Неважно, чем вызваны уродства — генетикой или факторами окружающей среды, они всегда вызывали любопытство людей во всём мире. Некоторые обладатели уродств просто принимают себя такими, какие они есть, и живут полноценной жизнью. Некоторые идут на рискованные операции в надежде изменить свою внешность. Некоторые присоединяются к цирку, и используют ярлык «урод» для заработка. А некоторые просто прячутся подальше, дабы люди не шарахались от них в ужасе.

1. Роговая кератома

Роговая кератома (cornu cutaneum) возникает тогда, когда кератин принимает коническую форму и проступает наружу сквозь кожу в виде рогов. Поражения кожи, которые обнаруживаются у основания этих рогов, могут быть как злокачественными, так и доброкачественными. Кожные рога появляются, как правило, у людей со светлой кожей, возраст которых 50 лет и более. Причём открытые участки кожи наиболее восприимчивы к возникновению этого отклонения. Для точного определения его причины часто проводится биопсия, так как рога часто бывают связаны с самыми разными заболеваниями — от обычной бородавки до болезни Боуэна. Большинство рогов доброкачественные, однако около 20% способны вызвать рак, а ещё 20% вызывают различные предраковые состояния.

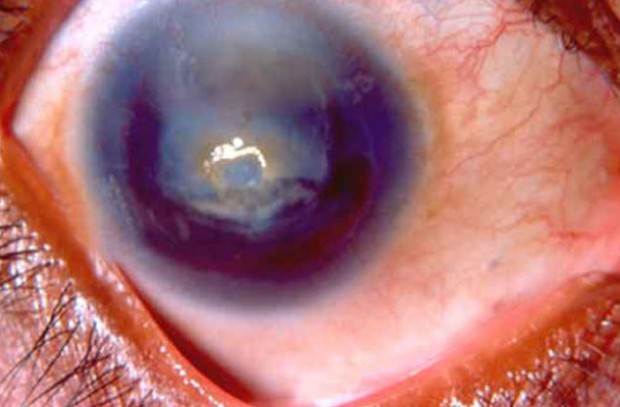

2. Аниридия

Совершенно чёрные глаза — это не обязательно признак абсолютного зла. Состояние под названием аниридия способно лишить цвета радужку глаза, что в свою очередь может привести к сильному ослаблению зрения и высокой чувствительности к свету.

Буквальный перевод слова «аниридия» — «без радужной оболочки». Из-за аниридии могут развиться и другие болезни, такие, как глаукома и катаракта. Тот, кто страдает аниридией, может быть или полностью слеп, или может видеть достаточно хорошо для того, чтобы двигаться. Это состояние вызывает генетическая мутация. Происходит она приблизительно в конце первого триместра беременности, как раз тогда, когда у плода развиваются глаза. Аниридия — наследственное заболевание. Если она была у кого-то из родителей, то с вероятностью 50% она может возникнуть и у детей.

3. Рекурвация коленных суставов

Люди с рекурвацией коленных суставов в состоянии сгибать колени назад. В наиболее тяжёлых случаях такое состояние может быть обусловлено врождённым вывихом коленей. В других случаях причиной может быть разница в длине ног или тяжёлое заболевание, такое, как церебральный паралич или рассеянный склероз. Ещё одной причиной может стать физическая травма коленного сустава. Произойти это может во время занятий спортом, или в ходе автомобильной аварии, к примеру. В лечении этого заболевания может помочь хирургия и физиотерапия. Также могут использоваться специальные скобы для ног. В зависимости от того, насколько эффективным окажется лечение, для некоторых пациентов это состояние может стать причиной постоянной инвалидности. На сегодняшний день наиболее известным примером рекурвации коленных суставов является Элла Харпер (Ella Harper), жившая в штате Теннесси в 1870-м году. Передвигаться ей приходилось на четвереньках. Её называли «девочка-верблюд».

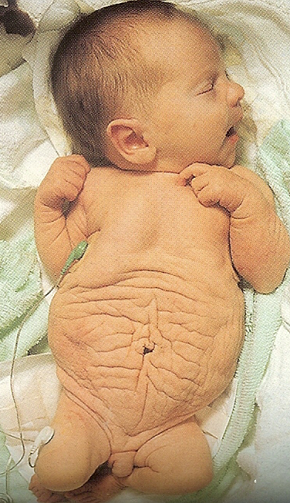

4. Синдром недостаточности мышц живота

Более известный как синдром Игла-Барретта, синдром недостаточности мышц живота вызывает сильную слабость мышц брюшного пресса. Это приводит к тому, что живот отвисает, сморщивается, и по внешнему виду напоминает чернослив. Мочевой пузырь больного в такой ситуации испытывает постоянное давление, при этом опорожнить его пациенту бывает очень трудно. Это приводит к возникновению целого спектра сопутствующих осложнений. Эти осложнения могут затронуть внутренние органы, гениталии и даже скелет пациента. Причины возникновения данного заболевания к настоящему моменту точно не определены. Вполне возможно, что синдром недостаточности мышц живота — это наследственное заболевание, так как многочисленные случаи были зафиксированы в семьях. Когда плод ещё только развивается в утробе матери, то признаки этого заболевания можно увидеть уже во время УЗИ. Почти все пациенты, страдающие этим синдромом — мужчины, а точнее, их 95%. Дети с этим заболеванием часто рождаются мёртвыми, а оставшиеся в живых после рождения часто умирают в очень раннем возрасте, из-за осложнений заболевания.

