1. Свойства систематических погрешностей.

Систематическая

ошибка сохраняет свою величину и знак

при повторных измерениях в тех же

условиях. Как правило, систематическая

ошибка – следствие действия какого-либо

одного фактора, она меняется в зависимости

от изменения этого фактора.

Если изучить связь

между величиной систематической ошибки

и значением вызывающего ее фактора,

можно исключить ее введением соответствующей

поправки или используя специальную

методику измерений.

Классические

примеры – введение поправки за температуру

мерных проволок, лент; исключение влияния

остаточной негоризонтальности визирной

осью нивелира соблюдением равенства

расстояний до реек при нивелировании

на станции (нивелирование из середины);

измерение угла при «круге лево» и «круге

право», для исключения коллимационной

ошибки и т.п.

Сложив элементарные

систематические ошибки, получим

систематическую

составляющую истинной ошибки.

Опыт показывает,

что полностью исключить систематические

ошибки невозможно, однако измерения

должны быть организованы так, чтобы

остаточное влияние систематических

ошибок было пренебрегаемо малым, чтобы

систематической составляющей можно

было пренебречь.

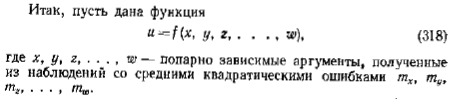

2. Средняя квадратическая погрешность функции зависимых аргументов

.

Свойства

кривой ошибок

Первое свойство.

Для ряда результатов наблюдений с

известным параметром распределения

абсолютные величины случайных ошибок

с заданной вероятностью р не превосходят

определенного предела.

Второе свойство.

Положительные и отрицательные случайные

ошибки равновозможны, т. е. они одинаково

часто встречаются при наблюдениях

Т

ретье

свойство. Среднее арифметическое из

алгебраической суммы значений случайных

ошибок при неограниченном возрастании

числа наблюдений имеет пределом нуль

т. е.

математическое

ожидание случайной ошибки равно нулю.

Четвертое свойство.

Малые по абсолютной величине случайные

ошибки встречаются при наблюдениях

чаще, чем большие.

В подавляющем

большинстве случаев, встречающихся в

практике обработки результатов

наблюдений, случайные ошибки подчиняются

закону нормального распределения

вероятностей. Наглядным проявлением

этого закона являются перечисленные

выше свойства случайных ошибок, которым

почти всегда достаточно хорошо отвечают

исследуемые ряды ошибок наблюдений

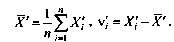

СКО

простой средней

Для

определения mx представим х в виде

Полагая

результаты равноточных наблюдений x1,

х2, • . . , хn

независимыми,

определим mx

по формуле средней квадратической

ошибки функции общего вида

Г

де

В

силу равноточности наблюдений можем

принять

следовательно,

Обозначим

и

окончательно запишем

Билет 18

1.Вес

– относительная характеристика точности

результатов измерений, обратно

пропорциональная квадратам средних

квадратических ошибок результатов

измерений

,

где m

– ср.

Кв. ошібка, с – коэф.пропорциональности

Еденица

веса

– результат измерения, вес которого

равен 1.

2.

#20

1. исследование рядов измерений

-выполняют с целью определить точность

измерений и значений распределения.

Задачами исследования ряда измерении

является

1.отбраковка грубых измерений.

2. определение точности одноименных

измерений

3. если возможно определении системотических

ошибок влияния.

4. определение критерия согласно законов.

Полное исследование ряда измерений

имеет смысл если n˃50

2 ckexfz

1/ известное

2. не известное

2.

Оценка точноти с использованием

доверительных интервалов

Рассмотренный в § 18 способ оценок

неизвестных параметров называется

точечным, а сами оценки — точечными. Он

имеет тот недостаток, что точечная

оценка аi, вообще говоря,

не совпадает с вели

Билет

21

Средняя

квадратическая погрешность. Предельная

и относительная погрешность.

Среднее

арифметическое из случайных погрешностей

не может объективно характеризовать

точность измерений, так как на его

величину оказывают влияние знаки

случайных ошибок (происходит компенсация)

и кроме того она не отражает влияние

отдельных больших по абсолютной величине

ошибок. Поэтому для оценки точности

ряда равноточных измерений l1;

l2; … ln одной

и той же величины Х, сопровождающейся

случайными погрешностями Δ1,

Δ2, , , , , , Δn,

пользуется средней квадратичной ошибкой

m, равной:

Пример:

дан ряд случайных ошибок измерений

некоторой величины: +4, – 2, 0, -4, +3.

Предельной

погрешностью называют такое наибольшее

по абсолютной величине значение случайной

ошибки, которой она может достигнуть

при данных условиях измерений. Установлено,

что случайная ошибка может достигатьудвоенной

средней квадратической ошибки в пяти

случаях из ста, утроенной – в трех из

тысячи. Поэтому за предельную Δпр.

принимают утроенную среднюю квадратическую

ошибку Δпр. = 3m.Относительной

ошибкой называют отношение абсолютной

ошибки к измеренной величине. Она

выражается простой дробью, числитель

которой равен единице. Обычно относительной

ошибкой характеризуют линейные измерения.

