Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Raising and Handling Python Exceptions

A Python program terminates as soon as it encounters an error. In Python, an error can be a syntax error or an exception. In this article, you will see what an exception is and how it differs from a syntax error. After that, you will learn about raising exceptions and making assertions. Then, you’ll finish with a demonstration of the try and except block.

Exceptions versus Syntax Errors

Syntax errors occur when the parser detects an incorrect statement. Observe the following example:

>>> print( 0 / 0 ))

File "<stdin>", line 1

print( 0 / 0 ))

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

The arrow indicates where the parser ran into the syntax error. In this example, there was one bracket too many. Remove it and run your code again:

>>> print( 0 / 0)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ZeroDivisionError: integer division or modulo by zero

This time, you ran into an exception error. This type of error occurs whenever syntactically correct Python code results in an error. The last line of the message indicated what type of exception error you ran into.

Instead of showing the message exception error, Python details what type of exception error was encountered. In this case, it was a ZeroDivisionError. Python comes with various built-in exceptions as well as the possibility to create self-defined exceptions.

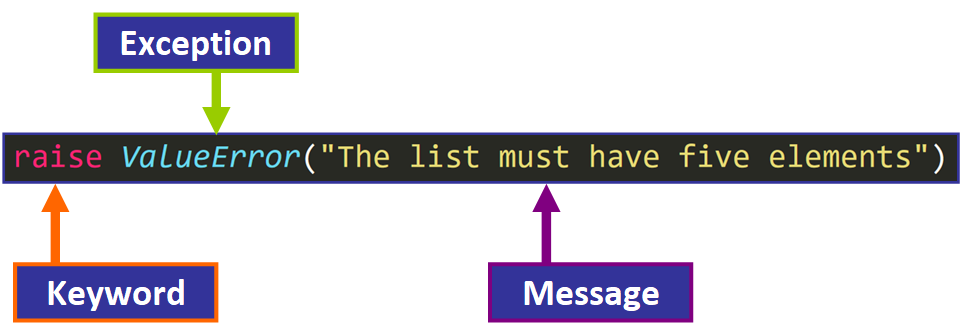

Raising an Exception

We can use raise to throw an exception if a condition occurs. The statement can be complemented with a custom exception.

If you want to throw an error when a certain condition occurs using raise, you could go about it like this:

x = 10

if x > 5:

raise Exception('x should not exceed 5. The value of x was: {}'.format(x))

When you run this code, the output will be the following:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<input>", line 4, in <module>

Exception: x should not exceed 5. The value of x was: 10

The program comes to a halt and displays our exception to screen, offering clues about what went wrong.

The AssertionError Exception

Instead of waiting for a program to crash midway, you can also start by making an assertion in Python. We assert that a certain condition is met. If this condition turns out to be True, then that is excellent! The program can continue. If the condition turns out to be False, you can have the program throw an AssertionError exception.

Have a look at the following example, where it is asserted that the code will be executed on a Linux system:

import sys

assert ('linux' in sys.platform), "This code runs on Linux only."

If you run this code on a Linux machine, the assertion passes. If you were to run this code on a Windows machine, the outcome of the assertion would be False and the result would be the following:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<input>", line 2, in <module>

AssertionError: This code runs on Linux only.

In this example, throwing an AssertionError exception is the last thing that the program will do. The program will come to halt and will not continue. What if that is not what you want?

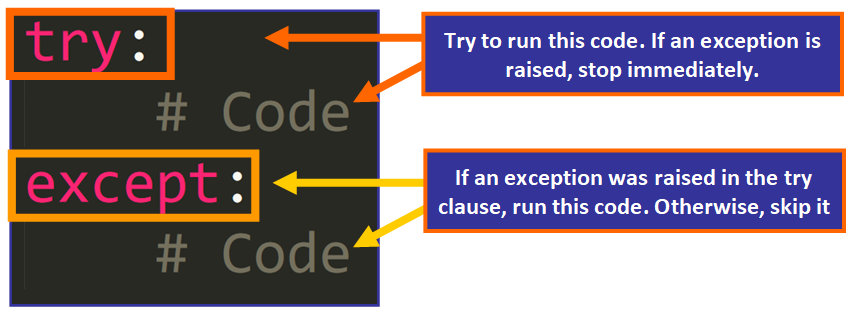

The try and except Block: Handling Exceptions

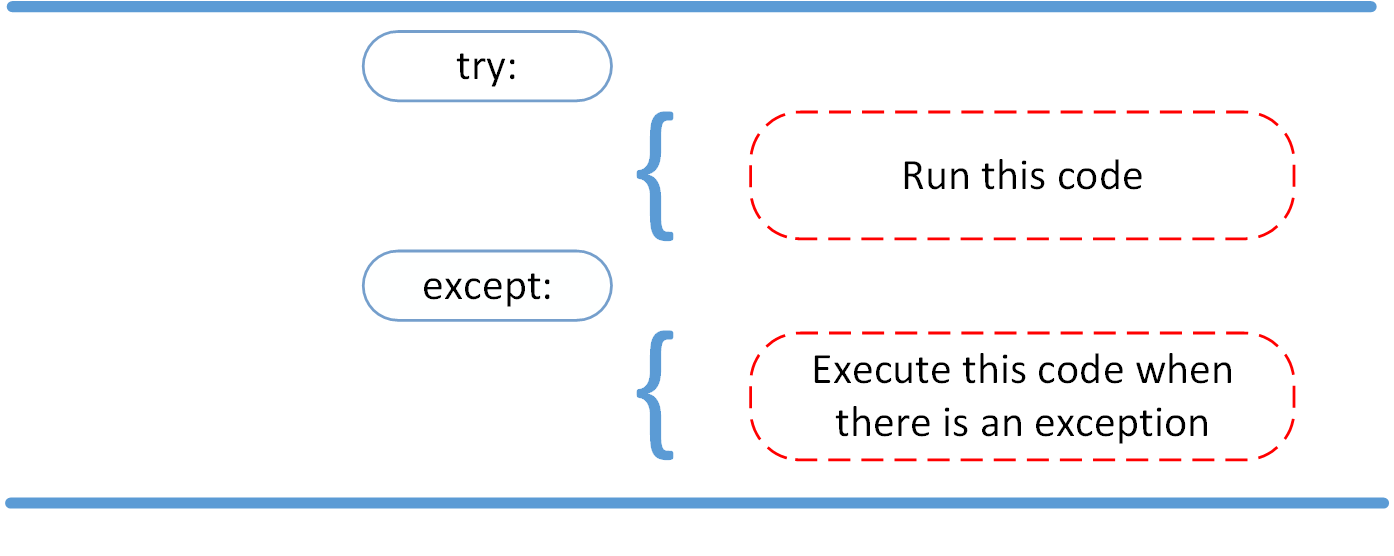

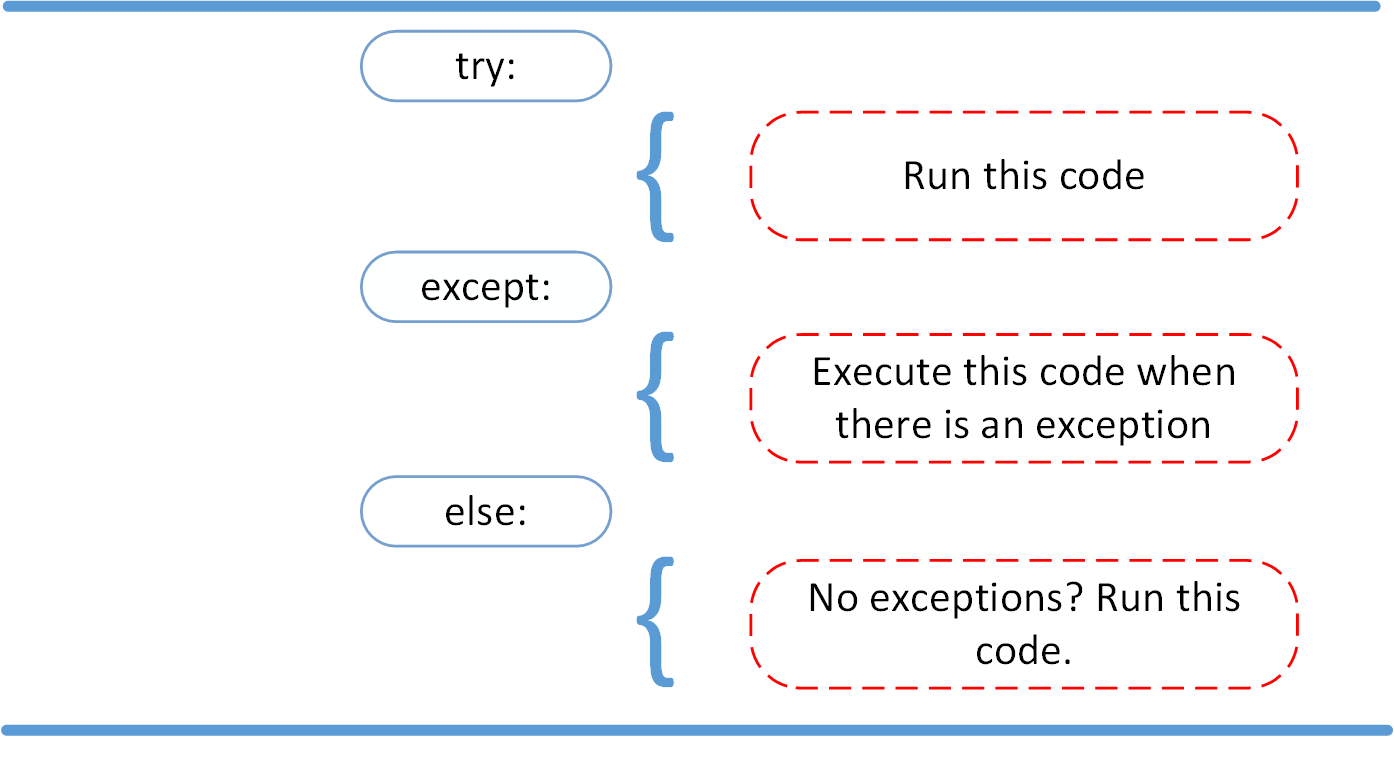

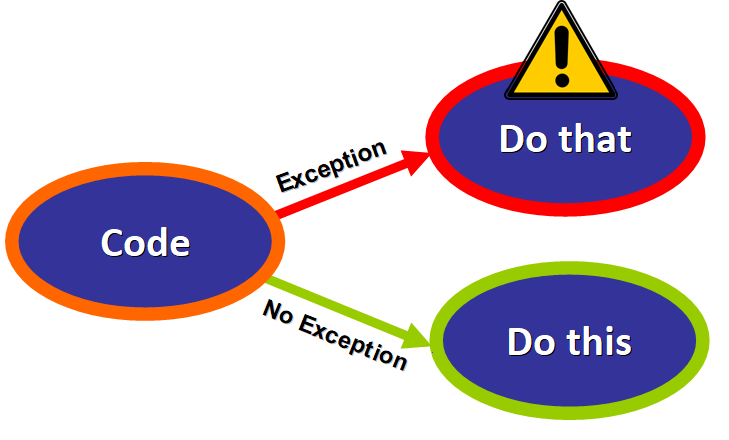

The try and except block in Python is used to catch and handle exceptions. Python executes code following the try statement as a “normal” part of the program. The code that follows the except statement is the program’s response to any exceptions in the preceding try clause.

