the Peking Man site, where several bones were found to be uniformly black to grey. The extracts from the bones were determined to be characteristic of burned bone rather than manganese staining. These residues also showed IR spectra for oxides, and a bone that was turquoise was reproduced in the laboratory by heating some of the other bones found in Layer 10. At the site, the same effect might have been due to natural heating, as the effect was produced on white, yellow, and black bones.[29]

Layer 10 itself is described as ash with biologically produced silicon, aluminum, iron, and potassium, but wood ash remnants such as siliceous aggregates are missing. Among these are possible hearths «represented by finely laminated silt and clay interbedded with reddish-brown and yellow brown fragments of organic matter, locally mixed with limestone fragments and dark brown finely laminated silt, clay, and organic matter.»[29] The site itself does not show that fires were made in Zhoukoudian, but the association of blackened bones with quartzite artifacts at least shows that humans did control fire at the time of the habitation of the Zhoukoudian cave.

Middle East[edit]

At the Amudian site of Qesem Cave, near the city of Kfar Qasim, Israel, evidence exists of the regular use of fire from before 382,000 BP to around 200,000 BP, at the end of Lower Pleistocene. Large quantities of burned bone and moderately heated soil lumps were found, and the cut marks found on the bones suggest that butchering and prey-defleshing took place near fireplaces.[30] In addition, hominins living in Qesem cave managed to heat their flint to varying temperatures before knapping it into different tools.[31]

Indian Subcontinent[edit]

The earliest evidence for controlled fire use by humans on the Indian subcontinent, dating to between 50,000 and 55,000 years ago, comes from the Main Belan archaeological site, located in the Belan River valley in Uttar Pradesh, India.[32]

Europe[edit]

Multiple sites in Europe, such as Torralba and Ambrona, Spain, and St. Esteve-Janson, France, have also shown evidence of use of fire by later versions of H. erectus. The oldest has been found in England at the site of Beeches Pit, Suffolk; uranium series dating and thermoluminescence dating place the use of fire at 415,000 BP.[33] At Vértesszőlős, Hungary, while no charcoal has been found, burned bones have been discovered dating from c. 350,000 years ago. At Torralba and Ambrona, Spain, objects such as Acheulean stone tools, remains of large mammals such as extinct elephants, charcoal, and wood were discovered.[20] At Terra Amata in France, there is a fireplace with ashes (dated between 380,000 BP and 230,000 BP). At Saint-Estève-Janson in France, there is evidence of five hearths and reddened earth in the Escale Cave; these hearths have been dated to 200,000 BP.[20] Evidence for fire making dates to at least the Middle Paleolithic, with dozens of Neanderthal hand axes from France exhibiting use-wear traces suggesting these tools were struck with the mineral pyrite to produce sparks around 50,000 years ago.[34]

Impact on human evolution[edit]

Cultural innovation[edit]

Uses of fire by early humans[edit]

The discovery of fire came to provide a wide variety of uses for early hominids. Its warmth kept them alive during low nighttime temperatures in colder environments, allowing geographic expansion from tropical and subtropical climates to temperate areas. Its blaze warded off predatory animals, especially in the dark.[35]

Fire also played a major role in changing food habits. Cooking allowed a significant increase in meat consumption and calorie intake.[35] It was soon discovered that meat could also be dried and smoked by fire, preserving it for lean seasons.[36] Fire was even used in manufacturing tools for hunting and butchering.[37] Hominids also learned that starting bush fires to burn large areas could increase land fertility and clear terrain to make hunting easier.[36][38] Evidence shows that early hominids were able to corral and trap prey animals by means of fire.[citation needed] Fire was used to clear out caves prior to living in them, helping to begin the use of shelter.[39] The many uses of fire may have led to specialized social roles, such as the separation of cooking from hunting.[40]

The control of fire enabled important changes in human behavior, health, energy expenditure, and geographic expansion. Hominids could move into much colder regions that would have previously been uninhabitable after the loss of body hair. Evidence of more complex management to change biomes can be found as far back as 200,000 to 100,000 years ago at a minimum.

