I am new to Python and try to install Jupyter Notebook from within a Windows command prompt window using:

pip install jupyter

But after a couple of minutes of downloading, an error message is displayed as shown below:

Installing build dependencies ... done

Getting requirements to build wheel ... done

Preparing wheel metadata ... error

ERROR: Command errored out with exit status 1:

command: 'c:usersasdappdatalocalprogramspythonpython38-32python.exe

' 'c:usersasdappdatalocalprogramspythonpython38-32libsite-packagespip

_vendorpep517_in_process.py' prepare_metadata_for_build_wheel 'C:UsersasdAp

pDataLocalTemptmpnj_hhq6y'

cwd: C:UsersasdAppDataLocalTemppip-install-_pnki5r8pywinpty

Complete output (6 lines):

Cargo, the Rust package manager, is not installed or is not on PATH.

This package requires Rust and Cargo to compile extensions. Install it through

the system's package manager or via https://rustup.rs/

Checking for Rust toolchain....

----------------------------------------

ERROR: Command errored out with exit status 1: 'c:usersasdappdatalocalprogr

amspythonpython38-32python.exe' 'c:usersasdappdatalocalprogramspythonp

ython38-32libsite-packagespip_vendorpep517_in_process.py' prepare_metadata

_for_build_wheel 'C:UsersasdAppDataLocalTemptmpnj_hhq6y' Check the logs for

full command output.

WARNING: You are using pip version 20.2.1; however, version 21.1 is available.

You should consider upgrading via the 'c:usersasdappdatalocalprogramspytho

npython38-32python.exe -m pip install --upgrade pip' command.

I have attached here just the last part of the error output.

How to fix this error for a successful installation of Jupyter Notebook?

EDIT1: I installed the Rust package from the link in the error message. After that I tried installing Jupyter Notebook once again, and this time after proceeding a few steps further than before, it output another error:

Building wheels for collected packages: pywinpty

Building wheel for pywinpty (PEP 517) ... - WARNING: Subprocess output does

not appear to be encoded as cp1252

WARNING: Subprocess output does not appear to be encoded as cp1252

error

ERROR: Command errored out with exit status 1:

command: 'c:usersasdappdatalocalprogramspythonpython38-32python.exe'

'c:usersasdappdatalocalprogramspythonpython38-32libsite-packagespip_v

endorpep517_in_process.py' build_wheel 'C:UsersasdAppDataLocalTemptmpaj5

u66_y'

cwd: C:UsersasdAppDataLocalTemppip-install-mep4ye8dpywinpty

Complete output (60 lines):

Running `maturin pep517 build-wheel -i c:usersasdappdatalocalprogramspyt

honpython38-32python.exe`

Compiling proc-macro2 v1.0.26

Compiling unicode-xid v0.2.2

Compiling syn v1.0.71

Compiling winapi v0.3.9

Compiling jobserver v0.1.22

error: could not compile `proc-macro2`

To learn more, run the command again with --verbose.

warning: build failed, waiting for other jobs to finish...

error: build failed

dY'¥ maturin failed

Caused by: Failed to build a native library through cargo

Caused by: Cargo build finished with "exit code: 101": `cargo rustc --messag

e-format json --manifest-path Cargo.toml --release --lib --`

dYx8d1 Building a mixed python/rust project

dY"- Found pyo3 bindings

dYx90x8d Found CPython 3.8 at c:usersasdappdatalocalprogramspythonpyt

hon38-32python.exe

error: linker `link.exe` not found

|

= note: The system cannot find the file specified. (os error 2)

note: the msvc targets depend on the msvc linker but `link.exe` was not found

note: please ensure that VS 2013, VS 2015, VS 2017 or VS 2019 was installed wi

th the Visual C++ option

error: aborting due to previous error

error: linker `link.exe` not found

|

= note: The system cannot find the file specified. (os error 2)

note: the msvc targets depend on the msvc linker but `link.exe` was not found

note: please ensure that VS 2013, VS 2015, VS 2017 or VS 2019 was installed wi

th the Visual C++ option

error: aborting due to previous error

error: linker `link.exe` not found

|

= note: The system cannot find the file specified. (os error 2)

note: the msvc targets depend on the msvc linker but `link.exe` was not found

note: please ensure that VS 2013, VS 2015, VS 2017 or VS 2019 was installed wi

th the Visual C++ option

error: aborting due to previous error

Error: command ['maturin', 'pep517', 'build-wheel', '-i', 'c:\users\asd\app

data\local\programs\python\python38-32\python.exe'] returned non-zero exit

status 1

----------------------------------------

ERROR: Failed building wheel for pywinpty

Failed to build pywinpty

ERROR: Could not build wheels for pywinpty which use PEP 517 and cannot be insta

lled directly

WARNING: You are using pip version 20.2.1; however, version 21.1 is available.

You should consider upgrading via the 'c:usersasdappdatalocalprogramspytho

npython38-32python.exe -m pip install --upgrade pip' command.

Содержание

- Installing Python Packages from a Jupyter Notebook

- Quick Fix: How To Install Packages from the Jupyter Notebook¶

- pip vs. conda¶

- How to use Conda from the Jupyter Notebook¶

- Основы работы в Jupyter/Jupiter Notebook и JupyterLab — Python Tutorial

- Что такое Jupyter Notebook (JupyterLab)?

- Установка/инсталляция Jupyter Notebook — pip3 install jupyter

- Install Jupyter Notebook на Ubuntu 20.14

- Install Jupyter Notebook на Windows

- Установка Jupyter Notebook в Docker через Docker-Compose

- Установка Jupyter Notebook через virtual env на Windows

- Установка Jupyter Notebook через virtual env на Ubuntu 20.14

- Как устроен Jupyter Notebook. Как работает Jupyter Notebook

- IPython Kernel (Ядро IPython)

- Terminal IPython

- IPython Kernel

- Jupyter Lab

- Ценность Jupyter Notebook/JupyterLab для аналитиков данных

- Установка JupyterLab на Ubuntu 20.14

- Установка JupyterLab на Windows

- В чем разница между Jupyter Notebook и JupyterLab?

