In mathematical logic, a tautology (from Greek: ταυτολογία) is a formula or assertion that is true in every possible interpretation. An example is «x=y or x≠y». Similarly, «either the ball is green, or the ball is not green» is always true, regardless of the colour of the ball.

The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein first applied the term to redundancies of propositional logic in 1921, borrowing from rhetoric, where a tautology is a repetitive statement. In logic, a formula is satisfiable if it is true under at least one interpretation, and thus a tautology is a formula whose negation is unsatisfiable. In other words, it cannot be false. It cannot be untrue.

Unsatisfiable statements, both through negation and affirmation, are known formally as contradictions. A formula that is neither a tautology nor a contradiction is said to be logically contingent.

Such a formula can be made either true or false based on the values assigned to its propositional variables. The double turnstile notation

Tautologies are a key concept in propositional logic, where a tautology is defined as a propositional formula that is true under any possible Boolean valuation of its propositional variables.[2] A key property of tautologies in propositional logic is that an effective method exists for testing whether a given formula is always satisfied (equiv., whether its negation is unsatisfiable).

The definition of tautology can be extended to sentences in predicate logic, which may contain quantifiers—a feature absent from sentences of propositional logic.[3]

Indeed, in propositional logic, there is no distinction between a tautology and a logically valid formula. In the context of predicate logic, many authors define a tautology to be a sentence that can be obtained by taking a tautology of propositional logic, and uniformly replacing each propositional variable by a first-order formula (one formula per propositional variable). The set of such formulas is a proper subset of the set of logically valid sentences of predicate logic (i.e., sentences that are true in every model).

History[edit]

The word tautology was used by the ancient Greeks to describe a statement that was asserted to be true merely by virtue of saying the same thing twice, a pejorative meaning that is still used for rhetorical tautologies. Between 1800 and 1940, the word gained new meaning in logic, and is currently used in mathematical logic to denote a certain type of propositional formula, without the pejorative connotations it originally possessed.

In 1800, Immanuel Kant wrote in his book Logic:

The identity of concepts in analytical judgments can be either explicit (explicita) or non-explicit (implicita). In the former case analytic propositions are tautological.

Here, analytic proposition refers to an analytic truth, a statement in natural language that is true solely because of the terms involved.

In 1884, Gottlob Frege proposed in his Grundlagen that a truth is analytic exactly if it can be derived using logic. However, he maintained a distinction between analytic truths (i.e., truths based only on the meanings of their terms) and tautologies (i.e., statements devoid of content).

In his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus in 1921, Ludwig Wittgenstein proposed that statements that can be deduced by logical deduction are tautological (empty of meaning), as well as being analytic truths. Henri Poincaré had made similar remarks in Science and Hypothesis in 1905. Although Bertrand Russell at first argued against these remarks by Wittgenstein and Poincaré, claiming that mathematical truths were not only non-tautologous but were synthetic, he later spoke in favor of them in 1918:

Everything that is a proposition of logic has got to be in some sense or the other like a tautology. It has got to be something that has some peculiar quality, which I do not know how to define, that belongs to logical propositions but not to others.

Here, logical proposition refers to a proposition that is provable using the laws of logic.

During the 1930s, the formalization of the semantics of propositional logic in terms of truth assignments was developed. The term «tautology» began to be applied to those propositional formulas that are true regardless of the truth or falsity of their propositional variables. Some early books on logic (such as Symbolic Logic by C. I. Lewis and Langford, 1932) used the term for any proposition (in any formal logic) that is universally valid. It is common in presentations after this (such as Stephen Kleene 1967 and Herbert Enderton 2002) to use tautology to refer to a logically valid propositional formula, but to maintain a distinction between «tautology» and «logically valid» in the context of first-order logic (see below).

Background[edit]

Propositional logic begins with propositional variables, atomic units that represent concrete propositions. A formula consists of propositional variables connected by logical connectives, built up in such a way that the truth of the overall formula can be deduced from the truth or falsity of each variable. A valuation is a function that assigns each propositional variable to either T (for truth) or F (for falsity). So by using the propositional variables A and B, the binary connectives

A valuation here must assign to each of A and B either T or F. But no matter how this assignment is made, the overall formula will come out true. For if the first conjunction

Definition and examples[edit]

A formula of propositional logic is a tautology if the formula itself is always true, regardless of which valuation is used for the propositional variables. There are infinitely many tautologies. Examples include:

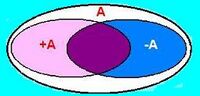

(«A or not A«), the law of excluded middle. This formula has only one propositional variable, A. Any valuation for this formula must, by definition, assign A one of the truth values true or false, and assign

A the other truth value. For instance, «The cat is black or the cat is not black».

(«if A implies B, then not-B implies not-A«, and vice versa), which expresses the law of contraposition. For instance, «If it’s a book, it is blue; if it’s not blue, it’s not a book.»

