Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Raising and Handling Python Exceptions

A Python program terminates as soon as it encounters an error. In Python, an error can be a syntax error or an exception. In this article, you will see what an exception is and how it differs from a syntax error. After that, you will learn about raising exceptions and making assertions. Then, you’ll finish with a demonstration of the try and except block.

Exceptions versus Syntax Errors

Syntax errors occur when the parser detects an incorrect statement. Observe the following example:

>>> print( 0 / 0 ))

File "<stdin>", line 1

print( 0 / 0 ))

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

The arrow indicates where the parser ran into the syntax error. In this example, there was one bracket too many. Remove it and run your code again:

>>> print( 0 / 0)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ZeroDivisionError: integer division or modulo by zero

This time, you ran into an exception error. This type of error occurs whenever syntactically correct Python code results in an error. The last line of the message indicated what type of exception error you ran into.

Instead of showing the message exception error, Python details what type of exception error was encountered. In this case, it was a ZeroDivisionError. Python comes with various built-in exceptions as well as the possibility to create self-defined exceptions.

Raising an Exception

We can use raise to throw an exception if a condition occurs. The statement can be complemented with a custom exception.

If you want to throw an error when a certain condition occurs using raise, you could go about it like this:

x = 10

if x > 5:

raise Exception('x should not exceed 5. The value of x was: {}'.format(x))

When you run this code, the output will be the following:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<input>", line 4, in <module>

Exception: x should not exceed 5. The value of x was: 10

The program comes to a halt and displays our exception to screen, offering clues about what went wrong.

The AssertionError Exception

Instead of waiting for a program to crash midway, you can also start by making an assertion in Python. We assert that a certain condition is met. If this condition turns out to be True, then that is excellent! The program can continue. If the condition turns out to be False, you can have the program throw an AssertionError exception.

Have a look at the following example, where it is asserted that the code will be executed on a Linux system:

import sys

assert ('linux' in sys.platform), "This code runs on Linux only."

If you run this code on a Linux machine, the assertion passes. If you were to run this code on a Windows machine, the outcome of the assertion would be False and the result would be the following:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<input>", line 2, in <module>

AssertionError: This code runs on Linux only.

In this example, throwing an AssertionError exception is the last thing that the program will do. The program will come to halt and will not continue. What if that is not what you want?

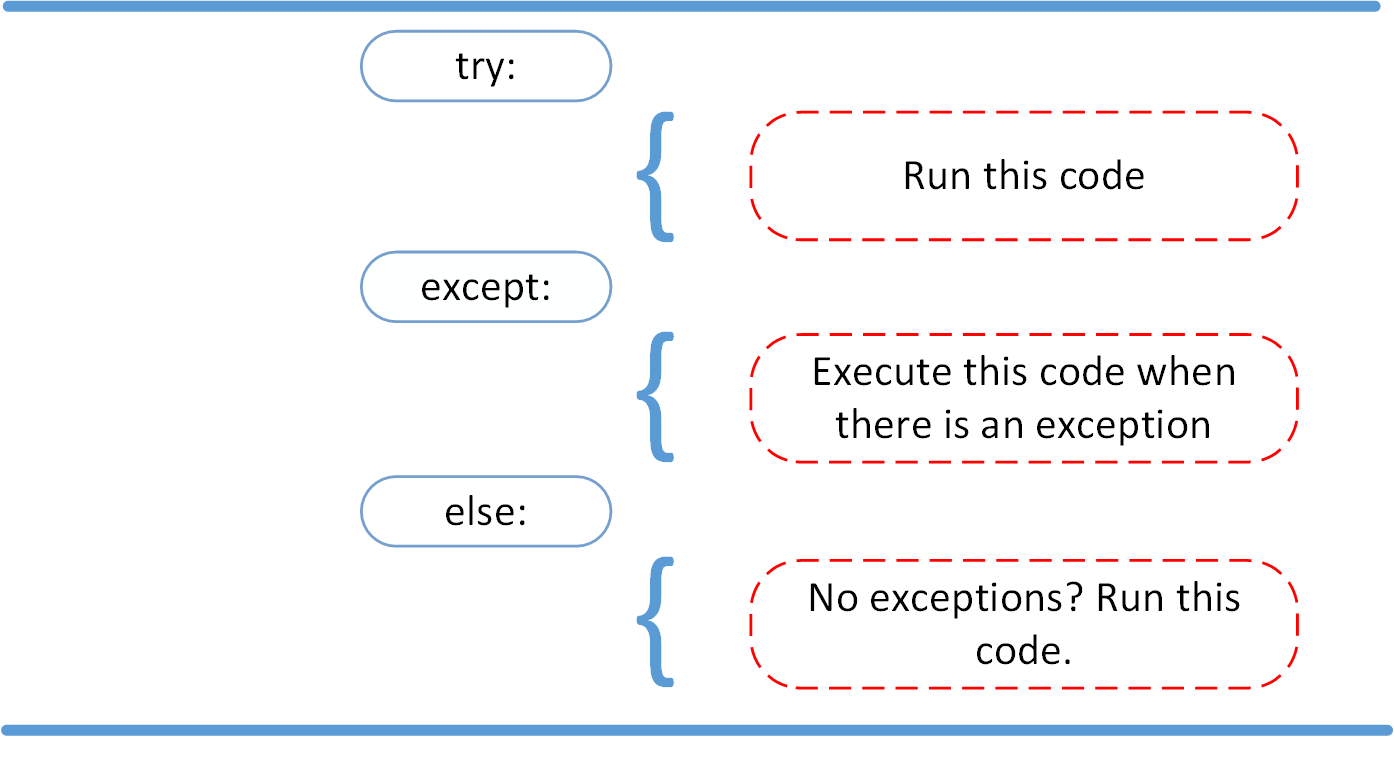

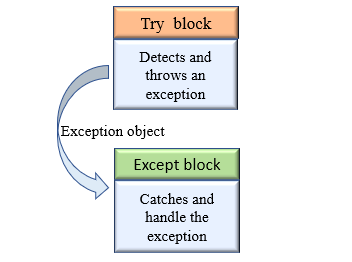

The try and except Block: Handling Exceptions

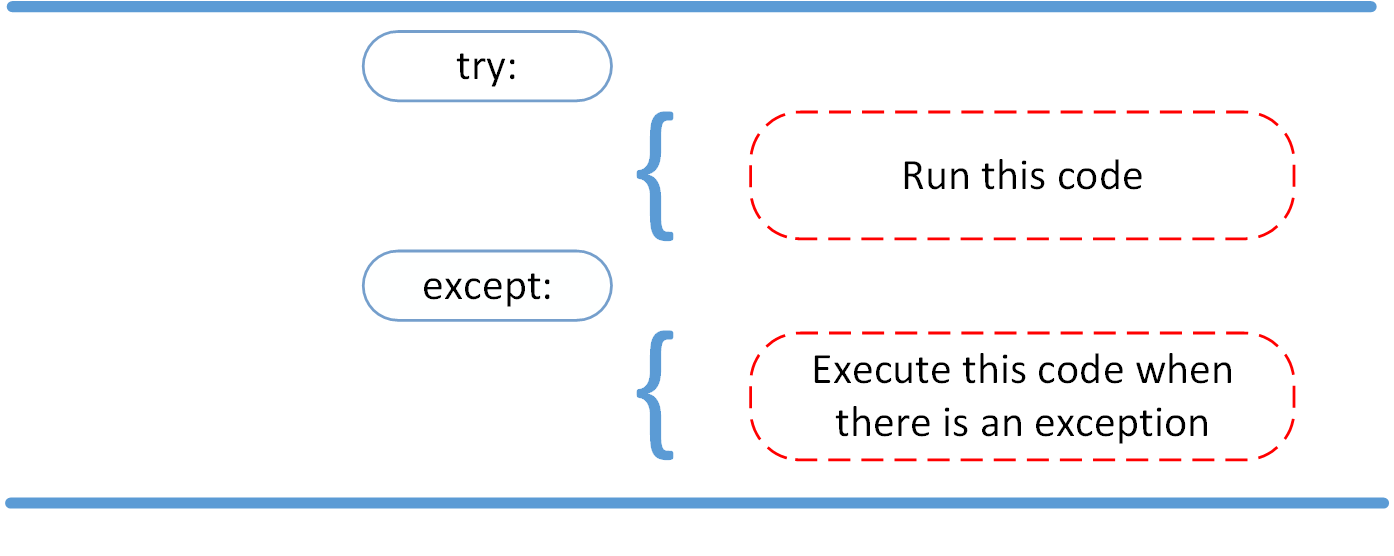

The try and except block in Python is used to catch and handle exceptions. Python executes code following the try statement as a “normal” part of the program. The code that follows the except statement is the program’s response to any exceptions in the preceding try clause.

As you saw earlier, when syntactically correct code runs into an error, Python will throw an exception error. This exception error will crash the program if it is unhandled. The except clause determines how your program responds to exceptions.

The following function can help you understand the try and except block:

def linux_interaction():

assert ('linux' in sys.platform), "Function can only run on Linux systems."

print('Doing something.')

The linux_interaction() can only run on a Linux system. The assert in this function will throw an AssertionError exception if you call it on an operating system other then Linux.

You can give the function a try using the following code:

try:

linux_interaction()

except:

pass

The way you handled the error here is by handing out a pass. If you were to run this code on a Windows machine, you would get the following output:

You got nothing. The good thing here is that the program did not crash. But it would be nice to see if some type of exception occurred whenever you ran your code. To this end, you can change the pass into something that would generate an informative message, like so:

try:

linux_interaction()

except:

print('Linux function was not executed')

Execute this code on a Windows machine:

Linux function was not executed

When an exception occurs in a program running this function, the program will continue as well as inform you about the fact that the function call was not successful.

