The Top Mathematical Syntax Errors in Sage

This page is for help with the mathematical syntax used in Sage generally, and in particular inside CoCalc.

There is a highly related page

for working with and editing CoCalc worksheets,

including help with the user-interface.

The Good News: The 16—21 errors described here (depending on how you count) are easily responsible for over 95% of mistakes that I see students making in mid-level undergraduate math courses. (e.g. integral calculus, multi-variable calculus, differential equations, matrix algebra, discrete math, …) In fact, the first five errors might be responsible for 80% just by themselves.

Remember: if you don’t find what you need, or if you’d like to ask a question, then please email help@sagemath.com at any time. We’d love to hear from you! Please include a link (the URL address in your browser) to any relevant project or document, as part of your email.

Context: A worksheet is a file ending in .sagews and is subdivided into cells. Each cell has an input region and an output region, which might be 0, 1, 2, or many lines long. The input can be mathematical, in the Sage syntax, or it could be in many other formats, including markdown, html, R, and so forth. This page deals with Sage, and not those other languages.

List of Categories:

- Category 1. Implicit Multiplication

- Category 2. Did you forget to declare a variable?

- Category 3. Huge error messages appear

-

Category 4. Mismatched parentheses

- Note 4$frac{1}{3}$. Automatic Syntax Highlighting

- Note 4$frac{2}{3}$. Showing a Function

- Category 5. Commas in the middle of large numbers

-

Category 6. Capitalizing the built-in functions

- Note 6$frac{1}{2}$. A Note about «log» versus «ln»

- Category 7. Parameters in the wrong order

- Category 8. Your internet connection has silently gone down

-

Category 9. Misspelling a command

- Category 9$frac{3}{4}$. Getting help without remembering the name of a command

-

Category 10. Scientific notation mistakes

- Note 10$frac{1}{2}$. The tale of the damaged identity matrix

- Category 11. Using currency signs inside of equations

- Category 12. Mistakes involving the percent sign

- Category 13. Line-breaks where they aren’t permitted

- Category 14. Using indentation that Python doesn’t approve of

- Category 15. Missing a colon in Python commands that have subordinate commands

- Category 16. Using brackets or braces as higher-order parentheses

Citation: By the way, much of this information has been taken from Sage for Undergraduates, a book written by Gregory V. Bard and published by The American Mathematical Society in 2015. (The pdf-file of that book is available for free, and the print version has an extremely low price.) This file is largely based on Appendix A: «What to do When Frustrated!» of that book.

1. Implicit multiplication

This particular case is best explained with an example:

solve( x^3 - 5x^2 + 6x == 0, x ) <— Wrong!

is not correct. You must type instead

solve( x^3 - 5*x^2 + 6*x == 0, x )

In other words, Sage needs that asterisk or multiplication symbol between the coefficients 5 and 6, and the terms to which they are attached: namely $x^2$ and $x$. For some reason, trigonometric functions really cause this confusion for some users. Sage will reject

f(x) = 5cos( 6x ) <— Wrong!

but will accept

f(x) = 5*cos( 6*x )

Another common manifestation is

f(x) = x(x+1) <— Wrong!

but instead it should be

f(x) = x*(x+1)

In defense of Sage, it should be noted that Java, C, C++, Python, FORTRAN, Pascal, BASIC, and many other computer languages have this same rule. However, for those users who find this extremely frustrating, there is a way out of this requirement. If you place the following line

implicit_multiplication(True)

at the start of a CoCalc session, then you will be in «implicit multiplication mode.»

Consider the following code:

implicit_multiplication(True)

g=(12+3x)/(-12+2x)

plot( g, 2, 8, ymin=-30, ymax=30 )

Note that the definition of $g$ above does not have an asterisk between the 3 and the first $x$ nor between the 2 and the second $x$. Because we are in «implicit multiplication mode,» those two missing asterisks are forgiven.

Note about SageMathCell: At this particular moment (July 6th, 2016) the implicit_multiplication trick will work in CoCalc, but not in SageMathCell.

2. Did you forget to declare a variable?

The declaration of variables can be something confusing to those who have not done a lot of programming in the years prior to learning Sage. In languages such as C, C++, and Java, all the variables must be declared—no exceptions. In Sage, the variable $x$ is pre-declared. All other variables have to be declared, except variables that are declared in a way that you could call «implicit declaration.» I’ll explain implicit declaration in a moment.

Let’s say that I want to graph a sphere,

$ x^2 + y^2 + z^2 = r^2 $

for the value $r=5$. As you can see, I need $x$, $y$, and $z$ to write that equation, but I also have a constant $r=5$. Therefore, I must declare the $y$ and the $z$ with var("y z") very early in my code, perhaps at the first or second line.

The $r$ can be declared «implicitly.» For example, if I give the command r=5 then Sage will understand that $r$ is a variable. Therefore, a var("r") is not needed.

The variable $x$ is always pre-declared, so there’s absolutely no need to declare var("x") in my code.

var("y z")

r=5

implicit_plot3d( x^2 + y^2 + z^2 == r^2, (x,-r,r), (y,-r,r), (z,-r,r) )

For stylistic reasons, some users like to declare $x$ anyway. They would

therefore type var("x y z") in place of var("y z") because there is no impact in Sage to the redundant declaration of $x$. Of course, visually there is a difference—it treats $x$ in a more egalitarian way among $x$, $y$, and $z$.

Finally, functions (e.g. $f(x)$ or $g(x)$) do not have to be declared—they are defined via a special Sage-specific syntax. Just to summarize, consider the following code:

var("t")

g = 9.82

f1(t) = 3 - 5*t

f2(t) = 4 + 5*t

f3(t) = 7 + 0.5*g*t^2

plot( [ f1(t), f2(t), f3(t) ], (t, 0, 2), gridlines="minor" )

We have to declare $t$, because it is a variable, and we’re not putting a value into it. The $f_1(t)$, $f_2(t)$, and $f_3(t)$ need not be declared, because they are functions. Lastly, we do not have to declare $g$, because when we assign 9.82 to $g$, we are declaring it implicitly.

The reason for this is the preparser.

The transformation for declaring a function to the underlying Python code looks like that:

sage: preparse("f1(t) = 3 - 5*t")

actually defines t as a variable, then creates the right hand side expression in t and finally calls the method .function(t) to declare this intermediate symbolic expression to be a function in t.

__tmp__=var("t")

f1 = symbolic_expression(Integer(3) - Integer(5)*t).function(t)

3. Huge error messages appear

In almost all cases, when something incorrect is inputted into Sage, an extremely long error message appears. This many-lined report can be extremely intimidating, and even moderately experienced Sage users might not know what to make of it.

This is actually called a «stack trace» and it is very useful to experienced programmers, who can use it to locate a bug very rapidly. However (for new users) it can be very intimidating. The key is to realize that the last line of the error message is usually the most useful.

Whenever you have a huge error message, start with the very last line. That’s often all you need. Alternatively, some students find it easier to ignore the error message entirely, read their own code, and figure out what is wrong themselves.

4. Mismatched Parentheses

Matching parentheses can be tricky, and therefore some users can get frustrated by mismatched parentheses. Luckily, Sage has two great features to help you with this commonly performed task.

4$frac{1}{3}$. Automatic syntax highlighting

This feature is better demonstrated by an example. With cut-and-paste, put the following code into a cell of a CoCalc worksheet.

f(x) = 1/(1 + 1/(3 + 1/(5 + 1/(7 + 1/(1 + 1/(3 + 1/(5 + 1/(7 + x))))))))

plot( f(x), -5, 5 )

Now click on f(x), and scroll with the arrow keys along that long expresion. What you’ll see is that the parentheses will turn green as you pass over them. Now, if you look carefully at the right of the expression, whenever you pass over a «$($», the matching «$)$» will also turn green simultaneously. This helps you identify which parentheses match with which other parentheses.

While the previous example was a bit contrived, a real-world example is the following function, which represents the future value (after $t$ years) of a sequence of annual deposits of 1000 dollars, invested at 6% compounded monthly.

v(t) = 1000*((1+0.005)^(12*t)-1)/0.005

As you can see, there are six parentheses (three left and three right), and indeed, it can be tricky to get their placement exactly right.

4$frac{2}{3}$. Showing a function

Sometimes, after entering a function, it can be a great help to use the show(f(x)) command to see if you’ve got it right or not. For example,

f(x) = 1/(1 + 1/(3 + 1/(5 + 1/(7 + 1/(1 + 1/(3 + 1/(5 + 1/(7 + x))))))))

show(f(x))

produces the lovely (and correct) image below:

5. Commas in the middle of large numbers

The comma is a very important symbol in most computer languages, including Python, on which Sage is based. That’s why we do not use commas inside of large numbers when programming in almost any computer language.

As an example, the correct syntax for solving

$$begin{array}{rcl}

59x + 79y & = & 572 \

x + y & = & 8 \

end{array}$$

is to type

var("x y")

solve( [59*x + 79*y == 572, x + y == 8] , [x,y] )

and press shift+enter.

However, the highly related problem

$$begin{array}{rcl}

59x + 79y & = & 28,233

x + y & = & 387

end{array}$$

is not solved by typing

var("x y")

solve( [59*x + 79*y == 28,233, x + y == 387 ] , [x,y] )

but instead, you should remove the comma from inside the 28,233. In other words, you should type instead

var("x y")

solve( [59*x + 79*y == 28233, x + y == 387 ] , [x,y] )

This is even more important for very large numbers, like 7,255,881. We really want to have those two interior commas in a number that large, when we write text such as in an email or on MathExchange. However, while programming, we do not use the interior commas.

Instead, you should type

var("x y")

solve( [15163*x + 20303*y == 7255881, 257*x + 257*y == 99459 ] , [x,y] )

which correctly computes the answer $x=117$ and $y=270$.

6. Capitalizing the built-in functions

When using Sage, we should be very careful not to capitalize the built-in functions. For example, the following code is correct:

print(sin(pi/4))

print(ln(e^3))

print(sqrt(60))

print(arctan(1))

While the following code is incorrect, because the initial letters of the built-in functions have been (illegally) capitlized.

print(Sin(pi/4))

print(Ln(e^3))

print(Sqrt(60))

print(Arctan(1))

By the way, if you look in most calculus textbooks, you will see that it is a long-standing tradition not to capitalize those initial letters.

6$frac{1}{2}$. A note about «log» vs «ln»:

While we’re talking about the built-in functions, it might be nice to clarify an issue about log and ln. In higher mathematics, the useful logarithm is almost always the natural logarithm, not the common logarithm or the binary logarithm. For this reason, higher mathematics textbooks, such as those used in the university curriculum after the midpoint of a math degree, use log(x) to mean the natural logarithm of $x$.

Yet, high-school mathematics textbooks, and many textbooks used in freshman calculus or precalculus, use the following notation:

-

ln(x)is the natural logarithm of $x$. (In other words, base $e$.) -

ld(x)is the binary logarithm of $x$. (In other words, base $2$.) -

log(x)is the common logarithm of $x$. (In other words, base $10$.) - It should be noted that the last one is very popular in both chemistry and geology. For example, pH uses the common logarithm, as does the Richter scale for earthquakes.

In any case, to be compatible with higher mathematics textbooks, Sage uses log(x) internally to mean the natural logarithm of $x$, not the common logarithm.

Yet, if you type ln(x), Sage will understand and allow it. This leads to an odd situation. If you type ln(17) then Sage will respond log(17), and that can be rather confusing to a precalculus student.

7. Parameters in the wrong order

When programming, it is very easy to get the parameters in the wrong order.

Consider the following example. Let’s suppose that I’m asked to find the 4th-degree Taylor approximation to the function $f(x)=sqrt{x}$ computed about the point $x=9$.

Therefore, I type taylor( sqrt(x), x, 4, 9 ) and I get back something very strange. The response is

715/8589934592*(x - 4)^9 - 429/1073741824*(x - 4)^8 + 33/16777216*(x - 4)^7 - 21/2097152*(x - 4)^6 + 7/131072*(x - 4)^5 - 5/16384*(x - 4)^4 + 1/512*(x - 4)^3 - 1/64*(x - 4)^2 + 1/4*x + 1

which is weird because I am expecting a 4th-degree polynomial, and I have a 9th-degree polynomial instead. Moreover, the repeated appearance of $(x-4)$ makes it seem as though the polynomial were constructed about $x=4$ and not about $x=9$.

I should have typed instead taylor( sqrt(x), x, 9, 4 ) to do that. I get the much more reasonable answer of

-5/279936*(x - 9)^4 + 1/3888*(x - 9)^3 - 1/216*(x - 9)^2 + 1/6*x + 3/2

which is a polynomial of the fourth degree. Because I see repeated uses of $(x-9)$, I know it is constructed about $x=9$.

This whole episode shows you that the order of parameters matters a lot. Moreover, if you do exchange two parameters, then you might be asking for something valid, but very different from your intension.

The best way to painlessly avoid this problem is to type taylor? which will bring up a help window about the taylor command. You can glue a question mark to the end of any command, and Sage will bring up the help window for you.

8. Your internet connection has silently gone down

Few things can be more frustrating than a computer program which has become unresponsive, especially if you’re working on something important. Sometimes, if working in a coffee-shop or a hotel, your wifi access will expire. This cuts off your internet connection, and severs the link between your computer and CoCalc.

CoCalc has a very handy feature. If you look in the upper-right corner of your web-browser window, you’ll see a wifi-symbol, followed by a number, the unit «milliseconds» (abbreviated as «ms») and then a pair of diagonal arrows point at each other. Here’s an example:

That means I have a good connection, and the latency is 66 milliseconds. In other words, a packet leaving CoCalc will arrive at my computer about 0.066 sec after it was sent. Alternatively, if my internet connection were to go down suddenly, I’d see something that looks like this:

and that’s how I know that my internet connection has gone down. So if a command that normally works stops working, be sure and glance up and see—perhaps you’ve lost your internet connection!

9. Misspelling a command

Let’s say that I want to make a nice 3D plot of some algebraic surface which is defined implicitly. Yet, perhaps I have forgotten… is the command implicit_plot3D? implicitplot3D? implicitplot3d? implicit_plot3d? or implicitPlot3D?

What I should do, in a SageMathCell, is type imp and then hit the tab button. After a few moments, a handy pull-down list appears with the five commands that begin with the letters «imp.»

Sometimes, a command is a method of some object. For example, look at the following code.

A = matrix( 3, 3, [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9])

print(A)

A.rref()

The rref command «belongs» to A, because this command is only for matrices, and A is a matrix. (The way to say this in computer science is «rref is a method of the object A, which has class matrix.»)

What if I forget that the command is rref? If you type the first two lines of the previous code block, and then type (on the third line) type only A.r followed by the tab button, then you get a rather long list of commands which would be suitable for that situation. Of course, rref is among them.

In the next remark, we’ll explain what you should do if you’ve forgotten the name of a command.

9$frac{3}{4}$. Getting help without remembering the name of a command

If you remember the name of a command, such as A.rref(), then you can use the question mark operator to get help for it, as we discussed in the previous question above. However, if you’ve forgotten the command to compute a null space (just to pick an example), then you have several options.

- Search in Google for: null space «sage reference manual»

- Search in Google for: null space site:sagemath.org

- Download a copy of the book Sage for Undergraduates, by Gregory Bard, published by the American Mathematical Society in 2015. The electronic version is a 100% free pdf file.

Note: That middle option deserves some further information. The term site:sagemath.org, with no spaces on either side of the colon, will restrict Google to search on webpages whose URL ends in sagemath.org and therefore your search is far more focused. Of course, you can use this with any URL that you like. Sometimes it is useful to search with site:edu.

There used to be a command called search_doc, but in many cases it has been rendered inoperative, for technical reasons.

10. Scientific notation mistakes

The letter e in Sage usually refers to 2.718281828… just like in calculus and related courses. However, it sometimes indicates scientific notation.

For example, if you type 10^19.39 into Sage, then the reply will be 2.45470891568503e19.

Now, if you want to multiply this answer by 2, …

-

You should type

2*2.45470891568503e19 -

You should not type

2*2.45470891568503*e19becausee19looks like a variable name. -

You should definitely not type

2*2.45470891568503*e^19because $e$ is being interpreted as 2.718281828 when it appears alone. (Contrastingly, wheneappears in the middle of a number, then it is interpreted as scientific notation.) -

However, you can type instead

2*2.45470891568503*10^19which is fine. This is probably preferred, because it is more human readable. -

When looking at a number, the human reflex is to look at the left-most part, because those are the most significant figures. The right-most part, ordinarily, refers to precision that you don’t usually need. For example, typing

N(sqrt(2))yields1.41421356237310. Honestly, the237310at the end is a level of precision not really required by most applications. -

In stark contrast to this, the numbers

6.02e23and6.02e-23are very, very different numbers. It is important to understand that while6.02and6are «almost the same number» in a certain sense,6.02e23and6.02are not «almost the same number» at all. It is crucial to understand that6.02e23and6.02e-23are not «almost the same thing.» -

You might imagine that very few people might make the mistake which I describe in the previous bullet, but that’s not true in practice. The next entry is a true story.

10$frac{1}{2}$. The tale of the damaged identity matrix

Sometimes, when working with matrix algebra (linear algebra), we might want to perform a check on our computation. We might multiply back two inputs and expect to see an identity matrix.

If you don’t know what «the identity matrix is,» basically it is a square grid of numbers that has exactly the following pattern, but it can be of different sizes. (Here is a $3times 3$ identity matrix, and a $4 times 4$ identity matrix.)

$$

I_3 = left [ begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 0 & 0

0 & 1 & 0

0 & 0 & 1

end{array} right ]

hspace{1in}

I_4 = left [ begin{array}{cccc}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0

0 & 1 & 0 & 0

0 & 0 & 1 & 0

0 & 0 & 0 & 1

end{array} right ]

$$

Once, in the third column of a $4times 4$ identity matrix, we did not see the $0$s we were hoping for. We saw instead something analogous to 1.4572234780951267e-14. Did this mean our calculation was in error? I highlighted one of the values, and asked my class what it meant, when we didn’t get the $0$s in the required spots.

Much to my horror, the class wasn’t able to understand that $1.4572234780951267times 10^{-14}$ is very near to zero. That’s especially true because our original problem had numbers that were between 3 and 107. This «error» is $10^{-15}$ times as much as the original inputs. A good analogy is if you are trying to guess the salary of a computer programmer (roughly $10^5$ dollars), and your guess is off by ten billionths of a penny. Normally, you’d consider such a guess to be very correct.

11. Using currency signs inside of equations

While Sage is an excellent tool for financial mathematics, be certain that you put no dollar signs in front of the numbers. Likewise, you should not put the Euro symbol after any numbers. You should not use any other currency symbols either.

Like any programming language, Sage uses those symbols to perform various tasks.

For example, to find the monthly payment on a 30-year mortgage for a $ 450,000 house with 10% down, and 4% compounded monthly, you should type

find_root( 450000*0.9 == x*(1 - (1 + 0.04/12)^-(12*30))/(0.04/12), 0, 1000000)

which correctly computes the answer: $ 1933.53… is the monthly payment.

You may not put a dollar sign in front of the 450000, nor in front of the 1000000.

Also, note that I did not include the comma inside of 450000 when indicating $ 450,000. (See also the entry «5: Commas in the middle of large numbers» of this list, above.)

For those who have not studied mathematical finance, note that the above code solves the equation

$$ 450000(0.9) = x frac{1 — left (1+frac{0.04}{12} right)^{-(30)(12)}}{frac{0.04}{12}} $$

for $x$ where $ 0 < x < 1,000,000 $. This is a general case of the formula for the present value of a decreasing annuity,

$$ PV = cfrac{1 — (1+r/m)^{-mt}}{r/m} $$

12. Mistakes involving the percent sign

The percent sign has a special meaning in Python, and therefore in Sage. It cannot be used to indicate a numerical percentage. When you wish to use a number like 5% or 7%, you must type 0.05 or 0.07.

For example, if asked «How much should I invest today, at 7% compounded annually, to have $ 25,000 available to me, 10 years from now?», you must not type

find_root( 25000 == x*(1 + 7%)^10, 0, 1000000 )

because that use of the percent sign is illegal. You should type instead,

find_root( 25000 == x*(1 + 0.07)^10, 0, 1000000 )

which gives the correct answer of $ 12,708.73…

An extremely common error, seen frequently, is to use 7 in place of 0.07.

The code

find_root( 25000 == x*(1 + 7)^10, 0, 1000000 )

gives the answer 2.3283064365386963e-05 dollars, which is less than 1/429th of a penny. This answer is completely absurd, but answers like this frequently appear on the quizzes and tests of business administration students.

If you’re curious, the % sign in Python is used to look up entries in a data structure that Python calls «a dictionary,» and for some advanced print statements that carefully control the output formatting.

13. Placing line-breaks where they aren’t permitted

There are times when Python and Sage simply insist that certain spots not contain a line break.

If you are typing code from some printed page, given by an instructor, a collaborator, or from the book Sage for Undergraduates, you might run into another inconsistency. Namely, the width of this printed page, in characters, is vastly smaller than a SageMathCell cell or the screen of CoCalc. Therefore, there are times when one must break the line in print (to make the code fit on the page) but it might not always make sense to do so on the screen.

Here is an example. The following code

y = find_root( x^x == 7, 1, 4 )

print("After searching numerically, for a real number x inside the interval 1 < x < 4, Sage has determined that the solution to x^x=7 is given by ", y)

is legal if typed on two lines: a line beginning with y = find_root(, a blank line, and a line beginning with print("After. However, if you break up that large quote among two or more different lines, then Sage will respond with an error message. Nonetheless, on a printed page, it might be entirely necessary to break up that line, so that the code can fit on the line.

One compromise is to type instead

y = find_root( x^x == 7, 1, 4 )

print "After searching numerically, for",

print "a real number x inside the",

print "interval 1 < x < 4, Sage has",

print "determined that the solution",

print "to x^x=7 is given by ", y

which is equally readable both on screen and in print.

My only word of advice is to experiment, and to be patient as you try various possibilities.

14. Using indentation that Python does not understand

In many of the common programming languages, such as Java, C, C++, Pascal, and so forth, the indentation does not matter at all. While there are style guides, and some instructors enforce those, the compiler isn’t interested in your indentation. However, in Python, the exact opposite is true. The indentation is very important, and it affects how the computer views your code. This can flummox experienced and semi-experienced programmers who come to Python, having learned other languages before.

Consider the following bit of python code, and note the careful indentation.

def newton_method(f, x_old, max_iterate = 10, verbose=False):

"""An implementation of Newton’s Method, to find a

root of f(x) given an initial guess for x. A default of 10

iterations will be carried out unless the optional

parameter max_iterate is set to something else. Set

verbose = True to see all the intermediate stages."""

f_prime(x) = diff( f, x )

for j in range(0, max_iterate):

ratio = f(x_old) / f_prime(x_old)

x_new = x_old - ratio

if (verbose is True):

print "iteration=", j

print "x_old=", x_old

print "f(x)=", f(x_old)

print "f’(x)=", f_prime(x_old)

print "ratio=", ratio

print "x_new=", x_new

print()

x_old = N(x_new)

return x_old

By the way, the above code was taken from Sage for Undergraduates, a book written by Gregory V. Bard and published by The American Mathematical Society in 2015. The pdf-file of that book is available for free, and the print version has an extremely low price. The code above was Figure 6 in Section 5.4.1 (page 250 of the print version).

Here’s how the indentation of the code informs Python of the relationships between the commands.

-

The

printstatements are subordinate to theifstatement, which is subordinate to theforstatement, which is subordinate to thedefstatement. Therefore, they are indented three times. -

The

ifstatement, and the setting of the variablesratio,x_new, andx_oldwith the=sign, are subordinate to theforstatement and thedefstatement, but not theifstatement. The programmer must be careful with the indentation to avoid screwing up that relationship. -

The «docstring» (i.e. the very large comment set off in quotes), the setting of the function

f_prime(x)with the=sign, theforstatement, and thereturnstatement, are only subordinate to thedefstatement. Therefore, they are indented once. -

All the commands above, except the

defstatement itself, are subordinate to thedefstatement but possibly to other statements too. That’s why thedefstatement is the only command that is indented zero times. -

In summary, the indentation shows which commands are subordinate to which other commands. The indentation is absolutely important. It is not a minor detail.

You might find reading all of «Ch 5: Programming in Sage and Python» of the book Sage for Undergraduates to be a useful introduction to Python. That book was written by Gregory V. Bard and published by The American Mathematical Society in 2015. (The pdf-file of that book is available for free, and the print version has an extremely low price.)

15. Missing a colon in Python commands that have subordinate commands

Look at the large block of code in the previous item. Do you see how the def command, the for command, and the if command each have a set of commands subordinate to them?

Whenever a command (such as def, for, or if, but also else) has commands subordinate to it, there must be a colon (:) at the end of that line. This colon isn’t optional, and it helps Python understand the syntax.

While the colon makes the code more human readable, I find that sometimes programmers often forget it.

16. Using braces and brackets as higher-order parentheses

A common question in a «college algebra» class might be to expand something like

$$ -1 + 2xleft (5 — xleft (3 + xleft (2 — xleft (3 + x right )right )right )right ) $$

to get the answer

$$ 2x^5 + 6x^4 — 4x^3 — 6x^2 + 10x — 1 $$

However, older textbooks will write

$$ -1 + 2xleft (5 — xleft {3 + xleft [ 2 — xleft (3 + x right )right ]right }right ) $$

instead of the original, using brackets and braces as higher-order parentheses. It’s been a long time since such usage was common, but often home-schooled students will learn from their parents’ high school algebra textbooks.

In any case, brackets have a specific meaning in Python and therefore, Sage. Brackets indicate lists, and should never be used as higher-order parentheses. Likewise, braces should never be used as higher-ordered parentheses. (If you are curious, braces in Python are used to program a data structure that maps one value to another, which Python calls «a dictionary.»)

The correct way to code

$$ -1 + 2xleft (5 — xleft (3 + xleft (2 — xleft (3 + x right )right )right )right ) $$

is with

-1 + 2*x*(5 - x*(3 + x*(2 - x*(3 + x ))))

and for completeness, the correct way to code

$$ 2x^5 + 6x^4 — 4x^3 — 6x^2 + 10x — 1 $$

is with

2*x^5 + 6*x^4 - 4*x^3 - 6*x^2 + 10*x - 1

Didn’t find what you needed?

Remember: if you don’t find what you need, or if you’d like to ask a question, then please email help@sagemath.com at any time. We’d love to hear from you! Please include a link (the URL address in your browser) to any relevant project or document, as part of your email.

The 4 most common syntax mistakes encountered by users are:

-

Copy-Paste (symbols like μ) from text/pdf/websites. You can only copy-paste LaTeX-code (e.g. mu), otherwise your answer can’t be interpreted.

-

Incomplete math: for example a fraction without numerator and/or denominator, or a function without argument.

-

«to the Power» twice: having two «to the Power» (i.e. ^ in LaTeX) in a row without an argument in between (e.g. the syntax of x^^2 is wrong).

-

Correct LaTeX: make sure you use the math insert menu or type LaTeX directly to create proper syntax.

If you insert an answer with incorrect syntax, you will get a warning about this. In case this happens this will not count as an attempt and thus you won’t lose points.

To read in more detail about syntax in Grasple, see the sections below.

Answers and feedback

Grasple’s answer box is also a calculator, so the answer 1 will also be accepted as 8/8, cos(0) or √1. When your answer is correct, you will see a green box.

When you answer incorrectly, you can retry. After three retries, you will be shown the correct answer, often accompanied by an explanation of how to solve your question. For questions with multiple sub questions, the explanation will generally be shown after the final sub question has been tried.

Syntax

You can either use the drop down menu above the answer box to find symbols (e.g. √), or you can type LaTeX directly followed by a space (e.g. sqrt followed by space for √). There are three letters that have special use in Grasple:

The letter capital I is used to denote the imaginary number (e.g. √−1=I).

The letter e is used to denote Euler’s number (e.g. ln(e)=1).

The letter π is used to denote pi (e.g. cos(π)=−1).

Use a period . to indicate a decimal point (e.g. 3.14).

Finally, when writing fractions, do not use the mixed fraction notation to simplify the fraction. Meaning that if you want to write 1.5, write it as 3/2 instead of 1 1/2, as 1 1/2 will be read as 1·1/2=1/2.

Warning: copy-paste from text

Do not copy-paste symbols from the exercises, text or other resources. Probably the symbols won’t be recognized and thus your answer will be marked as incorrect. To fill in an answer use LaTeX or the buttons in the menu around the answer box.

Linear Algebra specific

For linear algebra questions all the above holds, but there are some additional functionalities which will be explained in the next section.

Vector and Matrix

To insert a matrix or a vector, use the menu at the bottom right of the answer box. The size of the matrix you indicate by selecting a number of squares depicts the size of the matrix. See an example below:

Fractions and numeric values

Always give exact values as entries within a matrix or vector. So, do not type 0.3333 but type 1/3. Other examples:

-

Do not type 1.4142, but use √2

-

Do not type 3.14, but use π

Exercises with Basis as answer

Some exercises require you to give a basis. When you get to those exercises, you can give a basis by enclosing a list of vectors, separated by comma’s ( , ), between curly brackets: { }. See an example below:

Do you have questions or feedback about the syntax? Ask us via the chat in the bottom right corner!

Introduction

Math and arithmetic operations are essential in Bash scripting. Various automation tasks require basic arithmetic operations, such as converting the CPU temperature to Fahrenheit. Implementing math operations in Bash is simple and very easy to learn.

This guide teaches you how to do basic math in Bash in various ways.

Prerequisites

- Access to the command line/terminal.

- A text editor to code examples, such as nano or Vi/Vim.

- Basic knowledge of Bash scripting.

Why Do You Need Math in Bash Scripting?

Although math is not the primary purpose of Bash scripting, knowing how to do essential calculations is helpful for various use cases.

Common use cases include:

- Adding/subtracting/multiplying/dividing numbers.

- Rounding numbers.

- Incrementing and decrementing numbers.

- Converting units.

- Floating-point calculations.

- Finding percentages.

- Working with different number bases (binary, octal, or hexadecimal).

Depending on the automation task, basic math and arithmetic in Bash scripting help perform a quick calculation, yielding immediate results in the desired format.

Bash Math Commands and Methods

Some Linux commands allow performing basic and advanced calculations immediately. This section shows basic math examples with each method.

Arithmetic Expansion

The preferable way to do math in Bash is to use shell arithmetic expansion. The built-in capability evaluates math expressions and returns the result. The syntax for arithmetic expansions is:

$((expression))The syntax consists of:

- Compound notation

(())which evaluates the expression. - The variable operator

$to store the result.

Note: The square bracket notation ( $[expression] ) also evaluates an arithmetic expression, and should be avoided since it is deprecated.

For example, add two numbers and echo the result:

echo $((2+3))

The arithmetic expansion notation is the preferred method when working with Bash scripts. The notation is often seen together with if statements and for loops in Bash.

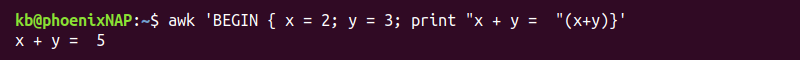

awk Command

The awk command acts as a selector for pattern expressions. For example, to perform addition using the awk command, use the following example statement:

awk 'BEGIN { x = 2; y = 3; print "x + y = "(x+y) }'

For variables x = 2 and y = 3, the output prints x + y = 5 to the console.

bc Command

The bc command (short for basic calculator) is a command-line utility that renders the bc language. The program runs as an interactive program or takes standard input to perform arbitrary precision arithmetic.

Pipe an equation from standard input into the command to fetch results. For example:

echo "2+3" | bc

The output prints the calculation result.

dc Command

The dc command (short for desk calculator) is a calculator utility that supports reverse Polish notation. The program takes standard input and supports unlimited precision arithmetic.

Pipe a standard input equation into the command to fetch the result. For example:

echo "2 3 + p" | dc

The p in the equation sends the print signal to the dc command.

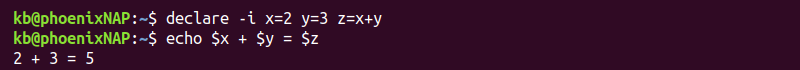

declare Command

The Bash declare command allows integer calculations. To use declare for calculations, add the -i option. For example:

declare -i x=2 y=3 z=x+yEcho each variable to see the results:

echo $x + $y = $z

The output prints each variable to the console.

expr Command

The expr command is a legacy command line utility for evaluating integer arithmetic. An example expr command looks like the following:

expr 2 + 3

Separate numbers and the operation sign with spaces and run the command to see the calculation result.

factor Command

The factor command is a command-line utility that prints the factors for any positive integer, and the result factorizes into prime numbers.

For example, to print the factors of the number 100, run:

factor 100

The output prints the factored number.

let Command

The Bash let command performs various arithmetic, bitwise and logical operations. The built-in command works only with integers. The following example demonstrates the let command syntax:

let x=2+3 | echo $x

The output prints the results.

test Command

The test command in Linux evaluates conditional expressions and often pairs with the Bash if statement. There are two variations for the test syntax:

test 2 -gt 3; echo $?

Or alternatively:

[ 2 -gt 3 ]; echo $?

The test command evaluates whether two is greater than (-gt) three. If the expression is true, the output is zero (0), or one (1) if false.

Bash Arithmetic Operators

Bash offers a wide range of arithmetic operators for various calculations and evaluations. The operators work with the let, declare, and arithmetic expansion.

Below is a quick reference table that describes Bash arithmetic operators and their functionality.

| Syntax | Description |

|---|---|

++x, x++ |

Pre and post-increment. |

--x, x-- |

Pre and post-decrement. |

+, -, *, / |

Addition, subtraction, multiplication, division. |

%, ** (or ^) |

Modulo (remainder) and exponentiation. |

&&, ||, ! |

Logical AND, OR, and negation. |

&, |, ^, ~ |

Bitwise AND, OR, XOR, and negation. |

<=, <, >, => |

Less than or equal to, less than, greater than, and greater than or equal to comparison operators. |

==, != |

Equality and inequality comparison operators. |

= |

Assignment operator. Combines with other arithmetic operators. |

How to Do Math in Bash

Bash offers different ways to perform math calculations depending on the type of problem.

Below are examples of some common problems which use Bash math functionalities or commands as a solution. Most examples use the Bash arithmetic expansion notation. The section also covers common Bash math errors and how to resolve them.

Math with Integers

The arithmetic expansion notation is the simplest to use and manipulate with when working with integers. For example, create an expression with variables and calculate the result immediately:

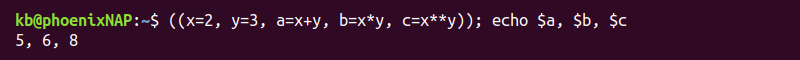

echo $((x=2, y=3, x+y))

To evaluate multiple expressions, use compound notation, store each calculation in a variable, and echo the result. For example:

((x=2, y=3, a=x+y, b=x*y, c=x**y)); echo $a, $b, $c

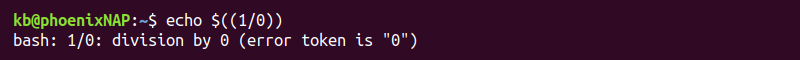

When trying to divide, keep the following in mind:

1. Division by zero (0) is impossible and throws an error.

2. Bash arithmetic expansion does not support floating-point arithmetic. When attempting to divide in this case, the output shows zero (0).

The result of integer division must be an integer.

Incrementing and Decrementing

Bash arithmetic expansion uses C-style integer incrementing and decrementing. The operator for incrementing or decrementing is either before or after the variable, yielding different behavior.

If the operator is before the variable (++x or --x), the increment or decrement happens before value assignment. To see how pre-incrementing works, run the following lines:

number=1echo $((++number))

The variable increments, and the new value is immediately available.

If the operator is after the variable (x++ or x--), the increment or decrement happens after value assignment. To see how post-incrementing works, run the following:

number=1echo $((number++))echo $number

The variable stays the same and increments in the following use.

Floating-point Arithmetic

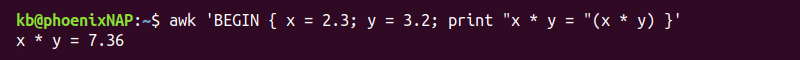

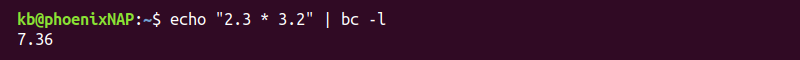

Although Bash arithmetic expansion does not support floating-point arithmetic, there are other ways to perform such calculations. Below are four examples using commands or programming languages available on most Linux systems.

1. Using awk for up to 6 decimal places:

awk 'BEGIN { x = 2.3; y = 3.2; print "x * y = "(x * y) }'

2. Using bc with the -l flag for up to 20 decimal places:

echo "2.3 * 3.2" | bc -l

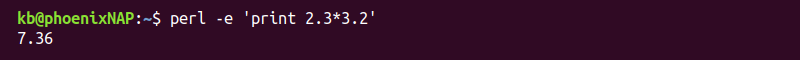

3. Using Perl for up to 20 decimal places:

perl -e 'print 2.3*3.2'

Perl often comes preinstalled in Linux systems.

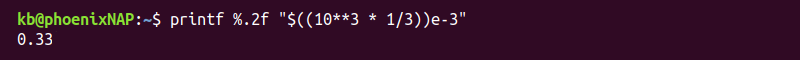

4. Using printf and arithmetic expansion to convert a fraction to a decimal:

printf %.<precision>f "$((10**<multiplier> * <fraction>))e-<multiplier>"Precision dictates how many decimal places, whereas the multiplier is a power of ten. The number should be lower than the multiplier. Otherwise, the formula puts trailing zeros in the result.

For example, convert 1/3 to a decimal with precision two:

printf %.2f "$((10**3 * 1/3))e-3"

Avoid this method for precise calculations and use it only for a small number of decimal places.

Calculating a Percentage and Rounding

Below are two ways to calculate a percentage in Bash.

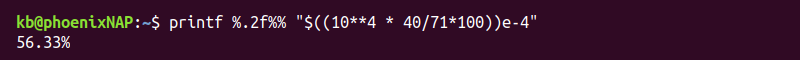

1. Use printf with arithmetic expansion.

printf %.2f "$((10**4 * part/total))e-4"%For example, calculate what percent 40 is from 71:

printf %.2f%% "$((10**4 * 40/71))e-4"%

The precision is limited to two decimal places, and the answer always rounds down.

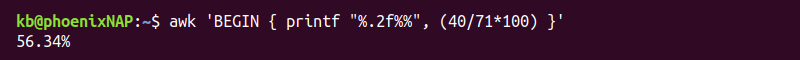

2. Use awk with printf for better precision:

awk 'BEGIN { printf "%.2f%%", (part/total*100) }'For instance, calculate how many percent is 40 from 71 with:

awk 'BEGIN { printf "%.2f%%", (40/71*100) }'

The answer rounds up if the third decimal place is higher than five, providing better accuracy.

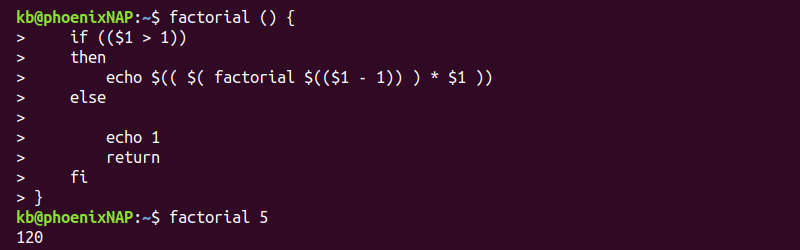

Finding a Factorial in the Shell

To calculate a factorial for any number, use a recursive Bash function.

For small numbers, Bash arithmetic expansion works well:

factorial () {

if (($1 > 1))

then

echo $(( $( factorial $(($1 - 1)) ) * $1 ))

else

echo 1

return

fi

}To check the factorial for a number, use the following syntax:

factorial 5

The method is slow and has limited precision (up to factorial 20).

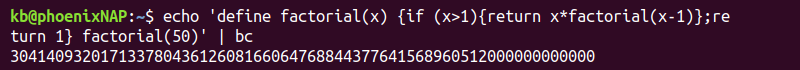

For higher precision, faster results, and larger numbers, use the bc command. For example:

echo 'define factorial(x) {if (x>1){return x*factorial(x-1)};return 1}

factorial(<number>)' | bcReplace <number> with the factorial number to calculate. For example, to find the factorial of 50, use:

echo 'define factorial(x) {if (x>1){return x*factorial(x-1)};return 1} factorial(50)' | bc

The output prints the calculation result to the terminal.

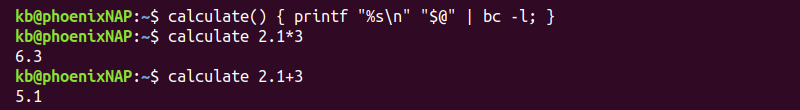

Creating a Bash Calculator Function

Create a simple Bash calculator function with the following code:

calculate() { printf "%sn" "[email protected]" | bc -l; }

The function takes user input and pipes the equation into the bc command.

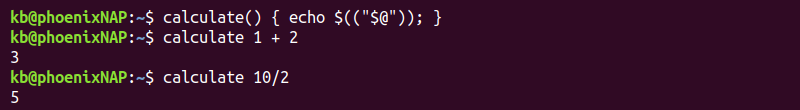

Alternatively, to avoid using programs, use Bash arithmetic expansion in a function:

calculate() { echo $(("[email protected]")); }

Keep the arithmetic expansion limitations in mind. Floating-point arithmetic is not available with this function.

Save the function into the .bashrc file to always have the function available in the shell.

Using Different Arithmetic Bases

By default, Bash arithmetic expansion uses base ten numbers. To change the number base, use the following format:

base#numberWhere base is any integer between two and 64.

For example, to do a binary (base 2) calculation, use:

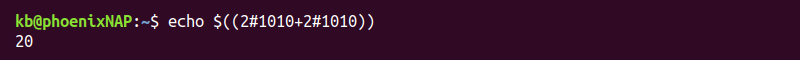

echo $((2#1010+2#1010))

Octal (base

echo $((010+010))

Hexadecimal (base 16) calculations allow using 0x as a base prefix. For example:

echo $((0xA+0xA))

The output prints the result in base ten for any calculation.

Convert Units

Create a simple Bash script to convert units:

1. Open a text editor, such as Vim, and create a convert.sh script. For example:

vim convert.sh2. Paste the following code:

#!/bin/bash

## Program for feet and inches conversion

echo "Enter a number to be converted:"

read number

echo $number feet to inches:

echo "$number*12" | bc -l

echo $number inches to feet:

echo "$number/12" | bc -lThe program uses Bash read to take user input and calculates the conversion from feet to inches and from inches to feet.

3. Save the script and close:

:wq4. Run the Bash script with:

. convert.sh

Enter a number and see the result. For different conversions, use appropriate conversion formulas.

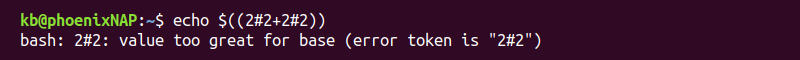

Solving «bash error: value too great for base»

When working with different number bases, stay within the number base limits. For example, binary numbers use 0 and 1 to define numbers:

echo $((2#2+2#2))Attempting to use 2#2 as a number outputs an error:

bash: 2#2: value too great for base (error token is "2#2")

The number is not the correct format for binary use. To resolve the error, convert the number to binary to perform the calculation correctly:

echo $((2#10+2#10))The binary number 10 is 2 in base ten.

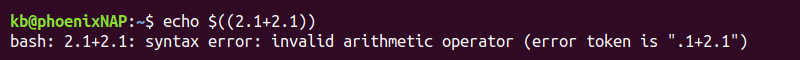

Solving «syntax error: invalid arithmetic operator»

The Bash arithmetic expansion notation only works for integer calculations. Attempt to add two floating-point numbers, for example:

echo $((2.1+2.1))The command prints an error:

bash: 2.1+2.1: syntax error: invalid arithmetic operator (error token is ".1+2.1")

To resolve the error, use regular integer arithmetic or a different method to calculate the equation.

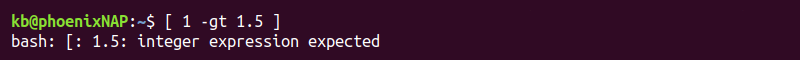

Solving «bash error: integer expression expected»

When comparing two numbers, the test command requires integers. For example, try the following command:

[ 1 -gt 1.5 ]The output prints an error:

bash: [: 1.5: integer expression expected

Resolve the error by comparing integer values.

Conclusion

You know how to do Bash arithmetic and various calculations through Bash scripting.

For more advanced scientific calculations, use Python together with SciPy, NumPy, and other libraries.

Ситуация: программист взял в работу математический проект — ему нужно написать код, который будет считать функции и выводить результаты. В задании написано:

«Пусть у нас есть функция f(x,y) = xy, которая перемножает два аргумента и возвращает полученное значение».

Программист садится и пишет код:

a = 10

b = 15

result = 0

def fun(x,y):

return x y

result = fun(a,b)

print(result)Но при выполнении такого кода компьютер выдаёт ошибку:

File "main.py", line 13

result = x y

^

❌ SyntaxError: invalid syntax

Почему так происходит: в каждом языке программирования есть свой синтаксис — правила написания и оформления команд. В Python тоже есть свой синтаксис, по которому для умножения нельзя просто поставить рядом две переменных, как в математике. Интерпретатор находит первую переменную и думает, что ему сейчас объяснят, что с ней делать. Но вместо этого он сразу находит вторую переменную. Интерпретатор не знает, как именно нужно их обработать, потому что у него нет правила «Если две переменные стоят рядом, их нужно перемножить». Поэтому интерпретатор останавливается и говорит, что у него лапки.

Что делать с ошибкой SyntaxError: invalid syntax

В нашем случае достаточно поставить звёздочку (знак умножения в Python) между переменными — это оператор умножения, который Python знает:

a = 10

b = 15

result = 0

def fun(x,y):

return x * y

result = fun(a,b)

print(result)В общем случае найти источник ошибки SyntaxError: invalid syntax можно так:

- Проверьте, не идут ли у вас две команды на одной строке друг за другом.

- Найдите в справочнике описание команды, которую вы хотите выполнить. Возможно, где-то опечатка.

- Проверьте, не пропущена ли команда на месте ошибки.

Практика

Попробуйте найти ошибки в этих фрагментах кода:

x = 10 y = 15

def fun(x,y):

return x * ytry:

a = 100

b = "PythonRu"

assert a = b

except AssertionError:

print("Исключение AssertionError.")

else:

print("Успех, нет ошибок!")Вёрстка:

Кирилл Климентьев

Обработка ошибок увеличивает отказоустойчивость кода, защищая его от потенциальных сбоев, которые могут привести к преждевременному завершению работы.

Прежде чем переходить к обсуждению того, почему обработка исключений так важна, и рассматривать встроенные в Python исключения, важно понять, что есть тонкая грань между понятиями ошибки и исключения.

Ошибку нельзя обработать, а исключения Python обрабатываются при выполнении программы. Ошибка может быть синтаксической, но существует и много видов исключений, которые возникают при выполнении и не останавливают программу сразу же. Ошибка может указывать на критические проблемы, которые приложение и не должно перехватывать, а исключения — состояния, которые стоит попробовать перехватить. Ошибки — вид непроверяемых и невозвратимых ошибок, таких как OutOfMemoryError, которые не стоит пытаться обработать.

Обработка исключений делает код более отказоустойчивым и помогает предотвращать потенциальные проблемы, которые могут привести к преждевременной остановке выполнения. Представьте код, который готов к развертыванию, но все равно прекращает работу из-за исключения. Клиент такой не примет, поэтому стоит заранее обработать конкретные исключения, чтобы избежать неразберихи.

Ошибки могут быть разных видов:

- Синтаксические

- Недостаточно памяти

- Ошибки рекурсии

- Исключения

Разберем их по очереди.

Синтаксические ошибки (SyntaxError)

Синтаксические ошибки часто называют ошибками разбора. Они возникают, когда интерпретатор обнаруживает синтаксическую проблему в коде.

Рассмотрим на примере.

a = 8

b = 10

c = a b

File "", line 3

c = a b

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

Стрелка вверху указывает на место, где интерпретатор получил ошибку при попытке исполнения. Знак перед стрелкой указывает на причину проблемы. Для устранения таких фундаментальных ошибок Python будет делать большую часть работы за программиста, выводя название файла и номер строки, где была обнаружена ошибка.

Недостаточно памяти (OutofMemoryError)

Ошибки памяти чаще всего связаны с оперативной памятью компьютера и относятся к структуре данных под названием “Куча” (heap). Если есть крупные объекты (или) ссылки на подобные, то с большой долей вероятности возникнет ошибка OutofMemory. Она может появиться по нескольким причинам:

- Использование 32-битной архитектуры Python (максимальный объем выделенной памяти невысокий, между 2 и 4 ГБ);

- Загрузка файла большого размера;

- Запуск модели машинного обучения/глубокого обучения и много другое;

Обработать ошибку памяти можно с помощью обработки исключений — резервного исключения. Оно используется, когда у интерпретатора заканчивается память и он должен немедленно остановить текущее исполнение. В редких случаях Python вызывает OutofMemoryError, позволяя скрипту каким-то образом перехватить самого себя, остановить ошибку памяти и восстановиться.

Но поскольку Python использует архитектуру управления памятью из языка C (функция malloc()), не факт, что все процессы восстановятся — в некоторых случаях MemoryError приведет к остановке. Следовательно, обрабатывать такие ошибки не рекомендуется, и это не считается хорошей практикой.

Ошибка рекурсии (RecursionError)

Эта ошибка связана со стеком и происходит при вызове функций. Как и предполагает название, ошибка рекурсии возникает, когда внутри друг друга исполняется много методов (один из которых — с бесконечной рекурсией), но это ограничено размером стека.

Все локальные переменные и методы размещаются в стеке. Для каждого вызова метода создается стековый кадр (фрейм), внутрь которого помещаются данные переменной или результат вызова метода. Когда исполнение метода завершается, его элемент удаляется.

Чтобы воспроизвести эту ошибку, определим функцию recursion, которая будет рекурсивной — вызывать сама себя в бесконечном цикле. В результате появится ошибка StackOverflow или ошибка рекурсии, потому что стековый кадр будет заполняться данными метода из каждого вызова, но они не будут освобождаться.

def recursion():

return recursion()

recursion()

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

RecursionError Traceback (most recent call last)

in

----> 1 recursion()

in recursion()

1 def recursion():

----> 2 return recursion()

... last 1 frames repeated, from the frame below ...

in recursion()

1 def recursion():

----> 2 return recursion()

RecursionError: maximum recursion depth exceeded

Ошибка отступа (IndentationError)

Эта ошибка похожа по духу на синтаксическую и является ее подвидом. Тем не менее она возникает только в случае проблем с отступами.

Пример:

for i in range(10):

print('Привет Мир!')

File "", line 2

print('Привет Мир!')

^

IndentationError: expected an indented block

Исключения

Даже если синтаксис в инструкции или само выражение верны, они все равно могут вызывать ошибки при исполнении. Исключения Python — это ошибки, обнаруживаемые при исполнении, но не являющиеся критическими. Скоро вы узнаете, как справляться с ними в программах Python. Объект исключения создается при вызове исключения Python. Если скрипт не обрабатывает исключение явно, программа будет остановлена принудительно.

Программы обычно не обрабатывают исключения, что приводит к подобным сообщениям об ошибке:

Ошибка типа (TypeError)

a = 2

b = 'PythonRu'

a + b

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

in

1 a = 2

2 b = 'PythonRu'

----> 3 a + b

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str'

Ошибка деления на ноль (ZeroDivisionError)

10 / 0

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ZeroDivisionError Traceback (most recent call last)

in

----> 1 10 / 0

ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

Есть разные типы исключений в Python и их тип выводится в сообщении: вверху примеры TypeError и ZeroDivisionError. Обе строки в сообщениях об ошибке представляют собой имена встроенных исключений Python.

Оставшаяся часть строки с ошибкой предлагает подробности о причине ошибки на основе ее типа.

Теперь рассмотрим встроенные исключения Python.

Встроенные исключения

BaseException

+-- SystemExit

+-- KeyboardInterrupt

+-- GeneratorExit

+-- Exception

+-- StopIteration

+-- StopAsyncIteration

+-- ArithmeticError

| +-- FloatingPointError

| +-- OverflowError

| +-- ZeroDivisionError

+-- AssertionError

+-- AttributeError

+-- BufferError

+-- EOFError

+-- ImportError

| +-- ModuleNotFoundError

+-- LookupError

| +-- IndexError

| +-- KeyError

+-- MemoryError

+-- NameError

| +-- UnboundLocalError

+-- OSError

| +-- BlockingIOError

| +-- ChildProcessError

| +-- ConnectionError

| | +-- BrokenPipeError

| | +-- ConnectionAbortedError

| | +-- ConnectionRefusedError

| | +-- ConnectionResetError

| +-- FileExistsError

| +-- FileNotFoundError

| +-- InterruptedError

| +-- IsADirectoryError

| +-- NotADirectoryError

| +-- PermissionError

| +-- ProcessLookupError

| +-- TimeoutError

+-- ReferenceError

+-- RuntimeError

| +-- NotImplementedError

| +-- RecursionError

+-- SyntaxError

| +-- IndentationError

| +-- TabError

+-- SystemError

+-- TypeError

+-- ValueError

| +-- UnicodeError

| +-- UnicodeDecodeError

| +-- UnicodeEncodeError

| +-- UnicodeTranslateError

+-- Warning

+-- DeprecationWarning

+-- PendingDeprecationWarning

+-- RuntimeWarning

+-- SyntaxWarning

+-- UserWarning

+-- FutureWarning

+-- ImportWarning

+-- UnicodeWarning

+-- BytesWarning

+-- ResourceWarning

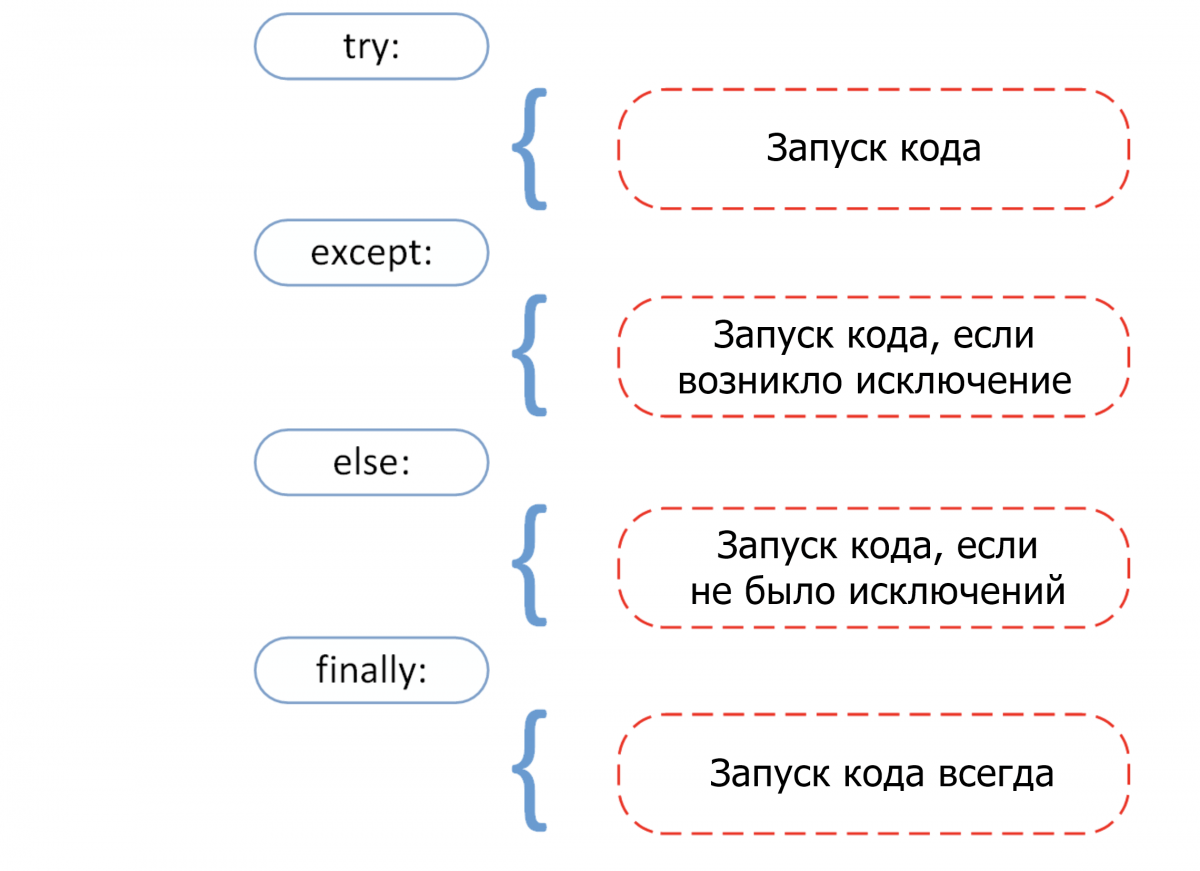

Прежде чем переходить к разбору встроенных исключений быстро вспомним 4 основных компонента обработки исключения, как показано на этой схеме.

Try: он запускает блок кода, в котором ожидается ошибка.Except: здесь определяется тип исключения, который ожидается в блокеtry(встроенный или созданный).Else: если исключений нет, тогда исполняется этот блок (его можно воспринимать как средство для запуска кода в том случае, если ожидается, что часть кода приведет к исключению).Finally: вне зависимости от того, будет ли исключение или нет, этот блок кода исполняется всегда.

В следующем разделе руководства больше узнаете об общих типах исключений и научитесь обрабатывать их с помощью инструмента обработки исключения.

Ошибка прерывания с клавиатуры (KeyboardInterrupt)

Исключение KeyboardInterrupt вызывается при попытке остановить программу с помощью сочетания Ctrl + C или Ctrl + Z в командной строке или ядре в Jupyter Notebook. Иногда это происходит неумышленно и подобная обработка поможет избежать подобных ситуаций.

В примере ниже если запустить ячейку и прервать ядро, программа вызовет исключение KeyboardInterrupt. Теперь обработаем исключение KeyboardInterrupt.

try:

inp = input()

print('Нажмите Ctrl+C и прервите Kernel:')

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print('Исключение KeyboardInterrupt')

else:

print('Исключений не произошло')

Исключение KeyboardInterrupt

Стандартные ошибки (StandardError)

Рассмотрим некоторые базовые ошибки в программировании.

Арифметические ошибки (ArithmeticError)

- Ошибка деления на ноль (Zero Division);

- Ошибка переполнения (OverFlow);

- Ошибка плавающей точки (Floating Point);

Все перечисленные выше исключения относятся к классу Arithmetic и вызываются при ошибках в арифметических операциях.

Деление на ноль (ZeroDivisionError)

Когда делитель (второй аргумент операции деления) или знаменатель равны нулю, тогда результатом будет ошибка деления на ноль.

try:

a = 100 / 0

print(a)

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("Исключение ZeroDivisionError." )

else:

print("Успех, нет ошибок!")

Исключение ZeroDivisionError.

Переполнение (OverflowError)

Ошибка переполнение вызывается, когда результат операции выходил за пределы диапазона. Она характерна для целых чисел вне диапазона.

try:

import math

print(math.exp(1000))

except OverflowError:

print("Исключение OverFlow.")

else:

print("Успех, нет ошибок!")

Исключение OverFlow.

Ошибка утверждения (AssertionError)

Когда инструкция утверждения не верна, вызывается ошибка утверждения.

Рассмотрим пример. Предположим, есть две переменные: a и b. Их нужно сравнить. Чтобы проверить, равны ли они, необходимо использовать ключевое слово assert, что приведет к вызову исключения Assertion в том случае, если выражение будет ложным.

try:

a = 100

b = "PythonRu"

assert a == b

except AssertionError:

print("Исключение AssertionError.")

else:

print("Успех, нет ошибок!")

Исключение AssertionError.

Ошибка атрибута (AttributeError)

При попытке сослаться на несуществующий атрибут программа вернет ошибку атрибута. В следующем примере можно увидеть, что у объекта класса Attributes нет атрибута с именем attribute.

class Attributes(obj):

a = 2

print(a)

try:

obj = Attributes()

print(obj.attribute)

except AttributeError:

print("Исключение AttributeError.")

2

Исключение AttributeError.

Ошибка импорта (ModuleNotFoundError)

Ошибка импорта вызывается при попытке импортировать несуществующий (или неспособный загрузиться) модуль в стандартном пути или даже при допущенной ошибке в имени.

import nibabel

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ModuleNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

in

----> 1 import nibabel

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'nibabel'

Ошибка поиска (LookupError)

LockupError выступает базовым классом для исключений, которые происходят, когда key или index используются для связывания или последовательность списка/словаря неверна или не существует.

Здесь есть два вида исключений:

- Ошибка индекса (

IndexError); - Ошибка ключа (

KeyError);

Ошибка ключа

Если ключа, к которому нужно получить доступ, не оказывается в словаре, вызывается исключение KeyError.

try:

a = {1:'a', 2:'b', 3:'c'}

print(a[4])

except LookupError:

print("Исключение KeyError.")

else:

print("Успех, нет ошибок!")

Исключение KeyError.

Ошибка индекса

Если пытаться получить доступ к индексу (последовательности) списка, которого не существует в этом списке или находится вне его диапазона, будет вызвана ошибка индекса (IndexError: list index out of range python).

try:

a = ['a', 'b', 'c']

print(a[4])

except LookupError:

print("Исключение IndexError, индекс списка вне диапазона.")

else:

print("Успех, нет ошибок!")

Исключение IndexError, индекс списка вне диапазона.

Ошибка памяти (MemoryError)

Как уже упоминалось, ошибка памяти вызывается, когда операции не хватает памяти для выполнения.

Ошибка имени (NameError)

Ошибка имени возникает, когда локальное или глобальное имя не находится.

В следующем примере переменная ans не определена. Результатом будет ошибка NameError.

try:

print(ans)

except NameError:

print("NameError: переменная 'ans' не определена")

else:

print("Успех, нет ошибок!")

NameError: переменная 'ans' не определена

Ошибка выполнения (Runtime Error)

Ошибка «NotImplementedError»

Ошибка выполнения служит базовым классом для ошибки NotImplemented. Абстрактные методы определенного пользователем класса вызывают это исключение, когда производные методы перезаписывают оригинальный.

class BaseClass(object):

"""Опередляем класс"""

def __init__(self):

super(BaseClass, self).__init__()

def do_something(self):

# функция ничего не делает

raise NotImplementedError(self.__class__.__name__ + '.do_something')

class SubClass(BaseClass):

"""Реализует функцию"""

def do_something(self):

# действительно что-то делает

print(self.__class__.__name__ + ' что-то делает!')

SubClass().do_something()

BaseClass().do_something()

SubClass что-то делает!

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NotImplementedError Traceback (most recent call last)

in

14

15 SubClass().do_something()

---> 16 BaseClass().do_something()

in do_something(self)

5 def do_something(self):

6 # функция ничего не делает

----> 7 raise NotImplementedError(self.__class__.__name__ + '.do_something')

8

9 class SubClass(BaseClass):

NotImplementedError: BaseClass.do_something

Ошибка типа (TypeError)

Ошибка типа вызывается при попытке объединить два несовместимых операнда или объекта.

В примере ниже целое число пытаются добавить к строке, что приводит к ошибке типа.

try:

a = 5

b = "PythonRu"

c = a + b

except TypeError:

print('Исключение TypeError')

else:

print('Успех, нет ошибок!')

Исключение TypeError

Ошибка значения (ValueError)

Ошибка значения вызывается, когда встроенная операция или функция получают аргумент с корректным типом, но недопустимым значением.

В этом примере встроенная операция float получат аргумент, представляющий собой последовательность символов (значение), что является недопустимым значением для типа: число с плавающей точкой.

try:

print(float('PythonRu'))

except ValueError:

print('ValueError: не удалось преобразовать строку в float: 'PythonRu'')

else:

print('Успех, нет ошибок!')

ValueError: не удалось преобразовать строку в float: 'PythonRu'

Пользовательские исключения в Python

В Python есть много встроенных исключений для использования в программе. Но иногда нужно создавать собственные со своими сообщениями для конкретных целей.

Это можно сделать, создав новый класс, который будет наследовать из класса Exception в Python.

class UnAcceptedValueError(Exception):

def __init__(self, data):

self.data = data

def __str__(self):

return repr(self.data)

Total_Marks = int(input("Введите общее количество баллов: "))

try:

Num_of_Sections = int(input("Введите количество разделов: "))

if(Num_of_Sections < 1):

raise UnAcceptedValueError("Количество секций не может быть меньше 1")

except UnAcceptedValueError as e:

print("Полученная ошибка:", e.data)

Введите общее количество баллов: 10

Введите количество разделов: 0

Полученная ошибка: Количество секций не может быть меньше 1

В предыдущем примере если ввести что-либо меньше 1, будет вызвано исключение. Многие стандартные исключения имеют собственные исключения, которые вызываются при возникновении проблем в работе их функций.

Недостатки обработки исключений в Python

У использования исключений есть свои побочные эффекты, как, например, то, что программы с блоками try-except работают медленнее, а количество кода возрастает.

Дальше пример, где модуль Python timeit используется для проверки времени исполнения 2 разных инструкций. В stmt1 для обработки ZeroDivisionError используется try-except, а в stmt2 — if. Затем они выполняются 10000 раз с переменной a=0. Суть в том, чтобы показать разницу во времени исполнения инструкций. Так, stmt1 с обработкой исключений занимает больше времени чем stmt2, который просто проверяет значение и не делает ничего, если условие не выполнено.

Поэтому стоит ограничить использование обработки исключений в Python и применять его в редких случаях. Например, когда вы не уверены, что будет вводом: целое или число с плавающей точкой, или не уверены, существует ли файл, который нужно открыть.

import timeit

setup="a=0"

stmt1 = '''

try:

b=10/a

except ZeroDivisionError:

pass'''

stmt2 = '''

if a!=0:

b=10/a'''

print("time=",timeit.timeit(stmt1,setup,number=10000))

print("time=",timeit.timeit(stmt2,setup,number=10000))

time= 0.003897680000136461

time= 0.0002797570000439009

Выводы!

Как вы могли увидеть, обработка исключений помогает прервать типичный поток программы с помощью специального механизма, который делает код более отказоустойчивым.

Обработка исключений — один из основных факторов, который делает код готовым к развертыванию. Это простая концепция, построенная всего на 4 блоках: try выискивает исключения, а except их обрабатывает.

Очень важно поупражняться в их использовании, чтобы сделать свой код более отказоустойчивым.