Common issues and solutions

This section has examples of cases when you need to update your code

to use static typing, and ideas for working around issues if mypy

doesn’t work as expected. Statically typed code is often identical to

normal Python code (except for type annotations), but sometimes you need

to do things slightly differently.

No errors reported for obviously wrong code

There are several common reasons why obviously wrong code is not

flagged as an error.

The function containing the error is not annotated.

Functions that

do not have any annotations (neither for any argument nor for the

return type) are not type-checked, and even the most blatant type

errors (e.g. 2 + 'a') pass silently. The solution is to add

annotations. Where that isn’t possible, functions without annotations

can be checked using :option:`—check-untyped-defs <mypy —check-untyped-defs>`.

Example:

def foo(a): return '(' + a.split() + ')' # No error!

This gives no error even though a.split() is «obviously» a list

(the author probably meant a.strip()). The error is reported

once you add annotations:

def foo(a: str) -> str: return '(' + a.split() + ')' # error: Unsupported operand types for + ("str" and List[str])

If you don’t know what types to add, you can use Any, but beware:

One of the values involved has type ‘Any’.

Extending the above

example, if we were to leave out the annotation for a, we’d get

no error:

def foo(a) -> str: return '(' + a.split() + ')' # No error!

The reason is that if the type of a is unknown, the type of

a.split() is also unknown, so it is inferred as having type

Any, and it is no error to add a string to an Any.

If you’re having trouble debugging such situations,

:ref:`reveal_type() <reveal-type>` might come in handy.

Note that sometimes library stubs with imprecise type information

can be a source of Any values.

:py:meth:`__init__ <object.__init__>` method has no annotated

arguments and no return type annotation.

This is basically a combination of the two cases above, in that __init__

without annotations can cause Any types leak into instance variables:

class Bad: def __init__(self): self.value = "asdf" 1 + "asdf" # No error! bad = Bad() bad.value + 1 # No error! reveal_type(bad) # Revealed type is "__main__.Bad" reveal_type(bad.value) # Revealed type is "Any" class Good: def __init__(self) -> None: # Explicitly return None self.value = value

Some imports may be silently ignored.

A common source of unexpected Any values is the

:option:`—ignore-missing-imports <mypy —ignore-missing-imports>` flag.

When you use :option:`—ignore-missing-imports <mypy —ignore-missing-imports>`,

any imported module that cannot be found is silently replaced with Any.

To help debug this, simply leave out

:option:`—ignore-missing-imports <mypy —ignore-missing-imports>`.

As mentioned in :ref:`fix-missing-imports`, setting ignore_missing_imports=True

on a per-module basis will make bad surprises less likely and is highly encouraged.

Use of the :option:`—follow-imports=skip <mypy —follow-imports>` flags can also

cause problems. Use of these flags is strongly discouraged and only required in

relatively niche situations. See :ref:`follow-imports` for more information.

mypy considers some of your code unreachable.

See :ref:`unreachable` for more information.

A function annotated as returning a non-optional type returns ‘None’

and mypy doesn’t complain.

def foo() -> str: return None # No error!

You may have disabled strict optional checking (see

:ref:`no_strict_optional` for more).

Spurious errors and locally silencing the checker

You can use a # type: ignore comment to silence the type checker

on a particular line. For example, let’s say our code is using

the C extension module frobnicate, and there’s no stub available.

Mypy will complain about this, as it has no information about the

module:

import frobnicate # Error: No module "frobnicate" frobnicate.start()

You can add a # type: ignore comment to tell mypy to ignore this

error:

import frobnicate # type: ignore frobnicate.start() # Okay!

The second line is now fine, since the ignore comment causes the name

frobnicate to get an implicit Any type.

Note

You can use the form # type: ignore[<code>] to only ignore

specific errors on the line. This way you are less likely to

silence unexpected errors that are not safe to ignore, and this

will also document what the purpose of the comment is. See

:ref:`error-codes` for more information.

Note

The # type: ignore comment will only assign the implicit Any

type if mypy cannot find information about that particular module. So,

if we did have a stub available for frobnicate then mypy would

ignore the # type: ignore comment and typecheck the stub as usual.

Another option is to explicitly annotate values with type Any —

mypy will let you perform arbitrary operations on Any

values. Sometimes there is no more precise type you can use for a

particular value, especially if you use dynamic Python features

such as :py:meth:`__getattr__ <object.__getattr__>`:

class Wrapper: ... def __getattr__(self, a: str) -> Any: return getattr(self._wrapped, a)

Finally, you can create a stub file (.pyi) for a file that

generates spurious errors. Mypy will only look at the stub file

and ignore the implementation, since stub files take precedence

over .py files.

Ignoring a whole file

- To only ignore errors, use a top-level

# mypy: ignore-errorscomment instead. - To only ignore errors with a specific error code, use a top-level

# mypy: disable-error-code=...comment. - To replace the contents of a module with

Any, use a per-modulefollow_imports = skip.

See :ref:`Following imports <follow-imports>` for details.

Note that a # type: ignore comment at the top of a module (before any statements,

including imports or docstrings) has the effect of ignoring the entire contents of the module.

This behaviour can be surprising and result in

«Module … has no attribute … [attr-defined]» errors.

Issues with code at runtime

Idiomatic use of type annotations can sometimes run up against what a given

version of Python considers legal code. These can result in some of the

following errors when trying to run your code:

ImportErrorfrom circular importsNameError: name "X" is not definedfrom forward referencesTypeError: 'type' object is not subscriptablefrom types that are not generic at runtimeImportErrororModuleNotFoundErrorfrom use of stub definitions not available at runtimeTypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for |: 'type' and 'type'from use of new syntax

For dealing with these, see :ref:`runtime_troubles`.

Mypy runs are slow

If your mypy runs feel slow, you should probably use the :ref:`mypy

daemon <mypy_daemon>`, which can speed up incremental mypy runtimes by

a factor of 10 or more. :ref:`Remote caching <remote-cache>` can

make cold mypy runs several times faster.

Types of empty collections

You often need to specify the type when you assign an empty list or

dict to a new variable, as mentioned earlier:

Without the annotation mypy can’t always figure out the

precise type of a.

You can use a simple empty list literal in a dynamically typed function (as the

type of a would be implicitly Any and need not be inferred), if type

of the variable has been declared or inferred before, or if you perform a simple

modification operation in the same scope (such as append for a list):

a = [] # Okay because followed by append, inferred type List[int] for i in range(n): a.append(i * i)

However, in more complex cases an explicit type annotation can be

required (mypy will tell you this). Often the annotation can

make your code easier to understand, so it doesn’t only help mypy but

everybody who is reading the code!

Redefinitions with incompatible types

Each name within a function only has a single ‘declared’ type. You can

reuse for loop indices etc., but if you want to use a variable with

multiple types within a single function, you may need to instead use

multiple variables (or maybe declare the variable with an Any type).

def f() -> None: n = 1 ... n = 'x' # error: Incompatible types in assignment (expression has type "str", variable has type "int")

Note

Using the :option:`—allow-redefinition <mypy —allow-redefinition>`

flag can suppress this error in several cases.

Note that you can redefine a variable with a more precise or a more

concrete type. For example, you can redefine a sequence (which does

not support sort()) as a list and sort it in-place:

def f(x: Sequence[int]) -> None: # Type of x is Sequence[int] here; we don't know the concrete type. x = list(x) # Type of x is List[int] here. x.sort() # Okay!

See :ref:`type-narrowing` for more information.

Invariance vs covariance

Most mutable generic collections are invariant, and mypy considers all

user-defined generic classes invariant by default

(see :ref:`variance-of-generics` for motivation). This could lead to some

unexpected errors when combined with type inference. For example:

class A: ... class B(A): ... lst = [A(), A()] # Inferred type is List[A] new_lst = [B(), B()] # inferred type is List[B] lst = new_lst # mypy will complain about this, because List is invariant

Possible strategies in such situations are:

-

Use an explicit type annotation:

new_lst: List[A] = [B(), B()] lst = new_lst # OK

-

Make a copy of the right hand side:

lst = list(new_lst) # Also OK

-

Use immutable collections as annotations whenever possible:

def f_bad(x: List[A]) -> A: return x[0] f_bad(new_lst) # Fails def f_good(x: Sequence[A]) -> A: return x[0] f_good(new_lst) # OK

Declaring a supertype as variable type

Sometimes the inferred type is a subtype (subclass) of the desired

type. The type inference uses the first assignment to infer the type

of a name:

class Shape: ... class Circle(Shape): ... class Triangle(Shape): ... shape = Circle() # mypy infers the type of shape to be Circle shape = Triangle() # error: Incompatible types in assignment (expression has type "Triangle", variable has type "Circle")

You can just give an explicit type for the variable in cases such the

above example:

shape: Shape = Circle() # The variable s can be any Shape, not just Circle shape = Triangle() # OK

Complex type tests

Mypy can usually infer the types correctly when using :py:func:`isinstance <isinstance>`,

:py:func:`issubclass <issubclass>`,

or type(obj) is some_class type tests,

and even :ref:`user-defined type guards <type-guards>`,

but for other kinds of checks you may need to add an

explicit type cast:

from typing import Sequence, cast def find_first_str(a: Sequence[object]) -> str: index = next((i for i, s in enumerate(a) if isinstance(s, str)), -1) if index < 0: raise ValueError('No str found') found = a[index] # Has type "object", despite the fact that we know it is "str" return cast(str, found) # We need an explicit cast to make mypy happy

Alternatively, you can use an assert statement together with some

of the supported type inference techniques:

def find_first_str(a: Sequence[object]) -> str: index = next((i for i, s in enumerate(a) if isinstance(s, str)), -1) if index < 0: raise ValueError('No str found') found = a[index] # Has type "object", despite the fact that we know it is "str" assert isinstance(found, str) # Now, "found" will be narrowed to "str" return found # No need for the explicit "cast()" anymore

Note

Note that the :py:class:`object` type used in the above example is similar

to Object in Java: it only supports operations defined for all

objects, such as equality and :py:func:`isinstance`. The type Any,

in contrast, supports all operations, even if they may fail at

runtime. The cast above would have been unnecessary if the type of

o was Any.

Note

You can read more about type narrowing techniques :ref:`here <type-narrowing>`.

Type inference in Mypy is designed to work well in common cases, to be

predictable and to let the type checker give useful error

messages. More powerful type inference strategies often have complex

and difficult-to-predict failure modes and could result in very

confusing error messages. The tradeoff is that you as a programmer

sometimes have to give the type checker a little help.

Python version and system platform checks

Mypy supports the ability to perform Python version checks and platform

checks (e.g. Windows vs Posix), ignoring code paths that won’t be run on

the targeted Python version or platform. This allows you to more effectively

typecheck code that supports multiple versions of Python or multiple operating

systems.

More specifically, mypy will understand the use of :py:data:`sys.version_info` and

:py:data:`sys.platform` checks within if/elif/else statements. For example:

import sys # Distinguishing between different versions of Python: if sys.version_info >= (3, 8): # Python 3.8+ specific definitions and imports else: # Other definitions and imports # Distinguishing between different operating systems: if sys.platform.startswith("linux"): # Linux-specific code elif sys.platform == "darwin": # Mac-specific code elif sys.platform == "win32": # Windows-specific code else: # Other systems

As a special case, you can also use one of these checks in a top-level

(unindented) assert; this makes mypy skip the rest of the file.

Example:

import sys assert sys.platform != 'win32' # The rest of this file doesn't apply to Windows.

Some other expressions exhibit similar behavior; in particular,

:py:data:`~typing.TYPE_CHECKING`, variables named MYPY, and any variable

whose name is passed to :option:`—always-true <mypy —always-true>` or :option:`—always-false <mypy —always-false>`.

(However, True and False are not treated specially!)

Note

Mypy currently does not support more complex checks, and does not assign

any special meaning when assigning a :py:data:`sys.version_info` or :py:data:`sys.platform`

check to a variable. This may change in future versions of mypy.

By default, mypy will use your current version of Python and your current

operating system as default values for :py:data:`sys.version_info` and

:py:data:`sys.platform`.

To target a different Python version, use the :option:`—python-version X.Y <mypy —python-version>` flag.

For example, to verify your code typechecks if were run using Python 3.8, pass

in :option:`—python-version 3.8 <mypy —python-version>` from the command line. Note that you do not need

to have Python 3.8 installed to perform this check.

To target a different operating system, use the :option:`—platform PLATFORM <mypy —platform>` flag.

For example, to verify your code typechecks if it were run in Windows, pass

in :option:`—platform win32 <mypy —platform>`. See the documentation for :py:data:`sys.platform`

for examples of valid platform parameters.

Displaying the type of an expression

You can use reveal_type(expr) to ask mypy to display the inferred

static type of an expression. This can be useful when you don’t quite

understand how mypy handles a particular piece of code. Example:

reveal_type((1, 'hello')) # Revealed type is "Tuple[builtins.int, builtins.str]"

You can also use reveal_locals() at any line in a file

to see the types of all local variables at once. Example:

a = 1 b = 'one' reveal_locals() # Revealed local types are: # a: builtins.int # b: builtins.str

Note

reveal_type and reveal_locals are only understood by mypy and

don’t exist in Python. If you try to run your program, you’ll have to

remove any reveal_type and reveal_locals calls before you can

run your code. Both are always available and you don’t need to import

them.

Silencing linters

In some cases, linters will complain about unused imports or code. In

these cases, you can silence them with a comment after type comments, or on

the same line as the import:

# to silence complaints about unused imports from typing import List # noqa a = None # type: List[int]

To silence the linter on the same line as a type comment

put the linter comment after the type comment:

a = some_complex_thing() # type: ignore # noqa

Covariant subtyping of mutable protocol members is rejected

Mypy rejects this because this is potentially unsafe.

Consider this example:

from typing_extensions import Protocol class P(Protocol): x: float def fun(arg: P) -> None: arg.x = 3.14 class C: x = 42 c = C() fun(c) # This is not safe c.x << 5 # Since this will fail!

To work around this problem consider whether «mutating» is actually part

of a protocol. If not, then one can use a :py:class:`@property <property>` in

the protocol definition:

from typing_extensions import Protocol class P(Protocol): @property def x(self) -> float: pass def fun(arg: P) -> None: ... class C: x = 42 fun(C()) # OK

Dealing with conflicting names

Suppose you have a class with a method whose name is the same as an

imported (or built-in) type, and you want to use the type in another

method signature. E.g.:

class Message: def bytes(self): ... def register(self, path: bytes): # error: Invalid type "mod.Message.bytes" ...

The third line elicits an error because mypy sees the argument type

bytes as a reference to the method by that name. Other than

renaming the method, a workaround is to use an alias:

bytes_ = bytes class Message: def bytes(self): ... def register(self, path: bytes_): ...

Using a development mypy build

You can install the latest development version of mypy from source. Clone the

mypy repository on GitHub, and then run

pip install locally:

git clone https://github.com/python/mypy.git cd mypy python3 -m pip install --upgrade .

To install a development version of mypy that is mypyc-compiled, see the

instructions at the mypyc wheels repo.

Variables vs type aliases

Mypy has both type aliases and variables with types like Type[...]. These are

subtly different, and it’s important to understand how they differ to avoid pitfalls.

-

A variable with type

Type[...]is defined using an assignment with an

explicit type annotation:class A: ... tp: Type[A] = A

-

You can define a type alias using an assignment without an explicit type annotation

at the top level of a module:You can also use

TypeAlias(PEP 613) to define an explicit type alias:from typing import TypeAlias # "from typing_extensions" in Python 3.9 and earlier class A: ... Alias: TypeAlias = A

You should always use

TypeAliasto define a type alias in a class body or

inside a function.

