Python выводит трассировку (далее traceback), когда в вашем коде появляется ошибка. Вывод traceback может быть немного пугающим, если вы видите его впервые, или не понимаете, чего от вас хотят. Однако traceback Python содержит много информации, которая может помочь вам определить и исправить причину, из-за которой в вашем коде возникла ошибка.

Содержание статьи

- Traceback — Что это такое и почему оно появляется?

- Как правильно читать трассировку?

- Обзор трассировка Python

- Подробный обзор трассировки в Python

- Обзор основных Traceback исключений в Python

- AttributeError

- ImportError

- IndexError

- KeyError

- NameError

- SyntaxError

- TypeError

- ValueError

- Логирование ошибок из Traceback

- Вывод

Понимание того, какую информацию предоставляет traceback Python является основополагающим критерием того, как стать лучшим Python программистом.

К концу данной статьи вы сможете:

- Понимать, что несет за собой traceback

- Различать основные виды traceback

- Успешно вести журнал traceback, при этом исправить ошибку

Python Traceback — Как правильно читать трассировку?

Traceback (трассировка) — это отчет, который содержит вызовы выполненных функций в вашем коде в определенный момент.

Есть вопросы по Python?

На нашем форуме вы можете задать любой вопрос и получить ответ от всего нашего сообщества!

Telegram Чат & Канал

Вступите в наш дружный чат по Python и начните общение с единомышленниками! Станьте частью большого сообщества!

Паблик VK

Одно из самых больших сообществ по Python в социальной сети ВК. Видео уроки и книги для вас!

Traceback называют по разному, иногда они упоминаются как трассировка стэка, обратная трассировка, и так далее. В Python используется определение “трассировка”.

Когда ваша программа выдает ошибку, Python выводит текущую трассировку, чтобы подсказать вам, что именно пошло не так. Ниже вы увидите пример, демонстрирующий данную ситуацию:

|

def say_hello(man): print(‘Привет, ‘ + wrong_variable) say_hello(‘Иван’) |

Здесь say_hello() вызывается с параметром man. Однако, в say_hello() это имя переменной не используется. Это связано с тем, что оно написано по другому: wrong_variable в вызове print().

Обратите внимание: в данной статье подразумевается, что вы уже имеете представление об ошибках Python. Если это вам не знакомо, или вы хотите освежить память, можете ознакомиться с нашей статьей: Обработка ошибок в Python

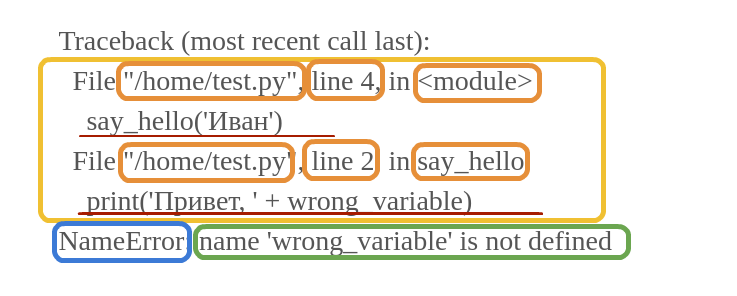

Когда вы запускаете эту программу, вы получите следующую трассировку:

|

Traceback (most recent call last): File «/home/test.py», line 4, in <module> say_hello(‘Иван’) File «/home/test.py», line 2, in say_hello print(‘Привет, ‘ + wrong_variable) NameError: name ‘wrong_variable’ is not defined Process finished with exit code 1 |

Эта выдача из traceback содержит массу информации, которая вам понадобится для определения проблемы. Последняя строка трассировки говорит нам, какой тип ошибки возник, а также дополнительная релевантная информация об ошибке. Предыдущие строки из traceback указывают на код, из-за которого возникла ошибка.

В traceback выше, ошибкой является NameError, она означает, что есть отсылка к какому-то имени (переменной, функции, класса), которое не было определено. В данном случае, ссылаются на имя wrong_variable.

Последняя строка содержит достаточно информации для того, чтобы вы могли решить эту проблему. Поиск переменной wrong_variable, и заменит её атрибутом из функции на man. Однако, скорее всего в реальном случае вы будете иметь дело с более сложным кодом.

Python Traceback — Как правильно понять в чем ошибка?

Трассировка Python содержит массу полезной информации, когда вам нужно определить причину ошибки, возникшей в вашем коде. В данном разделе, мы рассмотрим различные виды traceback, чтобы понять ключевые отличия информации, содержащейся в traceback.

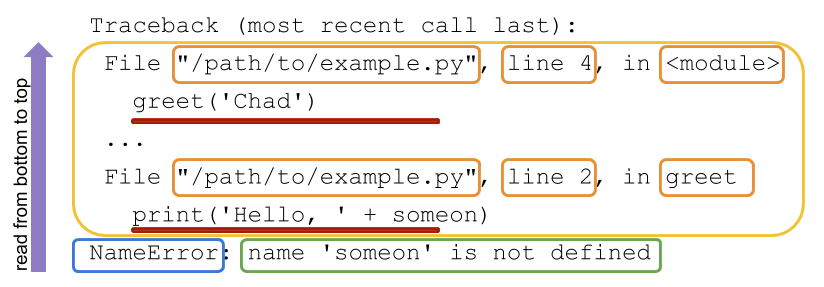

Существует несколько секций для каждой трассировки Python, которые являются крайне важными. Диаграмма ниже описывает несколько частей:

В Python лучше всего читать трассировку снизу вверх.

- Синее поле: последняя строка из traceback — это строка уведомления об ошибке. Синий фрагмент содержит название возникшей ошибки.

- Зеленое поле: после названия ошибки идет описание ошибки. Это описание обычно содержит полезную информацию для понимания причины возникновения ошибки.

- Желтое поле: чуть выше в трассировке содержатся различные вызовы функций. Снизу вверх — от самых последних, до самых первых. Эти вызовы представлены двухстрочными вводами для каждого вызова. Первая строка каждого вызова содержит такую информацию, как название файла, номер строки и название модуля. Все они указывают на то, где может быть найден код.

- Красное подчеркивание: вторая строка этих вызовов содержит непосредственный код, который был выполнен с ошибкой.

Есть ряд отличий между выдачей трассировок, когда вы запускает код в командной строке, и между запуском кода в REPL. Ниже вы можете видеть тот же код из предыдущего раздела, запущенного в REPL и итоговой выдачей трассировки:

|

Python 3.7.4 (default, Jul 16 2019, 07:12:58) [GCC 9.1.0] on linux Type «help», «copyright», «credits» or «license» for more information. >>> >>> >>> def say_hello(man): ... print(‘Привет, ‘ + wrong_variable) ... >>> say_hello(‘Иван’) Traceback (most recent call last): File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module> File «<stdin>», line 2, in say_hello NameError: name ‘wrong_variable’ is not defined |

Обратите внимание на то, что на месте названия файла вы увидите <stdin>. Это логично, так как вы выполнили код через стандартный ввод. Кроме этого, выполненные строки кода не отображаются в traceback.

Важно помнить: если вы привыкли видеть трассировки стэка в других языках программирования, то вы обратите внимание на явное различие с тем, как выглядит traceback в Python. Большая часть других языков программирования выводят ошибку в начале, и затем ведут сверху вниз, от недавних к последним вызовам.

Это уже обсуждалось, но все же: трассировки Python читаются снизу вверх. Это очень помогает, так как трассировка выводится в вашем терминале (или любым другим способом, которым вы читаете трассировку) и заканчивается в конце выдачи, что помогает последовательно структурировать прочтение из traceback и понять в чем ошибка.

Traceback в Python на примерах кода

Изучение отдельно взятой трассировки поможет вам лучше понять и увидеть, какая информация в ней вам дана и как её применить.

Код ниже используется в примерах для иллюстрации информации, данной в трассировке Python:

Мы запустили ниже предоставленный код в качестве примера и покажем какую информацию мы получили от трассировки.

