В Германии, где

экзистенциализм стал развиваться после

Первой мировой войны 1914-1918 гг., крупным

представителем этого течения был Карл

Ясперс (1883-1969). По образованию медик,

написал специальные работы «Всеобщая

психопатология», «Психология

мировоззрений». В 1937г. За свои

демократические убеждения был удален

фашистами из Гейдельберского университета,

где занимал должность профессора.

Основные философские труды мыслителя:

трехтомник «Философия»; написанные в

30-е годы «Разум и экзистенция», «Ницше»,

«Декарт и философия», «Экзистенциальная

философия», и др.

Ясперс рассматривал

ставшую уже традиционной, но и поныне

актуальную проблему соотношения научной

деятельности, способствует преодолению

в ней узости, доктринерства и догматизма.

Философия устанавливает истину, а не

пресловутую «научную точность». Наука

питает философию результатами своих

исследований, данными опыта и теоретическими

открытиями. К особенностям научного

знания, отличного от философского, было

отнесено то, что наука познает не само

бытие, а отдельные вещи; наука не обладает

способностью направлять жизнь,

устанавливать ценности и решать проблемы

человека; экзистенция науки основана

на импульсах, а не на поисках собственного

смысла.

Человека, по Ясперсу,

надо понять как экзистенцию. Это

центральное понятие экзистенциализма.

Экзистенция — это в

отличие от эмпирического бытия человека,

«сознания вообще» и «духа» есть такой

«уровень» человеческого бытия, который

уже не может стать предметом рассмотрения

науки. «Экзистенция,- пишет Ясперс, —

есть то, что никогда не становится

объектом, есть источник моего мышления

действия, о котором я говорю в таком

ходе мысли, где ничего не познается».

Основателем французского

католического экзистенциализма

был Габриэль МАРСЕЛЬ.

Его философия носит

ярко выраженный религиозный характер.

Марсель, считая невозможным и неприемлемым

научное обоснование религии, отвергает

рациональные доказательства бытия бога

и утверждает, что бог принадлежит особому

миру «существования», недоступному

для объективнойнауки.

Бог, по Марселю, существует, но не обладает

объективной реальностью, не принадлежит

миру «вещей»; он «непредставляем»,

«неопределим», его нельзя мыслить:

«мыслить веру — значит уже не верить».

Таким образом, апология христианства

Марселя резко отличается от традиционного

от католицизма схоластического метода.

30. Феноменология э .Гуссерля. Понятие интенциональности.

Феноменологическая

философия Э. Гуссерля

Возникновение

феноменологии как философского

течения связано с творчеством Эдмунда

Гуссерля (1859 — 1938). После защиты

диссертации по математике, он начал

свою научную деятельность в качестве

ассистента выдающегося математика

конца XIX в. К. Т. В. Вейерштрасса. Однако

постепенно происходит изменение его

научных интересов в пользу философии.

Философские взгляды

Э. Гуссерля формировались под

влиянием крупнейших философов XIX в.

Особую роль в формировании его взглядов

сыграли идеи Бернарда Больцано (1781 —

1848) и Франца Брентано (1838 — 1917). Первый

критиковал психологизм и полагал, что

истины могут существовать независимо

от того, выражены они или нет. Этот

взгляд, будучи воспринятым Гуссерлем,

содействовал его стремлению очистить

познавательный процесс от наслоений

психологизма.

От Брентано Гуссерль

воспринял идею интенциональности. По

Брентано, интенциональность «есть то,

что позволяет типизировать психологические

феномены». Интен-циональность в

феноменологии понимается как направленность

сознания на предмет, свойство переживать.

Свои идеи Э. Гуссерль

изложил в следующих работах: «Логические

исследования» (1901), «Философия как

строгая наука» (1911), «Идеи чистой

феноменологии и феноменологической

философии» (1913), «Трансцендентальная

логика и формальная логика» (1921),

«Картезианские размышления» (1931). В 1954

г. была опубликована рукописная работа

«Кризис европейских наук и трансцендентальная

феноменология», написанная за два года

до смерти, и другие работы.

Значительная часть

работ мыслителя переведена на русский

язык.

Особенность философии

Э. Гуссерля состояла в выработке

нового метода. Суть этого метода

отразилась в лозунге «Назад к вещам!»

Разобраться в том, что такое вещи, по

Гуссерлю, можно лишь через описание

«феноменов», т. е. явлений, «которые

предстают сознанию после осуществления

«эпохе», т. е. после заключения в скобки

наших философских воззрений и убеждений,

связанных с нашей естественной установкой,

которая навязывает нам веру в существование

мира вещей».

Феноменологический

метод, по мнению Э. Гуссерля, помогает

постичь сущность вещей, а не факты. Так,

«феноменолога не интересует та или иная

моральная норма, его интересует, почему

она — норма. Изучить обряды и гимны той

или иной религии, несомненно, важно, но

важнее понять, что такое религиозность

вообще, что делает разные обряды и

несхожие песнопения религиозными».

Феноменологический анализ вникает в

состояние, скажем, стыда, святости,

справедливости с точки зрения их

сущности.

«Предмет феноменологии —

царство чистых истин, априорных смыслов

— как актуальных, так и возможных, как

реализовавшихся языке, так и мыслимых.

Феноменология определяется Гуссерлем

как «первая философия», как наука о

чистых принципах сознания и знания, как

универсальное учение о методе, выявляющее

априорные условия мыслимости предметов

и чистые структуры сознания независимо

от сфер их приложения. Познание

рассматривается как поток сознания,

внутренне организованный и целостный,

однако относительно независимый от

конкретных психических актов, от субъекта

познания и его деятельности.

Феноменологическая

установка реализуется с помощью метода

редукции (также эпохе). На этом пути

достигается понимание субъекта познания

не как эмпирического, а как трансцендентального

субъекта», т. е. перешагивающего,

выходящего за пределы конечного

эмпирического мира, способного иметь

доопытное знание. Способность к

непосредственному усмотрению

объективно-идеальной основы языковых

выражений называется Гуссерлем идеацией.

Допущение возможности исследования

этой способности в рамках феноменологии

превращает ее в науку о способе постижения

мира через анализ «чистого сознания».

Так как сознание, субъективность нельзя

взять в скобки, оно и выступает основанием

всякой реальности. Мир, по мнению

Гуссерля, конструируется сознанием.

Судя по высказываниям

Э. Гуссерля, феноменологический метод

призван был превратить философию в

строгую науку, т. е. теорию научного

познания, способную дать правильное

представление о «жизненном мире» и его

конструировании.

Новая философия с ее

особым, обещающим достижение более

глубоких знаний методом, согласно Э.

Гуссерлю, необходима потому, что старая

философия не давала того уровня глубины

знания, опираясь на которое человечество

могло бы развиваться благополучно.

Именно в недостатках прежней философии,

по Гуссерлю, надо искать причины кризиса

европейских наук и кризиса европейской

цивилизации. Такие мысли мы находим в

ранее упоминавшихся работах Э. Гуссерля:

«Кризис европейских наук и трансцендентальная

феноменология» (1934 — 1937), «Картезианские

размышления» (1931), «Кризис европейского

человечества и философия» (1935).

По мнению Гуссерля,

кризис науки и философии обусловлен

тем, что удовлетворявшие всех ученых,

ранее существовавшие критерии научности

перестали действовать. Прежние нормативные

устои миропонимания, мироустройства

стали зыбкими.

«Поскольку вера в

абсолютный разум, придающий смысл миру,

рухнула, постольку рухнула и вера в

смысл истории, в смысл человечества,

его свободу, понимаемую как возможность

человека обрести разумный смысл всего

индивидуального и общественного бытия».

Мир как бы борется

против стремящейся его упорядочить с

помощью нормативных установок философии

и науки. Но для обеспечения жизни людей

он нуждается в организации с помощью

норм. Эта нужда постоянна, она изнуряет

познающий разум. Философия и наука в

некоторые моменты истории «устают» и

начинают отставать в своих реакциях на

запросы мира. Философия и наука как бы

попадают в состояние растерянности. В

них начинается разнобой.