(«if not-A implies both B and its negation not-B, then not-A must be false, then A must be true»), which is the principle known as reductio ad absurdum. For instance, «If it’s not blue, it’s a book, if it’s not blue, it’s also not a book, so it is blue.»

(«if not both A and B, then not-A or not-B«, and vice versa), which is known as De Morgan’s law. «If it is not both blue and a book, then it’s either not a book or it’s not blue»

(«if A implies B and B implies C, then A implies C«), which is the principle known as syllogism. «If it’s a book, then it’s blue and if it’s blue, then it’s on that shelf, then if it’s a book, it’s on that shelf.»

(«if at least one of A or B is true, and each implies C, then C must be true as well»), which is the principle known as proof by cases. «Books and blue things are on that shelf. If it’s either a book or it’s blue, it’s on that shelf.»

A minimal tautology is a tautology that is not the instance of a shorter tautology.

Verifying tautologies[edit]

The problem of determining whether a formula is a tautology is fundamental in propositional logic. If there are n variables occurring in a formula then there are 2n distinct valuations for the formula. Therefore, the task of determining whether or not the formula is a tautology is a finite and mechanical one: one needs only to evaluate the truth value of the formula under each of its possible valuations. One algorithmic method for verifying that every valuation makes the formula to be true is to make a truth table that includes every possible valuation.[2]

For example, consider the formula

There are 8 possible valuations for the propositional variables A, B, C, represented by the first three columns of the following table. The remaining columns show the truth of subformulas of the formula above, culminating in a column showing the truth value of the original formula under each valuation.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | T | T | T | T | T |

| T | T | F | T | F | F | F | T |

| T | F | T | F | T | T | T | T |

| T | F | F | F | T | T | T | T |

| F | T | T | F | T | T | T | T |

| F | T | F | F | T | F | T | T |

| F | F | T | F | T | T | T | T |

| F | F | F | F | T | T | T | T |

Because each row of the final column shows T, the sentence in question is verified to be a tautology.

It is also possible to define a deductive system (i.e., proof system) for propositional logic, as a simpler variant of the deductive systems employed for first-order logic (see Kleene 1967, Sec 1.9 for one such system). A proof of a tautology in an appropriate deduction system may be much shorter than a complete truth table (a formula with n propositional variables requires a truth table with 2n lines, which quickly becomes infeasible as n increases). Proof systems are also required for the study of intuitionistic propositional logic, in which the method of truth tables cannot be employed because the law of the excluded middle is not assumed.

Tautological implication[edit]

A formula R is said to tautologically imply a formula S if every valuation that causes R to be true also causes S to be true. This situation is denoted

For example, let

It follows from the definition that if a formula

Substitution[edit]

There is a general procedure, the substitution rule, that allows additional tautologies to be constructed from a given tautology (Kleene 1967 sec. 3). Suppose that S is a tautology and for each propositional variable A in S a fixed sentence SA is chosen. Then the sentence obtained by replacing each variable A in S with the corresponding sentence SA is also a tautology.

For example, let S be the tautology

.

Let SA be

It follows from the substitution rule that the sentence

Semantic completeness and soundness[edit]

An axiomatic system is complete if every tautology is a theorem (derivable from axioms). An axiomatic system is sound if every theorem is a tautology.

Efficient verification and the Boolean satisfiability problem[edit]

The problem of constructing practical algorithms to determine whether sentences with large numbers of propositional variables are tautologies is an area of contemporary research in the area of automated theorem proving.

The method of truth tables illustrated above is provably correct – the truth table for a tautology will end in a column with only T, while the truth table for a sentence that is not a tautology will contain a row whose final column is F, and the valuation corresponding to that row is a valuation that does not satisfy the sentence being tested. This method for verifying tautologies is an effective procedure, which means that given unlimited computational resources it can always be used to mechanistically determine whether a sentence is a tautology. This means, in particular, the set of tautologies over a fixed finite or countable alphabet is a decidable set.

As an efficient procedure, however, truth tables are constrained by the fact that the number of valuations that must be checked increases as 2k, where k is the number of variables in the formula. This exponential growth in the computation length renders the truth table method useless for formulas with thousands of propositional variables, as contemporary computing hardware cannot execute the algorithm in a feasible time period.

The problem of determining whether there is any valuation that makes a formula true is the Boolean satisfiability problem; the problem of checking tautologies is equivalent to this problem, because verifying that a sentence S is a tautology is equivalent to verifying that there is no valuation satisfying

Tautologies versus validities in first-order logic[edit]

The fundamental definition of a tautology is in the context of propositional logic. The definition can be extended, however, to sentences in first-order logic.[4] These sentences may contain quantifiers, unlike sentences of propositional logic. In the context of first-order logic, a distinction is maintained between logical validities, sentences that are true in every model, and tautologies (or, tautological validities), which are a proper subset of the first-order logical validities. In the context of propositional logic, these two terms coincide.

