In this article, let us learn about printing error messages from Exceptions with the help of 5 specifically chosen examples.

I have divided this article into 2 major sections

- Printing custom error messages and

- Printing a specific part of the default error message. By “default error message“, I mean the error message that you typically get in the command line if you did not catch a given exception)

Depending on which of the 2 options above you are looking for, you can jump to the respective section of the article using the table of content below.

So, let’s begin!

Printing Custom Error messages

There are 3 ways to print custom error messages in Python. Let us start with the simplest of the 3, which is using a print() statement.

Option#1: Using a simple print() statement

The first and easiest option is to print error messages using a simple print() statement as shown in the example below.

try:

#Some Problematic code that can produce Exceptions

x = 5/0

except Exception as e:

print('A problem has occurred from the Problematic code: ', e)Running this code will give the output below.

A problem has occurred from the Problematic code: division by zeroHere the line “x = 5/0″ in Example 1 above raised a “ZeroDivisionError” which was caught by our except clause and the print() statement printed the default error message which is “division by zero” to the standard output.

One thing to note here is the line “except Exception as e“. This line of code’s function is to catch all possible exceptions, whichever occurs first as an “Exception” object. This object is stored in the variable “e” (line 4), which returns the string ‘division by zero‘ when used with the print() statement (line 5).

To summarize if you wish to print out the default error message along with a custom message use Option#1.

This is the simplest way to print error messages in python. But this option of putting your custom messages into print statements might not work in cases where you might be handling a list of exceptions using a single except clause. If you are not exactly sure how to catch a list of exceptions using a single except clause, I suggest reading my other article in the link below.

Python: 3 Ways to Catch Multiple Exceptions in a single “except” clause

There I have explained the 3 ways through which you can catch a list of exceptions along with tips on when is the right situation to catch each of these exceptions.

Now that we have learned how to print the default string which comes with an exception object, let us next learn how to customize the message that e carried (the string ‘division by zero‘) and replace that with our own custom error message.

Option#2: Using Custom Exception classes to get customized error messages

In Python, you can define your own custom exception classes by inheriting from another Exception class as shown in the code below.

class MyOwnException(Exception):

def __str__(self):

return 'My Own Exception has occurred'

def __repr__(self):

return str(type(self))

try:

raise MyOwnException

except MyOwnException as e:

print(e)

print(repr(e))How to choose the exception class to inherit from?

In the above example, I have inherited from the Exception class in python, but the recommended practice is to choose a class that closely resembles your use-case.

For example, say you are trying to work with a string type object and you are given a list type object instead, here you should inherit your custom exception from TypeError since this Exception type closely resembles your use case which is “the variable is not of expected type”.

If you are looking for getting an appropriate Exception class to inherit from, I recommend having a look at all the built-in exceptions from the official python page here. For the sake of keeping this example simple, I have chosen the higher-level exception type named “Exception” class to inherit from.

In the code below, we are collecting values from the user and to tell the user that there is an error in the value entered we are using the ValueError class.

class EnteredGarbageError(ValueError):

def __str__(self):

return 'You did not select an option provided!'

try:

options = ['A', 'B', 'C']

x = input('Type A or B or C: ')

if x not in options:

raise EnteredGarbageError

else:

print ('You have chosen: ', x)

except EnteredGarbageError as err:

print(err)Now that we understand how to choose a class to inherit from, let us next have a look at how to customize the default error messages that these classes return.

How to customize the error message in our custom exception class?

To help us achieve our purpose here which is to print some custom error messages, all objects in python come with 2 methods named __str__ and __repr__. This is pronounced “dunder-str” and “dunder-repr” where “dunder” is short for “double underscore”.

Dunder-str method:

The method __str__ returns a string and this is what the built-in print() function calls whenever we pass it an object to print.

print(object1)In the line above, python will call the __str__ method of the object and prints out the string returned by that method.

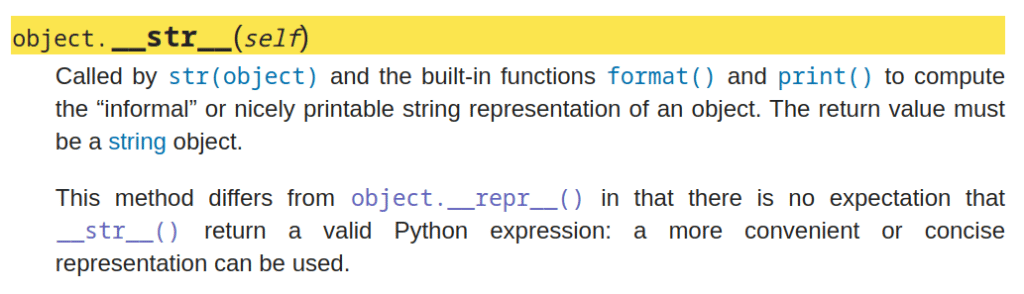

Let us have a look at what python’s official documentation over at python.org has to say about the str method.

In simpler words, the str method returns a human-readable string for logging purposes, and when this information is passed to the built-in function print(), the string it returns gets printed.

So since our implementation of str returns the string “My Own Exception has occurred” this string got printed on the first line of the exception message.

Dunder-repr method:

__repr__ is another method available in all objects in python.

Where it differs from the dunder-str method is the fact that while the __str__ is used for getting a “friendly message”, the __repr__ method is used for getting, a more of a, “formal message”. You can think of str as a text you got from your friends and repr as a notice you got from a legal representative!

The below screenshot from python’s official documentation explains the use of __repr__ method.

Again, in simpler words, repr is typically used to print some “formal” or “official” information about an object in Python

In our Example 2 above, the repr method returned the class name using the built-in type() function.

Next, let us see another variation where we can print different error messages using a single Exception class without making a custom class.

Option#3: Custom Error messages from the raise statement

try:

raise Exception('I wish to print this message')

except Exception as error:

print(error)Lucky for us, python has made this process incredibly simple! Just pass in the message as an argument to the type of exception you wish to raise and this will print that custom message instead!

In the above code, we are throwing an exception of type “Exception” by calling its constructor and giving the custom message as an argument, which then overrides the default __str__ method to return the string passed in.

If you wish to learn more about raise statement, I suggest reading my other article in the link below

Python: Manually throw/raise an Exception using the “raise” statement

where I have explained 3 ways you can use the raise statement in python and when to use each.

But when to use option 2 and when to use option 3?

On the surface, Option#3 of passing in the custom message may look like it made option#2 of using custom classes useless. But the main reason to use Option#2 is the fact that Option#2 can be used to override more than just the __str__ method.

Let’s next move on to section 2 of this article and look at how to choose a specific part of the default error message (the error printed on the console when you don’t catch an exception) and use that to make our own error messages

Choosing Parts of Default Error Messages to print

To understand what I mean by “Default Error Message” let us see an example

raise ValueError("This is an ValueError")This line when run, will print the following error message

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<ipython-input-24-57127e33a735>", line 1, in <module>

raise ValueError("This is an ValueError")

ValueError: This is an ValueErrorThis error message contains 3 Parts

- Exception Type (ValueError)

- Error message (This is an ValueError)

- and the stack trace (the 1st few lines showing us where exactly in the program the exception has occurred)

The information needed

- to extract and use each of the individual pieces of information listed above and

- when to use what piece of information

is already covered with the help of several examples in my previous article in the link below

Python Exceptions: Getting and Handling Error Messages as strings.

And with that I will end this article!

If you are looking for another interesting read, try the article in the link below.

Exceptions in Python: Everything You Need To Know!

The above article covers all the basics of Exception handling in Python like

- when and how to ignore exceptions

- when and how to retry the problematic code that produced the exception and

- when and how to log the errors

I hope you enjoyed reading this article and got some value from it.

Feel free to share it with your friends and colleagues!

Sometimes, a Python script comes across an unusual situation that it can’t handle, and the program gets terminated or crashed. In this article, we’ll learn How to catch and print the exception messages in python. If you want to learn more about Python Programming, visit Python Tutorials.

The most common method to catch and print the exception message in Python is by using except and try statement. You can also save its error message using this method. Another method is to use logger.exception() which produces an error message as well as the log trace, which contains information such as the code line number at which the exception occurred and the time the exception occurred.

The most common example is a “FileNotFoundError” when you’re importing a file, but it doesn’t exist. Similarly, dividing a number by zero gives a “ZeroDivisionError” and displays a system-generated error message. All these run-time errors are known as exceptions. These exceptions should be caught and reported to prevent the program from being terminated.