Tool and weapon making[edit]

Fire also allowed major innovations in tool and weapon manufacture. In an archeological dig that dates to around 400,000 years ago, researchers excavating in the ‘Spear Horizon’ in Schöningen, Germany, unearthed eight wooden spears among a trove of preserved artifacts.[41][42] The spears were found along with stone tools and horse remains, one of which still had a spear through its pelvis. At another dig site located in Lehringen, Germany, a fire-hardened lance was found thrust into the rib cage of a ‘straight-tusked elephant’.[43] These archeological digs provide evidence that the spears were deliberately fire-hardened, allowing early humans to use the spears as thrusting rather than throwing weapons. Researchers further uncovered environmental evidence that these early hunters may have hidden in ambush.[42][44]

More recent evidence dating to roughly 164,000 years ago indicates that early humans in South Africa during the Middle Stone Age used fire to alter the mechanical properties of tool materials applying heat treatment to a fine-grained rock called silcrete.[45] The heated rocks were then tempered into crescent-shaped blades or arrowheads for hunting and butchering prey. This may have been the first time that bow and arrow were used for hunting, with far-ranging impact.[45][46]

Art and ceramics[edit]

Fire was also used in the creation of art. Archaeologists have discovered several 1- to 10-inch Venus figurine statues in Europe dating to the Paleolithic, several carved from stone and ivory, others shaped from clay and then fired. These are some of the earliest examples of ceramics.[47] Fire was also commonly used to create pottery. Although pottery was formerly thought to have begun with the Neolithic around 10,000 years ago, scientists in China discovered pottery fragments in the Xianrendong Cave that were about 20,000 years old.[48] During the Neolithic Age and agricultural revolution about 10,000 years ago, pottery became far more common and widespread, often carved and painted with simple linear designs and geometric shapes.[49]

Social development and nighttime activity[edit]

Fire was an important factor in expanding and developing societies of early hominids. One impact fire might have had was social stratification. The power to make and wield fire may have conferred prestige and social position.[36] Fire also led to a lengthening of daytime activities, and allowed more nighttime activities.[50] Evidence of large hearths indicate that the majority of nighttime was spent around the fire.[51] The increased social interaction from gathering around the fire may have fostered the development of language.[50]

Another effect of fire use on hominid societies was that it required larger groups to work together to maintain the fire, finding fuel, portioning it onto the fire, and re-igniting it when necessary. These larger groups might have included older individuals such as grandparents, who helped to care for children. Ultimately, fire had a significant influence on the size and social interactions of early hominid communities.[50][51]

Exposure to artificial light during later hours of the day changed humans’ circadian rhythms, contributing to a longer waking day.[52] The modern human’s waking day is 16 hours, while many mammals are only awake for half as many hours.[51] Additionally, humans are most awake during the early evening hours, while other primates’ days begin at dawn and end at sundown. Many of these behavioral changes can be attributed to the control of fire and its impact on daylight extension.[51]

The cooking hypothesis[edit]

The cooking hypothesis proposes the idea that the ability to cook allowed for the brain size of hominids to increase over time. This idea was first presented by Friedrich Engels in the article «The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man» and later recapitulated in the book Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human by Richard Wrangham and then in a book by Suzana Herculano-Houzel.[53] Critics of the hypothesis argue that cooking with controlled fire was insufficient to start the increasing brain size trend.

The cooking hypothesis gains support by comparing the nutrients in raw food to the much more easily digested nutrients in cooked food, as in an examination of protein ingestion from raw vs. cooked egg.[54] Scientists have found that among several primates, the restriction of feeding to raw foods during daylight hours limits the metabolic energy available.[55] Genus Homo was able to break through the limit by cooking food to shorten their feeding times and be able to absorb more nutrients to accommodate the increasing need for energy.[56] In addition, scientists argue that the Homo species was also able to obtain nutrients like docosahexaenoic acid from algae that were especially beneficial and critical for brain evolution, and the detoxification of food by the cooking process enabled early humans to access these resources.[57]

Besides the brain, other human organs also demand a high metabolism.[56] During human evolution, the body-mass proportion of different organs changed to allow brain expansion.