A tautology in first-order logic is a sentence that can be obtained by taking a tautology of propositional logic and uniformly replacing each propositional variable by a first-order formula (one formula per propositional variable). For example, because

It is obtained by replacing

Not all logical validities are tautologies in first-order logic. For example, the sentence

is true in any first-order interpretation, but it corresponds to the propositional sentence

See also[edit]

Normal forms[edit]

- Algebraic normal form

- Conjunctive normal form

- Disjunctive normal form

- Logic optimization

[edit]

|

|

References[edit]

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Tautology». mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-08-14.

- ^ a b «tautology | Definition & Facts». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-08-14.

- ^ «Tautology (logic)». wikipedia.org.

- ^ «New Members». Naval Engineers Journal. 114 (1): 17–18. January 2002. doi:10.1111/j.1559-3584.2002.tb00103.x. ISSN 0028-1425.

Further reading[edit]

- Bocheński, J. M. (1959) Précis of Mathematical Logic, translated from the French and German editions by Otto Bird, Dordrecht, South Holland: D. Reidel.

- Enderton, H. B. (2002) A Mathematical Introduction to Logic, Harcourt/Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-238452-0.

- Kleene, S. C. (1967) Mathematical Logic, reprinted 2002, Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-42533-9.

- Reichenbach, H. (1947). Elements of Symbolic Logic, reprinted 1980, Dover, ISBN 0-486-24004-5

- Wittgenstein, L. (1921). «Logisch-philosophiche Abhandlung», Annalen der Naturphilosophie (Leipzig), v. 14, pp. 185–262, reprinted in English translation as Tractatus logico-philosophicus, New York City and London, 1922.

External links[edit]

- «Tautology», Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

In mathematical logic, a tautology (from Greek: ταυτολογία) is a formula or assertion that is true in every possible interpretation. An example is «x=y or x≠y». Similarly, «either the ball is green, or the ball is not green» is always true, regardless of the colour of the ball.

The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein first applied the term to redundancies of propositional logic in 1921, borrowing from rhetoric, where a tautology is a repetitive statement. In logic, a formula is satisfiable if it is true under at least one interpretation, and thus a tautology is a formula whose negation is unsatisfiable. In other words, it cannot be false. It cannot be untrue.

Unsatisfiable statements, both through negation and affirmation, are known formally as contradictions. A formula that is neither a tautology nor a contradiction is said to be logically contingent.

Such a formula can be made either true or false based on the values assigned to its propositional variables. The double turnstile notation

Tautologies are a key concept in propositional logic, where a tautology is defined as a propositional formula that is true under any possible Boolean valuation of its propositional variables.[2] A key property of tautologies in propositional logic is that an effective method exists for testing whether a given formula is always satisfied (equiv., whether its negation is unsatisfiable).

The definition of tautology can be extended to sentences in predicate logic, which may contain quantifiers—a feature absent from sentences of propositional logic.[3]

Indeed, in propositional logic, there is no distinction between a tautology and a logically valid formula. In the context of predicate logic, many authors define a tautology to be a sentence that can be obtained by taking a tautology of propositional logic, and uniformly replacing each propositional variable by a first-order formula (one formula per propositional variable). The set of such formulas is a proper subset of the set of logically valid sentences of predicate logic (i.e., sentences that are true in every model).

History[edit]

The word tautology was used by the ancient Greeks to describe a statement that was asserted to be true merely by virtue of saying the same thing twice, a pejorative meaning that is still used for rhetorical tautologies. Between 1800 and 1940, the word gained new meaning in logic, and is currently used in mathematical logic to denote a certain type of propositional formula, without the pejorative connotations it originally possessed.

In 1800, Immanuel Kant wrote in his book Logic:

The identity of concepts in analytical judgments can be either explicit (explicita) or non-explicit (implicita). In the former case analytic propositions are tautological.

Here, analytic proposition refers to an analytic truth, a statement in natural language that is true solely because of the terms involved.

In 1884, Gottlob Frege proposed in his Grundlagen that a truth is analytic exactly if it can be derived using logic. However, he maintained a distinction between analytic truths (i.e., truths based only on the meanings of their terms) and tautologies (i.e., statements devoid of content).

In his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus in 1921, Ludwig Wittgenstein proposed that statements that can be deduced by logical deduction are tautological (empty of meaning), as well as being analytic truths. Henri Poincaré had made similar remarks in Science and Hypothesis in 1905. Although Bertrand Russell at first argued against these remarks by Wittgenstein and Poincaré, claiming that mathematical truths were not only non-tautologous but were synthetic, he later spoke in favor of them in 1918:

Everything that is a proposition of logic has got to be in some sense or the other like a tautology. It has got to be something that has some peculiar quality, which I do not know how to define, that belongs to logical propositions but not to others.