The main difference is that the target of an alias is precisely known statically, and this

means that they can be used in type annotations and other type contexts. Type aliases

can’t be defined conditionally (unless using

:ref:`supported Python version and platform checks <version_and_platform_checks>`):

class A: ... class B: ... if random() > 0.5: Alias = A else: # error: Cannot assign multiple types to name "Alias" without an # explicit "Type[...]" annotation Alias = B tp: Type[object] # "tp" is a variable with a type object value if random() > 0.5: tp = A else: tp = B # This is OK def fun1(x: Alias) -> None: ... # OK def fun2(x: tp) -> None: ... # Error: "tp" is not valid as a type

Incompatible overrides

It’s unsafe to override a method with a more specific argument type,

as it violates the Liskov substitution principle.

For return types, it’s unsafe to override a method with a more general

return type.

Other incompatible signature changes in method overrides, such as

adding an extra required parameter, or removing an optional parameter,

will also generate errors. The signature of a method in a subclass

should accept all valid calls to the base class method. Mypy

treats a subclass as a subtype of the base class. An instance of a

subclass is valid everywhere where an instance of the base class is

valid.

This example demonstrates both safe and unsafe overrides:

from typing import Sequence, List, Iterable class A: def test(self, t: Sequence[int]) -> Sequence[str]: ... class GeneralizedArgument(A): # A more general argument type is okay def test(self, t: Iterable[int]) -> Sequence[str]: # OK ... class NarrowerArgument(A): # A more specific argument type isn't accepted def test(self, t: List[int]) -> Sequence[str]: # Error ... class NarrowerReturn(A): # A more specific return type is fine def test(self, t: Sequence[int]) -> List[str]: # OK ... class GeneralizedReturn(A): # A more general return type is an error def test(self, t: Sequence[int]) -> Iterable[str]: # Error ...

You can use # type: ignore[override] to silence the error. Add it

to the line that generates the error, if you decide that type safety is

not necessary:

class NarrowerArgument(A): def test(self, t: List[int]) -> Sequence[str]: # type: ignore[override] ...

Unreachable code

Mypy may consider some code as unreachable, even if it might not be

immediately obvious why. It’s important to note that mypy will not

type check such code. Consider this example:

class Foo: bar: str = '' def bar() -> None: foo: Foo = Foo() return x: int = 'abc' # Unreachable -- no error

It’s easy to see that any statement after return is unreachable,

and hence mypy will not complain about the mis-typed code below

it. For a more subtle example, consider this code:

class Foo: bar: str = '' def bar() -> None: foo: Foo = Foo() assert foo.bar is None x: int = 'abc' # Unreachable -- no error

Again, mypy will not report any errors. The type of foo.bar is

str, and mypy reasons that it can never be None. Hence the

assert statement will always fail and the statement below will

never be executed. (Note that in Python, None is not an empty

reference but an object of type None.)

In this example mypy will go on to check the last line and report an

error, since mypy thinks that the condition could be either True or

False:

class Foo: bar: str = '' def bar() -> None: foo: Foo = Foo() if not foo.bar: return x: int = 'abc' # Reachable -- error

If you use the :option:`—warn-unreachable <mypy —warn-unreachable>` flag, mypy will generate

an error about each unreachable code block.

Narrowing and inner functions

Because closures in Python are late-binding (https://docs.python-guide.org/writing/gotchas/#late-binding-closures),

mypy will not narrow the type of a captured variable in an inner function.

This is best understood via an example:

def foo(x: Optional[int]) -> Callable[[], int]: if x is None: x = 5 print(x + 1) # mypy correctly deduces x must be an int here def inner() -> int: return x + 1 # but (correctly) complains about this line x = None # because x could later be assigned None return inner inner = foo(5) inner() # this will raise an error when called

To get this code to type check, you could assign y = x after x has been

narrowed, and use y in the inner function, or add an assert in the inner

function.

Type hints are an essential part of modern Python. Type hints are the enabler for clever IDEs, they document the code, and even reduce unit testing needs. Most importantly, type hints make the code more robust and maintainable which are the attributes that every serious project should aim for.

At Wolt we have witnessed the benefits of type hints, for example, in a web backend project which has 100k+ LOC and has already had 100+ Woltians contributing to it. In such a massive project the advantages of the type hints are evident. For example, the onboarding experience of the newcomers is smoother thanks to easier navigation of the codebase. Additionally, the static type checker surprisingly often catches bugs which would slip through the tests.

Mypy is the de facto static type checker for Python and it’s also the weapon of choice at Wolt. Alternatives include pyright from Microsoft, pytype from Google, and Pyre from Facebook. Mypy is great! However, its default configuration is too “loose” for serious projects. In this blog post, we’ll list a set of mypy configuration flags which should be flipped from their default value in order to gently enforce professional-grade type safety.

disallow_untyped_defs = True

By default, mypy doesn’t require any type hints, i.e. it has disallow_untyped_defs = False by default. If you want to enforce the usage of the type hints (for all function/method arguments and return values), disallow_untyped_defs should be flipped to True. disallow_untyped_defs = True is arguably the most important configuration option if you truly want to adopt typing in a Python project, whether it’s an existing or a fresh one.

You might think that it’d be too laborious to enforce type hints for all modules of an older (read: legacy) project. That’s of course true, and often not worth the initial investment. However, wouldn’t it be awesome if the mypy configuration would enforce all the new modules to have type hints? This can be achieved by

- Setting

disallow_untyped_defs = Trueon the global level (see global vs per-module configuration), - Setting

disallow_untyped_defs = Falsefor the “legacy” modules.

In other words, strict by default and loose when needed. This allows gradual typing while still enforcing usage of type hints for new code. At Wolt, we have successfully employed this strategy, for example, in the aforementioned 100k+ LOC project. It’s good practice to get rid of the disallow_untyped_defs = False option for an individual (legacy) module if the module requires some changes, e.g. a bug fix or a new feature. Also, adding types to legacy modules can be great fun during Friday afternoons. This way the type safety also gradually increases in the older parts of the codebase.

disallow_any_unimported = True

In short, disallow_any_unimported = True is to protect developers from falsely trusting that their dependencies are in tip-top shape typing-wise. When something is imported from a dependency, it’s resolved to Any if mypy can’t resolve the import. This can happen, for example, if the dependency is not PEP 561 (Distributing and Packaging Type Information) compliant.

Way too often developers tend to take a shortcut and use ignore_missing_imports = True (even in the global level of the mypy configuration 😱) when they face something like

error: Skipping analyzing 'my-dependency': found module but no type hints or library stubs [import]

or

error: Library stubs not installed for "my-other-dependecy" (or incompatible with Python 3.9) [import]

note: Hint: "python3 -m pip install types-my-other-dependency"

note: (or run "mypy --install-types" to install all missing stub packages)

In the latter case the solution would be even immediately available and nicely suggested in the mypy output: just add a development dependency which contains the type stubs for the actual dependency. In fact, a number of popular projects have the stubs available. However, the former case is trickier. The developer could either

- try to find an existing stub project from the wild wild web,

- generate the stubs themselves (and hopefully consider open-sourcing them 😉) or

- use

ignore_missing_imports = Truefor the dependency in question.

disallow_any_unimported = True is basically to protect the developers from the consequences of the ignore_missing_imports = True case. For example, consider a project which depends on requests and would ignore the imports in the mypy.ini file.

[mypy-requests]

ignore_missing_imports = True

that would result in the following

from requests import Request

def my_function(request: Request) -> None:

reveal_type(request) # Revealed type is "Any"

and mypy would not give any errors. However, when disallow_any_unimported = True is used, mypy would give

Argument 1 to "my_function" becomes "Any" due to an unfollowed import [no-any-unimported]

Getting the error would be great as it would force the developer to find a better solution for the missing import. The “lazy” solution would be to add a suitable type ignore:

from requests import Request

def my_function(request: Request) -> None: # type: ignore[no-any-unimported]

...

This is already better as it nicely documents the Any for the readers of the code. Less surprises, less bugs.

no_implicit_optional = True

If the snippet below is ran with the default configuration of mypy, the type of arg is implicitly interpreted as Optional[str] (i.e. Union[str, None]) although it’s annotated as str.

def foo(arg: str = None) -> None:

reveal_type(arg) # Revealed type is "Union[builtins.str, None]"

In order to follow the Zen of Python’s (python -m this) “explicit is better than implicit“, consider setting no_implicit_optional = True. Then the above snippet would result in

error: Incompatible default for argument "arg" (default has type "None", argument has type "str") [assignment]

which would gently suggest to us to explicitly annotate the arg with Optional[str]:

from typing import Optional

def foo(arg: Optional[str] = None) -> None:

...