Changes to diet[edit]

Before the advent of fire, the hominid diet was limited to mostly plant parts composed of simple sugars and carbohydrates such as seeds, flowers, and fleshy fruits. Parts of the plant such as stems, mature leaves, enlarged roots, and tubers would have been inaccessible as a food source due to the indigestibility of raw cellulose and starch. Cooking, however, made starchy and fibrous foods edible and greatly increased the diversity of other foods available to early humans. Toxin-containing foods including seeds and similar carbohydrate sources, such as cyanogenic glycosides found in linseed and cassava, were incorporated into their diets as cooking rendered them nontoxic.[58]

Cooking could also kill parasites, reduce the amount of energy required for chewing and digestion, and release more nutrients from plants and meat. Due to the difficulty of chewing raw meat and digesting tough proteins (e.g. collagen) and carbohydrates, the development of cooking served as an effective mechanism to efficiently process meat and allow for its consumption in larger quantities. With its high caloric density and content of important nutrients, meat thus became a staple in the diet of early humans.[59] By increasing digestibility, cooking allowed hominids to maximize the energy gained from consuming foods. Studies show that caloric intake from cooking starches improves 12-35% and 45-78% for protein. As a result of the increases in net energy gain from food consumption, survival and reproductive rates in hominids increased.[60] Through lowering food toxicity and increasing nutritive yield, cooking allowed for an earlier weaning age, permitting females to have more children.[61] In this way, too, it facilitated population growth.

It has been proposed that the use of fire for cooking caused environmental toxins to accumulate in the placenta, which led to a species-wide taboo on human placentophagy around the time of the mastery of fire. Placentophagy is common in other primates.[62]

Biological changes[edit]

Before their use of fire, the hominid species had large premolars, which were used to chew harder foods, such as large seeds. In addition, due to the shape of the molar cusps, the diet is inferred to have been more leaf- or fruit-based. Probably in response to consuming cooked foods, the molar teeth of H. erectus gradually shrank, suggesting that their diet had changed from tougher foods such as crisp root vegetables to softer cooked foods such as meat.[63][64] Cooked foods further selected for the differentiation of their teeth and eventually led to a decreased jaw volume with a variety of smaller teeth in hominids. Today, a smaller jaw volume and teeth size of humans is seen in comparison to other primates.[65]

Due to the increased digestibility of many cooked foods, less digestion was needed to procure the necessary nutrients. As a result, the gastrointestinal tract and organs in the digestive system decreased in size. This is in contrast to other primates, where a larger digestive tract is needed for fermentation of long carbohydrate chains. Thus, humans evolved from the large colons and tracts that are seen in other primates to smaller ones.[66]

According to Wrangham, control of fire allowed hominids to sleep on the ground and in caves instead of trees and led to more time being spent on the ground. This may have contributed to the evolution of bipedalism, as such an ability became increasingly necessary for human activity.[67]

Criticism[edit]

Critics of the hypothesis argue that while a linear increase in brain volume of the genus Homo is seen over time, adding fire control and cooking does not add anything meaningful to the data. Species such as H. ergaster existed with large brain volumes during time periods with little to no evidence of fire for cooking. Little variation exists in the brain sizes of H. erectus dated from periods of weak and strong evidence for cooking.[51] An experiment involving mice fed raw versus cooked meat found that cooking meat did not increase the amount of calories taken up by mice, leading to the study’s conclusion that the energetic gain is the same, if not greater, in raw meat diets than cooked meats.[68] Studies such as this and others have led to criticisms of the hypothesis that state that the increases in human brain-size occurred well before the advent of cooking due to a shift away from the consumption of nuts and berries to the consumption of meat.[69][70] Other anthropologists argue that the evidence suggests that cooking fires began in earnest only 250,000 BP, when ancient hearths, earth ovens, burned animal bones, and flint appear across Europe and the Middle East.[71]

See also[edit]

- Hunting hypothesis

- Savannah hypothesis

- Raw foodism

- Theft of fire

References[edit]