Errors¶

Errors or mistakes in a program are often referred to as bugs. They are almost always the fault of the programmer. The process of finding and eliminating errors is called debugging. Errors can be classified into three major groups:

- Syntax errors

- Runtime errors

- Logical errors

Syntax errors¶

Python will find these kinds of errors when it tries to parse your program, and exit with an error message without running anything. Syntax errors are mistakes in the use of the Python language, and are analogous to spelling or grammar mistakes in a language like English: for example, the sentence Would you some tea? does not make sense – it is missing a verb.

Common Python syntax errors include:

- leaving out a keyword

- putting a keyword in the wrong place

- leaving out a symbol, such as a colon, comma or brackets

- misspelling a keyword

- incorrect indentation

- empty block

Note

it is illegal for any block (like an if body, or the body of a function) to be left completely empty. If you want a block to do nothing, you can use the pass statement inside the block.

Python will do its best to tell you where the error is located, but sometimes its messages can be misleading: for example, if you forget to escape a quotation mark inside a string you may get a syntax error referring to a place later in your code, even though that is not the real source of the problem. If you can’t see anything wrong on the line specified in the error message, try backtracking through the previous few lines. As you program more, you will get better at identifying and fixing errors.

Here are some examples of syntax errors in Python:

myfunction(x, y): return x + y else: print("Hello!") if mark >= 50 print("You passed!") if arriving: print("Hi!") esle: print("Bye!") if flag: print("Flag is set!")

Runtime errors¶

If a program is syntactically correct – that is, free of syntax errors – it will be run by the Python interpreter. However, the program may exit unexpectedly during execution if it encounters a runtime error – a problem which was not detected when the program was parsed, but is only revealed when a particular line is executed. When a program comes to a halt because of a runtime error, we say that it has crashed.

Consider the English instruction flap your arms and fly to Australia. While the instruction is structurally correct and you can understand its meaning perfectly, it is impossible for you to follow it.

Some examples of Python runtime errors:

- division by zero

- performing an operation on incompatible types

- using an identifier which has not been defined

- accessing a list element, dictionary value or object attribute which doesn’t exist

- trying to access a file which doesn’t exist

Runtime errors often creep in if you don’t consider all possible values that a variable could contain, especially when you are processing user input. You should always try to add checks to your code to make sure that it can deal with bad input and edge cases gracefully. We will look at this in more detail in the chapter about exception handling.

Logical errors¶

Logical errors are the most difficult to fix. They occur when the program runs without crashing, but produces an incorrect result. The error is caused by a mistake in the program’s logic. You won’t get an error message, because no syntax or runtime error has occurred. You will have to find the problem on your own by reviewing all the relevant parts of your code – although some tools can flag suspicious code which looks like it could cause unexpected behaviour.

Sometimes there can be absolutely nothing wrong with your Python implementation of an algorithm – the algorithm itself can be incorrect. However, more frequently these kinds of errors are caused by programmer carelessness. Here are some examples of mistakes which lead to logical errors:

- using the wrong variable name

- indenting a block to the wrong level

- using integer division instead of floating-point division

- getting operator precedence wrong

- making a mistake in a boolean expression

- off-by-one, and other numerical errors

If you misspell an identifier name, you may get a runtime error or a logical error, depending on whether the misspelled name is defined.

A common source of variable name mix-ups and incorrect indentation is frequent copying and pasting of large blocks of code. If you have many duplicate lines with minor differences, it’s very easy to miss a necessary change when you are editing your pasted lines. You should always try to factor out excessive duplication using functions and loops – we will look at this in more detail later.

Exercise 1¶

-

Find all the syntax errors in the code snippet above, and explain why they are errors.

-

Find potential sources of runtime errors in this code snippet:

dividend = float(input("Please enter the dividend: ")) divisor = float(input("Please enter the divisor: ")) quotient = dividend / divisor quotient_rounded = math.round(quotient)

-

Find potential sources of runtime errors in this code snippet:

for x in range(a, b): print("(%f, %f, %f)" % my_list[x])

-

Find potential sources of logic errors in this code snippet:

product = 0 for i in range(10): product *= i sum_squares = 0 for i in range(10): i_sq = i**2 sum_squares += i_sq nums = 0 for num in range(10): num += num

Handling exceptions¶

Until now, the programs that we have written have generally ignored the fact that things can go wrong. We have have tried to prevent runtime errors by checking data which may be incorrect before we used it, but we haven’t yet seen how we can handle errors when they do occur – our programs so far have just crashed suddenly whenever they have encountered one.

There are some situations in which runtime errors are likely to occur. Whenever we try to read a file or get input from a user, there is a chance that something unexpected will happen – the file may have been moved or deleted, and the user may enter data which is not in the right format. Good programmers should add safeguards to their programs so that common situations like this can be handled gracefully – a program which crashes whenever it encounters an easily foreseeable problem is not very pleasant to use. Most users expect programs to be robust enough to recover from these kinds of setbacks.

If we know that a particular section of our program is likely to cause an error, we can tell Python what to do if it does happen. Instead of letting the error crash our program we can intercept it, do something about it, and allow the program to continue.

All the runtime (and syntax) errors that we have encountered are called exceptions in Python – Python uses them to indicate that something exceptional has occurred, and that your program cannot continue unless it is handled. All exceptions are subclasses of the Exception class – we will learn more about classes, and how to write your own exception types, in later chapters.

The try and except statements¶

To handle possible exceptions, we use a try-except block:

try: age = int(input("Please enter your age: ")) print("I see that you are %d years old." % age) except ValueError: print("Hey, that wasn't a number!")

Python will try to process all the statements inside the try block. If a ValueError occurs at any point as it is executing them, the flow of control will immediately pass to the except block, and any remaining statements in the try block will be skipped.

In this example, we know that the error is likely to occur when we try to convert the user’s input to an integer. If the input string is not a number, this line will trigger a ValueError – that is why we specified it as the type of error that we are going to handle.

We could have specified a more general type of error – or even left the type out entirely, which would have caused the except clause to match any kind of exception – but that would have been a bad idea. What if we got a completely different error that we hadn’t predicted? It would be handled as well, and we wouldn’t even notice that anything unusual was going wrong. We may also want to react in different ways to different kinds of errors. We should always try pick specific rather than general error types for our except clauses.

It is possible for one except clause to handle more than one kind of error: we can provide a tuple of exception types instead of a single type:

try: dividend = int(input("Please enter the dividend: ")) divisor = int(input("Please enter the divisor: ")) print("%d / %d = %f" % (dividend, divisor, dividend/divisor)) except(ValueError, ZeroDivisionError): print("Oops, something went wrong!")

A try-except block can also have multiple except clauses. If an exception occurs, Python will check each except clause from the top down to see if the exception type matches. If none of the except clauses match, the exception will be considered unhandled, and your program will crash:

try: dividend = int(input("Please enter the dividend: ")) divisor = int(input("Please enter the divisor: ")) print("%d / %d = %f" % (dividend, divisor, dividend/divisor)) except ValueError: print("The divisor and dividend have to be numbers!") except ZeroDivisionError: print("The dividend may not be zero!")

Note that in the example above if a ValueError occurs we won’t know whether it was caused by the dividend or the divisor not being an integer – either one of the input lines could cause that error. If we want to give the user more specific feedback about which input was wrong, we will have to wrap each input line in a separate try-except block:

try: dividend = int(input("Please enter the dividend: ")) except ValueError: print("The dividend has to be a number!") try: divisor = int(input("Please enter the divisor: ")) except ValueError: print("The divisor has to be a number!") try: print("%d / %d = %f" % (dividend, divisor, dividend/divisor)) except ZeroDivisionError: print("The dividend may not be zero!")

In general, it is a better idea to use exception handlers to protect small blocks of code against specific errors than to wrap large blocks of code and write vague, generic error recovery code. It may sometimes seem inefficient and verbose to write many small try-except statements instead of a single catch-all statement, but we can mitigate this to some extent by making effective use of loops and functions to reduce the amount of code duplication.

