Как космические технологии изменили жизнь

Сейчас мы живем, словно в космосе. Нас окружает много вещей, которые были разработаны для исследователей Вселенной. Например, стекла для очков. Сейчас они сверхпрочные. Сначала такое покрытие было только у козырьков скафандров астронавтов. Теперь оно используется практически в каждых очках.

Как еще космические технологии изменили нашу жизнь? Прежде всего, осмотрим свою кухню. Тефлоновые сковородки — подарок хозяйкам от разработчиков. Первое предназначение этого покрытия — теплоизоляция космических кораблей, а уже потом он оказался на вооружении кулинаров. Как, собственно, и застежки-молнии, и «липучки», которыми сначала снабжали костюмы космонавтов.

Заоблачные технологии на Земле защищают нас и от огня. Во-первых, ткань, из которой делают костюмы пожарных, изначально была разработана для скафандров по программе «Аполлон». А для того, чтобы защитить капсулу корабля, которая может расплавиться при входе в атмосферу, изобрели огнестойкую краску. Теперь ей покрывают стальные конструкции в многоэтажках.

Космические изобретения сейчас спасают жизни людей не только в чрезвычайных ситуациях. Медики уже давно взяли их на вооружение. Лечебные костюмы «Адели», «Пингвин» и «Регент» помогают при реабилитации больных с нарушениями центральной нервной системы. Искусственное сердце тоже появилось в лаборатории астроконструкторов. Оно сделано по принципу насосов, обеспечивающих космические корабли бесперебойной поставкой топлива.

Самый точный диагностический прибор — магнитно-резонансный томограф — тоже появился благодаря исследователям космоса. Технологию использовали сначала для изучения небесных тел. А лапароскопия, как и сам робот-хирург Да Винчи, стали прорывом в медицине. Ученые изобрели его для того, чтобы с Земли проводить хирургические операции космонавтам во время полета.

В любой аптеке вы можете купить десятки препаратов, которые помогают побороть головокружение, укачивание, инфекции дыхательных путей.

Ну и конечно, спутниковая связь, навигация и телевидение. Все это было изобретено для работы в космосе, а теперь делает удобной жизнь на Земле. Технологии развиваются настолько быстро, что возможно, очень скоро мы все-таки будем летать на другие планеты в гости, сообщается в эфире телеканала «Кубань 24».

Авторы: Нина Радченко

11:42 / 5 апреля 2021

Воздействия первого полёта человека в космос на развитие России и человечества

В связи с 60-летием полёта Ю. А. Гагарина сделан краткий междисциплинарный анализ основных аспектов комплекса воздействий первого полёта человека в космос на развитие России и человечества. Представлены научный, технологический, организационно-управленческий, социально-политический, социокультурный, экологический, футурологический аспекты. Сформулированы основные выводы.

Сергей Владимирович Кричевский, доктор философских наук, профессор, главный научный сотрудник института истории естествознания и техники имени С. И. Вавилова РАН, Москва, Россия, svkrich@mail.ru

Лидия Васильевна Иванова

, кандидат социологических наук, научный сотрудник НИИ «Центр подготовки космонавтов имени Ю. А. Гагарина», Звездный городок, Московская область, Россия, l.v.ivanova@gctc.ru

English

TOPIC OF THE ISSUE: THE 60TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE FIRST HUMAN SPACE FLIGHT

THE INFLUENCE OF THE FIRST HUMAN SPACE FLIGHT ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF RUSSIA AND THE HUMANITY

Sergey V. KRICHEVSKY, Doctor of Philosophy, Professor, Chief Researcher, S. I. Vavilov Institute for the History of Science and Technology of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IHST RAS), ex-test-cosmonaut, Moscow, Russia, svkrich@mail.ru

Lidiya V. IVANOVA, Candidate of Social Sciences, Researcher, Gagarin Research & Test Cosmonaut Training Center, Star City, Moscow region, Russia, l.v.ivanova@gctc.ru

ABSTRACT. In connection with the 60th anniversary of Yuri Gagarin’s space flight, a brief interdisciplinary analysis concerning the influence of the first human space flight on the development of Russia and the humanity is made. Scientific, technological, organizational and managerial, sociopolitical, socio-cultural, environmental, and futurological aspects are presented. The main conclusions are drawn.

Keywords: influence, Gagarin, Earth, space, first flight, development, Russia, technology, man, humanity

Введение

В связи с 60-летием полёта Ю. А. Гагарина в космос сделаем краткий междисциплинарный анализ его воздействий на Россию и человечество в контексте истории, настоящего и будущего.

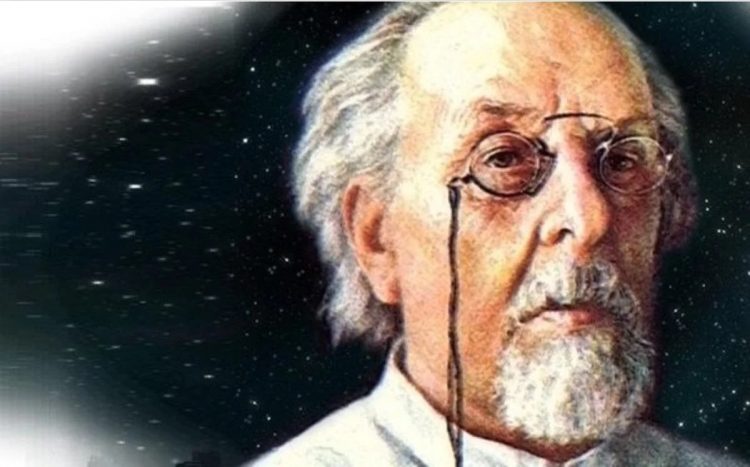

К. Э. Циолковский за 40 лет до первого полёта дал прогноз: описание полётов людей в космос (1920), а за 25 лет – облика и качеств первого космонавта (1935) [ 1, 2 ], во многом совпавшие с реалиями.

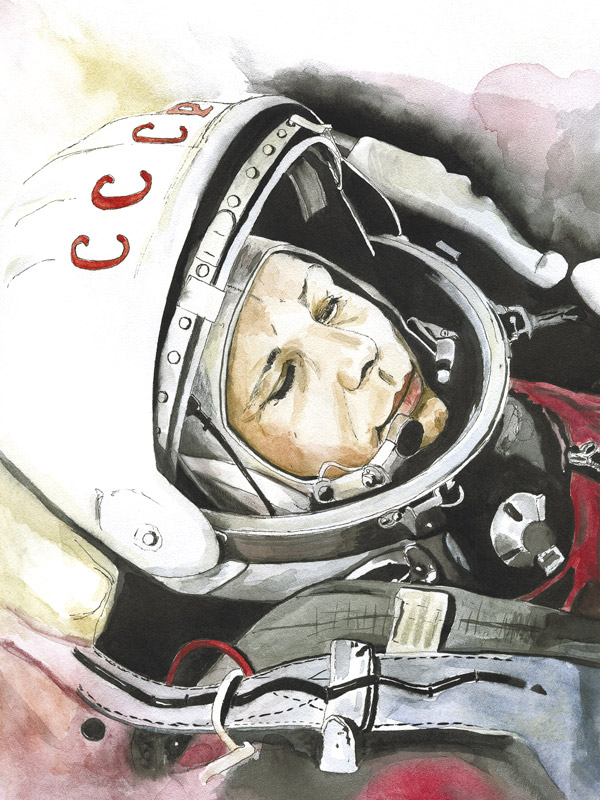

Юрий Гагарин в корабле «Восток-1»

После первого полёта человека в космос вышли статьи с анализом его результатов и перспектив исследования и освоения космоса. Одной из первых была статья профессора В. В. Добронравова (1962): «Ю. А. Гагарин побывал там, где никогда ещё не был ни один человек Земли… Проникновение человека в космос неизмеримо раздвигает границы нашего познания, обогащает науку и культуру. Полёт Ю. А. Гагарина показал, что путь человеку в межпланетное пространство, к Луне, другим планетам в принципе открыт и требуется только время для дальнейшей отработки теоретических и практических вопросов. …Трудно пока представить, как будет происходить дальнейшее освоение космоса. …Но ясно одно: человечество не может остановиться в начале пути к покорению космоса» [ 3 ].

В широком смысле следует и будем рассматривать не только сам полёт длительностью 108 минут от старта до приземления первого космонавта, но весь процесс его подготовки и выполнения, начиная с первых решений по его организации в 1959–1960 годах и включая ряд послеполётных технических и других действий и мероприятий после 12 апреля 1961 года (см.: [ 4-14 ]).

Пришло время подвести итоги 60-летия и дать новый импульс космической экспансии, решению проблемы исследования и освоения космоса человеком в науке, образовании и практике. Рассмотрим важные моменты основных аспектов воздействий первого полёта человека в космос на развитие людей, нашей страны и мирового сообщества.

Старт космического корабля «Восток» с пилотом-космонавтом Юрием Гагариным на борту

1. Научный и технологический аспекты

Первый полёт человека в космос является эталоном постановки и решения принципиально новой, сложнейшей научно-технической задачи в условиях чрезвычайно высоких уровней неопределённости и риска при жёстком дефиците времени и острой конкуренции за мировое лидерство.

В нашей стране были созданы основы ряда новых направлений в науке и технике. Исследованы возможности, особенности, ограничения техники и организма человека, получены новые знания для подготовки и выполнения полётов в околоземном космическом пространстве с применением новой ракетно-космической техники. Разработаны, созданы, испытаны космические технологии и техника для пилотируемых полётов. Отработаны и апробированы методики отбора и подготовки космонавтов, их профессиональной деятельности в космических полётах, обеспечения безопасности и выживания в штатных и нештатных ситуациях.

