Среднее арифметическое значение, средняя квадратичная и средняя арифметическая погрешности измеряемой величины

Первой величиной,

которую приходится вычислять при

обработке результатов опытов, является

среднее арифметическое из результатов

ряда измерений, которое определяется

по формуле (6).

Практически число

измерений всегда ограничено, поэтому

среднее арифметическое

не равно

истинному значению измеряемой величины

,

но будет

тем ближе к нему, чем больше число

выполненных измерений .

В теории

вероятностей доказывается, что среднее

арифметическое из результатов отдельных

измерений является наиболее вероятным

значением измеряемой величины. Это

утверждение справедливо при условии,

когда все

измерения равноточные, а распределение

погрешности измерений подчиняется

вышеупомянутому закону распределения—

закону Гаусса.

Если вместо

истинного значения неизвестной величины

использовать среднее арифметическое

,

тогда на

основании равенства (1) имеем:

В (11) погрешность

несколько

отличается от истинной и называется

абсолютной погрешностью единичного

измерения

(12)

Лучшим из критериев

для оценки погрешностей результатов

измерений является средняя квадратичная

погрешность, которая характеризует

степень (меру) рассеяния результатов

отдельных измерений

около среднего

их значения. Для определения

среднеквадратической погрешности

единичных измерений при ограниченном

числе опытов используется формула (7),

которая с учетом (12) записывается в виде:

Средняя квадратическая

погрешность, вычисляемая по формуле

(13), характеризует погрешность единичного

результата из всего ряда n

измерений.

Как уже отмечалось,

при увеличении числа n

измерений наблюдается взаимная

компенсация случайных ошибок. Поэтому

усредненная средняя квадратичная

погрешность,

определяемая по формуле (9) и характеризующая

окончательный результат измерений,

уменьшается при увеличении числаn

повторных

измерений искомой величины. Поскольку

вычисления величины

достаточно громоздки, то в ряде случаев

(если не оговорено в условиях решаемой

задачи) для оценки ошибки, допущенной

при определении средней величины,

пользуются средней арифметической

погрешностью, которая вычисляется как

средняя величина всех величин абсолютных

погрешностей единичных измерений (12),

взятых по модулю:

.

(14)

Так как суммирование

в (14) выполняется без учета знака ,

то формула (14) даёт среднее значение

максимальной возможной погрешности.

Вопрос о том, какой

формулой пользоваться при оценке

измерений, решается при планировании

эксперимента. Считается, что при числе

измерений меньше пяти можно ограничиться

вычислением средней абсолютной

погрешности по формуле (14).

Средняя абсолютная

погрешность даёт возможность указать

пределы (интервал), внутри которых

заключено истинное значение измеряемой

величины.

Сама по себе

абсолютная погрешность не даёт достаточно

наглядного представления о степени

точности измерения, поэтому для оценки

точности результата применяется

относительная погрешность. Относительная

погрешность величины x

при ограниченном числе опытов вычисляется

по формуле:

.

(15)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In statistics, the mean squared error (MSE)[1] or mean squared deviation (MSD) of an estimator (of a procedure for estimating an unobserved quantity) measures the average of the squares of the errors—that is, the average squared difference between the estimated values and the actual value. MSE is a risk function, corresponding to the expected value of the squared error loss.[2] The fact that MSE is almost always strictly positive (and not zero) is because of randomness or because the estimator does not account for information that could produce a more accurate estimate.[3] In machine learning, specifically empirical risk minimization, MSE may refer to the empirical risk (the average loss on an observed data set), as an estimate of the true MSE (the true risk: the average loss on the actual population distribution).

The MSE is a measure of the quality of an estimator. As it is derived from the square of Euclidean distance, it is always a positive value that decreases as the error approaches zero.

The MSE is the second moment (about the origin) of the error, and thus incorporates both the variance of the estimator (how widely spread the estimates are from one data sample to another) and its bias (how far off the average estimated value is from the true value).[citation needed] For an unbiased estimator, the MSE is the variance of the estimator. Like the variance, MSE has the same units of measurement as the square of the quantity being estimated. In an analogy to standard deviation, taking the square root of MSE yields the root-mean-square error or root-mean-square deviation (RMSE or RMSD), which has the same units as the quantity being estimated; for an unbiased estimator, the RMSE is the square root of the variance, known as the standard error.

