Время прочтения

5 мин

Просмотры 9.7K

Сегодня мы приготовили перевод для тех, кто так же, как автор статьи, при изучении Документации языка программирования Swift избегает главы «Error Handling».

Из статьи вы узнаете:

- что такое оператор if-else и что с ним не так;

- как подружиться с Error Handling;

- когда стоит использовать Try! и Try?

Моя история

Когда я был младше, я начинал изучать документацию языка Swift. Я по несколько раз прочёл все главы, кроме одной: «Error Handling». Отчего-то мне казалось, что нужно быть профессиональным программистом, чтобы понять эту главу.

Я боялся обработки ошибок. Такие слова, как catch, try, throw и throws, казались бессмысленными. Они просто пугали. Неужели они не выглядят устрашающими для человека, который видит их в первый раз? Но не волнуйтесь, друзья мои. Я здесь, чтобы помочь вам.

Как я объяснил своей тринадцатилетней сестре, обработка ошибок – это всего лишь ещё один способ написать блок if-else для отправки сообщения об ошибке.

Сообщение об ошибке от Tesla Motors

Как вы наверняка знаете, у автомобилей Tesla есть функция автопилота. Но, если в работе машины по какой-либо причине происходит сбой, она просит вас взять руль в руки и сообщает об ошибке. В этом уроке мы узнаем, как выводить такое сообщение с помощью Error Handling.

Мы создадим программу, которая будет распознавать такие объекты, как светофоры на улицах. Для этого нужно знать как минимум машинное обучение, векторное исчисление, линейную алгебру, теорию вероятности и дискретную математику. Шутка.

Знакомство с оператором if-else

Чтобы максимально оценить Error Handling в Swift, давайте оглянемся в прошлое. Вот что многие, если не все, начинающие разработчики сделали бы, столкнувшись с сообщением об ошибке:

var isInControl = true

func selfDrive() {

if isInControl {

print("You good, let me ride this car for ya")

} else {

print("Hold the handlebar RIGHT NOW, or you gone die")

}

}

selfDrive() // "You good..."Проблема

Самая большая проблема заключается в удобочитаемости кода, когда блок else становится слишком громоздким. Во-первых, вы не поймёте, содержит ли сама функция сообщение об ошибке, до тех пор, пока не прочитаете функцию от начала до конца или если не назовёте ее, например, selfDriveCanCauseError, что тоже сработает.

Смотрите, функция может убить водителя. Необходимо в недвусмысленных выражениях предупредить свою команду о том, что эта функция опасна и даже может быть смертельной, если невнимательно с ней обращаться.

С другой проблемой можно столкнуться при выполнении некоторых сложных функций или действий внутри блока else. Например:

else {

print("Hold the handle bar Right now...")

// If handle not held within 5 seconds, car will shut down

// Slow down the car

// More code ...

// More code ...

}Блок else раздувается, и работать с ним – все равно что пытаться играть в баскетбол в зимней одежде (по правде говоря, я так и делаю, так как в Корее достаточно холодно). Вы понимаете, о чём я? Это некрасиво и нечитабельно.

Поэтому вы просто могли бы добавить функцию в блок else вместо прямых вызовов.

else {

slowDownTheCar()

shutDownTheEngine()

}Однако при этом сохраняется первая из выделенных мной проблем, плюс нет какого-то определённого способа обозначить, что функция selfDrive() опасна и что с ней нужно обращаться с осторожностью. Поэтому предлагаю погрузиться в Error Handling, чтобы писать модульные и точные сообщения об ошибках.

Знакомство с Error Handling

К настоящему времени вы уже знаете о проблеме If-else с сообщениями об ошибках. Пример выше был слишком простым. Давайте предположим, что есть два сообщения об ошибке:

- вы заблудились

- аккумулятор автомобиля разряжается.

Я собираюсь создать enum, который соответствует протоколу Error.

enum TeslaError: Error {

case lostGPS

case lowBattery

}Честно говоря, я точно не знаю, что делает Error протокол, но при обработке ошибок без этого не обойдешься. Это как: «Почему ноутбук включается, когда нажимаешь на кнопку? Почему экран телефона можно разблокировать, проведя по нему пальцем?»

Разработчики Swift так решили, и я не хочу задаваться вопросом об их мотивах. Я просто использую то, что они для нас сделали. Конечно, если вы хотите разобраться подробнее, вы можете загрузить программный код Swift и проанализировать его самостоятельно – то есть, по нашей аналогии, разобрать ноутбук или iPhone. Я же просто пропущу этот шаг.

Если вы запутались, потерпите еще несколько абзацев. Вы увидите, как все станет ясно, когда TeslaError превратится в функцию.

Давайте сперва отправим сообщение об ошибке без использования Error Handling.

var lostGPS: Bool = true

var lowBattery: Bool = false

func autoDriveTesla() {

if lostGPS {

print("I'm lost, bruh. Hold me tight")

// A lot more code

}

if lowBattery {

print("HURRY! ")

// Loads of code

}

}Итак, если бы я запустил это:

autoDriveTesla() // "HURRY! " Но давайте используем Error Handling. В первую очередь вы должны явно указать, что функция опасна и может выдавать ошибки. Мы добавим к функции ключевое слово throws.

func autoDriveTesla() throws { ... }Теперь функция автоматически говорит вашим товарищам по команде, что autoDriveTesla – особый случай, и им не нужно читать весь блок.

Звучит неплохо? Отлично, теперь пришло время выдавать эти ошибки, когда водитель сталкивается с lostGPA или lowBattery внутри блока Else-If. Помните про enum TeslaError?

func autoDriveTesla() throws {

if lostGPS {

throw TeslaError.lostGPS

}

if lowBattery {

throw TeslaError.lowBattery

}Я вас всех поймаю

Если lostGPS равно true, то функция отправит TeslaError.lostGPS. Но что делать потом? Куда мы будем вставлять это сообщение об ошибке и добавлять код для блока else?

print("Bruh, I'm lost. Hold me tight")Окей, я не хочу заваливать вас информацией, поэтому давайте начнём с того, как выполнить функцию, когда в ней есть ключевое слово throws.

Так как это особый случай, вам необходимо добавлять try внутрь блока do при работе с этой функцией. Вы такие: «Что?». Просто последите за ходом моих мыслей ещё чуть-чуть.

do {

try autoDriveTesla()

}Я знаю, что вы сейчас думаете: «Я очень хочу вывести на экран моё сообщение об ошибке, иначе водитель умрёт».

Итак, куда мы вставим это сообщение об ошибке? Мы знаем, что функция способна отправлять 2 возможных сообщения об ошибке:

- TeslaError.lowBattery

- TeslaError.lostGPS.

Когда функция выдаёт ошибку, вам необходимо её “поймать” и, как только вы это сделаете, вывести на экран соответствующее сообщение. Звучит немного запутанно, поэтому давайте посмотрим.

var lostGPS: Bool = false

var lowBattery: Bool = true

do {

try autoDriveTesla()

} catch TeslaError.lostGPS {

print("Bruh, I'm lost. Hold me tight")

} catch TeslaError.lowBattery {

print("HURRY! ")

}

}

// Results: "HURRY! "

Теперь всё должно стать понятно. Если понятно не всё, вы всегда можете посмотреть моё видео на YouTube.

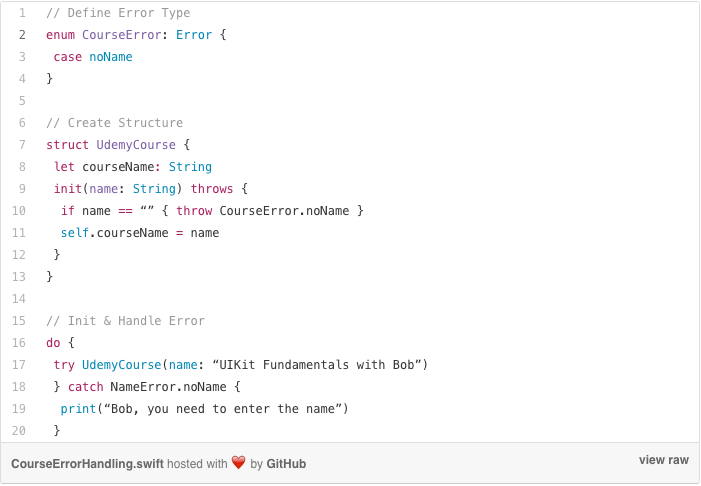

Обработка ошибок с Init

Обработка ошибок может применяться не только к функциям, но и тогда, когда вам нужно инициализировать объект. Допустим, если вы не задали имя курса, то нужно выдавать ошибку.

Если вы введёте tryUdemyCourse(name: «»), появится сообщение об ошибке.

Когда использовать Try! и Try?

Хорошо. Try используется только тогда, когда вы выполняете функцию/инициализацию внутри блока do-catch. Однако если у вас нет цели предупредить пользователя о том, что происходит, выводя сообщение об ошибке на экран, или как-то исправить ее, вам не нужен блок catch.

try?– что это?

