Ссылка на философа, ученого, которому посвящена запись:

Трудности в определении бытия

1. Трудности обычной логики.

Философия не зря пытается размежеваться с логикой, которая конструирует понятия на основе референций к единичным вещам и их некоторым ограниченным комплексам. Такими понятиями оперирует не только обыденное сознание, так нелюбимое и презираемое Гегелем, но и частные науки. В свою очередь понятие о бытии не может иметь никаких прямых соответствий в пределах среды, непосредственно окружающей человека, иначе это будет уже понятие не о бытии едином и безусловном, а о некотором его частном случае, о бытии дробном, распавшемся на собственно бытие и понятие о нём. Можно, конечно, авторитетно утверждать, что бытие мысли само по себе условно и равнять её бытийный статус со статусом самого бытия неправомерно, из чего можно заключить, что всякие разнообразные атрибуты бытию приписывает не мысль человека, но сами эти атрибуты ему с необходимостью принадлежат. Только не надо при этом забывать, что любому атрибуту, приписываемому бытию, при хорошем старании можно противопоставить другой, противоположный или вложить в понятие этого атрибута совсем другой смысл. Вместе они могут добавить ещё больше пищи для дискуссий — что в таком знании может соответствовать действительности, а что только играм праздного воображения. Уже из этого простого факта следует также простой вывод: само по себе бытие никому ничем не обязано, а потому самодостаточно, но стоит только в безмятежной среде бытия появиться мысли человека, так сразу возникает хаос и смута, дробность и многообразие. А сама мысль человека, причём основательно осознанная и зафиксированная в действии, становиться не только фактором, провоцирующим эту дробность, но и самостоятельной частью бытия, действующей по своей собственной прихоти и стремящейся к ещё большему обособлению от него.

Гегель ясно узрел эти трудности в отношении определения бытия через его имя или, хотя бы, название. Он, пусть и не очень вразумительно, дал понять, что любое имя бытия может быть взято только из багажа обычных человеческих предпочтений, а значит, отягощено противостоящими друг другу человеческими смыслами. В таком знании о бытии нет единства, потому что это будет не столько знание о бытии, сколько набор противостоящих друг другу мнений о некоторых частях бытия, произвольно включённых в фокус внимания исследователя. Тем не менее, если в естественном человеческом любопытстве просматривается интерес к тому или иному объекту исследования или какой-либо его стороне и желание представить его в мысли, то разброс мнений об этом объекте не будет критическим для судьбы знания о нём, но всегда сможет помочь выйти на новый, ещё более высокий уровень его осмысления. Знание о таком бытии, дробном и многообразном, также естественным образом со временем может устаревать, но и это не трагедия — в любом случае почести уходящему поколению, честно выполнившему свой долг, будут оказаны. Но философия с необходимостью выпадает из этого алгоритма. Для неё основным вопросом является выбор — или она занимается единством как бытия, так и самого знания о нём, или она переходит в разряд шарлатанства, если с единством не дружит.

2. Смысл смысла.

Гегель увидел опасность для единого философского знания о едином бытии в односторонности мышления человека, привыкшего подразделять знание о бытии на частные аспекты рассмотрения бытия, которые могут быть оспорены и в свою очередь также раздроблены с целью, якобы, ещё более всестороннего изучения самого предмета рассмотрения. Любое единство и согласие в таком знании будет локальным и непостоянным, в силу ограниченности компетенции как отдельной частной науки о бытии, так и некоторой конкретной группы её представителей. Поэтому, согласно Гегелю, философия должна исходить из более высокого представления о логике.

По большому счёту, Гегель не предложил ничего нового. По его же словам, он взял схему мышления Платона, согласно которой никакое сознание, практикующее фигуративное мышление, не в состоянии приблизиться к пониманию истинного и всеобъемлющего единства как бытия, так и знания о нём. А единое знание о бытии и есть знание о бытии едином. Следовательно, надо отбросить все частные мнения о бытии, удалить из знания все частные смыслы и оставить только один смысл — смысл смысла, единство формы мысли и её содержания, некоторую первоначальную логическую матрицу, слитную с самим бытием и являющуюся, по сути, его действительным воплощением. Замысел поистине грандиозный, но в такой же степени и трудновыполнимый. Это какой же надо обладать силой ума, чтобы докопаться до такой матрицы? Но и это не самое трудное. Если даже подобное знание может быть получено от самого бытия, то попытка адекватно воспроизвести и донести его до всего человечества с помощью несовершенной человеческой речи оказалась не под силу даже великому Гегелю.

3. «Дисциплина сознания» Гегеля.

Гегель мечтал сделать мышление содержанием самого мышления, чтобы человек научился мыслить мышление, освободившись от «чувственной конкретности», где сознание работало бы только с чистыми понятиями, без всяких «чувственных» ассоциаций с миром вещей — «Изучение этой науки [логики], длительное пребывание и работа в этом царстве теней есть абсолютная культура и дисциплина сознания.» (Гегель, «Наука Логики», Введение) А также — «Если эта способность мышления еще не избавила себя от чувственно конкретных представлений и от резонерства, то она должна сначала упражняться в абстрактном мышлении, удерживать понятия в их определенности и научиться познавать, исходя из них.» (Гегель, «Наука Логики», Введение) Но такое на практике вряд ли возможно, тем более для какого-то конкретного человека со своими собственными заморочками и прихотями, немедленными нуждами и случайными летучими наваждениями. О «дисциплине сознания» Гегель мог бы говорить с успехом только с компьютерным железом, которого в его времена, увы, ещё не было. Человеческая жизнь слишком коротка, чтобы человеку успеть смирить свою «чувственную конкретность» и приблизиться хотя бы на десятую долю процента к этой желаемой гегелевской «дисциплине сознания». Конечно, приблизиться можно и на процент под дулами шмайсеров и под бешеный лай немецких овчарок, смирив свою «чувственность» лагерной баландой. Германская нация достигла в таком воспитании духа в своё время больших высот, старательно следуя бессмертным заветам великого Гегеля. Но к великому также сожалению для Гегеля немцы были вынуждены вернуться обратно к «резонёрству» о социальной справедливости и ценности человеческой жизни после некоторого относительно короткого эксперимента над человечеством по избавлению его от «чувственной конкретности», потому что процента для человечества оказалось чересчур много, явный перебор.

4. Самоконтроль как фактор воспроизводства отсутствия чистоты.

Единства бытия с чем-либо, тем более с самой мыслью о нём, а также наоборот — единства мысли с бытием как со своим окружением, невозможно достичь насильственным способом, никаким волевым приведением ума к некой суровой казарменноподобной дисциплине, хоть над собой, хоть над другими людьми, тут совершенно нечего обольщаться. Гегель показал такой путь к «дисциплине сознания», в результате которого эту дисциплину может обрести разве что мёртвый. Как ни пытайся приблизиться, всё равно получатся одни слёзы, какие-то спонтанные воспоминания, обиды, мечты или просто блики, шорохи, першение в горле или бурление в животе. То есть, сколько себя ни контролируй, не проверяй на предмет чистоты от «чувственной конкретности», получится только это само отсутствие чистоты и даже ещё большая контаминация сознания проклятой Гегелем и предшествующей ему философской традицией «чувственностью», бесконечное инфицирование мышления жёсткой брутальной волей и подчинённым ей рабским машинным старанием. Самоконтроль, насильственно насаждаемый и укрепляемый, способен только ещё больше усилить в сознании философа его раздвоение и противодействие самому себе в достижении противоестественного для сознания состояния единства мысли с самой собой, а значит и с бытием. Получается — движение от мышления в противостоящих друг другу противоположностях ведёт сознание к ещё более острой внутренней борьбе и даже к непримиримому противостоянию его оппонирующих определений.

5. Выбор между альтернативами как расколотость мышления.

Вроде бы обычная жизненная ситуация — одно мнение противостоит другому. Чьё из них ближе к истине, тому и карты сдавать. Однако в решении проблемы определения бытия нет основания для предпочтений, но есть две равноправные альтернативы, и каждая из них приводит к неразрешимым трудностям. Ни простое поименование бытия как подбор для понятия бытия синонимов, которые могли бы уточнить знание о бытии, ни молчаливый отказ Гегеля вообще от проведения такой процедуры ради очищения знания о бытии от посторонних смысловых примесей не решает задачу. В одном случае — философия выделяет понятие относительно только части, а не всего бытия, в другом — отождествляет понятие опять же с какой-то частью бытия, с его некоторым неопределённым множеством, будучи не в силах экстраполировать понятие на всю неопределённость бытия. Философия или конкретизирует понятие как референцию к некоему локальному бытию, уже лишённому единства, различённому с понятием об этом бытии, или абстрагирует его до некоторой условной неопределённости бытия, единой внутри себя, но которая уже является обиходной для сознания в его эстетических предпочтениях среди других человеческих собирательных понятий.

Здесь философия имеет дело с уже знакомой всем расколотостью человеческого мышления, с обличением которой всегда яростно выступал Гегель. Но в состоянии ли философия отыскать единство для этих противоположностей, которое не содержало бы в себе трудностей спонтанного, ненамеренного противопоставления одного другому? К сожаленью, на исторического Гегеля нет и не может быть другого Гегеля, способного его же пересмотреть критически. Если судить по тому факту, что Гегель предпочёл единство, сплав, слитность бытия и мышления их раздельному существованию, то можно с уверенностью сказать — продекларированное Гегелем революционное преобразование логики есть лишь видимость, имитация преодоления раздвоенности мышления, человеческой привычки мыслить оппонирующими определениями. Гегель никуда не ушёл от логики, предписывающий выбор двух непримиримых частей противоречия и не оставляющий сознанию никакой другой альтернативы. Также и отношение к бытию для любого философа, в том числе и для Гегеля, жёстко обусловлено предписаниями связной человеческой речи. Поэтому ничего нового и уж тем более гениального в предпочтении Гегелем единства бытия его многообразию нет. Такой выбор диктует его собственный псевдодиалектический шаблон, предусматривающий приоритет единства над многообразием, но, в то же время, выводящий это единство из простых частей, которые ему предшествуют, и им же, этим частям такое единство противопоставляющий. Никакой середины здесь не предусмотрено.

7. Одностороннее мышление бытия.

Но так поступает философ, который за единство бытия принимает только одну из его сторон, которая противостоит многообразию и даже намеренно противопоставляется ему как некая научная, цивилизованная альтернатива. Если Гегель выступает против расколотости мышления в пользу его единства и, прежде всего, единства с бытием, он должен, по идее, включить в эту схему и самого себя, своё собственное рассуждение по этому поводу. Но он неявно позволяет себе то, в чём отказывает другим, а именно — воспроизводит эту расколотость в своём собственном отношении к бытию, к его единству. Гегель своим примером наглядно показывает — человек мыслит бытие исключительно односторонне — либо мыслит дробно, вне единства знания с бытием, а значит, и вне самого единого бытия, либо просто нарочито искусственно декларирует единство со знанием о нём и самоуверенно строит логическую конструкцию, в которой отсутствует вообще какой-либо минимальный человеческий смысл, за исключением невольного приписывания этой конструкции каких-то уже известных собирательных значений, схожих с негативными, пренебрежительными значениями таких понятий, как хлам, фуфло, лажа. Недаром Гегель обожает употребление субстантивированных прилагательных среднего рода — типа, логическое, диалектическое, абсолютное, непосредственное, отрицательное и т.д.. Вполне достаточно смыслового тумана, чтобы придать рассуждению желаемое глубокомыслие. Но также достаточно для подмены необходимой логической ясности этим самым бутафорским крашеным глубокомыслием.

8. Мнимая революционная новизна.

Таким образом, вся мнимая революционная новизна Гегеля сводится к такому пониманию единства бытия, которое на самом деле противостоит его многообразию и, по сути, ничего не решает, а только ещё больше запутывает проблему. Внимательному философскому уму не составит большого труда проследить глобальные разрушительные последствия этого, якобы, «открытия» и отыскать логические тропки, ведущие к историческим персонам, использовавшим эту гегелевскую идею или какую-то другую, аналогичную ей, для достижения своих узкокорпоративных целей. Тот, кто громче всех кричит о необходимости единства цивилизованного мира, скрывает под этими воплями, прежде всего, какое-то своё местное, локальное единство, круговую поруку лиц, заинтересованных в объединении, в концентрации сил перед лицом своих прямых политических и экономических конкурентов, не желающих поступаться своими интересами ради чужого безмерного обогащения. Искусство разделять мир на своих и чужих, непреодолимое стремление к разрушению его единства, приписывание чужим самих этих намерений, чтобы использовать в своих интересах плоды ненависти народов друг к другу — вот образец бездумного подражания и следования Гегелевской революционной логике.

Отмеченная Гегелем двойственность мышления относима не только к бытию дробному, различённому в обыденном сознании, но и к самому единству бытия, к единству, которое можно помыслить также альтернативно — в различении с многообразием бытия. На этом Гегель и подскользнулся. Такая трудность происходит, прежде всего, из несовместимости бытия и знания о нём. Когда появляется хоть какое-то минимальное знание, утрачивается единство бытия, но единство знания о бытии с самим бытием тоже недостижимо, так как чревато утратой знания о единстве бытия — именно о таком единстве, которое не противостоит многообразию, но включает его в себя как свою неотъемлемую часть.

9. Путь Гегеля в никуда.

Можно сколько угодно говорить о том, что чтение Гегеля затруднено из-за того, что его идеи опережают время и обыденному сознанию предстоит ещё дорасти до понимания открытия, которое сделал в философии великий немецкий гений. Но факт очередного революционного разделения Гегелем философии на конкурирующие фракции, а мышления на оппонирующие определения никуда не скроешь. Гегель выражается яснее некуда о раздвоении и противостоянии, о единстве и слитности, о ранжировании мышления и самой философии на разной степени достоверности и достойности способы и инструменты исследования бытия. Но Гегель каждый раз последовательно выбирает путь, который никак нельзя назвать ведущим философа к осознанию единства бытия, а также знания о нём, знания, единого с бытием и обладающего единством, подобным единству бытия, собранным по законам такого единства.

Однако заклеймить Гегеля позором за его неуклюжую и, в сущности, неудачную попытку отыскать единство бытия было бы слишком просто, этот урок оплачен не только труднейшими умственными поисками самого Гегеля нужной мысли и нужного слова для её выражения, но и поступками тех, кто, во имя Гегеля и следуя его логике, уничтожил миллионы несогласных. Гегель, может, и не был в состоянии предвидеть, к чему могут привести выверты сознания индивида, даже не самого Гегеля, а типичного, среднестатистического человека, мыслящего дробно, пусть даже если он мыслит единством. Гегель выдвинул концепт, сдобрил его незаурядным профессорским красноречием и завещал в нём не сомневаться, а потом сгинул, оставив кашу, которую он заварил, расхлёбывать грядущим поколениям. Но даже по прошествии столетий после написания «Науки логики» проблема определения бытия никуда не делась, только стала ещё насущней. Но это не значит, что она не может быть решена совсем, просто её решение находится в совершенно другой плоскости, нежели в линейном логическом следовании от фактического многообразия до желаемого единства.

Подборка по базе: 6.1 Онтология Философия.docx, Лавринович И.В. История и онтология науки_ИПЗ.docx, ПЗ по дисциплине «История и онтология науки» HUCE.docx, Задание 2 (история и онтология науки).docx, ИПЗ(история и онтология науки).docx, лекция 1 ИСТОРИЯ И ОНТОЛОГИЯ НАУКИ 1.ppt, Шалагина А.И._История и онтология науки_ПЗ1.docx, ПЗ по дисциплине «История и онтология науки».docx, ИПЗ по дисциплине «История и онтология науки».docx, Шалагина А.И._История и онтология науки_ПЗ2.docx

ГЛАВА 1. ОНТОЛОГИЯ И МЕТАФИЗИКА

№1. Дайте определения понятиям.

| Понятие | Автор понятия | Определение |

| ОНТОЛОГИЯ | Р. Гоклениус | «учение о бытии», один из базовых разделов в структуре философского знания. |

| МЕТАФИЗИКА | Андроний

Родосский |

понятие философской традиции, последовательно фиксирующее в исторических трансформациях своего содержания |

№2. Сформулируйте основные вопросы онтологии и метафизики.

| Онтология | Метафизика |

| 1. Что существует?

2. Почему существует? 3. Что такое бытие и небытие? |

1. Что есть причина причин?

2. Каковы истоки истоков? 3.Каковы начала начал? |

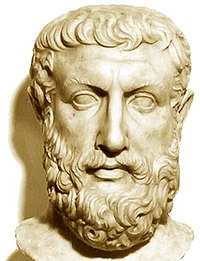

№3.Назовите имя первого великого метафизика, “отца метафизики”

Парменид

№4. Охарактеризуйте соотношение онтологии и метафизики?

Онтология — основополагающая метафизики, но не отождествляющаяся с ней онтология является своего рода метафизика бытия

№5.Заполните таблицу “Онтология и типы существования объектов”

| Атрибуты Бытия | Пространство | + | — | — | + |

| Время | + | + | — | — | |

| Название мира

объектов |

|||||

| П

Р И М Е Р Ы Б Ъ Е К Т О В |

1.

2. 3. |

1.

2. 3. |

1.

2. 3. |

1.

2. 3. |

№6.Назовите основные ошибки, возникающие при попытке дать определение понятию “Бытие”.

| Тип ошибки | Пример. |

| Узкое | Объективный мир, существующий независимо от сознания |

| Широкое | Все существующее и материальное, и мнительное |

| “Круг

в определении” |

«Бытие есть бытие» |

№7.Дайте определение базовым онтологическим понятиям.

| Субстанция – | Сущность, то что лежит в основе |

| Субстрат – | Это то, из чего что-либо состоит |

№8.Заполните таблицу “Пространство и время как атрибуты бытия”

| Субстанциональная концепция ПиВ | Релятивистская концепция ПиВ | |

| Автор | Ньютон | Эйнштейн |

| Идея | Время и пространство существуют независимо | Время не может быть отделено от трёх измерений пространства, потому что наблюдаемая скорость, с которой течёт время для объекта, зависит от его скорости относительно наблюдателя, а также от силы гравитационного поля, которое может замедлить течение времени. |

№9.Заполните таблицу “Вариативность пространства и времени”.

| Физическое | Социальное | Духовное | |

| Пространство | То, что можно измерить линейкой | Государственная граница | Внутреннее пространство |

| Время | Час | Событие |

№10. Заполните таблицу “Онтологическая позиция мировоззрения (количество субстанций)”.

| Монизм | Дуализм | Плюрализм | |

| Автор | Маркс | Декарт | Лейбниц |

| Идея | Материалистическая модель всего сущего | Неразрывно сосуществуют два начала не сводимые друг к другу или даже противоположные | Множественное взаимодействие между субстанциями |

№11.Назовите основные атрибуты (всеобщие формы её бытия) материи и дайте им определение.

| 1. Движение | Различные изменения |

| 2. Пространство | Совокупность отношений, выражающих координацию сосуществующих объектов, их взаимное расположение и относительную величину |

| 3. Время | Порядок смены явлений и состояний, их последовательность и длительность |

№12.Фридрих Энгельс выделил пять форм движения материи.

Восстановите список.

- Механическая

- Физическая

- Химическая

- Биологическая

- Социальная

№13.Охарактеризуйте универсальные свойства материи.

| Несотворимость и неуничтожимость | |

| Вечность | |

| Движение | |

| Детерминированность | |

| Причинность | |

| Отражение |

№14.Охарактеризуйте понятие

| НЕБЫТИЕ |

№15.Приведите примеры использования категории “небытие” в религии, философии и науке

| Религия | Философия | Наука |

| 1.

2. 3. |

1.

2. 3. |

1.

2. 3. |

№16.Охарактеризуйте сущность двух принципов “мироустройства”:

| Антропный принцип | |

| Принцип заурядности |

№17. Внимательно прочитайте текст и объясните позицию Б.Рассела (теория дескрипций) в отношении проблемы существования

“Под «дескрипцией» я подразумеваю такую фразу, как, например, «теперешний президент Соединенных Штатов», где обозначается какая-то личность или вещь, но не именем, а некоторым свойством, принадлежащим, как предполагают или как известно, исключительно этой личности или вещи. Такие фразы причиняли раньше много неприятностей. Предположим, я говорю: «Золотая гора не существует», – и предположим, вы спрашиваете: «Что именно не существует?» Казалось бы, что если я отвечу: «Золотая гора», – то тем самым я припишу ей какой-то вид существования. Очевидно, что если я скажу: «Круглого квадрата не существует», – это будет не тем же, а другим высказыванием. Здесь, по-видимому, подразумевается, что Золотая гора –)то одно, а круглый квадрат – другое, хотя и то и другое не существует.

Назначение теории описаний – преодолеть эти, а также и другие трудности. Согласно этой теории, если утверждение, содержащее фразу в форме «то-то и то-то», анализируется правильно, то фраза «то-то и то-то» исчезает. Например, возьмем утверждение «Скотт был автором „Веверлея”». Теория интерпретирует это утверждение следующим образом: «Один и только один человек написал „Веверлея”, и этим человеком был Скотт». Или более полно: «Имеется один объект с , такой, что утверждение «х написал „Веверлея”» истинно, если х есть с , и ложно в других случаях. Более того, х есть Скотт». Первая часть этого высказывания до слов «более того» определяется как обозначающая:

«Автор „Веверлея” существует (или существовал, или будет существовать)». Таким образом, «Золотая гора не существует» означает: «Не имеется объекта с такого, что высказывание „х – золотое и имеет форму горы” истинно только тогда, когда х есть с , но не иначе». При таком определении не нужно ломать голову над тем, что мы подразумеваем, говоря: «Золотая гора не существует».

Существование, согласно этой теории, может утверждаться только относительно дескрипций. Мы можем сказать: «Автор „Веверлея” существует»; но сказать: «Скотт существует», – плохо грамматически или весьма плохо синтаксически. Все это объясняет два тысячелетия глупых разговоров о «существовании», начатых еще в «Теэтете» Платона. Один из результатов этой деятельности в области философии, которую мы рассматриваем, – это свержение математики с величественного трона, который она занимала со времени Пифагора и Платона, и разрушение предубеждения против эмпиризма, которое из этого вытекало. И действительно, математическое знание не выводится из опыта путем индукции; основание, по которому мы верим, что 2 + 2 = 4, не в том, что мы так часто посредством наблюдения находим на опыте, что одна пара вместе с другой парой дает четверку. В этом смысле математическое знание все еще не эмпирическое. Но это и не априорное знание о мире. Это на самом деле просто словесное знание. «3» означает «2 + 1», а «4» означает «3 + 1». Отсюда следует (хотя доказательство и длинное), что «4» означает то же, что «2 + 2». Таким образом, математическое знание перестало быть таинственным. Оно имеет такую же природу, как и «великая истина», что в ярде 3 фута”.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

№18. Приведите примеры гипостазирования

1._____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________2.____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________3.____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Библиографический список

Основная литература

- Горелов А. А.. Основы философии : учебник для студ. сред. проф. учеб. заведений / А. А.Горелов. — 9-е изд., стер. — М. : Издательский центр «Академия», 2010. — 256 с.

- Миронов В.В., Иванов А.В. Онтология и теория познания: Учебник. — М.: Гардарики, 2005. — 447 с.

Рекомендуемая литература

- Наука: от методологии к онтологии [Текст] / Рос. акад. наук, Ин-т философии ; Отв. ред.: А.П. Огурцов, В.М. Розин. – М.: ИФ РАН, 2009. – 287 с.

- Никитаев В.В. К онтологии множественности миров. Философия науки. Вып. 6. — М.: ИФРАН, 2000. –С.135-159.

- Розов Н.С. Философия небытия: новый подъем метафизики или старый тупик мышления? Credo New, 2011, №1(65) C.158-186.

- Смирнов А.В. Возможна ли незападная философия // Философский журнал. 2011. №1(6).

- Тарароев Я.В. Представление бытия как связей в контексте современной космологии // Философия науки №14, 2009. — C.158-170.

- Хайдеггер, М. Бытие и время / Пер. с нем. В. В. Бибихина — М.: Ad Marginem, 1997. Переизд.: СПб.: Наука, 2002; М.: Академический проект, 2010.

- Чанышев А.Н. Трактат о небытии // Философия и общество, 2005, №1. С.5-15.

ГЛАВА 1. ОНТОЛОГИЯ И МЕТАФИЗИКА

№1. Дайте определения понятиям.

|

Понятие |

Автор понятия |

Определение |

|

ОНТОЛОГИЯ |

||

|

МЕТАФИЗИКА |

№2. Сформулируйте основные вопросы онтологии и метафизики.

|

Онтология |

Метафизика |

|

1. 2. 3. |

1. 2. 3. |

№3.Назовите имя первого великого метафизика, “отца метафизики” ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

№4. Охарактеризуйте соотношение онтологии и метафизики?

______________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

№5.Заполните таблицу “Онтология и типы существования объектов”

|

Атрибуты Бытия |

Пространство |

+ |

— |

— |

+ |

|

Время |

+ |

+ |

— |

— |

|

|

Названиемира объектов |

|||||

|

П Р И М Е Р Ы О Б Ъ Е К Т О В |

1. 2. 3. |

1. 2. 3. |

1. 2. 3. |

1. 2. 3. |

№6.Назовите основные ошибки, возникающие при попытке дать определение понятию “Бытие”.

|

Тип ошибки |

Пример. |

|

Узкое |

|

|

Широкое |

|

|

“Круг в определении” |

№7.Дайте определение базовым онтологическим понятиям.

№8.Заполните таблицу “Пространство и время как атрибуты бытия”

|

Субстанциональная концепция ПиВ |

Релятивистская концепция ПиВ |

|

|

Автор |

||

|

Идея |

№9.Заполните таблицу “Вариативность пространства и времени”.

|

Физическое |

Социальное |

Духовное |

|

|

Пространство |

|||

|

Время |

№10. Заполните таблицу “Онтологическая позиция мировоззрения (количество субстанций)”.

|

Монизм |

Дуализм |

Плюрализм |

|

|

Автор |

|||

|

Идея |

№11.Назовите основные атрибуты (всеобщие формы её бытия) материи и дайте им определение.

№12.Фридрих Энгельс выделил пять форм движения материи.

Восстановите список.

1.__________________________________________________

2.__________________________________________________

3. __________________________________________________

4. __________________________________________________

5. __________________________________________________

№13.Охарактеризуйте универсальные свойства материи.

|

Несотворимость и неуничтожимость |

|

|

Вечность |

|

|

Движение |

|

|

Детерминированность |

|

|

Причинность |

|

|

Отражение |

№14.Охарактеризуйте понятие

№15.Приведите примеры использования категории “небытие” в религии, философии и науке

|

Религия |

Философия |

Наука |

|

1. 2. 3. |

1. 2. 3. |

1. 2. 3. |

№16.Охарактеризуйте сущность двух принципов “мироустройства”:

|

Антропный принцип |

|

|

Принцип заурядности |

№17. Внимательно прочитайте текст и объясните позицию Б.Рассела (теория дескрипций) в отношении проблемы существования

“Под «дескрипцией» я подразумеваю такую фразу, как, например, «теперешний президент Соединенных Штатов», где обозначается какая-то личность или вещь, но не именем, а некоторым свойством, принадлежащим, как предполагают или как известно, исключительно этой личности или вещи. Такие фразы причиняли раньше много неприятностей. Предположим, я говорю: «Золотая гора не существует», – и предположим, вы спрашиваете: «Что именно не существует?» Казалось бы, что если я отвечу: «Золотая гора», – то тем самым я припишу ей какой-то вид существования. Очевидно, что если я скажу: «Круглого квадрата не существует», – это будет не тем же, а другим высказыванием. Здесь, по-видимому, подразумевается, что Золотая гора –)то одно, а круглый квадрат – другое, хотя и то и другое не существует.

Назначение теории описаний – преодолеть эти, а также и другие трудности. Согласно этой теории, если утверждение, содержащее фразу в форме «то-то и то-то», анализируется правильно, то фраза «то-то и то-то» исчезает. Например, возьмем утверждение «Скотт был автором „Веверлея”». Теория интерпретирует это утверждение следующим образом: «Один и только один человек написал „Веверлея”, и этим человеком был Скотт». Или более полно: «Имеется один объект с , такой, что утверждение «х написал „Веверлея”» истинно, если х есть с , и ложно в других случаях. Более того, х есть Скотт». Первая часть этого высказывания до слов «более того» определяется как обозначающая:

«Автор „Веверлея” существует (или существовал, или будет существовать)». Таким образом, «Золотая гора не существует» означает: «Не имеется объекта с такого, что высказывание „х – золотое и имеет форму горы” истинно только тогда, когда х есть с , но не иначе». При таком определении не нужно ломать голову над тем, что мы подразумеваем, говоря: «Золотая гора не существует».

Существование, согласно этой теории, может утверждаться только относительно дескрипций. Мы можем сказать: «Автор „Веверлея” существует»; но сказать: «Скотт существует», – плохо грамматически или весьма плохо синтаксически. Все это объясняет два тысячелетия глупых разговоров о «существовании», начатых еще в «Теэтете» Платона. Один из результатов этой деятельности в области философии, которую мы рассматриваем, – это свержение математики с величественного трона, который она занимала со времени Пифагора и Платона, и разрушение предубеждения против эмпиризма, которое из этого вытекало. И действительно, математическое знание не выводится из опыта путем индукции; основание, по которому мы верим, что 2 + 2 = 4, не в том, что мы так часто посредством наблюдения находим на опыте, что одна пара вместе с другой парой дает четверку. В этом смысле математическое знание все еще не эмпирическое. Но это и не априорное знание о мире. Это на самом деле просто словесное знание. «3» означает «2 + 1», а «4» означает «3 + 1». Отсюда следует (хотя доказательство и длинное), что «4» означает то же, что «2 + 2». Таким образом, математическое знание перестало быть таинственным. Оно имеет такую же природу, как и «великая истина», что в ярде 3 фута”.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

№18. Приведите примеры гипостазирования

1._____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________2.____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________3.____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Библиографический список

Основная литература

- Горелов А. А.. Основы философии : учебник для студ. сред. проф. учеб. заведений / А. А.Горелов. — 9-е изд., стер. — М. : Издательский центр «Академия», 2010. — 256 с.

- Миронов В.В., Иванов А.В. Онтология и теория познания: Учебник. — М.: Гардарики, 2005. — 447 с.

Рекомендуемая литература

- Наука: от методологии к онтологии [Текст] / Рос. акад. наук, Ин-т философии ; Отв. ред.: А.П. Огурцов, В.М. Розин. – М.: ИФ РАН, 2009. – 287 с.

- Никитаев В.В. К онтологии множественности миров. Философия науки. Вып. 6. — М.: ИФРАН, 2000. –С.135-159.

- Розов Н.С. Философия небытия: новый подъем метафизики или старый тупик мышления? Credo New, 2011, №1(65) C.158-186.

- Смирнов А.В. Возможна ли незападная философия // Философский журнал. 2011. №1(6).

- Тарароев Я.В. Представление бытия как связей в контексте современной космологии // Философия науки №14, 2009. — C.158-170.

- Хайдеггер, М. Бытие и время / Пер. с нем. В. В. Бибихина — М.: Ad Marginem, 1997. Переизд.: СПб.: Наука, 2002; М.: Академический проект, 2010.

- Чанышев А.Н. Трактат о небытии // Философия и общество, 2005, №1. С.5-15.

-

Основные проблемы философской онтологии. Категория «бытие» в истории философии.

Онтология

–

учение о бытие и о сущем.

Основные

направления онтологии:

-

Материализм

отвечает на основной вопрос философии

так: материя, бытие, природа первичны,

а мышление, сознание и идеи вторичны

и появляются на определенном этапе

познания природы. Материализм

подразделяется на следующие направления:-

Метафизический.

В его рамках вещи рассматриваются вне

истории их возникновения, вне их

развития и взаимодействия, несмотря

на то, что считается, что они материальны.

Основные представители (самые яркие

— это французские материалисты XVIII

века): Дидро, Гольбах, Гельвеций, так

же к этому направлению можно отнести

и Демокрита. -

Диалектический:

вещи рассматриваются в их историческом

развитии и в их взаимодействии.

Основатели: Маркс, Энгельс.

-

-

Идеализм:

мышление, сознание и идеи первичны, а

материя, бытие и природа вторичны.

Подразделяется также на два направления:-

Объективный:

сознание, мышление и дух первичны, а

материя, бытие и природа вторичны.

Мышление отрывается от человека и

объективизируется. Тоже происходит

с сознанием и идеями человека. Основные

представители: Платон и Гегель (XIX век)

(вершина объективного идеализма). -

Субъективный.

Мир – это комплекс наших отношений.

Не вещи вызывают ощущения, а комплекс

ощущений есть то, что мы называем

вещами. Основные представители: Беркли,

так же можно отнести и Дэвида Юма.

-

Проблематика.

Помимо разрешения основного вопроса

философии онтология занимается изучением

ряда других проблем Бытия:

-

Формы

существования Бытия, его разновидности.

(чо за бред? может это все не надо?) -

Статус

необходимого, случайного и вероятного

– онтологический и гносеологический. -

Вопрос

о дискретности/непрерывности Бытия. -

Имеет

ли Бытие организующее начало либо

цель, или развивается по случайным

законам, хаотически. -

Действует

ли в Сущем четкие установки детерминизма

или оно случайно по своему характеру. -

Ряд

других вопросов

Бытие

— одна из главных философских категорий.

Попытки раскрыть содержание этой

категории сталкиваются с большими

трудностями: на первый взгляд, оно

слишком широко и неопределенно. На этом

основании некоторые мыслители полагали,

что категория бытия — это «пустая»

абстракция. Гегель писал: «Для мысли

не может быть ничего более малозначащего

по своему содержанию, чем бытие».

Ф.Энгельс, полемизируя с немецким

философом Е.Дюрингом, также считал, что

категория бытия мало чем может нам

помочь в объяснении единства мира,

направления его развития. Однако в XX

веке намечается «онтологический

поворот», философы призывают вернуть

категории бытия ее подлинное значение.

Как согласуется реабилитация идеи

бытия с пристальным вниманием к

внутреннему миру человека, его

индивидуальным характеристикам,

структурам его мыслительной деятельности?

Содержание

бытия как философской категории отлично

от обыденного его понимания. Бытие

повседневного обихода — это все, что

существует: отдельные вещи, люди, идеи,

слова. Философу же важно выяснить, что

такое «быть», существовать?

Отличается ли существование слов от

существования идей, а существование

идей — от существования вещей? Чей вид

существования более прочен? Как объяснить

существование отдельных вещей — «из

них самих», или же искать основу их

существования в чем-то еще — в первоначале,

абсолютной идее? Существует ли такое

Абсолютное Бытие, ни от кого, ни от чего

не зависящее, определяющее существование

всех других вещей, и может ли человек

познать его? И, наконец, самое главное:

каковы особенности человеческого

существования, каковы его связи с

Абсолютным Бытием, каковы возможности

упрочения и совершенствования своего

бытия? Основное желание «быть»,

как мы видели, является главной «жизненной

предпосылкой» существования философии.

Философия — это поиск форм причастности

человека к Абсолютному Бытию, закрепления

себя в бытии. В конечном итоге — вопрос

о бытии — это вопрос о преодолении

небытия, о жизни и смерти.

Греческий

философ Парменид

(VI-V век до н.э.) сделана попытку осмыслить

проблему бытия в ее «первозданности»

и чистоте. Именно к идеям Парменида

обращается философская мысль о бытии

в XX столетии. Парменид считает, что при

определении бытия не может быть места

недоговоренности, текучести,

многосмысленности: нельзя сказать,

что-то существует и одновременно не

существует. Нельзя быть «немножко

живым» или «немножко мертвым».

Подвижная и безответственная человеческая

мысль должна замереть при прикосновении

к проблеме бытия. Бытие, существование

не возникает и не имеет конца, ибо иначе

надо сказать, что в какой-то миг сущее

не существует. Следовательно, бытие

вечно — безначально и неуничтожимо.

Бытие едино и неделимо, ибо в противном

случае надо признать дополнительную

причину дробления бытия на части как

предшествующую сущему. Бытие неподвижно,

поскольку движение предполагает начало

и конец, изменение, небытие. Такое

неподвижное, вечное, «сплошное»

бытие находится вне пространства и

времени, ибо иначе придется признать,

что пространство и время имеют бытие

до всякого бытия. Такое единое и

неподвижное бытие не может воздействовать

на наши чувства, ибо они постигают

только отделимое, множественное.

Пармениду претит представление о

бесконечности бытия как постоянном

развертывании все новых и новых форм,

свойств. Бытие как абсолютная устойчивость

должно быть завершенным, определенным,

замкнутым в себе, ни в чем не нуждающимся.

Поэтому он вводит сравнение бытия с

шаром как символом абсолютной замкнутости,

завершенности, совершенства. Для

Парменида «быть» означает «быть

всегда», это выражение абсолютной

устойчивости, прочности, отделенной

от видимого мира и вынесенной за его

пределы, это неопределенная, «чистая»

определенность, отделенная от определенных

вещей. Соответственно, познать такое

бытие можно только непосредственно, с

помощью интеллектуальной интуиции, но

не посредством изучения мира конкретных

вещей.

-

Проблема

субстанции. Представления о «материальном»

и «идеальном» в истории философии.

(начало

для общего развития. Кому интересно –

увеличите)

Понятие

субстанции

углубляет понятие материи

с точки зрения поиска общей материальной

основы всех явлений, их единства и

многообразия. Уже в античной философии

вычленялись различные субстанции,

которые трактовались как материальный

субстрат и первооснова изменения вещей,

как сущность, лежащая в основе всего.

Особенно

активно категория субстанции

разрабатывалась в

новоевропейской

философии (XVII—XVIII вв.).

Р.

Декарт

определяет субстанцию как вещь, которая

существует так, что не нуждается для

своего существования ни в чем, кроме

самой себя. Он выделяет две параллельно

существующие независимые друг от друга

субстанции — протяженную (телесную) и

мыслящую.

Б.

Спиноза,

сохраняя определение субстанции

Декарта, считал, однако, мышление и

протяжение двумя атрибутами единой

телесной субстанции как причины самой

себя. Субстанция со своими атрибутами,

т. е. природа (Бог), — это, согласно

Спинозе, порождающая природа, а наш

чувственно воспринимаемый мир как

совокупность вещей-модусов — это

порожденная природа.

В

отличие от Декарта (дуализм) и Спинозы

(монизм) Г.

Лейбниц

ввел множественность и многообразие

в саму субстанцию (плюрализм). Он

расчленил ее на бесконечное количество

отдельных субстанциональных начал,

которые он назвал «монадами». Последние,

согласно Лейбницу, не есть нечто

материальное, а представляют собой

«индивидуальные духи», «спиритуальиые

сущности», духовные формообразования.

Проблема

субстанции активно обсуждалась в

немецкой классической философии.

По мнению Канта, субстанция явлений

есть постоянное и непреходящее в вещах.

Категория субстанции организует

материал опыта в некоторую целостность,

создает необходимое единство свойств

объекта. Без этой категории невозможна

наука как система знаний об одном и том

же предмете.

Гегель

считал, что субстанция — основа всякого

подлинного развития, а категория

субстанции — начало всякого научного

мышления, систематически развивающего

определения своего предмета. Ближайшим

образом субстанция («субстанциональное

отношение») раскрывается как причинное

отношение и в конечном итоге как

диалектическое противоречие.

Согласно

диалектическому материализму, который

универсальное единство мира усматривает

в его материальности, в понятии субстанции

материя отражена уже не в аспекте ее

абстрактной противоположности сознанию

(мышлению), а со стороны внутреннего

единства всех форм ее движения, всех

имманентных различий и противоположностей.

Категория

субстанции является ключевой при

решении проблемы единства и многообразия

мира. Мир един не потому, что мы его

мыслим единым, и не потому, что он

существует. Единство мира состоит в

его материальности. Оно находит свое

выражение, во-первых, во всеобщей связи

и развитии всех явлений; во-вторых, в

наличии у всех видов материи таких

универсальных атрибутов, как движение,

пространство, время; в-третьих, в

существовании всеобщих закономерностей

бытия, действующих на всех уровнях

структурной организации материи.

Единство

мира нельзя понимать как однообразие

его строения, а как единство в его

многообразии, т. е. как материалистическое

и одновременно диалектическое

формообразование. Материальное единство

и многообразие мира подтверждается

всей историей и современным уровнем

развития науки.

Материя

(материальное)

— противоположность духовного,

идеального. Последнее — предельно

общая характеристика человеческого

сознания в его «чистом виде» (независимо

от его форм, уровней и т.д.), основанная

на его противопоставлении материи в

«чистом виде» (независимо от ее видов,

форм движения, атрибутов и т.п.), т. е.

всему нематериальному.

Классическое

определение идеального

принадлежит К. Марксу, который писал,

что идеальное есть не что иное, как

материальное, пересаженное в человеческую

голову и преобразованное в ней. Речь

идет о том, что, во-первых, материальное

пересаживается в голову человека как

родового социального (а не только

биологического) существа, не как

«гносеологического Робинзона».

Во-вторых, это «пересаживание»

осуществляется в процессе отражения

материального в ходе общественно-исторической

практики. В-третьих, идеальное — это

не мертвая, неподвижная копия, не

пассивное зеркальное отражение

материального, а активное его

преобразование, ибо оно не рабски

следует за материальным объектом, а

творчески, конструктивно-критически

отражает и преобразует его.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

По своему обыкновению все проблемы, в том числе и философские, анализируются в проекции на определённый период времени. История философии тому подтверждение. Ведь концепций бытия множество: от самых нереалистичных и абстрактных до конкретно содержательных представлений.

Смысл проблемы бытия

Впервые о бытие, как о философской проблеме заговорил Парменид ещё во времена Древней Греции. Древнегреческий мыслитель в европейской философии обозначил бытие как всеобщее свойство мира просто быть. В силу этого он понимал бытие как нечто неизменное и неподвижное.

Парменид писал: «Не возникает оно (бытие) и не подчиняется смерти.

Цельное все, без конца, не движется и однородно.

Не было в прошлом оно, не будет, но все – в настоящем.

Без перерыва, одно. Ему ли разыщешь начало?

Как и откуда расти?»

В свою очередь, Гераклит утверждал, что бытие не может быть неподвижным, и выдвигал идею постоянно меняющегося мира. Тем не менее, в момент, когда понятие бытия обосновалось в науке, можно называть переходом от протофилософии к философии. Это, в конечном счёте, дало возможность представить мир как неделимое целое на теоретическом уровне.

Тем временем, Платон занимается развитием идей Парменида, и предлагает рассмотреть понятие бытия как истину, это значит, определить то, что на самом деле есть бытие, а не то, какой оно носит характер. Проблема онтологии, по мнению Платона, представляет собой осмысление чистого бытия как эйдоса или идеи. Быть – значит быть эйдосом.

Из диалога «Тимей»: «»…должно разграничить вот какие две вещи: что есть вечное, не имеющее возникновения бытие и что есть вечно возникающее, но никогда не сущее».

Мир вечных объективных идей для Платона был подлинным бытием. Хотя немного времени спустя, неоплатоник Плотин, будет утверждать, что подлинное бытие только Бог.

Аристотель внёс свой вклад в рассмотрение понятия бытия. В своём учении он попытался объединить все предшествующие результаты философов и сделать логические выводы. Таким образом, он получил понятия, которые раскрывали смысл бытия. Он поднял новые темы философии, значимые для позднейшей онтологии. Говорил о бытие как действительности, бытие как единстве противоположностей, бытие как божественном разуме.

Онтологические учения Платона и Аристотеля оставили свой след и внесли свой вклад в дальнейшее развитие западноевропейской онтологической традиции. В то же время христианские философы Средневековья смогли достаточно ловко приспособить античную онтологию для разрешения проблем теологии.

Проблемы доказательств бытия

Христианская философия уравнивала понятия Бога и абсолютного, подлинного бытия. Основной темой христианской философии становится проблема отношений Бога и мира, который он сам и создал. Идея творения объединяет понятия Бога и мира, а также абсолютного бытия Бога с относительным бытием мира. Понималось это так: мир не имеет своих корней, он не может быть вечным, потому что его создал Бог. За основную идею христианские мыслители принимали то, что Бог создал мир из ничего, так они понимали подлинный мир творения. Важное место среди проблем бытия занимали вопросы о бытие Бога.

Средневековая схоластика развивалась иначе. Здесь поднимались вопросы противоречия абсолютного и относительного бытия, подразумевая под собой бытие Бога и бытие мира. Противопоставлялись актуальное бытие и потенциальное, имеется в виду то, что сотворено Божьим промыслом и то, будущее, которое уже существует как божественная мысль.

Нововведение в средневековую онтологию привёл Фома Аквинский, который указал на существенные различия сущности и существования. Кроме этого выделил момент творческой действенности бытия, которая сосредоточена на самом бытие Бога в полной мере.

В философии Нового времени проблематика бытия рассматривалась с точки зрения учения о субстанции, она бралась за первооснову и первопричину всего сущего.

По нескольким направлениям развивались представления о субстанции:

- Первое направление представляло собой линию развития о существовании вещественной и духовной субстанции как элементов бытия у Декарта идущей к абсолютному отрицанию идей о материальной субстанции Беркли. В конечном итоге это привело к сомнениям в существовании и той, и другой субстанции в исследованиях Д. Юма.

- Другое направление было представлено Т. Гоббсом, Дж. Локком, Д. Дидро, П. Гольбахом, К. Гельвецием под эгидой материализма XVIII в., в котором говорилось о субстанциональном подходе к миру, где наиважнейшим моментом было отстаивание принципа первичной материальной реальности в равенстве с природой.

Кант о проблеме бытия

И. Кант первый выдвинул своё критическое мнение о том, что учение о бытие как о субстанции в корне неверно. И. Кант разбирал проблему бытия и утверждал, что бытие не есть проблема, сформированной им самим критической философии, потому как она скорее принадлежит к области метафизики, ввиду того, что решение этой проблемы лежит за пределами возможного опыта. Исследователь деятельности И. Канта В. И. Курашов говорил, что кантовская «Критика чистого разума» помещается всего лишь в одну фразу.

В. И. Курашов высказывался: «Вся онтология кантовской “Критики чистого разума” выражается одним высказыванием: есть вещи сами по себе, но они непознаваемы».

Гегель о проблеме бытия

Г. В. Ф. Гегель полностью отрицал учение И. Канта и идею «вещи в себе». В свою очередь, Гегель определяет главную особенность познания бытия и отождествляет её с мышлением, раскрытие сущности которого происходит посредством саморазвития.

Огюст Конт, основоположник позитивизма сделал окончательный вывод относительно критических заявлений насчёт гегелевской философии, которая заявляла философии как царицу наук. Он критически высказывался относительно онтологии философии, утверждая, что «наука – сама по себе философия».

Кант отождествлял философию с метафизикой, а метафизика, в свою очередь, это ненаучное и архаичное знание. И уже начиная с позитивизма XIX в. и до настоящего времени практически все направления философского познания, здесь и неокантианство, и неопозитивизм, и постмодернизм, рассматривают изначально, как заблуждения, все проявления возродить классическую онтологию и теологию прошлого, потому как полностью отказываются от осознания проблем бытия, как метафизических и догматических.

Маркс и Энгельс о проблеме бытия

К. Маркс и Ф. Энгельс, основатели диалектического материализма философии, в своих мыслях делают акцент на материалистические традиции в трактовке бытия. Эти догмы впервые определены философами-материалистами из Англии и Франции, которые общались к бытию и сущему как к движущейся материи, которая является бесконечной в пространстве и вечной во времени.

Диалектический материализм предполагал, что основную функцию, которая образует систему, несёт категория материи, но ни в коем случае не бытия. Основатели марксизма говорили о существовании исключительного вида бытия – общественное бытие людей. Здесь они имели в виду вещественная, т.е. материальная жизнь людей и духовная деятельность. Иными словами своеобразное производство самой материальной жизни.

В XX в. экзистенциальная философия способствует развитию мысли о том, что требуется пересмотр подхода к исследованию вида бытия. Имелось в виду, что мир стал приобретать человеческое измерение, и бытие стало бытием человека.

В новых исследования человеческое бытие стало интересовать исследователей, и это новое понимание стало основным предметом познания, а именно познание человеческого бытия. Выдающиеся мыслители как М. Хайдеггер, А. Камю, К. Ясперс, Ж.-П. Сартр, Н. Бердяев, Н. Гартман и др. приложили огромные усилия, чтобы раскрыть эту проблематику.

Хайдеггер о проблеме бытия

Труды М. Хайдеггера «Бытие и время» и «Введение в метафизику» отражают в себе кардинально новый подход к раскрытию понятия бытия. В своих работах Хайдеггер говорит о том, что пришло время переосмыслить понятие бытия, ведь именно этот вопрос является ключевым во всей философской науке.

М. Хайдеггер писал: «Вопрос о смысле бытия должен быть поставлен. Если он фундаментальный вопрос, тем более главный, то нуждается в адекватной прозрачности».

Он яро критикует всю европейскую философию в том, что совершенно незаметно в науке смешались вопросы о проблемах бытия и проблемах сущего. В силу этого современники могут наблюдать, как бытие потеряло свою суть и собственное человеческое измерение.

А ведь на самом деле, суть бытия в раскрытии и выявлении сущности человеческого бытия. Хайдеггер говорит о последствиях, которые ждут человечество, а именно кризис современной эпохи, который последует за забвением бытия. Главными признаками такого кризиса станут нигилизм, обезвоженность мира. Кроме того техника будет править миром и человеческим сознанием.

Хайдеггер утверждает, что фундаментальная онтология, прежде всего, должна спрашивать о бытие. Поскольку бытие дано только в понимании бытия. Главный вопрос онтологии о бытии (имеется в виду происхождение от слова «быть»), определённо несёт под собой объяснение вопроса: «Что значит быть?» Однако проблема в том, что этот вопрос ставит сам человек, а он всегда может зов бытия в момент очищения сущности личности от иллюзий, которые не дают повседневности приобрести личностные черты. Кроме того этот зов может быть услышан и на пути постижения сути языка.

Хайдеггер сформировал своё учение о бытие на основе экзистенциального анализа человеческого существования в целостности его бытия. Интересен тот факт, что сам мыслитель не причислял себя к ряду экзистенциалистов. Его идеи оказали значительное влияние на дальнейшее формирование проблематики бытия, особенно в философии экзистенциализма.

Современным мыслителям присущи идеи о том, что сегодня бытие не существует в, так называемом, автоматическом режиме, по принципу раз и навсегда.

Быть человеком – это означает, перманентно находится в режиме человека, с присущими ему человеческими вещами бок о бок. Под человеческими вещами подразумеваются благо, добро, любовь, честь и разум.

М. К. Мамардашвили писал о том, что все человеческие вещи держатся лишь на волне человеческого старания.

Онтология русской философской мысли

Давая характеристику проблеме бытия в проекции на историю философской науки и мысли можно выделить особенности русской традиционной философии. В.В. Зеньковский в труде «История русской философии» фундаментально выделяет особое значение онтологической проблемы, которая присуща только русской философии.

Несмотря на это, современные учёные говорят с долей скептизма об онтологии русской философской мысли. Все размышления об онтологии русских мыслителей довольно условны, потому как проблематика бытия не была для них самодовлеющей. Проблемы онтологии важны для них только в аспекте основы универсализма, никак иначе.

Достоевский говорил об универсализме как о том, что русская душа способна к отзывчивости как никто другой, в свою очередь, всемирная отзывчивость носит глубинный философский смысл. Эти слова он произнёс на Пушкинском празднике, и его речь нашла свою популярность во всём мире.

Отзывчивость во всемирном понимании определена как опора на любовь, т.е. как онтологический фундамент личностного бытия. И напротив, совершенно безличная категория «бытие» из понятия бинарной пары «бытие=ничто», занимает наиважнейшее место в религиозной философской мысли. Более того, становится основной проблемой теоретической философии и практического познания, тем самым организуя индивидуально-личностное бытие, которое, в свою очередь, является более религиозным по своим признакам и генезису.

Именно это и стало основополагающими факторами в проработке онтологии и наиболее значимых идей русской философии XIX–XX вв.

This article is about ontology in philosophy. For the concept in information science and computing, see Ontology (information science).

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities exist on the most fundamental level. Ontologists often try to determine what the categories or highest kinds are and how they form a system of categories that encompasses the classification of all entities. Commonly proposed categories include substances, properties, relations, states of affairs, and events. These categories are characterized by fundamental ontological concepts, including particularity and universality, abstractness and concreteness, or possibility and necessity. Of special interest is the concept of ontological dependence, which determines whether the entities of a category exist on the most fundamental level. Disagreements within ontology are often about whether entities belonging to a certain category exist and, if so, how they are related to other entities.[1]

When used as a countable noun, the words ontology and ontologies refer not to the science of being but to theories within the science of being. Ontological theories can be divided into various types according to their theoretical commitments. Monocategorical ontologies hold that there is only one basic category, but polycategorical ontologies rejected this view. Hierarchical ontologies assert that some entities exist on a more fundamental level and that other entities depend on them. Flat ontologies, on the other hand, deny such a privileged status to any entity.

Etymology[edit]

The compound word ontology (‘study of being’) combines

- onto- (Greek: ὄν, on;[note 1] GEN. ὄντος, ontos, ‘being’ or ‘that which is’) and

- -logia (-λογία, ‘logical discourse’).[2][3]

While the etymology is Greek, the oldest extant records of the word itself is a New Latin form ontologia, which appeared

- in 1606 in the Ogdoas Scholastica by Jacob Lorhard (Lorhardus), and

- in 1613 in the Lexicon philosophicum by Rudolf Göckel (Goclenius).

The first occurrence in English of ontology, as recorded by the Oxford English Dictionary,[4] came in 1664 through Archelogia philosophica nova… by Gideon Harvey.[5] The word was first used, in its Latin form, by philosophers, and based on the Latin roots (and in turn on the Greek ones).

Overview[edit]

Ontology is closely associated with Aristotle’s question of ‘being qua being’: the question of what all entities in the widest sense have in common.[6][7] The Eleatic principle is one answer to this question: it states that being is inextricably tied to causation, that «Power is the mark of Being».[6] One problem with this answer is that it excludes abstract objects. Another explicit but little accepted answer can be found in Berkeley’s slogan that «to be is to be perceived».[8] Intimately related but not identical to the question of ‘being qua being’ is the problem of categories.[6] Categories are usually seen as the highest kinds or genera.[9] A system of categories provides a classification of entities that is exclusive and exhaustive: every entity belongs to exactly one category. Various such classifications have been proposed, they often include categories for substances, properties, relations, states of affairs or events.[6][10] At the core of the differentiation between categories are various fundamental ontological concepts and distinctions, for example, the concepts of particularity and universality, of abstractness and concreteness, of ontological dependence, of identity and of modality.[6][10] These concepts are sometimes treated as categories themselves, are used to explain the difference between categories or play other central roles for characterizing different ontological theories. Within ontology, there is a lack of general consensus concerning how the different categories are to be defined.[9] Different ontologists often disagree on whether a certain category has any members at all or whether a given category is fundamental.[10]

Particulars and universals[edit]

Particulars or individuals are usually contrasted with universals.[11][12] Universals concern features that can be exemplified by various different particulars.[13] For example, a tomato and a strawberry are two particulars that exemplify the universal redness. Universals can be present at various distinct locations in space at the same time while particulars are restricted to one location at a time. Furthermore, universals can be fully present at different times, which is why they are sometimes referred to as repeatables in contrast to non-repeatable particulars.[10] The so-called problem of universals is the problem to explain how different things can agree in their features, e.g. how a tomato and a strawberry can both be red.[6][13] Realists about universals believe that there are universals. They can solve the problem of universals by explaining the commonality through a universal shared by both entities.[10] Realists are divided among themselves as to whether universals can exist independently of being exemplified by something («ante res») or not («in rebus»).[14] Nominalists, on the other hand, deny that there are universals. They have to resort to other notions to explain how a feature can be common to several entities, for example, by positing either fundamental resemblance-relations between the entities (resemblance nominalism) or a shared membership to a common natural class (class nominalism).[10]

Abstract and concrete[edit]

Many philosophers agree that there is an exclusive and exhaustive distinction between concrete objects and abstract objects.[10] Some philosophers consider this to be the most general division of being.[15] Examples of concrete objects include plants, human beings and planets while things like numbers, sets and propositions are abstract objects.[16] But despite the general agreement concerning the paradigm cases, there is less consensus as to what the characteristic marks of concreteness and abstractness are. Popular suggestions include defining the distinction in terms of the difference between (1) existence inside or outside space-time, (2) having causes and effects or not and (3) having contingent or necessary existence.[17][18]

Ontological dependence[edit]

An entity ontologically depends on another entity if the first entity cannot exist without the second entity. Ontologically independent entities, on the other hand, can exist all by themselves.[19] For example, the surface of an apple cannot exist without the apple and so depends on it ontologically.[20] Entities often characterized as ontologically dependent include properties, which depend on their bearers, and boundaries, which depend on the entity they demarcate from its surroundings.[21] As these examples suggest, ontological dependence is to be distinguished from causal dependence, in which an effect depends for its existence on a cause. It is often important to draw a distinction between two types of ontological dependence: rigid and generic.[21][10] Rigid dependence concerns the dependence on one specific entity, as the surface of an apple depends on its specific apple.[22] Generic dependence, on the other hand, involves a weaker form of dependence, on merely a certain type of entity. For example, electricity generically depends on there being charged particles, but it does not depend on any specific charged particle.[21] Dependence-relations are relevant to ontology since it is often held that ontologically dependent entities have a less robust form of being. This way a hierarchy is introduced into the world that brings with it the distinction between more and less fundamental entities.[21]

Identity[edit]

Identity is a basic ontological concept that is often expressed by the word «same».[10][23] It is important to distinguish between qualitative identity and numerical identity. For example, consider two children with identical bicycles engaged in a race while their mother is watching. The two children have the same bicycle in one sense (qualitative identity) and the same mother in another sense (numerical identity).[10] Two qualitatively identical things are often said to be indiscernible. The two senses of sameness are linked by two principles: the principle of indiscernibility of identicals and the principle of identity of indiscernibles. The principle of indiscernibility of identicals is uncontroversial and states that if two entities are numerically identical with each other then they exactly resemble each other.[23] The principle of identity of indiscernibles, on the other hand, is more controversial in making the converse claim that if two entities exactly resemble each other then they must be numerically identical.[23] This entails that «no two distinct things exactly resemble each other».[24] A well-known counterexample comes from Max Black, who describes a symmetrical universe consisting of only two spheres with the same features.[25] Black argues that the two spheres are indiscernible but not identical, thereby constituting a violation of the principle of identity of indiscernibles.[26]

The problem of identity over time concerns the question of persistence: whether or in what sense two objects at different times can be numerically identical. This is usually referred to as diachronic identity in contrast to synchronic identity.[23][27] The statement that «[t]he table in the next room is identical with the one you purchased last year» asserts diachronic identity between the table now and the table then.[27] A famous example of a denial of diachronic identity comes from Heraclitus, who argues that it is impossible to step into the same river twice because of the changes that occurred in-between.[23][28] The traditional position on the problem of persistence is endurantism, the thesis that diachronic identity in a strict sense is possible. One problem with this position is that it seems to violate the principle of indiscernibility of identicals: the object may have undergone changes in the meantime resulting in it being discernible from itself.[10] Perdurantism or four-dimensionalism is an alternative approach holding that diachronic identity is possible only in a loose sense: while the two objects differ from each other strictly speaking, they are both temporal parts that belong to the same temporally extended whole.[10][29] Perdurantism avoids many philosophical problems plaguing endurantism, but endurantism seems to be more in touch with how we ordinarily conceive diachronic identity.[27][28]

Modality[edit]

Modality concerns the concepts of possibility, actuality and necessity. In contemporary discourse, these concepts are often defined in terms of possible worlds.[10] A possible world is a complete way how things could have been.[30] The actual world is one possible world among others: things could have been different from what they actually are. A proposition is possibly true if there is at least one possible world in which it is true; it is necessarily true if it is true in all possible worlds.[31] Actualists and possibilists disagree on the ontological status of possible worlds.[10] Actualists hold that reality is at its core actual and that possible worlds should be understood in terms of actual entities, for example, as fictions or as sets of sentences.[32] Possibilists, on the other hand, assign to possible worlds the same fundamental ontological status as to the actual world. This is a form of modal realism, holding that reality has irreducibly modal features.[32] Another important issue in this field concerns the distinction between contingent and necessary beings.[10] Contingent beings are beings whose existence is possible but not necessary. Necessary beings, on the other hand, could not have failed to exist.[33][34] It has been suggested that this distinction is the highest division of being.[10][35]

Substances[edit]

The category of substances has played a central role in many ontological theories throughout the history of philosophy.[36][37] «Substance» is a technical term within philosophy not to be confused with the more common usage in the sense of chemical substances like gold or sulfur. Various definitions have been given but among the most common features ascribed to substances in the philosophical sense is that they are particulars that are ontologically independent: they are able to exist all by themselves.[36][6] Being ontologically independent, substances can play the role of fundamental entities in the ontological hierarchy.[21][37] If ‘ontological independence’ is defined as including causal independence then only self-caused entities, like Spinoza’s God, can be substances. With a specifically ontological definition of ‘independence’, many everyday objects like books or cats may qualify as substances.[6][36] Another defining feature often attributed to substances is their ability to undergo changes. Changes involve something existing before, during and after the change. They can be described in terms of a persisting substance gaining or losing properties, or of matter changing its form.[36] From this perspective, the ripening of a tomato may be described as a change in which the tomato loses its greenness and gains its redness. It is sometimes held that a substance can have a property in two ways: essentially and accidentally. A substance can survive a change of accidental properties but it cannot lose its essential properties, which constitute its nature.[37][38]

Properties and relations[edit]

The category of properties consists of entities that can be exemplified by other entities, e.g. by substances.[39] Properties characterize their bearers, they express what their bearer is like.[6] For example, the red color and the round shape of an apple are properties of this apple. Various ways have been suggested concerning how to conceive properties themselves and their relation to substances.[10] The traditionally dominant view is that properties are universals that inhere in their bearers.[6] As universals, they can be shared by different substances. Nominalists, on the other hand, deny that universals exist.[13] Some nominalists try to account for properties in terms of resemblance relations or class membership.[10] Another alternative for nominalists is to conceptualize properties as simple particulars, so-called tropes.[6] This position entails that both the apple and its redness are particulars. Different apples may still exactly resemble each other concerning their color, but they do not share the same particular property on this view: the two color-tropes are numerically distinct.[13] Another important question for any theory of properties is how to conceive the relation between a bearer and its properties.[10] Substratum theorists hold that there is some kind of substance, substratum or bare particular that acts as bearer.[40] Bundle theory is an alternative view that does away with a substratum altogether: objects are taken to be just a bundle of properties.[37][41] They are held together not by a substratum but by the so-called compresence-relation responsible for the bundling. Both substratum theory and bundle theory can be combined with conceptualizing properties as universals or as particulars.[40]

An important distinction among properties is between categorical and dispositional properties.[6][42] Categorical properties concern what something is like, e.g. what qualities it has. Dispositional properties, on the other hand, involve what powers something has, what it is able to do, even if it is not actually doing it.[6] For example, the shape of a sugar cube is a categorical property while its tendency to dissolve in water is a dispositional property. For many properties there is a lack of consensus as to how they should be classified, for example, whether colors are categorical or dispositional properties.[43][44] Categoricalism is the thesis that on a fundamental level there are only categorical properties, that dispositional properties are either non-existent or dependent on categorical properties. Dispositionalism is the opposite theory, giving ontological primacy to dispositional properties.[43][42] Between these two extremes, there are dualists who allow both categorical and dispositional properties in their ontology.[39]

Relations are ways in which things, the relata, stand to each other.[6][45] Relations are in many ways similar to properties in that both characterize the things they apply to. Properties are sometimes treated as a special case of relations involving only one relatum.[39] Central for ontology is the distinction between internal and external relations.[46] A relation is internal if it is fully determined by the features of its relata.[47] For example, an apple and a tomato stand in the internal relation of similarity to each other because they are both red.[48] Some philosophers have inferred from this that internal relations do not have a proper ontological status since they can be reduced to intrinsic properties.[46][49] External relations, on the other hand, are not fixed by the features of their relata. For example, a book stands in an external relation to a table by lying on top of it. But this is not determined by the book’s or the table’s features like their color, their shape, etc.[46]

States of affairs and events[edit]

States of affairs are complex entities, in contrast to substances and properties, which are usually conceived as simple.[6][50] Complex entities are built up from or constituted by other entities. Atomic states of affairs are constituted by one particular and one property exemplified by this particular.[10][51] For example, the state of affairs that Socrates is wise is constituted by the particular «Socrates» and the property «wise». Relational states of affairs involve several particulars and a relation connecting them. States of affairs that obtain are also referred to as facts.[51] It is controversial which ontological status should be ascribed to states of affairs that do not obtain.[10] States of affairs have been prominent in 20th-century ontology as various theories were proposed to describe the world as composed of states of affairs.[6][52][53] It is often held that states of affairs play the role of truthmakers: judgments or assertions are true because the corresponding state of affairs obtains.[51][54]