Raise, return, and how to never fail silently in Python.

I hear this question a lot: “Do I raise or return this error in Python?”

The right answer will depend on the goals of your application logic. You want to ensure your Python code doesn’t fail silently, saving you and your teammates from having to hunt down deeply entrenched errors.

Here’s the difference between raise and return when handling failures in Python.

When to raise

The

raisestatement allows the programmer to force a specific exception to occur. (8.4 Raising Exceptions)

Use raise when you know you want a specific behavior, such as:

raise TypeError("Wanted strawberry, got grape.")

Raising an exception terminates the flow of your program, allowing the exception to bubble up the call stack. In the above example, this would let you explicitly handle TypeError later. If TypeError goes unhandled, code execution stops and you’ll get an unhandled exception message.

Raise is useful in cases where you want to define a certain behavior to occur. For example, you may choose to disallow certain words in a text field:

if "raisins" in text_field:

raise ValueError("That word is not allowed here")

Raise takes an instance of an exception, or a derivative of the Exception class. Here are all of Python’s built-in exceptions.

Raise can help you avoid writing functions that fail silently. For example, this code will not raise an exception if JAM doesn’t exist:

import os

def sandwich_or_bust(bread: str) -> str:

jam = os.getenv("JAM")

return bread + str(jam) + bread

s = sandwich_or_bust("U0001F35E")

print(s)

# Prints "🍞None🍞" which is not very tasty.

To cause the sandwich_or_bust() function to actually bust, add a raise:

import os

def sandwich_or_bust(bread: str) -> str:

jam = os.getenv("JAM")

if not jam:

raise ValueError("There is no jam. Sad bread.")

return bread + str(jam) + bread

s = sandwich_or_bust("U0001F35E")

print(s)

# ValueError: There is no jam. Sad bread.

Any time your code interacts with an external variable, module, or service, there is a possibility of failure. You can use raise in an if statement to help ensure those failures aren’t silent.

Raise in try and except

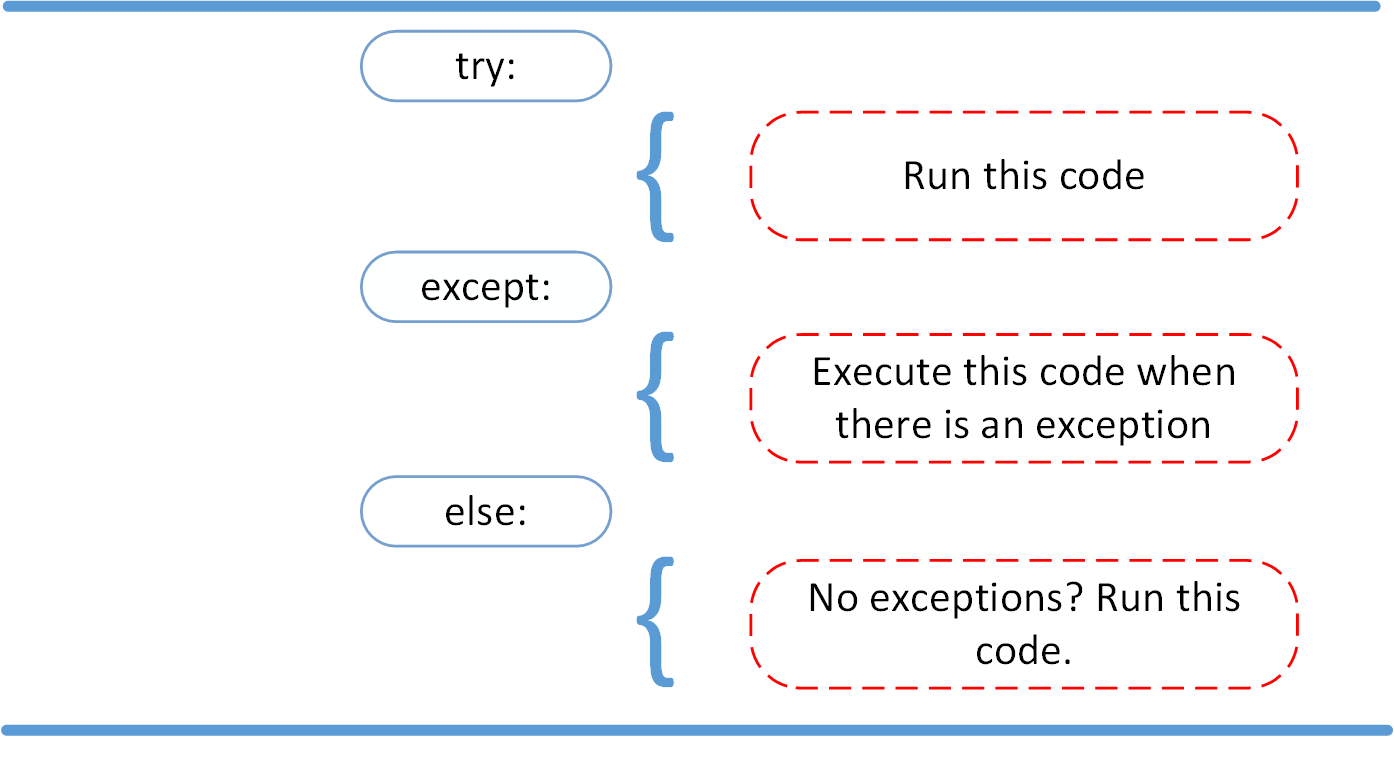

To handle a possible failure by taking an action if there is one, use a try … except statement.

try:

s = sandwich_or_bust("U0001F35E")

print(s)

except ValueError:

buy_more_jam()

raise

This lets you buy_more_jam() before re-raising the exception. If you want to propagate a caught exception, use raise without arguments to avoid possible loss of the stack trace.

If you don’t know that the exception will be a ValueError, you can also use a bare except: or catch any derivative of the Exception class with except Exception:. Whenever possible, it’s better to raise and handle exceptions explicitly.

Use else for code to execute if the try does not raise an exception. For example:

try:

s = sandwich_or_bust("U0001F35E")

print(s)

except ValueError:

buy_more_jam()

raise

else:

print("Congratulations on your sandwich.")

You could also place the print line within the try block, however, this is less explicit.

When to return

When you use return in Python, you’re giving back a value. A function returns to the location it was called from.

While it’s more idiomatic to raise errors in Python, there may be occasions where you find return to be more applicable.

For example, if your Python code is interacting with other components that do not handle exception classes, you may want to return a message instead. Here’s an example using a try … except statement:

from typing import Union

def share_sandwich(sandwich: int) -> Union[float, Exception]:

try:

bad_math = sandwich / 0

return bad_math

except Exception as e:

return e

s = share_sandwich(1)

print(s)

# Prints "division by zero"

Note that when you return an Exception class object, you’ll get a representation of its associated value, usually the first item in its list of arguments. In the example above, this is the string explanation of the exception. In some cases, it may be a tuple with other information about the exception.

You may also use return to give a specific error object, such as with HttpResponseNotFound in Django. For example, you may want to return a 404 instead of a 403 for security reasons:

if object.owner != request.user:

return HttpResponseNotFound

Using return can help you write appropriately noisy code when your function is expected to give back a certain value, and when interacting with outside elements.

The most important part

Silent failures create some of the most frustrating bugs to find and fix. You can help create a pleasant development experience for yourself and your team by using raise and return to ensure that errors are handled in your Python code.

I write about good development practices and how to improve productivity as a software developer. You can get these tips right in your inbox by signing up below!

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Raising and Handling Python Exceptions

A Python program terminates as soon as it encounters an error. In Python, an error can be a syntax error or an exception. In this article, you will see what an exception is and how it differs from a syntax error. After that, you will learn about raising exceptions and making assertions. Then, you’ll finish with a demonstration of the try and except block.

Exceptions versus Syntax Errors

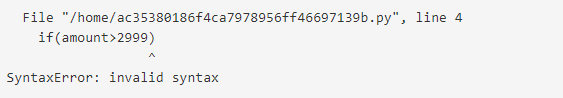

Syntax errors occur when the parser detects an incorrect statement. Observe the following example:

>>> print( 0 / 0 ))

File "<stdin>", line 1

print( 0 / 0 ))

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

The arrow indicates where the parser ran into the syntax error. In this example, there was one bracket too many. Remove it and run your code again:

>>> print( 0 / 0)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ZeroDivisionError: integer division or modulo by zero

This time, you ran into an exception error. This type of error occurs whenever syntactically correct Python code results in an error. The last line of the message indicated what type of exception error you ran into.

Instead of showing the message exception error, Python details what type of exception error was encountered. In this case, it was a ZeroDivisionError. Python comes with various built-in exceptions as well as the possibility to create self-defined exceptions.

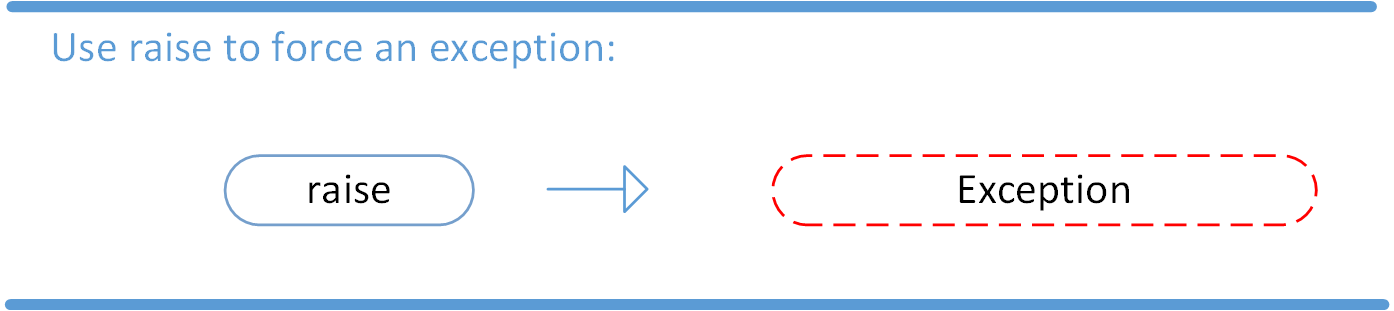

Raising an Exception

We can use raise to throw an exception if a condition occurs. The statement can be complemented with a custom exception.