- Основы работы и обзор функциональности Jupyter Notebook

- Из чего состоит Jupiter Notebook

- Магические функции Jupiter Notebook

- %timeit

- %matplotlib inline

- jupyter markdown

- jupyter server

- jupyter config

- jupyter hub

- jupyter команды

- pycharm jupyter

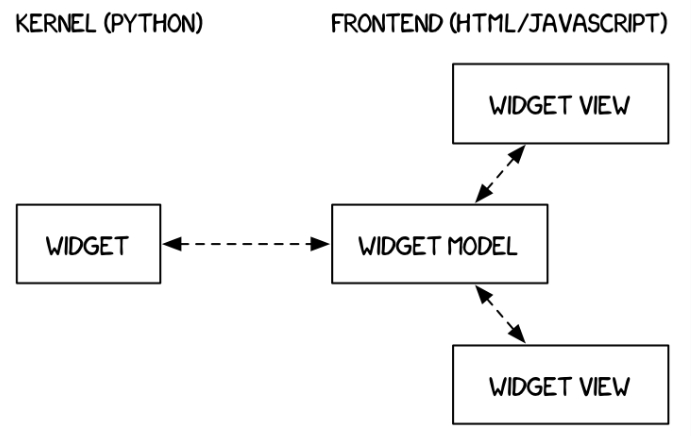

- Виджеты Jupyter

- Почему отображение одного и того же виджета дважды работает?

- Tips & Tricks / Советы, рекомендации и фишки при работе с Jupyter Notebook

- Подборка видео по Jupyter

- Как использовать Jupyter (ipython-notebook) на 100%

- Jupyter Notebook Tutorial (Eng)

- Jupyterlab — STOP Using Jupyter Notebook! Here’s the Better Tool

Installing Python Packages from a Jupyter Notebook

In software, it’s said that all abstractions are leaky, and this is true for the Jupyter notebook as it is for any other software. I most often see this manifest itself with the following issue:

I installed package X and now I can’t import it in the notebook. Help!

This issue is a perrennial source of StackOverflow questions (e.g. this, that, here, there, another, this one, that one, and this. etc.).

Fundamentally the problem is usually rooted in the fact that the Jupyter kernels are disconnected from Jupyter’s shell; in other words, the installer points to a different Python version than is being used in the notebook. In the simplest contexts this issue does not arise, but when it does, debugging the problem requires knowledge of the intricacies of the operating system, the intricacies of Python package installation, and the intricacies of Jupyter itself. In other words, the Jupyter notebook, like all abstractions, is leaky.

In the wake of several discussions on this topic with colleagues, some online (exhibit A, exhibit B) and some off, I decided to treat this issue in depth here. This post will address a couple things:

First, I’ll provide a quick, bare-bones answer to the general question, how can I install a Python package so it works with my jupyter notebook, using pip and/or conda?.

Second, I’ll dive into some of the background of exactly what the Jupyter notebook abstraction is doing, how it interacts with the complexities of the operating system, and how you can think about where the «leaks» are, and thus better understand what’s happening when things stop working.

Third, I’ll talk about some ideas the community might consider to help smooth-over these issues, including some changes that the Jupyter, Pip, and Conda developers might consider to ease the cognitive load on users.

This post will focus on two approaches to installing Python packages: pip and conda. Other package managers exist (including platform-specific tools like yum, apt, homebrew, etc., as well as cross-platform tools like enstaller), but I’m less familiar with them and won’t be remarking on them further.

Quick Fix: How To Install Packages from the Jupyter Notebook¶

If you’re just looking for a quick answer to the question, how do I install packages so they work with the notebook, then look no further.

pip vs. conda¶

First, a few words on pip vs. conda . For many users, the choice between pip and conda can be a confusing one. I wrote way more than you ever want to know about these in a post last year, but the essential difference between the two is this:

- pip installs python packages in any environment.

- conda installs any package in conda environments.

If you already have a Python installation that you’re using, then the choice of which to use is easy:

If you installed Python using Anaconda or Miniconda, then use conda to install Python packages. If conda tells you the package you want doesn’t exist, then use pip (or try conda-forge, which has more packages available than the default conda channel).

If you installed Python any other way (from source, using pyenv, virtualenv, etc.), then use pip to install Python packages

Finally, because it often comes up, I should mention that you should never use sudo pip install .

It will always lead to problems in the long term, even if it seems to solve them in the short-term. For example, if pip install gives you a permission error, it likely means you’re trying to install/update packages in a system python, such as /usr/bin/python . Doing this can have bad consequences, as often the operating system itself depends on particular versions of packages within that Python installation. For day-to-day Python usage, you should isolate your packages from the system Python, using either virtual environments or Anaconda/Miniconda — I personally prefer conda for this, but I know many colleagues who prefer virtualenv.

How to use Conda from the Jupyter Notebook¶

If you’re in the jupyter notebook and you want to install a package with conda, you might be tempted to use the ! notation to run conda directly as a shell command from the notebook:

Источник

Основы работы в Jupyter/Jupiter Notebook и JupyterLab — Python Tutorial

Что такое Jupyter Notebook (JupyterLab)?

Jupyter Notebook — это среда разработки для написания и выполнения кода Python. Некоммерческая организация Project Jupyter с открытым исходным кодом поддерживает программное обеспечение. Он состоит из последовательности ячеек, каждая из которых содержит небольшой пример кода или документацию в формате Markdown. Разработчики могут выполнить ячейку и увидеть ее вывод сразу под кодом. Гениальный дизайн создает мгновенную петлю обратной связи, позволяя программисту запускать свой код и вносить в него соответствующие изменения.

Ячейки Jupyter Notebook также поддерживают аннотации, аудиофайлы, видео, изображения, интерактивные диаграммы и многое другое. Это еще одно важное преимущество программного обеспечения; вы можете рассказать историю с вашим кодом. Читатели могут видеть шаги, которые вы выполнили, чтобы получить результат.

Вы можете импортировать пакеты Python, такие как pandas, NumPy или TensorFlow, прямо в Блокнот.

Jupyter Notebook – это веб-оболочка для Ipython (ранее называлась IPython Notebook). Это веб-приложение с открытым исходным кодом, которое позволяет создавать и обмениваться документами, содержащими живой код, уравнения, визуализацию и разметку.

Первоначально IPython Notebook ограничивался лишь Python в качестве единственного языка. Jupyter Notebook позволил использовать многие языки программирования, включая Python, R, Julia, Scala и F#.