What you did not get to see was the type of error that was thrown as a result of the function call. In order to see exactly what went wrong, you would need to catch the error that the function threw.

The following code is an example where you capture the AssertionError and output that message to screen:

try:

linux_interaction()

except AssertionError as error:

print(error)

print('The linux_interaction() function was not executed')

Running this function on a Windows machine outputs the following:

Function can only run on Linux systems.

The linux_interaction() function was not executed

The first message is the AssertionError, informing you that the function can only be executed on a Linux machine. The second message tells you which function was not executed.

In the previous example, you called a function that you wrote yourself. When you executed the function, you caught the AssertionError exception and printed it to screen.

Here’s another example where you open a file and use a built-in exception:

try:

with open('file.log') as file:

read_data = file.read()

except:

print('Could not open file.log')

If file.log does not exist, this block of code will output the following:

This is an informative message, and our program will still continue to run. In the Python docs, you can see that there are a lot of built-in exceptions that you can use here. One exception described on that page is the following:

Exception

FileNotFoundErrorRaised when a file or directory is requested but doesn’t exist. Corresponds to errno ENOENT.

To catch this type of exception and print it to screen, you could use the following code:

try:

with open('file.log') as file:

read_data = file.read()

except FileNotFoundError as fnf_error:

print(fnf_error)

In this case, if file.log does not exist, the output will be the following:

[Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'file.log'

You can have more than one function call in your try clause and anticipate catching various exceptions. A thing to note here is that the code in the try clause will stop as soon as an exception is encountered.

Look at the following code. Here, you first call the linux_interaction() function and then try to open a file:

try:

linux_interaction()

with open('file.log') as file:

read_data = file.read()

except FileNotFoundError as fnf_error:

print(fnf_error)

except AssertionError as error:

print(error)

print('Linux linux_interaction() function was not executed')

If the file does not exist, running this code on a Windows machine will output the following:

Function can only run on Linux systems.

Linux linux_interaction() function was not executed

Inside the try clause, you ran into an exception immediately and did not get to the part where you attempt to open file.log. Now look at what happens when you run the code on a Linux machine:

[Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'file.log'

Here are the key takeaways:

- A

tryclause is executed up until the point where the first exception is encountered. - Inside the

exceptclause, or the exception handler, you determine how the program responds to the exception. - You can anticipate multiple exceptions and differentiate how the program should respond to them.

- Avoid using bare

exceptclauses.

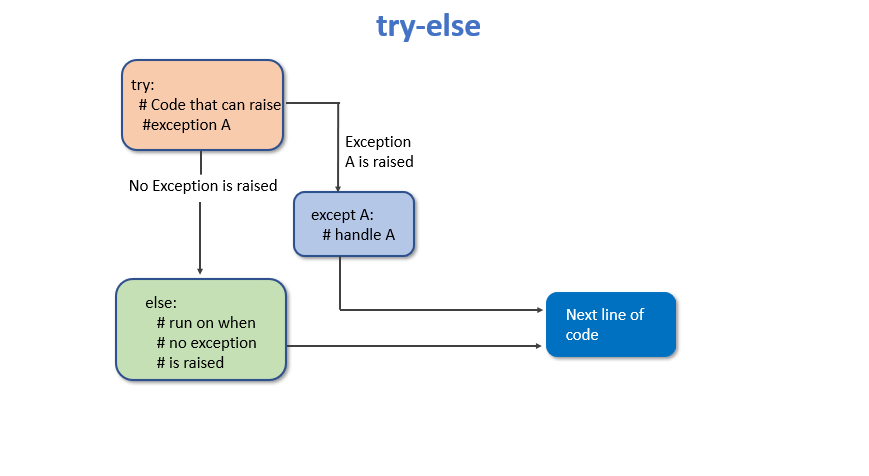

The else Clause

In Python, using the else statement, you can instruct a program to execute a certain block of code only in the absence of exceptions.

Look at the following example:

try:

linux_interaction()

except AssertionError as error:

print(error)

else:

print('Executing the else clause.')

If you were to run this code on a Linux system, the output would be the following:

Doing something.

Executing the else clause.

Because the program did not run into any exceptions, the else clause was executed.

You can also try to run code inside the else clause and catch possible exceptions there as well:

try:

linux_interaction()

except AssertionError as error:

print(error)

else:

try:

with open('file.log') as file:

read_data = file.read()

except FileNotFoundError as fnf_error:

print(fnf_error)

If you were to execute this code on a Linux machine, you would get the following result:

Doing something.

[Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'file.log'

From the output, you can see that the linux_interaction() function ran. Because no exceptions were encountered, an attempt to open file.log was made. That file did not exist, and instead of opening the file, you caught the FileNotFoundError exception.

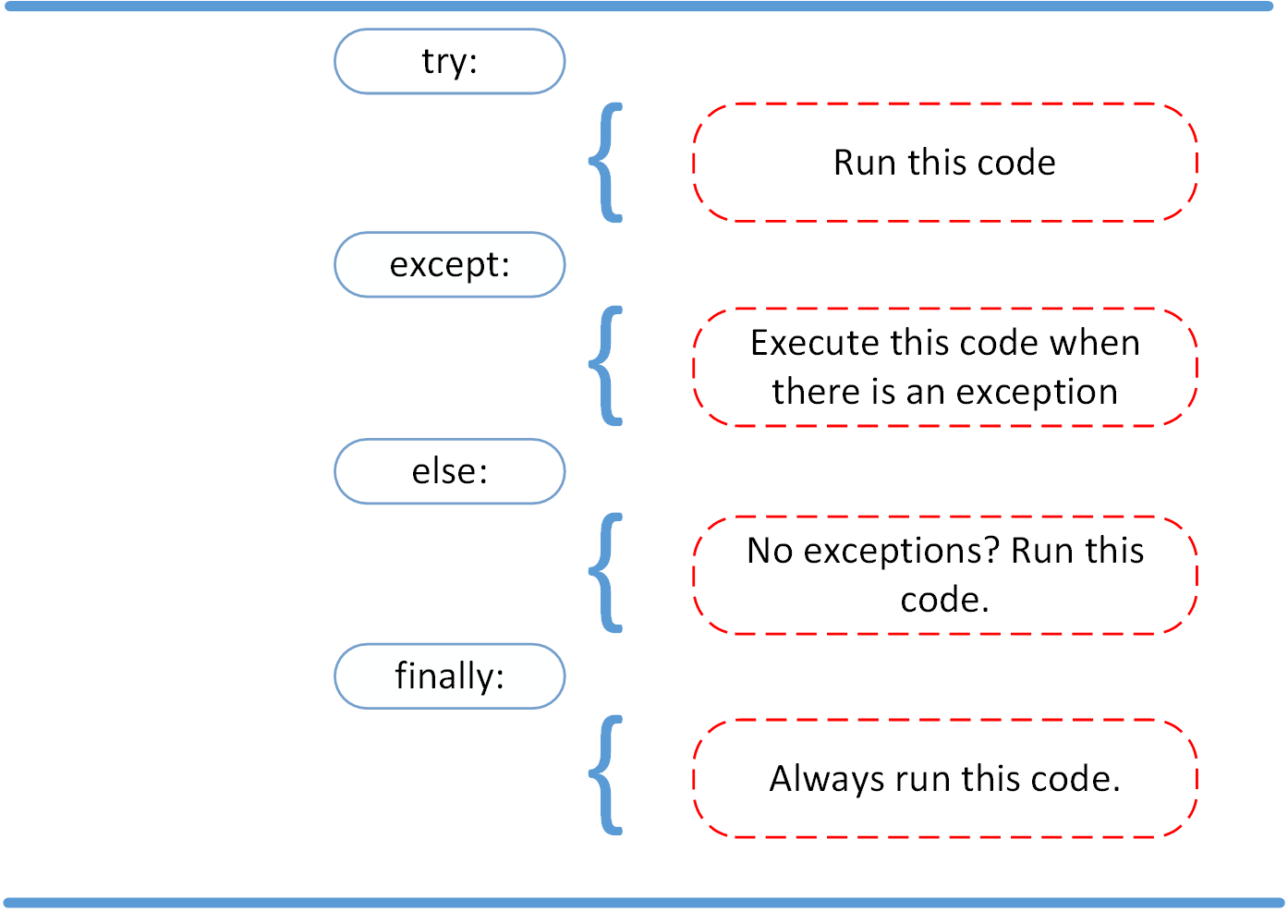

Cleaning Up After Using finally

Imagine that you always had to implement some sort of action to clean up after executing your code. Python enables you to do so using the finally clause.

Have a look at the following example:

try:

linux_interaction()

except AssertionError as error:

print(error)

else:

try:

with open('file.log') as file:

read_data = file.read()

except FileNotFoundError as fnf_error:

print(fnf_error)

finally:

print('Cleaning up, irrespective of any exceptions.')

In the previous code, everything in the finally clause will be executed. It does not matter if you encounter an exception somewhere in the try or else clauses. Running the previous code on a Windows machine would output the following:

Function can only run on Linux systems.

Cleaning up, irrespective of any exceptions.

Summing Up

After seeing the difference between syntax errors and exceptions, you learned about various ways to raise, catch, and handle exceptions in Python. In this article, you saw the following options:

raiseallows you to throw an exception at any time.assertenables you to verify if a certain condition is met and throw an exception if it isn’t.- In the

tryclause, all statements are executed until an exception is encountered. exceptis used to catch and handle the exception(s) that are encountered in the try clause.elselets you code sections that should run only when no exceptions are encountered in the try clause.finallyenables you to execute sections of code that should always run, with or without any previously encountered exceptions.