As you saw earlier, when syntactically correct code runs into an error, Python will throw an exception error. This exception error will crash the program if it is unhandled. The except clause determines how your program responds to exceptions.

The following function can help you understand the try and except block:

def linux_interaction():

assert ('linux' in sys.platform), "Function can only run on Linux systems."

print('Doing something.')

The linux_interaction() can only run on a Linux system. The assert in this function will throw an AssertionError exception if you call it on an operating system other then Linux.

You can give the function a try using the following code:

try:

linux_interaction()

except:

pass

The way you handled the error here is by handing out a pass. If you were to run this code on a Windows machine, you would get the following output:

You got nothing. The good thing here is that the program did not crash. But it would be nice to see if some type of exception occurred whenever you ran your code. To this end, you can change the pass into something that would generate an informative message, like so:

try:

linux_interaction()

except:

print('Linux function was not executed')

Execute this code on a Windows machine:

Linux function was not executed

When an exception occurs in a program running this function, the program will continue as well as inform you about the fact that the function call was not successful.

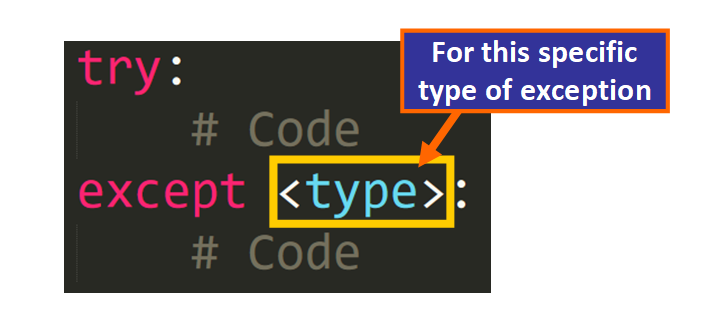

What you did not get to see was the type of error that was thrown as a result of the function call. In order to see exactly what went wrong, you would need to catch the error that the function threw.

The following code is an example where you capture the AssertionError and output that message to screen:

try:

linux_interaction()

except AssertionError as error:

print(error)

print('The linux_interaction() function was not executed')

Running this function on a Windows machine outputs the following:

Function can only run on Linux systems.

The linux_interaction() function was not executed

The first message is the AssertionError, informing you that the function can only be executed on a Linux machine. The second message tells you which function was not executed.

In the previous example, you called a function that you wrote yourself. When you executed the function, you caught the AssertionError exception and printed it to screen.

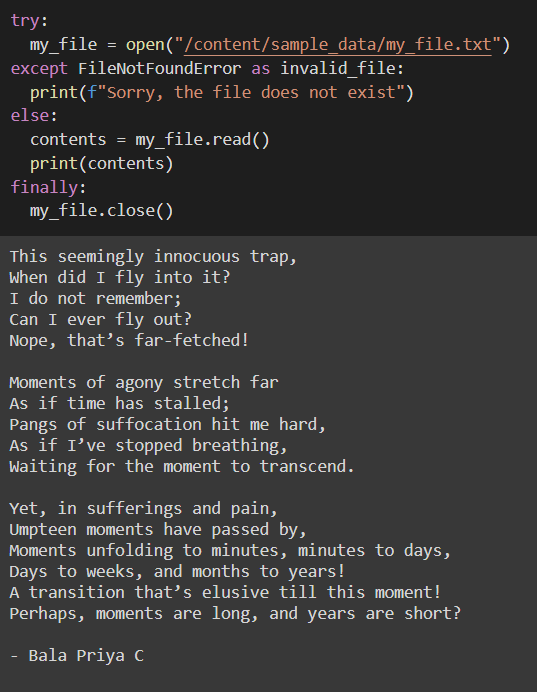

Here’s another example where you open a file and use a built-in exception:

try:

with open('file.log') as file:

read_data = file.read()

except:

print('Could not open file.log')

If file.log does not exist, this block of code will output the following:

This is an informative message, and our program will still continue to run. In the Python docs, you can see that there are a lot of built-in exceptions that you can use here. One exception described on that page is the following:

Exception

FileNotFoundErrorRaised when a file or directory is requested but doesn’t exist. Corresponds to errno ENOENT.

To catch this type of exception and print it to screen, you could use the following code:

try:

with open('file.log') as file:

read_data = file.read()

except FileNotFoundError as fnf_error:

print(fnf_error)

In this case, if file.log does not exist, the output will be the following:

[Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'file.log'

You can have more than one function call in your try clause and anticipate catching various exceptions. A thing to note here is that the code in the try clause will stop as soon as an exception is encountered.

Look at the following code. Here, you first call the linux_interaction() function and then try to open a file:

try:

linux_interaction()

with open('file.log') as file:

read_data = file.read()

except FileNotFoundError as fnf_error:

print(fnf_error)

except AssertionError as error:

print(error)

print('Linux linux_interaction() function was not executed')

If the file does not exist, running this code on a Windows machine will output the following:

Function can only run on Linux systems.

Linux linux_interaction() function was not executed

Inside the try clause, you ran into an exception immediately and did not get to the part where you attempt to open file.log. Now look at what happens when you run the code on a Linux machine:

[Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'file.log'

Here are the key takeaways:

- A

tryclause is executed up until the point where the first exception is encountered. - Inside the

exceptclause, or the exception handler, you determine how the program responds to the exception. - You can anticipate multiple exceptions and differentiate how the program should respond to them.

- Avoid using bare

exceptclauses.

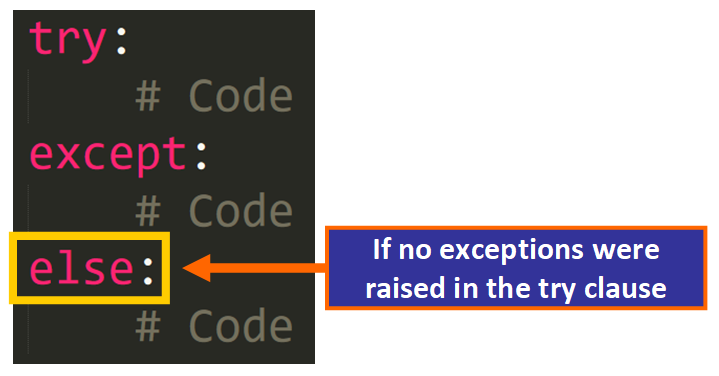

The else Clause

In Python, using the else statement, you can instruct a program to execute a certain block of code only in the absence of exceptions.

Look at the following example:

try:

linux_interaction()

except AssertionError as error:

print(error)

else:

print('Executing the else clause.')

If you were to run this code on a Linux system, the output would be the following:

Doing something.

Executing the else clause.

Because the program did not run into any exceptions, the else clause was executed.

You can also try to run code inside the else clause and catch possible exceptions there as well:

try:

linux_interaction()

except AssertionError as error:

print(error)

else:

try:

with open('file.log') as file:

read_data = file.read()

except FileNotFoundError as fnf_error:

print(fnf_error)

If you were to execute this code on a Linux machine, you would get the following result:

Doing something.

[Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'file.log'

From the output, you can see that the linux_interaction() function ran. Because no exceptions were encountered, an attempt to open file.log was made. That file did not exist, and instead of opening the file, you caught the FileNotFoundError exception.