This version is notably better, especially considering the future readers of the code.

check_untyped_defs = True

With the mypy defaults, this is legit:

def bar(arg):

not_very_wise = "1" + 1

By default mypy doesn’t check what’s going on in the body of a function/method in case there are no type hints in the signature (i.e. arguments or return value). This won’t be an issue if disallow_untyped_defs = True is used. However, more than often it’s not the case, at least for some modules of the project. Thus, setting check_untyped_defs = True is encouraged. In the above scenario it would result in

error: Unsupported operand types for + ("str" and "int") [operator]

warn_return_any = True

This doesn’t give errors with the default mypy configuration:

from typing import Any

def baz() -> str:

return something_that_returns_any()

def something_that_returns_any() -> Any:

...

You might think that the example is not realistic. If so, consider that something_that_returns_any is a function in one of your project’s third-party dependencies or simply an untyped function.

With warn_return_any = True, running mypy would result in:

error: Returning Any from function declared to return "str" [no-any-return]

which is the error that developers would probably expect to see in the first place.

show_error_codes = True and warn_unused_ignores = True

Firstly, adding a type ignore should be the last resort. Type ignore is a sign of developer laziness in the majority of cases. However, in some cases, it’s justified to use them.

It’s good practice to ignore only the specific type of an error instead of silencing mypy completely for a line of code. In other words, prefer # type: ignore[<error-code>] over # type: ignore. This both makes sure that mypy only ignores what the developer thinks it’s ignoring and also improves the documentation of the ignore. Setting the configuration option show_error_codes = True will show the error codes in the output of the mypy runs.

When the code evolves, it’s not uncommon that a type ignore becomes useless, i.e. mypy would also be happy without the ignore. Well-maintained packages tend to include type hints sooner or later, for example, Flask added them in 2.0.0). It’s good practice to cleanup stale ignores. Using the warn_unused_ignores = True configuration option ensures that there are only ignores which are effective.

Parting words

The kind of global mypy configuration that best suits depends on the project. As a rule of thumb, make the configuration strict by default and loosen it up per-module if needed. This ensures that at least all the new modules follow best practices.

If you are unsure how mypy interprets certain types, reveal_type and reveal_locals are handy. Just remember to remove those after running mypy as they’ll crash your code during runtime.

As a final tip: never ever “silence” mypy by using ignore_errors = True. If you need to silence it for one reason or another, prefer type: ignore[<error-code>]s or a set of targeted configuration flags instead of silencing everything for the module in question. Otherwise the modules which depend on the erroneous module are also affected and, in the worst scenario, the developers don’t have a clue about it as the time bomb is well-hidden deep inside a configuration file.

Type-safe coding!

Want to join Jerry and build great things with Python at Wolt? 👋 We are looking for multiple Senior Python Engineers!

Type annotations are like comments

Type annotations are a great addition to Python. Thanks to them, finally our IDEs are able to provide good quality autocompletion. They did not turn Python into statically typed language, though. If you put a wrong annotation (or forget to update it after code change), Python will still happily try to execute your program. It just may fail miserably. Type annotations are like comments – they do not really have any influence on the way how your program works. They have also the same disadvantage – once they become obsolete, they start leading developers astray. Type annotations advantage is that they have a very specific format (unlike comments) so can be used to build tools that will make your life easier and code better. In this article, you will learn how to start using mypy, even if you like to add it to your existing project.

For the needs of this article, I will be using a large legacy monolithic project written in Django. I won’t show any actual snippets from it (because I have NDA on that) but I will demonstrate how mypy can be added even to such a messy codebase.

Step 1: install mypy

The first step is as easy as pip install mypy

mypy works like a linter – it performs static code analysis just like pylint or pycodestyle. Hence, if you split your dependencies into dev and “production” ones, you want to include mypy in the first category. If you use poetry, you could do with the command: poetry add --dev mypy

Don’t run it yet because you will only see dozens to thousands of errors you can’t really do anything about.

Step 2: Create the most basic mypy.ini

Create a config file in the root directory of your backend code and call it mypy.ini:

[mypy]

ignore_missing_imports = True

If you decided to ignore my warning and run mypy, it must have complained a lot about Skipping analyzing '': found module but no type hints or library stubs

That happens because mypy tries to check if 3rd party libraries. However, a lot of Python libraries is simply not type-annotated (yet), so that’s why we ignore this type of error. In my case (legacy Django project) this particular error was raised 3718 times.

Ideally, you would now see zero complaints but that’s rarely a case. Even though I have no type annotations, mypy is still able to find some issues thanks to inferring (guessing) types. For example, it is able to tell if we use a non-existent field of an object.

Dynamic typing versus mypy

Before showing the next step, let’s digress for a moment. Even though mypy complains about a few code lines it does not necessarily mean the code there won’t work. Most likely it does, it is just that mypy is not able to confirm that. When you start to write type annotations you will learn to write code in a bit different way. It will be simpler to analyse by mypy so it will complain considerably less.

Bear in mind that mypy is still in active development. At the moment of writing this article, it was in version 0.770. The tool may sometimes give false negatives i.e. complain about working code. In such a case, when you are certain the code works (e.g. is covered by tests) then you just put # type: ignore comment at the end of the problematic line of code.

Step 3: Choose one area of code you want to type-annotate

It is unrealistic to expect that introducing type annotations and mypy is possible in a blink of an eye. In legacy projects (like the one I experiment on) it would be a titanic effort to type-annotate all the code. Worse, it could bring no real benefit because certainly some areas are not changed anymore. I am sure there is a plenty dead code. Moreover, mypy will definitely affect the way of working on the project for the whole team. Lastly, we may simply come to the conclusion it is not working for us and want to get rid of that.

The point I am trying to make is – start small. Choose one area of code and start adopting mypy there. Let’s call this an experiment.

My legacy Django project consists of 28 applications. I could just choose one of them but I can go even further, for example, enforce type hints in just one file. Go with the size you are comfortable with. As a rule of thumb, you should be able to type-annotate it in less than 2 days, possibly less.

I’ve chosen an area that is still used but not changing too often except for rare bug fixes. Let’s say the application I will type-annotate is called “blog”.

Step 4: Turn off type checking in all areas except your experiment

Now, change your mypy.ini to something like:

[mypy]

ignore_missing_imports = True

ignore_errors = True

[mypy-blog.*]

ignore_errors = FalseWhere blog is a module you want to start with. If you would like to start with an even narrower scope, you can add more submodules after the dot.

[mypy]

ignore_missing_imports = True

ignore_errors = True

[mypy-blog.admin.*]

ignore_errors = FalseStep 5: Run mypy

Now, type mypy . This will once again print errors, but hopefully not too many. In my case, it is just 9 errors in 3 files. Not that bad.

Step 6: Fix errors

As I mentioned above, there are certain patterns I would say that make mypy freakout. As an exercise, you should rewrite the code or just learn how to put # type: ignore comment 🙂

In my code, 4 out of 9 errors concerned dead code, so I removed it.

Another one was complaining about Django migration. Since I have no interest in annotating it, I disabled checking migrations path in mypy.ini.