Hopefully, this article helped you understand the basic tools that Python has to offer when dealing with exceptions.

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Raising and Handling Python Exceptions

Привет, Хабр!

Ваш интерес к новой книге «Секреты Python Pro» убедил нас, что рассказ о необычностях Python заслуживает продолжения. Сегодня предлагаем почитать небольшой туториал о создании кастомных (в тексте — собственных) классах исключений. У автора получилось интересно, сложно не согласиться с ним в том, что важнейшим достоинством исключения является полнота и ясность выдаваемого сообщения об ошибке. Часть кода из оригинала — в виде картинок.

Добро пожаловать под кат.

Создание собственных классов ошибок

В Python предусмотрена возможность создавать собственные классы исключений. Создавая такие классы, можно разнообразить дизайн классов в приложении. Собственный класс ошибок мог бы логировать ошибки, инспектировать объект. Это мы определяем, что делает класс исключений, хотя, обычно собственный класс едва ли сможет больше, чем просто отобразить сообщение.

Естественно, важен и сам тип ошибки, и мы часто создаем собственные типы ошибок, чтобы обозначить конкретную ситуацию, которая обычно не покрывается на уровне языка Python. Таким образом, пользователи класса, встретив такую ошибку, будут в точности знать, что происходит.

Эта статья состоит из двух частей. Сначала мы определим класс исключений сам по себе. Затем продемонстрируем, как можно интегрировать собственные классы исключений в наши программы на Python и покажем, как таким образом повысить удобство работы с теми классами, что мы проектируем.

Собственный класс исключений MyCustomError

При выдаче исключения требуются методы __init__() и __str__().

При выдаче исключения мы уже создаем экземпляр исключения и в то же время выводим его на экран. Давайте детально разберем наш собственный класс исключений, показанный ниже.

В вышеприведенном классе MyCustomError есть два волшебных метода, __init__ и __str__, автоматически вызываемых в процессе обработки исключений. Метод Init вызывается при создании экземпляра, а метод str – при выводе экземпляра на экран. Следовательно, при выдаче исключения два этих метода обычно вызываются сразу друг за другом. Оператор вызова исключения в Python переводит программу в состояние ошибки.

В списке аргументов метода __init__ есть *args. Компонент *args – это особый режим сопоставления с шаблоном, используемый в функциях и методах. Он позволяет передавать множественные аргументы, а переданные аргументы хранит в виде кортежа, но при этом позволяет вообще не передавать аргументов.

В нашем случае можно сказать, что, если конструктору MyCustomError были переданы какие-либо аргументы, то мы берем первый переданный аргумент и присваиваем его атрибуту message в объекте. Если ни одного аргумента передано не было, то атрибуту message будет присвоено значение None.

В первом примере исключение MyCustomError вызывается без каких-либо аргументов, поэтому атрибуту message этого объекта присваивается значение None. Будет вызван метод str, который выведет на экран сообщение ‘MyCustomError message has been raised’.

Исключение MyCustomError выдается без каких-либо аргументов (скобки пусты). Иными словами, такая конструкция объекта выглядит нестандартно. Но это просто синтаксическая поддержка, оказываемая в Python при выдаче исключения.

Во втором примере MyCustomError передается со строковым аргументом ‘We have a problem’. Он устанавливается в качестве атрибута message у объекта и выводится на экран в виде сообщения об ошибке, когда выдается исключение.

Код для класса исключения MyCustomError находится здесь.

class MyCustomError(Exception):

def __init__(self, *args):

if args:

self.message = args[0]

else:

self.message = None

def __str__(self):

print('calling str')

if self.message:

return 'MyCustomError, {0} '.format(self.message)

else:

return 'MyCustomError has been raised'

# выдача MyCustomError

raise MyCustomError('We have a problem')Класс CustomIntFloatDic

Создаем собственный словарь, в качестве значений которого могут использоваться только целые числа и числа с плавающей точкой.

Пойдем дальше и продемонстрируем, как с легкостью и пользой внедрять классы ошибок в наши собственные программы. Для начала предложу слегка надуманный пример. В этом вымышленном примере я создам собственный словарь, который может принимать в качестве значений только целые числа или числа с плавающей точкой.

Если пользователь попытается задать в качестве значения в этом словаре любой другой тип данных, то будет выдано исключение. Это исключение сообщит пользователю полезную информацию о том, как следует использовать данный словарь. В нашем случае это сообщение прямо информирует пользователя, что в качестве значений в данном словаре могут задаваться только целые числа или числа с плавающей точкой.

Создавая собственный словарь, нужно учитывать, что в нем есть два места, где в словарь могут добавляться значения. Во-первых, это может происходить в методе init при создании объекта (на данном этапе объекту уже могут быть присвоены ключи и значения), а во-вторых — при установке ключей и значений прямо в словаре. В обоих этих местах требуется написать код, гарантирующий, что значение может относиться только к типу int или float.

Для начала определю класс CustomIntFloatDict, наследующий от встроенного класса dict. dict передается в списке аргументов, которые заключены в скобки и следуют за именем класса CustomIntFloatDict.

Если создан экземпляр класса CustomIntFloatDict, причем, параметрам ключа и значения не передано никаких аргументов, то они будут установлены в None. Выражение if интерпретируется так: если или ключ равен None, или значение равно None, то с объектом будет вызван метод get_dict(), который вернет атрибут empty_dict; такой атрибут у объекта указывает на пустой список. Помните, что атрибуты класса доступны у всех экземпляров класса.

Назначение этого класса — позволить пользователю передать список или кортеж с ключами и значениями внутри. Если пользователь вводит список или кортеж в поисках ключей и значений, то два эти перебираемых множества будут сцеплены при помощи функции zip языка Python. Подцепленная переменная, указывающая на объект zip, поддается перебору, а кортежи поддаются распаковке. Перебирая кортежи, я проверяю, является ли val экземпляром класса int или float. Если val не относится ни к одному из этих классов, я выдаю собственное исключение IntFloatValueError и передаю ему val в качестве аргумента.

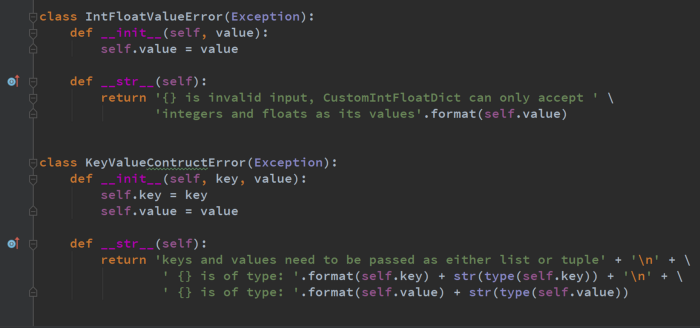

Класс исключений IntFloatValueError

При выдаче исключения IntFloatValueError мы создаем экземпляр класса IntFloatValueError и одновременно выводим его на экран. Это означает, что будут вызваны волшебные методы init и str.

Значение, спровоцировавшее выдаваемое исключение, устанавливается в качестве атрибута value, сопровождающего класс IntFloatValueError. При вызове волшебного метода str пользователь получает сообщение об ошибке, информирующее, что значение init в CustomIntFloatDict является невалидным. Пользователь знает, что делать для исправления этой ошибки.

Классы исключений IntFloatValueError и KeyValueConstructError

Если ни одно исключение не выдано, то есть, все val из сцепленного объекта относятся к типам int или float, то они будут установлены при помощи __setitem__(), и за нас все сделает метод из родительского класса dict, как показано ниже.

Класс KeyValueConstructError

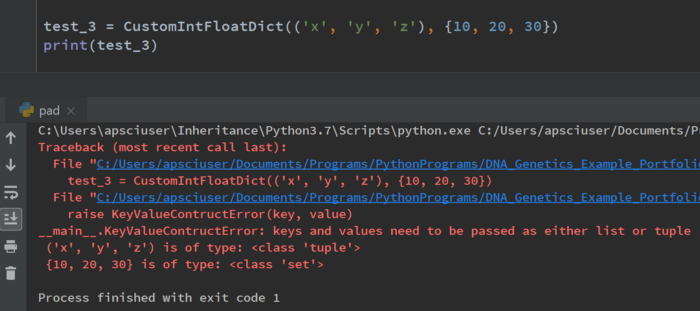

Что произойдет, если пользователь введет тип, не являющийся списком или кортежем с ключами и значениями?

Опять же, этот пример немного искусственный, но с его помощью удобно показать, как можно использовать собственные классы исключений.

Если пользователь не укажет ключи и значения как список или кортеж, то будет выдано исключение KeyValueConstructError. Цель этого исключения – проинформировать пользователя, что для записи ключей и значений в объект CustomIntFloatDict, список или кортеж должен быть указан в конструкторе init класса CustomIntFloatDict.

В вышеприведенном примере, в качестве второго аргумента конструктору init было передано множество, и из-за этого было выдано исключение KeyValueConstructError. Польза выведенного сообщения об ошибке в том, что отображаемое сообщение об ошибке информирует пользователя: вносимые ключи и значения должны сообщаться в качестве либо списка, либо кортежа.

Опять же, когда выдано исключение, создается экземпляр KeyValueConstructError, и при этом ключ и значения передаются в качестве аргументов конструктору KeyValueConstructError. Они устанавливаются в качестве значений атрибутов key и value у KeyValueConstructError и используются в методе __str__ для генерации информативного сообщения об ошибке при выводе сообщения на экран.