How an exception is handled¶

When an exception occurs, the normal flow of execution is interrupted. Python checks to see if the line of code which caused the exception is inside a try block. If it is, it checks to see if any of the except blocks associated with the try block can handle that type of exception. If an appropriate handler is found, the exception is handled, and the program continues from the next statement after the end of that try-except.

If there is no such handler, or if the line of code was not in a try block, Python will go up one level of scope: if the line of code which caused the exception was inside a function, that function will exit immediately, and the line which called the function will be treated as if it had thrown the exception. Python will check if that line is inside a try block, and so on. When a function is called, it is placed on Python’s stack, which we will discuss in the chapter about functions. Python traverses this stack when it tries to handle an exception.

If an exception is thrown by a line which is in the main body of your program, not inside a function, the program will terminate. When the exception message is printed, you should also see a traceback – a list which shows the path the exception has taken, all the way back to the original line which caused the error.

Error checks vs exception handling¶

Exception handling gives us an alternative way to deal with error-prone situations in our code. Instead of performing more checks before we do something to make sure that an error will not occur, we just try to do it – and if an error does occur we handle it. This can allow us to write simpler and more readable code. Let’s look at a more complicated input example – one in which we want to keep asking the user for input until the input is correct. We will try to write this example using the two different approaches:

# with checks n = None while n is None: s = input("Please enter an integer: ") if s.lstrip('-').isdigit(): n = int(s) else: print("%s is not an integer." % s) # with exception handling n = None while n is None: try: s = input("Please enter an integer: ") n = int(s) except ValueError: print("%s is not an integer." % s)

In the first code snippet, we have to write quite a convoluted check to test whether the user’s input is an integer – first we strip off a minus sign if it exists, and then we check if the rest of the string consists only of digits. But there’s a very simple criterion which is also what we really want to know: will this string cause a ValueError if we try to convert it to an integer? In the second snippet we can in effect check for exactly the right condition instead of trying to replicate it ourselves – something which isn’t always easy to do. For example, we could easily have forgotten that integers can be negative, and written the check in the first snippet incorrectly.

Here are a few other advantages of exception handling:

- It separates normal code from code that handles errors.

- Exceptions can easily be passed along functions in the stack until they reach a function which knows how to handle them. The intermediate functions don’t need to have any error-handling code.

- Exceptions come with lots of useful error information built in – for example, they can print a traceback which helps us to see exactly where the error occurred.

The else and finally statements¶

There are two other clauses that we can add to a try-except block: else and finally. else will be executed only if the try clause doesn’t raise an exception:

try: age = int(input("Please enter your age: ")) except ValueError: print("Hey, that wasn't a number!") else: print("I see that you are %d years old." % age)

We want to print a message about the user’s age only if the integer conversion succeeds. In the first exception handler example, we put this print statement directly after the conversion inside the try block. In both cases, the statement will only be executed if the conversion statement doesn’t raise an exception, but putting it in the else block is better practice – it means that the only code inside the try block is the single line that is the potential source of the error that we want to handle.

When we edit this program in the future, we may introduce additional statements that should also be executed if the age input is successfully converted. Some of these statements may also potentially raise a ValueError. If we don’t notice this, and put them inside the try clause, the except clause will also handle these errors if they occur. This is likely to cause some odd and unexpected behaviour. By putting all this extra code in the else clause instead, we avoid taking this risk.

The finally clause will be executed at the end of the try-except block no matter what – if there is no exception, if an exception is raised and handled, if an exception is raised and not handled, and even if we exit the block using break, continue or return. We can use the finally clause for cleanup code that we always want to be executed:

try: age = int(input("Please enter your age: ")) except ValueError: print("Hey, that wasn't a number!") else: print("I see that you are %d years old." % age) finally: print("It was really nice talking to you. Goodbye!")

Exercise 2¶

-

Extend the program in exercise 7 of the loop control statements chapter to include exception handling. Whenever the user enters input of the incorrect type, keep prompting the user for the same value until it is entered correctly. Give the user sensible feedback.

-

Add a try-except statement to the body of this function which handles a possible

IndexError, which could occur if the index provided exceeds the length of the list. Print an error message if this happens:def print_list_element(thelist, index): print(thelist[index])

-

This function adds an element to a list inside a dict of lists. Rewrite it to use a try-except statement which handles a possible

KeyErrorif the list with the name provided doesn’t exist in the dictionary yet, instead of checking beforehand whether it does. Includeelseandfinallyclauses in your try-except block:def add_to_list_in_dict(thedict, listname, element): if listname in thedict: l = thedict[listname] print("%s already has %d elements." % (listname, len(l))) else: thedict[listname] = [] print("Created %s." % listname) thedict[listname].append(element) print("Added %s to %s." % (element, listname))

The with statement¶

Using the exception object¶

Python’s exception objects contain more information than just the error type. They also come with some kind of message – we have already seen some of these messages displayed when our programs have crashed. Often these messages aren’t very user-friendly – if we want to report an error to the user we usually need to write a more descriptive message which explains how the error is related to what the user did. For example, if the error was caused by incorrect input, it is helpful to tell the user which of the input values was incorrect.

Sometimes the exception message contains useful information which we want to display to the user. In order to access the message, we need to be able to access the exception object. We can assign the object to a variable that we can use inside the except clause like this:

try: age = int(input("Please enter your age: ")) except ValueError as err: print(err)

err is not a string, but Python knows how to convert it into one – the string representation of an exception is the message, which is exactly what we want. We can also combine the exception message with our own message:

try: age = int(input("Please enter your age: ")) except ValueError as err: print("You entered incorrect age input: %s" % err)

Note that inserting a variable into a formatted string using %s also converts the variable to a string.

Raising exceptions¶

We can raise exceptions ourselves using the raise statement:

try: age = int(input("Please enter your age: ")) if age < 0: raise ValueError("%d is not a valid age. Age must be positive or zero.") except ValueError as err: print("You entered incorrect age input: %s" % err) else: print("I see that you are %d years old." % age)

We can raise our own ValueError if the age input is a valid integer, but it’s negative. When we do this, it has exactly the same effect as any other exception – the flow of control will immediately exit the try clause at this point and pass to the except clause. This except clause can match our exception as well, since it is also a ValueError.

We picked ValueError as our exception type because it’s the most appropriate for this kind of error. There’s nothing stopping us from using a completely inappropriate exception class here, but we should try to be consistent. Here are a few common exception types which we are likely to raise in our own code:

TypeError: this is an error which indicates that a variable has the wrong type for some operation. We might raise it in a function if a parameter is not of a type that we know how to handle.ValueError: this error is used to indicate that a variable has the right type but the wrong value. For example, we used it whenagewas an integer, but the wrong kind of integer.NotImplementedError: we will see in the next chapter how we use this exception to indicate that a class’s method has to be implemented in a child class.

We can also write our own custom exception classes which are based on existing exception classes – we will see some examples of this in a later chapter.

Something we may want to do is raise an exception that we have just intercepted – perhaps because we want to handle it partially in the current function, but also want to respond to it in the code which called the function:

try: age = int(input("Please enter your age: ")) except ValueError as err: print("You entered incorrect age input: %s" % err) raise err

Exercise 3¶

- Rewrite the program from the first question of exercise 2 so that it prints the text of Python’s original exception inside the

exceptclause instead of a custom message. - Rewrite the program from the second question of exercise 2 so that the exception which is caught in the

exceptclause is re-raised after the error message is printed.

Debugging programs¶

Syntax errors are usually quite straightforward to debug: the error message shows us the line in the file where the error is, and it should be easy to find it and fix it.

Runtime errors can be a little more difficult to debug: the error message and the traceback can tell us exactly where the error occurred, but that doesn’t necessarily tell us what the problem is. Sometimes they are caused by something obvious, like an incorrect identifier name, but sometimes they are triggered by a particular state of the program – it’s not always clear which of many variables has an unexpected value.

Logical errors are the most difficult to fix because they don’t cause any errors that can be traced to a particular line in the code. All that we know is that the code is not behaving as it should be – sometimes tracking down the area of the code which is causing the incorrect behaviour can take a long time.