В этот период, что

характерно и для Европы в XX в., «вместо

единой живой философии, отмечает

Гуссерль, мы имеем выходящий из берегов,

но почти бессвязный поток философской

литературы: вместо серьезной полемики

противоборствующих теорий, которые в

споре обнаруживают свое внутреннее

единство, свое согласие в основных

убеждениях и непоколебимую веру в

истинную философию, мы имеем лишь

видимость научных выступлений и видимость

критики, одну лишь видимость серьезного

философского общения друг с другом и

друг для друга. Это менее всего

свидетельствует об исполненных сознания

ответственности совместных научных

занятиях в духе серьезного сотрудничества

и нацеленности на объективно значимые

результаты. Объективно значимые — т.

е. именно очищенные во всесторонней

критики и устоявшие перед всякой критикой

результаты. Да и как были бы возможны

подлинно научные занятия и действительное

сотрудничество там, где так много

философов и почти столько же различных

философий».

Для преодоления этого

Гуссерль считает необходимым «привести

латентный (скрытый — С. Н.) разум к

самопознанию своих возможностей и тем

самым прояснить возможность метафизики

как истинную возможность — таков

единственный путь действительного

осуществления метафизики или универсальной

философии».

Приведение разума к

познанию своих возможностей и раскрытие

возможностей мудрости осуществляется

для Гуссерля с помощью философии.

По его мнению, философия

«в изначальном смысле обозначает не

что иное как универсальную науку, науку

о мировом целом, о всеохватывающем

единстве всего сущего». Далее он

продолжает: «Философия, наука — это

название особого класса культурных

образований. Историческое движение,

принявшее стилевую форму европейской

сверхнауки, ориентировано на лежащий

в бесконечности нормативный образ, не

на такой однако, который можно было бы

вывести путем чистого внешнего

морфологического наблюдения структурных

перемен. Постоянная направленность на

норму внутренне присуща интернациональной

жизни отдельной личности, а отсюда и

нациям с их особенными общностями и,

наконец, всему организму соединенных

Европейских наций».

Согласно Гуссерлю,

стремление к идеальному нормированию

жизни и деятельности, возникнув в Древней

Греции, открыло для человечества путь

в бесконечность. Это стремление к

идеальному формированию и организации

жизни основано на определенной установке.

Известны мифо-религиозная, практическая

и теоретическая установки. Западная

наука базируется, согласно Гуссерлю,

на теоретической установке. Теоретическая

установка западного философа предполагает

включение в интеллектуальную деятельность,

направленную на поиск норм, облегчающих

познание и практику. Гуссерль полагал,

что благодаря философии, идеи которой

передаются в ходе образования, формируется

идеально ориентированная социальность.

Мыслитель пишет: «В этой идеально

ориентированной социальности сама

философия продолжает выполнять ведущую

функцию и решать свою собственную

бесконечную задачу — функцию свободной

и универсальной теоретической рефлексии,

охватывающей все идеалы и всеобщий

идеал, т. е. универсум всех норм».

Гуссерль

считал, что объяснение кризиса науки

кажущимся крушением рациональности

неоправданно. Он подчеркивал: «Причина

затруднений рациональной культуры

заключается… не в сущности самого

рационализма, но лишь в его овнешнении,

в его извращении «натурализмом» и

«объективизмом»». Приводит к правильному

пониманию рациональности феноменологическая

философия, которая строится на анализе

и прояснении феноменов сознания и

черпает из них подлинное знание, которое

призвано сложиться в философию как

строгую науку, объединяющую все

человечество.

ИНТЕНЦИОНАЛЬНОСТЬ

(от лат. intentio —

стремление) — в феноменологии — первичная

смыслообразующая устремленность

сознания к миру, смыслоформирующее

отношение сознания к предмету, предметная

интерпретация ощущений. Термин «И.»,

точнее «интенция», широко использовавшийся

в схоластике, в современную философию

ввел Ф. Брентано, для которого И. —

критерий различия психических и

физических феноменов. Ключевым это

понятие становится у Э. Гуссерля,

понимавшего И. как акт придания смысла

(значения) предмету при постоянной

возможности различения предмета и

смысла. Направленность сознания на

предметы, отношение сознания к предметам

— все эти определения И. требуют

дальнейших структурных описаний, ибо

речь идет не об отношении двух вещей

или части и целого. С т.зр. Гуссерля,

ошибочно полагать, что является предмет

и наряду с ним интенциональное переживание,

которое на него направлено. Сознание

направлено на предмет, но не на значение

предмета, не на переживание смысла

предмета — последнее и есть направленность

сознания в феноменологическом смысле

слова. И. — структура переживания,

фундаментальное свойство переживания

быть «сознанием о…». В отличие от

Брентано, у Гуссерля И. не есть признак,

различающий внутреннее и внешнее —

психические и физические феномены. Не

все, относящееся к сфере психического,

интенционально, напр., простые данные

ощущений, которые предметно интерпретируются.

Структура переживания не зависит от

того, реален или нереален предмет

сознания. В общем виде структура И. —

различие и единство интенционального

акта, интенционального содержания и

предмета. Для описания общей структуры

И. Гуссерль вводит в «Идеях к чистой

феноменологии и феноменологической

философии» термины антич. философии

«ноэсис» и «ноэма». Ноэтические компоненты

переживания (ноэсис) характеризуют

направленность сознания на предмет как

акт придания смысла. Вместе с «оживляемым»

ими чувственным материалом, или

«гилетическими данными» (от. греч. hyle —

материя), они составляют предмет

«реального» анализа, в котором переживание

предстает как непрерывная вариация,

поток феноменологического бытия с его

определенными частями и моментами,

актуальными и потенциальными фазами.

Ин-тенциональный анализ направлен на

ноэматический коррелят акта (ноэму) —

предметный смысл как таковой, а также

на устойчивое единство смысловых слоев

предмета. Корреляция между ноэсисом и

ноэмой (необходимый параллелизм между

актом и его содержанием) не тождественна

направленности сознания на предмет.

Эта корреляция должна быть охарактеризована

не только с ноэтической (акт),

но и с ноэматической стороны: в структуре

ноэмы различаются предмет в определенном

смысловом ракурсе (содержание)

и «предмет как таковой», который выступает

для сознания как чистое предметное

«нечто». В экзистенциализме Ж.П. Сартра

И. выражает постоянное напряжение между

человеческой реальностью и миром, их

нераздельность и взаимную несводимость,

которая обнаруживает онтологическую

значимость человеческого бытия. В

аналитическую философию тема И. вошла

благодаря книге Э. Энскомб «Интенция»

(1957), в которой она обсуждала возможности

описания интенционального поведения.

Затем это понятие стало широко

использоваться в аналитической философии

сознания (напр., у Дж. Сёрла).

For the philosophical position commonly seen as the antonym of existentialism, see Essentialism.

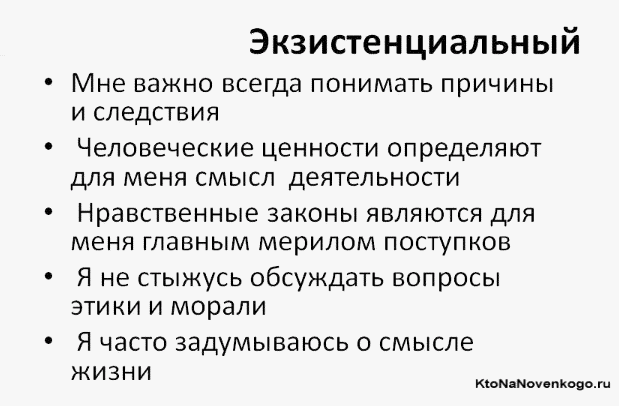

Existentialism ( [1] )[2] is a form of philosophical inquiry that explores the issue of human existence.[3][4] Existentialist philosophers explore questions related to the meaning, purpose, and value of human existence. Common concepts in existentialist thought include existential crisis, dread, and anxiety in the face of an absurd world, as well as authenticity, courage, and virtue.[5]

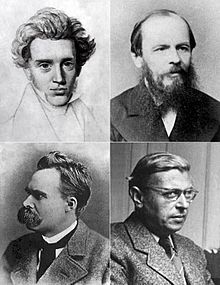

Existentialism is associated with several 19th- and 20th-century European philosophers who shared an emphasis on the human subject, despite often profound differences in thought.[6][4][7] Among the earliest figures associated with existentialism are philosophers Søren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche and novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky, all of whom critiqued rationalism and concerned themselves with the problem of meaning. In the 20th century, prominent existentialist thinkers included Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, Martin Heidegger, Simone de Beauvoir, Karl Jaspers, Gabriel Marcel, and Paul Tillich.

Many existentialists considered traditional systematic or academic philosophies, in style and content, to be too abstract and removed from concrete human experience.[8][9] A primary virtue in existentialist thought is authenticity.[10] Existentialism would influence many disciplines outside of philosophy, including theology, drama, art, literature, and psychology.[11]

Etymology[edit]

The term existentialism (French: L’existentialisme) was coined by the French Catholic philosopher Gabriel Marcel in the mid-1940s.[12][13][14] When Marcel first applied the term to Jean-Paul Sartre, at a colloquium in 1945, Sartre rejected it.[15] Sartre subsequently changed his mind and, on October 29, 1945, publicly adopted the existentialist label in a lecture to the Club Maintenant in Paris, published as L’existentialisme est un humanisme (Existentialism Is a Humanism), a short book that helped popularize existentialist thought.[16] Marcel later came to reject the label himself in favour of Neo-Socratic, in honor of Kierkegaard’s essay «On the Concept of Irony».

Some scholars argue that the term should be used to refer only to the cultural movement in Europe in the 1940s and 1950s associated with the works of the philosophers Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and Albert Camus.[6] Others extend the term to Kierkegaard, and yet others extend it as far back as Socrates.[17] However, it is often identified with the philosophical views of Sartre.[6]

Definitional issues and background[edit]

The labels existentialism and existentialist are often seen as historical conveniences in as much as they were first applied to many philosophers long after they had died. While existentialism is generally considered to have originated with Kierkegaard, the first prominent existentialist philosopher to adopt the term as a self-description was Sartre. Sartre posits the idea that «what all existentialists have in common is the fundamental doctrine that existence precedes essence,» as the philosopher Frederick Copleston explains.[18] According to philosopher Steven Crowell, defining existentialism has been relatively difficult, and he argues that it is better understood as a general approach used to reject certain systematic philosophies rather than as a systematic philosophy itself.[6] In a lecture delivered in 1945, Sartre described existentialism as «the attempt to draw all the consequences from a position of consistent atheism.»[19] For others, existentialism need not involve the rejection of God, but rather «examines mortal man’s search for meaning in a meaningless universe,» considering less «What is the good life?» (to feel, be, or do, good), instead asking «What is life good for?»[20]

Although many outside Scandinavia consider the term existentialism to have originated from Kierkegaard, it is more likely that Kierkegaard adopted this term (or at least the term «existential» as a description of his philosophy) from the Norwegian poet and literary critic Johan Sebastian Cammermeyer Welhaven.[21] This assertion comes from two sources:

- The Norwegian philosopher Erik Lundestad refers to the Danish philosopher Fredrik Christian Sibbern. Sibbern is supposed to have had two conversations in 1841, the first with Welhaven and the second with Kierkegaard. It is in the first conversation that it is believed that Welhaven came up with «a word that he said covered a certain thinking, which had a close and positive attitude to life, a relationship he described as existential.»[22] This was then brought to Kierkegaard by Sibbern.

- The second claim comes from the Norwegian historian Rune Slagstad, who claimed to prove that Kierkegaard himself said the term «existential» was borrowed from the poet. He strongly believes that it was Kierkegaard himself who said that «Hegelians do not study philosophy ‘existentially;’ to use a phrase by Welhaven from one time when I spoke with him about philosophy.»[23]

Concepts[edit]

Existence precedes essence[edit]

Sartre argued that a central proposition of existentialism is that existence precedes essence, which is to say that individuals shape themselves by existing and cannot be perceived through preconceived and a priori categories, an «essence». The actual life of the individual is what constitutes what could be called their «true essence» instead of an arbitrarily attributed essence others use to define them. Human beings, through their own consciousness, create their own values and determine a meaning to their life.[24] This view is in contradiction to Aristotle and Aquinas who taught that essence precedes individual existence.[25] Although it was Sartre who explicitly coined the phrase, similar notions can be found in the thought of existentialist philosophers such as Heidegger, and Kierkegaard:

The subjective thinker’s form, the form of his communication, is his style. His form must be just as manifold as are the opposites that he holds together. The systematic eins, zwei, drei is an abstract form that also must inevitably run into trouble whenever it is to be applied to the concrete. To the same degree as the subjective thinker is concrete, to that same degree his form must also be concretely dialectical. But just as he himself is not a poet, not an ethicist, not a dialectician, so also his form is none of these directly. His form must first and last be related to existence, and in this regard he must have at his disposal the poetic, the ethical, the dialectical, the religious. Subordinate character, setting, etc., which belong to the well-balanced character of the esthetic production, are in themselves breadth; the subjective thinker has only one setting—existence—and has nothing to do with localities and such things. The setting is not the fairyland of the imagination, where poetry produces consummation, nor is the setting laid in England, and historical accuracy is not a concern. The setting is inwardness in existing as a human being; the concretion is the relation of the existence-categories to one another. Historical accuracy and historical actuality are breadth.

— Søren Kierkegaard (Concluding Postscript, Hong pp. 357–358.)

Some interpret the imperative to define oneself as meaning that anyone can wish to be anything. However, an existentialist philosopher would say such a wish constitutes an inauthentic existence – what Sartre would call «bad faith». Instead, the phrase should be taken to say that people are defined only insofar as they act and that they are responsible for their actions. Someone who acts cruelly towards other people is, by that act, defined as a cruel person. Such persons are themselves responsible for their new identity (cruel persons). This is opposed to their genes, or human nature, bearing the blame.

As Sartre said in his lecture Existentialism is a Humanism: «Man first of all exists, encounters himself, surges up in the world—and defines himself afterwards.» The more positive, therapeutic aspect of this is also implied: a person can choose to act in a different way, and to be a good person instead of a cruel person.[26]

Jonathan Webber interprets Sartre’s usage of the term essence not in a modal fashion, i.e. as necessary features, but in a teleological fashion: «an essence is the relational property of having a set of parts ordered in such a way as to collectively perform some activity».[27]: 3 [6] For example, it belongs to the essence of a house to keep the bad weather out, which is why it has walls and a roof. Humans are different from houses because—unlike houses—they do not have an inbuilt purpose: they are free to choose their own purpose and thereby shape their essence; thus, their existence precedes their essence.[27]: 1–4

Sartre is committed to a radical conception of freedom: nothing fixes our purpose but we ourselves, our projects have no weight or inertia except for our endorsement of them.[28][29] Simone de Beauvoir, on the other hand, holds that there are various factors, grouped together under the term sedimentation, that offer resistance to attempts to change our direction in life. Sedimentations are themselves products of past choices and can be changed by choosing differently in the present, but such changes happen slowly. They are a force of inertia that shapes the agent’s evaluative outlook on the world until the transition is complete.[27]: 5, 9, 66

Sartre’s definition of existentialism was based on Heidegger’s magnum opus Being and Time (1927). In the correspondence with Jean Beaufret later published as the Letter on Humanism, Heidegger implied that Sartre misunderstood him for his own purposes of subjectivism, and that he did not mean that actions take precedence over being so long as those actions were not reflected upon.[30] Heidegger commented that «the reversal of a metaphysical statement remains a metaphysical statement», meaning that he thought Sartre had simply switched the roles traditionally attributed to essence and existence without interrogating these concepts and their history.[31]

The Absurd[edit]

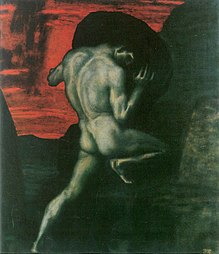

The notion of the absurd contains the idea that there is no meaning in the world beyond what meaning we give it. This meaninglessness also encompasses the amorality or «unfairness» of the world. This can be highlighted in the way it opposes the traditional Abrahamic religious perspective, which establishes that life’s purpose is the fulfillment of God’s commandments.[32] This is what gives meaning to people’s lives. To live the life of the absurd means rejecting a life that finds or pursues specific meaning for man’s existence since there is nothing to be discovered. According to Albert Camus, the world or the human being is not in itself absurd. The concept only emerges through the juxtaposition of the two; life becomes absurd due to the incompatibility between human beings and the world they inhabit.[32] This view constitutes one of the two interpretations of the absurd in existentialist literature. The second view, first elaborated by Søren Kierkegaard, holds that absurdity is limited to actions and choices of human beings. These are considered absurd since they issue from human freedom, undermining their foundation outside of themselves.[33]

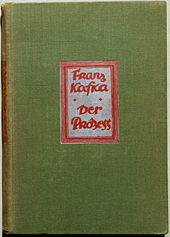

The absurd contrasts with the claim that «bad things don’t happen to good people»; to the world, metaphorically speaking, there is no such thing as a good person or a bad person; what happens happens, and it may just as well happen to a «good» person as to a «bad» person.[34] Because of the world’s absurdity, anything can happen to anyone at any time and a tragic event could plummet someone into direct confrontation with the absurd. Many of the literary works of Kierkegaard, Samuel Beckett, Franz Kafka, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Eugène Ionesco, Miguel de Unamuno, Luigi Pirandello,[35][36][37][38] Sartre, Joseph Heller, and Camus contain descriptions of people who encounter the absurdity of the world.