If you want to throw an error when a certain condition occurs using raise, you could go about it like this:

x = 10

if x > 5:

raise Exception('x should not exceed 5. The value of x was: {}'.format(x))

When you run this code, the output will be the following:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<input>", line 4, in <module>

Exception: x should not exceed 5. The value of x was: 10

The program comes to a halt and displays our exception to screen, offering clues about what went wrong.

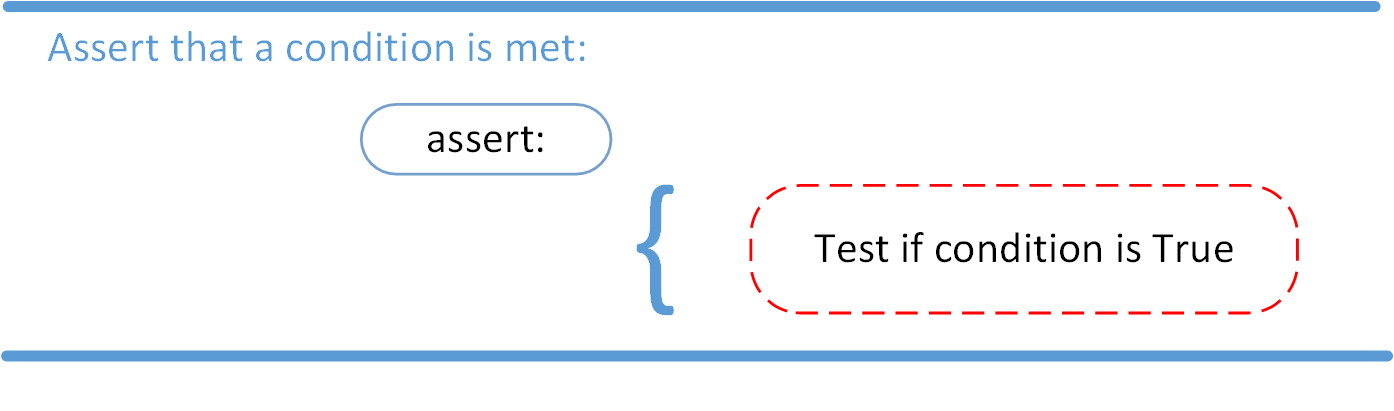

The AssertionError Exception

Instead of waiting for a program to crash midway, you can also start by making an assertion in Python. We assert that a certain condition is met. If this condition turns out to be True, then that is excellent! The program can continue. If the condition turns out to be False, you can have the program throw an AssertionError exception.

Have a look at the following example, where it is asserted that the code will be executed on a Linux system:

import sys

assert ('linux' in sys.platform), "This code runs on Linux only."

If you run this code on a Linux machine, the assertion passes. If you were to run this code on a Windows machine, the outcome of the assertion would be False and the result would be the following:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<input>", line 2, in <module>

AssertionError: This code runs on Linux only.

In this example, throwing an AssertionError exception is the last thing that the program will do. The program will come to halt and will not continue. What if that is not what you want?

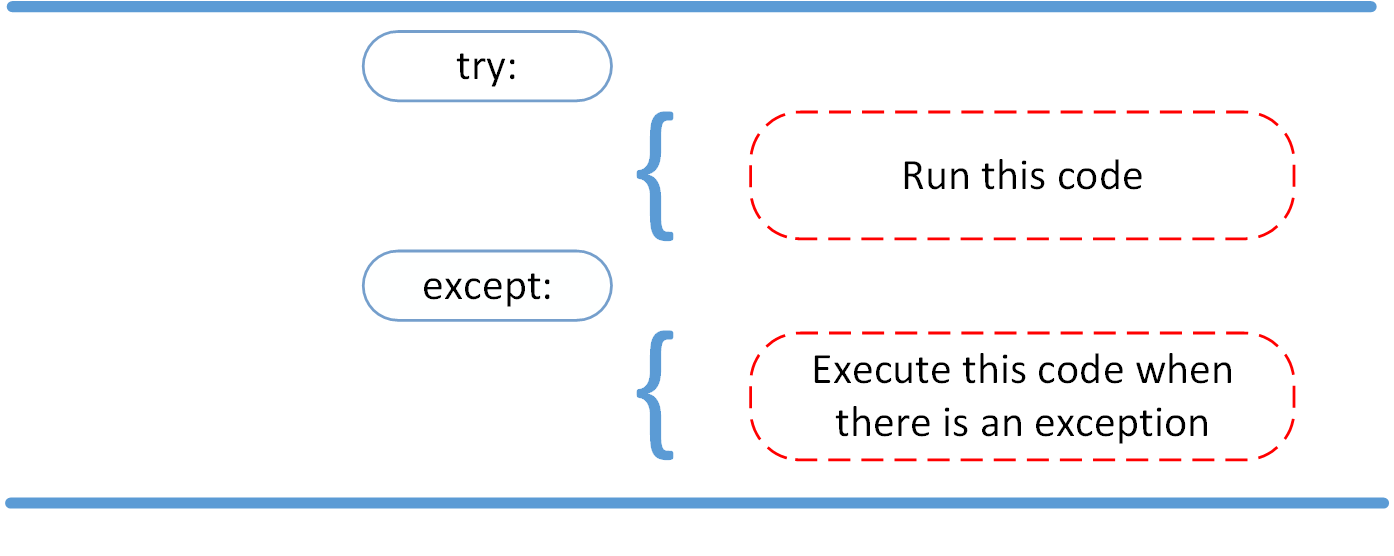

The try and except Block: Handling Exceptions

The try and except block in Python is used to catch and handle exceptions. Python executes code following the try statement as a “normal” part of the program. The code that follows the except statement is the program’s response to any exceptions in the preceding try clause.

As you saw earlier, when syntactically correct code runs into an error, Python will throw an exception error. This exception error will crash the program if it is unhandled. The except clause determines how your program responds to exceptions.

The following function can help you understand the try and except block:

def linux_interaction():

assert ('linux' in sys.platform), "Function can only run on Linux systems."

print('Doing something.')

The linux_interaction() can only run on a Linux system. The assert in this function will throw an AssertionError exception if you call it on an operating system other then Linux.

You can give the function a try using the following code:

try:

linux_interaction()

except:

pass

The way you handled the error here is by handing out a pass. If you were to run this code on a Windows machine, you would get the following output:

You got nothing. The good thing here is that the program did not crash. But it would be nice to see if some type of exception occurred whenever you ran your code. To this end, you can change the pass into something that would generate an informative message, like so:

try:

linux_interaction()

except:

print('Linux function was not executed')

Execute this code on a Windows machine:

Linux function was not executed

When an exception occurs in a program running this function, the program will continue as well as inform you about the fact that the function call was not successful.

What you did not get to see was the type of error that was thrown as a result of the function call. In order to see exactly what went wrong, you would need to catch the error that the function threw.

The following code is an example where you capture the AssertionError and output that message to screen:

try:

linux_interaction()

except AssertionError as error:

print(error)

print('The linux_interaction() function was not executed')

Running this function on a Windows machine outputs the following:

Function can only run on Linux systems.

The linux_interaction() function was not executed

The first message is the AssertionError, informing you that the function can only be executed on a Linux machine. The second message tells you which function was not executed.

In the previous example, you called a function that you wrote yourself. When you executed the function, you caught the AssertionError exception and printed it to screen.

Here’s another example where you open a file and use a built-in exception:

try:

with open('file.log') as file:

read_data = file.read()

except:

print('Could not open file.log')

If file.log does not exist, this block of code will output the following:

This is an informative message, and our program will still continue to run. In the Python docs, you can see that there are a lot of built-in exceptions that you can use here. One exception described on that page is the following:

Exception

FileNotFoundErrorRaised when a file or directory is requested but doesn’t exist. Corresponds to errno ENOENT.

To catch this type of exception and print it to screen, you could use the following code:

try:

with open('file.log') as file:

read_data = file.read()

except FileNotFoundError as fnf_error:

print(fnf_error)

In this case, if file.log does not exist, the output will be the following:

[Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'file.log'

You can have more than one function call in your try clause and anticipate catching various exceptions. A thing to note here is that the code in the try clause will stop as soon as an exception is encountered.

Look at the following code. Here, you first call the linux_interaction() function and then try to open a file:

try:

linux_interaction()

with open('file.log') as file:

read_data = file.read()

except FileNotFoundError as fnf_error:

print(fnf_error)

except AssertionError as error:

print(error)

print('Linux linux_interaction() function was not executed')

If the file does not exist, running this code on a Windows machine will output the following:

Function can only run on Linux systems.

Linux linux_interaction() function was not executed

Inside the try clause, you ran into an exception immediately and did not get to the part where you attempt to open file.log. Now look at what happens when you run the code on a Linux machine:

[Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'file.log'

Here are the key takeaways:

- A

tryclause is executed up until the point where the first exception is encountered. - Inside the

exceptclause, or the exception handler, you determine how the program responds to the exception. - You can anticipate multiple exceptions and differentiate how the program should respond to them.

- Avoid using bare

exceptclauses.

The else Clause

In Python, using the else statement, you can instruct a program to execute a certain block of code only in the absence of exceptions.

Look at the following example:

try:

linux_interaction()

except AssertionError as error:

print(error)

else:

print('Executing the else clause.')