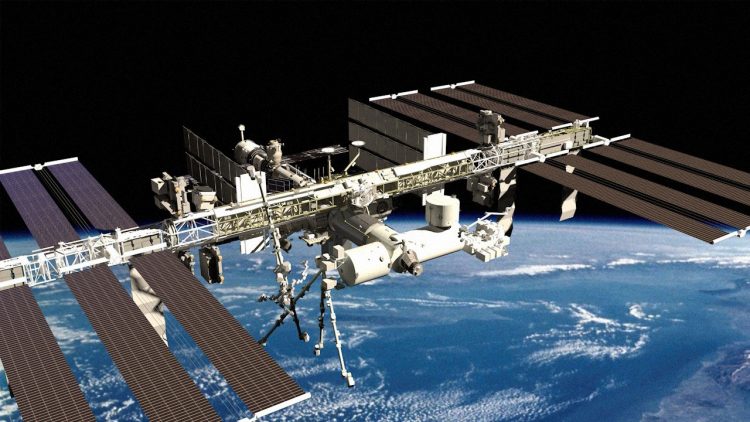

В результате успешного полёта Гагарина доказано, что человек может летать в космос, жить вне Земли в условиях воздействия невесомости, других факторов космических полётов и безопасно возвращаться на Землю. Полёт Гагарина дал новый импульс освоению космоса в мире и научно-технической космической гонке между СССР и США в 60-80-х годах XX века. Важным этапом был первый выход человека в открытый космос (А. А. Леонов, СССР, 18.03.1965), кульминацией стала высадка первого человека на Луну (Н. Армстронг, США, 20.07.1969), затем последовало создание долговременных орбитальных станций. В XXI веке люди постоянно находятся на орбите вокруг Земли на борту Международной космической станции [ 4-16 ].

Первый полёт человека в космос – это маяк и пример для развития национальной космической науки, образования, мотив и импульс для участия новых стран в пилотируемых полётах, создания национальных пилотируемых программ, космической техники и технологий (в КНР, ЕС, Индии и др.).

Фото первого отряда космонавтов СССР – первых 11, слетавших в космос

2. Организационный и управленческий аспекты

Первый полёт человека стал основой пилотируемой космонавтики, в значительной мере повлиял на развитие всей космической отрасли, задал высокие требования и стандарты качества, надёжности и безопасности космической техники и деятельности. В СССР по инициативе учёных, инженеров, конструкторов под руководством органов власти, с участием Академии наук, Министерства обороны, организаций промышленности, образования и других были созданы новые структуры и коллективы людей, в том числе системы управления, производства, испытаний, приобретён уникальный опыт организации пилотируемого космического полёта и управления на полном жизненном цикле.

Выдающуюся роль в организации и выполнении первого полёта человека в космос сыграл С. П. Королёв. В 1960 году созданы Центр подготовки космонавтов и первый отряд космонавтов (20 человек). Многие специалисты, участвовавшие в подготовке и выполнении первого полёта, реализовали свой потенциал в космонавтике, других сферах управления и практики, накопили, формализовали, передали богатый опыт, оставили профессиональное наследие (документальное, кадровое, творческое).

В России, США, ЕС, КНР и других странах регулярно проходят конкурсы по отбору космонавтов, за 60 лет в них участвовало более 100 тысяч человек. Создано и развивается сообщество космонавтов: профессиональные отряды космонавтов, астронавтов, международная Ассоциация участников космических полётов, объединяющая четыре национальные ассоциации. Полёт Гагарина стал и остаётся главным примером и призывом для профессиональных космонавтов и новых кандидатов, мечтающих о полётах в космос и о работе в космической отрасли [ 5-17 ].

«Все в космос!» − лозунг-призыв на стихийном митинге, состоявшемся после полёта Ю. А. Гагарина (Москва, Красная площадь, 12 апреля 1961 года)

3. Социально-политический аспект

«Все в космос!» − таким был лозунг-призыв на стихийном митинге, состоявшемся после полёта Ю. А. Гагарина в Москве на Красной площади 12 апреля 1961 года. Он отразил не только эйфорию праздника, настроение и мечты людей в связи с выдающимся достижением и событием для СССР и всего человечества, но и начало, и сущность процесса космической экспансии (по: [ 14 ] ).

Международный и общемировой резонанс первого полёта: человечество впервые ощутило себя единым в мечте, стремлении и возможности человека и нашей цивилизации освоить космос с применением новых технологий и техники.

Первый полёт установил критерий лидерства и «полноценности» космических государств, корпораций: полёты людей в космос. С него началась и продолжается регистрация мировых рекордов людей в космосе.

В общественном мнении в России и мире выполнение полёта в космос является высшим профессиональным и личным достижением человека.

В честь пятидесятой годовщины полёта человека в космос 7 апреля 2011 года резолюцией A/RES/65/271 Генеральная ассамблея ООН провозгласила 12 апреля Международным днём полёта человека в космос [ 18 ].

12 апреля – Международный день полёта человека в космос (Резолюция Генеральной ассамблеи ООН, 2011 г.)

Полёт в космос Ю. А. Гагарина считается в общественном сознании России и политике государства одной из главных скреп, высшим достижением страны, науки и техники, символом нашего абсолютного приоритета и лидерства в освоении космоса.

Новая и парадоксальная реальность XXI века: в России в целом, и даже в космической отрасли, немало противников развития пилотируемой космонавтики, затраты на которую составляют почти половину космического бюджета. По убеждениям множества людей, эффекта от неё якобы нет, а в стране существует большое количество реальных и приоритетных земных социальных и других проблем, на решение которых не хватает средств. Например, в 2011 году появились крайне критические и по сути антикосмические призывы: «50 лет человек в космосе. Не пора ли обратно?» [ 19 ].

Но как оценить полную социально-политическую цену и вклад полётов людей в космос, в том числе в категориях общественного блага, человеческого капитала и потенциала, в историю развития страны, в её настоящее и будущее? Как оценить общий эффект от полёта Гагарина для страны и человечества? Как оценить научно-технологические, социально-политические, экономические, социокультурные и другие потери и последствия, если Россия откажется от полётов своих граждан в космос? По сути это запрет на космическую мечту, отказ от лидерства в космосе и экспансии.

Памятник Ю. А. Гагарину в Москве на площади Гагарина

Именно первый полёт и образ Гагарина поддерживают в постсоветский период пилотируемую космонавтику в России, не дают остановить её и разрушить. История, гордость за неё и стойкость – это необходимое, но недостаточное условие для достойного космического будущего России и человечества: в пилотируемых полётах мы не имеем права делать ни шага назад и должны идти вперёд. Необходимы новые цели, проекты, технологии, достижения.

Новыми лидерами процесса освоения космоса человеком с 2016 года в мире стали предприниматели, общественные деятели, новые корпорации и космические сообщества, которые конкурируют со «старыми» космическими сообществами, государствами и корпорациями. Среди них выделяются И. Маск, корпорация SpaceX (США) и И. Р. Ашурбейли, космическое сообщество – первое цифровое космическое государство Asgardia (в нём участвует около 1 млн человек из ~200 стран), для которых полёт Ю. А. Гагарина явился и остаётся примером и импульсом для деятельности и развития [ 20, 21 ].

4. Социокультурный аспект

Полёт Гагарина, образ нашего героического соотечественника – первого космонавта Земли – важнейший социокультурный феномен XX века, одно из ярчайших событий всей отечественной и мировой истории, высших достижений человека, науки и техники.

Образ Ю. А. Гагарина – одна из основ космической субкультуры, он постоянно отражается и воспроизводится в общественной и культурной жизни нашей страны и мира, во всём информационном пространстве, в СМИ и современных электронных сетях.

Первый полёт человека в космос в индивидуальном и общественном сознании остаётся подвигом и абсолютным рекордом человека, нашей страны и человечества. Его логичное продолжение: первый выход человека в открытый космос, первый шаг на Луне, предстоящий первый шаг на Марсе.

«Экологическая» записка Ю. А. Гагарина, написанная после полёта (копия автографа), и вид Земли из космоса

Воздействия первого полёта человека в космос в значительной мере осуществляются через образ личности Гагарина и проявляются во многих сферах и направлениях. Прежде всего в науке, образовании, литературе и искусстве, в том числе в масштабных социокультурных проектах: в создании памятников, музеев, выставок, кинофильмов, музыкальных и других произведений; в работе планетариев, космоцентров; в проведении космических форумов, конференций, чтений, космических уроков, спортивных состязаний и т. д. Невозможно представить культуру без космической филателии, нумизматики, эмблематики, фалеристики и др. (см.: [ 6-12, 14 ]).

Подвиг Гагарина имеет особое значение для социализации, обучения и воспитания молодежи, определения цели жизни как пример стремления к освоению новых знаний и технологий, самореализации и достижения успеха в сложной профессии, активной деятельности в интересах страны и всего человечества. Воздействия первого полёта человека проявляются в процессе создания, институционализации и деятельности новых космических сообществ в России и мире (см.: [ 14, 21 ]).

5. Экологический аспект

Своим первым космическим полётом и взглядом в космос и из космоса на Землю Ю. А. Гагарин открыл, ощутил и дал нам новое «очеловеченное» измерение и понимание Земли и космоса, окружающей среды как единого пространства «Земля + космос», новую картину мира, нашего желаемого и возможного будущего с приоритетом сохранения, сбережения людьми родной планеты. После полёта он написал об этом в короткой и эмоциональной «экологической» записке: «Облетев Землю на корабле-спутнике, я увидел, как прекрасна наша планета. Люди, будем хранить и приумножать эту красоту, а не разрушать её!» [ 4 ].

Образ будущего (визуализация космической инфраструктуры)

Вслед за Гагариным более 560 человек в мире побывали в космосе, и каждый ощутил красоту и хрупкость Земли в огромной Вселенной. От космонавтов, а также из других источников многие земляне узнали об окружающей среде и природных ресурсах Земли и космоса, о нарастании экологических проблем и загрязнений. Это имеет большое значение для формирования экологического сознания людей и экологизации всей деятельности человечества.

6. Футурологический аспект

Полёт Гагарина символизирует вектор развития человека и человечества, наше земное и космическое будущее: сохранение Земли и движение в космос с сохранением ведущей роли, статуса и свойств человека.

В мире в 10-20-е годы XXI века началась и поднимается новая волна освоения космоса человеком и человечеством с применением новых технологий и техники, включая роботов как помощников и др. Идёт процесс индустриализации космической деятельности в целях решения проблем на Земле, добычи и использования внеземных ресурсов, освоения Луны и Марса. На повестке дня возвращение человека на Луну, постоянная база и начало колонизации Луны как «седьмого континента Земли». В перспективе – искусственная гравитация и защита от радиации для людей в космосе; пилотируемая экспедиция на Марс и его колонизация; создание условий для репродукции – рождения и постоянной жизни людей вне Земли; создание космического человека и человечества, многопланетной человеческой цивилизации. Всё это требует качественно нового продолжения процесса освоения космоса человеком: выхода за ограничения и достигнутые пределы полётов и жизни людей в космосе, учёта и парирования новых рисков, организации международного сотрудничества в новой парадигме «единого человечества» (см.: [ 15-17, 20, 21 ]).