Definition and basic properties[edit]

The MSE either assesses the quality of a predictor (i.e., a function mapping arbitrary inputs to a sample of values of some random variable), or of an estimator (i.e., a mathematical function mapping a sample of data to an estimate of a parameter of the population from which the data is sampled). The definition of an MSE differs according to whether one is describing a predictor or an estimator.

Predictor[edit]

If a vector of

In other words, the MSE is the mean

In matrix notation,

where

The MSE can also be computed on q data points that were not used in estimating the model, either because they were held back for this purpose, or because these data have been newly obtained. Within this process, known as statistical learning, the MSE is often called the test MSE,[4] and is computed as

Estimator[edit]

The MSE of an estimator

This definition depends on the unknown parameter, but the MSE is a priori a property of an estimator. The MSE could be a function of unknown parameters, in which case any estimator of the MSE based on estimates of these parameters would be a function of the data (and thus a random variable). If the estimator

The MSE can be written as the sum of the variance of the estimator and the squared bias of the estimator, providing a useful way to calculate the MSE and implying that in the case of unbiased estimators, the MSE and variance are equivalent.[5]

Proof of variance and bias relationship[edit]

An even shorter proof can be achieved using the well-known formula that for a random variable

But in real modeling case, MSE could be described as the addition of model variance, model bias, and irreducible uncertainty (see Bias–variance tradeoff). According to the relationship, the MSE of the estimators could be simply used for the efficiency comparison, which includes the information of estimator variance and bias. This is called MSE criterion.

In regression[edit]

In regression analysis, plotting is a more natural way to view the overall trend of the whole data. The mean of the distance from each point to the predicted regression model can be calculated, and shown as the mean squared error. The squaring is critical to reduce the complexity with negative signs. To minimize MSE, the model could be more accurate, which would mean the model is closer to actual data. One example of a linear regression using this method is the least squares method—which evaluates appropriateness of linear regression model to model bivariate dataset,[6] but whose limitation is related to known distribution of the data.

The term mean squared error is sometimes used to refer to the unbiased estimate of error variance: the residual sum of squares divided by the number of degrees of freedom. This definition for a known, computed quantity differs from the above definition for the computed MSE of a predictor, in that a different denominator is used. The denominator is the sample size reduced by the number of model parameters estimated from the same data, (n−p) for p regressors or (n−p−1) if an intercept is used (see errors and residuals in statistics for more details).[7] Although the MSE (as defined in this article) is not an unbiased estimator of the error variance, it is consistent, given the consistency of the predictor.

In regression analysis, «mean squared error», often referred to as mean squared prediction error or «out-of-sample mean squared error», can also refer to the mean value of the squared deviations of the predictions from the true values, over an out-of-sample test space, generated by a model estimated over a particular sample space. This also is a known, computed quantity, and it varies by sample and by out-of-sample test space.

Examples[edit]

Mean[edit]

Suppose we have a random sample of size

which has an expected value equal to the true mean

where

For a Gaussian distribution, this is the best unbiased estimator (i.e., one with the lowest MSE among all unbiased estimators), but not, say, for a uniform distribution.

Variance[edit]

The usual estimator for the variance is the corrected sample variance:

This is unbiased (its expected value is

where

However, one can use other estimators for

then we calculate:

This is minimized when

For a Gaussian distribution, where

Further, while the corrected sample variance is the best unbiased estimator (minimum mean squared error among unbiased estimators) of variance for Gaussian distributions, if the distribution is not Gaussian, then even among unbiased estimators, the best unbiased estimator of the variance may not be

Gaussian distribution[edit]

The following table gives several estimators of the true parameters of the population, μ and σ2, for the Gaussian case.[9]

| True value | Estimator | Mean squared error |

|---|---|---|

|

= the unbiased estimator of the population mean, = the unbiased estimator of the population mean,  |

|

|

= the unbiased estimator of the population variance, = the unbiased estimator of the population variance,  |

|

|

= the biased estimator of the population variance, = the biased estimator of the population variance,  |

|

|

= the biased estimator of the population variance, = the biased estimator of the population variance,  |

|

Interpretation[edit]

An MSE of zero, meaning that the estimator

Values of MSE may be used for comparative purposes. Two or more statistical models may be compared using their MSEs—as a measure of how well they explain a given set of observations: An unbiased estimator (estimated from a statistical model) with the smallest variance among all unbiased estimators is the best unbiased estimator or MVUE (Minimum-Variance Unbiased Estimator).

Both analysis of variance and linear regression techniques estimate the MSE as part of the analysis and use the estimated MSE to determine the statistical significance of the factors or predictors under study. The goal of experimental design is to construct experiments in such a way that when the observations are analyzed, the MSE is close to zero relative to the magnitude of at least one of the estimated treatment effects.

In one-way analysis of variance, MSE can be calculated by the division of the sum of squared errors and the degree of freedom. Also, the f-value is the ratio of the mean squared treatment and the MSE.

MSE is also used in several stepwise regression techniques as part of the determination as to how many predictors from a candidate set to include in a model for a given set of observations.

Applications[edit]

- Minimizing MSE is a key criterion in selecting estimators: see minimum mean-square error. Among unbiased estimators, minimizing the MSE is equivalent to minimizing the variance, and the estimator that does this is the minimum variance unbiased estimator. However, a biased estimator may have lower MSE; see estimator bias.

- In statistical modelling the MSE can represent the difference between the actual observations and the observation values predicted by the model. In this context, it is used to determine the extent to which the model fits the data as well as whether removing some explanatory variables is possible without significantly harming the model’s predictive ability.

- In forecasting and prediction, the Brier score is a measure of forecast skill based on MSE.

Loss function[edit]

Squared error loss is one of the most widely used loss functions in statistics[citation needed], though its widespread use stems more from mathematical convenience than considerations of actual loss in applications. Carl Friedrich Gauss, who introduced the use of mean squared error, was aware of its arbitrariness and was in agreement with objections to it on these grounds.[3] The mathematical benefits of mean squared error are particularly evident in its use at analyzing the performance of linear regression, as it allows one to partition the variation in a dataset into variation explained by the model and variation explained by randomness.

Criticism[edit]

The use of mean squared error without question has been criticized by the decision theorist James Berger. Mean squared error is the negative of the expected value of one specific utility function, the quadratic utility function, which may not be the appropriate utility function to use under a given set of circumstances. There are, however, some scenarios where mean squared error can serve as a good approximation to a loss function occurring naturally in an application.[10]

Like variance, mean squared error has the disadvantage of heavily weighting outliers.[11] This is a result of the squaring of each term, which effectively weights large errors more heavily than small ones. This property, undesirable in many applications, has led researchers to use alternatives such as the mean absolute error, or those based on the median.

See also[edit]

- Bias–variance tradeoff

- Hodges’ estimator

- James–Stein estimator

- Mean percentage error

- Mean square quantization error

- Mean square weighted deviation

- Mean squared displacement

- Mean squared prediction error

- Minimum mean square error

- Minimum mean squared error estimator

- Overfitting

- Peak signal-to-noise ratio

Notes[edit]

- ^ This can be proved by Jensen’s inequality as follows. The fourth central moment is an upper bound for the square of variance, so that the least value for their ratio is one, therefore, the least value for the excess kurtosis is −2, achieved, for instance, by a Bernoulli with p=1/2.

References[edit]

- ^ a b «Mean Squared Error (MSE)». www.probabilitycourse.com. Retrieved 2020-09-12.

- ^ Bickel, Peter J.; Doksum, Kjell A. (2015). Mathematical Statistics: Basic Ideas and Selected Topics. Vol. I (Second ed.). p. 20.

If we use quadratic loss, our risk function is called the mean squared error (MSE) …

- ^ a b Lehmann, E. L.; Casella, George (1998). Theory of Point Estimation (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-98502-2. MR 1639875.

- ^ Gareth, James; Witten, Daniela; Hastie, Trevor; Tibshirani, Rob (2021). An Introduction to Statistical Learning: with Applications in R. Springer. ISBN 978-1071614174.

- ^ Wackerly, Dennis; Mendenhall, William; Scheaffer, Richard L. (2008). Mathematical Statistics with Applications (7 ed.). Belmont, CA, USA: Thomson Higher Education. ISBN 978-0-495-38508-0.

- ^ A modern introduction to probability and statistics : understanding why and how. Dekking, Michel, 1946-. London: Springer. 2005. ISBN 978-1-85233-896-1. OCLC 262680588.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Steel, R.G.D, and Torrie, J. H., Principles and Procedures of Statistics with Special Reference to the Biological Sciences., McGraw Hill, 1960, page 288.

- ^ Mood, A.; Graybill, F.; Boes, D. (1974). Introduction to the Theory of Statistics (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 229.

- ^ DeGroot, Morris H. (1980). Probability and Statistics (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley.

- ^ Berger, James O. (1985). «2.4.2 Certain Standard Loss Functions». Statistical Decision Theory and Bayesian Analysis (2nd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-387-96098-2. MR 0804611.

- ^ Bermejo, Sergio; Cabestany, Joan (2001). «Oriented principal component analysis for large margin classifiers». Neural Networks. 14 (10): 1447–1461. doi:10.1016/S0893-6080(01)00106-X. PMID 11771723.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In statistics, the mean squared error (MSE)[1] or mean squared deviation (MSD) of an estimator (of a procedure for estimating an unobserved quantity) measures the average of the squares of the errors—that is, the average squared difference between the estimated values and the actual value. MSE is a risk function, corresponding to the expected value of the squared error loss.[2] The fact that MSE is almost always strictly positive (and not zero) is because of randomness or because the estimator does not account for information that could produce a more accurate estimate.[3] In machine learning, specifically empirical risk minimization, MSE may refer to the empirical risk (the average loss on an observed data set), as an estimate of the true MSE (the true risk: the average loss on the actual population distribution).

The MSE is a measure of the quality of an estimator. As it is derived from the square of Euclidean distance, it is always a positive value that decreases as the error approaches zero.

The MSE is the second moment (about the origin) of the error, and thus incorporates both the variance of the estimator (how widely spread the estimates are from one data sample to another) and its bias (how far off the average estimated value is from the true value).[citation needed] For an unbiased estimator, the MSE is the variance of the estimator. Like the variance, MSE has the same units of measurement as the square of the quantity being estimated. In an analogy to standard deviation, taking the square root of MSE yields the root-mean-square error or root-mean-square deviation (RMSE or RMSD), which has the same units as the quantity being estimated; for an unbiased estimator, the RMSE is the square root of the variance, known as the standard error.

Definition and basic properties[edit]

The MSE either assesses the quality of a predictor (i.e., a function mapping arbitrary inputs to a sample of values of some random variable), or of an estimator (i.e., a mathematical function mapping a sample of data to an estimate of a parameter of the population from which the data is sampled). The definition of an MSE differs according to whether one is describing a predictor or an estimator.

Predictor[edit]

If a vector of

In other words, the MSE is the mean

In matrix notation,

where

The MSE can also be computed on q data points that were not used in estimating the model, either because they were held back for this purpose, or because these data have been newly obtained. Within this process, known as statistical learning, the MSE is often called the test MSE,[4] and is computed as

Estimator[edit]

The MSE of an estimator

This definition depends on the unknown parameter, but the MSE is a priori a property of an estimator. The MSE could be a function of unknown parameters, in which case any estimator of the MSE based on estimates of these parameters would be a function of the data (and thus a random variable). If the estimator

The MSE can be written as the sum of the variance of the estimator and the squared bias of the estimator, providing a useful way to calculate the MSE and implying that in the case of unbiased estimators, the MSE and variance are equivalent.[5]

Proof of variance and bias relationship[edit]

An even shorter proof can be achieved using the well-known formula that for a random variable

But in real modeling case, MSE could be described as the addition of model variance, model bias, and irreducible uncertainty (see Bias–variance tradeoff). According to the relationship, the MSE of the estimators could be simply used for the efficiency comparison, which includes the information of estimator variance and bias. This is called MSE criterion.

In regression[edit]

In regression analysis, plotting is a more natural way to view the overall trend of the whole data. The mean of the distance from each point to the predicted regression model can be calculated, and shown as the mean squared error. The squaring is critical to reduce the complexity with negative signs. To minimize MSE, the model could be more accurate, which would mean the model is closer to actual data. One example of a linear regression using this method is the least squares method—which evaluates appropriateness of linear regression model to model bivariate dataset,[6] but whose limitation is related to known distribution of the data.

The term mean squared error is sometimes used to refer to the unbiased estimate of error variance: the residual sum of squares divided by the number of degrees of freedom. This definition for a known, computed quantity differs from the above definition for the computed MSE of a predictor, in that a different denominator is used. The denominator is the sample size reduced by the number of model parameters estimated from the same data, (n−p) for p regressors or (n−p−1) if an intercept is used (see errors and residuals in statistics for more details).[7] Although the MSE (as defined in this article) is not an unbiased estimator of the error variance, it is consistent, given the consistency of the predictor.

In regression analysis, «mean squared error», often referred to as mean squared prediction error or «out-of-sample mean squared error», can also refer to the mean value of the squared deviations of the predictions from the true values, over an out-of-sample test space, generated by a model estimated over a particular sample space. This also is a known, computed quantity, and it varies by sample and by out-of-sample test space.

Examples[edit]

Mean[edit]

Suppose we have a random sample of size

which has an expected value equal to the true mean

where

For a Gaussian distribution, this is the best unbiased estimator (i.e., one with the lowest MSE among all unbiased estimators), but not, say, for a uniform distribution.

Variance[edit]

The usual estimator for the variance is the corrected sample variance:

This is unbiased (its expected value is

where

However, one can use other estimators for

then we calculate:

This is minimized when

For a Gaussian distribution, where

Further, while the corrected sample variance is the best unbiased estimator (minimum mean squared error among unbiased estimators) of variance for Gaussian distributions, if the distribution is not Gaussian, then even among unbiased estimators, the best unbiased estimator of the variance may not be

Gaussian distribution[edit]

The following table gives several estimators of the true parameters of the population, μ and σ2, for the Gaussian case.[9]

| True value | Estimator | Mean squared error |

|---|---|---|

|

= the unbiased estimator of the population mean, = the unbiased estimator of the population mean,  |

|

|

= the unbiased estimator of the population variance, = the unbiased estimator of the population variance,  |

|

|

= the biased estimator of the population variance, = the biased estimator of the population variance,  |

|

|

= the biased estimator of the population variance, = the biased estimator of the population variance,  |

|

Interpretation[edit]

An MSE of zero, meaning that the estimator

Values of MSE may be used for comparative purposes. Two or more statistical models may be compared using their MSEs—as a measure of how well they explain a given set of observations: An unbiased estimator (estimated from a statistical model) with the smallest variance among all unbiased estimators is the best unbiased estimator or MVUE (Minimum-Variance Unbiased Estimator).

Both analysis of variance and linear regression techniques estimate the MSE as part of the analysis and use the estimated MSE to determine the statistical significance of the factors or predictors under study. The goal of experimental design is to construct experiments in such a way that when the observations are analyzed, the MSE is close to zero relative to the magnitude of at least one of the estimated treatment effects.

In one-way analysis of variance, MSE can be calculated by the division of the sum of squared errors and the degree of freedom. Also, the f-value is the ratio of the mean squared treatment and the MSE.

MSE is also used in several stepwise regression techniques as part of the determination as to how many predictors from a candidate set to include in a model for a given set of observations.

Applications[edit]

- Minimizing MSE is a key criterion in selecting estimators: see minimum mean-square error. Among unbiased estimators, minimizing the MSE is equivalent to minimizing the variance, and the estimator that does this is the minimum variance unbiased estimator. However, a biased estimator may have lower MSE; see estimator bias.

- In statistical modelling the MSE can represent the difference between the actual observations and the observation values predicted by the model. In this context, it is used to determine the extent to which the model fits the data as well as whether removing some explanatory variables is possible without significantly harming the model’s predictive ability.

- In forecasting and prediction, the Brier score is a measure of forecast skill based on MSE.

Loss function[edit]

Squared error loss is one of the most widely used loss functions in statistics[citation needed], though its widespread use stems more from mathematical convenience than considerations of actual loss in applications. Carl Friedrich Gauss, who introduced the use of mean squared error, was aware of its arbitrariness and was in agreement with objections to it on these grounds.[3] The mathematical benefits of mean squared error are particularly evident in its use at analyzing the performance of linear regression, as it allows one to partition the variation in a dataset into variation explained by the model and variation explained by randomness.

Criticism[edit]

The use of mean squared error without question has been criticized by the decision theorist James Berger. Mean squared error is the negative of the expected value of one specific utility function, the quadratic utility function, which may not be the appropriate utility function to use under a given set of circumstances. There are, however, some scenarios where mean squared error can serve as a good approximation to a loss function occurring naturally in an application.[10]

Like variance, mean squared error has the disadvantage of heavily weighting outliers.[11] This is a result of the squaring of each term, which effectively weights large errors more heavily than small ones. This property, undesirable in many applications, has led researchers to use alternatives such as the mean absolute error, or those based on the median.

See also[edit]

- Bias–variance tradeoff

- Hodges’ estimator

- James–Stein estimator

- Mean percentage error

- Mean square quantization error

- Mean square weighted deviation

- Mean squared displacement

- Mean squared prediction error

- Minimum mean square error

- Minimum mean squared error estimator

- Overfitting

- Peak signal-to-noise ratio

Notes[edit]

- ^ This can be proved by Jensen’s inequality as follows. The fourth central moment is an upper bound for the square of variance, so that the least value for their ratio is one, therefore, the least value for the excess kurtosis is −2, achieved, for instance, by a Bernoulli with p=1/2.

References[edit]

- ^ a b «Mean Squared Error (MSE)». www.probabilitycourse.com. Retrieved 2020-09-12.

- ^ Bickel, Peter J.; Doksum, Kjell A. (2015). Mathematical Statistics: Basic Ideas and Selected Topics. Vol. I (Second ed.). p. 20.

If we use quadratic loss, our risk function is called the mean squared error (MSE) …

- ^ a b Lehmann, E. L.; Casella, George (1998). Theory of Point Estimation (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-98502-2. MR 1639875.

- ^ Gareth, James; Witten, Daniela; Hastie, Trevor; Tibshirani, Rob (2021). An Introduction to Statistical Learning: with Applications in R. Springer. ISBN 978-1071614174.

- ^ Wackerly, Dennis; Mendenhall, William; Scheaffer, Richard L. (2008). Mathematical Statistics with Applications (7 ed.). Belmont, CA, USA: Thomson Higher Education. ISBN 978-0-495-38508-0.

- ^ A modern introduction to probability and statistics : understanding why and how. Dekking, Michel, 1946-. London: Springer. 2005. ISBN 978-1-85233-896-1. OCLC 262680588.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Steel, R.G.D, and Torrie, J. H., Principles and Procedures of Statistics with Special Reference to the Biological Sciences., McGraw Hill, 1960, page 288.

- ^ Mood, A.; Graybill, F.; Boes, D. (1974). Introduction to the Theory of Statistics (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 229.

- ^ DeGroot, Morris H. (1980). Probability and Statistics (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley.

- ^ Berger, James O. (1985). «2.4.2 Certain Standard Loss Functions». Statistical Decision Theory and Bayesian Analysis (2nd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-387-96098-2. MR 0804611.

- ^ Bermejo, Sergio; Cabestany, Joan (2001). «Oriented principal component analysis for large margin classifiers». Neural Networks. 14 (10): 1447–1461. doi:10.1016/S0893-6080(01)00106-X. PMID 11771723.

Представление результатов исследования

В научных публикациях важно представление результатов исследования. Очень часто окончательный результат приводится в следующем виде: M±m, где M – среднее арифметическое, m –ошибка среднего арифметического. Например, 163,7±0,9 см.

Прежде чем разбираться в правилах представления результатов исследования, давайте точно усвоим, что же такое ошибка среднего арифметического.