Например, измерена линия длиной l=221,16

с абсолютной ошибкой Δ=0,11м.Средняя

квадратическая погрешность арифметической

средины.Арифметическая средина является

наиболее надежным результатом из

многократных измерений. Ее точность

характеризуется ошибкой, величина

которой должна быть меньше заданной

величины, чем количество измерений.

Средняя квадратическая погрешность

арифметической средины определяется

по формуле:Оценка точности по вероятнейшей

погрешности.В большинстве случаев

истинное значение измеряемой величины

не известно, поэтому для вычисления

средней квадратической ошибки используют

отклонения результатов измерений от

их среднего арифметического. Эти

отклонения называют вероятнейшими

погрешностями. Для вычисления средней

квадратической погрешности по вероятнейшим

вычисляют разности между каждым

результатом измерения и арифметической

срединой Х0, эти разности возводят в

квадрат и получают среднюю квадратическую

погрешность по формуле Бесселя:

l1

– Х0 = V1…V12

l2

– Х0 =V2…V2

2

ln

– Хn =Vn…Vn

2

[l]

– nХ0 = [V],

Суммарное уравнение,

Откуда

[l] /n -Х0 = [V]

/n т.к. [l] /n

= Х0, то [V] /n

= 0;

Но n

≠ 0, следовательно [V] = 0.

Среднюю

квадратическую погрешность арифметической

средины по вероятнейшим ошибкам

определяют по формуле:Среднюю квадратичную

ошибку результата по разностям двойных

измерений вычисляют по формуле:Неравноточные

измерения.

СРЕДНЯЯ И ВЕРОЯТНАЯ

ОШИБКИ И ИХ СВЯЗЬ СО СРЕДНЕЙ КВАДРАТИЧЕСКОЙ

ОШИБКОЙ И ПРИМЕНЕНИЕ ИХ В ГЕОДЕЗИИ

В геод. Практике в

качестве критерия точности используют

ср. вероятную, ср. кв-кую и относит.

Ошибки.Ср. ошибка- ср. арифметическое

из абсолютных величин ошибок равноточных

измерений v=[|∆|]/n

Вероятная ошибка-это

такое значение случайной ошибки при

данных условиях измерений, по отношению

к которому ошибки и большие и малые по

абсолютной величине встречаются

одинаково часто. Часто её наз. Серединной,

если этот ряд расположен по убыванию

или возрастанию. Вероятная ошибкой наз.

Абсолютную величину вероятность которой

опр. Из зависимости:

r/m∆=0,5

ф(t)=0.5

t=r/

m∆=0,6745 →

r=0.67

m∆

m=√[∆2]/n

— ф-ла Гауса для равноточн. измер.

[∆]/n=∆=c

m=√[∆2]/n+c2

|∆|≤tα*

m∆;

|∆|≤tα*

m∆/√n;

∆i-c=δi

Теоритическое

значение ср. кв. ошибка явл. Стандарт

или ср. кв. отклонение

Lim√[∆2]/n=σ;

m=σ

Стандарт зависит

от условий измерений, от которых и

зависит предельная ошибка. Тогда ∆пр

не должно превышать значение t*

σ

∆пр‹t*

σ

; ∆пр≤3

σ;

∆пр≤3m.

Св-ва ср. кв. ошибки:

-

На величину ср.

кв. ош. Оказывают наибольшее влияние

на ошибки, которые имеют большее

абсалютное значение. -

Ср. кв. ош. Связана

с предельной простым отношением с

вероятностью Р=0,95 риск ошибки 5% ∆пр≤2m,

с вероятностью Р=0,9973 ∆пр≤3m

эти выражения наз. Допусками. в качестве

допуска Р=0,99 ∆пр=2,5m -

Ср. кв. ошибка

определяется достаточно надежно при

наибольшем числе измерений mm=m/√2r -

Ср. кв. связана со

средней вероятной простым соотношением

m=1.25v

m=1.48r -

Ср. кв. ош. явл.

Состоятельной и несмещённой оценкой

стандарта m2=δ2 -

Ср. кв. ош. 1го

измерения характеризует совместное

влияние на его случайных и систематических

составляющих m=√mΔ2+mθ2

ВЕРОЯТНЕЙШЕЕ

ЧИСЛО ПОЯВЛЕНИЯ СОБЫТИЯ ПРИ МНОГОКРАТНЫХ

ИСПЫТАНИЯХ.

При испытаниях

новых приборов или методов работ, а

также при различных теоретических

расчетах исследователь, естественно,

ставит перед собой вопрос: какое

число появлений ожидаемого события

(при многократных испытаниях) наиболее

возможно, если выполнен определенный

комплекс условий, который в обобщающем

виде характеризуется постоянством в

процессе опыта вероятности появления

события при одном испытании. Конечно,

каждый раз, вычисляя все члены разложения

в формуле (3.1.1) и зная из определения

вероятности, что большая вероятность

порождает большую уверенность в

получении

желаемого результата

опыта, можно определить число появлений

k0 события, соответствующее вероятности

p при числе испытаний n.