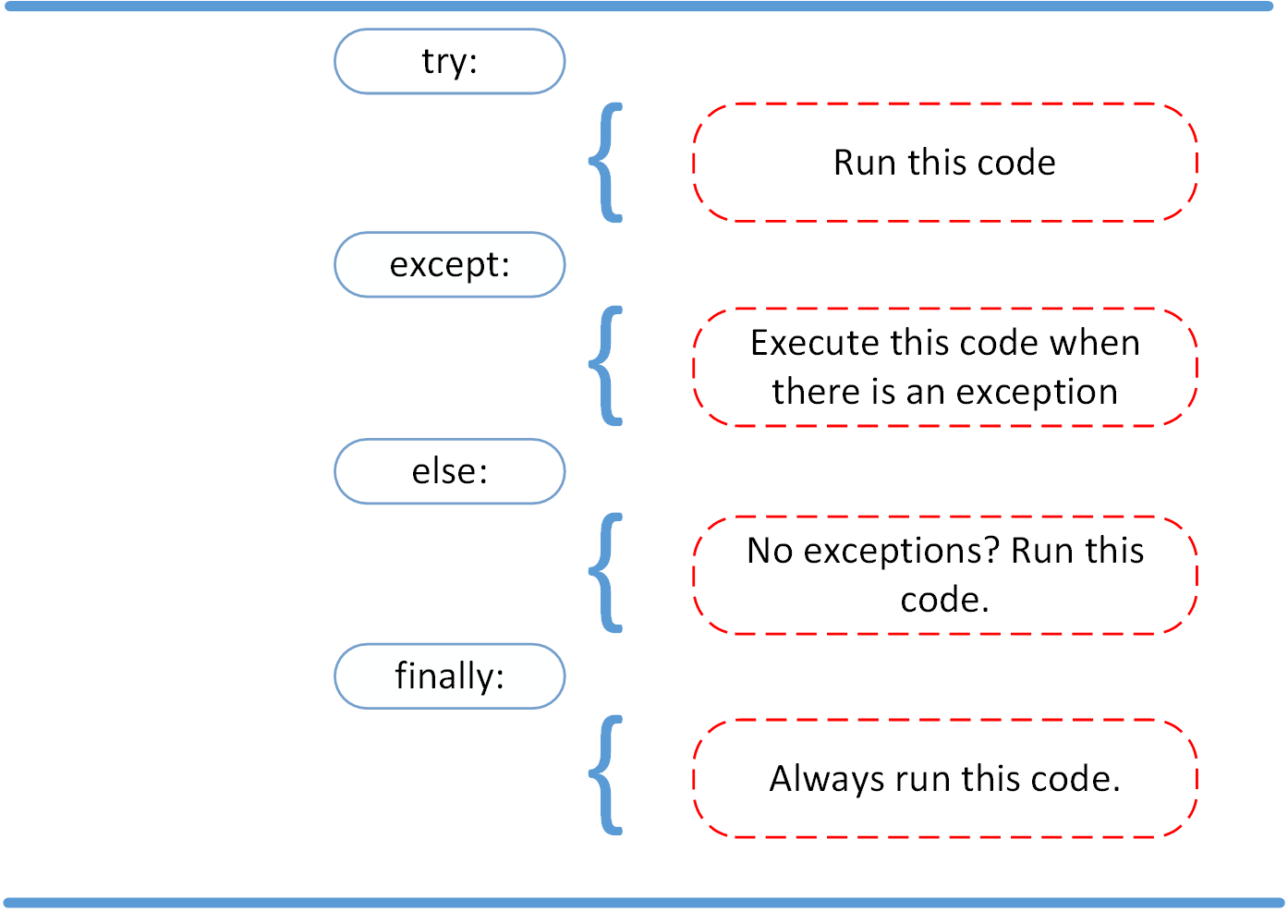

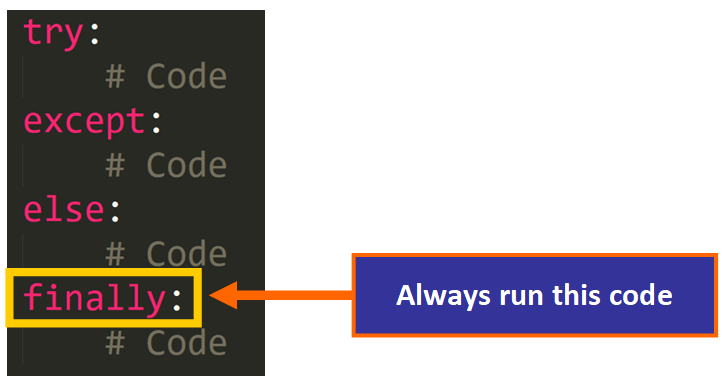

Cleaning Up After Using finally

Imagine that you always had to implement some sort of action to clean up after executing your code. Python enables you to do so using the finally clause.

Have a look at the following example:

try:

linux_interaction()

except AssertionError as error:

print(error)

else:

try:

with open('file.log') as file:

read_data = file.read()

except FileNotFoundError as fnf_error:

print(fnf_error)

finally:

print('Cleaning up, irrespective of any exceptions.')

In the previous code, everything in the finally clause will be executed. It does not matter if you encounter an exception somewhere in the try or else clauses. Running the previous code on a Windows machine would output the following:

Function can only run on Linux systems.

Cleaning up, irrespective of any exceptions.

Summing Up

After seeing the difference between syntax errors and exceptions, you learned about various ways to raise, catch, and handle exceptions in Python. In this article, you saw the following options:

raiseallows you to throw an exception at any time.assertenables you to verify if a certain condition is met and throw an exception if it isn’t.- In the

tryclause, all statements are executed until an exception is encountered. exceptis used to catch and handle the exception(s) that are encountered in the try clause.elselets you code sections that should run only when no exceptions are encountered in the try clause.finallyenables you to execute sections of code that should always run, with or without any previously encountered exceptions.

Hopefully, this article helped you understand the basic tools that Python has to offer when dealing with exceptions.

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Raising and Handling Python Exceptions

Содержание:развернуть

- Как устроен механизм исключений

- Как обрабатывать исключения в Python (try except)

-

As — сохраняет ошибку в переменную

-

Finally — выполняется всегда

-

Else — выполняется когда исключение не было вызвано

-

Несколько блоков except

-

Несколько типов исключений в одном блоке except

-

Raise — самостоятельный вызов исключений

-

Как пропустить ошибку

- Исключения в lambda функциях

- 20 типов встроенных исключений в Python

- Как создать свой тип Exception

Программа, написанная на языке Python, останавливается сразу как обнаружит ошибку. Ошибки могут быть (как минимум) двух типов:

- Синтаксические ошибки — возникают, когда написанное выражение не соответствует правилам языка (например, написана лишняя скобка);

- Исключения — возникают во время выполнения программы (например, при делении на ноль).

Синтаксические ошибки исправить просто (если вы используете IDE, он их подсветит). А вот с исключениями всё немного сложнее — не всегда при написании программы можно сказать возникнет или нет в данном месте исключение. Чтобы приложение продолжило работу при возникновении проблем, такие ошибки нужно перехватывать и обрабатывать с помощью блока try/except.

Как устроен механизм исключений

В Python есть встроенные исключения, которые появляются после того как приложение находит ошибку. В этом случае текущий процесс временно приостанавливается и передает ошибку на уровень вверх до тех пор, пока она не будет обработано. Если ошибка не будет обработана, программа прекратит свою работу (а в консоли мы увидим Traceback с подробным описанием ошибки).

💁♂️ Пример: напишем скрипт, в котором функция ожидает число, а мы передаём сроку (это вызовет исключение «TypeError»):

def b(value):

print("-> b")

print(value + 1) # ошибка тут

def a(value):

print("-> a")

b(value)

a("10")

> -> a

> -> b

> Traceback (most recent call last):

> File "test.py", line 11, in <module>

> a("10")

> File "test.py", line 8, in a

> b(value)

> File "test.py", line 3, in b

> print(value + 1)

> TypeError: can only concatenate str (not "int") to str

В данном примере мы запускаем файл «test.py» (через консоль). Вызывается функция «a«, внутри которой вызывается функция «b«. Все работает хорошо до сточки print(value + 1). Тут интерпретатор понимает, что нельзя конкатенировать строку с числом, останавливает выполнение программы и вызывает исключение «TypeError».

Далее ошибка передается по цепочке в обратном направлении: «b» → «a» → «test.py«. Так как в данном примере мы не позаботились обработать эту ошибку, вся информация по ошибке отобразится в консоли в виде Traceback.

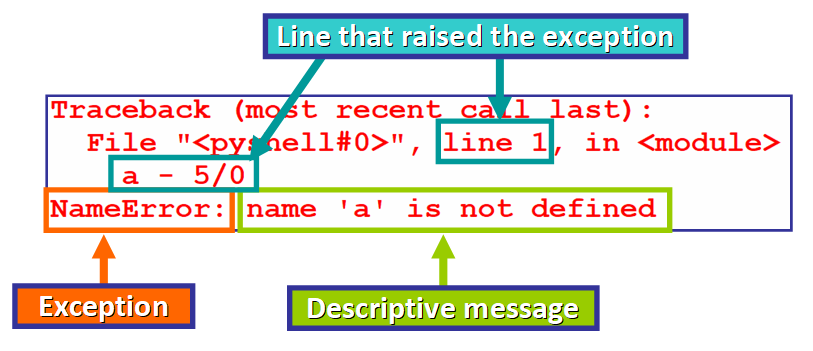

Traceback (трассировка) — это отчёт, содержащий вызовы функций, выполненные в определенный момент. Трассировка помогает узнать, что пошло не так и в каком месте это произошло.

Traceback лучше читать снизу вверх ↑

В нашем примере Traceback содержится следующую информацию (читаем снизу вверх):

TypeError— тип ошибки (означает, что операция не может быть выполнена с переменной этого типа);can only concatenate str (not "int") to str— подробное описание ошибки (конкатенировать можно только строку со строкой);- Стек вызова функций (1-я линия — место, 2-я линия — код). В нашем примере видно, что в файле «test.py» на 11-й линии был вызов функции «a» со строковым аргументом «10». Далее был вызов функции «b».

print(value + 1)это последнее, что было выполнено — тут и произошла ошибка. most recent call last— означает, что самый последний вызов будет отображаться последним в стеке (в нашем примере последним выполнилсяprint(value + 1)).

В Python ошибку можно перехватить, обработать, и продолжить выполнение программы — для этого используется конструкция try ... except ....

Как обрабатывать исключения в Python (try except)

В Python исключения обрабатываются с помощью блоков try/except. Для этого операция, которая может вызвать исключение, помещается внутрь блока try. А код, который должен быть выполнен при возникновении ошибки, находится внутри except.

Например, вот как можно обработать ошибку деления на ноль:

try:

a = 7 / 0

except:

print('Ошибка! Деление на 0')

Здесь в блоке try находится код a = 7 / 0 — при попытке его выполнить возникнет исключение и выполнится код в блоке except (то есть будет выведено сообщение «Ошибка! Деление на 0»). После этого программа продолжит свое выполнение.

💭 PEP 8 рекомендует, по возможности, указывать конкретный тип исключения после ключевого слова except (чтобы перехватывать и обрабатывать конкретные исключения):

try:

a = 7 / 0

except ZeroDivisionError:

print('Ошибка! Деление на 0')

Однако если вы хотите перехватывать все исключения, которые сигнализируют об ошибках программы, используйте тип исключения Exception:

try:

a = 7 / 0

except Exception:

print('Любая ошибка!')

As — сохраняет ошибку в переменную

Перехваченная ошибка представляет собой объект класса, унаследованного от «BaseException». С помощью ключевого слова as можно записать этот объект в переменную, чтобы обратиться к нему внутри блока except:

try:

file = open('ok123.txt', 'r')

except FileNotFoundError as e:

print(e)

> [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'ok123.txt'

В примере выше мы обращаемся к объекту класса «FileNotFoundError» (при выводе на экран через print отобразится строка с полным описанием ошибки).

У каждого объекта есть поля, к которым можно обращаться (например если нужно логировать ошибку в собственном формате):

import datetime

now = datetime.datetime.now().strftime("%d-%m-%Y %H:%M:%S")

try:

file = open('ok123.txt', 'r')

except FileNotFoundError as e:

print(f"{now} [FileNotFoundError]: {e.strerror}, filename: {e.filename}")

> 20-11-2021 18:42:01 [FileNotFoundError]: No such file or directory, filename: ok123.txt

Finally — выполняется всегда

При обработке исключений можно после блока try использовать блок finally. Он похож на блок except, но команды, написанные внутри него, выполняются обязательно. Если в блоке try не возникнет исключения, то блок finally выполнится так же, как и при наличии ошибки, и программа возобновит свою работу.

Обычно try/except используется для перехвата исключений и восстановления нормальной работы приложения, а try/finally для того, чтобы гарантировать выполнение определенных действий (например, для закрытия внешних ресурсов, таких как ранее открытые файлы).

