Борцы за отмену смертной казни часто ссылаются на слишком высокую цену судебной ошибки. Даже в случае пересмотра приговора жизнь человеку уже не вернёшь. Diletant.media и Андрей Позняков решили ещё раз назвать имена некоторых из тех, кто был оправдан уже после казни.

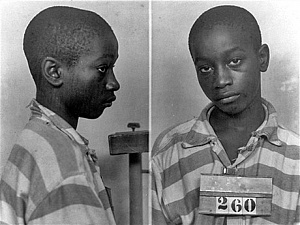

В этом печальном списке совершенно особое место занимает американский подросток Стинни Джордж. Он стал самым юным смертником XX века — на момент казни ему не исполнилось ещё 15 лет. Джорджа судили по делу об убийстве двух девочек — 8 и 11 лет в 1944 г. Преступление было совершено в городке Алколу в Южной Каролине. Он был разделён железной дорогой на две части — ту, где жили белые, и ту, где жили темнокожие. Стинни Джордж был из второй половины, куда погожим мартовским деньком решили съездить на велосипедах за цветами две девочки. Их тела впоследствии нашли в канаве, а Джордж, по версии следствия, оказался последним, с кем они общались. Разбирательство длилось всего три месяца, родители темнокожего подростка были вынуждены бежать из города, бросив сына. Скорым был и суд — ключевые показания дали полицейские, которые уверяли, что фигурант дела признался им в убийстве. Присяжные за десять минут совещания признали Джорджа виновным. 16 июня 1944 его казнили на электрическом стуле.

Спустя 70 лет выяснилось, что юный смертник перед казнью плакал

Вернулись к этому делу лишь в 2013: о невиновности Джорджа заявил его сокамерник. До этого предположения о судебной ошибке легли в основу романа Дэвида Стаута “Скелеты Каролины” и фильма “83 дня”. В 2014-м состоялся повторный судебный процесс. Стинни Джорджа оправдали — посмертно.

Почти 90 лет ушло на то, чтобы добиться реабилитации австралийца Колина Кэмпбелла Росса. Его повесили в 1922 г. по делу об изнасиловании и убийстве — жертвой преступника стала 12-летняя Альма Тиршке. Росс держал свой кабак. Главной уликой против него стала прядь светлых волос, которую обнаружили на одеяле на его кровати. Прокурор смог убедить суд, что эти волосы принадлежали именно жертве насильника. Росс до конца настаивал на своей невиновности. Несмотря на это его приговорили к казни и через четыре месяца повесили.

Уже в середине девяностых материалы дела оказались в распоряжении исследователя Кэвина Моргана. Он использовал современные методы для проверки данных о том, что волосы принадлежали убитой. Эта версия не подтвердилась. Результаты анализа легли в основу книги, которая обернулась скандалом. Потомки Росса и Тиршке потребовали пересмотра дела — генпрокурор штата Виктория признал обвинительное заключение ошибочным, а Верховный суд реабилитировал казнённого.

3

Китайское правосудие: дело Хууджилта

3 голоса

Грандиозным скандалом в КНР обернулось дело об изнасиловании и убийстве посетительницы общественного туалета в столице Внутренней Монголии Хух-Хото. Преступление было совершено в январе 1996 г., правоохранители оперативно задержали местного жителя по имени Хууджилт. Он дал признательные показания, был осуждён и казнён уже в июне.

Об этих событиях не вспоминали почти десять лет и так и не вспомнили бы, если бы не задержание серийного маньяка Чжао Чжихуна. Тот взял на себя ответственность за 10 изнасилований и убийств, в том числе за преступление, за которое казнили Хууджилта. Дело 1996 года вернули на новое рассмотрение. В декабре 2014 г. приговор отменили.

Суд признал серьёзные недочёты при рассмотрении дела Хууджилта

Родственникам казнённого по ошибке выплатили крупную по китайским меркам компенсацию: 30 тысяч юаней, почти 5 тысяч долларов. Следствие установило, что Хууджилт мог дать признательные показания под давлением, к ответственности привлекли почти три десятка чиновников. Скандал был настолько грандиозным, что стал ключевой темой ежегодного отчёта органов суда и прокуратуры на сессии Всекитайского собрания народных представителей и Народного политического консультативного совета Китая.

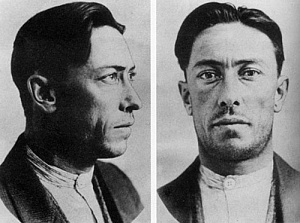

В камере смертников в 1876-м оказался ещё один подросток, британец Уильям Хэброн. 18-летний житель Лондона был задержан по обвинению в убийстве полицейского. Как и во многих других таких случаях, разбирательство было недолгим. Суд посчитал представленные доказательства достаточным для того, чтобы приговорить юношу к казни через повешение. Спасло его то, что по закону предать смерти можно было лишь начиная с 19-летнего возраста. Хэброну оставалось жить пару месяцев. За это время стали известны новые обстоятельства дела, которые позволили адвокатам обжаловать приговор: смертную казнь заменили на пожизненное заключение.

В качестве компенсации Хэброну выплатили 800 фунтов

В спустя ещё пару лет, в 1879 в убийстве полицейского сознался другой человек — рецидивист Чарльз Пис. Пройдя через два обвинительных приговора, камеру смертников и тюрьму для осуждённых на пожизненное заключение, Хэброн получил право выйти на свободу.

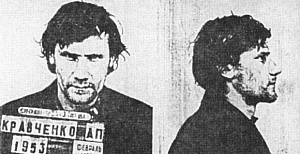

Самым известным российским смертником, чей приговор был впоследствии отменён, стал житель города Шахты Ростовской области Александр Кравченко. Он был задержан в декабре 1978 г. по подозрению в жестоком убийстве и изнасиловании 9-летней школьницы. Положение фигуранта дела осложнялось тем, что он уже отсидел срок за сексуальное насилие и убийство десятилетней девочки. У Кравченко было алиби, поэтому сначала отпустили, но спустя пару месяцев он опять оказался в руках милиции — по обвинению в краже. В ходе допросов он признал свою вину и взял на себя ответственность ещё и за нашумевшее убийство. 16 августа 1979 г. Ростовский областной суд приговорил Кравченко к смертной казни. Осуждённый подал жалобу, заявил, что оговорил себя под давлением, дело было направлено на пересмотр. Сначала наказание смягчили — до 15-летнего срока заключения.

Казни Кравченко добились родственники погибшей девочки

В марте 1982 г. дело было пересмотрено в третий раз, Кравченко снова приговорили к смерти и на следующий год расстреляли.

Впоследствии убийство 1978 г. оказалось в одном ряду с преступлениями серийного маньяка Андрея Чикатило, жертвами которого, по данным следствия, стали более 50 человек. В ходе разбирательства «ростовский потрошитель» неоднократно менял показания, но был осуждён по всем статьям и казнён. В 1991 году на основании одного из решений по делу Чикатило Кравченко был оправдан. Впрочем, вскоре невиновным в убийстве второклассницы признали и самого маньяка, так что вопрос о том, кто на самом деле совершил это преступление остаётся открытым.

Смертная казнь: в каких странах она остается допустимым наказанием

В настоящее время смертная казнь применяется в 22 странах, среди которых США, Япония, Белоруссия. Абсолютным лидером по числу приведенных в исполнение приговоров является Китай – это при том, что полнотой информации по этой стране никто не обладает и часто казни оказываются засекречены. Нет данных и о Северной Корее. Подавляющее большинство стран, применяющих высшую меру наказания, находятся в Азии и Африке.

Еще в 34 странах мира смертный приговор выносится, но не исполняется – чаще всего его заменяют на пожизненное заключение. Среди них – Южная Корея, Мальдивы, Таиланд и Тунис.

В современной России в настоящее время смертная казнь не применяется с 1996 года. Всего за период с 1992 по 1999 год были приговорены к высшей мере наказания (расстрелу) около 1000 человек. Из них казнили лишь 79 человек, остальных в большинстве своем помиловали. Последний раз приговор приведен в исполнение в 1996 году, когда казнили маньяка Сергея Головкина, убившего как минимум 11 несовершеннолетних. Затем президент просто перестал рассматривать подобные дела и принимать по ним решения.

В 1999 году Конституционный суд наложил мораторий на применение высшей меры наказания в связи с вхождением нашей страны в Совет Европы. Однако 16 марта 2022 года Россию исключили из этой международной организации в связи с событиями на Украине.

Отметим, что в статье 59 Уголовного кодекса Российской Федерации все еще содержится упоминание смертной казни, однако на практике считается, что ее применение невозможно и для этого пришлось бы вносить поправки в Конституцию.

Расстреляли вместо Чикатило, но кто убийца, до сих пор не ясно

Примером самой громкой судебной ошибки принято считать дело маньяка Чикатило: спустя 30 лет все еще в ходу миф, что, пока его ловили, «расстреляли много невиновных». На самом деле высшую меру наказания получил лишь один человек, и его участие в преступлении, как, впрочем, и участие в нем самого Чикатило, до сих пор остается под вопросом.

Речь идет об убийстве девятилетней Лены Закотновой, которое произошло в городе Шахты в 1978 году. Труп девочки со следами сексуального насилия обнаружили рядом с мостом через речку Грушевку, у нее были завязаны глаза, на теле имелись ножевые раны. Смерть, согласно выводам экспертов, наступила в результате удушения.

В процессе расследования в область интересов правоохранительных органов впервые попал Чикатило: купленный им домик-мазанка находился недалеко от места преступления, свидетели показали, что в день убийства там горел свет, хотя проживал Чикатило с семьей по другому адресу.

Нашлась также свидетельница, утверждавшая, что видела девочку с мужчиной, чье словесное описание напоминало Чикатило. Однако его допросили и отпустили, а в качестве обвиняемого задержали ранее судимого за аналогичное преступление Александра Кравченко.

В возрасте 17 лет Кравченко, находясь в состоянии алкогольного опьянения, изнасиловал и убил 10-летнюю девочку. За это преступление он получил 10 лет, избежав смертной казни лишь в силу юного возраста. Отсидев шесть лет, освободился и вел жизнь примерного члена общества: работал в Шахтах штукатуром, женился на женщине с ребенком и на момент ареста ждал появления общего наследника.

Кравченко задержали потому, что его дом был еще ближе к месту обнаружения тела Лены Закотновой, чем дом Чикатило, и допрашивали, зная о его биографии. Однако жена Александра и ее подруга, независимо друг от друга, показали, что в день преступления Кравченко пришел домой рано, был трезвым и до утра никуда не выходил. Мужчину отпустили.

Через несколько дней он вновь оказался под арестом, на этот раз – якобы за кражу постельного белья у соседки. При этом часть украденного была растеряна по дороге и, как в сказке, вела от места преступления к дому Кравченко. Почему произошла кража, теперь сказать трудно. Сотрудники правоохранительных органов говорили, что Кравченко совершил ее намеренно, чтобы сесть за мелкое преступление, а не за убийство. Есть также версия, что украденное белье Александру подкинули сами правоохранители, чтобы иметь основания для нового ареста.

Дальнейшее – описание мер воздействия на Кравченко и его семью, которые позднее были доказаны. Александра избивали в камере посаженные туда уголовники, его супругу и ее подругу задерживали и давили, обвиняя в даче ложных показаний, и вскоре женщины отказались от своих слов, сломав подсудимому алиби. Сам Кравченко в процессе следствия несколько раз менял показания, путался в них. Позднее он объяснил, что оговорил себя под давлением, а детали преступления, совершенного над Леной Закотновой, узнал из материалов дела и экспертиз, предоставленных ему следователем. Он путал возраст погибшей, описание ее одежды, не мог сказать, где взял нож и где оставил его.

Дело Кравченко посылали на доследование и даже успели отменить ему смертный приговор, однако включилась бабушка Лены Закотновой, которая стала писать жалобы с требованием справедливости, и в итоге добилась нового пересмотра дела и высшей меры наказания.

Так Александр Кравченко, отбывавший в тот момент наказание за кражу (это обвинение не было с него снято) в итоге был расстрелян. Произошло это в 1983 году, спустя почти пять лет после убийства.

В своем последнем ходатайстве о помиловании Александр Кравченко писал: «Наступит день и час, и вам будет стыдно за то, что вы губите меня, невинного человека, оставляя моего ребенка без отца».

Об убийстве Лены Закотновой все успели забыть, пока оно не всплыло в показаниях арестованного в 1990 году Андрея Чикатило. Он сам признался в этом преступлении, сообщив, что оно стало первым в совершенной им серии. Но и тут стоит обратить внимание на некоторые нестыковки. Например, в своих показаниях Чикатило не упоминает удары ножом, говоря, что просто задушил девочку, а также опускает факт, что завязал ей глаза, хотя это стало яркой и запоминающейся деталью, а позднее – и характерным почерком маньяка.

Менялось и место совершения преступления: сначала Чикатило завил, что убил девочку на пустыре у реки, затем – в собственном доме, той самой мазанке. Не совпали и данные экспертизы по выделениям преступника, найденным на теле жертвы.

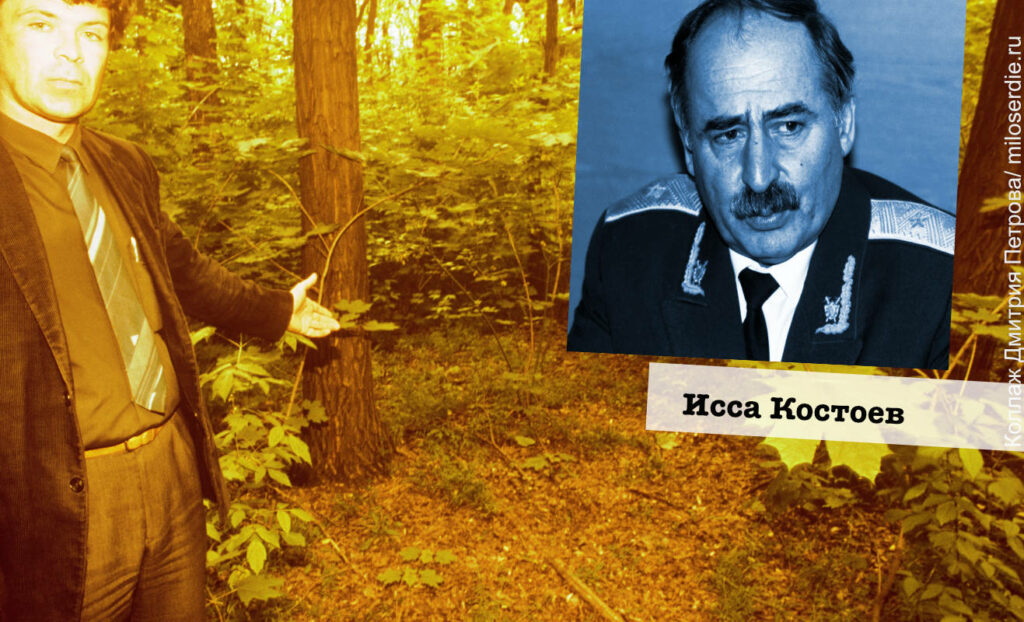

Несмотря на усилия следователя Иссы Костоева, который вел дело Чикатило, обвинения по этому эпизоду были в финальном приговоре сняты. Считается, что Андрей Чикатило, будучи натурой впечатлительной, «присвоил» себе это преступление, чтобы казаться эффектнее и значительнее.

Однако Исса Костоев сумел добиться пересмотра дела Александра Кравченко и реабилитировать его посмертно. Согласно воспоминаниям следователя, это было почти беспрецедентное событие в позднем СССР – он несколько раз направлял протесты и жалобы в Верховный суд, получая отказы. Никто не хотел признавать ошибки, поскольку ответить за них пришлось бы людям, которые ошибочно вынесли Александру смертный приговор, сделать это удалось лишь с четвертого раза.

О том, что Александр Кравченко реабилитирован, правоохранительные органы смогли сообщить его матери одновременно с информацией о том, что он был расстрелян. Женщина до последнего ждала возвращения сына и надеялась.

Сколько ежегодно казнят в мире и часто ли ошибаются

Наиболее полной статистикой обладает международная организация Amnesty Inteational (*сайт организации в России заблокирован Роскомнадзором). По данным за 2020 год, высшая мера наказания применялась как минимум 483 раза, что на 26% меньше показателя 2019 года и на 70% меньше пиковых значений 2015 года, когда были проведены 1634 казни. Наибольшее число смертных приговоров привели в исполнение в Китае, Иране и Египте.

Такое падение, впрочем, вероятнее всего, связано с локдауном и разнообразными ковидными ограничениями. В 2021 году число смертных приговоров, приведенных в исполнение, увеличилось. Amnesty Inteational зафиксировала 579 казней, лидером по-прежнему оставался Китай.

Что касается процента судебных ошибок, судить о нем можно, хоть и косвенно, на примере США, где наиболее развита практика анализа и пересмотра уже закрытых судебных дел. Так, в 2013 году появилась публикация с результатами масштабного исследования ФБР, которое касалось приговоров, вынесенных в период с 1979 по 2009 годы. Все приговоры опирались в том числе на анализ волос, найденных на месте преступления. Было свершено 120 ошибок, 27 человек получили высшую меру наказания, многие – пожизненное заключение. И лишь когда процедура анализа ДНК стала доступной, а технология получила развитие, стало ясно, что «говорящие улики» стали причиной чудовищных ошибок, некоторые из которых уже невозможно исправить.

К слову, в настоящее время и сама процедура анализа ДНК в Америке также подвергается критике. Первоначально на этот метод возлагали огромные надежды, считая его универсальным доказательством, однако затем стало понято, что и здесь высока вероятность ошибки. Например, в местных СМИ широко разошелся случай, когда в убийстве богатого человека был обвинен бездомный на том основании, что под ногтями у погибшего нашли ДНК «убийцы». Позднее при разбирательстве выяснилось, что одна и та же медицинская бригада сначала выезжала на вызов к бездомному, а затем оказалась на месте преступления, чтобы констатировать смерть, и перенесла генетический материал через обычные латексные перчатки.

13 человек посадили и одного казнили, пока искали витебского душителя Михасевича

Серийный убийца Геннадий Михасевич, орудовавший в 70-х – начале 80-х годов ХХ века и совершивший, согласно приговору суда, 36 убийств, еще и рекордсмен по числу невинно осужденных: пока искали настоящего преступника, успели перемолоть судьбы 14 человек, из которых один был расстрелян, один ослеп в тюрьме, а остальные отсидели полностью внушительные сроки, вплоть до 15 лет.

Причина простая: следователи торопились раскрыть резонансные преступления с одной стороны, а с другой – не желали признавать наличие в СССР маньяков, которые казались приметой исключительно «загнивающего Запада».

Свое первое убийство Михасевич совершил в 1971 году на территории Витебского района Белорусской СССР и затем продолжал совершать их с завидной регулярностью в течение 14 лет, пока не был пойман.

В 1979 году за одно из подобных преступлений были осуждены сожители Николай Тереня и Людмила Кадушкина. Тереня вел жизнь асоциального элемента, не работал и не имел постоянного места жительства. Ранее он был неоднократно судим за мелкие преступления. Его подруга Людмила Кадушкина также не отличалась примерным поведением. Оба попались на краже, но затем следователи стали раскручивать их на предмет причастности к убийству.

Поскольку в то время милиционеры были заинтересованы в статистике раскрываемости преступлений, они ничем не гнушались. Другому подозреваемому по делу Михасевича, например, специально подбросили при обыске фото жертвы. Сразу троих мужчин невинно осудили лишь потому, что они случайно гуляли с собаками недалеко от места преступления.

А в случае Николая Терени правоохранители стали давить на его сожительницу, убеждая женщину дать показания против него: мол, так она сама избежит расстрела и пойдет по делу как соучастница. Кадушкина испугалась и подписала все, что от нее требовалось. Обвинительный приговор строился именно на показаниях Людмилы, сам Тереня все отрицал, но это в конечном итоге не спасло его от расстрела. Приговор привели в исполнение в 1980-м.

При этом сам Геннадий Михасевич пристально следил за расследованием совершенных им преступлений, по некоторым делам в качестве зрителя даже присутствовал в суде, изучал публикации в прессе. Тот факт, что раз за разом арестовывали невиновных, его только воодушевлял.

В какой-то момент убийца стал ловить сам себя, как участник народных дружин. Так он получил доступ к информации, имел возможность затаиться, когда милиция выходила на облавы или выставляла в качестве приманки своих сотрудниц в штатском.

Всех, кто был несправедливо осужден, реабилитировали только после приговора Михасевичу, вынесенному в 1987 году. Многие получили от государства значительные денежные компенсации и квартиры, но вернуться к полноценной жизни эти люди не смогли, тюрьма подорвала физическое и психическое здоровье.

По делу о злоупотреблениях в процессе расследования были привлечены к ответственности около 200 сотрудников правоохранительных органов. Кто-то получил выговоры, других понизили в должности, несколько человек осудили условно. Лишь один, зональный прокурор транспортной прокуратуры Белорусской ССР Валерий Сороко, получил реальный срок: четыре года лишения свободы.

Как в Великобритании отменили смертную казнь: причиной стал приговор честному отцу семейства

У каждой из стран, отменивших высшую меру наказания, были свои причины – в основном это происходило под давлением общественности, либо ради вступления в крупные международные организации. Показательна в этом смысле история Великобритании: считается, что здесь на отмену смертной казни повлияли два громких кейса, о которых в стране помнят до сих пор.

Первым моментом, который заставил общество и власти задуматься, стало дело Эдит Томпсон: в 1920-х годах женщину обвиняли в том, что она подстрекала любовника убить собственного мужа. Преступление совершилось, правоохранители арестовали и самого убийцу – Фредерика Байуотерса, и Эдит. Уликой против нее служили только личные письма, в которых она фантазировала о том, как хорошо бы ей жилось без супруга. Несмотря на то что мистер Байуотерс настаивал на своей единоличной вине, Эдит приговорили к смертной казни, хотя казнь молодой женщины уже казалось британцам настоящей дикостью. В пользу Эдит подписывали петиции, ее поддерживали в СМИ. Последние дни своей жизни миссис Томпсон провела в состоянии, близком к истерии. Она плакала, кричала, стонала и ничего не ела. Сама процедура повешения была настолько ужасной, а жертва так отчаянно сопротивлялась, что палач, совершавший казнь, затем предпринял две попытки самоубийства, вторая из которых увенчалась успехом.

Дело Тимоти Эванса гремело в конце 40-х – начале 50-х годов прошлого века. Беременная жена Эванса и его маленькая дочь были убиты, и полиция обвинила в их смерти отца семейства. В ходе расследования Эванс назвал имя человека, которого подозревал, но это не помогло: мужчину повесили; а спустя три года после того, как невиновный был повешен, открылось, что преступление действительно совершил тот, на кого указал Тимоти Эванс – их с женой сосед по дому Джон Кристи, который оказался серийным убийцей.

Высшая мера наказания была отменена в Великобритании в 1965 году.

Казнили умственно отсталого человека и поймали «банду олигофренов», пока искали свердловского убийцу Фефилова

Так же, как и в предыдущих случаях, случайной жертвой милицейского произвола стал в 1984 году житель Свердловской области Георгий Хабаров. Мужчина имел психиатрический диагноз (умственная отсталость), был ранее судим за кражу. В круг интересов правоохранительных органов он попал как подозреваемый в изнасиловании и убийстве пятиклассницы Лены Мангушевой. В реальности преступление совершил серийный маньяк Николай Фефилов, на счету которого за период с 1982 по 1988 год было семь аналогичных преступлений.

Работая по убийствам Фефилова, правоохранительные органы долго не могли признать, что имеют дело с серией: не смущал следователей даже тот факт, что у убийцы был характерный почерк и все нападения совершались в районе автобусной остановки «Контрольная», там же находили тела жертв. Поэтому по каждому из преступлений последовательно задерживали разных людей.

Остановить судебную машину не могли даже такие крайне сомнительные обстоятельства: пока очередной «убийца» уже находился в заключении, изнасилования и убийства не прекращались и происходили с завидной регулярностью.

Георгий Хабаров был задержан через несколько дней после убийства Лены Мангушевой. На него обратили внимание, потому что ранее на него поступило заявление от жительницы Свердловска о том, что он пытался ее изнасиловать. Речь при этом шла о взрослой женщине, а погибла младшая школьница, но это милицию не смутило. Хабарова задержали и начали допрашивать с пристрастием, убеждая подписать признание.

На первом следственном эксперименте Георгий путался: говорил, что зарезал свою жертву, тогда как она была задушена, не мог описать ее внешность и одежду, не находил ответа на вопрос, куда делся портфель школьницы (позднее выяснилось, что настоящий убийца унес его с собой и даже подарил родной дочери).

Пришлось подгонять показания Хабарова под выводы экспертов, проводить повторный следственный эксперимент. Данные экспертизы биологических жидкостей, найденных на теле жертвы, также не соответствовали анализам задержанного, но это милицию не остановило.

Засомневался лишь судья, который, читая материалы дела, обратил внимание и на уровень умственного развития Хадарова (в 28 лет он все еще учился в коррекционной школе), и на постоянные смены показаний обвиняемого и его заявления, что он себя оговорил. Боясь совершить фатальную ошибку, судья приговорил Георгия Хабарова к 14 годам заключения вместо расстрела. Однако после приговора родственники жертвы подали апелляцию и добились высшей меры наказания.

В деле маньяка Фефилова было еще несколько пострадавших. Один из них, Михаил Титов, погиб в тюрьме от побоев сокамерников. Настоящая вина его состояла лишь в том, что он был безответно влюблен в одну из жертв и докучал ей своим вниманием. До признания его также довели следователи.

Еще троих подозреваемых, двое из которых имели диагноз «умственная отсталость», убедили взять на себя сразу четыре убийства в районе станции «Контрольная». Избежать расстрела удалось чудом – вскоре Николая Фефилова задержали на месте преступления, и он признался в совершении семи убийств. Георгий Хабаров был реабилитирован посмертно, остальные подозреваемые – отпущены на свободу. Ответственности за сфабрикованные уголовные дела никто не понес – виновными назначили сотрудников, которые принимали участие в расследовании, но к тому моменту уже умерли.

Сегодня в обществе все чаще поднимается дискуссия о возвращении смертной казни. К сожалению, судебная практика знает множество примеров смертной казни по ошибке, когда высшая приводила к смерти невиновного человека. О шести таких мы расскажем в этом материале.

Казнь Махмуда Хусейна Маттана

В 1952 году в окрестностях доков Кардиффа (Великобритания) была убита 42-летняя сотрудница ломбарда Лили Вольперт. Кто-то перерезал женщине горло и похитил все деньги из кассы (около 100 фунтов, в переводе на современные суммы – около 250 тысяч рублей).

29-летнего сомалийца Махмуда Хусейна Маттана задержали «по горячим следам» как главного подозреваемого, а спустя 9 дней его объявили виновным в убийстве. Основанием для обвинений стали показания свидетелей, описавших мужчину «сомалийской внешности». Мигрант Махмуд провинился только в том, что был выходцем из Сомали.

Махмуд Хусейн Маттан

При обыске, свидетелями которого стали его жена Лора и дети подозреваемого, нашли туфли с пятнами крови и сломанную бритву. Находки приобщили к делу как улики, вот только туфли, как выяснилось позже, мужчина купил подержанными, а кровь на них принадлежала животному.

Махмуд почти не говорил по-английски, но суд проходил без переводчика. Никаких более конкретных доказательств вины задержанного предоставлено не было, но общественность требовала найти виновного. 24 июня Хусейну Маттану вынесли смертный приговор, через 6 месяцев привели его в исполнение. Его жена не знала о дате казни. 3 сентября она пришла на свидание с мужем, чтобы узнать, что его больше нет в живых.

Лишь в 1998 году дело пересмотрели, жена и дети Маттана получили компенсацию (725 тысяч фунтов), а материалы дела отправили на повторную проверку. К слову, убийство Вольперт до сих пор не раскрыто.

46 лет спустя жена Махмуда (на фото) получила компенсацию

Суд над Джорджем Стинни

Подросток по имени Джордж Стинни — самый юный смертник XX века, казненный в 14-летнем возрасте. В 1944 году Стинни, чернокожий жить американского Юга, был обвинен в убийстве двух белых девочек 8 и 11 лет.

Джордж Стинни

Девочки на велосипедах приехали в район, где жили преимущественно афроамериканцы, чтобы нарвать полевых цветов, и были забиты насмерть. Многие видели, что незадолго до убийства девочки разговаривали со Стинни. Однако непосредственно на момент убийства у него было алиби – он играл с сестрой.

Бетти Бинникер и Мэри Темз были убиты тупым ударом по голове

Расследование дело длилось три месяца, суд продолжался менее трех часов, а присяжные (среди них не было ни одного чернокожего) вынесли вердикт за 10 минут. Подростка признали виновным и приговорили к казни на электрическом стуле. Стул оказался слишком высоким для Стинни – чтобы голова мальчика дотянулась до проводов, под него подложили Библию, которую с тюрьме выдавали всем смертникам.

Стинни остается самым молодым смертником в истории США

Дело подростка пересмотрели только в 2013 году, когда бывший сокамерник Стинни вспомнил, как мальчик признавался ему, что не совершал убийства. Повторного разбирательства не проводилось — в 2014 году судья Кармен Маллен отменила приговор, сославшись на допущенные процессуальные нарушения.

Фиктивный Чикатило

Александр Кравченко — российский смертник, казненный по ошибке. В 1978 году Кравченко задержали по подозрению в убийстве 9-летней школьницы Елены Закотновой. Положение Кравченко усугублялось тем, что ранее он уже отбывал срок за сексуальное насилие и убийство 10-летней девочки. Но так как злодеяние он совершил еще несовершеннолетним, суд приговорил его не к высшей мере, а к 10 годам, из которых он отсидел всего 6.

Лена Закотнова

На момент задержания Александр предоставил алиби – после конца рабочего дня он заглянул к товарищу, а потом вернулся домой и уже никуда не уходил до утра. Его слова подтвердили жена и ее подруга. Через несколько месяцев Кравченко совершил кражу, был пойман и признал, что ограбил соседа. Следователи решили вновь проверить Кравченко на причастность к убийству Лены – раз уж он оказался у них в руках.

Жену Кравченко уличили в помощи Кравченко при грабеже, надавили на нее и заставили отказаться от первоначальных показаний о том, где Александр был в вечер убийства. Сам Кравченко несколько раз писал признания в убийстве, то отзывал их, ссылаясь на то, что составил их под давлением.

Александр Кравченко

В августе 1979 года Кравченко приговорили к смертной казни. Адвокат подал на апелляцию, приговор был отменен, Александра приговорили к пяти годам тюрьмы за кражу. К 1982 году родственники Лены всё же добились казни Кравченко. В своем последнем прошении Кравченко писал:

Наступит день и час, и вам будет стыдно за то, что вы губите меня, невиновного человека, оставляя моего ребенка без отца.

В 1992 году вину за убийство школьницы среди прочих убийств взял на себя Андрей Чикатило. Однако к моменту казни в его словах нашли несостыковки, а позже и сам он отказался от этих показаний.

Кравченко был реабилитирован посмертно. Убийство Закотновой так и осталось нераскрытым. Возможным убийцей также называют Анатолия Григорьева – будучи пьяным, мужчина бахвалился перед друзьями тем, что убил девочку, «о которой писали в газетах», а вскоре покончил с собой.

Георгий Хабаров

Случай Георгия Хабарова во многом похож на эпизод с Кравченко. В апреле 1982 года кто-то задушил 11-летнюю Лену Мангушеву, жительницу Свердловска. Под подозрение пал местный житель Георгий Хабаров. Мужчина, к слову, уже отсидевший срок за грабеж, был умственно отсталым, по уровню интеллекта его можно было назвать сверстником Лены.

Лена Мангушева

Следователи воспользовались состоянием Хабарова и убедили его, что он – убийца. Суд не смутило, что весь день он был дома с мамой, подтвердившей его слова, не мог назвать место совершения преступления и место, где он спрятал портфель школьницы. Георгия приговорили к 14 годам тюрьмы, но мама Лены через Верховный суд добилась высшей меры. В апреле 1984 года Хабарова расстреляли.

Георгий Хабаров

В 1988 году настоящий убийца девочки, Николай Фефилов, был пойман прямо над телом своей очередной жертвы. Фефилов не дожил до суда – его убил сокамерник.

Николай Фефилов

Китайское правосудие Хууджилта

В январе 1996 года был арестован житель Внутренней Монголии 18-летний Хууджилт, обвиненный в убийстве женщины. Юноша дал признательные показания, и уже в июле был казнен.

Китаец Хууджилт был казнен по ошибке

Спустя 10 лет разразился громкий скандал в связи с задержанием серийного убийцы Чжао Чжихуна. Маньяк признался в 10 убийствах, в том числе и в преступлении, якобы совершенном Хууджилтом. Полученные показания спровоцировали настоящую истерику — дело вернули на пересмотр, несколько десятков чиновников потеряли должности. В итоге в 2014 году Хууджилта признали невиновным.

Реабилитация Колина Росса

Австралийца Колина Кэмпбэлла Росса повесили в 1922 по обвинению в убийстве 12-летней Альмы Тиршке. Основной уликой против Колина стал светлый локон, обнаруженный в его комнате. Прокурор убедил суд, что найденная прядь принадлежала жертве — на этом основании Росса приговорили к казни и повесили четыре месяца спустя.

Колин Кэмпбэлл Росс

В 1993 году исследователь Кэвин Морган обнаружил в архивных документах остатки волос, якобы принадлежавших жертве. Ему удалось добиться проведения ДНК-экспертизы, которая установила — волосы, найденные в комнате Росса, не принадлежат Альме Тиршке. В 2008 году Росса оправдали и реабилитировали посмертно.

«Ошибочную» смертную казнь исправить уже нельзя — вернуть человека с того света еще никому не удавалось. Возможно, если бы суд не принимал таких скоропалительных решений, ни в чем невиновный человек остался бы жив. Недаром говорят: семь раз отмерь, один — отрежь. Особенно если это касается жизни другого.10 октября 2003 года был учрежден Всемирный день борьбы со смертной казнью.

Правосудие не всегда торжествует и мир полон несправедливости порой — некоторых людей казнят по ошибке.

1 130 республиканцев

После самого опасного покушения на жизнь первого консула Наполеона Бонапарта 24 декабря 1800 года в Париже 130 левых республиканцев были сосланы на каторгу в Гвинею. И хотя это было дело рук Жозефа Пьера, Пико де Лимоэлана и Робино де Сен-Режана, сторонников Бурбонов, и их отправили на гильотину, Наполеон отказался помиловать ложно обвиненных якобинцев.

2 Уильям Хэброн

18-летний житель Лондона Уильям Хэброн, приговоренный в 1876 году к смертной казни через повешение за убийство полицейского, ждал казни 2 месяца в вижу того, что несовершеннолетних нельзя было казнить (в то время этим порогом считалось 19-летие). За это время вскрылись дополнительные обстоятельства, адвокаты подали аппеляцию на приговор, и Уильяму заменили смертную казнь пожизненным заключением.

3 и 4. Никола Сакко и Бартоломео Ванцетти

Никола Сакко и Бартоломео Ванцетти стали самыми известными в СССР и России ошибочно казненными .

О них стало известно после того, как в 1920 году в США им было предъявлено обвинение в убийстве кассира и двух охранников обувной фабрики в г. Саут-Брейнтри.

Несмотря на противоречивые показания свидетелей преступления, неуверенность экспертов и выступления свидетелей, подтверждавших алиби обвиняемых, решающую роль сыграло субъективные факторы — они просто не понравились прокурору и судье.

5 Колин Кэмпбелл Росс

27 мая 2008 года генеральный прокурор штата Виктория в Австралии Роб Халлс объявил, что Верховный суд штата признал ошибочным обвинительное заключение по делу Колина Кэмпбелла Росс, владельца кабака, который был повешен в 1922 году в возрасте 28 лет. Правда, прокурор подчеркнул, что речь идет только об амнистии казненного, поэтому о невиновности Росса речь не идет, хотя Верховный суд признал, что его повесили зря.

6 Вилли Джаспера Дарден

15 марта 1988 г. в штате Флорида казнили Вилли Джаспера Дардена, несмотря на убедительные доказательства его алиби, полученные от двух независимых свидетелей. Международные протесты, в том числе от папы римского, Андрея Сахарова, преподобного Джесси Джексона, не смогли убедить губернатора Мартинеса помиловать осужденного.

7 Вильгельм-Людвиг Шмид

Особенно много казней по ошибке совершается диктаторскими режимами. Когда Гитлер приказал провести операцию по уничтожению руководства штурмовых отрядов, в списки подлежавших уничтожению попал мюнхенский врач Людвиг Шмитт, сотрудничавший с Отто Штрассером, братом Грегора, второго человека в НСДАП до 1933 г., организатора «Черного фронта». В погоне за врачом отряд палачей натолкнулся на человека с похожей фамилией — музыкального критика Вильгельма-Людвига Шмида. Жил он совсем в другом месте, фамилия также была другая (Шмид, а не Шмитт), но все это впопыхах ускользнуло от внимания убийц. Они схватили музыкального критика и отправили в концлагерь Дахау, где и убили. Тело убитого послали родственникам, но строжайше повелели гроб с покойником не вскрывать.

8 Трой Дэвис

В 2011 году в США был казнен путем введения смертельной инъекции Трой Дэвис, обвиняемый в убийстве полицейского. Осужденный Трой Дэвис не признался в совершении преступления даже в последние минуты своей жизни. Он обратился к присутствующим родственникам погибшего полицейского, уверяя их, что убийство совершил не он, а вся эта история – результат судебной ошибки.

Прямых доказательств причастности Дэвиса не было, только показания свидетелей, которые позже сознались, что подписали бумаги под давлением со стороны следствия.

9 Н.С.Баранов

В книге «Красный террор» упоминается случай, как в Одессе был расстрелян товарищ прокурора Н.С.Баранов вместо офицера с таким же именем.

10 А. Кравченко

Александра Кравченко обвинили в убийстве, которое совершил Андрей Чикатило в 1978 году. Главным фактом повлиявшим на судьбу Кравченко стало изнасилование и убийство девушки, за которое он отсидел 10 лет. Суд признал его виновным и в «новом деле» 1983 году приговор привели в исполнение. После ареста и признания Чикатило, стало известно об этой ужасной ошибке.

Как выяснилось, когда Кравченко держали в заключении, к нему подсадили здоровенных уголовников, которые жестоко избивали Кравченко и вынудили его сделать «чистосердечное признание»

В прошении о помиловании он написал: «НАСТУПИТ ДЕНЬ И ЧАС, И ВАМ БУДЕТ СТЫДНО ЗА ТО, ЧТО ВЫ ГУБИТЕ МЕНЯ, НЕВИННОГО ЧЕЛОВЕКА, ОСТАВЛЯЯ МОЕГО РЕБЕНКА БЕЗ ОТЦА»

«False execution» redirects here. For the situation where a person falsely believes they will be executed, see Mock execution.

Wrongful execution is a miscarriage of justice occurring when an innocent person is put to death by capital punishment. Cases of wrongful execution are cited as an argument by opponents of capital punishment, while proponents say that the argument of innocence concerns the credibility of the justice system as a whole and does not solely undermine the use of the death penalty.[1]

A variety of individuals are claimed to have been innocent victims of the death penalty.[2][3] Newly available DNA evidence has allowed the exoneration and release of more than 20 death-row inmates since 1992 in the United States,[4] but DNA evidence is available in only a fraction of capital cases. At least 190 people who were sentenced to death in the United States have been exonerated and released since 1973, with official misconduct and perjury/false accusation the leading causes of their wrongful convictions.[5] The Death Penalty Information Center (U.S.) has published a partial listing of wrongful executions that, as of the end of 2020, identified 20 death-row prisoners who were «executed but possibly innocent».[6]

Judicial murder is a type of wrongful execution.[7]

Specific examples[edit]

Australia[edit]

Colin Campbell Ross was hanged in Melbourne in 1922 for the murder of 12-year-old Alma Tirtschke the previous year in what became known as the Gun Alley Murder. The case was re-examined in the 1990s using modern techniques and Ross was eventually pardoned in 2008, by which time capital punishment in Australia had been abolished in all jurisdictions.

Ronald Ryan was the last person executed in Australia. His execution took place on 3 February 1967. He and a fellow inmate, Peter John Walker, attempted to escape from Pentridge Prison on 19 December 1965, when prison guard George Hodgson was shot and killed. Multiple witnesses swore that they saw Ryan fire the shot that killed Hodgson, so he was found guilty. The true identity of the shooter is in contention as two other guards admitted to firing several shots, and in 2007, Peter John Walker said that it would have been impossible for Ryan to have shot the guard as his rifle had jammed.[8]

People’s Republic of China[edit]

Wei Qing’an (Chinese: 魏清安, born 1961) was a Chinese citizen who was executed for the rape of Kun Liu, a woman who had disappeared. The execution was carried out on 3 May 1984 by the Intermediate People’s Court. In the next month, Tian Yuxiu (田玉修) was arrested and admitted that he had committed the rape. Three years later, Wei was officially declared innocent.[9]

Teng Xingshan (Chinese: 滕兴善) was a Chinese citizen who was executed for supposedly having raped, robbed and murdered Shi Xiaorong (石小荣), a woman who had disappeared. An old man found a dismembered body, and incompetent police forensics claimed to have matched the body to the photo of the missing Shi Xiaorong. The execution was carried out on 28 January 1989 by the Huaihua Intermediate People’s Court. In 1993, the previously missing woman returned to the village, saying she had been kidnapped and taken to Shandong. The absolute innocence of the wrongfully executed Teng was not admitted until 2005.[10]

Nie Shubin (Chinese: 聂树斌, born 1974) was a Chinese citizen who was executed for the rape and murder of Kang Juhua (康菊花), a woman in her thirties. The execution was carried out on 27 April 1995 by the Shijiazhuang Intermediate People’s Court. In 2005, ten years after the execution, Wang Shujin (王书金; Wáng Shūjīn) admitted to the police that he had committed the murder.[11][12]

Qoγsiletu or Huugjilt (Mongolian: Qoγsiletu, Chinese: 呼格吉勒图, born 1977) was an Inner Mongolian who was executed for the rape and murder of a young girl on 10 June 1996. On 5 December 2006, ten years after the execution, Zhao Zhihong (Chinese: 赵志红) wrote the Petition of my Death Penalty admitting he had committed the crime. Huugjilt was posthumously exonerated and Zhao Zhihong was sentenced to death in 2015.[13]

Ireland[edit]

Sir Edward Crosbie, 5th Baronet was wrongfully executed in Carlow in 1798. Accused of being a United Irishman, his innocence was later proved.

Harry Gleeson was executed in Ireland in April 1941 for the murder of Moll McCarthy in County Tipperary in November 1940. The Gardaí withheld crucial evidence and fabricated other evidence against Gleeson. In 2015, he was posthumously pardoned.[14][15]

Taiwan[edit]

Chiang Kuo-ching (Chiang is the family name; Chinese: 江國慶, born 1975) was a Republic of China Air Force soldier who was executed by a military tribunal on 13 August 1997 for the rape and murder of a five-year-old girl. On 28 January 2011, over 13 years after the execution, Hsu Jung-chou (許榮洲), who had a history of sexual abuse, admitted to the prosecutor that he had been responsible for the crime. In September 2011 Chiang was posthumously acquitted by a military court who found Chiang’s original confession had been obtained by torture. Ma Ying-jeou, the Republic of China’s president, apologised to Chiang’s family.[16]

UK[edit]

- In 1660, in a variety of events known as the Campden Wonder, an Englishman named William Harrison disappeared after going on a walk, near the village of Charingworth, in Gloucestershire. Some of his clothing was found slashed and bloody on the side of a local road. Investigators interrogated Harrison’s servant, John Perry, who eventually confessed that his mother and his brother had killed Harrison for money. Perry, his mother, and his brother were hanged. Two years later, Harrison reappeared, telling the incredibly unlikely tale that he had been abducted by three horsemen and sold into slavery in the Ottoman Empire. Though his tale was implausible, he indubitably had not been murdered by the Perry family.

- Timothy Evans was tried and executed in March 1950 for the murder of his wife and infant daughter. An official inquiry conducted 16 years later determined that it was Evans’ fellow tenant, serial killer John Reginald Halliday Christie, who was responsible for the murders. Christie also admitted to the murder of Evans’ wife, following conviction for murdering five other women and his own wife. Christie, who was himself executed in 1953, may have murdered other women, judging by evidence found in his possession at the time of his arrest, but it was never pursued by the police. Evans was posthumously pardoned in 1966 after the inquiry concluded that Christie had also murdered Evans’ daughter. The case was a major factor leading to the abolition of capital punishment in the United Kingdom.

- George Kelly was executed in March 1950 for the 1949 murder of the manager of the Cameo Cinema in Liverpool, UK and his assistant during a robbery that went wrong. This case became known as the Cameo Murder. Kelly’s conviction was overturned in 2003. Another man, Donald Johnson, had confessed to the crime but the police bungled Johnson’s case and had not divulged his confession at Kelly’s trial.[17]

- Somali-born Mahmood Hussein Mattan was executed in 1952 for the murder of Lily Volpert. In 1998 the Court of Appeal decided that the original case was, in the words of Lord Justice Rose, «demonstrably flawed». The family were awarded £725,000 compensation, to be shared equally among Mattan’s wife and three children. The compensation was the first award to a family for a person wrongfully hanged.

- Derek Bentley was a learning disabled young man who was executed in 1953. He was convicted of the murder of a police officer during an attempted robbery, despite the facts that it was his accomplice who fired the gun and that Bentley was already under arrest at the time of the shooting. Christopher Craig, the 16-year-old who actually fired the fatal shot, could not be executed as he was under 18. Craig served only ten years in prison before he was released.[18]

United States[edit]

University of Michigan law professor Samuel Gross led a team of experts in the law and in statistics that estimated the likely number of unjust convictions. The study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences determined that at least 4% of people on death penalty/death row were and are likely innocent.[19][20]

Statistics likely understate the actual problem of wrongful convictions because once an execution has occurred there is often insufficient motivation and finance to keep a case open, and it becomes unlikely at that point that the miscarriage of justice will ever be exposed. For example, in the case of Joseph Roger O’Dell III, executed in Virginia in 1997 for a rape and murder, a prosecuting attorney argued in court in 1998 that if posthumous DNA results exonerated O’Dell, «it would be shouted from the rooftops that … Virginia executed an innocent man.» The state prevailed, and the evidence was destroyed.[21]

We-Chank-Wash-ta-don-pee, or Chaska (died December 26, 1862[22]) was a Native American of the Dakota who was executed in a mass hanging near Mankato, Minnesota in the wake of the Dakota War of 1862, despite the fact that President Abraham Lincoln had commuted his death sentence days earlier.[22]

Chipita Rodriguez was hanged in San Patricio County, Texas in 1863 for murdering a horse trader, and 122 years later, the Texas Legislature passed a resolution exonerating her.

Thomas and Meeks Griffin were executed in South Carolina in 1915 for the murder of a man involved in an interracial affair two years previously but were pardoned 94 years after execution. It is thought that they were arrested and charged because they were viewed as wealthy enough to hire competent legal counsel and get an acquittal.[23]

In 1920, two Italian immigrants, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, were controversially accused of robbery and murder in Braintree, Massachusetts. Anti-Italianism, anti-immigrant, and anti-Anarchist bias were suspected as having heavily influenced the verdict. As details of the trial and the men’s suspected innocence became known, sporadic protests were held in major cities all around the world calling for their release, especially after Portuguese migrant Celestino Madeiros confessed in 1925 to committing the crime absolving them of participation.[24] However, the Supreme Court refused to upset the verdict, and in spite of worldwide protests, Sacco and Vanzetti were eventually executed in 1927.[25][26] On August 23, 1977, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis issued a proclamation vindicating Sacco and Vanzetti, stating that they had been treated unjustly and that «any disgrace should be forever removed from their names».[27] Later analyses have also added doubt to their culpability.[28][29][30]

Joe Arridy (1915–1939) was a mentally disabled American man executed for rape and murder and posthumously granted a pardon. Arridy was sentenced to death for the murder and rape of a 15-year-old schoolgirl from Pueblo, Colorado. He confessed to murdering the girl and assaulting her sister. Due to the sensational nature of the crime precautions were taken to keep him from being hanged by vigilante justice. His sentence was executed after multiple stays on January 6, 1939, in the Colorado gas chamber in the state penitentiary in Canon City, Colorado. Arridy was the first Colorado prisoner posthumously pardoned in January 2011 by Colorado Governor Bill Ritter, a former district attorney, after research had shown that Arridy was very likely not in Pueblo when the crime happened and had been coerced into confessing. Among other things, Arridy had an IQ of 46, which was equal to the mental age of a 6-year-old. He did not even understand that he was going to be executed, and played with a toy train that the warden, Roy Best, had given to him as a present. A man named Frank Aguilar had been executed in 1937 in the Colorado gas chamber for the same crime for which Arridy ended up also being executed. Arridy’s posthumous pardon in 2011 was the first such pardon in Colorado history. A press release from the governor’s office stated, «[A]n overwhelming body of evidence indicates the 23-year-old Arridy was innocent, including false and coerced confessions, the likelihood that Arridy was not in Pueblo at the time of the killing, and an admission of guilt by someone else.» The governor also pointed to Arridy’s intellectual disabilities. The governor said, “Granting a posthumous pardon is an extraordinary remedy. But the tragic conviction of Mr. Arridy and his subsequent execution on Jan. 6, 1939, merit such relief based on the great likelihood that Mr. Arridy was, in fact, innocent of the crime for which he was executed, and his severe mental disability at the time of his trial and execution.»

George Stinney, a 14-year old African-American boy, was electrocuted in South Carolina in 1944 for the murder of Betty June Binnicker, age 11, as well as Mary Emma Thames, age 8. The arrest occurred on March 23, 1944 in Alcolu, inside of Clarendon County, South Carolina. Supposedly, the two girls rode their bikes past Stinney’s house where they asked him and his sister about a certain type of flower; after this encounter, the girls went missing and were found dead in a ditch the following morning. After an hour of interrogation by the officers, a deputy stated that Stinney confessed to the murder. He was the youngest person executed in the United States. More than 70 years later, a judge threw out the conviction, calling it a «great injustice.»[31]

Carlos DeLuna was executed in Texas in December 1989 for stabbing a gas station clerk to death. Subsequent investigations cast strong doubt upon DeLuna’s guilt for the murder of which he had been convicted.[32][33] His execution came about six years after the crime was committed. DeLuna was found blocks away from the crime scene with $149 in his pocket. A wrongful eyewitness testimony and DeLuna’s previous criminal record were used against him.[34] Carlos Hernandez, who many believe to be the true killer, was a repeat violent offender who had a history of assaulting women with knives, and was said to have looked very similar to Carlos DeLuna. Hernandez was reported to have bragged about the killing of Lopez, the gas station clerk. In 1999, Hernandez was imprisoned for attacking his neighbor with a knife.[35]

Jesse Tafero was convicted of murder and executed via electric chair in May 1990 in the state of Florida for the murders of a Florida Highway Patrol officer and a Canadian constable. The conviction of a co-defendant was overturned in 1992 after a recreation of the crime scene indicated a third person had committed the murders.[36] Not only was Tafero wrongly accused, his electric chair malfunctioned as well – three times. As a result, Tafero’s head caught on fire. After this encounter, a debate was focused around humane methods of execution. Lethal injections became more common in the states rather than the electric chair.[37]

Johnny Garrett of Texas was executed in February 1992 for allegedly raping and murdering a nun. In March 2004 cold-case DNA testing identified Leoncio Rueda as the rapist and murderer of another elderly victim killed four months earlier.[38] Immediately following the nun’s murder, prosecutors and police were certain the two cases were committed by the same assailant.[39] The flawed case is explored in a 2008 documentary entitled The Last Word.

Cameron Todd Willingham of Texas was convicted and executed for the death of his three children who died in a house fire. The prosecution charged that the fire was caused by arson. He has not been posthumously exonerated, but the case has gained widespread attention as a possible case of wrongful execution. A number of arson experts have decried the results of the original investigation as faulty. In June 2009, five years after Willingham’s execution, the State of Texas ordered a re-examination of the case. Dr. Craig Beyler found «a finding of arson could not be sustained». Beyler said that key testimony from a fire marshal at Willingham’s trial was «hardly consistent with a scientific mind-set and is more characteristic of mystics or psychics».[40][41] The Texas Forensic Science Commission was scheduled to discuss the report by Beyler at a meeting on October 2, 2009, but two days before the meeting Texas Governor Rick Perry replaced the chair of the commission and two other members. The new chair canceled the meeting, sparking accusations that Perry was interfering with the investigation and using it for his own political advantage.[42][43] In 2010, a four-person panel of the Texas Forensic Science Commission acknowledged that state and local arson investigators used «flawed science» in determining the blaze had been deliberately set.[44]

In 2015, the Justice Department and the FBI formally acknowledged that nearly every examiner in an FBI forensic squad overstated forensic hair matches for two decades before the year 2000.[45][46] Of the 28 forensic examiners testifying to hair matches in a total of 268 trials reviewed, 26 overstated the evidence of forensic hair matches and 95% of the overstatements favored the prosecution. Defendants were sentenced to death in 32 of those 268 cases.

The executions of Nathaniel Woods, Dustin Higgs, and Troy Davis have been cited by some as possible cases of wrongful executions.

In 2003, Juan Catalan was arrested and indicted for the shooting death of 16-year-old Martha Puebla, and was facing capital punishment for the charges. The charges against Catalan were dropped after pre-production footage of an episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm was obtained by his lawyer, showing him in the background of a scene. This corroborated his claim that he was attending a Los Angeles Dodgers baseball game at the time of the murder.[47][48]

Russia[edit]

Aleksandr Kravchenko was executed in 1983 for the 1978 murder of nine year old Yelena Zakotnova in Shakhty, a coal mining town near Rostov-on-Don. Kravchenko as a teenager, had served a prison sentence for the rape and murder of a teenage girl but witnesses said he was not at the scene of Zakotnova’s murder at the time. Under police pressure the witnesses altered their statements and Kravchenko was executed. Later it was found that the girl had been murdered by Andrei Chikatilo, a serial killer nicknamed «the Red Ripper» and «the Butcher of Rostov», who was executed in 1994.[49]

Exonerations and pardons[edit]

Kirk Bloodsworth was the first American to be freed from death row as a result of exoneration by DNA evidence. Bloodsworth was a Marine before he became a waterman on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. At the age of 22, he was wrongly convicted of the murder of a nine-year-old girl; she had been sexually assaulted, strangled, and beaten with a rock. An anonymous call to the police claiming that the witness had seen Bloodsworth with the girl that day, and he matched up with the description from the police sketch. Five witnesses claiming that they saw Bloodsworth with the victim, as well as a statement in his testimony where he claimed that he had «done something terrible that day» that would affect his relationship with his wife, did not help his case. No physical evidence connected Bloodsworth to the crime, but he was still convicted of rape and murder which led to him receiving a death sentence. In 1992, DNA from the crime scene was tested against Bloodsworth’s and found that he could not have been the killer. After serving nine years in prison, he was released in June 1993.[50]

Ray Krone is the 100th American to have been sentenced to death and then later exonerated. Krone was convicted of the murder of Kim Ancona, thirty-six year old victim in Phoenix, Arizona. Ancona had been found nude, fatally stabbed. The physical evidence that the police had to rely on was bite marks on Ancona’s breasts and neck. After Ancona had told a friend that Krone, a regular customer, was going to help her close the bar the previous night, the police brought him in to make a Styrofoam impression of his teeth. After comparing the teeth marks, Krone was arrested for the murder, kidnapping, and sexual assault of Ancona on December 31, 1991. At the trial in 1992, Krone pled innocence, but the teeth mark comparison led the jury to find him guilty and he was sentenced to death as well as a consecutive twenty-one year term of imprisonment.[51] Krone’s family also believed that he was innocent, which led them to spend over $300,000 in order to fight for his freedom.[52]

The Death Penalty Information Center has identified at least 190 former death-row prisoners in the United States who have been exonerated since 1973.[53] DPIC reported in February 2021 that exonerated death-row prisoners had been wrongly convicted and sentenced to death in 29 different states and in 118 different counties. The leading causes of these wrongful capital convictions were official misconduct by police, prosecutors, or other government officials and perjury or false accusation. Underscoring the often intentional nature of wrongful capital convictions, more than half of all exonerations involved both official misconduct and perjury or false accusation, and at least one or the other was present in nearly 83% of the cases. [54]

In the UK, reviews prompted by the Criminal Cases Review Commission have resulted in one pardon and three exonerations for people that were executed between 1950 and 1953 (when the execution rate in England and Wales averaged 17 per year), with compensation being paid. Timothy Evans was granted a posthumous free pardon in 1966. Mahmood Hussein Mattan was convicted in 1952 and was the last person to be hanged in Cardiff, Wales, but had his conviction quashed in 1998. George Kelly was hanged at Liverpool in 1950, but had his conviction quashed by the Court of Appeal in June 2003.[55] Derek Bentley had his conviction quashed in 1998 with the appeal trial judge, Lord Bingham, noting that the original trial judge, Lord Goddard, had denied the defendant «the fair trial which is the birthright of every British citizen.»

Colin Campbell Ross (1892–1922) was an Australian wine-bar owner executed for the murder of a child which became known as The Gun Alley Murder, despite there being evidence that he was innocent. Following his execution, efforts were made to clear his name, and in the 1990s old evidence was re-examined with modern forensic techniques which supported the view that Ross was innocent. In 2006 an appeal for mercy was made to Victoria’s Chief Justice and on 27 May 2008 the Victorian government pardoned Ross in what is believed to be an Australian legal first.[56]

U.S. mental health controversy[edit]

There has been much debate about the justification of imposing capital punishment on individuals who have been diagnosed with mental disabilities. Some have argued that the execution of people with serious mental illness or intellectual disability constitutes cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution.[57] While the U.S. Supreme Court has interpreted cruel and unusual punishment to include those punishments that fail to take into account the defendant’s degree of criminal culpability,[clarification needed] it has never held that it is unconstitutional to apply the death penalty to those with serious mental illness and did not determine that executing intellectually disabled individuals constitutes cruel and unusual punishment until 2002.

In 1986, in Ford v. Wainwright, the US Supreme Court ruled that it is unconstitutional to execute a person who does not understand the reason for or the reality of his or her punishment. The issue of whether it is constitutional to execute those with severe mental illness has repeatedly arisen in the state of Texas, where at least 25 individuals with documented diagnoses of paranoid schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and other severe persistent mental illnesses have been put to death. However, Ford applies only to the mental competency of the prisoner at the time of execution, not to the constitutionality of his or her death sentence. The US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, the federal appeals court that handles cases from Texas, has narrowly construed Ford and has never found a death-row prisoner to be incompetent to be executed. In Panetti v. Quarterman, the Fifth Circuit held that a man with a long history of paranoid schizophrenia was competent to be executed because, despite his delusions, he was aware that the state intended to execute him for committing a particular murder. The US Supreme Court reversed, finding that the Fifth Circuit’s incompetency standard was «too restrictive.» The appropriate Eighth Amendment inquiry, the Court said, was whether Panetti had a «rational understanding» of the reason for his execution, not whether he was aware of the State’s rationale for executing him.[58]

In 2019, in the case of Alabama death-row prisoner Vernon Madison, the Court again addressed the proper standard for determining competency to be executed. Madison had cognitive dementia resulting from a series of strokes that, his lawyers said, left him without a rational understanding of why Alabama intended to execute him. The Alabama courts had declared him competent to be executed, ruling that Panetti applied only to cases in which prisoners understanding of the reasons for their pending execution were distorted by delusional mental illness. In Madison v. Alabama, the US Supreme Court disagreed, holding that the critical inquiry was whether the prisoner had a rational understanding of the reasons for the execution, not the type of disorder that caused him or her to lack a rational understanding.

A distinct, but related, issue in the U.S. death penalty is the constitutionality of applying capital punishment to those with intellectual disability. Intellectual disability is a developmental disorder characterized by significantly subaverage intellectual functioning, substantially impaired daily functioning, and onset during the developmental period. The US Supreme Court first addressed this issue in 1989 in the case of Penry v. Lynaugh, in which Texas death-row prisoner Johnny Paul Penry argued that the application of the death penalty to individuals with mental retardation, as the disorder was then known, constituted cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment. Penry presented evidence that his that his IQ ranged from 50 to 63 — far below the 70-75 IQ level that is typically considered evidence of intellectual disability — and that he possessed the mental abilities of a six-and-a-half-year-old.[57] The Texas state and federal courts denied Penry’s challenge and, in a five-to-four decision, the US Supreme Court ruled that the Eighth Amendment did not categorically prohibit the execution of individuals with mental retardation. Following the ruling, sixteen states as well as the federal government passed legislation that banned the execution of offenders with mental retardation.[57]

The Supreme Court revisited Penry in 2002 in the case of Atkins v. Virginia. By a vote of 6-3, the Court held that the Eighth Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment applied to those with intellectual disability. The Court referred to the clinical definitions of the disorder in use by the medical community but ultimately left to the states the determination of who qualified as intellectually disabled.[59]

In 2014, the Supreme Court ruled in Hall v. Florida that states cannot apply an IQ cut-off score of 70 to arbitrarily limit which individuals qualify as intellectually disabled.[60] Then, in 2017 in Moore v. Texas, the Court struck down Texas’s use of a series of clinically inappropriate lay stereotypes that denied intellectually disabled defendants Eighth Amendment protection.

See also[edit]

- Capital punishment debate

- Cold case (criminology)

- Charles Hudspeth (convict)

- Extrajudicial punishment

- List of exonerated death row inmates

- List of United States death row inmates

- List of wrongful convictions in the United States

- Miscarriage of justice

- Cameron Todd Willingham

References[edit]

- ^ «Innocence and the Death Penalty». Death Penalty Information Center.

- ^ Kreuter, William. «The Innocent Executed». Justice Denied, the Magazine for the Wrongly Convicted.

- ^ Keys, Karl (2001). «Thirty Years of Executions with Reasonable Doubts: A Brief Analysis of Some Modern Executions». Capital Defense Weekly. Archived from the original on 4 August 2007.

- ^ «DNA Exoneree Case Profiles». www.innocenceproject.org. Archived from the original on 18 December 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ «DPIC Special Report: The Innocence Epidemic». Death Penalty Information Center.

- ^ «Executed But Possibly Innocent». Death Penalty Information Center.

- ^ Colloquium: The Past, Present, and Future of the Death Penalty. University of Tennessee College of Law. 2009. pp. 617–619.

- ^ «Wrongful Convictions in Australia». Sydney Criminal Lawyers. 11 June 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ «魏清安案:法院枪口下还有多少冤案待昭雪?–法治新闻-中顾法律网». News.9ask.cn. 21 July 2010. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- ^ «滕兴善 – 个比佘祥林更加悲惨的人–搜狐新闻». News.sohu.com. 2 April 2007. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- ^ «聂树斌案材料 –《刑事申诉书》 – 包头律师专家服务网». Zwjkey.com. 8 July 2007. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- ^ «南方周末 — 聂树斌案,拖痛两个不幸家庭(2012年2月9日)». Infzm.com. 10 February 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- ^ Zhuang, Pinghui (9 February 2015). «China’s ‘smiling killer’ sentenced to death for 1996 murder that saw innocent teenager executed». South China Morning Post. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ McGuier, Erin (6 April 2015). «How Harry Gleeson was wrongly hanged for murder in 1941». The Irish Times. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ Driscoll, Anne (17 August 2015). «Special Report (Wrongful Convictions): Time to shine a light on the innocent». Irish Examiner. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ Sui, Cindy (27 October 2015). «Taiwan pays compensation for wrongful execution». BBC Asia-Pacific. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ Bowccott, Owen (11 June 2003). «Man hanged 53 years ago was innocent». The Guardian. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- ^ Yallop, David (1991). To Encourage The Others. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-552-13451-4

- ^ «US death row study: 4% of defendants sentenced to die are innocent». The Guardian. 28 April 2014.

- ^ Maron, Dina Fine (28 April 2014). «Many Prisoners on Death Row are Wrongfully Convicted». Scientific American. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Lois Romano, «When DNA Meets Death Row, It’s the System That’s Tested Archived 2013-08-06 at the Wayback Machine», Washington Post, December 12, 2003.

- ^ a b Elder, Robert (13 December 2010). «Execution 155 Years Ago Spurs Calls for Pardon». New York Times. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ «Tom Joyner gets justice for electrocuted kin, 94 years later». CNN. 15 October 2009.

- ^ Watson, 257-60; Tropp reproduces the original note Medeiros passed to Sacco in prison, Tropp, 34; on Medeiros’s early life, see Russell, Case Resolved, 127–8

- ^ Paul Avrich, Sacco and Vanzetti: The Anarchist Background, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991.

- ^ Eli Bortman, Sacco & Vanzetti. Boston: Commonwealth Editions, 2005.

- ^ «Report to the Governor in the Matter of Sacco and Vanzetti,» July 13, 1977, in Upton Sinclair, Boston: A Documentary Novel (Cambridge, MA: Robert Bentley, Inc., 1978), 757–90, quote 757

- ^ Douglas Walton (2005). Argumentation Methods for Artificial Intelligence in Law. p. 36. ISBN 9783540278818. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ (State), California. California. Supreme Court. Records and Briefs: S014605. p. 29. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Innocence and the Death Penalty: Hearing Before the Committee on the Judiciary. 1 April 1993. p. 157. ISBN 9780160442032. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Jeffrey Collins, «70 years later, judge rules 14-year-old boy was wrongly executed», «The Christian Science Monitor», December 17, 2014.

- ^ Andrew Cohen, «Yes, America, We Have Executed an Innocent Man», The Atlantic Monthly, May 14, 2012.

- ^ Pilkington, Ed (15 May 2012) The wrong Carlos: how Texas sent an innocent man to his death The Guardian, Retrieved 15 May 2012

- ^ McLaughlin, Michael (15 May 2012). «Carlos DeLuna Execution: Texas Put To Death An Innocent Man, Columbia University Team Says». Huffington Post. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ «The Carlos DeLuna case: Definitive proof that Texas executed an innocent man?». 16 May 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ «Center on Wrongful Convictions: Jesse J. Tafero». Northwestern University School of Law. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ «An inhumane execution – May 04, 1990». History.com. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ Photo Gallery, FBI Documents Gallery, Police Reports Gallery, Crime Scene and Evidence Gallery, Correspondence Gallery, Videotape Interviews, and Full Case Documentation, by Bloodshed Books Corporation, http://www.bloodshedbooks.com/tour.php

- ^ The Skeptical Juror, «Actual Innocence: Johnny Frank Garrett and Bubbles the Clairvoyant», http://www.skepticaljuror.com/2010/04/fine-folks-of-amarillo-wanted-justice.html

- ^ Grann, David (7 September 2009). «Trial by Fire: Did Texas execute an innocent man?». The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011.

- ^ Beyler, Craig L. (17 August 2009). «Analysis of the Fire Investigation Methods and Procedures Used in the Criminal Arson Cases Against Ernest Ray Willis and Cameron Todd Willingham». Hughes Associates, Inc. Archived from the original on 8 February 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

- ^ «CNN’s Anderson Cooper 360: «Is Texas Governor Rick Perry Trying to Cover Up Execution of Innocent Man on His Watch»«. «Texas Moratorium Network» (camerontoddwillingham.com). 3 October 2009. Archived from the original on 9 October 2011.

- ^ Smith, Matt (2 October 2009). «Shake-up in Texas execution probe draws criticism, questions». CNN. Archived from the original on 23 July 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ Turner, Allan (24 July 2010). «Flawed science» helped lead to Texas man’s execution, but inquiry finds no negligence in probe that led to man’s execution». Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- ^ «FBI overstated forensic hair matches in nearly all trials before 2000». The Washington Post. 18 April 2015.

- ^ «Report: DOJ, FBI acknowledge flawed testimony from unit». Associated Press. 18 April 2015.

- ^ «How ‘Curb Your Enthusiasm’ Saved an Innocent Man from Death Row». 29 September 2017.

- ^ «Beating the (False) Rap: Life After Netflix’s ‘Long Shot’«. Los Angeles Magazine. 15 December 2021.

- ^ Conradi, Peter (1991). The Red Ripper: Inside the Mind of Russia’s Most Brutal Serial Killer. True Crime. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0863696183.

- ^ «Innocence Project: The Cases — Kirk Bloodsworth». Innocence Project. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ «Ray Krone — Innocence Project». Innocence Project. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ «Twice Wrongly Convicted of Murder — Ray Krone Is Set Free After 10 Years». forejustice.org. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ Death Penalty Information Center, Innocence, https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/policy-issues/innocence, last visited November 26, 2022.

- ^ Death Penalty Information Center, DPIC Special Report: The Innocence Epidemic, https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/facts-and-research/dpic-reports/dpic-special-reports/dpic-special-report-the-innocence-epidemic, February 18, 2021.

- ^ George Kelly exonerated 53 years after being executed

- ^ The Age: Ross cleared of murder nearly 90 years ago. Retrieved 27 May 2008.

- ^ a b c Scott, Charles (1 January 2003). «Atkins v. Virginia: Execution of Mentally Retarded Defendants Revisited». The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 31 (1): 101–104. PMID 12817850.

- ^ «TCADP – Texas Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty». tcadp.org. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ^ Cohen, Andrew (22 October 2013). «At Last, the Supreme Court Turns to Mental Disability and the Death Penalty». The Atlantic.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (27 May 2014). «Court Extends Curbs on the Death Penalty in a Florida Ruling». The New York Times.

- August Ludwig von Schlözer: Abermaliger JustizMord in der Schweiz In: Stats-Anzeigen. Band 2. Göttingen, 1782. S. 273–277.

- Julius Mühlfeld. Justizmorde. Nach amtlichen Quellen bearbeitete Auswahl 2. Auflage, Berlin (1880) OCLC 70475784

- Bernt Ture von zur Mühlen. Napoleons Justizmord am deutschen Buchhändler Johann Philipp Palm. Frankfurt am Main: Braman Verlag (2003) ISBN 9783934054165

External links[edit]

- Death Penalty Information Center – anti-death penalty organisation

- Justice Denied magazine includes stories of supposedly innocent people who have been executed.

- Database of convicted people said to be innocent includes 150 allegedly wrongfully executed.

- Letter by Voltaire to Frederick II, April 1777[dead link]

«False execution» redirects here. For the situation where a person falsely believes they will be executed, see Mock execution.

Wrongful execution is a miscarriage of justice occurring when an innocent person is put to death by capital punishment. Cases of wrongful execution are cited as an argument by opponents of capital punishment, while proponents say that the argument of innocence concerns the credibility of the justice system as a whole and does not solely undermine the use of the death penalty.[1]

A variety of individuals are claimed to have been innocent victims of the death penalty.[2][3] Newly available DNA evidence has allowed the exoneration and release of more than 20 death-row inmates since 1992 in the United States,[4] but DNA evidence is available in only a fraction of capital cases. At least 190 people who were sentenced to death in the United States have been exonerated and released since 1973, with official misconduct and perjury/false accusation the leading causes of their wrongful convictions.[5] The Death Penalty Information Center (U.S.) has published a partial listing of wrongful executions that, as of the end of 2020, identified 20 death-row prisoners who were «executed but possibly innocent».[6]

Judicial murder is a type of wrongful execution.[7]

Specific examples[edit]

Australia[edit]

Colin Campbell Ross was hanged in Melbourne in 1922 for the murder of 12-year-old Alma Tirtschke the previous year in what became known as the Gun Alley Murder. The case was re-examined in the 1990s using modern techniques and Ross was eventually pardoned in 2008, by which time capital punishment in Australia had been abolished in all jurisdictions.

Ronald Ryan was the last person executed in Australia. His execution took place on 3 February 1967. He and a fellow inmate, Peter John Walker, attempted to escape from Pentridge Prison on 19 December 1965, when prison guard George Hodgson was shot and killed. Multiple witnesses swore that they saw Ryan fire the shot that killed Hodgson, so he was found guilty. The true identity of the shooter is in contention as two other guards admitted to firing several shots, and in 2007, Peter John Walker said that it would have been impossible for Ryan to have shot the guard as his rifle had jammed.[8]

People’s Republic of China[edit]

Wei Qing’an (Chinese: 魏清安, born 1961) was a Chinese citizen who was executed for the rape of Kun Liu, a woman who had disappeared. The execution was carried out on 3 May 1984 by the Intermediate People’s Court. In the next month, Tian Yuxiu (田玉修) was arrested and admitted that he had committed the rape. Three years later, Wei was officially declared innocent.[9]

Teng Xingshan (Chinese: 滕兴善) was a Chinese citizen who was executed for supposedly having raped, robbed and murdered Shi Xiaorong (石小荣), a woman who had disappeared. An old man found a dismembered body, and incompetent police forensics claimed to have matched the body to the photo of the missing Shi Xiaorong. The execution was carried out on 28 January 1989 by the Huaihua Intermediate People’s Court. In 1993, the previously missing woman returned to the village, saying she had been kidnapped and taken to Shandong. The absolute innocence of the wrongfully executed Teng was not admitted until 2005.[10]

Nie Shubin (Chinese: 聂树斌, born 1974) was a Chinese citizen who was executed for the rape and murder of Kang Juhua (康菊花), a woman in her thirties. The execution was carried out on 27 April 1995 by the Shijiazhuang Intermediate People’s Court. In 2005, ten years after the execution, Wang Shujin (王书金; Wáng Shūjīn) admitted to the police that he had committed the murder.[11][12]

Qoγsiletu or Huugjilt (Mongolian: Qoγsiletu, Chinese: 呼格吉勒图, born 1977) was an Inner Mongolian who was executed for the rape and murder of a young girl on 10 June 1996. On 5 December 2006, ten years after the execution, Zhao Zhihong (Chinese: 赵志红) wrote the Petition of my Death Penalty admitting he had committed the crime. Huugjilt was posthumously exonerated and Zhao Zhihong was sentenced to death in 2015.[13]

Ireland[edit]

Sir Edward Crosbie, 5th Baronet was wrongfully executed in Carlow in 1798. Accused of being a United Irishman, his innocence was later proved.

Harry Gleeson was executed in Ireland in April 1941 for the murder of Moll McCarthy in County Tipperary in November 1940. The Gardaí withheld crucial evidence and fabricated other evidence against Gleeson. In 2015, he was posthumously pardoned.[14][15]

Taiwan[edit]