K0≈

n p (3.2.1)

где k0 – вероятнейшее

число появления события при многократных

испытаниях. Следует подчеркнуть, что

несмотря на свою простоту формула

(3.2.1) имеет исключительно важное

значение как для последующих

теоретических выкладок, так и в

особенности при решении задач на

появление числа ошибок в заданных

пределах. Основную трудность при

решении практических вопросов с

использованием формулы (3.2.1) составляет

определение вероятности

появления события.

Билет №23

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

«Systematic bias» redirects here. For the sociological and organizational phenomenon, see Systemic bias.

Observational error (or measurement error) is the difference between a measured value of a quantity and its true value.[1] In statistics, an error is not necessarily a «mistake». Variability is an inherent part of the results of measurements and of the measurement process.

Measurement errors can be divided into two components: random and systematic.[2]

Random errors are errors in measurement that lead to measurable values being inconsistent when repeated measurements of a constant attribute or quantity are taken. Systematic errors are errors that are not determined by chance but are introduced by repeatable processes inherent to the system.[3] Systematic error may also refer to an error with a non-zero mean, the effect of which is not reduced when observations are averaged.[citation needed]

Measurement errors can be summarized in terms of accuracy and precision.

Measurement error should not be confused with measurement uncertainty.

Science and experiments[edit]

When either randomness or uncertainty modeled by probability theory is attributed to such errors, they are «errors» in the sense in which that term is used in statistics; see errors and residuals in statistics.

Every time we repeat a measurement with a sensitive instrument, we obtain slightly different results. The common statistical model used is that the error has two additive parts:

- Systematic error which always occurs, with the same value, when we use the instrument in the same way and in the same case.

- Random error which may vary from observation to another.

Systematic error is sometimes called statistical bias. It may often be reduced with standardized procedures. Part of the learning process in the various sciences is learning how to use standard instruments and protocols so as to minimize systematic error.

Random error (or random variation) is due to factors that cannot or will not be controlled. One possible reason to forgo controlling for these random errors is that it may be too expensive to control them each time the experiment is conducted or the measurements are made. Other reasons may be that whatever we are trying to measure is changing in time (see dynamic models), or is fundamentally probabilistic (as is the case in quantum mechanics — see Measurement in quantum mechanics). Random error often occurs when instruments are pushed to the extremes of their operating limits. For example, it is common for digital balances to exhibit random error in their least significant digit. Three measurements of a single object might read something like 0.9111g, 0.9110g, and 0.9112g.

Characterization[edit]

Measurement errors can be divided into two components: random error and systematic error.[2]

Random error is always present in a measurement. It is caused by inherently unpredictable fluctuations in the readings of a measurement apparatus or in the experimenter’s interpretation of the instrumental reading. Random errors show up as different results for ostensibly the same repeated measurement. They can be estimated by comparing multiple measurements and reduced by averaging multiple measurements.

Systematic error is predictable and typically constant or proportional to the true value. If the cause of the systematic error can be identified, then it usually can be eliminated. Systematic errors are caused by imperfect calibration of measurement instruments or imperfect methods of observation, or interference of the environment with the measurement process, and always affect the results of an experiment in a predictable direction. Incorrect zeroing of an instrument leading to a zero error is an example of systematic error in instrumentation.

The Performance Test Standard PTC 19.1-2005 “Test Uncertainty”, published by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), discusses systematic and random errors in considerable detail. In fact, it conceptualizes its basic uncertainty categories in these terms.

Random error can be caused by unpredictable fluctuations in the readings of a measurement apparatus, or in the experimenter’s interpretation of the instrumental reading; these fluctuations may be in part due to interference of the environment with the measurement process. The concept of random error is closely related to the concept of precision. The higher the precision of a measurement instrument, the smaller the variability (standard deviation) of the fluctuations in its readings.

Sources[edit]

Sources of systematic error[edit]

Imperfect calibration[edit]

Sources of systematic error may be imperfect calibration of measurement instruments (zero error), changes in the environment which interfere with the measurement process and sometimes imperfect methods of observation can be either zero error or percentage error. If you consider an experimenter taking a reading of the time period of a pendulum swinging past a fiducial marker: If their stop-watch or timer starts with 1 second on the clock then all of their results will be off by 1 second (zero error). If the experimenter repeats this experiment twenty times (starting at 1 second each time), then there will be a percentage error in the calculated average of their results; the final result will be slightly larger than the true period.

Distance measured by radar will be systematically overestimated if the slight slowing down of the waves in air is not accounted for. Incorrect zeroing of an instrument leading to a zero error is an example of systematic error in instrumentation.

Systematic errors may also be present in the result of an estimate based upon a mathematical model or physical law. For instance, the estimated oscillation frequency of a pendulum will be systematically in error if slight movement of the support is not accounted for.

Quantity[edit]

Systematic errors can be either constant, or related (e.g. proportional or a percentage) to the actual value of the measured quantity, or even to the value of a different quantity (the reading of a ruler can be affected by environmental temperature). When it is constant, it is simply due to incorrect zeroing of the instrument. When it is not constant, it can change its sign. For instance, if a thermometer is affected by a proportional systematic error equal to 2% of the actual temperature, and the actual temperature is 200°, 0°, or −100°, the measured temperature will be 204° (systematic error = +4°), 0° (null systematic error) or −102° (systematic error = −2°), respectively. Thus the temperature will be overestimated when it will be above zero and underestimated when it will be below zero.