В следующем примере откроем файл и обратимся к несуществующей строке:

file = open('ok.txt', 'r')

try:

lines = file.readlines()

print(lines[5])

finally:

file.close()

if file.closed:

print("файл закрыт!")

> файл закрыт!

> Traceback (most recent call last):

> File "test.py", line 5, in <module>

> print(lines[5])

> IndexError: list index out of range

Даже после исключения «IndexError», сработал код в секции finally, который закрыл файл.

p.s. данный пример создан для демонстрации, в реальном проекте для работы с файлами лучше использовать менеджер контекста with.

Также можно использовать одновременно три блока try/except/finally. В этом случае:

- в

try— код, который может вызвать исключения; - в

except— код, который должен выполниться при возникновении исключения; - в

finally— код, который должен выполниться в любом случае.

def sum(a, b):

res = 0

try:

res = a + b

except TypeError:

res = int(a) + int(b)

finally:

print(f"a = {a}, b = {b}, res = {res}")

sum(1, "2")

> a = 1, b = 2, res = 3

Else — выполняется когда исключение не было вызвано

Иногда нужно выполнить определенные действия, когда код внутри блока try не вызвал исключения. Для этого используется блок else.

Допустим нужно вывести результат деления двух чисел и обработать исключения в случае попытки деления на ноль:

b = int(input('b = '))

c = int(input('c = '))

try:

a = b / c

except ZeroDivisionError:

print('Ошибка! Деление на 0')

else:

print(f"a = {a}")

> b = 10

> c = 1

> a = 10.0

В этом случае, если пользователь присвоит переменной «с» ноль, то появится исключение и будет выведено сообщение «‘Ошибка! Деление на 0′», а код внутри блока else выполняться не будет. Если ошибки не будет, то на экране появятся результаты деления.

Несколько блоков except

В программе может возникнуть несколько исключений, например:

- Ошибка преобразования введенных значений к типу

float(«ValueError»); - Деление на ноль («ZeroDivisionError»).

В Python, чтобы по-разному обрабатывать разные типы ошибок, создают несколько блоков except:

try:

b = float(input('b = '))

c = float(input('c = '))

a = b / c

except ZeroDivisionError:

print('Ошибка! Деление на 0')

except ValueError:

print('Число введено неверно')

else:

print(f"a = {a}")

> b = 10

> c = 0

> Ошибка! Деление на 0

> b = 10

> c = питон

> Число введено неверно

Теперь для разных типов ошибок есть свой обработчик.

Несколько типов исключений в одном блоке except

Можно также обрабатывать в одном блоке except сразу несколько исключений. Для этого они записываются в круглых скобках, через запятую сразу после ключевого слова except. Чтобы обработать сообщения «ZeroDivisionError» и «ValueError» в одном блоке записываем их следующим образом:

try:

b = float(input('b = '))

c = float(input('c = '))

a = b / c

except (ZeroDivisionError, ValueError) as er:

print(er)

else:

print('a = ', a)

При этом переменной er присваивается объект того исключения, которое было вызвано. В результате на экран выводятся сведения о конкретной ошибке.

Raise — самостоятельный вызов исключений

Исключения можно генерировать самостоятельно — для этого нужно запустить оператор raise.

min = 100

if min > 10:

raise Exception('min must be less than 10')

> Traceback (most recent call last):

> File "test.py", line 3, in <module>

> raise Exception('min value must be less than 10')

> Exception: min must be less than 10

Перехватываются такие сообщения точно так же, как и остальные:

min = 100

try:

if min > 10:

raise Exception('min must be less than 10')

except Exception:

print('Моя ошибка')

> Моя ошибка

Кроме того, ошибку можно обработать в блоке except и пробросить дальше (вверх по стеку) с помощью raise:

min = 100

try:

if min > 10:

raise Exception('min must be less than 10')

except Exception:

print('Моя ошибка')

raise

> Моя ошибка

> Traceback (most recent call last):

> File "test.py", line 5, in <module>

> raise Exception('min must be less than 10')

> Exception: min must be less than 10

Как пропустить ошибку

Иногда ошибку обрабатывать не нужно. В этом случае ее можно пропустить с помощью pass:

try:

a = 7 / 0

except ZeroDivisionError:

pass

Исключения в lambda функциях

Обрабатывать исключения внутри lambda функций нельзя (так как lambda записывается в виде одного выражения). В этом случае нужно использовать именованную функцию.

20 типов встроенных исключений в Python

Иерархия классов для встроенных исключений в Python выглядит так:

BaseException

SystemExit

KeyboardInterrupt

GeneratorExit

Exception

ArithmeticError

AssertionError

...

...

...

ValueError

Warning

Все исключения в Python наследуются от базового BaseException:

SystemExit— системное исключение, вызываемое функциейsys.exit()во время выхода из приложения;KeyboardInterrupt— возникает при завершении программы пользователем (чаще всего при нажатии клавиш Ctrl+C);GeneratorExit— вызывается методомcloseобъектаgenerator;Exception— исключения, которые можно и нужно обрабатывать (предыдущие были системными и их трогать не рекомендуется).

От Exception наследуются:

1 StopIteration — вызывается функцией next в том случае если в итераторе закончились элементы;

2 ArithmeticError — ошибки, возникающие при вычислении, бывают следующие типы:

FloatingPointError— ошибки при выполнении вычислений с плавающей точкой (встречаются редко);OverflowError— результат вычислений большой для текущего представления (не появляется при операциях с целыми числами, но может появиться в некоторых других случаях);ZeroDivisionError— возникает при попытке деления на ноль.

3 AssertionError — выражение, используемое в функции assert неверно;

4 AttributeError — у объекта отсутствует нужный атрибут;

5 BufferError — операция, для выполнения которой требуется буфер, не выполнена;

6 EOFError — ошибка чтения из файла;

7 ImportError — ошибка импортирования модуля;

8 LookupError — неверный индекс, делится на два типа:

IndexError— индекс выходит за пределы диапазона элементов;KeyError— индекс отсутствует (для словарей, множеств и подобных объектов);

9 MemoryError — память переполнена;

10 NameError — отсутствует переменная с данным именем;

11 OSError — исключения, генерируемые операционной системой:

ChildProcessError— ошибки, связанные с выполнением дочернего процесса;ConnectionError— исключения связанные с подключениями (BrokenPipeError, ConnectionResetError, ConnectionRefusedError, ConnectionAbortedError);FileExistsError— возникает при попытке создания уже существующего файла или директории;FileNotFoundError— генерируется при попытке обращения к несуществующему файлу;InterruptedError— возникает в том случае если системный вызов был прерван внешним сигналом;IsADirectoryError— программа обращается к файлу, а это директория;NotADirectoryError— приложение обращается к директории, а это файл;PermissionError— прав доступа недостаточно для выполнения операции;ProcessLookupError— процесс, к которому обращается приложение не запущен или отсутствует;TimeoutError— время ожидания истекло;

12 ReferenceError — попытка доступа к объекту с помощью слабой ссылки, когда объект не существует;

13 RuntimeError — генерируется в случае, когда исключение не может быть классифицировано или не подпадает под любую другую категорию;

14 NotImplementedError — абстрактные методы класса нуждаются в переопределении;

15 SyntaxError — ошибка синтаксиса;

16 SystemError — сигнализирует о внутренне ошибке;

17 TypeError — операция не может быть выполнена с переменной этого типа;

18 ValueError — возникает когда в функцию передается объект правильного типа, но имеющий некорректное значение;

19 UnicodeError — исключение связанное с кодирование текста в unicode, бывает трех видов:

UnicodeEncodeError— ошибка кодирования;UnicodeDecodeError— ошибка декодирования;UnicodeTranslateError— ошибка переводаunicode.

20 Warning — предупреждение, некритическая ошибка.

💭 Посмотреть всю цепочку наследования конкретного типа исключения можно с помощью модуля inspect:

import inspect

print(inspect.getmro(TimeoutError))

> (<class 'TimeoutError'>, <class 'OSError'>, <class 'Exception'>, <class 'BaseException'>, <class 'object'>)

📄 Подробное описание всех классов встроенных исключений в Python смотрите в официальной документации.

Как создать свой тип Exception

В Python можно создавать свои исключения. При этом есть одно обязательное условие: они должны быть потомками класса Exception:

class MyError(Exception):

def __init__(self, text):

self.txt = text

try:

raise MyError('Моя ошибка')

except MyError as er:

print(er)

> Моя ошибка

С помощью try/except контролируются и обрабатываются ошибки в приложении. Это особенно актуально для критически важных частей программы, где любые «падения» недопустимы (или могут привести к негативным последствиям). Например, если программа работает как «демон», падение приведет к полной остановке её работы. Или, например, при временном сбое соединения с базой данных, программа также прервёт своё выполнение (хотя можно было отловить ошибку и попробовать соединиться в БД заново).

Вместе с try/except можно использовать дополнительные блоки. Если использовать все блоки описанные в статье, то код будет выглядеть так:

try:

# попробуем что-то сделать

except (ZeroDivisionError, ValueError) as e:

# обрабатываем исключения типа ZeroDivisionError или ValueError

except Exception as e:

# исключение не ZeroDivisionError и не ValueError

# поэтому обрабатываем исключение общего типа (унаследованное от Exception)

# сюда не сходят исключения типа GeneratorExit, KeyboardInterrupt, SystemExit

else:

# этот блок выполняется, если нет исключений

# если в этом блоке сделать return, он не будет вызван, пока не выполнился блок finally

finally:

# этот блок выполняется всегда, даже если нет исключений else будет проигнорирован

# если в этом блоке сделать return, то return в блоке

Подробнее о работе с исключениями в Python можно ознакомиться в официальной документации.

При выполнении заданий к главам вы скорее всего нередко сталкивались с возникновением различных ошибок. На этой главе мы изучим подход, который позволяет обрабатывать ошибки после их возникновения.

Напишем программу, которая будет считать обратные значения для целых чисел из заданного диапазона и выводить их в одну строку с разделителем «;». Один из вариантов кода для решения этой задачи выглядит так:

print(";".join(str(1 / x) for x in range(int(input()), int(input()) + 1)))

Программа получилась в одну строчку за счёт использования списочных выражений. Однако при вводе диапазона чисел, включающем в себя 0 (например, от -1 до 1), программа выдаст следующую ошибку:

ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

В программе произошла ошибка «деление на ноль». Такая ошибка, возникающая при выполнении программы и останавливающая её работу, называется исключением.

