В Powershell существует несколько уровней ошибок и несколько способов их обработать. Проблемы одного уровня (Non-Terminating Errors) можно решить с помощью привычных для Powershell команд. Другой уровень ошибок (Terminating Errors) решается с помощью исключений (Exceptions) стандартного, для большинства языков, блока в виде Try, Catch и Finally.

Как Powershell обрабатывает ошибки

До рассмотрения основных методов посмотрим на теоретическую часть.

Автоматические переменные $Error

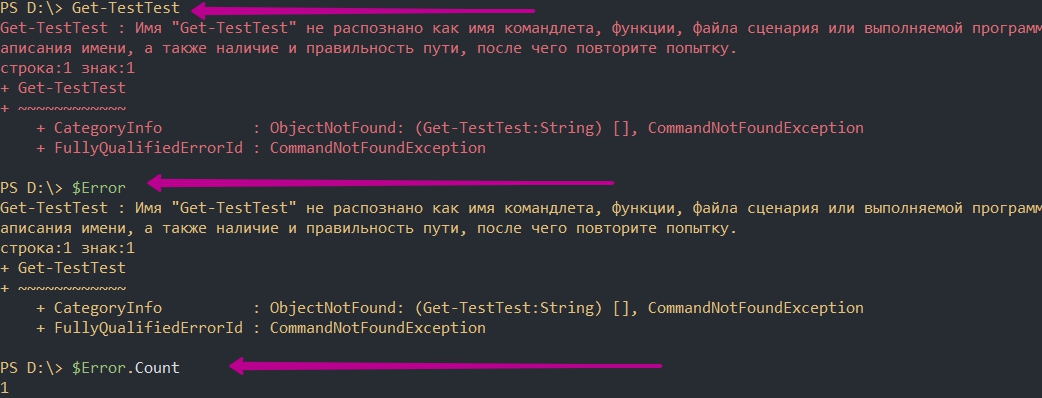

В Powershell существует множество переменных, которые создаются автоматически. Одна из таких переменных — $Error хранит в себе все ошибки за текущий сеанс PS. Например так я выведу количество ошибок и их сообщение за весь сеанс:

Get-TestTest

$Error

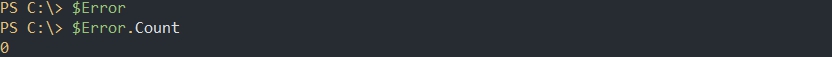

$Error.CountПри отсутствии каких либо ошибок мы бы получили пустой ответ, а счетчик будет равняться 0:

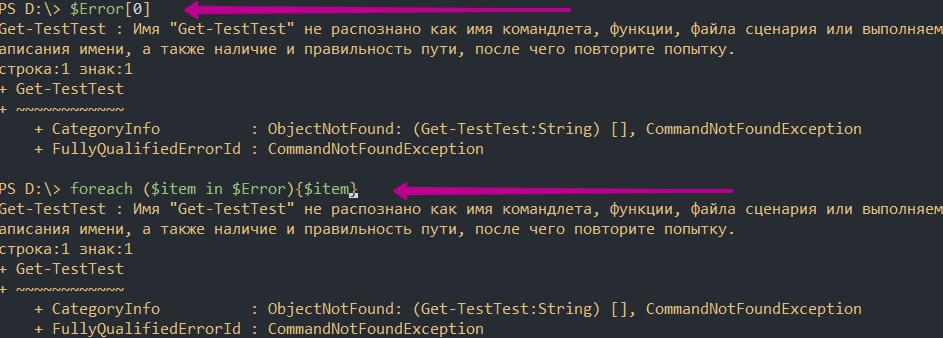

Переменная $Error являет массивом и мы можем по нему пройтись или обратиться по индексу что бы найти нужную ошибку:

$Error[0]

foreach ($item in $Error){$item}Свойства объекта $Error

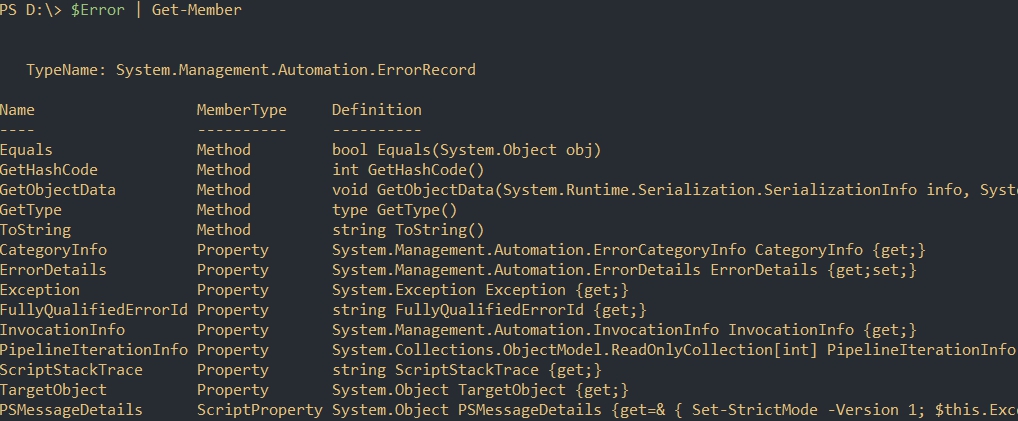

Так же как и все что создается в Powershell переменная $Error так же имеет свойства (дополнительную информацию) и методы. Названия свойств и методов можно увидеть через команду Get-Member:

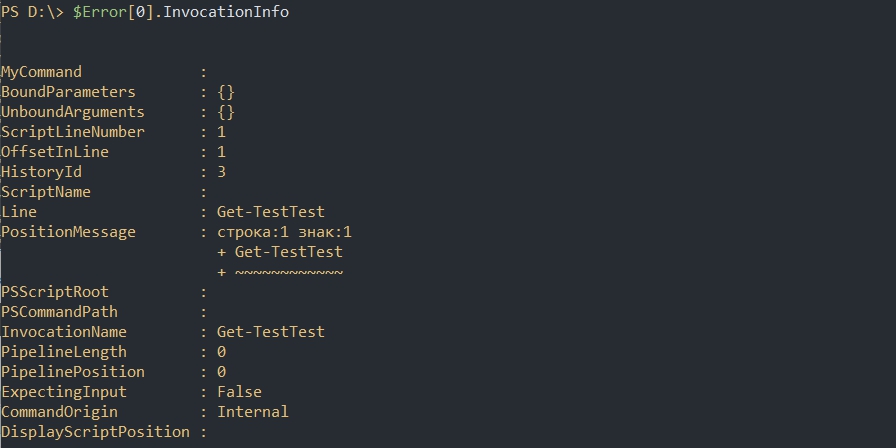

$Error | Get-MemberНапример, с помощью свойства InvocationInfo, мы можем вывести более структурный отчет об ошибки:

$Error[0].InvocationInfoМетоды объекта $Error

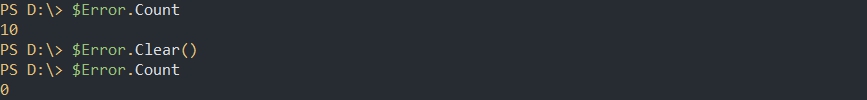

Например мы можем очистить логи ошибок используя clear:

$Error.clear()Критические ошибки (Terminating Errors)

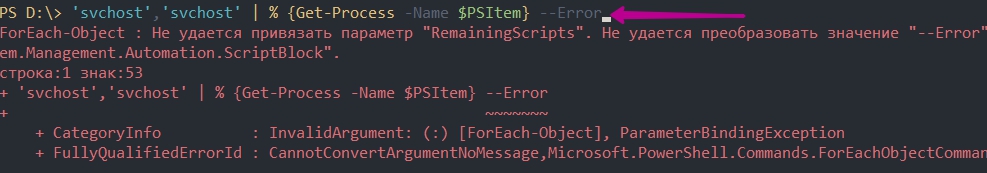

Критические (завершающие) ошибки останавливают работу скрипта. Например это может быть ошибка в названии командлета или параметра. В следующем примере команда должна была бы вернуть процессы «svchost» дважды, но из-за использования несуществующего параметра ‘—Error’ не выполнится вообще:

'svchost','svchost' | % {Get-Process -Name $PSItem} --Error Не критические ошибки (Non-Terminating Errors)

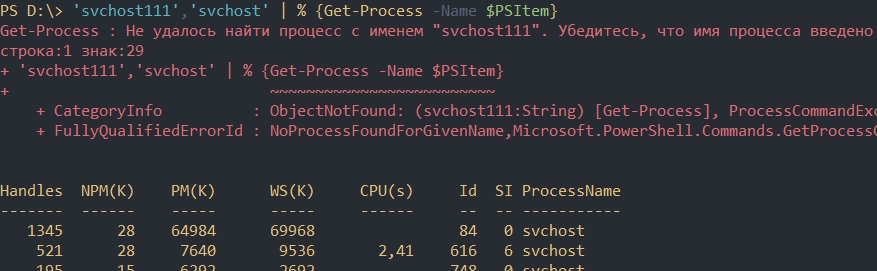

Не критические (не завершающие) ошибки не остановят работу скрипта полностью, но могут вывести сообщение об этом. Это могут быть ошибки не в самих командлетах Powershell, а в значениях, которые вы используете. На предыдущем примере мы можем допустить опечатку в названии процессов, но команда все равно продолжит работу:

'svchost111','svchost' | % {Get-Process -Name $PSItem}Как видно у нас появилась информация о проблеме с первым процессом ‘svchost111’, так как его не существует. Обычный процесс ‘svchost’ он у нас вывелся корректно.

Параметр ErrorVariable

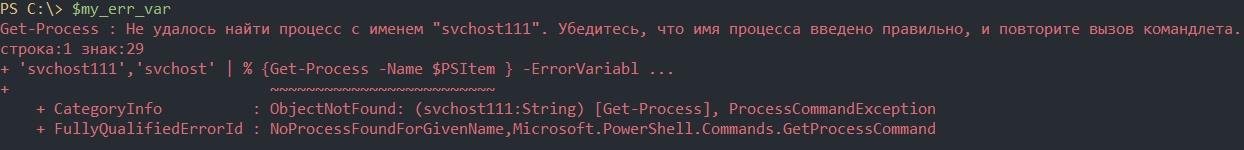

Если вы не хотите использовать автоматическую переменную $Error, то сможете определять свою переменную индивидуально для каждой команды. Эта переменная определяется в параметре ErrorVariable:

'svchost111','svchost' | % {Get-Process -Name $PSItem } -ErrorVariable my_err_var

$my_err_varПеременная будет иметь те же свойства, что и автоматическая:

$my_err_var.InvocationInfoОбработка некритических ошибок

У нас есть два способа определения последующих действий при ‘Non-Terminating Errors’. Это правило можно задать локально и глобально (в рамках сессии). Мы сможем полностью остановить работу скрипта или вообще отменить вывод ошибок.