[mypy]

ignore_missing_imports = True

ignore_errors = True

[mypy-blog.*]

ignore_errors = False

[mypy-blog.migrations.*]

ignore_errors = TrueRemaining four errors were all found in admin.py file. One of them complained about assigning short_description to a function:

# mypy output

error: "Callable[[Any, Any, Any], Any]" has no attribute "short_description"

# in code

def delete_selected(modeladmin, request, queryset):

...

delete_selected.short_description = "Delete selected SOMETHING #NDA"mypy is right by saying the function indeed does not have short_description. On the other hand, this is Python and functions are objects. Hence, we can dynamically add properties to it in runtime. Since this is Django functionality, we can safely ignore it.

delete_selected.short_description = "Delete selected article language statuses" # type: ignoreThree errors left. All of them are the same and they are false negatives (but blame’s on me, I fooled mypy into thinking the code will not work)

# mypy output

error: Incompatible types in assignment (expression has type "Type[BlogImage]", base class "MyAdminMixin" defined the type as "None")

# in code

class BlogImageInline(MyAdminMixin, admin.TabularInline):

model = BlogImage # this line is problematic

class MyAdminMixin:

model = NoneSimply saying, we inherit from a class that has a field declared with default value None. It is always overridden in subclasses, but mypy thinks we are doing something nasty that way. Well, in reality, we’re gonna always use a subclass of Django model here, so let’s just type annotate our mixin and get rid of final 3 errors:

from django.db import models

from typing import Type

class MyAdminMixin:

model: Type[models.Model]Step 7: Turn on more restrictive checks

By default mypy only checks code that either has type annotations or the type can be inferred. It doesn’t force writing type annotations on you, though eventually, you want it. It is much simpler to enforce it when starting a greenfield project, but not impossible in legacy codebases.

There is a lot of options to find out, but let’s start from the most useful two:

- disallow_untyped_defs

- disallow_untyped_calls

Just put them in your mypy.ini with value = True to start getting errors for missing type annotations.

[mypy]

ignore_missing_imports = True

ignore_errors = True

[mypy-blog.*]

ignore_errors = False

disallow_untyped_defs = True

disallow_untyped_calls = TrueThere are plenty of other options worth checking out. See The mypy configuration file.

Step 8: Fix errors

Now I got 122 errors from 13 files. The most common one is complaint about missing type annotations in a function. In other words, mypy wants us to put annotations for arguments and return types.

error: Function is missing a return type annotation

It doesn’t mean I have to do all this mundane work at once. For example, 62 out of 122 are coming from tests. I can as well disable checks there (at least temporarily) to focus on annotating views, serializers and models.

[mypy]

ignore_missing_imports = True

ignore_errors = True

[mypy-blog.*]

ignore_errors = False

disallow_untyped_defs = True

disallow_untyped_calls = True

[mypy-blog.tests.*]

disallow_untyped_defs = False

disallow_untyped_calls = FalseThen, start adding annotations to functions…

# before

def translate_blog_post(source_language_id, destination_langauge_id):

pass

# after

def translate_blog_post(source_language_id: int, destination_langauge_id: int) -> None:

passLet mypy guide you. Run it often to fix new issues as they appear. For example, when you type annotate your functions, it will tell you about places when you misuse them, for example by giving None as an argument even though type annotation specifies it should be int.

The whole process can be tiresome, but it is the best way to learn how to write type annotations.

Step 9: Repeat steps 7-8

That’s it for our short guide of adopting mypy 🙂 Stay tuned for the next two parts where we are going to explore ways to automate type annotating codebases and learn about awesome tools that use type annotations to make your life easier and code better.

What can’t be covered by this is series is how to efficiently write type annotations. You need to practice on your own. Don’t forget to check out mypy and typing module’s documentation (links below).

Let me know in comments if you have encountered any interesting problems when trying to adopt mypy!

Further reading

- The mypy configuration file

- Type hints cheat sheet

- typing module documentation

- Dropbox: Our way to type checking 4 millions of Python

7

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Python Type Checking

In this guide, you will get a look into Python type checking. Traditionally, types have been handled by the Python interpreter in a flexible but implicit way. Recent versions of Python allow you to specify explicit type hints that can be used by different tools to help you develop your code more efficiently.

In this tutorial, you’ll learn about the following:

- Type annotations and type hints

- Adding static types to code, both your code and the code of others

- Running a static type checker

- Enforcing types at runtime

This is a comprehensive guide that will cover a lot of ground. If you want to just get a quick glimpse of how type hints work in Python, and see whether type checking is something you would include in your code, you don’t need to read all of it. The two sections Hello Types and Pros and Cons will give you a taste of how type checking works and recommendations about when it’ll be useful.

Type Systems

All programming languages include some kind of type system that formalizes which categories of objects it can work with and how those categories are treated. For instance, a type system can define a numerical type, with 42 as one example of an object of numerical type.

Dynamic Typing

Python is a dynamically typed language. This means that the Python interpreter does type checking only as code runs, and that the type of a variable is allowed to change over its lifetime. The following dummy examples demonstrate that Python has dynamic typing:

>>>

>>> if False:

... 1 + "two" # This line never runs, so no TypeError is raised

... else:

... 1 + 2

...

3

>>> 1 + "two" # Now this is type checked, and a TypeError is raised

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str'

In the first example, the branch 1 + "two" never runs so it’s never type checked. The second example shows that when 1 + "two" is evaluated it raises a TypeError since you can’t add an integer and a string in Python.

Next, let’s see if variables can change type:

>>>

>>> thing = "Hello"

>>> type(thing)

<class 'str'>

>>> thing = 28.1

>>> type(thing)

<class 'float'>

type() returns the type of an object. These examples confirm that the type of thing is allowed to change, and Python correctly infers the type as it changes.

Static Typing

The opposite of dynamic typing is static typing. Static type checks are performed without running the program. In most statically typed languages, for instance C and Java, this is done as your program is compiled.

With static typing, variables generally are not allowed to change types, although mechanisms for casting a variable to a different type may exist.

Let’s look at a quick example from a statically typed language. Consider the following Java snippet:

String thing;

thing = "Hello";

The first line declares that the variable name thing is bound to the String type at compile time. The name can never be rebound to another type. In the second line, thing is assigned a value. It can never be assigned a value that is not a String object. For instance, if you were to later say thing = 28.1f the compiler would raise an error because of incompatible types.

Python will always remain a dynamically typed language. However, PEP 484 introduced type hints, which make it possible to also do static type checking of Python code.

Unlike how types work in most other statically typed languages, type hints by themselves don’t cause Python to enforce types. As the name says, type hints just suggest types. There are other tools, which you’ll see later, that perform static type checking using type hints.

Duck Typing

Another term that is often used when talking about Python is duck typing. This moniker comes from the phrase “if it walks like a duck and it quacks like a duck, then it must be a duck” (or any of its variations).

Duck typing is a concept related to dynamic typing, where the type or the class of an object is less important than the methods it defines. Using duck typing you do not check types at all. Instead you check for the presence of a given method or attribute.

As an example, you can call len() on any Python object that defines a .__len__() method:

>>>

>>> class TheHobbit:

... def __len__(self):

... return 95022

...

>>> the_hobbit = TheHobbit()

>>> len(the_hobbit)

95022

Note that the call to len() gives the return value of the .__len__() method. In fact, the implementation of len() is essentially equivalent to the following:

def len(obj):

return obj.__len__()

In order to call len(obj), the only real constraint on obj is that it must define a .__len__() method. Otherwise, the object can be of types as different as str, list, dict, or TheHobbit.

Duck typing is somewhat supported when doing static type checking of Python code, using structural subtyping. You’ll learn more about duck typing later.

Hello Types

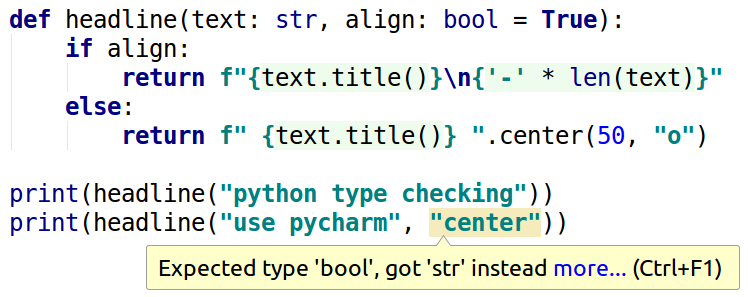

In this section you’ll see how to add type hints to a function. The following function turns a text string into a headline by adding proper capitalization and a decorative line:

def headline(text, align=True):

if align:

return f"{text.title()}n{'-' * len(text)}"

else:

return f" {text.title()} ".center(50, "o")

By default the function returns the headline left aligned with an underline. By setting the align flag to False you can alternatively have the headline be centered with a surrounding line of o:

>>>

>>> print(headline("python type checking"))

Python Type Checking

--------------------

>>> print(headline("python type checking", align=False))

oooooooooooooo Python Type Checking oooooooooooooo

It’s time for our first type hints! To add information about types to the function, you simply annotate its arguments and return value as follows:

def headline(text: str, align: bool = True) -> str:

...