Попробуем в нашей программе избавиться от возникновения исключения деления на ноль. Пусть при попадании 0 в диапазон чисел, обработка не производится и выводится сообщение «Диапазон чисел содержит 0». Для этого нужно проверить до списочного выражения наличие нуля в диапазоне:

interval = range(int(input()), int(input()) + 1)

if 0 in interval:

print("Диапазон чисел содержит 0.")

else:

print(";".join(str(1 / x) for x in interval))

Теперь для диапазона, включающего в себя 0, например, от -2 до 2, исключения ZeroDivisionError не возникнет. Однако при вводе строки, которую невозможно преобразовать в целое число (например, «a»), будет вызвано другое исключение:

ValueError: invalid literal for int() with base 10: 'a'

Произошло исключение ValueError. Для борьбы с этой ошибкой нам придётся проверить, что строка состоит только из цифр. Сделать это нужно до преобразования в число. Тогда наша программа будет выглядеть так:

start = input()

end = input()

# Метод lstrip("-"), удаляющий символы "-" в начале строки, нужен для учёта

# отрицательных чисел, иначе isdigit() вернёт для них False

if not (start.lstrip("-").isdigit() and end.lstrip("-").isdigit()):

print("Необходимо ввести два числа.")

else:

interval = range(int(start), int(end) + 1)

if 0 in interval:

print("Диапазон чисел содержит 0.")

else:

print(";".join(str(1 / x) for x in interval))

Теперь наша программа работает без ошибок и при вводе строк, которые нельзя преобразовать в целое число.

Подход, который был нами применён для предотвращения ошибок, называется «Look Before You Leap» (LBYL), или «посмотри перед прыжком». В программе, реализующей такой подход, проверяются возможные условия возникновения ошибок до исполнения основного кода.

Подход LBYL имеет недостатки. Программу из примера стало сложнее читать из-за вложенного условного оператора. Проверка условия, что строка может быть преобразована в число, выглядит даже сложнее, чем списочное выражение. Вложенный условный оператор не решает поставленную задачу, а только лишь проверяет входные данные на корректность. Легко заметить, что решение основной задачи заняло меньше времени, чем составление условий проверки корректности входных данных.

Существует другой подход для работы с ошибками: «Easier to Ask Forgiveness than Permission» (EAFP) или «проще извиниться, чем спрашивать разрешение». В этом подходе сначала исполняется код, а в случае возникновения ошибок происходит их обработка. Подход EAFP реализован в Python в виде обработки исключений.

Исключения в Python являются классами ошибок. В Python есть много стандартных исключений. Они имеют определённую иерархию за счёт механизма наследования классов. В документации Python версии 3.10.8 приводится следующее дерево иерархии стандартных исключений:

BaseException

+-- SystemExit

+-- KeyboardInterrupt

+-- GeneratorExit

+-- Exception

+-- StopIteration

+-- StopAsyncIteration

+-- ArithmeticError

| +-- FloatingPointError

| +-- OverflowError

| +-- ZeroDivisionError

+-- AssertionError

+-- AttributeError

+-- BufferError

+-- EOFError

+-- ImportError

| +-- ModuleNotFoundError

+-- LookupError

| +-- IndexError

| +-- KeyError

+-- MemoryError

+-- NameError

| +-- UnboundLocalError

+-- OSError

| +-- BlockingIOError

| +-- ChildProcessError

| +-- ConnectionError

| | +-- BrokenPipeError

| | +-- ConnectionAbortedError

| | +-- ConnectionRefusedError

| | +-- ConnectionResetError

| +-- FileExistsError

| +-- FileNotFoundError

| +-- InterruptedError

| +-- IsADirectoryError

| +-- NotADirectoryError

| +-- PermissionError

| +-- ProcessLookupError

| +-- TimeoutError

+-- ReferenceError

+-- RuntimeError

| +-- NotImplementedError

| +-- RecursionError

+-- SyntaxError

| +-- IndentationError

| +-- TabError

+-- SystemError

+-- TypeError

+-- ValueError

| +-- UnicodeError

| +-- UnicodeDecodeError

| +-- UnicodeEncodeError

| +-- UnicodeTranslateError

+-- Warning

+-- DeprecationWarning

+-- PendingDeprecationWarning

+-- RuntimeWarning

+-- SyntaxWarning

+-- UserWarning

+-- FutureWarning

+-- ImportWarning

+-- UnicodeWarning

+-- BytesWarning

+-- EncodingWarning

+-- ResourceWarning

Для обработки исключения в Python используется следующий синтаксис:

try:

<код , который может вызвать исключения при выполнении>

except <классисключения_1>:

<код обработки исключения>

except <классисключения_2>:

<код обработки исключения>

...

else:

<код выполняется, если не вызвано исключение в блоке try>

finally:

<код , который выполняется всегда>

Блок try содержит код, в котором нужно обработать исключения, если они возникнут. При возникновении исключения интерпретатор последовательно проверяет в каком из блоков except обрабатывается это исключение. Исключение обрабатывается в первом блоке except, обрабатывающем класс этого исключения или базовый класс возникшего исключения. Необходимо учитывать иерархию исключений для определения порядка их обработки в блоках except. Начинать обработку исключений следует с более узких классов исключений. Если начать с более широкого класса исключения, например, Exception, то всегда при возникновении исключения будет срабатывать первый блок except. Сравните два следующих примера. В первом порядок обработки исключений указан от производных классов к базовым, а во втором – наоборот.

try:

print(1 / int(input()))

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("Ошибка деления на ноль.")

except ValueError:

print("Невозможно преобразовать строку в число.")

except Exception:

print("Неизвестная ошибка.")

При вводе значений «0» и «a» получим ожидаемый соответствующий возникающим исключениям вывод:

Невозможно преобразовать строку в число.

и

Ошибка деления на ноль.

Второй пример:

try:

print(1 / int(input()))

except Exception:

print("Неизвестная ошибка.")

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("Ошибка деления на ноль.")

except ValueError:

print("Невозможно преобразовать строку в число.")

При вводе значений «0» и «a» получим в обоих случаях неинформативный вывод:

Неизвестная ошибка.

Необязательный блок else выполняет код в случае, если в блоке try не вызвано исключение. Добавим блок else в пример для вывода сообщения об успешном выполнении операции:

try:

print(1 / int(input()))

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("Ошибка деления на ноль.")

except ValueError:

print("Невозможно преобразовать строку в число.")

except Exception:

print("Неизвестная ошибка.")

else:

print("Операция выполнена успешно.")

Теперь при вводе корректного значения, например, «5», вывод программы будет следующим:

2.0 Операция выполнена успешно.

Блок finally выполняется всегда, даже если возникло какое-то исключение, не учтённое в блоках except или код в этих блоках сам вызвал какое-либо исключение. Добавим в нашу программу вывод строки «Программа завершена» в конце программы даже при возникновении исключений:

try:

print(1 / int(input()))

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("Ошибка деления на ноль.")

except ValueError:

print("Невозможно преобразовать строку в число.")

except Exception:

print("Неизвестная ошибка.")

else:

print("Операция выполнена успешно.")

finally:

print("Программа завершена.")

Перепишем код, созданный с применением подхода LBYL, для первого примера из этой главы с использованием обработки исключений:

try:

print(";".join(str(1 / x) for x in range(int(input()), int(input()) + 1)))

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("Диапазон чисел содержит 0.")

except ValueError:

print("Необходимо ввести два числа.")

Теперь наша программа читается намного легче. При этом создание кода для обработки исключений не заняло много времени и не потребовало проверки сложных условий.

Исключения можно принудительно вызывать с помощью оператора raise. Этот оператор имеет следующий синтаксис:

raise <класс исключения>(параметры)

В качестве параметра можно, например, передать строку с сообщением об ошибке.

В Python можно создавать свои собственные исключения. Синтаксис создания исключения такой же, как и у создания класса. При создании исключения его необходимо наследовать от какого-либо стандартного класса-исключения.

Напишем программу, которая выводит сумму списка целых чисел, и вызывает исключение, если в списке чисел есть хотя бы одно чётное или отрицательное число. Создадим свои классы исключений:

- NumbersError – базовый класс исключения;

- EvenError – исключение, которое вызывается при наличии хотя бы одного чётного числа;

- NegativeError – исключение, которое вызывается при наличии хотя бы одного отрицательного числа.

class NumbersError(Exception):

pass

class EvenError(NumbersError):

pass

class NegativeError(NumbersError):

pass

def no_even(numbers):

if all(x % 2 != 0 for x in numbers):

return True

raise EvenError("В списке не должно быть чётных чисел")

def no_negative(numbers):

if all(x >= 0 for x in numbers):

return True

raise NegativeError("В списке не должно быть отрицательных чисел")

def main():

print("Введите числа в одну строку через пробел:")

try:

numbers = [int(x) for x in input().split()]

if no_negative(numbers) and no_even(numbers):

print(f"Сумма чисел равна: {sum(numbers)}.")

except NumbersError as e: # обращение к исключению как к объекту

print(f"Произошла ошибка: {e}.")

except Exception as e:

print(f"Произошла непредвиденная ошибка: {e}.")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Обратите внимание: в программе основной код выделен в функцию main. А код вне функций содержит только условный оператор и вызов функции main при выполнении условия __name__ == "__main__". Это условие проверяет, запущен ли файл как самостоятельная программа или импортирован как модуль.

Любая программа, написанная на языке программирования Python может быть импортирована как модуль в другую программу. В идеологии Python импортировать модуль – значит полностью его выполнить. Если основной код модуля содержит вызовы функций, ввод или вывод данных без использования указанного условия __name__ == "__main__", то произойдёт полноценный запуск программы. А это не всегда удобно, если из модуля нужна только отдельная функция или какой-либо класс.

При изучении модуля itertools, мы говорили о том, как импортировать модуль в программу. Покажем ещё раз два способа импорта на примере собственного модуля.

Для импорта модуля из файла, например example_module.py, нужно указать его имя, если он находится в той же папке, что и импортирующая его программа:

import example_module

Если требуется отдельный компонент модуля, например функция или класс, то импорт можно осуществить так:

from example_module import some_function, ExampleClass

Обратите внимание: при втором способе импортированные объекты попадают в пространство имён новой программы. Это означает, что они будут объектами новой программы, и в программе не должно быть других объектов с такими же именами.

Welcome! In this article, you will learn how to handle exceptions in Python.

In particular, we will cover:

- Exceptions

- The purpose of exception handling

- The try clause

- The except clause

- The else clause

- The finally clause

- How to raise exceptions

Are you ready? Let’s begin! 😀

1️⃣ Intro to Exceptions

We will start with exceptions:

- What are they?