If you were to run this code on a Linux system, the output would be the following:

Doing something.

Executing the else clause.

Because the program did not run into any exceptions, the else clause was executed.

You can also try to run code inside the else clause and catch possible exceptions there as well:

try:

linux_interaction()

except AssertionError as error:

print(error)

else:

try:

with open('file.log') as file:

read_data = file.read()

except FileNotFoundError as fnf_error:

print(fnf_error)

If you were to execute this code on a Linux machine, you would get the following result:

Doing something.

[Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'file.log'

From the output, you can see that the linux_interaction() function ran. Because no exceptions were encountered, an attempt to open file.log was made. That file did not exist, and instead of opening the file, you caught the FileNotFoundError exception.

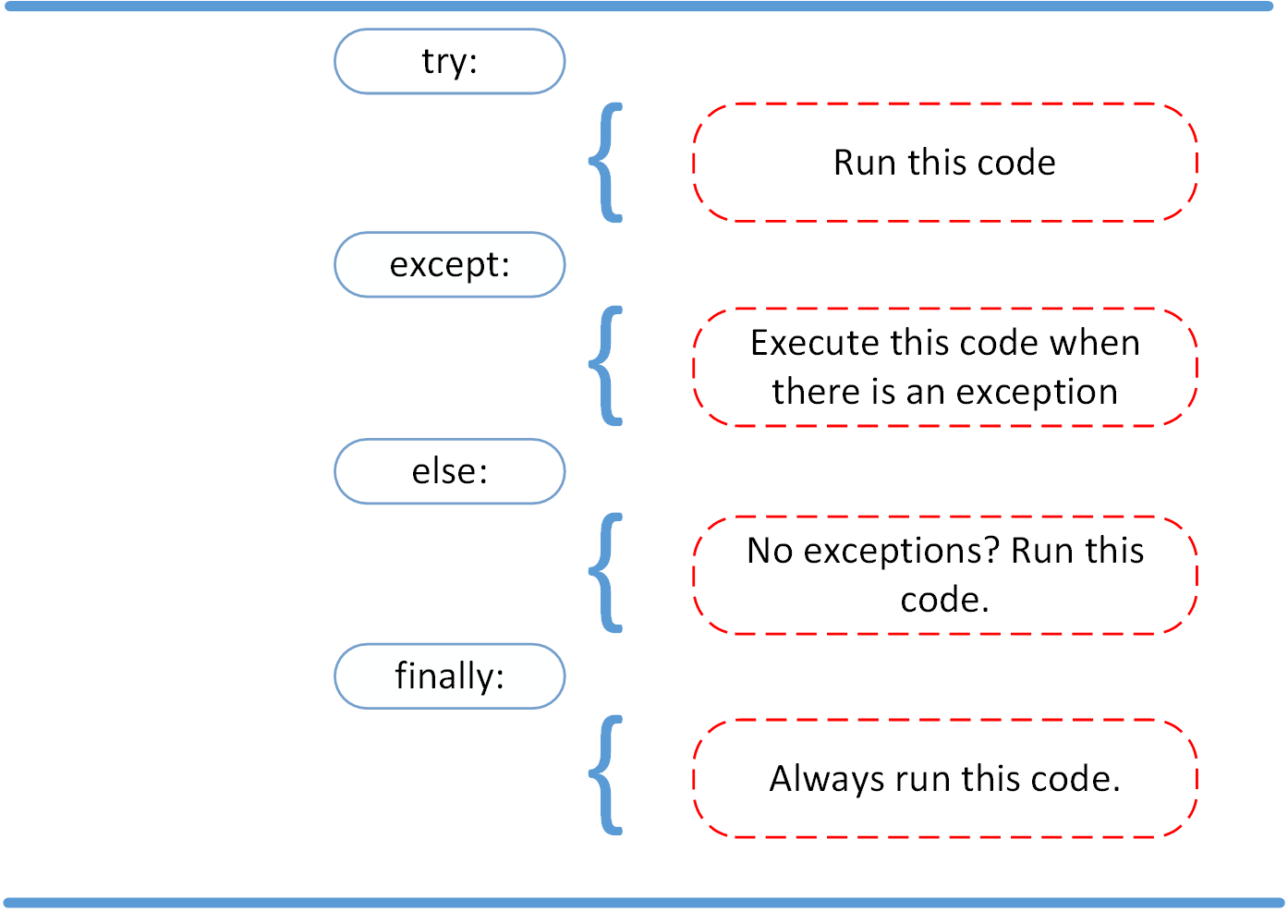

Cleaning Up After Using finally

Imagine that you always had to implement some sort of action to clean up after executing your code. Python enables you to do so using the finally clause.

Have a look at the following example:

try:

linux_interaction()

except AssertionError as error:

print(error)

else:

try:

with open('file.log') as file:

read_data = file.read()

except FileNotFoundError as fnf_error:

print(fnf_error)

finally:

print('Cleaning up, irrespective of any exceptions.')

In the previous code, everything in the finally clause will be executed. It does not matter if you encounter an exception somewhere in the try or else clauses. Running the previous code on a Windows machine would output the following:

Function can only run on Linux systems.

Cleaning up, irrespective of any exceptions.

Summing Up

After seeing the difference between syntax errors and exceptions, you learned about various ways to raise, catch, and handle exceptions in Python. In this article, you saw the following options:

raiseallows you to throw an exception at any time.assertenables you to verify if a certain condition is met and throw an exception if it isn’t.- In the

tryclause, all statements are executed until an exception is encountered. exceptis used to catch and handle the exception(s) that are encountered in the try clause.elselets you code sections that should run only when no exceptions are encountered in the try clause.finallyenables you to execute sections of code that should always run, with or without any previously encountered exceptions.

Hopefully, this article helped you understand the basic tools that Python has to offer when dealing with exceptions.

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Raising and Handling Python Exceptions

Introduction

Software applications don’t run perfectly all the time. Despite intensive debugging and multiple testing levels, applications still fail. Bad data, broken network connectivity, corrupted databases, memory pressures, and unexpected user inputs can all prevent an application from performing normally. When such an event occurs, and the app is unable to continue its normal flow, this is known as an exception. And it’s your application’s job—and your job as a coder—to catch and handle these exceptions gracefully so that your app keeps working.

Install the Python SDK to identify and fix exceptions

What Are Python Exceptions?

Exceptions in Python applications can happen for many of the reasons stated above and more; and if they aren’t handled well, these exceptions can cause the program to crash, causing data loss, or worse, corrupted data. As a Python developer, you need to think about possible exception situations and include error handling in your code.

Fortunately, Python comes with a robust error handling framework. Using structured exception handling and a set of pre-defined exceptions, Python programs can determine the error type at run time and act accordingly. These can include actions like taking an alternate path, using default values, or prompting for correct input.

This article will show you how to raise exceptions in your Python code and how to address exceptions.

Difference Between Python Syntax Errors and Python Exceptions

Before diving in, it’s important to understand the two types of unwanted conditions in Python programming—syntax error and exception.

The syntax error exception occurs when the code does not conform to Python keywords, naming style, or programming structure. The interpreter sees the invalid syntax during its parsing phase and raises a SyntaxError exception. The program stops and fails at the point where the syntax error happened. That’s why syntax errors are exceptions that can’t be handled.

Here’s an example code block with a syntax error (note the absence of a colon after the “if” condition in parentheses):

a = 10

b = 20

if (a < b)

print('a is less than b')

c = 30

print(c)The interpreter picks up the error and points out the line number. Note how it doesn’t proceed after the syntax error:

File "test.py", line 4

if (a < b)

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

Process finished with exit code 1On the other hand, an exception happens when the code has no syntax error but encounters other error situations. These conditions can be addressed within the code—either in the current function or in the calling stack. In this sense, exceptions are not fatal. A Python program can continue to run if it gracefully handles the exception.

Here is an example of a Python code that doesn’t have any syntax errors. It’s trying to run an arithmetic operation on two string variables:

a = 'foo'

b = 'bar'

print(a % b)The exception raised is TypeError:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "test.py", line 4, in

print(a % b)

TypeError: not all arguments converted during string formatting

Process finished with exit code 1Python throws the TypeError exception when there are wrong data types. Similar to TypeError, there are several built-in exceptions like:

- ModuleNotFoundError

- ImportError

- MemoryError

- OSError

- SystemError

- … And so on

You can refer to the Python documentation for a full list of exceptions.

How to Throw an Exception in Python

Sometimes you want Python to throw a custom exception for error handling. You can do this by checking a condition and raising the exception, if the condition is True. The raised exception typically warns the user or the calling application.