It is because of the devastating awareness of meaninglessness that Camus claimed in The Myth of Sisyphus that «There is only one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide.» Although «prescriptions» against the possible deleterious consequences of these kinds of encounters vary, from Kierkegaard’s religious «stage» to Camus’ insistence on persevering in spite of absurdity, the concern with helping people avoid living their lives in ways that put them in the perpetual danger of having everything meaningful break down is common to most existentialist philosophers. The possibility of having everything meaningful break down poses a threat of quietism, which is inherently against the existentialist philosophy.[39] It has been said that the possibility of suicide makes all humans existentialists. The ultimate hero of absurdism lives without meaning and faces suicide without succumbing to it.[40]

Facticity[edit]

Facticity is defined by Sartre in Being and Nothingness (1943) as the in-itself, which delineates for humans the modalities of being and not being. It is the facts of your personal life and as per Heidegger, it is «the way in which we are thrown into the world.» This can be more easily understood when considering facticity in relation to the temporal dimension of our past: one’s past is what one is, in that it co-constitutes oneself. However, to say that one is only one’s past would ignore a significant part of reality (the present and the future), while saying that one’s past is only what one was, would entirely detach it from oneself now. A denial of one’s concrete past constitutes an inauthentic lifestyle, and also applies to other kinds of facticity (having a human body—e.g., one that does not allow a person to run faster than the speed of sound—identity, values, etc.).[41]

Facticity is a limitation and a condition of freedom. It is a limitation in that a large part of one’s facticity consists of things one did not choose (birthplace, etc.), but a condition of freedom in the sense that one’s values most likely depend on it. However, even though one’s facticity is «set in stone» (as being past, for instance), it cannot determine a person: the value ascribed to one’s facticity is still ascribed to it freely by that person. As an example, consider two men, one of whom has no memory of his past and the other who remembers everything. Both have committed many crimes, but the first man, remembering nothing, leads a rather normal life while the second man, feeling trapped by his own past, continues a life of crime, blaming his own past for «trapping» him in this life. There is nothing essential about his committing crimes, but he ascribes this meaning to his past.

However, to disregard one’s facticity during the continual process of self-making, projecting oneself into the future, would be to put oneself in denial of oneself and would be inauthentic. The origin of one’s projection must still be one’s facticity, though in the mode of not being it (essentially). An example of one focusing solely on possible projects without reflecting on one’s current facticity:[41] would be someone who continually thinks about future possibilities related to being rich (e.g. a better car, bigger house, better quality of life, etc.) without acknowledging the facticity of not currently having the financial means to do so. In this example, considering both facticity and transcendence, an authentic mode of being would be considering future projects that might improve one’s current finances (e.g. putting in extra hours, or investing savings) in order to arrive at a future-facticity of a modest pay rise, further leading to purchase of an affordable car.

Another aspect of facticity is that it entails angst. Freedom «produces» angst when limited by facticity and the lack of the possibility of having facticity to «step in» and take responsibility for something one has done also produces angst.

Another aspect of existential freedom is that one can change one’s values. One is responsible for one’s values, regardless of society’s values. The focus on freedom in existentialism is related to the limits of responsibility one bears, as a result of one’s freedom. The relationship between freedom and responsibility is one of interdependency and a clarification of freedom also clarifies that for which one is responsible.[42][43]

Authenticity[edit]

Many noted existentialists consider the theme of authentic existence important. Authenticity involves the idea that one has to «create oneself» and live in accordance with this self. For an authentic existence, one should act as oneself, not as «one’s acts» or as «one’s genes» or as any other essence requires. The authentic act is one in accordance with one’s freedom. A component of freedom is facticity, but not to the degree that this facticity determines one’s transcendent choices (one could then blame one’s background for making the choice one made [chosen project, from one’s transcendence]). Facticity, in relation to authenticity, involves acting on one’s actual values when making a choice (instead of, like Kierkegaard’s Aesthete, «choosing» randomly), so that one takes responsibility for the act instead of choosing either-or without allowing the options to have different values.[44]

In contrast, the inauthentic is the denial to live in accordance with one’s freedom. This can take many forms, from pretending choices are meaningless or random, convincing oneself that some form of determinism is true, or «mimicry» where one acts as «one should».[citation needed]

How one «should» act is often determined by an image one has, of how one in such a role (bank manager, lion tamer, prostitute, etc.) acts. In Being and Nothingness, Sartre uses the example of a waiter in «bad faith». He merely takes part in the «act» of being a typical waiter, albeit very convincingly.[45] This image usually corresponds to a social norm, but this does not mean that all acting in accordance with social norms is inauthentic. The main point is the attitude one takes to one’s own freedom and responsibility and the extent to which one acts in accordance with this freedom.[46]

The Other and the Look[edit]

The Other (written with a capital «O») is a concept more properly belonging to phenomenology and its account of intersubjectivity. However, it has seen widespread use in existentialist writings, and the conclusions drawn differ slightly from the phenomenological accounts. The Other is the experience of another free subject who inhabits the same world as a person does. In its most basic form, it is this experience of the Other that constitutes intersubjectivity and objectivity. To clarify, when one experiences someone else, and this Other person experiences the world (the same world that a person experiences)—only from «over there»—the world is constituted as objective in that it is something that is «there» as identical for both of the subjects; a person experiences the other person as experiencing the same things. This experience of the Other’s look is what is termed the Look (sometimes the Gaze).[47]

While this experience, in its basic phenomenological sense, constitutes the world as objective and oneself as objectively existing subjectivity (one experiences oneself as seen in the Other’s Look in precisely the same way that one experiences the Other as seen by him, as subjectivity), in existentialism, it also acts as a kind of limitation of freedom. This is because the Look tends to objectify what it sees. When one experiences oneself in the Look, one does not experience oneself as nothing (no thing), but as something (some thing). In Sartre’s example of a man peeping at someone through a keyhole, the man is entirely caught up in the situation he is in. He is in a pre-reflexive state where his entire consciousness is directed at what goes on in the room. Suddenly, he hears a creaking floorboard behind him and he becomes aware of himself as seen by the Other. He is then filled with shame for he perceives himself as he would perceive someone else doing what he was doing—as a Peeping Tom. For Sartre, this phenomenological experience of shame establishes proof for the existence of other minds and defeats the problem of solipsism. For the conscious state of shame to be experienced, one has to become aware of oneself as an object of another look, proving a priori, that other minds exist.[48] The Look is then co-constitutive of one’s facticity.

Another characteristic feature of the Look is that no Other really needs to have been there: It is possible that the creaking floorboard was simply the movement of an old house; the Look is not some kind of mystical telepathic experience of the actual way the Other sees one (there may have been someone there, but he could have not noticed that person). It is only one’s perception of the way another might perceive him.[citation needed]

Angst and dread[edit]

«Existential angst», sometimes called existential dread, anxiety, or anguish, is a term common to many existentialist thinkers.[49] It is generally held to be a negative feeling arising from the experience of human freedom and responsibility. The archetypal example is the experience one has when standing on a cliff where one not only fears falling off it, but also dreads the possibility of throwing oneself off. In this experience that «nothing is holding me back», one senses the lack of anything that predetermines one to either throw oneself off or to stand still, and one experiences one’s own freedom.

It can also be seen in relation to the previous point how angst is before nothing, and this is what sets it apart from fear that has an object. While one can take measures to remove an object of fear, for angst no such «constructive» measures are possible. The use of the word «nothing» in this context relates to the inherent insecurity about the consequences of one’s actions and to the fact that, in experiencing freedom as angst, one also realizes that one is fully responsible for these consequences. There is nothing in people (genetically, for instance) that acts in their stead—that they can blame if something goes wrong. Therefore, not every choice is perceived as having dreadful possible consequences (and, it can be claimed, human lives would be unbearable if every choice facilitated dread). However, this does not change the fact that freedom remains a condition of every action.