In Python, exceptions are handled with the (try… except) statement. The statements which handle the exceptions are placed in the except block whereas the try clause includes the expressions which can raise an exception. Consider an example in which you take a list of integers as input from the user.

Example

# Creating an empty list

new_list =[]

n = int(input("Enter number of elements : "))

for i in range(n):

item = int(input())

# Add the item in the list

new_list.append(item)

print(new_list)

The program shown above takes integers as input and creates a list of these integers. If the user enters any character, the program will crash and generate the following output.

Output:

Enter number of elements : 7

23

45

34

65

2a

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ValueError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-1-ac783af2c9a3> in <module>()

3 n = int(input("Enter number of elements : "))

4 for i in range(n):

----> 5 item = int(input())

6 # Add the item in the list

7 new_list.append(item)

ValueError: invalid literal for int() with base 10: '2a'USE except and try statement to CATCH ANd print the EXCEPTION AND SAVE ITS ERROR MESSAGEs

The first method to catch and print the exception messages in python is by using except and try statement. If the user enters anything except the integer, we want the program to skip that input and move to the next value. In this way, our program will not crash and will catch and print the exception message. This can be done using try and except statements. Inside the try clause, we’ll take input from the user and append it to “new_list” variable. If the user has entered any input except integers mistakenly, the except block will print “Invalid entry” and move towards the next value. In this way, the program continues to run and skip the invalid entries.

# Creating an empty list

new_list =[]

n = int(input("Enter number of elements : "))

for i in range(n):

try:

item = int(input())

# Add the item in the list

new_list.append(item)

except:

print("Invalid Input!")

print("Next entry.")

print("The list entered by user is: ", new_list)

Output:

Enter number of elements : 7

65

43

23

4df

Invalid Input!

Next entry.

76

54

90

The list entered by user is: [65, 43, 23, 76, 54, 90]There are various methods to catch and report these exceptions using try and except block. Some of them are listed below along with examples.

Catching and reporting/Print exceptions messages in python

This is the second method to catch and print the exception messages in python. With the help of the print function, you can capture, get and print an exception message in Python. Consider an example in which you have a list containing elements of different data types. You want to divide all the integers by any number. This number on division with the string datatypes will raise “TypeError” and the program will terminate if the exceptions are not handled. The example shown below describes how to handle this problem by capturing the exception using the try-except block and reporting it using the print command.

EXAMPLE 3:

list_arr=[76,65,87,"5f","7k",78,69]

for elem in list_arr:

try:

print("Result: ", elem/9)

except Exception as e:

print("Exception occurred for value '"+ elem + "': "+ repr(e))

Output:

Result: 8.444444444444445

Result: 7.222222222222222

Result: 9.666666666666666

Exception occurred for value '5f': TypeError("unsupported operand type(s) for /: 'str' and 'int'")

Exception occurred for value '7k': TypeError("unsupported operand type(s) for /: 'str' and 'int'")

Result: 8.666666666666666

Result: 7.666666666666667using try and logger.exception to print an error message

Another method is to use logger.exception() which produces an error message as well as the log trace, which contains information such as the code line number at which the exception occurred and the time the exception occurred. This logger.exception() method should be included within the except statement; otherwise, it will not function properly.

import logging

logger=logging.getLogger()

num1=int(input("Enter the number 1:"))

num2=int(input("Enter the number 2:"))

try:

print("Result: ", num1/num2)

except Exception as e:

logger.exception("Exception Occured while code Execution: "+ str(e))

Output:

Enter the number 1:82

Enter the number 2:4

Result: 20.5Suppose if a user enters 0 in the 2nd number, then this will raise a “ZeroDivisionError” as shown below.

Enter the number 1:9

Enter the number 2:0

Exception Occured while code Execution: division by zero

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<ipython-input-27-00694f615c2f>", line 11, in <module>

print("Result: ", num1/num2)

ZeroDivisionError: division by zeroSimilarly, if you’ve two lists consisting of integers and you want to create a list consisting of results obtained by dividing list1 with list2. Suppose you don’t know whether the two lists consist of integers or not.

EXAMPLE 5:

import logging

logger=logging.getLogger()

list1=[45, 32, 76, 43, 0, 76]

list2=[24, "world", 5, 0, 4, 6]

Result=[]

for i in range(len(list1)):

try:

Result.append(list1[i]/list2[i])

except Exception as e:

logger.exception("Exception Occured while code Execution: "+ str(e))

print(Result)

Output:

In this example, “world” in the 2nd index of list2 is a string and 32 on division with a string would raise an exception. But, we have handled this exception using try and except block. The logger.exception() command prints the error along with the line at which it occurred and then moves toward the next index. Similarly, all the values are computed and stored in another list which is then displayed at the end of the code.

Exception Occured while code Execution: unsupported operand type(s) for /: 'int' and 'str'

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<ipython-input-1-5a40f7f6c621>", line 8, in <module>

Result.append(list1[i]/list2[i])

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for /: 'int' and 'str'

Exception Occured while code Execution: division by zero

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<ipython-input-1-5a40f7f6c621>", line 8, in <module>

Result.append(list1[i]/list2[i])

ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

[1.875, 15.2, 0.0, 12.666666666666666]The logger module has another function “logger.error()” which returns only an error message. The following example demonstrates how the logger.error() function may be used to capture exception messages in Python. In this example, we have just replaced logger.exception in the above example with logger.error() function

EXAMPLE 6:

import logging

logger=logging.getLogger()

list1=[45, 32,76,43,0, 76]

list2=[24, "world", 5, 0, 4, 6]

Result=[]

for i in range(len(list1)):

try:

Result.append(list1[i]/list2[i])

except Exception as e:

logger.error("Exception Occured while code Execution: "+ str(e))

print(Result)

Output:

Exception Occured while code Execution: unsupported operand type(s) for /: 'int' and 'str'

Exception Occured while code Execution: division by zero

[1.875, 15.2, 0.0, 12.666666666666666]Catching and printing Specific Exceptions messages

The previous section was all about how to catch and print exceptions. But, how will you catch a specific exception such as Valueerror, ZeroDivisionError, ImportError, etc? There are two cases if you want to catch one specific exception or multiple specific exceptions. The following example shows how to catch a specific exception.

EXAMPLE 7:

a = 'hello'

b = 4

try:

print(a + b)

except TypeError as typo:

print(typo)

Output:

can only concatenate str (not "int") to strSimilarly, if you want to print the result of “a/b” also and the user enters 0 as an input in variable “b”, then the same example would not be able to deal with ZeroDivisionError. Therefore we have to use multiple Except clauses as shown below.

EXAMPLE 8:

a = 6

b = 0

try:

print(a + b)

print(a/b)

except TypeError as typo:

print(typo)

except ZeroDivisionError as zer:

print(zer)

Output:

The same code is now able to handle multiple exceptions.

6

division by zeroTo summarize, all of the methods described above are effective and efficient. You may use any of the methods listed above to catch and print the exception messages in Python depending on your preferences and level of comfort with the method. If you’ve any queries regarding this article, please let us know in the comment section. Your feedback matters a lot to us.

Python comes with an extensive support of exceptions and exception handling. An exception event interrupts and, if uncaught, immediately terminates a running program. The most popular examples are the IndexError, ValueError, and TypeError.

An exception will immediately terminate your program. To avoid this, you can catch the exception with a try/except block around the code where you expect that a certain exception may occur. Here’s how you catch and print a given exception:

To catch and print an exception that occurred in a code snippet, wrap it in an indented try block, followed by the command "except Exception as e" that catches the exception and saves its error message in string variable e. You can now print the error message with "print(e)" or use it for further processing.

try:

# ... YOUR CODE HERE ... #

except Exception as e:

# ... PRINT THE ERROR MESSAGE ... #

print(e)

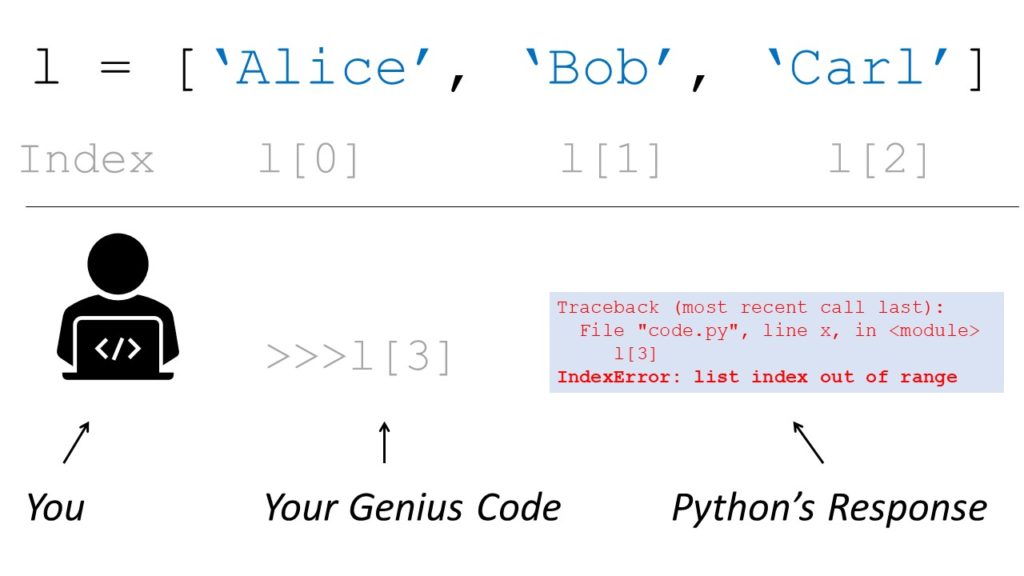

Example 1: Catch and Print IndexError

If you try to access the list element with index 100 but your lists consist only of three elements, Python will throw an IndexError telling you that the list index is out of range.

try:

lst = ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Carl']

print(lst[3])

except Exception as e:

print(e)

print('Am I executed?')

