From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

«Systematic bias» redirects here. For the sociological and organizational phenomenon, see Systemic bias.

Observational error (or measurement error) is the difference between a measured value of a quantity and its true value.[1] In statistics, an error is not necessarily a «mistake». Variability is an inherent part of the results of measurements and of the measurement process.

Measurement errors can be divided into two components: random and systematic.[2]

Random errors are errors in measurement that lead to measurable values being inconsistent when repeated measurements of a constant attribute or quantity are taken. Systematic errors are errors that are not determined by chance but are introduced by repeatable processes inherent to the system.[3] Systematic error may also refer to an error with a non-zero mean, the effect of which is not reduced when observations are averaged.[citation needed]

Measurement errors can be summarized in terms of accuracy and precision.

Measurement error should not be confused with measurement uncertainty.

Science and experiments[edit]

When either randomness or uncertainty modeled by probability theory is attributed to such errors, they are «errors» in the sense in which that term is used in statistics; see errors and residuals in statistics.

Every time we repeat a measurement with a sensitive instrument, we obtain slightly different results. The common statistical model used is that the error has two additive parts:

- Systematic error which always occurs, with the same value, when we use the instrument in the same way and in the same case.

- Random error which may vary from observation to another.

Systematic error is sometimes called statistical bias. It may often be reduced with standardized procedures. Part of the learning process in the various sciences is learning how to use standard instruments and protocols so as to minimize systematic error.

Random error (or random variation) is due to factors that cannot or will not be controlled. One possible reason to forgo controlling for these random errors is that it may be too expensive to control them each time the experiment is conducted or the measurements are made. Other reasons may be that whatever we are trying to measure is changing in time (see dynamic models), or is fundamentally probabilistic (as is the case in quantum mechanics — see Measurement in quantum mechanics). Random error often occurs when instruments are pushed to the extremes of their operating limits. For example, it is common for digital balances to exhibit random error in their least significant digit. Three measurements of a single object might read something like 0.9111g, 0.9110g, and 0.9112g.

Characterization[edit]

Measurement errors can be divided into two components: random error and systematic error.[2]

Random error is always present in a measurement. It is caused by inherently unpredictable fluctuations in the readings of a measurement apparatus or in the experimenter’s interpretation of the instrumental reading. Random errors show up as different results for ostensibly the same repeated measurement. They can be estimated by comparing multiple measurements and reduced by averaging multiple measurements.

Systematic error is predictable and typically constant or proportional to the true value. If the cause of the systematic error can be identified, then it usually can be eliminated. Systematic errors are caused by imperfect calibration of measurement instruments or imperfect methods of observation, or interference of the environment with the measurement process, and always affect the results of an experiment in a predictable direction. Incorrect zeroing of an instrument leading to a zero error is an example of systematic error in instrumentation.

The Performance Test Standard PTC 19.1-2005 “Test Uncertainty”, published by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), discusses systematic and random errors in considerable detail. In fact, it conceptualizes its basic uncertainty categories in these terms.

Random error can be caused by unpredictable fluctuations in the readings of a measurement apparatus, or in the experimenter’s interpretation of the instrumental reading; these fluctuations may be in part due to interference of the environment with the measurement process. The concept of random error is closely related to the concept of precision. The higher the precision of a measurement instrument, the smaller the variability (standard deviation) of the fluctuations in its readings.

Sources[edit]

Sources of systematic error[edit]

Imperfect calibration[edit]

Sources of systematic error may be imperfect calibration of measurement instruments (zero error), changes in the environment which interfere with the measurement process and sometimes imperfect methods of observation can be either zero error or percentage error. If you consider an experimenter taking a reading of the time period of a pendulum swinging past a fiducial marker: If their stop-watch or timer starts with 1 second on the clock then all of their results will be off by 1 second (zero error). If the experimenter repeats this experiment twenty times (starting at 1 second each time), then there will be a percentage error in the calculated average of their results; the final result will be slightly larger than the true period.

Distance measured by radar will be systematically overestimated if the slight slowing down of the waves in air is not accounted for. Incorrect zeroing of an instrument leading to a zero error is an example of systematic error in instrumentation.

Systematic errors may also be present in the result of an estimate based upon a mathematical model or physical law. For instance, the estimated oscillation frequency of a pendulum will be systematically in error if slight movement of the support is not accounted for.