Далее я даже включаю типы данных, присущие объектам, добавленным к конструктору init – делаю это для большей ясности.

Установка ключа и значения в CustomIntFloatDict

CustomIntFloatDict наследует от dict. Это означает, что он будет функционировать в точности как словарь, везде за исключением тех мест, которые мы выберем для точечного изменения его поведения.

__setitem__ — это волшебный метод, вызываемый при установке ключа и значения в словаре. В нашей реализации setitem мы проверяем, чтобы значение относилось к типу int или float, и только после успешной проверки оно может быть установлено в словаре. Если проверка не пройдена, то можно еще раз воспользоваться классом исключения IntFloatValueError. Здесь можно убедиться, что, попытавшись задать строку ‘bad_value’ в качестве значения в словаре test_4, мы получим исключение.

Весь код к этому руководству показан ниже и выложен на Github.

# Создаем словарь, значениями которого могут служить только числа типов int и float

class IntFloatValueError(Exception):

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

def __str__(self):

return '{} is invalid input, CustomIntFloatDict can only accept '

'integers and floats as its values'.format(self.value)

class KeyValueContructError(Exception):

def __init__(self, key, value):

self.key = key

self.value = value

def __str__(self):

return 'keys and values need to be passed as either list or tuple' + 'n' +

' {} is of type: '.format(self.key) + str(type(self.key)) + 'n' +

' {} is of type: '.format(self.value) + str(type(self.value))

class CustomIntFloatDict(dict):

empty_dict = {}

def __init__(self, key=None, value=None):

if key is None or value is None:

self.get_dict()

elif not isinstance(key, (tuple, list,)) or not isinstance(value, (tuple, list)):

raise KeyValueContructError(key, value)

else:

zipped = zip(key, value)

for k, val in zipped:

if not isinstance(val, (int, float)):

raise IntFloatValueError(val)

dict.__setitem__(self, k, val)

def get_dict(self):

return self.empty_dict

def __setitem__(self, key, value):

if not isinstance(value, (int, float)):

raise IntFloatValueError(value)

return dict.__setitem__(self, key, value)

# тестирование

# test_1 = CustomIntFloatDict()

# print(test_1)

# test_2 = CustomIntFloatDict({'a', 'b'}, [1, 2])

# print(test_2)

# test_3 = CustomIntFloatDict(('x', 'y', 'z'), (10, 'twenty', 30))

# print(test_3)

# test_4 = CustomIntFloatDict(('x', 'y', 'z'), (10, 20, 30))

# print(test_4)

# test_4['r'] = 1.3

# print(test_4)

# test_4['key'] = 'bad_value'Заключение

Если создавать собственные исключения, то работать с классом становится гораздо удобнее. В классе исключения должны быть волшебные методы init и str, автоматически вызываемые в процессе обработки исключений. Только от вас зависит, что именно будет делать ваш собственный класс исключений. Среди показанных методов – такие, что отвечают за инспектирование объекта и вывод на экран информативного сообщения об ошибке.

Как бы то ни было, классы исключений значительно упрощают обработку всех возникающих ошибок!

In the previous tutorial, we learned about different built-in exceptions in Python and why it is important to handle exceptions. .

However, sometimes we may need to create our own custom exceptions that serve our purpose.

Defining Custom Exceptions

In Python, we can define custom exceptions by creating a new class that is derived from the built-in Exception class.

Here’s the syntax to define custom exceptions,

class CustomError(Exception):

...

pass

try:

...

except CustomError:

...Here, CustomError is a user-defined error which inherits from the Exception class.

Note:

- When we are developing a large Python program, it is a good practice to place all the user-defined exceptions that our program raises in a separate file.

- Many standard modules define their exceptions separately as

exceptions.pyorerrors.py(generally but not always).

Example: Python User-Defined Exception

# define Python user-defined exceptions

class InvalidAgeException(Exception):

"Raised when the input value is less than 18"

pass

# you need to guess this number

number = 18

try:

input_num = int(input("Enter a number: "))

if input_num < number:

raise InvalidAgeException

else:

print("Eligible to Vote")

except InvalidAgeException:

print("Exception occurred: Invalid Age")Output

If the user input input_num is greater than 18,

Enter a number: 45 Eligible to Vote

If the user input input_num is smaller than 18,

Enter a number: 14 Exception occurred: Invalid Age

In the above example, we have defined the custom exception InvalidAgeException by creating a new class that is derived from the built-in Exception class.

Here, when input_num is smaller than 18, this code generates an exception.

When an exception occurs, the rest of the code inside the try block is skipped.

The except block catches the user-defined InvalidAgeException exception and statements inside the except block are executed.

Customizing Exception Classes

We can further customize this class to accept other arguments as per our needs.

To learn about customizing the Exception classes, you need to have the basic knowledge of Object-Oriented programming.

Visit Python Object Oriented Programming to learn about Object-Oriented programming in Python.

Let’s see an example,

class SalaryNotInRangeError(Exception):

"""Exception raised for errors in the input salary.

Attributes:

salary -- input salary which caused the error

message -- explanation of the error

"""

def __init__(self, salary, message="Salary is not in (5000, 15000) range"):

self.salary = salary

self.message = message

super().__init__(self.message)

salary = int(input("Enter salary amount: "))

if not 5000 < salary < 15000:

raise SalaryNotInRangeError(salary)Output

Enter salary amount: 2000

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<string>", line 17, in <module>

raise SalaryNotInRangeError(salary)

__main__.SalaryNotInRangeError: Salary is not in (5000, 15000) range

Here, we have overridden the constructor of the Exception class to accept our own custom arguments salary and message.

Then, the constructor of the parent Exception class is called manually with the self.message argument using super().

The custom self.salary attribute is defined to be used later.

The inherited __str__ method of the Exception class is then used to display the corresponding message when SalaryNotInRangeError is raised.

Introduction

Software applications don’t run perfectly all the time. Despite intensive debugging and multiple testing levels, applications still fail. Bad data, broken network connectivity, corrupted databases, memory pressures, and unexpected user inputs can all prevent an application from performing normally. When such an event occurs, and the app is unable to continue its normal flow, this is known as an exception. And it’s your application’s job—and your job as a coder—to catch and handle these exceptions gracefully so that your app keeps working.

Install the Python SDK to identify and fix exceptions

What Are Python Exceptions?

Exceptions in Python applications can happen for many of the reasons stated above and more; and if they aren’t handled well, these exceptions can cause the program to crash, causing data loss, or worse, corrupted data. As a Python developer, you need to think about possible exception situations and include error handling in your code.

Fortunately, Python comes with a robust error handling framework. Using structured exception handling and a set of pre-defined exceptions, Python programs can determine the error type at run time and act accordingly. These can include actions like taking an alternate path, using default values, or prompting for correct input.

This article will show you how to raise exceptions in your Python code and how to address exceptions.

Difference Between Python Syntax Errors and Python Exceptions

Before diving in, it’s important to understand the two types of unwanted conditions in Python programming—syntax error and exception.

The syntax error exception occurs when the code does not conform to Python keywords, naming style, or programming structure. The interpreter sees the invalid syntax during its parsing phase and raises a SyntaxError exception. The program stops and fails at the point where the syntax error happened. That’s why syntax errors are exceptions that can’t be handled.

Here’s an example code block with a syntax error (note the absence of a colon after the “if” condition in parentheses):

a = 10

b = 20

if (a < b)

print('a is less than b')

c = 30

print(c)The interpreter picks up the error and points out the line number. Note how it doesn’t proceed after the syntax error:

File "test.py", line 4

if (a < b)

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

Process finished with exit code 1On the other hand, an exception happens when the code has no syntax error but encounters other error situations. These conditions can be addressed within the code—either in the current function or in the calling stack. In this sense, exceptions are not fatal. A Python program can continue to run if it gracefully handles the exception.

Here is an example of a Python code that doesn’t have any syntax errors. It’s trying to run an arithmetic operation on two string variables:

a = 'foo'

b = 'bar'

print(a % b)The exception raised is TypeError:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "test.py", line 4, in

print(a % b)

TypeError: not all arguments converted during string formatting

Process finished with exit code 1Python throws the TypeError exception when there are wrong data types. Similar to TypeError, there are several built-in exceptions like:

- ModuleNotFoundError

- ImportError

- MemoryError

- OSError

- SystemError

- … And so on

You can refer to the Python documentation for a full list of exceptions.

How to Throw an Exception in Python

Sometimes you want Python to throw a custom exception for error handling. You can do this by checking a condition and raising the exception, if the condition is True. The raised exception typically warns the user or the calling application.