Your genius code attempts to access the fourth element in your list with index 3—that doesn’t exist!

Fortunately, you wrapped the code in a try/catch block and printed the exception. The program is not terminated. Thus, it executes the final print() statement after the exception has been caught and handled. This is the output of the previous code snippet.

list index out of range Am I executed?

🌍 Recommended Tutorial: How to Print an Error in Python?

Example 2: Catch and Print ValueError

The ValueError arises if you try to use wrong values in some functions. Here’s an example where the ValueError is raised because you tried to calculate the square root of a negative number:

import math

try:

a = math.sqrt(-2)

except Exception as e:

print(e)

print('Am I executed?')

The output shows that not only the error message but also the string 'Am I executed?' is printed.

math domain error Am I executed?

Example 3: Catch and Print TypeError

Python throws the TypeError object is not subscriptable if you use indexing with the square bracket notation on an object that is not indexable. This is the case if the object doesn’t define the __getitem__() method. Here’s how you can catch the error and print it to your shell:

try:

variable = None

print(variable[0])

except Exception as e:

print(e)

print('Am I executed?')

The output shows that not only the error message but also the string 'Am I executed?' is printed.

'NoneType' object is not subscriptable Am I executed?

I hope you’re now able to catch and print your error messages.

Summary

To catch and print an exception that occurred in a code snippet, wrap it in an indented try block, followed by the command "except Exception as e" that catches the exception and saves its error message in string variable e. You can now print the error message with "print(e)" or use it for further processing.

Where to Go From Here?

Enough theory. Let’s get some practice!

Coders get paid six figures and more because they can solve problems more effectively using machine intelligence and automation.

To become more successful in coding, solve more real problems for real people. That’s how you polish the skills you really need in practice. After all, what’s the use of learning theory that nobody ever needs?

You build high-value coding skills by working on practical coding projects!

Do you want to stop learning with toy projects and focus on practical code projects that earn you money and solve real problems for people?

🚀 If your answer is YES!, consider becoming a Python freelance developer! It’s the best way of approaching the task of improving your Python skills—even if you are a complete beginner.

If you just want to learn about the freelancing opportunity, feel free to watch my free webinar “How to Build Your High-Income Skill Python” and learn how I grew my coding business online and how you can, too—from the comfort of your own home.

Join the free webinar now!

Programmer Humor

Q: How do you tell an introverted computer scientist from an extroverted computer scientist?

A: An extroverted computer scientist looks at your shoes when he talks to you.While working as a researcher in distributed systems, Dr. Christian Mayer found his love for teaching computer science students.

To help students reach higher levels of Python success, he founded the programming education website Finxter.com. He’s author of the popular programming book Python One-Liners (NoStarch 2020), coauthor of the Coffee Break Python series of self-published books, computer science enthusiast, freelancer, and owner of one of the top 10 largest Python blogs worldwide.

His passions are writing, reading, and coding. But his greatest passion is to serve aspiring coders through Finxter and help them to boost their skills. You can join his free email academy here.

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Raising and Handling Python Exceptions

A Python program terminates as soon as it encounters an error. In Python, an error can be a syntax error or an exception. In this article, you will see what an exception is and how it differs from a syntax error. After that, you will learn about raising exceptions and making assertions. Then, you’ll finish with a demonstration of the try and except block.

Exceptions versus Syntax Errors

Syntax errors occur when the parser detects an incorrect statement. Observe the following example:

>>> print( 0 / 0 ))

File "<stdin>", line 1

print( 0 / 0 ))

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

The arrow indicates where the parser ran into the syntax error. In this example, there was one bracket too many. Remove it and run your code again:

>>> print( 0 / 0)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ZeroDivisionError: integer division or modulo by zero

This time, you ran into an exception error. This type of error occurs whenever syntactically correct Python code results in an error. The last line of the message indicated what type of exception error you ran into.

Instead of showing the message exception error, Python details what type of exception error was encountered. In this case, it was a ZeroDivisionError. Python comes with various built-in exceptions as well as the possibility to create self-defined exceptions.

Raising an Exception

We can use raise to throw an exception if a condition occurs. The statement can be complemented with a custom exception.

If you want to throw an error when a certain condition occurs using raise, you could go about it like this:

x = 10

if x > 5:

raise Exception('x should not exceed 5. The value of x was: {}'.format(x))

When you run this code, the output will be the following:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<input>", line 4, in <module>

Exception: x should not exceed 5. The value of x was: 10

The program comes to a halt and displays our exception to screen, offering clues about what went wrong.

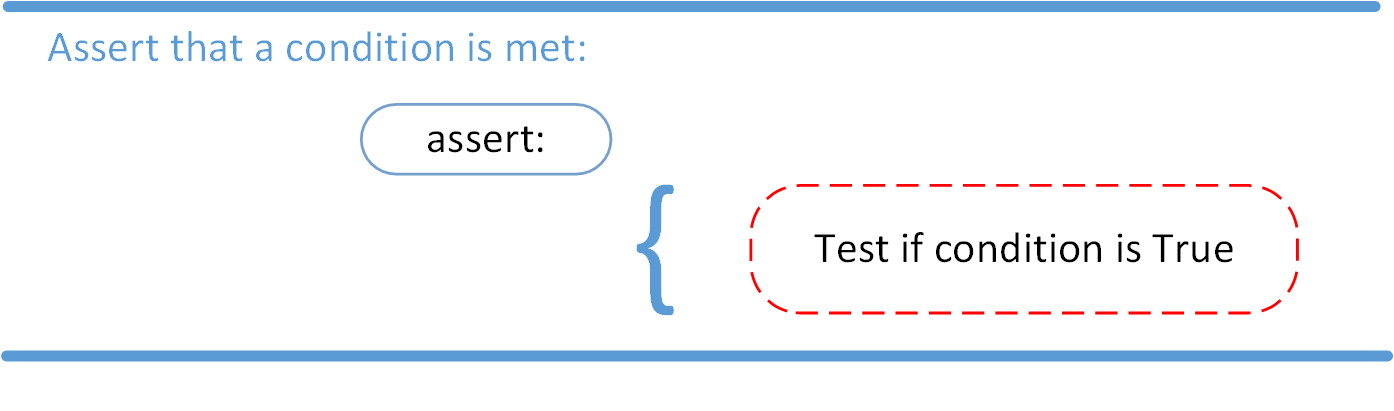

The AssertionError Exception

Instead of waiting for a program to crash midway, you can also start by making an assertion in Python. We assert that a certain condition is met. If this condition turns out to be True, then that is excellent! The program can continue. If the condition turns out to be False, you can have the program throw an AssertionError exception.

Have a look at the following example, where it is asserted that the code will be executed on a Linux system:

import sys

assert ('linux' in sys.platform), "This code runs on Linux only."

If you run this code on a Linux machine, the assertion passes. If you were to run this code on a Windows machine, the outcome of the assertion would be False and the result would be the following:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<input>", line 2, in <module>

AssertionError: This code runs on Linux only.

In this example, throwing an AssertionError exception is the last thing that the program will do. The program will come to halt and will not continue. What if that is not what you want?