Установка/инсталляция Jupyter Notebook — pip3 install jupyter

Install Jupyter Notebook на Ubuntu 20.14

Установка классического блокнота Jupyter без виртуальной среды осуществляется очень просто. Для этого необходимо запустить 2 команды:

После этого на вашей рабочей машине установится jupyter notebook. Теперь его необходимо запустить командой:

Откроется окно по адресу localhost:8888/

Install Jupyter Notebook на Windows

Аналогично без виртуальной среды блокнот Jupyter можно установить и на винду. Запускаем команду:

и после завершения установки запускаем команду:

Установка Jupyter Notebook в Docker через Docker-Compose

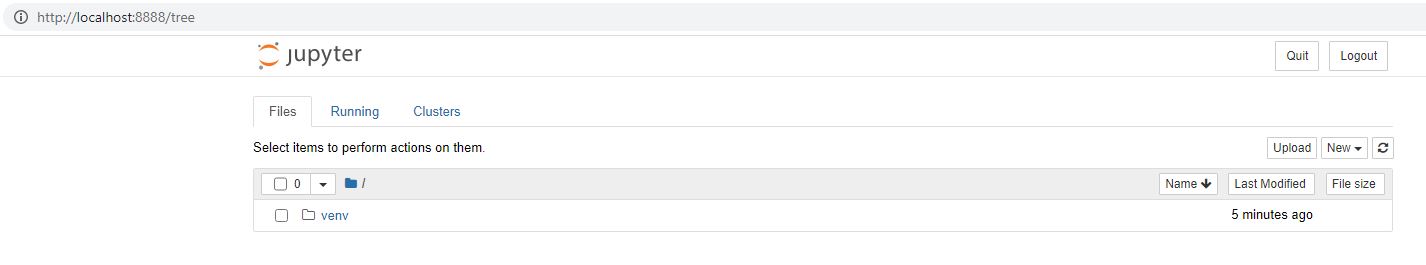

Установка Jupyter Notebook через virtual env на Windows

Создаем директорию проекта, например:

Далее в этой директории создаем виртуальную среду с помощью команды:

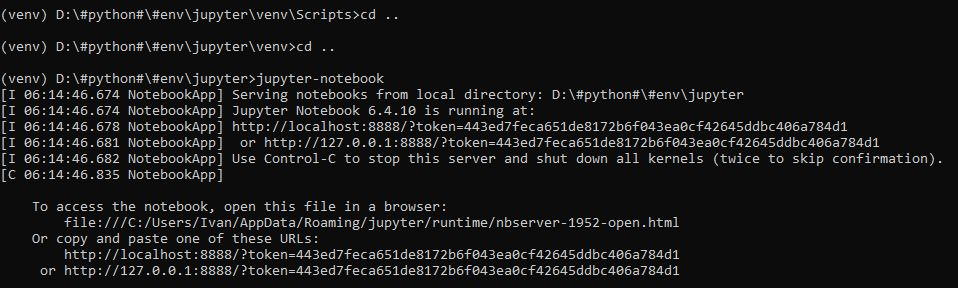

Далее переходим в директорию D:#python##envjupytervenvScripts и запускаем activate. Должна активироваться среда venv:

Далее запустите в активированной виртуальной среде venv установку jupyter notebook:

После завершения установки внутри venv нужно подняться в корень директории jupyter и запустить jupyter-notebook:

Выглядит это так:

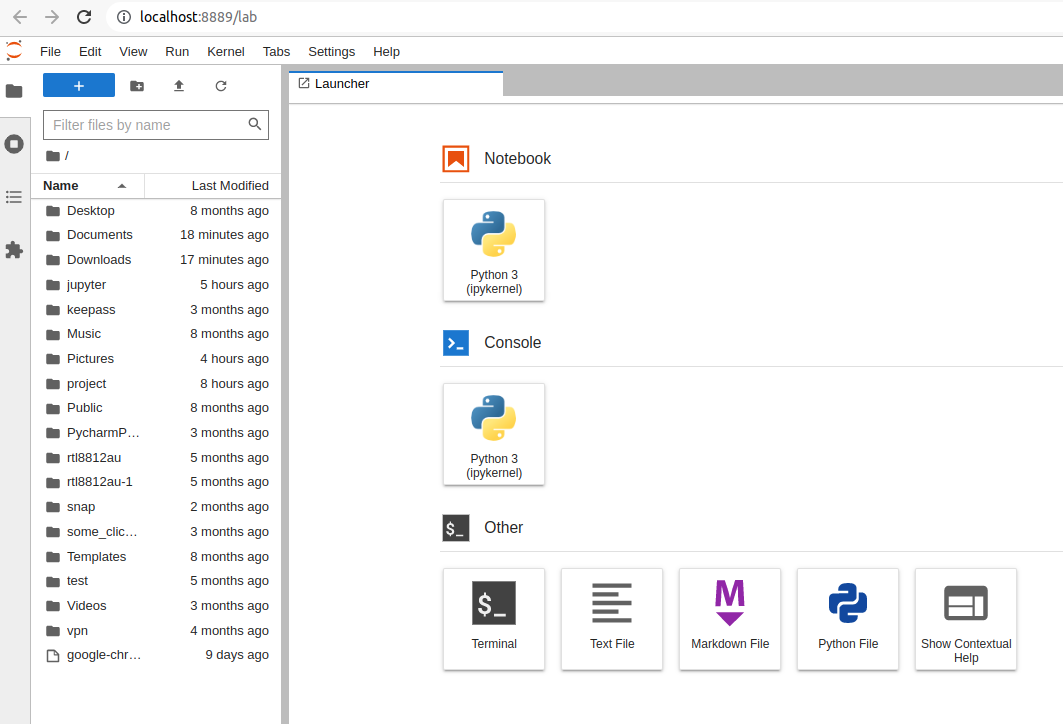

Откроется окно в браузере:

Установка Jupyter Notebook через virtual env на Ubuntu 20.14

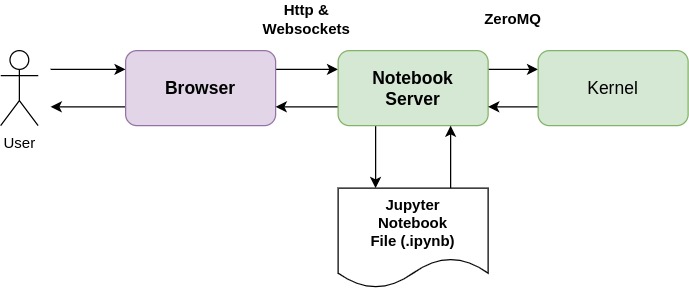

Как устроен Jupyter Notebook. Как работает Jupyter Notebook

Общий вид Jupyter Notebook

Если код пользователя должен быть выполнен, сервер ноутбука отправляет его ядру (kernel) в сообщениях ZeroMQ. Ядро возвращает результаты выполнения.

Затем сервер Notebook возвращает пользователю HTML-страницу. Когда пользователь сохраняет документ, он отправляется из браузера на сервер Notebook. Сервер сохраняет его на диске в виде файла JSON с .ipynb расширением. Этот файл блокнота содержит код, выходные данные и примечания в формате markdown.

Ядро (Kernel) ничего не знает о документе блокнота: оно просто получает отправленные ячейки кода для выполнения, когда пользователь запускает их.

Блокноты Jupyter — это структурированные данные, которые представляют ваш код, метаданные, контент и выходные данные.