It is important to test your code to make sure that it behaves the way that you expect. A quick and simple way of testing that a function is doing the right thing, for example, is to insert a print statement after every line which outputs the intermediate results which were calculated on that line. Most programmers intuitively do this as they are writing a function, or perhaps if they need to figure out why it isn’t doing the right thing:

def hypotenuse(x, y): print("x is %f and y is %f" % (x, y)) x_2 = x**2 print(x_2) y_2 = y**2 print(y_2) z_2 = x_2 + y_2 print(z_2) z = math.sqrt(z_2) print(z) return z

This is a quick and easy thing to do, and even experienced programmers are guilty of doing it every now and then, but this approach has several disadvantages:

-

As soon as the function is working, we are likely to delete all the print statements, because we don’t want our program to print all this debugging information all the time. The problem is that code often changes – the next time we want to test this function we will have to add the print statements all over again.

-

To avoid rewriting the print statements if we happen to need them again, we may be tempted to comment them out instead of deleting them – leaving them to clutter up our code, and possibly become so out of sync that they end up being completely useless anyway.

-

To print out all these intermediate values, we had to spread out the formula inside the function over many lines. Sometimes it is useful to break up a calculation into several steps, if it is very long and putting it all on one line makes it hard to read, but sometimes it just makes our code unnecessarily verbose. Here is what the function above would normally look like:

def hypotenuse(x, y): return math.sqrt(x**2 + y**2)

How can we do this better? If we want to inspect the values of variables at various steps of a program’s execution, we can use a tool like pdb. If we want our program to print out informative messages, possibly to a file, and we want to be able to control the level of detail at runtime without having to change anything in the code, we can use logging.

Most importantly, to check that our code is working correctly now and will keep working correctly, we should write a permanent suite of tests which we can run on our code regularly. We will discuss testing in more detail in a later chapter.

Logging¶

Sometimes it is valuable for a program to output messages to a console or a file as it runs. These messages can be used as a record of the program’s execution, and help us to find errors. Sometimes a bug occurs intermittently, and we don’t know what triggers it – if we only add debugging output to our program when we want to begin an active search for the bug, we may be unable to reproduce it. If our program logs messages to a file all the time, however, we may find that some helpful information has been recorded when we check the log after the bug has occurred.

Some kinds of messages are more important than others – errors are noteworthy events which should almost always be logged. Messages which record that an operation has been completed successfully may sometimes be useful, but are not as important as errors. Detailed messages which debug every step of a calculation can be interesting if we are trying to debug the calculation, but if they were printed all the time they would fill the console with noise (or make our log file really, really big).

We can use Python’s logging module to add logging to our program in an easy and consistent way. Logging statements are almost like print statements, but whenever we log a message we specify a level for the message. When we run our program, we set a desired log level for the program. Only messages which have a level greater than or equal to the level which we have set will appear in the log. This means that we can temporarily switch on detailed logging and switch it off again just by changing the log level in one place.

There is a consistent set of logging level names which most languages use. In order, from the highest value (most severe) to the lowest value (least severe), they are:

- CRITICAL – for very serious errors

- ERROR – for less serious errors

- WARNING – for warnings

- INFO – for important informative messages

- DEBUG – for detailed debugging messages

These names are used for integer constants defined in the logging module. The module also provides methods which we can use to log messages. By default these messages are printed to the console, and the default log level is WARNING. We can configure the module to customise its behaviour – for example, we can write the messages to a file instead, raise or lower the log level and change the message format. Here is a simple logging example:

import logging # log messages to a file, ignoring anything less severe than ERROR logging.basicConfig(filename='myprogram.log', level=logging.ERROR) # these messages should appear in our file logging.error("The washing machine is leaking!") logging.critical("The house is on fire!") # but these ones won't logging.warning("We're almost out of milk.") logging.info("It's sunny today.") logging.debug("I had eggs for breakfast.")

There’s also a special exception method which is used for logging exceptions. The level used for these messages is ERROR, but additional information about the exception is added to them. This method is intended to be used inside exception handlers instead of error:

try: age = int(input("How old are you? ")) except ValueError as err: logging.exception(err)

If we have a large project, we may want to set up a more complicated system for logging – perhaps we want to format certain messages differently, log different messages to different files, or log to multiple locations at the same time. The logging module also provides us with logger and handler objects for this purpose. We can use multiple loggers to create our messages, customising each one independently. Different handlers are associated with different logging locations. We can connect up our loggers and handlers in any way we like – one logger can use many handlers, and multiple loggers can use the same handler.

Exercise 4¶

- Write logging configuration for a program which logs to a file called

log.txtand discards all logs less important thanINFO. - Rewrite the second program from exercise 2 so that it uses this logging configuration instead of printing messages to the console (except for the first print statement, which is the purpose of the function).

- Do the same with the third program from exercise 2.

Answers to exercises¶

Answer to exercise 1¶

-

There are five syntax errors:

- Missing

defkeyword in function definition elseclause without anif- Missing colon after

ifcondition - Spelling mistake (“esle”)

- The

ifblock is empty because theprintstatement is not indented correctly

- Missing

-

- The values entered by the user may not be valid integers or floating-point numbers.

- The user may enter zero for the divisor.

- If the

mathlibrary hasn’t been imported,math.roundis undefined.

-

a,bandmy_listneed to be defined before this snippet.- The attempt to access the list element with index

xmay fail during one of the loop iterations if the range fromatobexceeds the size ofmy_list. - The string formatting operation inside the

printstatement expectsmy_list[x]to be a tuple with three numbers. If it has too many or too few elements, or isn’t a tuple at all, the attempt to format the string will fail.

-

- If you are accumulating a number total by multiplication, not addition, you need to initialise the total to

1, not0, otherwise the product will always be zero! - The line which adds

i_sqtosum_squaresis not aligned correctly, and will only add the last value ofi_sqafter the loop has concluded. - The wrong variable is used: at each loop iteration the current number in the range is added to itself and

numsremains unchanged.

- If you are accumulating a number total by multiplication, not addition, you need to initialise the total to

Answer to exercise 2¶

-

Here is an example program:

person = {} properties = [ ("name", str), ("surname", str), ("age", int), ("height", float), ("weight", float), ] for property, p_type in properties: valid_value = None while valid_value is None: try: value = input("Please enter your %s: " % property) valid_value = p_type(value) except ValueError: print("Could not convert %s '%s' to type %s. Please try again." % (property, value, p_type.__name__)) person[property] = valid_value

-

Here is an example program:

def print_list_element(thelist, index): try: print(thelist[index]) except IndexError: print("The list has no element at index %d." % index)

-

Here is an example program:

def add_to_list_in_dict(thedict, listname, element): try: l = thedict[listname] except KeyError: thedict[listname] = [] print("Created %s." % listname) else: print("%s already has %d elements." % (listname, len(l))) finally: thedict[listname].append(element) print("Added %s to %s." % (element, listname))

Answer to exercise 3¶

-

Here is an example program:

person = {} properties = [ ("name", str), ("surname", str), ("age", int), ("height", float), ("weight", float), ] for property, p_type in properties: valid_value = None while valid_value is None: try: value = input("Please enter your %s: " % property) valid_value = p_type(value) except ValueError as ve: print(ve) person[property] = valid_value

-

Here is an example program:

def print_list_element(thelist, index): try: print(thelist[index]) except IndexError as ie: print("The list has no element at index %d." % index) raise ie

Answer to exercise 4¶

-

Here is an example of the logging configuration:

import logging logging.basicConfig(filename='log.txt', level=logging.INFO)

-

Here is an example program:

def print_list_element(thelist, index): try: print(thelist[index]) except IndexError: logging.error("The list has no element at index %d." % index)

-

Here is an example program:

def add_to_list_in_dict(thedict, listname, element): try: l = thedict[listname] except KeyError: thedict[listname] = [] logging.info("Created %s." % listname) else: logging.info("%s already has %d elements." % (listname, len(l))) finally: thedict[listname].append(element) logging.info("Added %s to %s." % (element, listname))

Обработка ошибок увеличивает отказоустойчивость кода, защищая его от потенциальных сбоев, которые могут привести к преждевременному завершению работы.