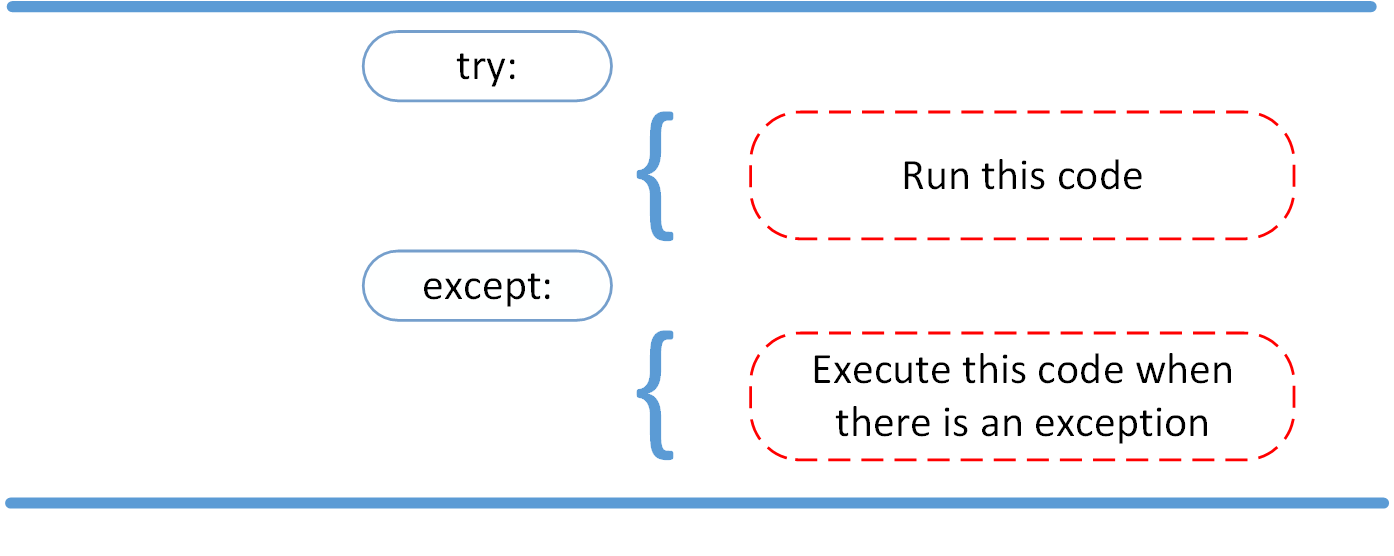

The try and except Block: Handling Exceptions

The try and except block in Python is used to catch and handle exceptions. Python executes code following the try statement as a “normal” part of the program. The code that follows the except statement is the program’s response to any exceptions in the preceding try clause.

As you saw earlier, when syntactically correct code runs into an error, Python will throw an exception error. This exception error will crash the program if it is unhandled. The except clause determines how your program responds to exceptions.

The following function can help you understand the try and except block:

def linux_interaction():

assert ('linux' in sys.platform), "Function can only run on Linux systems."

print('Doing something.')

The linux_interaction() can only run on a Linux system. The assert in this function will throw an AssertionError exception if you call it on an operating system other then Linux.

You can give the function a try using the following code:

try:

linux_interaction()

except:

pass

The way you handled the error here is by handing out a pass. If you were to run this code on a Windows machine, you would get the following output:

You got nothing. The good thing here is that the program did not crash. But it would be nice to see if some type of exception occurred whenever you ran your code. To this end, you can change the pass into something that would generate an informative message, like so:

try:

linux_interaction()

except:

print('Linux function was not executed')

Execute this code on a Windows machine:

Linux function was not executed

When an exception occurs in a program running this function, the program will continue as well as inform you about the fact that the function call was not successful.

What you did not get to see was the type of error that was thrown as a result of the function call. In order to see exactly what went wrong, you would need to catch the error that the function threw.

The following code is an example where you capture the AssertionError and output that message to screen:

try:

linux_interaction()

except AssertionError as error:

print(error)

print('The linux_interaction() function was not executed')

Running this function on a Windows machine outputs the following:

Function can only run on Linux systems.

The linux_interaction() function was not executed

The first message is the AssertionError, informing you that the function can only be executed on a Linux machine. The second message tells you which function was not executed.

In the previous example, you called a function that you wrote yourself. When you executed the function, you caught the AssertionError exception and printed it to screen.

Here’s another example where you open a file and use a built-in exception:

try:

with open('file.log') as file:

read_data = file.read()

except:

print('Could not open file.log')

If file.log does not exist, this block of code will output the following:

This is an informative message, and our program will still continue to run. In the Python docs, you can see that there are a lot of built-in exceptions that you can use here. One exception described on that page is the following:

Exception

FileNotFoundErrorRaised when a file or directory is requested but doesn’t exist. Corresponds to errno ENOENT.

To catch this type of exception and print it to screen, you could use the following code:

try:

with open('file.log') as file:

read_data = file.read()

except FileNotFoundError as fnf_error:

print(fnf_error)

In this case, if file.log does not exist, the output will be the following:

[Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'file.log'

You can have more than one function call in your try clause and anticipate catching various exceptions. A thing to note here is that the code in the try clause will stop as soon as an exception is encountered.

Look at the following code. Here, you first call the linux_interaction() function and then try to open a file:

try:

linux_interaction()

with open('file.log') as file:

read_data = file.read()

except FileNotFoundError as fnf_error:

print(fnf_error)

except AssertionError as error:

print(error)

print('Linux linux_interaction() function was not executed')

If the file does not exist, running this code on a Windows machine will output the following:

Function can only run on Linux systems.

Linux linux_interaction() function was not executed

Inside the try clause, you ran into an exception immediately and did not get to the part where you attempt to open file.log. Now look at what happens when you run the code on a Linux machine:

[Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'file.log'

Here are the key takeaways:

- A

tryclause is executed up until the point where the first exception is encountered. - Inside the

exceptclause, or the exception handler, you determine how the program responds to the exception. - You can anticipate multiple exceptions and differentiate how the program should respond to them.

- Avoid using bare

exceptclauses.

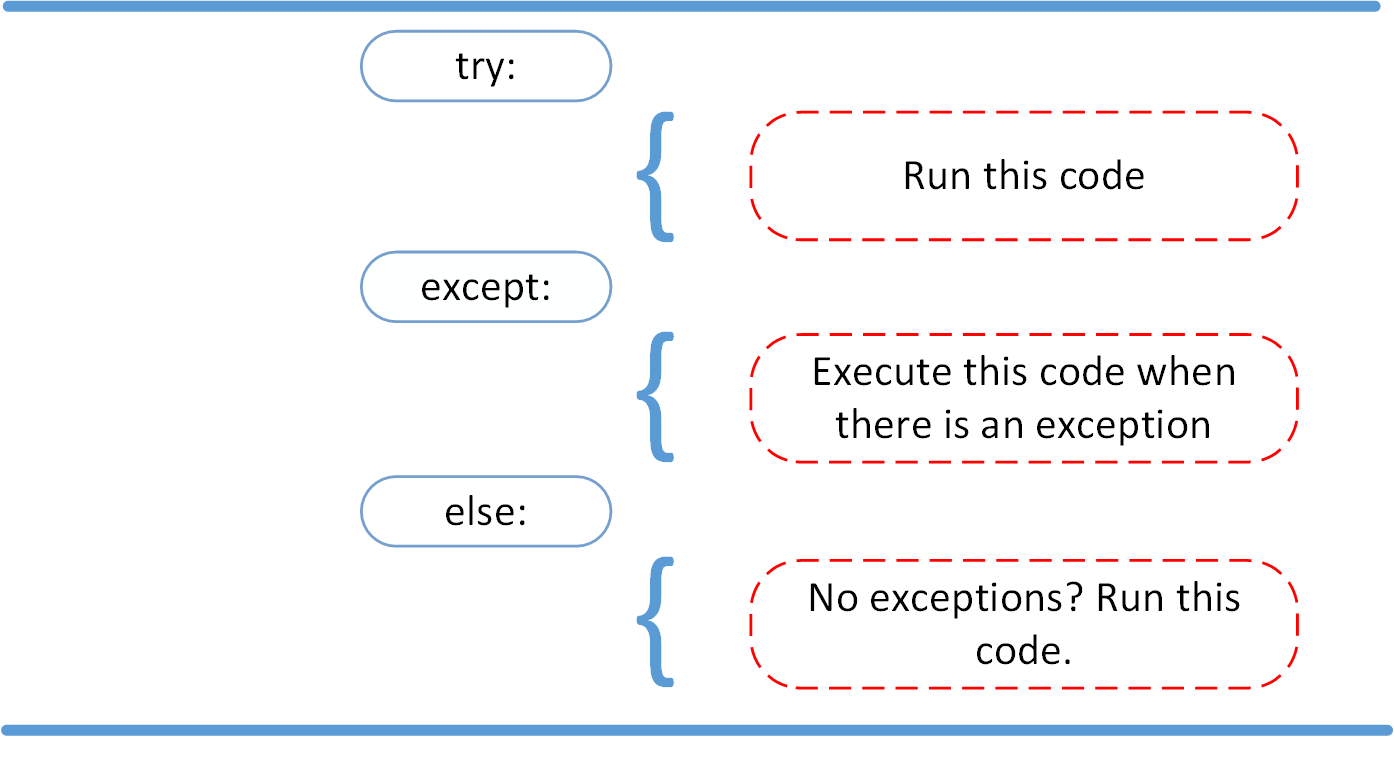

The else Clause

In Python, using the else statement, you can instruct a program to execute a certain block of code only in the absence of exceptions.