The text: str syntax says that the text argument should be of type str. Similarly, the optional align argument should have type bool with the default value True. Finally, the -> str notation specifies that headline() will return a string.

In terms of style, PEP 8 recommends the following:

- Use normal rules for colons, that is, no space before and one space after a colon:

text: str. - Use spaces around the

=sign when combining an argument annotation with a default value:align: bool = True. - Use spaces around the

->arrow:def headline(...) -> str.

Adding type hints like this has no runtime effect: they are only hints and are not enforced on their own. For instance, if we use a wrong type for the (admittedly badly named) align argument, the code still runs without any problems or warnings:

>>>

>>> print(headline("python type checking", align="left"))

Python Type Checking

--------------------

To catch this kind of error you can use a static type checker. That is, a tool that checks the types of your code without actually running it in the traditional sense.

You might already have such a type checker built into your editor. For instance PyCharm immediately gives you a warning:

The most common tool for doing type checking is Mypy though. You’ll get a short introduction to Mypy in a moment, while you can learn much more about how it works later.

If you don’t already have Mypy on your system, you can install it using pip:

Put the following code in a file called headlines.py:

1# headlines.py

2

3def headline(text: str, align: bool = True) -> str:

4 if align:

5 return f"{text.title()}n{'-' * len(text)}"

6 else:

7 return f" {text.title()} ".center(50, "o")

8

9print(headline("python type checking"))

10print(headline("use mypy", align="center"))

This is essentially the same code you saw earlier: the definition of headline() and two examples that are using it.

Now run Mypy on this code:

$ mypy headlines.py

headlines.py:10: error: Argument "align" to "headline" has incompatible

type "str"; expected "bool"

Based on the type hints, Mypy is able to tell us that we are using the wrong type on line 10.

To fix the issue in the code you should change the value of the align argument you are passing in. You might also rename the align flag to something less confusing:

1# headlines.py

2

3def headline(text: str, centered: bool = False) -> str:

4 if not centered:

5 return f"{text.title()}n{'-' * len(text)}"

6 else:

7 return f" {text.title()} ".center(50, "o")

8

9print(headline("python type checking"))

10print(headline("use mypy", centered=True))

Here you’ve changed align to centered, and correctly used a Boolean value for centered when calling headline(). The code now passes Mypy:

$ mypy headlines.py

Success: no issues found in 1 source file

The success message confirms there were no type errors detected. Older versions of Mypy used to indicate this by showing no output at all. Furthermore, when you run the code you see the expected output:

$ python headlines.py

Python Type Checking

--------------------

oooooooooooooooooooo Use Mypy oooooooooooooooooooo

The first headline is aligned to the left, while the second one is centered.

Pros and Cons

The previous section gave you a little taste of what type checking in Python looks like. You also saw an example of one of the advantages of adding types to your code: type hints help catch certain errors. Other advantages include:

-

Type hints help document your code. Traditionally, you would use docstrings if you wanted to document the expected types of a function’s arguments. This works, but as there is no standard for docstrings (despite PEP 257 they can’t be easily used for automatic checks.

-

Type hints improve IDEs and linters. They make it much easier to statically reason about your code. This in turn allows IDEs to offer better code completion and similar features. With the type annotation, PyCharm knows that

textis a string, and can give specific suggestions based on this: -

Type hints help you build and maintain a cleaner architecture. The act of writing type hints forces you to think about the types in your program. While the dynamic nature of Python is one of its great assets, being conscious about relying on duck typing, overloaded methods, or multiple return types is a good thing.

Of course, static type checking is not all peaches and cream. There are also some downsides you should consider:

-

Type hints take developer time and effort to add. Even though it probably pays off in spending less time debugging, you will spend more time entering code.

-

Type hints work best in modern Pythons. Annotations were introduced in Python 3.0, and it’s possible to use type comments in Python 2.7. Still, improvements like variable annotations and postponed evaluation of type hints mean that you’ll have a better experience doing type checks using Python 3.6 or even Python 3.7.

-

Type hints introduce a slight penalty in startup time. If you need to use the

typingmodule the import time may be significant, especially in short scripts.

You’ll later learn about the typing module, and how it’s necessary in most cases when you add type hints. Importing modules necessarily take some time, but how much?

To get some idea about this, create two files: empty_file.py should be an empty file, while import_typing.py should contain the following line:

On Linux it’s quite easy to check how much time the typing import takes using the perf utility:

$ perf stat -r 1000 python3.6 import_typing.py

Performance counter stats for 'python3.6 import_typing.py' (1000 runs):

[ ... extra information hidden for brevity ... ]

0.045161650 seconds time elapsed ( +- 0.77% )

So running the import typing.py script takes about 45 milliseconds. Of course this is not all time spent on importing typing. Some of this is overhead in starting the Python interpreter, so let’s compare to running Python on an empty file:

$ perf stat -r 1000 python3.6 empty_file.py

Performance counter stats for 'python3.6 empty_file.py' (1000 runs):

[ ... extra information hidden for brevity ... ]

0.028077845 seconds time elapsed ( +- 0.49% )

Based on this test, the import of the typing module takes around 17 milliseconds on Python 3.6.

One of the advertised improvements in Python 3.7 is faster startup. Let’s see if the results are different:

$ perf stat -r 1000 python3.7 import_typing.py

[...]

0.025979806 seconds time elapsed ( +- 0.31% )

$ perf stat -r 1000 python3.7 empty_file.py

[...]

0.020002505 seconds time elapsed ( +- 0.30% )

Indeed, the general startup time is reduced by about 8 milliseconds, and the time to import typing is down from 17 to around 6 milliseconds—almost 3 times faster.

Using timeit

There are similar tools on other platforms. Python itself comes with the timeit module in the standard library. Typically, we would directly use timeit for the timings above. However, timeit struggles to time imports reliably because Python is clever about importing modules only once. Consider the following example:

$ python3.6 -m timeit "import typing"

10000000 loops, best of 3: 0.134 usec per loop

While you get a result, you should be suspicious about the result: 0.1 microsecond is more than 100000 times faster than what perf measured! What timeit has actually done is to run the import typing statement 30 million times, with Python actually only importing typing once.

To get reasonable results you can tell timeit to only run once:

$ python3.6 -m timeit -n 1 -r 1 "import typing"

1 loops, best of 1: 9.77 msec per loop

$ python3.7 -m timeit -n 1 -r 1 "import typing"

1 loop, best of 1: 1.97 msec per loop

These results are on the same scale as the results from perf above. However, since these are based on only one execution of the code, they are not as reliable as those based on multiple runs.

The conclusion in both these cases is that importing typing takes a few milliseconds. For the majority of programs and scripts you write this will probably not be an issue.

The New importtime Option

In Python 3.7 there is also a new command line option that can be used to figure out how much time imports take. Using -X importtime you’ll get a report about all imports that are made:

$ python3.7 -X importtime import_typing.py

import time: self [us] | cumulative | imported package

[ ... some information hidden for brevity ... ]

import time: 358 | 358 | zipimport

import time: 2107 | 14610 | site

import time: 272 | 272 | collections.abc

import time: 664 | 3058 | re

import time: 3044 | 6373 | typing

This shows a similar result. Importing typing takes about 6 milliseconds. If you’ll read the report closely you can notice that around half of this time is spent on importing the collections.abc and re modules which typing depends on.

So, should you use static type checking in your own code? Well, it’s not an all-or-nothing question. Luckily, Python supports the concept of gradual typing. This means that you can gradually introduce types into your code. Code without type hints will be ignored by the static type checker. Therefore, you can start adding types to critical components, and continue as long as it adds value to you.

Looking at the lists above of pros and cons you’ll notice that adding types will have no effect on your running program or the users of your program. Type checking is meant to make your life as a developer better and more convenient.