Drift[edit]

Systematic errors which change during an experiment (drift) are easier to detect. Measurements indicate trends with time rather than varying randomly about a mean. Drift is evident if a measurement of a constant quantity is repeated several times and the measurements drift one way during the experiment. If the next measurement is higher than the previous measurement as may occur if an instrument becomes warmer during the experiment then the measured quantity is variable and it is possible to detect a drift by checking the zero reading during the experiment as well as at the start of the experiment (indeed, the zero reading is a measurement of a constant quantity). If the zero reading is consistently above or below zero, a systematic error is present. If this cannot be eliminated, potentially by resetting the instrument immediately before the experiment then it needs to be allowed by subtracting its (possibly time-varying) value from the readings, and by taking it into account while assessing the accuracy of the measurement.

If no pattern in a series of repeated measurements is evident, the presence of fixed systematic errors can only be found if the measurements are checked, either by measuring a known quantity or by comparing the readings with readings made using a different apparatus, known to be more accurate. For example, if you think of the timing of a pendulum using an accurate stopwatch several times you are given readings randomly distributed about the mean. Hopings systematic error is present if the stopwatch is checked against the ‘speaking clock’ of the telephone system and found to be running slow or fast. Clearly, the pendulum timings need to be corrected according to how fast or slow the stopwatch was found to be running.

Measuring instruments such as ammeters and voltmeters need to be checked periodically against known standards.

Systematic errors can also be detected by measuring already known quantities. For example, a spectrometer fitted with a diffraction grating may be checked by using it to measure the wavelength of the D-lines of the sodium electromagnetic spectrum which are at 600 nm and 589.6 nm. The measurements may be used to determine the number of lines per millimetre of the diffraction grating, which can then be used to measure the wavelength of any other spectral line.

Constant systematic errors are very difficult to deal with as their effects are only observable if they can be removed. Such errors cannot be removed by repeating measurements or averaging large numbers of results. A common method to remove systematic error is through calibration of the measurement instrument.

Sources of random error[edit]

The random or stochastic error in a measurement is the error that is random from one measurement to the next. Stochastic errors tend to be normally distributed when the stochastic error is the sum of many independent random errors because of the central limit theorem. Stochastic errors added to a regression equation account for the variation in Y that cannot be explained by the included Xs.

Surveys[edit]

The term «observational error» is also sometimes used to refer to response errors and some other types of non-sampling error.[1] In survey-type situations, these errors can be mistakes in the collection of data, including both the incorrect recording of a response and the correct recording of a respondent’s inaccurate response. These sources of non-sampling error are discussed in Salant and Dillman (1994) and Bland and Altman (1996).[4][5]

These errors can be random or systematic. Random errors are caused by unintended mistakes by respondents, interviewers and/or coders. Systematic error can occur if there is a systematic reaction of the respondents to the method used to formulate the survey question. Thus, the exact formulation of a survey question is crucial, since it affects the level of measurement error.[6] Different tools are available for the researchers to help them decide about this exact formulation of their questions, for instance estimating the quality of a question using MTMM experiments. This information about the quality can also be used in order to correct for measurement error.[7][8]

Effect on regression analysis[edit]

If the dependent variable in a regression is measured with error, regression analysis and associated hypothesis testing are unaffected, except that the R2 will be lower than it would be with perfect measurement.

However, if one or more independent variables is measured with error, then the regression coefficients and standard hypothesis tests are invalid.[9]: p. 187 This is known as attenuation bias.[10]

See also[edit]

- Bias (statistics)

- Cognitive bias

- Correction for measurement error (for Pearson correlations)

- Errors and residuals in statistics

- Error

- Replication (statistics)

- Statistical theory

- Metrology

- Regression dilution

- Test method

- Propagation of uncertainty

- Instrument error

- Measurement uncertainty

- Errors-in-variables models

- Systemic bias

References[edit]

- ^ a b Dodge, Y. (2003) The Oxford Dictionary of Statistical Terms, OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-920613-1

- ^ a b John Robert Taylor (1999). An Introduction to Error Analysis: The Study of Uncertainties in Physical Measurements. University Science Books. p. 94, §4.1. ISBN 978-0-935702-75-0.

- ^ «Systematic error». Merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Salant, P.; Dillman, D. A. (1994). How to conduct your survey. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-01273-4.

- ^ Bland, J. Martin; Altman, Douglas G. (1996). «Statistics Notes: Measurement Error». BMJ. 313 (7059): 744. doi:10.1136/bmj.313.7059.744. PMC 2352101. PMID 8819450.

- ^ Saris, W. E.; Gallhofer, I. N. (2014). Design, Evaluation and Analysis of Questionnaires for Survey Research (Second ed.). Hoboken: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-63461-5.