Прежде чем переходить к обсуждению того, почему обработка исключений так важна, и рассматривать встроенные в Python исключения, важно понять, что есть тонкая грань между понятиями ошибки и исключения.

Ошибку нельзя обработать, а исключения Python обрабатываются при выполнении программы. Ошибка может быть синтаксической, но существует и много видов исключений, которые возникают при выполнении и не останавливают программу сразу же. Ошибка может указывать на критические проблемы, которые приложение и не должно перехватывать, а исключения — состояния, которые стоит попробовать перехватить. Ошибки — вид непроверяемых и невозвратимых ошибок, таких как OutOfMemoryError, которые не стоит пытаться обработать.

Обработка исключений делает код более отказоустойчивым и помогает предотвращать потенциальные проблемы, которые могут привести к преждевременной остановке выполнения. Представьте код, который готов к развертыванию, но все равно прекращает работу из-за исключения. Клиент такой не примет, поэтому стоит заранее обработать конкретные исключения, чтобы избежать неразберихи.

Ошибки могут быть разных видов:

- Синтаксические

- Недостаточно памяти

- Ошибки рекурсии

- Исключения

Разберем их по очереди.

Синтаксические ошибки (SyntaxError)

Синтаксические ошибки часто называют ошибками разбора. Они возникают, когда интерпретатор обнаруживает синтаксическую проблему в коде.

Рассмотрим на примере.

a = 8

b = 10

c = a b

File "", line 3

c = a b

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

Стрелка вверху указывает на место, где интерпретатор получил ошибку при попытке исполнения. Знак перед стрелкой указывает на причину проблемы. Для устранения таких фундаментальных ошибок Python будет делать большую часть работы за программиста, выводя название файла и номер строки, где была обнаружена ошибка.

Недостаточно памяти (OutofMemoryError)

Ошибки памяти чаще всего связаны с оперативной памятью компьютера и относятся к структуре данных под названием “Куча” (heap). Если есть крупные объекты (или) ссылки на подобные, то с большой долей вероятности возникнет ошибка OutofMemory. Она может появиться по нескольким причинам:

- Использование 32-битной архитектуры Python (максимальный объем выделенной памяти невысокий, между 2 и 4 ГБ);

- Загрузка файла большого размера;

- Запуск модели машинного обучения/глубокого обучения и много другое;

Обработать ошибку памяти можно с помощью обработки исключений — резервного исключения. Оно используется, когда у интерпретатора заканчивается память и он должен немедленно остановить текущее исполнение. В редких случаях Python вызывает OutofMemoryError, позволяя скрипту каким-то образом перехватить самого себя, остановить ошибку памяти и восстановиться.

Но поскольку Python использует архитектуру управления памятью из языка C (функция malloc()), не факт, что все процессы восстановятся — в некоторых случаях MemoryError приведет к остановке. Следовательно, обрабатывать такие ошибки не рекомендуется, и это не считается хорошей практикой.

Ошибка рекурсии (RecursionError)

Эта ошибка связана со стеком и происходит при вызове функций. Как и предполагает название, ошибка рекурсии возникает, когда внутри друг друга исполняется много методов (один из которых — с бесконечной рекурсией), но это ограничено размером стека.

Все локальные переменные и методы размещаются в стеке. Для каждого вызова метода создается стековый кадр (фрейм), внутрь которого помещаются данные переменной или результат вызова метода. Когда исполнение метода завершается, его элемент удаляется.

Чтобы воспроизвести эту ошибку, определим функцию recursion, которая будет рекурсивной — вызывать сама себя в бесконечном цикле. В результате появится ошибка StackOverflow или ошибка рекурсии, потому что стековый кадр будет заполняться данными метода из каждого вызова, но они не будут освобождаться.

def recursion():

return recursion()

recursion()

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

RecursionError Traceback (most recent call last)

in

----> 1 recursion()

in recursion()

1 def recursion():

----> 2 return recursion()

... last 1 frames repeated, from the frame below ...

in recursion()

1 def recursion():

----> 2 return recursion()

RecursionError: maximum recursion depth exceeded

Ошибка отступа (IndentationError)

Эта ошибка похожа по духу на синтаксическую и является ее подвидом. Тем не менее она возникает только в случае проблем с отступами.

Пример:

for i in range(10):

print('Привет Мир!')

File "", line 2

print('Привет Мир!')

^

IndentationError: expected an indented block

Исключения

Даже если синтаксис в инструкции или само выражение верны, они все равно могут вызывать ошибки при исполнении. Исключения Python — это ошибки, обнаруживаемые при исполнении, но не являющиеся критическими. Скоро вы узнаете, как справляться с ними в программах Python. Объект исключения создается при вызове исключения Python. Если скрипт не обрабатывает исключение явно, программа будет остановлена принудительно.

Программы обычно не обрабатывают исключения, что приводит к подобным сообщениям об ошибке:

Ошибка типа (TypeError)

a = 2

b = 'PythonRu'

a + b

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

in

1 a = 2

2 b = 'PythonRu'

----> 3 a + b

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str'

Ошибка деления на ноль (ZeroDivisionError)

10 / 0

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ZeroDivisionError Traceback (most recent call last)

in

----> 1 10 / 0

ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

Есть разные типы исключений в Python и их тип выводится в сообщении: вверху примеры TypeError и ZeroDivisionError. Обе строки в сообщениях об ошибке представляют собой имена встроенных исключений Python.

Оставшаяся часть строки с ошибкой предлагает подробности о причине ошибки на основе ее типа.

Теперь рассмотрим встроенные исключения Python.