Here, logical proposition refers to a proposition that is provable using the laws of logic.

During the 1930s, the formalization of the semantics of propositional logic in terms of truth assignments was developed. The term «tautology» began to be applied to those propositional formulas that are true regardless of the truth or falsity of their propositional variables. Some early books on logic (such as Symbolic Logic by C. I. Lewis and Langford, 1932) used the term for any proposition (in any formal logic) that is universally valid. It is common in presentations after this (such as Stephen Kleene 1967 and Herbert Enderton 2002) to use tautology to refer to a logically valid propositional formula, but to maintain a distinction between «tautology» and «logically valid» in the context of first-order logic (see below).

Background[edit]

Propositional logic begins with propositional variables, atomic units that represent concrete propositions. A formula consists of propositional variables connected by logical connectives, built up in such a way that the truth of the overall formula can be deduced from the truth or falsity of each variable. A valuation is a function that assigns each propositional variable to either T (for truth) or F (for falsity). So by using the propositional variables A and B, the binary connectives

A valuation here must assign to each of A and B either T or F. But no matter how this assignment is made, the overall formula will come out true. For if the first conjunction

Definition and examples[edit]

A formula of propositional logic is a tautology if the formula itself is always true, regardless of which valuation is used for the propositional variables. There are infinitely many tautologies. Examples include:

(«A or not A«), the law of excluded middle. This formula has only one propositional variable, A. Any valuation for this formula must, by definition, assign A one of the truth values true or false, and assign

A the other truth value. For instance, «The cat is black or the cat is not black».

(«if A implies B, then not-B implies not-A«, and vice versa), which expresses the law of contraposition. For instance, «If it’s a book, it is blue; if it’s not blue, it’s not a book.»

(«if not-A implies both B and its negation not-B, then not-A must be false, then A must be true»), which is the principle known as reductio ad absurdum. For instance, «If it’s not blue, it’s a book, if it’s not blue, it’s also not a book, so it is blue.»

(«if not both A and B, then not-A or not-B«, and vice versa), which is known as De Morgan’s law. «If it is not both blue and a book, then it’s either not a book or it’s not blue»

(«if A implies B and B implies C, then A implies C«), which is the principle known as syllogism. «If it’s a book, then it’s blue and if it’s blue, then it’s on that shelf, then if it’s a book, it’s on that shelf.»

(«if at least one of A or B is true, and each implies C, then C must be true as well»), which is the principle known as proof by cases. «Books and blue things are on that shelf. If it’s either a book or it’s blue, it’s on that shelf.»

A minimal tautology is a tautology that is not the instance of a shorter tautology.

Verifying tautologies[edit]

The problem of determining whether a formula is a tautology is fundamental in propositional logic. If there are n variables occurring in a formula then there are 2n distinct valuations for the formula. Therefore, the task of determining whether or not the formula is a tautology is a finite and mechanical one: one needs only to evaluate the truth value of the formula under each of its possible valuations. One algorithmic method for verifying that every valuation makes the formula to be true is to make a truth table that includes every possible valuation.[2]

For example, consider the formula

There are 8 possible valuations for the propositional variables A, B, C, represented by the first three columns of the following table. The remaining columns show the truth of subformulas of the formula above, culminating in a column showing the truth value of the original formula under each valuation.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | T | T | T | T | T |

| T | T | F | T | F | F | F | T |

| T | F | T | F | T | T | T | T |

| T | F | F | F | T | T | T | T |

| F | T | T | F | T | T | T | T |

| F | T | F | F | T | F | T | T |

| F | F | T | F | T | T | T | T |

| F | F | F | F | T | T | T | T |

Because each row of the final column shows T, the sentence in question is verified to be a tautology.

It is also possible to define a deductive system (i.e., proof system) for propositional logic, as a simpler variant of the deductive systems employed for first-order logic (see Kleene 1967, Sec 1.9 for one such system). A proof of a tautology in an appropriate deduction system may be much shorter than a complete truth table (a formula with n propositional variables requires a truth table with 2n lines, which quickly becomes infeasible as n increases). Proof systems are also required for the study of intuitionistic propositional logic, in which the method of truth tables cannot be employed because the law of the excluded middle is not assumed.

Tautological implication[edit]

A formula R is said to tautologically imply a formula S if every valuation that causes R to be true also causes S to be true. This situation is denoted

For example, let

It follows from the definition that if a formula

Substitution[edit]

There is a general procedure, the substitution rule, that allows additional tautologies to be constructed from a given tautology (Kleene 1967 sec. 3). Suppose that S is a tautology and for each propositional variable A in S a fixed sentence SA is chosen. Then the sentence obtained by replacing each variable A in S with the corresponding sentence SA is also a tautology.

For example, let S be the tautology

.

Let SA be

It follows from the substitution rule that the sentence

Semantic completeness and soundness[edit]

An axiomatic system is complete if every tautology is a theorem (derivable from axioms). An axiomatic system is sound if every theorem is a tautology.

Efficient verification and the Boolean satisfiability problem[edit]

The problem of constructing practical algorithms to determine whether sentences with large numbers of propositional variables are tautologies is an area of contemporary research in the area of automated theorem proving.

The method of truth tables illustrated above is provably correct – the truth table for a tautology will end in a column with only T, while the truth table for a sentence that is not a tautology will contain a row whose final column is F, and the valuation corresponding to that row is a valuation that does not satisfy the sentence being tested. This method for verifying tautologies is an effective procedure, which means that given unlimited computational resources it can always be used to mechanistically determine whether a sentence is a tautology. This means, in particular, the set of tautologies over a fixed finite or countable alphabet is a decidable set.

As an efficient procedure, however, truth tables are constrained by the fact that the number of valuations that must be checked increases as 2k, where k is the number of variables in the formula. This exponential growth in the computation length renders the truth table method useless for formulas with thousands of propositional variables, as contemporary computing hardware cannot execute the algorithm in a feasible time period.

The problem of determining whether there is any valuation that makes a formula true is the Boolean satisfiability problem; the problem of checking tautologies is equivalent to this problem, because verifying that a sentence S is a tautology is equivalent to verifying that there is no valuation satisfying

Tautologies versus validities in first-order logic[edit]

The fundamental definition of a tautology is in the context of propositional logic. The definition can be extended, however, to sentences in first-order logic.[4] These sentences may contain quantifiers, unlike sentences of propositional logic. In the context of first-order logic, a distinction is maintained between logical validities, sentences that are true in every model, and tautologies (or, tautological validities), which are a proper subset of the first-order logical validities. In the context of propositional logic, these two terms coincide.

A tautology in first-order logic is a sentence that can be obtained by taking a tautology of propositional logic and uniformly replacing each propositional variable by a first-order formula (one formula per propositional variable). For example, because

It is obtained by replacing

Not all logical validities are tautologies in first-order logic. For example, the sentence

is true in any first-order interpretation, but it corresponds to the propositional sentence

See also[edit]

Normal forms[edit]

- Algebraic normal form

- Conjunctive normal form

- Disjunctive normal form

- Logic optimization

[edit]

|

|

References[edit]

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Tautology». mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-08-14.

- ^ a b «tautology | Definition & Facts». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-08-14.

- ^ «Tautology (logic)». wikipedia.org.

- ^ «New Members». Naval Engineers Journal. 114 (1): 17–18. January 2002. doi:10.1111/j.1559-3584.2002.tb00103.x. ISSN 0028-1425.

Further reading[edit]

- Bocheński, J. M. (1959) Précis of Mathematical Logic, translated from the French and German editions by Otto Bird, Dordrecht, South Holland: D. Reidel.

- Enderton, H. B. (2002) A Mathematical Introduction to Logic, Harcourt/Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-238452-0.

- Kleene, S. C. (1967) Mathematical Logic, reprinted 2002, Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-42533-9.

- Reichenbach, H. (1947). Elements of Symbolic Logic, reprinted 1980, Dover, ISBN 0-486-24004-5

- Wittgenstein, L. (1921). «Logisch-philosophiche Abhandlung», Annalen der Naturphilosophie (Leipzig), v. 14, pp. 185–262, reprinted in English translation as Tractatus logico-philosophicus, New York City and London, 1922.

External links[edit]

- «Tautology», Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

Пролегомены к формализованной содержательной логике

Тавтология (от греч. ταὐτός – тот же самый и λόγος – слово), термин классической формальной логики, означающий формулу (суждение, высказывание), которая остаётся тождественно истинной для любого набора значений ее переменных. Тождественная истинность такой формулы обусловлена исключительно её логической структурой.

-

-

- Например, в логике предикатов 1-го порядка любая атомарная формула A вида a = a (где a суть терм (термин)) является тавтологией: если a = МАСЛО, то атомарная формула A имеет вид

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- МАСЛО = МАСЛО («Масло масленное»).

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Например, в логике предикатов 1-го порядка любая атомарная формула A вида a = a (где a суть терм (термин)) является тавтологией: если a = МАСЛО, то атомарная формула A имеет вид

-

Это значение термина «тавтология» было введено Л.Витгенштейном, а позднее сфера его применения была расширена: «тавтологией» стали называть вообще логически истинные формулы классических логических исчислений – законы классической логики. В соответствии с этим термин «тавтология» естественно относить не к «чистым», а к прикладным формальным исчислениям, в которых зафиксирована область изменения переменных (предметная область рассмотрения или универсум), не смотря на то, что тавтология не зависит от того, каков этот универсум.