Давайте начнём с try? Хотя это не рекомендуется,

let newCourse = try? UdemyCourse("Functional Programming")try? всегда возвращает опциональный объект, поэтому необходимо извлечь newCourse

if let newCourse = newCourse { ... }Если метод init выбрасывает ошибку, как, например

let myCourse = try? UdemyCourse("") // throw NameError.noNameто myCourse будет равен nil.

try! – что это?

В отличие от try? оно возвращает не опциональное значение, а обычное. Например,

let bobCourse = try! UdemyCourse("Practical POP")bobCourse не опционально. Однако, если при методе инициализации выдается ошибка вроде,

let noCourseName = try! UdemyCourse("") // throw NameError.noNameто приложение упадёт. Так же как и в случае с принудительным извлечением с помощью !, никогда не используйте его, если вы не уверены на 101% в том, что происходит.

Ну вот и всё. Теперь вы вместе со мной поняли концепцию Error Handling. Легко и просто! И не нужно становиться профессиональным программистом.

Error handling is the process of responding to and recovering from error conditions in your program. Swift provides first-class support for throwing, catching, propagating, and manipulating recoverable errors at runtime.

Some operations aren’t guaranteed to always complete execution or produce a useful output. Optionals are used to represent the absence of a value, but when an operation fails, it’s often useful to understand what caused the failure, so that your code can respond accordingly.

As an example, consider the task of reading and processing data from a file on disk. There are a number of ways this task can fail, including the file not existing at the specified path, the file not having read permissions, or the file not being encoded in a compatible format. Distinguishing among these different situations allows a program to resolve some errors and to communicate to the user any errors it can’t resolve.

Representing and Throwing Errors¶

In Swift, errors are represented by values of types that conform to the Error protocol. This empty protocol indicates that a type can be used for error handling.

Swift enumerations are particularly well suited to modeling a group of related error conditions, with associated values allowing for additional information about the nature of an error to be communicated. For example, here’s how you might represent the error conditions of operating a vending machine inside a game:

- enum VendingMachineError: Error {

- case invalidSelection

- case insufficientFunds(coinsNeeded: Int)

- case outOfStock

- }

Throwing an error lets you indicate that something unexpected happened and the normal flow of execution can’t continue. You use a throw statement to throw an error. For example, the following code throws an error to indicate that five additional coins are needed by the vending machine:

- throw VendingMachineError.insufficientFunds(coinsNeeded: 5)

Handling Errors¶

When an error is thrown, some surrounding piece of code must be responsible for handling the error—for example, by correcting the problem, trying an alternative approach, or informing the user of the failure.

There are four ways to handle errors in Swift. You can propagate the error from a function to the code that calls that function, handle the error using a do—catch statement, handle the error as an optional value, or assert that the error will not occur. Each approach is described in a section below.

When a function throws an error, it changes the flow of your program, so it’s important that you can quickly identify places in your code that can throw errors. To identify these places in your code, write the try keyword—or the try? or try! variation—before a piece of code that calls a function, method, or initializer that can throw an error. These keywords are described in the sections below.

Note

Error handling in Swift resembles exception handling in other languages, with the use of the try, catch and throw keywords. Unlike exception handling in many languages—including Objective-C—error handling in Swift doesn’t involve unwinding the call stack, a process that can be computationally expensive. As such, the performance characteristics of a throw statement are comparable to those of a return statement.

Propagating Errors Using Throwing Functions¶

To indicate that a function, method, or initializer can throw an error, you write the throws keyword in the function’s declaration after its parameters. A function marked with throws is called a throwing function. If the function specifies a return type, you write the throws keyword before the return arrow (->).

- func canThrowErrors() throws -> String

- func cannotThrowErrors() -> String

A throwing function propagates errors that are thrown inside of it to the scope from which it’s called.

Note

Only throwing functions can propagate errors. Any errors thrown inside a nonthrowing function must be handled inside the function.

In the example below, the VendingMachine class has a vend(itemNamed:) method that throws an appropriate VendingMachineError if the requested item isn’t available, is out of stock, or has a cost that exceeds the current deposited amount:

- struct Item {

- var price: Int

- var count: Int

- }

- class VendingMachine {

- var inventory = [

- «Candy Bar»: Item(price: 12, count: 7),

- «Chips»: Item(price: 10, count: 4),

- «Pretzels»: Item(price: 7, count: 11)

- ]

- var coinsDeposited = 0

- func vend(itemNamed name: String) throws {

- guard let item = inventory[name] else {

- throw VendingMachineError.invalidSelection

- }

- guard item.count > 0 else {

- throw VendingMachineError.outOfStock

- }

- guard item.price <= coinsDeposited else {

- throw VendingMachineError.insufficientFunds(coinsNeeded: item.price — coinsDeposited)

- }

- coinsDeposited -= item.price

- var newItem = item

- newItem.count -= 1

- inventory[name] = newItem

- print(«Dispensing (name)«)

- }

- }

The implementation of the vend(itemNamed:) method uses guard statements to exit the method early and throw appropriate errors if any of the requirements for purchasing a snack aren’t met. Because a throw statement immediately transfers program control, an item will be vended only if all of these requirements are met.

Because the vend(itemNamed:) method propagates any errors it throws, any code that calls this method must either handle the errors—using a do—catch statement, try?, or try!—or continue to propagate them. For example, the buyFavoriteSnack(person:vendingMachine:) in the example below is also a throwing function, and any errors that the vend(itemNamed:) method throws will propagate up to the point where the buyFavoriteSnack(person:vendingMachine:) function is called.

- let favoriteSnacks = [

- «Alice»: «Chips»,

- «Bob»: «Licorice»,

- «Eve»: «Pretzels»,

- ]

- func buyFavoriteSnack(person: String, vendingMachine: VendingMachine) throws {

- let snackName = favoriteSnacks[person] ?? «Candy Bar»

- try vendingMachine.vend(itemNamed: snackName)

- }

In this example, the buyFavoriteSnack(person: vendingMachine:) function looks up a given person’s favorite snack and tries to buy it for them by calling the vend(itemNamed:) method. Because the vend(itemNamed:) method can throw an error, it’s called with the try keyword in front of it.

Throwing initializers can propagate errors in the same way as throwing functions. For example, the initializer for the PurchasedSnack structure in the listing below calls a throwing function as part of the initialization process, and it handles any errors that it encounters by propagating them to its caller.

- struct PurchasedSnack {

- let name: String

- init(name: String, vendingMachine: VendingMachine) throws {

- try vendingMachine.vend(itemNamed: name)

- self.name = name

- }

- }

Handling Errors Using Do-Catch¶

You use a do—catch statement to handle errors by running a block of code. If an error is thrown by the code in the do clause, it’s matched against the catch clauses to determine which one of them can handle the error.

Here is the general form of a do—catch statement:

- do {

- try expression

- statements

- } catch pattern 1 {

- statements

- } catch pattern 2 where condition {

- statements

- } catch pattern 3, pattern 4 where condition {

- statements

- } catch {

- statements

- }

You write a pattern after catch to indicate what errors that clause can handle. If a catch clause doesn’t have a pattern, the clause matches any error and binds the error to a local constant named error. For more information about pattern matching, see Patterns.

For example, the following code matches against all three cases of the VendingMachineError enumeration.

- var vendingMachine = VendingMachine()

- vendingMachine.coinsDeposited = 8

- do {

- try buyFavoriteSnack(person: «Alice», vendingMachine: vendingMachine)

- print(«Success! Yum.»)

- } catch VendingMachineError.invalidSelection {

- print(«Invalid Selection.»)

- } catch VendingMachineError.outOfStock {

- print(«Out of Stock.»)

- } catch VendingMachineError.insufficientFunds(let coinsNeeded) {

- print(«Insufficient funds. Please insert an additional (coinsNeeded) coins.»)

- } catch {

- print(«Unexpected error: (error).»)

- }

- // Prints «Insufficient funds. Please insert an additional 2 coins.»

In the above example, the buyFavoriteSnack(person:vendingMachine:) function is called in a try expression, because it can throw an error. If an error is thrown, execution immediately transfers to the catch clauses, which decide whether to allow propagation to continue. If no pattern is matched, the error gets caught by the final catch clause and is bound to a local error constant. If no error is thrown, the remaining statements in the do statement are executed.

The catch clauses don’t have to handle every possible error that the code in the do clause can throw. If none of the catch clauses handle the error, the error propagates to the surrounding scope. However, the propagated error must be handled by some surrounding scope. In a nonthrowing function, an enclosing do—catch statement must handle the error. In a throwing function, either an enclosing do—catch statement or the caller must handle the error. If the error propagates to the top-level scope without being handled, you’ll get a runtime error.

For example, the above example can be written so any error that isn’t a VendingMachineError is instead caught by the calling function:

- func nourish(with item: String) throws {

- do {

- try vendingMachine.vend(itemNamed: item)

- } catch is VendingMachineError {

- print(«Couldn’t buy that from the vending machine.»)

- }

- }

- do {

- try nourish(with: «Beet-Flavored Chips»)

- } catch {

- print(«Unexpected non-vending-machine-related error: (error)«)

- }

- // Prints «Couldn’t buy that from the vending machine.»