Встроенные исключения

BaseException

+-- SystemExit

+-- KeyboardInterrupt

+-- GeneratorExit

+-- Exception

+-- StopIteration

+-- StopAsyncIteration

+-- ArithmeticError

| +-- FloatingPointError

| +-- OverflowError

| +-- ZeroDivisionError

+-- AssertionError

+-- AttributeError

+-- BufferError

+-- EOFError

+-- ImportError

| +-- ModuleNotFoundError

+-- LookupError

| +-- IndexError

| +-- KeyError

+-- MemoryError

+-- NameError

| +-- UnboundLocalError

+-- OSError

| +-- BlockingIOError

| +-- ChildProcessError

| +-- ConnectionError

| | +-- BrokenPipeError

| | +-- ConnectionAbortedError

| | +-- ConnectionRefusedError

| | +-- ConnectionResetError

| +-- FileExistsError

| +-- FileNotFoundError

| +-- InterruptedError

| +-- IsADirectoryError

| +-- NotADirectoryError

| +-- PermissionError

| +-- ProcessLookupError

| +-- TimeoutError

+-- ReferenceError

+-- RuntimeError

| +-- NotImplementedError

| +-- RecursionError

+-- SyntaxError

| +-- IndentationError

| +-- TabError

+-- SystemError

+-- TypeError

+-- ValueError

| +-- UnicodeError

| +-- UnicodeDecodeError

| +-- UnicodeEncodeError

| +-- UnicodeTranslateError

+-- Warning

+-- DeprecationWarning

+-- PendingDeprecationWarning

+-- RuntimeWarning

+-- SyntaxWarning

+-- UserWarning

+-- FutureWarning

+-- ImportWarning

+-- UnicodeWarning

+-- BytesWarning

+-- ResourceWarning

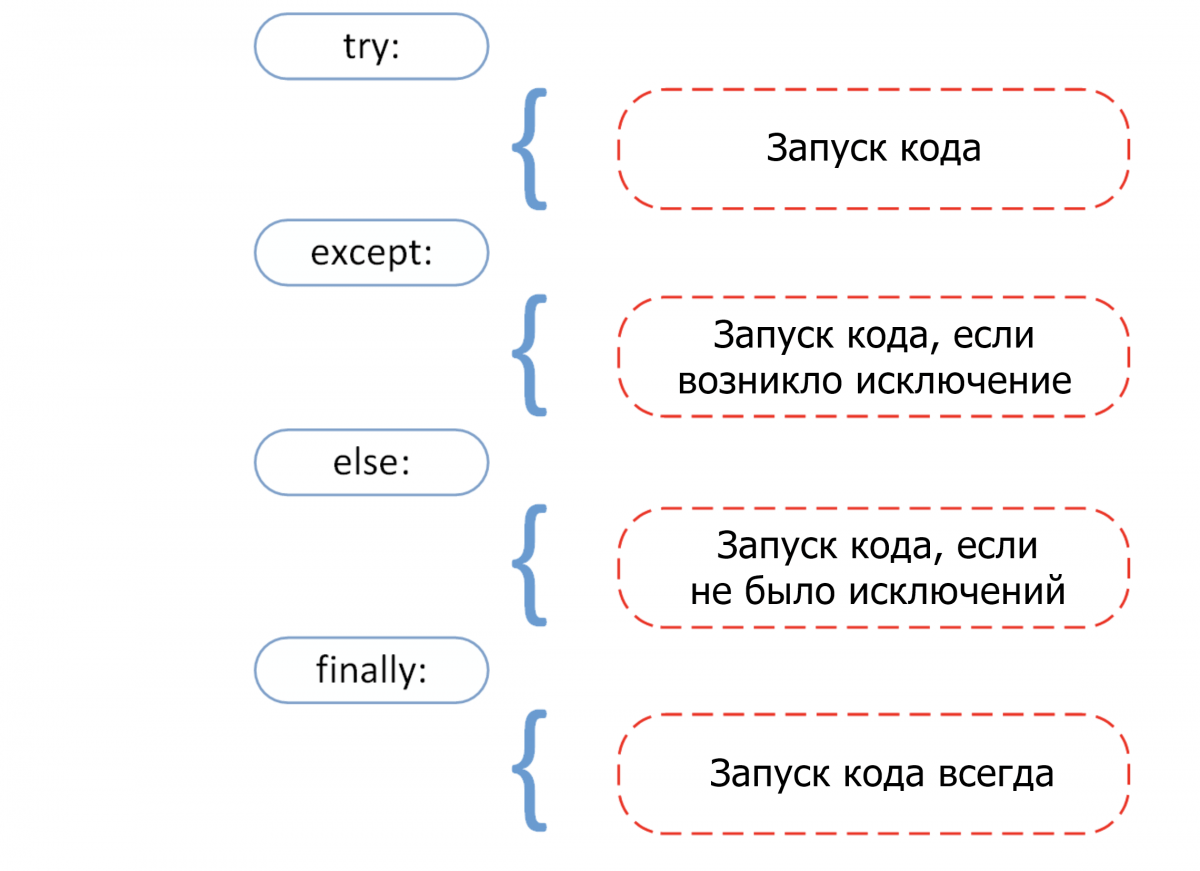

Прежде чем переходить к разбору встроенных исключений быстро вспомним 4 основных компонента обработки исключения, как показано на этой схеме.

Try: он запускает блок кода, в котором ожидается ошибка.Except: здесь определяется тип исключения, который ожидается в блокеtry(встроенный или созданный).Else: если исключений нет, тогда исполняется этот блок (его можно воспринимать как средство для запуска кода в том случае, если ожидается, что часть кода приведет к исключению).Finally: вне зависимости от того, будет ли исключение или нет, этот блок кода исполняется всегда.

В следующем разделе руководства больше узнаете об общих типах исключений и научитесь обрабатывать их с помощью инструмента обработки исключения.

Ошибка прерывания с клавиатуры (KeyboardInterrupt)

Исключение KeyboardInterrupt вызывается при попытке остановить программу с помощью сочетания Ctrl + C или Ctrl + Z в командной строке или ядре в Jupyter Notebook. Иногда это происходит неумышленно и подобная обработка поможет избежать подобных ситуаций.

В примере ниже если запустить ячейку и прервать ядро, программа вызовет исключение KeyboardInterrupt. Теперь обработаем исключение KeyboardInterrupt.

try:

inp = input()

print('Нажмите Ctrl+C и прервите Kernel:')

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print('Исключение KeyboardInterrupt')

else:

print('Исключений не произошло')

Исключение KeyboardInterrupt

Стандартные ошибки (StandardError)

Рассмотрим некоторые базовые ошибки в программировании.

Арифметические ошибки (ArithmeticError)

- Ошибка деления на ноль (Zero Division);

- Ошибка переполнения (OverFlow);

- Ошибка плавающей точки (Floating Point);

Все перечисленные выше исключения относятся к классу Arithmetic и вызываются при ошибках в арифметических операциях.

Деление на ноль (ZeroDivisionError)

Когда делитель (второй аргумент операции деления) или знаменатель равны нулю, тогда результатом будет ошибка деления на ноль.

try:

a = 100 / 0

print(a)

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("Исключение ZeroDivisionError." )

else:

print("Успех, нет ошибок!")

Исключение ZeroDivisionError.

Переполнение (OverflowError)

Ошибка переполнение вызывается, когда результат операции выходил за пределы диапазона. Она характерна для целых чисел вне диапазона.

try:

import math

print(math.exp(1000))

except OverflowError:

print("Исключение OverFlow.")

else:

print("Успех, нет ошибок!")

Исключение OverFlow.

Ошибка утверждения (AssertionError)

Когда инструкция утверждения не верна, вызывается ошибка утверждения.

Рассмотрим пример. Предположим, есть две переменные: a и b. Их нужно сравнить. Чтобы проверить, равны ли они, необходимо использовать ключевое слово assert, что приведет к вызову исключения Assertion в том случае, если выражение будет ложным.

try:

a = 100

b = "PythonRu"

assert a == b

except AssertionError:

print("Исключение AssertionError.")

else:

print("Успех, нет ошибок!")

Исключение AssertionError.

Ошибка атрибута (AttributeError)

При попытке сослаться на несуществующий атрибут программа вернет ошибку атрибута. В следующем примере можно увидеть, что у объекта класса Attributes нет атрибута с именем attribute.

class Attributes(obj):

a = 2

print(a)

try:

obj = Attributes()

print(obj.attribute)

except AttributeError:

print("Исключение AttributeError.")

2

Исключение AttributeError.

Ошибка импорта (ModuleNotFoundError)

Ошибка импорта вызывается при попытке импортировать несуществующий (или неспособный загрузиться) модуль в стандартном пути или даже при допущенной ошибке в имени.

import nibabel

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ModuleNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

in

----> 1 import nibabel

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'nibabel'

Ошибка поиска (LookupError)

LockupError выступает базовым классом для исключений, которые происходят, когда key или index используются для связывания или последовательность списка/словаря неверна или не существует.

Здесь есть два вида исключений:

- Ошибка индекса (

IndexError); - Ошибка ключа (

KeyError);

Ошибка ключа

Если ключа, к которому нужно получить доступ, не оказывается в словаре, вызывается исключение KeyError.

try:

a = {1:'a', 2:'b', 3:'c'}

print(a[4])

except LookupError:

print("Исключение KeyError.")

else:

print("Успех, нет ошибок!")

Исключение KeyError.

Ошибка индекса

Если пытаться получить доступ к индексу (последовательности) списка, которого не существует в этом списке или находится вне его диапазона, будет вызвана ошибка индекса (IndexError: list index out of range python).

try:

a = ['a', 'b', 'c']

print(a[4])

except LookupError:

print("Исключение IndexError, индекс списка вне диапазона.")

else:

print("Успех, нет ошибок!")

Исключение IndexError, индекс списка вне диапазона.

Ошибка памяти (MemoryError)

Как уже упоминалось, ошибка памяти вызывается, когда операции не хватает памяти для выполнения.

Ошибка имени (NameError)

Ошибка имени возникает, когда локальное или глобальное имя не находится.

В следующем примере переменная ans не определена. Результатом будет ошибка NameError.

try:

print(ans)

except NameError:

print("NameError: переменная 'ans' не определена")

else:

print("Успех, нет ошибок!")

NameError: переменная 'ans' не определена

Ошибка выполнения (Runtime Error)

Ошибка «NotImplementedError»

Ошибка выполнения служит базовым классом для ошибки NotImplemented. Абстрактные методы определенного пользователем класса вызывают это исключение, когда производные методы перезаписывают оригинальный.

class BaseClass(object):

"""Опередляем класс"""

def __init__(self):

super(BaseClass, self).__init__()

def do_something(self):

# функция ничего не делает

raise NotImplementedError(self.__class__.__name__ + '.do_something')

class SubClass(BaseClass):

"""Реализует функцию"""

def do_something(self):

# действительно что-то делает

print(self.__class__.__name__ + ' что-то делает!')