- ^ DeCastellarnau, A. and Saris, W. E. (2014). A simple procedure to correct for measurement errors in survey research. European Social Survey Education Net (ESS EduNet). Available at: http://essedunet.nsd.uib.no/cms/topics/measurement Archived 2019-09-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Saris, W. E.; Revilla, M. (2015). «Correction for measurement errors in survey research: necessary and possible» (PDF). Social Indicators Research. 127 (3): 1005–1020. doi:10.1007/s11205-015-1002-x. hdl:10230/28341. S2CID 146550566.

- ^ Hayashi, Fumio (2000). Econometrics. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01018-2.

- ^ Angrist, Joshua David; Pischke, Jörn-Steffen (2015). Mastering ‘metrics : the path from cause to effect. Princeton, New Jersey. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-691-15283-7. OCLC 877846199.

The bias generated by this sort of measurement error in regressors is called attenuation bias.

Further reading[edit]

- Cochran, W. G. (1968). «Errors of Measurement in Statistics». Technometrics. 10 (4): 637–666. doi:10.2307/1267450. JSTOR 1267450.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

«Systematic bias» redirects here. For the sociological and organizational phenomenon, see Systemic bias.

Observational error (or measurement error) is the difference between a measured value of a quantity and its true value.[1] In statistics, an error is not necessarily a «mistake». Variability is an inherent part of the results of measurements and of the measurement process.

Measurement errors can be divided into two components: random and systematic.[2]

Random errors are errors in measurement that lead to measurable values being inconsistent when repeated measurements of a constant attribute or quantity are taken. Systematic errors are errors that are not determined by chance but are introduced by repeatable processes inherent to the system.[3] Systematic error may also refer to an error with a non-zero mean, the effect of which is not reduced when observations are averaged.[citation needed]

Measurement errors can be summarized in terms of accuracy and precision.

Measurement error should not be confused with measurement uncertainty.

Science and experiments[edit]

When either randomness or uncertainty modeled by probability theory is attributed to such errors, they are «errors» in the sense in which that term is used in statistics; see errors and residuals in statistics.

Every time we repeat a measurement with a sensitive instrument, we obtain slightly different results. The common statistical model used is that the error has two additive parts:

- Systematic error which always occurs, with the same value, when we use the instrument in the same way and in the same case.

- Random error which may vary from observation to another.

Systematic error is sometimes called statistical bias. It may often be reduced with standardized procedures. Part of the learning process in the various sciences is learning how to use standard instruments and protocols so as to minimize systematic error.

Random error (or random variation) is due to factors that cannot or will not be controlled. One possible reason to forgo controlling for these random errors is that it may be too expensive to control them each time the experiment is conducted or the measurements are made. Other reasons may be that whatever we are trying to measure is changing in time (see dynamic models), or is fundamentally probabilistic (as is the case in quantum mechanics — see Measurement in quantum mechanics). Random error often occurs when instruments are pushed to the extremes of their operating limits. For example, it is common for digital balances to exhibit random error in their least significant digit. Three measurements of a single object might read something like 0.9111g, 0.9110g, and 0.9112g.

Characterization[edit]

Measurement errors can be divided into two components: random error and systematic error.[2]

Random error is always present in a measurement. It is caused by inherently unpredictable fluctuations in the readings of a measurement apparatus or in the experimenter’s interpretation of the instrumental reading. Random errors show up as different results for ostensibly the same repeated measurement. They can be estimated by comparing multiple measurements and reduced by averaging multiple measurements.

Systematic error is predictable and typically constant or proportional to the true value. If the cause of the systematic error can be identified, then it usually can be eliminated. Systematic errors are caused by imperfect calibration of measurement instruments or imperfect methods of observation, or interference of the environment with the measurement process, and always affect the results of an experiment in a predictable direction. Incorrect zeroing of an instrument leading to a zero error is an example of systematic error in instrumentation.

The Performance Test Standard PTC 19.1-2005 “Test Uncertainty”, published by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), discusses systematic and random errors in considerable detail. In fact, it conceptualizes its basic uncertainty categories in these terms.

Random error can be caused by unpredictable fluctuations in the readings of a measurement apparatus, or in the experimenter’s interpretation of the instrumental reading; these fluctuations may be in part due to interference of the environment with the measurement process. The concept of random error is closely related to the concept of precision. The higher the precision of a measurement instrument, the smaller the variability (standard deviation) of the fluctuations in its readings.

Sources[edit]

Sources of systematic error[edit]

Imperfect calibration[edit]

Sources of systematic error may be imperfect calibration of measurement instruments (zero error), changes in the environment which interfere with the measurement process and sometimes imperfect methods of observation can be either zero error or percentage error. If you consider an experimenter taking a reading of the time period of a pendulum swinging past a fiducial marker: If their stop-watch or timer starts with 1 second on the clock then all of their results will be off by 1 second (zero error). If the experimenter repeats this experiment twenty times (starting at 1 second each time), then there will be a percentage error in the calculated average of their results; the final result will be slightly larger than the true period.

Distance measured by radar will be systematically overestimated if the slight slowing down of the waves in air is not accounted for. Incorrect zeroing of an instrument leading to a zero error is an example of systematic error in instrumentation.