In the nourish(with:) function, if vend(itemNamed:) throws an error that’s one of the cases of the VendingMachineError enumeration, nourish(with:) handles the error by printing a message. Otherwise, nourish(with:) propagates the error to its call site. The error is then caught by the general catch clause.

Another way to catch several related errors is to list them after catch, separated by commas. For example:

- func eat(item: String) throws {

- do {

- try vendingMachine.vend(itemNamed: item)

- } catch VendingMachineError.invalidSelection, VendingMachineError.insufficientFunds, VendingMachineError.outOfStock {

- print(«Invalid selection, out of stock, or not enough money.»)

- }

- }

The eat(item:) function lists the vending machine errors to catch, and its error text corresponds to the items in that list. If any of the three listed errors are thrown, this catch clause handles them by printing a message. Any other errors are propagated to the surrounding scope, including any vending-machine errors that might be added later.

Converting Errors to Optional Values¶

You use try? to handle an error by converting it to an optional value. If an error is thrown while evaluating the try? expression, the value of the expression is nil. For example, in the following code x and y have the same value and behavior:

- func someThrowingFunction() throws -> Int {

- // …

- }

- let x = try? someThrowingFunction()

- let y: Int?

- do {

- y = try someThrowingFunction()

- } catch {

- y = nil

- }

If someThrowingFunction() throws an error, the value of x and y is nil. Otherwise, the value of x and y is the value that the function returned. Note that x and y are an optional of whatever type someThrowingFunction() returns. Here the function returns an integer, so x and y are optional integers.

Using try? lets you write concise error handling code when you want to handle all errors in the same way. For example, the following code uses several approaches to fetch data, or returns nil if all of the approaches fail.

- func fetchData() -> Data? {

- if let data = try? fetchDataFromDisk() { return data }

- if let data = try? fetchDataFromServer() { return data }

- return nil

- }

Disabling Error Propagation¶

Sometimes you know a throwing function or method won’t, in fact, throw an error at runtime. On those occasions, you can write try! before the expression to disable error propagation and wrap the call in a runtime assertion that no error will be thrown. If an error actually is thrown, you’ll get a runtime error.

For example, the following code uses a loadImage(atPath:) function, which loads the image resource at a given path or throws an error if the image can’t be loaded. In this case, because the image is shipped with the application, no error will be thrown at runtime, so it’s appropriate to disable error propagation.

- let photo = try! loadImage(atPath: «./Resources/John Appleseed.jpg»)

Specifying Cleanup Actions¶

You use a defer statement to execute a set of statements just before code execution leaves the current block of code. This statement lets you do any necessary cleanup that should be performed regardless of how execution leaves the current block of code—whether it leaves because an error was thrown or because of a statement such as return or break. For example, you can use a defer statement to ensure that file descriptors are closed and manually allocated memory is freed.

A defer statement defers execution until the current scope is exited. This statement consists of the defer keyword and the statements to be executed later. The deferred statements may not contain any code that would transfer control out of the statements, such as a break or a return statement, or by throwing an error. Deferred actions are executed in the reverse of the order that they’re written in your source code. That is, the code in the first defer statement executes last, the code in the second defer statement executes second to last, and so on. The last defer statement in source code order executes first.

- func processFile(filename: String) throws {

- if exists(filename) {

- let file = open(filename)

- defer {

- close(file)

- }

- while let line = try file.readline() {

- // Work with the file.

- }

- // close(file) is called here, at the end of the scope.

- }

- }

The above example uses a defer statement to ensure that the open(_:) function has a corresponding call to close(_:).

Note

You can use a defer statement even when no error handling code is involved.

Xcode will you give you error message Error in Swift class: Property not initialized at super.init call when you haven’t initialized all the properties introduced by your class before calling the superclass initializer.

Error Example

Here’s an example that will produce the error:

class Vehicle {

var brand: String

init(brand: String) {

self.brand = brand

}

}

class Car: Vehicle {

var model: String

init(model: String, brand: String) {

super.init(brand: brand)

self.model = model

}

}The above code will produce the error Property 'self.model' not initialized at super.init call.

This error will also occur if you have not set the model property at all, for example:

class Car: Vehicle {

var model: String

init(model: String, brand: String) {

super.init(brand: brand)

}

}Let’s go over some of the ways to fix this problem.

Initialize Properties Before Super Call

Initializing the property before the super call will make sense in most cases:

class Car: Vehicle {

var model: String

init(model: String, brand: String) {

self.model = model // Moved this before the super call!

super.init(brand: brand)

}

}This should be the best solution in most cases.

Initialize At Declaration

Another way to solve this problem is to initialize the property when you define it.

This is a good solution if you would like to set a default value:

class Car: Vehicle {

var model: String = "Tesla" // Setting a default value

init(model: String, brand: String) {

super.init(brand: brand)

}

}You won’t see the error if you set a default value for all your properties.

Using Optional Properties

Another way to solve the problem is to make your properties optional by using a question mark ?.

This is a good solution if you don’t want to set values for your properties during initialization.

class Car: Vehicle {

var model: String? // Use a question mark to make this optional

init(model: String, brand: String) {

super.init(brand: brand)

}

}Why Is There A Safety Check

The safety check seems to be pretty pointless, so why does Swift have it?

Let’s take a look at a slightly more complicated example, printing the brand in the init function:

class Vehicle {

var brand: String

init(brand: String) {

self.brand = brand

print(brand) // Added this print statement

}

}

class Car: Vehicle {

var model: String?

init(model: String, brand: String) {

super.init(brand: brand)

}

}

Car(model: "X", brand: "Tesla")This code prints Tesla.

Now what if we wanted to change to the code so that our Car class changed brand in it’s init function:

class Vehicle {

var brand: String

init(brand: String) {

self.brand = brand

print(brand)

}

}

class Car: Vehicle {

var model: String?

init(model: String, brand: String) {

super.init(brand: brand)

brand = "Ford" // Change brand here

}

}

Car(model: "X", brand: "Tesla")What would the behavior of this code be if Swift allowed us to compile? The code would print Tesla still, even though we want the brand to be Ford.

That’s why this safety check exists in Swift.

If you liked this post and want to learn more, check out The Complete iOS Developer Bootcamp. Speed up your learning curve — hundreds of students have already joined. Thanks for reading!

Обработка ошибок

Обработка ошибок — это процесс реагирования на возникновение ошибок и восстановление после появления ошибок в программе. Swift предоставляет первоклассную поддержку при генерации, вылавливании и переносе ошибок, устранении ошибок во время выполнения программы.

Некоторые операции не всегда гарантируют полное выполнение или конечный результат. Опционалы используются для обозначения отсутствия значения, но когда случается сбой, важно понять, что вызвало сбой, для того, чтобы соответствующим образом изменить код.

В качестве примера, рассмотрим задачу считывания и обработки данных из файла на диске. Задача может провалиться по нескольким причинам, в том числе: файл не существует по указанному пути, или файл не имеет разрешение на чтение, или файл не закодирован в необходимом формате. Отличительные особенности этих различных ситуаций позволяют программе решать некоторые ошибки самостоятельно и сообщать пользователю какие ошибки она не может решить сама.

Отображение и генерация ошибок

В Swift ошибки отображаются значениями типов, которые соответствуют протоколу Error. Этот пустой протокол является индикатором того, что это перечисление может быть использовано для обработки ошибок.

Перечисления в Swift особенно хорошо подходят для группировки схожих между собой условий возникновения ошибок и соответствующих им значений, что позволяет получить дополнительную информацию о природе самой ошибки. Например, вот как отображаются условия ошибки работы торгового автомата внутри игры:

enum VendingMachineError: Error {

case invalidSelection

case insufficientFunds(coinsNeeded: Int)

case outOfStock

}Генерация ошибки позволяет указать, что произошло что-то неожиданное и обычное выполнение программы не может продолжаться. Для того чтобы «сгенерировать» ошибку, вы используете инструкцию throw. Например, следующий код генерирует ошибку, указывая, что пять дополнительных монет нужны торговому автомату:

throw VendingMachineError.insufficientFunds(coinsNeeded: 5)Обработка ошибок

Когда генерируется ошибка, то фрагмент кода, окружающий ошибку, должен быть ответственным за ее обработку: например, он должен исправить ее, или испробовать альтернативный подход, или просто информировать пользователя о неудачном исполнении кода.

В Swift существует четыре способа обработки ошибок. Вы можете передать (propagate) ошибку из функции в код, который вызывает саму эту функцию, обработать ошибку, используя инструкцию do-catch, обработать ошибку, как значение опционала, или можно поставить утверждение, что ошибка в данном случае исключена. Каждый вариант будет рассмотрен далее.

Когда функция генерирует ошибку, последовательность выполнения вашей программы меняется, поэтому важно сразу обнаружить место в коде, которое может генерировать ошибки. Для того, чтобы выяснить где именно это происходит, напишите ключевое слово try — или варианты try? или try!— до куска кода, вызывающего функцию, метод или инициализатор, который может генерировать ошибку. Эти ключевые слова описываются в следующем параграфе.

Заметка

Обработка ошибок в Swift напоминает обработку исключений (exceptions) в других языках, с использованием ключевых слов try, catch и throw. В отличие от обработки исключений во многих языках, в том числе и в Objective-C- обработка ошибок в Swift не включает разворачивание стека вызовов, то есть процесса, который может быть дорогим в вычислительном отношении. Таким образом, производительные характеристики инструкции throw сопоставимы с характеристиками оператора return.

Передача ошибки с помощью генерирующей функции

Чтобы указать, что функция, метод или инициализатор могут генерировать ошибку, вам нужно написать ключевое слово throws в реализации функции после ее параметров. Функция, отмеченная throws называется генерирующей функцией. Если у функции установлен возвращаемый тип, то вы пишете ключевое слово throws перед стрелкой возврата (->).

func canThrowErrors() throws -> String

func cannotThrowErrors() -> StringГенерирующая функция передает ошибки, которые возникают внутри нее в область вызова этой функции.

Заметка

Только генерирующая ошибку функция может передавать ошибки. Любые ошибки, сгенерированные внутри non-throwing функции, должны быть обработаны внутри самой функции.

В приведенном ниже примере VendingMachine класс имеет vend(itemNamed: ) метод, который генерирует соответствующую VendingMachineError, если запрошенный элемент недоступен, его нет в наличии, или имеет стоимость, превышающую текущий депозит:

struct Item {

var price: Int

var count: Int

}

class VendingMachine {

var inventory = [

"Candy Bar": Item(price: 12, count: 7),

"Chips": Item(price: 10, count: 4),

"Pretzels": Item(price: 7, count: 11)

]

var coinsDeposited = 0

func vend(itemNamed name: String) throws {

guard let item = inventory[name] else {

throw VendingMachineError.invalidSelection

}

guard item.count > 0 else {

throw VendingMachineError.outOfStock

}

guard item.price <= coinsDeposited else {

throw VendingMachineError.insufficientFunds(coinsNeeded: item.price - coinsDeposited)

}

coinsDeposited -= item.price

var newItem = item

newItem.count -= 1

inventory[name] = newItem

print("Dispensing (name)")

}

}Реализация vend(itemNamed: ) метода использует оператор guard для раннего выхода из метода и генерации соответствующих ошибок, если какое-либо требование для приобретения закуски не будет выполнено. Потому что инструкция throw мгновенно изменяет управление программой, и выбранная позиция будет куплена, только если все эти требования будут выполнены.

Поскольку vend(itemNamed: ) метод передает все ошибки, которые он генерирует, вызывающему его коду, то они должны быть обработаны напрямую, используя оператор do-catch, try? или try!, или должны быть переданы дальше. Например, buyFavoriteSnack(person:vendingMachine: ) в примере ниже — это тоже генерирующая функция, и любые ошибки, которые генерирует метод vend(itemNamed: ), будут переноситься до точки, где будет вызываться функция buyFavoriteSnack(person:vendingMachine: ).

let favoriteSnacks = [

"Alice": "Chips",

"Bob": "Licorice",

"Eve": "Pretzels"

]

func buyFavoriteSnack(person: String, vendingMachine: VendingMachine) throws {

let snackName = favoriteSnacks[person] ?? "Candy Bar"

try vendingMachine.vend(itemNamed: snackName)

}В этом примере, функция buyFavoriteSnack(person:vendingMachine: ) подбирает любимые закуски данного человека и пытается их купить, вызывая vend(itemNamed: ) метод. Поскольку метод vend(itemNamed: ) может сгенерировать ошибку, он вызывается с ключевым словом try перед ним.

Генерирующие ошибку инициализаторы могут распространять ошибки таким же образом, как генерирующие ошибку функции. Например, инициализатор структуры PurchasedSnack в списке ниже вызывает генерирующую ошибку функции как часть процесса инициализации, и он обрабатывает любые ошибки, с которыми сталкивается, путем распространения их до вызывающего его объекта.

struct PurchasedSnack {

let name: String

init(name: String, vendingMachine: VendingMachine) throws {

try vendingMachine.vend(itemNamed: name)

self.name = name

}

}

Обработка ошибок с использованием do-catch

Используйте инструкцию do-catch для обработки ошибок, запуская блок кода. Если выдается ошибка в коде условия do, она соотносится с условием catch для определения того, кто именно сможет обработать ошибку.

Вот общий вид условия do-catch:

do {

try выражение

выражение

} catch шаблон 1 {

выражение

} catch шаблон 2 where условие {

выражение

} catch шаблон 3, шаблон 4 where условие {

выражение

} catch {

выражение

}Вы пишете шаблон после ключевого слова catch, чтобы указать какие ошибки могут обрабатываться данным пунктом этого обработчика. Если условие catch не имеет своего шаблона, то оно подходит под любые ошибки и связывает ошибки к локальной константе error. Более подробно о соответствии шаблону см. Шаблоны.

Например, следующий код обрабатывает все три случая в перечислении VendingMachineError, но все другие ошибки должны быть обработаны окружающей областью:

var vendingMachine = VendingMachine()

vendingMachine.coinsDeposited = 8

do {

try buyFavoriteSnack(person: "Alice", vendingMachine: vendingMachine)

} catch VendingMachineError.invalidSelection {

print("Ошибка выбора.")

} catch VendingMachineError.outOfStock {

print("Нет в наличии.")

} catch VendingMachineError.insufficientFunds(let coinsNeeded) {

print("Недостаточно средств. Пожалуйста вставьте еще (coinsNeeded) монетки.")

} catch {

print("Неожиданная ошибка: (error).")

}

// Выведет "Недостаточно средств. Пожалуйста вставьте еще 2 монетки.В приведенном выше примере, buyFavoriteSnack(person:vendingMachine: ) функция вызывается в выражении try, потому что она может сгенерировать ошибку. Если генерируется ошибка, выполнение немедленно переносится в условия catch, которые принимают решение о продолжении передачи ошибки. Если ошибка не генерируется, остальные операторы do выполняются.

В условии catch не нужно обрабатывать все возможные ошибки, которые может вызвать код в условии do. Если ни одно из условий catch не обрабатывает ошибку, ошибка распространяется на окружающую область. Однако распространяемая ошибка должна обрабатываться некоторой внешней областью. В функции nonthrowing условие включения do-catch должно обрабатывать ошибку. В функции throwing либо включающая условие do-catch, либо вызывающая сторона должна обрабатывать ошибку. Если ошибка распространяется на область верхнего уровня без обработки, вы получите ошибку исполнения.

Например, приведенный ниже пример можно записать так, чтобы любая ошибка, которая не является VendingMachineError, вместо этого захватывалась вызывающей функцией:

func nourish(with item: String) throws {

do {

try vendingMachine.vend(itemNamed: item)

} catch is VendingMachineError {

print("Некорректный вывод, нет в наличии или недостаточно денег.")

}

}

do {

try nourish(with: "Beet-Flavored Chips")

} catch {

print("Unexpected non-vending-machine-related error: (error)")

}

// Выведет "Некорректный вывод, нет в наличии или недостаточно денег."В nourish(with: ), если vend(itemNamed : ) выдает ошибку, которая является одним из кейсов перечисления VendingMachineError, nourish(with: ) обрабатывает ошибку, печатая сообщение. В противном случае, nourish(with: ) распространяет ошибку на свое место вызова. Ошибка затем попадает в общее условие catch.

Преобразование ошибок в опциональные значения

Вы можете использовать try? для обработки ошибки, преобразовав ее в опциональное значение. Если ошибка генерируется при условии try?, то значение выражения вычисляется как nil. Например, в следующем коде x и y имеют одинаковые значения и поведение:

func someThrowingFunction() throws -> Int {

// ...

}

let x = try? someThrowingFunction()

let y: Int?

do {

y = try someThrowingFunction()

} catch {

y = nil

}Если someThrowingFunction() генерирует ошибку, значение x и y равно nil. В противном случае значение x и y — это возвращаемое значение функции. Обратите внимание, что x и y являются опциональными, независимо от того какой тип возвращает функция someThrowingFunction().

Использование try? позволяет написать краткий код обработки ошибок, если вы хотите обрабатывать все ошибки таким же образом. Например, следующий код использует несколько попыток для извлечения данных или возвращает nil, если попытки неудачные.

func fetchData() -> Data? {

if let data = try? fetchDataFromDisk() { return data }

if let data = try? fetchDataFromServer() { return data }

return nil

}

Запрет на передачу ошибок

Иногда вы знаете, что функции throw или методы не сгенерируют ошибку во время исполнения. В этих случаях, вы можете написать try! перед выражением для запрета передачи ошибки и завернуть вызов в утверждение того, что ошибка точно не будет сгенерирована. Если ошибка на самом деле сгенерирована, вы получите сообщение об ошибке исполнения.