SubClass().do_something()

BaseClass().do_something()

SubClass что-то делает!

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NotImplementedError Traceback (most recent call last)

in

14

15 SubClass().do_something()

---> 16 BaseClass().do_something()

in do_something(self)

5 def do_something(self):

6 # функция ничего не делает

----> 7 raise NotImplementedError(self.__class__.__name__ + '.do_something')

8

9 class SubClass(BaseClass):

NotImplementedError: BaseClass.do_something

Ошибка типа (TypeError)

Ошибка типа вызывается при попытке объединить два несовместимых операнда или объекта.

В примере ниже целое число пытаются добавить к строке, что приводит к ошибке типа.

try:

a = 5

b = "PythonRu"

c = a + b

except TypeError:

print('Исключение TypeError')

else:

print('Успех, нет ошибок!')

Исключение TypeError

Ошибка значения (ValueError)

Ошибка значения вызывается, когда встроенная операция или функция получают аргумент с корректным типом, но недопустимым значением.

В этом примере встроенная операция float получат аргумент, представляющий собой последовательность символов (значение), что является недопустимым значением для типа: число с плавающей точкой.

try:

print(float('PythonRu'))

except ValueError:

print('ValueError: не удалось преобразовать строку в float: 'PythonRu'')

else:

print('Успех, нет ошибок!')

ValueError: не удалось преобразовать строку в float: 'PythonRu'

Пользовательские исключения в Python

В Python есть много встроенных исключений для использования в программе. Но иногда нужно создавать собственные со своими сообщениями для конкретных целей.

Это можно сделать, создав новый класс, который будет наследовать из класса Exception в Python.

class UnAcceptedValueError(Exception):

def __init__(self, data):

self.data = data

def __str__(self):

return repr(self.data)

Total_Marks = int(input("Введите общее количество баллов: "))

try:

Num_of_Sections = int(input("Введите количество разделов: "))

if(Num_of_Sections < 1):

raise UnAcceptedValueError("Количество секций не может быть меньше 1")

except UnAcceptedValueError as e:

print("Полученная ошибка:", e.data)

Введите общее количество баллов: 10

Введите количество разделов: 0

Полученная ошибка: Количество секций не может быть меньше 1

В предыдущем примере если ввести что-либо меньше 1, будет вызвано исключение. Многие стандартные исключения имеют собственные исключения, которые вызываются при возникновении проблем в работе их функций.

Недостатки обработки исключений в Python

У использования исключений есть свои побочные эффекты, как, например, то, что программы с блоками try-except работают медленнее, а количество кода возрастает.

Дальше пример, где модуль Python timeit используется для проверки времени исполнения 2 разных инструкций. В stmt1 для обработки ZeroDivisionError используется try-except, а в stmt2 — if. Затем они выполняются 10000 раз с переменной a=0. Суть в том, чтобы показать разницу во времени исполнения инструкций. Так, stmt1 с обработкой исключений занимает больше времени чем stmt2, который просто проверяет значение и не делает ничего, если условие не выполнено.

Поэтому стоит ограничить использование обработки исключений в Python и применять его в редких случаях. Например, когда вы не уверены, что будет вводом: целое или число с плавающей точкой, или не уверены, существует ли файл, который нужно открыть.

import timeit

setup="a=0"

stmt1 = '''

try:

b=10/a

except ZeroDivisionError:

pass'''

stmt2 = '''

if a!=0:

b=10/a'''

print("time=",timeit.timeit(stmt1,setup,number=10000))

print("time=",timeit.timeit(stmt2,setup,number=10000))

time= 0.003897680000136461

time= 0.0002797570000439009

Выводы!

Как вы могли увидеть, обработка исключений помогает прервать типичный поток программы с помощью специального механизма, который делает код более отказоустойчивым.

Обработка исключений — один из основных факторов, который делает код готовым к развертыванию. Это простая концепция, построенная всего на 4 блоках: try выискивает исключения, а except их обрабатывает.

Очень важно поупражняться в их использовании, чтобы сделать свой код более отказоустойчивым.

No matter your skill as a programmer, you will eventually make a coding mistake.

Such mistakes come in three basic flavors:

- Syntax errors: Errors where the code is not valid Python (generally easy to fix)

- Runtime errors: Errors where syntactically valid code fails to execute, perhaps due to invalid user input (sometimes easy to fix)

- Semantic errors: Errors in logic: code executes without a problem, but the result is not what you expect (often very difficult to track-down and fix)

Here we’re going to focus on how to deal cleanly with runtime errors.

As we’ll see, Python handles runtime errors via its exception handling framework.

Runtime Errors¶

If you’ve done any coding in Python, you’ve likely come across runtime errors.

They can happen in a lot of ways.

For example, if you try to reference an undefined variable:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- NameError Traceback (most recent call last) <ipython-input-3-e796bdcf24ff> in <module>() ----> 1 print(Q) NameError: name 'Q' is not defined

Or if you try an operation that’s not defined:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- TypeError Traceback (most recent call last) <ipython-input-4-aab9e8ede4f7> in <module>() ----> 1 1 + 'abc' TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str'

Or you might be trying to compute a mathematically ill-defined result:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- ZeroDivisionError Traceback (most recent call last) <ipython-input-5-ae0c5d243292> in <module>() ----> 1 2 / 0 ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

Or maybe you’re trying to access a sequence element that doesn’t exist:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- IndexError Traceback (most recent call last) <ipython-input-6-06b6eb1b8957> in <module>() 1 L = [1, 2, 3] ----> 2 L[1000] IndexError: list index out of range

Note that in each case, Python is kind enough to not simply indicate that an error happened, but to spit out a meaningful exception that includes information about what exactly went wrong, along with the exact line of code where the error happened.

Having access to meaningful errors like this is immensely useful when trying to trace the root of problems in your code.

Catching Exceptions: try and except¶

The main tool Python gives you for handling runtime exceptions is the try…except clause.

Its basic structure is this:

In [7]:

try: print("this gets executed first") except: print("this gets executed only if there is an error")

Note that the second block here did not get executed: this is because the first block did not return an error.

Let’s put a problematic statement in the try block and see what happens:

In [8]:

try: print("let's try something:") x = 1 / 0 # ZeroDivisionError except: print("something bad happened!")

let's try something: something bad happened!

Here we see that when the error was raised in the try statement (in this case, a ZeroDivisionError), the error was caught, and the except statement was executed.

One way this is often used is to check user input within a function or another piece of code.

For example, we might wish to have a function that catches zero-division and returns some other value, perhaps a suitably large number like $10^{100}$:

In [9]:

def safe_divide(a, b): try: return a / b except: return 1E100

There is a subtle problem with this code, though: what happens when another type of exception comes up? For example, this is probably not what we intended:

Dividing an integer and a string raises a TypeError, which our over-zealous code caught and assumed was a ZeroDivisionError!

For this reason, it’s nearly always a better idea to catch exceptions explicitly:

In [13]:

def safe_divide(a, b): try: return a / b except ZeroDivisionError: return 1E100

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- TypeError Traceback (most recent call last) <ipython-input-15-2331af6a0acf> in <module>() ----> 1 safe_divide(1, '2') <ipython-input-13-10b5f0163af8> in safe_divide(a, b) 1 def safe_divide(a, b): 2 try: ----> 3 return a / b 4 except ZeroDivisionError: 5 return 1E100 TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for /: 'int' and 'str'

We’re now catching zero-division errors only, and letting all other errors pass through un-modified.

Raising Exceptions: raise¶

We’ve seen how valuable it is to have informative exceptions when using parts of the Python language.

It’s equally valuable to make use of informative exceptions within the code you write, so that users of your code (foremost yourself!) can figure out what caused their errors.