Quantity[edit]

Systematic errors can be either constant, or related (e.g. proportional or a percentage) to the actual value of the measured quantity, or even to the value of a different quantity (the reading of a ruler can be affected by environmental temperature). When it is constant, it is simply due to incorrect zeroing of the instrument. When it is not constant, it can change its sign. For instance, if a thermometer is affected by a proportional systematic error equal to 2% of the actual temperature, and the actual temperature is 200°, 0°, or −100°, the measured temperature will be 204° (systematic error = +4°), 0° (null systematic error) or −102° (systematic error = −2°), respectively. Thus the temperature will be overestimated when it will be above zero and underestimated when it will be below zero.

Drift[edit]

Systematic errors which change during an experiment (drift) are easier to detect. Measurements indicate trends with time rather than varying randomly about a mean. Drift is evident if a measurement of a constant quantity is repeated several times and the measurements drift one way during the experiment. If the next measurement is higher than the previous measurement as may occur if an instrument becomes warmer during the experiment then the measured quantity is variable and it is possible to detect a drift by checking the zero reading during the experiment as well as at the start of the experiment (indeed, the zero reading is a measurement of a constant quantity). If the zero reading is consistently above or below zero, a systematic error is present. If this cannot be eliminated, potentially by resetting the instrument immediately before the experiment then it needs to be allowed by subtracting its (possibly time-varying) value from the readings, and by taking it into account while assessing the accuracy of the measurement.

If no pattern in a series of repeated measurements is evident, the presence of fixed systematic errors can only be found if the measurements are checked, either by measuring a known quantity or by comparing the readings with readings made using a different apparatus, known to be more accurate. For example, if you think of the timing of a pendulum using an accurate stopwatch several times you are given readings randomly distributed about the mean. Hopings systematic error is present if the stopwatch is checked against the ‘speaking clock’ of the telephone system and found to be running slow or fast. Clearly, the pendulum timings need to be corrected according to how fast or slow the stopwatch was found to be running.

Measuring instruments such as ammeters and voltmeters need to be checked periodically against known standards.

Systematic errors can also be detected by measuring already known quantities. For example, a spectrometer fitted with a diffraction grating may be checked by using it to measure the wavelength of the D-lines of the sodium electromagnetic spectrum which are at 600 nm and 589.6 nm. The measurements may be used to determine the number of lines per millimetre of the diffraction grating, which can then be used to measure the wavelength of any other spectral line.

Constant systematic errors are very difficult to deal with as their effects are only observable if they can be removed. Such errors cannot be removed by repeating measurements or averaging large numbers of results. A common method to remove systematic error is through calibration of the measurement instrument.

Sources of random error[edit]

The random or stochastic error in a measurement is the error that is random from one measurement to the next. Stochastic errors tend to be normally distributed when the stochastic error is the sum of many independent random errors because of the central limit theorem. Stochastic errors added to a regression equation account for the variation in Y that cannot be explained by the included Xs.

Surveys[edit]

The term «observational error» is also sometimes used to refer to response errors and some other types of non-sampling error.[1] In survey-type situations, these errors can be mistakes in the collection of data, including both the incorrect recording of a response and the correct recording of a respondent’s inaccurate response. These sources of non-sampling error are discussed in Salant and Dillman (1994) and Bland and Altman (1996).[4][5]

These errors can be random or systematic. Random errors are caused by unintended mistakes by respondents, interviewers and/or coders. Systematic error can occur if there is a systematic reaction of the respondents to the method used to formulate the survey question. Thus, the exact formulation of a survey question is crucial, since it affects the level of measurement error.[6] Different tools are available for the researchers to help them decide about this exact formulation of their questions, for instance estimating the quality of a question using MTMM experiments. This information about the quality can also be used in order to correct for measurement error.[7][8]

Effect on regression analysis[edit]

If the dependent variable in a regression is measured with error, regression analysis and associated hypothesis testing are unaffected, except that the R2 will be lower than it would be with perfect measurement.