Основные выводы

1. Первый полёт человека в космос оказал мощное воздействие на СССР / Россию, всё мировое сообщество, продолжает влиять на общественное сознание, развитие науки и техники, космической и других сфер деятельности как важный пример возможностей человека, общества, государства, человечества для дальнейшей эволюции и космической экспансии.

2. Главным актором процесса освоения космоса был, является и будет человек, стремящийся за пределы Земли. Опыт, достижения, потенциал, ограничения и перспективы человека в космических полётах, организации безопасной и достойной постоянной жизни вне Земли должны быть приоритетом новых исследований, технологий, образования и практики.

3. Необходимо переосмысление истории, опыта и результатов освоения космоса человеком для коррекции целей, разработки новой стратегии, программ, проектов и технологий космической деятельности в балансе с решением проблем на Земле в интересах России и человечества на новом этапе космической эры.

Литература

- Циолковский К. Э. Вне Земли. Повесть. Калуга: Изд-во Калужского общества изучения природы и местного края, 1920. 118 с.

- Бурцева Н. Л. Нострадамус космоса: к 160-летию Константина Циолковского // Воздушно-космическая сфера. 2017. № 3. С. 8-15.

- Добронравов В. В., Что дал первый полёт науке о Вселенной // Авиация и космонавтика. 1962. № 4. С. 10-19. URL: https://epizodsspace.airbase.ru/bibl/a-i-k/1962/chto-dal.html (Дата обращения: 14.01.2021).

- «Облетев Землю, я увидел, как прекрасна наша планета!» [Электронный ресурс] // Газета.Ru. 2016. 16 апреля. URL:. https://www.gazeta.ru/science/photo/obletev_zemlyu_ya_uvidel_kak_prekrasna_nasha_planeta.shtml (Дата обращения: 14.01.2021).

- Советская космическая инициатива в государственных документах. 1946–1964 гг. / Под ред. Ю. М. Батурина. М.: РТСофт, 2008. 16 с.

- Мировая пилотируемая космонавтика. История. Техника. Люди / Под ред. Ю. М. Батурина. М.: РТСофт, 2005. 752 с.

- Каманин Н. П. Скрытый космос: в 4 кн. М.: Инфортекст-ИФ, ООО ИИД Новости космонавтики, 1995, 1997, 1999, 2001. 1 кн. – 400 с.; 2 кн. – 448 с.; 3 кн. – 352 с.; 4 кн. – 384 с.

- Госкорпорация Роскосмос (Россия) [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.roscosmos.ru/ (Дата обращения: 14.01.2021).

- Ракетно-космическая корпорация «Энергия» имени С. П. Королёва (Россия) [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.energia.ru/ (Дата обращения: 14.01.2021).

- ФГБУ «НИИ ЦПК им. Ю. А. Гагарина» (Россия) [Электронный ресурс]. URL: http://www.gctc.ru/ (Дата обращения: 14.01.2021).

- Космическая энциклопедия ASTROnote [Электронный ресурс]. URL: http://astronaut.ru/index.htm (Дата обращения: 14.01.2021).

- Объединённый мемориальный музей Ю. А. Гагарина [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://gagarinm.ru/ (Дата обращения: 14.01.2021).

- Леонов А. А. Время первых. Судьба моя – я сам. М: АСТ, 2019. 352 с.

- Иванова Л. В., Кричевский С. В. Сообщество космонавтов. История становления и развития за полвека. Проблемы. Перспективы / предисл. В. П. Савиных. М.: ЛИБРОКОМ, 2013. 200 с.

- NASA (США) [Электронный ресурс]. URL: http://www.nasa.gov/ (Дата обращения: 14.01.2021).

- Пора присоединить Луну к Земле. Выступление академика РАН Б. Е. Чертока на XXIV Планетарном конгрессе участников космических полётов 5 сентября 2011 года [Электронный ресурс]. // Новая газета. 2011. 23 сентября. URL: https://novayagazeta.ru/articles/2011/09/23/46013-pora-prisoedinit-lunu-k-zemle (Дата обращения: 14.01.2021).

- Кричевский С. В. «Космический» человек: идеи, технологии, проекты, опыт, перспективы // Воздушно-космическая сфера. 2020. № 1. С. 26- 35. DOI: 10.30981/2587- 7992-2020-102-1-26-35

- ООН. Международный день полёта человека в космос – 12 апреля [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.un.org/ru/observances/human-spaceflight-day (Дата обращения: 28.01.2021).

- Сурдин В. Г. 50 лет человек в космосе. Не пора ли обратно? [Электронный ресурс] // Полит.ру. 2012. 13 апреля. URL: https://polit.ru/article/2012/04/13/space_surdin/ (Дата обращения: 09.01.2021).

- SpaceX (США) [Электронный ресурс]. URL: http://www.spacex.com (Дата обращения: 14.01.2021).

- Сайт Asgardia – The Space Nation [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://asgardia.space/ (Дата обращения: 14.01.2021).

References

- Tsiolkovskiy K.E. Vne Zemli. Povest’. Kaluga, Izdatel’stvo Kaluzhskogo obshchestva izucheniya prirody i mestnogo kraya, 1920. 118 p.

- Burtseva N.L. Nostradamus kosmosa: k 160-letiyu Konstantina Tsiolkovskogo. Vozdushno-kosmicheskaya sfera, 2017, no. 3, pp. 8-15.

- Dobronravov V.V. Chto dal pervyy polet nauke o Vselennoy. Aviatsiya i kosmonavtika., 1962, no. 4, pp. 10-19. Available at: https://epizodsspace.airbase.ru/bibl/a-i-k/1962/chto-dal.html (Retrieval date: 14.01.2021).

- «Obletev Zemlyu, ya uvidel, kak prekrasna nasha planeta!» Gazeta.ru. 2016. April 16. Available at: https://www.gazeta.ru/science/photo/obletev_zemlyu_ya_uvidel_kak_prekrasna_nasha_planeta.shtml (Retrieval date: 14.01.2021).

- Sovetskaya kosmicheskaya initsiativa v gosudarstvennykh dokumentakh. 1946-1964 gg. Ed. Yu. M. Baturin. Moscow, RTSoft, 2008. 16 p.

- Mirovaya pilotiruemaya kosmonavtika. Istoriya. Tekhnika. Lyudi. Ed. Yu. M. Baturin. Moscow, RTSoft, 2005. 752 p.

- Kamanin N.P. Skrytyy kosmos. Moscow, Infortekst-IF, OOO IID Novosti kosmonavtiki, vol. 1., 1995, 400 p., vol. 2, 1997, 448 p., vol. 3, 1999, 352 p., vol. 4, 2001, 384 p.

- Goskorporatsiya Roskosmos (Russia). Available at: https://www.roscosmos.ru/ (Retrieval date: 14.01.2021).

- Raketno-kosmicheskaya korporatsiya «Energiya» imeni S. P. Koroleva (Russia). Available at: https://www.energia.ru/ (Retrieval date: 14.01.2021).

- FGBU «NII TsPK im. Yu. A. Gagarina» (Russia). Available at: http://www.gctc.ru/ (Retrieval date: 14.01.2021).

- Kosmicheskaya entsiklopediya ASTROnote. Available at: http://astronaut.ru/index.htm (Retrieval date: 14.01.2021).

- Ob»edinennyy memorial’nyy muzey Yu. A. Gagarina. Available at: https://gagarinm.ru/ (Retrieval date: 14.01.2021).

- Leonov A.A. Vremya pervykh. Sud’ba moya – ya sam. Moscow, AST, 2019. 352 p.

- Ivanova L.V., Krichevskiy S.V. Soobshchestvo kosmonavtov. Istoriya stanovleniya i razvitiya za polveka. Problemy. Perspektivy. Moscow, LIBROKOM, 2013. 200 p.

- NASA (USA). Available at: http://www.nasa.gov/ (Retrieval date: 14.01.2021).

- Pora prisoedinit’ Lunu k Zemle. Vystuplenie akademika RAN B. E. Chertoka na XXIV Planetarnom kongresse uchastnikov kosmicheskikh poletov 5 sentyabrya 2011 goda // Novaya gazeta. 2011. September 23. Available at: https://novayagazeta.ru/articles/2011/09/23/46013-pora-prisoedinit-lunu-k-zemle (Retrieval date: 14.01.2021).

- Krichevskiy S.V. «Kosmicheskiy» chelovek: idei, tekhnologii, proekty, opyt, perspektivy. Vozdushno-kosmicheskaya sfera, 2020, no. 1, pp. 26-35. DOI: 10.30981/2587- 7992-2020-102-1-26-35

- OON. Mezhdunarodnyy den’ poleta cheloveka v kosmos – 12 aprelya. Available at: https://www.un.org/ru/observances/human-spaceflight-day (Retrieval date: 28.01.2021).

- Surdin V.G. 50 let chelovek v kosmose. Ne pora li obratno? Polit.ru. 2012. April 13. Available at: https://polit.ru/article/2012/04/13/space_surdin/ (Retrieval date: 09.01.2021).

- SpaceX (USA). Available at: http://www.spacex.com (Retrieval date: 14.01.2021).

- Asgardia – The Space Nation. Available at: https://asgardia.space/ (Retrieval date: 14.01.2021).

© Кричевский С. В., Иванова Л. В., 2021

История статьи:

Поступила в редакцию: 07.02.2021

Принята к публикации: 04.03.2021

Модератор: Плетнер К. В.

Конфликт интересов: отсутствует

Для цитирования: Кричевский С. В., Иванова Л. В. Воздействия первого полета человека в космос на развитие России и человечества // Воздушно-космическая сфера. 2021. № 1. С. 6-17.

Скачать статью в формате PDF >>

-

-

April 12 2016, 12:19

- Космос

- Cancel

Что дало человечеству освоение космоса

В середине прошлого столетия человечество шагнуло в эру освоения космоса. Был совершен огромнеший прорыв – первые полеты в космос, длительные и пилотируемые; первый выход в космическое пространство! Затрачено неимоверное множество усилий и средств тысяч людей. Ну а что дало человечеству покорение космоса?

Стоит признать, в современном мире космонавтика рассматривается как обыденное явление. Мы уже не удивляемся тому, что большее количество процессов не обходится без участия спутников. Это и мобильная связь, и телевизионный сигнал, и прогнозирование погоды, и спутниковые фотографии. Спутниковой системой определения местоположения (GPS-навигация, спутниковая система навигации) успешно пользуются моряки, пилоты, автомобилисты, шахтеры, туристы. Около 1000 людей посетили просторы Вселенной к началу 21-ого века. На астероидах и кометах перебывали космические аппараты. Автоматический зонд под названием Вояжер1, преодолев миллиарды километров, достиг края Солнечной системы. Первый турист космоса Деннис Тито побывал на орбите.

С возникновением адаптированного и ориентированного на простого обывателя пути в космос, более эффективного, чем нынешние космические корабли, осуществится мечта использовать вселенную в привычной для нас форме. Станет возможным путешествие и отдых на орбите нашей планеты или другой. Сейчас это звучит фантастически, согласитесь? Как для Средневекового жителя казалось бы сказкой любое устройство из нашей бытовой техники, которую мы используем ежедневно.

А еще, сегодняшние ученые ставят в планы запустить проект по строительству лифта в космос. Это возможно воплотить в реальность с технологиями, которыми располагает человечество уже сейчас. Не секрет, что в определенных кругах продумывают альтернативу извлечения ресурсов с Луны и астероидов, ведь там существуют полезные ископаемые, которые отсутствуют в недрах нашей планеты, например, вещество гелий3. Его используют для топлива в термоядерной энергетике. Предположительно, что для обеспечения всей Земли энергией достаточно 100 тонн гелия3 в год.

Согласитесь, но даже перечисленное выше наглядно показывает, насколько необходимо было проникновение в космос и то, как оправдали и продолжают оправдывать себя затраченные на то ресурсы.

А посему, предлагаю вспомнить всех тех, кто работал и продолжает работать в этом направлении, ибо вклад их в нашу с Вами жизнь огромен!

С Праздником, друзья!

В этом году исполнилось 60 лет со дня полета Юрия Гагарина в космос. С гостями подкаста «Что изменилось?» обсуждаем, куда продвинулась космонавтика и правдоподобно ли показывают космос в кино и сериалах

Гости выпуска:

Иван Моисеев, руководитель Института космической политики. Иван объяснил, что мешает России стать лидером в области космонавтики и как искажается время в космосе.

Научный журналист Михаил Котов рассказал, как действуют гипотетические кротовые норы и как ученые обнаруживают объекты из других галактик.

Ведущий подкаста — Макс Ефимцев — адепт современных технологий, инфлюенсер, SMM-специалист.

Таймлайн беседы:

01:16 — Откуда в космосе 20 тыс. неработающих спутников

05:19 — Почему космические открытия попадают в СМИ с опозданием

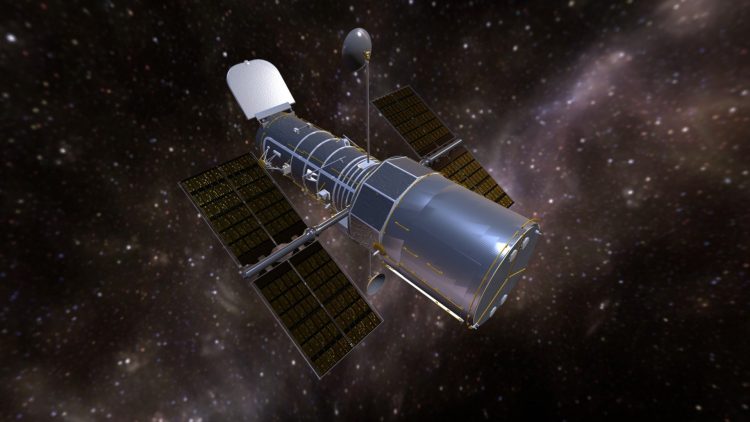

09:50 — Куда можно заглянуть с помощью телескопа

15:13 — Почему Perseverance вернется с Марса только через 15 лет

22:58 — Нужна ли нам колония на Марсе

25:51 — Что мешает России стать лидером космического направления

29:35 — В чем феномен Илона Маска

37:37 — Изучают ли сейчас Луну

39:15 — Можно ли телепортироваться через кротовые норы

43:09 — Гости советуют, что почитать и посмотреть о космосе

46:38 — Как в космосе искажается время

53:40 — Как космические открытия попадают в нашу повседневность

Самые важные космические открытия за последние годы

Иван: Громкие события, которые произошли недавно — это высадка Perseverance на Марс, сбор грунта с поверхности Луны и с астероида Рюгу. Но об открытиях пока говорить рано — ученые будут изучать привезенные образцы годами. К тому же, зачастую открытия остаются в научных журналах и статьях и попадают в СМИ спустя время.

Михаил: Среди важных событий в астрономии можно выделить российско-немецкий проект Спектр-РГ. Это обсерватория, оснащенная двумя рентгеновскими телескопами, которые составляют карту всей Вселенной. Телескопы уже прошли все небо дважды, всего будет 4 таких прохода. В конце проекта ученые будут лучше понимать космологию всего, что нас окружает.

Два года назад впервые был обнаружен межзвездный объект в Солнечной системе. Это астероид, который пролетает сквозь всю систему и отправляется дальше. Ученые пока не могут сказать, откуда он появился и сколько летел. Спустя год ученый в Крымской обсерватории обнаружил комету Борисова — второй межзвездный объект, который находится в Солнечной системе. Сейчас астрономы спорят, насколько часто такие объекты попадают в Солнечную систему и что делать, если они будут лететь в сторону Земли. Иван добавляет, что существует проект Лира, который направлен на то, чтобы успеть перехватить эти объекты.

Какие бывают телескопы и как далеко можно заглянуть с их помощью

Иван: Телескопы различаются по длине волны, которую изучают. Существуют оптические телескопы, рентгеновские, изучающие гамма-диапазон, инфракрасные диапазоны. То, как далеко можно заглянуть, зависит от того, на что смотреть. Самая большая звезда находится на расстоянии в 9 млрд световых лет — для сравнения, вся вселенная имеет размер 13,4 млрд световых лет. На краю наблюдаемой вселенной находится самая крупная галактика — достаточно яркий объект там можно увидеть даже невооруженным взглядом.

Что такое черная дыра простыми словами?

Почему марсоход Perseverance вернется на Землю только через 15 лет?

Михаил: Персеверанс собирает грунт в герметичные емкости, которые он будет возить на себе. В конце своего пути он выложит образцы грунта в специальном посадочном месте, куда могут сесть следующие миссии. Чтобы доставить образцы на Землю, прилетит небольшой марсоход, который будет складывать образцы в отлетный модуль. Добираться до Земли модуль с ракетой будут около трех лет, а к 2031 году они выйдут на орбиту Земли. Там произойдет проверка герметичности колб, и только после этого космический аппарат сможет приземлиться. Иван объясняет, что это очень сложный и дорогой процесс, но техника сейчас достаточно надежна, чтобы рассчитывать на успех.

Почему многие страны стремятся отправить космические миссии на Марс?

Иван: Наша главная задача — понять, как появилась Солнечная система, зная, чем отличаются друг от друга планеты и как они устроены. Все планеты, кроме Марса, уже изучены аппаратами, поэтому на самом деле ничего специального с Марсом не происходит. Человеку там делать нечего — со сбором образцов хорошо справляются марсоходы. Колония на Марсе невозможна — там нет света и много радиации — это все равно что заставить человека жить в метро. В качестве ресурса Марс также неудобен из-за его тяжести, так что люди высадятся туда только ради спортивного интереса.

Проблемы космического направления в России

Иван: У нас есть необходимые материальные и технические ресурсы, которые могли бы обеспечить нам первое-второе место. Мешает этому плохая организация труда: все страны резко ускорили свое продвижение в космос, но мы регулярно его снижаем.

Михаил: Космонавтика — это производная от экономики, поэтому без финансирования мало что получится. Не могу сказать, что у нас катастрофически все плохо, хотя Илон Маск и забрал у нас все коммерческие запуски. На самом деле есть и успехи и достижения, например проект РадиоАстрон.

Что такое кротовые норы и возможна ли телепортация сквозь них?

Иван: В 1919 году ученые выяснили, что Солнце искажает пространство вокруг себя. Тогда возникла гипотеза о том, что пространство можно искривить так, чтобы путь, который занимает условно сотни световых лет, можно было уложить в один световой год. Чтобы получить такое искажение, как в кротовой норе, нужны две черные дыры, расположенные рядом — тогда математически возможно превысить скорость света. Практических доказательств этого нет.

Михаил: Если представить наше пространство как лист бумаги, то на нем нужно нарисовать две точки, а потом сложить лист так, чтобы эти две точки соприкоснулись. Теоретически это схлопывание пространства между двумя точками — это и есть кротовая нора.

Что почитать и посмотреть о космосе: советы гостей

Иван: Книги Артура Кларка приближены к реальности. Писатель работал военным инженером, а затем стал председателем Британского межпланетного общества. Среди наших авторов достойны внимания Айзек Азимов и Александр Беляев.

Михаил: «Пространство» Джеймса Кори — очень интересная книжная серия, по которой сняли сериал. В нем впервые за долгое время показали, что космические корабли долго разгоняются и долго тормозят, чтобы сохранять нужное ускорение, да и сами космические корабли там гораздо реалистичнее. Еще есть сериал «Во славу человечества» — альтернативная история, рассказывающая о том, что произошло бы с космонавтикой, если бы СССР первым высадился на Луну.

Как течет время в космосе?

Иван: Скорость света составляет 300 тыс. км/с. До ближайшей звезды — 4,3 световых года: когда мы смотрим на звезду, мы видим то, как она выглядела 4,3 года назад. В черных дырах время искажается настолько, что если вы будете падать в черную дыру, вы будете падать вечно. Также существует Парадокс близнецов — это эффект времени, связанный с теорией относительности. Если вы полетите к ближайшей звезде на большой скорости, для вас пройдет около десяти лет. На Земле в это время пройдет 20-30 лет. Этот парадокс широко обыгрывается в научной фантастике.

Как влияют космические успехи на обычных людей?

Иван: Люди, которые занимаются строительством ракет, иногда попутно изобретают что-то полезное для Земли. Это называется «эффект спин-оффа» — он очень слабый, потому что для космоса делаются уникальные сложные вещи, которые вряд ли пригодятся на Земле. А основной эффект — появляется больше знаний и развивается умение соображать.

Михаил: Самое очевидное использование космических возможностей — навигаторы, связь, спутниковое ТВ, широкополосный интернет. Мы перестали удивляться тому, как много нам дает в повседневной жизни космос, но на самом деле вся наша повседневная жизнь пропитана космонавтикой.

Следите за новыми эпизодами и подписывайтесь на нас на любой удобной платформе: Apple Podcasts, CastBox, Яндекс Музыке, Google Podcasts, Spotify и ВК Подкасты. А еще следите за нами в Telegram и Instagram «Что изменилось?» — там мы подробно обсуждаем то, что не успели проговорить в выпуске, и делимся интересными материалами по теме.

Содержание

- Зачем нужно покорять космическое пространство

- Этапы освоения космоса

- I этап – первый запуск космического аппарата

- II этап – первые живые существа на орбите

- III этап – выход человека в космос

- IV этап – первая высадка на Луну

- V этап – исследование планет Солнечной системы

- VI этап – человечество выходит за пределы Солнечной системы

- VII этап – начало международного комплексного изучение космоса

- VIII этап – начало работы МКС (Международной космической станции)

- IX-этап –интенсивное исследование и коммерциализация космоса

- 10 интересных фактов про освоение космоса

История покорения космоса — самый яркий пример торжества человеческого разума над непокорной материей в кратчайший срок. С того момента, как созданный руками человека объект впервые преодолел земное притяжение и развил достаточную скорость, чтобы выйти на орбиту Земли, прошло всего лишь чуть более пятидесяти лет — ничто по меркам истории! Большая часть населения планеты живо помнит времена, когда полёт на Луну считался чем-то из области фантастики, а мечтающих пронзить небесную высь признавали, в лучшем случае, неопасными для общества сумасшедшими.

Сегодня же космические корабли не только «бороздят просторы», успешно маневрируя в условиях минимальной гравитации, но и доставляют на земную орбиту грузы, космонавтов и космических туристов. Более того — продолжительность полёта в космос ныне может составлять сколь угодно длительное время: вахта российских космонавтов на МКС, к примеру, длится по 6-7 месяцев.

А ещё за прошедшие полвека человек успел походить по Луне и сфотографировать её тёмную сторону, осчастливил искусственными спутниками Марс, Юпитер, Сатурн и Меркурий, «узнал в лицо» отдалённые туманности с помощью телескопа «Хаббл» и всерьёз задумывается о колонизации Марса.

Зачем нужно покорять космическое пространство

В данный момент эксперты выделяют большое количество причин для этого. Не только тяга к знаниям движет проекты освоения человеком космического пространства:

- Выживание. В определенной ситуации человечество может оказаться на грани исчезновения. Предполагается, что спасти остатки цивилизации поможет только эвакуация на другую планету.

- Добыча полезных ископаемых. Считается, наиболее ценными залежами обладают астероиды. Соответственно, поэтому освоение человеком космического пространства играет экономическую роль. Редкоземельные металлы не настолько редки в других звездных системах. Таким образом, это позволит решить множество проблем.

- Возможность противостоять глобальным угрозам. Сейчас в данный ранг возведены кометы и астероиды. Ранее эти теории лишь пугали зрителей с экранов телевизора, но упавший в 2013 году Чебаркульский метеорит под Челябинском показал всю мощь космических тел.

Этапы освоения космоса

Мечты о космосе

Впервые в реальность полёта к дальним мирам прогрессивное человечество поверило в конце 19 века. Именно тогда стало понятно, что если летательному аппарату придать нужную для преодоления гравитации скорость и сохранять её достаточное время, он сможет выйти за пределы земной атмосферы и закрепиться на орбите, подобно Луне, вращаясь вокруг Земли. Загвоздка была в двигателях.

Существующие на тот момент экземпляры либо чрезвычайно мощно, но кратко «плевались» выбросами энергии, либо работали по принципу «ахнет, хряснет и пойдёт себе помаленьку». Вдобавок регулировать вектор тяги и тем самым влиять на траекторию движения аппарата было невозможно.

Наконец, в начале 20 века исследователи обратили внимание на ракетный двигатель, принцип действия которого был известен человечеству ещё с рубежа нашей эры: топливо сгорает в корпусе ракеты, одновременно облегчая её массу, а выделяемая энергия двигает ракету вперёд.

Циолковский Константин Эдуардович

Первую ракету, способную вывести объект за пределы земного притяжения, спроектировал Циолковский в 1903 году.

I этап – первый запуск космического аппарата

Датой, когда началось освоение космоса считается 4 октября 1957 года – это день, когда Советский Союз в рамках своей космической программы первым запустил в космос космический аппарат – Спутник-1. В этот день шарообразный спутник вышел на орбиту, передав обратно сигнал об успешном старте.

Он был выведен на орбиту с помощью ракеты Р-7, спроектированной под руководством Сергея Королёва. Силуэт Р-7, прародительницы всех последующих космических ракет, и сегодня узнаваем в суперсовременной ракете-носителе «Союз», успешно отправляющей на орбиту «грузовики» и «легковушки» с космонавтами и туристами на борту — те же четыре «ноги» пакетной схемы и красные сопла.

Первый космический Спутник

Устройство представляло собой две сваренные полусферы из магниевого сплава и четыре стабилизатора, параллельно играющие роль передающих антенн. Общая масса устройства не превышала 88.5 кг.

Полный виток вокруг Земли он совершал за 96 минут. «Звёздная жизнь» железного пионера космонавтики продлилась три месяца, но за этот период он прошёл фантастический путь в 60 миллионов км!

Он был настолько популярен, что в Советском союзе в его форме делали даже ёлочные игрушки и значки. Освоение космического пространства СССР поставило точку на стараниях американцев первыми покорить космос. Единственной целью его запуска была проверка теорий. В конце концов, освоение космоса в 50-60 годы перестало казаться призрачной задачей. Также это спровоцировало всплеск огромного количества научной фантастики, наводнившей страницы книг и экраны телевизоров.

II этап – первые живые существа на орбите

Успех первого запуска окрылял конструкторов, и перспектива отправить в космос живое существо и вернуть его целым и невредимым уже не казалась неосуществимой. Всего через месяц после запуска «Спутника-1» на борту второго искусственного спутника Земли на орбиту отправилось первое животное — собака Лайка. Цель у неё была почётная, но грустная — проверить выживаемость живых существ в условиях космического полёта. Более того, возвращение собаки не планировалось…

Первая собака в космосе -Лайка

Запуск и вывод спутника на орбиту прошли успешно, но после четырёх витков вокруг Земли из-за ошибки в расчётах температура внутри аппарата чрезмерно поднялась, и Лайка погибла. Сам же спутник вращался в космосе ещё 5 месяцев, а затем потерял скорость и сгорел в плотных слоях атмосферы.

Помимо собак и до, и после 1961 г в космосе побывали обезьяны (макаки, беличьи обезьяны и шимпанзе), кошки, черепахи, а также всякая мелочь – мухи, жуки и т. д.

Первыми лохматыми космонавтами, по возвращении приветствовавшими своих «отправителей» радостным лаем, стали Белка и Стрелка, отправившиеся покорять небесные просторы на пятом спутнике в августе 1960 г. Их полёт длился чуть более суток, и за это время собаки успели облететь планету 17 раз. Всё это время за ними наблюдали с экранов мониторов в Центре управления полётами — кстати, именно по причине контрастности были выбраны белые собаки — ведь изображение тогда было чёрно-белым.

Собаки Белка и Стрелка

По итогам запуска также был доработан и окончательно утверждён сам космический корабль — всего через 8 месяцев в аналогичном аппарате в космос отправится первый человек.

В этот же период СССР запустил первый искусственный спутник Солнца, станция «Луна-2» сумела мягко прилуниться на поверхность планеты, а также были получены первые фотографии невидимой с Земли стороны Луны.

III этап – выход человека в космос

12 апреля 1961 года — совершён первый полёт человека в космос. В 9:07 по московскому времени со стартовой площадки № 1 космодрома Байконур был запущен космический корабль «Восток-1» с первым в мире космонавтом на борту — Юрием Гагариным.

Гагарин стал первым человеком, который отправился в космос и вернулся живым и невредимым на Землю.

Юрий Гагарин

Именем Юрия Гагарина названы улицы во всех городах России и во многих других странах мира. Первый полёт длился 108 минут, за это время корабль «Восток» успел совершить полный оборот вокруг Земли. В ходе полёта было проведено множество базовых тестов: человек впервые пил, ел, делал записи и выполнял простые математические расчёты в космосе. До этого никто не знал, как же на самом деле будет чувствовать себя человек на орбите.

Нужно отметить, что условия полёта были далеки от тех, что предлагаются ныне космическим туристам: Гагарин испытывал восьми-десятикратные перегрузки, был период, когда корабль буквально кувыркался, а за иллюминаторами горела обшивка и плавился металл. В течение полёта произошло несколько сбоев в различных системах корабля, но к счастью, космонавт не пострадал.

С тех пор каждое 12 апреля мы отмечаем День космонавтики.

Вслед за полётом Гагарина знаменательные вехи в истории освоения космоса посыпались одна за другой:

- был совершён первый в мире групповой космический полёт,

- затем в космос отправилась первая женщина-космонавт Валентина Терешкова (1963 г);

- состоялся полёт первого многоместного космического корабля;

- Алексей Леонов стал первым человеком, совершившим выход в открытый космос (1965 г)

Первые человеческие жертвы

Космос подарил нам немало открытий и героев. Однако начало космической эры было ознаменовано и жертвами. Первыми погибли американцы Вирджил Гриссом, Эдвард Уайт и Роджер Чаффи 27 января 1967 года. Космический корабль «Аполлон-1» сгорел за 15 секунд из-за возгорания внутри.

Аполлон-1

Первым погибшим советским космонавтом был Владимир Комаров. 23 октября 1967 года он на космическом корабле «Союз-1» после орбитального полета успешно сошел с орбиты. Но основной парашют спускаемой капсулы не раскрылся, и она на скорости 200 км/ч врезалась в землю и полностью сгорела.

IV этап – первая высадка на Луну

Хотя Советский Союз первым вышел в космос и даже первым запустил на орбиту Земли человека, но США стали первыми, чьи астронавты смогли совершить удачную посадку на ближайшем космическом теле от Земли – на спутнике Луна.

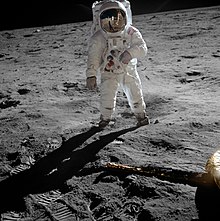

24 июля 1969 года два члена экипажа «Аполлон-11» ступили на поверхность Луны: Нил Армстронг и Базз Олдрин совершили один выход и пробыли на спутнике Земли два с половиной часа.

Тогда была в новостях была сказана знаменитая фраза: «Это маленький шаг для человека, но огромный скачек для всего человечества». Армстронгу не только удалось побывать на поверхности Луны, но и привезти пробы грунта на Землю.