You use the “raise” keyword to throw a Python exception manually. You can also add a message to describe the exception

Here is a simple example: Say you want the user to enter a date. The date has to be either today or in the future. If the user enters a past date, the program should raise an exception:

Python Throw Exception Example

from datetime import datetime

current_date = datetime.now()

print("Current date is: " + current_date.strftime('%Y-%m-%d'))

dateinput = input("Enter date in yyyy-mm-dd format: ")

# We are not checking for the date input format here

date_provided = datetime.strptime(dateinput, '%Y-%m-%d')

print("Date provided is: " + date_provided.strftime('%Y-%m-%d'))

if date_provided.date() < current_date.date():

raise Exception("Date provided can't be in the past")To test the code, we enter a date older than the current date. The “if” condition evaluates to true and raises the exception:

Current date is: 2021-01-24

Enter date in yyyy-mm-dd format: 2021-01-22

Date provided is: 2021-01-22

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "test.py", line 13, in

raise Exception("Date provided can't be in the past")

Exception: Date provided can't be in the past

Process finished with exit code 1Instead of raising a generic exception, we can specify a type for it, too:

if (date_provided.date() < current_date.date()):

raise ValueError("Date provided can't be in the past")With a similar input as before, Python will now throw this exception:

raise ValueError("Date provided can't be in the past")

ValueError: Date provided can't be in the pastUsing AssertionError in Python Exception Throwing

Another way to raise an exception is to use assertion. With assertion, you assert a condition to be true before running a statement. If the condition evaluates to true, the statement runs, and the control continues to the next statement. However, if the condition evaluates to false, the program throws an AssertionError. The diagram below shows the logical flow:

Using AssertionError, we can rewrite the code snippet in the last section like this:

from datetime import datetime

current_date = datetime.now()

print("Current date is: " + current_date.strftime('%Y-%m-%d'))

dateinput = input("Enter date in yyyy-mm-dd format: ")

# We are not checking for the date input format here

date_provided = datetime.strptime(dateinput, '%Y-%m-%d')

print("Date provided is: " + date_provided.strftime('%Y-%m-%d'))

assert(date_provided.date() >= current_date.date()), "Date provided can't be in the past"Note how we removed the “if” condition and are now asserting that the date provided is greater than or equal to the current date. When inputting an older date, the AssertionError displays:

Current date is: 2021-01-24

Enter date in yyyy-mm-dd format: 2021-01-23

Traceback (most recent call last):

Date provided is: 2021-01-23

File "test.py", line 12, in

assert(date_provided.date() >= current_date.date()), "Date provided can't be in the past"

AssertionError: Date provided can't be in the past

Process finished with exit code 1Catching Python Exceptions with Try-Except

Now that you understand how to throw exceptions in Python manually, it’s time to see how to handle those exceptions. Most modern programming languages use a construct called “try-catch” for exception handling. With Python, its basic form is “try-except”. The try-except block looks like this:

Python Try Catch Exception Example

...

try:

<--program code-->

except:

<--exception handling code-->

<--program code-->

...Here, the program flow enters the “try” block. If there is an exception, the control jumps to the code in the “except” block. The error handling code you put in the “except” block depends on the type of error you think the code in the “try” block may encounter.

Here’s an example of Python’s “try-except” (often mistakenly referred to as “try-catch-exception”). Let’s say we want our code to run only if the Python version is 3. Using a simple assertion in the code looks like this:

import sys

assert (sys.version_info[0] == 3), "Python version must be 3"If the of Python version is not 3, the error message looks like this:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "test.py", line 2, in

assert (sys.version_info[0] == 3), "Python version must be 3"

AssertionError: Python version must be 3

Process finished with exit code 1Instead of letting the program fail with an unhandled exception and showing an ugly error message, we could use a try-except block for a graceful exit.

import sys

try:

assert (sys.version_info[0] == 3), "Python version must be 3"

except Exception as e:

print(e)

rollbar.report_exc_info()Now, the error message is much cleaner:

Python version must be 3

The “except” keyword in the construct also accepts the type of error you want to handle. To illustrate this, let’s go back to our date script from the last section. In that script, we assumed the user will enter a date in “YYYY-MM-DD” format. However, as a developer, you should cater to any type of erroneous data instead of depending on the user. For example, some exception scenarios can be:

- No date entered (blank)

- Text entered

- Number entered

- Time entered

- Special characters entered

- Different date format entered (such as “dd/mm/yyyy”)

To address all these conditions, we can rewrite the code block as shown below. This will catch any ValueError exception raised when meeting any of the above conditions:

from datetime import datetime

current_date = datetime.now()

print("Current date is: " + current_date.strftime('%Y-%m-%d'))

dateinput = input("Enter date in yyyy-mm-dd format: ")

try:

date_provided = datetime.strptime(dateinput, '%Y-%m-%d')

except ValueError as e:

print(e)

rollbar.report_exc_info()

exit()

print("Date provided is: " + date_provided.strftime('%Y-%m-%d'))

assert(date_provided.date() >= current_date.date()), "Date provided can't be in the past"In this case, the program will exit gracefully if the date isn’t correctly formatted.

You can include multiple “except” blocks for the “try” block to trap different types of exceptions. Each “except” block will address a specific type of error:

...

try:

<--program code-->

except <--Exception Type 1-->:

<--exception handling code-->

except <--Exception Type 2-->:

<--exception handling code-->

except <--Exception Type 3-->:

<--exception handling code-->

...Here’s a very simple example:

num0 = 10

try:

num1 = input("Enter 1st number:")

num2 = input("Enter 2nd number:")

result = (int(num1) * int(num2))/(num0 * int(num2))

except ValueError as ve:

print(ve)

rollbar.report_exc_info()

exit()

except ZeroDivisionError as zde:

print(zde)

rollbar.report_exc_info()

exit()

except TypeError as te:

print(te)

rollbar.report_exc_info()

exit()

except:

print('Unexpected Error!')

rollbar.report_exc_info()

exit()

print(result)We can test this program with different values:

Enter 1st number:1

Enter 2nd number:0

division by zero

Enter 1st number:

Enter 2nd number:6

invalid literal for int() with base 10: ''

Enter 1st number:12.99

Enter 2nd number:33

invalid literal for int() with base 10: '12.99'Catching Python Exceptions with Try-Except-Else

The next element in the Python “try-except” construct is “else”:

Python Try Except Else Example

...

try:

<--program code-->

except <--Exception Type 1-->:

<--exception handling code-->

except <--Exception Type 2-->:

<--exception handling code-->

except <--Exception Type 3-->:

<--exception handling code-->

...

else:

<--program code to run if "try" block doesn't encounter any error-->

...The “else” block runs if there are no exceptions raised from the “try” block. Looking at the code structure above, you can see the “else” in Python exception handling works almost the same as an “if-else” construct

To show how “else” works, we can slightly modify the arithmetic script’s code from the last section. If you look at the script, you will see we calculated the variable value of “result” using an arithmetic expression. Instead of putting this in the “try” block, you can move it to an “else” block. That way, the exception blocks any error raised while converting the input values to integers. And if there are no exceptions, the “else” block will perform the actual calculation:

num0 = 10

try:

num1 = int(input("Enter 1st number:"))

num2 = int(input("Enter 2nd number:"))

except ValueError as ve:

print(ve)

rollbar.report_exc_info()

exit()

except ZeroDivisionError as zde:

print(zde)

rollbar.report_exc_info()

exit()

except TypeError as te:

print(te)

rollbar.report_exc_info()

exit()

except:

print('Unexpected Error!')

rollbar.report_exc_info()

exit()

else:

result = (num1 * num2)/(num0 * num2)

print(result)

Using simple integers as input values runs the “else” block code:

Enter 1st number:2

Enter 2nd number:3

0.2And using erroneous data like empty values, decimal numbers, or strings cause the corresponding “except” block to run and skip the “else” block:

Enter 1st number:s

invalid literal for int() with base 10: 's'

Enter 1st number:20

Enter 2nd number:

invalid literal for int() with base 10: ''

Enter 1st number:5

Enter 2nd number:6.4

invalid literal for int() with base 10: '6.4'However, there’s still a possibility of unhandled exceptions when the “else” block runs:

Enter 1st number:1

Enter 2nd number:0

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "test.py", line 19, in

result = (num1 * num2)/(num0 * num2)

ZeroDivisionError: division by zeroAs you can see, both inputs are integers (1 and 0), and the “try” block successfully converts them to integers. When the “else” block runs, we see the exception.

So how do you handle errors in the “else” block? You guessed that right—you can use another “try-except-else” block within the outer “else” block:

Enter 1st number:1

Enter 2nd number:0

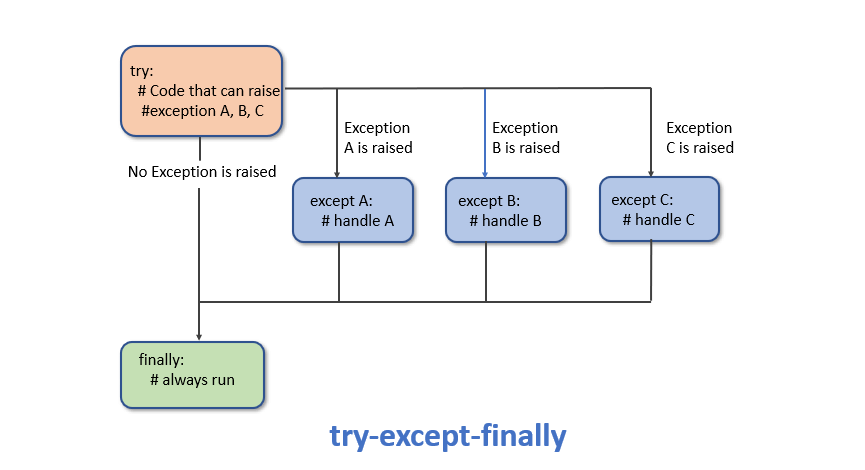

division by zeroCatching Python Exceptions with Try-Except-Else-Finally

Finally, we have the last optional block in Python error handling. And it’s literally called “finally”:

Python Try Finally Example

...

try:

<--program code-->

except <--Exception Type 1-->:

<--exception handling code-->

except <--Exception Type 2-->:

<--exception handling code-->

except <-->Exception Type 3-->>:

<--exception handling code-->

...

else:

<--program code to run if "try" block doesn't encounter any error-->

finally:

<--program code that runs regardless of errors in the "try" or "else" block-->The “finally” block runs whether or not the “try” block’s code raises an exception. If there’s an exception, the code in the corresponding “except” block will run, and then the code in the “finally” block will run. If there are no exceptions, the code in the “else” block will run (if there’s an “else” block), and then the code in the “finally” block will run.