Сохраняем данный код в файле greetings.py

|

def who_to_greet(person): return person if person else input(‘Кого приветствовать? ‘) def greet(someone, greeting=‘Здравствуйте’): print(greeting + ‘, ‘ + who_to_greet(someone)) def greet_many(people): for person in people: try: greet(person) except Exception: print(‘Привет, ‘ + person) |

Функция who_to_greet() принимает значение person и либо возвращает данное значение если оно не пустое, либо запрашивает значение от пользовательского ввода через input().

Далее, greet() берет имя для приветствия из someone, необязательное значение из greeting и вызывает print(). Также с переданным значением из someone вызывается who_to_greet().

Наконец, greet_many() выполнит итерацию по списку людей и вызовет greet(). Если при вызове greet() возникает ошибка, то выводится резервное приветствие print('hi, ' + person).

Этот код написан правильно, так что никаких ошибок быть не может при наличии правильного ввода.

Если вы добавите вызов функции greet() в конце нашего кода (которого сохранили в файл greetings.py) и дадите аргумент который он не ожидает (например, greet('Chad', greting='Хай')), то вы получите следующую трассировку:

|

$ python greetings.py Traceback (most recent call last): File «/home/greetings.py», line 19, in <module> greet(‘Chad’, greting=‘Yo’) TypeError: greet() got an unexpected keyword argument ‘greting’ |

Еще раз, в случае с трассировкой Python, лучше анализировать снизу вверх. Начиная с последней строки трассировки, вы увидите, что ошибкой является TypeError. Сообщения, которые следуют за типом ошибки, дают вам полезную информацию. Трассировка сообщает, что greet() вызван с аргументом, который не ожидался. Неизвестное название аргумента предоставляется в том числе, в нашем случае это greting.

Поднимаясь выше, вы можете видеть строку, которая привела к исключению. В данном случае, это вызов greet(), который мы добавили в конце greetings.py.

Следующая строка дает нам путь к файлу, в котором лежит код, номер строки этого файла, где вы можете найти код, и то, какой в нем модуль. В нашем случае, так как наш код не содержит никаких модулей Python, мы увидим только надпись , означающую, что этот файл является выполняемым.

С другим файлом и другим вводом, вы можете увидеть, что трассировка явно указывает вам на правильное направление, чтобы найти проблему. Следуя этой информации, мы удаляем злополучный вызов greet() в конце greetings.py, и добавляем следующий файл под названием example.py в папку:

|

from greetings import greet greet(1) |

Здесь вы настраиваете еще один файл Python, который импортирует ваш предыдущий модуль greetings.py, и используете его greet(). Вот что произойдете, если вы запустите example.py:

|

$ python example.py Traceback (most recent call last): File «/path/to/example.py», line 3, in <module> greet(1) File «/path/to/greetings.py», line 5, in greet print(greeting + ‘, ‘ + who_to_greet(someone)) TypeError: must be str, not int |

В данном случае снова возникает ошибка TypeError, но на этот раз уведомление об ошибки не очень помогает. Оно говорит о том, что где-то в коде ожидается работа со строкой, но было дано целое число.

Идя выше, вы увидите строку кода, которая выполняется. Затем файл и номер строки кода. На этот раз мы получаем имя функции, которая была выполнена — greet().

Поднимаясь к следующей выполняемой строке кода, мы видим наш проблемный вызов greet(), передающий целое число.

Иногда, после появления ошибки, другой кусок кода берет эту ошибку и также её выдает. В таких случаях, Python выдает все трассировки ошибки в том порядке, в котором они были получены, и все по тому же принципу, заканчивая на самой последней трассировке.

Так как это может сбивать с толку, рассмотрим пример. Добавим вызов greet_many() в конце greetings.py:

|

# greetings.py ... greet_many([‘Chad’, ‘Dan’, 1]) |

Это должно привести к выводу приветствия всем трем людям. Однако, если вы запустите этот код, вы увидите несколько трассировок в выдаче:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 |

$ python greetings.py Hello, Chad Hello, Dan Traceback (most recent call last): File «greetings.py», line 10, in greet_many greet(person) File «greetings.py», line 5, in greet print(greeting + ‘, ‘ + who_to_greet(someone)) TypeError: must be str, not int During handling of the above exception, another exception occurred: Traceback (most recent call last): File «greetings.py», line 14, in <module> greet_many([‘Chad’, ‘Dan’, 1]) File «greetings.py», line 12, in greet_many print(‘hi, ‘ + person) TypeError: must be str, not int |

Обратите внимание на выделенную строку, начинающуюся с “During handling in the output above”. Между всеми трассировками, вы ее увидите.

Это достаточно ясное уведомление: Пока ваш код пытался обработать предыдущую ошибку, возникла новая.

Обратите внимание: функция отображения предыдущих трассировок была добавлена в Python 3. В Python 2 вы можете получать только трассировку последней ошибки.

Вы могли видеть предыдущую ошибку, когда вызывали greet() с целым числом. Так как мы добавили 1 в список людей для приветствия, мы можем ожидать тот же результат. Однако, функция greet_many() оборачивает вызов greet() и пытается в блоке try и except. На случай, если greet() приведет к ошибке, greet_many() захочет вывести приветствие по-умолчанию.

Соответствующая часть greetings.py повторяется здесь:

|

def greet_many(people): for person in people: try: greet(person) except Exception: print(‘hi, ‘ + person) |

Когда greet() приводит к TypeError из-за неправильного ввода числа, greet_many() обрабатывает эту ошибку и пытается вывести простое приветствие. Здесь код приводит к другой, аналогичной ошибке. Он все еще пытается добавить строку и целое число.

Просмотр всей трассировки может помочь вам увидеть, что стало причиной ошибки. Иногда, когда вы получаете последнюю ошибку с последующей трассировкой, вы можете не увидеть, что пошло не так. В этих случаях, изучение предыдущих ошибок даст лучшее представление о корне проблемы.

Обзор основных Traceback исключений в Python 3

Понимание того, как читаются трассировки Python, когда ваша программа выдает ошибку, может быть очень полезным навыком, однако умение различать отдельные трассировки может заметно ускорить вашу работу.

Рассмотрим основные ошибки, с которыми вы можете сталкиваться, причины их появления и что они значат, а также информацию, которую вы можете найти в их трассировках.

Ошибка AttributeError object has no attribute [Решено]

AttributeError возникает тогда, когда вы пытаетесь получить доступ к атрибуту объекта, который не содержит определенного атрибута. Документация Python определяет, когда эта ошибка возникнет:

Возникает при вызове несуществующего атрибута или присвоение значения несуществующему атрибуту.

Пример ошибки AttributeError:

|

>>> an_int = 1 >>> an_int.an_attribute Traceback (most recent call last): File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module> AttributeError: ‘int’ object has no attribute ‘an_attribute’ |

Строка уведомления об ошибке для AttributeError говорит вам, что определенный тип объекта, в данном случае int, не имеет доступа к атрибуту, в нашем случае an_attribute. Увидев AttributeError в строке уведомления об ошибке, вы можете быстро определить, к какому атрибуту вы пытались получить доступ, и куда перейти, чтобы это исправить.

Большую часть времени, получение этой ошибки определяет, что вы возможно работаете с объектом, тип которого не является ожидаемым:

|

>>> a_list = (1, 2) >>> a_list.append(3) Traceback (most recent call last): File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module> AttributeError: ‘tuple’ object has no attribute ‘append’ |

В примере выше, вы можете ожидать, что a_list будет типом списка, который содержит метод .append(). Когда вы получаете ошибку AttributeError, и видите, что она возникла при попытке вызова .append(), это говорит о том, что вы, возможно, не работаете с типом объекта, который ожидаете.

Часто это происходит тогда, когда вы ожидаете, что объект вернется из вызова функции или метода и будет принадлежать к определенному типу, но вы получаете тип объекта None. В данном случае, строка уведомления об ошибке будет выглядеть так:

AttributeError: ‘NoneType’ object has no attribute ‘append’

Python Ошибка ImportError: No module named [Решено]

ImportError возникает, когда что-то идет не так с оператором import. Вы получите эту ошибку, или ее подкласс ModuleNotFoundError, если модуль, который вы хотите импортировать, не может быть найден, или если вы пытаетесь импортировать что-то, чего не существует во взятом модуле. Документация Python определяет, когда возникает эта ошибка:

Ошибка появляется, когда в операторе импорта возникают проблемы при попытке загрузить модуль. Также вызывается, при конструкции импорта

from listвfrom ... importимеет имя, которое невозможно найти.

Вот пример появления ImportError и ModuleNotFoundError:

|

>>> import asdf Traceback (most recent call last): File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module> ModuleNotFoundError: No module named ‘asdf’ >>> from collections import asdf Traceback (most recent call last): File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module> ImportError: cannot import name ‘asdf’ |

В примере выше, вы можете видеть, что попытка импорта модуля asdf, который не существует, приводит к ModuleNotFoundError. При попытке импорта того, что не существует (в нашем случае — asdf) из модуля, который существует (в нашем случае — collections), приводит к ImportError. Строки сообщения об ошибке трассировок указывают на то, какая вещь не может быть импортирована, в обоих случаях это asdf.

Ошибка IndexError: list index out of range [Решено]

IndexError возникает тогда, когда вы пытаетесь вернуть индекс из последовательности, такой как список или кортеж, и при этом индекс не может быть найден в последовательности. Документация Python определяет, где эта ошибка появляется:

Возникает, когда индекс последовательности находится вне диапазона.

Вот пример, который приводит к IndexError:

|

>>> a_list = [‘a’, ‘b’] >>> a_list[3] Traceback (most recent call last): File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module> IndexError: list index out of range |

Строка сообщения об ошибке для IndexError не дает вам полную информацию. Вы можете видеть, что у вас есть отсылка к последовательности, которая не доступна и то, какой тип последовательности рассматривается, в данном случае это список.

Иными словами, в списке a_list нет значения с ключом

3. Есть только значение с ключами0и1, этоaиbсоответственно.

Эта информация, в сочетании с остальной трассировкой, обычно является исчерпывающей для помощи программисту в быстром решении проблемы.

Возникает ошибка KeyError в Python 3 [Решено]

Как и в случае с IndexError, KeyError возникает, когда вы пытаетесь получить доступ к ключу, который отсутствует в отображении, как правило, это dict. Вы можете рассматривать его как IndexError, но для словарей. Из документации:

Возникает, когда ключ словаря не найден в наборе существующих ключей.

Вот пример появления ошибки KeyError:

|

>>> a_dict = [‘a’: 1, ‘w’: ‘2’] >>> a_dict[‘b’] Traceback (most recent call last): File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module> KeyError: ‘b’ |

Строка уведомления об ошибки KeyError говорит о ключе, который не может быть найден. Этого не то чтобы достаточно, но, если взять остальную часть трассировки, то у вас будет достаточно информации для решения проблемы.

Ошибка NameError: name is not defined в Python [Решено]

NameError возникает, когда вы ссылаетесь на название переменной, модуля, класса, функции, и прочего, которое не определено в вашем коде.

Документация Python дает понять, когда возникает эта ошибка NameError:

Возникает, когда локальное или глобальное название не было найдено.

В коде ниже, greet() берет параметр person. Но в самой функции, этот параметр был назван с ошибкой, persn:

|

>>> def greet(person): ... print(f‘Hello, {persn}’) >>> greet(‘World’) Traceback (most recent call last): File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module> File «<stdin>», line 2, in greet NameError: name ‘persn’ is not defined |

Строка уведомления об ошибке трассировки NameError указывает вам на название, которое мы ищем. В примере выше, это названная с ошибкой переменная или параметр функции, которые были ей переданы.

NameError также возникнет, если берется параметр, который мы назвали неправильно:

|

>>> def greet(persn): ... print(f‘Hello, {person}’) >>> greet(‘World’) Traceback (most recent call last): File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module> File «<stdin>», line 2, in greet NameError: name ‘person’ is not defined |

Здесь все выглядит так, будто вы сделали все правильно. Последняя строка, которая была выполнена, и на которую ссылается трассировка выглядит хорошо.

Если вы окажетесь в такой ситуации, то стоит пройтись по коду и найти, где переменная person была использована и определена. Так вы быстро увидите, что название параметра введено с ошибкой.

Ошибка SyntaxError: invalid syntax в Python [Решено]

Возникает, когда синтаксический анализатор обнаруживает синтаксическую ошибку.

Ниже, проблема заключается в отсутствии двоеточия, которое должно находиться в конце строки определения функции. В REPL Python, эта ошибка синтаксиса возникает сразу после нажатия Enter:

|

>>> def greet(person) File «<stdin>», line 1 def greet(person) ^ SyntaxError: invalid syntax |

Строка уведомления об ошибке SyntaxError говорит вам только, что есть проблема с синтаксисом вашего кода. Просмотр строк выше укажет вам на строку с проблемой. Каретка ^ обычно указывает на проблемное место. В нашем случае, это отсутствие двоеточия в операторе def нашей функции.

Стоит отметить, что в случае с трассировками SyntaxError, привычная первая строка Tracebak (самый последний вызов) отсутствует. Это происходит из-за того, что SyntaxError возникает, когда Python пытается парсить ваш код, но строки фактически не выполняются.

Ошибка TypeError в Python 3 [Решено]

TypeError возникает, когда ваш код пытается сделать что-либо с объектом, который не может этого выполнить, например, попытка добавить строку в целое число, или вызвать len() для объекта, в котором не определена длина.

Ошибка возникает, когда операция или функция применяется к объекту неподходящего типа.

Рассмотрим несколько примеров того, когда возникает TypeError:

|

>>> 1 + ‘1’ Traceback (most recent call last): File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module> TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: ‘int’ and ‘str’ >>> ‘1’ + 1 Traceback (most recent call last): File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module> TypeError: must be str, not int >>> len(1) Traceback (most recent call last): File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module> TypeError: object of type ‘int’ has no len() |

Указанные выше примеры возникновения TypeError приводят к строке уведомления об ошибке с разными сообщениями. Каждое из них весьма точно информирует вас о том, что пошло не так.

В первых двух примерах мы пытаемся внести строки и целые числа вместе. Однако, они немного отличаются:

- В первом примере мы пытаемся добавить

strкint. - Во втором примере мы пытаемся добавить

intкstr.

Уведомления об ошибке указывают на эти различия.

Последний пример пытается вызвать len() для int. Сообщение об ошибке говорит нам, что мы не можем сделать это с int.

Возникла ошибка ValueError в Python 3 [Решено]

ValueError возникает тогда, когда значение объекта не является корректным. Мы можем рассматривать это как IndexError, которая возникает из-за того, что значение индекса находится вне рамок последовательности, только ValueError является более обобщенным случаем.

Возникает, когда операция или функция получает аргумент, который имеет правильный тип, но неправильное значение, и ситуация не описывается более детальной ошибкой, такой как IndexError.

Вот два примера возникновения ошибки ValueError:

|

>>> a, b, c = [1, 2] Traceback (most recent call last): File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module> ValueError: not enough values to unpack (expected 3, got 2) >>> a, b = [1, 2, 3] Traceback (most recent call last): File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module> ValueError: too many values to unpack (expected 2) |

Строка уведомления об ошибке ValueError в данных примерах говорит нам в точности, в чем заключается проблема со значениями:

- В первом примере, мы пытаемся распаковать слишком много значений. Строка уведомления об ошибке даже говорит нам, где именно ожидается распаковка трех значений, но получаются только два.

- Во втором примере, проблема в том, что мы получаем слишком много значений, при этом получаем недостаточно значений для распаковки.

Логирование ошибок из Traceback в Python 3

Получение ошибки, и ее итоговой трассировки указывает на то, что вам нужно предпринять для решения проблемы. Обычно, отладка кода — это первый шаг, но иногда проблема заключается в неожиданном, или некорректном вводе. Хотя важно предусматривать такие ситуации, иногда есть смысл скрывать или игнорировать ошибку путем логирования traceback.

Рассмотрим жизненный пример кода, в котором нужно заглушить трассировки Python. В этом примере используется библиотека requests.

Файл urlcaller.py:

|

import sys import requests response = requests.get(sys.argv[1]) print(response.status_code, response.content) |

Этот код работает исправно. Когда вы запускаете этот скрипт, задавая ему URL в качестве аргумента командной строки, он откроет данный URL, и затем выведет HTTP статус кода и содержимое страницы (content) из response. Это работает даже в случае, если ответом является статус ошибки HTTP:

|

$ python urlcaller.py https://httpbin.org/status/200 200 b» $ python urlcaller.py https://httpbin.org/status/500 500 b» |

Однако, иногда данный URL не существует (ошибка 404 — страница не найдена), или сервер не работает. В таких случаях, этот скрипт приводит к ошибке ConnectionError и выводит трассировку:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 |

$ python urlcaller.py http://thisurlprobablydoesntexist.com ... During handling of the above exception, another exception occurred: Traceback (most recent call last): File «urlcaller.py», line 5, in <module> response = requests.get(sys.argv[1]) File «/path/to/requests/api.py», line 75, in get return request(‘get’, url, params=params, **kwargs) File «/path/to/requests/api.py», line 60, in request return session.request(method=method, url=url, **kwargs) File «/path/to/requests/sessions.py», line 533, in request resp = self.send(prep, **send_kwargs) File «/path/to/requests/sessions.py», line 646, in send r = adapter.send(request, **kwargs) File «/path/to/requests/adapters.py», line 516, in send raise ConnectionError(e, request=request) requests.exceptions.ConnectionError: HTTPConnectionPool(host=‘thisurlprobablydoesntexist.com’, port=80): Max retries exceeded with url: / (Caused by NewConnectionError(‘<urllib3.connection.HTTPConnection object at 0x7faf9d671860>: Failed to establish a new connection: [Errno -2] Name or service not known’,)) |

Трассировка Python в данном случае может быть очень длинной, и включать в себя множество других ошибок, которые в итоге приводят к ошибке ConnectionError. Если вы перейдете к трассировке последних ошибок, вы заметите, что все проблемы в коде начались на пятой строке файла urlcaller.py.

Если вы обернёте неправильную строку в блоке try и except, вы сможете найти нужную ошибку, которая позволит вашему скрипту работать с большим числом вводов:

Файл urlcaller.py:

|

try: response = requests.get(sys.argv[1]) except requests.exceptions.ConnectionError: print(—1, ‘Connection Error’) else: print(response.status_code, response.content) |

Код выше использует предложение else с блоком except.

Теперь, когда вы запускаете скрипт на URL, который приводит к ошибке ConnectionError, вы получите -1 в статусе кода и содержимое ошибки подключения:

|

$ python urlcaller.py http://thisurlprobablydoesntexist.com —1 Connection Error |

Это работает отлично. Однако, в более реалистичных системах, вам не захочется просто игнорировать ошибку и итоговую трассировку, вам скорее понадобиться внести в журнал. Ведение журнала трассировок позволит вам лучше понять, что идет не так в ваших программах.

Обратите внимание: Для более лучшего представления о системе логирования в Python вы можете ознакомиться с данным руководством тут: Логирование в Python

Вы можете вести журнал трассировки в скрипте, импортировав пакет logging, получить logger, вызвать .exception() для этого логгера в куске except блока try и except. Конечный скрипт будет выглядеть примерно так:

|

# urlcaller.py import logging import sys import requests logger = logging.getLogger(__name__) try: response = requests.get(sys.argv[1]) except requests.exceptions.ConnectionError as e: logger.exception() print(—1, ‘Connection Error’) else: print(response.status_code, response.content) |

Теперь, когда вы запускаете скрипт с проблемным URL, он будет выводить исключенные -1 и ConnectionError, но также будет вести журнал трассировки:

|

$ python urlcaller.py http://thisurlprobablydoesntexist.com ... File «/path/to/requests/adapters.py», line 516, in send raise ConnectionError(e, request=request) requests.exceptions.ConnectionError: HTTPConnectionPool(host=‘thisurlprobablydoesntexist.com’, port=80): Max retries exceeded with url: / (Caused by NewConnectionError(‘<urllib3.connection.HTTPConnection object at 0x7faf9d671860>: Failed to establish a new connection: [Errno -2] Name or service not known’,)) —1 Connection Error |

По умолчанию, Python будет выводить ошибки в стандартный stderr. Выглядит так, будто мы совсем не подавили вывод трассировки. Однако, если вы выполните еще один вызов при перенаправлении stderr, вы увидите, что система ведения журналов работает, и мы можем изучать логи программы без необходимости личного присутствия во время появления ошибок:

|

$ python urlcaller.py http://thisurlprobablydoesntexist.com 2> my—logs.log —1 Connection Error |

Подведем итоги данного обучающего материала

Трассировка Python содержит замечательную информацию, которая может помочь вам понять, что идет не так с вашим кодом Python. Эти трассировки могут выглядеть немного запутанно, но как только вы поймете что к чему, и увидите, что они в себе несут, они могут быть предельно полезными. Изучив несколько трассировок, строку за строкой, вы получите лучшее представление о предоставляемой информации.

Понимание содержимого трассировки Python, когда вы запускаете ваш код может быть ключом к улучшению вашего кода. Это способ, которым Python пытается вам помочь.

Теперь, когда вы знаете как читать трассировку Python, вы можете выиграть от изучения ряда инструментов и техник для диагностики проблемы, о которой вам сообщает трассировка. Модуль traceback может быть полезным, если вам нужно узнать больше из выдачи трассировки.

- Текст является переводом статьи: Understanding the Python Traceback

- Изображение из шапки статьи принадлежит сайту © Real Python

Являюсь администратором нескольких порталов по обучению языков программирования Python, Golang и Kotlin. В составе небольшой команды единомышленников, мы занимаемся популяризацией языков программирования на русскоязычную аудиторию. Большая часть статей была адаптирована нами на русский язык и распространяется бесплатно.

E-mail: vasile.buldumac@ati.utm.md

Образование

Universitatea Tehnică a Moldovei (utm.md)

- 2014 — 2018 Технический Университет Молдовы, ИТ-Инженер. Тема дипломной работы «Автоматизация покупки и продажи криптовалюты используя технический анализ»

- 2018 — 2020 Технический Университет Молдовы, Магистр, Магистерская диссертация «Идентификация человека в киберпространстве по фотографии лица»

Traceback is the message or information or a general report along with some data, provided by Python that helps us know about an error that has occurred in our program. It’s also called raising an exception in technical terms. For any development work, error handling is one of the crucial parts when a program is being written. So, the first step in handling errors is knowing the most frequent errors we will be facing in our code.

Tracebacks provide us with a good amount of information and some messages regarding the error that occurred while running the program. Thus, it’s very important to get a general understanding of the most common errors.

Also read: Tricks for Easier Debugging in Python

Tracebacks are often referred to with certain other names like stack trace, backtrace, or stack traceback. A stack is an abstract concept in all programming languages, which just refers to a place in the system’s memory or the processor’s core where the instructions are being executed one by one. And whenever there is an error while going through the code, tracebacks try to tell us the location as well as the kind of errors it has encountered while executing those instructions.

Some of the most common Tracebacks in Python

Here’s a list of the most common tracebacks that we encounter in Python. We will also try to understand the general meaning of these errors as we move further in this article.

- SyntaxError

- NameError

- IndexError

- TypeError

- AttributeError

- KeyError

- ValueError

- ModuleNotFound and ImportError

General overview of a Traceback in Python

Before going through the most common types of tracebacks, let’s try to get an overview of the structure of a general stack trace.

# defining a function

def multiply(num1, num2):

result = num1 * num2

print(results)

# calling the function

multiply(10, 2)

Output:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "d:Pythontraceback.py", line 6, in <module>

multiply(10, 2)

File "d:Pythontraceback.py", line 3, in multiply

print(results)

NameError: name 'results' is not defined. Did you mean: 'result'?

Explanation:

Python is trying to help us out by giving us all the information about an error that has occurred while executing the program. The last line of the output says that it’s supposedly a NameError and even suggesting us a solution. Python is also trying to tell us the line number that might be the source of the error.

We can see that we have a variable name mismatch in our code. Instead of using “result”, as we earlier declared in our code, we have written “results”, which throws an error while executing the program.

So, this is the general structural hierarchy for a Traceback in Python which also implies that Python tracebacks should be read from bottom to top, which is not the case in most other programming languages.

1. SyntaxError

All programming languages have their specific syntax. If we miss out on that syntax, the program will throw an error. The code has to be parsed first only then it will give us the desired output. Thus, we have to make sure of the correct syntax for it to run correctly.

Let’s try to see the SyntaxError exception raised by Python.

# defining a function

def multiply(num1, num2):

result = num1 * num2

print "result"

# calling the function

multiply(10, 2)

Output:

File "d:Pythontraceback.py", line 4

print "result"

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

SyntaxError: Missing parentheses in call to 'print'. Did you mean print(...)?

Explanation:

When we try to run the above code, we see a SyntaxError exception being raised by Python. To print output in Python3.x, we need to wrap it around with a parenthesis. We can see the location of our error too, with the “^” symbol displayed below our error.

2. NameError

While writing any program, we declare variables, functions, and classes and also import modules into it. While making use of these in our program, we need to make sure that the declared things should be referenced correctly. On the contrary, if we make some kind of mistake, Python will throw an error and raise an exception.

Let’s see an example of NameError in Python.

# defining a function

def multiply(num1, num2):

result = num1 * num2

print(result)

# calling the function

multipli(10, 2)

Output:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "d:Pythontraceback.py", line 8, in <module>

multipli(10, 2)

NameError: name 'multipli' is not defined. Did you mean: 'multiply'?

Explanation:

Our traceback says that the name “multipli” is not defined and it’s a NameError. We have not defined the variable “multipli”, hence the error occurred.

3. IndexError

Working with indexes is a very common pattern in Python. We have to iterate over various data structures in Python to perform operations on them. Index signifies the sequence of a data structure such as a list or a tuple. Whenever we try to retrieve some kind of index data from a series or sequence which is not present in our data structure, Python throws an error saying that there is an IndexError in our code.

Let’s see an example of it.

# declaring a list my_list = ["apple", "orange", "banana", "mango"] # Getting the element at the index 5 from our list print(my_list[5])

Output:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "d:Pythontraceback.py", line 5, in <module>

print(my_list[5])

IndexError: list index out of range

Explanation:

Our traceback says that we have an IndexError at line 5. It’s evident from our stack trace that our list does not contain any element at index 5, and thus it is out of range.

4. TypeError

Python throws a TypeError when trying to perform an operation or use a function with the wrong type of objects being used together in that operation.

Let’s see an example.

# declaring variables first_num = 10 second_num = "15" # Printing the sum my_sum = first_num + second_num print(my_sum)

Output:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "d:Pythontraceback.py", line 6, in <module>

my_sum = first_num + second_num

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str'

Explanation:

In our code, we are trying to calculate the sum of two numbers. But Python is raising an exception saying that there is a TypeError for the operand “+” at line number 6. The stack trace is telling us that the addition of an integer and a string is invalid since their types do not match.

5. AttributeError

Whenever we try to access an attribute on an object which is not available on that particular object, Python throws an Attribute Error.

Let’s go through an example.

# declaring a tuple my_tuple = (1, 2, 3, 4) # Trying to append an element to our tuple my_tuple.append(5) # Print the result print(my_tuple)

Output:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "d:Pythontraceback.py", line 5, in <module>

my_tuple.append(5)

AttributeError: 'tuple' object has no attribute 'append'

Explanation:

Python says that there is an AttributeError for the object “tuple” at line 5. Since tuples are immutable data structures and we are trying to use the method “append” on it. Thus, there is an exception raised by Python here. Tuple objects do not have an attribute “append” as we are trying to mutate the same which is not allowed in Python.

6. KeyError

Dictionary is another data structure in Python. We use it all the time in our programs. It is composed of Key: Value pairs and we need to access those keys and values whenever required. But what happens if we try to search for a key in our dictionary which is not present?

Let’s try using a key that is not present and see what Python has to say about that.

# dictionary

my_dict = {"name": "John", "age": 54, "job": "Programmer"}

# Trying to access info from our dictionary object

get_info = my_dict["email"]

# Print the result

print(get_info)

Output:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "d:Pythontraceback.py", line 5, in <module>

get_info = my_dict["email"]

KeyError: 'email'

Explanation:

In the above example, we are trying to access the value for the key “email”. Well, Python searched for the key “email” in our dictionary object and raised an exception with a stack trace. The traceback says, there is a KeyError in our program at line 5. The provided key is nowhere to be found in the specified object, hence the error.

7. ValueError

The ValueError exception is raised by Python, whenever there is an incorrect value in a specified data type. The data type of the provided argument may be correct, but if it’s not an appropriate value, Python will throw an error for it.

Let’s see an example.

import math

# Variable declaration

my_num = -16

# Check the data type

print(f"The data type is: {type(my_num)}") # The data type is: <class 'int'>

# Trying to get the square root of our number

my_sqrt = math.sqrt(my_num)

# Print the result

print(my_sqrt)

Output:

The data type is: <class 'int'>

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "d:Pythontraceback.py", line 10, in <module>

my_sqrt = math.sqrt(my_num)

ValueError: math domain error

Explanation:

In the example above, we are trying to get the square root of a number using the in-built math module in Python. We are using the correct data type “int” as an argument to our function, but Python is throwing a traceback with ValueError as an exception.

This is because we can’t get a square root for a negative number, hence, it’s an incorrect value for our argument and Python tells us about the error saying that it’s a ValueError at line 10.

8. ImportError and ModuleNotFoundError

ImportError exception is raised by Python when there is an error in importing a specific module that does not exist. ModuleNotFound comes up as an exception when there is an issue with the specified path for the module which is either invalid or incorrect.

Let’s try to see these errors in action.

ImportError Example:

# Import statement from math import addition

Output:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "d:Pythontraceback.py", line 2, in <module>

from math import addition

ImportError: cannot import name 'addition' from 'math' (unknown location)

ModuleNotFoundError Example:

Output:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "d:Pythontraceback.py", line 1, in <module>

import addition

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'addition'

Explanation:

ModuleNotFoundError is a subclass of ImportError since both of them output similar kinds of errors and can be avoided using try and except blocks in Python.

Summary

In this article, we went through the most common types of errors or tracebacks that we encounter while writing Python code. Making mistakes or introducing a bug in any program that we write is very common for all levels of developers. Python being a very popular, user-friendly, and easy-to-use language has some great built-in tools to help us as much as it can while we develop something. Traceback is a great example of one of those tools and a fundamental concept to understand while learning Python.

Reference

traceback Documentation

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Getting the Most Out of a Python Traceback

Python prints a traceback when an exception is raised in your code. The traceback output can be a bit overwhelming if you’re seeing it for the first time or you don’t know what it’s telling you. But the Python traceback has a wealth of information that can help you diagnose and fix the reason for the exception being raised in your code. Understanding what information a Python traceback provides is vital to becoming a better Python programmer.

By the end of this tutorial, you’ll be able to:

- Make sense of the next traceback you see

- Recognize some of the more common tracebacks

- Log a traceback successfully while still handling the exception

What Is a Python Traceback?

A traceback is a report containing the function calls made in your code at a specific point. Tracebacks are known by many names, including stack trace, stack traceback, backtrace, and maybe others. In Python, the term used is traceback.

When your program results in an exception, Python will print the current traceback to help you know what went wrong. Below is an example to illustrate this situation:

# example.py

def greet(someone):

print('Hello, ' + someon)

greet('Chad')

Here, greet() gets called with the parameter someone. However, in greet(), that variable name is not used. Instead, it has been misspelled as someon in the print() call.

When you run this program, you’ll get the following traceback:

$ python example.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/path/to/example.py", line 4, in <module>

greet('Chad')

File "/path/to/example.py", line 2, in greet

print('Hello, ' + someon)

NameError: name 'someon' is not defined

This traceback output has all of the information you’ll need to diagnose the issue. The final line of the traceback output tells you what type of exception was raised along with some relevant information about that exception. The previous lines of the traceback point out the code that resulted in the exception being raised.

In the above traceback, the exception was a NameError, which means that there is a reference to some name (variable, function, class) that hasn’t been defined. In this case, the name referenced is someon.

The final line in this case has enough information to help you fix the problem. Searching the code for the name someon, which is a misspelling, will point you in the right direction. Often, however, your code is a lot more complicated.

How Do You Read a Python Traceback?

The Python traceback contains a lot of helpful information when you’re trying to determine the reason for an exception being raised in your code. In this section, you’ll walk through different tracebacks in order to understand the different bits of information contained in a traceback.

Python Traceback Overview

There are several sections to every Python traceback that are important. The diagram below highlights the various parts:

In Python, it’s best to read the traceback from the bottom up:

-

Blue box: The last line of the traceback is the error message line. It contains the exception name that was raised.

-

Green box: After the exception name is the error message. This message usually contains helpful information for understanding the reason for the exception being raised.

-

Yellow box: Further up the traceback are the various function calls moving from bottom to top, most recent to least recent. These calls are represented by two-line entries for each call. The first line of each call contains information like the file name, line number, and module name, all specifying where the code can be found.

-

Red underline: The second line for these calls contains the actual code that was executed.

There are a few differences between traceback output when you’re executing your code in the command-line and running code in the REPL. Below is the same code from the previous section executed in a REPL and the resulting traceback output:

>>>

>>> def greet(someone):

... print('Hello, ' + someon)

...

>>> greet('Chad')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "<stdin>", line 2, in greet

NameError: name 'someon' is not defined

Notice that in place of file names, you get "<stdin>". This makes sense since you typed the code in through standard input. Also, the executed lines of code are not displayed in the traceback.

Specific Traceback Walkthrough

Going through some specific traceback output will help you better understand and see what information the traceback will give you.

The code below is used in the examples following to illustrate the information a Python traceback gives you:

# greetings.py

def who_to_greet(person):

return person if person else input('Greet who? ')

def greet(someone, greeting='Hello'):

print(greeting + ', ' + who_to_greet(someone))

def greet_many(people):

for person in people:

try:

greet(person)

except Exception:

print('hi, ' + person)

Here, who_to_greet() takes a value, person, and either returns it or prompts for a value to return instead.

Then, greet() takes a name to be greeted, someone, and an optional greeting value and calls print(). who_to_greet() is also called with the someone value passed in.

Finally, greet_many() will iterate over the list of people and call greet(). If there is an exception raised by calling greet(), then a simple backup greeting is printed.

This code doesn’t have any bugs that would result in an exception being raised as long as the right input is provided.

If you add a call to greet() to the bottom of greetings.py and specify a keyword argument that it isn’t expecting (for example greet('Chad', greting='Yo')), then you’ll get the following traceback:

$ python example.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/path/to/greetings.py", line 19, in <module>

greet('Chad', greting='Yo')

TypeError: greet() got an unexpected keyword argument 'greting'

Once again, with a Python traceback, it’s best to work backward, moving up the output. Starting at the final line of the traceback, you can see that the exception was a TypeError. The messages that follow the exception type, everything after the colon, give you some great information. It tells you that greet() was called with a keyword argument that it didn’t expect. The unknown argument name is also given to you: greting.

Moving up, you can see the line that resulted in the exception. In this case, it’s the greet() call that we added to the bottom of greetings.py.

The next line up gives you the path to the file where the code exists, the line number of that file where the code can be found, and which module it’s in. In this case, because our code isn’t using any other Python modules, we just see <module> here, meaning that this is the file that is being executed.

With a different file and different input, you can see the traceback really pointing you in the right direction to find the issue. If you are following along, remove the buggy greet() call from the bottom of greetings.py and add the following file to your directory:

# example.py

from greetings import greet

greet(1)

Here you’ve set up another Python file that is importing your previous module, greetings.py, and using greet() from it. Here’s what happens if you now run example.py:

$ python example.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/path/to/example.py", line 3, in <module>

greet(1)

File "/path/to/greetings.py", line 5, in greet

print(greeting + ', ' + who_to_greet(someone))

TypeError: must be str, not int

The exception raised in this case is a TypeError again, but this time the message is a little less helpful. It tells you that somewhere in the code it was expecting to work with a string, but an integer was given.

Moving up, you see the line of code that was executed. Then the file and line number of the code. This time, however, instead of <module>, we get the name of the function that was being executed, greet().

Moving up to the next executed line of code, we see our problematic greet() call passing in an integer.

Sometimes after an exception is raised, another bit of code catches that exception and also results in an exception. In these situations, Python will output all exception tracebacks in the order in which they were received, once again ending in the most recently raise exception’s traceback.

Since this can be a little confusing, here’s an example. Add a call to greet_many() to the bottom of greetings.py:

# greetings.py

...

greet_many(['Chad', 'Dan', 1])

This should result in printing greetings to all three people. However, if you run this code, you’ll see an example of the multiple tracebacks being output:

$ python greetings.py

Hello, Chad

Hello, Dan

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "greetings.py", line 10, in greet_many

greet(person)

File "greetings.py", line 5, in greet

print(greeting + ', ' + who_to_greet(someone))

TypeError: must be str, not int

During handling of the above exception, another exception occurred:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "greetings.py", line 14, in <module>

greet_many(['Chad', 'Dan', 1])

File "greetings.py", line 12, in greet_many

print('hi, ' + person)

TypeError: must be str, not int

Notice the highlighted line starting with During handling in the output above. In between all tracebacks, you’ll see this line. Its message is very clear, while your code was trying to handle the previous exception, another exception was raised.

You have seen the previous exception before, when you called greet() with an integer. Since we added a 1 to the list of people to greet, we can expect the same result. However, the function greet_many() wraps the greet() call in a try and except block. Just in case greet() results in an exception being raised, greet_many() wants to print a default greeting.

The relevant portion of greetings.py is repeated here:

def greet_many(people):

for person in people:

try:

greet(person)

except Exception:

print('hi, ' + person)

So when greet() results in the TypeError because of the bad integer input, greet_many() handles that exception and attempts to print a simple greeting. Here the code ends up resulting in another, similar, exception. It’s still attempting to add a string and an integer.

Seeing all of the traceback output can help you see what might be the real cause of an exception. Sometimes when you see the final exception raised, and its resulting traceback, you still can’t see what’s wrong. In those cases, moving up to the previous exceptions usually gives you a better idea of the root cause.

What Are Some Common Tracebacks in Python?

Knowing how to read a Python traceback when your program raises an exception can be very helpful when you’re programming, but knowing some of the more common tracebacks can also speed up your process.

Here are some common exceptions you might come across, the reasons they get raised and what they mean, and the information you can find in their tracebacks.

AttributeError

The AttributeError is raised when you try to access an attribute on an object that doesn’t have that attribute defined. The Python documentation defines when this exception is raised:

Raised when an attribute reference or assignment fails. (Source)

Here’s an example of the AttributeError being raised:

>>>

>>> an_int = 1

>>> an_int.an_attribute

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

AttributeError: 'int' object has no attribute 'an_attribute'

The error message line for an AttributeError tells you that the specific object type, int in this case, doesn’t have the attribute accessed, an_attribute in this case. Seeing the AttributeError in the error message line can help you quickly identify which attribute you attempted to access and where to go to fix it.

Most of the time, getting this exception indicates that you are probably working with an object that isn’t the type you were expecting:

>>>

>>> a_list = (1, 2)

>>> a_list.append(3)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

AttributeError: 'tuple' object has no attribute 'append'

In the example above, you might be expecting a_list to be of type list, which has a method called .append(). When you receive the AttributeError exception and see that it was raised when you are trying to call .append(), that tells you that you probably aren’t dealing with the type of object you were expecting.

Often, this happens when you are expecting an object to be returned from a function or method call to be of a specific type, and you end up with an object of type None. In this case, the error message line will read, AttributeError: 'NoneType' object has no attribute 'append'.

ImportError

The ImportError is raised when something goes wrong with an import statement. You’ll get this exception, or its subclass ModuleNotFoundError, if the module you are trying to import can’t be found or if you try to import something from a module that doesn’t exist in the module. The Python documentation defines when this exception is raised:

Raised when the import statement has troubles trying to load a module. Also raised when the ‘from list’ in

from ... importhas a name that cannot be found. (Source)

Here’s an example of the ImportError and ModuleNotFoundError being raised:

>>>

>>> import asdf

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'asdf'

>>> from collections import asdf

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ImportError: cannot import name 'asdf'

In the example above, you can see that attempting to import a module that doesn’t exist, asdf, results in the ModuleNotFoundError. When attempting to import something that doesn’t exist, asdf, from a module that does exists, collections, this results in an ImportError. The error message lines at the bottom of the tracebacks tell you which thing couldn’t be imported, asdf in both cases.