Systematic errors may also be present in the result of an estimate based upon a mathematical model or physical law. For instance, the estimated oscillation frequency of a pendulum will be systematically in error if slight movement of the support is not accounted for.

Quantity[edit]

Systematic errors can be either constant, or related (e.g. proportional or a percentage) to the actual value of the measured quantity, or even to the value of a different quantity (the reading of a ruler can be affected by environmental temperature). When it is constant, it is simply due to incorrect zeroing of the instrument. When it is not constant, it can change its sign. For instance, if a thermometer is affected by a proportional systematic error equal to 2% of the actual temperature, and the actual temperature is 200°, 0°, or −100°, the measured temperature will be 204° (systematic error = +4°), 0° (null systematic error) or −102° (systematic error = −2°), respectively. Thus the temperature will be overestimated when it will be above zero and underestimated when it will be below zero.

Drift[edit]

Systematic errors which change during an experiment (drift) are easier to detect. Measurements indicate trends with time rather than varying randomly about a mean. Drift is evident if a measurement of a constant quantity is repeated several times and the measurements drift one way during the experiment. If the next measurement is higher than the previous measurement as may occur if an instrument becomes warmer during the experiment then the measured quantity is variable and it is possible to detect a drift by checking the zero reading during the experiment as well as at the start of the experiment (indeed, the zero reading is a measurement of a constant quantity). If the zero reading is consistently above or below zero, a systematic error is present. If this cannot be eliminated, potentially by resetting the instrument immediately before the experiment then it needs to be allowed by subtracting its (possibly time-varying) value from the readings, and by taking it into account while assessing the accuracy of the measurement.

If no pattern in a series of repeated measurements is evident, the presence of fixed systematic errors can only be found if the measurements are checked, either by measuring a known quantity or by comparing the readings with readings made using a different apparatus, known to be more accurate. For example, if you think of the timing of a pendulum using an accurate stopwatch several times you are given readings randomly distributed about the mean. Hopings systematic error is present if the stopwatch is checked against the ‘speaking clock’ of the telephone system and found to be running slow or fast. Clearly, the pendulum timings need to be corrected according to how fast or slow the stopwatch was found to be running.

Measuring instruments such as ammeters and voltmeters need to be checked periodically against known standards.

Systematic errors can also be detected by measuring already known quantities. For example, a spectrometer fitted with a diffraction grating may be checked by using it to measure the wavelength of the D-lines of the sodium electromagnetic spectrum which are at 600 nm and 589.6 nm. The measurements may be used to determine the number of lines per millimetre of the diffraction grating, which can then be used to measure the wavelength of any other spectral line.

Constant systematic errors are very difficult to deal with as their effects are only observable if they can be removed. Such errors cannot be removed by repeating measurements or averaging large numbers of results. A common method to remove systematic error is through calibration of the measurement instrument.

Sources of random error[edit]

The random or stochastic error in a measurement is the error that is random from one measurement to the next. Stochastic errors tend to be normally distributed when the stochastic error is the sum of many independent random errors because of the central limit theorem. Stochastic errors added to a regression equation account for the variation in Y that cannot be explained by the included Xs.

Surveys[edit]

The term «observational error» is also sometimes used to refer to response errors and some other types of non-sampling error.[1] In survey-type situations, these errors can be mistakes in the collection of data, including both the incorrect recording of a response and the correct recording of a respondent’s inaccurate response. These sources of non-sampling error are discussed in Salant and Dillman (1994) and Bland and Altman (1996).[4][5]

These errors can be random or systematic. Random errors are caused by unintended mistakes by respondents, interviewers and/or coders. Systematic error can occur if there is a systematic reaction of the respondents to the method used to formulate the survey question. Thus, the exact formulation of a survey question is crucial, since it affects the level of measurement error.[6] Different tools are available for the researchers to help them decide about this exact formulation of their questions, for instance estimating the quality of a question using MTMM experiments. This information about the quality can also be used in order to correct for measurement error.[7][8]

Effect on regression analysis[edit]

If the dependent variable in a regression is measured with error, regression analysis and associated hypothesis testing are unaffected, except that the R2 will be lower than it would be with perfect measurement.

However, if one or more independent variables is measured with error, then the regression coefficients and standard hypothesis tests are invalid.[9]: p. 187 This is known as attenuation bias.[10]

See also[edit]

- Bias (statistics)

- Cognitive bias

- Correction for measurement error (for Pearson correlations)

- Errors and residuals in statistics

- Error

- Replication (statistics)

- Statistical theory

- Metrology

- Regression dilution

- Test method

- Propagation of uncertainty

- Instrument error

- Measurement uncertainty

- Errors-in-variables models

- Systemic bias

References[edit]

- ^ a b Dodge, Y. (2003) The Oxford Dictionary of Statistical Terms, OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-920613-1

- ^ a b John Robert Taylor (1999). An Introduction to Error Analysis: The Study of Uncertainties in Physical Measurements. University Science Books. p. 94, §4.1. ISBN 978-0-935702-75-0.

- ^ «Systematic error». Merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Salant, P.; Dillman, D. A. (1994). How to conduct your survey. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-01273-4.

- ^ Bland, J. Martin; Altman, Douglas G. (1996). «Statistics Notes: Measurement Error». BMJ. 313 (7059): 744. doi:10.1136/bmj.313.7059.744. PMC 2352101. PMID 8819450.

- ^ Saris, W. E.; Gallhofer, I. N. (2014). Design, Evaluation and Analysis of Questionnaires for Survey Research (Second ed.). Hoboken: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-63461-5.

- ^ DeCastellarnau, A. and Saris, W. E. (2014). A simple procedure to correct for measurement errors in survey research. European Social Survey Education Net (ESS EduNet). Available at: http://essedunet.nsd.uib.no/cms/topics/measurement Archived 2019-09-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Saris, W. E.; Revilla, M. (2015). «Correction for measurement errors in survey research: necessary and possible» (PDF). Social Indicators Research. 127 (3): 1005–1020. doi:10.1007/s11205-015-1002-x. hdl:10230/28341. S2CID 146550566.

- ^ Hayashi, Fumio (2000). Econometrics. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01018-2.

- ^ Angrist, Joshua David; Pischke, Jörn-Steffen (2015). Mastering ‘metrics : the path from cause to effect. Princeton, New Jersey. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-691-15283-7. OCLC 877846199.

The bias generated by this sort of measurement error in regressors is called attenuation bias.

Further reading[edit]

- Cochran, W. G. (1968). «Errors of Measurement in Statistics». Technometrics. 10 (4): 637–666. doi:10.2307/1267450. JSTOR 1267450.

Систематической погрешностью называется составляющая погрешности измерения, остающаяся постоянной или закономерно меняющаяся при повторных измерениях одной и той же величины. При этом предполагается, что систематические погрешности представляют собой определенную функцию неслучайных факторов, состав которых зависит от физических, конструкционных и технологических особенностей средств измерений, условий их применения, а также индивидуальных качеств наблюдателя. Сложные детерминированные закономерности, которым подчиняются систематические погрешности, определяются либо при создании средств измерений и комплектации измерительной аппаратуры, либо непосредственно при подготовке измерительного эксперимента и в процессе его проведения. Совершенствование методов измерения, использование высококачественных материалом, прогрессивная технология — все это позволяет на практике устранить систематические погрешности настолько, что при обработке результатов наблюдений с их наличием зачастую не приходится считаться.

Систематические погрешности принято классифицировать в зависимости от причин их возникновения и по характеру их проявления при измерениях.

В зависимости от причин возникновения рассматриваются четыре вида систематических погрешностей.

1. Погрешности метода, или теоретические погрешности, проистекающие от ошибочности или недостаточной разработки принятой теории метода измерений в целом или от допущенных упрощений при проведении измерений.

Погрешности метода возникают также при экстраполяции свойства, измеренного на ограниченной части некоторого объекта, на весь объект, если последний не обладает однородностью измеряемого свойства. Так, считая диаметр цилиндрического вала равным результату, полученному при измерении в одном сечении и в одном направлении, мы допускаем систематическую погрешность, полностью определяемую отклонениями формы исследуемого вала. При определении плотности вещества по измерениям массы и объема некоторой пробы возникает систематическая погрешность, если проба содержала некоторое количество примесей, а результат измерения принимается за характеристику данного вещества -вообще.

К погрешностям метода следует отнести также те погрешности, которые возникают вследствие влияния измерительной аппаратуры на измеряемые свойства объекта. Подобные явления возникают, например, при измерении длин, когда измерительное усилие используемых приборов достаточно велико, при регистрации быстропротекаюших процессов недостаточно быстродействующей аппаратурой, при измерениях температур жидкостными или газовыми термометрами и т.д.

2. Инструментальные погрешности, зависящие от погрешностей применяемых средств измерений.. Среди инструментальных погрешностей в отдельную группу выделяются погрешности схемы, не связанные с неточностью изготовления средств измерения и обязанные своим происхождением самой структурной схеме средств измерений. Исследование инструментальных погрешностей является предметом специальной дисциплины — теории точности измерительных устройств.

3. Погрешности, обусловленные неправильной установкой и взаимным расположением средств измерения, являющихся частью единого комплекса, несогласованностью их характеристик, влиянием внешних температурных, гравитационных, радиационных и других полей, нестабильностью источников питания, несогласованностью входных и выходных параметров электрических цепей приборов и т.д.

4. Личные погрешности, обусловленные индивидуальными особенностями наблюдателя. Такого рода погрешности вызываются, например, запаздыванием или опережением при регистрации сигнала, неправильным отсчетом десятых долей деления шкалы, асимметрией, возникающей при установке штриха посередине между двумя рисками.

По характеру своего поведения в процессе измерения систематические погрешности подразделяются на постоянные и переменные.

Постоянные систематические погрешности возникают, например, при неправильной установке начала отсчета, неправильной градуировке и юстировке средств измерения и остаются постоянными при всех повторных наблюдениях. Поэтому, если уж они возникли, их очень трудно обнаружить в результатах наблюдений.

Среди переменных систематических погрешностей принято выделять прогрессивные и периодические.