- Why are they relevant?

- Why should you handle them?

According to the Python documentation:

Errors detected during execution are called exceptions and are not unconditionally fatal.

Exceptions are raised when the program encounters an error during its execution. They disrupt the normal flow of the program and usually end it abruptly. To avoid this, you can catch them and handle them appropriately.

You’ve probably seen them during your programming projects.

If you’ve ever tried to divide by zero in Python, you must have seen this error message:

>>> a = 5/0

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#1>", line 1, in <module>

a = 5/0

ZeroDivisionError: division by zeroIf you tried to index a string with an invalid index, you definitely got this error message:

>>> a = "Hello, World"

>>> a[456]

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#3>", line 1, in <module>

a[456]

IndexError: string index out of rangeThese are examples of exceptions.

🔹 Common Exceptions

There are many different types of exceptions, and they are all raised in particular situations. Some of the exceptions that you will most likely see as you work on your projects are:

- IndexError — raised when you try to index a list, tuple, or string beyond the permitted boundaries. For example:

>>> num = [1, 2, 6, 5]

>>> num[56546546]

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#7>", line 1, in <module>

num[56546546]

IndexError: list index out of range- KeyError — raised when you try to access the value of a key that doesn’t exist in a dictionary. For example:

>>> students = {"Nora": 15, "Gino": 30}

>>> students["Lisa"]

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#9>", line 1, in <module>

students["Lisa"]

KeyError: 'Lisa'- NameError — raised when a name that you are referencing in the code doesn’t exist. For example:

>>> a = b

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#10>", line 1, in <module>

a = b

NameError: name 'b' is not defined- TypeError — raised when an operation or function is applied to an object of an inappropriate type. For example:

>>> (5, 6, 7) * (1, 2, 3)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#12>", line 1, in <module>

(5, 6, 7) * (1, 2, 3)

TypeError: can't multiply sequence by non-int of type 'tuple'- ZeroDivisionError — raised when you try to divide by zero.

>>> a = 5/0

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#13>", line 1, in <module>

a = 5/0

ZeroDivisionError: division by zero💡 Tips: To learn more about other types of built-in exceptions, please refer to this article in the Python Documentation.

🔸 Anatomy of an Exception

I’m sure that you must have noticed a general pattern in these error messages. Let’s break down their general structure piece by piece:

First, we find this line (see below). A traceback is basically a list detailing the function calls that were made before the exception was raised.

The traceback helps you during the debugging process because you can analyze the sequence of function calls that resulted in the exception:

Traceback (most recent call last):Then, we see this line (see below) with the path to the file and the line that raised the exception. In this case, the path was the Python shell <pyshell#0> since the example was executed directly in IDLE.

File "<pyshell#0>", line 1, in <module>

a - 5/0💡 Tip: If the line that raised the exception belongs to a function, <module> is replaced by the name of the function.

Finally, we see a descriptive message detailing the type of exception and providing additional information to help us debug the code:

NameError: name 'a' is not defined2️⃣ Exception Handling: Purpose & Context

You may ask: why would I want to handle exceptions? Why is this helpful for me? By handling exceptions, you can provide an alternative flow of execution to avoid crashing your program unexpectedly.

🔹 Example: User Input

Imagine what would happen if a user who is working with your program enters an invalid input. This would raise an exception because an invalid operation was performed during the process.

If your program doesn’t handle this correctly, it will crash suddenly and the user will have a very disappointing experience with your product.

But if you do handle the exception, you will be able to provide an alternative to improve the experience of the user.

Perhaps you could display a descriptive message asking the user to enter a valid input, or you could provide a default value for the input. Depending on the context, you can choose what to do when this happens, and this is the magic of error handling. It can save the day when unexpected things happen. ⭐️

🔸 What Happens Behind the Scenes?

Basically, when we handle an exception, we are telling the program what to do if the exception is raised. In that case, the «alternative» flow of execution will come to the rescue. If no exceptions are raised, the code will run as expected.

3️⃣ Time to Code: The try … except Statement

Now that you know what exceptions are and why you should we handle them, we will start diving into the built-in tools that the Python languages offers for this purpose.

First, we have the most basic statement: try … except.

Let’s illustrate this with a simple example. We have this small program that asks the user to enter the name of a student to display his/her age:

students = {"Nora": 15, "Gino": 30}

def print_student_age():

name = input("Please enter the name of the student: ")

print(students[name])

print_student_age()Notice how we are not validating user input at the moment, so the user might enter invalid values (names that are not in the dictionary) and the consequences would be catastrophic because the program would crash if a KeyError is raised:

# User Input

Please enter the name of the student: "Daniel"

# Error Message

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<path>", line 15, in <module>

print_student_age()

File "<path>", line 13, in print_student_age

print(students[name])

KeyError: '"Daniel"'🔹 Syntax

We can handle this nicely using try … except. This is the basic syntax:

In our example, we would add the try … except statement within the function. Let’s break this down piece by piece:

students = {"Nora": 15, "Gino": 30}

def print_student_age():

while True:

try:

name = input("Please enter the name of the student: ")

print(students[name])

break

except:

print("This name is not registered")

print_student_age()If we «zoom in», we see the try … except statement:

try:

name = input("Please enter the name of the student: ")

print(students[name])

break

except:

print("This name is not registered")- When the function is called, the try clause will run. If no exceptions are raised, the program will run as expected.

- But if an exception is raised in the try clause, the flow of execution will immediately jump to the except clause to handle the exception.

💡 Note: This code is contained within a while loop to continue asking for user input if the value is invalid. This is an example:

Please enter the name of the student: "Lulu"

This name is not registered

Please enter the name of the student: This is great, right? Now we can continue asking for user input if the value is invalid.

At the moment, we are handling all possible exceptions with the same except clause. But what if we only want to handle a specific type of exception? Let’s see how we could do this.

🔸 Catching Specific Exceptions

Since not all types of exceptions are handled in the same way, we can specify which exceptions we would like to handle with this syntax:

This is an example. We are handling the ZeroDivisionError exception in case the user enters zero as the denominator:

def divide_integers():

while True:

try:

a = int(input("Please enter the numerator: "))

b = int(input("Please enter the denominator: "))

print(a / b)

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("Please enter a valid denominator.")

divide_integers()This would be the result:

# First iteration

Please enter the numerator: 5

Please enter the denominator: 0

Please enter a valid denominator.

# Second iteration

Please enter the numerator: 5

Please enter the denominator: 2

2.5We are handling this correctly. But… if another type of exception is raised, the program will not handle it gracefully.

Here we have an example of a ValueError because one of the values is a float, not an int:

Please enter the numerator: 5

Please enter the denominator: 0.5

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<path>", line 53, in <module>

divide_integers()

File "<path>", line 47, in divide_integers

b = int(input("Please enter the denominator: "))

ValueError: invalid literal for int() with base 10: '0.5'We can customize how we handle different types of exceptions.

🔹 Multiple Except Clauses

To do this, we need to add multiple except clauses to handle different types of exceptions differently.

According to the Python Documentation:

A try statement may have more than one except clause, to specify handlers for different exceptions. At most one handler will be executed.

In this example, we have two except clauses. One of them handles ZeroDivisionError and the other one handles ValueError, the two types of exceptions that could be raised in this try block.

def divide_integers():

while True:

try:

a = int(input("Please enter the numerator: "))

b = int(input("Please enter the denominator: "))

print(a / b)

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("Please enter a valid denominator.")

except ValueError:

print("Both values have to be integers.")

divide_integers() 💡 Tip: You have to determine which types of exceptions might be raised in the try block to handle them appropriately.

🔸 Multiple Exceptions, One Except Clause

You can also choose to handle different types of exceptions with the same except clause.

According to the Python Documentation:

An except clause may name multiple exceptions as a parenthesized tuple.

This is an example where we catch two exceptions (ZeroDivisionError and ValueError) with the same except clause:

def divide_integers():

while True:

try:

a = int(input("Please enter the numerator: "))

b = int(input("Please enter the denominator: "))

print(a / b)

except (ZeroDivisionError, ValueError):

print("Please enter valid integers.")

divide_integers()The output would be the same for the two types of exceptions because they are handled by the same except clause:

Please enter the numerator: 5

Please enter the denominator: 0

Please enter valid integers.Please enter the numerator: 0.5

Please enter valid integers.

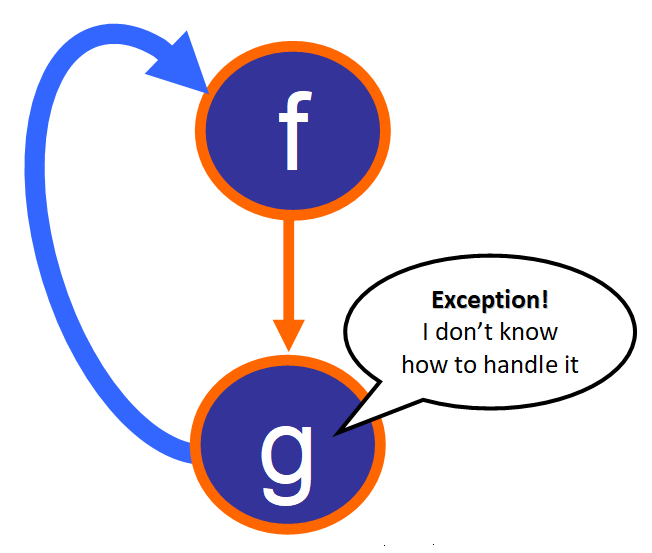

Please enter the numerator: 🔹 Handling Exceptions Raised by Functions Called in the try Clause

An interesting aspect of exception handling is that if an exception is raised in a function that was previously called in the try clause of another function and the function itself does not handle it, the caller will handle it if there is an appropriate except clause.

According to the Python Documentation:

Exception handlers don’t just handle exceptions if they occur immediately in the try clause, but also if they occur inside functions that are called (even indirectly) in the try clause.

Let’s see an example to illustrate this:

def f(i):

try:

g(i)

except IndexError:

print("Please enter a valid index")

def g(i):

a = "Hello"

return a[i]

f(50)We have the f function and the g function. f calls g in the try clause. With the argument 50, g will raise an IndexError because the index 50 is not valid for the string a.

But g itself doesn’t handle the exception. Notice how there is no try … except statement in the g function. Since it doesn’t handle the exception, it «sends» it to f to see if it can handle it, as you can see in the diagram below:

Since f does know how to handle an IndexError, the situation is handled gracefully and this is the output:

Please enter a valid index💡 Note: If f had not handled the exception, the program would have ended abruptly with the default error message for an IndexError.

🔸 Accessing Specific Details of Exceptions

Exceptions are objects in Python, so you can assign the exception that was raised to a variable. This way, you can print the default description of the exception and access its arguments.

According to the Python Documentation:

The except clause may specify a variable after the exception name. The variable is bound to an exception instance with the arguments stored in instance.args.

Here we have an example (see below) were we assign the instance of ZeroDivisionError to the variable e. Then, we can use this variable within the except clause to access the type of the exception, its message, and arguments.

def divide_integers():

while True:

try:

a = int(input("Please enter the numerator: "))

b = int(input("Please enter the denominator: "))

print(a / b)

# Here we assign the exception to the variable e

except ZeroDivisionError as e:

print(type(e))

print(e)

print(e.args)

divide_integers()The corresponding output would be:

Please enter the numerator: 5

Please enter the denominator: 0

# Type

<class 'ZeroDivisionError'>

# Message

division by zero

# Args

('division by zero',)💡 Tip: If you are familiar with special methods, according to the Python Documentation: «for convenience, the exception instance defines __str__() so the arguments can be printed directly without having to reference .args.»

4️⃣ Now Let’s Add: The «else» Clause

The else clause is optional, but it’s a great tool because it lets us execute code that should only run if no exceptions were raised in the try clause.

According to the Python Documentation:

The

try…exceptstatement has an optional else clause, which, when present, must follow all except clauses. It is useful for code that must be executed if the try clause does not raise an exception.

Here is an example of the use of the else clause:

def divide_integers():

while True:

try:

a = int(input("Please enter the numerator: "))

b = int(input("Please enter the denominator: "))

result = a / b

except (ZeroDivisionError, ValueError):

print("Please enter valid integers. The denominator can't be zero")

else:

print(result)

divide_integers()If no exception are raised, the result is printed:

Please enter the numerator: 5

Please enter the denominator: 5

1.0But if an exception is raised, the result is not printed:

Please enter the numerator: 5

Please enter the denominator: 0

Please enter valid integers. The denominator can't be zero💡 Tip: According to the Python Documentation:

The use of the

elseclause is better than adding additional code to thetryclause because it avoids accidentally catching an exception that wasn’t raised by the code being protected by thetry…exceptstatement.

5️⃣ The «finally» Clause

The finally clause is the last clause in this sequence. It is optional, but if you include it, it has to be the last clause in the sequence. The finally clause is always executed, even if an exception was raised in the try clause.

According to the Python Documentation:

If a

finallyclause is present, thefinallyclause will execute as the last task before thetrystatement completes. Thefinallyclause runs whether or not thetrystatement produces an exception.

The finally clause is usually used to perform «clean-up» actions that should always be completed. For example, if we are working with a file in the try clause, we will always need to close the file, even if an exception was raised when we were working with the data.

Here is an example of the finally clause:

def divide_integers():

while True:

try:

a = int(input("Please enter the numerator: "))

b = int(input("Please enter the denominator: "))

result = a / b

except (ZeroDivisionError, ValueError):

print("Please enter valid integers. The denominator can't be zero")

else:

print(result)

finally:

print("Inside the finally clause")

divide_integers()This is the output when no exceptions were raised:

Please enter the numerator: 5

Please enter the denominator: 5

1.0

Inside the finally clauseThis is the output when an exception was raised:

Please enter the numerator: 5

Please enter the denominator: 0

Please enter valid integers. The denominator can't be zero

Inside the finally clauseNotice how the finally clause always runs.

❗️Important: remember that the else clause and the finally clause are optional, but if you decide to include both, the finally clause has to be the last clause in the sequence.

6️⃣ Raising Exceptions

Now that you know how to handle exceptions in Python, I would like to share with you this helpful tip: you can also choose when to raise exceptions in your code.

This can be helpful for certain scenarios. Let’s see how you can do this:

This line will raise a ValueError with a custom message.

Here we have an example (see below) of a function that prints the value of the items of a list or tuple, or the characters in a string. But you decided that you want the list, tuple, or string to be of length 5. You start the function with an if statement that checks if the length of the argument data is 5. If it isn’t, a ValueError exception is raised:

def print_five_items(data):

if len(data) != 5:

raise ValueError("The argument must have five elements")

for item in data:

print(item)

print_five_items([5, 2])The output would be:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<path>", line 122, in <module>

print_five_items([5, 2])

File "<path>", line 117, in print_five_items

raise ValueError("The argument must have five elements")

ValueError: The argument must have five elementsNotice how the last line displays the descriptive message:

ValueError: The argument must have five elementsYou can then choose how to handle the exception with a try … except statement. You could add an else clause and/or a finally clause. You can customize it to fit your needs.

🔹 Helpful Resources

- Exceptions

- Handling Exceptions

- Defining Clean-up Actions

I hope you enjoyed reading my article and found it helpful. Now you have the necessary tools to handle exceptions in Python and you can use them to your advantage when you write Python code. ? Check out my online courses. You can follow me on Twitter.

⭐️ You may enjoy my other freeCodeCamp /news articles:

- The @property Decorator in Python: Its Use Cases, Advantages, and Syntax

- Data Structures 101: Graphs — A Visual Introduction for Beginners

- Data Structures 101: Arrays — A Visual Introduction for Beginners

Learn to code for free. freeCodeCamp’s open source curriculum has helped more than 40,000 people get jobs as developers. Get started

| Введение | |

| Пример с базовым Exception | |

| Два исключения | |

| except Error as e:: Печать текста ошибки | |

| else | |

| finally | |

| raise | |

| Пример 2 | |

| Пример 3 | |

| Исключения, которые не нужно обрабатывать | |

| Список исключений | |

| Разбор примеров: IndexError, ValueError, KeyError | |

| Похожие статьи |

Введение

Если в коде есть ошибка, которую видит интерпретатор поднимается исключение, создается так называемый

Exception Object, выполнение останавливается, в терминале

показывается Traceback.

В английском языке используется словосочетание Raise Exception

Исключение, которое не было предусмотрено разработчиком называется необработанным (Unhandled Exception)

Такое поведение не всегда является оптимальным. Не все ошибки дожны останавливать работу кода.

Возможно, где-то разработчик ожидает появление ошибок и их можно обработать по-другому.

try и except нужны прежде всего для того, чтобы код правильно реагировал на возможные ошибки и продолжал выполняться

там, где появление ошибки некритично.

Исключение, которое предусмотрено в коде называется обработанным (Handled)

Блок try except имеет следующий синтаксис

try:

pass

except Exception:

pass

else:

pass

finally:

pass

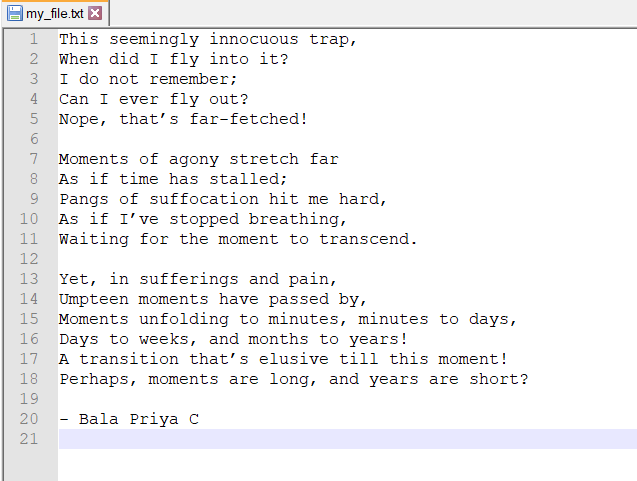

В этой статье я создал файл

try_except.py

куда копирую код из примеров.

Пример

Попробуем открыть несуществующий файл и воспользоваться базовым Exception

try:

f = open(‘missing.txt’)

except Exception:

print(‘ERR: File not found’)

python try_except.py

ERR: No missing.txt file found

Ошибка поймана, видно наше сообщение а не Traceback

Проверим, что когда файл существует всё хорошо

try:

f = open(‘existing.txt’)

except Exception:

print(‘ERR: File not found’)

python try_except.py

Пустота означает успех

Два исключения

Если ошибок больше одной нужны дополнительные исключения. Попробуем открыть существующий файл, и после этого

добавить ошибку.

try:

f = open(‘existing.txt’)

x = bad_value

except Exception:

print(‘ERR: File not found’)

python try_except.py

ERR: File not found

Файл открылся, но так как в следующей строке ошибка — в терминале появилось вводящее в заблуждение сообщение.

Проблема не в том, что «File not found» а в том, что bad_value нигде не определёно.

Избежать сбивающих с толку сообщений можно указав тип ожидаемой ошибки. В данном примере это FileNotFoundError

try:

# expected exception

f = open(‘existing.txt’)

# unexpected exception should result in Traceback

x = bad_value

except FileNotFoundError:

print(‘ERR: File not found’)

python try_except.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File «/home/andrei/python/try_except2.py», line 5, in <module>

x = bad_value

NameError: name ‘bad_value’ is not defined

Вторая ошибка не поймана поэтому показан Traceback

Поймать обе ошибки можно добавив второй Exception

try:

# expected exception should be caught by FileNotFoundError

f = open(‘missing.txt’)

# unexpected exception should be caught by Exception

x = bad_value

except FileNotFoundError:

print(‘ERR: File not found’)

except Exception:

print(‘ERR: Something unexpected went wrong’)

python try_except.py

ERR: File not found

ERR: Something unexpected went wrong

Печать текста ошибки

Вместо своего текста можно выводить текст ошибки. Попробуем с существующим файлом — должна быть одна пойманная ошибка.

try:

# expected exception should be caught by FileNotFoundError

f = open(‘existing.txt’)

# unexpected exception should be caught by Exception

x = bad_value

except FileNotFoundError as e:

print(e)

except Exception as e:

print(e)

python try_except.py

name ‘bad_value’ is not defined

Теперь попытаемся открыть несуществующий файл — должно быть две пойманные ошибки.

try:

# expected exception should be caught by FileNotFoundError

f = open(‘missing.txt’)

# unexpected exception should be caught by Exception

x = bad_value

except FileNotFoundError as e:

print(e)

except Exception as e:

print(e)

python try_except.py

name ‘bad_value’ is not defined

[Errno 2] No such file or directory: ‘missing.txt’

else

Блок else будет выполнен если исключений не будет поймано.

Попробуем открыть существующий файл

existing.txt

в котором есть строка

www.heihei.ru

try:

f = open(‘existing.txt’)

except FileNotFoundError as e:

print(e)

except Exception as e:

print(e)

else:

print(f.read())

f.close()

python try_except.py

www.heihei.ru

Если попробовать открыть несуществующий файл

missing.txt

то исключение обрабатывается, а код из блока else не выполняется.

[Errno 2] No such file or directory: ‘missing.txt’

finally

Блок finally будет выполнен независимо от того, поймано исключение или нет

try:

f = open(‘existing.txt’)

except FileNotFoundError as e:

print(e)

except Exception as e:

print(e)

else:

print(f.read())

f.close()

finally:

print(«Finally!»)

www.heihei.ru

Finally!

А если попытаться открыть несуществующий

missing.txt

[Errno 2] No such file or directory: ‘missing.txt’

Finally!

Когда нужно применять finally:

Рассмотрим скрипт, который вносит какие-то изменения в систему.

Затем он пытается что-то сделать. В конце возвращает

систему в исходное состояние.

Если ошибка случится в середине скрипта — он уже не сможет вернуть систему в исходное состояние.

Но если вынести возврат к исходному состоянию в блок finally он сработает даже при ошибке

в предыдущем блоке.

import os

def make_at(path, dir_name):

original_path = os.getcwd()

os.chdir(path)

os.mkdir(dir_name)

os.chdir(original_path)

Этот скрипт не вернётся в исходную директорию при ошибке в os.mkdir(dir_name)

А у скрипта ниже такой проблемы нет

def make_at(path, dir_name):

original_path = os.getcwd()

os.chdir(path)

try:

os.mkdir(dir_name)

finally:

os.chdir(original_path)

Не лишнима будет добавить обработку и вывод исключения

import os

import sys

def make_at(path, dir_name):

original_path = os.getcwd()

os.chdir(path)

try:

os.mkdir(dir_name)

except OSError as e:

print(e, file=sys.stderr)

raise

finally:

os.chdir(original_path)

По умолчанию print() выводит в sys.stdout, но в случае ислючений логичнее выводить в sys.stderr

raise

Можно вызывать исключения вручную в любом месте кода с помощью

raise.

try:

f = open(‘outdated.txt’)

if f.name == ‘outdated.txt’:

raise Exception

except FileNotFoundError as e:

print(e)

except Exception as e:

print(‘File is outdated!’)

else:

print(f.read())

f.close()

finally:

print(«Finally!»)

python try_except.py

File is outdated!

Finally!

raise

можно использовать для перевызова исключения, например, чтобы уйти от использования кодов ошибок.

Для этого достаточно вызвать raise без аргументов — поднимется текущее исключение.

Пример 2

Рассмотрим функцию, которая принимает числа прописью и возвращает цифрами

DIGIT_MAP = {

‘zero’: ‘0’,

‘one’: ‘1’,

‘two’: ‘2’,

‘three’: ‘3’,

‘four’: ‘4’,

‘five’: ‘5’,

‘six’: ‘6’,

‘seven’: ‘7’,

‘eight’: ‘8’,

‘nine’: ‘9’,

}

def convert(s):

number = »

for token in s:

number += DIGIT_MAP[token]

x = int(number)

return x

python

>>> from exc1 import convert

>>> convert(«one three three seven».split())

1337

Теперь передадим аргумент, который не предусмотрен в словаре

>>> convert(«something unseen«.split())

Traceback (most recent call last):

File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module>

File «/home/andrei/python/exc1.py», line 17, in convert

number &plu= DIGIT_MAP[token]

KeyError: ‘something’

KeyError — это тип Exception объекта. Полный список можно изучить в конце статьи.

Исключение прошло следующий путь:

REPL → convert() → DIGIT_MAP(«something») → KeyError

Обработать это исключение можно внеся изменения в функцию convert

convert(s):

try:

number = »

for token in s:

number += DIGIT_MAP[token]

x = int(number)

print(«Conversion succeeded! x = «, x)

except KeyError:

print(«Conversion failed!»)

x = —1

return x

>>> from exc1 import convert

>>> convert(«one nine six one».split())

Conversion succeeded! x = 1961

1961

>>> convert(«something unseen».split())

Conversion failed!

-1

Эта обработка не спасает если передать int вместо итерируемого объекта

>>> convert(2022)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module>

File «/home/andrei/python/exc1.py», line 17, in convert

for token in s:

TypeError: ‘int’ object is not iterable

Нужно добавить обработку TypeError

…

except KeyError:

print(«Conversion failed!»)

x = —1

except TypeError:

print(«Conversion failed!»)

x = —1

return x

>>> from exc1 import convert

>>> convert(«2022».split())

Conversion failed!

-1

Избавимся от повторов, удалив принты, объединив два исключения в кортеж и вынесем присваивание значения x

из try блока.

Также добавим

докстринг

с описанием функции.

def convert(s):

«»»Convert a string to an integer.»»»

x = —1

try:

number = »

for token in s:

number += DIGIT_MAP[token]

x = int(number)

except (KeyError, TypeError):

pass

return x

>>> from exc4 import convert

>>> convert(«one nine six one».split())

1961

>>> convert(«bad nine six one».split())

-1

>>> convert(2022)

-1

Ошибки обрабатываются, но без принтов, процесс не очень информативен.

Грамотно показать текст сообщений об ошибках можно импортировав sys и изменив функцию

import sys

DIGIT_MAP = {

‘zero’: ‘0’,

‘one’: ‘1’,

‘two’: ‘2’,

‘three’: ‘3’,

‘four’: ‘4’,

‘five’: ‘5’,

‘six’: ‘6’,

‘seven’: ‘7’,

‘eight’: ‘8’,

‘nine’: ‘9’,

}

def convert(s):

«»»Convert a string to an integer.»»»

try:

number = »

for token in s:

number += DIGIT_MAP[token]

return(int(number))

except (KeyError, TypeError) as e:

print(f«Conversion error: {e!r}», file=sys.stderr)

return —1

>>> from exc1 import convert

>>> convert(2022)

Conversion error: TypeError(«‘int’ object is not iterable»)

-1

>>> convert(«one nine six one».split())

1961

>>> convert(«bad nine six one».split())

Conversion error: KeyError(‘bad’)

Ошибки обрабатываются и их текст виден в терминале.

С помощью

!r

выводится

repr()

ошибки

raise вместо кода ошибки

В предыдущем примере мы полагались на возвращение числа -1 в качестве кода ошибки.

Добавим к коду примера функцию string_log() и поработаем с ней

def string_log(s):

v = convert(s)

return log(v)

>>> from exc1 import string_log

>>> string_log(«one two eight».split())

4.852030263919617

>>> string_log(«bad one two».split())

Conversion error: KeyError(‘bad’)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module>

File «/home/andrei/exc1.py», line 32, in string_log

return log(v)

ValueError: math domain error

convert() вернул -1 а string_log попробовал его обработать и не смог.

Можно заменить return -1 на raise. Это считается более правильным подходом в Python

def convert(s):

«»»Convert a string to an integer.»»»

try:

number = »

for token in s:

number += DIGIT_MAP[token]

return(int(number))

except (KeyError, TypeError) as e:

print(f«Conversion error: {e!r}», file=sys.stderr)

raise

>>> from exc7 import string_log

>>> string_log(«one zero».split())

2.302585092994046

>>> string_log(«bad one two».split())

Conversion error: KeyError(‘bad’)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module>

File «/home/andrei/exc7.py», line 31, in string_log

v = convert(s)

File «/home/andrei/exc7.py», line 23, in convert

number += DIGIT_MAP[token]

KeyError: ‘bad’

Пример 3

Рассмотрим алгоритм по поиску квадратного корня

def sqrt(x):

«»»Compute square roots using the method

of Heron of Alexandria.

Args:

x: The number for which the square root

is to be computed.

Returns:

The square root of x.

«»»

guess = x

i = 0

while guess * guess != x and i < 20:

guess = (guess + x / guess) / 2.0

i += 1

return guess

def main():

print(sqrt(9))

print(sqrt(2))

if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

main()

python sqrt_ex.py

3.0

1.414213562373095

При попытке вычислить корень от -1 получим ошибку

def main():

print(sqrt(9))

print(sqrt(2))

print(sqrt(-1))

python sqrt_ex.py

3.0

1.414213562373095

Traceback (most recent call last):

File «/home/andrei/sqrt_ex.py», line 26, in <module>

main()

File «/home/andrei/sqrt_ex.py», line 23, in main

print(sqrt(-1))

File «/home/andrei/sqrt_ex.py», line 16, in sqrt

guess = (guess + x / guess) / 2.0

ZeroDivisionError: float division by zero

В строке

guess = (guess + x / guess) / 2.0

Происходит деление на ноль

Обработать можно следующим образом:

def main():

try:

print(sqrt(9))

print(sqrt(2))

print(sqrt(-1))

except ZeroDivisionError:

print(«Cannot compute square root «

«of a negative number.»)

print(«Program execution continues «

«normally here.»)

Обратите внимание на то, что в try помещены все вызовы функции

python sqrt_ex.py

3.0

1.414213562373095

Cannot compute square root of a negative number.

Program execution continues normally here.

Если пытаться делить на ноль несколько раз — поднимется одно исключение и всё что находится в блоке

try после выполняться не будет

def main():

try:

print(sqrt(9))

print(sqrt(-1))

print(sqrt(2))

print(sqrt(-1))

python sqrt_ex.py

3.0

Cannot compute square root of a negative number.

Program execution continues normally here.

Каждую попытку вычислить корень из -1 придётся обрабатывать отдельно. Это кажется неудобным, но

в этом и заключается смысл — каждое место где вы ждёте ислючение нужно помещать в свой

try except блок.

Можно обработать исключение так:

try:

while guess * guess != x and i < 20:

guess = (guess + x / guess) / 2.0

i += 1

except ZeroDivisionError:

raise ValueError()

return guess

def main():

print(sqrt(9))

print(sqrt(-1))

python sqrt_ex.py

3.0

Traceback (most recent call last):

File «/home/andrei/sqrt_ex3.py», line 17, in sqrt

guess = (guess + x / guess) / 2.0

ZeroDivisionError: float division by zero

During handling of the above exception, another exception occurred:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File «/home/andrei/sqrt_ex3.py», line 30, in <module>

main()

File «/home/andrei/sqrt_ex3.py», line 25, in main

print(sqrt(-1))

File «/home/andrei/sqrt_ex3.py», line 20, in sqrt

raise ValueError()

ValueError

Гораздо логичнее поднимать исключение сразу при получении аргумента

def sqrt(x):

«»»Compute square roots using the method

of Heron of Alexandria.

Args: