На протяжении веков люди обвиняли полнолуние во многих грехах, в частности, считали его причиной странного, девиантного поведения. В средневековье процветали истории о том, как полная луна превращает людей в оборотней. В XVIII веке бытовало мнение, что полнолуние может вызвать эпилепсию и лихорадку. Даже Шекспир в своей пьесе «Отелло» упоминает этот известный миф:

Отелло

Виновно отклонение луны:

Она как раз приблизилась к земле,

И у людей мутится разум.

Все эти казалось бы фантастические истории находят отражение в нашем языке и сейчас: например, слово «лунатик» (т.е. человек, который совершает какие-либо действия в состоянии сна) происходит от латинского корня «luna».

В XXI веке мы уже не верим мифам, опираясь в своих суждениях на разум и научно доказанные факты. Люди больше не обвиняют фазы Луны в болезнях и недомоганиях. Тем не менее, даже сегодня порой можно услышать, как кто-то именно влиянием полнолуния объясняет безумное поведение. Например, когда в психиатрической больнице начинается «аврал», медсестры часто говорят: «Должно быть, сегодня полнолуние».

- 8 типичных ошибок мыслительного процесса

Почему так происходит: наука vs. мифы

Между тем, существует не так много доказательств того, что полная фаза Луны действительно влияет на наше поведение. Анализ более чем 30 исследований показал, что нет никакой корреляции между фазами Луны и выигрышами в казино, количеством госпитализированных, числом самоубийств или дорожно-транспортных происшествий, уровнем преступности и многими другими показателями.

Но вот что любопытно: хотя все факты говорят об обратном, проведенное в 2005 году исследование показало, что 7 из 10 медсестер по-прежнему верят в миф о том, что полнолуние приводит к хаосу и странному поведению больных психиатрической клиники. По данным эксперимента, подавляющее большинство сотрудниц больницы (69 %!) верят во влияние полной фазы Луны на количество госпитализированных.

Не стоит думать, что медсестры, которые клянутся, что полнолуние вызывает странное поведение, глупы и поэтому верят во всякую ерунду. Они просто стали жертвами распространенной психологической ошибки, которую совершают многие из нас. Специалисты именуют этот небольшой «сбой» в работе нашего мозга «иллюзорными корреляциями» (illusory correlation).

- Когнитивная психология: Почему мы верим заблуждениям?

Как мы обманываем себя, не осознавая этого

Иллюзорная корреляция возникает в тех случаях, когда мы ошибочно придаем повышенное значение одному элементу и при этом игнорируем все другие. Представьте, что вы приехали в большой незнакомый город, спускаетесь в метро и… вдруг кто-то «подрезает» вас перед самым входом в вагон. Добравшись до нужной станции, вы решаете пообедать и заходите в ближайший ресторан, но… официант открыто хамит вам. На улице вы понимаете, что потерялись, спрашиваете дорогу у прохожего и … вам показывают неверное направление. Приехав домой, вы, скорее всего, будете рассказывать родственникам о том, какие неудачи постигли вас в путешествии (еще бы, вы ведь запомнили только эту «полосу невезения»!), доказывать, что обитатели мегаполисов грубы и невоспитаны.

Однако в своем рассказе вы, скорее всего, забудете упомянуть про вкусную еду, которую попробовали в ресторане, про сотни других людей в метро, которые не толкали вас на платформе. Все эти мелочи были так незаметны, что мы не придаем им никакого значения, они даже не получают статус событий в нашей жизни. Это, скорее, «не-события». В результате получается, что легче запомнить, когда кто-то нахамил вам, чем когда вы вкусно пообедали или благополучно зашли в вагон метро.

В игру вступает наука о мозге

Сотни психологических исследований доказали, что мы склонны переоценивать важность событий, которые легко запоминаются, и недооценивать те моменты жизни, которые сложно восстановить в памяти. Принцип работы нашего мозга в этом случае прост: чем легче событие запомнилось, тем сильнее будет связь между ним и другим событием. Но на самом деле данные явления могут быть слабо связаны или не связаны друг с другом вообще.

В психологии этот феномен называется «эвристика доступности» (availability heuristic). Чем легче вспоминается какой-то момент нашей жизни (чем более он доступен), тем больше вероятность того, что мы переоценим его значение.

Иллюзорная корреляция — это своего рода сочетание эвристики доступности и такого когнитивного искажения как «предвзятость подтверждения» (тенденция интерпретировать информацию таким образом, чтобы подтвердить имеющиеся концепции).

Вы можете легко вспомнить какой-то случай (эвристика доступности) и поэтому начинаете думать, что такие случаи повторяются часто и даже складываются в определенную тенденцию. Когда это произойдет снова (как, например, полнолуние в случае с медсёстрами), вы сразу свяжете два явления и подтвердите свои же догадки (предвзятость подтверждения).

Иллюзорная корреляция — это склонность «видеть» множество ассоциаций, которых нет

- 5 когнитивных предубеждений, о которых должен знать каждый маркетолог

Как распознать иллюзорную корреляцию?