Look at the following example:

try:

linux_interaction()

except AssertionError as error:

print(error)

else:

print('Executing the else clause.')

If you were to run this code on a Linux system, the output would be the following:

Doing something.

Executing the else clause.

Because the program did not run into any exceptions, the else clause was executed.

You can also try to run code inside the else clause and catch possible exceptions there as well:

try:

linux_interaction()

except AssertionError as error:

print(error)

else:

try:

with open('file.log') as file:

read_data = file.read()

except FileNotFoundError as fnf_error:

print(fnf_error)

If you were to execute this code on a Linux machine, you would get the following result:

Doing something.

[Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'file.log'

From the output, you can see that the linux_interaction() function ran. Because no exceptions were encountered, an attempt to open file.log was made. That file did not exist, and instead of opening the file, you caught the FileNotFoundError exception.

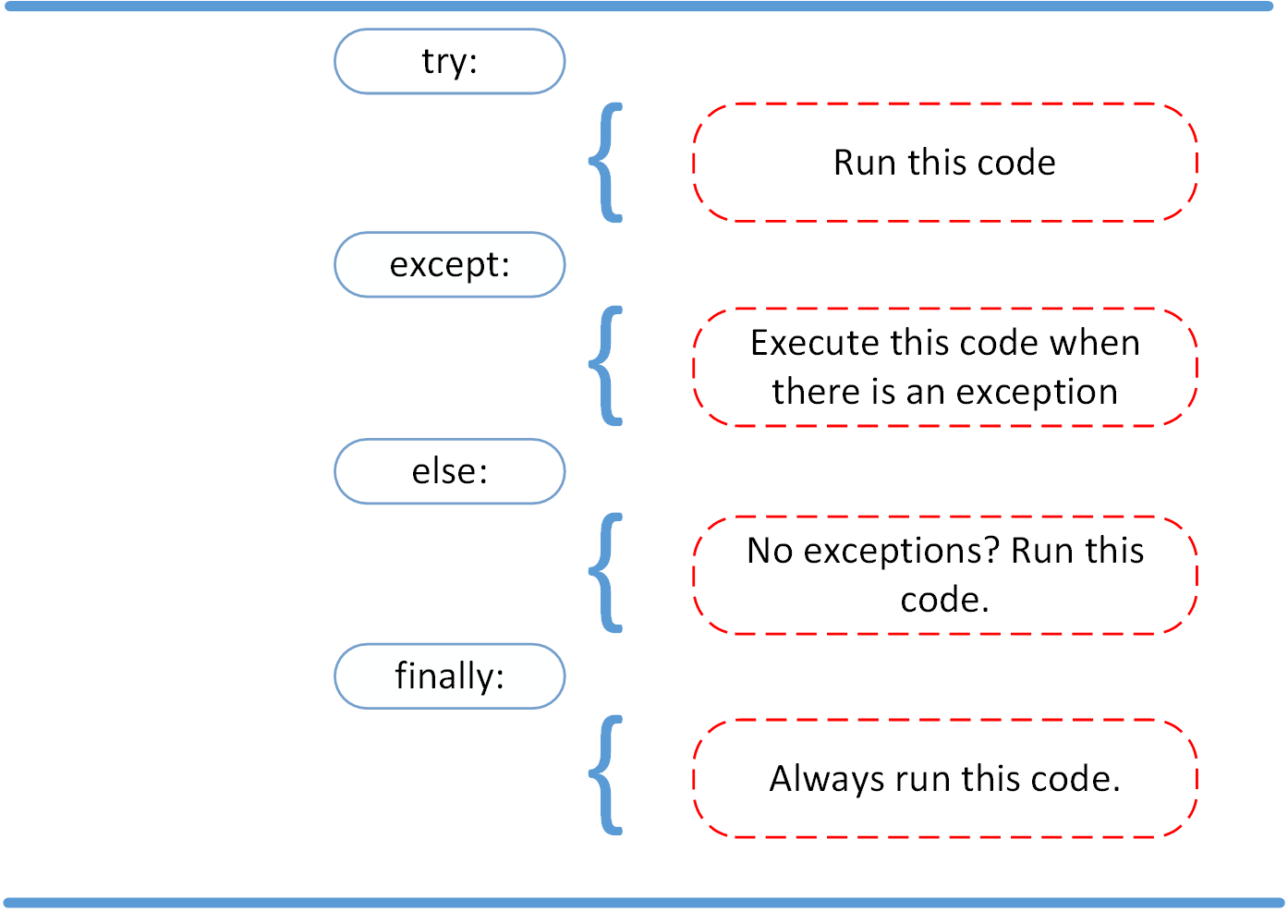

Cleaning Up After Using finally

Imagine that you always had to implement some sort of action to clean up after executing your code. Python enables you to do so using the finally clause.

Have a look at the following example:

try:

linux_interaction()

except AssertionError as error:

print(error)

else:

try:

with open('file.log') as file:

read_data = file.read()

except FileNotFoundError as fnf_error:

print(fnf_error)

finally:

print('Cleaning up, irrespective of any exceptions.')

In the previous code, everything in the finally clause will be executed. It does not matter if you encounter an exception somewhere in the try or else clauses. Running the previous code on a Windows machine would output the following:

Function can only run on Linux systems.

Cleaning up, irrespective of any exceptions.

Summing Up

After seeing the difference between syntax errors and exceptions, you learned about various ways to raise, catch, and handle exceptions in Python. In this article, you saw the following options:

raiseallows you to throw an exception at any time.assertenables you to verify if a certain condition is met and throw an exception if it isn’t.- In the

tryclause, all statements are executed until an exception is encountered. exceptis used to catch and handle the exception(s) that are encountered in the try clause.elselets you code sections that should run only when no exceptions are encountered in the try clause.finallyenables you to execute sections of code that should always run, with or without any previously encountered exceptions.

Hopefully, this article helped you understand the basic tools that Python has to offer when dealing with exceptions.

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Raising and Handling Python Exceptions

В этом руководстве мы расскажем, как обрабатывать исключения в Python с помощью try и except. Рассмотрим общий синтаксис и простые примеры, обсудим, что может пойти не так, и предложим меры по исправлению положения.

Зачастую разработчик может предугадать возникновение ошибок при работе даже синтаксически и логически правильной программы. Эти ошибки могут быть вызваны неверными входными данными или некоторыми предсказуемыми несоответствиями.

Для обработки большей части этих ошибок как исключений в Python есть блоки try и except.

Для начала разберем синтаксис операторов try и except в Python. Общий шаблон представлен ниже:

try:

# В этом блоке могут быть ошибки

except <error type>:

# Сделай это для обработки исключения;

# выполняется, если блок try выбрасывает ошибку

else:

# Сделай это, если блок try выполняется успешно, без ошибок

finally:

# Этот блок выполняется всегда

Давайте посмотрим, для чего используются разные блоки.

Блок try

Блок try — это блок кода, который вы хотите попробовать выполнить. Однако во время выполнения из-за какого-нибудь исключения могут возникнуть ошибки. Поэтому этот блок может не работать должным образом.

Блок except

Блок except запускается, когда блок try не срабатывает из-за исключения. Инструкции в этом блоке часто дают некоторый контекст того, что пошло не так внутри блока try.

Если собираетесь перехватить ошибку как исключение, в блоке except нужно обязательно указать тип этой ошибки. В приведенном выше сниппете место для указания типа ошибки обозначено плейсхолдером <error type> .

except можно использовать и без указания типа ошибки. Но лучше так не делать. При таком подходе не учитывается, что возникающие ошибки могут быть разных типов. То есть вы будете знать, что что-то пошло не так, но что именно произошло, какая была ошибка — вам будет не известно.

При попытке выполнить код внутри блока try также существует вероятность возникновения нескольких ошибок.