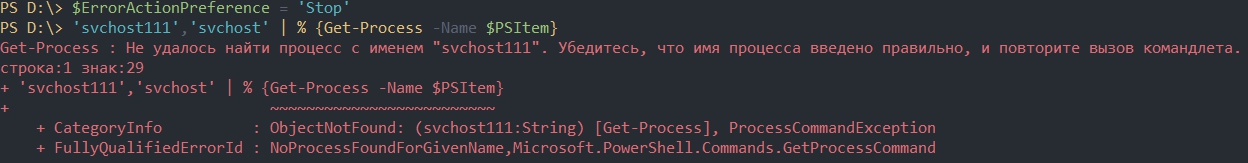

Приоритет ошибок с $ErrorActionPreference

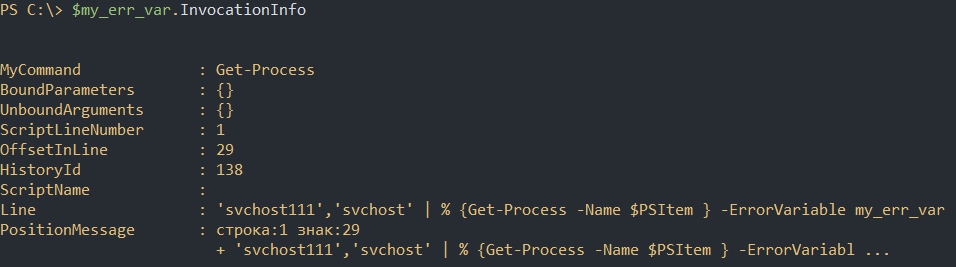

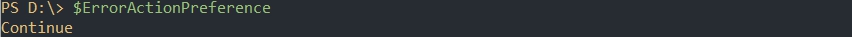

Еще одна встроенная переменная в Powershell $ErrorActionPreference глобально определяет что должно случится, если у нас появится обычная ошибка. По умолчанию это значение равно ‘Continue’, что значит «вывести информацию об ошибке и продолжить работу»:

$ErrorActionPreferenceЕсли мы поменяем значение этой переменной на ‘Stop’, то поведение скриптов и команд будет аналогично критичным ошибкам. Вы можете убедиться в этом на прошлом скрипте с неверным именем процесса:

$ErrorActionPreference = 'Stop'

'svchost111','svchost' | % {Get-Process -Name $PSItem}Т.е. скрипт был остановлен в самом начале. Значение переменной будет храниться до момента завершения сессии Powershell. При перезагрузке компьютера, например, вернется значение по умолчанию.

Ниже значение, которые мы можем установить в переменной $ErrorActionPreference:

- Continue — вывод ошибки и продолжение работы;

- Inquire — приостановит работу скрипта и спросит о дальнейших действиях;

- SilentlyContinue — скрипт продолжит свою работу без вывода ошибок;

- Stop — остановка скрипта при первой ошибке.

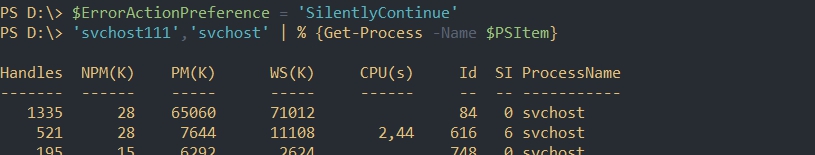

Самый частый параметр, который мне приходится использовать — SilentlyContinue:

$ErrorActionPreference = 'SilentlyContinue'

'svchost111','svchost' | % {Get-Process -Name $PSItem}Использование параметра ErrorAction

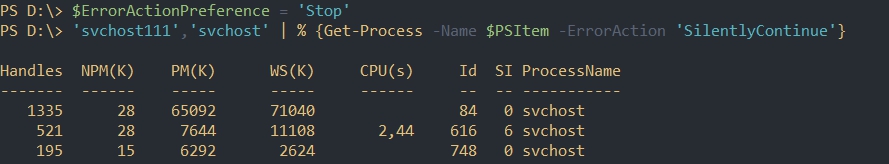

Переменная $ErrorActionPreference указывает глобальный приоритет, но мы можем определить такую логику в рамках команды с параметром ErrorAction. Этот параметр имеет больший приоритет чем $ErrorActionPreference. В следующем примере, глобальная переменная определяет полную остановку скрипта, а в параметр ErrorAction говорит «не выводить ошибок и продолжить работу»:

$ErrorActionPreference = 'Stop'

'svchost111','svchost' | % {Get-Process -Name $PSItem -ErrorAction 'SilentlyContinue'}Кроме ‘SilentlyContinue’ мы можем указывать те же параметры, что и в переменной $ErrorActionPreference.

Значение Stop, в обоих случаях, делает ошибку критической.

Обработка критических ошибок и исключений с Try, Catch и Finally

Когда мы ожидаем получить какую-то ошибку и добавить логику нужно использовать Try и Catch. Например, если в вариантах выше мы определяли нужно ли нам отображать ошибку или останавливать скрипт, то теперь сможем изменить выполнение скрипта или команды вообще. Блок Try и Catch работает только с критическими ошибками и в случаях если $ErrorActionPreference или ErrorAction имеют значение Stop.

Например, если с помощью Powershell мы пытаемся подключиться к множеству компьютеров один из них может быть выключен — это приведет к ошибке. Так как эту ситуацию мы можем предвидеть, то мы можем обработать ее. Процесс обработки ошибок называется исключением (Exception).

Синтаксис и логика работы команды следующая:

try {

# Пытаемся подключиться к компьютеру

}

catch [Имя исключения 1],[Имя исключения 2]{

# Раз компьютер не доступен, сделать то-то

}

finally {

# Блок, который выполняется в любом случае последним

}Блок try мониторит ошибки и если она произойдет, то она добавится в переменную $Error и скрипт перейдет к блоку Catch. Так как ошибки могут быть разные (нет доступа, нет сети, блокирует правило фаервола и т.д.) то мы можем прописывать один блок Try и несколько Catch:

try {

# Пытаемся подключится

}

catch ['Нет сети']['Блокирует фаервол']{

# Записываем в файл

}

catch ['Нет прав на подключение']{

# Подключаемся под другим пользователем

}

Сам блок finally — не обязательный и используется редко. Он выполняется самым последним, после try и catch и не имеет каких-то условий.

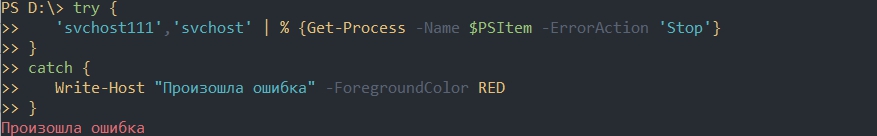

Catch для всех типов исключений

Как и было показано выше мы можем использовать блок Catch для конкретного типа ошибок, например при проблемах с доступом. Если в этом месте ничего не указывать — в этом блоке будут обрабатываться все варианты ошибок:

try {

'svchost111','svchost' | % {Get-Process -Name $PSItem -ErrorAction 'Stop'}

}

catch {

Write-Host "Какая-то неисправность" -ForegroundColor RED

}Такой подход не рекомендуется использовать часто, так как вы можете пропустить что-то важное.

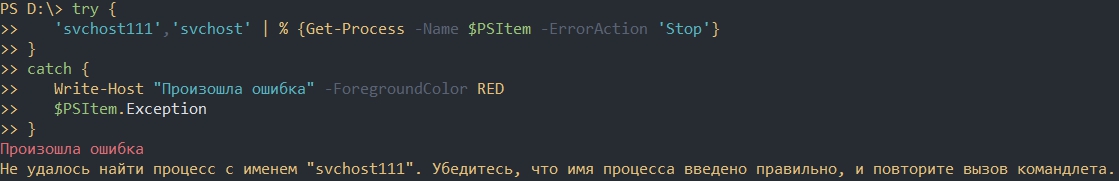

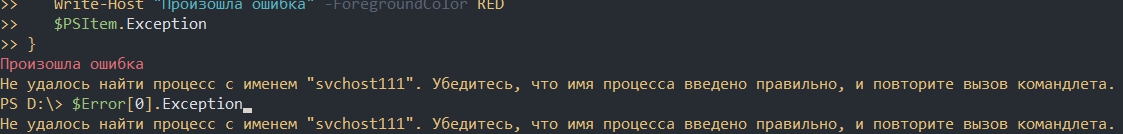

Мы можем вывести в блоке catch текст ошибки используя $PSItem.Exception:

try {

'svchost111','svchost' | % {Get-Process -Name $PSItem -ErrorAction 'Stop'}

}

catch {

Write-Host "Какая-то неисправность" -ForegroundColor RED

$PSItem.Exception

}Переменная $PSItem хранит информацию о текущей ошибке, а глобальная переменная $Error будет хранит информацию обо всех ошибках. Так, например, я выведу одну и ту же информацию:

$Error[0].ExceptionСоздание отдельных исключений

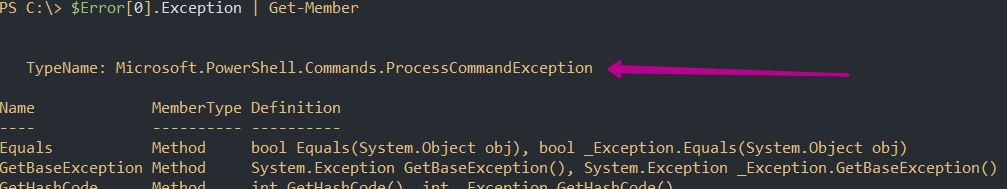

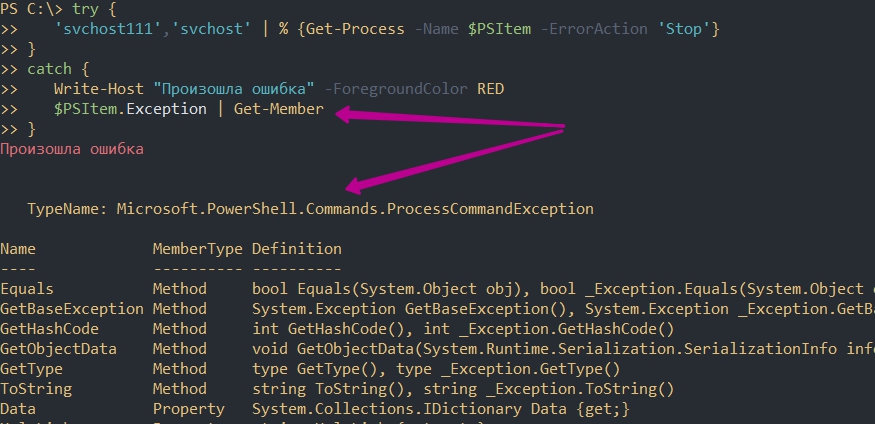

Что бы обработать отдельную ошибку сначала нужно найти ее имя. Это имя можно увидеть при получении свойств и методов у значения переменной $Error:

$Error[0].Exception | Get-MemberТак же сработает и в блоке Catch с $PSItem:

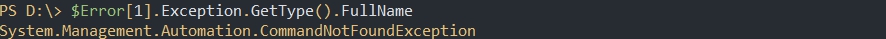

Для вывода только имени можно использовать свойство FullName:

$Error[0].Exception.GetType().FullNameДалее, это имя, мы вставляем в блок Catch:

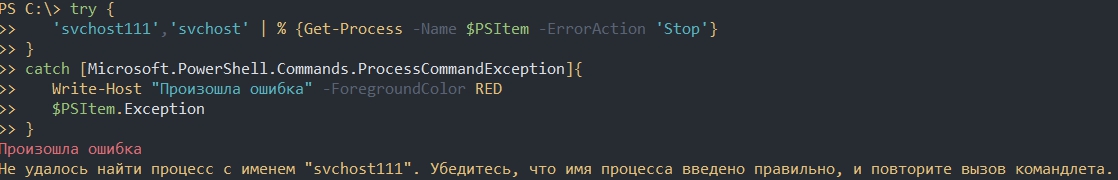

try {

'svchost111','svchost' | % {Get-Process -Name $PSItem -ErrorAction 'Stop'}

}

catch [Microsoft.PowerShell.Commands.ProcessCommandException]{

Write-Host "Произошла ошибка" -ForegroundColor RED

$PSItem.Exception

}Так же, как и было описано выше мы можем усложнять эти блоки как угодно указывая множество исключений в одном catch.

Выброс своих исключений

Иногда нужно создать свои собственные исключения. Например мы можем запретить добавлять через какой-то скрипт названия содержащие маленькие буквы или сотрудников без указания возраста и т.д. Способов создать такие ошибки — два и они тоже делятся на критические и обычные.

Выброс с throw

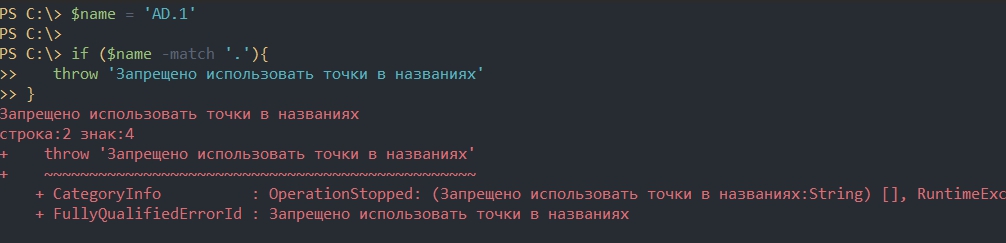

Throw — выбрасывает ошибку, которая останавливает работу скрипта. Этот тип ошибок относится к критическим. Например мы можем указать только текст для дополнительной информации:

$name = 'AD.1'

if ($name -match '.'){

throw 'Запрещено использовать точки в названиях'

}

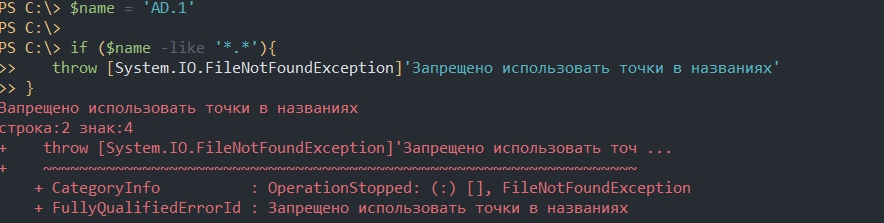

Если нужно, то мы можем использовать исключения, которые уже были созданы в Powershell:

$name = 'AD.1'

if ($name -like '*.*'){

throw [System.IO.FileNotFoundException]'Запрещено использовать точки в названиях'

}

Использование Write-Error

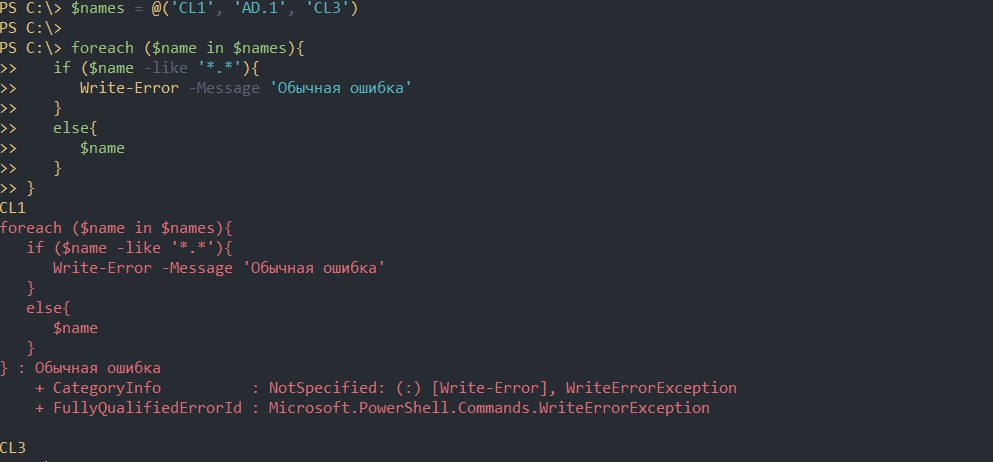

Команда Write-Error работает так же, как и ключ ErrorAction. Мы можем просто отобразить какую-то ошибку и продолжить выполнение скрипта:

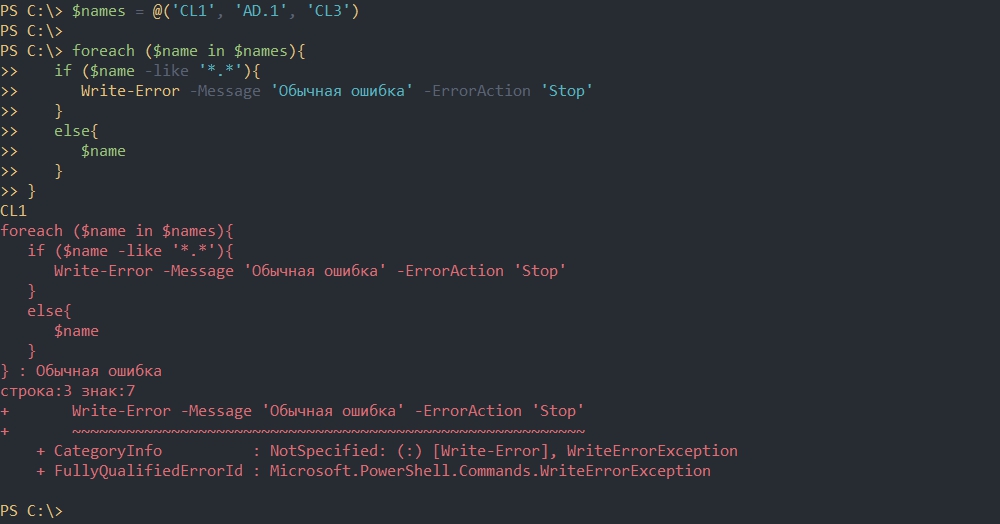

$names = @('CL1', 'AD.1', 'CL3')

foreach ($name in $names){

if ($name -like '*.*'){

Write-Error -Message 'Обычная ошибка'

}

else{

$name

}

}При необходимости мы можем использовать параметр ErrorAction. Значения этого параметра были описаны выше. Мы можем указать значение ‘Stop’, что полностью остановит выполнение скрипта:

$names = @('CL1', 'AD.1', 'CL3')

foreach ($name in $names){

if ($name -like '*.*'){

Write-Error -Message 'Обычная ошибка' -ErrorAction 'Stop'

}

else{

$name

}

}Отличие команды Write-Error с ключом ErrorAction от обычных команд в том, что мы можем указывать исключения в параметре Exception:

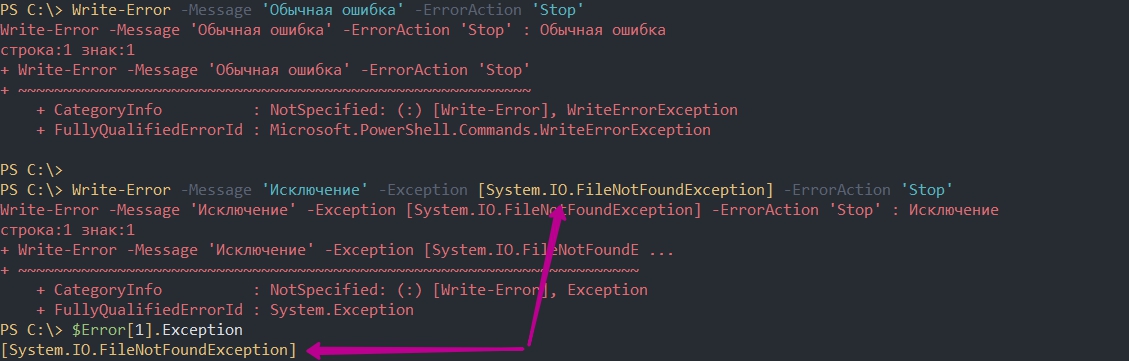

Write-Error -Message 'Обычная ошибка' -ErrorAction 'Stop'

Write-Error -Message 'Исключение' -Exception [System.IO.FileNotFoundException] -ErrorAction 'Stop'

В Exception мы так же можем указывать сообщение. При этом оно будет отображаться в переменной $Error:

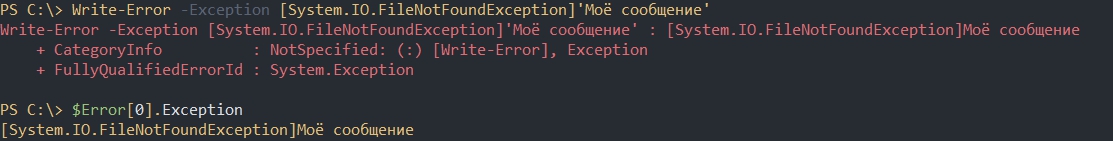

Write-Error -Exception [System.IO.FileNotFoundException]'Моё сообщение'

…

Теги:

#powershell

#ошибки

Содержание

- Everything you wanted to know about exceptions

- Basic terminology

- Exception

- Throw and Catch

- The call stack

- Terminating and non-terminating errors

- Swallowing an exception

- Basic command syntax

- Throw

- Write-Error -ErrorAction Stop

- Cmdlet -ErrorAction Stop

- Try/Catch

- Try/Finally

- Try/Catch/Finally

- $PSItem

- PSItem.ToString()