Since the code in the “finally” block always runs, you want to keep your “clean up” codes here, such as:

- Writing status messages to log files

- Resetting counters, lists, arrays

- Closing open files

- Closing database connections

- Resetting object variables

- Disconnecting from network resources

- … And so on

Here’s an example of using “finally”:

try:

f = open("testfile.txt", 'r')

except FileNotFoundError as fne:

rollbar.report_exc_info()

print(fne)

print('Creating file...')

f = open("testfile.txt", 'w')

f.write('2')

else:

data=f.readline(1)

print(data)

finally:

print('Closing file')

f.close()Here, the “try” block tries to open a file for reading. If the file doesn’t exist, the exception block shows a warning message, creates the file, and adds a static value of “2” to it. If the file exists, the “else” block reads the first line of its content and prints that out. Finally, the “finally” block closes the file. This happens whether or not the file initially existed.

What we have discussed so far can be summarized in the flowchart below:

How Rollbar Can Help Log and Track Python Errors

Rollbar is a continuous code improvement platform for software development teams. It offers an automated way to capture Python errors and failed tests in real time from all application stack layers and across all environments. This allows creating a proactive and automated response to application errors. The diagram below shows how Rollbar works:

Rollbar natively works with a wide array of programming languages and frameworks, including Python. Python developers can install pyrollbar, Rollbar’s SDK for Python, using a tool like pip, importing the Rollbar class in the code, and sending Python exceptions to Rollbar. The code snippet below shows how easy it is:

import rollbar

rollbar.init('POST_SERVER_ITEM_ACCESS_TOKEN', 'dev')

try:

# some code

except TypeError:

rollbar.report_message('There is a data type mismatch', 'fatal')

except:

rollbar.report_exc_info()

Track, Analyze and Manage Errors With Rollbar

Managing errors and exceptions in your code is challenging. It can make deploying production code an unnerving experience. Being able to track, analyze, and manage errors in real-time can help you to proceed with more confidence. Rollbar automates error monitoring and triaging, making fixing errors easier than ever. Try it today.

Exceptions

So far we have made programs that ask the user to enter a string, and

we also know how to convert that to an integer.

text = input("Enter something: ") number = int(text) print("Your number doubled:", number*2)

That works.

Enter a number: 3

Your number doubled: 6

But that doesn’t work if the user does not enter a number.

Enter a number: lol Traceback (most recent call last): File "/some/place/file.py", line 2, in <module> number = int(text) ValueError: invalid literal for int() with base 10: 'lol'

So how can we fix that?

What are exceptions?

In the previous example we got a ValueError. ValueError is an

exception. In other words, ValueError is an error that can occur

in our program. If an exception occurs, the program will stop and we

get an error message. The interactive prompt will display an error

message and keep going.

>>> int('lol') Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> ValueError: invalid literal for int() with base 10: 'lol' >>>

Exceptions are classes.

>>> ValueError <class 'ValueError'> >>>

We can also create exceptions. We won’t get an error message by doing

that, but we’ll use this for displaying our own error messages later.

>>> the_problem = ValueError('oh no') >>> the_problem ValueError('oh no',) >>>

Catching exceptions

If we need to try to do something and see if we get an exception, we

can use try and except. This is also known as catching the

exception.

>>> try: ... print(int('lol')) ... except ValueError: ... print("Oops!") ... Oops! >>>

The except part doesn’t run if the try part succeeds.

>>> try: ... print("Hello World!") ... except ValueError: ... print("What the heck? Printing failed!") ... Hello World! >>>

ValueError is raised when something gets an invalid value, but the

value’s type is correct. In this case, int can take a string as an

argument, but the string needs to contain a number, not lol. If

the type is wrong, we will get a TypeError instead.

>>> 123 + 'hello' Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str' >>>

Exceptions always interrupt the code even if we catch them. Here the

print never runs because it’s after the error but inside the try

block. Everything after the try block runs normally.

>>> try: ... 123 + 'hello' ... print("This doesn't get printed.") ... except TypeError: ... print("Oops!") ... Oops! >>>

Does an except ValueError also catch TypeErrors?

>>> try: ... print(123 + 'hello') ... except ValueError: ... print("Oops!") ... Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 2, in <module> TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str' >>>

No, it doesn’t. But maybe we could except for both ValueError and

TypeError?

>>> try: ... int('lol') ... except ValueError: ... print('wrong value') ... except TypeError: ... print('wrong type') ... wrong value >>> try: ... 123 + 'hello' ... except ValueError: ... print('wrong value') ... except TypeError: ... print('wrong type') ... wrong type >>>

Seems to be working.

We can also also catch multiple exceptions by catching

a tuple of exceptions:

>>> try: ... 123 + 'hello' ... except (ValueError, TypeError): ... print('wrong value or type') ... wrong value or type >>> try: ... int('lol') ... except (ValueError, TypeError): ... print('wrong value or type') ... wrong value or type >>>

Catching Exception will catch all errors. We’ll learn more about why

it does that in a moment.

>>> try: ... 123 + 'hello' ... except Exception: ... print("Oops!") ... Oops! >>> try: ... int('lol') ... except Exception: ... print("Oops!") ... Oops! >>>

It’s also possible to catch an exception and store it in a variable.

Here we are catching an exception that Python created and storing it in

our_error.

>>> try: ... 123 + 'hello' ... except TypeError as e: ... our_error = e ... >>> our_error TypeError("unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str'",) >>> type(our_error) <class 'TypeError'> >>>

When should we catch exceptions?

Do not do things like this:

try: # many lines of code except Exception: print("Oops! Something went wrong.")

There’s many things that can go wrong in the try block. If something

goes wrong all we have is an oops message that doesn’t tell us which

line caused the problem. This makes fixing the program really annoying.

If we want to catch exceptions we need to be specific about what exactly

we want to catch and where instead of catching everything we can in the

whole program.

There’s nothing wrong with doing things like this:

try: with open('some file', 'r') as f: content = f.read() except OSError: # we can't read the file but we can work without it content = some_default_content

Usually catching errors that the user has caused is also a good idea:

import sys text = input("Enter a number: ") try: number = int(text) except ValueError: print(f"'{text}' is not a number.", file=sys.stderr) sys.exit(1) print(f"Your number doubled is {(number * 2)}.")

Raising exceptions

Now we know how to create exceptions and how to handle errors that

Python creates. But we can also create error messages manually. This

is known as raising an exception and throwing an exception.

Raising an exception is easy. All we need to do is to type raise

and then an exception we want to raise:

>>> raise ValueError("lol is not a number") Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> ValueError: lol is not a number >>>

Of course, we can also raise an exception from a variable.

>>> oops = ValueError("lol is not a number") >>> raise oops Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> ValueError: lol is not a number >>>

If we define a function that raises an

exception and call it we’ll notice that the error message also

says which functions we ran to get to that error.

>>> def oops(): ... raise ValueError("oh no!") ... >>> def do_the_oops(): ... oops() ... >>> do_the_oops() Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> File "<stdin>", line 2, in do_the_oops File "<stdin>", line 2, in oops ValueError: oh no! >>>

If our code was in a file we would also see the line of code

that raised the error.

When should we raise exceptions?

Back in the module chapter we learned to display error

messages by printing to sys.stderr and then calling sys.exit(1), so

when should we use that and when should we raise an exception?

Exceptions are meant for programmers, so if we are writing something

that other people will import we should use exceptions. If our program

is working like it should be and the user has done something wrong,

it’s usually better to use sys.stderr and sys.exit.

Exception hierarchy

Exceptions are organized like this. I made this tree with this

program on Python 3.7. You may

have more or less exceptions than I have if your Python is newer or

older than mine, but they should be mostly similar.

Exception

├── ArithmeticError

│ ├── FloatingPointError

│ ├── OverflowError

│ └── ZeroDivisionError

├── AssertionError

├── AttributeError

├── BufferError

├── EOFError

├── ImportError

│ └── ModuleNotFoundError

├── LookupError

│ ├── IndexError

│ └── KeyError

├── MemoryError

├── NameError

│ └── UnboundLocalError

├── OSError

│ ├── BlockingIOError

│ ├── ChildProcessError

│ ├── ConnectionError

│ │ ├── BrokenPipeError

│ │ ├── ConnectionAbortedError

│ │ ├── ConnectionRefusedError

│ │ └── ConnectionResetError

│ ├── FileExistsError

│ ├── FileNotFoundError

│ ├── InterruptedError

│ ├── IsADirectoryError

│ ├── NotADirectoryError

│ ├── PermissionError

│ ├── ProcessLookupError

│ └── TimeoutError

├── ReferenceError

├── RuntimeError

│ ├── NotImplementedError

│ └── RecursionError

├── StopAsyncIteration

├── StopIteration

├── SyntaxError

│ └── IndentationError

│ └── TabError

├── SystemError

├── TypeError

├── ValueError

│ └── UnicodeError

│ ├── UnicodeDecodeError

│ ├── UnicodeEncodeError

│ └── UnicodeTranslateError

└── Warning

├── BytesWarning

├── DeprecationWarning

├── FutureWarning

├── ImportWarning

├── PendingDeprecationWarning

├── ResourceWarning

├── RuntimeWarning

├── SyntaxWarning

├── UnicodeWarning

└── UserWarning

Catching an exception also catches everything that’s under it in this

tree. For example, catching OSError catches errors that we typically

get when processing files, and catching Exception catches

all of these errors. You don’t need to remember this tree, running

help('builtins') should display a larger tree that this is a part of.