The way you raise your own exceptions is with the raise statement. For example:

In [16]:

raise RuntimeError("my error message")

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- RuntimeError Traceback (most recent call last) <ipython-input-16-c6a4c1ed2f34> in <module>() ----> 1 raise RuntimeError("my error message") RuntimeError: my error message

As an example of where this might be useful, let’s return to our fibonacci function that we defined previously:

In [17]:

def fibonacci(N): L = [] a, b = 0, 1 while len(L) < N: a, b = b, a + b L.append(a) return L

One potential problem here is that the input value could be negative.

This will not currently cause any error in our function, but we might want to let the user know that a negative N is not supported.

Errors stemming from invalid parameter values, by convention, lead to a ValueError being raised:

In [18]:

def fibonacci(N): if N < 0: raise ValueError("N must be non-negative") L = [] a, b = 0, 1 while len(L) < N: a, b = b, a + b L.append(a) return L

Out[19]:

[1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55]

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- ValueError Traceback (most recent call last) <ipython-input-20-3d291499cfa7> in <module>() ----> 1 fibonacci(-10) <ipython-input-18-01d0cf168d63> in fibonacci(N) 1 def fibonacci(N): 2 if N < 0: ----> 3 raise ValueError("N must be non-negative") 4 L = [] 5 a, b = 0, 1 ValueError: N must be non-negative

Now the user knows exactly why the input is invalid, and could even use a try…except block to handle it!

In [21]:

N = -10 try: print("trying this...") print(fibonacci(N)) except ValueError: print("Bad value: need to do something else")

trying this... Bad value: need to do something else

Diving Deeper into Exceptions¶

Briefly, I want to mention here some other concepts you might run into.

I’ll not go into detail on these concepts and how and why to use them, but instead simply show you the syntax so you can explore more on your own.

Accessing the error message¶

Sometimes in a try…except statement, you would like to be able to work with the error message itself.

This can be done with the as keyword:

In [22]:

try: x = 1 / 0 except ZeroDivisionError as err: print("Error class is: ", type(err)) print("Error message is:", err)

Error class is: <class 'ZeroDivisionError'> Error message is: division by zero

With this pattern, you can further customize the exception handling of your function.

Defining custom exceptions¶

In addition to built-in exceptions, it is possible to define custom exceptions through class inheritance.

For instance, if you want a special kind of ValueError, you can do this:

In [23]:

class MySpecialError(ValueError): pass raise MySpecialError("here's the message")

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- MySpecialError Traceback (most recent call last) <ipython-input-23-92c36e04a9d0> in <module>() 2 pass 3 ----> 4 raise MySpecialError("here's the message") MySpecialError: here's the message

This would allow you to use a try…except block that only catches this type of error:

In [24]:

try: print("do something") raise MySpecialError("[informative error message here]") except MySpecialError: print("do something else")

do something do something else

You might find this useful as you develop more customized code.

try…except…else…finally¶

In addition to try and except, you can use the else and finally keywords to further tune your code’s handling of exceptions.

The basic structure is this:

In [25]:

try: print("try something here") except: print("this happens only if it fails") else: print("this happens only if it succeeds") finally: print("this happens no matter what")

try something here this happens only if it succeeds this happens no matter what

The utility of else here is clear, but what’s the point of finally?

Well, the finally clause really is executed no matter what: I usually see it used to do some sort of cleanup after an operation completes.

- Home

- Python Tutorial

- Exception Handling in Python

Last updated on September 22, 2020

Exception handling is a mechanism which allows us to handle errors gracefully while the program is running instead of abruptly ending the program execution.

Runtime Errors #

Runtime errors are the errors which happens while the program is running. Note is that runtime errors do not indicate there is a problem in the structure (or syntax) of the program. When runtime errors occurs Python interpreter perfectly understands your statement but it just can’t execute it. However, Syntax Errors occurs due to incorrect structure of the program. Both type of errors halts the execution of the program as soon as they are encountered and displays an error message (or traceback) explaining the probable cause of the problem.

The following are some examples of runtime errors.

Example 1: Division by a zero.

>>> >>> 2/0 Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> ZeroDivisionError: division by zero >>> |

Try it now

Example 2: Adding string to an integer.

>>> >>> 10 + "12" Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str' >>> |

Try it now

Example 3: Trying to access element at invalid index.

>>> >>> list1 = [11, 3, 99, 15] >>> >>> list1[10] Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> IndexError: list index out of range >>> |

Try it now

Example 4: Opening a file in read mode which doesn’t exist.

>>> >>> f = open("filedoesntexists.txt", "r") Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> FileNotFoundError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'filedoesntexists.txt' >>> >>> |

Try it now

Again note that all the above statements are syntactically valid, the only problem is that when Python tries to execute them, they got into an invalid state.

An error which occur while the program is running is known as an exception. When this happens, we say Python has raised an exception or an exception is thrown. Whenever such errors happen, Python creates a special type of object which contains all the relevant information about the error just occurred. For example, it contains a line number at which the error occurred, error messages (remember it is called traceback) and so on. By default, these errors simply halts the execution of the program. Exception handling mechanism allows us to deal with such errors gracefully without halting the program.

try-except statement #

In Python, we use try-except statement for exception handling. Its syntax is as follows:

try: # try block # write code that might raise an exception here <statement_1> <statement_2> except ExceptiomType: # except block # handle exception here <handler> |

The code begins with the word try, which is a reserved keyword, followed by a colon (:). In the next line we have try block. The try block contains code that might raise an exception. After that, we have an except clause that starts with the word except, which is again a reserved keyword, followed by an exception type and a colon (:). In the next line, we have an except block. The except block contains code to handle the exception. As usual, code inside the try and except block must be properly indented, otherwise, you will get an error.

Here is how the try-except statement executes:

When an exception occurs in the try block, the execution of the rest of the statements in the try block is skipped. If the exception raised matches the exception type in the except clause, the corresponding handler is executed.

If the exception raised in the try block doesn’t matches with the exception type specified in the except clause the program halts with a traceback.

On the other hand, If no exception is raised in the try block, the except clause is skipped.

Let’s take an example:

python101/Chapter-19/exception_handling.py

try: num = int(input("Enter a number: ")) result = 10/num print("Result: ", result) except ZeroDivisionError: print("Exception Handler for ZeroDivisionError") print("We cant divide a number by 0") |

Try it now

Run the program and enter 0.

First run output:

Enter a number: 0 Exception Handler for ZeroDivisionError We cant divide a number by 0 |

In this example, the try block in line 3 raises a ZeroDivisionError. When an exception occurs Python looks for the except clause with the matching exception type. In this case, it finds one and runs the exception handler code in that block. Notice that because an exception is raised in line 3, the execution of reset of the statements in the try block is skipped.

Run the program again but this time enter a string instead of a number:

Second run output:

Enter a number: str

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "exception_example.py", line 2, in <module>

num = int(input("Enter a number: "))

ValueError: invalid literal for int() with base 10: 'str'

|

This time our program crashes with the ValueError exception. The problem is that the built-in int() only works with strings that contain numbers only, if you pass a string containing non-numeric character it will throw a ValueError exception.

>>> >>> int("123") // that's fine because string only contains numbers 123 >>> >>> int("str") // error can't converts characters to numbers Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> ValueError: invalid literal for int() with base 10: 'str' >>> |

As we have don’t have an except clause with the ValueError exception, our program crashes with ValueError exception.

Run the program again and this time enter an integer other than 0.

Third run output:

Enter a number: 4 Result: 2.5 |

Try it now

In this case, statements in the try block executes without throwing any exception, as a result, the except clause is skipped.

Handling Multiple Exceptions #

We can add as many except clause as we want to handle different types of exceptions. The general format of such a try-except statement is as follows:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 |

try: # try block # write code that might raise an exception here <statement_1> <statement_2> except <ExceptiomType1>: # except block # handle ExceptiomType1 here <handler> except <ExceptiomType2>: # except block # handle ExceptiomType2 here <handler> except <ExceptiomType2>: # except block # handle ExceptiomType3 here <handler> except: # handle any type of exception here <handler> |

Here is how it works:

When an exception occurs, Python matches the exception raised against every except clause sequentially. If a match is found then the handler in the corresponding except clause is executed and rest of the except clauses are skipped.