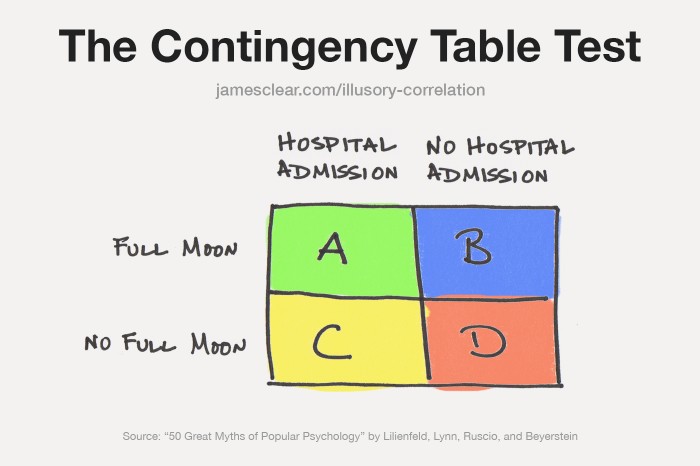

Чтобы определить, где ваш мозг дал «сбой» и защитить себя от воздействия иллюзорных корреляций, можно использовать таблицу случайностей (contingency table), которая поможет определить правомерность ваших суждений и реальную значимость событий.

Вспомним пример с полнолунием:

Клетка А: полнолуние и аврал в психиатрической больнице. Два явления представляют собой хорошо запоминающееся сочетание, поэтому мы в будущем будем переоценивать их значение.

Клетка B: полнолуние и затишье в больнице. Ничего особенного не происходит («не-событие»). Нам будет довольно трудно вспомнить эту ночь, поэтому мы склонны игнорировать данную ячейку.

Клетка C: полнолуния нет, но в больнице аврал. В этой ситуации медсестры просто скажут в конце смены: «Суматошная ночь на работе…».

Клетка D: полнолуния по-прежнему нет, и пациенты ведут себя спокойно. Это снова пример «не-события»: ничего запоминающегося не происходит, поэтому мы проигнорируем эту ночь.

Таблица случайностей демонстрирует тот алгоритм, по которому медсестры анализируют ситуацию во время полнолуния. Они могут быстро вспомнить ту ночь, когда в полнолуние больница была переполнена, но совершенно не учитывают (просто забывают) те многочисленные смены, когда в полнолуние пациенты вели себя обычным образом. Их мозг легко «выдает» информацию об авралах во время полнолуния, именно поэтому они уверены, что эти два события связаны.

Данную таблицу из книги «50 великих мифов популярной психологии» («50 Great Myths of Popular Psychology») можно адаптировать для любых жизненных ситуаций. В большинстве случаев мы уделяем слишком много внимания клетке А, но почти не замечаем клетку В, что может привести к иллюзорной корреляции. Использование всех четырех клеток позволяет вам вычислять реальную корреляцию между двумя событиями и не поддаваться влиянию известных мифов, таких как «эффект полнолуния».

- Искажение реальности или Почему наш мир не такой, каким кажется

Как исправить ошибки нашего мозга?

Оказывается, мы проводим иллюзорные корреляции во многих сферах жизни: Все слышали истории успеха Билла Гейтса (Bill Gates) или Марка Цукерберга (Mark Zuckerberg), которые бросили колледж, чтобы начать бизнес, принесший им миллиарды. Мы придаем повышенное значение этим случаям, обсуждаем их с друзьями и знакомыми. Между тем, вы никогда не услышите о тех нерадивых учениках, которые не добились успеха и не создали всемирно известных компаний. В потоке информации мы улавливаем только самые экстраординарные случаи, собираем «сливки», игнорируя при этом сотни или даже тысячи историй людей, бросивших колледж, но не уложившихся в парадигму успеха.

Если вы слышите, что арестовали представителя определенной этнической группы или расы, то, вероятно, вы будете в дальнейшем воспринимать каждого выходца из этой страны или континента как потенциального бандита. Но при этом вы забываете о тех 99% неизвестных вам людей, которые ведут примерный образ жизни и никогда не были арестованы (потому что арест — это событие, а не-арест — не-событие).

Если мы читаем в новостях о нападении акулы, то отказываемся заходить в океан во время отпуска на побережье. Вероятность нападения не увеличилась с тех пор, как мы плавали в последний раз, ведь мы не учитываем миллионы людей, которые вернулись невредимыми. Но никому не интересны скучные заголовки: «Миллионы туристов остаются живы каждый день», поэтому журналисты делают акцент на экстраординарных случаях, а мы проводим иллюзорную корреляцию и отказываемся от отдыха на побережье.

Когнитивные заблуждения подталкивают нас «видеть» множество ассоциаций, которых нет. Например, многие люди, страдающие артритом, настаивают на том, что их суставы болят больше в дождливую погоду, чем в ясную. Однако исследования показывают, что эта ассоциация — плод их воображения. По-видимому, такие люди обращают слишком большое внимание на клетку А — случаи, когда идет дождь и у них болят суставы, — что заставляет их воспринимать корреляцию, которой не существует.

Многие из нас даже не догадываются, что наша избирательная память о событиях влияет на убеждения, которых мы придерживаемся. Теперь вы знаете о когнитивных искажениях и сможете выявить и устранить иллюзорные корреляции в повседневной жизни с помощью таблицы случайностей.

Высоких вам конверсий!

По материалам: jamesclear.comimage source Thomas Hawk

15-04-2016

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In psychology, illusory correlation is the phenomenon of perceiving a relationship between variables (typically people, events, or behaviors) even when no such relationship exists. A false association may be formed because rare or novel occurrences are more salient and therefore tend to capture one’s attention.[1] This phenomenon is one way stereotypes form and endure.[2][3] Hamilton & Rose (1980) found that stereotypes can lead people to expect certain groups and traits to fit together, and then to overestimate the frequency with which these correlations actually occur.[4] These stereotypes can be learned and perpetuated without any actual contact occurring between the holder of the stereotype and the group it is about.

History[edit]

«Illusory correlation» was originally coined by Chapman and Chapman (1967) to describe people’s tendencies to overestimate relationships between two groups when distinctive and unusual information is presented.[5][6] The concept was used to question claims about objective knowledge in clinical psychology through Chapmans’ refutation of many clinicians’ widely used Wheeler signs for homosexuality in Rorschach tests.[7]

Example[edit]

David Hamilton and Robert Gifford (1976) conducted a series of experiments that demonstrated how stereotypic beliefs regarding minorities could derive from illusory correlation processes.[8] To test their hypothesis, Hamilton and Gifford had research participants read a series of sentences describing either desirable or undesirable behaviors, which were attributed to either Group A (the majority) or Group B (the minority).[5] Abstract groups were used so that no previously established stereotypes would influence results. Most of the sentences were associated with Group A, and the remaining few were associated with Group B.[8] The following table summarizes the information given.

| Behaviors | Group A (majority) | Group B (minority) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Desirable | 18 (69%) | 9 (69%) | 27 |

| Undesirable | 8 (30%) | 4 (30%) | 12 |

| Total | 26 | 13 | 39 |

Each group had the same proportions of positive and negative behaviors, so there was no real association between behaviors and group membership. Results of the study show that positive, desirable behaviors were not seen as distinctive so people were accurate in their associations. On the other hand, when distinctive, undesirable behaviors were represented in the sentences, the participants overestimated how much the minority group exhibited the behaviors.[8]

A parallel effect occurs when people judge whether two events, such as pain and bad weather, are correlated. They rely heavily on the relatively small number of cases where the two events occur together. People pay relatively little attention to the other kinds of observation (of no pain or good weather).[9][10]

Theories[edit]

General theory[edit]

Most explanations for illusory correlation involve psychological heuristics: information processing short-cuts that underlie many human judgments.[11] One of these is availability: the ease with which an idea comes to mind. Availability is often used to estimate how likely an event is or how often it occurs.[12] This can result in illusory correlation, because some pairings can come easily and vividly to mind even though they are not especially frequent.[11]

Information processing[edit]

Martin Hilbert (2012) proposes an information processing mechanism that assumes a noisy conversion of objective observations into subjective judgments. The theory defines noise as the mixing of these observations during retrieval from memory.[13] According to the model, underlying cognitions or subjective judgments are identical with noise or objective observations that can lead to overconfidence or what is known as conservatism bias—when asked about behavior participants underestimate the majority or larger group and overestimate the minority or smaller group. These results are illusory correlations.

Working-memory capacity[edit]

In an experimental study done by Eder, Fiedler and Hamm-Eder (2011), the effects of working-memory capacity on illusory correlations were investigated. They first looked at the individual differences in working memory, and then looked to see if that had any effect on the formation of illusory correlations. They found that individuals with higher working memory capacity viewed minority group members more positively than individuals with lower working memory capacity. In a second experiment, the authors looked into the effects of memory load in working memory on illusory correlations. They found that increased memory load in working memory led to an increase in the prevalence of illusory correlations. The experiment was designed to specifically test working memory and not substantial stimulus memory. This means that the development of illusory correlations was caused by deficiencies in central cognitive resources caused by the load in working memory, not selective recall.[14]

Attention theory of learning[edit]

Attention theory of learning proposes that features of majority groups are learned first, and then features of minority groups. This results in an attempt to distinguish the minority group from the majority, leading to these differences being learned more quickly. The Attention theory also argues that, instead of forming one stereotype regarding the minority group, two stereotypes, one for the majority and one for the minority, are formed.[15]

Effect of learning[edit]

A study was conducted to investigate whether increased learning would have any effect on illusory correlations. It was found that educating people about how illusory correlation occurs resulted in a decreased incidence of illusory correlations.[16]

Age[edit]

Johnson and Jacobs (2003) performed an experiment to see how early in life individuals begin forming illusory correlations. Children in grades 2 and 5 were exposed to a typical illusory correlation paradigm to see if negative attributes were associated with the minority group. The authors found that both groups formed illusory correlations.[17]

A study also found that children create illusory correlations. In their experiment, children in grades 1, 3, 5, and 7, and adults all looked at the same illusory correlation paradigm. The study found that children did create significant illusory correlations, but those correlations were weaker than the ones created by adults. In a second study, groups of shapes with different colors were used. The formation of illusory correlation persisted showing that social stimuli are not necessary for creating these correlations.[18]