A few rules of thumb on whether to add types to your project are:

-

If you are just beginning to learn Python, you can safely wait with type hints until you have more experience.

-

Type hints add little value in short throw-away scripts.

-

In libraries that will be used by others, especially ones published on PyPI, type hints add a lot of value. Other code using your libraries need these type hints to be properly type checked itself. For examples of projects using type hints see

cursive_re,black, our own Real Python Reader, and Mypy itself. -

In bigger projects, type hints help you understand how types flow through your code, and are highly recommended. Even more so in projects where you cooperate with others.

In his excellent article The State of Type Hints in Python Bernát Gábor recommends that “type hints should be used whenever unit tests are worth writing.” Indeed, type hints play a similar role as tests in your code: they help you as a developer write better code.

Hopefully you now have an idea about how type checking works in Python and whether it’s something you would like to employ in your own projects.

In the rest of this guide, we’ll go into more detail about the Python type system, including how you run static type checkers (with particular focus on Mypy), how you type check code that uses libraries without type hints, and how you use annotations at runtime.

Annotations

Annotations were introduced in Python 3.0, originally without any specific purpose. They were simply a way to associate arbitrary expressions to function arguments and return values.

Years later, PEP 484 defined how to add type hints to your Python code, based off work that Jukka Lehtosalo had done on his Ph.D. project—Mypy. The main way to add type hints is using annotations. As type checking is becoming more and more common, this also means that annotations should mainly be reserved for type hints.

The next sections explain how annotations work in the context of type hints.

Function Annotations

For functions, you can annotate arguments and the return value. This is done as follows:

def func(arg: arg_type, optarg: arg_type = default) -> return_type:

...

For arguments the syntax is argument: annotation, while the return type is annotated using -> annotation. Note that the annotation must be a valid Python expression.

The following simple example adds annotations to a function that calculates the circumference of a circle:

import math

def circumference(radius: float) -> float:

return 2 * math.pi * radius

When running the code, you can also inspect the annotations. They are stored in a special .__annotations__ attribute on the function:

>>>

>>> circumference(1.23)

7.728317927830891

>>> circumference.__annotations__

{'radius': <class 'float'>, 'return': <class 'float'>}

Sometimes you might be confused by how Mypy is interpreting your type hints. For those cases there are special Mypy expressions: reveal_type() and reveal_locals(). You can add these to your code before running Mypy, and Mypy will dutifully report which types it has inferred. As an example, save the following code to reveal.py:

1# reveal.py

2

3import math

4reveal_type(math.pi)

5

6radius = 1

7circumference = 2 * math.pi * radius

8reveal_locals()

Next, run this code through Mypy:

$ mypy reveal.py

reveal.py:4: error: Revealed type is 'builtins.float'

reveal.py:8: error: Revealed local types are:

reveal.py:8: error: circumference: builtins.float

reveal.py:8: error: radius: builtins.int

Even without any annotations Mypy has correctly inferred the types of the built-in math.pi, as well as our local variables radius and circumference.

If Mypy says that “Name ‘reveal_locals‘ is not defined” you might need to update your Mypy installation. The reveal_locals() expression is available in Mypy version 0.610 and later.

Variable Annotations

In the definition of circumference() in the previous section, you only annotated the arguments and the return value. You did not add any annotations inside the function body. More often than not, this is enough.

However, sometimes the type checker needs help in figuring out the types of variables as well. Variable annotations were defined in PEP 526 and introduced in Python 3.6. The syntax is the same as for function argument annotations:

pi: float = 3.142

def circumference(radius: float) -> float:

return 2 * pi * radius

The variable pi has been annotated with the float type hint.

Annotations of variables are stored in the module level __annotations__ dictionary:

>>>

>>> circumference(1)

6.284

>>> __annotations__

{'pi': <class 'float'>}

You’re allowed to annotate a variable without giving it a value. This adds the annotation to the __annotations__ dictionary, while the variable remains undefined:

>>>

>>> nothing: str

>>> nothing

NameError: name 'nothing' is not defined

>>> __annotations__

{'nothing': <class 'str'>}

Since no value was assigned to nothing, the name nothing is not yet defined.

Playing With Python Types, Part 1

Up until now you’ve only used basic types like str, float, and bool in your type hints. The Python type system is quite powerful, and supports many kinds of more complex types. This is necessary as it needs to be able to reasonably model Python’s dynamic duck typing nature.

In this section you will learn more about this type system, while implementing a simple card game. You will see how to specify:

- The type of sequences and mappings like tuples, lists and dictionaries

- Type aliases that make code easier to read

- That functions and methods do not return anything

- Objects that may be of any type

After a short detour into some type theory you will then see even more ways to specify types in Python. You can find the code examples from this section here.

Example: A Deck of Cards

The following example shows an implementation of a regular (French) deck of cards:

1# game.py

2

3import random

4

5SUITS = "♠ ♡ ♢ ♣".split()

6RANKS = "2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 J Q K A".split()

7

8def create_deck(shuffle=False):

9 """Create a new deck of 52 cards"""

10 deck = [(s, r) for r in RANKS for s in SUITS]

11 if shuffle:

12 random.shuffle(deck)

13 return deck

14

15def deal_hands(deck):

16 """Deal the cards in the deck into four hands"""

17 return (deck[0::4], deck[1::4], deck[2::4], deck[3::4])

18

19def play():

20 """Play a 4-player card game"""

21 deck = create_deck(shuffle=True)

22 names = "P1 P2 P3 P4".split()

23 hands = {n: h for n, h in zip(names, deal_hands(deck))}

24

25 for name, cards in hands.items():

26 card_str = " ".join(f"{s}{r}" for (s, r) in cards)

27 print(f"{name}: {card_str}")

28

29if __name__ == "__main__":

30 play()

Each card is represented as a tuple of strings denoting the suit and rank. The deck is represented as a list of cards. create_deck() creates a regular deck of 52 playing cards, and optionally shuffles the cards. deal_hands() deals the deck of cards to four players.

Finally, play() plays the game. As of now, it only prepares for a card game by constructing a shuffled deck and dealing cards to each player. The following is a typical output:

$ python game.py

P4: ♣9 ♢9 ♡2 ♢7 ♡7 ♣A ♠6 ♡K ♡5 ♢6 ♢3 ♣3 ♣Q

P1: ♡A ♠2 ♠10 ♢J ♣10 ♣4 ♠5 ♡Q ♢5 ♣6 ♠A ♣5 ♢4

P2: ♢2 ♠7 ♡8 ♢K ♠3 ♡3 ♣K ♠J ♢A ♣7 ♡6 ♡10 ♠K

P3: ♣2 ♣8 ♠8 ♣J ♢Q ♡9 ♡J ♠4 ♢8 ♢10 ♠9 ♡4 ♠Q

You will see how to extend this example into a more interesting game as we move along.

Sequences and Mappings

Let’s add type hints to our card game. In other words, let’s annotate the functions create_deck(), deal_hands(), and play(). The first challenge is that you need to annotate composite types like the list used to represent the deck of cards and the tuples used to represent the cards themselves.

With simple types like str, float, and bool, adding type hints is as easy as using the type itself:

>>>

>>> name: str = "Guido"

>>> pi: float = 3.142

>>> centered: bool = False

With composite types, you are allowed to do the same:

>>>

>>> names: list = ["Guido", "Jukka", "Ivan"]

>>> version: tuple = (3, 7, 1)

>>> options: dict = {"centered": False, "capitalize": True}

However, this does not really tell the full story. What will be the types of names[2], version[0], and options["centered"]? In this concrete case you can see that they are str, int, and bool, respectively. However, the type hints themselves give no information about this.

Instead, you should use the special types defined in the typing module. These types add syntax for specifying the types of elements of composite types. You can write the following:

>>>

>>> from typing import Dict, List, Tuple

>>> names: List[str] = ["Guido", "Jukka", "Ivan"]

>>> version: Tuple[int, int, int] = (3, 7, 1)

>>> options: Dict[str, bool] = {"centered": False, "capitalize": True}

Note that each of these types start with a capital letter and that they all use square brackets to define item types:

namesis a list of stringsversionis a 3-tuple consisting of three integersoptionsis a dictionary mapping strings to Boolean values

The typing module contains many more composite types, including Counter, Deque, FrozenSet, NamedTuple, and Set. In addition, the module includes other kinds of types that you’ll see in later sections.

Let’s return to the card game. A card is represented by a tuple of two strings. You can write this as Tuple[str, str], so the type of the deck of cards becomes List[Tuple[str, str]]. Therefore you can annotate create_deck() as follows:

8def create_deck(shuffle: bool = False) -> List[Tuple[str, str]]:

9 """Create a new deck of 52 cards"""

10 deck = [(s, r) for r in RANKS for s in SUITS]

11 if shuffle:

12 random.shuffle(deck)

13 return deck

In addition to the return value, you’ve also added the bool type to the optional shuffle argument.

In many cases your functions will expect some kind of sequence, and not really care whether it is a list or a tuple. In these cases you should use typing.Sequence when annotating the function argument:

from typing import List, Sequence

def square(elems: Sequence[float]) -> List[float]:

return [x**2 for x in elems]

Using Sequence is an example of using duck typing. A Sequence is anything that supports len() and .__getitem__(), independent of its actual type.

Type Aliases

The type hints might become quite oblique when working with nested types like the deck of cards. You may need to stare at List[Tuple[str, str]] a bit before figuring out that it matches our representation of a deck of cards.

Now consider how you would annotate deal_hands():

15def deal_hands(

16 deck: List[Tuple[str, str]]

17) -> Tuple[

18 List[Tuple[str, str]],

19 List[Tuple[str, str]],

20 List[Tuple[str, str]],

21 List[Tuple[str, str]],

22]:

23 """Deal the cards in the deck into four hands"""

24 return (deck[0::4], deck[1::4], deck[2::4], deck[3::4])

That’s just terrible!

Recall that type annotations are regular Python expressions. That means that you can define your own type aliases by assigning them to new variables. You can for instance create Card and Deck type aliases:

from typing import List, Tuple

Card = Tuple[str, str]

Deck = List[Card]

Card can now be used in type hints or in the definition of new type aliases, like Deck in the example above.

Using these aliases, the annotations of deal_hands() become much more readable:

15def deal_hands(deck: Deck) -> Tuple[Deck, Deck, Deck, Deck]:

16 """Deal the cards in the deck into four hands"""

17 return (deck[0::4], deck[1::4], deck[2::4], deck[3::4])

Type aliases are great for making your code and its intent clearer. At the same time, these aliases can be inspected to see what they represent:

>>>

>>> from typing import List, Tuple

>>> Card = Tuple[str, str]

>>> Deck = List[Card]

>>> Deck

typing.List[typing.Tuple[str, str]]

Note that when printing Deck, it shows that it’s an alias for a list of 2-tuples of strings.

Functions Without Return Values

You may know that functions without an explicit return still return None:

>>>

>>> def play(player_name):

... print(f"{player_name} plays")

...

>>> ret_val = play("Jacob")

Jacob plays

>>> print(ret_val)

None

While such functions technically return something, that return value is not useful. You should add type hints saying as much by using None also as the return type:

1# play.py

2

3def play(player_name: str) -> None:

4 print(f"{player_name} plays")

5

6ret_val = play("Filip")

The annotations help catch the kinds of subtle bugs where you are trying to use a meaningless return value. Mypy will give you a helpful warning:

$ mypy play.py

play.py:6: error: "play" does not return a value

Note that being explicit about a function not returning anything is different from not adding a type hint about the return value:

# play.py

def play(player_name: str):

print(f"{player_name} plays")

ret_val = play("Henrik")

In this latter case Mypy has no information about the return value so it will not generate any warning:

$ mypy play.py

Success: no issues found in 1 source file

As a more exotic case, note that you can also annotate functions that are never expected to return normally. This is done using NoReturn:

from typing import NoReturn

def black_hole() -> NoReturn:

raise Exception("There is no going back ...")

Since black_hole() always raises an exception, it will never return properly.

Example: Play Some Cards

Let’s return to our card game example. In this second version of the game, we deal a hand of cards to each player as before. Then a start player is chosen and the players take turns playing their cards. There are not really any rules in the game though, so the players will just play random cards:

1# game.py

2

3import random

4from typing import List, Tuple

5

6SUITS = "♠ ♡ ♢ ♣".split()

7RANKS = "2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 J Q K A".split()

8

9Card = Tuple[str, str]

10Deck = List[Card]

11

12def create_deck(shuffle: bool = False) -> Deck:

13 """Create a new deck of 52 cards"""

14 deck = [(s, r) for r in RANKS for s in SUITS]

15 if shuffle:

16 random.shuffle(deck)

17 return deck

18

19def deal_hands(deck: Deck) -> Tuple[Deck, Deck, Deck, Deck]:

20 """Deal the cards in the deck into four hands"""

21 return (deck[0::4], deck[1::4], deck[2::4], deck[3::4])

22

23def choose(items):

24 """Choose and return a random item"""

25 return random.choice(items)

26

27def player_order(names, start=None):

28 """Rotate player order so that start goes first"""

29 if start is None:

30 start = choose(names)

31 start_idx = names.index(start)

32 return names[start_idx:] + names[:start_idx]

33

34def play() -> None:

35 """Play a 4-player card game"""

36 deck = create_deck(shuffle=True)

37 names = "P1 P2 P3 P4".split()

38 hands = {n: h for n, h in zip(names, deal_hands(deck))}

39 start_player = choose(names)

40 turn_order = player_order(names, start=start_player)

41

42 # Randomly play cards from each player's hand until empty

43 while hands[start_player]:

44 for name in turn_order:

45 card = choose(hands[name])

46 hands[name].remove(card)

47 print(f"{name}: {card[0] + card[1]:<3} ", end="")

48 print()

49

50if __name__ == "__main__":

51 play()

Note that in addition to changing play(), we have added two new functions that need type hints: choose() and player_order(). Before discussing how we’ll add type hints to them, here is an example output from running the game:

$ python game.py

P3: ♢10 P4: ♣4 P1: ♡8 P2: ♡Q

P3: ♣8 P4: ♠6 P1: ♠5 P2: ♡K

P3: ♢9 P4: ♡J P1: ♣A P2: ♡A

P3: ♠Q P4: ♠3 P1: ♠7 P2: ♠A

P3: ♡4 P4: ♡6 P1: ♣2 P2: ♠K

P3: ♣K P4: ♣7 P1: ♡7 P2: ♠2

P3: ♣10 P4: ♠4 P1: ♢5 P2: ♡3

P3: ♣Q P4: ♢K P1: ♣J P2: ♡9

P3: ♢2 P4: ♢4 P1: ♠9 P2: ♠10

P3: ♢A P4: ♡5 P1: ♠J P2: ♢Q

P3: ♠8 P4: ♢7 P1: ♢3 P2: ♢J

P3: ♣3 P4: ♡10 P1: ♣9 P2: ♡2

P3: ♢6 P4: ♣6 P1: ♣5 P2: ♢8

In this example, player P3 was randomly chosen as the starting player. In turn, each player plays a card: first P3, then P4, then P1, and finally P2. The players keep playing cards as long as they have any left in their hand.

The Any Type

choose() works for both lists of names and lists of cards (and any other sequence for that matter). One way to add type hints for this would be the following:

import random

from typing import Any, Sequence

def choose(items: Sequence[Any]) -> Any:

return random.choice(items)

This means more or less what it says: items is a sequence that can contain items of any type and choose() will return one such item of any type. Unfortunately, this is not that useful. Consider the following example:

1# choose.py

2

3import random

4from typing import Any, Sequence

5

6def choose(items: Sequence[Any]) -> Any:

7 return random.choice(items)

8

9names = ["Guido", "Jukka", "Ivan"]

10reveal_type(names)

11

12name = choose(names)

13reveal_type(name)

While Mypy will correctly infer that names is a list of strings, that information is lost after the call to choose() because of the use of the Any type:

$ mypy choose.py

choose.py:10: error: Revealed type is 'builtins.list[builtins.str*]'

choose.py:13: error: Revealed type is 'Any'