Например, следующий код использует loadImage(atPath: ) функцию, которая загружает ресурс изображения по заданному пути или генерирует ошибку, если изображение не может быть загружено. В этом случае, поскольку изображение идет вместе с приложением, сообщение об ошибке не будет сгенерировано во время выполнения, поэтому целесообразно отключить передачу ошибки.

let photo = try! loadImage(atPath: "./Resources/John Appleseed.jpg")Установка действий по очистке (Cleanup)

Вы используете оператор defer для выполнения набора инструкций перед тем как исполнение кода оставит текущий блок. Это позволяет сделать любую необходимую очистку, которая должна быть выполнена, независимо от того, как именно это произойдет — либо он покинет из-за сгенерированной ошибки или из-за оператора, такого как break или return. Например, вы можете использовать defer, чтобы удостовериться, что файл дескрипторов закрыт и выделенная память вручную освобождена.

Оператор defer откладывает выполнение, пока не происходит выход из текущей области. Этот оператор состоит из ключевого слова defer и выражений, которые должны быть выполнены позже. Отложенные выражения могут не содержать кода, изменяющего контроль исполнения изнутри наружу, при помощи таких операторов как break или return, или просто генерирующего ошибку. Отложенные действия выполняются в обратном порядке, как они указаны, то есть, код в первом операторе defer выполняется после кода второго, и так далее.

func processFile(filename: String) throws {

if exists(filename) {

let file = open(filename)

defer {

close(file)

}

while let line = try file.readline() {

// работаем с файлом.

}

// close(file) вызывается здесь, в конце зоны видимости.

}

}Приведенный выше пример использует оператор defer, чтобы удостовериться, что функция open(_: ) имеет соответствующий вызов и для close(_: ).

Заметка

Вы можете использовать оператор defer, даже если не используете кода обработки ошибок.

Если вы нашли ошибку, пожалуйста, выделите фрагмент текста и нажмите Ctrl+Enter.

Swift 2 introduced error handling by way of the

throws, do, try and catch keywords.

It was designed to work hand-in-hand with

Cocoa error handling conventions,

such that any type conforming to the ErrorProtocol protocol

(since renamed to Error)

was implicitly bridged to NSError and

Objective-C methods with an NSError** parameter,

were imported by Swift as throwing methods.

- (NSURL *)replaceItemAtURL:(NSURL *)url

options:(NSFileVersionReplacingOptions)options

error:(NSError * _Nullable *)error;

For the most part,

these changes offered a dramatic improvement over the status quo

(namely, no error handling conventions in Swift at all).

However, there were still a few gaps to fill

to make Swift errors fully interoperable with Objective-C types.

as described by Swift Evolution proposal

SE-0112: “Improved NSError Bridging”.

Not long after these refinements landed in Swift 3,

the practice of declaring errors in enumerations

had become idiomatic.

Yet for how familiar we’ve all become with

Error (née ErrorProtocol),

surprisingly few of us are on a first-name basis with

the other error protocols to come out of SE-0112.

Like, when was the last time you came across LocalizedError in the wild?

How about RecoverableError?

CustomNSError qu’est-ce que c’est?

At the risk of sounding cliché,

you might say that these protocols are indeed pretty obscure,

and there’s a good chance you haven’t heard of them:

LocalizedError-

A specialized error that provides

localized messages describing the error and why it occurred. RecoverableError-

A specialized error that may be recoverable

by presenting several potential recovery options to the user. CustomNSError-

A specialized error that provides a

domain, error code, and user-info dictionary.

If you haven’t heard of any of these until now,

you may be wondering when you’d ever use them.

Well, as the adage goes,

“There’s no time like the present”.

This week on NSHipster,

we’ll take a quick look at each of these Swift Foundation error protocols

and demonstrate how they can make your code —

if not less error-prone —

then more enjoyable in its folly.

Communicating Errors to the User

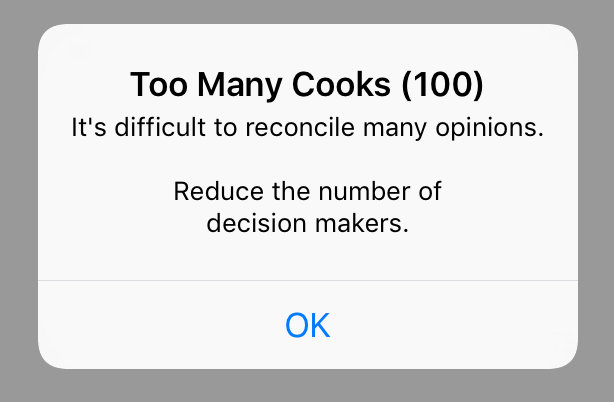

Too many cooks spoil the broth.

Consider the following Broth type

with a nested Error enumeration

and an initializer that takes a number of cooks

and throws an error if that number is inadvisably large:

struct Broth {

enum Error {

case tooManyCooks(Int)

}

init(numberOfCooks: Int) throws {

precondition(numberOfCooks > 0)

guard numberOfCooks < redacted else {

throw Error.tooManyCooks(numberOfCooks)

}

// ... proceed to make broth

}

}

If an iOS app were to communicate an error

resulting from broth spoiled by multitudinous cooks,

it might do so

with by presenting a UIAlertController

in a catch statement like this:

import UIKit

class ViewController: UIViewController {

override func viewDidAppear(_ animated: Bool) {

super.viewDidAppear(animated)

do {

self.broth = try Broth(numberOfCooks: 100)

} catch let error as Broth.Error {

let title: String

let message: String

switch error {

case .tooManyCooks(let numberOfCooks):

title = "Too Many Cooks ((numberOfCooks))"

message = """

It's difficult to reconcile many opinions.

Reduce the number of decision makers.

"""

}

let alertController =

UIAlertController(title: title,

message: message,

preferredStyle: .alert)

alertController.addAction(

UIAlertAction(title: "OK",

style: .default)

)

self.present(alertController, animated: true, completion: nil)

} catch {

// handle other errors...

}

}

}

Such an implementation, however,

is at odds with well-understood boundaries between models and controllers.

Not only does it create bloat in the controller,

it also doesn’t scale to handling multiple errors

or handling errors in multiple contexts.

To reconcile these anti-patterns,

let’s turn to our first Swift Foundation error protocol.

Adopting the LocalizedError Protocol

The LocalizedError protocol inherits the base Error protocol

and adds four instance property requirements.

protocol LocalizedError : Error {

var errorDescription: String? { get }

var failureReason: String? { get }

var recoverySuggestion: String? { get }

var helpAnchor: String? { get }

}

These properties map 1:1 with familiar NSError userInfo keys.

| Requirement | User Info Key |

|---|---|

errorDescription |

NSLocalizedDescriptionKey |

failureReason |

NSLocalizedFailureReasonErrorKey |

recoverySuggestion |

NSLocalizedRecoverySuggestionErrorKey |

helpAnchor |

NSHelpAnchorErrorKey |

Let’s take another pass at our nested Broth.Error type

and see how we might refactor error communication from the controller

to instead be concerns of LocalizedError conformance.

import Foundation

extension Broth.Error: LocalizedError {

var errorDescription: String? {

switch self {

case .tooManyCooks(let numberOfCooks):

return "Too Many Cooks ((numberOfCooks))"

}

}

var failureReason: String? {

switch self {

case .tooManyCooks:

return "It's difficult to reconcile many opinions."

}

}

var recoverySuggestion: String? {

switch self {

case .tooManyCooks:

return "Reduce the number of decision makers."

}

}

}

Using switch statements may be overkill

for a single-case enumeration such as this,

but it demonstrates a pattern that can be extended

for more complex error types.

Note also how pattern matching is used

to bind the numberOfCooks constant to the associated value

only when it’s necessary.

Now we can

import UIKit

class ViewController: UIViewController {

override func viewDidAppear(_ animated: Bool) {

super.viewDidAppear(animated)

do {

try makeBroth(numberOfCooks: 100)

} catch let error as LocalizedError {

let title = error.errorDescription

let message = [

error.failureReason,

error.recoverySuggestion

].compactMap { $0 }

.joined(separator: "nn")

let alertController =

UIAlertController(title: title,

message: message,

preferredStyle: .alert)

alertController.addAction(

UIAlertAction(title: "OK",

style: .default)

)

self.present(alertController, animated: true, completion: nil)

} catch {

// handle other errors...

}

}

}

If that seems like a lot of work just to communicate an error to the user…

you might be onto something.

Although UIKit borrowed many great conventions and idioms from AppKit,

error handling wasn’t one of them.

By taking a closer look at what was lost in translation,

we’ll finally have the necessary context to understand

the two remaining error protocols to be discussed.