Explicit versus implicit attitudes[edit]

Two studies performed by Ratliff and Nosek examined whether or not explicit and implicit attitudes affected illusory correlations. In one study, Ratliff and Nosek had two groups: one a majority and the other a minority. They then had three groups of participants, all with readings about the two groups. One group of participants received overwhelming pro-majority readings, one was given pro-minority readings, and one received neutral readings. The groups that had pro-majority and pro-minority readings favored their respective pro groups both explicitly and implicitly. The group that had neutral readings favored the majority explicitly, but not implicitly. The second study was similar, but instead of readings, pictures of behaviors were shown, and the participants wrote a sentence describing the behavior they saw in the pictures presented. The findings of both studies supported the authors’ argument that the differences found between the explicit and implicit attitudes is a result of the interpretation of the covariation and making judgments based on these interpretations (explicit) instead of just accounting for the covariation (implicit).[19]

Paradigm structure[edit]

Berndsen et al. (1999) wanted to determine if the structure of testing for illusory correlations could lead to the formation of illusory correlations. The hypothesis was that identifying test variables as Group A and Group B might be causing the participants to look for differences between the groups, resulting in the creation of illusory correlations. An experiment was set up where one set of participants were told the groups were Group A and Group B, while another set of participants were given groups labeled as students who graduated in 1993 or 1994. This study found that illusory correlations were more likely to be created when the groups were Group A and B, as compared to students of the class of 1993 or the class of 1994.[20]

See also[edit]

- Apophenia

- Clustering illusion

- Cognitive bias

- Confirmation bias

- Cum hoc ergo propter hoc

- Observer bias

- Observer-expectancy effect

- Pareidolia

- Post hoc ergo propter hoc

- Radical behaviorism

- Subject-expectancy effect

- Superstition

- Thin-slicing

- Type I error

- Spurious relationship

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Pelham, Brett; Blanton, Hart (2013) [2007]. Conducting Research in Psychology: measuring the weight of smoke (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-495-59819-0.

- ^ Mullen, Brian; Johnson, Craig (1990). «Distinctiveness-based illusory correlations and stereotyping: A meta-analytic integration». British Journal of Social Psychology. 29 (1): 11–28. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8309.1990.tb00883.x.

- ^ Stroessner, Steven J.; Plaks, Jason E. (2001). «Illusory Correlation and Stereotype Formation: Tracing the Arc of Research Over a Quarter Century». In Moskowitz, Gordon B. (ed.). Cognitive Social Psychology: The Princeton Symposium on the Legacy and Future of Social Cognition. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 247–259. ISBN 978-0-8058-3414-7.

- ^ Peeters, Vivian E. (1983). «The Persistence of Stereotypic Beliefs: a Cognitive View». In Richard P. Bagozzi; Alice M. Tybout (eds.). Advances in Consumer Research. Vol. 10. Ann Arbor, MI: Association for Consumer Research. pp. 454–458.

- ^ a b Whitley & Kite 2010

- ^ Chapman, L (1967). «Illusory correlation in observational report». Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 6 (1): 151–155. doi:10.1016/S0022-5371(67)80066-5.

- ^ Chapman, Loren J. and Jean P. (1969). «Illusory Correlation as an Obstacle to the Use of Valid Psychodiagnostic Signs». Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 74 (3): 271–80. doi:10.1037/h0027592. PMID 4896551.

- ^ a b c Hamilton, D; Gifford, R (1976). «Illusory correlation in interpersonal perception: A cognitive basis of stereotypic judgments». Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 12 (4): 392–407. doi:10.1016/S0022-1031(76)80006-6.

- ^ Kunda 1999, pp. 127–130

- ^ Plous 1993, pp. 162–164

- ^ a b Plous 1993, pp. 164–167

- ^ Plous 1993, p. 121

- ^ Hilbert, Martin (2012). «Toward a synthesis of cognitive biases: How noisy information processing can bias human decision making» (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 138 (2): 211–237. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.432.8763. doi:10.1037/a0025940. PMID 22122235.

- ^ Eder, Andreas B.; Fiedler, Klaus; Hamm-Eder, Silke (2011). «Illusory correlations revisited: The role of pseudocontingencies and working-memory capacity». The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 64 (3): 517–532. doi:10.1080/17470218.2010.509917. PMID 21218370. S2CID 8964205.

- ^ Sherman, Jeffrey W.; Kruschke, John K.; Sherman, Steven J.; Percy, Elise J.; Petrocelli, John V.; Conrey, Frederica R. (2009). «Attentional processes in stereotype formation: A common model for category accentuation and illusory correlation» (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 96 (2): 305–323. doi:10.1037/a0013778. PMID 19159134.

- ^ Murphy, Robin A.; Schmeer, Stefanie; Vallée-Tourangeau, Frédéric; Mondragón, Esther; Hilton, Denis (2011). «Making the illusory correlation effect appear and then disappear: The effects of increased learning». The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 64 (1): 24–40. doi:10.1080/17470218.2010.493615. PMID 20623441. S2CID 34898086.

- ^ Johnston, Kristen E.; Jacobs, Janis E. (2003). «Children’s Illusory Correlations: The Role of Attentional Bias in Group Impression Formation». Journal of Cognition and Development. 4 (2): 129–160. doi:10.1207/S15327647JCD0402_01. S2CID 143983682.

- ^ Primi, Caterina; Agnoli, Franca (2002). «Children correlate infrequent behaviors with minority groups: a case of illusory correlation». Cognitive Development. 17 (1): 1105–1131. doi:10.1016/S0885-2014(02)00076-X.

- ^ Ratliff, Kate A.; Nosek, Brian A. (2010). «Creating distinct implicit and explicit attitudes with an illusory correlation paradigm». Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 46 (5): 721–728. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2010.04.011.

- ^ Berndsen, Mariëtte; Spears, Russell; Pligt, Joop; McGarty, Craig (1999). «Determinants of intergroup differentiation in the illusory correlation task». British Journal of Psychology. 90 (2): 201–220. doi:10.1348/000712699161350.

Sources[edit]

- Hamilton, David L.; Rose, Terrence L. (1980). «Illusory correlation and the maintenance of stereotypic beliefs». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 39 (5): 832–845. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.39.5.832.

- Kunda, Ziva (1999). Social Cognition: Making Sense of People. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-61143-5. OCLC 40618974.

- Plous, Scott (1993). The Psychology of Judgment and Decision Making. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-050477-6. OCLC 26931106.

- Whitley, Bernard E.; Kite, Mary E. (2010). The Psychology of Prejudice and Discrimination. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. ISBN 978-0-495-59964-7. OCLC 695689517.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In psychology, illusory correlation is the phenomenon of perceiving a relationship between variables (typically people, events, or behaviors) even when no such relationship exists. A false association may be formed because rare or novel occurrences are more salient and therefore tend to capture one’s attention.[1] This phenomenon is one way stereotypes form and endure.[2][3] Hamilton & Rose (1980) found that stereotypes can lead people to expect certain groups and traits to fit together, and then to overestimate the frequency with which these correlations actually occur.[4] These stereotypes can be learned and perpetuated without any actual contact occurring between the holder of the stereotype and the group it is about.

History[edit]

«Illusory correlation» was originally coined by Chapman and Chapman (1967) to describe people’s tendencies to overestimate relationships between two groups when distinctive and unusual information is presented.[5][6] The concept was used to question claims about objective knowledge in clinical psychology through Chapmans’ refutation of many clinicians’ widely used Wheeler signs for homosexuality in Rorschach tests.[7]

Example[edit]

David Hamilton and Robert Gifford (1976) conducted a series of experiments that demonstrated how stereotypic beliefs regarding minorities could derive from illusory correlation processes.[8] To test their hypothesis, Hamilton and Gifford had research participants read a series of sentences describing either desirable or undesirable behaviors, which were attributed to either Group A (the majority) or Group B (the minority).[5] Abstract groups were used so that no previously established stereotypes would influence results. Most of the sentences were associated with Group A, and the remaining few were associated with Group B.[8] The following table summarizes the information given.

| Behaviors | Group A (majority) | Group B (minority) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Desirable | 18 (69%) | 9 (69%) | 27 |

| Undesirable | 8 (30%) | 4 (30%) | 12 |

| Total | 26 | 13 | 39 |

Each group had the same proportions of positive and negative behaviors, so there was no real association between behaviors and group membership. Results of the study show that positive, desirable behaviors were not seen as distinctive so people were accurate in their associations. On the other hand, when distinctive, undesirable behaviors were represented in the sentences, the participants overestimated how much the minority group exhibited the behaviors.[8]

A parallel effect occurs when people judge whether two events, such as pain and bad weather, are correlated. They rely heavily on the relatively small number of cases where the two events occur together. People pay relatively little attention to the other kinds of observation (of no pain or good weather).[9][10]

Theories[edit]

General theory[edit]

Most explanations for illusory correlation involve psychological heuristics: information processing short-cuts that underlie many human judgments.[11] One of these is availability: the ease with which an idea comes to mind. Availability is often used to estimate how likely an event is or how often it occurs.[12] This can result in illusory correlation, because some pairings can come easily and vividly to mind even though they are not especially frequent.[11]

Information processing[edit]

Martin Hilbert (2012) proposes an information processing mechanism that assumes a noisy conversion of objective observations into subjective judgments. The theory defines noise as the mixing of these observations during retrieval from memory.[13] According to the model, underlying cognitions or subjective judgments are identical with noise or objective observations that can lead to overconfidence or what is known as conservatism bias—when asked about behavior participants underestimate the majority or larger group and overestimate the minority or smaller group. These results are illusory correlations.

