Более тридцати лет я занимаюсь изучением памяти и различных вариантов ее искажения. В моих первых исследованиях свидетельских показаний затрагивались несколько ключевых вопросов: когда человек становится свидетелем преступления или несчастного случая, насколько точны его воспоминания? что происходит, когда этого человека допрашивают в полиции, и что, если вопросы полицейских окажутся наводящими? В то время как другие исследователи мнестических процессов изучали запоминание слов, бес-смысленных слогов и иногда предложений, я стала показывать испытуемым сюжеты дорожно-транспортных происшествий и задавать им по-разному сформулированные вопросы. Вопрос «Видели ли вы, как разбилась фара?» вызывал больше ложных свидетельств о разбитой фаре, чем аналогичный вопрос с использованием слова «стукнуться». Вопрос «С какой скоростью двигались автомобили перед тем, как врезаться друг в друга?» побуждал испытуемых завышать оценку скорости, в отличие от нейтрального вопроса, содержавшего слово «столкнуться». Более того, использование слова «врезаться» приводило к тому, что большее количество опрошенных приходили к ложным утверждениям, что они видели разбитое стекло, в то время как на самом деле его m ныло. В моих ранних работах был сделан вывод о том, что наводящие вопросы могут исказить или трансформировать память свидетеля (см. обзор этих исследований в Loftus 1979/1996).

Фактически наводящие вопросы — это лишь один из способов искажения памяти. Дальнейшие исследования показали, что память можно «подправить» с помощью разнообразных техник, использующих передачу ложной информации ничего не подозревающему субъекту. Эти исследования проводились по довольно простой схеме. Испытуемым сперва показывали сложный сюжет, например симуляцию автомобильной аварии. Затем половина испытуемых получала недостоверную информацию об этой аварии, в то время как другая половина не подвергалась дезинформации. В конце все испытуемые пытались вспомнить обстоятельства происшествия. В одном из экспериментов с использованием описанной модели испытуемые наблюдали аварию, а затем часть из них получала ложные сведения о дорожном знаке, регулировавшем движение на перекрестке. Им сообщали, что знак «Стоп», который они видели, являлся на самом деле знаком «Уступи дорогу». Когда их позже просили вспомнить, какой знак они видели на перекрестке, те, кто выслушивал недостоверную информацию, пытались подстроить под нее свои воспоминания и утверждали, что видели знак «Уступи дорогу». При этом воспоминания тех, кто не получал ложных сведений, были гораздо более точными.

Недостоверная информация может повлиять на воспоминания человека, если ему задают наводящие вопросы, а также в ходе разговора с другими людьми, излагающими собственную версию событий. Дезинформация может сбить людей с толка, когда они читают предвзятые публикации в СМИ, касающиеся событий, в которых они участвовали сами. Этот феномен был назван эффектом дезинформации (Loftus & Hoffman, 1989).

Недавно было проведено исследование, целью которого являлось сопоставление относительной убеждающей силы дезинформации и гипноза (Scoboria, Mazzoni, Kirsch, & Milling, 2002). Испытуемым предлагалось прослушать историю, а затем им задавались либо нейтральные, либо вводящие в заблуждение вопросы, в то время как они находились под гипнозом или в обычном состоянии. При дальнейшей проверке оказалось, что применение гипноза увеличивало число ошибок памяти, однако использование наводящих вопросов привело к еще большему искажению воспоминаний. Более того, совмещение гипноза и наводящих вопросов по количеству вызванных ошибок превысило эффект от каждого приема по отдельности. Специфика ошибок в случае наводящих вопросов состояла в переходе от ответов «не знаю» к ответам, содержавшим ложную информацию о происшедших событиях. Из этого примера становится понятным, как перед исследователями открывается конкретный механизм, обеспечивающий быстрое и весьма длительное искажающее влияние дезинформации на память.

Внедрение ложных воспоминаний

Одно дело поменять знак «Стоп» на знак «Уступи дорогу» или добавить некую деталь в воспоминания о чем-то, что происходило на самом деле. Но возможно ли создать целостное воспоминание о событии, которого никогда не было? Моя первая попытка такого рода была связана с использованием методики, в рамках которой испытуемым предъявляли короткие устные описания событий из их детства, а затем предлагали им самим вспомнить эти события. При этом участники верили в то, что информация достоверна и получена от членов их семей, тогда как в действительности это были «псевдособытия», никогда с ними не случавшиеся. В проведенном исследовании около 25 % испытуемых удалось убедить, частично или полностью, что в возрасте 5-6 лет они надолго потерялись в большом супермаркете, были весьма напуганы и, в конце концов, спасены кем-то из взрослых и возвращены родителям (Loftus & Pickrell, 1995). Многие испытуемые потом дополняли свои «воспоминания» красочными подробностями.

Метод использования семейных историй для внедрения ложных воспоминаний получил название «методики ложного рассказа от семейного информатора» (Lindsay, Hagen, Read, Wade, & Garry, в печати), но, вероятно, проще называть ее «методикой потерявшегося-в-магазине». Многие исследователи использовали эту методику, чтобы имплантировать ложные воспоминания о событиях, которые могли бы быть куда более необычными, странными, болезненными, даже травматичными, случись они в реальной жизни. Одних испытуемых убеждали в том, что их увозили в больницу посреди ночи или в том, что с ними произошел несчастный на семейном торжестве (Hyman, Husband, & Billings, 1995; Hyman & Pentland, 1996). Других уверяли в том, что однажды они чуть не утонули и спасателям пришлось вытаскивать их из воды (Heaps & Nash, 2001). Третьим рассказывали, что когда-то они подверглись нападению бешеного животного (Porter, Yuille, & Lehman, 1999). Исследования показали, что только меньшинство испытуемых склонно к формированию частично или целиком ложных воспоминаний. В серии экспериментов, описанных Линдсей с соавторами, средний уровень ложных воспоминаний равнялся 31 %, однако, разумеется, подобные показатели могут варьировать. Иногда испытуемые проявляли устойчивость к попыткам внедрения воспоминаний (например, когда в ходе эксперимента их пытались убедить в том, что некогда с ними проводили ректальные процедуры с применением клизмы (Pezdek, Finger, & Hodge,1997)). И наоборот, иногда удается успешно внедрить ложные воспоминания более чем 50 % испытуемых, скажем, о полете на воздушном шаре (Wade, Garry, Read, & Lindsay, 2002). Особенно интересными являются случаи появления целиком ложных воспоминаний, или так называемых «насыщенных ложных воспоминаний», когда субъект уверен в их подлинности и даже дополняет их различными подробностями, выражает эмоции по поводу выдуманных событий, которые на самом деле с ним не происходили.

Насыщенные ложные воспоминания

В исследованиях искажений памяти снова и снова встает вопрос, касающийся интерпретации результатов: действительно ли мы внедряем ложные воспоминания? Возможно, наводящие манипуляции заставляют людей воскрешать в памяти реальные события, а не формировать ложные воспоминания. В поиске ответа на этот вопрос исследователи использовали несколько методик, включая попытку создать ложное воспоминание о недавних событиях (например: «Что вы делали в определенный день?»). Если исследователь точно знает, что было в этот день, и вызывает у испытуемого «воспоминания» о чем-то помимо реально происходившего, то он получает довольно веские доказательства формирования ложных воспоминаний. Впервые эта схема была применена Гоффом и Редигером (Goff & Roediger, 1998), а позднее была модифицирована нами (Thomas & Loftus, 2002). В одном из экспериментов испытуемые садились перед большим столом, заваленным различными вещами. Они прослушивали несколько предложений (например, «подбросьте монетку») и затем должны были выполнить или вообразить выполнение названных действий. В следующий раз, когда они приходили в лабораторию, перед ними не было никаких вещей, испытуемые должны были просто представить, что они выполняют разнообразные действия. В последней части эксперимента проводилось тестирование их памяти по поводу того, что происходило в первый день. Достаточно было представить себе то или иное действие, и испытуемые вдруг начинали припоминать действия, которых на самом деле не выполняли. Они выдавали ложные утверждения о действиях, которые могли быть обыденными (например, «бросать кости»), но кроме этого утверждали, что производили действия, которые должны были бы показаться им странными или необычными («посыпать голову мелом» или «поцеловать пластмассовую лягушку») (Thomas & Loftus, 2002).