Почему? Потому что известна область интерпретации абстрактной формулы: вы всегда имеете возможность проверки её тождественной истинности, а не просто выполнимости в какой-то части универсума.

В классической формальной логике термины «тавтология», «логический закон», «тождественно истинная формула» являются синонимами. Одновременно в классической формальной логике термин «тавтология» используется в качестве особой разновидности логической ошибки.

Позиция автора статьи[]

Витгенштейн, назвав «тавтологией» любую тождественно истинную формулу или логический закон формального исчисления, фактически закрепил уже применяемую десятилетиями многими логиками и философами лексику. Так Г.В.Ф.Гегель применял термин «тавтология» именно в смысле логического закона. Широко известна данная им характеристика для классической формальной логики: «Эта логика ничего кроме формальных тавтологий дать не в состоянии…»

Двусмысленность понятия «Тавтология» в обыденной речи[]

В обыденной речи (в отличие от, например, текстов юридических законов или инструкций по эксплуатации) достаточно часто используются тавтологичные конструкции, которые, однако, не вводят в заблуждение, так как верификация высказываний осуществляется в «режиме реального времени». В этом случае мы легко различаем, какой смысл «здесь и сейчас» (тавтология это логический закон или логическая ошибка) имеет понятие «Тавтология»:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Тавтология как логическая ОШИБКА:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

1) крайний случай логической ошибки «предвосхищение основания» (лат. peti-tio principii), а именно: когда нечто определяется или доказывается тем же самым (лат. idem per idem).

2) “п о р о ч н ы й круг”, т. е. когда тезис обосновывается аргументами, а аргументы обосновываются этим же тезисом.

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Например, “Опиум усыпляет потому, что имеет усыпляющую силу”.

-

-

-

-

-

В среде формализованного языка (будь то формальная или содержательная логика), очевидно, что такая двусмысленность не допустима, так как верификация суждения осуществляется «наедине с текстом».

Тавтологии диалектической логики[]

Диалектическими противоположностями в марксизме традиционно являются следующие пары:

сущность и явление, качество и количество, пространство и время, причина и следствие, необходимость и случайность, действительность и возможность, материя и сознание, объект и субъект и др.

Будучи диалектическими противоположностями эти категории образуют диалектически тождественные пары (диады), которые являются элементарными тавтологиями диалектической логики:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- СУЩНОСТЬ

ЯВЛЕНИЕ

- СУЩНОСТЬ

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- КАЧЕСТВО

КОЛИЧЕСТВО

- КАЧЕСТВО

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- ЕДИНСТВО

БОРЬБА

- ЕДИНСТВО

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- МАТЕРИЯ

СОЗНАНИЕ

- МАТЕРИЯ

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- ПРИЧИНА

СЛЕДСТВИЕ

- ПРИЧИНА

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- НЕОБХОДИМОСТЬ

СЛУЧАЙНОСТЬ

- НЕОБХОДИМОСТЬ

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Производительные СИЛЫ

Производственные ОТНОШЕНИЯ

- Производительные СИЛЫ

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Потребительная СТОИМОСТЬ

Меновая СТОИМОСТЬ

- Потребительная СТОИМОСТЬ

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Здесь символ «

» суть знак диалектической тождественности.

- Здесь символ «

-

-

Тавтологиями Гегель и Маркс в собственных логиках считали также триады. При этом необходимо учитывать, что эти триады никогда не проходили интерсубъективной верификации, а считались эпигонами безусловно истинными как результаты божественного откровения. В марксистско-ленинской диалектике истинной считается единственная гегелевская триада:

При этом не может не возникнуть вопрос: как это в диалектико-материалистическую идеализацию мог попасть как тождественно истинный логический закон из диаметрально противоположной диалектико-идеалистической идеализации? Как это стало возможным? Подумайте!!!

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Всё предельно элементарно: гегелевские суждения становятся правдоподобными тогда, когда Гегель забывает о своём Принципе препозиции (ИДЕЯ — первична, МАТЕРИЯ — вторична), а мыслит в соответствие с реальным развитием процесса, т.е. материалистически…

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Тавтология в Дианомике[]

Тавтология (от греч. tauto — то же самое и logos — слово) суть категория Дианомики — логически истинная формула, логический закон. Категория ТАВТОЛОГИЯ суть результат диалектического отрицания категории ПАРАДОКС. В своей экзогенной сети категория ТАВТОЛОГИЯ суть акциденция категории РАЗРЕШЕНИЕ.

Тавтологией в Дианомической логике является любая диада, триада, а также любое суждение, которое корректно образовано из категорий с помощью логических операций и принадлежащее Диалектической сети.

Тавтология и парадокс[]

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Краткий миг торжества… между двумя бесконечностями времени…

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Из энциклопедических словарей:[]

- Википедия

- Философия: Энциклопедический словарь. — М.: Гардарики. Под редакцией А.А. Ивина. 2004.