Working-memory capacity[edit]

In an experimental study done by Eder, Fiedler and Hamm-Eder (2011), the effects of working-memory capacity on illusory correlations were investigated. They first looked at the individual differences in working memory, and then looked to see if that had any effect on the formation of illusory correlations. They found that individuals with higher working memory capacity viewed minority group members more positively than individuals with lower working memory capacity. In a second experiment, the authors looked into the effects of memory load in working memory on illusory correlations. They found that increased memory load in working memory led to an increase in the prevalence of illusory correlations. The experiment was designed to specifically test working memory and not substantial stimulus memory. This means that the development of illusory correlations was caused by deficiencies in central cognitive resources caused by the load in working memory, not selective recall.[14]

Attention theory of learning[edit]

Attention theory of learning proposes that features of majority groups are learned first, and then features of minority groups. This results in an attempt to distinguish the minority group from the majority, leading to these differences being learned more quickly. The Attention theory also argues that, instead of forming one stereotype regarding the minority group, two stereotypes, one for the majority and one for the minority, are formed.[15]

Effect of learning[edit]

A study was conducted to investigate whether increased learning would have any effect on illusory correlations. It was found that educating people about how illusory correlation occurs resulted in a decreased incidence of illusory correlations.[16]

Age[edit]

Johnson and Jacobs (2003) performed an experiment to see how early in life individuals begin forming illusory correlations. Children in grades 2 and 5 were exposed to a typical illusory correlation paradigm to see if negative attributes were associated with the minority group. The authors found that both groups formed illusory correlations.[17]

A study also found that children create illusory correlations. In their experiment, children in grades 1, 3, 5, and 7, and adults all looked at the same illusory correlation paradigm. The study found that children did create significant illusory correlations, but those correlations were weaker than the ones created by adults. In a second study, groups of shapes with different colors were used. The formation of illusory correlation persisted showing that social stimuli are not necessary for creating these correlations.[18]

Explicit versus implicit attitudes[edit]

Two studies performed by Ratliff and Nosek examined whether or not explicit and implicit attitudes affected illusory correlations. In one study, Ratliff and Nosek had two groups: one a majority and the other a minority. They then had three groups of participants, all with readings about the two groups. One group of participants received overwhelming pro-majority readings, one was given pro-minority readings, and one received neutral readings. The groups that had pro-majority and pro-minority readings favored their respective pro groups both explicitly and implicitly. The group that had neutral readings favored the majority explicitly, but not implicitly. The second study was similar, but instead of readings, pictures of behaviors were shown, and the participants wrote a sentence describing the behavior they saw in the pictures presented. The findings of both studies supported the authors’ argument that the differences found between the explicit and implicit attitudes is a result of the interpretation of the covariation and making judgments based on these interpretations (explicit) instead of just accounting for the covariation (implicit).[19]

Paradigm structure[edit]

Berndsen et al. (1999) wanted to determine if the structure of testing for illusory correlations could lead to the formation of illusory correlations. The hypothesis was that identifying test variables as Group A and Group B might be causing the participants to look for differences between the groups, resulting in the creation of illusory correlations. An experiment was set up where one set of participants were told the groups were Group A and Group B, while another set of participants were given groups labeled as students who graduated in 1993 or 1994. This study found that illusory correlations were more likely to be created when the groups were Group A and B, as compared to students of the class of 1993 or the class of 1994.[20]

See also[edit]

- Apophenia

- Clustering illusion

- Cognitive bias

- Confirmation bias

- Cum hoc ergo propter hoc

- Observer bias

- Observer-expectancy effect

- Pareidolia

- Post hoc ergo propter hoc

- Radical behaviorism

- Subject-expectancy effect

- Superstition

- Thin-slicing

- Type I error

- Spurious relationship

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Pelham, Brett; Blanton, Hart (2013) [2007]. Conducting Research in Psychology: measuring the weight of smoke (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-495-59819-0.

- ^ Mullen, Brian; Johnson, Craig (1990). «Distinctiveness-based illusory correlations and stereotyping: A meta-analytic integration». British Journal of Social Psychology. 29 (1): 11–28. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8309.1990.tb00883.x.

- ^ Stroessner, Steven J.; Plaks, Jason E. (2001). «Illusory Correlation and Stereotype Formation: Tracing the Arc of Research Over a Quarter Century». In Moskowitz, Gordon B. (ed.). Cognitive Social Psychology: The Princeton Symposium on the Legacy and Future of Social Cognition. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 247–259. ISBN 978-0-8058-3414-7.

- ^ Peeters, Vivian E. (1983). «The Persistence of Stereotypic Beliefs: a Cognitive View». In Richard P. Bagozzi; Alice M. Tybout (eds.). Advances in Consumer Research. Vol. 10. Ann Arbor, MI: Association for Consumer Research. pp. 454–458.

- ^ a b Whitley & Kite 2010

- ^ Chapman, L (1967). «Illusory correlation in observational report». Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 6 (1): 151–155. doi:10.1016/S0022-5371(67)80066-5.

- ^ Chapman, Loren J. and Jean P. (1969). «Illusory Correlation as an Obstacle to the Use of Valid Psychodiagnostic Signs». Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 74 (3): 271–80. doi:10.1037/h0027592. PMID 4896551.

- ^ a b c Hamilton, D; Gifford, R (1976). «Illusory correlation in interpersonal perception: A cognitive basis of stereotypic judgments». Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 12 (4): 392–407. doi:10.1016/S0022-1031(76)80006-6.

- ^ Kunda 1999, pp. 127–130

- ^ Plous 1993, pp. 162–164

- ^ a b Plous 1993, pp. 164–167

- ^ Plous 1993, p. 121

- ^ Hilbert, Martin (2012). «Toward a synthesis of cognitive biases: How noisy information processing can bias human decision making» (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 138 (2): 211–237. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.432.8763. doi:10.1037/a0025940. PMID 22122235.