Еще одним методом, позволяющим оценить, насколько подобного рода внушение способствует внедрению ложных воспоминаний, является внедрение воспоминаний о событиях, которые маловероятны или даже невозможны. К примеру, нам удалось внедрить убеждение или воспоминания о том, как испытуемые в детстве оказались свидетелями одержимости бесами (Mazzoni, Loftus, & Kirsch, 2001). Еще проще оказалось внедрить воспоминания о встрече с кроликом Багзом Банни в Диснейленде (Braun, Ellis & Loftus, 2002). Последнее удалось с помощью демонстрации поддельного рекламного ролика студии «Дисней» с Багзом Банни в главной роли. В одном из экспериментов показ поддельного рекламного ролика привел к тому, что 16 % испытуемых позже утверждали, будто бы лично встречали Багза Банни в Диснейленде. Этого не могло случиться, так как Багз Банни — персонаж студии Warner Brothers и поэтому никак не мог находиться в Диснейленде.

Что именно вспоминали люди о встрече с персонажем, которой в принципе не могло произойти? Среди тех, кто описывал личную встречу с Багзом, 62 % говорили о том, что пожали кролику лапу, а 46 % припомнили, как обняли его. Остальные вспоминали о том, как потрогали его за ухо или за хвостик или даже слышали его коронную фразу («В чем дело, Док?»). Таким образом, эти ложные воспоминания были насыщены чувственными подробностями, которые мы обычно используем в качестве ориентира, чтобы определить, является ли воспоминание истинным или ложным.

Сущность ложных воспоминаний

Настоящие воспоминания обычно имеют определенные последствия для людей. Если вы запомнили, как кто-то вас обидел, вы, вероятно, в будущем будете избегать контакта с этим неприятным субъектом. А если у вас сформировалось ложное воспоминание об этой обиде? Будете ли вы так же впоследствии избегать обидчика? Вполне вероятно, что так оно и будет, однако на практике все исследования ложных воспоминаний прекращаются, когда испытуемый принимает внедряемый сценарий. В некоторых исследованиях предпринимались попытки проверить, может ли испытуемый считать, что событие имело место, не переживая его заново. Порой все ограничивается лишь собственно ложным убеждением. Но встречаются и случаи, когда воспоминания наполнены чувственными подробностями. Именно этот опыт ближе всего к тому, что мы называем «насыщенными ложными воспомина-ниями». В типичных исследованиях после опроса, в ходе которого испытуемый демонстрирует наличие тех или иных воспоминаний, ему разъясняют суть происходящего. Но что, если отложить это объяснение на некоторое время, чтобы увидеть, могут ли ложные воспоминания повлиять на мысли или поведение испытуемого? В таком случае мы могли бы доказать, что ложные воспоминания действительно имеют значимые последствия.

Еще один подход к анализу этой проблемы состоит в следующем. Многократно показано, что наводящая информация может привести человека к ложным воспоминаниям. Однако существуют ли корреляты такого воспоминания? Есть ли другие умственные процессы или аспекты поведения, которые так же подвергаются влиянию, попадая под воздействие наводящей информации? Если да, то мы сможем обнаружить более глубокие последствия обсуждаемого феномена. Эта идея легла в основу исследования, целью которого было выявить, повлияет ли наводящее воздействие о встрече с кроликом Багзом Банни в Диснейленде на мышление испытуемого (Grinley, 2002). В этом исследовании испытуемых сперва убеждали в том, что во время посещения Диснейленда они видели Багза Банни. Затем давался новый тест: испытуемым предъявляли имена двух персонажей, например Микки Маус и Дональд Дак, а они должны были указать, в какой степени эти персонажи связаны друг с другом. Некоторые пары были тесно связаны (например, Микки и Минни Маус). Другие пары не имели друг к другу практически никакого отношения (например, Дональд Дак и Спящая Красавица). После просмотра поддельной рекламы студии «Дисней» с участием Багза Банни испытуемые оценивали связь Микки Мауса и Багза Банни как более тесную. Таким образом, на некоторое время мыслительные процессы или семантические структуры испытуемых, просмотревших видеоролик, оказались изменены.

Дальнейшее исследование последствий ложных представлений или воспоминаний было осуществлено в сотрудничестве с Дэниелом Бернштейном. Мы создавали у испытуемых уверенность в том, что в детстве они отравились сваренными вкрутую яйцами (во второй группе испытуемых речь шла о маринованных огурцах). Мы осуществили этот трюк, опросив испытуемых и обеспечив их ложной обратной связью. Мы сообщали им, что специальная компьютерная программа проанализировала их данные и пришла к выводу, что в детстве они пострадали от отравления одним из этих продуктов. Было выявлено, что у тех, кто получил обратную связь про маринованные огурцы, сформировалось более стойкое убеждение в том, что отравление произошло с ними в детстве, тогда как те, кто получил обратную связь о яйцах вкрутую, поверили в большей степени в отравление именно этим продуктом.

Но приведет ли рост уверенности к соответствующим изменениям в поведении? Станут ли испытуемые, к примеру, избегать в дальнейшем употребления этих продуктов, если они будут им предложены? Чтобы выяснить это, мы составили опросник, посвященный поведению на вечеринке. Испытуемым надо было представить, что их пригласили на вечеринку, и указать, какие угощения им захотелось бы съесть. Те, кого склоняли к версии отравления маринованными огурцами, проявляли меньшее желание попробовать этот продукт, тогда как те, кто получил информацию об отравлении яйцами, были менее склонны пробовать яйца.

Выводы, полученные в исследовании «отравлений», заложили основы методики изучения ложных воспоминаний и их последствий. Кроме того, мы неожиданно обнаружили потенциально простой способ заставить людей избегать определенных продуктов. В целом полученные нами результаты показывают, что изменение представлений или воспоминаний может иметь значительные последствия для последующих мыслей или поведения. Если вы изменяете свою память, то она, в свою очередь, изменяет вас.

Истинные воспоминания против ложных

В идеальном мире люди будут обладать технологией различения истинных и ложных воспоминаний. Сейчас эта возможность носит статистический характер. В ходе эксперимента по созданию ложных воспоминаний о том, как в детстве испытуемый заблудился в супермаркете, мы выявили, что истинных воспоминаний люди придерживаются с большей уверенностью, чем ложных (Loftus & Pickrell, 1995). Уэйд и группа психологов (2002), которые занимались внедрением ложных детских воспоминаний о полете на воздушном шаре, используя поддельные фотографии, тоже показали, что реальные события, о которых они спрашивали испытуемых, воспроизводятся с большей уверенностью, чем ложные.

Теоретические и практические выводы

В целом исследователи узнали довольно много о том, как рождаются ложные воспоминания, и практически готовы написать инструкцию по их внедрению. Вначале человека убеждают в том, что ненастоящее событие возможно. Даже те события, которые вначале выглядят как невозможные, можно сделать более реальными, используя простые наводящие суждения. Затем человека убеждают в том, что псевдособытие было пережито лично им.

Наиболее простой способ подвести человека к этому убеждению — использование ложной обратной связи. В этом случае испытуемый способен почти что поверить в то, что событие действительно имело место в прошлом, но еще не испытывает чувства узнавания. Если при этом направить воображение в нужное русло, визуализировать истории, рассказанные другими людьми, создать наводящую обратную связь, а также использовать другие мани-пулятивные техники, можно добиться появления насыщенных ложных воспоминаний.

Исследование ложных представлений и воспоминаний является весьма актуальным для нашей повседневной жизни. Анализ растущего числа ложных обвинений, неправомерность которых была доказана с помощью ДНК-экспертизы, показал, что основной их причиной являются искажения воспоминаний свидетелей. Это открытие привело к составлению огромного количества рекомендаций для правовых систем США и Канады с целью защиты следственного процесса от трагических ошибок из-за неточности свидетельских показаний (Yarmey, 2003). Вне сферы юриспруденции или психотерапии открытия, касающиеся искажений памяти, также имеют большое значение для повседневной жизни. Возьмем, к примеру, автобиографии и мемуары. Выдающийся физик Эдвард Теллер недавно выпустил свою автобиографию (Teller, 2001), после чего на него обрушилась сокрушительная критика из-за его «специфически» выборочной памяти и в особенности из-за «ярких воспоминаний о событиях, которые никогда не происходили». Более снисходительный анализ мемуаров Теллера побуждает отнестись к ней не как к хронике, полной намеренного вранья в корыстных целях, но как к нормальному процессу искажения памяти. Неправда не всегда является ложью. Необходима особая отрасль психологической науки, которая научила бы нас отличать намеренную ложь от лжи «искренней». Иногда случается, что намеренная ложь становится личной «правдой» человека. Именно история создает воспоминания, а не наоборот.

Говорят, что мы являемся суммой наших воспоминаний и все, что с нами случается, приводит к формированию этого конечного продукта — нас самих. Однако спустя три десятилетия, которые я посвятила исследованиям памяти в целом и в особенности ее искажениям, мне кажется важным обратить внимание на противоположный смысл этого высказывания. Память человека — не просто собрание всего, что с ним происходило в течение жизни, это нечто большее: воспоминания — это еще и то, что человек думал, что ему говорили, во что он верил. Наша сущность определяется нашей памятью, но нашу память определяет то, что мы из себя представляем и во что склонны верить. Создается впечатление, что мы перекраиваем свою память и в процессе этого становимся воплощением собственных фантазий.

В психологии известны случаи, когда взрослые люди рассказывали о счастливом детстве, а потом выяснялось, что они росли с жестокими родителями или подвергались травле в школе. Но это не ложь, а вытесненная память. Давайте поговорим о феномене ложных воспоминаний и выясним, когда память играет с нами.

Как формируются ложные воспоминания?

Память — это способность психики запоминать и воспроизводить информацию о чем-либо. В живом организме информация хранится не в виде наборов нулей и единиц (как в компьютерах), а в виде белков. Представьте: вы запомнили цвет глаз нового знакомого, это значит, что в клетках вашего мозга появилась новая белковая структура, в которой «зашифрованы» нужные данные. А теперь вообразите, что происходит с мозгом в результате опухоли, травмы или токсического поражения. Белок разрушается, а значит, и закодированная в нем информация становится зыбкой, память выдает ложные воспоминания.

Синдром ложных воспоминаний в психиатрии

Нарушение памяти, при котором возникают ложные воспоминания, в психиатрии называется парамнезией. Она возникает по следующим причинам:

-

Острый дефицит витамина В1 на фоне алкоголизма.

-

Повреждение мозга на фоне инсульта, аневризмы, опухоли, травмы, деменции, токсического воздействия.

-

Дисфункция префронтальной коры (старческое слабоумие).

Ложные воспоминания с убежденностью в их истинности возникают у людей с шизофренией и некоторыми другими психическими расстройствами. При этом пациенты испытывают различные иллюзии памяти:

-

Псевдореминисценции. Человек вспоминает реальное событие, произошедшее в прошлом, но ему кажется, что это случилось недавно. Часто встречается у пожилых людей с деменцией, когда они путаются во времени.

-

Конфабуляции. Память замещается фантастическими событиями, которые якобы случились с пациентом. Это напоминает фантазии и мечты, но для человека они реальны.

-

Криптомнезии. При этом нарушении человек воспринимает свою жизнь, как события из романа, или наоборот — замещает сценарием фильма собственное прошлое.

-

Фантазмы. Напоминают конфабуляции: человек выдумывает какие-то эпизоды, а потом верит в их истинность. При этом отличить истинные воспоминания от ложных для него невозможно.

Подробно о признаках психических нарушений мы уже рассказывали в рубрике «Психология». Но с феноменом ложных воспоминаний сталкиваются и абсолютно здоровые люди. Когда и почему это происходит?

Причины возникновения ложных воспоминаний у здоровых людей

-

Инфляция воображения. Допустим, мама рассказывала, что читала вам в детстве перед сном. Вы раз за разом представляете эту картину в деталях, «видите» узор на одеяле, «слышите» мамин голос. Со временем вам покажется, что вы не воображаете, а вспоминаете. Это частая причина ложных воспоминаний из детства.

-

Интерференция или влияние культурных стереотипов. В США проводили исследование, при котором испытуемые мельком видели убегающего человека. Затем им говорили, что это преступник. Если участник был подвержен установке, что большинство преступлений совершается чернокожими людьми, он «вспоминал», что и убегающий был темнокожим (хотя это не так).

-

Ретроспективные предубеждения. Вы знакомите родителей с невестой. Через 5 лет она вас бросает. Мама скажет, что уже тогда, пять лет назад, считала ее плохой партией. Это ложные воспоминания, сформированные в ретроспективе под влиянием того факта, что брак распался.

-

Конформизм памяти. Вы с друзьями выехали на природу. Вы уверены, что на вас была желтая футболка, но остальные утверждают, что она была красной. Через какое-то время вам покажется, что она действительно была красной. Часто память меняется под действием общественного мнения, появляются ложные воспоминания.

-

Психологическая защита. Если с человеком произошел травмирующий эпизод, память «вытеснит» его в бессознательное. Он либо забудет об этом событии, либо «нарисует» другой сценарий.

В целом, психология считает ложные воспоминания нормой, такой же, как и явления переноса и контрпереноса.

Онлайн-тест «Ваш эмоциональный интеллект»

Возможно ли внедрение ложных воспоминаний?

Нейробиологи провели эксперимент над мышами: они вводили подопытным препарат, который менял биохимию мозга. Это вызвало у животных ложные воспоминания, но их силу и глубину измерить не удалось.

Также известны факты, когда ложные воспоминания внедрялись людям под действием гипноза и психотропных препаратов. Однако, это нестойкие картинки, которые легко отличить от истинной памяти.

Чтобы лучше разобраться в устройстве памяти, записывайтесь на программу обучения «Практическая психология». На курсе вы узнаете психофизиологию ЦНС, разберете, как формируются воспоминания и поймете, как гипноз проникает в бессознательное. Также вы изучите основные механизмы психологической защиты, под действием которых события «исчезают» из воспоминаний. Полученные знания помогут вести сеансы психокоррекции и прорабатывать с клиентами глубокие детские травмы.

Воспоминания – это не только сентиментальные образы прошлого, в которые мы погружаемся перед сном. Из них складывается наш уникальный жизненный опыт, наши знания, навыки и отношения с другими людьми, а иногда от воспоминаний зависит даже чья-то жизнь. Но так ли надежен этот источник информации? Какие бывают ошибки памяти?

Память составляет основу нашего сознания – без способности запоминать, сохранять, воспроизводить и узнавать информацию было бы невозможно ни учиться, ни общаться, ни даже понимать самого себя. Недаром при сложных формах амнезии личность больного претерпевает сильнейшие изменения, вплоть до полного распада1.

Воспоминания составляют основу самых разных видов информации: писцы «по памяти» составляли летописи, мореплаватели – карты материков и океанов, а в литературе мемуары (от французского «mémoires», что в переводе и означает «воспоминания») и вовсе выделены в отдельный и хорошо развитой жанр. Свидетельские показания, то есть рассказ очевидцев о том, что они помнят о тех или иных событиях, могут стать основой для предъявления уголовного обвинения и даже смертной казни.

Однако при том, что значение информации, хранящейся в памяти, бывает необычайно велико, ее достоверность может оказаться весьма сомнительной. И дело не только в том, что многие подробности или детали забываются ровно в тот момент, когда они нужны, но и в том, что мы можем с полной ясностью и четкостью помнить события и факты… которых в реальности никогда не было.

То, чего не было. Нарушения памяти

Ученые выделяют два типа причин, по которым в памяти человека может оказаться информация, не соответствующая его реальному опыту. Первый – это нарушения памяти, имеющие общее название «парамнезии» – искажение или замещение содержания воспоминаний, связанные с особенностями функционирования определенных участков коры головного мозга1.

К парамнезиям относятся следующие типы расстройств памяти:

- Псевдореминисценции – замещение «провалов» в памяти событиями, происходившими с человеком в реальности, но в совершенно другое время. Пример псевдореминисценции – уверения пожилого человека, несколько месяцев не выходившего из дома, в том, что вчера он сходил на работу, пообщался с коллегами и вернулся домой на автобусе.

- Конфабуляции – явление, при котором утраченные в памяти события подменяются вымышленными, никогда не происходившими с человеком в реальности. Человек, страдающий таким расстройством, может ярко и красочно описывать, например, свой опыт общения с инопланетянами, якобы похищавшими его для лабораторных исследований и затем вернувшими обратно.