Despair[edit]

Despair is generally defined as a loss of hope.[50] In existentialism, it is more specifically a loss of hope in reaction to a breakdown in one or more of the defining qualities of one’s self or identity. If a person is invested in being a particular thing, such as a bus driver or an upstanding citizen, and then finds their being-thing compromised, they would normally be found in a state of despair—a hopeless state. For example, a singer who loses the ability to sing may despair if they have nothing else to fall back on—nothing to rely on for their identity. They find themselves unable to be what defined their being.

What sets the existentialist notion of despair apart from the conventional definition is that existentialist despair is a state one is in even when they are not overtly in despair. So long as a person’s identity depends on qualities that can crumble, they are in perpetual despair—and as there is, in Sartrean terms, no human essence found in conventional reality on which to constitute the individual’s sense of identity, despair is a universal human condition. As Kierkegaard defines it in Either/Or: «Let each one learn what he can; both of us can learn that a person’s unhappiness never lies in his lack of control over external conditions, since this would only make him completely unhappy.»[51] In Works of Love, he says:

When the God-forsaken worldliness of earthly life shuts itself in complacency, the confined air develops poison, the moment gets stuck and stands still, the prospect is lost, a need is felt for a refreshing, enlivening breeze to cleanse the air and dispel the poisonous vapors lest we suffocate in worldliness. … Lovingly to hope all things is the opposite of despairingly to hope nothing at all. Love hopes all things—yet is never put to shame. To relate oneself expectantly to the possibility of the good is to hope. To relate oneself expectantly to the possibility of evil is to fear. By the decision to choose hope one decides infinitely more than it seems, because it is an eternal decision.

— Søren Kierkegaard, Works of Love

Opposition to positivism and rationalism[edit]

Existentialists oppose defining human beings as primarily rational, and, therefore, oppose both positivism and rationalism. Existentialism asserts that people make decisions based on subjective meaning rather than pure rationality.

The rejection of reason as the source of meaning is a common theme of existentialist thought, as is the focus on the anxiety and dread that we feel in the face of our own radical free will and our awareness of death. Kierkegaard advocated rationality as a means to interact with the objective world (e.g., in the natural sciences), but when it comes to existential problems, reason is insufficient: «Human reason has boundaries».[52]

Like Kierkegaard, Sartre saw problems with rationality, calling it a form of «bad faith», an attempt by the self to impose structure on a world of phenomena—»the Other»—that is fundamentally irrational and random. According to Sartre, rationality and other forms of bad faith hinder people from finding meaning in freedom. To try to suppress feelings of anxiety and dread, people confine themselves within everyday experience, Sartre asserted, thereby relinquishing their freedom and acquiescing to being possessed in one form or another by «the Look» of «the Other» (i.e., possessed by another person—or at least one’s idea of that other person).[53]

Religion[edit]

An existentialist reading of the Bible would demand that the reader recognize that they are an existing subject studying the words more as a recollection of events. This is in contrast to looking at a collection of «truths» that are outside and unrelated to the reader, but may develop a sense of reality/God. Such a reader is not obligated to follow the commandments as if an external agent is forcing these commandments upon them, but as though they are inside them and guiding them from inside. This is the task Kierkegaard takes up when he asks: «Who has the more difficult task: the teacher who lectures on earnest things a meteor’s distance from everyday life—or the learner who should put it to use?»[54]

Confusion with nihilism[edit]

Although nihilism and existentialism are distinct philosophies, they are often confused with one another since both are rooted in the human experience of anguish and confusion that stems from the apparent meaninglessness of a world in which humans are compelled to find or create meaning.[55] A primary cause of confusion is that Friedrich Nietzsche was an important philosopher in both fields.

Existentialist philosophers often stress the importance of angst as signifying the absolute lack of any objective ground for action, a move that is often reduced to moral or existential nihilism. A pervasive theme in existentialist philosophy, however, is to persist through encounters with the absurd, as seen in Camus’s The Myth of Sisyphus («One must imagine Sisyphus happy.»)[56] and it is only very rarely that existentialist philosophers dismiss morality or one’s self-created meaning: Kierkegaard regained a sort of morality in the religious (although he would not agree that it was ethical; the religious suspends the ethical), and Sartre’s final words in Being and Nothingness are: «All these questions, which refer us to a pure and not an accessory (or impure) reflection, can find their reply only on the ethical plane. We shall devote to them a future work.»[45]

History[edit]

Precursors[edit]

Some have argued that existentialism has long been an element of European religious thought, even before the term came into use. William Barrett identified Blaise Pascal and Søren Kierkegaard as two specific examples.[57] Jean Wahl also identified William Shakespeare’s Prince Hamlet («To be, or not to be»), Jules Lequier, Thomas Carlyle and William James as existentialists. According to Wahl, «the origins of most great philosophies, like those of Plato, Descartes, and Kant, are to be found in existential reflections.»[58] Precursors to Existentialism can also be identified in the works of Iranian Islamic philosopher Mulla Sadra (c. 1571 — 1635) who would posit that «existence precedes essence» becoming the principle expositor of the School of Isfahan which is described as ‘alive and active’. Proponents of Existential Thomism would also claim patrimony to Thomas Aquinas and Domingo Banez who Etienne Gilson would describe as one of the few Scholastics who grasped Aquinas’ own position in regards to existence.

19th century[edit]

Kierkegaard and Nietzsche[edit]

Kierkegaard is generally considered to have been the first existentialist philosopher.[6][59][60] He proposed that each individual—not reason, society, or religious orthodoxy—is solely tasked with giving meaning to life and living it sincerely, or «authentically».[61][62]

Kierkegaard and Nietzsche were two of the first philosophers considered fundamental to the existentialist movement, though neither used the term «existentialism» and it is unclear whether they would have supported the existentialism of the 20th century. They focused on subjective human experience rather than the objective truths of mathematics and science, which they believed were too detached or observational to truly get at the human experience. Like Pascal, they were interested in people’s quiet struggle with the apparent meaninglessness of life and the use of diversion to escape from boredom. Unlike Pascal, Kierkegaard and Nietzsche also considered the role of making free choices, particularly regarding fundamental values and beliefs, and how such choices change the nature and identity of the chooser.[63] Kierkegaard’s knight of faith and Nietzsche’s Übermensch are representative of people who exhibit freedom, in that they define the nature of their own existence. Nietzsche’s idealized individual invents his own values and creates the very terms they excel under. By contrast, Kierkegaard, opposed to the level of abstraction in Hegel, and not nearly as hostile (actually welcoming) to Christianity as Nietzsche, argues through a pseudonym that the objective certainty of religious truths (specifically Christian) is not only impossible, but even founded on logical paradoxes. Yet he continues to imply that a leap of faith is a possible means for an individual to reach a higher stage of existence that transcends and contains both an aesthetic and ethical value of life. Kierkegaard and Nietzsche were also precursors to other intellectual movements, including postmodernism, and various strands of psychotherapy.[citation needed] However, Kierkegaard believed that individuals should live in accordance with their thinking.[64]

Dostoevsky[edit]

The first important literary author also important to existentialism was the Russian, Dostoevsky.[65] Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground portrays a man unable to fit into society and unhappy with the identities he creates for himself. Sartre, in his book on existentialism Existentialism is a Humanism, quoted Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov as an example of existential crisis. Other Dostoyevsky novels covered issues raised in existentialist philosophy while presenting story lines divergent from secular existentialism: for example, in Crime and Punishment, the protagonist Raskolnikov experiences an existential crisis and then moves toward a Christian Orthodox worldview similar to that advocated by Dostoyevsky himself.[66]

Early 20th century[edit]

In the first decades of the 20th century, a number of philosophers and writers explored existentialist ideas. The Spanish philosopher Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo, in his 1913 book The Tragic Sense of Life in Men and Nations, emphasized the life of «flesh and bone» as opposed to that of abstract rationalism. Unamuno rejected systematic philosophy in favor of the individual’s quest for faith. He retained a sense of the tragic, even absurd nature of the quest, symbolized by his enduring interest in the eponymous character from the Miguel de Cervantes novel Don Quixote. A novelist, poet and dramatist as well as philosophy professor at the University of Salamanca, Unamuno wrote a short story about a priest’s crisis of faith, Saint Manuel the Good, Martyr, which has been collected in anthologies of existentialist fiction. Another Spanish thinker, José Ortega y Gasset, writing in 1914, held that human existence must always be defined as the individual person combined with the concrete circumstances of his life: «Yo soy yo y mi circunstancia» («I am myself and my circumstances»). Sartre likewise believed that human existence is not an abstract matter, but is always situated («en situation«).[citation needed]