- БСЭ, 1969-1978

См. также[]

- Логическая истинность

- Апория

- АНТИНОМИЯ

- Парадокс логический

- Вопрос

- Диалектика

- Диалектическая логика

Литература[]

- Л.Витгенштейн. Логико-философский трактат

- Чёрч Α., Введение в математическую логику, пер. с англ., [т.] 1, [M.], 1960, § 15, 19, 23.

- Никлас Луман. Тавтология и парадокс в самоописаниях современного общества.

Ссылки[]

Toggle main menu visibility

А.А. Ивин, А.Л. Никифоров

ТАВТОЛОГИЯ

– в обычном языке: повторение того, что уже было сказано. Напр.: «Жизнь есть жизнь». «Не повезет, так не повезет». Т. бессодержательна и пуста, она не несет никакой информации, и от нее стремятся избавиться как от ненужного балласта, загромождающего речь и затрудняющего общение.

С 20-х годов этого века слово Т. (по предложению Л. Витгенштейна) стало широко использоваться для характеристики логических законов. Став логическим термином, оно получило строгие определения применительно к отдельным разделам логики. В общем случае логическая Т. – это выражение, остающееся истинным независимо от того, о какой области объектов идет речь, или «всегда истинное выражение». Все законы логики являются логическими Т. Если в формуле, представляющей закон, заменить переменные любыми постоянными выражениями соответствующей категории, эта формула превратится в истинное высказывание. Напр., в формулу «p v р» («р или не-p»), представляющую закон исключенного третьего, вместо переменной должны подставляться высказывания, т. е. выражения языка, являющиеся истинными или ложными. Результаты таких подстановок: «Дождь идет или не идет», «Два плюс два равно нулю или не равно нулю» и т. п. Каждое из этих сложных высказываний является истинным.

Тавтологический характер законов логики послужил отправным пунктом для ряда ошибочных их истолкований. Т. не описывает никакого реального положения вещей, она совместима с любым таким положением. Немыслима ситуация, сопоставлением с которой Т. можно было бы опровергнуть. Эти особенности Т. были истолкованы как несомненное доказательство отсутствия к.-л. связи законов логики с действительностью. Такое исключительное положение законов логики среди других предложений подразумевает прежде всего, что законы логики представляют собой априорные, известные до всякого опыта истины. Они не являются бессмысленными, но вместе с тем не имеют и содержательного смысла. Их невозможно ни подтвердить, ни опровергнуть ссылкой на опыт, поскольку они не несут никакой информации. Если бы это представление о логических законах было верным, они по самой своей природе отличались бы от законов других наук, описывающих действительность и что-то говорящих о ней. Однако мысль об информационной пустоте логических законов является ошибочной. В ее основе лежит крайне узкое истолкование опыта, способного подтверждать научные утверждения и законы. Этот опыт сводится к фрагментарным, изолированным ситуациям и фактам. Законы же логики черпают свое обоснование из предельно широкого опыта мыслительной, теоретической деятельности, из конденсированного опыта всей истории человеческого познания.

Т. в логике иногда наз. также разновидность порочного круга, логической ошибки, заключающейся в том, что определяемое понятие характеризуется посредством самого себя или при доказательстве некоторого положения в качестве аргумента используется само это положение. Напр., определение «небрежность есть небрежное отношение к окружающим людям и предметам» является тавтологичным.

Источник: Ивин А. А., Никифоров А. Л. Словарь по логике — М.: Туманит, изд. центр ВЛАДОС, 1997. — 384 с.

Комментарии для сайта Cackle

тавтология

- тавтология

-

в обычном языке: повторение того, что уже было сказано. Напр.: «Жизнь есть жизнь». «Не повезет, так не повезет». Т. бессодержательна и пуста, она не несет никакой информации, и от нее стремятся избавиться как от ненужного балласта, загромождающего речь и затрудняющего общение.

С 20-х годов этого века слово Т. (по предложению Л. Витгенштейна) стало широко использоваться для характеристики логических законов. Став логическим термином, оно получило строгие определения применительно к отдельным разделам логики. В общем случае логическая Т. — это выражение, остающееся истинным независимо от того, о какой области объектов идет речь, или «всегда истинное выражение». Все законы логики являются логическими Т. Если в формуле, представляющей закон, заменить переменные любыми постоянными выражениями соответствующей категории, эта формула превратится в истинное высказывание. Напр., в формулу «p v тавтология р» («р или не-p»), представляющую закон исключенного третьего, вместо переменной должны подставляться выс-казывания, т. е. выражения языка, являющиеся истинными или ложными. Результаты таких подстановок: «Дождь идет или не идет», «Два плюс два равно нулю или не равно нулю» и т. п. Каждое из этих сложных высказываний является истинным.

Тавтологический характер законов логики послужил отправным пунктом для ряда ошибочных их истолкований. Т. не описывает никакого реального положения вещей, она совместима с любым таким положением. Немыслима ситуация, сопоставлением с которой Т. можно было бы опровергнуть. Эти особенности Т. были истолкованы как несомненное доказательство отсутствия к.-л. связи законов логики с действительностью. Такое исключительное положение законов логики среди других предложений подразумевает прежде всего, что законы логики представляют собой априорные, известные до всякого опыта истины. Они не являются бессмысленными, но вместе с тем не имеют и содержательного смысла. Их невозможно ни подтвердить, ни опровергнуть ссылкой на опыт, поскольку они не несут никакой информации. Если бы это представление о логических законах было верным, они по самой своей природе отличались бы от законов других наук, описывающих действительность и что-то говорящих о ней. Однако мысль об информационной пустоте логических законов является ошибочной. В ее основе лежит крайне узкое истолкование опыта, способного подтверждать научные утверждения и законы. Этот опыт сводится к фрагментарным, изолированным ситуациям и фактам. Законы же логики черпают свое обоснование из предельно широкого опыта мыслительной, теоретической деятельности, из конденсированного опыта всей истории человеческого познания.

Т. в логике иногда наз. также разновидность порочного круга, логической ошибки, заключающейся в том, что определяемое понятие характеризуется посредством самого себя или при доказательстве некоторого положения в качестве аргумента используется само это положение. Напр., определение «небрежность есть небрежное отношение к окружающим людям и предметам» является тавтологичным.

Словарь по логике. — М.: Туманит, изд. центр ВЛАДОС.

.

1997.

Синонимы:

Полезное

Смотреть что такое «тавтология» в других словарях:

-

тавтология — тавтология … Орфографический словарь-справочник

-

Тавтология — (греческое tautologéō «говорю то же самое») термин античной стилистики, обозначающий повторение однозначных или тех же слов. Античная стилистика подводит многословие речи под три понятия: периссология накопление одинаковых по значению слов, напр … Литературная энциклопедия

-

ТАВТОЛОГИЯ — (греч., от tauto то же, и logos слово). Выражение одной и той же идеи различными однозначащими словами; ненужное повторение в других выражения сказанного уже раньше. Словарь иностранных слов, вошедших в состав русского языка. Чудинов А.Н., 1910.… … Словарь иностранных слов русского языка

-

ТАВТОЛОГИЯ — в обычном языке: повторение того, что уже было сказано. Напр.: «Стол есть стол». Т. бессодержательна и пуста, она не несет никакой информации, и от нее стремятся избавиться как от ненужного балласта, загромождающего речь и затрудняющего общение.… … Философская энциклопедия

-

Тавтология — Тавтология: Тавтология (риторика) (от др. греч. ταυτολογία) риторическая фигура, представляющая собой повторение одних и тех же или близких по смыслу слов. Тавтология (логика) тождественно истинное высказывание, инвариантное… … Википедия

-

тавтология — повторение, ошибка, масло масляное, высказывание, круг, суждение Словарь русских синонимов. тавтология масло масляное (разг.) Словарь синонимов русского языка. Практический справочник. М.: Русский язык. З. Е. Александрова. 2011 … Словарь синонимов

-

Тавтология — Тавтология ♦ Tautologie Суждение, которое всегда истинно – либо потому, что предикат лишь повторяет субъект («Бог есть Бог»), либо потому, что оно остается справедливым независимо от своего содержания и даже независимо от истинного значения… … Философский словарь Спонвиля

-

Тавтология — ТАВТОЛОГИЯ повторение одних и тех же слов, выражений и т. п. как, например, в былине о Соловье разбойнике: Под Черниговым силушки черным черно, Черным черно, как черна ворона. Тавтология прием чрезвычайно употребительный в так наз … Словарь литературных терминов

-

тавтология — и, ж. tautologie f. 1. Повторное обозначение уже названного понятия словом или выражением, не уточняющим смысла выраженного понятия (используется как стилистический прием). БАС 1. Если одного общего места мало, то примемся за тавтологию этого… … Исторический словарь галлицизмов русского языка

-

ТАВТОЛОГИЯ — (от греческого tauto то же самое и logos слово), содержательная избыточность высказывания, проявляющаяся в сочетании или повторении одних и тех же или близких по смыслу слов ( истинная правда , целиком и полностью ); может усиливать эмоциональное … Современная энциклопедия

-

ТАВТОЛОГИЯ — (от греч. tauto то же самое и logos слово) ..1) сочетание или повторение одних и тех же или близких по смыслу слов ( истинная правда , целиком и полностью , яснее ясного )2)] Явный круг в определении, доказательстве и пр. (лат. idem per idem то… … Большой Энциклопедический словарь