- Криптомнезии – «присвоение» человеком в качестве собственных воспоминаний информации, полученной из внешних источников. Так, человек может отчетливо «помнить», как участвовал в событиях, описанных в художественной книге, или считать себя автором стихов, написанных задолго до его рождения.

- Эхомнезии – ощущение, что то, что происходит с человеком в настоящий момент, уже происходило с ним в прошлом. Например, впервые в жизни госпитализированный больной уверяет, что он уже лежал в этой клинике и в этой палате, но не может точно припомнить, когда и при каких обстоятельствах это происходило.

От чего зависит формирование парамнезий? Прежде всего, их возникновение связывают с ослаблением или нарушением деятельности лобных долей вследствие возрастных изменений, черепно-мозговых травм, кровоизлияний или просто незрелости фронтальной зоны мозга, характерной для раннего детского возраста2. Существуют также данные, показывающие, что в нарушениях памяти могут играть роль дисфункции других мозговых структур: височной и префронтальной коры3, гиппокампа4 и др.

К возникновению ложных или искаженных воспоминаний могут также приводить некоторые психические заболевания – например, эхомнезии являются частью симптоматики при шизофрении5, – или даже сильная усталость – например, при хронической нехватке сна6.

Было, но не так. Ошибки памяти

Вторая причина, по которой мы можем помнить вовсе не то, что было на самом деле – «memory biases», или «ошибки памяти» – когнитивные искажения, связанные с влиянием физиологических и психологических факторов на содержание или воспроизведение когда-то усвоенной информации7.

Какие бывают ошибки памяти? К их числу относят:

- ретроактивную интерференцию – искажение воспоминаний под влиянием информации, полученной позже – например, утверждение свидетеля, что он видел нож в руках нападавшего, хотя о факте применения ножа он узнал только в ходе следственных действий;

- эффект телескопа – искажение временной перспективы памяти, при котором события, произошедшие в далеком прошлом, кажутся относительно недавними, а недавние события представляются удаленными по времени – например, оценка пожилым человеком событий его юности: «Это происходило как будто вчера»;

- иллюзию постоянства – воспоминание о прошлом поведении или убеждениях человека как о «таких же, как сейчас», несмотря на их реальную перемену – например, когда теща отзывается о бывшем зяте, бросившем ее дочь: «Он с самого начала вел себя как подлец!», даже если в начале знакомства он проявлял себя вполне достойно;

- эгоцентрическое искажение – приписывание самому себе в прошлом больших успехов и достоинств, чем они были на самом деле – например, когда отец, когда-то еле-еле окончивший школу, уверяет сына, что учился «почти на одни пятерки».

Ищем причины

Существует несколько теорий, призванных объяснить, как появляются искажения и ошибки памяти – как происходит возникновение ложных или искаженных воспоминаний.

Теория нейронного следа

Теория нейронного следа рассматривает психофизиологические корреляты памяти – так называемые энграммы8. Энграмма представляет собой серию молекулярных изменений, в результате которых укрепляется связь между определенной последовательностью нейронов в коре головного мозга. Эта связь лежит в основе механизма ассоциаций: при возбуждении одного из нейронов происходит «привычная» активация всей цепочки, составляющей нейронный след – так, при взгляде на фотографию известного певца человек «прокручивает» в голове его песню. Если взаимосвязь между участками коры, «отвечающая» за то или иное воспоминание, нарушается – это может происходить в результате травмы или «наложения» более поздней ассоциации – нейронный след «запутывается», что приводит к искажению или утрате воспоминаний.

Психоаналитическая теория

Психоаналитическая теория объясняет возникновение измененных воспоминаний механизмом психологических защит, т.е. бессознательной адаптации психики к травмирующему воздействию9. С точки зрения классического психоанализа, существует несколько основных типов таких защит: рационализация, замещение, проекция, сублимация, регрессия или отрицание. Их общая суть – изменение восприятия реальности, в том числе в прошлом, таким образом, чтобы уберечь психику от разрушительного внутреннего конфликта между, особенно при сильном эмоциональном потрясении. Так, ребенок, подвергшийся насилию со стороны отца, в более взрослом возрасте «подменяет» реальное воспоминание сконструированным образом заботливого родителя.

Гештальт-теория

Гештальт-теория обращает особенное внимание на структурировании материала, составляющего основу воспоминаний10. Согласно этому подходу, человек старается найти максимально понятную и логичную, с его точки зрения, взаимосвязь между запоминаемыми объектами: событиями, фактами, людьми и т. д. В тех случаях, когда эта связь не подтверждается, воспоминания «подстраиваются» под внутреннюю логику субъекта: например, человек, проявивший агрессию в адрес более слабого, утверждает, что жертва «спровоцировала» его своим поведением, и даже при наличии доказательств не соглашается, что эта «провокация» существовала только в его воображении.

Кроме того, существует целая серия работ, доказывающих, что способности к запоминанию и корректному воспроизведению информации значительно снижаются в ситуации острого или хронического стресса, при депрессивных и тревожных расстройствах и т.д.11 Исследователи связывают такие искажения и ошибки памяти со сложным и еще не до конца изученным комплексом физиологических, психологических и социальных процессов.

Разбираемся со следствиями

Что же делать с тем фактом, что ошибки памяти регулярно возникают, память может нас подвести – и это, в общем-то является нормой ее функционирования? Попробуем выделить самые важные шаги:

- Определить приоритеты.

На самом деле, далеко не вся информация, хранящаяся у нас «в голове», нуждается в точном и детальном воспроизведении. Нет ничего плохого в том, чтобы слегка приукрасить, скажем, романтические воспоминания о знакомстве с будущим супругом – а вот содержание важных деловых переговоров лучше помнить максимально подробно. - Использовать внешние опоры.

Для точной фиксации нужной информации можно использовать самые разные средства: мнемотехники (специальные приемы, позволяющие структурировать сложную в восприятии информацию в виде рифмованной фразы или яркого образа), аудио- и видеозапись, заметки в блокноте или в мобильном приложении. Все это позволяет «освежить» воспоминания в тот момент, когда они понадобятся, в первоначальном виде. - Тренировать мыслительные навыки.

Регулярные, но при этом не запредельные умственные нагрузки – отличный способ профилактики «возрастной» забывчивости. Их содержание зависит от интересов и приоритетов самого человека: кому-то нравится решать на досуге шахматные задачи, кому-то – изучать новые языки, а для кого-то научное или техническое творчество и вовсе является профессией. Важно, однако, помнить, что длительное напряжение без отдыха чревато прямо противоположным результатом: «перегруженный» рабочими задачами мозг включает механизм «запредельного торможения», которое резко снижает способности к концентрации внимания, запоминанию и воспроизведению информации.

Впрочем, польза перечисленных действий не только в том, чтобы защитить воспоминания от когнитивных искажений. Умение выделять важное, структурировать информацию и фиксировать ее вспомогательными средствами и грамотно распределять время между физической и умственной активностью и отдыхом помогает предотвратить ошибки памяти, оставаться не только в твердой памяти, но и в здравом уме. А это, согласитесь, редко бывает лишним.

Ссылки:

- Жариков Н. М., Тюльпин Ю. Г. Психиатрия: Учебник. – М.: Медицинское информационное агентство, 2012. – 832 с.

- Schacter D. L., Kagan J., Leichtman M. D. True and false memories in children and adults: A cognitive neuroscience perspective // Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. – 1995. – V. 1. – № 2. – P. 411-428.

- Devitt A. L., Schacter D. L. False memories with age: Neural and cognitive underpinnings // Neuropsychologia. – 2016. – Т. 91. – С. 346-359.

- Вартанов А. В. и др. Память человека и анатомические особенности гиппокампа // Вестник Московского университета. Серия 14. Психология. – 2009. – № 4. – С. 3-16.

- Международная классификация болезней МКБ-10. Электронная версия. – URL: www.mkb10.ru

- Frenda S. J. et al. Sleep deprivation and false memories // Psychological Science. – 2014. – V. 25. – № 9. – P. 1674-1681.

- Макрэйни Д. Психология глупостей. Заблуждения, которые мешают нам жить. – М.: Альпина Бизнес Букс, 2012. – 344 с.

- Основы психофизиологии: учебник / Отв. ред. Ю.И. Александров. – М.: Инфра-М, 1997. – 349 с.