However, if one or more independent variables is measured with error, then the regression coefficients and standard hypothesis tests are invalid.[9]: p. 187 This is known as attenuation bias.[10]

See also[edit]

- Bias (statistics)

- Cognitive bias

- Correction for measurement error (for Pearson correlations)

- Errors and residuals in statistics

- Error

- Replication (statistics)

- Statistical theory

- Metrology

- Regression dilution

- Test method

- Propagation of uncertainty

- Instrument error

- Measurement uncertainty

- Errors-in-variables models

- Systemic bias

References[edit]

- ^ a b Dodge, Y. (2003) The Oxford Dictionary of Statistical Terms, OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-920613-1

- ^ a b John Robert Taylor (1999). An Introduction to Error Analysis: The Study of Uncertainties in Physical Measurements. University Science Books. p. 94, §4.1. ISBN 978-0-935702-75-0.

- ^ «Systematic error». Merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Salant, P.; Dillman, D. A. (1994). How to conduct your survey. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-01273-4.

- ^ Bland, J. Martin; Altman, Douglas G. (1996). «Statistics Notes: Measurement Error». BMJ. 313 (7059): 744. doi:10.1136/bmj.313.7059.744. PMC 2352101. PMID 8819450.

- ^ Saris, W. E.; Gallhofer, I. N. (2014). Design, Evaluation and Analysis of Questionnaires for Survey Research (Second ed.). Hoboken: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-63461-5.

- ^ DeCastellarnau, A. and Saris, W. E. (2014). A simple procedure to correct for measurement errors in survey research. European Social Survey Education Net (ESS EduNet). Available at: http://essedunet.nsd.uib.no/cms/topics/measurement Archived 2019-09-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Saris, W. E.; Revilla, M. (2015). «Correction for measurement errors in survey research: necessary and possible» (PDF). Social Indicators Research. 127 (3): 1005–1020. doi:10.1007/s11205-015-1002-x. hdl:10230/28341. S2CID 146550566.

- ^ Hayashi, Fumio (2000). Econometrics. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01018-2.

- ^ Angrist, Joshua David; Pischke, Jörn-Steffen (2015). Mastering ‘metrics : the path from cause to effect. Princeton, New Jersey. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-691-15283-7. OCLC 877846199.

The bias generated by this sort of measurement error in regressors is called attenuation bias.

Further reading[edit]

- Cochran, W. G. (1968). «Errors of Measurement in Statistics». Technometrics. 10 (4): 637–666. doi:10.2307/1267450. JSTOR 1267450.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

«Systematic bias» redirects here. For the sociological and organizational phenomenon, see Systemic bias.

Observational error (or measurement error) is the difference between a measured value of a quantity and its true value.[1] In statistics, an error is not necessarily a «mistake». Variability is an inherent part of the results of measurements and of the measurement process.

Measurement errors can be divided into two components: random and systematic.[2]

Random errors are errors in measurement that lead to measurable values being inconsistent when repeated measurements of a constant attribute or quantity are taken. Systematic errors are errors that are not determined by chance but are introduced by repeatable processes inherent to the system.[3] Systematic error may also refer to an error with a non-zero mean, the effect of which is not reduced when observations are averaged.[citation needed]

Measurement errors can be summarized in terms of accuracy and precision.

Measurement error should not be confused with measurement uncertainty.

Science and experiments[edit]

When either randomness or uncertainty modeled by probability theory is attributed to such errors, they are «errors» in the sense in which that term is used in statistics; see errors and residuals in statistics.

Every time we repeat a measurement with a sensitive instrument, we obtain slightly different results. The common statistical model used is that the error has two additive parts:

- Systematic error which always occurs, with the same value, when we use the instrument in the same way and in the same case.

- Random error which may vary from observation to another.

Systematic error is sometimes called statistical bias. It may often be reduced with standardized procedures. Part of the learning process in the various sciences is learning how to use standard instruments and protocols so as to minimize systematic error.

Random error (or random variation) is due to factors that cannot or will not be controlled. One possible reason to forgo controlling for these random errors is that it may be too expensive to control them each time the experiment is conducted or the measurements are made. Other reasons may be that whatever we are trying to measure is changing in time (see dynamic models), or is fundamentally probabilistic (as is the case in quantum mechanics — see Measurement in quantum mechanics). Random error often occurs when instruments are pushed to the extremes of their operating limits. For example, it is common for digital balances to exhibit random error in their least significant digit. Three measurements of a single object might read something like 0.9111g, 0.9110g, and 0.9112g.