Ошибка среднего арифметического

Среднее арифметическое, вычисленное на основе выборочных данных (выборочное среднее), как правило, не совпадает с генеральным средним (средним арифметическим генеральной совокупности). Экспериментально проверить это утверждение невозможно, потому что нам неизвестно генеральное среднее. Но если из одной и той же генеральной совокупности брать повторные выборки и вычислять среднее арифметическое, то окажется, что для разных выборок среднее арифметическое будет разным.

Чтобы оценить, насколько выборочное среднее арифметическое отличается от генерального среднего, вычисляется ошибка среднего арифметического или ошибка репрезентативности.

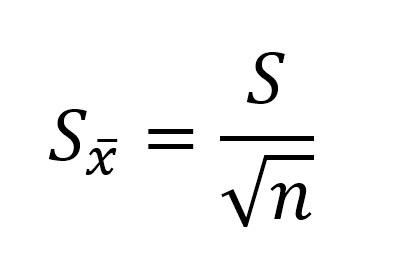

Ошибка среднего арифметического обозначается как m или

Ошибка среднего арифметического рассчитывается по формуле:

где: S — стандартное отклонение, n – объем выборки; Например, если стандартное отклонение равно S=5 см, объем выборки n=36 человек, то ошибка среднего арифметического равна: m=5/6 = 0,833.

Ошибка среднего арифметического показывает, какая ошибка в среднем допускается, если использовать вместо генерального среднего выборочное среднее.

Так как при небольшом объеме выборки истинное значение генерального среднего не может быть определено сколь угодно точно, поэтому при вычислении выборочного среднего арифметического нет смысла оставлять большое число значащих цифр.

Правила записи результатов исследования

- В записи ошибки среднего арифметического оставляем две значащие цифры, если первые цифры в ошибке «1» или «2».

- В остальных случаях в записи ошибки среднего арифметического оставляем одну значащую цифру.

- В записи среднего арифметического положение последней значащей цифры должно соответствовать положению первой значащей цифры в записи ошибки среднего арифметического.

Представление результатов научных исследований

В своей статье «Осторожно, статистика!», опубликованной в 1989 году В.М. Зациорский указал, какие числовые характеристики должны быть представлены в публикации, чтобы она имела научную ценность. Он писал, что исследователь «…должен назвать: 1) среднюю величину (или другой так называемый показатель положения); 2) среднее квадратическое отклонение (или другой показатель рассеяния) и 3) число испытуемых. Без них его публикация научной ценности иметь не будет “с. 52

В научных публикациях в области физической культуры и спорта очень часто окончательный результат приводится в виде: (М±m) (табл.1).

Таблица 1 — Изменение механических свойств латеральной широкой мышцы бедра под воздействием физической нагрузки (n=34)

| Эффективный модуль

упругости (Е), кПа |

Эффективный модуль

вязкости (V), Па с |

|||

| Этап

эксперимента |

Рассл. | Напряж. | Рассл. | Напряж. |

| До ФН | 7,0±0,3 | 17,1±1,4 | 29,7±1,7 | 46±4 |

| После ФН | 7,7±0,3 | 18,7±1,4 | 30,9±2,0 | 53±6 |

Литература

- Высшая математика и математическая статистика: учебное пособие для вузов / Под общ. ред. Г. И. Попова. – М. Физическая культура, 2007.– 368 с.

- Гласс Дж., Стэнли Дж. Статистические методы в педагогике и психологии. М.: Прогресс. 1976.- 495 с.

- Зациорский В.М. Осторожно — статистика! // Теория и практика физической культуры, 1989.- №2.

- Катранов А.Г. Компьютерная обработка данных экспериментальных исследований: Учебное пособие/ А. Г. Катранов, А. В. Самсонова; СПб ГУФК им. П.Ф. Лесгафта. – СПб.: изд-во СПб ГУФК им. П.Ф. Лесгафта, 2005. – 131 с.

- Основы математической статистики: Учебное пособие для ин-тов физ. культ / Под ред. В.С. Иванова.– М.: Физкультура и спорт, 1990. 176 с.

![{displaystyle operatorname {MSE} ({hat {theta }})=operatorname {E} _{theta }left[({hat {theta }}-theta )^{2}right].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9a0e1b3bac58f9ba2d2f4ff8b85b2e35a8f4bf78)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}operatorname {MSE} ({hat {theta }})&=operatorname {E} _{theta }left[({hat {theta }}-theta )^{2}right]\&=operatorname {E} _{theta }left[left({hat {theta }}-operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]+operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]-theta right)^{2}right]\&=operatorname {E} _{theta }left[left({hat {theta }}-operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]right)^{2}+2left({hat {theta }}-operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]right)left(operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]-theta right)+left(operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]-theta right)^{2}right]\&=operatorname {E} _{theta }left[left({hat {theta }}-operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]right)^{2}right]+operatorname {E} _{theta }left[2left({hat {theta }}-operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]right)left(operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]-theta right)right]+operatorname {E} _{theta }left[left(operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]-theta right)^{2}right]\&=operatorname {E} _{theta }left[left({hat {theta }}-operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]right)^{2}right]+2left(operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]-theta right)operatorname {E} _{theta }left[{hat {theta }}-operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]right]+left(operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]-theta right)^{2}&&operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]-theta ={text{const.}}\&=operatorname {E} _{theta }left[left({hat {theta }}-operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]right)^{2}right]+2left(operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]-theta right)left(operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]-operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]right)+left(operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]-theta right)^{2}&&operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]={text{const.}}\&=operatorname {E} _{theta }left[left({hat {theta }}-operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]right)^{2}right]+left(operatorname {E} _{theta }[{hat {theta }}]-theta right)^{2}\&=operatorname {Var} _{theta }({hat {theta }})+operatorname {Bias} _{theta }({hat {theta }},theta )^{2}end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2ac524a751828f971013e1297a33ca1cc4c38cd6)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}operatorname {MSE} ({hat {theta }})&=mathbb {E} [({hat {theta }}-theta )^{2}]\&=operatorname {Var} ({hat {theta }}-theta )+(mathbb {E} [{hat {theta }}-theta ])^{2}\&=operatorname {Var} ({hat {theta }})+operatorname {Bias} ^{2}({hat {theta }})end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/864646cf4426e2b62a3caf9460382eec1a77fe4e)

![{displaystyle operatorname {MSE} left({overline {X}}right)=operatorname {E} left[left({overline {X}}-mu right)^{2}right]=left({frac {sigma }{sqrt {n}}}right)^{2}={frac {sigma ^{2}}{n}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b4647a2cc4c8f9a4c90b628faad2dcf80c4aae84)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}operatorname {MSE} (S_{a}^{2})&=operatorname {E} left[left({frac {n-1}{a}}S_{n-1}^{2}-sigma ^{2}right)^{2}right]\&=operatorname {E} left[{frac {(n-1)^{2}}{a^{2}}}S_{n-1}^{4}-2left({frac {n-1}{a}}S_{n-1}^{2}right)sigma ^{2}+sigma ^{4}right]\&={frac {(n-1)^{2}}{a^{2}}}operatorname {E} left[S_{n-1}^{4}right]-2left({frac {n-1}{a}}right)operatorname {E} left[S_{n-1}^{2}right]sigma ^{2}+sigma ^{4}\&={frac {(n-1)^{2}}{a^{2}}}operatorname {E} left[S_{n-1}^{4}right]-2left({frac {n-1}{a}}right)sigma ^{4}+sigma ^{4}&&operatorname {E} left[S_{n-1}^{2}right]=sigma ^{2}\&={frac {(n-1)^{2}}{a^{2}}}left({frac {gamma _{2}}{n}}+{frac {n+1}{n-1}}right)sigma ^{4}-2left({frac {n-1}{a}}right)sigma ^{4}+sigma ^{4}&&operatorname {E} left[S_{n-1}^{4}right]=operatorname {MSE} (S_{n-1}^{2})+sigma ^{4}\&={frac {n-1}{na^{2}}}left((n-1)gamma _{2}+n^{2}+nright)sigma ^{4}-2left({frac {n-1}{a}}right)sigma ^{4}+sigma ^{4}end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cf22322412b8454c706d78671e5d94208675a6e0)