You use the “raise” keyword to throw a Python exception manually. You can also add a message to describe the exception

Here is a simple example: Say you want the user to enter a date. The date has to be either today or in the future. If the user enters a past date, the program should raise an exception:

Python Throw Exception Example

from datetime import datetime

current_date = datetime.now()

print("Current date is: " + current_date.strftime('%Y-%m-%d'))

dateinput = input("Enter date in yyyy-mm-dd format: ")

# We are not checking for the date input format here

date_provided = datetime.strptime(dateinput, '%Y-%m-%d')

print("Date provided is: " + date_provided.strftime('%Y-%m-%d'))

if date_provided.date() < current_date.date():

raise Exception("Date provided can't be in the past")To test the code, we enter a date older than the current date. The “if” condition evaluates to true and raises the exception:

Current date is: 2021-01-24

Enter date in yyyy-mm-dd format: 2021-01-22

Date provided is: 2021-01-22

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "test.py", line 13, in

raise Exception("Date provided can't be in the past")

Exception: Date provided can't be in the past

Process finished with exit code 1Instead of raising a generic exception, we can specify a type for it, too:

if (date_provided.date() < current_date.date()):

raise ValueError("Date provided can't be in the past")With a similar input as before, Python will now throw this exception:

raise ValueError("Date provided can't be in the past")

ValueError: Date provided can't be in the pastUsing AssertionError in Python Exception Throwing

Another way to raise an exception is to use assertion. With assertion, you assert a condition to be true before running a statement. If the condition evaluates to true, the statement runs, and the control continues to the next statement. However, if the condition evaluates to false, the program throws an AssertionError. The diagram below shows the logical flow:

Using AssertionError, we can rewrite the code snippet in the last section like this:

from datetime import datetime

current_date = datetime.now()

print("Current date is: " + current_date.strftime('%Y-%m-%d'))

dateinput = input("Enter date in yyyy-mm-dd format: ")

# We are not checking for the date input format here

date_provided = datetime.strptime(dateinput, '%Y-%m-%d')

print("Date provided is: " + date_provided.strftime('%Y-%m-%d'))

assert(date_provided.date() >= current_date.date()), "Date provided can't be in the past"Note how we removed the “if” condition and are now asserting that the date provided is greater than or equal to the current date. When inputting an older date, the AssertionError displays:

Current date is: 2021-01-24

Enter date in yyyy-mm-dd format: 2021-01-23

Traceback (most recent call last):

Date provided is: 2021-01-23

File "test.py", line 12, in

assert(date_provided.date() >= current_date.date()), "Date provided can't be in the past"

AssertionError: Date provided can't be in the past

Process finished with exit code 1Catching Python Exceptions with Try-Except

Now that you understand how to throw exceptions in Python manually, it’s time to see how to handle those exceptions. Most modern programming languages use a construct called “try-catch” for exception handling. With Python, its basic form is “try-except”. The try-except block looks like this:

Python Try Catch Exception Example

...

try:

<--program code-->

except:

<--exception handling code-->

<--program code-->

...Here, the program flow enters the “try” block. If there is an exception, the control jumps to the code in the “except” block. The error handling code you put in the “except” block depends on the type of error you think the code in the “try” block may encounter.

Here’s an example of Python’s “try-except” (often mistakenly referred to as “try-catch-exception”). Let’s say we want our code to run only if the Python version is 3. Using a simple assertion in the code looks like this:

import sys

assert (sys.version_info[0] == 3), "Python version must be 3"If the of Python version is not 3, the error message looks like this:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "test.py", line 2, in

assert (sys.version_info[0] == 3), "Python version must be 3"

AssertionError: Python version must be 3

Process finished with exit code 1Instead of letting the program fail with an unhandled exception and showing an ugly error message, we could use a try-except block for a graceful exit.

import sys

try:

assert (sys.version_info[0] == 3), "Python version must be 3"

except Exception as e:

print(e)

rollbar.report_exc_info()Now, the error message is much cleaner:

Python version must be 3

The “except” keyword in the construct also accepts the type of error you want to handle. To illustrate this, let’s go back to our date script from the last section. In that script, we assumed the user will enter a date in “YYYY-MM-DD” format. However, as a developer, you should cater to any type of erroneous data instead of depending on the user. For example, some exception scenarios can be:

- No date entered (blank)

- Text entered

- Number entered

- Time entered

- Special characters entered

- Different date format entered (such as “dd/mm/yyyy”)

To address all these conditions, we can rewrite the code block as shown below. This will catch any ValueError exception raised when meeting any of the above conditions:

from datetime import datetime

current_date = datetime.now()

print("Current date is: " + current_date.strftime('%Y-%m-%d'))

dateinput = input("Enter date in yyyy-mm-dd format: ")

try:

date_provided = datetime.strptime(dateinput, '%Y-%m-%d')

except ValueError as e:

print(e)

rollbar.report_exc_info()

exit()

print("Date provided is: " + date_provided.strftime('%Y-%m-%d'))

assert(date_provided.date() >= current_date.date()), "Date provided can't be in the past"In this case, the program will exit gracefully if the date isn’t correctly formatted.

You can include multiple “except” blocks for the “try” block to trap different types of exceptions. Each “except” block will address a specific type of error:

...

try:

<--program code-->

except <--Exception Type 1-->:

<--exception handling code-->

except <--Exception Type 2-->:

<--exception handling code-->

except <--Exception Type 3-->:

<--exception handling code-->

...Here’s a very simple example:

num0 = 10

try:

num1 = input("Enter 1st number:")

num2 = input("Enter 2nd number:")

result = (int(num1) * int(num2))/(num0 * int(num2))

except ValueError as ve:

print(ve)

rollbar.report_exc_info()

exit()

except ZeroDivisionError as zde:

print(zde)

rollbar.report_exc_info()

exit()

except TypeError as te:

print(te)

rollbar.report_exc_info()

exit()

except:

print('Unexpected Error!')

rollbar.report_exc_info()

exit()

print(result)We can test this program with different values:

Enter 1st number:1

Enter 2nd number:0

division by zero

Enter 1st number:

Enter 2nd number:6

invalid literal for int() with base 10: ''

Enter 1st number:12.99

Enter 2nd number:33

invalid literal for int() with base 10: '12.99'Catching Python Exceptions with Try-Except-Else

The next element in the Python “try-except” construct is “else”:

Python Try Except Else Example

...

try:

<--program code-->

except <--Exception Type 1-->:

<--exception handling code-->

except <--Exception Type 2-->:

<--exception handling code-->

except <--Exception Type 3-->:

<--exception handling code-->

...

else:

<--program code to run if "try" block doesn't encounter any error-->

...The “else” block runs if there are no exceptions raised from the “try” block. Looking at the code structure above, you can see the “else” in Python exception handling works almost the same as an “if-else” construct

To show how “else” works, we can slightly modify the arithmetic script’s code from the last section. If you look at the script, you will see we calculated the variable value of “result” using an arithmetic expression. Instead of putting this in the “try” block, you can move it to an “else” block. That way, the exception blocks any error raised while converting the input values to integers. And if there are no exceptions, the “else” block will perform the actual calculation:

num0 = 10

try:

num1 = int(input("Enter 1st number:"))

num2 = int(input("Enter 2nd number:"))

except ValueError as ve:

print(ve)

rollbar.report_exc_info()

exit()

except ZeroDivisionError as zde:

print(zde)

rollbar.report_exc_info()

exit()

except TypeError as te:

print(te)

rollbar.report_exc_info()

exit()

except:

print('Unexpected Error!')

rollbar.report_exc_info()

exit()

else:

result = (num1 * num2)/(num0 * num2)

print(result)

Using simple integers as input values runs the “else” block code:

Enter 1st number:2

Enter 2nd number:3

0.2And using erroneous data like empty values, decimal numbers, or strings cause the corresponding “except” block to run and skip the “else” block:

Enter 1st number:s

invalid literal for int() with base 10: 's'

Enter 1st number:20

Enter 2nd number:

invalid literal for int() with base 10: ''

Enter 1st number:5

Enter 2nd number:6.4

invalid literal for int() with base 10: '6.4'However, there’s still a possibility of unhandled exceptions when the “else” block runs:

Enter 1st number:1

Enter 2nd number:0

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "test.py", line 19, in

result = (num1 * num2)/(num0 * num2)

ZeroDivisionError: division by zeroAs you can see, both inputs are integers (1 and 0), and the “try” block successfully converts them to integers. When the “else” block runs, we see the exception.

So how do you handle errors in the “else” block? You guessed that right—you can use another “try-except-else” block within the outer “else” block:

Enter 1st number:1

Enter 2nd number:0

division by zeroCatching Python Exceptions with Try-Except-Else-Finally

Finally, we have the last optional block in Python error handling. And it’s literally called “finally”:

Python Try Finally Example

...

try:

<--program code-->

except <--Exception Type 1-->:

<--exception handling code-->

except <--Exception Type 2-->:

<--exception handling code-->

except <-->Exception Type 3-->>:

<--exception handling code-->

...

else:

<--program code to run if "try" block doesn't encounter any error-->

finally:

<--program code that runs regardless of errors in the "try" or "else" block-->The “finally” block runs whether or not the “try” block’s code raises an exception. If there’s an exception, the code in the corresponding “except” block will run, and then the code in the “finally” block will run. If there are no exceptions, the code in the “else” block will run (if there’s an “else” block), and then the code in the “finally” block will run.

Since the code in the “finally” block always runs, you want to keep your “clean up” codes here, such as:

- Writing status messages to log files

- Resetting counters, lists, arrays

- Closing open files

- Closing database connections

- Resetting object variables

- Disconnecting from network resources

- … And so on

Here’s an example of using “finally”:

try:

f = open("testfile.txt", 'r')

except FileNotFoundError as fne:

rollbar.report_exc_info()

print(fne)

print('Creating file...')

f = open("testfile.txt", 'w')

f.write('2')

else:

data=f.readline(1)

print(data)

finally:

print('Closing file')

f.close()Here, the “try” block tries to open a file for reading. If the file doesn’t exist, the exception block shows a warning message, creates the file, and adds a static value of “2” to it. If the file exists, the “else” block reads the first line of its content and prints that out. Finally, the “finally” block closes the file. This happens whether or not the file initially existed.

What we have discussed so far can be summarized in the flowchart below:

How Rollbar Can Help Log and Track Python Errors

Rollbar is a continuous code improvement platform for software development teams. It offers an automated way to capture Python errors and failed tests in real time from all application stack layers and across all environments. This allows creating a proactive and automated response to application errors. The diagram below shows how Rollbar works:

Rollbar natively works with a wide array of programming languages and frameworks, including Python. Python developers can install pyrollbar, Rollbar’s SDK for Python, using a tool like pip, importing the Rollbar class in the code, and sending Python exceptions to Rollbar. The code snippet below shows how easy it is:

import rollbar

rollbar.init('POST_SERVER_ITEM_ACCESS_TOKEN', 'dev')

try:

# some code

except TypeError:

rollbar.report_message('There is a data type mismatch', 'fatal')

except:

rollbar.report_exc_info()

Track, Analyze and Manage Errors With Rollbar

Managing errors and exceptions in your code is challenging. It can make deploying production code an unnerving experience. Being able to track, analyze, and manage errors in real-time can help you to proceed with more confidence. Rollbar automates error monitoring and triaging, making fixing errors easier than ever. Try it today.