Characterization[edit]

Measurement errors can be divided into two components: random error and systematic error.[2]

Random error is always present in a measurement. It is caused by inherently unpredictable fluctuations in the readings of a measurement apparatus or in the experimenter’s interpretation of the instrumental reading. Random errors show up as different results for ostensibly the same repeated measurement. They can be estimated by comparing multiple measurements and reduced by averaging multiple measurements.

Systematic error is predictable and typically constant or proportional to the true value. If the cause of the systematic error can be identified, then it usually can be eliminated. Systematic errors are caused by imperfect calibration of measurement instruments or imperfect methods of observation, or interference of the environment with the measurement process, and always affect the results of an experiment in a predictable direction. Incorrect zeroing of an instrument leading to a zero error is an example of systematic error in instrumentation.

The Performance Test Standard PTC 19.1-2005 “Test Uncertainty”, published by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), discusses systematic and random errors in considerable detail. In fact, it conceptualizes its basic uncertainty categories in these terms.

Random error can be caused by unpredictable fluctuations in the readings of a measurement apparatus, or in the experimenter’s interpretation of the instrumental reading; these fluctuations may be in part due to interference of the environment with the measurement process. The concept of random error is closely related to the concept of precision. The higher the precision of a measurement instrument, the smaller the variability (standard deviation) of the fluctuations in its readings.

Sources[edit]

Sources of systematic error[edit]

Imperfect calibration[edit]

Sources of systematic error may be imperfect calibration of measurement instruments (zero error), changes in the environment which interfere with the measurement process and sometimes imperfect methods of observation can be either zero error or percentage error. If you consider an experimenter taking a reading of the time period of a pendulum swinging past a fiducial marker: If their stop-watch or timer starts with 1 second on the clock then all of their results will be off by 1 second (zero error). If the experimenter repeats this experiment twenty times (starting at 1 second each time), then there will be a percentage error in the calculated average of their results; the final result will be slightly larger than the true period.

Distance measured by radar will be systematically overestimated if the slight slowing down of the waves in air is not accounted for. Incorrect zeroing of an instrument leading to a zero error is an example of systematic error in instrumentation.

Systematic errors may also be present in the result of an estimate based upon a mathematical model or physical law. For instance, the estimated oscillation frequency of a pendulum will be systematically in error if slight movement of the support is not accounted for.

Quantity[edit]

Systematic errors can be either constant, or related (e.g. proportional or a percentage) to the actual value of the measured quantity, or even to the value of a different quantity (the reading of a ruler can be affected by environmental temperature). When it is constant, it is simply due to incorrect zeroing of the instrument. When it is not constant, it can change its sign. For instance, if a thermometer is affected by a proportional systematic error equal to 2% of the actual temperature, and the actual temperature is 200°, 0°, or −100°, the measured temperature will be 204° (systematic error = +4°), 0° (null systematic error) or −102° (systematic error = −2°), respectively. Thus the temperature will be overestimated when it will be above zero and underestimated when it will be below zero.

Drift[edit]

Systematic errors which change during an experiment (drift) are easier to detect. Measurements indicate trends with time rather than varying randomly about a mean. Drift is evident if a measurement of a constant quantity is repeated several times and the measurements drift one way during the experiment. If the next measurement is higher than the previous measurement as may occur if an instrument becomes warmer during the experiment then the measured quantity is variable and it is possible to detect a drift by checking the zero reading during the experiment as well as at the start of the experiment (indeed, the zero reading is a measurement of a constant quantity). If the zero reading is consistently above or below zero, a systematic error is present. If this cannot be eliminated, potentially by resetting the instrument immediately before the experiment then it needs to be allowed by subtracting its (possibly time-varying) value from the readings, and by taking it into account while assessing the accuracy of the measurement.

If no pattern in a series of repeated measurements is evident, the presence of fixed systematic errors can only be found if the measurements are checked, either by measuring a known quantity or by comparing the readings with readings made using a different apparatus, known to be more accurate. For example, if you think of the timing of a pendulum using an accurate stopwatch several times you are given readings randomly distributed about the mean. Hopings systematic error is present if the stopwatch is checked against the ‘speaking clock’ of the telephone system and found to be running slow or fast. Clearly, the pendulum timings need to be corrected according to how fast or slow the stopwatch was found to be running.