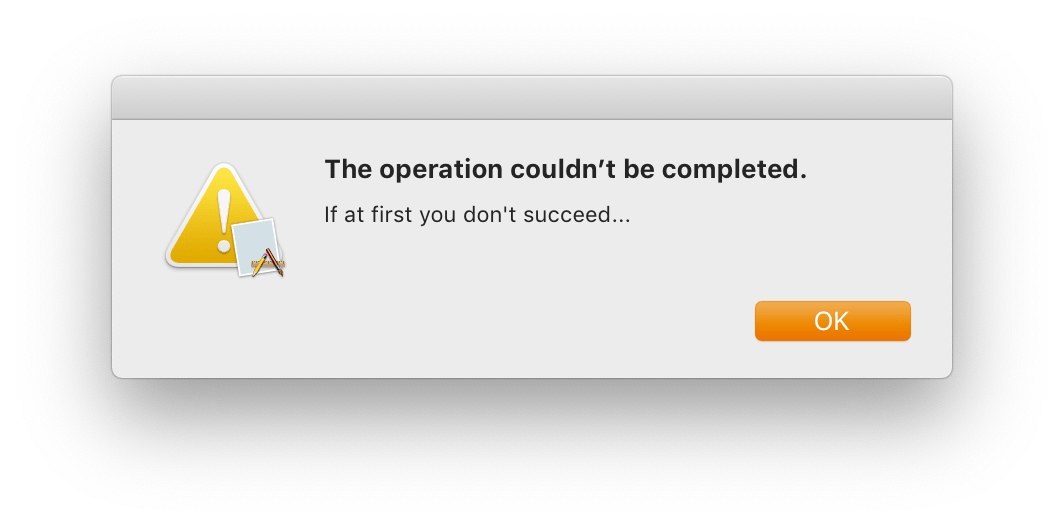

Communicating Errors on macOS

If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.

Communicating errors to users is significantly easier on macOS than on iOS.

For example,

you might construct and pass an NSError object

to the presentError(_:) method,

called on an NSWindow.

import AppKit

@NSApplicationMain

class AppDelegate: NSObject, NSApplicationDelegate {

@IBOutlet weak var window: NSWindow!

func applicationDidFinishLaunching(_ aNotification: Notification) {

do {

_ = try something()

} catch {

window.presentError(error)

}

}

func something() throws -> Never {

let userInfo: [String: Any] = [

NSLocalizedDescriptionKey:

NSLocalizedString("The operation couldn’t be completed.",

comment: "localizedErrorDescription"),

NSLocalizedRecoverySuggestionErrorKey:

NSLocalizedString("If at first you don't succeed...",

comment: "localizedErrorRecoverSuggestion")

]

throw NSError(domain: "com.nshipster.error", code: 1, userInfo: userInfo)

}

}

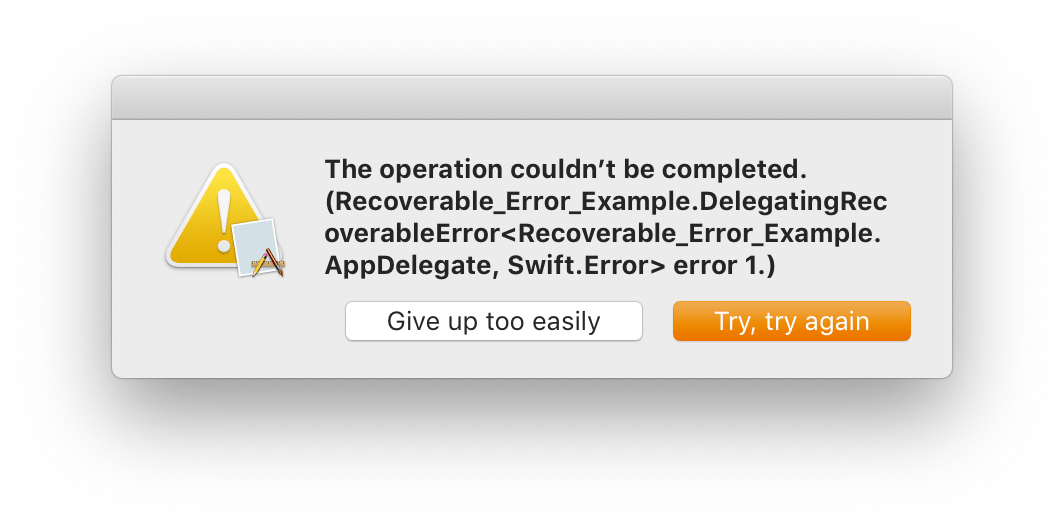

Doing so presents a modal alert dialog

that fits right in with the rest of the system.

But macOS error handling isn’t merely a matter of convenient APIs;

it also has built-in mechanisms for allowing

users to select one of several options

to attempt to resolve the reported issue.

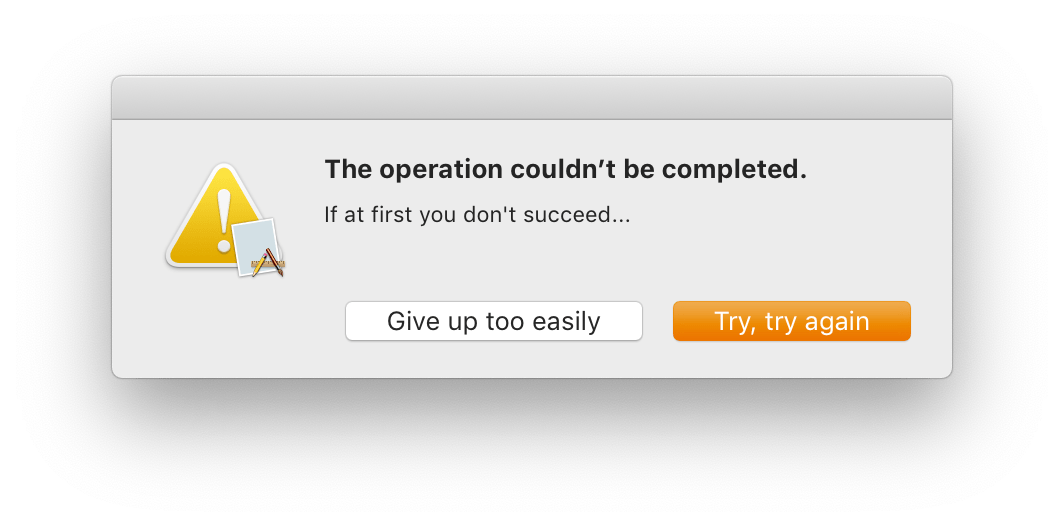

Recovering from Errors

To turn a conventional NSError into

one that supports recovery,

you specify values for the userInfo keys

NSLocalizedRecoveryOptionsErrorKey and NSRecoveryAttempterErrorKey.

A great way to do that

is to override the application(_:willPresentError:) delegate method

and intercept and modify an error before it’s presented to the user.

extension AppDelegate {

func application(_ application: NSApplication,

willPresentError error: Error) -> Error

{

var userInfo: [String: Any] = (error as NSError).userInfo

userInfo[NSLocalizedRecoveryOptionsErrorKey] = [

NSLocalizedString("Try, try again",

comment: "tryAgain")

NSLocalizedString("Give up too easily",

comment: "giveUp")

]

userInfo[NSRecoveryAttempterErrorKey] = self

return NSError(domain: (error as NSError).domain,

code: (error as NSError).code,

userInfo: userInfo)

}

}

For NSLocalizedRecoveryOptionsErrorKey,

specify an array of one or more localized strings

for each recovery option available the user.

For NSRecoveryAttempterErrorKey,

set an object that implements the

attemptRecovery(fromError:optionIndex:) method.

extension AppDelegate {

// MARK: NSErrorRecoveryAttempting

override func attemptRecovery(fromError error: Error,

optionIndex recoveryOptionIndex: Int) -> Bool

{

do {

switch recoveryOptionIndex {

case 0: // Try, try again

try something()

case 1:

fallthrough

default:

break

}

} catch {

window.presentError(error)

}

return true

}

}

With just a few lines of code,

you’re able to facilitate a remarkably complex interaction,

whereby a user is alerted to an error and prompted to resolve it

according to a set of available options.

Cool as that is,

it carries some pretty gross baggage.

First,

the attemptRecovery requirement is part of an

informal protocol,

which is effectively a handshake agreement

that things will work as advertised.

Second,

the use of option indexes instead of actual objects

makes for code that’s as fragile as it is cumbersome to write.

Fortunately,

we can significantly improve on this

by taking advantage of Swift’s superior type system

and (at long last) the second subject of this article.

Modernizing Error Recovery with RecoverableError

The RecoverableError protocol,

like LocalizedError is a refinement on the base Error protocol

with the following requirements:

protocol RecoverableError : Error {

var recoveryOptions: [String] { get }

func attemptRecovery(optionIndex recoveryOptionIndex: Int, resultHandler handler: @escaping (Bool) -> Void)

func attemptRecovery(optionIndex recoveryOptionIndex: Int) -> Bool

}

Also like LocalizedError,

these requirements map onto error userInfo keys

(albeit not as directly).

| Requirement | User Info Key |

|---|---|

recoveryOptions |

NSLocalizedRecoveryOptionsErrorKey |

attemptRecovery(optionIndex:_:) attemptRecovery(optionIndex:)

|

NSRecoveryAttempterErrorKey *

|

The recoveryOptions property requirement

is equivalent to the NSLocalizedRecoveryOptionsErrorKey:

an array of strings that describe the available options.

The attemptRecovery functions

formalize the previously informal delegate protocol;

func attemptRecovery(optionIndex:)

is for “application” granularity,

whereas

attemptRecovery(optionIndex:resultHandler:)

is for “document” granularity.

Supplementing RecoverableError with Additional Types

On its own,

the RecoverableError protocol improves only slightly on

the traditional, NSError-based methodology

by formalizing the requirements for recovery.

Rather than implementing conforming types individually,

we can generalize the functionality

with some clever use of generics.

First,

define an ErrorRecoveryDelegate protocol

that re-casts the attemptRecovery methods from before

to use an associated, RecoveryOption type.

protocol ErrorRecoveryDelegate: class {

associatedtype RecoveryOption: CustomStringConvertible,

CaseIterable

func attemptRecovery(from error: Error,

with option: RecoveryOption) -> Bool

}

Requiring that RecoveryOption conforms to CaseIterable,

allows us to vend options directly to API consumers

independently of their presentation to the user.

From here,

we can define a generic DelegatingRecoverableError type

that wraps an Error type

and associates it with the aforementioned Delegate,

which is responsible for providing recovery options

and attempting recovery with the one selected.

struct DelegatingRecoverableError<Delegate, Error>: RecoverableError

where Delegate: ErrorRecoveryDelegate,

Error: Swift.Error

{

let error: Error

weak var delegate: Delegate? = nil

init(recoveringFrom error: Error, with delegate: Delegate?) {

self.error = error

self.delegate = delegate

}

var recoveryOptions: [String] {

return Delegate.RecoveryOption.allCases.map { "($0)" }

}

func attemptRecovery(optionIndex recoveryOptionIndex: Int) -> Bool {

let recoveryOptions = Delegate.RecoveryOption.allCases

let index = recoveryOptions.index(recoveryOptions.startIndex,

offsetBy: recoveryOptionIndex)

let option = Delegate.RecoveryOption.allCases[index]

return self.delegate?.attemptRecovery(from: self.error,

with: option) ?? false

}

}

Now we can refactor the previous example of our macOS app

to have AppDelegate conform to ErrorRecoveryDelegate

and define a nested RecoveryOption enumeration

with all of the options we wish to support.

extension AppDelegate: ErrorRecoveryDelegate {

enum RecoveryOption: String, CaseIterable, CustomStringConvertible {

case tryAgain

case giveUp

var description: String {

switch self {

case .tryAgain:

return NSLocalizedString("Try, try again",

comment: self.rawValue)

case .giveUp:

return NSLocalizedString("Give up too easily",

comment: self.rawValue)

}

}

}

func attemptRecovery(from error: Error,

with option: RecoveryOption) -> Bool

{

do {

if option == .tryAgain {

try something()

}

} catch {

window.presentError(error)

}

return true

}

func application(_ application: NSApplication, willPresentError error: Error) -> Error {

return DelegatingRecoverableError(recoveringFrom: error, with: self)

}

}

The result?

…wait, that’s not right.

What’s missing?

To find out,

let’s look at our third and final protocol in our discussion.

Improving Interoperability with Cocoa Error Handling System

The CustomNSError protocol

is like an inverted NSError:

it allows a type conforming to Error

to act like it was instead an NSError subclass.

protocol CustomNSError: Error {

static var errorDomain: String { get }

var errorCode: Int { get }

var errorUserInfo: [String : Any] { get }

}

The protocol requirements correspond to the

domain, code, and userInfo properties of an NSError, respectively.

Now, back to our modal from before:

normally, the title is taken from userInfo via NSLocalizedDescriptionKey.

Types conforming to LocalizedError can provide this too

through their equivalent errorDescription property.

And while we could extend DelegatingRecoverableError

to adopt LocalizedError,

it’s actually much less work to add conformance for CustomNSError:

extension DelegatingRecoverableError: CustomNSError {

var errorUserInfo: [String: Any] {

return (self.error as NSError).userInfo

}

}

With this one additional step,

we can now enjoy the fruits of our burden.

In programming,

it’s often not what you know,

but what you know about.

Now that you’re aware of the existence of

LocalizedError, RecoverableError, CustomNSError,

you’ll be sure to identify situations in which they might

improve error handling in your app.

Useful AF, amiright?

Then again,

“Familiarity breeds contempt”;

so often,

what initially endears one to ourselves

is what ultimately causes us to revile it.

Such is the error of our ways.

Introduction¶

Object initialization is the process by which a new object is

allocated, its stored properties initialized, and any additional setup

tasks are performed, including allowing its superclass’s to perform

their own initialization. Object teardown is the reverse process,

performing teardown tasks, destroying stored properties, and

eventually deallocating the object.

Initializers¶

An initializer is responsible for the initialization of an

object. Initializers are introduced with the init keyword. For

example:

class A {

var i: Int

var s: String

init int(i: Int) string(s: String) {

self.i = i

self.s = s

completeInit()

}

func completeInit() { /* ... */ }

}

Here, the class A has an initializer that accepts an Int and a

String, and uses them to initialize its two stored properties,

then calls another method to perform other initialization tasks. The

initializer can be invoked by constructing a new A object:

var a = A(int: 17, string: "Seventeen")

The allocation of the new A object is implicit in the

construction syntax, and cannot be separated from the call to the

initializer.

Within an initializer, all of the stored properties must be

initialized (via an assignment) before self can be used in any

way. For example, the following would produce a compiler error:

init int(i: Int) string(s: String) { completeInit() // error: variable 'self.i' used before being initialized self.i = i self.s = s }

A stored property with an initial value declared within the class is

considered to be initialized at the beginning of the initializer. For

example, the following is a valid initializer:

class A2 {

var i: Int = 17

var s: String = "Seventeen"

init int(i: Int) string(s: String) {

// okay: i and s are both initialized in the class

completeInit()

}

func completeInit() { /* ... */ }

}

After all stored properties have been initialized, one is free to use

self in any manner.

Designated Initializers¶

There are two kinds of initializers in Swift: designated initializers

and convenience initializers. A designated initializer is

responsible for the primary initialization of an object, including the

initialization of any stored properties, chaining to one of its

superclass’s designated initializers via a super.init call (if

there is a superclass), and performing any other initialization tasks,

in that order. For example, consider a subclass B of A:

class B : A {

var d: Double

init int(i: Int) string(s: String) {

self.d = Double(i) // initialize stored properties

super.init(int: i, string: s) // chain to superclass

completeInitForB() // perform other tasks

}

func completeInitForB() { /* ... */ }

}

Consider the following construction of an object of type B:

var b = B(int: 17, string: "Seventeen")

Initialization proceeds in several steps:

- An object of type

Bis allocated by the runtime. B‘s initializer initializes the stored propertydto

17.0.B‘s initializer chains toA‘s initializer.A‘s initializer initialize’s the stored propertiesiand

s‘.A‘s initializer callscompleteInit(), then returns.B‘s initializer callscompleteInitForB(), then returns.

A class generally has a small number of designated initializers, which

act as funnel points through which the object will be

initialized. All of the designated initializers for a class must be

written within the class definition itself, rather than in an

extension, because the complete set of designated initializers is part

of the interface contract with subclasses of a class.

The other, non-designted initializers of a class are called

convenience initializers, which tend to provide additional

initialization capabilities that are often more convenient for common

tasks.

Convenience Initializers¶

A convenience initializer is an initializer that provides an

alternative interface to the designated initializers of a class. A

convenience initializer is denoted by the return type Self in the

definition. Unlike designated initializers, convenience initializers

can be defined either in the class definition itself or within an

extension of the class. For example:

extension A { init() -> Self { self.init(int: 17, string: "Seventeen") } }

A convenience initializer cannot initialize the stored properties of

the class directly, nor can it invoke a superclass initializer via

super.init. Rather, it must dispatch to another initializer

using self.init, which is then responsible for initializing the

object. A convenience initializer is not permitted to access self

(or anything that depends on self, such as one of its properties)

prior to the self.init call, although it may freely access

self after self.init.

Convenience initializers and designated initializers can both be used

to construct objects, using the same syntax. For example, the A

initializer above can be used to build a new A object without any

arguments:

var a2 = A() // uses convenience initializer

Initializer Inheritance¶

One of the primary benefits of convenience initializers is that they

can be inherited by subclasses. Initializer inheritance eliminates the

need to repeat common initialization code—such as initial values of

stored properties not easily written in the class itself, or common

registration tasks that occur during initialization—while using the

same initialization syntax. For example, this allows a B object to

be constructed with no arguments by using the inherited convenience

initializer defined in the previous section:

Initialization proceeds as follows:

- A

Bobject is allocated by the runtime. A‘s convenience initializerinit()is invoked.A‘s convenience initializer dispatches toinit int:string:

via theself.initcall. This call dynamically resolves to

B‘s designated initializer.B‘s designated initializer initializes the stored property

dto17.0.B‘s designated initializer chains toA‘s designated

initializer.A‘s designated initializer initialize’s the stored properties

iands‘.A‘s designated initializer callscompleteInit(), then

returns.B‘s designated initializer callscompleteInitForB(), then

returns.A‘s convenience initializer returns.

Convenience initializers are only inherited under certain

circumstances. Specifically, for a given subclass to inherit the

convenience initializers of its superclass, the subclass must override

each of the designated initializers of its superclass. For example

B provides the initializer init int:string:, which overrides

A‘s designated initializer init int:string: because the

initializer name and parameters are the same. If we had some other

subclass OtherB of A that did not provide such an override, it

would not inherit A‘s convenience initializers:

class OtherB : A {

var d: Double

init int(i: Int) string(s: String) double(d: Double) {

self.d = d // initialize stored properties

super.init(int: i, string: s) // chain to superclass

}

}

var ob = OtherB() // error: A's convenience initializer init() not inherited

Note that a subclass may have different designated initializers from

its superclass. This can occur in a number of ways. For example, the

subclass might override one of its superclass’s designated

initializers with a convenience initializer:

class YetAnotherB : A {

var d: Double

init int(i: Int) string(s: String) -> Self {

self.init(int: i, string: s, double: Double(i)) // dispatch

}

init int(i: Int) string(s: String) double(d: Double) {

self.d = d // initialize stored properties

super.init(int: i, string: s) // chain to superclass

}

}

var yab = YetAnotherB() // okay: YetAnotherB overrides all of A's designated initializers

In other cases, it’s possible that the convenience initializers of the

superclass simply can’t be made to work, because the subclass

initializers require additional information provided via a

parameter that isn’t present in the convenience initializers of the

superclass:

class PickyB : A {

var notEasy: NoEasyDefault

init int(i: Int) string(s: String) notEasy(NoEasyDefault) {

self.notEasy = notEasy

super.init(int: i, string: s) // chain to superclass

}

}

Here, PickyB has a stored property of a type NoEasyDefault

that can’t easily be given a default value: it has to be provided as a

parameter to one of PickyB‘s initializers. Therefore, PickyB

takes over responsibility for its own initialization, and

none of A‘s convenience initializers will be inherited into

PickyB.

Synthesized Initializers¶

When a particular class does not specify any designated initializers,

the implementation will synthesize initializers for the class when all

of the class’s stored properties have initial values in the class. The

form of the synthesized initializers depends on the superclass (if

present).

When a superclass is present, the compiler synthesizes a new

designated initializer in the subclass for each designated initializer

of the superclass. For example, consider the following class C:

class C : B {

var title: String = "Default Title"

}

The superclass B has a single designated initializer,:

init int(i: Int) string(s: String)

Therefore, the compiler synthesizes the following designated

initializer in C, which chains to the corresponding designated

initializer in the superclass:

init int(i: Int) string(s: String) { // title is already initialized in the class C super.init(int: i, string: s) }

The result of this synthesis is that all designated initializers of

the superclass are (automatically) overridden in the subclass,

becoming designated initializers of the subclass as well. Therefore,

any convenience initializers in the superclass are also inherited,

allowing the subclass (C) to be constructed with the same

initializers as the superclass (B):

var c1 = C(int: 17, string: "Seventeen") var c2 = C()

When the class has no superclass, a default initializer (with no

parameters) is implicitly defined:

class D { var title = "Default Title" /* implicitly defined */ init() { } } var d = D() // uses implicitly-defined default initializer

Required Initializers¶

Objects are generally constructed with the construction syntax

T(...) used in all of the examples above, where T is the name

of the type. However, it is occasionally useful to construct an object

for which the actual type is not known until runtime. For example, one

might have a View class that expects to be initialized with a

specific set of coordinates:

struct Rect {

var origin: (Int, Int)

var dimensions: (Int, Int)

}

class View {

init frame(Rect) { /* initialize view */ }

}

The actual initialization of a subclass of View would then be

performed at runtime, with the actual subclass being determined via

some external file that describes the user interface. The actual

instantiation of the object would use a type value:

func createView(viewClass: View.Type, frame: Rect) -> View { return viewClass(frame: frame) // error: 'init frame:' is not 'required' }

The code above is invalid because there is no guarantee that a given

subclass of View will have an initializer init frame:, because

the subclass might have taken over its own initialization (as with

PickyB, above). To require that all subclasses provide a

particular initializer, use the required attribute as follows:

class View {

@required init frame(Rect) {

/* initialize view */

}

}

func createView(viewClass: View.Type, frame: Rect) -> View {

return viewClass(frame: frame) // okay

}

The required attribute allows the initializer to be used to

construct an object of a dynamically-determined subclass, as in the

createView method. It places the (transitive) requirement on all

subclasses of View to provide an initializer init frame:. For

example, the following Button subclass would produce an error:

class Button : View { // error: 'Button' does not provide required initializer 'init frame:'. }

The fix is to implement the required initializer in Button:

class Button : View {

@required init frame(Rect) { // okay: satisfies requirement

super.init(frame: frame)

}

}

Initializers in Protocols¶

Initializers may be declared within a protocol. For example:

protocol DefaultInitializable { init() }

A class can satisfy this requirement by providing a required

initializer. For example, only the first of the two following classes

conforms to its protocol:

class DefInit : DefaultInitializable {

@required init() { }

}

class AlmostDefInit : DefaultInitializable {

init() { } // error: initializer used for protocol conformance must be 'required'

}

The required requirement ensures that all subclasses of the class

declaring conformance to the protocol will also have the initializer,

so they too will conform to the protocol. This allows one to construct

objects given type values of protocol type:

func createAnyDefInit(typeVal: DefaultInitializable.Type) -> DefaultInitializable { return typeVal() }

De-initializers¶

While initializers are responsible for setting up an object’s state,

de-initializers are responsible for tearing down that state. Most

classes don’t require a de-initializer, because Swift automatically

releases all stored properties and calls to the superclass’s

de-initializer. However, if your class has allocated a resource that

is not an object (say, a Unix file descriptor) or has registered

itself during initialization, one can write a de-initializer using

deinit:

class FileHandle {

var fd: Int32

init withFileDescriptor(fd: Int32) {

self.fd = fd

}

deinit {

close(fd)

}

}

The statements within a de-initializer (here, the call to close)

execute first, then the superclass’s de-initializer is

called. Finally, stored properties are released and the object is

deallocated.

Methods Returning Self¶

A class method can have the special return type Self, which refers

to the dynamic type of self. Such a method guarantees that it will

return an object with the same dynamic type as self. One of the

primary uses of the Self return type is for factory methods:

extension View {

class func createView(frame: Rect) -> Self {

return self(frame: frame)

}

}

Within the body of this class method, the implicit parameter self

is a value with type View.Type, i.e., it’s a type value for the

class View or one of its subclasses. Therefore, the restrictions

are the same as for any value of type View.Type: one can call

other class methods and construct new objects using required

initializers of the class, among other things. The result returned

from such a method must be derived from the type of Self. For

example, it cannot return a value of type View, because self

might refer to some subclass of View.

Instance methods can also return Self. This is typically used to

allow chaining of method calls by returning Self from each method,

as in the builder pattern:

class DialogBuilder { func setTitle(title: String) -> Self { // set the title return self; } func setBounds(frame: Rect) -> Self { // set the bounds return self; } } var builder = DialogBuilder() .setTitle("Hello, World!") .setBounds(Rect(0, 0, 640, 480))

Memory Safety¶

Swift aims to provide memory safety by default, and much of the design

of Swift’s object initialization scheme is in service of that

goal. This section describes the rationale for the design based on the

memory-safety goals of the language.

Three-Phase Initialization¶

The three-phase initialization model used by Swift’s initializers

ensures that all stored properties get initialized before any code can

make use of self. This is important uses of self—say,

calling a method on self—could end up referring to stored

properties before they are initialized. Consider the following

Objective-C code, where instance variables are initialized after the

call to the the superclass initializer:

@interface A : NSObject

- (instancetype)init;

- (void)finishInit;

@end

@implementation A

- (instancetype)init {

self = [super init];

if (self) {

[self finishInit];

}

return self;

}

@end

@interface B : A

@end

@implementation B {

NSString *ivar;

}

- (instancetype)init {

self = [super init];

if (self) {

self->ivar = @"Default name";

}

return self;

}

- (void) finishInit {

NSLog(@"ivar has the value %@n", self->ivar);

}

@end

When initializing a B object, the NSLog statement will print:

ivar has the value (null)

because -[B finishInit] executes before B has had a chance to

initialize its instance variables. Swift initializers avoid this issue

by splitting each initializer into three phases:

1. Initialize stored properties. In this phase, the compiler verifies

that self is not used except when writing to the stored properties

of the current class (not its superclasses!). Additionally, this

initialization directly writes to the storage of the stored

properties, and does not call any setter or willSet/didSet

method. In this phase, it is not possible to read any of the stored

properties.

2. Call to superclass initializer, if any. As with the first step,

self cannot be accessed at all.

3. Perform any additional initialization tasks, which may call methods

on self, access properties, and so on.

Note that, with this scheme, self cannot be used until the

original class and all of its superclasses have initialized their

stored properties, closing the memory safety hole.

Initializer Inheritance Model¶

FIXME: To be written

-

Tweet -

Share

0 -

Reddit -

+1 -

Pocket -

Pinterest

0 -