- $PSItem.InvocationInfo

- $PSItem.ScriptStackTrace

- $PSItem.Exception

- $PSItem.Exception.Message

- $PSItem.Exception.InnerException

- $PSItem.Exception.StackTrace

- Working with exceptions

- Catching typed exceptions

- Catch multiple types at once

- Throwing typed exceptions

- Write-Error -Exception

- The big list of .NET exceptions

- Exceptions are objects

- Re-throwing an exception

- Re-throwing a new exception

- $PSCmdlet.ThrowTerminatingError()

- Try can create terminating errors

- $PSCmdlet.ThrowTerminatingError() inside try/catch

- Public function templates

- Closing remarks

- Все, что вы хотели знать об исключениях

- Базовая терминология

- Исключение

- Throw и Catch

- Стек вызовов

- Неустранимые и устранимые ошибки

- Игнорирование исключения

- Основной синтаксис команды

- Ключевое слово throw

- Параметр -ErrorAction Stop командлета Write-Error

- Параметр -ErrorAction Stop в командлете

- Try и Catch

- Try и Finally

- Try, catch и finally

- $PSItem

- PSItem.ToString()

- $PSItem.InvocationInfo

- $PSItem.ScriptStackTrace

- $PSItem.Exception

- $PSItem.Exception.Message

- $PSItem.Exception.InnerException

- $PSItem.Exception.StackTrace

- Работа с исключениями

- Перехват типизированных исключений

- Одновременный перехват нескольких типов

- Вызов типизированных исключений

- Параметр -Exception командлета Write-Error

- Большой список исключений .NET

- Исключения как объекты

- Повторный вызов исключения

- Повторный вызов нового исключения

- $PSCmdlet.ThrowTerminatingError()

- Try как источник неустранимой ошибки

- Метод $PSCmdlet.ThrowTerminatingError() в try/catch

- Шаблоны общих функций

- Ключевое слово trap

- Заключительное слово

Everything you wanted to know about exceptions

Error handling is just part of life when it comes to writing code. We can often check and validate conditions for expected behavior. When the unexpected happens, we turn to exception handling. You can easily handle exceptions generated by other people’s code or you can generate your own exceptions for others to handle.

The original version of this article appeared on the blog written by @KevinMarquette. The PowerShell team thanks Kevin for sharing this content with us. Please check out his blog at PowerShellExplained.com.

Basic terminology

We need to cover some basic terms before we jump into this one.

Exception

An Exception is like an event that is created when normal error handling can’t deal with the issue. Trying to divide a number by zero or running out of memory are examples of something that creates an exception. Sometimes the author of the code you’re using creates exceptions for certain issues when they happen.

Throw and Catch

When an exception happens, we say that an exception is thrown. To handle a thrown exception, you need to catch it. If an exception is thrown and it isn’t caught by something, the script stops executing.

The call stack

The call stack is the list of functions that have called each other. When a function is called, it gets added to the stack or the top of the list. When the function exits or returns, it is removed from the stack.

When an exception is thrown, that call stack is checked in order for an exception handler to catch it.

Terminating and non-terminating errors

An exception is generally a terminating error. A thrown exception is either be caught or it terminates the current execution. By default, a non-terminating error is generated by Write-Error and it adds an error to the output stream without throwing an exception.

I point this out because Write-Error and other non-terminating errors do not trigger the catch .

Swallowing an exception

This is when you catch an error just to suppress it. Do this with caution because it can make troubleshooting issues very difficult.

Basic command syntax

Here is a quick overview of the basic exception handling syntax used in PowerShell.

Throw

To create our own exception event, we throw an exception with the throw keyword.

This creates a runtime exception that is a terminating error. It’s handled by a catch in a calling function or exits the script with a message like this.

Write-Error -ErrorAction Stop

I mentioned that Write-Error doesn’t throw a terminating error by default. If you specify -ErrorAction Stop , Write-Error generates a terminating error that can be handled with a catch .

Thank you to Lee Dailey for reminding about using -ErrorAction Stop this way.

Cmdlet -ErrorAction Stop

If you specify -ErrorAction Stop on any advanced function or cmdlet, it turns all Write-Error statements into terminating errors that stop execution or that can be handled by a catch .

Try/Catch

The way exception handling works in PowerShell (and many other languages) is that you first try a section of code and if it throws an error, you can catch it. Here is a quick sample.

The catch script only runs if there’s a terminating error. If the try executes correctly, then it skips over the catch . You can access the exception information in the catch block using the $_ variable.

Try/Finally

Sometimes you don’t need to handle an error but still need some code to execute if an exception happens or not. A finally script does exactly that.

Take a look at this example:

Anytime you open or connect to a resource, you should close it. If the ExecuteNonQuery() throws an exception, the connection isn’t closed. Here is the same code inside a try/finally block.

In this example, the connection is closed if there’s an error. It also is closed if there’s no error. The finally script runs every time.

Because you’re not catching the exception, it still gets propagated up the call stack.

Try/Catch/Finally

It’s perfectly valid to use catch and finally together. Most of the time you’ll use one or the other, but you may find scenarios where you use both.

$PSItem

Now that we got the basics out of the way, we can dig a little deeper.

Inside the catch block, there’s an automatic variable ( $PSItem or $_ ) of type ErrorRecord that contains the details about the exception. Here is a quick overview of some of the key properties.

For these examples, I used an invalid path in ReadAllText to generate this exception.

PSItem.ToString()

This gives you the cleanest message to use in logging and general output. ToString() is automatically called if $PSItem is placed inside a string.

$PSItem.InvocationInfo

This property contains additional information collected by PowerShell about the function or script where the exception was thrown. Here is the InvocationInfo from the sample exception that I created.

The important details here show the ScriptName , the Line of code and the ScriptLineNumber where the invocation started.

$PSItem.ScriptStackTrace

This property shows the order of function calls that got you to the code where the exception was generated.

I’m only making calls to functions in the same script but this would track the calls if multiple scripts were involved.

$PSItem.Exception

This is the actual exception that was thrown.

$PSItem.Exception.Message

This is the general message that describes the exception and is a good starting point when troubleshooting. Most exceptions have a default message but can also be set to something custom when the exception is thrown.

This is also the message returned when calling $PSItem.ToString() if there was not one set on the ErrorRecord .

$PSItem.Exception.InnerException

Exceptions can contain inner exceptions. This is often the case when the code you’re calling catches an exception and throws a different exception. The original exception is placed inside the new exception.

I will revisit this later when I talk about re-throwing exceptions.

$PSItem.Exception.StackTrace

This is the StackTrace for the exception. I showed a ScriptStackTrace above, but this one is for the calls to managed code.

You only get this stack trace when the event is thrown from managed code. I’m calling a .NET framework function directly so that is all we can see in this example. Generally when you’re looking at a stack trace, you’re looking for where your code stops and the system calls begin.

Working with exceptions

There is more to exceptions than the basic syntax and exception properties.

Catching typed exceptions

You can be selective with the exceptions that you catch. Exceptions have a type and you can specify the type of exception you want to catch.

The exception type is checked for each catch block until one is found that matches your exception. It’s important to realize that exceptions can inherit from other exceptions. In the example above, FileNotFoundException inherits from IOException . So if the IOException was first, then it would get called instead. Only one catch block is invoked even if there are multiple matches.

If we had a System.IO.PathTooLongException , the IOException would match but if we had a InsufficientMemoryException then nothing would catch it and it would propagate up the stack.

Catch multiple types at once

It’s possible to catch multiple exception types with the same catch statement.

Thank you /u/Sheppard_Ra for suggesting this addition.

Throwing typed exceptions

You can throw typed exceptions in PowerShell. Instead of calling throw with a string:

Use an exception accelerator like this:

But you have to specify a message when you do it that way.

You can also create a new instance of an exception to be thrown. The message is optional when you do this because the system has default messages for all built-in exceptions.

If you’re not using PowerShell 5.0 or higher, you must use the older New-Object approach.

By using a typed exception, you (or others) can catch the exception by the type as mentioned in the previous section.

Write-Error -Exception

We can add these typed exceptions to Write-Error and we can still catch the errors by exception type. Use Write-Error like in these examples:

Then we can catch it like this:

The big list of .NET exceptions

I compiled a master list with the help of the Reddit/r/PowerShell community that contains hundreds of .NET exceptions to complement this post.

I start by searching that list for exceptions that feel like they would be a good fit for my situation. You should try to use exceptions in the base System namespace.

Exceptions are objects

If you start using a lot of typed exceptions, remember that they are objects. Different exceptions have different constructors and properties. If we look at the FileNotFoundException documentation for System.IO.FileNotFoundException , we see that we can pass in a message and a file path.

And it has a FileName property that exposes that file path.

You should consult the .NET documentation for other constructors and object properties.

Re-throwing an exception

If all you’re going to do in your catch block is throw the same exception, then don’t catch it. You should only catch an exception that you plan to handle or perform some action when it happens.

There are times where you want to perform an action on an exception but re-throw the exception so something downstream can deal with it. We could write a message or log the problem close to where we discover it but handle the issue further up the stack.

Interestingly enough, we can call throw from within the catch and it re-throws the current exception.

We want to re-throw the exception to preserve the original execution information like source script and line number. If we throw a new exception at this point, it hides where the exception started.

Re-throwing a new exception

If you catch an exception but you want to throw a different one, then you should nest the original exception inside the new one. This allows someone down the stack to access it as the $PSItem.Exception.InnerException .

$PSCmdlet.ThrowTerminatingError()

The one thing that I don’t like about using throw for raw exceptions is that the error message points at the throw statement and indicates that line is where the problem is.

Having the error message tell me that my script is broken because I called throw on line 31 is a bad message for users of your script to see. It doesn’t tell them anything useful.

Dexter Dhami pointed out that I can use ThrowTerminatingError() to correct that.

If we assume that ThrowTerminatingError() was called inside a function called Get-Resource , then this is the error that we would see.

Do you see how it points to the Get-Resource function as the source of the problem? That tells the user something useful.

Because $PSItem is an ErrorRecord , we can also use ThrowTerminatingError this way to re-throw.

This changes the source of the error to the Cmdlet and hide the internals of your function from the users of your Cmdlet.

Try can create terminating errors

Kirk Munro points out that some exceptions are only terminating errors when executed inside a try/catch block. Here is the example he gave me that generates a divide by zero runtime exception.

Then invoke it like this to see it generate the error and still output the message.

But by placing that same code inside a try/catch , we see something else happen.

We see the error become a terminating error and not output the first message. What I don’t like about this one is that you can have this code in a function and it acts differently if someone is using a try/catch .

I have not ran into issues with this myself but it is corner case to be aware of.