Время прочтения

10 мин

Просмотры 31K

Одним из недостатков гибких языков, таких как Python, является предположение, что если что-то работает, то скорее всего оно сделано правильно. Я хочу написать скромное руководство по эффективному использованию исключений в Python, правильной их обработке и логировании.

Эффективная обработка исключений

Введение

Давайте рассмотрим следующую систему. У нас есть микросервис, который отвечает за:

· Прослушивание событий о новом заказе;

· Получение заказа из базы данных;

· Проверку состояния принтера;

· Печать квитанции;

· Отправка квитанции в налоговую систему (IRS).

В любой момент может сломаться что угодно. У вас могут возникнуть проблемы с объектом заказа, в котором может не быть нужной информации, или в принтере может закончиться бумага, или же сервис налоговой не будет работать, и вы не сможете синхронизировать с ними квитанцию об оплате, а может быть ваша база данных окажется недоступна.

Ваша задача правильно и проактивно реагировать на любую ситуацию, чтобы избежать ошибок при обработке новых заказов.

И примерно вот такой код на этот случай пишут люди (он, конечно, работает, но плохо и неэффективно):

class OrderService:

def emit(self, order_id: str) -> dict:

try:

order_status = status_service.get_order_status(order_id)

except Exception as e:

logger.exception(

f"Order {order_id} was not found in db "

f"to emit. Error: {e}."

)

raise e

(

is_order_locked_in_emission,

seconds_in_emission,

) = status_service.is_order_locked_in_emission(order_id)

if is_order_locked_in_emission:

logger.info(

"Redoing emission because "

"it was locked in that state after a long time! "

f"Time spent in that state: {seconds_in_emission} seconds "

f"Order: {order_id}, "

f"order_status: {order_status.value}"

)

elif order_status == OrderStatus.EMISSION_IN_PROGRESS:

logger.info("Aborting emission request because it is already in progress!")

return {"order_id": order_id, "order_status": order_status.value}

elif order_status == OrderStatus.EMISSION_SUCCESSFUL:

logger.info(

"Aborting emission because it already happened! "

f"Order: {order_id}, "

f"order_status: {order_status.value}"

)

return {"order_id": order_id, "order_status": order_status.value}

try:

receipt_note = receipt_service.create(order_id)

except Exception as e:

logger.exception(

"Error found during emission! "

f"Order: {order_id}, "

f"exception: {e}"

)

raise e

try:

broker.emit_receipt_note(receipt_note)

except Exception as e:

logger.exception(

"Emission failed! "

f"Order: {order_id}, "

f"exception: {e}"

)

raise e

order_status = status_service.get_order_status(order_id)

return {"order_id": order_id, "order_status": order_status.value}Сначала я сосредоточусь на том, что OrderService слишком много знает, и все эти данные делают его чем-то вроде blob, а чуть позже расскажу о правильной обработке и правильном логировании исключений.

Почему этот сервис — blob?

Этот сервис знает слишком много. Кто-то может сказать, что он знает только то, что ему нужно (то есть все шаги, связанные с формированием чека), но на самом деле он знает куда больше.

Он сосредоточен на создании ошибок (например, база данных, печать, статус заказа), а не на том, что он делает (например, извлекает, проверяет статус, генерирует, отправляет) и на том, как следует реагировать в случае сбоев.

В этом смысле мне кажется, что клиент учит сервис тому, какие исключения он может выдать. Если мы решим переиспользовать его на любом другом этапе (например, клиент захочет получить еще одну печатную копию более старого чека по заказу), мы скопируем большую часть этого кода.

Несмотря на то, что сервис работает нормально, поддерживать его трудно, и неясно, как один шаг соотносится с другим из-за повторяющихся блоков except между шагами, которые отвлекают наше внимание на вопрос «как» вместо того, чтобы думать о «когда».

Первое улучшение: делайте исключения конкретными

Давайте сначала сделаем исключения более точными и конкретными. Преимущества не видны сразу, поэтому я не буду тратить слишком много времени на объяснение этого прямо сейчас. Однако обратите внимание на то, как изменяется код.

Я выделю только то, что мы поменяли:

try:

order_status = status_service.get_order_status(order_id)

except Exception as e:

logger.exception(...)

raise OrderNotFound(order_id) from e

...

try:

...

except Exception as e:

logger.exception(...)

raise ReceiptGenerationFailed(order_id) from e

try:

broker.emit_receipt_note(receipt_note)

except Exception as e:

logger.exception(...)

raise ReceiptEmissionFailed(order_id) from eОбратите внимание, что на этот раз я пользуюсь from e, что является правильным способом создания одного исключения из другого и сохраняет полную трассировку стека.

Второе улучшение: не лезьте не в свое дело

Теперь, когда у нас есть кастомные исключения, мы можем перейти к мысли «не учите классы тому, что может пойти не так» — они сами скажут, если это случится!

# Services

class StatusService:

def get_order_status(order_id):

try:

...

except Exception as e:

raise OrderNotFound(order_id) from e

class ReceiptService:

def create(order_id):

try:

...

except Exception as e:

raise ReceiptGenerationFailed(order_id) from e

class Broker:

def emit_receipt_note(receipt_note):

try:

...

except Exception as e:

raise ReceiptEmissionFailed(order_id) from e

# Main class

class OrderService:

def emit(self, order_id: str) -> dict:

try:

order_status = status_service.get_order_status(order_id)

(

is_order_locked_in_emission,

seconds_in_emission,

) = status_service.is_order_locked_in_emission(order_id)

if is_order_locked_in_emission:

logger.info(

"Redoing emission because "

"it was locked in that state after a long time! "

f"Time spent in that state: {seconds_in_emission} seconds "

f"Order: {order_id}, "

f"order_status: {order_status.value}"

)

elif order_status == OrderStatus.EMISSION_IN_PROGRESS:

logger.info("Aborting emission request because it is already in progress!")

return {"order_id": order_id, "order_status": order_status.value}

elif order_status == OrderStatus.EMISSION_SUCCESSFUL:

logger.info(

"Aborting emission because it already happened! "

f"Order: {order_id}, "

f"order_status: {order_status.value}"

)

return {"order_id": order_id, "order_status": order_status.value}

receipt_note = receipt_service.create(order_id)

broker.emit_receipt_note(receipt_note)

order_status = status_service.get_order_status(order_id)

except OrderNotFound as e:

logger.exception(

f"Order {order_id} was not found in db "

f"to emit. Error: {e}."

)

raise

except ReceiptGenerationFailed as e:

logger.exception(

"Error found during emission! "

f"Order: {order_id}, "

f"exception: {e}"

)

raise

except ReceiptEmissionFailed as e:

logger.exception(

"Emission failed! "

f"Order: {order_id}, "

f"exception: {e}"

)

raise

else:

return {"order_id": order_id, "order_status": order_status.value}Как вам? Намного лучше, правда? У нас есть один блок try, который построен достаточно логично, чтобы понять, что произойдет дальше. Вы сгруппировали конкретные блоки, за исключением тех, которые помогают вам понять «когда» и крайние случаи. И, наконец, у вас есть блок else, в котором описано, что произойдет, если все отработает как надо.

Кроме того, пожалуйста, обратите внимание на то, что я сохранил инструкции raise без объявления объекта исключения. Это не опечатка. На самом деле, это правильный способ повторного вызова исключения: простой и немногословный.

Но это еще не все. Логирование продолжает меня раздражать.

Третье улучшение: улучшение логирования

Этот шаг напоминает мне принцип «говори, а не спрашивай», хотя это все же не совсем он. Вместо того, чтобы запрашивать подробности исключения и на их основе выдавать полезные сообщения, исключения должны выдавать их сами – в конце концов, я их конкретизировал!

### Exceptions

class OrderCreationException(Exception):

pass

class OrderNotFound(OrderCreationException):

def __init__(self, order_id):

self.order_id = order_id

super().__init__(

f"Order {order_id} was not found in db "

"to emit."

)

class ReceiptGenerationFailed(OrderCreationException):

def __init__(self, order_id):

self.order_id = order_id

super().__init__(

"Error found during emission! "

f"Order: {order_id}"

)

class ReceiptEmissionFailed(OrderCreationException):

def __init__(self, order_id):

self.order_id = order_id

super().__init__(

"Emission failed! "

f"Order: {order_id} "

)

### Main class

class OrderService:

def emit(self, order_id: str) -> dict:

try:

...

except OrderNotFound:

logger.exception("We got a database exception")

raise

except ReceiptGenerationFailed:

logger.exception("We got a problem generating the receipt")

raise

except ReceiptEmissionFailed:

logger.exception("Unable to emit the receipt")

raise

else:

return {"order_id": order_id, "order_status": order_status.value}Наконец-то мои глаза чувствуют облегчение. Поменьше повторений, пожалуйста! Примите к сведению, что рекомендуемый способ выглядит так, как я написал его выше: logger.exception(«ЛЮБОЕ СООБЩЕНИЕ»). Вам даже не нужно передавать исключение, поскольку его наличие уже подразумевается. Кроме того, кастомное сообщение, которое мы определили в каждом исключении с идентификатором order_id, будет отображаться в логах, поэтому вам не нужно повторяться и не нужно оперировать внутренними данными об исключениях.