Although Martin Buber wrote his major philosophical works in German, and studied and taught at the Universities of Berlin and Frankfurt, he stands apart from the mainstream of German philosophy. Born into a Jewish family in Vienna in 1878, he was also a scholar of Jewish culture and involved at various times in Zionism and Hasidism. In 1938, he moved permanently to Jerusalem. His best-known philosophical work was the short book I and Thou, published in 1922.[67] For Buber, the fundamental fact of human existence, too readily overlooked by scientific rationalism and abstract philosophical thought, is «man with man», a dialogue that takes place in the so-called «sphere of between» («das Zwischenmenschliche»).[68]

Two Russian philosophers, Lev Shestov and Nikolai Berdyaev, became well known as existentialist thinkers during their post-Revolutionary exiles in Paris. Shestov had launched an attack on rationalism and systematization in philosophy as early as 1905 in his book of aphorisms All Things Are Possible. Berdyaev drew a radical distinction between the world of spirit and the everyday world of objects. Human freedom, for Berdyaev, is rooted in the realm of spirit, a realm independent of scientific notions of causation. To the extent the individual human being lives in the objective world, he is estranged from authentic spiritual freedom. «Man» is not to be interpreted naturalistically, but as a being created in God’s image, an originator of free, creative acts.[69] He published a major work on these themes, The Destiny of Man, in 1931.

Gabriel Marcel, long before coining the term «existentialism», introduced important existentialist themes to a French audience in his early essay «Existence and Objectivity» (1925) and in his Metaphysical Journal (1927).[70] A dramatist as well as a philosopher, Marcel found his philosophical starting point in a condition of metaphysical alienation: the human individual searching for harmony in a transient life. Harmony, for Marcel, was to be sought through «secondary reflection», a «dialogical» rather than «dialectical» approach to the world, characterized by «wonder and astonishment» and open to the «presence» of other people and of God rather than merely to «information» about them. For Marcel, such presence implied more than simply being there (as one thing might be in the presence of another thing); it connoted «extravagant» availability, and the willingness to put oneself at the disposal of the other.[71]

Marcel contrasted secondary reflection with abstract, scientific-technical primary reflection, which he associated with the activity of the abstract Cartesian ego. For Marcel, philosophy was a concrete activity undertaken by a sensing, feeling human being incarnate—embodied—in a concrete world.[70][72] Although Sartre adopted the term «existentialism» for his own philosophy in the 1940s, Marcel’s thought has been described as «almost diametrically opposed» to that of Sartre.[70] Unlike Sartre, Marcel was a Christian, and became a Catholic convert in 1929.

In Germany, the psychologist and philosopher Karl Jaspers—who later described existentialism as a «phantom» created by the public[73]—called his own thought, heavily influenced by Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, Existenzphilosophie. For Jaspers, «Existenz-philosophy is the way of thought by means of which man seeks to become himself…This way of thought does not cognize objects, but elucidates and makes actual the being of the thinker».[74]

Jaspers, a professor at the university of Heidelberg, was acquainted with Heidegger, who held a professorship at Marburg before acceding to Husserl’s chair at Freiburg in 1928. They held many philosophical discussions, but later became estranged over Heidegger’s support of National Socialism. They shared an admiration for Kierkegaard,[75] and in the 1930s, Heidegger lectured extensively on Nietzsche. Nevertheless, the extent to which Heidegger should be considered an existentialist is debatable. In Being and Time he presented a method of rooting philosophical explanations in human existence (Dasein) to be analysed in terms of existential categories (existentiale); and this has led many commentators to treat him as an important figure in the existentialist movement.

After the Second World War[edit]

Following the Second World War, existentialism became a well-known and significant philosophical and cultural movement, mainly through the public prominence of two French writers, Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, who wrote best-selling novels, plays and widely read journalism as well as theoretical texts.[76] These years also saw the growing reputation of Being and Time outside Germany.

Sartre dealt with existentialist themes in his 1938 novel Nausea and the short stories in his 1939 collection The Wall, and had published his treatise on existentialism, Being and Nothingness, in 1943, but it was in the two years following the liberation of Paris from the German occupying forces that he and his close associates—Camus, Simone de Beauvoir, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and others—became internationally famous as the leading figures of a movement known as existentialism.[77] In a very short period of time, Camus and Sartre in particular became the leading public intellectuals of post-war France, achieving by the end of 1945 «a fame that reached across all audiences.»[78] Camus was an editor of the most popular leftist (former French Resistance) newspaper Combat; Sartre launched his journal of leftist thought, Les Temps Modernes, and two weeks later gave the widely reported lecture on existentialism and secular humanism to a packed meeting of the Club Maintenant. Beauvoir wrote that «not a week passed without the newspapers discussing us»;[79] existentialism became «the first media craze of the postwar era.»[80]

By the end of 1947, Camus’ earlier fiction and plays had been reprinted, his new play Caligula had been performed and his novel The Plague published; the first two novels of Sartre’s The Roads to Freedom trilogy had appeared, as had Beauvoir’s novel The Blood of Others. Works by Camus and Sartre were already appearing in foreign editions. The Paris-based existentialists had become famous.[77]

Sartre had traveled to Germany in 1930 to study the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger,[81] and he included critical comments on their work in his major treatise Being and Nothingness. Heidegger’s thought had also become known in French philosophical circles through its use by Alexandre Kojève in explicating Hegel in a series of lectures given in Paris in the 1930s.[82] The lectures were highly influential; members of the audience included not only Sartre and Merleau-Ponty, but Raymond Queneau, Georges Bataille, Louis Althusser, André Breton, and Jacques Lacan.[83] A selection from Being and Time was published in French in 1938, and his essays began to appear in French philosophy journals.

Heidegger read Sartre’s work and was initially impressed, commenting: «Here for the first time I encountered an independent thinker who, from the foundations up, has experienced the area out of which I think. Your work shows such an immediate comprehension of my philosophy as I have never before encountered.»[84] Later, however, in response to a question posed by his French follower Jean Beaufret,[85] Heidegger distanced himself from Sartre’s position and existentialism in general in his Letter on Humanism.[86] Heidegger’s reputation continued to grow in France during the 1950s and 1960s. In the 1960s, Sartre attempted to reconcile existentialism and Marxism in his work Critique of Dialectical Reason. A major theme throughout his writings was freedom and responsibility.

Camus was a friend of Sartre, until their falling-out, and wrote several works with existential themes including The Rebel, Summer in Algiers, The Myth of Sisyphus, and The Stranger, the latter being «considered—to what would have been Camus’s irritation—the exemplary existentialist novel.»[87] Camus, like many others, rejected the existentialist label, and considered his works concerned with facing the absurd. In the titular book, Camus uses the analogy of the Greek myth of Sisyphus to demonstrate the futility of existence. In the myth, Sisyphus is condemned for eternity to roll a rock up a hill, but when he reaches the summit, the rock will roll to the bottom again. Camus believes that this existence is pointless but that Sisyphus ultimately finds meaning and purpose in his task, simply by continually applying himself to it. The first half of the book contains an extended rebuttal of what Camus took to be existentialist philosophy in the works of Kierkegaard, Shestov, Heidegger, and Jaspers.

Simone de Beauvoir, an important existentialist who spent much of her life as Sartre’s partner, wrote about feminist and existentialist ethics in her works, including The Second Sex and The Ethics of Ambiguity. Although often overlooked due to her relationship with Sartre,[88] de Beauvoir integrated existentialism with other forms of thinking such as feminism, unheard of at the time, resulting in alienation from fellow writers such as Camus.[66]

Paul Tillich, an important existentialist theologian following Kierkegaard and Karl Barth, applied existentialist concepts to Christian theology, and helped introduce existential theology to the general public. His seminal work The Courage to Be follows Kierkegaard’s analysis of anxiety and life’s absurdity, but puts forward the thesis that modern humans must, via God, achieve selfhood in spite of life’s absurdity. Rudolf Bultmann used Kierkegaard’s and Heidegger’s philosophy of existence to demythologize Christianity by interpreting Christian mythical concepts into existentialist concepts.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, an existential phenomenologist, was for a time a companion of Sartre. Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception (1945) was recognized as a major statement of French existentialism.[89] It has been said that Merleau-Ponty’s work Humanism and Terror greatly influenced Sartre. However, in later years they were to disagree irreparably, dividing many existentialists such as de Beauvoir,[66] who sided with Sartre.

Colin Wilson, an English writer, published his study The Outsider in 1956, initially to critical acclaim. In this book and others (e.g. Introduction to the New Existentialism), he attempted to reinvigorate what he perceived as a pessimistic philosophy and bring it to a wider audience. He was not, however, academically trained, and his work was attacked by professional philosophers for lack of rigor and critical standards.[90]

Influence outside philosophy[edit]

Art[edit]

Film and television[edit]

Stanley Kubrick’s 1957 anti-war film Paths of Glory «illustrates, and even illuminates…existentialism» by examining the «necessary absurdity of the human condition» and the «horror of war».[91] The film tells the story of a fictional World War I French army regiment ordered to attack an impregnable German stronghold; when the attack fails, three soldiers are chosen at random, court-martialed by a «kangaroo court», and executed by firing squad. The film examines existentialist ethics, such as the issue of whether objectivity is possible and the «problem of authenticity».[91] Orson Welles’s 1962 film The Trial, based upon Franz Kafka’s book of the same name (Der Prozeß), is characteristic of both existentialist and absurdist themes in its depiction of a man (Joseph K.) arrested for a crime for which the charges are neither revealed to him nor to the reader.

Neon Genesis Evangelion is a Japanese science fiction animation series created by the anime studio Gainax and was both directed and written by Hideaki Anno. Existential themes of individuality, consciousness, freedom, choice, and responsibility are heavily relied upon throughout the entire series, particularly through the philosophies of Jean-Paul Sartre and Søren Kierkegaard. Episode 16’s title, «The Sickness Unto Death, And…» (死に至る病、そして, Shi ni itaru yamai, soshite) is a reference to Kierkegaard’s book, The Sickness Unto Death.

Some contemporary films dealing with existentialist issues include Melancholia, Fight Club, I Heart Huckabees, Waking Life, The Matrix, Ordinary People, Life in a Day, and Everything Everywhere All at Once.[92] Likewise, films throughout the 20th century such as The Seventh Seal, Ikiru, Taxi Driver, the Toy Story films, The Great Silence, Ghost in the Shell, Harold and Maude, High Noon, Easy Rider, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, A Clockwork Orange, Groundhog Day, Apocalypse Now, Badlands, and Blade Runner also have existentialist qualities.[93]

Notable directors known for their existentialist films include Ingmar Bergman, François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Michelangelo Antonioni, Akira Kurosawa, Terrence Malick, Stanley Kubrick, Andrei Tarkovsky, Hideaki Anno, Wes Anderson, Gaspar Noé, Woody Allen, and Christopher Nolan.[94] Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York focuses on the protagonist’s desire to find existential meaning.[95] Similarly, in Kurosawa’s Red Beard, the protagonist’s experiences as an intern in a rural health clinic in Japan lead him to an existential crisis whereby he questions his reason for being. This, in turn, leads him to a better understanding of humanity. The French film, Mood Indigo (directed by Michel Gondry) embraced various elements of existentialism.[citation needed] The film The Shawshank Redemption, released in 1994, depicts life in a prison in Maine, United States to explore several existentialist concepts.[96]

Literature[edit]

Existential perspectives are also found in modern literature to varying degrees, especially since the 1920s. Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night (Voyage au bout de la nuit, 1932) celebrated by both Sartre and Beauvoir, contained many of the themes that would be found in later existential literature, and is in some ways, the proto-existential novel. Jean-Paul Sartre’s 1938 novel Nausea[97] was «steeped in Existential ideas», and is considered an accessible way of grasping his philosophical stance.[98] Between 1900 and 1960, other authors such as Albert Camus, Franz Kafka, Rainer Maria Rilke, T. S. Eliot, Hermann Hesse, Luigi Pirandello,[35][36][38][99][100][101] Ralph Ellison,[102][103][104][105] and Jack Kerouac composed literature or poetry that contained, to varying degrees, elements of existential or proto-existential thought. The philosophy’s influence even reached pulp literature shortly after the turn of the 20th century, as seen in the existential disparity witnessed in Man’s lack of control of his fate in the works of H. P. Lovecraft.[106]

Theatre[edit]

Sartre wrote No Exit in 1944, an existentialist play originally published in French as Huis Clos (meaning In Camera or «behind closed doors»), which is the source of the popular quote, «Hell is other people.» (In French, «L’enfer, c’est les autres»). The play begins with a Valet leading a man into a room that the audience soon realizes is in hell. Eventually he is joined by two women. After their entry, the Valet leaves and the door is shut and locked. All three expect to be tortured, but no torturer arrives. Instead, they realize they are there to torture each other, which they do effectively by probing each other’s sins, desires, and unpleasant memories.

Existentialist themes are displayed in the Theatre of the Absurd, notably in Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, in which two men divert themselves while they wait expectantly for someone (or something) named Godot who never arrives. They claim Godot is an acquaintance, but in fact, hardly know him, admitting they would not recognize him if they saw him. Samuel Beckett, once asked who or what Godot is, replied, «If I knew, I would have said so in the play.» To occupy themselves, the men eat, sleep, talk, argue, sing, play games, exercise, swap hats, and contemplate suicide—anything «to hold the terrible silence at bay».[107] The play «exploits several archetypal forms and situations, all of which lend themselves to both comedy and pathos.»[108] The play also illustrates an attitude toward human experience on earth: the poignancy, oppression, camaraderie, hope, corruption, and bewilderment of human experience that can be reconciled only in the mind and art of the absurdist. The play examines questions such as death, the meaning of human existence and the place of God in human existence.

Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead is an absurdist tragicomedy first staged at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in 1966.[109] The play expands upon the exploits of two minor characters from Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Comparisons have also been drawn to Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, for the presence of two central characters who appear almost as two halves of a single character. Many plot features are similar as well: the characters pass time by playing Questions, impersonating other characters, and interrupting each other or remaining silent for long periods of time. The two characters are portrayed as two clowns or fools in a world beyond their understanding. They stumble through philosophical arguments while not realizing the implications, and muse on the irrationality and randomness of the world.

Jean Anouilh’s Antigone also presents arguments founded on existentialist ideas.[110] It is a tragedy inspired by Greek mythology and the play of the same name (Antigone, by Sophocles) from the fifth century BC. In English, it is often distinguished from its antecedent by being pronounced in its original French form, approximately «Ante-GŌN.» The play was first performed in Paris on 6 February 1944, during the Nazi occupation of France. Produced under Nazi censorship, the play is purposefully ambiguous with regards to the rejection of authority (represented by Antigone) and the acceptance of it (represented by Creon). The parallels to the French Resistance and the Nazi occupation have been drawn. Antigone rejects life as desperately meaningless but without affirmatively choosing a noble death. The crux of the play is the lengthy dialogue concerning the nature of power, fate, and choice, during which Antigone says that she is, «… disgusted with [the]…promise of a humdrum happiness.» She states that she would rather die than live a mediocre existence.

Critic Martin Esslin in his book Theatre of the Absurd pointed out how many contemporary playwrights such as Samuel Beckett, Eugène Ionesco, Jean Genet, and Arthur Adamov wove into their plays the existentialist belief that we are absurd beings loose in a universe empty of real meaning. Esslin noted that many of these playwrights demonstrated the philosophy better than did the plays by Sartre and Camus. Though most of such playwrights, subsequently labeled «Absurdist» (based on Esslin’s book), denied affiliations with existentialism and were often staunchly anti-philosophical (for example Ionesco often claimed he identified more with ‘Pataphysics or with Surrealism than with existentialism), the playwrights are often linked to existentialism based on Esslin’s observation.[111]

Psychoanalysis and psychotherapy[edit]

A major offshoot of existentialism as a philosophy is existentialist psychology and psychoanalysis, which first crystallized in the work of Otto Rank, Freud’s closest associate for 20 years. Without awareness of the writings of Rank, Ludwig Binswanger was influenced by Freud, Edmund Husserl, Heidegger, and Sartre. A later figure was Viktor Frankl, who briefly met Freud as a young man.[112] His logotherapy can be regarded as a form of existentialist therapy. The existentialists would also influence social psychology, antipositivist micro-sociology, symbolic interactionism, and post-structuralism, with the work of thinkers such as Georg Simmel[113] and Michel Foucault. Foucault was a great reader of Kierkegaard even though he almost never refers this author, who nonetheless had for him an importance as secret as it was decisive.[114]

An early contributor to existentialist psychology in the United States was Rollo May, who was strongly influenced by Kierkegaard and Otto Rank. One of the most prolific writers on techniques and theory of existentialist psychology in the US is Irvin D. Yalom. Yalom states that

Aside from their reaction against Freud’s mechanistic, deterministic model of the mind and their assumption of a phenomenological approach in therapy, the existentialist analysts have little in common and have never been regarded as a cohesive ideological school. These thinkers—who include Ludwig Binswanger, Medard Boss, Eugène Minkowski, V. E. Gebsattel, Roland Kuhn, G. Caruso, F. T. Buytendijk, G. Bally, and Victor Frankl—were almost entirely unknown to the American psychotherapeutic community until Rollo May’s highly influential 1958 book Existence—and especially his introductory essay—introduced their work into this country.[115]

A more recent contributor to the development of a European version of existentialist psychotherapy is the British-based Emmy van Deurzen.[citation needed]

Anxiety’s importance in existentialism makes it a popular topic in psychotherapy. Therapists often offer existentialist philosophy as an explanation for anxiety. The assertion is that anxiety is manifested of an individual’s complete freedom to decide, and complete responsibility for the outcome of such decisions. Psychotherapists using an existentialist approach believe that a patient can harness his anxiety and use it constructively. Instead of suppressing anxiety, patients are advised to use it as grounds for change. By embracing anxiety as inevitable, a person can use it to achieve his full potential in life. Humanistic psychology also had major impetus from existentialist psychology and shares many of the fundamental tenets. Terror management theory, based on the writings of Ernest Becker and Otto Rank, is a developing area of study within the academic study of psychology. It looks at what researchers claim are implicit emotional reactions of people confronted with the knowledge that they will eventually die.[116]

Also, Gerd B. Achenbach has refreshed the Socratic tradition with his own blend of philosophical counseling; as did Michel Weber with his Chromatiques Center in Belgium.[citation needed]

Criticisms[edit]

General criticisms[edit]

Walter Kaufmann criticized «the profoundly unsound methods and the dangerous contempt for reason that have been so prominent in existentialism.»[117] Logical positivist philosophers, such as Rudolf Carnap and A. J. Ayer, assert that existentialists are often confused about the verb «to be» in their analyses of «being.»[118] Specifically, they argue that the verb «is» is transitive and pre-fixed to a predicate (e.g., an apple is red) (without a predicate, the word «is» is meaningless), and that existentialists frequently misuse the term in this manner. Wilson has stated in his book The Angry Years that existentialism has created many of its own difficulties: «We can see how this question of freedom of the will has been vitiated by post-romantic philosophy, with its inbuilt tendency to laziness and boredom, we can also see how it came about that existentialism found itself in a hole of its own digging, and how the philosophical developments since then have amounted to walking in circles round that hole.»[119]

Sartre’s philosophy[edit]

Many critics argue Sartre’s philosophy is contradictory. Specifically, they argue that Sartre makes metaphysical arguments despite his claiming that his philosophical views ignore metaphysics. Herbert Marcuse criticized Being and Nothingness for projecting anxiety and meaninglessness onto the nature of existence itself: «Insofar as Existentialism is a philosophical doctrine, it remains an idealistic doctrine: it hypostatizes specific historical conditions of human existence into ontological and metaphysical characteristics. Existentialism thus becomes part of the very ideology which it attacks, and its radicalism is illusory.»[120]

In Letter on Humanism, Heidegger criticized Sartre’s existentialism:

Existentialism says existence precedes essence. In this statement he is taking existentia and essentia according to their metaphysical meaning, which, from Plato’s time on, has said that essentia precedes existentia. Sartre reverses this statement. But the reversal of a metaphysical statement remains a metaphysical statement. With it, he stays with metaphysics, in oblivion of the truth of Being.[121]

See also[edit]

- Abandonment (existentialism)

- Disenchantment

- Existential phenomenology

- Existential risk

- Existential therapy

- Existentiell

- List of existentialists

- Meaning (existential)

- Meaning-making

- Nihilism

- Philosophical pessimism

- Self

- Self-reflection

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ «existentialism». Lexico. Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ «existentialism». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2 March 2020. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Lavrin, Janko (1971). Nietzsche: A Biographical Introduction. Charles Scribner’s Sons. p. 43.

- ^ a b Macquarrie, John (1972). Existentialism. New York: Penguin. pp. 14–15.

- ^ Solomon, Robert C. (1974). Existentialism. McGraw-Hill. pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b c d e f Crowell, Steven (October 2010). «Existentialism». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Honderich, Ted, ed. (1995). Oxford Companion to Philosophy. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-19-866132-0.

- ^ Breisach, Ernst (1962). Introduction to Modern Existentialism. New York: Grove Press. p. 5.

- ^ Kaufmann, Walter (1956). Existentialism: From Dostoyevesky to Sartre. New York: Meridian. p. 12.

- ^ Flynn, Thomas (2006). Existentialism — A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press Inc. p. xi. ISBN 0-19-280428-6.

- ^ Guignon, Charles B.; Pereboom, Derk (2001). Existentialism: Basic Writings. Hackett Publishing. p. xiii. ISBN 9780872205956.

- ^ D.E. Cooper, Existentialism: A Reconstruction, Basil Blackwell, 1990, p. 1.

- ^ Thomas R. Flynn, Existentialism: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, 2006, p. 89.

- ^ Christine Daigle, Existentialist Thinkers and Ethics, McGill-Queen’s Press, 2006, p. 5.

- ^

Ann Fulton, Apostles of Sartre: Existentialism in America, 1945–1963, Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1999, p. 18–19. - ^ L’Existentialisme est un Humanisme (Editions Nagel, 1946); English Jean-Paul Sartre, Existentialism and Humanism (Eyre Methuen, 1948).

- ^ Crowell, Steven. The Cambridge Companion to Existentialism, Cambridge, 2011, p. 316.

- ^ Copleston, F. C. (2009). «Existentialism». Philosophy. 23 (84): 19–37. doi:10.1017/S0031819100065955. JSTOR 4544850. S2CID 241337492.

- ^ See James Wood’s introduction to Sartre, Jean-Paul (2000). Nausea. London: Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-141-18549-1. Quote on p. vii.

- ^ Abulof, Uriel. «Episode 1: The Jumping Off Place [MOOC lecture]». Uriel Abulof, Human Odyssey to Political Existentialism (HOPE). edX/Princeton. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ Klempe, Hroar (October 2008). «Welhaven og psykologien: Del 2. Welhaven peker fremover». Tidsskrift for Norsk Psykologforening (in Norwegian Bokmål). 45 (10). Retrieved 2022-07-14.

- ^ Lundestad, 1998, p. 169.

- ^ Slagstad, 2001, p. 89.

- ^ (Dictionary) «L’existencialisme» – see «l’identité de la personne» (in French).

- ^ «Aquinas: Metaphysics | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy». Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- ^ Baird, Forrest E.; Walter Kaufmann (2008). From Plato to Derrida. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-158591-1.

- ^ a b c Webber, Jonathan (2018). Rethinking Existentialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Burnham, Douglas. «Existentialism». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ Cox, Gary (2008). The Sartre Dictionary. Continuum. pp. 41–42.

- ^ Heidegger, Martin (1993). Basic Writings: From Being and Time (1927) to The Task of Thinking (1964). Edited by David Farrell Krell (Revised and expanded ed.). San Francisco, California: Harper San Francisco. ISBN 0060637633. OCLC 26355951.

- ^ Heidegger, Martin (1993). Basic Writings: From Being and Time (1927) to The Task of thinking (1964). Edited by David Farrell Krell (Revised and expanded ed.). San Francisco, California: Harper San Francisco. pp. 243. ISBN 0060637633. OCLC 26355951.

- ^ a b Wartenberg, Thomas (2009). Existentialism: A Beginner’s Guide. Oxford: One World. ISBN 9781780740201.