Например, вы можете попытаться обратиться к элементу списка по индексу, выходящему за пределы допустимого диапазона, использовать неправильный ключ словаря и попробовать открыть несуществующий файл – и все это внутри одного блока try.

В результате вы можете столкнуться с IndexError, KeyError и FileNotFoundError. В таком случае нужно добавить столько блоков except, сколько ошибок ожидается – по одному для каждого типа ошибки.

Блок else

Блок else запускается только в том случае, если блок try выполняется без ошибок. Это может быть полезно, когда нужно выполнить ещё какие-то действия после успешного выполнения блока try. Например, после успешного открытия файла вы можете прочитать его содержимое.

Блок finally

Блок finally выполняется всегда, независимо от того, что происходит в других блоках. Это полезно, когда вы хотите освободить ресурсы после выполнения определенного блока кода.

Примечание: блоки else и finally не являются обязательными. В большинстве случаев вы можете использовать только блок try, чтобы что-то сделать, и перехватывать ошибки как исключения внутри блока except.

[python_ad_block]

Итак, теперь давайте используем полученные знания для обработки исключений в Python. Приступим!

Обработка ZeroDivisionError

Рассмотрим функцию divide(), показанную ниже. Она принимает два аргумента – num и div – и возвращает частное от операции деления num/div.

def divide(num,div):

return num/div

Вызов функции с разными аргументами возвращает ожидаемый результат:

res = divide(100,8) print(res) # Output # 12.5 res = divide(568,64) print(res) # Output # 8.875

Этот код работает нормально, пока вы не попробуете разделить число на ноль:

divide(27,0)

Вы видите, что программа выдает ошибку ZeroDivisionError:

# Output

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ZeroDivisionError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-19-932ea024ce43> in <module>()

----> 1 divide(27,0)

<ipython-input-1-c98670fd7a12> in divide(num, div)

1 def divide(num,div):

----> 2 return num/div

ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

Можно обработать деление на ноль как исключение, выполнив следующие действия:

- В блоке

tryпоместите вызов функцииdivide(). По сути, вы пытаетесь разделитьnumнаdiv(try в переводе с английского — «пытаться», — прим. перев.). - В блоке

exceptобработайте случай, когдаdivравен 0, как исключение. - В результате этих действий при делении на ноль больше не будет выбрасываться ZeroDivisionError. Вместо этого будет выводиться сообщение, информирующее пользователя, что он попытался делить на ноль.

Вот как все это выглядит в коде:

try:

res = divide(num,div)

print(res)

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("You tried to divide by zero :( ")

При корректных входных данных наш код по-прежнему работает великолепно:

divide(10,2) # Output # 5.0

Когда же пользователь попытается разделить на ноль, он получит уведомление о возникшем исключении. Таким образом, программа завершается корректно и без ошибок.

divide(10,0) # Output # You tried to divide by zero :(

Обработка TypeError

В этом разделе мы разберем, как использовать try и except для обработки TypeError в Python.

Рассмотрим функцию add_10(). Она принимает число в качестве аргумента, прибавляет к нему 10 и возвращает результат этого сложения.

def add_10(num):

return num + 10

Вы можете вызвать функцию add_10() с любым числом, и она будет работать нормально, как показано ниже:

result = add_10(89) print(result) # Output # 99

Теперь попробуйте вызвать функцию add_10(), передав ей в качестве аргумента не число, а строку.

add_10 ("five")

Ваша программа вылетит со следующим сообщением об ошибке:

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-15-9844e949c84e> in <module>()

----> 1 add_10("five")

<ipython-input-13-2e506d74d919> in add_10(num)

1 def add_10(num):

----> 2 return num + 10

TypeError: can only concatenate str (not "int") to str

Сообщение об ошибке TypeError: can only concatenate str (not "int") to str говорит о том, что можно сложить только две строки, а не добавить целое число к строке.

Обработаем TypeError:

- В блок try мы помещаем вызов функции

add_10()с my_num в качестве аргумента. Если аргумент допустимого типа, исключений не возникнет. - В противном случае срабатывает блок

except, в который мы помещаем вывод уведомления для пользователя о том, что аргумент имеет недопустимый тип.

Это показано ниже:

my_num = "five"

try:

result = add_10(my_num)

print(result)

except TypeError:

print("The argument `num` should be a number")

Поскольку теперь вы обработали TypeError как исключение, при передаче невалидного аргумента ошибка не возникает. Вместо нее выводится сообщение, что аргумент имеет недопустимый тип.

The argument `num` should be a number

Обработка IndexError

Если вам приходилось работать со списками или любыми другими итерируемыми объектами, вы, вероятно, сталкивались с IndexError.

Это связано с тем, что часто бывает сложно отслеживать все изменения в итерациях. И вы можете попытаться получить доступ к элементу по невалидному индексу.

В этом примере список my_list состоит из 4 элементов. Допустимые индексы — 0, 1, 2 и 3 и -1, -2, -3, -4, если вы используете отрицательную индексацию.

Поскольку 2 является допустимым индексом, вы видите, что элемент с этим индексом (C++) распечатывается:

my_list = ["Python","C","C++","JavaScript"] print(my_list[2]) # Output # C++

Но если вы попытаетесь получить доступ к элементу по индексу, выходящему за пределы допустимого диапазона, вы столкнетесь с IndexError:

print(my_list[4])

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

IndexError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-7-437bc6501dea> in <module>()

1 my_list = ["Python","C","C++","JavaScript"]

----> 2 print(my_list[4])

IndexError: list index out of range

Теперь вы уже знакомы с шаблоном, и вам не составит труда использовать try и except для обработки данной ошибки.

В приведенном ниже фрагменте кода мы пытаемся получить доступ к элементу по индексу search_idx.

search_idx = 3

try:

print(my_list[search_idx])

except IndexError:

print("Sorry, the list index is out of range")

Здесь search_idx = 3 является допустимым индексом, поэтому в результате выводится соответствующий элемент — JavaScript.

Если search_idx находится за пределами допустимого диапазона индексов, блок except перехватывает IndexError как исключение, и больше нет длинных сообщений об ошибках.

search_idx = 4

try:

print(my_list[search_idx])

except IndexError:

print("Sorry, the list index is out of range")

Вместо этого отображается сообщение о том, что search_idx находится вне допустимого диапазона индексов:

Sorry, the list index is out of range

Обработка KeyError

Вероятно, вы уже сталкивались с KeyError при работе со словарями в Python.

Рассмотрим следующий пример, где у нас есть словарь my_dict.

my_dict ={"key1":"value1","key2":"value2","key3":"value3"}

search_key = "non-existent key"

print(my_dict[search_key])

В словаре my_dict есть 3 пары «ключ-значение»: key1:value1, key2:value2 и key3:value3.

Теперь попытаемся получить доступ к значению, соответствующему несуществующему ключу non-existent key.

Как и ожидалось, мы получим KeyError:

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

KeyError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-2-2a61d404be04> in <module>()

1 my_dict ={"key1":"value1","key2":"value2","key3":"value3"}

2 search_key = "non-existent key"

----> 3 my_dict[search_key]

KeyError: 'non-existent key'

Вы можете обработать KeyError почти так же, как и IndexError.

- Пробуем получить доступ к значению, которое соответствует ключу, определенному

search_key. - Если

search_key— валидный ключ, мы распечатываем соответствующее значение. - Если ключ невалиден и возникает исключение — задействуется блок except, чтобы сообщить об этом пользователю.

Все это можно видеть в следующем коде:

try:

print(my_dict[search_key])

except KeyError:

print("Sorry, that's not a valid key!")

# Output:

# Sorry, that's not a valid key!

Если вы хотите предоставить дополнительный контекст, например имя невалидного ключа, это тоже можно сделать. Возможно, ключ оказался невалидным из-за ошибки в написании. Если вы укажете этот ключ в сообщении, это поможет пользователю исправить опечатку.

Вы можете сделать это, перехватив невалидный ключ как <error_msg> и используя его в сообщении, которое печатается при возникновении исключения:

try:

print(my_dict[search_key])

except KeyError as error_msg:

print(f"Sorry,{error_msg} is not a valid key!")

Обратите внимание, что теперь в сообщении об ошибки указано также и имя несуществующего ключа:

Sorry, 'non-existent key' is not a valid key!