Вот пример вывода ваших логов:

❯ python3 testme.py

Unable to emit the receipt # <<-- My log message

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/path/testme.py", line 19, in <module>

tryme()

File "/path/testme.py", line 14, in tryme

raise ReceiptEmissionFailed(order_id)

ReceiptEmissionFailed: Emission failed! Order: 10 # <<-- My exception messageТеперь всякий раз, когда я получаю это исключение, сообщение уже ясно и понятно, и мне не нужно помнить о логировании order_id, который я сгенерировал.

Последнее улучшение: упрощение

После более детального рассмотрения нашего окончательного кода, он кажется лучше, теперь его легко читать и поддерживать.

Но управляет ли OrderService бизнес-логикой? Я не думаю, что это сервис в общем смысле. Он больше похож на координацию вызовов настоящих сервисов обеспечивающих бизнес-логику, которая выглядит получше, чем паттерн facade.

Кроме того, можно заметить, что он запрашивает данные у status_service, чтобы что-то с ними сделать. (Что, на этот раз, действительно разрушает идею «Говори, а не спрашивай»).

Перейдем к упрощению.

class OrderFacade: # Renamed to match what it actually is

def emit(self, order_id: str) -> dict:

try:

# NOTE: info logging still happens inside

status_service.ensure_order_unlocked(order_id)

receipt_note = receipt_service.create(order_id)

broker.emit_receipt_note(receipt_note)

order_status = status_service.get_order_status(order_id)

except OrderAlreadyInProgress as e:

# New block

logger.info("Aborting emission request because it is already in progress!")

return {"order_id": order_id, "order_status": e.order_status.value}

except OrderAlreadyEmitted as e:

# New block

logger.info(f"Aborting emission because it already happened! {e}")

return {"order_id": order_id, "order_status": e.order_status.value}

except OrderNotFound:

logger.exception("We got a database exception")

raise

except ReceiptGenerationFailed:

logger.exception("We got a problem generating the receipt")

raise

except ReceiptEmissionFailed:

logger.exception("Unable to emit the receipt")

raise

else:

return {"order_id": order_id, "order_status": order_status.value}Мы только что создали новый метод ensure_order_unlocked для нашего status_service, который теперь отвечает за создание исключений/логирование в случае, если что-то идет не так.

Хорошо, а теперь скажите, насколько легче теперь стало это читать?

Я могу понять все return при беглом просмотре. Я знаю, что происходит, когда все идет хорошо, и как крайние случаи могут привести к разным результатам. И все это без прокрутки взад-вперед.

Теперь этот код такой же простой, каким (в основном) должен быть любой код.

Обратите внимание, что я решил вывести объект исключения e в логах, поскольку под капотом он будет запускать str(e), который вернет сообщение об исключении. Я подумал, что было бы полезно говорить подробно, поскольку мы не используем log.exception для этого блока, поэтому сообщение об исключении не будет отображаться.

Теперь давайте разберемся с некоторыми хитростями, которые помогут вам сделать код понятным для чтения и простым в обслуживании.

Эффективное создание исключений

Всегда классифицируйте свои исключения через базовое и расширяйте все конкретные исключения от него. С помощью этой полезной практики вы можете переиспользовать логику для связанного кода.

Исключения – это объекты, которые несут в себе информацию, поэтому не стесняйтесь добавлять кастомные атрибуты, которые могут помочь вам понять, что происходит. Не позволяйте своему бизнес-коду учить вас тому, как он должен быть построен, ведь с таким количеством сообщений и деталей потерять себя становится трудно.

# Base category exception

class OrderCreationException(Exception):

pass

# Specific error with custom message. Order id is required.

class OrderNotFound(OrderCreationException):

def __init__(self, order_id):

self.order_id = order_id # custom property

super().__init__(

f"Order {order_id} was not found in db "

f"to emit."

)

# Specific error with custom message. Order id is required.

class ReceiptGenerationFailed(OrderCreationException):

def __init__(self, order_id):

self.order_id = order_id # custom property

super().__init__(

"Error found during emission! "

f"Order: {order_id}"

)В примере выше я мог бы выйти за рамки и расширить базовый класс, чтобы всегда получать order_id, если мне это нужно. Этот совет поможет сохранить код сухим, поскольку мне не нужно быть многословным при создании исключений. Так можно использовать всего лишь одну переменную.

def func1(order_id):

raise OrderNotFound(order_id)

# instead of raise OrderNotFound(f"Can't find order {order_id}")

def func2(order_id):

raise OrderNotFound(order_id)

# instead of raise OrderNotFound(f"Can't find order {order_id}") В тестировании также будет больше смысла, поскольку я могу сделать assert order_id через строку.

assert e.order_id == order_id

# instead of assert order_id in str(e)Ловим и создаем исключения эффективно

Еще одна вещь, которую люди часто делают неправильно – это отлавливают и повторно создают исключения.

Согласно PEP 3134 Python, делать нужно следующим образом.

Повторное создание исключения

Обычной инструкции raise более чем достаточно.

try:

...

except CustomException as ex:

# do stuff (e.g. logging)

raiseСоздание одного исключения из другого

Этот вариант особо актуален, поскольку он сохраняет всю трассировку стека и помогает вашей команде отлаживать основные проблемы.

try:

...

except CustomException as ex:

raise MyNewException() from exЭффективное логирование исключений

Еще один совет, который не позволит вам быть слишком многословным.

Используйте logger.exception

Вам не нужно логировать объект исключения. Функция exception логгера предназначена для использования внутри блоков except. Она уже обрабатывает трассировку стека с информацией о выполнении и отображает, какое исключение вызвало ее, с сообщением, установленном на уровне ошибки!

try:

...

except CustomException:

logger.exception("custom message")А что, если это не ошибка?

Если по какой-то причине вы не хотите логировать исключение как ошибку, то возможно, это предупреждение или просто информация, как было показано выше.

Вы можете принять решение установить exc_info в True, если хотите сохранить трассировку стека. Кроме того, было бы неплохо использовать объект исключения внутри сообщения.

Источники

Документация Python:

· Python logging.logger.exception

· Python PEP 3134

Принципы и качество кода:

· Говори, а не спрашивай

· Паттерн facade

· Blob

— РЕГИСТРАЦИЯ

| Введение | |

| Пример с базовым Exception | |

| Два исключения | |

| except Error as e:: Печать текста ошибки | |

| else | |

| finally | |

| raise | |

| Пример 2 | |

| Пример 3 | |

| Исключения, которые не нужно обрабатывать | |

| Список исключений | |

| Разбор примеров: IndexError, ValueError, KeyError | |

| Похожие статьи |

Введение

Если в коде есть ошибка, которую видит интерпретатор поднимается исключение, создается так называемый

Exception Object, выполнение останавливается, в терминале

показывается Traceback.

В английском языке используется словосочетание Raise Exception

Исключение, которое не было предусмотрено разработчиком называется необработанным (Unhandled Exception)

Такое поведение не всегда является оптимальным. Не все ошибки дожны останавливать работу кода.

Возможно, где-то разработчик ожидает появление ошибок и их можно обработать по-другому.

try и except нужны прежде всего для того, чтобы код правильно реагировал на возможные ошибки и продолжал выполняться

там, где появление ошибки некритично.

Исключение, которое предусмотрено в коде называется обработанным (Handled)

Блок try except имеет следующий синтаксис

try:

pass

except Exception:

pass

else:

pass

finally:

pass

В этой статье я создал файл

try_except.py

куда копирую код из примеров.

Пример

Попробуем открыть несуществующий файл и воспользоваться базовым Exception

try:

f = open(‘missing.txt’)

except Exception:

print(‘ERR: File not found’)

python try_except.py

ERR: No missing.txt file found

Ошибка поймана, видно наше сообщение а не Traceback

Проверим, что когда файл существует всё хорошо

try:

f = open(‘existing.txt’)

except Exception:

print(‘ERR: File not found’)

python try_except.py

Пустота означает успех

Два исключения

Если ошибок больше одной нужны дополнительные исключения. Попробуем открыть существующий файл, и после этого

добавить ошибку.

try:

f = open(‘existing.txt’)

x = bad_value

except Exception:

print(‘ERR: File not found’)

python try_except.py

ERR: File not found

Файл открылся, но так как в следующей строке ошибка — в терминале появилось вводящее в заблуждение сообщение.

Проблема не в том, что «File not found» а в том, что bad_value нигде не определёно.

Избежать сбивающих с толку сообщений можно указав тип ожидаемой ошибки. В данном примере это FileNotFoundError

try:

# expected exception

f = open(‘existing.txt’)

# unexpected exception should result in Traceback

x = bad_value

except FileNotFoundError:

print(‘ERR: File not found’)

python try_except.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File «/home/andrei/python/try_except2.py», line 5, in <module>

x = bad_value

NameError: name ‘bad_value’ is not defined

Вторая ошибка не поймана поэтому показан Traceback

Поймать обе ошибки можно добавив второй Exception

try:

# expected exception should be caught by FileNotFoundError

f = open(‘missing.txt’)

# unexpected exception should be caught by Exception

x = bad_value

except FileNotFoundError:

print(‘ERR: File not found’)

except Exception:

print(‘ERR: Something unexpected went wrong’)

python try_except.py

ERR: File not found

ERR: Something unexpected went wrong

Печать текста ошибки

Вместо своего текста можно выводить текст ошибки. Попробуем с существующим файлом — должна быть одна пойманная ошибка.

try:

# expected exception should be caught by FileNotFoundError

f = open(‘existing.txt’)

# unexpected exception should be caught by Exception

x = bad_value

except FileNotFoundError as e:

print(e)

except Exception as e:

print(e)

python try_except.py

name ‘bad_value’ is not defined

Теперь попытаемся открыть несуществующий файл — должно быть две пойманные ошибки.

try:

# expected exception should be caught by FileNotFoundError

f = open(‘missing.txt’)

# unexpected exception should be caught by Exception

x = bad_value

except FileNotFoundError as e:

print(e)

except Exception as e:

print(e)

python try_except.py

name ‘bad_value’ is not defined

[Errno 2] No such file or directory: ‘missing.txt’

else

Блок else будет выполнен если исключений не будет поймано.