Measuring instruments such as ammeters and voltmeters need to be checked periodically against known standards.

Systematic errors can also be detected by measuring already known quantities. For example, a spectrometer fitted with a diffraction grating may be checked by using it to measure the wavelength of the D-lines of the sodium electromagnetic spectrum which are at 600 nm and 589.6 nm. The measurements may be used to determine the number of lines per millimetre of the diffraction grating, which can then be used to measure the wavelength of any other spectral line.

Constant systematic errors are very difficult to deal with as their effects are only observable if they can be removed. Such errors cannot be removed by repeating measurements or averaging large numbers of results. A common method to remove systematic error is through calibration of the measurement instrument.

Sources of random error[edit]

The random or stochastic error in a measurement is the error that is random from one measurement to the next. Stochastic errors tend to be normally distributed when the stochastic error is the sum of many independent random errors because of the central limit theorem. Stochastic errors added to a regression equation account for the variation in Y that cannot be explained by the included Xs.

Surveys[edit]

The term «observational error» is also sometimes used to refer to response errors and some other types of non-sampling error.[1] In survey-type situations, these errors can be mistakes in the collection of data, including both the incorrect recording of a response and the correct recording of a respondent’s inaccurate response. These sources of non-sampling error are discussed in Salant and Dillman (1994) and Bland and Altman (1996).[4][5]

These errors can be random or systematic. Random errors are caused by unintended mistakes by respondents, interviewers and/or coders. Systematic error can occur if there is a systematic reaction of the respondents to the method used to formulate the survey question. Thus, the exact formulation of a survey question is crucial, since it affects the level of measurement error.[6] Different tools are available for the researchers to help them decide about this exact formulation of their questions, for instance estimating the quality of a question using MTMM experiments. This information about the quality can also be used in order to correct for measurement error.[7][8]

Effect on regression analysis[edit]

If the dependent variable in a regression is measured with error, regression analysis and associated hypothesis testing are unaffected, except that the R2 will be lower than it would be with perfect measurement.

However, if one or more independent variables is measured with error, then the regression coefficients and standard hypothesis tests are invalid.[9]: p. 187 This is known as attenuation bias.[10]

See also[edit]

- Bias (statistics)

- Cognitive bias

- Correction for measurement error (for Pearson correlations)

- Errors and residuals in statistics

- Error

- Replication (statistics)

- Statistical theory

- Metrology

- Regression dilution

- Test method

- Propagation of uncertainty

- Instrument error

- Measurement uncertainty

- Errors-in-variables models

- Systemic bias

References[edit]

- ^ a b Dodge, Y. (2003) The Oxford Dictionary of Statistical Terms, OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-920613-1

- ^ a b John Robert Taylor (1999). An Introduction to Error Analysis: The Study of Uncertainties in Physical Measurements. University Science Books. p. 94, §4.1. ISBN 978-0-935702-75-0.

- ^ «Systematic error». Merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Salant, P.; Dillman, D. A. (1994). How to conduct your survey. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-01273-4.

- ^ Bland, J. Martin; Altman, Douglas G. (1996). «Statistics Notes: Measurement Error». BMJ. 313 (7059): 744. doi:10.1136/bmj.313.7059.744. PMC 2352101. PMID 8819450.

- ^ Saris, W. E.; Gallhofer, I. N. (2014). Design, Evaluation and Analysis of Questionnaires for Survey Research (Second ed.). Hoboken: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-63461-5.

- ^ DeCastellarnau, A. and Saris, W. E. (2014). A simple procedure to correct for measurement errors in survey research. European Social Survey Education Net (ESS EduNet). Available at: http://essedunet.nsd.uib.no/cms/topics/measurement Archived 2019-09-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Saris, W. E.; Revilla, M. (2015). «Correction for measurement errors in survey research: necessary and possible» (PDF). Social Indicators Research. 127 (3): 1005–1020. doi:10.1007/s11205-015-1002-x. hdl:10230/28341. S2CID 146550566.

- ^ Hayashi, Fumio (2000). Econometrics. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01018-2.

- ^ Angrist, Joshua David; Pischke, Jörn-Steffen (2015). Mastering ‘metrics : the path from cause to effect. Princeton, New Jersey. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-691-15283-7. OCLC 877846199.