$PSCmdlet.ThrowTerminatingError() inside try/catch

One nuance of $PSCmdlet.ThrowTerminatingError() is that it creates a terminating error within your Cmdlet but it turns into a non-terminating error after it leaves your Cmdlet. This leaves the burden on the caller of your function to decide how to handle the error. They can turn it back into a terminating error by using -ErrorAction Stop or calling it from within a try<. >catch <. >.

Public function templates

One last take a way I had with my conversation with Kirk Munro was that he places a try<. >catch <. >around every begin , process and end block in all of his advanced functions. In those generic catch blocks, he has a single line using $PSCmdlet.ThrowTerminatingError($PSItem) to deal with all exceptions leaving his functions.

Because everything is in a try statement within his functions, everything acts consistently. This also gives clean errors to the end user that hides the internal code from the generated error.

I focused on the try/catch aspect of exceptions. But there’s one legacy feature I need to mention before we wrap this up.

A trap is placed in a script or function to catch all exceptions that happen in that scope. When an exception happens, the code in the trap is executed and then the normal code continues. If multiple exceptions happen, then the trap is called over and over.

I personally never adopted this approach but I can see the value in admin or controller scripts that log any and all exceptions, then still continue to execute.

Adding proper exception handling to your scripts not only make them more stable, but also makes it easier for you to troubleshoot those exceptions.

I spent a lot of time talking throw because it is a core concept when talking about exception handling. PowerShell also gave us Write-Error that handles all the situations where you would use throw . So don’t think that you need to be using throw after reading this.

Now that I have taken the time to write about exception handling in this detail, I’m going to switch over to using Write-Error -Stop to generate errors in my code. I’m also going to take Kirk’s advice and make ThrowTerminatingError my goto exception handler for every function.

Источник

Все, что вы хотели знать об исключениях

Обработка ошибок — это лишь часть процесса написания кода. Зачастую можно проверить, выполняются ли условия для ожидаемого поведения. При возникновении непредвиденной ситуации необходимо переключиться на обработку исключений. Вы можете легко обрабатывать исключения, созданные кодом других разработчиков, или создавать собственные исключения, которые смогут обработать другие.

Оригинал этой статьи впервые был опубликован в блоге автора @KevinMarquette. Группа разработчиков PowerShell благодарит Кевина за то, что он поделился с нами этими материалами. Читайте его блог — PowerShellExplained.com.

Базовая терминология

Прежде чем двигаться дальше, необходимо разобраться с основными терминами.

Исключение

Исключение подобно событию, которое создается, когда не удается справиться с проблемой путем обычной обработки ошибок. Примерами проблем, которые приводят к исключениям, могут служить попытки деления числа на ноль и нехватка памяти. Иногда автор кода, который вы используете, создает исключения для определенных проблем в случае их возникновения.

Throw и Catch

Когда происходит исключение, мы говорим, что оно вызвано. Чтобы обработать вызванное исключение, его необходимо перехватить. Если вызывается исключение, которое не перехватывается никакими объектами, выполнение скрипта прекращается.

Стек вызовов

Стек вызовов — это список функций, которые вызывали друг друга. При вызове функции она добавляется в стек или вверх списка. При выходе из функции или возврате ею значения она удаляется из стека.

При вызове исключения выполняется проверка этого стека вызовов, чтобы обработчик исключений мог его перехватить.

Неустранимые и устранимые ошибки

Исключение обычно является неустранимой ошибкой. Вызванное исключение либо перехватывается, либо завершает текущее выполнение. По умолчанию устранимая ошибка генерируется Write-Error и приводит к добавлению ошибки в выходной поток без вызова исключения.

Обращаю внимание на это потому, что Write-Error и другие устранимые ошибки не активируют catch .

Игнорирование исключения

Это ситуация, когда ошибка перехватывается только для того, чтобы ее подавить. Используйте эту возможность с осторожностью, поскольку это может существенно усложнить устранение неполадок.

Основной синтаксис команды

Ниже приведен краткий обзор основного синтаксиса обработки исключений, используемого в PowerShell.

Ключевое слово throw

Чтобы вызвать собственное событие исключения, воспользуйтесь ключевым словом throw .

Это приведет к созданию исключения во время выполнения, которое является неустранимой ошибкой. Оно обрабатывается с помощью catch в вызывающей функции или приводит к выходу из скрипта с сообщением следующего вида.

Параметр -ErrorAction Stop командлета Write-Error

Я упоминал, что по умолчанию Write-Error не вызывает неустранимую ошибку. Если указать -ErrorAction Stop , то Write-Error создает неустранимую ошибку, которую можно обработать с помощью catch .

Благодарю Ли Дейли за напоминание о том, что -ErrorAction Stop можно использовать таким образом.

Параметр -ErrorAction Stop в командлете

Если указать -ErrorAction Stop в любой расширенной функции или командлете, все инструкции Write-Error будут преобразованы в неустранимые ошибки, которые приводят к остановке выполнения или могут быть обработаны с помощью catch .

Try и Catch

Принцип обработки исключений в PowerShell (и многих других языках) состоит в том, что сначала к разделу кода применяется try , а если происходит ошибка, к нему применяется catch . Приведем краткий пример.

Скрипт catch выполняется только в том случае, если произошла неустранимая ошибка. Если try выполняется правильно, catch пропускается. Можно получить доступ к информации об исключении в блоке catch с помощью переменной $_ .

Try и Finally

Иногда ошибку обрабатывать не требуется, но необходимо выполнить определенный код в зависимости от того, было ли создано исключение. Именно это и делает скрипт finally .

Взгляните на этот пример.

Всякий раз, когда вы открываете ресурс или подключаетесь к нему, его следует закрыть. Если ExecuteNonQuery() вызывает исключение, соединение не закрывается. Вот тот же код в блоке try/finally .

В этом примере соединение закрывается при возникновении ошибки. Оно также закрывается при отсутствии ошибок. При этом всякий раз выполняется скрипт finally .

Так как исключение не перехватывается, оно по-прежнему распространяет в стек вызовов.

Try, catch и finally

Вполне допустимо использовать catch и finally вместе. В большинстве случаев используется либо один, либо другой скрипт, но вам могут встретиться сценарии, в которых используются они оба.

$PSItem

Теперь, когда мы разобрались с основами, можно изучить вопрос подробнее.

В блоке catch существует автоматическая переменная ( $PSItem или $_ ) типа ErrorRecord , содержащая сведения об исключении. Ниже приведен краткий обзор некоторых ключевых свойств.

В этих примерах для создания такого исключения я использовал недопустимый путь в ReadAllText .

PSItem.ToString()

Этот метод позволяет получить максимально понятное сообщение, которое можно использовать при ведении журнала и выводе общего результата. ToString() вызывается автоматически, если в строку помещена переменная $PSItem .

$PSItem.InvocationInfo

Это свойство содержит дополнительные сведения, собираемые PowerShell о функции или скрипте, которые вызвали исключение. Ниже приведено свойство InvocationInfo из примера созданного мною исключения.

Здесь приведены важные сведения: имя ScriptName , строка кода Line и номер строки ScriptLineNumber , из которой инициирован вызов.

$PSItem.ScriptStackTrace

Это свойство показывает порядок вызовов функций, ведущих к коду, в котором создано исключение.

Я выполняю вызовы функций в пределах одного скрипта, но таким же образом можно отслеживать функции при использовании нескольких скриптов.

$PSItem.Exception

Это, собственно, и есть вызванное исключение.

$PSItem.Exception.Message

Это общее сообщение, которое описывает исключение и служит хорошей отправной точкой при устранении неполадок. Для большинства исключений предусмотрены сообщения по умолчанию, но при необходимости их можно настроить по своему усмотрению.

Это еще одно сообщение, возвращаемое при вызове $PSItem.ToString() , если для ErrorRecord не задан другой его вариант.

$PSItem.Exception.InnerException

Исключения могут содержать внутренние исключения. Это часто случается, когда вызываемый код перехватывает одно исключение и вызывает другое. Исходное исключение помещается в новое исключение.

Я вернусь к этому вопросу позже, когда буду рассказывать о повторном вызове исключений.

$PSItem.Exception.StackTrace

Это свойство StackTrace для исключения. Я продемонстрировал принцип работы свойства ScriptStackTrace выше, но это предназначено для вызовов управляемого кода.

Эта трассировка стека выполняется только в случае, если событие вызвано из управляемого кода. Я вызываю функцию .NET Framework напрямую, так что это все, что можно увидеть в этом примере. Как правило, трассировка стека просматривается, чтобы найти место остановки кода и начало системных вызовов.

Работа с исключениями

Для работы с исключениями недостаточно базового синтаксиса и основных свойств.

Перехват типизированных исключений

Исключения можно перехватывать избирательно. Исключения имеют тип, задав который можно перехватить только исключения определенного типа.

Каждый блок catch проверяется на наличие исключения заданного типа, пока не будет найден тот, в котором оно создается. Важно понимать, что исключения могут наследоваться от других исключений. В приведенном выше примере FileNotFoundException наследуется от IOException . Поэтому, если исключение IOException было первым, будет вызвано именно оно. Даже если совпадений несколько, вызывается только один блок catch.

При наличии исключения System.IO.PathTooLongException исключение IOException распознается как совпадение, но при наличии исключения InsufficientMemoryException перехватывать его нечем, поэтому оно распространится по стеку.

Одновременный перехват нескольких типов

С помощью одной инструкции catch можно перехватывать несколько типов исключений одновременно.

Благодарю /u/Sheppard_Ra за предложение добавить этот раздел.

Вызов типизированных исключений

В PowerShell можно вызывать типизированные исключения. Вместо вызова throw со строкой:

используйте ускоритель исключений следующим образом:

Но в таком случае необходимо указать сообщение.

Можно также создать новый экземпляр исключения для вызова. При этом сообщение является необязательным, так как в системе предусмотрены сообщения по умолчанию для всех встроенных исключений.

Если вы не используете PowerShell 5.0 или более поздних версий, необходимо использовать устаревший подход с применением New-Object .

Как упоминалось в предыдущем разделе, используя типизированное исключение, вы (или другие пользователи) можете перехватывать исключения по типу.

Параметр -Exception командлета Write-Error

Эти типизированные исключения можно добавить в Write-Error и при этом перехватывать исключения с помощью catch по их типу. Используйте командлет Write-Error , как показано в следующих примерах.

Теперь исключение можно перехватить следующим образом.

Большой список исключений .NET

В дополнение к этой публикации я (при помощи Сообщество Reddit/r/PowerShell) составил основной список, который содержит сотни исключений .NET.

Для начала я ищу в этом списке исключения, которые хорошо подходят для моей ситуации. Следует попытаться использовать исключения в базовом пространстве имен System .

Исключения как объекты

При использовании большого числа типизированных исключений следует помнить, что они являются объектами. Различные исключения имеют разные конструкторы и свойства. В документации FileNotFoundException для System.IO.FileNotFoundException указано, что для этого исключения можно передать сообщение и путь к файлу.