- Белов В. Г., Бирюкова Г. М., Федоренко В. В. Психологическая защита и ее роль в процессе формирования адаптационной системы человека // Гуманизация образования. – 2009. – №. 3. – С. 66-72.

- Декатова К.И. Роль гештальта в процессе смыслообразования знаков косвенно-производной номинации // Acta Linguistica. – 2007. – Т. 1. – № 1. – С. 63-68.

- Dalgleish T. et al. Patterns of processing bias for emotional information across clinical disorders: A comparison of attention, memory, and prospective cognition in children and adolescents with depression, generalized anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder // Journal of clinical child and adolescent psychology. – 2003. – V. 32. – № 1. – P. 10-21.

Похожее

Полезно? Поделись статьей в Вконтакте или Фейсбук в 1 клик!

Наталья Ульянова

кандидат психологических наук, педагог-психолог, игротерапевт

Разбираемся, зачем мозг создает некорректные воспоминания и можно ли с этим справиться

Содержание:

- Что это

- Виды

- Признаки

- Причины

- Диагностика

- Лечение

Что такое конфабуляция

Конфабуляция — это когнитивная ошибка, при которой пробелы в памяти человека бессознательно заполняются выдуманной, неверно истолкованной или искаженной информацией. Когда человек подвергается конфабуляции, он путает воображаемые вещи с реальными воспоминаниями. Важно отметить, что при этом люди не лгут, когда упорно рассказывают о том, чего не было. Просто они уверены в правдивости своей памяти, даже если доказательства говорят не в их пользу.

Виды конфабуляции и у кого она встречается

Через конфабуляцию сознание пытается скрыть тот факт, что какая-то часть информации пропала из памяти, и генерирует вместо нее ложное воспоминание. Конфабуляция бывает двух видов.

- Спровоцированная конфабуляция возникает, когда человек придумывает ложную историю в ответ на конкретный вопрос. Этот тип конфабуляции наиболее распространен у людей с деменцией или амнезией.

- Спонтанная конфабуляция встречается реже. Она возникает, когда человек рассказывает ложную историю просто так, без какой-либо мотивации или запроса извне.

Конфабуляция часто связана с нарушениями памяти, черепно-мозговыми травмами или заболеваниями, а также с психическими расстройствами. Кроме того, на ее возникновение может влиять злоупотребление наркотиками. Однако она также наблюдается и у здоровых ментально и физически людей.

Признаки конфабуляции

Существует несколько общих характеристик конфабуляции.

- Отсутствие осознания того, что воспоминание искажено. Когда человеку указывают на ошибки, его не беспокоит очевидная нереальность его рассказа.

- Отсутствие попытки обмануть. У человека нет скрытой мотивации для неправильного запоминания информации.

- Ложная история взята из памяти. Основой для неверно запомненной информации обычно служат опыт и мысли человека.

- Ложная история может быть любой. Вызванная конфабуляцией история может быть как абсолютно последовательной и правдоподобной, так и крайне странной, нереалистичной.

Причины возникновения конфабуляции

Конфабуляция может образоваться просто так. Не существует конкретной области мозга, которая за нее отвечает, однако с ней связывали повреждение лобной доли (играет важную роль в формировании воспоминаний) и мозолистого тела (ключевая роль в зрительной и слуховой памяти). К конфабуляции также могут привести:

- синдром Вернике-Корсакова, неврологическое расстройство, связанное с острым дефицитом витамина В1, который обычно вызывается хроническим алкоголизмом;

- болезнь Альцгеймера, форма деменции, которая связана с потерей памяти, когнитивными нарушениями, языковыми и другими неврологическими проблемами;

- черепно-мозговая травма, повреждение определенных областей мозга;

- шизофрения, психическое расстройство, которое влияет на способность человека распознавать и понимать реальность, вызывая аномальные переживания и поведение.

Как выявить конфабуляцию

Конфабуляцию бывает трудно распознать. Это способно усложнить диагностику психического здоровья и состояния памяти. Для ее определения специалисты используют несколько способов.

- Задавать вопросы. В процессе интервью врач задает вопросы об опыте, симптомах или истории болезни человека. Если будут отмечены несоответствия или другие очевидные примеры конфабуляции, человека могут направить к неврологу для дальнейшего обследования.

- Расспросить близких. Семья и друзья также могут предоставить информацию о конфабуляции, поскольку специалистам бывает очень трудно ее распознать. Во многих случаях только близкие, живущие с человеком или проводящие с ним много времени, могут заметить, что что-то не так.

- Проверить с помощью нескольких источников. При подозрении на конфабуляцию врач может задавать дополнительные вопросы, а затем проверить полученную информацию с помощью других источников.

Лечение конфабуляции

Исследования показывают, что конфабуляция трудно поддается лечению. Рекомендуемый подход зависит от основной причины возникновения (если возможно ее определить). Например, споры о достоверности воспоминаний у людей с деменцией не имеют смысла. Куда лучше работают принятие и поддержка. В некоторых случаях с конфабуляцией можно бороться с помощью психотерапевтических и когнитивно-поведенческих методов лечения. Они дают возможность людям лучше осознать неточности в своих воспоминаниях.

Результаты исследования 2017 года подтверждают необходимость нейропсихологического лечения конфабуляции у людей, которые перенесли травму головного мозга. Ученые попросили участников выполнить задание на запоминание, а затем продемонстрировали их ошибки. После этого добровольцам давали конкретные указания быть внимательнее к материалу и обдумывать свои ответы. Результаты исследования показали, что этот подход был эффективен для снижения уровня конфабуляции.

Memory gaps and errors refer to the incorrect recall, or complete loss, of information in the memory system for a specific detail and/or event. Memory errors may include remembering events that never occurred, or remembering them differently from the way they actually happened.[1] These errors or gaps can occur due to a number of different reasons, including the emotional involvement in the situation, expectations and environmental changes. As the retention interval between encoding and retrieval of the memory lengthens, there is an increase in both the amount that is forgotten, and the likelihood of a memory error occurring.

Overview[edit]

There are several different types of memory errors, in which people may inaccurately recall details of events that did not occur, or they may simply misattribute the source of a memory. In other instances, imagination of a certain event can create confidence that such an event actually occurred. Causes of such memory errors may be due to certain cognitive factors, such as spreading activation, or to physiological factors, including brain damage, age or emotional factors. Furthermore, memory errors have been reported in individuals with schizophrenia and depression. The consequences of memory errors can have significant implications. Two main areas of concern regarding memory errors are in eyewitness testimony and cases of child abuse.

Types of memory errors[edit]

Blocking[edit]

The feeling that a person gets when they know the information, but can not remember a specific detail, like an individual’s name or the name of a place is described as the «tip-of-the-tongue» experience. The tip-of-the-tongue experience is a classic example of blocking, which is a failure to retrieve information that is available in memory even though you are trying to produce it.[2] The information you are trying to remember has been encoded and stored, and a cue is available that would usually trigger its recollection.[2] The information has not faded from memory and a person is not forgetting to retrieve the information.[2] What a person is experiencing is a complete retrieval failure, which makes blocking especially frustrating.[2] Blocking occurs especially often for the names of people and places, because their links to related concepts and knowledge are weaker than for common names.[2] The experience of blocking occurs more often as we get older; this «tip of the tongue» experience is a common complaint amongst 60- and 70-year-olds.[2]

Transience[edit]

Transience refers to forgetting what occurs with the passage of time.[3] Transience occurs during the storage phase of memory, after an experience has been encoded and before it is retrieved.[3] As time passes, the quality of our memory also changes, deteriorating from specific to more general.[3] German philosopher named Hermann Ebbinghaus decided to measure his own memory for lists of nonsense syllables at various times after studying them. He decided to draw out a curve of his forgetting pattern over time. He realized that there is a rapid drop-off in retention during the first tests and there is a slower rate of forgetting later on.[3] Therefore, transience denotes the gradual change of a specific knowledge or idea into more general memories.[4]

Absentmindedness[edit]

Absentmindedness is a gap in attention which causes memory failure. In this situation the information does not disappear from memory, it can later be recalled. But the lack of attention at a specific moment prevents the information from being recalled at that specific moment. A common cause of absentmindedness is a lack of attention.[clarification needed] Attention is vital to encoding information in long-term memory. Without proper attention, material is much less likely to be stored properly and recalled later.[5] When attention is divided, less activity in the lower left frontal lobe diminishes the ability for elaborative memory encoding to take place, and results in absentminded forgetting. More recent research has shown that divided attention also leads to less hippocampal involvement in encoding.[5] A common example of absentmindedness is not remembering to carry out actions that had been planned to be done in the future, for example, picking up grocery items, and remembering times of meetings.[6]

False memories[edit]

False memories, sometimes referred to as confabulation, refer to the recollection of inaccurate details of an event, or recollection of a whole event that never occurred. Studies investigating this memory error have been able to successfully implant memories among participants that never existed, such as being lost in a mall as a child (termed the lost in the mall technique) or spilling a bowl of punch at a wedding reception.[7] In this case, false memories were implanted among participants by their family members who claimed that the event had happened. This evidence demonstrates the possibility of implanting false memories on individuals by leading them to remember such events that never occurred. This memory error can be particularly worrisome in judicial settings, in which witnesses may have false recollections of a crime after it has happened, especially when told by others that particular things may have happened which did not.[8] Another area of concern regarding false memories is in cases of child abuse.

Problem of bias[edit]

The problem of bias, which is the distorting influences of present knowledge, beliefs, and feelings on recollection of previous experiences.[9] Sometimes what people remember from their past says less about what actually happened than about what they personally believe, feel, and the knowledge they have acquired at the present time.[9] An individual’s current moods can bias their memory recall, researchers have found.[9] There are three types of memory biases, consistency bias, change bias and egocentric bias.[9] Consistency bias is the bias to reconstruct the past to fit the present.[9] Change bias is the tendency to exaggerate differences between what we feel or believe in the present and what we previously felt or believed in the past.[9] Egocentric bias is a form of change bias, the tendency to exaggerate the change between the past and the present in order to make ourselves look good in any given situation.[9]

Misinformation effect[edit]

The misinformation effect refers to the change in memory due to the presentation of information that is relevant to the target memory, such as leading questions or suggestions.[10] Memories are likely to be altered when questions are worded differently or when inaccurate information is presented. For example, in one experiment participants watched a video of an automobile accident and were then asked questions regarding the accident. When asked how fast the automobiles were driving when they smashed into each other, the speed estimate was higher than when asked how fast the automobiles were driving when they hit, bumped or collided into each other. Similarly, participants were more likely to report there being shattered glass present when the word smashed was used instead of other verbs.[11] Evidently, memory recollection can be altered with misleading information after the event.

Source confusion[edit]

Source confusion or unconscious transference,[12] involves the misattribution of the source of a memory. For instance, an individual may recall seeing an event in person when in reality they only witnessed the event on television.[12] Ultimately, the individual has an inability to remember the source of information in which the content and the source become dissociated. This may be more likely for more distant memories, such as childhood memories.[7] In more severe cases of source confusion, you can take fictional stories you heard from when you were younger and assimilated these stories being your childhood. For example, say your father told you stories about his life when he was a child every night before you went to sleep when you were a child. When you grow up, you might mistakenly remember these stories your dad told you as your own and integrate them into your childhood memories.[13]

Imagination inflation[edit]

Imagination inflation refers to when a person remembers details of a memory that are exaggerated versions of the actual event or remember an entire memory that never occurred due to the act of imagination.[14] That is, when one imagines an event occurring, their confidence that this event actually did occur increases. One reason for this may be due to the act of imagination increasing the familiarity of the event. When the event seems more familiar, it may become more likely for people to report it actually occurring. For instance, in an experiment participants were asked to imagine playing inside and then running outside toward a window, falling and breaking it, while other participants did not imagine anything. Participants who had imagined this scenario reported an increased level of confidence that the event had actually happened in comparison to those who did not imagine the event.[7] This error can be caused simply by imagining an event.

Deese–Roediger–McDermott (DRM) paradigm[edit]

Deese-Roediger-McDermott paradigm refers to the incorrect recall of features of an event that were not actually present, due to the features being related to a common theme.[15] This paradigm has been demonstrated with the use of word lists and subsequent recognition tests. For example, experiments have shown that if a research participant is presented with the words: bed rest awake tired dream wake snooze snore nap yawn drowsy, there is a high likelihood that the participant will falsely recall that the word sleep was in the list of words. These results show a significant illusion in memory, in which people remember items that were never presented simply due to their relation with other items in a common theme.[1]

Schematic errors[edit]

Schematic errors refer to the use of a schema to help reconstruct parts of an experience that cannot be remembered. This may include parts of the schema that did not actually take place, or aspects of a schema that are stereotypical of an event.[16] Schemas can be described as mental guidelines (scripts) for events that are encountered in daily life.[16] For example, when going to the gas station, there is a general pattern of how things will occur (i.e. turn car off, get out of car, open gas tank, punch the gas button, put nozzle into the tank, fill up the tank, put the nozzle back, close the tank, pay, turn car on, leave). Schemas make the world more predictable, allowing expectations to be formed of how things will enfold and to take note of things that happen out of context.[16] However, schemas also allow for memory errors, in that if certain aspects of a scene or event are missing from memory, people may incorrectly remember having actually seen or experienced them because they are usually a regular aspect of the schema. For example, an individual may not remember paying the waiter, but may believe they have done so, as this is a regular step in the script of going to a restaurant. Similarly, a person may recall seeing a fridge in a picture of a kitchen, even if one was not actually depicted due to existing schemas which suggest that kitchens almost always contain a fridge.[16]

Intrusion errors[edit]

Intrusion errors refer to when information that is related to the theme of a certain memory, but was not actually a part of the original episode, become associated with the event.[17] This makes it difficult to distinguish which elements are in fact part of the original memory. One idea regarding how intrusion errors work is due to a lack of recall inhibition, which allows irrelevant information to be brought to awareness while attempting to remember.[18] Another possible explanation is that intrusion errors result from a lack of new context integration into a viable memory trace, or into an already existing memory trace that is related to the appropriate memory.[18] More explanations involve the temporal aspect of recall, meaning that as the time difference between the study periods of different lists approaches zero, the amount of intrusions between the lists tends to increase,[19] the semantic aspect, meaning that the list of target words may have induced a false recall of non-target words that happen to have a similar or same meaning as the targets,[20] and the similarity aspect, for example subjects who were given list of letters to recall were likely to replace target vowels with non-target vowels.[21]

Intrusion errors can be divided into two categories. The first are known as extra-list errors, which occur when incorrect and non-related items are recalled, and were not part of the word study list.[18] These types of intrusion errors often follow the DRM Paradigm effects, in which the incorrectly recalled items are often thematically related to the study list one is attempting to recall from. Another pattern for extra-list intrusions would be an acoustic similarity pattern, this pattern states that targets that have a similar sound to non-targets may be replaced with those non-targets in recall.[22] One major type of extra-list intrusions is called the «Prior-List Intrusion» (PLI), a PLI occurs when targets from previously studied lists are recalled instead of the targets in the current list. PLIs often follow under the temporal aspect of intrusions in that since they were recalled recently they have a high chance of being recalled now.[19] The second type of intrusion error is known as intra-list errors, which is similar to extra-list errors, except it refers to irrelevant recall for items that were on the word study list.[18] Although these two categories of intrusion errors are based on word list studies in laboratories, the concepts can be extrapolated to real-life situations. Also, the same three factors that play a critical role in correct recall (recency, temporal association and semantic relatedness) play a role in intrusions as well.[19]

Time-slice errors[edit]

Time-slice errors occur when a correct event is in fact recalled; however the event that was asked to be recalled is not the one that is recalled. In other words, the timing of events is incorrectly remembered.[23] As discovered in a study by Brewer (1988), often the event or event details that are recalled occurred within a short time proximity to the memory required to be recalled.[23] There are three possible theories as to why time-slice errors occur. First, they may be a form of interference, in which the memory information from one time impairs the recall of information from a different time.[24] (see interference below). A second theory is that intrusion errors may be responsible, in that memories revolving around a similar time period thus share a common theme, and memories of various points of time within that larger time period become mixed with each other and intrude on each other’s recall. Last, the recall of memories often have holes due to forgotten details. Thus, individuals may be using a script (see schema errors) to help fill in these holes with general knowledge of what they know happened around this time. Since scripts are a time-based knowledge structure, which puts details of a memory in sequence to make it easier to understand, time-slice errors can occur if a detail is mistakenly placed in the wrong sequence.[24]