In case the exception raised doesn’t matches any except clause before the last except clause (line 18), then the handler in the last except clause is executed. Note that the last except clause doesn’t have any exception type in front of it, as a result, it can catch any type of exception. Of course, this last except clause is entirely optional but we commonly use it as a last resort to catch the unexpected errors and thus prevent the program from crashing.

The following program demonstrates how to use multiple except clauses.

python101/Chapter-19/handling_muliple_types_of_exceptions.py

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

try: num1 = int(input("Enter a num1: ")) num2 = int(input("Enter a num2: ")) result = num1 / num2 print("Result: ", result) except ZeroDivisionError: print("nException Handler for ZeroDivisionError") print("We cant divide a number by 0") except ValueError: print("nException Handler for ValueError") print("Invalid input: Only integers are allowed") except: print("nSome unexpected error occurred") |

Try it now

First run output:

Enter a num1: 10 Enter a num2: 0 Exception Handler for ZeroDivisionError We cant divide a number by 0 |

Second run output:

Enter a num1: 100 Enter a num2: a13 Exception Handler for ValueError Invalid input: Only integers are allowed |

Third run output:

Enter a num1: 5000 Enter a num2: 2 Result: 2500 |

Here is another example program that asks the user to enter the filename and then prints the content of the file to the console.

python101/Chapter-19/exception_handling_while_reading_file.py

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 |

filename = input("Enter file name: ") try: f = open(filename, "r") for line in f: print(line, end="") f.close() except FileNotFoundError: print("File not found") except PermissionError: print("You don't have the permission to read the file") except: print("Unexpected error while reading the file") |

Try it now

Run the program and specify a file that doesn’t exist.

First run output:

Enter file name: file_doesnt_exists.md File not found |

Run the program again and this time specify a file that you don’t have permission to read.

Second run output:

Enter file name: /etc/passwd You don't have the permission to read the file |

Run the program once more but this time specify a file that does exist and you have the permission to read it.

Third run output:

Enter file name: ../Chapter-18/readme.md First Line Second Line Third Line Fourth Line Fifth Line |

The else and finally clause #

A try-except statement can also have an optional else clause which only gets executed when no exception is raised. The general format of try-except statement with else clause is as follows:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

try: <statement_1> <statement_2> except <ExceptiomType1>: <handler> except <ExceptiomType2>: <handler> else: # else block only gets executed # when no exception is raised in the try block <statement> <statement> |

Here is a rewrite of the above program using the else clause.

python101/Chapter-19/else_clause_demo.py

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 |

import os filename = input("Enter file name: ") try: f = open(filename, "r") for line in f: print(line, end="") f.close() except FileNotFoundError: print("File not found") except PermissionError: print("You don't have the permission to read the file") except FileExistsError: print("You don't have the permission to read the file") except: print("Unexpected error while reading the file") else: print("Program ran without any problem") |

Try it now

Run the program and enter a file that doesn’t exist.

First run output:

Enter file name: terraform.txt File not found |

Again run the program but this time enter a file that does exist and you have the permission to access it.

Second run output:

Enter file name: ../Chapter-18/readme.md First Line Second Line Third Line Fourth Line Fifth Line Program ran without any problem |

As expected, the statement in the else clause is executed this time. The else clause is usually used to write code which we want to run after the code in the try block ran successfully.

Similarly, we can have a finally clause after all except clauses. The statements under the finally clause will always execute irrespective of whether the exception is raised or not. It’s general form is as follows:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

try: <statement_1> <statement_2> except <ExceptiomType1>: <handler> except <ExceptiomType2>: <handler> finally: # statements here will always # execute no matter what <statement> <statement> |

The finally clause is commonly used to define clean up actions that must be performed under any circumstance. If the try-except statement has an else clause then the finally clause must appear after it.

The following program shows the finally clause in action.

python101/Chapter-19/finally_clause_demo.py

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 |

import os filename = input("Enter file name: ") try: f = open(filename, "r") for line in f: print(line, end="") f.close() except FileNotFoundError: print("File not found") except PermissionError: print("You don't have the permission to read the file") except FileExistsError: print("You don't have the permission to read the file") except: print("Unexpected error while reading the file") else: print("nProgram ran without any problem") finally: print("finally clause: This will always execute") |

Try it now

First run output:

Enter file name: little.txt File not found finally clause: This will always execute |

Second run output:

Enter file name: readme.md First Line Second Line Third Line Fourth Line Fifth Line Program ran without any problem finally clause: This will always execute |

Exceptions Propagation and Raising Exceptions #

In the earlier few sections, we have learned how to deal with exceptions using the try-except statement. In this section, we will discuss who throws an exception, how to create an exception and how they propagate.

An exception is simply an object raised by a function signaling that something unexpected has happened which the function itself can’t handle. A function raises exception by creating an exception object from an appropriate class and then throws the exception to the calling code using the raise keyword as follows:

raise SomeExceptionClas("Error message describing cause of the error")

We can raise exceptions from our own functions by creating an instance of RuntimeError() as follows:

raise RuntimeError("Someting went very wrong")

When an exception is raised inside a function and is not caught there, it is automatically propagated to the calling function (and any function up in the stack), until it is caught by try-except statement in some calling function. If the exception reaches the main module and still not handled, the program terminates with an error message.

Let’s take an example.

Suppose we are creating a function to calculate factorial of a number. As factorial is only valid for positive integers, passing data of any other type would render the function useless. We can prevent this by checking the type of argument and raising an exception if the argument is not a positive integer. Here is the complete code.

python101/Chapter-19/factorial.py

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

def factorial(n): if not isinstance(n, int): raise RuntimeError("Argument must be int") if n < 0: raise RuntimeError("Argument must be >= 0") f = 1 for i in range(n): f *= n n -= 1 return f try: print("Factorial of 4 is:", factorial(4)) print("Factorial of 12 is:", factorial("12")) except RuntimeError: print("Invalid Input") |

Try it now

Output:

Factorial of 4 is: 24 Invalid Input |

Notice that when the factorial() function is called with a string argument (line 17), a runtime exception is raised in line 3. As factorial() function is not handling the exception, the raised exception is propagated back to the main module where it is caught by the except clause in line 18.

Note that in the above example we have coded the try-except statement outside the factorial() function but we could have easily done the same inside the factorial() function as follows.

python101/Chapter-19/handling_exception_inside_factorial_func.py

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 |

def factorial(n): try: if not isinstance(n, int): raise RuntimeError("Argument must be int") if n < 0: raise RuntimeError("Argument must be >= 0") f = 1 for i in range(n): f *= n n -= 1 return f except RuntimeError: return "Invalid Input" print("Factorial of 4 is:", factorial(4)) print("Factorial of 12 is:", factorial("12")) |

Try it now

Output:

Factorial of 4 is: 24 Factorial of 12 is: Invalid Input |

However, this is not recommended. Generally, the called function throws an exception to the caller and it’s the duty of the calling code to handle the exception. This approach allows us to to handle exceptions in different ways, for example, in one case we show an error message to the user while in other we silently log the problem. If we were handling exceptions in the called function, then we would have to update the function every time a new behavior is required. In addition to that, all the functions in the Python standard library also conforms to this behavior. The library function only detects the problem and raises an exception and the client decide what it needs to be done to handle those errors.

Now Let’s see what happens when an exception is raised in a deeply nested function call. Recall that if an exception is raised inside the function and is not caught by the function itself, it is passed to its caller. This process repeats until it is caught by some calling function down in the stack. Consider the following example.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 |

def function3(): try: ... raise SomeException() statement7 except ExceptionType4: handler statement8 def function2(): try: ... function3() statement5 except ExceptionType3: handler statement6 def function1(): try: ... function2() statement3 except ExceptionType2: handler statement4 def main(): try: ... function1() statement1 except ExceptionType1: handler statement2 main() |

The program execution starts by calling the main() function. The main() function then invokes function1(), function1() invokes function2(), finally function2() invokes function3(). Let’s assume function3() can raise different types of exceptions. Now consider the following cases.

-

If the exception is of type

ExceptionType4,statement7is skipped and theexceptclause in line 7 catches it. The execution offunction3()proceeds as usual andstatement8is executed. -

If exception is of type