5. Эктродактилия

Люди, родившиеся с эктродактилией, как правило имеют уродства на обеих руках или ногах. Для коррекции этого состояния приходится прибегать к помощи хирургов. Известная также как «синдром клешней» эктродактилия представляет собой отсутствие нескольких пальцев на руках или ногах. Оставшиеся пальцы рук или ног часто бывают соединены друг с другом перепонкой из кожи. Если деформирована только одна конечность, то скорее всего, это случилось из-за не-наследственной генетической мутации. Если же деформация наблюдается на обеих руках или ногах, то заболевание было унаследовано. У родителей с дефектным геном есть 50% шанс передать заболевание своим потомкам.

6. Нейрофиброматоз

Пациенты с нейрофиброматозом имеют особые опухоли (нейрофибромы) возникающие на месте нервов или под кожей. Нейрофибромы могут быть удалены хирургическим путём, но лишь частично. Но даже если удалить их нельзя, они в большинстве случаев не вызывают осложнений, так как являются доброкачественными. Есть два типа нейрофиброматоза, самый распространённый тип называется болезнью Реклингхаузена. Она может быть наследственной. У родителей с болезнью Реклингхаузена есть 50% шанс передать её своим детям. Если же в семейной истории болезней ранее не наблюдалось пациентов с этим заболеванием, то это означает, что оно вызвано генетической мутацией.

7. Полителия

8. Хвостовидный придаток

Хвостовидный придаток — это человеческий хвост, который не похож на хвост животного. Потому что человеческие хвосты не помогают людям сохранять равновесие или отмахиваться от мух. В некоторых случаях хвостовидный придаток может быть симптомом серьёзных заболеваний позвоночника, таких, как расщепление позвоночных дуг. Хвостовидный придаток есть у всех людей, пока они находятся в утробе матери. Но как правило, этот придаток исчезает ещё до рождения ребёнка. Однако не каждый плод развивается предсказуемо. Если придаток не рассосался в утробе, ребёнок рождается с хвостом. Хвост обычно состоит из жира, мышц, нервов и кровеносных сосудов. И в нём не бывает ни хрящей, ни костей. У мужчин это отклонение проявляется в два раза чаще, чем у женщин. Хвостовидный придаток может быть удалён хирургическим путём, при условии, что такая операция будет признана безопасной.

9. Полимастия

Когда на теле человека неожиданно появляется дополнительная молочная железа, такое состояние называется полимастия. Дополнительные молочные железы, как правило, появляются там же, где и дополнительные соски: молочные линии и пах. Но иногда они могут возникать и на ягодицах, спине, бёдрах и даже на лице. Высока вероятность того, что такая молочная железа может содержать в себе злокачественную опухоль, и угрожать здоровью пациента. Также следует отметить, что полимастия — это аномалия, которая распространяется за пределы человеческого вида. У нескольких приматов также было диагностировано это состояние. У животных это большая редкость, однако наука официально подтвердила, что существует такая вещь, как полимастия у обезьян.

10. Гипертрихоз

Гипертрихоз также известен как синдром Амбраса. А ещё его иногда называют «синдромом оборотня». Из-за генетических отклонений у людей с гипертрихозом появляется избыточное количество волос, которые могут расти либо по всему телу, либо концентрироваться в какой-то одной области. На данный момент официально зафиксировано менее 60 случаев гипертрихоза, но это не просто какая-то редкость для истории. Люди с гипертрихозом живут и сегодня. В 2010-м году Супатра «Нэт» Сасуфан из Тайланда попал в книгу рекордов Гиннеса как самый волосатый подросток на планете.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For the claim that something is good or right because it is natural (or bad or wrong because it is unnatural), see Appeal to nature.

In philosophical ethics, the naturalistic fallacy is the claim that any reductive explanation of good, in terms of natural properties such as pleasant or desirable, is false. The term was introduced by British philosopher G. E. Moore in his 1903 book Principia Ethica.[1]

Moore’s naturalistic fallacy is closely related to the is–ought problem, which comes from David Hume’s A Treatise of Human Nature (1738–40). However, unlike Hume’s view of the is–ought problem, Moore (and other proponents of ethical non-naturalism) did not consider the naturalistic fallacy to be at odds with moral realism.

The naturalistic fallacy should not be confused with the appeal to nature, which is exemplified by forms of reasoning such as «Something is natural; therefore, it is morally acceptable» or «This property is unnatural; therefore, this property is undesirable.» Such inferences are common in discussions of medicine, sexuality, environmentalism, gender roles, race, and carnism.

Different common uses[edit]

The is–ought problem[edit]

The term naturalistic fallacy is sometimes used to describe the deduction of an ought from an is (the is–ought problem).[2] This usually takes the form of saying that If people do something (e.g., eat three times a day, smoke cigarettes, dress warmly in cold weather), then people ought to do that thing. It becomes a naturalistic fallacy when the is–ought problem («People eat three times a day, so it is morally good for people to eat three times a day») is justified by claiming that whatever practice exists is a natural one («because eating three times a day is pleasant and desirable»).

In using his categorical imperative, Kant deduced that experience was necessary for its application. But experience on its own or the imperative on its own could not possibly identify an act as being moral or immoral. We can have no certain knowledge of morality from them, being incapable of deducing how things ought to be from the fact that they happen to be arranged in a particular manner in experience.

Bentham, in discussing the relations of law and morality, found that when people discuss problems and issues they talk about how they wish it would be, instead of how it actually is. This can be seen in discussions of natural law and positive law. Bentham criticized natural law theory because in his view it was a naturalistic fallacy, claiming that it described how things ought to be instead of how things are.

Moore’s discussion[edit]

The title page of Principia Ethica

According to G. E. Moore’s Principia Ethica, when philosophers try to define good reductively, in terms of natural properties like pleasant or desirable, they are committing the naturalistic fallacy.

…the assumption that because some quality or combination of qualities invariably and necessarily accompanies the quality of goodness, or is invariably and necessarily accompanied by it, or both, this quality or combination of qualities is identical with goodness. If, for example, it is believed that whatever is pleasant is and must be good, or that whatever is good is and must be pleasant, or both, it is committing the naturalistic fallacy to infer from this that goodness and pleasantness are one and the same quality. The naturalistic fallacy is the assumption that because the words ‘good’ and, say, ‘pleasant’ necessarily describe the same objects, they must attribute the same quality to them.[3]

In defense of ethical non-naturalism, Moore’s argument is concerned with the semantic and metaphysical underpinnings of ethics. In general, opponents of ethical naturalism reject ethical conclusions drawn from natural facts.

Moore argues that good, in the sense of intrinsic value, is simply ineffable: it cannot be defined because it is not a natural property, being «one of those innumerable objects of thought which are themselves incapable of definition, because they are the ultimate terms by reference to which whatever ‘is’ capable of definition must be defined».[4] On the other hand, ethical naturalists eschew such principles in favor of a more empirically accessible analysis of what it means to be good: for example, in terms of pleasure in the context of hedonism.

That «pleased» does not mean «having the sensation of red», or anything else whatever, does not prevent us from understanding what it does mean. It is enough for us to know that «pleased» does mean «having the sensation of pleasure», and though pleasure is absolutely indefinable, though pleasure is pleasure and nothing else whatever, yet we feel no difficulty in saying that we are pleased. The reason is, of course, that when I say «I am pleased», I do not mean that «I» am the same thing as «having pleasure». And similarly no difficulty need be found in my saying that «pleasure is good» and yet not meaning that «pleasure» is the same thing as «good», that pleasure means good, and that good means pleasure. If I were to imagine that when I said «I am pleased», I meant that I was exactly the same thing as «pleased», I should not indeed call that a naturalistic fallacy, although it would be the same fallacy as I have called naturalistic with reference to Ethics.

In §7, Moore argues that a property is either a complex of simple properties, or else it is irreducibly simple. Complex properties can be defined in terms of their constituent parts but a simple property has no parts. In addition to good and pleasure, Moore suggests that colour qualia are undefined: if one wants to understand yellow, one must see examples of it. It will do no good to read the dictionary and learn that yellow names the colour of egg yolks and ripe lemons, or that yellow names the primary colour between green and orange on the spectrum, or that the perception of yellow is stimulated by electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength of between 570 and 590 nanometers, because yellow is all that and more, by the open question argument.

Bernard Williams called Moore’s use of the term naturalistic fallacy, a «spectacular misnomer», the question being metaphysical, as opposed to rational.[5]

Appeal to nature[edit]

Some people use the phrase, naturalistic fallacy or appeal to nature, in a different sense, to characterize inferences of the form «Something is natural; therefore, it is morally acceptable» or «This property is unnatural; therefore, this property is undesirable.» Such inferences are common in discussions of medicine, homosexuality, environmentalism, and veganism.

The naturalistic fallacy is the idea that what is found in nature is good. It was the basis for social Darwinism, the belief that helping the poor and sick would get in the way of evolution, which depends on the survival of the fittest. Today, biologists denounce the naturalistic fallacy because they want to describe the natural world honestly, without people deriving morals about how we ought to behave (as in: If birds and beasts engage in adultery, infanticide, cannibalism, it must be OK).

Criticism[edit]

Some philosophers reject the naturalistic fallacy and/or suggest solutions for the proposed is–ought problem.

Bound-up functions[edit]

Ralph McInerny suggests that ought is already bound up in is, insofar as the very nature of things have ends/goals within them. For example, a clock is a device used to keep time. When one understands the function of a clock, then a standard of evaluation is implicit in the very description of the clock, i.e., because it is a clock, it ought to keep the time. Thus, if one cannot pick a good clock from a bad clock, then one does not really know what a clock is. In like manner, if one cannot determine good human action from bad, then one does not really know what the human person is.[7][page needed]

Irrationality of anti-naturalistic fallacy[edit]

Certain uses of the naturalistic fallacy refutation (a scheme of reasoning that declares an inference invalid because it incorporates an instance of the naturalistic fallacy) have been criticized as lacking rational bases, and labelled anti-naturalistic fallacy.[8][page needed] For instance, Alex Walter wrote:

- «The naturalistic fallacy and Hume’s ‘law’ are frequently appealed to for the purpose of drawing limits around the scope of scientific inquiry into ethics and morality. These two objections are shown to be without force.»[9]

The refutations from naturalistic fallacy defined as inferring evaluative conclusions from purely factual premises[10] do assert, implicitly, that there is no connection between the facts and the norms (in particular, between the facts and the mental process that led to adoption of the norms).