Обработка FileNotFoundError

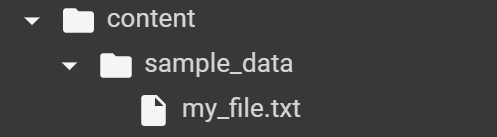

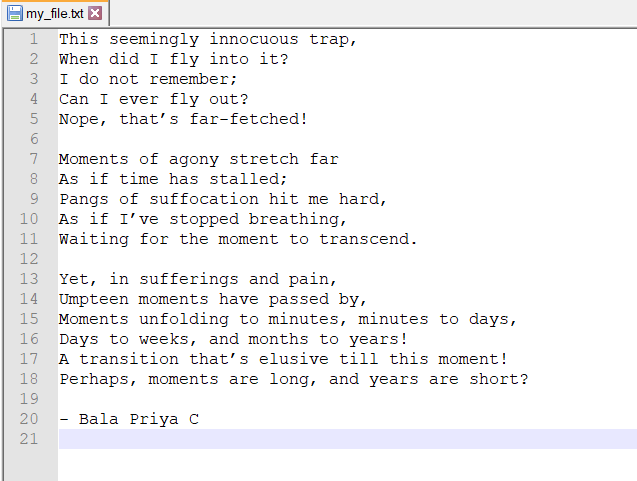

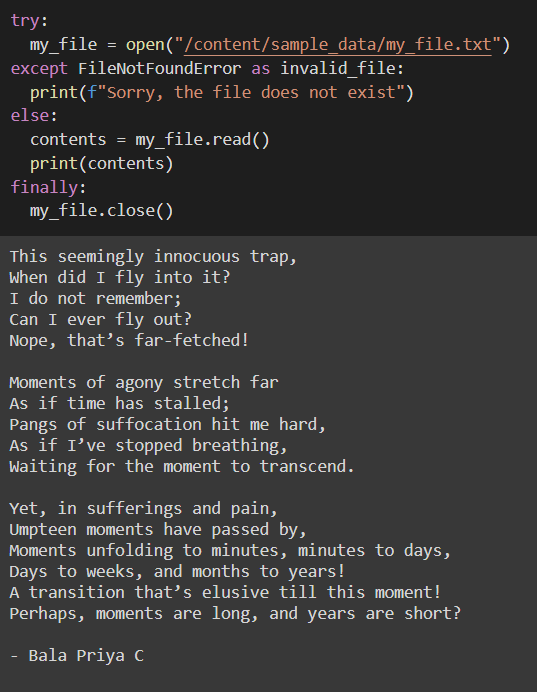

При работе с файлами в Python часто возникает ошибка FileNotFoundError.

В следующем примере мы попытаемся открыть файл my_file.txt, указав его путь в функции open(). Мы хотим прочитать файл и вывести его содержимое.

Однако мы еще не создали этот файл в указанном месте.

my_file = open("/content/sample_data/my_file.txt")

contents = my_file.read()

print(contents)

Поэтому, попытавшись запустить приведенный выше фрагмент кода, мы получим FileNotFoundError:

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

FileNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-4-4873cac1b11a> in <module>()

----> 1 my_file = open("my_file.txt")

FileNotFoundError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'my_file.txt'

А с помощью try и except мы можем сделать следующее:

- Попробуем открыть файл в блоке

try. - Обработаем

FileNotFoundErrorв блокеexcept, сообщив пользователю, что он попытался открыть несуществующий файл. - Если блок

tryзавершается успешно и файл действительно существует, прочтем и распечатаем содержимое. - В блоке

finallyзакроем файл, чтобы не терять ресурсы. Файл будет закрыт независимо от того, что происходило на этапах открытия и чтения.

try:

my_file = open("/content/sample_data/my_file.txt")

except FileNotFoundError:

print(f"Sorry, the file does not exist")

else:

contents = my_file.read()

print(contents)

finally:

my_file.close()

Обратите внимание: мы обработали ошибку как исключение, и программа завершает работу, отображая следующее сообщение:

Sorry, the file does not exist

Теперь рассмотрим случай, когда срабатывает блок else. Файл my_file.txt теперь присутствует по указанному ранее пути.

Вот содержимое этого файла:

Теперь повторный запуск нашего кода работает должным образом.

На этот раз файл my_file.txt присутствует, поэтому запускается блок else и содержимое распечатывается, как показано ниже:

Надеемся, теперь вы поняли, как обрабатывать исключения при работе с файлами.

Заключение

В этом руководстве мы рассмотрели, как обрабатывать исключения в Python с помощью try и except.

Также мы разобрали на примерах, какие типы исключений могут возникать и как при помощи except ловить наиболее распространенные ошибки.

Надеемся, вам понравился этот урок. Успехов в написании кода!

Перевод статьи «Python Try and Except Statements – How to Handle Exceptions in Python».

Python try-except blocks are used for exception handling or error handling. With the use of try-except block in your program, you can allow your program to continue or terminate at a point or show messages.

If an error occurred in the program, then the try block will pass to except block. In addition, you can also use a finally block to execute whether an exception occurs or not.

Important terms in Python try-except block.

trya block of code to the probability of error.exceptblock lets you handle the error.- else block if no exception in the program.

- finally regardless of the result of the try- and except blocks, this code always executes.

Syntax :

Simple syntax of try except block.

Basic Syntax :

try:

// Code

except:

// Code

Python try except Example

This is a simple sample of try-except block in python. If the arithmetic operation will be done then nothing print otherwise the output will be an error message.

try:

print(0 / 0)

except:

print("An exception occurred")

Output: An exception occurred

Example try except a print error in python

An example of how to python “except exception as e” and print error in console.

try:

print(1 / 0)

except Exception as e:

print(e)

Output: division by zero

Example try except Else

You can use python try except else to execute a block of code in if no error raised.

try:

print(1 / 1)

except Exception as e:

print(e)

else:

print("No Error")

Output: 1.0

No Error

Example try-except Finally in Python

Finally, code of block always execute on error or not.

try:

print(1 / 0)

except Exception as e:

print(e)

else:

print("No Error")

finally:

print("Always print finally python code")

Output: division by zero

Always print finally python code

QA: What is the use of finally block in Python try-except error handling?

It can be an interview question.

Finally, the block can be useful to close objects and clean up resources, like close a writable file or database.

Like this example of writing a file in python.

case: if file existing or creates it.

try:

mfile = open("textfile.txt", "w")

mfile.write("EyeHunts")

except Exception as ex:

print(ex)

finally:

mfile.close()

print('File Closed')

Output: File Closed

case: if file not existing

try:

mfile = open("textfile.txt")

mfile.write("EyeHunts")

except Exception as ex:

print(ex)

finally:

print('File Closed call')

mfile.close()

Output:

Note: This tutorial is explained about exception handling blocks and how to use them. You must read about details about exception handling in this tutorial – Python exception Handling | Error Handling

As another language like Java using a try-catch for exception handling. If you are looking for a python try-catch, then you will not find it. Python has a try-except instead of try-catch exception handling.

Do comment if you have any doubts and suggestion on this tutorial.

Note: This example (Project) is developed in PyCharm 2018.2 (Community Edition)

JRE: 1.8.0

JVM: OpenJDK 64-Bit Server VM by JetBrains s.r.o

macOS 10.13.6Python 3.7

All examples are in try except python 3, so it may change its different from python 2 or upgraded versions.

Degree in Computer Science and Engineer: App Developer and has multiple Programming languages experience. Enthusiasm for technology & like learning technical.

Until now error messages haven’t been more than mentioned, but if you have tried

out the examples you have probably seen some. There are (at least) two

distinguishable kinds of errors: syntax errors and exceptions.

8.1. Syntax Errors¶

Syntax errors, also known as parsing errors, are perhaps the most common kind of

complaint you get while you are still learning Python:

>>> while True print('Hello world') File "<stdin>", line 1 while True print('Hello world') ^ SyntaxError: invalid syntax

The parser repeats the offending line and displays a little ‘arrow’ pointing at

the earliest point in the line where the error was detected. The error is

caused by (or at least detected at) the token preceding the arrow: in the

example, the error is detected at the function print(), since a colon

(':') is missing before it. File name and line number are printed so you

know where to look in case the input came from a script.

8.2. Exceptions¶

Even if a statement or expression is syntactically correct, it may cause an

error when an attempt is made to execute it. Errors detected during execution

are called exceptions and are not unconditionally fatal: you will soon learn

how to handle them in Python programs. Most exceptions are not handled by

programs, however, and result in error messages as shown here:

>>> 10 * (1/0) Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> ZeroDivisionError: division by zero >>> 4 + spam*3 Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> NameError: name 'spam' is not defined >>> '2' + 2 Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> TypeError: Can't convert 'int' object to str implicitly

The last line of the error message indicates what happened. Exceptions come in

different types, and the type is printed as part of the message: the types in

the example are ZeroDivisionError, NameError and TypeError.