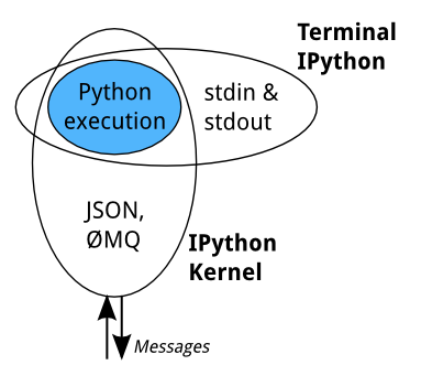

IPython Kernel (Ядро IPython)

Когда мы обсуждаем IPython, мы говорим о двух основных ролях:

- Terminal IPython как знакомый REPL.

- Ядро IPython, которое обеспечивает вычисления и связь с внешними интерфейсами, такими как ноутбук.

REPL – это форма организации простой интерактивной среды программирования в рамках средств интерфейса командной строки (REPL, от англ. Read-Eval-Print-Loop — цикл «чтение — вычисление — вывод»), которая поставляется вместе с Python. Чтобы запустить IPython, просто выполните команду ipython из командной строки/терминала.

Terminal IPython

Когда вы набираете ipython, вы получаете исходный интерфейс IPython, работающий в терминале. Он делает что-то вроде этого (упрощенная модель):

Эту модель часто называют REPL или Read-Eval-Print-Loop.

IPython Kernel

Все остальные интерфейсы — notebook, консоль Qt, ipython console в терминале и сторонние интерфейсы — используют Python Kernel.

Python Kernel — это отдельный процесс, который отвечает за выполнение пользовательского кода и такие вещи, как вычисление possible completions (возможных завершений). Внешние интерфейсы, такие как блокнот или консоль Qt, взаимодействуют с ядром IPython, используя сообщения JSON, отправляемые через сокеты ZeroMQ (протокол, используемый между интерфейсами и ядром IPython).

Основной механизм выполнения ядра используется совместно с терминалом IPython:

Jupyter Lab

Проект Jupyter приобрел большую популярность не только среди специалистов по данным, но и среди инженеров-программистов. На тот момент Jupyter Notebook был предназначен не только для работы с ноутбуком, поскольку он также поставлялся с веб-терминалом, текстовым редактором и файловым браузером. Все эти компоненты не были объединены вместе, и сообщество пользователей начало выражать потребность в более интегрированном опыте.

На конференции SciPy 2016 был анонсирован проект JupyterLab. Он был описан как естественная эволюция интерфейса Jupyter Notebook.

Кодовая база Notebook устарела, и ее становилось все труднее расширять. Стоимость поддержки старой кодовой базы и реализации новых функций поверх нее постоянно росла.

Разработчики учли весь опыт работы с Notebook в JupyterLab, чтобы создать надежную и чистую основу для гибкого интерактивного взаимодействия с компьютером и улучшенного пользовательского интерфейса.

Ценность Jupyter Notebook/JupyterLab для аналитиков данных

Разница между профессией data analyst/data scientist от разработки ПО заключается в отсутствии чёткого ТЗ на старте. Правильная постановка задачи в сфере анализа данных — это уже половина решения.

Первым этапом производится детальный анализ Initial Data (исходных данных) или Exploratory Data Analysis (Разведочный анализ данных), затем выдвигается одна или несколько гипотез. Эти шаги требуют значительных временных ресурсов.

Поэтому, понимание, как организовать процесс разработки (что нужно делать в первую очередь и чем можно будет пренебречь или исключить), начинает приходить во время разработки.

Исходя из этих соображений тратить силы на скурпулёзное и чистый код, git и т.д. бессмысленно — в первую очередь становится важным быстро создавать прототипы решений, ставить эксперименты над данными. Помимо этого, достигнутые результаты и обнаруженные инсайты или необычные наблюдения над данными приходится итерационно презентовать коллегам и заказчикам (внешним или внутренним). Jupyter Notebook или JupyterLab позволяет выполнять описанные задачи с помощью доступного функционала без дополнительных интеграций:

По факту, JupyterLab — это лабораторный журнал 21 века с элементами интерактивности, в котором вы можете оформить результаты работы с данными в формате markdown с использованием формул из latex. Также в JupyterLab можно писать и запускать код, вставлять в отчет картинки, отрисовывать графики, таблицы, дашборды.

Установка JupyterLab на Ubuntu 20.14

Установка производится одной командой

После инсталляции запустите команду

И откроется интерфейс:

Установка JupyterLab на Windows

Инсталляция и запуск на винде производится аналогично, как и на Ubuntu, командой pip instal jupyterlab .

В чем разница между Jupyter Notebook и JupyterLab?

Jupyter Notebook — это интерактивная вычислительная среда с веб-интерфейсом для создания документов Jupyter Notebook. Он поддерживает несколько языков, таких как Python (IPython), Julia, R и т.д., и в основном используется для анализа данных, визуализации данных и дальнейших интерактивных исследовательских вычислений.

JupyterLab — это пользовательский интерфейс нового поколения, включая ноутбуки. Он имеет модульную структуру, в которой вы можете открыть несколько записных книжек или файлов (например, HTML, Text, Markdowns и т.д.) в виде вкладок в одном окне. Он предлагает больше возможностей, подобных IDE.

Новичку я бы посоветовал начать с Jupyter Notebook, так как он состоит только из файлового браузера и представления редактора (Notebook). Это проще в использовании. Если вам нужны дополнительные функции, переключитесь на JupyterLab. JupyterLab предлагает гораздо больше функций и улучшенный интерфейс, который можно расширить с помощью расширений: JupyterLab Extensions.

Начиная с версии 3.0, JupyterLab также поставляется с визуальным отладчиком, который позволяет интерактивно устанавливать точки останова, переходить к функциям и проверять переменные.

JupyterLab — это совершенно фантастический инструмент как для создания plotly фигур, так и для запуска полных приложений Dash как встроенных, в виде вкладок, так и внешних в браузере.

Основы работы и обзор функциональности Jupyter Notebook

Из чего состоит Jupiter Notebook

Если щелкнуть по файлу с расширением .ipynb, откроется страница с Jupiter Notebook.

Отображаемый Notebook представляет собой HTML-документ, который был создан Jupyter и IPython. Он состоит из нескольких ячеек, которые могут быть одного из трех типов:

- Сode (активный программный код),

- Markdown (текст, поясняющий код, более развернутый, чем комментарий),

- Raw NBConvert (пассивный программный код).

Jupyter запускает ядро IPython для каждого Notebook.

Ячейки, содержащие код Python, выполняются внутри этого ядра и результаты добавляются в тетрадку в формате HTML.

Двойной щелчок по любой из этой ячеек позволит отредактировать ее. По завершении редактирования содержимого ячейки, нажмите Shift + Enter, после чего Jupyter/IPython проанализирует содержимое и отобразит результаты.

Если выполняемая ячейка является ячейкой кода, это приведет к выполнению кода в ячейке и отображению любого вывода непосредственно под ним. На это указывают слова «In» и «Out», расположенные слева от ячеек.

Магические функции Jupiter Notebook

Все magic-функции (их еще называют magic-командами ) начинаются

- со знака %, если функция применяется к одной строке,

- и %%, если применяется ко всей ячейке Jupyter.

Чтобы получить представление о времени, которое потребуется для выполнения функции, приведенной выше, мы воспользуемся функцией %timeit .

%timeit

%timeit – это magic-функция, созданная специально для работы с тетрадками Jupyter. Она является полезным инструментом, позволяющим сравнить время выполнения различных функций в одной и той же системе для одного и того же набора данных.

%matplotlib inline

%matplotlib inline позволяет выводит графики непосредственно в тетрадке.

На экранах с высоким разрешением типа Retina графики в тетрадках Jupiter по умолчанию выглядят размытыми, поэтому для улучшения резкости используйте

после %matplotlib inline .

jupyter markdown

jupyter server

jupyter config

jupyter hub

JupyterHub: позволяет предоставлять нескольким пользователям (группам сотрудников) доступ к Notebook и другим ресурсам. Это может быть полезно для студентов и компаний, которые хотят, чтобы группа (группы) имела доступ к вычислительной среде и ресурсам и использовала их без необходимости установки и настройки. Управление которыми могут осуществлять системные администраторы. Доступ к отдельным блокнотам и JupyterLab можно получить через Hub. Hub может работать в облаке или на собственном оборудовании группы.

jupyter команды

pycharm jupyter

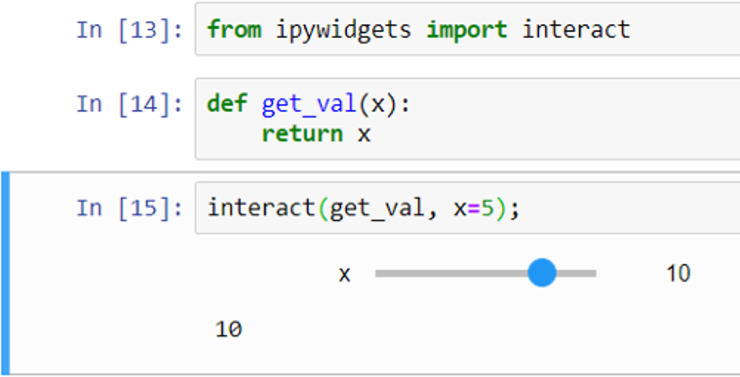

Виджеты Jupyter

Виджеты можно использовать для интерактивных элементов в блокнотах (например, ползунок).

Jupyter Widgets — это событийные объекты Python, которые имеют представление в браузере, часто в виде элемента управления, такого как ползунок, текстовое поле и т. д.

Почему отображение одного и того же виджета дважды работает?

Виджеты представлены в бэкенде одним объектом. Каждый раз, когда отображается виджет, во внешнем интерфейсе создается новое представление того же объекта. Эти представления называются представлениями.

Несколько самых популярных виджетов:

Чтобы начать использовать библиотеку, нам нужно установить расширение ipywidgets . Для pip это будет двухэтапный процесс:

Tips & Tricks / Советы, рекомендации и фишки при работе с Jupyter Notebook

Подборка видео по Jupyter

Как использовать Jupyter (ipython-notebook) на 100%

Jupyter Notebook Tutorial (Eng)

- 00:00 Introduction

- 01:35 Jupyter notebook example

- 04:11 Installing Python and Jupyter notebooks

- 09:23 Launching Jupyter notebooks

- 11:08 Basic notebook functionality

- 20:58 The kernel, and variables

- 28:38 Other notebook functionality

- 34:45 The menu

- 35:52 Jupyter notebook keyboard shortcuts

- 36:57 Load and display data using pandas

- 40:33 Using terminal commands inside a Jupyter notebook

- 42:30 Jupyter notebook magic commands

- 45:07 Other features outside of the notebooks

- 46:41 Shutting down Jupyter notebooks

- 48:02 Jupyter notebook extensions and other libraries

- 52:47 Conclusion, and thank you

Jupyterlab — STOP Using Jupyter Notebook! Here’s the Better Tool

Источник

In software, it’s said that all abstractions are leaky, and this is true for the Jupyter notebook as it is for any other software.

I most often see this manifest itself with the following issue:

I installed package X and now I can’t import it in the notebook. Help!

This issue is a perrennial source of StackOverflow questions (e.g. this, that, here, there, another, this one, that one, and this… etc.).

Fundamentally the problem is usually rooted in the fact that the Jupyter kernels are disconnected from Jupyter’s shell; in other words, the installer points to a different Python version than is being used in the notebook.

In the simplest contexts this issue does not arise, but when it does, debugging the problem requires knowledge of the intricacies of the operating system, the intricacies of Python package installation, and the intricacies of Jupyter itself.

In other words, the Jupyter notebook, like all abstractions, is leaky.

In the wake of several discussions on this topic with colleagues, some online (exhibit A, exhibit B) and some off, I decided to treat this issue in depth here.

This post will address a couple things:

-

First, I’ll provide a quick, bare-bones answer to the general question, how can I install a Python package so it works with my jupyter notebook, using pip and/or conda?.

-

Second, I’ll dive into some of the background of exactly what the Jupyter notebook abstraction is doing, how it interacts with the complexities of the operating system, and how you can think about where the «leaks» are, and thus better understand what’s happening when things stop working.

-

Third, I’ll talk about some ideas the community might consider to help smooth-over these issues, including some changes that the Jupyter, Pip, and Conda developers might consider to ease the cognitive load on users.

This post will focus on two approaches to installing Python packages: pip and conda.

Other package managers exist (including platform-specific tools like yum, apt, homebrew, etc., as well as cross-platform tools like enstaller), but I’m less familiar with them and won’t be remarking on them further.

Quick Fix: How To Install Packages from the Jupyter Notebook¶

If you’re just looking for a quick answer to the question, how do I install packages so they work with the notebook, then look no further.

pip vs. conda¶

First, a few words on pip vs. conda.

For many users, the choice between pip and conda can be a confusing one.

I wrote way more than you ever want to know about these in a post last year, but the essential difference between the two is this:

- pip installs python packages in any environment.

- conda installs any package in conda environments.

If you already have a Python installation that you’re using, then the choice of which to use is easy:

-

If you installed Python using Anaconda or Miniconda, then use

condato install Python packages. If conda tells you the package you want doesn’t exist, then use pip (or try conda-forge, which has more packages available than the default conda channel). -

If you installed Python any other way (from source, using pyenv, virtualenv, etc.), then use

pipto install Python packages

Finally, because it often comes up, I should mention that you should never use sudo pip install.

NEVER.

It will always lead to problems in the long term, even if it seems to solve them in the short-term.

For example, if pip install gives you a permission error, it likely means you’re trying to install/update packages in a system python, such as /usr/bin/python. Doing this can have bad consequences, as often the operating system itself depends on particular versions of packages within that Python installation.

For day-to-day Python usage, you should isolate your packages from the system Python, using either virtual environments or Anaconda/Miniconda — I personally prefer conda for this, but I know many colleagues who prefer virtualenv.

How to use Conda from the Jupyter Notebook¶

If you’re in the jupyter notebook and you want to install a package with conda, you might be tempted to use the ! notation to run conda directly as a shell command from the notebook:

In [1]:

# DON'T DO THIS! !conda install --yes numpy

Fetching package metadata ........... Solving package specifications: . # All requested packages already installed. # packages in environment at /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python3.6: # numpy 1.13.3 py36h2cdce51_0

(Note that we use --yes to automatically answer y if and when conda asks for user confirmation)

For various reasons that I’ll outline more fully below, this will not generally work if you want to use these installed packages from the current notebook, though it may work in the simplest cases.

Here is a short snippet that should work in general:

In [2]:

# Install a conda package in the current Jupyter kernel import sys !conda install --yes --prefix {sys.prefix} numpy

Fetching package metadata ........... Solving package specifications: . # All requested packages already installed. # packages in environment at /Users/jakevdp/anaconda: # numpy 1.13.3 py36h2cdce51_0

That bit of extra boiler-plate makes certain that conda installs the package in the currently-running Jupyter kernel (thanks to Min Ragan-Kelley for suggesting this approach).

I’ll discuss why this is needed momentarily.

How to use Pip from the Jupyter Notebook¶

If you’re using the Jupyter notebook and want to install a package with pip, you similarly might be inclined to run pip directly in the shell:

In [3]:

# DON'T DO THIS !pip install numpy

Requirement already satisfied: numpy in /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python3.6/lib/python3.6/site-packages

For various reasons that I’ll outline more fully below, this will not generally work if you want to use these installed packages from the current notebook, though it may work in the simplest cases.

Here is a short snippet that should generally work:

In [4]:

# Install a pip package in the current Jupyter kernel import sys !{sys.executable} -m pip install numpy

Requirement already satisfied: numpy in /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/lib/python3.6/site-packages

That bit of extra boiler-plate makes certain that you are running the pip version associated with the current Python kernel, so that the installed packages can be used in the current notebook.

This is related to the fact that, even setting Jupyter notebooks aside, it’s better to install packages using

$ python -m pip install <package>

rather than

$ pip install <package>

because the former is more explicit about where the package will be installed (more on this below).

The Details: Why is Installation from Jupyter so Messy?¶

Those above solutions should work in all cases… but why is that additional boilerplate necessary?

In short, it’s because in Jupyter, the shell environment and the Python executable are disconnected.

Understanding why that matters depends on a basic understanding of a few different concepts:

- how your operating system locates executable programs,

- how Python installs and locates packages

- how Jupyter decides which Python executable to use.

For completeness, I’m going to delve briefly into each of these topics (this discussion is partly drawn from This StackOverflow answer that I wrote last year).

Note: the following discussion assumes Linux, Unix, MacOSX and similar operating systems. Windows has a slightly different architecture, and so some details will differ.

How your operating system locates executables¶

When you’re using the terminal and type a command like python, jupyter, ipython, pip, conda, etc., your operating system contains a well-defined mechanism to find the executable file the name refers to.

On Linux & Mac systems, the system will first check for an alias matching the command; if this fails it references the $PATH environment variable:

/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python3.6/bin:/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python3.6/bin:/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/bin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/sbin:/sbin

$PATH lists the directories, in order, that will be searched for any executable: for example, if I type python on my system with the above $PATH, it will first look for /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python3.6/bin/python, and if that doesn’t exist it will look for /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/bin/python, and so on.

(Parenthetical note: why is the first entry of $PATH repeated twice here? Because every time you launch jupyter notebook, Jupyter prepends the location of the jupyter executable to the beginning of the $PATH. In this case, the location was already at the beginning of the path, and the result is that the entry is duplicated. Duplicate entries add clutter, but cause no harm).

If you want to know what is actually executed when you type python, you can use the type shell command:

python is /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python3.6/bin/python

Note that this is true of any command you use from the terminal:

Even built-in commands like type itself:

You can optionally add the -a tag to see all available versions of the command in your current shell environment; for example:

python is /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python3.6/bin/python python is /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python3.6/bin/python python is /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/bin/python python is /usr/bin/python

conda is /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python3.6/bin/conda conda is /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python3.6/bin/conda conda is /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/bin/conda

pip is /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python3.6/bin/pip pip is /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python3.6/bin/pip pip is /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/bin/pip

When you have multiple available versions of any command, it is important to keep in mind the role of $PATH in choosing which will be used.

How Python locates packages¶

Python uses a similar mechanism to locate imported packages.

The list of paths searched by Python on import is found in sys.path:

Out[12]:

['', '/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/lib/python36.zip', '/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/lib/python3.6', '/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/lib/python3.6/lib-dynload', '/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/lib/python3.6/site-packages', '/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/lib/python3.6/site-packages/schemapi-0.3.0.dev0+791c7f6-py3.6.egg', '/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/lib/python3.6/site-packages/setuptools-27.2.0-py3.6.egg', '/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/lib/python3.6/site-packages/IPython/extensions', '/Users/jakevdp/.ipython']

By default, the first place Python looks for a module is an empty path, meaning the current working directory.

If the module is not found there, it goes down the list of locations until the module is found.

You can find out which location has been used using the __path__ attribute of an imported module:

In [13]:

import numpy numpy.__path__

Out[13]:

['/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/lib/python3.6/site-packages/numpy']

In most cases, a Python package you install with pip or with conda will be put in a directory called site-packages.

The important thing to realize is that each Python executable has its own site-packages: what this means is that when you install a package, it is associated with particular python executable and by default can only be used with that Python installation!