Personal life effects[edit]

Personal life effects refer to the recall and belief in events as declared by family members or friends for having actually happened.[25] Personal life effects are largely based on suggestive influences from external sources, such as family members or a therapist.[7] Other influential sources may include media or literature stories which involve details that are believed to have been experienced or witnessed, such as a natural disaster close to where one resides, or a situation that is common and could have occurred, such as getting lost as a child. Personal life effects are most powerful when claimed to be true by a family member, and even more powerful when a secondary source confirms the event having happened.[7]

Personal life effects are believed to be a form of source confusion, in which the individual cannot recall where the memory is coming from.[26] Therefore, without being able to confirm the source of the memory, the individual may accept the false memory as true. Three factors may be responsible for the implantation of false autobiographical memories. The first factor is time. As time passes, memories fade. Therefore, source confusion may result due to time delay.[7] The second factor is the imagination inflation effect. As the amount of imagination increases, so does one’s familiarity for the contents of the imagination. Thus, source confusion may also occur due to the individual confusing the source of the memory for being true, when in fact it was imaginary.[26] Lastly, social pressure to recall the memory may affect the individual’s belief in the false memory. For example, with increase in pressure, the individual may lower their criteria for validating a memory, and come to accept a false memory for being true.[26] Personal life effects can be extremely crucial to recognize in cases of recovered memories, especially those of abuse, in which the individual may have been led to believe they had been abused as a child by a therapist during psychological therapy, when in fact they had not been. Personal life effects can also be important in witness testimonies, in which suggestions from authorities may incorrectly implant memories regarding witnesses a particular detail about a crime (see the Childhood Abuse and Eye Witness Testimony sections below).

Memory error relating to food[edit]

In a study done by J. Mojet and E.P. Köster, participants were asked to have a drink, yoghurt, and some biscuits for breakfast. A few hours later, they were asked to identify and the items they had during breakfast out of five variations of the drinks, yoghurts, and biscuits. The results showed that participants remember the texture of the foods much better than for fatty content, although they could discern the difference of both among the different items. Participants were also most certain about foods that they did not have during breakfast, but were the least certain about foods that they said were in their breakfast and about foods that were in their breakfast but were not recognized. This suggests that incidental and implicit memory for foods are more focused on discerning new and potentially unsafe food rather than remembering the details of familiar foods.[27]

Causes[edit]

Cognitive factors[edit]

Spreading activation[edit]

One theory on how memory works is through a concept called spreading activation. Spreading activation refers to the firing of connected nodes in associated memory links.[28] The theory states that memory is organized in a theoretical web of associated ideas and related features. Each feature, or node, is connected to related features or ideas, which in turn are themselves connected to other related nodes.[29]

Spreading activation can also demonstrate how memory errors may occur. As the network of memory associations increases in the number of connections–the connection density–the likelihood of memory gaps and errors occurring also increases. Put simply, the amount of activation a secondary connection receives depends on how many connections the initial node has associated with it. This is because the initial node must divide the amount of activation it spreads to related nodes by the number of connecting nodes it is associated with. If node 1 has three connecting nodes, and node 2 has 15 connecting nodes, the three connecting nodes from node 1 will receive greater activation levels (the activation level is divided less) than for the 15 connecting nodes from node 2, and the components of these nodes will be more easily brought to mind. What this means is that, with more connections a node has, the more difficulty there is bringing to mind one of its connecting features.[30] This can lead to memory errors, in that if the connection density is so great that there is not enough activation reaching the secondary nodes, then the person may not recall a target memory that is actually present, and a memory error occurs.

Activation levels to secondary nodes is also determined by the strength of the association to the primary node.[28] Some connections have greater association with the primary node (e.g. fire truck and fire or red, versus fire truck and hose or Dalmatian), and thus will receive a greater portion of the divided activation than less associated connections. Thus, associations that receive less activation will be out-competed by associations with stronger connections, and may fail to be brought into awareness, again causing a memory error.

Connection density[edit]

The connection densities, or neighbourhood densities[31] of memory arrangements help distinguish which elements are a part of, or related to, the target memory. As the density of neural networks increases, the number of retrieval cues (associated nodes) also increases, which may allow for enhanced memory of the event.[30] However, too many connections can inhibit memory in two ways. First, as described under the sub-section Spreading Activation, the total activation being spread from node 1 to connecting nodes is divided by the number of connections. With a greater number of connections, each connecting node receives less activation, which may result in too little activation for the memory cue to be brought to awareness. Connection strength, in which more strongly connected associations receive more activation than less-related associations, may also prevent specific connections from being brought to awareness due to being out-competed by the stronger associations.[31] Second, with more connections branching from various other nodes, there is a greater probability of linking associated connections of different memories together (transplant errors) so that memory errors occur and incorrect features are recalled.

Retrieval cues[edit]

A retrieval cue is a type of hint that can be used to evoke a memory that has been stored but cannot be recalled. Retrieval cues work by selecting traces or associations in memory that contain specific content. With regards to the theory of spreading activation, retrieval cues use associated nodes to help activate a specific or target node.[32] When no cues are available, recall is greatly reduced, leading to forgetting and possible memory errors. This is called retrieval failure, or cue-dependent forgetting.

Retrieval cues can be divided into two subsets, although they are by no means used independent of each other. The first are called feature cues, in which information of the content of the original memory, or related content, is used to aid recall.[32] The second category is context cues, in which information based on the specific context (environment) in which the memory or learning occurred is used to aid recall.[32]

Although retrieval cues are usually helpful in helping to remember something, they can produce memory errors in three ways. First, incorrect cues can be used, leading to recall of an incorrect memory. Second, although the correct retrieval cues may be used, they may still produce an incorrect memory. This is likely to occur with high connection densities, in which the incorrect (but associated) node was activated and thus recalled, instead of the target memory. Third, the retrieval cue chosen may be correct and associated with the target memory, but it may not have a strong connection to the target memory, and thus may not produce enough activation to produce the target memory.

Encoding specificity[edit]

Encoding specificity is when retrieval is successful to the extent that the retrieval cues used to help recall, match the cues the individual used during learning or encoding.[33] Memory errors due to encoding specificity means that the memory is likely not forgotten, however, the specific cues used during encoding the primary event are now unavailable to help remember the event. The cues used during encoding are dependent on the environment of the individual at the time the memory occurred. In context-dependent memory, recall is based on the difference between the encoding and recall environments.[34] Recall for items learned in a particular context is better when recall occurs in the same place as when the initial memory occurred. This is why it is sometimes useful to “return to the scene of the crime” to help witnesses remember details of a crime, or for explaining why going to a specific location such as a residence or community setting, may lead to becoming flooded with memories of things that happened in that context. Recall can also depend on state-dependency, or the conditions of one’s internal environment, at both the time of the event and of recall.[35] For example, if intoxicated at the time the memory actually occurred, recall for details of the event is greater when recalling while intoxicated. Associated with state-dependency, recall can also depend on mood-dependency, in which recall is greater when the mood for when the memory occurred matches the mood during recall.[23] These specific dependencies are based on the fact that the cues used during the initial event can be specific to the context or state one was in. In other words, various features of the environment (both internal and external) can be used to help encode the memory, and thus become retrieval cues. However, if the context or state changes at the time of recall, these cues may no longer be available, and thus recall is hindered.

Transfer-appropriate processing[edit]

Memory errors can also depend on the method of encoding used when initially experiencing or learning information, known as transfer-appropriate processing.[36] Encoding processes can occur at three levels: visual form (the letters that make up a word), phonology (the sound of a word), and semantics (the meaning of the word or sentence). With relation to memory errors, the level of processing at the time of encoding and at the time of recall should be the same.[37] Although semantic processing generally produces greater recall that shallower levels of processing, a study by Morris et al. demonstrated that what might be the key factor to greater recall is transfer-appropriate processing–when the level of processing at the original memory/learning time matches the level of processing used to help recall. In other words, if learning occurred by rhyming the target words to other words, then recall is best if testing is also at the phonological level of processing, such as a rhyming recognition test. Thus, memory errors can occur when the levels of processing between encoding and recall do not match.[37]

Interference[edit]

Interference occurs when specific information inhibits learning and /or recall for a specific memory.[38] There are two forms of interference. First, proactive interference has to do with difficulty in learning new material based on the inability to override information from older memories.[39] In such cases, retrieval cues continue to be associated and aimed at recalling previously learned information, affecting the recall of new material. Retroactive interference is the opposite of proactive interference, in which there is difficulty in the recall of previously learned information based on the interference of newly acquired information. In this case, retrieval cues are associated with the new information and not the older memory.[40] thus affecting recall of older material. Interference of either form can produce memory errors, in which there is interference with the recall of material. In other words, previously used retrieval cues are no longer associated with prior memories, and thus memory confusion or even an inability to recall the memory can occur.

Physiological factors[edit]

Brain damage[edit]

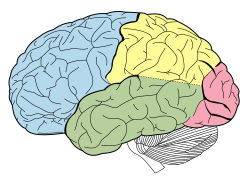

| Lobes of the human brain |

|---|

|

Frontal lobe Temporal lobe Parietal lobe Occipital |

| Damage in the temporal lobe (green) and frontal lobe (blue) are associated with resulting memory errors |

Neuroimaging studies have provided evidence for links between brain damage and memory errors. Brain areas implicated include the frontal lobe and medial-temporal regions of the brain. Such damage may result in significant confabulations and source confusion.[8]

The prefrontal cortex is in charge of making heuristic judgments and systematic judgments, which involve analyzing the qualities of memories and the retrieval and evaluation of supporting or disconfirming information.[8] Thus, if the frontal region is damaged, these abilities will be impaired and memories may not be retrieved or evaluated correctly. For example, one patient who suffered frontal lobe damage after an automobile accident reported memories of the support his family provided for him after the accident, which in reality, was false.[41]

The temporal region of the brain contains the hippocampus, which plays a significant role in memory.[42] Thus, damage in this region may impair the function of this brain structure and result in memory problems.

Age[edit]

Studies have shown that the likelihood of memory errors occurring increases as age increases. Possible reasons for this are increased source confusion for the event and findings that older persons have decreased levels of processing when first presented with new information.[43][44] Source confusion refers to the inability to distinguish how one came upon different information. Older individuals can become confused with where they learnt information (e.g. TV, radio, newspaper, word of mouth, etc.), who presented them with the information (e.g. which of two experimenters presented them with facts and which presented them with irrelevant information), and whether the information came from an imagined source, and is thus not factual, or a real world source.[44] This in itself is a form of memory error but can also create larger memory errors. When an older individual is confused whether the information is factual or was imagined they can begin to accept imagined memories as real and thus begin to rely on new false information.[44]

Levels of processing refers to the manner in which someone encodes information into their memory and how deeply it is encoded.[44] There are three different levels of processing ranging from shallow to deep, deep being stored in long-term memory for a longer period and thus better remembered. The three levels are; visual form, being the shallowest form, phonology, being a medium level of processing, and semantics (meaning), which is the deepest form of processing.[44] The visual form of processing relies on the ability to see information and break it down into its components (e.g. see the word «dog», composed D, O, and G). Phonology relies on creating links to information through sound such as cues and tricks for memory (e.g. Dog rhymes with Fog).[44] Finally, semantics refer to the creation of meaning behind information such as adding detail to allow the information to create links throughout our memory with other memories and thus be held in long-term memory for a longer period (e.g. A dog is a four-legged pet that often chases cats and chews on bones).[44] Older individuals often begin to lose the quick ability to add meaning to new information, which leads to shallower processing and easier forgetting of the information gained.[44] Both of these possible factors can decrease the validity of the memory due to retrieval for details of the event being more difficult to perform. This leads to details of memories being confused with others or lost completely, which lead to many errors in recall of a memory.

Emotion[edit]

The emotional impact of an event can have a direct impact on how the memory is first encoded, how it is later recalled, and what details of the event are accurately recalled. Highly emotional events tend to be recalled easily due to their emotional impact,[45] as well as their distinctiveness relative to other memories (highly emotional events do not occur on a regular basis, and thus are easily separated from other events that are more commonly met). Emotional events may affect memory not only because of their distinctiveness, but also because of their arousal on the individual.[46] Studies have found that prime or central features of such highly emotional events tend to be accurately recalled, whereas subtle details of the events are not remembered, or are remembered with vague consistency. Memory errors related to highly emotional events are influenced in ways such as:

- Whether the event was positive or negative in nature — The nature of the event can affect memory, negative events tend to be remembered with greater accuracy than positive events.[23]

- Implicit theories of consistency and change — This term was coined by Ross (1989), and is used to describe the phenomena of memory change based on the belief of how the person felt at the time of the event compared to their current feelings about it.[23] In other words, the memory of one’s emotion towards an event can change depending on their current emotional state toward the same event. If a person believes their feelings at both times continue to be the same, then the current emotion to «remember» how they felt about the event at a previous time is used. If feelings are believed to have changed, then recall of the emotional involvement in the past event is adjusted to the current feelings.

- Intrusion errors — This term refers to the inclusion of details that may have been commonly experienced in the event, but not by the individual. For example, in the September 11 terrorist attacks, many people may state that they remember hearing about the attacks on the television news, as this was a common way of finding out this information, whereas they may have actually heard about it from a neighbour or on the radio.[47]

- Mood-congruency — Items/events are better recalled when the mood of the individual at the time of the event and the time of recall are the same. Thus, if the mood at the time of recall does not match the mood experienced at the time the event occurred, there is an increased chance that complete recall will be affected/interrupted.[48]

Memory errors in Abnormal Psychology[edit]

Abnormal psychology is the branch of psychology that studies unusual patterns of behavior, emotion and thought, which may or may not be understood as a mental disorder. Memory errors can commonly be found in types of abnormal psychology such as Alzheimer’s disease, depression, and schizophrenia.

Alzheimer’s disease[edit]

Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by progressive memory impairment and decline, usually beginning short-term memory.[49] As it is a progressive disease, Alzheimer’s usually begins with memory errors before proceeding to long-term memory stores. One form of memory error occurs in contrast to the theory of retrieval cues in being a reason for the occurrence of memory errors. As noted above, memory errors may be due to the lack of cues that can trigger a memory trace and bring it to awareness. However, studies have shown that the opposite may be true for patients with Alzheimer’s, such that cues may actually decrease perform on

priming tasks.[50] Patients also demonstrate errors known as misattribution errors, otherwise known as source confusion. However, studies show that these misattribution errors are dependent on whether the task is a familiarity or recollection task.[51]

Although patients tend to exhibit a higher level of false recognitions than control groups,[52] researchers have shown that they may exhibit less false-recognition early in the test due to familiarity being slower to develop. However, the observation of increasing instances of misattribution errors can be seen once familiarity does occur.[51] This may be related to the retrieval cue speculation, in that familiar memories often contain cues we know, and thus may be the reason why familiarity can contribute to memory errors. Lastly, many studies have shown that Alzheimer’s patients commonly suffer from intrusion errors. Relative to the findings that retrieval cues may actually hurt recall performance, one study by Kramer et al. showed that intrusions are most commonly associated with cue-recall tasks.[53] This study suggests that cues may lead to intrusions because patients may have a difficult time distinguishing between cues and distractions,[53] which may help explain why cues increase memory errors in patients with Alzheimer’s. Since verbal intrusions are a common aspect of Alzheimer’s,[54] some researchers believe that this characteristic may be helpful in the diagnosis of the disease.[55]

Depression[edit]

Memory errors can occur in patients with depression or with depressive symptoms. Patients with depressive symptoms have a tendency to experience what is known as the negative triad, which is the perspective use of negative schemas and self-concepts to relate to the external world. Due to this negative triad, depressive patients have a tendency to have a much greater focus on, and recall for, negative details and events over positive ones. This may lead to memory errors related to the positive details of memories, impairing the accuracy or even complete recall of such memories. Depressed patients also experience deficits in psychomotor speed and in free recall of material both immediate and delayed. This suggests that material has been encoded but that patients are particularly impaired with regard to search and retrieval processes.[56] Diverse aspects of memory such as short-term memory, long-term memory, semantic memory and implicit memory, have been studied and linked to depression. Short-term memory, a temporary store for newly acquired information, seems to show no major impairments in the case of depressive patients who do seem to complain about poor concentration, which by itself can cause simple memory errors.[56]