IndexError

The IndexError is raised when you attempt to retrieve an index from a sequence, like a list or a tuple, and the index isn’t found in the sequence. The Python documentation defines when this exception is raised:

Raised when a sequence subscript is out of range. (Source)

Here’s an example that raises the IndexError:

>>>

>>> a_list = ['a', 'b']

>>> a_list[3]

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

IndexError: list index out of range

The error message line for an IndexError doesn’t give you great information. You can see that you have a sequence reference that is out of range and what the type of the sequence is, a list in this case. That information, combined with the rest of the traceback, is usually enough to help you quickly identify how to fix the issue.

KeyError

Similar to the IndexError, the KeyError is raised when you attempt to access a key that isn’t in the mapping, usually a dict. Think of this as the IndexError but for dictionaries. The Python documentation defines when this exception is raised:

Raised when a mapping (dictionary) key is not found in the set of existing keys. (Source)

Here’s an example of the KeyError being raised:

>>>

>>> a_dict['b']

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

KeyError: 'b'

The error message line for a KeyError gives you the key that could not be found. This isn’t much to go on but, combined with the rest of the traceback, is usually enough to fix the issue.

For an in-depth look at KeyError, take a look at Python KeyError Exceptions and How to Handle Them.

NameError

The NameError is raised when you have referenced a variable, module, class, function, or some other name that hasn’t been defined in your code. The Python documentation defines when this exception is raised:

Raised when a local or global name is not found. (Source)

In the code below, greet() takes a parameter person. But in the function itself, that parameter has been misspelled to persn:

>>>

>>> def greet(person):

... print(f'Hello, {persn}')

>>> greet('World')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "<stdin>", line 2, in greet

NameError: name 'persn' is not defined

The error message line of the NameError traceback gives you the name that is missing. In the example above, it’s a misspelled variable or parameter to the function that was passed in.

A NameError will also be raised if it’s the parameter that you misspelled:

>>>

>>> def greet(persn):

... print(f'Hello, {person}')

>>> greet('World')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "<stdin>", line 2, in greet

NameError: name 'person' is not defined

Here, it might seem as though you’ve done nothing wrong. The last line that was executed and referenced in the traceback looks good. If you find yourself in this situation, then the thing to do is to look through your code for where the person variable is used and defined. Here you can quickly see that the parameter name was misspelled.

SyntaxError

The SyntaxError is raised when you have incorrect Python syntax in your code. The Python documentation defines when this exception is raised:

Raised when the parser encounters a syntax error. (Source)

Below, the problem is a missing colon that should be at the end of the function definition line. In the Python REPL, this syntax error is raised right away after hitting enter:

>>>

>>> def greet(person)

File "<stdin>", line 1

def greet(person)

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

The error message line of the SyntaxError only tells you that there was a problem with the syntax of your code. Looking into the lines above gives you the line with the problem and usually a ^ (caret) pointing to the problem spot. Here, the colon is missing from the function’s def statement.

Also, with SyntaxError tracebacks, the regular first line Traceback (most recent call last): is missing. That is because the SyntaxError is raised when Python attempts to parse your code, and the lines aren’t actually being executed.

TypeError

The TypeError is raised when your code attempts to do something with an object that can’t do that thing, such as trying to add a string to an integer or calling len() on an object where its length isn’t defined. The Python documentation defines when this exception is raised:

Raised when an operation or function is applied to an object of inappropriate type. (Source)

Following are several examples of the TypeError being raised:

>>>

>>> 1 + '1'

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str'

>>> '1' + 1

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: must be str, not int

>>> len(1)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: object of type 'int' has no len()

All of the above examples of raising a TypeError results in an error message line with different messages. Each of them does a pretty good job of informing you of what is wrong.

The first two examples attempt to add strings and integers together. However, they are subtly different:

- The first is trying to add a

strto anint. - The second is trying to add an

intto astr.

The error message lines reflect these differences.

The last example attempts to call len() on an int. The error message line tells you that you can’t do that with an int.

ValueError

The ValueError is raised when the value of the object isn’t correct. You can think of this as an IndexError that is raised because the value of the index isn’t in the range of the sequence, only the ValueError is for a more generic case. The Python documentation defines when this exception is raised:

Raised when an operation or function receives an argument that has the right type but an inappropriate value, and the situation is not described by a more precise exception such as

IndexError. (Source)

Here are two examples of ValueError being raised:

>>>

>>> a, b, c = [1, 2]

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ValueError: not enough values to unpack (expected 3, got 2)

>>> a, b = [1, 2, 3]

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ValueError: too many values to unpack (expected 2)

The ValueError error message line in these examples tells you exactly what the problem is with the values:

-

In the first example, you are trying to unpack too many values. The error message line even tells you that you were expecting to unpack 3 values but got 2 values.

-

In the second example, the problem is that you are getting too many values and not enough variables to unpack them into.

How Do You Log a Traceback?

Getting an exception and its resulting Python traceback means you need to decide what to do about it. Usually fixing your code is the first step, but sometimes the problem is with unexpected or incorrect input. While it’s good to provide for those situations in your code, sometimes it also makes sense to silence or hide the exception by logging the traceback and doing something else.

Here’s a more real-world example of code that needs to silence some Python tracebacks. This example uses the requests library. You can find out more about it in Python’s Requests Library (Guide):

# urlcaller.py

import sys

import requests

response = requests.get(sys.argv[1])

print(response.status_code, response.content)

This code works well. When you run this script, giving it a URL as a command-line argument, it will call the URL and then print the HTTP status code and the content from the response. It even works if the response was an HTTP error status:

$ python urlcaller.py https://httpbin.org/status/200

200 b''

$ python urlcaller.py https://httpbin.org/status/500

500 b''

However, sometimes the URL your script is given to retrieve doesn’t exist, or the host server is down. In those cases, this script will now raise an uncaught ConnectionError exception and print a traceback:

$ python urlcaller.py http://thisurlprobablydoesntexist.com

...

During handling of the above exception, another exception occurred:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "urlcaller.py", line 5, in <module>

response = requests.get(sys.argv[1])

File "/path/to/requests/api.py", line 75, in get

return request('get', url, params=params, **kwargs)

File "/path/to/requests/api.py", line 60, in request

return session.request(method=method, url=url, **kwargs)

File "/path/to/requests/sessions.py", line 533, in request

resp = self.send(prep, **send_kwargs)

File "/path/to/requests/sessions.py", line 646, in send

r = adapter.send(request, **kwargs)

File "/path/to/requests/adapters.py", line 516, in send

raise ConnectionError(e, request=request)

requests.exceptions.ConnectionError: HTTPConnectionPool(host='thisurlprobablydoesntexist.com', port=80): Max retries exceeded with url: / (Caused by NewConnectionError('<urllib3.connection.HTTPConnection object at 0x7faf9d671860>: Failed to establish a new connection: [Errno -2] Name or service not known',))

The Python traceback here can be very long with many other exceptions being raised and finally resulting in the ConnectionError being raised by requests itself. If you move up the final exceptions traceback, you can see that the problem all started in our code with line 5 of urlcaller.py.

If you wrap the offending line in a try and except block, catching the appropriate exception will allow your script to continue to work with more inputs:

# urlcaller.py

...

try:

response = requests.get(sys.argv[1])

except requests.exceptions.ConnectionError:

print(-1, 'Connection Error')

else:

print(response.status_code, response.content)

The code above uses an else clause with the try and except block. If you’re unfamiliar with this feature of Python, then check out the section on the else clause in Python Exceptions: An Introduction.

Now when you run the script with a URL that will result in a ConnectionError being raised, you’ll get printed a -1 for the status code, and the content Connection Error:

$ python urlcaller.py http://thisurlprobablydoesntexist.com

-1 Connection Error

This works great. However, in most real systems, you don’t want to just silence the exception and resulting traceback, but you want to log the traceback. Logging tracebacks allows you to have a better understanding of what goes wrong in your programs.

You can log the traceback in the script by importing the logging package, getting a logger, and calling .exception() on that logger in the except portion of the try and except block. Your final script should look something like the following code:

# urlcaller.py

import logging

import sys

import requests

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

try:

response = requests.get(sys.argv[1])

except requests.exceptions.ConnectionError as e:

logger.exception()

print(-1, 'Connection Error')

else:

print(response.status_code, response.content)

Now when you run the script for a problematic URL, it will print the expected -1 and Connection Error, but it will also log the traceback:

$ python urlcaller.py http://thisurlprobablydoesntexist.com

...

File "/path/to/requests/adapters.py", line 516, in send

raise ConnectionError(e, request=request)

requests.exceptions.ConnectionError: HTTPConnectionPool(host='thisurlprobablydoesntexist.com', port=80): Max retries exceeded with url: / (Caused by NewConnectionError('<urllib3.connection.HTTPConnection object at 0x7faf9d671860>: Failed to establish a new connection: [Errno -2] Name or service not known',))

-1 Connection Error

By default, Python will send log messages to standard error (stderr). This looks like we haven’t suppressed the traceback output at all. However, if you call it again while redirecting the stderr, you can see that the logging system is working, and we can save our logs off for later:

$ python urlcaller.py http://thisurlprobablydoesntexist.com 2> my-logs.log

-1 Connection Error

Conclusion

The Python traceback contains great information that can help you find what is going wrong in your Python code. These tracebacks can look a little intimidating, but once you break it down to see what it’s trying to show you, they can be super helpful. Going through a few tracebacks line by line will give you a better understanding of the information they contain and help you get the most out of them.

Getting a Python traceback output when you run your code is an opportunity to improve your code. It’s one way Python tries to help you out.

Now that you know how to read a Python traceback, you can benefit from learning more about some tools and techniques for diagnosing the problems that your traceback output is telling you about. Python’s built-in traceback module can be used to work with and inspect tracebacks. The traceback module can be helpful when you need to get more out of the traceback output. It would also be helpful to learn more about some techniques for debugging your Python code and ways to debug in IDLE.

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Getting the Most Out of a Python Traceback

Prerequisite: Python Traceback

To print stack trace for an exception the suspicious code will be kept in the try block and except block will be employed to handle the exception generated. Here we will be printing the stack trace to handle the exception generated. The printing stack trace for an exception helps in understanding the error and what went wrong with the code. Not just this, the stack trace also shows where the error occurred.

The general structure of a stack trace for an exception:

- Traceback for the most recent call.

- Location of the program.

- Line in the program where the error was encountered.

- Name of the error: relevant information about the exception.

Example:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "C:/Python27/hdg.py", line 5, in

value=A[5]

IndexError: list index out of range

Method 1: By using print_exc() method.

This method prints exception information and stack trace entries from traceback object tb to file.

Syntax: traceback.print_exc(limit=None, file=None, chain=True)

Parameters: This method accepts the following parameters:

- if a limit argument is positive, Print up to limit stack trace entries from traceback object tb (starting from the caller’s frame). Otherwise, print the last abs(limit) entries. If the limit argument is None, all entries are printed.

- If the file argument is None, the output goes to sys.stderr; otherwise, it should be an open file or file-like object to receive the output.

- If chain argument is true (the default), then chained exceptions will be printed as well, like the interpreter itself does when printing an unhandled exception.

Return: None.

Code:

Python3

import traceback

A = [1, 2, 3, 4]

try:

value = A[5]

except:

traceback.print_exc()

print("end of program")

Output:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "C:/Python27/hdg.py", line 8, in

value=A[5]

IndexError: list index out of range

end of program

Method 2: By using print_exception() method.

This method prints exception information and stack trace entries from traceback object tb to file.

Syntax : traceback.print_exception(etype, value, tb, limit=None, file=None, chain=True)

Parameters: This method accepts the following parameters:

- if tb argument is not None, it prints a header Traceback (most recent call last):

- it prints the exception etype and value after the stack trace

- if type(value) argument is SyntaxError and value has the appropriate format, it prints the line where the syntax error occurred with a caret indicating the approximate position of the error.

- if a limit argument is positive, Print up to limit stack trace entries from traceback object tb (starting from the caller’s frame). Otherwise, print the last abs(limit) entries. If the limit argument is None, all entries are printed.

- If the file argument is None, the output goes to sys.stderr; otherwise, it should be an open file or file-like object to receive the output.

- If chain argument is true (the default), then chained exceptions will be printed as well, like the interpreter itself does when printing an unhandled exception.

Return: None.

Code:

Python3

import traceback

import sys

a = 4

b = 0

try:

value = a / b

except:

traceback.print_exception(*sys.exc_info())

print("end of program")

Output:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "C:/Python27/hdg.py", line 10, in

value=a/b

ZeroDivisionError: integer division or modulo by zero

end of program

The traceback of error generated by python interpreter can be sometimes long and not that useful. We might need to modify stack traces according to our need in some situations where we need more control over the amount of traceback getting printed. We might even need more control over the format of the trace getting printed. Python provides a module named traceback which has a list of method which let us extract error traces, format it and print it according to our need. This can help with formatting and limiting error trace getting generated. As a part of this tutorial, we’ll be explaining how we can use a different method of traceback module for different purposes. We’ll explain the usage of the method with simple examples.

There is three kinds of methods available with the traceback module.

- print_*() — These methods are used to print stack traces to the desired output medium (standard error, standard output, file, etc).

- print_tb()

- print_exception()

- print_exc()

- print_list()

- print_last()

- print_stack()

- extract_*() — These methods are used to extract stack traces from an exception and return preprocessed stack trace entries.

- extract_tb()

- extract_stack()

- format_*() — These methods are used to format output generated by

extract_*methods. These methods can be useful if we want to print an error stack on some GUI.- format_tb()

- format_list()

- format_exception_only()

- format_exception()

- format_exc()

- format_stack()

- walk_*() — These methods returns generator instance which lets us iterate through trace frames and print stack trace according to our need.

- walk_stack()

- walk_tb()

We’ll now explain the usage of these methods with simple examples one by one.

Example 1¶

As a part of our first example, we’ll explain how we can print the stack trace of error using print_tb() method.

- print_tb(tb, limit=None, file=None) — This method accepts traceback instance and prints traces to the output. It let us limit the amount of trace getting printed by specifying limit parameter. We can give integer value to limit parameter and it’ll print trace for that many frames only. If we don’t specify a limit then by default it’ll be None and will print the whole stack trace. It has another important parameter named file which lets us specify where we want to direct output of trace to. We can give a file-like object and it’ll direct traces to it. We can also specify standard error and standard output using sys.err and sys.out as file parameters and trace will be directed to them. If we don’t specify the file parameter then by default it’ll direct trace to standard error.

Below we have artificially tried to generate an error by giving randint() method of random module negative integer numbers. We have the first printed traceback generated by the python interpreter. Then we have caught exceptions using try-except block. We have then retrieved traceback from the error object using traceback attribute of the error object and have given it to print_tb() method which prints a stack trace.

Please make a note that print_tb() only prints stack trace and does not print actual exception type.

import random out = random.randint(-5,-10)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- ValueError Traceback (most recent call last) <ipython-input-1-a38bfad2efe7> in <module> 1 import random 2 ----> 3 out = random.randint(-5,-10) ~/anaconda3/lib/python3.7/random.py in randint(self, a, b) 220 """ 221 --> 222 return self.randrange(a, b+1) 223 224 def _randbelow(self, n, int=int, maxsize=1<<BPF, type=type, ~/anaconda3/lib/python3.7/random.py in randrange(self, start, stop, step, _int) 198 return istart + self._randbelow(width) 199 if step == 1: --> 200 raise ValueError("empty range for randrange() (%d,%d, %d)" % (istart, istop, width)) 201 202 # Non-unit step argument supplied. ValueError: empty range for randrange() (-5,-9, -4)

import traceback import random try: out = random.randint(-5,-10) except Exception as e: traceback.print_tb(e.__traceback__)