The string printed as the exception type is the name of the built-in exception

that occurred. This is true for all built-in exceptions, but need not be true

for user-defined exceptions (although it is a useful convention). Standard

exception names are built-in identifiers (not reserved keywords).

The rest of the line provides detail based on the type of exception and what

caused it.

The preceding part of the error message shows the context where the exception

happened, in the form of a stack traceback. In general it contains a stack

traceback listing source lines; however, it will not display lines read from

standard input.

Built-in Exceptions lists the built-in exceptions and their meanings.

8.3. Handling Exceptions¶

It is possible to write programs that handle selected exceptions. Look at the

following example, which asks the user for input until a valid integer has been

entered, but allows the user to interrupt the program (using Control-C or

whatever the operating system supports); note that a user-generated interruption

is signalled by raising the KeyboardInterrupt exception.

>>> while True: ... try: ... x = int(input("Please enter a number: ")) ... break ... except ValueError: ... print("Oops! That was no valid number. Try again...") ...

The try statement works as follows.

- First, the try clause (the statement(s) between the

tryand

exceptkeywords) is executed. - If no exception occurs, the except clause is skipped and execution of the

trystatement is finished. - If an exception occurs during execution of the try clause, the rest of the

clause is skipped. Then if its type matches the exception named after the

exceptkeyword, the except clause is executed, and then execution

continues after thetrystatement. - If an exception occurs which does not match the exception named in the except

clause, it is passed on to outertrystatements; if no handler is

found, it is an unhandled exception and execution stops with a message as

shown above.

A try statement may have more than one except clause, to specify

handlers for different exceptions. At most one handler will be executed.

Handlers only handle exceptions that occur in the corresponding try clause, not

in other handlers of the same try statement. An except clause may

name multiple exceptions as a parenthesized tuple, for example:

... except (RuntimeError, TypeError, NameError): ... pass

A class in an except clause is compatible with an exception if it is

the same class or a base class thereof (but not the other way around — an

except clause listing a derived class is not compatible with a base class). For

example, the following code will print B, C, D in that order:

class B(Exception): pass class C(B): pass class D(C): pass for cls in [B, C, D]: try: raise cls() except D: print("D") except C: print("C") except B: print("B")

Note that if the except clauses were reversed (with except B first), it

would have printed B, B, B — the first matching except clause is triggered.

The last except clause may omit the exception name(s), to serve as a wildcard.

Use this with extreme caution, since it is easy to mask a real programming error

in this way! It can also be used to print an error message and then re-raise

the exception (allowing a caller to handle the exception as well):

import sys try: f = open('myfile.txt') s = f.readline() i = int(s.strip()) except OSError as err: print("OS error: {0}".format(err)) except ValueError: print("Could not convert data to an integer.") except: print("Unexpected error:", sys.exc_info()[0]) raise

The try … except statement has an optional else

clause, which, when present, must follow all except clauses. It is useful for

code that must be executed if the try clause does not raise an exception. For

example:

for arg in sys.argv[1:]: try: f = open(arg, 'r') except OSError: print('cannot open', arg) else: print(arg, 'has', len(f.readlines()), 'lines') f.close()

The use of the else clause is better than adding additional code to

the try clause because it avoids accidentally catching an exception

that wasn’t raised by the code being protected by the try …

except statement.

When an exception occurs, it may have an associated value, also known as the

exception’s argument. The presence and type of the argument depend on the

exception type.

The except clause may specify a variable after the exception name. The

variable is bound to an exception instance with the arguments stored in

instance.args. For convenience, the exception instance defines

__str__() so the arguments can be printed directly without having to

reference .args. One may also instantiate an exception first before

raising it and add any attributes to it as desired.

>>> try: ... raise Exception('spam', 'eggs') ... except Exception as inst: ... print(type(inst)) # the exception instance ... print(inst.args) # arguments stored in .args ... print(inst) # __str__ allows args to be printed directly, ... # but may be overridden in exception subclasses ... x, y = inst.args # unpack args ... print('x =', x) ... print('y =', y) ... <class 'Exception'> ('spam', 'eggs') ('spam', 'eggs') x = spam y = eggs

If an exception has arguments, they are printed as the last part (‘detail’) of

the message for unhandled exceptions.

Exception handlers don’t just handle exceptions if they occur immediately in the

try clause, but also if they occur inside functions that are called (even

indirectly) in the try clause. For example:

>>> def this_fails(): ... x = 1/0 ... >>> try: ... this_fails() ... except ZeroDivisionError as err: ... print('Handling run-time error:', err) ... Handling run-time error: division by zero

8.4. Raising Exceptions¶

The raise statement allows the programmer to force a specified

exception to occur. For example:

>>> raise NameError('HiThere') Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> NameError: HiThere

The sole argument to raise indicates the exception to be raised.

This must be either an exception instance or an exception class (a class that

derives from Exception). If an exception class is passed, it will

be implicitly instantiated by calling its constructor with no arguments:

raise ValueError # shorthand for 'raise ValueError()'

If you need to determine whether an exception was raised but don’t intend to

handle it, a simpler form of the raise statement allows you to

re-raise the exception:

>>> try: ... raise NameError('HiThere') ... except NameError: ... print('An exception flew by!') ... raise ... An exception flew by! Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 2, in <module> NameError: HiThere

8.5. User-defined Exceptions¶

Programs may name their own exceptions by creating a new exception class (see

Classes for more about Python classes). Exceptions should typically

be derived from the Exception class, either directly or indirectly.

Exception classes can be defined which do anything any other class can do, but

are usually kept simple, often only offering a number of attributes that allow

information about the error to be extracted by handlers for the exception. When

creating a module that can raise several distinct errors, a common practice is

to create a base class for exceptions defined by that module, and subclass that

to create specific exception classes for different error conditions:

class Error(Exception): """Base class for exceptions in this module.""" pass class InputError(Error): """Exception raised for errors in the input. Attributes: expression -- input expression in which the error occurred message -- explanation of the error """ def __init__(self, expression, message): self.expression = expression self.message = message class TransitionError(Error): """Raised when an operation attempts a state transition that's not allowed. Attributes: previous -- state at beginning of transition next -- attempted new state message -- explanation of why the specific transition is not allowed """ def __init__(self, previous, next, message): self.previous = previous self.next = next self.message = message

Most exceptions are defined with names that end in “Error,” similar to the

naming of the standard exceptions.

Many standard modules define their own exceptions to report errors that may

occur in functions they define. More information on classes is presented in

chapter Classes.

8.6. Defining Clean-up Actions¶

The try statement has another optional clause which is intended to

define clean-up actions that must be executed under all circumstances. For

example:

>>> try: ... raise KeyboardInterrupt ... finally: ... print('Goodbye, world!') ... Goodbye, world! KeyboardInterrupt Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 2, in <module>

A finally clause is always executed before leaving the try

statement, whether an exception has occurred or not. When an exception has

occurred in the try clause and has not been handled by an

except clause (or it has occurred in an except or

else clause), it is re-raised after the finally clause has

been executed. The finally clause is also executed “on the way out”

when any other clause of the try statement is left via a

break, continue or return statement. A more

complicated example:

>>> def divide(x, y): ... try: ... result = x / y ... except ZeroDivisionError: ... print("division by zero!") ... else: ... print("result is", result) ... finally: ... print("executing finally clause") ... >>> divide(2, 1) result is 2.0 executing finally clause >>> divide(2, 0) division by zero! executing finally clause >>> divide("2", "1") executing finally clause Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> File "<stdin>", line 3, in divide TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for /: 'str' and 'str'

As you can see, the finally clause is executed in any event. The

TypeError raised by dividing two strings is not handled by the

except clause and therefore re-raised after the finally

clause has been executed.

In real world applications, the finally clause is useful for

releasing external resources (such as files or network connections), regardless

of whether the use of the resource was successful.

8.7. Predefined Clean-up Actions¶

Some objects define standard clean-up actions to be undertaken when the object

is no longer needed, regardless of whether or not the operation using the object

succeeded or failed. Look at the following example, which tries to open a file

and print its contents to the screen.

for line in open("myfile.txt"): print(line, end="")

The problem with this code is that it leaves the file open for an indeterminate

amount of time after this part of the code has finished executing.

This is not an issue in simple scripts, but can be a problem for larger

applications. The with statement allows objects like files to be

used in a way that ensures they are always cleaned up promptly and correctly.

with open("myfile.txt") as f: for line in f: print(line, end="")

After the statement is executed, the file f is always closed, even if a

problem was encountered while processing the lines. Objects which, like files,

provide predefined clean-up actions will indicate this in their documentation.