- ^ Eder, Andreas B.; Fiedler, Klaus; Hamm-Eder, Silke (2011). «Illusory correlations revisited: The role of pseudocontingencies and working-memory capacity». The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 64 (3): 517–532. doi:10.1080/17470218.2010.509917. PMID 21218370. S2CID 8964205.

- ^ Sherman, Jeffrey W.; Kruschke, John K.; Sherman, Steven J.; Percy, Elise J.; Petrocelli, John V.; Conrey, Frederica R. (2009). «Attentional processes in stereotype formation: A common model for category accentuation and illusory correlation» (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 96 (2): 305–323. doi:10.1037/a0013778. PMID 19159134.

- ^ Murphy, Robin A.; Schmeer, Stefanie; Vallée-Tourangeau, Frédéric; Mondragón, Esther; Hilton, Denis (2011). «Making the illusory correlation effect appear and then disappear: The effects of increased learning». The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 64 (1): 24–40. doi:10.1080/17470218.2010.493615. PMID 20623441. S2CID 34898086.

- ^ Johnston, Kristen E.; Jacobs, Janis E. (2003). «Children’s Illusory Correlations: The Role of Attentional Bias in Group Impression Formation». Journal of Cognition and Development. 4 (2): 129–160. doi:10.1207/S15327647JCD0402_01. S2CID 143983682.

- ^ Primi, Caterina; Agnoli, Franca (2002). «Children correlate infrequent behaviors with minority groups: a case of illusory correlation». Cognitive Development. 17 (1): 1105–1131. doi:10.1016/S0885-2014(02)00076-X.

- ^ Ratliff, Kate A.; Nosek, Brian A. (2010). «Creating distinct implicit and explicit attitudes with an illusory correlation paradigm». Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 46 (5): 721–728. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2010.04.011.

- ^ Berndsen, Mariëtte; Spears, Russell; Pligt, Joop; McGarty, Craig (1999). «Determinants of intergroup differentiation in the illusory correlation task». British Journal of Psychology. 90 (2): 201–220. doi:10.1348/000712699161350.

Sources[edit]

- Hamilton, David L.; Rose, Terrence L. (1980). «Illusory correlation and the maintenance of stereotypic beliefs». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 39 (5): 832–845. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.39.5.832.

- Kunda, Ziva (1999). Social Cognition: Making Sense of People. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-61143-5. OCLC 40618974.

- Plous, Scott (1993). The Psychology of Judgment and Decision Making. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-050477-6. OCLC 26931106.

- Whitley, Bernard E.; Kite, Mary E. (2010). The Psychology of Prejudice and Discrimination. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. ISBN 978-0-495-59964-7. OCLC 695689517.

Поиск взаимосвязей между событиями — одна из наиболее интересных человеческих черт. На ней основываются не только тысячелетия научных исследований, но и в целом наше понимание действительности: события легче всего интерпретировать через связь с другими событиями. Тем не менее, подобная связь зачастую оказывается ложной — в этом случае человек оказывается подвержен когнитивному искажению, называемому «иллюзорной корреляцией». Сегодня наш блог расскажет о том, как «иллюзорная корреляция» может повлиять на результаты психологических и психических исследований, а также о том, как с ее помощью формируются стереотипы.

Существует достаточно распространенное мнение, согласно которому женщины плохо водят. Довольно обширный список гонщиц, предлагаемый Википедией, говорит о том, что это не так. Соответственно, такое мнение, скорее всего, — стереотип: завидев на дороге среди оживленного движения относительно медленно едущий автомобиль, многие водители, скорее всего, подумают, что за рулем женщина — и не преминут отпустить нелестное замечание на этот счет.

Да, за рулем действительно может быть женщина — но с вероятностью 50 процентов (или с другой — в зависимости от количества машин на дороге, распределения полов среди населения и других факторов). Несмотря на это, в сознании рядового водителя все равно будет существовать устойчивая связь между медленно едущим автомобилем, с одной стороны, и женщиной за рулем, с другой. Такая статистически неподтвержденная связь называется «иллюзорной корреляцией», а ее роль в формировании стереотипов впервые была изучена в середине 1970-х годов.

Американские психологи Дэвид Хэмилтон (David Hamilton) и Роберт Гиффорд (Robert Gifford) поставили эксперимент, предоставив его участникам описания — отрицательные и положительные — двух групп людей. Первая группа отличалась от другой численностью (там людей было больше), но не количеством присущих им черт. Тем не менее, когда участники эксперимента описывали группы, малочисленной они приписывали больше отрицательных признаков, чем их было на самом деле. Все потому, что меньшую по численности группу они оценивали как «меньшинство» — и, скорее всего, приписывали ей обличье расовых или культурных меньшинств.

Сам эффект в научной литературе встречался и раньше: впервые его описал Лорен Чапмен (Loren Chapman) из Университета Южного Иллинойса в 1967 году. В соответствии с его определением, это когнитивное искажение проявляется в ситуациях, когда люди связывают два события, либо не связанные в реальности, либо связанные в меньшей степени, чем им кажется, либо связанные в противоположном смысле (то есть на самом деле наблюдается обратная корреляция).