The bias generated by this sort of measurement error in regressors is called attenuation bias.

Further reading[edit]

- Cochran, W. G. (1968). «Errors of Measurement in Statistics». Technometrics. 10 (4): 637–666. doi:10.2307/1267450. JSTOR 1267450.

Ошибки, возникающие при обследовании,

можно разделить на два основных типа:

ошибки в выборке и систематические

ошибки.

Ошибка в выборке — разность между

наблюдаемыми значениями количественного

признака и их долгосрочным средним

значением при повторении измерений.

Основой для ее рассмотрения была

концепция выборочного распределения

некоторой статистики, например выборочного

среднего, выборочной доли и тому

подобное. Само понятие выборочного

распределения неразрывно связано с

понятием ошибки в выборке. Названное

распределение существует благодаря

тому, что различные выборки, сформированные

в соответствии с принятым планом

исследования, дают разные оценки

параметра.

Статистика меняется от выборки к выборке

в силу того, что в каждом случае

выборочному отбору подвергается

лишь часть генеральной совокупности.

Соответственно можно определить ошибку

в выборке как разность между наблюдаемыми

значениями количественного признака

и их долгосрочным средним значением

при повторении измерений. Ошибка в

выборке может быть уменьшена путем

увеличения объема выборки.

Систематические

ошибки являются отражением ошибок иного

рода, которые могут возникать и не

при выборочных исследованиях.

Систематическая

ошибка

— ошибка исследования, не связанная с

выборкой. Она может быть вызвана

концептуальными или логическими

ошибками, неправильной интерпретацией

ответов, а также статистическими,

арифметическими, табуляционными,

кодовыми или отчетными ошибками.

Систематическая

ошибка подразделяется на: случайную

и неслучайную.

Случайные

ошибки

дают оценки, отличные от истинного

значения; они могут приводить к отклонениям

и в большую, и в меньшую сторону и имеют

при этом случайный характер.

Неслучайные

систематические ошибки имеют более

тяжкие последствия. Неслучайные

систематические ошибки

приводят

к односторонним отклонениям, Соответственно

для них характерна тенденция к смещению

выборочного значения относительно

параметра совокупности. Систематические

ошибки могут являться следствием

концептуальных или логических ошибок,

неправильной интерпретации ответов, а

также статистических, арифметических,

табуляционных, кодовых или отчетных

ошибок.

Один из авторов писал: «Перечень возможных

бед и напастей с увеличением наших

познаний только расширяется… Многолетняя

работа в определенной области, позволяет

приобрести известный методологический

опыт, который, к сожалению, практически

никогда не становится доступным другим.

Подлинной уверенности в правильности

выработанных подходов нет и быть не

может».

Недостатки

систематических ошибок:

—

не так часты, но и не настолько

подконтрольны, как ошибки в выборке.

При увеличении объема выборки ошибки

в выборке уменьшаются. Сказать то же

самое о систематических ошибках нельзя.

В этом случае они могут, как уменьшаться,

так и возрастать.

—

в систематических ошибках, как

направление, так и величина ошибки

могут оказаться совершенно непредсказуемыми,

в отличие от выборок, где ошибки в выборке

при использовании вероятностных методов

могут быть оценены.

—

приводят к смещению выборочного

значения относительно параметра

совокупности. В

ряде случаев нельзя судить даже о том,

к чему именно приведут, к переоценке

или к недооценке параметра.

—

влияют на достоверность выборочных

оценок. Вызванное

ими смещение может увеличить ошибку

оценки определенных статистик до

такой степени, что оценка доверительного

интервала окажется ошибочной.

Например, одно из исследований, отражающие

финансовое положение потребителей,

направленное оценить уровень накоплений

потребителей, проведенное Иллинойским

университетом, служит наглядным

свидетельством сказанного. В ходе

этого исследования сравнивали полученные

от потребителей сведения об их

финансовых средствах и долгах с известной

информацией, отражающей финансовое

положение потребителей.

Например,

опытное обследование неожиданно

показало, что систематические ошибки

существуют не только в теории, оказалось,

что именно они являются основной

причиной замеченной тенденции к занижению

собранных показателей.

Эта

ошибка не просто присутствовала в данных

обследования, в ряде случаев роль

систематических ошибок была настолько

велика, что

определение

доверительных интервалов по известным

формулам статистики теряло всяческий

смысл. Следует отметить, что

при

увеличении объема выборки величина

этой ошибки только возрастала.

В

некоторых ситуациях даже самые изощренные

выборки не могут избавить от систематических

ошибок.

Особенно

критичными ошибки становятся при работе

с широкомасштабными, хорошо продуманными

вероятностными выборками, т.к. при

увеличении эффективности проектирования

выборки и уменьшении выборочной

дисперсии, эффект систематических

ошибок усиливается. В связи с тем, что

систематические отклонения практически

не зависят от объема выборки, то

сталкиваемся с парадоксальной ситуацией.

Чем эффективнее составлена выборка,

тем большую роль играют систематические

ошибки и тем меньшим смыслом обладают

вычисления по определению доверительного

интервала, в основе которых лежат

обычные формулы.

В

случае исследования, проведенного

Иллинойским университетом, можно было

определить систематическую ошибку,

т.к. в распоряжении исследователей

находились не только результаты опроса,

но и реальные данные, отражающие

финансовое положение потребителей.

Предположим, что подобных данных нет.

Исследователи могут предположить,

что полученные ими ответы не совсем

точны, но как они смогут определить хотя

бы направление вызванного такими

ошибками смещения? То ли респонденты

сознательно завышали уровень своих

сбережений, желая впечатлить

интервьюера, то ли занижали их, боясь,

что реальные цифры могут вызвать

повышенный интерес у сотрудников

Налогового управления. Предположим,

что сам факт неточности приведенных

сведений не вызывает у нас сомнений.

Возникает еще один вопрос: какова

величина этой «неточности»? Завышение

реальной суммы на 10 000 долларов или

ее занижение на 2000? Или наоборот?

Часто

проблема систематических ошибок

оказывается центральной. Два типа

систематических ошибок, отсутствие

ответов одних и некорректные ответы

других участников обследования, могут

обратить результаты исследования на

нет.

Например,

в результате специальных исследований,

проведенных Бюро переписей, выяснилось,

что такие систематические ошибки

могут в десять раз превышать ошибку

выборки. Помимо

прочего, оказалось, что систематическая

ошибка составляет большую часть ошибки

исследования, в то время как случайная

ошибка выборки сведена к минимуму.

Систематические

ошибки могут быть уменьшены, но

уменьшение их связано не столько с

увеличением объема выборки, сколько с

использованием специальных методов. А

для этого необходимо, прежде всего,

осознавать их причины.

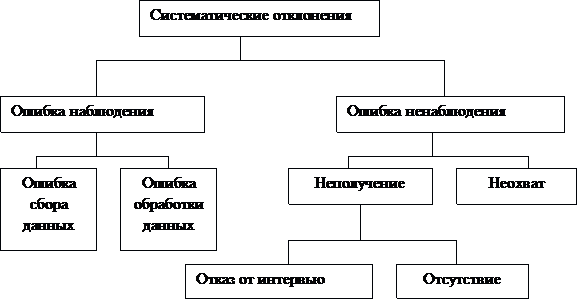

На

рис. 6.1 представлены основные типы

систематических ошибок.

Систематические ошибки делятся на

два основных типа: ошибки, связанные с

неполучением данных (ошибки ненаблюдения),

и ошибки наблюдения.

Ошибки ненаблюдения возникают вследствие

невозможности получения данных от части

элементов обследуемой совокупности и

быть вызваны тем, что часть обследуемой

совокупности не была представлена в

выборке, или же элементы, отобранные

для включения в выборку, не представили

данных.

Ошибки наблюдений возникают вследствие

некорректной информации, полученной

от элементов выборки, они могут возникнуть

и на стадии обработки данных или

формулирования итогового вывода.

По ряду характеристик они представляют

еще более опасность, чем ошибки

ненаблюдения. В случае последних

ошибки этого вида обусловлены неполным

охватом или неполучением данных. О

существовании же ошибок наблюдения

можно и не подозревать.

Рис.

8.1. Виды систематических ошибок

Само

понятие ошибки наблюдения основывается

на предположении о том, что для

количественного признака или признаков

существует некоторое «истинное»

значение. Соответственно ошибка

наблюдения является разностью объявленного

и «истинного» значения. И естественно,

что определение ошибки наблюдения

создает трудности, т.к. при исследовании

задаются той самой величиной, определение

которой является целью исследования.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

2.4. Точность статистического наблюдения

Под точностью статистического наблюдения понимают степень соответствия значения наблюдаемого показателя, вычисленного по материалам обследования, его действительной величине. Расхождение, или разница, между ними называется ошибкой статистического наблюдения.

Различают две группы ошибок:

- ошибки регистрации;

- ошибки репрезентативности.

Ошибки регистрации присущи любому статистическому наблюдению, как сплошному, так и несплошному. Они делятся на случайные ошибки регистрации и систематические ошибки регистрации.

Случайными ошибками регистрации называют ошибки, возникающие вследствие действия случайных факторов. К ним можно отнести различного рода непреднамеренные описки: например, вместо возраста человека «15 лет» указано «5 лет», у Ивановой Марии Петровны в графе пол отмечен «Мужской» и т. п. Такие ошибки легко выявляются методом логического анализа, например, если человеку 8 лет, но имеется высшее образование, а в графе «Семейное положение» указано «Состоит в браке», то, естественно, следует исправить возраст. Если объем исследуемой совокупности велик или велика доля отбора при выборочном наблюдении, случайные ошибки регистрации имеют тенденцию взаимопогашаться вследствие действия закона больших чисел, поскольку ошибки, как правило, разнонаправлены и искажают статистический показатель как в большую, так и в меньшую сторону. При небольшом объеме наблюдения требуется тщательная выверка его результатов — логический анализ данных.

Систематические ошибки регистрации чаще всего имеют однонаправленные искажения: они либо увеличивают, либо уменьшают статистический показатель, и, что характерно, подобная ситуация повторяется от обследования к обследованию. Так, по результатам переписей (практически всех!) число замужних женщин превышает число женатых мужчин — мужчинам приятнее ощущать себя неженатыми, а для женщины как бы «стыдно» быть не замужем. Другой пример, когда человек округляет свой возраст — вместо 32 лет говорит 30, вместо 79-80 и т. п. (это явление широко известно и даже получило свое название — «аккумуляция возрастов»). Систематические ошибки регистрации могут возникать и из-за неточностей измерительных приборов, если сбор информации проводят путем непосредственного наблюдения.

Ошибки репрезентативности присущи только несплошному обследованию. Они также делятся на случайные и систематические ошибки.

Случайные ошибки репрезентативности возникают из-за того, что обследованию подвергается не вся совокупность в целом, а только ее часть, и, следовательно, при несплошном наблюдении они присутствуют всегда. В теории статистики разработаны специальные методы для оценки величин таких ошибок, на их основе для наблюдаемых показателей строят доверительные интервалы, т.д. эти ошибки вычисляются и находятся как бы «под контролем».

Хуже обстоит дело, если наряду со случайными ошибками имеются и ошибки систематические.

Систематические ошибки репрезентативности возникают, если при несплошном наблюдении кардинально нарушаются технологии отбора единиц из генеральной совокупности объектов, но чаще — если в ходе обследования не удается получить информацию обо всех отобранных для наблюдения единицах, например, вследствие отказа отвечать на вопросы анкеты, или если человека не удалось застать дома и т. п.

Ошибки статистического наблюдения для наглядности можно изобразить в виде схемы (рис. 2.1).

Рис.

2.1.

Виды ошибок статистического наблюдения

Для повышения точности наблюдения необходимо:

- правильно разработать формуляр статистического наблюдения: вопросы должны быть четкими, однозначными, не допускающими двойного толкования;

- иметь хорошо обученный персонал для проведения обследования;

- строго придерживаться выбранной технологии обследования (если проводится несплошное наблюдение) и помнить, что если не удается опросить какую-то конкретную единицу, отобранную для наблюдения, замена ее на другую единицу может привести к возникновению систематической ошибки репрезентативности;

- провести логический анализ данных, основанный на логических взаимосвязях показателей, после сбора всей совокупности анкет или формуляров;

- целесообразно провести и арифметический контроль данных, т.д. заново пересчитать расчетные величины, если какие-либо показатели получаются в результате определенных арифметических действий;

- предпринять определенные меры по восстановлению данных при наличии незаполненных анкет или формуляров либо при получении результатов обследования сделать поправку на неответы респондентов.