We can see this by printing the sys.path variables for each of the available python executables in my path, using Jupyter’s delightful ability to mix Python and bash commands in a single code block:

In [14]:

paths = !type -a python for path in set(paths): path = path.split()[-1] print(path) !{path} -c "import sys; print(sys.path)" print()

/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python3.6/bin/python ['', '/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python3.6/lib/python36.zip', '/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python3.6/lib/python3.6', '/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python3.6/lib/python3.6/lib-dynload', '/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python3.6/lib/python3.6/site-packages'] /usr/bin/python ['', '/System/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python27.zip', '/System/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7', '/System/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7/plat-darwin', '/System/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7/plat-mac', '/System/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7/plat-mac/lib-scriptpackages', '/System/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7/lib-tk', '/System/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7/lib-old', '/System/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7/lib-dynload', '/Library/Python/2.7/site-packages', '/System/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/Extras/lib/python', '/System/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/Extras/lib/python/PyObjC'] /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/bin/python ['', '/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/lib/python36.zip', '/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/lib/python3.6', '/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/lib/python3.6/lib-dynload', '/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/lib/python3.6/site-packages', '/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/lib/python3.6/site-packages/schemapi-0.3.0.dev0+791c7f6-py3.6.egg', '/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/lib/python3.6/site-packages/setuptools-27.2.0-py3.6.egg']

The full details here are not particularly important, but it is important to emphasize that each Python executable has its own distinct paths, and unless you modify sys.path (which should only be done with great care) you cannot import packages installed in a different Python environment.

When you run pip install or conda install, these commands are associated with a particular Python version:

pipinstalls packages in the Python in its same pathcondainstalls packages in the current active conda environment

So, for example we see that pip install will install to the conda environment named python3.6:

pip is /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python3.6/bin/pip

And conda install will do the same, because python3.6 is the current active environment (notice the * indicating the active environment):

# conda environments: # python2.7 /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python2.7 python3.5 /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python3.5 python3.6 * /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python3.6 rstats /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/rstats root /Users/jakevdp/anaconda

The reason both pip and conda default to the conda python3.6 environment is that this is the Python environment I used to launch the notebook.

I’ll say this again for emphasis: the shell environment in Jupyter notebook matches the Python version used to launch the notebook.

How Jupyter executes code: Jupyter Kernels¶

The next relevant question is how Jupyter chooses to execute Python code, and this brings us to the concept of a Jupyter Kernel.

A Jupyter kernel is a set of files that point Jupyter to some means of executing code within the notebook.

For Python kernels, this will point to a particular Python version, but Jupyter is designed to be much more general than this: Jupyter has dozens of available kernels for languages including Python 2, Python 3, Julia, R, Ruby, Haskell, and even C++ and Fortran!

If you’re using the Jupyter notebook, you can change your kernel at any time using the Kernel → Choose Kernel menu item.

To see the kernels you have available on your system, you can run the following command in the shell:

Available kernels: python3 /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python3.6/lib/python3.6/site-packages/ipykernel/resources conda-root /Users/jakevdp/Library/Jupyter/kernels/conda-root python2.7 /Users/jakevdp/Library/Jupyter/kernels/python2.7 python3.5 /Users/jakevdp/Library/Jupyter/kernels/python3.5 python3.6 /Users/jakevdp/Library/Jupyter/kernels/python3.6

Each of these listed kernels is a directory that contains a file called kernel.json which specifies, among other things, which language and executable the kernel should use.

For example:

In [18]:

!cat /Users/jakevdp/Library/Jupyter/kernels/conda-root/kernel.json

{

"argv": [

"/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/bin/python",

"-m",

"ipykernel_launcher",

"-f",

"{connection_file}"

],

"display_name": "python (conda-root)",

"language": "python"

}

If you’d like to create a new kernel, you can do so using the jupyter ipykernel command;

for example, I created the above kernels for my primary conda environments using the following as a template:

$ source activate myenv

$ python -m ipykernel install --user --name myenv --display-name "Python (myenv)"The Root of the Issue¶

Now we have the full background to answer our question: Why don’t !pip install or !conda install always work from the notebook?

The root of the issue is this: the shell environment is determined when the Jupyter notebook is launched, while the Python executable is determined by the kernel, and the two do not necessarily match.

In other words, there is no guarantee that the python, pip, and conda in your $PATH will be compatible with the python executable used by the notebook.

Recall that the python in your path can be determined using

python is /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/envs/python3.6/bin/python

The Python executable being used in the notebook can be determined using

Out[20]:

'/Users/jakevdp/anaconda/bin/python'

In my current notebook environment, the two differ.

This is why a simple !pip install or !conda install does not work: the commands install packages in the site-packages of the wrong Python installation.

As noted above, we can get around this by explicitly identifying where we want packages to be installed.

For conda, you can set the prefix manually in the shell command:

$ conda install --yes --prefix /Users/jakevdp/anaconda numpyor, to automatically use the correct prefix (using syntax available in the notebook)

!conda install --yes --prefix {sys.prefix} numpyFor pip, you can specify the Python executable explicitly:

$ /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/bin/python -m pip install numpyor, to automatically use the correct executable (again using notebook shell syntax)

!{sys.executable} -m pip install numpyRemember: you need your installation command to match the current python kernel if you want installed packages to be available in the notebook.

Some Modest Proposals¶

So, in summary, the reason that installation of packages in the Jupyter notebook is fraught with difficulty is fundamentally that Jupyter’s shell environment and Python kernel are mismatched, and that means that you have to do more than simply pip install or conda install to make things work.

The exception is the special case where you run jupyter notebook from the same Python environment to which your kernel points; in that case the simple installation approach should work.

But that leaves us in an undesireable place, as it increases the learning curve for novice users who may want to do something they (rightly) presume should be simple: install a package and then use it.

So what can we as a community do to smooth-out this issue?

I have a few ideas, some of which might even be useful:

Potential Changes to Jupyter¶

As I mentioned, the fundamental issue is a mismatch between Jupyter’s shell environment and compute kernel.

So, could we massage kernel specifications such that they force the two to match?

Perhaps: for example, this github issue shows an approach to modifying shell variables as part of kernel startup.

Basically, in your kernel directory, you can add a script kernel-startup.sh that looks something like this (and make sure you change the permissions so that it’s executable):

#!/usr/bin/env bash

# activate anaconda env

source activate myenv

# this is the critical part, and should be at the end of your script:

exec python -m ipykernel $@Then in your kernel.json file, modify the argv field to look like this:

"argv": [

"/path/to/kernel-startup.sh",

"-f",

"{connection_file}"

]Once you do this, switching to the myenv kernel will automatically activate the myenv conda environment, which changes your $CONDA_PREFIX, $PATH and other system variables such that !conda install XXX and !pip install XXX will work correctly. A similar approach could work for virtualenvs or other Python environments.

There is one tricky issue here: this approach will fail if your myenv environment does not have the ipykernel package installed, and probably also requires it to have a jupyter version compatible with that used to launch the notebook. So it’s not a full solution to the problem by any means, but if Python kernels could be designed to do this sort of shell initialization by default, it would be far less confusing to users: !pip install and !conda install would simply work.

Potential Changes to pip¶

One source of installation confusion, even outside of Jupyter, is the fact that, depending on the nature of your system’s aliases and $PATH variable, pip and python might point to different paths.

In this case pip install will install packages to a path inaccessible to the python executable.

For this reason, it is safer to use python -m pip install, which explicitly specifies the desired Python version (explicit is better than implicit, after all).

This is one reason that pip install no longer appears in Python’s docs, and experienced Python educators like David Beazley never teach bare pip.

CPython developer Nick Coghlan has even indicated that the pip executable may someday be deprecated in favor of python -m pip.

Even though it’s more verbose, I think forcing users to be explicit would be a useful change, particularly as the use of virtualenvs and conda envs becomes more common.

Changes to Conda¶

I can think of a couple modifications to conda’s API that may be helpful to users

Explicit invocation¶

For symmetry with pip, it would be nice if python -m conda install could be expected to work in the same way the pip counterpart does.

You can call conda this way in the root environment, but the conda Python package (as opposed to the conda executable) cannot currently be installed anywhere but the root environment:

(myenv) jakevdp$ conda install conda

Fetching package metadata ...........

InstallError: Error: 'conda' can only be installed into the root environmentI suspect that allowing python -m conda install in all conda environments would require a fairly significant redesign of conda’s installation model, so it may not be worth the change just for symmetry with pip‘s API.

That said, such a symmetry would certainly be a help to users.

A pip channel for conda?¶

Another useful change conda could make would be to add a channel that essentially mirrors the Python Package Index, so that when you do conda install some-package it will automatically draw from packages available to pip as well.

I don’t have a deep enough knowledge of conda’s architecture to know how easy such a feature would be to implement, but I do have loads of experiences helping newcomers to Python and/or conda: I can say with certainty that such a feature would go a long way toward softening their learning curve.

New Jupyter Magic Functions¶

Even if the above changes to the stack are not possible or desirable, we could simplify the user experience somewhat by introducing %pip and %conda magic functions within the Jupyter notebook that detect the current kernel and make certain packages are installed in the correct location.

pip magic¶

For example, here’s how you can define a %pip magic function that works in the current kernel:

In [21]:

from IPython.core.magic import register_line_magic @register_line_magic def pip(args): """Use pip from the current kernel""" from pip import main main(args.split())

Running it as follows will install packages in the expected location

Requirement already satisfied: numpy in /Users/jakevdp/anaconda/lib/python3.6/site-packages

Note that Jupyter developer Matthias Bussonnier has published essentially this in his pip_magic repository, so you can do

$ python -m pip install pip_magicand use this right now (that is, assuming you install pip_magic in the right place!)

conda magic¶

Similarly, we can define a conda magic that will do the right thing if you type %conda install XXX.

This is a bit more involved than the pip magic, because it must first confirm that the environment is conda-compatible, and then (related to the lack of python -m conda install) must call a subprocess to execute the appropriate shell command:

In [23]:

from IPython.core.magic import register_line_magic import sys import os from subprocess import Popen, PIPE def is_conda_environment(): """Return True if the current Python executable is in a conda env""" # TODO: make this work with Conda.exe in Windows conda_exec = os.path.join(os.path.dirname(sys.executable), 'conda') conda_history = os.path.join(sys.prefix, 'conda-meta', 'history') return os.path.exists(conda_exec) and os.path.exists(conda_history) @register_line_magic def conda(args): """Use conda from the current kernel""" # TODO: make this work with Conda.exe in Windows # TODO: fix string encoding to work with Python 2 if not is_conda_environment(): raise ValueError("The python kernel does not appear to be a conda environment. " "Please use ``%pip install`` instead.") conda_executable = os.path.join(os.path.dirname(sys.executable), 'conda') args = [conda_executable] + args.split() # Add --prefix to point conda installation to the current environment if args[1] in ['install', 'update', 'upgrade', 'remove', 'uninstall', 'list']: if '-p' not in args and '--prefix' not in args: args.insert(2, '--prefix') args.insert(3, sys.prefix) # Because the notebook does not allow us to respond "yes" during the # installation, we need to insert --yes in the argument list for some commands if args[1] in ['install', 'update', 'upgrade', 'remove', 'uninstall', 'create']: if '-y' not in args and '--yes' not in args: args.insert(2, '--yes') # Call conda from command line with subprocess & send results to stdout & stderr with Popen(args, stdout=PIPE, stderr=PIPE) as process: # Read stdout character by character, as it includes real-time progress updates for c in iter(lambda: process.stdout.read(1), b''): sys.stdout.write(c.decode(sys.stdout.encoding)) # Read stderr line by line, because real-time does not matter for line in iter(process.stderr.readline, b''): sys.stderr.write(line.decode(sys.stderr.encoding))

You can now use %conda install and it will install packages to the correct environment:

Fetching package metadata ........... Solving package specifications: . # All requested packages already installed. # packages in environment at /Users/jakevdp/anaconda: # numpy 1.13.3 py36h2cdce51_0

This conda magic still needs some work to be a general solution (cf. the TODO comments in the code), but I think this is a useful start.

If a pip magic and conda magic similar to the above were added to Jupyter’s default set of magic commands, I think it could go a long way toward solving the common problems that users have when trying to install Python packages for use with Jupyter notebooks.

This approach is not without its own dangers, though: these magics are yet another layer of abstraction that, like all abstractions, will inevitably leak.

But if they are implemented carefully, I think it would lead to a much nicer overall user experience.

Summary¶

In this post, I tried to answer once and for all the perennial question, how do I install Python packages in the Jupyter notebook.

After proposing some simple solutions that can be used today, I went into a detailed explanation of why these solutions are necessary: it comes down to the fact that in Jupyter, the kernel is disconnected from the shell.

The kernel environment can be changed at runtime, while the shell environment is determined when the notebook is launched.

The fact that a full explanation took so many words and touched so many concepts, I think, indicates a real usability issue for the Jupyter ecosystem, and so I proposed a few possible avenues that the community might adopt to try to streamline the experience for users.

One final addendum: I have a huge amount of respect and appreciation for the developers of Jupyter, conda, pip, and related tools that form the foundations of the Python data science ecosystem.

I’m fairly certain those developers have already considered these issues and weighed some of these potential fixes – if any of you are reading this, please feel free to comment and set me straight on anything I’ve overlooked!

And, finally, thanks for all that you do for the open source community.

Thanks to Andy Mueller, Craig Citro, and Matthias Bussonnier for helpful comments on an early draft of this post.

This post was written within a Jupyter notebook; you can view a static version here or download the full notebook here.