Прогрессивная погрешность возникает, например, при взвешивании, когда одно из коромысел весов находится ближе к источнику тепла, чем другое, поэтому быстрее нагревается и

удлиняется. Это приводит к систематическому сдвигу начала отсчета и к монотонному изменению показаний весов.

Периодическая погрешность присуща измерительным приборам с круговой шкалой, если ось вращения указателя не совпадает с осью шкалы.

Все остальные виды систематических погрешностей принято называть погрешностями, изменяющимися по сложному закону.

В тех случаях, когда при создании средств измерений, необходимых для данной измерительной установки, не удается устранить влияние систематических погрешностей, приходится специально организовывать измерительный процесс и осуществлять математическую обработку результатов. Методы борьбы с систематическими погрешностями заключаются в их обнаружении и последующем исключении путем полной или частичной компенсации. Основные трудности, часто непреодолимые, состоят именно в обнаружении систематических погрешностей, поэтому иногда приходится довольствоваться приближенным их анализом.

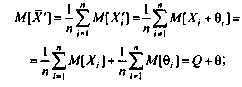

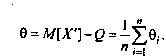

Способы обнаружения систематических погрешностей. Результаты наблюдений, полученные при наличии систематических погрешностей, будем называть неисправленными и в отличие от исправленных снабжать штрихами их обозначения (например, Х1, Х2 и т.д.). Вычисленные в этих условиях средние арифметические значения и отклонения от результатов наблюдений будем также называть неисправленными и ставить штрихи у символов этих величин. Таким образом,

Поскольку неисправленные результаты наблюдений включают в себя систематические погрешности, сумму которых для каждого /-го наблюдения будем обозначать через 8., то их математическое ожидание не совпадает с истинным значением измеряемой величины и отличается от него на некоторую величину 0, называемую систематической погрешностью неисправленного среднего арифметического. Действительно,

Если систематические погрешности постоянны, т.е. 0/ = 0, /=1,2, …, п, то неисправленные отклонения могут быть непосредственно использованы для оценки рассеивания ряда наблюдений. В противном случае необходимо предварительно исправить отдельные результаты измерений, введя в них так называемые поправки, равные систематическим погрешностям по величине и обратные им по знаку:

q = -Oi.

Таким образом, для нахождения исправленного среднего арифметического и оценки его рассеивания относительно истинного значения измеряемой величины необходимо обнаружить систематические погрешности и исключить их путем введения поправок или соответствующей каждому конкретному случаю организации самого измерения. Остановимся подробнее на некоторых способах обнаружения систематических погрешностей.

Постоянные систематические погрешности не влияют на значения случайных отклонений результатов наблюдений от средних арифметических, поэтому никакая математическая обработка результатов наблюдений не может привести к их обнаружению. Анализ таких погрешностей возможен только на основании некоторых априорных знаний об этих погрешностях, получаемых, например, при поверке средств измерений. Измеряемая величина при поверке обычно воспроизводится образцовой мерой, действительное значение которой известно. Поэтому разность между средним арифметическим результатов наблюдения и значением меры с точностью, определяемой погрешностью аттестации меры и случайными погрешностями измерения, равна искомой систематической погрешности.

Одним из наиболее действенных способов обнаружения систематических погрешностей в ряде результатов наблюдений является построение графика последовательности неисправленных значений случайных отклонений результатов наблюдений от средних арифметических.

Рассматриваемый способ обнаружения постоянных систематических погрешностей можно сформулировать следующим образом: если неисправленные отклонения результатов наблюдений резко изменяются при изменении условий наблюдений, то данные результаты содержат постоянную систематическую погрешность, зависящую от условий наблюдений.

Систематические погрешности являются детерминированными величинами, поэтому в принципе всегда могут быть вычислены и исключены из результатов измерений. После исключения систематических погрешностей получаем исправленные средние арифметические и исправленные отклонения результатов наблюдении, которые позволяют оценить степень рассеивания результатов.

Для исправления результатов наблюдений их складывают с поправками, равными систематическим погрешностям по величине и обратными им по знаку. Поправку определяют экспериментально при поверке приборов или в результате специальных исследований, обыкновенно с некоторой ограниченной точностью.

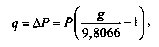

Поправки могут задаваться также в виде формул, по которым они вычисляются для каждого конкретного случая. Например, при измерениях и поверках с помощью образцовых манометров следует вводить поправки к их показаниям на местное значение ускорения свободного падения

где Р — измеряемое давление.

Введением поправки устраняется влияние только одной вполне определенной систематической погрешности, поэтому в результаты измерения зачастую приходится вводить очень большое число поправок. При этом вследствие ограниченной точности определения поправок накапливаются случайные погрешности и дисперсия результата измерения увеличивается.

Систематическая погрешность, остающаяся после введения поправок на ее наиболее существенные составляющие включает в себя ряд элементарных составляющих, называемых неисключенными остатками систематической погрешности. К их числу относятся погрешности:

• определения поправок;

• зависящие от точности измерения влияющих величин, входящих в формулы для определения поправок;

• связанные с колебаниями влияющих величин (температуры окружающей среды, напряжения питания и т.д.).

Перечисленные погрешности малы, и поправки на них не вводятся.