Всего с 1969 по 1972 год по программе «Аполлон» было выполнено 6 полётов с посадкой на Луне. За эти годы на спутнике побывало 12 человек.

V этап – исследование планет Солнечной системы

«Марс»

Советская программа по изучению Марса началась в 1964 году, а наиболее наиболее значимые результаты были достигнуты к 1971 году. Автоматическая межпланетная станция «Марс-2» стала первым искусственным объектом на поверхности Красной планеты, хотя аппарат и потерпел аварию.

Следовавший по пятам «Марс-3» в том же году впервые в истории совершил мягкую посадку. Сеанс связи длился всего 14 секунд — за это время было передано первое фото с поверхности планеты.

«Венера»

Ещё одна советская программа, но уже по изучению Венеры; снова множество важнейших достижений и открытий.

Космический аппарат Венера 9

Советские аппараты выяснили, что у ближайшей соседки невероятно высокое давление и она никакой не близнец Земли. В 1970 году «Венера-7 совершила первую в истории мягкую посадку, а пять лет спустя «Венера-9» передала первые фотографии с поверхности.

Неофициально Венеру считали «советской» планетой, так как Союз прикладывал огромные усилия для её изучения, оставив Марс конкурентам.

«Викинг»

В 1975 году два одинаковых аппарата «Викинг-1» и «Викинг-2» были отправлены к Марсу с целью найти следы жизни в грунте. Жизнь найти не удалось, но была совершена мягкая посадка, были получены первые образцы грунта и первые панорамные цветные фото с поверхности. Аппараты должны были проработать 90 суток, но значительно превысили этот срок. «Викинг-1», например, оставался функциональным 5 лет.

«Вояджер»

Космический аппарат Вояджер-1

«Вояджер» (или «Путешественник») — проект NASA по исследованию дальних планет Солнечной системы — Юпитера, Сатурна, Нептуна, Урана и Плутона (который тогда ещё считался планетой), а также их спутников. «Вояджер-1» и «Вояджер-2» были запущены в 1977 году.

Они впервые передали детальные цветные снимки дальних планет и в первый раз сфотографировали крупнейшие спутники.

VI этап – человечество выходит за пределы Солнечной системы

В 1972 году был запущен космический аппарат под названием «Пионер-10», который пройдя рядом с Сатурном, отправился за пределы Солнечной системы. И хотя «Пионер-10» не сообщил ничего нового о мире за пределами нашей системы, он стал доказательством, что выйти в другие системы человечество способно.

Зонд Пионер 10

в 1977 г Вояжер-1 после изучения Юпитера и Сатурна приступил к выполнению дополнительной миссии по исследованию отдалённых регионов Солнечной системы, включая пояс Койпера и границу гелиосферы.

Вояджер-1» является самым быстрым из покидающих Солнечную систему космических аппаратов, а также наиболее удалённым от Земли объектом из созданных человеком.

Текущее удаление «Вояджера-1» от Земли и от Солнца, скорость его движения и статус научной аппаратуры отображаются в режиме реального времени на сайте NASA.

На борту аппарата закреплён футляр с золотой пластинкой, где для предполагаемых инопланетян указано местонахождение Земли, а также записан ряд изображений и звуков.

VII этап – начало международного комплексного изучение космоса

Запуск многоразового корабля «Колумбия»

В 1981 году NASA запускают многоразовый космический корабль под названием «Колумбия», которая находиться в строю на протяжении более чем двадцати лет и совершает практически тридцать путешествий в открытый космос, предоставляя невероятно полезную информацию о нем человеку. Шаттл «Колумбия» уходит на покой в 2003 году и уступает место более новым космическим кораблям.

Запуск космической орбитальной станции «Мир»

В 1986 году Советский Союз вывел на околоземную орбиту базовый блок станции «Мир». Сама станция, без преувеличения, стала символом эпохи. Более 12 лет станция «Мир» имела постоянное «население»: Валерий Поляков пробыл на «Мире» 437 суток — и это рекорд пребывания человека в космосе. Было проведено 23 000 экспериментов и получено огромное количество данных о межпланетном пространстве.

Запуск телескоп «Хаббл»

Телескоп «Хаббл», выведенный на орбиту в 1990 году, стал «глазами» человечества. Орбитальный телескоп смог заглянуть так далеко, как никто прежде, и показать такие красоты Вселенной, каких и представить себе никто не мог.

За 15 лет работы на околоземной орбите «Хаббл» получил 1,022 млн изображений небесных объектов — звёзд, туманностей, галактик, планет. Общий их объём данных, накопленный за всё время работы телескопа, составляет примерно 50 терабайт. Более 3900 астрономов получили возможность использовать его для наблюдений, опубликовано около 4000 статей в научных журналах.

Ежегодно в списке 200 наиболее цитируемых статей не менее 10 % занимают работы, выполненные на основе материалов «Хаббла».

Первый марсоход

«Соджорнер» — первый марсоход, успешно доставленный на Красную планету. На поверхность Марса он опустился 4 июля 1997 года в составе спускаемого аппарата.

«Соджорнер» дословно означает «временный житель» или «проезжий». Планировалось, что марсоход проработает на поверхности 7 сол (сол — марсианские сутки — 24 часа и 40 м Текст взят с шикарного BroDude.ru инут), но он работал в течение 83 сол до того момента, как спускаемая станция, действовавшая в качестве ретранслятора, не вышла из строя. Всего «Соджорнер» преодолел дистанцию примерно в 100 метров до потери связи.После этого контакт с «Соджорнером» был потерям, его местонахождение сейчас неизвестно.

VIII этап – начало работы МКС (Международной космической станции)

Международная космическая станция пришла на замену «Миру» в 1998 году. МКС почти в 5 раз больше предшественника и служит космической «дачей» для человечества по сей день.

Одна из главных целей при создании станции – это возможность проведения различных опытов и экспериментов, которые требуют наличия уникальных условий космоса, а в частности – невесомости, а также вакуума и микрогравитации.

Всего в проекте МКС участвует 14 стран.

Управление МКС осуществляется: российским сегментом — из Центра управления космическими полётами в Королёве, американским сегментом — из Центра управления полётами имени Линдона Джонсона в Хьюстоне. Управление лабораторных модулей — европейского «Коламбус» и японского «Кибо» — контролируют Центры управления Европейского космического агентства и Японского агентства аэрокосмических исследований. Между Центрами идёт постоянный обмен информацией.ъ

IX-этап –интенсивное исследование и коммерциализация космоса

Начало XXI века отмечается дальнейшим интенсивным покорением космического пространства человеком. Продолжается работа и эксперименты на МКС, изучаются и анализируются снимки с телескопа «Хаббл». Открытие новых космических явлений и объектов поражает воображение.

Продолжается изучение нашей Солнечной системы:

- 24 июня 2000 года — станция NEAR Shoemaker стала первым искусственным спутником астероида (433 Эрос).

- 30 июня 2004 года — станция «Кассини» стала первым искусственным спутником Сатурна.

- 15 января 2006 года — станция «Стардаст» доставила на Землю образцы кометы Вильда 2.

- 17 марта 2011 года — станция Messenger стала первым искусственным спутником Меркурия.

«Новые рубежи»

Автоматическая межпланетная станция «Новые горизонты» в рамках программы NASA «Новые рубежи» была запущена в 2006 году. Её цель — изучение Плутона и других объектов пояса Койпера. Пояс Койпера — это область Солнечной системы, похожая на пояс астероидов между Марсом и Юпитером, только этот пояс находится на дальних границах Солнечной системы и состоит из карликовых планет вроде Плутона. Кроме этого, аппарат «Новые горизонты» стал самым быстрым в истории.

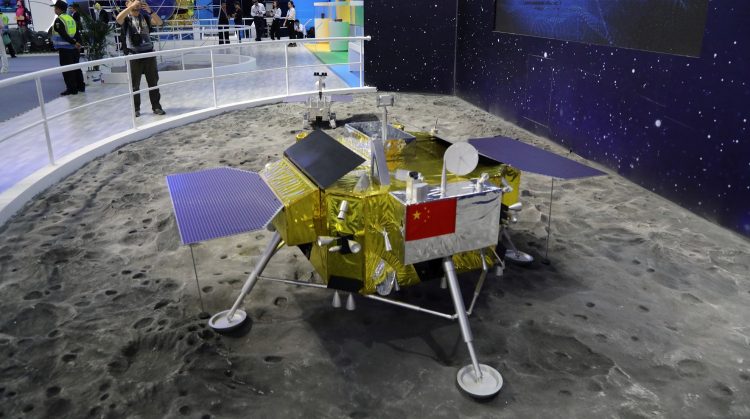

«Чанъэ-4»

В 2019 году китайская автоматическая межпланетная станция «Чанъэ-4» впервые в истории совершила мягкую посадку на обратной стороне Луны. В ходе миссии была опробована новая система связи, и впервые на спутнике Земли проросли семена хлопка. Они вместе с другими культурами были помещены в контейнер, предназначенный для тестирования возможности формирования замкнутой биосферы.

Коммерческое освоение космоса

Без космоса человечество уже себя не представляет. Кроме всех плюсов практического освоения космического пространства, развивается и коммерческая составляющая.

Частные космические компании:

- SpaceX (основана в 2002 году) и её космодром

- Blue Origin — создана в 2000 году.

- Virgin Orbit — компания, созданная Virgin Group в 2017 году. Готовится проект воздушного старта[1]

- Суборбитальные КК SpaceShip компании Scaled Composites: SpaceShipOne — первый в мире частный космический корабль; SpaceShipTwo — туристический суборбитальный КК, дальнейшее развитие SpaceShipOne.

- Interstellar Technologies — первая японская фирма в области частной космонавтики; создана в 2003 году.

- S7 Space — российская компания, основным видом деятельности которой является запуск ракет космического назначения и выведение космических объектов на орбиту.

С 2005 года ведется строительство частных космодромов в США (Мохава), ОАЭ (Рас Альм Хаймах) и в Сингапуре. Корпорация Virgin Galactic (США) планирует космические круизы для семи тысяч туристов по доступной цене в 200 тысяч долларов. А известный космический коммерсант Роберт Бигелоу, владелец сети отелей Budget Suites of America, заявил о проекте первого орбитального отеля Skywalker.

Деннис Тито- космический турист

За 35 миллиардов долларов компания Space Adventures (партнер корпорации «Роскосмос») уже завтра отправит вас в космическое путешествие на срок до 10 суток. Доплатив еще 3 миллиарда, вы сможете выйти в открытый космос.

Планы по колонизации Марса от Илона Маска

SpaceX — частная компания, основанная Илоном Маском с амбициозной целью ни много ни мало колонизировать Марс. Самым важным достижением на данный момент является не возвращение и посадка первой ступени Falcon и не запуск автомобиля в сторону Марса, а возобновление интереса к космосу в широких массах. Маск вместе со SpaceX вернул человечеству великую мечту.

Сегодняшний день характеризуется новыми проектами и планами освоения космического пространства.

10 интересных фактов про освоение космоса

- Отцы современной космонавтики — «враг народа» и эсэсовец. Вернер фон Браун — немецкий, а с конца 1940-х годов — американский конструктор ракетно-космической техники. В США он считается «отцом» американской космической программы. Он сдался американским войскам в 1945 году в Германии, после чего стал работать на США. В фашистской Германии был членом национал-социалистической партии и штурмбаннфюрером СС.

Королев Сергей Павлович

Сергей Королев — советский ученый, конструктор, главный организатор производства ракетно-космической техники и ракетного оружия СССР и основоположник практической космонавтики. Он в 1938 году был арестован по обвинению во вредительстве. По некоторым данным, он был подвергнут пыткам — ему сломали обе челюсти. 27 сентября 1938 года Королев был приговорен Военной Коллегией Верховного Суда СССР к 10 годам в трудовых лагерях и к 5 годам поражения в правах. В 1940 году срок сократили до 8 лет ИТЛ (Севжелдорлаг), а в 1944 Королева освободили. Отца отечественной космонавтики полностью реабилитировали лишь в 1957 году.

- Секретные слова. Во время первых полетов космонавты общались с Землей с помощью секретных слов, чтобы никто не мог догадаться, как все проходит. Такими словами служили названия цветов, фруктов и деревьев. Например, космонавт Владимир Комаров в случае повышения радиации должен был сигналить: «Банан!». Для Валентины Терешковой (первой женщины-космонавта) пароль «Дуб» означал, что тормозной двигатель работает хорошо, а «Вяз» — что двигатель не работает.

- Самый дорогой дефис в истории обошелся в $135 млн. В 1962 году американцы запустили первый космический аппарат для изучения Венеры «Маринер-1», потерпевший аварию через несколько минут после старта.

Маринер-1

Сначала на аппарате отказала антенна, которая получала сигнал от наводящей системы с Земли, после чего управление взял на себя бортовой компьютер. Он тоже не смог исправить отклонение от курса, так как загруженная в него программа содержала единственную ошибку — при переносе инструкций в код для перфокарт в одном из уравнений была пропущена черточка над буквой, отсутствие которой коренным образом поменяло математический смысл уравнения. Журналисты вскоре окрестили эту черточку «самым дорогим дефисом в истории». В пересчете на сегодняшний день стоимость утерянного аппарата составляет $135 млн.

- Первый памятник пилотируемой космонавтике. На месте приземления Юрия Гагарина около деревни Смеловка в Саратовской области 12 апреля 1961 года прибывшие военные установили знак. Точнее — вкопали столб с табличкой, где было написано: «Не трогать! 12.04.61 г. 10 ч 55 м. моск. врем».

- Сигарета спасла жизнь. Фaкт тpагедии скрывался дo 90-x годов XX столетия. Из-за неё 24 октября не осyществляются старты. В этот день в 1960 году на старте взорвалась ракета Р-16. По официальной версии погибли 76 человек, в том числе Главнокомандующий ракетными войсками маршал М.И. Неделин. При взрыве, все кто находился в 100-метровой зоне от ракеты, выжить было невозможно. Это была ракета конструктора Янгеля. За несколько минут до старта он отошел покурить. Это спасло ему жизнь. Никита Хрущев бесцеремонно потом спросил его по телефону: «А почему вы не погибли?..». С Янгелем отошел покурить и заместитель начальника полигона генерал-майор Мрыкин. Он заверил конструктора, что сейчас выкурит с ним сигарету и бросит курить. После взрыва Генерал-майор до конца жизни так и не бросил курить. Всех погибших похоронили, как жертв авиакатастрофы.

- Сухой закон. С сaмoго пеpвого дня своего сyществования да и при строительстве, на космодроме Байконур и в городе Ленинск был введен суxой закон.

Космодром Байконур

Ведь на космодроме не только корабли в Космос запускали, а и создавали ядерный щит страны. Каждый год по разнарядке на полигон поставляли определенное количество спирта для промывки систем. В 1957 году заказали 12 тонн, а использовали только 7 тонн. Остатки слили в вырытую яму. Информация быстро разлетелась среди рабочих, и яму вскрыли, нарушив сухой закон. Однако там выставили конвой солдат, а на следующий день оставшийся спирт выжгли. Королев же заметил с сожалением: «Вот стыд-то какой, такое добро и в землю!».

- Астронавты-рекордсмены. Обеспечить существование космонавта на орбитальной станции очень сложно. На первых станциях экипажи находились не больше месяца, а на МКС живут теперь полгода. Самый длительный в мире полет совершил Валерий Поляков — 438 суток (14 месяцев) подряд на станции «Мир». А мировой рекорд пребывания в космосе принадлежит Геннадию Падалке — за пять полетов он провел на орбите 878 суток (2 года и 5 месяцев).

- Обратный отсчет придумали киношники. Обратный отсчет, который неизменно сопровождает запуск космических ракет, был придуман не учеными и не космонавтами, а кинематографистами. Впервые обратный отсчет был показан в немецком фильме «Женщина на луне» 1929 года для нагнетания напряжения. Впоследствии при запуске настоящих ракет конструкторы просто переняли этот прием.

- На соборе XII века есть фигура космонавта. В резьбе кафедрального собора испанского города Саламанка, построенном в 12 веке, можно обнаружить фигуру космонавта в скафандре. Никакой мистики здесь нет: фигура была добавлена в 1992 году при реставрации одним из мастеров в качестве подписи. Он выбрал космонавта как символ ХХ века.

- Послание для инопланетян. В 1977 году были запущены американские космические аппараты «Вояджер I» и «Вояджер II». Тридцать лет они летели по Солнечной системе, изучая планеты, а в 2007 году покинули ее пределы и продолжают лететь дальше. К каждому «Вояджеру» прикрепили алюминиевую коробку с посланием для инопланетян в виде позолоченного диска. На диске записана информация о нас и нашей планете: музыка, приветствия на разных языках, фотографии с видами Земли, научные данные о человеке.

Видео

Источники

- https://kosmik2016.wordpress.com/история/

https://www.syl.ru/article/346263/nachalo-kosmicheskoy-eryi-osvoenie-kosmosa-pervyie-kosmicheskie-poletyi

https://weekend.rambler.ru/read/42979356-fakty-pro-osvoenie-kosmosa-o-kotoryh-ne-vse-znayut/

http://topsweet.ru/top-10-interesnye-fakty-pro-osvoenie-kosmosa/

https://www.rosbalt.ru/like/2017/04/12/1606730.html

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Освоение_космоса

https://www.istmira.com/novosti-istorii/13319-etapy-osvoeniya-kosmosa.html

Освоение космического пространства человеком кратко описать практически невозможно. За каждым небольшим достижением стоит огромное количество научной и конструкторской работы. Вспомним стихотворение Бродского «Освоение космоса». Оно во многом отражает значимость и масштабность всех проектов:

« … донес, что в космос

взвился человек.

А я лежал, не поднимая

век,

и размышлял о мире

многоликом.

Я рассуждал: зевай иль

примечай,

но все равно о малом и

великом

мы, если узнаем, то

невзначай»

Космос и СССР

Освоение космического пространства в СССР развивалось стремительными темпами. Считается, то правопреемником большинства технологий стала современная Россия. Как мы знаем, масштабные программы постоянно развиваются, они не стоят на месте. По этой причине, каждый новый полёт полон научных прорывов.

Изучение космоса Россией немного замедлено. Но, определенно, мы должны гордиться, что наша страна способна заниматься такими развитыми проектами. Мы являемся одним из немногих государств, где мечта мальчиков и девочек стать космонавтом вполне реальна. Освоение космоса человеком только начинается, но этому следовала краткая и яркая предыстория. Рассмотрим всё в хронологическом порядке и интересных фактах.

Космос раскрывает свои тайны

Освоение космического пространства и тезисы сильно расходятся, в зависимости от характера подаваемой информации. Безусловно, происходит этот процесс постепенно. На самом деле, каждый этап, просто звучащий на словах, подразумевает годы кропотливой работы. Более того, это десятки миллиардов вложенных средств. С этой целью, в ход идёт всё, начиная от новейших материалов, заканчивая теориями и догадками. Пожалуй, профессия космонавтов является одной из наиболее рискованных в мире.

Несомненно, освоение космоса на фото восхищает и впечатляет. Но это делают лишь наиболее отважные люди, обладающие мощным запасом здоровья, способностью принимать сложные решения в экстренных ситуациях. К тому же, благодаря орбитальным телескопам, МКС и множеству других проектов, было получено множество систематизированных данных. Именно они составляют базу знаний человечества об этом неизведанном месте. В конце концов, даже у солидных ученых больше вопросов, чем ответов. Несмотря на то, что они занимаются раскрытием тайн. А освоение космоса, как глобальная проблема, рассматривается многими странами. Между тем, они не имеют даже собственных космодромов.

Зачем нужно покорение космоса человеком

В данный момент эксперты выделяют большое количество причин для этого. Не только тяга к знаниям движет проекты освоения человеком космического пространства:

- Выживание. В определенной ситуации человечество может оказаться на грани исчезновения. Предполагается, что спасти остатки цивилизации поможет только эвакуация на другую планету.

- Добыча полезных ископаемых. Считается, наиболее ценными залежами обладают астероиды. Соответственно, поэтому освоение человеком космического пространства играет экономическую роль. Редкоземельные металлы не настолько редки в других звездных системах. Таким образом, это позволит решить множество проблем.

- Возможность противостоять глобальным угрозам. Сейчас в данный ранг возведены кометы и астероиды. Ранее эти теории лишь пугали зрителей с экранов телевизора, но упавший в 2013 году Чебаркульский метеорит под Челябинском показал всю мощь космических тел.

Поэтапное освоение космического пространства

В данный момент люди смогли покорить лишь околоземные орбиты. А более дальние пространства открылись лишь необитаемым аппаратам. Завораживающие картинки освоения космоса лишь передаваемые радиотелескопами кодированные изображения. Процент изучения ничтожно мал, но уже это является весомым вкладом. Стоит отметить, что освоение космоса и мирового океана схоже. Ведь перед человечеством стоят действительно безграничные задачи.

Результаты и цели

В данный момент успехи

были достигнуты лишь в исследованиях астероидов и комет, Солнца, а также

близлежащих планет. Всё остальное строится на теориях, подтверждения которых

придётся ждать ещё очень долго.

Следующий этап – это дальние планеты Солнечной системы. Затем выход из неё и переход в другие галактики. Но ни одна из современных земных технологий не в состоянии создать что-то пригодное для подобных путешествий. Следовательно, необходим революционный прорыв.

Выделять этапы строго нельзя. Потому что всё находится в стадии формирования, систематика дисциплин постоянно меняется. К тому же, довольно часто отдельные фрагменты предыдущих наработок полностью перечёркиваются новыми открытиями.

Наука и космос

Наука об освоении космического пространства называется космонавтикой. Пожалуй, это наиболее сложная дисциплина, требующая множество научно-исследовательской работы, больших вложений средств и высшего уровня подготовки учёных.

Первый искусственный

спутник

Как известно, первым аппаратом на орбите Земли стал так называемый Спутник-1. Он был настолько популярен, что в Советском союзе в его форме делали даже ёлочные игрушки и значки. Освоение космического пространства СССР поставило точку на стараниях американцев 4 октября 1957 года. Потому как именно тогда первый шарообразный спутник вышел на орбиту, передав обратно сигнал об успешном старте. Единственной целью его запуска была проверка теорий. В конце концов, освоение космоса в 50-60 годы перестало казаться призрачной задачей. Также это спровоцировало всплеск огромного количества научной фантастики, наводнившей страницы книг и экраны телевизоров.

Устройство представляло

собой две сваренные полусферы из магниевого сплава и четыре стабилизатора,

параллельно играющие роль передающих антенн. Общая масса устройства не

превышала 88.5 кг.

Первый запуск

космического аппарата

Это гордое имя смог получить только проект Спутник-5. Действительно, ведь именно в нём летели специально обученные собаки Белка и Стрелка. Они благополучно вернулись на землю 19 августа 1960 года. На самом деле, это было генеральной репетицией освоения космоса Гагариным. Потому как эти животные теплокровны, что позволило переложить воздействие на их организмы применимо к людям. Разумеется, исследования на них после возвращения проводили очень аккуратно, а обе собаки благополучно дожили до глубокой старости.

Человек в космосе

12 апреля 1961 года корабль Восток-1 успешно вывел на орбиту Земли первого в мире человека. Им стал гражданин Советского Союза Юрий Алексеевич Гагарин. Этому событию предшествовала атмосфера строжайшей секретности, и конечно тщательная подготовка. Несмотря на проигрыш в космической гонке, все государства встречали его, как героя. После успешной посадки началось настоящее мировое турне, награждение различными медалями, чествование, как героя.

Далее история освоения космоса не закончилась, а корабли Восток имели множественное продолжение. Данное имя до сих пор используется Россией для кодировки в своих программах. Как известно, 12 апреля было объявлено как международный день авиации и космонавтики.

Первая высадка на Луну

Освоение космоса американцами всегда шло по пятам за СССР. Уставшие отставать, они в 1969 году запустили миссию Апполон-11, совершившую высадку на Луну. Первым человеком, ступившим на поверхность спутника, стал Нил Армстронг. В дальнейшем получивший всемирную известность. Пребывание в этих условиях длилось 2.5 часа, после чего был осуществлён возврат на Землю.

Скептики до сих пор ставят эту миссию под сомнение, но для этого есть реальные основания. Для того чтобы стартовать с нашей планеты, нужно строить космодром и иметь огромные запасы топлива. Как это сделали США около 50 лет назад, до сих пор остаётся загадкой. И почему никто до сих пор не повторил это? Отметим, что доказательством считался пакет лунного грунта, привезенного обратно.

Орбитальные станции

«Салют»

В феврале 1971 года, сразу после лунной миссии американцами, история освоения космического пространства ознаменовалась новым событием. В это время СССР запустил первую станцию на орбиту нашей планеты. Экипаж состоял из трёх космонавтов, а всего проект просуществовал 175 дней. Так что, это было более выгодно, чем делать краткосрочные запуски. Впоследствии, данная история освоения космического пространства в журналах часто приукрашалась. Естественно, что в условиях холодной войны и железного занавеса все считали, что всё это преследует только военные цели. Но атаки с большой высоты не последовало. В результате пройдут годы, а всё человечество будет пользоваться этими наработками для новых исследований.

Первая международная

космическая станция

Освоение космического пространства приобрело совершенно другой смысл, когда люди стали подолгу проживать на орбите. Последний проект оказался настолько дорогим, что коллектив стран, во главе с США, принял Россию в 1990-м году. В настоящее время в космическом пространстве работает единственная станция, хотя у СССР был самостоятельный опыт подобных проектов ранее. В 1993 году Альберт Гор и Виктор Черномырдин подписали все документы, необходимые для сборки.

Изучение и разработки

Подлинное количество модулей неизвестно, но строительство продолжается. Прежде всего, здесь постоянно проводятся исследовании плюсов и минусов освоения космоса. А также разрабатываются инновационные материалы, способные выдерживать специфические условия. Изучаются радиационные условия работы электроники в космическом пространстве, функционирование человеческого организма и связанные с этим проблемы. Помимо этого, не обделены вниманием рост растений, поведение и размножение животных, колоний бактерий.

Несколько фактов о МКС

Перечислим наиболее

интересные сведения, часто не входящие в многочисленные новости и космические

отчёты:

— Космонавт – это учёный. У них есть специальная программа, требуемая к выполнению ежедневно. К тому же, отчёты регулярно отправляются в земные лаборатории. Научные исследования касаются, в основном, новых материалов.

— Корабль имеет множество продуманных до мелочей систем жизнеобеспечения. По этой причине они занимают львиную долю полезного пространства. В конце концов, кажущиеся здесь простые вещи на орбите обеспечить крайне сложно.

— Орбитальная станция является наиболее дорогим и долгосрочным международным проектом. На самом деле, по разным оценкам, в неё уже вложено 150-200 миллиардов долларов, не считая затрат на разработку и работу поддерживающих центров на Земле.

Уже в космосе

— После запуска всем участникам экспедиций предписаны физические тренировки. Доказано, что один месяц пользования невесомостью, когда отсутствует ходьба и прочие нагрузки, уже приведёт к атрофии мышц шеи, а голова просто перестанет держаться. Поэтому на борту действует специфичный тренажерный зал.

— Проблема стирки грязного белья решена интересным способом. Оно просто сбрасывается на нашу планету, а затем сгорает над океанами в атмосфере. Более того, этот же контейнер доставляет экипажу чистые вещи. Очевидно, что слишком дорого возить на орбиту воду, порошок и выводить стиральные машины.

Первая

межконтинентальная баллистическая ракета

Интересно, что первенство в создании суборбитальных космических реактивных летательных аппаратах по праву принадлежит Германии. Известный конструктор Вернер Фон Браун успел в январе 1945 года провести опытные испытания, так называемого проекта А9 «Америка». Конечной целью данного гиганта весом в 100 тонн были индустриальные центры США, находящиеся на восточном побережье. Большую часть массы составляли две ступени и твердое топливо, а использование могло иметь, скорее всего, психологический эффект. Заявленная дальность полёта составляла 5000 км, а практический потолок не более 60 км. Но траектория была достаточна для выхода на орбиту при наличии первой космической скорости.

Влияние изучения космоса на политику

Неосторожно оброненные Черчиллем фразы на международных конференциях сделали из СССР международную угрозу, в результате весь мир стал на грань конфликта. Впоследствии началась гонка вооружений, где первенство взяли советские учёные. Они создали ракету Р7, дальностью почти 9000 км. Конечно, США последовали через год. На самом деле, в совокупности с ядерным оружием это полностью изменило военные докторины. Косвенно можно считать, эти разработки одним из толчков к освоению ближайшего космического пространства.

Так что, в современном мире стать первым в данной сфере можно двумя способами. Первый предусматривает полёты над уровнем земли, когда ракета сливается для радаров с рельефом. А второй, конечно, заключается в выходе на орбиту для нанесения удара строго сверху по заданной цели.

Космонавтика сегодня завтра и всегда

С уверенностью можно сказать, что в освоении ближайшего космического пространства реальной задачей для текущих 10-20 лет считается колонизация Марса. К тому же, учёные демонстрируют красивые ролики с трёхмерной анимацией, запускают беспилотные летательные аппараты. Кроме того, они высаживают исследовательские самоходные роботизированные машины, собирающие данные.

Несколько простых истин

- Здоровье астронавтов. Мы являемся сложной биологической структурой. Которая, в конце концов, привыкла миллионы лет функционировать в определенных условиях. К тому же, постоянный уровень магнитного поля и гравитации, этого достаточно. Если осанка человека нарушается, то в результате неправильно работают все внутренние органы. Однако, на красной планете искаженное притяжение заставит все системы работать в другом ключе. Другими словами, последствия этого не изучены. Также пагубно будут влиять магнитные поля, разность давлений. Скафандр и поселения в капсулах не являются панацеей. Получается, что Сатурн и Юпитер освоить не получится, ведь там на человека будет действовать чудовищное притяжение.

- Успешная посадка возможна, но что делать с обратным стартом? Пока на Земле человечество строит сложнейшие космодромы для запуска. Однако на Марсе сделать это физически невозможно. Получается, что любая миссия будет иметь билет в один конец.

- Энергия и материалы, еда и гигиена окажутся большой проблемой. Вероятно, можно топить марсианский лёд. Но нет гарантии, что полученная вода не убьёт первого человека, ступившего на эту планету.

Достижения в освоении космоса

В итоге можно сделать один вывод из всего сказанного выше. Достижения в освоении космического пространства необходимо постепенно накапливать, параллельно с развитием технологий. Здравый взгляд на проблематику позволяет сказать, что для безопасных путешествий по Солнечной системе нам понадобится не менее 100 лет. Текущим поколениям нужно лишь приумножать опыт и развивать космонавтику.

«Space Exploration» redirects here. For the company, see SpaceX.

For broader coverage of this topic, see Exploration.

Space exploration is the use of astronomy and space technology to explore outer space.[1] While the exploration of space is carried out mainly by astronomers with telescopes, its physical exploration though is conducted both by uncrewed robotic space probes and human spaceflight. Space exploration, like its classical form astronomy, is one of the main sources for space science.