Попробуем открыть существующий файл

existing.txt

в котором есть строка

www.heihei.ru

try:

f = open(‘existing.txt’)

except FileNotFoundError as e:

print(e)

except Exception as e:

print(e)

else:

print(f.read())

f.close()

python try_except.py

www.heihei.ru

Если попробовать открыть несуществующий файл

missing.txt

то исключение обрабатывается, а код из блока else не выполняется.

[Errno 2] No such file or directory: ‘missing.txt’

finally

Блок finally будет выполнен независимо от того, поймано исключение или нет

try:

f = open(‘existing.txt’)

except FileNotFoundError as e:

print(e)

except Exception as e:

print(e)

else:

print(f.read())

f.close()

finally:

print(«Finally!»)

www.heihei.ru

Finally!

А если попытаться открыть несуществующий

missing.txt

[Errno 2] No such file or directory: ‘missing.txt’

Finally!

Когда нужно применять finally:

Рассмотрим скрипт, который вносит какие-то изменения в систему.

Затем он пытается что-то сделать. В конце возвращает

систему в исходное состояние.

Если ошибка случится в середине скрипта — он уже не сможет вернуть систему в исходное состояние.

Но если вынести возврат к исходному состоянию в блок finally он сработает даже при ошибке

в предыдущем блоке.

import os

def make_at(path, dir_name):

original_path = os.getcwd()

os.chdir(path)

os.mkdir(dir_name)

os.chdir(original_path)

Этот скрипт не вернётся в исходную директорию при ошибке в os.mkdir(dir_name)

А у скрипта ниже такой проблемы нет

def make_at(path, dir_name):

original_path = os.getcwd()

os.chdir(path)

try:

os.mkdir(dir_name)

finally:

os.chdir(original_path)

Не лишнима будет добавить обработку и вывод исключения

import os

import sys

def make_at(path, dir_name):

original_path = os.getcwd()

os.chdir(path)

try:

os.mkdir(dir_name)

except OSError as e:

print(e, file=sys.stderr)

raise

finally:

os.chdir(original_path)

По умолчанию print() выводит в sys.stdout, но в случае ислючений логичнее выводить в sys.stderr

raise

Можно вызывать исключения вручную в любом месте кода с помощью

raise.

try:

f = open(‘outdated.txt’)

if f.name == ‘outdated.txt’:

raise Exception

except FileNotFoundError as e:

print(e)

except Exception as e:

print(‘File is outdated!’)

else:

print(f.read())

f.close()

finally:

print(«Finally!»)

python try_except.py

File is outdated!

Finally!

raise

можно использовать для перевызова исключения, например, чтобы уйти от использования кодов ошибок.

Для этого достаточно вызвать raise без аргументов — поднимется текущее исключение.

Пример 2

Рассмотрим функцию, которая принимает числа прописью и возвращает цифрами

DIGIT_MAP = {

‘zero’: ‘0’,

‘one’: ‘1’,

‘two’: ‘2’,

‘three’: ‘3’,

‘four’: ‘4’,

‘five’: ‘5’,

‘six’: ‘6’,

‘seven’: ‘7’,

‘eight’: ‘8’,

‘nine’: ‘9’,

}

def convert(s):

number = »

for token in s:

number += DIGIT_MAP[token]

x = int(number)

return x

python

>>> from exc1 import convert

>>> convert(«one three three seven».split())

1337

Теперь передадим аргумент, который не предусмотрен в словаре

>>> convert(«something unseen«.split())

Traceback (most recent call last):

File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module>

File «/home/andrei/python/exc1.py», line 17, in convert

number &plu= DIGIT_MAP[token]

KeyError: ‘something’

KeyError — это тип Exception объекта. Полный список можно изучить в конце статьи.

Исключение прошло следующий путь:

REPL → convert() → DIGIT_MAP(«something») → KeyError

Обработать это исключение можно внеся изменения в функцию convert

convert(s):

try:

number = »

for token in s:

number += DIGIT_MAP[token]

x = int(number)

print(«Conversion succeeded! x = «, x)

except KeyError:

print(«Conversion failed!»)

x = —1

return x

>>> from exc1 import convert

>>> convert(«one nine six one».split())

Conversion succeeded! x = 1961

1961

>>> convert(«something unseen».split())

Conversion failed!

-1

Эта обработка не спасает если передать int вместо итерируемого объекта

>>> convert(2022)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module>

File «/home/andrei/python/exc1.py», line 17, in convert

for token in s:

TypeError: ‘int’ object is not iterable

Нужно добавить обработку TypeError

…

except KeyError:

print(«Conversion failed!»)

x = —1

except TypeError:

print(«Conversion failed!»)

x = —1

return x

>>> from exc1 import convert

>>> convert(«2022».split())

Conversion failed!

-1

Избавимся от повторов, удалив принты, объединив два исключения в кортеж и вынесем присваивание значения x

из try блока.

Также добавим

докстринг

с описанием функции.

def convert(s):

«»»Convert a string to an integer.»»»

x = —1

try:

number = »

for token in s:

number += DIGIT_MAP[token]

x = int(number)

except (KeyError, TypeError):

pass

return x

>>> from exc4 import convert

>>> convert(«one nine six one».split())

1961

>>> convert(«bad nine six one».split())

-1

>>> convert(2022)

-1

Ошибки обрабатываются, но без принтов, процесс не очень информативен.

Грамотно показать текст сообщений об ошибках можно импортировав sys и изменив функцию

import sys

DIGIT_MAP = {

‘zero’: ‘0’,

‘one’: ‘1’,

‘two’: ‘2’,

‘three’: ‘3’,

‘four’: ‘4’,

‘five’: ‘5’,

‘six’: ‘6’,

‘seven’: ‘7’,

‘eight’: ‘8’,

‘nine’: ‘9’,

}

def convert(s):

«»»Convert a string to an integer.»»»

try:

number = »

for token in s:

number += DIGIT_MAP[token]

return(int(number))

except (KeyError, TypeError) as e:

print(f«Conversion error: {e!r}», file=sys.stderr)

return —1

>>> from exc1 import convert

>>> convert(2022)

Conversion error: TypeError(«‘int’ object is not iterable»)

-1

>>> convert(«one nine six one».split())

1961

>>> convert(«bad nine six one».split())

Conversion error: KeyError(‘bad’)

Ошибки обрабатываются и их текст виден в терминале.

С помощью

!r

выводится

repr()

ошибки

raise вместо кода ошибки

В предыдущем примере мы полагались на возвращение числа -1 в качестве кода ошибки.

Добавим к коду примера функцию string_log() и поработаем с ней

def string_log(s):

v = convert(s)

return log(v)

>>> from exc1 import string_log

>>> string_log(«one two eight».split())

4.852030263919617

>>> string_log(«bad one two».split())

Conversion error: KeyError(‘bad’)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module>

File «/home/andrei/exc1.py», line 32, in string_log

return log(v)

ValueError: math domain error

convert() вернул -1 а string_log попробовал его обработать и не смог.

Можно заменить return -1 на raise. Это считается более правильным подходом в Python

def convert(s):

«»»Convert a string to an integer.»»»

try:

number = »

for token in s:

number += DIGIT_MAP[token]

return(int(number))

except (KeyError, TypeError) as e:

print(f«Conversion error: {e!r}», file=sys.stderr)

raise

>>> from exc7 import string_log

>>> string_log(«one zero».split())

2.302585092994046

>>> string_log(«bad one two».split())

Conversion error: KeyError(‘bad’)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module>

File «/home/andrei/exc7.py», line 31, in string_log

v = convert(s)

File «/home/andrei/exc7.py», line 23, in convert

number += DIGIT_MAP[token]

KeyError: ‘bad’

Пример 3

Рассмотрим алгоритм по поиску квадратного корня

def sqrt(x):

«»»Compute square roots using the method

of Heron of Alexandria.

Args:

x: The number for which the square root

is to be computed.

Returns:

The square root of x.

«»»

guess = x

i = 0

while guess * guess != x and i < 20:

guess = (guess + x / guess) / 2.0

i += 1

return guess

def main():

print(sqrt(9))

print(sqrt(2))

if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

main()

python sqrt_ex.py

3.0

1.414213562373095

При попытке вычислить корень от -1 получим ошибку

def main():

print(sqrt(9))

print(sqrt(2))

print(sqrt(-1))

python sqrt_ex.py

3.0

1.414213562373095

Traceback (most recent call last):

File «/home/andrei/sqrt_ex.py», line 26, in <module>

main()

File «/home/andrei/sqrt_ex.py», line 23, in main

print(sqrt(-1))

File «/home/andrei/sqrt_ex.py», line 16, in sqrt

guess = (guess + x / guess) / 2.0

ZeroDivisionError: float division by zero

В строке

guess = (guess + x / guess) / 2.0

Происходит деление на ноль

Обработать можно следующим образом:

def main():

try:

print(sqrt(9))

print(sqrt(2))

print(sqrt(-1))

except ZeroDivisionError:

print(«Cannot compute square root «

«of a negative number.»)

print(«Program execution continues «

«normally here.»)

Обратите внимание на то, что в try помещены все вызовы функции

python sqrt_ex.py

3.0

1.414213562373095

Cannot compute square root of a negative number.

Program execution continues normally here.

Если пытаться делить на ноль несколько раз — поднимется одно исключение и всё что находится в блоке

try после выполняться не будет

def main():

try:

print(sqrt(9))

print(sqrt(-1))

print(sqrt(2))

print(sqrt(-1))

python sqrt_ex.py

3.0

Cannot compute square root of a negative number.