У него есть свойство FileName , которое предоставляет путь к этому файлу.

Сведения о других конструкторах и свойствах объектов см. в документации по Документация по .NET.

Повторный вызов исключения

Если блок catch используется только для вызова того же исключения с помощью throw , перехватывать его с помощью catch не стоит. Перехватывать с помощью catch следует только исключение, которое планируется обработать или использовать для выполнения какого-либо действия.

Бывают случаи, когда необходимо выполнить действие с исключением, но при этом вызывать его повторно, чтобы его можно было обработать на более низком уровне. Мы можем написать сообщение или записать проблему в журнал ближе к месту обнаружения, а обработать эту проблему на другом уровне стека.

Интересно, что throw можно вызвать из catch , и тогда текущее исключение будет вызвано повторно.

Исключение создается повторно, чтобы сохранить исходные сведения о выполнении, например исходный скрипт и номер строки. Если на этом этапе вызывается новое исключение, оно скрывает первоначальное место его возникновения.

Повторный вызов нового исключения

Если вы перехватили исключение, но хотите вызвать другое, следует вложить исходное исключение в новое. Это позволяет объекту на более низком уровне стека получить к нему доступ как к $PSItem.Exception.InnerException .

$PSCmdlet.ThrowTerminatingError()

Единственное, что мне не нравится в использовании throw для необработанных исключений, заключается в том, что в качестве причины ошибки в сообщении об ошибке указывается инструкция throw и номер проблемной строки.

Если сообщение об ошибке сообщает о том, что скрипт работает неправильно из-за вызова throw в строке 31, оно не подходит для отображения пользователям скрипта. Оно не сообщает им ничего полезного.

Декстер Дхами отметил, что для устранения этой проблемы я могу использовать ThrowTerminatingError() .

Если предположить, что метод ThrowTerminatingError() вызван внутри функции с именем Get-Resource , сообщение об ошибке будет таким, как показано ниже.

Вы заметили, что в качестве источника проблемы в нем указана функция Get-Resource ? Теперь пользователь узнает что-то полезное.

Так как значением $PSItem является ErrorRecord , можно таким же образом использовать ThrowTerminatingError для повторного вызова.

При этом источник ошибки изменится на командлет, а внутренние данные о функции будут скрыты от его пользователей.

Try как источник неустранимой ошибки

Кирк Манро указывает, что некоторые исключения являются неустранимыми ошибками только при выполнении внутри блока try/catch . В этом предоставленном им примере исключение во время выполнения вызывается вследствие деления на ноль.

Вызовем его теперь следующим образом, чтобы код содержал ошибку, но при этом выводилось сообщение.

Однако если поместить этот же код в try/catch , то происходит нечто иное.

Ошибка становится неустранимой, а первое сообщение не выводится. Не нравится мне в этом то, что при наличии такого кода в функции поведение становится другим, если использовать try/catch .

Сам я не сталкивался с такой проблемой, но это крайний случай, о котором следует помнить.

Метод $PSCmdlet.ThrowTerminatingError() в try/catch

Одна из особенностей $PSCmdlet.ThrowTerminatingError() заключается в том, что в командлете этот метод вызывает неустранимую ошибку, но после выхода из него ошибка становится устранимой. Из-за этого тому, кто вызывает функцию, приходится решать, как следует обрабатывать такую ошибку. В этом случае можно превратить ее снова в неустранимую ошибку с помощью -ErrorAction Stop или воспользоваться вызовом из try<. >catch <. >.

Шаблоны общих функций

В одной из последних бесед с Кирком Манро мы говорили о том, что он помещает каждый блок begin , process и end во всех своих расширенных функциях в блок try<. >catch <. >. В этих универсальных блоках catch у него есть одна строка с методом $PSCmdlet.ThrowTerminatingError($PSItem) для обработки всех исключений, вызываемых его функциями.

Поскольку в его функциях все находится в операторе try , весь код работает единообразно. Это также позволяет выводить для пользователя понятные сообщения об ошибках, в которых скрыты данные о внутреннем коде.

Ключевое слово trap

Я уделил много внимания особенностям блока try/catch . Однако прежде чем закрывать эту тему, нужно упомянуть об одной устаревшей функции.

Ключевое слово trap помещается в скрипт или функцию для перехвата всех исключений, возникающих в соответствующей области. При возникновении исключения выполняется код в ловушке trap , а затем продолжается выполнение стандартного кода. Если происходит несколько исключений, ловушка вызывается снова и снова.

Я лично никогда не применял этот подход. Однако, судя по скриптам администраторов и контроллеров, которые заносят в журнал абсолютно все исключения, а затем продолжают выполнение, могу сказать, что в нем есть своя польза.

Заключительное слово

Добавление соответствующей обработки исключений в скрипты не только делает эти скрипты более стабильными, но и упрощает устранение таких исключений.

Я уделил так много внимания throw , так как это основное понятие, которым мы оперируем при обсуждении обработки исключений. В PowerShell также предоставляется командлет Write-Error , справляющийся со всеми ситуациями, в которых следовало бы использовать throw . Так что изложенное в этой статье вовсе не означает, что вам обязательно необходимо использовать throw .

Теперь, когда я подробно рассказал об обработке исключений, я собираюсь заняться вопросом использования Write-Error -Stop для создания ошибок в коде. Я также собираюсь воспользоваться советом Кирка и перейти на использование ThrowTerminatingError в качестве обработчика исключений для каждой функции.

Источник

Controlling Error Reporting Behavior and Intercepting Errors

This section briefly demonstrates how to use each of PowerShell’s statements, variables and parameters that are related to the reporting or handling of errors.

The $Error Variable

$Error is an automatic global variable in PowerShell which always contains an ArrayList of zero or more ErrorRecord objects. As new errors occur, they are added to the beginning of this list, so you can always get information about the most recent error by looking at $Error[0]. Both Terminating and Non-Terminating errors will be contained in this list.

Aside from accessing the objects in the list with array syntax, there are two other common tasks that are performed with the $Error variable: you can check how many errors are currently in the list by checking the $Error.Count property, and you can remove all errors from the list with the $Error.Clear() method. For example:

Figure 2.1: Using $Error to access error information, check the count, and clear the list.

If you’re planning to make use of the $Error variable in your scripts, keep in mind that it may already contain information about errors that happened in the current PowerShell session before your script was even started. Also, some people consider it a bad practice to clear the $Error variable inside a script; since it’s a variable global to the PowerShell session, the person that called your script might want to review the contents of $Error after it completes.

ErrorVariable

The ErrorVariable common parameter provides you with an alternative to using the built-in $Error collection. Unlike $Error, your ErrorVariable will only contain errors that occurred from the command you’re calling, instead of potentially having errors from elsewhere in the current PowerShell session. This also avoids having to clear the $Error list (and the breach of etiquette that entails.)

When using ErrorVariable, if you want to append to the error variable instead of overwriting it, place a + sign in front of the variable’s name. Note that you do not use a dollar sign when you pass a variable name to the ErrorVariable parameter, but you do use the dollar sign later when you check its value.

The variable assigned to the ErrorVariable parameter will never be null; if no errors occurred, it will contain an ArrayList object with a Count of 0, as seen in figure 2.2:

Figure 2.2: Demonstrating the use of the ErrorVariable parameter.

$MaximumErrorCount

By default, the $Error variable can only contain a maximum of 256 errors before it starts to lose the oldest ones on the list. You can adjust this behavior by modifying the $MaximumErrorCount variable.

ErrorAction and $ErrorActionPreference

There are several ways you can control PowerShell’s handling / reporting behavior. The ones you will probably use most often are the ErrorAction common parameter and the $ErrorActionPreference variable.

The ErrorAction parameter can be passed to any Cmdlet or Advanced Function, and can have one of the following values: Continue (the default), SilentlyContinue, Stop, Inquire, Ignore (only in PowerShell 3.0 or later), and Suspend (only for workflows; will not be discussed further here.) It affects how the Cmdlet behaves when it produces a non-terminating error.

- The default value of Continue causes the error to be written to the Error stream and added to the $Error variable, and then the Cmdlet continues processing.

- A value of SilentlyContinue only adds the error to the $Error variable; it does not write the error to the Error stream (so it will not be displayed at the console).

- A value of Ignore both suppresses the error message and does not add it to the $Error variable. This option was added with PowerShell 3.0.

- A value of Stop causes non-terminating errors to be treated as terminating errors instead, immediately halting the Cmdlet’s execution. This also enables you to intercept those errors in a Try/Catch or Trap statement, as described later in this section.

- A value of Inquire causes PowerShell to ask the user whether the script should continue or not when an error occurs.

The $ErrorActionPreference variable can be used just like the ErrorAction parameter, with a couple of exceptions: you cannot set $ErrorActionPreference to either Ignore or Suspend. Also, $ErrorActionPreference affects your current scope in addition to any child commands you call; this subtle difference has the effect of allowing you to control the behavior of errors that are produced by .NET methods, or other causes such as PowerShell encountering a «command not found» error.

Figure 2.3 demonstrates the effects of the three most commonly used $ErrorActionPreference settings.

Figure 2.3: Behavior of $ErrorActionPreference

Try/Catch/Finally

The Try/Catch/Finally statements, added in PowerShell 2.0, are the preferred way of handling terminating errors. They cannot be used to handle non-terminating errors, unless you force those errors to become terminating errors with ErrorAction or $ErrorActionPreference set to Stop.

To use Try/Catch/Finally, you start with the «Try» keyword followed by a single PowerShell script block. Following the Try block can be any number of Catch blocks, and either zero or one Finally block. There must be a minimum of either one Catch block or one Finally block; a Try block cannot be used by itself.

The code inside the Try block is executed until it is either complete, or a terminating error occurs. If a terminating error does occur, execution of the code in the Try block stops. PowerShell writes the terminating error to the $Error list, and looks for a matching Catch block (either in the current scope, or in any parent scopes.) If no Catch block exists to handle the error, PowerShell writes the error to the Error stream, the same thing it would have done if the error had occurred outside of a Try block.

Catch blocks can be written to only catch specific types of Exceptions, or to catch all terminating errors. If you do define multiple catch blocks for different exception types, be sure to place the more specific blocks at the top of the list; PowerShell searches catch blocks from top to bottom, and stops as soon as it finds one that is a match.

If a Finally block is included, its code is executed after both the Try and Catch blocks are complete, regardless of whether an error occurred or not. This is primarily intended to perform cleanup of resources (freeing up memory, calling objects’ Close() or Dispose() methods, etc.)

Figure 2.4 demonstrates the use of a Try/Catch/Finally block:

Figure 2.4: Example of using try/catch/finally.

Notice that «Statement after the error» is never displayed, because a terminating error occurred on the previous line. Because the error was based on an IOException, that Catch block was executed, instead of the general «catch-all» block below it. Afterward, the Finally executes and changes the value of $testVariable.

Also notice that while the Catch block specified a type of [System.IO.IOException], the actual exception type was, in this case, [System.IO.DirectoryNotFoundException]. This works because DirectoryNotFoundException is inherited from IOException, the same way all exceptions share the same base type of System.Exception. You can see this in figure 2.5:

Figure 2.5: Showing that IOException is the Base type for DirectoryNotFoundException

Trap

Trap statements were the method of handling terminating errors in PowerShell 1.0. As with Try/Catch/Finally, the Trap statement has no effect on non-terminating errors.

Trap is a bit awkward to use, as it applies to the entire scope where it is defined (and child scopes as well), rather than having the error handling logic kept close to the code that might produce the error the way it is when you use Try/Catch/Finally. For those of you familiar with Visual Basic, Trap is a lot like «On Error Goto». For that reason, Trap statements don’t see a lot of use in modern PowerShell scripts, and I didn’t include them in the test scripts or analysis in Section 3 of this ebook.

For the sake of completeness, here’s an example of how to use Trap:

Figure 2.6: Use of the Trap statement

As you can see, Trap blocks are defined much the same way as Catch blocks, optionally specifying an Exception type. Trap blocks may optionally end with either a Break or Continue statement. If you don’t use either of those, the error is written to the Error stream, and the current script block continues with the next line after the error. If you use Break, as seen in figure 2.5, the error is written to the Error stream, and the rest of the current script block is not executed. If you use Continue, the error is not written to the error stream, and the script block continues execution with the next statement.

The $LASTEXITCODE Variable

When you call an executable program instead of a PowerShell Cmdlet, Script or Function, the $LASTEXITCODE variable automatically contains the process’s exit code. Most processes use the convention of setting an exit code of zero when the code finishes successfully, and non-zero if an error occurred, but this is not guaranteed. It’s up to the developer of the executable to determine what its exit codes mean.

Note that the $LASTEXITCODE variable is only set when you call an executable directly, or via PowerShell’s call operator (&) or the Invoke-Expression cmdlet. If you use another method such as Start-Process or WMI to launch the executable, they have their own ways of communicating the exit code to you, and will not affect the current value of $LASTEXITCODE.

Figure 2.7: Using $LASTEXITCODE.

The $? Variable

The $? variable is a Boolean value that is automatically set after each PowerShell statement or pipeline finishes execution. It should be set to True if the previous command was successful, and False if there was an error.

When the previous command was a PowerShell statement, $? will be set to False if any errors occurred (even if ErrorAction was set to SilentlyContinue or Ignore).

If the previous command was a call to a native exe, $? will be set to False if the $LASTEXITCODE variable does not equal zero. If the $LASTEXITCODE variable equals zero, then in theory $? should be set to True. However, if the native command writes something to the standard error stream then $? could be set to False even if $LASTEXITCODE equals zero. For example, the PowerShell ISE will create and append error objects to $Error for standard error stream output and consequently $? will be False regardless of the value of $LASTEXITCODE. Redirecting the standard error stream into a file will result in a similar behavior even when the PowerShell host is the regular console. So it is probably best to test the behavior in your specific environment if you want to rely on $? being set correctly to True.

Just be aware that the value of this variable is reset after every statement. You must check its value immediately after the command you’re interested in, or it will be overwritten (probably to True). Figure 2.8 demonstrates this behavior. The first time $? is checked, it is set to False, because the Get-Item encountered an error. The second time $? was checked, it was set to True, because the previous command was successful; in this case, the previous command was «$?» from the first time the variable’s value was displayed.

Figure 2.8: Demonstrating behavior of the $? variable.

The $? variable doesn’t give you any details about what error occurred; it’s simply a flag that something went wrong. In the case of calling executable programs, you need to be sure that they return an exit code of 0 to indicate success and non-zero to indicate an error before you can rely on the contents of $?.

Summary

That covers all of the techniques you can use to either control error reporting or intercept and handle errors in a PowerShell script. To summarize:

- To intercept and react to non-terminating errors, you check the contents of either the automatic $Error collection, or the variable you specified as the ErrorVariable. This is done after the command completes; you cannot react to a non-terminating error before the Cmdlet or Function finishes its work.

- To intercept and react to terminating errors, you use either Try/Catch/Finally (preferred), or Trap (old and not used much now.) Both of these constructs allow you to specify different script blocks to react to different types of Exceptions.

- Using the ErrorAction parameter, you can change how PowerShell cmdlets and functions report non-terminating errors. Setting this to Stop causes them to become terminating errors instead, which can be intercepted with Try/Catch/Finally or Trap.

- $ErrorActionPreference works like ErrorAction, except it can also affect PowerShell’s behavior when a terminating error occurs, even if those errors came from a .NET method instead of a cmdlet.

- $LASTEXITCODE contains the exit code of external executables. An exit code of zero usually indicates success, but that’s up to the author of the program.

- $? can tell you whether the previous command was successful, though you have to be careful about using it with external commands. If they don’t follow the convention of using an exit code of zero as an indicator of success or if they write to the standard error stream then the resulting value in $? may not be what you expect. You also need to make sure you check the contents of $? immediately after the command you are interested in.

There are a few different kinds of errors in PowerShell, and it can be a little bit of a minefield on occasion.

There are always two sides to consider, too: how you write code that creates errors, and how you handle those errors in your own code.

Let’s have a look at some ways to effectively utilise the different kinds of errors you can work with in PowerShell, and how to handle them.

Different Types of Errors

Terminating Errors

Terminating errors are mostly an «exactly what it sounds like» package in general use.

They’re very similar to C#’s Exception system, although PowerShell uses ErrorRecord as its base error object.

Their common characteristics are as follows:

- Trigger

try/catchblocks - Return control to the caller, along with the exception, if they’re not handled using a try/catch block.

There are a couple different ways to get a terminating error in PowerShell, and each has its own small differences that make them more useful in a tricky situation.

Throw

First is your typical throw statement, which simply takes an exception message as its only input.

throw "Something went wrong"

throw creates an exception and an ErrorRecord (PowerShell’s more detailed version of an exception) in a single, simple statement, and wraps them together.

Its exceptions display the entered error message, a generic RuntimeException, and the errorID matches the entered exception message.

The line number and position displayed from a throw error message point back to the throw statement itself.

throw exceptions are affected by -ErrorAction parameters of their advanced functions.

throw should generally be used for simple runtime errors, where you need to halt execution, but typically only if you plan to catch it yourself later.

There is no guarantee a user will not elect to simply ignore your error with -ErrorAction Ignore and continue with their lives if it is passed up from your functions.

ThrowTerminatingError()

Next, we have a more advanced version of the throw statement. ThrowTerminatingError() is a method that comes directly from PowerShell’s PSCmdlet .NET class.

It is accessible only in advanced functions via the $PSCmdlet variable.

using namespace System.Management.Automation;

$Exception = [Exception]::new("error message")

$ErrorRecord = [System.Management.Automation.ErrorRecord]::new(

$Exception,

"errorID",

[System.Management.Automation.ErrorCategory]::NotSpecified,

$TargetObject # usually the object that triggered the error, if possible

)

$PSCmdlet.ThrowTerminatingError($ErrorRecord)

As you can see, these require a little more manual labor.

You can bypass some of this by deliberately using the throw statement and then later catching the generated ErrorRecord to pass it into the ThrowTerminatingError() method directly.

This saves a decent amount of the code involved, and offloads the work to PowerShell’s engine instead.

However, this will still involve essentially the same work being done, without necessarily giving you a chance to specify the finer details of the error record.

ThrowTerminatingError() creates a terminating error (as the name implies), however unlike throw its errors are unaffected by -ErrorAction parameters applied to the parent function.

It will also never reveal the code around it.

When you see an error thrown via this method, it will always display only the line where the command was called, never the code within the command that actually threw the error.

ThrowTerminatingError() should generally be used for serious errors, where continuing to process in spite of the error may lead to corrupted data, and you want any specified -ErrorAction parameter to be ignored.

Non-Terminating Errors

Non-terminating errors are PowerShell’s concession demanded by the fact that it is a shell that supports pipelines.

Not all errors warrant halting all ongoing actions, and only need to inform the user that a minor error occurred, but continue processing the remainder of the items.

Unlike terminating errors, non-terminating errors:

- Do not trigger

try/catchblocks. - Do not affect the script’s control flow.

Write-Error

Write-Error is a bit like the non-terminating version of throw, albeit more versatile.

It too creates a complete ErrorRecord, which has a NotSpecified category and some predefined Exception and ErrorCode properties that both refer to Write-Error.

This is a very simple and effective way to write a non-terminating error, but it is somewhat limited in its use.

While you can override its predefined default exception type, error code, and essentially everything about the generated ErrorRecord, Write-Error is similar to throw in that it too points directly back to the line where Write-Error itself was called.

This can often make the error display very unclear, which is rarely a good thing.

Write-Error is a great way to emit straightforward, non-terminating errors, but its tendency to muddy the error display makes it difficult to recommend for any specific uses.

However, as it is itself a cmdlet, it is also possible to make it create terminating errors as well, by using the -ErrorAction Stop parameter argument.

WriteError()

WriteError() is the non-terminating cousin of ThrowTerminatingError(), and is also available as one of the members of the automatic $PSCmdlet variable in advanced functions.

It behaves similarly to its cousin in that it too hides the code that implements it and instead points back to the point where its parent function was called as the source point of the error.

This is often preferable when dealing with expected errors such as garbled input or arguments, or simple «could not find the requested item» errors in some cases.

$Exception = [Exception]::new("error message")

$ErrorRecord = [System.Management.Automation.ErrorRecord]::new(

$Exception,

"errorID",

[System.Management.Automation.ErrorCategory]::NotSpecified,

$TargetObject # usually the object that triggered the error, if possible

)

$PSCmdlet.WriteError($ErrorRecord)

Emit Errors Responsibly

There are no true hard-and-fast rules here.

If one solution works especially well for what you happen to be putting together, don’t let me deter you.

However, I would urge you to consider both the impact to your users as well as yourself or your team before selecting a single-minded approach to error creation.

Not all error scenarios are created equal, so it’s very rare that I would recommend using one type over all others.

WriteError() is generally preferred over its cmdlet form Write-Error, because it offers more control over how you emit the error.

Both tend to be used for expected and technically avoidable errors that occur, but the $PSCmdlet method has the additional benefit of not divulging implementation details unnecessarily.

If you expect the error to occur sometimes, I would generally advise using WriteError() unless the error’s presence significantly impairs your cmdlet’s ability to process the rest of its input, in which case I would use ThrowTerminatingError().

throw is generally nice as a quick way to trigger a try/catch block in your own code, but I would also recommend using it for: those truly unexpected errors, that last-ditch catch clause after several more specific catch blocks have been put in place and bypassed.