Для того чтобы экспериментально доказать существование такого эффекта, Чапмен провел эксперимент, в ходе которого участникам показывали 12 пар слов (каждую — по несколько раз в случайном порядке в течение двух секунд). Некоторые слова в парах хорошо сочетались друг с другом по смыслу (например, «лев — тигр» или «хлеб — масло»), некоторые слабо сочетались семантически (например, «часы — нога»), а другие были схожи по длине, но не сочетались по значению (например, «здание» и «журнал»).

Пары слов из трех разных групп появлялись на экране с одинаковой периодичностью (каждая группа занимала ровно треть экспериментального времени); тем не менее, когда у участников спросили, как часто на экране появлялась пара слов, относящаяся к той или иной группе, они сообщали о том, что близкие по значению и одинаковые по длине слова встречались гораздо чаще.

Чапмен и его жена Джин (также психолог) ввели и исследовали понятие «иллюзорной корреляции» во многом для того, чтобы указать на невалидность популярного в то время анализа пятен Роршаха для определения гомосексуальности. В 60-е годы прошлого столетия гомосексуальность считалась психическим заболеванием, а для диагностики психиатры чаще всего использовали именно тест Роршаха: в случае, если пациент видел в пятне женские или мужские гениталии, женскую одежду, людей без половых признаков или с признаками обоих полов, психиатр мог подозревать у него гомосексуальность.

На деле же эти показатели, пусть и были «очевидными», указывали на гомосексуальность далеко не всегда: гетеросексуальные мужчины видели перечисленные выше картины так же часто, как и гомосексуальные, а более валидными показателями, исходя из литературы по психопатологии того времени, считались образы монстров и людей с телами животных.

Для того чтобы перенести обнаруженный ранее феномен на клиническую практику, Чапмены провели эксперимент, в ходе которого попросили студентов определить наиболее вероятные для гомосексуалов интерпретации изображений. Студентам раздали карточки, содержавшие как интерпретацию изображений, так и два возможных диагноза. В результате все студенты связали гомосексуальность с наименее валидными, но самыми очевидными показателями: гениталиями и женской одеждой.

Гомосексуальность давно не считается психическим расстройством, но эффект «иллюзорной корреляции» все еще может воздействовать на диагностику других состояний, объективно оценить которые бывает непросто. Например, исследование, проведенное в 1995 году, показало, что школьные психологи — как раз под воздействием «иллюзорной корреляции» — находили у детей отклонения на основании того, что их ответы на различные стандартизированные тесты, данные в разное время, были непохожи между собой, хотя на деле ни одна из проведенных до этого работ не указывала на такую связь.

«Иллюзорную корреляцию» принято объяснять в первую очередь тем, как люди принимают решения и мыслят. В любых когнитивных процессах человек полагается на самое простое решение, не требующее большого количества затрат. Это же касается и построения связей между событиями: в соответствии с интуитивным процессом «эвристики доступности» человек привязывает к одному событию другое, если оно чаще — также в связи с этим событием — приходит на ум.

Другими словами, в случае, если событие надо к чему-то привязать, оно с большей вероятностью будет привязано к чему-то, что первым придет на ум: пусть на деле такая связь и иллюзорна.

Нашли опечатку? Выделите фрагмент и нажмите Ctrl+Enter.

-

-

June 27 2013, 22:01

- Еда

- Животные

- Cancel

Иллюзорная корреляция

Возможно, явление иллюзорной корреляции будет легче понять, если назвать его словами «иллюзия связи», а суть иллюзорной корреляции заключается в том, что человек по той или иной причине видит связь между параметрами, свойствами, явлениями, которой на самом деле нет. Обычно иллюзорная корреляция наблюдается в паре «свойство — признак наличия этого свойства». Например, если человек считает, что цвет волос может говорить о степени умственного развития человека, а жесткость волос — о жесткости характера, то речь идет как раз об иллюзорной корреляции. На самом же деле, понятно, никакой связи между цветом волос и интеллектом или между жесткостью волос и характером нет.

Экспериментально явление иллюзорной корреляции впервые исследовал Лорен Чепман (кстати, это однофамилец нашего знаменитого, хотя и провалившегося агента-нелегала Анны Чапман) еще в 1967 году. И именно этот исследователь ввел сам термин «иллюзорная корреляция».

Исследование проводилось так.

Испытуемым в течение определенного времени предъявлялись (проецировались на экран) пары слов, например, «бекон — яйца». Пары составлялись следующим образом: левым словом оказывалось одно из следующих четырех слов: бекон, лев, бутоны, лодка, а правым — одно из следующих трех слов: яйца, тигр, тетрадь.

Таким образом испытуемому предъявлялось 12 пар слов: «бекон — яйца», «бекон — тигр», «бекон — тетрадь» и т.д. Причем эти пары слов предъявлялись много раз и чередовались в случайном порядке, но каждая пара предъявлялась равное количество раз.

Затем испытуемых просили оценить частоту появления каждой пары слов. И это ключевой момент эксперимента.

Что же в итоге? … Читаем дальше?