Program execution continues normally here.

Каждую попытку вычислить корень из -1 придётся обрабатывать отдельно. Это кажется неудобным, но

в этом и заключается смысл — каждое место где вы ждёте ислючение нужно помещать в свой

try except блок.

Можно обработать исключение так:

try:

while guess * guess != x and i < 20:

guess = (guess + x / guess) / 2.0

i += 1

except ZeroDivisionError:

raise ValueError()

return guess

def main():

print(sqrt(9))

print(sqrt(-1))

python sqrt_ex.py

3.0

Traceback (most recent call last):

File «/home/andrei/sqrt_ex3.py», line 17, in sqrt

guess = (guess + x / guess) / 2.0

ZeroDivisionError: float division by zero

During handling of the above exception, another exception occurred:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File «/home/andrei/sqrt_ex3.py», line 30, in <module>

main()

File «/home/andrei/sqrt_ex3.py», line 25, in main

print(sqrt(-1))

File «/home/andrei/sqrt_ex3.py», line 20, in sqrt

raise ValueError()

ValueError

Гораздо логичнее поднимать исключение сразу при получении аргумента

def sqrt(x):

«»»Compute square roots using the method

of Heron of Alexandria.

Args:

x: The number for which the square root

is to be computed.

Returns:

The square root of x.

Raises:

ValueError: If x is negative

«»»

if x < 0:

raise ValueError(

«Cannot compute square root of «

f«negative number {x}»)

guess = x

i = 0

while guess * guess != x and i < 20:

guess = (guess + x / guess) / 2.0

i += 1

return guess

def main():

print(sqrt(9))

print(sqrt(-1))

print(sqrt(2))

print(sqrt(-1))

if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

main()

python sqrt_ex.py

3.0

Traceback (most recent call last):

File «/home/avorotyn/python/lessons/pluralsight/core_python_getting_started/chapter8/sqrt_ex4.py», line 35, in <module>

main()

File «/home/avorotyn/python/lessons/pluralsight/core_python_getting_started/chapter8/sqrt_ex4.py», line 30, in main

print(sqrt(-1))

File «/home/avorotyn/python/lessons/pluralsight/core_python_getting_started/chapter8/sqrt_ex4.py», line 17, in sqrt

raise ValueError(

ValueError: Cannot compute square root of negative number -1

Пока получилось не очень — виден Traceback

Убрать Traceback можно добавив обработку ValueError в вызов функций

import sys

def sqrt(x):

«»»Compute square roots using the method

of Heron of Alexandria.

Args:

x: The number for which the square root

is to be computed.

Returns:

The square root of x.

Raises:

ValueError: If x is negative

«»»

if x < 0:

raise ValueError(

«Cannot compute square root of «

f«negative number {x}»)

guess = x

i = 0

while guess * guess != x and i < 20:

guess = (guess + x / guess) / 2.0

i += 1

return guess

def main():

try:

print(sqrt(9))

print(sqrt(2))

print(sqrt(-1))

print(«This is never printed»)

except ValueError as e:

print(e, file=sys.stderr)

print(«Program execution continues normally here.»)

if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

main()

python sqrt_ex.py

3.0

1.414213562373095

Cannot compute square root of negative number -1

Program execution continues normally here.

Исключения, которые не нужно обрабатывать

IndentationError, SyntaxError, NameError нужно исправлять в коде а не пытаться обработать.

Важно помнить, что использовать обработку исключений для замалчивания ошибок программиста недопустимо.

Список исключений

Список встроенных в Python исключений

Существуют следующие типы объектов Exception

BaseException

+— SystemExit

+— KeyboardInterrupt

+— GeneratorExit

+— Exception

+— StopIteration

+— StopAsyncIteration

+— ArithmeticError

| +— FloatingPointError

| +— OverflowError

| +— ZeroDivisionError

+— AssertionError

+— AttributeError

+— BufferError

+— EOFError

+— ImportError

| +— ModuleNotFoundError

+— LookupError

| +— IndexError

| +— KeyError

+— MemoryError

+— NameError

| +— UnboundLocalError

+— OSError

| +— BlockingIOError

| +— ChildProcessError

| +— ConnectionError

| | +— BrokenPipeError

| | +— ConnectionAbortedError

| | +— ConnectionRefusedError

| | +— ConnectionResetError

| +— FileExistsError

| +— FileNotFoundError

| +— InterruptedError

| +— IsADirectoryError

| +— NotADirectoryError

| +— PermissionError

| +— ProcessLookupError

| +— TimeoutError

+— ReferenceError

+— RuntimeError

| +— NotImplementedError

| +— RecursionError

+— SyntaxError

| +— IndentationError

| +— TabError

+— SystemError

+— TypeError

+— ValueError

| +— UnicodeError

| +— UnicodeDecodeError

| +— UnicodeEncodeError

| +— UnicodeTranslateError

+— Warning

+— DeprecationWarning

+— PendingDeprecationWarning

+— RuntimeWarning

+— SyntaxWarning

+— UserWarning

+— FutureWarning

+— ImportWarning

+— UnicodeWarning

+— BytesWarning

+— EncodingWarning

+— ResourceWarning

IndexError

Объекты, которые поддерживают

протокол

Sequence должны поднимать исключение IndexError при использовании несуществующего индекса.

IndexError как и

KeyError

относится к ошибкам поиска LookupError

Пример

>>> a = [0, 1, 2]

>>> a[3]

Traceback (most recent call last):

File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module>

IndexError: list index out of range

ValueError

ValueError поднимается когда объект правильного типа, но содержит неправильное значение

>>> int(«text»)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module>

ValueError: invalid literal for int() with base 10: ‘text’

KeyError

KeyError поднимается когда поиск по ключам не даёт результата

>>> sites = dict(urn=1, heihei=2, eth1=3)

>>> sites[«topbicycle»]

Traceback (most recent call last):

File «<stdin>», line 1, in <module>

KeyError: ‘topbicycle’

TypeError

TypeError поднимается когда для успешного выполнения операции нужен объект

определённого типа, а предоставлен другой тип.

pi = 3.1415

text = «Pi is approximately « + pi

python str_ex.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File «str_ex.py», line 3, in <module>

text = «Pi is approximately » + pi

TypeError: can only concatenate str (not «float») to str

Пример из статьи

str()

SyntaxError

SyntaxError поднимается когда допущена ошибка в синтаксисе языка, например, использован

несуществующий оператор.

Python 3.8.10 (default, Nov 14 2022, 12:59:47)

[GCC 9.4.0] on linux

Type «help», «copyright», «credits» or «license» for more information.

>>>

>>>

>>> 0 <> 0

File «<stdin>», line 1

0 <> 0

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

Пример из статьи

__future__

| Python | |

| Интерактивный режим | |

| str: строки | |

| : перенос строки | |

| Списки [] | |

| if, elif, else | |

| Циклы | |

| Функции | |

| Пакеты | |

| *args **kwargs | |

| ООП | |

| enum | |

| Опеределить тип переменной Python | |

| Тестирование с помощью Python | |

| Работа с REST API на Python | |

| Файлы: записать, прочитать, дописать, контекстный менеджер… | |

| Скачать файл по сети | |

| SQLite3: работа с БД | |

| datetime: Дата и время в Python | |

| json.dumps | |

| Selenium + Python | |

| Сложности при работе с Python | |

| DJANGO | |

| Flask | |

| Скрипт для ZPL принтера | |

| socket :Python Sockets | |

| Виртуальное окружение | |

| subprocess: выполнение bash команд из Python | |

| multiprocessing: несколько процессов одновременно | |

| psutil: cистемные ресурсы | |

| sys.argv: аргументы командной строки | |

| PyCharm: IDE | |

| pydantic: валидация данных | |

| paramiko: SSH из Python | |

| enumerate | |

| logging: запись в лог | |

| Обучение программированию на Python |

Improve Article

Save Article

Improve Article

Save Article

Errors are the problems in a program due to which the program will stop the execution. On the other hand, exceptions are raised when some internal events occur which changes the normal flow of the program.

Two types of Error occurs in python.

- Syntax errors

- Logical errors (Exceptions)

Syntax errors

When the proper syntax of the language is not followed then a syntax error is thrown.

Example

Python3

amount = 10000

if(amount>2999)

print("You are eligible to purchase Dsa Self Paced")

Output:

It returns a syntax error message because after the if statement a colon: is missing. We can fix this by writing the correct syntax.

logical errors(Exception)

When in the runtime an error that occurs after passing the syntax test is called exception or logical type. For example, when we divide any number by zero then the ZeroDivisionError exception is raised, or when we import a module that does not exist then ImportError is raised.

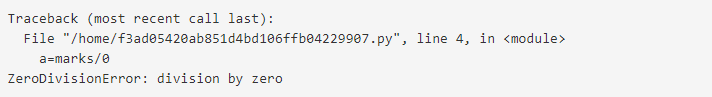

Example 1:

Python3

marks = 10000

a = marks / 0

print(a)

Output:

In the above example the ZeroDivisionError as we are trying to divide a number by 0.

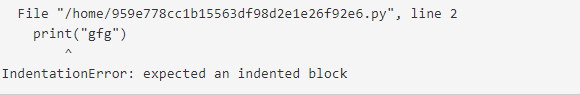

Example 2: When indentation is not correct.

Python3

Output:

Some of the common built-in exceptions are other than above mention exceptions are:

| Exception | Description |

|---|---|

| IndexError | When the wrong index of a list is retrieved. |

| AssertionError | It occurs when the assert statement fails |

| AttributeError | It occurs when an attribute assignment is failed. |

| ImportError | It occurs when an imported module is not found. |

| KeyError | It occurs when the key of the dictionary is not found. |

| NameError | It occurs when the variable is not defined. |

| MemoryError | It occurs when a program runs out of memory. |