At this point, a final ending catch block that simply triggers a throw $_ call to re-throw the caught exception into the parent scope and quickly pass execution back to the caller.

It’s a very quick and very effective way to have the error be noticed, but should usually be kept internal to the function more than anything else, except in the last scenario mentioned.

Use of Write-Error -ErrorAction Stop may potentially also be substituted for that purpose if you personally prefer.

Thanks for reading!

Have you ever run a script or a PowerShell cmdlet and get confronted with a screaming wall of text – in red – like the one shown below?

Not a reader? Watch this related video tutorial!

Not seeing the video? Make sure your ad blocker is disabled.

Errors can become overwhelming and confusing. And most of all, errors are often hard to read, which makes determining what and where the script went wrong near impossible.

Luckily, you have some options in PowerShell to make this better through error handling. Using error handling, errors can be filtered and displayed in such a way that it’s easier to make sense of. And, understanding the error makes it easy to add more logic to error handling.

In this article, you will learn about errors in PowerShell and how they can be intercepted to perform error handling using the PowerShell Try Catch blocks (and finally blocks).

Understanding How Errors Work in PowerShell

Before diving into error handling, let’s first cover a few concepts around errors in PowerShell. Understanding errors can lead to better error handling strategies.

The $Error Automatic Variable

In PowerShell, there are a lot of automatic variables, and one of them is the $Error automatic variable. PowerShell uses the $Error variable to store all errors that are encountered in the session. The $Error variable is an array of errors sorted by most recent.

When you first open a PowerShell session, the $Error variable is empty. You can check it so by calling the $Error variable.

As you can see, the $Error variable starts off empty. But, once an error is generated, the error will be added and stored into the $Error variable.

In the example below, the error is generated by deliberately getting a service name that does not exist.

PS> Get-Service xyz

PS> $Error

PS> $Error.Count

As you can see from the output above, the generated error was added to the $Error variable.

The $Error variable contains a collection of errors generated in the PowerShell session. Each error can be access by calling its array position. The latest error will always be at index 0.

For example, the latest error can be retrieved using

$Error[0].

The $Error Object Properties

Since everything in PowerShell is an object, the $Error variable is an object, and objects have properties. By piping the $Error variable to the Get-Member cmdlet, you should see the list of the properties available.

To determine the reason for the error, you can view the content of the InvocationInfo property using the command below.

Now, you could do the same with the other properties and discover what other information you can find!

Terminating Errors

Terminating errors stop the execution flow when it is encountered by PowerShell vs non-terminating errors. There are several ways a terminating error can occur. One example is when you call a cmdlet with a parameter that does not exist.

As you’ll from the screenshot below, when the command Get-Process notepad runs, the command is valid, and the details of the notepad process are displayed.

But, when a parameter that does not exist is used like Get-Process notepad -handle 251, the cmdlet displays an error that the handle parameter is not valid. Then, the cmdlet exits without showing the details of the notepad process.

Non-Terminating Errors

Non-terminating errors are errors that do not stop the execution of the script or command. For example, check out the code below. This code gets the list of file names from the fileslist.txt file. Then, the script goes through each file name, read the contents of each file, and outputs it on the screen.

$file_list = Get-Content .filelist.txt

foreach ($file in $file_list) {

Write-Output "Reading file $file"

Get-Content $file

}The contents of the filelist.txt file are the file names shows in the list below.

File_1.log

File_2.log

File_3.log

File_4.log

File_5.log

File_6.log

File_7.log

File_8.log

File_9.log

File_10.logBut what if File_6.log didn’t actually exist? When you run the code, you’d expect an error will happen because the script cannot find the File_6.log. You’ll see a similar output shown below.

As you can see from the screenshot of the result above, the script was able to read the first five files in the list, but when it tried to read the file File_6.txt, an error is returned. The script then continued to read the rest of the files before exiting. It did not terminate.

The $ErrorActionPreference Variable

So far, you’ve learned about the terminating and non-terminating errors and how they differ from each other. But, did you know that a non-terminating error can be forced to be treated as a terminating error?

PowerShell has a concept called preference variables. These variables are used to change how PowerShell behaves many different ways. One of these variables is called $ErrorActionPreference.

The $ErrorActionPreference variable is used to change the way PowerShell treats non-terminating errors. By default, the $ErrorActionPreference value is set to Continue. Changing the value of the $ErrorActionPreference variable to STOPforces PowerShell to treat all errors as terminating errors.

Use the code below to change the $ErrorActionPreference value.

$ErrorActionPreference = "STOP"To learn more about other valid $ErrorActionPreference variable values, visit PowerShell ErrorActionPreference.

Now, refer back to the example used in the Non-Terminating Errors section in this article. The script can modified to include the change in $ErrorActionPreference like the code shown below:

# Set the $ErrorActionPreference value to STOP

$ErrorActionPreference = "STOP"

$file_list = Get-Content .filelist.txt

foreach ($file in $file_list) {

Write-Output "Reading file $file"

Get-Content $file

}Running the modified code above will behave differently than before when the $ErrorActionPreference value is set to the default value of Continue.

$ErrorActionPreference variableAs you can see from the screenshot of the result above, the script was able to read the first five files in the list, but when it tried to read the file File_6.txt, an error is returned because the file was not found. Then, the script terminated, and the rest of the files are not read.

The

$ErrorActionPreferencevalue is only valid in the current PowerShell session. It resets to the default value once a new PowerShell session is started.

The ErrorAction Common Parameter

If the $ErrorActionPreference value is applied to the PowerShell session, the ErrorAction parameter applies to any cmdlet that supports common parameters. The ErrorAction parameter accepts the same values that the $ErrorActionPreference variable does.

The ErrorAction parameter value takes precedence over the $ErrorActionPreference value.

Let’s go back and use the same code in the previous example. But, this time, the ErrorAction parameter is added to the Get-Content line.

# Set the $ErrorActionPreference value to default (CONTINUE)

$ErrorActionPreference = "CONTINUE"

$file_list = Get-Content .filelist.txt

foreach ($file in $file_list) {

Write-Output "Reading file $file"

# Use the -ErrorAction common parameter

Get-Content $file -ErrorAction STOP

}After running the modified code, you’ll see that even though the $ErrorActionPreference is set to Continue, the script still terminated once it encountered an error. The script terminated because the PowerShell ErrorAction parameter value in Get-Content is set to STOP.

ErrorAction parameterUsing PowerShell Try Catch Blocks

At this point, you’ve learned about PowerShell errors and how the $ErrorActionPreference variable and PowerShell ErrorAction parameters work. Now, it’s time you learn about the good stuff – the PowerShell Try Catch Finally blocks.

PowerShell try catch blocks (and optional finally block) are a way to cast a net around a piece of code and catch any errors that return.

The code below shows the syntax of the Try statement.

try {

<statement list>

}

catch [[<error type>][',' <error type>]*]{

<statement list>

}

finally {

<statement list>

}The Try block contains the code that you want PowerShell to “try” and monitor for errors. If the code in the Try block encounters an error, the error is added to the $Error variable and then passed to the Catch block.

The Catch block contains the actions to execute when it receives an error from the Try block. There can be multiple Catch blocks in a Try statement.

The Finally block contains that code that will at the end of the Try statement. This block runs whether or not an error was uncounted.

Catching Non-Specific Errors (Catch-All) with PowerShell ErrorAction

A simple Try statement contains a Try and a Catch block. The Finally block is optional.

For example, to catch a non-specific exception, the Catch parameter should be empty. The example code below is using the same script that was used in the The $ErrorActionPreference Variable section but modified to use the Try Catch blocks.

As you can see from the code below, this time, the foreach statement is enclosed inside the Try block. Then, a Catch block contains the code to display the string An Error Occurred if an error happened. The code in the Finally block just clears the $Error variable.

$file_list = Get-Content .filelist.txt

try {

foreach ($file in $file_list) {

Write-Output "Reading file $file"

Get-Content $file -ErrorAction STOP

}

}

catch {

Write-Host "An Error Occured" -ForegroundColor RED

}

finally {

$Error.Clear()

}The code above, after running in PowerShell, will give you this output shown below.

The output above shows that the script encountered an error, ran the code inside the Catch block, and then terminated.

The error was handled, which was the point of error handling. However, the error displayed was too generic. To show a more descriptive error, you could access the Exception property of the error that was passed by the Try block.

The code below is modified, specifically the code inside the Catch block, to display the exception message from the current error that was passed down the pipeline – $PSItem.Exception.Message

$file_list = Get-Content .filelist.txt

try {

foreach ($file in $file_list) {

Write-Output "Reading file $file"

Get-Content $file -ErrorAction STOP

}

}

catch {

Write-Host $PSItem.Exception.Message -ForegroundColor RED

}

finally {

$Error.Clear()

}This time, when the modified code above is run, the message displayed is a lot more descriptive.

Catching Specific Errors

There are times when a catch-all error handling is not the most appropriate approach. Perhaps, you want your script to perform an action that is dependent on the type of error that is encountered.

How do you determine the error type? By checking the TypeName value of the Exception property of the last error. For example, to find the error type from the previous example, use this command:

$Error[0].Exception | Get-MemberThe result of the code above would look like the screenshot below. As you can see, the TypeName value is displayed – System.Management.Automation.ItemNotFoundException.

Now that you know the error type that you need to intercept, modify the code to catch it specifically. As you see from the modified code below, there are now two Catch blocks. The first Catch block intercepts a specific type of error (System.Management.Automation.ItemNotFoundException). In contrast, the second Catch block contains the generic, catch-all error message.

$file_list = Get-Content .filelist.txt

try {

foreach ($file in $file_list) {

Write-Output "Reading file $file"

Get-Content $file -ErrorAction STOP

}

}

catch [System.Management.Automation.ItemNotFoundException]{

Write-Host "The file $file is not found." -ForegroundColor RED

}

catch {

Write-Host $PSItem.Exception.Message -ForegroundColor RED

}

finally {

$Error.Clear()

}The screenshot below shows the output of the modified code above.

Conclusion

In this article, you’ve learned about errors in PowerShell, its properties, and how you can determine an error’s specific type. You’ve also learned the difference between how the $ErrorActionPreference variable and the PowerShell ErrorAction parameter affects how PowerShell treats non-terminating errors.

You have also learned how to use the PowerShell Try Catch Finally blocks to perform error handling, whether for specific errors or a catch-all approach.

The examples that are shown in this article only demonstrates the basics of how the Try Catch Finally blocks work. The knowledge that I hope you have gained in this article should give you the starting blocks to start applying error handling in your scripts.

Further Reading

- About_Try_Catch_Finally

- About_Automatic_Variables

- Back to Basics: The PowerShell foreach Loop

- Back to Basics: Understanding PowerShell Objects