Effects of putative necessities[edit]

The effect of beliefs about dangers on behaviors intended to protect what is considered valuable is pointed at as an example of total decoupling of ought from is being impossible. A very basic example is that if the value is that rescuing people is good, different beliefs on whether or not there is a human being in a flotsam box leads to different assessments of whether or not it is a moral imperative to salvage said box from the ocean. For wider-ranging examples, if two people share the value that preservation of a civilized humanity is good, and one believes that a certain ethnic group of humans have a population level statistical hereditary predisposition to destroy civilization while the other person does not believe that such is the case, that difference in beliefs about factual matters will make the first person conclude that persecution of said ethnic group is an excusable «necessary evil» while the second person will conclude that it is a totally unjustifiable evil. The same is also applicable to beliefs about individual differences in predispositions, not necessarily ethnic. In a similar way, two people who both think it is evil to keep people working extremely hard in extreme poverty will draw different conclusions on de facto rights (as opposed to purely semantic rights) of property owners depending on whether or not they believe that humans make up justifications for maximizing their profit, one who believes that people do concluding it necessary to persecute property owners to prevent justification of extreme poverty while the other person concludes that it would be evil to persecute property owners. Such instances are mentioned as examples of beliefs about reality having effects on ethical considerations.[11][12]

Inconsistent application[edit]

Some critics of the assumption that is-ought conclusions are fallacies point at observations of people who purport to consider such conclusions as fallacies do not do so consistently. Examples mentioned are that evolutionary psychologists who gripe about «the naturalistic fallacy» do make is-ought conclusions themselves when, for instance, alleging that the notion of the blank slate would lead to totalitarian social engineering or that certain views on sexuality would lead to attempts to convert homosexuals to heterosexuals. Critics point at this as a sign that charges of the naturalistic fallacy are inconsistent rhetorical tactics rather than detection of a fallacy.[13][14]

Universally normative allegations of varied harm[edit]

A criticism of the concept of the naturalistic fallacy is that while «descriptive» statements (used here in the broad sense about statements that purport to be about facts regardless of whether they are true or false, used simply as opposed to normative statements) about specific differences in effects can be inverted depending on values (such as the statement «people X are predisposed to eating babies» being normative against group X only in the context of protecting children while the statement «individual or group X is predisposed to emit greenhouse gases» is normative against individual/group X only in the context of protecting the environment), the statement «individual/group X is predisposed to harm whatever values others have» is universally normative against individual/group X. This refers to individual/group X being «descriptively» alleged to detect what other entities capable of valuing are protecting and then destroying it without individual/group X having any values of its own. For example, in the context of one philosophy advocating child protection considering eating babies the worst evil and advocating industries that emit greenhouse gases to finance a safe short term environment for children while another philosophy considers long term damage to the environment the worst evil and advocates eating babies to reduce overpopulation and with it consumption that emits greenhouse gases, such an individual/group X could be alleged to advocate both eating babies and building autonomous industries to maximize greenhouse gas emissions, making the two otherwise enemy philosophies become allies against individual/group X as a «common enemy». The principle, that of allegations of an individual or group being predisposed to adapt their harm to damage any values including combined harm of apparently opposite values inevitably making normative implications regardless of which the specific values are, is argued to extend to any other situations with any other values as well due to the allegation being of the individual or group adapting their destruction to different values. This is mentioned as an example of at least one type of «descriptive» allegation being bound to make universally normative implications, as well as the allegation not being scientifically self-correcting due to individual or group X being alleged to manipulate others to support their alleged all-destructive agenda which dismisses any scientific criticism of the allegation as «part of the agenda that destroys everything», and that the objection that some values may condemn some specific ways to persecute individual/group X is irrelevant since different values would also have various ways to do things against individuals or groups that they would consider acceptable to do. This is pointed out as a falsifying counterexample to the claim that «no descriptive statement can in itself become normative».[15][16]

See also[edit]

- Appeal to nature

- Evidence-based medicine

- Appeal to novelty

- Appeal to tradition

- Definist fallacy

- Evolution of morality

- Fact–value distinction

- Meta-ethics

- Moralistic fallacy

- Philosophical naturalism

- Norm (philosophy)

- Open-question argument

- Principia Ethica

- The Right and the Good

- Value theory

Notes[edit]

- ^ Moore, G.E. Principia Ethica § 10 ¶ 3

- ^ W. H. Bruening, «Moore on ‘Is-Ought’,» Ethics 81 (January 1971): 143–49.

- ^ Prior, Arthur N. (1949), Chapter 1 of Logic And The Basis Of Ethics, Oxford University Press (ISBN 0-19-824157-7)

- ^ Moore, G.E. Principia Ethica § 10 ¶ 1

- ^ Williams, Bernard Arthur Owen (2006). Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-415-39984-5.

- ^ Sailer, Steve (October 30, 2002). «Q&A: Steven Pinker of ‘Blank Slate’«. UPI. Archived from the original on December 5, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2015.

- ^ McInerny, Ralph (1982). «Chp. 3». Ethica Thomistica. Cua Press.

- ^ Casebeer, W. D., «Natural Ethical Facts: Evolution, Connectionism, and Moral Cognition», Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, (2003)

- ^ Walter, Alex (2006). «The Anti-naturalistic Fallacy: Evolutionary Moral Psychology and the Insistence of Brute Facts». Evolutionary Psychology. 4: 33–48. doi:10.1177/147470490600400102.

- ^

«naturalistic fallacy», TheFreeDictionary. - ^ Susana Nuccetelli, Gary Seay (2011) «Ethical Naturalism: Current Debates»

- ^ Peter Simpson (2001) «Vices, Virtues, and Consequences: Essays in Moral and Political Philosophy»

- ^ Jan Narveson (2002) «Respecting persons in theory and practice: essays on moral and political philosophy»

- ^ H. J. McCloskey (2013) «Meta-Ethics and Normative Ethics»

- ^ Steven Scalet, John Arthur (2016) «Morality and Moral Controversies: Readings in Moral, Social and Political Philosophy»

- ^ N.T. Potter, Mark Timmons (2012) «Morality and Universality: Essays on Ethical Universalizability»

References[edit]

- Moore, George Edward (1903). Principia Ethica. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-334-04040-X.

Further reading[edit]

- Frankena, W. K. (1939). «The Naturalistic Fallacy». Mind. XLVIII (192): 464–77. doi:10.1093/mind/XLVIII.192.464. JSTOR 2250706.

- Curry, Oliver (2006). «Who’s afraid of the naturalistic fallacy?». Evolutionary Psychology. 4: 234–47. doi:10.1177/147470490600400120.

- Walter, Alex (2006). «The anti-naturalistic fallacy: Evolutionary moral psychology and the insistence of brute facts». Evolutionary Psychology. 4: 33–48. doi:10.1177/147470490600400102.

- Wilson, David Sloan; Dietrich, Eric; Clark, Anne B. (2003). «On the inappropriate use of the naturalistic fallacy in evolutionary psychology». Biology and Philosophy. 18 (5): 669–81. doi:10.1023/A:1026380825208. S2CID 30891026.

External links[edit]

- Principia Ethica Archived 2021-04-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). «G.E. Moore». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). «Moral non-naturalism». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Appeal to Nature entry in The Fallacy Files

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For the claim that something is good or right because it is natural (or bad or wrong because it is unnatural), see Appeal to nature.

In philosophical ethics, the naturalistic fallacy is the claim that any reductive explanation of good, in terms of natural properties such as pleasant or desirable, is false. The term was introduced by British philosopher G. E. Moore in his 1903 book Principia Ethica.[1]

Moore’s naturalistic fallacy is closely related to the is–ought problem, which comes from David Hume’s A Treatise of Human Nature (1738–40). However, unlike Hume’s view of the is–ought problem, Moore (and other proponents of ethical non-naturalism) did not consider the naturalistic fallacy to be at odds with moral realism.

The naturalistic fallacy should not be confused with the appeal to nature, which is exemplified by forms of reasoning such as «Something is natural; therefore, it is morally acceptable» or «This property is unnatural; therefore, this property is undesirable.» Such inferences are common in discussions of medicine, sexuality, environmentalism, gender roles, race, and carnism.

Different common uses[edit]

The is–ought problem[edit]

The term naturalistic fallacy is sometimes used to describe the deduction of an ought from an is (the is–ought problem).[2] This usually takes the form of saying that If people do something (e.g., eat three times a day, smoke cigarettes, dress warmly in cold weather), then people ought to do that thing. It becomes a naturalistic fallacy when the is–ought problem («People eat three times a day, so it is morally good for people to eat three times a day») is justified by claiming that whatever practice exists is a natural one («because eating three times a day is pleasant and desirable»).

In using his categorical imperative, Kant deduced that experience was necessary for its application. But experience on its own or the imperative on its own could not possibly identify an act as being moral or immoral. We can have no certain knowledge of morality from them, being incapable of deducing how things ought to be from the fact that they happen to be arranged in a particular manner in experience.

Bentham, in discussing the relations of law and morality, found that when people discuss problems and issues they talk about how they wish it would be, instead of how it actually is. This can be seen in discussions of natural law and positive law. Bentham criticized natural law theory because in his view it was a naturalistic fallacy, claiming that it described how things ought to be instead of how things are.

Moore’s discussion[edit]

The title page of Principia Ethica

According to G. E. Moore’s Principia Ethica, when philosophers try to define good reductively, in terms of natural properties like pleasant or desirable, they are committing the naturalistic fallacy.

…the assumption that because some quality or combination of qualities invariably and necessarily accompanies the quality of goodness, or is invariably and necessarily accompanied by it, or both, this quality or combination of qualities is identical with goodness. If, for example, it is believed that whatever is pleasant is and must be good, or that whatever is good is and must be pleasant, or both, it is committing the naturalistic fallacy to infer from this that goodness and pleasantness are one and the same quality. The naturalistic fallacy is the assumption that because the words ‘good’ and, say, ‘pleasant’ necessarily describe the same objects, they must attribute the same quality to them.[3]

In defense of ethical non-naturalism, Moore’s argument is concerned with the semantic and metaphysical underpinnings of ethics. In general, opponents of ethical naturalism reject ethical conclusions drawn from natural facts.

Moore argues that good, in the sense of intrinsic value, is simply ineffable: it cannot be defined because it is not a natural property, being «one of those innumerable objects of thought which are themselves incapable of definition, because they are the ultimate terms by reference to which whatever ‘is’ capable of definition must be defined».[4] On the other hand, ethical naturalists eschew such principles in favor of a more empirically accessible analysis of what it means to be good: for example, in terms of pleasure in the context of hedonism.

That «pleased» does not mean «having the sensation of red», or anything else whatever, does not prevent us from understanding what it does mean. It is enough for us to know that «pleased» does mean «having the sensation of pleasure», and though pleasure is absolutely indefinable, though pleasure is pleasure and nothing else whatever, yet we feel no difficulty in saying that we are pleased. The reason is, of course, that when I say «I am pleased», I do not mean that «I» am the same thing as «having pleasure». And similarly no difficulty need be found in my saying that «pleasure is good» and yet not meaning that «pleasure» is the same thing as «good», that pleasure means good, and that good means pleasure. If I were to imagine that when I said «I am pleased», I meant that I was exactly the same thing as «pleased», I should not indeed call that a naturalistic fallacy, although it would be the same fallacy as I have called naturalistic with reference to Ethics.

In §7, Moore argues that a property is either a complex of simple properties, or else it is irreducibly simple. Complex properties can be defined in terms of their constituent parts but a simple property has no parts. In addition to good and pleasure, Moore suggests that colour qualia are undefined: if one wants to understand yellow, one must see examples of it. It will do no good to read the dictionary and learn that yellow names the colour of egg yolks and ripe lemons, or that yellow names the primary colour between green and orange on the spectrum, or that the perception of yellow is stimulated by electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength of between 570 and 590 nanometers, because yellow is all that and more, by the open question argument.

Bernard Williams called Moore’s use of the term naturalistic fallacy, a «spectacular misnomer», the question being metaphysical, as opposed to rational.[5]

Appeal to nature[edit]

Some people use the phrase, naturalistic fallacy or appeal to nature, in a different sense, to characterize inferences of the form «Something is natural; therefore, it is morally acceptable» or «This property is unnatural; therefore, this property is undesirable.» Such inferences are common in discussions of medicine, homosexuality, environmentalism, and veganism.

The naturalistic fallacy is the idea that what is found in nature is good. It was the basis for social Darwinism, the belief that helping the poor and sick would get in the way of evolution, which depends on the survival of the fittest. Today, biologists denounce the naturalistic fallacy because they want to describe the natural world honestly, without people deriving morals about how we ought to behave (as in: If birds and beasts engage in adultery, infanticide, cannibalism, it must be OK).

Criticism[edit]

Some philosophers reject the naturalistic fallacy and/or suggest solutions for the proposed is–ought problem.

Bound-up functions[edit]

Ralph McInerny suggests that ought is already bound up in is, insofar as the very nature of things have ends/goals within them. For example, a clock is a device used to keep time. When one understands the function of a clock, then a standard of evaluation is implicit in the very description of the clock, i.e., because it is a clock, it ought to keep the time. Thus, if one cannot pick a good clock from a bad clock, then one does not really know what a clock is. In like manner, if one cannot determine good human action from bad, then one does not really know what the human person is.[7][page needed]

Irrationality of anti-naturalistic fallacy[edit]

Certain uses of the naturalistic fallacy refutation (a scheme of reasoning that declares an inference invalid because it incorporates an instance of the naturalistic fallacy) have been criticized as lacking rational bases, and labelled anti-naturalistic fallacy.[8][page needed] For instance, Alex Walter wrote:

- «The naturalistic fallacy and Hume’s ‘law’ are frequently appealed to for the purpose of drawing limits around the scope of scientific inquiry into ethics and morality. These two objections are shown to be without force.»[9]

The refutations from naturalistic fallacy defined as inferring evaluative conclusions from purely factual premises[10] do assert, implicitly, that there is no connection between the facts and the norms (in particular, between the facts and the mental process that led to adoption of the norms).

Effects of putative necessities[edit]

The effect of beliefs about dangers on behaviors intended to protect what is considered valuable is pointed at as an example of total decoupling of ought from is being impossible. A very basic example is that if the value is that rescuing people is good, different beliefs on whether or not there is a human being in a flotsam box leads to different assessments of whether or not it is a moral imperative to salvage said box from the ocean. For wider-ranging examples, if two people share the value that preservation of a civilized humanity is good, and one believes that a certain ethnic group of humans have a population level statistical hereditary predisposition to destroy civilization while the other person does not believe that such is the case, that difference in beliefs about factual matters will make the first person conclude that persecution of said ethnic group is an excusable «necessary evil» while the second person will conclude that it is a totally unjustifiable evil. The same is also applicable to beliefs about individual differences in predispositions, not necessarily ethnic. In a similar way, two people who both think it is evil to keep people working extremely hard in extreme poverty will draw different conclusions on de facto rights (as opposed to purely semantic rights) of property owners depending on whether or not they believe that humans make up justifications for maximizing their profit, one who believes that people do concluding it necessary to persecute property owners to prevent justification of extreme poverty while the other person concludes that it would be evil to persecute property owners. Such instances are mentioned as examples of beliefs about reality having effects on ethical considerations.[11][12]

Inconsistent application[edit]

Some critics of the assumption that is-ought conclusions are fallacies point at observations of people who purport to consider such conclusions as fallacies do not do so consistently. Examples mentioned are that evolutionary psychologists who gripe about «the naturalistic fallacy» do make is-ought conclusions themselves when, for instance, alleging that the notion of the blank slate would lead to totalitarian social engineering or that certain views on sexuality would lead to attempts to convert homosexuals to heterosexuals. Critics point at this as a sign that charges of the naturalistic fallacy are inconsistent rhetorical tactics rather than detection of a fallacy.[13][14]

Universally normative allegations of varied harm[edit]

A criticism of the concept of the naturalistic fallacy is that while «descriptive» statements (used here in the broad sense about statements that purport to be about facts regardless of whether they are true or false, used simply as opposed to normative statements) about specific differences in effects can be inverted depending on values (such as the statement «people X are predisposed to eating babies» being normative against group X only in the context of protecting children while the statement «individual or group X is predisposed to emit greenhouse gases» is normative against individual/group X only in the context of protecting the environment), the statement «individual/group X is predisposed to harm whatever values others have» is universally normative against individual/group X. This refers to individual/group X being «descriptively» alleged to detect what other entities capable of valuing are protecting and then destroying it without individual/group X having any values of its own. For example, in the context of one philosophy advocating child protection considering eating babies the worst evil and advocating industries that emit greenhouse gases to finance a safe short term environment for children while another philosophy considers long term damage to the environment the worst evil and advocates eating babies to reduce overpopulation and with it consumption that emits greenhouse gases, such an individual/group X could be alleged to advocate both eating babies and building autonomous industries to maximize greenhouse gas emissions, making the two otherwise enemy philosophies become allies against individual/group X as a «common enemy». The principle, that of allegations of an individual or group being predisposed to adapt their harm to damage any values including combined harm of apparently opposite values inevitably making normative implications regardless of which the specific values are, is argued to extend to any other situations with any other values as well due to the allegation being of the individual or group adapting their destruction to different values. This is mentioned as an example of at least one type of «descriptive» allegation being bound to make universally normative implications, as well as the allegation not being scientifically self-correcting due to individual or group X being alleged to manipulate others to support their alleged all-destructive agenda which dismisses any scientific criticism of the allegation as «part of the agenda that destroys everything», and that the objection that some values may condemn some specific ways to persecute individual/group X is irrelevant since different values would also have various ways to do things against individuals or groups that they would consider acceptable to do. This is pointed out as a falsifying counterexample to the claim that «no descriptive statement can in itself become normative».[15][16]

See also[edit]

- Appeal to nature

- Evidence-based medicine

- Appeal to novelty

- Appeal to tradition

- Definist fallacy

- Evolution of morality

- Fact–value distinction

- Meta-ethics

- Moralistic fallacy

- Philosophical naturalism

- Norm (philosophy)

- Open-question argument

- Principia Ethica

- The Right and the Good

- Value theory

Notes[edit]

- ^ Moore, G.E. Principia Ethica § 10 ¶ 3

- ^ W. H. Bruening, «Moore on ‘Is-Ought’,» Ethics 81 (January 1971): 143–49.

- ^ Prior, Arthur N. (1949), Chapter 1 of Logic And The Basis Of Ethics, Oxford University Press (ISBN 0-19-824157-7)

- ^ Moore, G.E. Principia Ethica § 10 ¶ 1

- ^ Williams, Bernard Arthur Owen (2006). Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-415-39984-5.

- ^ Sailer, Steve (October 30, 2002). «Q&A: Steven Pinker of ‘Blank Slate’«. UPI. Archived from the original on December 5, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2015.

- ^ McInerny, Ralph (1982). «Chp. 3». Ethica Thomistica. Cua Press.

- ^ Casebeer, W. D., «Natural Ethical Facts: Evolution, Connectionism, and Moral Cognition», Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, (2003)

- ^ Walter, Alex (2006). «The Anti-naturalistic Fallacy: Evolutionary Moral Psychology and the Insistence of Brute Facts». Evolutionary Psychology. 4: 33–48. doi:10.1177/147470490600400102.

- ^

«naturalistic fallacy», TheFreeDictionary. - ^ Susana Nuccetelli, Gary Seay (2011) «Ethical Naturalism: Current Debates»

- ^ Peter Simpson (2001) «Vices, Virtues, and Consequences: Essays in Moral and Political Philosophy»

- ^ Jan Narveson (2002) «Respecting persons in theory and practice: essays on moral and political philosophy»

- ^ H. J. McCloskey (2013) «Meta-Ethics and Normative Ethics»

- ^ Steven Scalet, John Arthur (2016) «Morality and Moral Controversies: Readings in Moral, Social and Political Philosophy»

- ^ N.T. Potter, Mark Timmons (2012) «Morality and Universality: Essays on Ethical Universalizability»

References[edit]

- Moore, George Edward (1903). Principia Ethica. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-334-04040-X.

Further reading[edit]

- Frankena, W. K. (1939). «The Naturalistic Fallacy». Mind. XLVIII (192): 464–77. doi:10.1093/mind/XLVIII.192.464. JSTOR 2250706.

- Curry, Oliver (2006). «Who’s afraid of the naturalistic fallacy?». Evolutionary Psychology. 4: 234–47. doi:10.1177/147470490600400120.

- Walter, Alex (2006). «The anti-naturalistic fallacy: Evolutionary moral psychology and the insistence of brute facts». Evolutionary Psychology. 4: 33–48. doi:10.1177/147470490600400102.

- Wilson, David Sloan; Dietrich, Eric; Clark, Anne B. (2003). «On the inappropriate use of the naturalistic fallacy in evolutionary psychology». Biology and Philosophy. 18 (5): 669–81. doi:10.1023/A:1026380825208. S2CID 30891026.

External links[edit]

- Principia Ethica Archived 2021-04-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). «G.E. Moore». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). «Moral non-naturalism». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Appeal to Nature entry in The Fallacy Files

Ошибки эволюции: причудливые животные, о существовании которых вы могли не знать

Автор:

30 ноября 2021 11:50

Природа удивительна, и это факт. Порой в ней можно отыскать что-то, что совсем не вписывается в наше привычное понимание. Иногда – просто потому, что эволюция работает не так, чтобы мы наслаждались исключительно внешним видом животного. Собрали самые странные повороты эволюции, которые можно найти даже сейчас.

Индийская фиолетовая лягушка (пурпурная)

Источник:

Очевидно, эти амфибии водятся в Индии, но чаще всего распространены в горном хребте Западные Гаты.

От своих более нормальных и более зеленых сородичей они отличаются тем, что имеют лиловатый цвет и телом, не совсем характерным для лягушки.

Источник:

Почти всю свою жизнь они живут под землей, а на поверхность выходят только в период спаривания – и то всего на неделю в году. Питаются они термитами и роющими насекомыми.

Этот район они выбрали как раз из-за того, что для жизни им необходимы лесные почвы. Находят их очень редко из-за их скрытного образа жизни.

Велелла

Источник:

Эти морские обитатели только кажутся опасными. С самого детства большинство из нас знают, что чем красивее медуза, тем она смертоноснее.

Источник:

Но не в этом случае. Это животное, хоть и похоже на какой-то космический корабль или же на древнюю пирамиду Майя, совершенно безвредно. Оно питается икрой мелких рыб и планктоном. Человеку оно навредить не может.

Звездоносый крот

Источник:

Вот это животное действительно может напугать. Его нос – в форме звезды, которая на самом деле является обычными придатками, с помощью которых он ориентируется в пространстве.

Источник:

Сам крот не очень большой, и обитает он в Северной Америке.

Голый землекоп

Источник:

Не любите крыс? А вот эта, как будто вывернутая наизнанку крыса, плевать хотела на ваши предпочтения.

Источник:

Выглядит она страшно, но на самом деле, вы с ней можете даже никогда не встретиться. Голый землекоп обитает в Восточной Африке, и белый и лысый он потому, что лишен чувствительности кожи. Таким образом он противостоит суровым внешним условиям, в которых постоянно живет.

Мадагаскарская руконожка айе-айе

Источник:

А вот этот зверек выглядит так, будто он только что увидел что-то, чего не должен был.

Источник:

В основном найти его можно только после захода солнца. Относится он к приматам, но имеет очень острые зубы, чтобы раздирать кору деревьев и питаться насекомыми.

Так что можно сказать, что это животное скорее дятел, чем обезьяна. Но, в целом, очень милое.

Хохлач

Источник:

Это странное создание обитает только в Центральной и Северной Атлантике, и на голове у него как будто заранее надетый спасательный жилет.

Источник:

И этот капюшон действительно надувается – животное делает это через ноздри, а сдувает его под водой. И не для того, чтобы не всплывать – так он общается с другими своими сородичами.

Голубоногая олуша

Источник:

Эта странная птица в свое время покорила интернет и стала героиней множества мемов.

Источник:

Такие синие ноги у нее потому, что она ест пищу, богатую каротиноидными пигментами. Нет, она не модница, просто так получилось.

Обезьяна уакари

Источник:

Эта странная обезьяна живет в тропических лесах Амазонки. У нее рыжая голова, которая скорее напоминает о марвеловском злодее Красном Черепе.

Источник:

Шерсть у них рыжая, так что можно предположить, что души у них и вовсе нет. Но еще примечательно это животное тем, что у них короткий хвост.

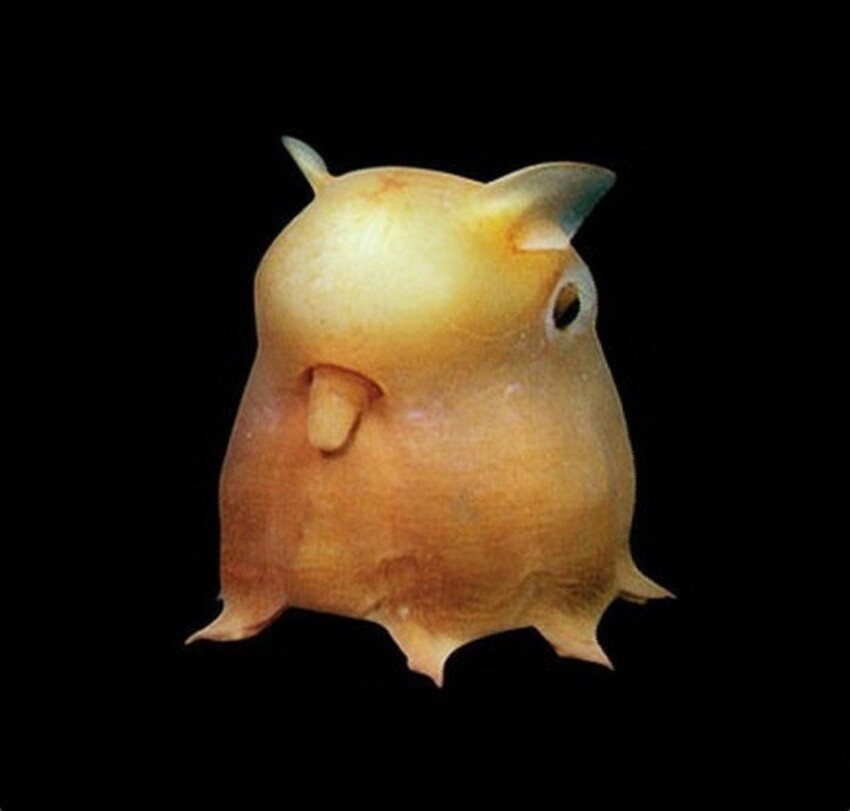

Глубоководный осьминог Дамбо

Источник:

Этот маленький, но гордый осьминог получил свое название из-за своих ушей. Правда, это скорее плавники, но они отсылают к персонажу Disney.

Источник:

Обитает он на глубине свыше 3,5 километров, так что найти его – большая удача для дайвера.

Рыба паку

Источник:

Милейшее создание, мечта стоматолога. Не верите? Посмотрите еще раз.

Источник:

Это – родственница пираний, обитающая в Южной Америке. В длину это животное может достигать метра, а весить – до 40 кг. Обитают поодиночке, едят фрукты. Вас – вряд ли съедят. Но могут попытаться.

Шерстяная свинья Мангалица

Источник:

Кто бы мог подумать, что этот свинтус появился лишь в XIX веке в Венгрии путем скрещивания домашних свиней и кабанов?

Источник:

Она – единственная в своем роде. Шерсти кроме нее нет ни у одной свиньи из ныне существующих. Может заменить овцу, если очень постараться.

Источник:

Ссылки по теме:

Новости партнёров

реклама