There are also a few exceptions that are not in this tree like

SystemExit and KeyboardInterrupt, but most of the time we shouldn’t

catch them. Catching Exception doesn’t catch them either.

Summary

- Exceptions are classes and they can be used just like all other classes.

- ValueError and TypeError are some of the most commonly used exceptions.

- The

tryandexceptkeywords can be used for attempting to do

something and then doing something else if we get an error. This is

known as catching exceptions. - It’s possible to raise exceptions with the

raisekeyword. This

is also known as throwing exceptions. - Raise exceptions if they are meant to be displayed for programmers and

usesys.stderrandsys.exitotherwise.

Examples

Keep asking a number from the user until it’s entered correctly.

while True: try: number = int(input("Enter a number: ")) break except ValueError: print("That's not a valid number! Try again.") print("Your number doubled is:", number * 2)

This program allows the user to customize the message it prints by

modifying a file the greeting is stored in, and it can create the

file for the user if it doesn’t exist already. This example also uses

things from the file chapter, the function defining

chapter and the module chapter.

# These are here so you can change them to customize the program # easily. default_greeting = "Hello World!" filename = "greeting.txt" import sys def askyesno(question): while True: answer = input(question + ' (y or n) ') if answer == 'Y' or answer == 'y': return True if answer == 'N' or answer == 'n': return False def greet(): with open(filename, 'r') as f: for line in f: print(line.rstrip('n')) try: greet() except OSError: print(f"Cannot read '{filename}'!", file=sys.stderr) if askyesno("Would you like to create a default greeting file?"): with open(filename, 'w') as f: print(default_greeting, file=f) greet()

If you have trouble with this tutorial, please

tell me about it and I’ll make this tutorial better,

or ask for help online.

If you like this tutorial, please give it a

star.

You may use this tutorial freely at your own risk. See

LICENSE.

Previous | Next |

List of contents

In this article, you will learn error and exception handling in Python.

By the end of the article, you’ll know:

- How to handle exceptions using the try, except, and finally statements

- How to create a custom exception

- How to raise an exceptions

- How to use built-in exception effectively to build robust Python programs

Table of contents

- What are Exceptions?

- Why use Exception

- What are Errors?

- Syntax error

- Logical errors (Exception)

- Built-in Exceptions

- The try and except Block to Handling Exceptions

- Catching Specific Exceptions

- Handle multiple exceptions with a single except clause

- Using try with finally

- Using try with else clause

- Raising an Exceptions

- Exception Chaining

- Custom and User-defined Exceptions

- Customizing Exception Classes

- Exception Lifecycle

- Warnings

What are Exceptions?

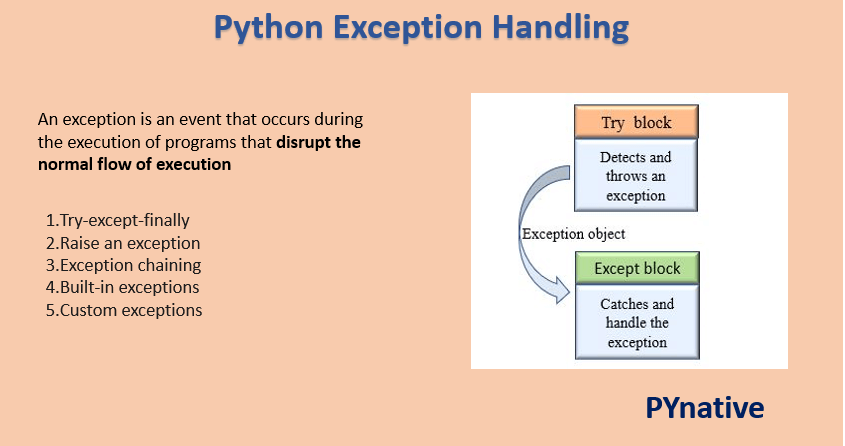

An exception is an event that occurs during the execution of programs that disrupt the normal flow of execution (e.g., KeyError Raised when a key is not found in a dictionary.) An exception is a Python object that represents an error..

In Python, an exception is an object derives from the BaseException class that contains information about an error event that occurred within a method. Exception object contains:

- Error type (exception name)

- The state of the program when the error occurred

- An error message describes the error event.

Exception are useful to indicate different types of possible failure condition.

For example, bellow are the few standard exceptions

- FileNotFoundException

- ImportError

- RuntimeError

- NameError

- TypeError

In Python, we can throw an exception in the try block and catch it in except block.

Why use Exception

- Standardized error handling: Using built-in exceptions or creating a custom exception with a more precise name and description, you can adequately define the error event, which helps you debug the error event.

- Cleaner code: Exceptions separate the error-handling code from regular code, which helps us to maintain large code easily.

- Robust application: With the help of exceptions, we can develop a solid application, which can handle error event efficiently

- Exceptions propagation: By default, the exception propagates the call stack if you don’t catch it. For example, if any error event occurred in a nested function, you do not have to explicitly catch-and-forward it; automatically, it gets forwarded to the calling function where you can handle it.

- Different error types: Either you can use built-in exception or create your custom exception and group them by their generalized parent class, or Differentiate errors by their actual class

What are Errors?

On the other hand, An error is an action that is incorrect or inaccurate. For example, syntax error. Due to which the program fails to execute.

The errors can be broadly classified into two types:

- Syntax errors

- Logical errors

Syntax error

The syntax error occurs when we are not following the proper structure or syntax of the language. A syntax error is also known as a parsing error.

When Python parses the program and finds an incorrect statement it is known as a syntax error. When the parser found a syntax error it exits with an error message without running anything.

Common Python Syntax errors:

- Incorrect indentation

- Missing colon, comma, or brackets

- Putting keywords in the wrong place.

Example

print("Welcome to PYnative")

print("Learn Python with us..")Output

print("Learn Python with us..")

^

IndentationError: unexpected indentLogical errors (Exception)

Even if a statement or expression is syntactically correct, the error that occurs at the runtime is known as a Logical error or Exception. In other words, Errors detected during execution are called exceptions.

Common Python Logical errors:

- Indenting a block to the wrong level

- using the wrong variable name

- making a mistake in a boolean expression

Example

a = 10

b = 20

print("Addition:", a + c)Output

print("Addition:", a + c)

NameError: name 'c' is not definedBuilt-in Exceptions

The below table shows different built-in exceptions.

Python automatically generates many exceptions and errors. Runtime exceptions, generally a result of programming errors, such as:

- Reading a file that is not present

- Trying to read data outside the available index of a list

- Dividing an integer value by zero

| Exception | Description |

|---|---|

AssertionError |

Raised when an assert statement fails. |

AttributeError |

Raised when attribute assignment or reference fails. |

EOFError |

Raised when the input() function hits the end-of-file condition. |

FloatingPointError |

Raised when a floating-point operation fails. |

GeneratorExit |

Raise when a generator’s close() method is called. |

ImportError |

Raised when the imported module is not found. |

IndexError |

Raised when the index of a sequence is out of range. |

KeyError |

Raised when a key is not found in a dictionary. |

KeyboardInterrupt |

Raised when the user hits the interrupt key (Ctrl+C or Delete) |

MemoryError |

Raised when an operation runs out of memory. |

NameError |

Raised when a variable is not found in the local or global scope. |

OSError |

Raised when system operation causes system related error. |

ReferenceError |

Raised when a weak reference proxy is used to access a garbage collected referent. |

Example: The FilenotfoundError is raised when a file in not present on the disk

fp = open("test.txt", "r")

if fp:

print("file is opened successfully")

Output:

FileNotFoundError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'test.txt'

The try and except Block to Handling Exceptions

When an exception occurs, Python stops the program execution and generates an exception message. It is highly recommended to handle exceptions. The doubtful code that may raise an exception is called risky code.

To handle exceptions we need to use try and except block. Define risky code that can raise an exception inside the try block and corresponding handling code inside the except block.

Syntax

try :

# statements in try block

except :

# executed when exception occured in try block

The try block is for risky code that can raise an exception and the except block to handle error raised in a try block. For example, if we divide any number by zero, try block will throw ZeroDivisionError, so we should handle that exception in the except block.

When we do not use try…except block in the program, the program terminates abnormally, or it will be nongraceful termination of the program.

Now let’s see the example when we do not use try…except block for handling exceptions.

Example:

a = 10

b = 0

c = a / b

print("a/b = %d" % c)Output

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "E:/demos/exception.py", line 3, in <module>

c = a / b

ZeroDivisionError: division by zeroWe can see in the above code when we are divided by 0; Python throws an exception as ZeroDivisionError and the program terminated abnormally.

We can handle the above exception using the try…except block. See the following code.

Example

try:

a = 10

b = 0

c = a/b

print("The answer of a divide by b:", c)

except:

print("Can't divide with zero. Provide different number")Output

Can't divide with zero. Provide different number

Catching Specific Exceptions

We can also catch a specific exception. In the above example, we did not mention any specific exception in the except block. Catch all the exceptions and handle every exception is not good programming practice.

It is good practice to specify an exact exception that the except clause should catch. For example, to catch an exception that occurs when the user enters a non-numerical value instead of a number, we can catch only the built-in ValueError exception that will handle such an event properly.

We can specify which exception except block should catch or handle. A try block can be followed by multiple numbers of except blocks to handle the different exceptions. But only one exception will be executed when an exception occurs.

Example

In this example, we will ask the user for the denominator value. If the user enters a number, the program will evaluate and produce the result.

If the user enters a non-numeric value then, the try block will throw a ValueError exception, and we can catch that using a first catch block ‘except ValueError’ by printing the message ‘Entered value is wrong’.

And suppose the user enters the denominator as zero. In that case, the try block will throw a ZeroDivisionError, and we can catch that using a second catch block by printing the message ‘Can’t divide by zero’.

try:

a = int(input("Enter value of a:"))

b = int(input("Enter value of b:"))

c = a/b

print("The answer of a divide by b:", c)

except ValueError:

print("Entered value is wrong")

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("Can't divide by zero")Output 1:

Enter value of a:Ten Entered value is wrong

Output 2:

Enter value of a:10 Enter value of b:0 Can't divide by zero

Output 3:

Enter value of a:10 Enter value of b:2 The answer of a divide by b: 5.0

Handle multiple exceptions with a single except clause

We can also handle multiple exceptions with a single except clause. For that, we can use an tuple of values to specify multiple exceptions in an except clause.

Example

Let’s see how to specifiy two exceptions in the single except clause.

try:

a = int(input("Enter value of a:"))

b = int(input("Enter value of b:"))

c = a / b

print("The answer of a divide by b:", c)

except(ValueError, ZeroDivisionError):

print("Please enter a valid value")Using try with finally

Python provides the finally block, which is used with the try block statement. The finally block is used to write a block of code that must execute, whether the try block raises an error or not.

Mainly, the finally block is used to release the external resource. This block provides a guarantee of execution.

Clean-up actions using finally

Sometimes we want to execute some action at any cost, even if an error occurred in a program. In Python, we can perform such actions using a finally statement with a try and except statement.

The block of code written in the finally block will always execute even there is an exception in the try and except block.

If an exception is not handled by except clause, then finally block executes first, then the exception is thrown. This process is known as clean-up action.

Syntax

try:

# block of code

# this may throw an exception

finally:

# block of code

# this will always be executed

# after the try and any except block Example

try:

a = int(input("Enter value of a:"))

b = int(input("Enter value of b:"))

c = a / b

print("The answer of a divide by b:", c)

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("Can't divide with zero")

finally:

print("Inside a finally block")Output 1:

Enter value of a:20 Enter value of b:5 The answer of a divide by b: 4.0 Inside a finally block

Output 2:

Enter value of a:20 Enter value of b:0 Can't divide with zero Inside a finally block

In the above example, we can see we divide a number by 0 and get an error, and the program terminates normally. In this case, the finally block was also executed.

Using try with else clause

Sometimes we might want to run a specific block of code. In that case, we can use else block with the try-except block. The else block will be executed if and only if there are no exception is the try block. For these cases, we can use the optional else statement with the try statement.

Why to use else block with try?

Use else statemen with try block to check if try block executed without any exception or if you want to run a specific code only if an exception is not raised

Syntax

try:

# block of code

except Exception1:

# block of code

else:

# this code executes when exceptions not occured try: Thetryblock for risky code that can throw an exception.except: Theexceptblock to handle error raised in atryblock.else: Theelseblock is executed if there is no exception.

Example

try:

a = int(input("Enter value of a:"))

b = int(input("Enter value of b:"))

c = a / b

print("a/b = %d" % c)

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("Can't divide by zero")

else:

print("We are in else block ")Output 1

Enter value of a: 20 Enter value of b:4 a/b = 5 We are in else block

Output 2

Enter value of a: 20 Enter value of b:0 Can't divide by zero

Raising an Exceptions

In Python, the raise statement allows us to throw an exception. The single arguments in the raise statement show an exception to be raised. This can be either an exception object or an Exception class that is derived from the Exception class.

The raise statement is useful in situations where we need to raise an exception to the caller program. We can raise exceptions in cases such as wrong data received or any validation failure.

Follow the below steps to raise an exception:

- Create an exception of the appropriate type. Use the existing built-in exceptions or create your won exception as per the requirement.

- Pass the appropriate data while raising an exception.

- Execute a raise statement, by providing the exception class.

The syntax to use the raise statement is given below.

raise Exception_class,<value> Example

In this example, we will throw an exception if interest rate is greater than 100.

def simple_interest(amount, year, rate):

try:

if rate > 100:

raise ValueError(rate)

interest = (amount * year * rate) / 100

print('The Simple Interest is', interest)

return interest

except ValueError:

print('interest rate is out of range', rate)

print('Case 1')

simple_interest(800, 6, 8)

print('Case 2')

simple_interest(800, 6, 800)Output:

Case 1 The Simple Interest is 384.0 Case 2 interest rate is out of range 800

Exception Chaining

The exception chaining is available only in Python 3. The raise statements allow us as optional from statement, which enables chaining exceptions. So we can implement exception chaining in python3 by using raise…from clause to chain exception.

When exception raise, exception chaining happens automatically. The exception can be raised inside except or finally block section. We also disabled exception chaining by using from None idiom.

Example

try:

a = int(input("Enter value of a:"))

b = int(input("Enter value of b:"))

c = a/b

print("The answer of a divide by b:", c)

except ZeroDivisionError as e:

raise ValueError("Division failed") from e

# Output: Enter value of a:10

# Enter value of b:0

# ValueError: Division failedIn the above example, we use exception chaining using raise...from clause and raise ValueError division failed.

Custom and User-defined Exceptions

Sometimes we have to define and raise exceptions explicitly to indicate that something goes wrong. Such a type of exception is called a user-defined exception or customized exception.

The user can define custom exceptions by creating a new class. This new exception class has to derive either directly or indirectly from the built-in class Exception. In Python, most of the built-in exceptions also derived from the Exception class.

class Error(Exception):

"""Base class for other exceptions"""

pass

class ValueTooSmallError(Error):

"""Raised when the input value is small"""

pass

class ValueTooLargeError(Error):

"""Raised when the input value is large"""

pass

while(True):

try:

num = int(input("Enter any value in 10 to 50 range: "))

if num < 10:

raise ValueTooSmallError

elif num > 50:

raise ValueTooLargeError

break

except ValueTooSmallError:

print("Value is below range..try again")

except ValueTooLargeError:

print("value out of range...try again")

print("Great! value in correct range.")Output

Enter any value in 10 to 50 range: 5

Value is below range..try again

Enter any value in 10 to 50 range: 60

value out of range...try again

Enter any value in 10 to 50 range: 11

Great! value in correct range.In the above example, we create two custom classes or user-defined classes with names, ValueTooSmallError and ValueTooLargeError.When the entered value is below the range, it will raise ValueTooSmallError and if the value is out of then, it will raise ValueTooLargeError.

Customizing Exception Classes

We can customize the classes by accepting arguments as per our requirements. Any custom exception class must be Extending from BaseException class or subclass of BaseException.

In the above example, we create a custom class that is inherited from the base class Exception. This class takes one argument age. When entered age is negative, it will raise NegativeAgeError.

class NegativeAgeError(Exception):

def __init__(self, age, ):

message = "Age should not be negative"

self.age = age

self.message = message

age = int(input("Enter age: "))

if age < 0:

raise NegativeAgeError(age)

# Output:

# raise NegativeAgeError(age)

# __main__.NegativeAgeError: -9

Output:

Enter age: -28

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "E:/demos/exception.py", line 11, in

raise NegativeAgeError(age)

main.NegativeAgeError: -28

Done

Exception Lifecycle

- When an exception is raised, The runtime system attempts to find a handler for the exception by backtracking the ordered list of methods calls. This is known as the call stack.

- If a handler is found (i.e., if

exceptblock is located), there are two cases in theexceptblock; either exception is handled or possibly re-thrown. - If the handler is not found (the runtime backtracks to the method chain’s last calling method), the exception stack trace is printed to the standard error console, and the application stops its execution.

Example

def sum_of_list(numbers):

return sum(numbers)

def average(sum, n):

# ZeroDivisionError if list is empty

return sum / n

def final_data(data):

for item in data:

print("Average:", average(sum_of_list(item), len(item)))

list1 = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50]

list2 = [100, 200, 300, 400, 500]

# empty list

list3 = []

lists = [list1, list2, list3]

final_data(lists)Output

Average: 30.0

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "E:/demos/exceptions.py", line 17, in

final_data(lists)

File "E:/demos/exceptions.py", line 11, in final_data

print("Average:", average(sum_of_list(item), len(item)))

Average: 300.0

File "E:/demos/exceptions.py", line 6, in average

return sum / n

ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

The above stack trace shows the methods that are being called from main() until the method created an exception condition. It also shows line numbers.

Warnings

Several built-in exceptions represent warning categories. This categorization is helpful to be able to filter out groups of warnings.

The warning doesn’t stop the execution of a program it indicates the possible improvement

Below is the list of warning exception

| Waring Class | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Warning | Base class for warning categories |

| UserWarning | Base class for warnings generated by user code |

| DeprecationWarning | Warnings about deprecated features |

| PendingDeprecationWarning | Warnings about features that are obsolete and expected to be deprecated in the future, but are not deprecated at the moment. |

| SyntaxWarning | Warnings about dubious syntax |

| RuntimeWarning | Warnings about the dubious runtime behavior |

| FutureWarning | Warnings about probable mistakes in module imports |

| ImportWarning | Warnings about probable mistakes in module imports |

| UnicodeWarning | Warnings related to Unicode data |

| BytesWarning | Warnings related to bytes and bytearray. |

| ResourceWarning | Warnings related to resource usage |

При выполнении заданий к главам вы скорее всего нередко сталкивались с возникновением различных ошибок. На этой главе мы изучим подход, который позволяет обрабатывать ошибки после их возникновения.

Напишем программу, которая будет считать обратные значения для целых чисел из заданного диапазона и выводить их в одну строку с разделителем «;». Один из вариантов кода для решения этой задачи выглядит так: