From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the social psychology term. For the legal term, see Fundamental error.

In social psychology, fundamental attribution error (FAE), also known as correspondence bias or attribution effect, is a cognitive attribution bias where observers under-emphasize situational and environmental explanations for the behavior of an actor while overemphasizing dispositional- and personality-based explanations. This effect has been described as «the tendency to believe that what people do reflects who they are»,[1] that is, to overattribute their behaviors (what they do or say) to their personality and underattribute them to the situation or context. The error is in seeing someone’s actions as solely reflective of their personality rather than somewhat reflective of it and also largely prompted by circumstances. It involves a type of circular reasoning in which the answer to the question «why would they do that» is only «because they would do that.» Although things like personality differences and predispositions are in fact real, the fundamental attribution error is an error because it misinterprets their effects.

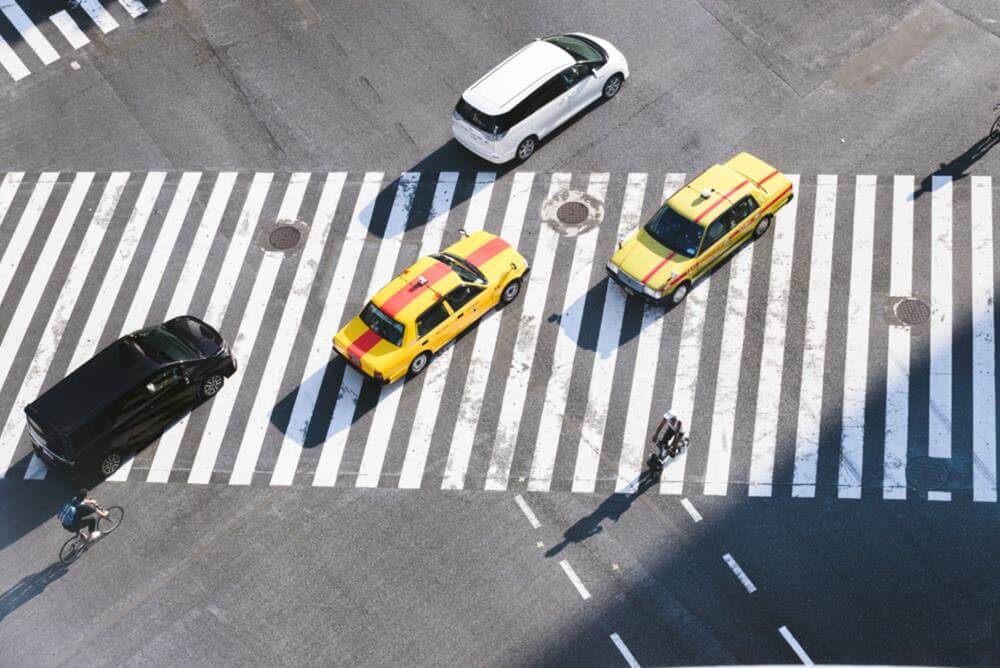

As an example of the behavior which attribution error theory seeks to explain, consider the situation where Alice, a driver, is cut off in traffic by Bob. Alice attributes Bob’s behavior to his fundamental personality; e.g., He thinks only of himself, he is selfish, he is an unskilled driver. She does not think it is situational; e.g., He is going to miss his flight, his wife is giving birth at the hospital, his daughter is convulsing at school. Alice might well make the opposite mistake and excuse herself by saying she was influenced by situational causes; e.g., I am late for my job interview, I must pick up my son for his dental appointment, rather than thinking she has a character flaw.[2]

Origin[edit]

Etymology[edit]

The phrase was coined by Lee Ross[3] 10 years after an experiment by Edward E. Jones and Victor Harris in 1967.[4] Ross argued in a popular paper that the fundamental attribution error forms the conceptual bedrock for the field of social psychology. Jones wrote that he found Ross’s phrase «overly provocative and somewhat misleading», and also joked: «Furthermore, I’m angry that I didn’t think of it first.»[5] Some psychologists, including Daniel Gilbert, have used the phrase «correspondence bias» for the fundamental attribution error.[5] Other psychologists have argued that the fundamental attribution error and correspondence bias are related but independent phenomena, with the former being a common explanation for the latter.[6]

1967 demonstration study[edit]

Jones and Harris hypothesized, based on the correspondent inference theory, that people would attribute apparently freely chosen behaviors to disposition and apparently chance-directed behaviors to situation. The hypothesis was confounded by the fundamental attribution error.[4]

Subjects in an experiment read essays for and against Fidel Castro. Then they were asked to rate the pro-Castro attitudes of the writers. When the subjects believed that the writers freely chose positions for or against Castro, they would normally rate the people who liked Castro as having a more positive attitude towards Castro. However, contradicting Jones and Harris’ initial hypothesis, when the subjects were told that the writers’ positions were determined by a coin toss, they still rated writers who spoke in favor of Castro as having, on average, a more positive attitude towards Castro than those who spoke against him. In other words, the subjects were unable to properly see the influence of the situational constraints placed upon the writers; they could not refrain from attributing sincere belief to the writers. The experimental group provided more internal attributions towards the writer.

Criticism[edit]

The hypothesis that people systematically overattribute behavior to traits (at least for other people’s behavior) is contested. A 1986 study tested whether subjects over-, under-, or correctly estimated the empirical correlation among behaviors. (ie traits, see trait theory)[7] They found that estimates of correlations among behaviors correlated strongly with empirically-observed correlations among these behaviors. Subjects were sensitive to even very small correlations, and their confidence in the association tracked how far they were discrepant (i.e., if they knew when they did not know), and was higher for the strongest relations. Subjects also showed awareness of the effect of aggregation over occasions and used reasonable strategies to arrive at decisions. Epstein concluded that «Far from being inveterate trait believers, as has been previously suggested, [subjects’] intuitions paralleled psychometric principles in several important respects when assessing relations between real-life behaviors.»[7]

A 2006 meta-analysis found little support for a related bias, the actor-observer asymmetry, in which people attribute their own behavior more to the environment, but others’ behavior to individual attributes.[8] The implications for the fundamental attribution error, the author explained, were mixed. He explained that the fundamental attribution error has two versions:

- Observers make person-focused attributions more than environmental attributions for actor behavior;

- Observers will mistakenly overestimate the influence of personal factors on actor behavior.

The meta-analysis concluded that existing weight of evidence does not support the first form of the fundamental attribution error, but does support the second.

Explanations[edit]

Several theories predict the fundamental attribution error, and thus both compete to explain it, and can be falsified if it does not occur. Some examples include:

- Just-world fallacy. The belief that people get what they deserve and deserve what they get, the concept of which was first theorized by Melvin J. Lerner in 1977.[9] Attributing failures to dispositional causes rather than situational causes—which are unchangeable and uncontrollable—satisfies our need to believe that the world is fair and that we have control over our lives. We are motivated to see a just world because this reduces our perceived threats,[10][11] gives us a sense of security, helps us find meaning in difficult and unsettling circumstances, and benefits us psychologically.[12] However, the just-world hypothesis also results in a tendency for people to blame and disparage victims of an accident or a tragedy, such as rape[13][14] and domestic abuse,[15] to reassure themselves of their insusceptibility to such events. People may even blame the victim’s faults in a «past life» to pursue justification for their bad outcome.[16][page needed]

- Salience of the actor. We tend to attribute an observed effect to potential causes that capture our attention. When we observe other people, the person is the primary reference point while the situation is overlooked as if it is nothing but mere background. As such, attributions for others’ behavior are more likely to focus on the person we see, not the situational forces acting upon that person that we may not be aware of.[17][18][19] (When we observe ourselves, we are more aware of the forces acting upon us. Such a differential inward versus outward orientation[20] accounts for the actor–observer bias.)

- Lack of effortful adjustment. Sometimes, even though we are aware that the person’s behavior is constrained by situational factors, we still commit the fundamental attribution error.[4] This is because we do not take into account behavioral and situational information simultaneously to characterize the dispositions of the actor.[21] Initially, we use the observed behavior to characterize the person by automaticity.[22][23][24][25][26] We need to make deliberate and conscious effort to adjust our inference by considering the situational constraints. Therefore, when situational information is not sufficiently taken into account for adjustment, the uncorrected dispositional inference creates the fundamental attribution error. This would also explain why people commit the fundamental attribution error to a greater degree when they’re under cognitive load; i.e. when they have less motivation or energy for processing the situational information.[27]

- Culture. It has been suggested cultural differences occur in attribution error:[28] people from individualistic (Western) cultures are reportedly more prone to the error while people from collectivistic cultures are less prone.[29] Based on cartoon-figure presentations to Japanese and American subjects, it has been suggested that collectivist subjects may be more influenced by information from context (for instance being influenced more by surrounding faces in judging facial expressions[30]). Alternatively, individualist subjects may favor processing of focal objects, rather than contexts.[31] Others suggest Western individualism is associated with viewing both oneself and others as independent agents, therefore focusing more on individuals rather than contextual details.[32]

Versus correspondence bias[edit]

The fundamental attribution error is commonly used interchangeably with «correspondence bias» (sometimes called «correspondence inference»), although this phrase refers to a judgment which does not necessarily constitute a bias, which arises when the inference drawn is incorrect, e.g. dispositional inference when the actual cause is situational). However, there has been debate about whether the two terms should be distinguished from each other. Three main differences between these two judgmental processes have been argued:

- They seem to be elicited under different circumstances, as both correspondent dispositional inferences and situational inferences can be elicited spontaneously.[33] Attributional processing, however, seems to only occur when the event is unexpected or conflicting with prior expectations. This notion is supported by a 1994 study, which found that different types of verbs invited different inferences and attributions.[34] Correspondence inferences were invited to a greater degree by interpretative action verbs (such as «to help») than state action or state verbs, thus suggesting that the two are produced under different circumstances.

- Correspondence inferences and causal attributions also differ in automaticity. Inferences can occur spontaneously if the behavior implies a situational or dispositional inference, while causal attributions occur much more slowly.[35]

- It has also been suggested that correspondence inferences and causal attributions are elicited by different mechanisms. It is generally agreed that correspondence inferences are formed by going through several stages. Firstly, the person must interpret the behavior, and then, if there is enough information to do so, add situational information and revise their inference. They may then further adjust their inferences by taking into account dispositional information as well.[27][36] Causal attributions however seem to be formed either by processing visual information using perceptual mechanisms, or by activating knowledge structures (e.g. schemas) or by systematic data analysis and processing.[37] Hence, due to the difference in theoretical structures, correspondence inferences are more strongly related to behavioral interpretation than causal attributions.

Based on the preceding differences between causal attribution and correspondence inference, some researchers argue that the fundamental attribution error should be considered as the tendency to make dispositional rather than situational explanations for behavior, whereas the correspondence bias should be considered as the tendency to draw correspondent dispositional inferences from behavior.[38][39] With such distinct definitions between the two, some cross-cultural studies also found that cultural differences of correspondence bias are not equivalent to those of fundamental attribution error. While the latter has been found to be more prevalent in individualistic cultures than collectivistic cultures, correspondence bias occurs across cultures,[40][41][42] suggesting differences between the two phrases. Further, disposition correspondent inferences made to explain the behavior of nonhuman actors (e.g., robots) do not necessarily constitute an attributional error because there is little meaningful distinction between the interior dispositions and observable actions of machine agents.[43]

See also[edit]

- Attribution (psychology)

- Base rate fallacy

- Cognitive miser

- Dispositional attribution

- Explanatory style

Cognitive biases[edit]

- Actor-observer asymmetry

- Attributional bias

- Cognitive bias

- Defensive attribution hypothesis

- False consensus effect

- Group attribution error

- List of cognitive biases

- Locus of control

- Omission bias

- Ultimate attribution error

- Extrinsic incentives bias

References[edit]

- ^ Bicchieri, Cristina. «Scripts and Schemas». Coursera — Social Norms, Social Change II. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ «Fundamental Attribution Error». Ethics Unwrapped. McCombs School of Business, The University of Texas at Austin. 2018.

- ^ Ross, L. (1977). «The intuitive psychologist and his shortcomings: Distortions in the attribution process». In Berkowitz, L. (ed.). Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 10. New York: Academic Press. pp. 173–220. ISBN 978-0-12-015210-0.

- ^ a b c Jones, E. E.; Harris, V. A. (1967). «The attribution of attitudes». Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 3 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(67)90034-0.

- ^ a b Gilbert, D. T. (1998). «Speeding with Ned: A personal view of the correspondence bias» (PDF). In Darley, J. M.; Cooper, J. (eds.). Attribution and social interaction: The legacy of E. E. Jones (PDF). Washington, DC: APA Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-09.

- ^ Gawronski, Bertram (2004). «Theory-based bias correction in dispositional inference: The fundamental attribution error is dead, long live the correspondence bias» (PDF). European Review of Social Psychology. 15 (1): 183–217. doi:10.1080/10463280440000026. S2CID 39233496. Archived from the original on 2016-06-01.

- ^ a b Epstein, Seymour; Teraspulsky, Laurie (1986). «Perception of cross-situational consistency». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 50 (6): 1152–1160. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.50.6.1152. PMID 3723332.

- ^ Malle, Bertram F. (2006). «The actor-observer asymmetry in attribution: A (surprising) meta-analysis». Psychological Bulletin. 132 (6): 895–919. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.895. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 17073526.

- ^ Lerner, M. J.; Miller, D. T. (1977). «Just-world research and the attribution process: Looking back and ahead». Psychological Bulletin. 85 (5): 1030–1051. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.85.5.1030.

- ^ Burger, J. M. (1981). «Motivational biases in the attribution of responsibility for an accident: A meta-analysis of the defensive-attribution hypothesis». Psychological Bulletin. 90 (3): 496–512. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.90.3.496. S2CID 51912839.

- ^ Walster, E (1966). «Assignment of responsibility for an accident». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 3 (1): 73–79. doi:10.1037/h0022733. PMID 5902079. S2CID 26708943.

- ^ Gilbert, D. T.; Malone, P. S. (1995). «The correspondence bias» (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 117 (1): 21–38. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.21. PMID 7870861. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-12-11.

- ^ Abrams, D.; Viki, G. T.; Masser, B.; Bohner, G. (2003). «Perceptions of stranger and acquaintance rape: The role of benevolent and hostile sexism in victim blame and rape proclivity». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 84 (1): 111–125. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.111. PMID 12518974. S2CID 45655502.

- ^ Bell, S. T.; Kuriloff, P. J.; Lottes, I. (1994). «Understanding attributions of blame in stranger-rape and date-rape situations: An examinations of gender, race, identification, and students’ social perceptions of rape victims». Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 24 (19): 1719–1734. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1994.tb01571.x. S2CID 144894634.

- ^ Summers, G.; Feldman, N. S. (1984). «Blaming the victim versus blaming the perpetrator: An attributional analysis of spouse abuse». Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2 (4): 339–347. doi:10.1521/jscp.1984.2.4.339.

- ^ Woogler, R. J. (1988). Other lives, other selves: A Jungian psychotherapist discovers past lives. New York, Bantam.

- ^ Lassiter, F. D.; Geers, A. L.; Munhall, P. J.; Ploutz-Snyder, R. J.; Breitenbecher, D. L. (2002). «Illusory causation: Why it occurs». Psychological Science. 13 (4): 299–305. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2002..x. PMID 12137131. S2CID 1807297.

- ^ Robinson, J.; McArthur, L. Z. (1982). «Impact of salient vocal qualities on causal attribution for a speaker’s behavior». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 43 (2): 236–247. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.43.2.236.

- ^ Smith, E. R.; Miller, F. D. (1979). «Salience and the cognitive appraisal in emotion». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 48 (4): 813–838. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.48.4.813. PMID 3886875.

- ^ Storms, M. D. (1973). «Videotape and the attribution process: Reversing actors’ and observers’ points of view». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 27 (2): 165–175. doi:10.1037/h0034782. PMID 4723963. S2CID 17120868.

- ^ Gilbert, D. T. (2002). Inferential correction. In T. Gilovich, D. W. Griffin, & D. Kahneman (Eds.), Heuristics and biases: The psychology of intuitive judgment. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Carlston, D. E.; Skowronski, J. J. (1994). «Savings in the relearning of trait information as evidence for spontaneous inference generation». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 66 (5): 840–880. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.66.5.840.

- ^ Moskowitz, G. B. (1993). «Individual differences in social categorization: The influence of personal need for structure on spontaneous trait inferences». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 65: 132–142. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.65.1.132.

- ^ Newman, L. S. (1993). «How individuals interpret behavior: Idiocentrism and spontaneous trait inference». Social Cognition. 11 (2): 243–269. doi:10.1521/soco.1993.11.2.243.

- ^ Uleman, J. S. (1987). «Consciousness and control: The case of spontaneous trait inferences». Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 13 (3): 337–354. doi:10.1177/0146167287133004. S2CID 145734862.

- ^ Winter, L.; Uleman, J. S. (1984). «When are social judgements made? Evidence for the spontaneousness of trait inferences». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 47 (2): 237–252. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.47.2.237. PMID 6481615. S2CID 9307725.

- ^ a b Gilbert, D. T. (1989). Thinking lightly about others: Automatic components of the social inference process. In J. S. Uleman & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), Unintended thought (pp. 189–211). New York, Guilford Press.

- ^ Lagdridge, Darren; Trevor Butt (September 2004). «The fundamental attribution error: A phenomenological critique». British Journal of Social Psychology. 43 (3): 357–369. doi:10.1348/0144666042037962. PMID 15479535.

- ^ Miller, J. G. (1984). «Culture and the development of everyday social explanation» (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 46 (5): 961–978. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.46.5.961. PMID 6737211.

- ^ Masuda, T.; Ellsworth, P. C.; Mesquita, B.; Leu, J.; Tanida, S.; van de Veerdonk, E. (2008). «Placing the face in context: Cultural differences in the perception of facial emotion» (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 94 (3): 365–381. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.3.365. PMID 18284287.

- ^ Masuda, T.; Nisbett, R. E. (2001). «Attending holistically vs. analytically: Comparing the context sensitivity of Japanese and Americans». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 81 (5): 922–934. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.5.922. PMID 11708567. S2CID 8850771.

- ^ Markus, H. R.; Kitayama, S. (1991). «Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation». Psychological Review. 98 (2): 224–253. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.320.1159. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224.

- ^ Hamilton, D. L. (1988). Causal attributions viewed from an information-processing perspective. In D. Bar-Tal & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.) The social psychology of knowledge. (Pp. 369-385.) Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Semin, G. R.; Marsman, J. G. (1994). «Multiple inference-inviting properties» of interpersonal verbs: Event instigation, dispositional inference and implicit causality». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 67 (5): 836–849. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.5.836.

- ^ Smith, E. R.; Miller, F. D. (1983). «Mediation among attributional inferences and comprehension processes: Initial findings and a general method». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 44 (3): 492–505. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.44.3.492.

- ^ Krull, D. S.; Dill, J. C. (1996). «Thinking first and responding fast: Flexibility in social inference processes». Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 22 (9): 949–959. doi:10.1177/0146167296229008. S2CID 144727564.

- ^ Anderson, C. A., Krull, D. S., & Weiner, B. (1996). Explanations: Processes and consequences. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (pp. 221-296). New York, Guilford.

- ^ Hamilton, D. L. (1998). Dispositional and attributional inferences in person perception. In J. M. Darley & J. Cooper (Eds.), Attribution and social interaction (pp. 99-114). Washington, DC, American Psychological Association.

- ^ Krull, Douglas S. (2001). «On partitioning the fundamental attribution error: Dispositionalism and the correspondence bias». In Moskowitz, Gordon B. (ed.). Cognitive Social Psychology: The Princeton Symposium on the Legacy and Future of Social Cognition. Mahwah, New Jersey, USA: Psychology Press. pp. 211–227. ISBN 978-1135664251.

- ^ Masuda, T., & Kitayama, S. (1996). Culture-specificity of correspondence bias: Dispositional inference in Japan. Paper presented at the 13th Congress of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

- ^ Choi, I.; Nisbett, R. E. (1998). «Situational salience and cultural differences in the correspondence bias and actor-observer bias» (PDF). Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 24 (9): 949–960. doi:10.1177/0146167298249003. hdl:2027.42/68364. S2CID 145811653.

- ^ Krull, D. S.; Loy, M. H.; Lin, J.; Wang, C. F.; Chen, S.; Zhao, X. (1999). «The fundamental attribution error: Correspondence bias in individualist and collectivist cultures». Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 25 (10): 1208–1219. doi:10.1177/0146167299258003. S2CID 143073366.

- ^ Edwards, Autumn; Edwards, Chad (January 4, 2022). «Does the Correspondence Bias Apply to Social Robots?: Dispositional and Situational Attributions of Human Versus Robot Behavior». Frontiers in Robotics and AI. 8: 404. doi:10.3389/frobt.2021.788242. PMC 8764179. PMID 35059443.

Further reading[edit]

- Heider, Fritz. (1958). The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations. New York, John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-36833-4.

- Gleitman, H., Fridlund, A., & Reisberg D. (1999). Psychology webBOOK: Psychology Fifth Edition / Basic Psychology Fifth Edition. W. W. Norton and Company. Accessed online 18 April 2006.

External links[edit]

- Detailed explanations by Lee Ross and Richard Nisbett

Susan has an interview with Company ABC at 1pm. She catches the train and when she is getting off, she gets pushed by another passenger who is running for another train. In the process, Susan twists and sprains her ankle. Filled with pain but desire, she hops along as best as she can to get to the interview on time.

When she arrives, she is over 15 minutes late. Fred and Louise who are the interviewees say to each other, ‘she’s late and not very punctual. I don’t know if we can trust her to come to work every day on time’. ‘It must be something in her character’.

Despite having a good interview, Susan doesn’t get the job. Fred and Louise blame the poor punctuality on her character. In other words, they think it’s a distributional attribution. Perhaps she is just a disorganised person, but that wouldn’t fit well into the role.

Yet, the real reason was a situational attribution. She sprained her ankle. A situation she could not have foreseen. In turn, there is a fundamental attribution error.

Actors and actresses who play a character on the screen can often be confused with their on-screen character. For instance, Jennifer Aniston may be seen to have the same characteristics as Rachel from Friends.

This can lead to a fundamental attribution error. We may consider Jennifer Aniston and Rachel as one of the same. Her actions may replicate what Rachel would do. However, they are not the same. Jennifer Aniston is merely portraying Rachael in a situational attribution. Those characteristics are part of acting and are limited to that situation.

Many actors and actresses face such issues in real life. They get confused between the human and the character. We may expect an actor or actress who portrays an evil villain to be evil and devious in real life. However, we are attributing that to the actor or actress’s situation by which they are performing, not their dispositional attributes.

Let’s say your friend Jake takes you to a party. He introduces you to his other friend Aaron. He seems disinterested and unwilling to talk to you. Aaron is rude, abrupt, and generally unpleasant to be around.

It would be fair to conclude that Aaron is simply not a nice person. You may not see why he is friends with Jake in the first place. ‘Why are you friends with this guy’? You might say.

On the surface, it may seem like Aaron isn’t a nice person. However, what we haven’t seen is the fact that his mother passed away last week and he had just been fired from his job.

What we see is a fundamental attribution error. We may assign his bad behaviour towards his personality, or, dispositional attributes. Yet his behaviour is better explained by his situation instead.

We tend to attribute behaviour to dispositional attributes. In other words, an individual’s character. The reason is simple. We don’t have an idea of the other persons situation and what they are going through. So, what may be a situational attribute, we often blame as that of the persons disposition.

At the same time, it’s important to acknowledge that the opposite can also occur. In other words, a situational attribute can be mistaken for a distortional attribute.

In order to avoid either of these, it is first important to acknowledge that we make such errors. Once we understand that we are prone to them, we can be pro-active when they occur.

When we get angry at the shopper cutting in, or our boss reprimanding us, it’s important for us to first consider the circumstances by which the situation unfolded. We don’t know what might be going on in their home life, so there may be more to the situation that it seems.

Sometimes it is impossible to understand others’ situation. We cannot know that the driver who just cut you up is in a rush to see their dying father, or the guy who barged past you were in a state after losing his job.

By trying to understand that it is not necessarily the individual’s disposition, we can not only calm ourselves down but also rationalise the situation.

We can get annoyed at a person’s actions and therefore take the anger out on them. This can be counter-productive, especially when there is a fundamental attribution error.

There’s been a lot written about cognitive biases in the last decade. If you walk into the Psychology section of Barnes of Noble today or browse Amazon for «decision-making,» you’re sure to see a library of books about how irrational humans can be.

Many cognitive biases affect humans and their everyday actions, like confirmation bias and overconfidence. But the most important, and troubling, error that professionals tend to make in their thinking may be the fundamental attribution error.

Cognitive biases such as these often shape how an individual interacts with the world around them. In the world of business, understanding these biases and becoming aware of the ways that they influence your behavior is vital to becoming a better manager.

What Is the Fundamental Attribution Error?

The fundamental attribution error refers to an individual’s tendency to attribute another’s actions to their character or personality, while attributing their behavior to external situational factors outside of their control. In other words, you tend to cut yourself a break while holding others 100 percent accountable for their actions.

For instance, if you’ve ever chastised a «lazy employee» for being late to a meeting and then proceeded to make an excuse for being late yourself that same day, you’ve made the fundamental attribution error.

The fundamental attribution error exists because of how people perceive the world. While you have at least some idea of your character, motivations, and situational factors that affect your day-to-day, you rarely know everything that’s going on with someone else. Similar to confirmation and overconfidence biases, its impact on business and life can be reduced by taking several measures.

Fundamental Attribution Error Examples

It’s clear to see how the fundamental attribution error (FAE) can impact your personal life, but it’s important to recognize the influence it can have on your work, as well. Whether you’re an employee or manager, cognitive biases, like the FAE, can play a role in how you interact with others in the workplace and how you make key business decisions.

In working with your colleagues, for example, you probably form a general impression of their character based on pieces of a situation, but never see the whole picture. While it would be nice to give them the benefit of the doubt, your brain tends to use limited information to make judgments.

Within organizations, FAE can cause everything from arguments to firings and ruptures in organizational culture. In fact, it’s at the root of any misunderstanding in which human motivations have the potential to be misinterpreted.

For example, think back to the «lazy employee.» Since she was late to an important meeting, you might be inclined to form a judgment of her character based on this one action alone. It’s possible, however, that her behavior is due to several external, rather than internal, factors. For instance, any number of situational factors could have caused her to run behind schedule, such as a family emergency or traffic jam, which have nothing to do with the quality of her character.

In action, forming impressions of a person’s character based on limited information can have long-lasting effects. Now that you perceive this person as «lazy,» your opinions of her may begin to shift over time. Unless the opportunity arises for you to get to know your employee better, you may always view her in a negative light.

How to Avoid the Fundamental Attribution Error

Think of the last time you thought a co-worker should be fired or a customer service representative was incompetent. How often have you really tried to understand the situational factors that could be affecting this person’s work? Probably not often.

The fundamental attribution error is so prevalent because it’s rooted in psychology, so completely overcoming it can be difficult. One tool that can be helpful in combating FAE is gratitude. When you become resentful at someone for a bad «quality» they demonstrate, try to make a list of five positive qualities the person also exhibits. This will help balance out your perspective and can help you view your co-worker as a whole person instead of through the lens of a single negative quality.

Another method is to practice becoming more emotionally intelligent. Emotional intelligence has become a buzzword in the business world over the past 20 to 30 years, but it involves practicing self-awareness, empathy, self-regulation, and other methods of becoming more objective in the service of one’s long-term interests and the interests of others. Practicing empathy, in particular, such as having discussions with co-workers about their opinions on projects and life out of the office, is a good first step.

FAE is impossible to overcome completely. But with a combination of awareness and a few small tools and tactics, you can be more gracious and empathic with your co-workers. In fact, being able to acknowledge cognitive biases like FAE and make the conscious effort to limit their effects is an essential component of becoming a better manager.

Are you interested in improving your managerial skills? Explore our eight-week online course Management Essentials and gain the skills and strategies to excel in decision-making, implementation, organizational learning, and change management.

This post was updated on February 14, 2020. It was originally published on June 8, 2017.

The fundamental attribution error is a cognitive bias that causes people to underestimate the influence of environment-based situational factors on people’s behavior, and to overestimate the influence of personality-based dispositional factors.

Essentially, this means that the fundamental attribution error causes people to assume that other people’s actions are less affected by their environment than they actually are, and to assume that those actions are more affected by their personality than they actually are.

For example, the fundamental attribution error can cause someone to assume that if some stranger looks angry, then they must be an angry person in general, even though this person might have been driven to temporary anger by something, such as someone else being rude to them.

The fundamental attribution error can significantly influence how people, including yourself, judge others, so it’s important to understand it. As such, in the following article you will learn more about the fundamental attribution error, and see what you can do to account for it properly.

Examples of the fundamental attribution error

One notable example of the fundamental attribution error appears in the first study that focused on this phenomenon, published in 1967 by Edward Jones and Victor Harris, two researchers at Duke University.

In the first and best-known of the experiments in the study, participants were given what they thought was an essay written by a student for a political science exam on a controversial topic—Fidel Castro’s Cuba. Some participants received a Pro-Castro essay and others an Anti-Castro one, and they were all asked to judge the true attitude of the essay writer toward the topic.

The experiment provided evidence of the fundamental attribution error, since participants who read the Pro-Castro essay were significantly more likely to assume that the student who wrote it was himself Pro-Castro, compared to those who read the Anti-Castro essay, even when they were told that the student who wrote the essay had no choice with regard to its topic. These findings were replicated in a follow-up experiment, where participants read what they thought was an initial draft of an opening statement for a college debate on the topic.

Since then, other research has found evidence of the fundamental attribution error in various domains. For instance, additional examples of the fundamental attribution error include the following:

- People watching TV shows often display the fundamental attribution error, when they attribute the behavior of actors on the show to their personality, rather than to the script. Essentially, this means that people sometimes assume that an actor’s behavior while in-character reflects their true personality, rather than what is dictated for them by the script. Furthermore, this effect has been shown to remain consistent even when the person who displays the fundamental attribution error watches the same actor playing two different roles; in such cases, the last scene that people view is generally the one that determines their evaluation of the actor.

- Students often display the fundamental attribution error, when they overestimate internal causes for their teachers’ expression of anger. Essentially, this means that students assume that the main reason why their teachers are angry is that they’re angry people, rather than that their environment has caused the teachers to become angry. This remains the case even when students recognize that their own actions, such as misbehavior, intentional provoking, or lack of effort, are what caused the teacher to become angry in the first place.

Note: the term ‘fundamental attribution error’ was coined by Stanford professor Lee Ross in a 1977 paper titled “The intuitive psychologist and his shortcomings: distortions in the attribution process”, where Ross discusses this phenomenon based on findings from earlier studies. This term is often abbreviated as ‘FAE’.

Why people display the fundamental attribution error

The main reason why people display the fundamental attribution error is that it serves as a type of heuristic, which is a mental shortcut that people intuitively use in order to make judgments and decisions quickly.

Specifically, the fundamental attribution error can be viewed as a heuristic, since it’s easier and faster to assume that people’s behavior is based only on their relatively stable internal traits, than it is to account for the various situational factors that could affect it, and to try and disentangle people’s actions from their intentions. Accordingly, this bias is more likely to occur when people lack the cognitive resources or motivation needed to fully consider the influence of situational factors on people’s behavior.

Furthermore, besides speeding up people’s evaluation process and reducing their cognitive load during this process, there are also other potential benefits to using this kind of heuristic.

For example, a potential benefit of the fundamental attribution error is that the cost of erroneously assuming that someone’s actions are determined primarily by their disposition, rather than by situational factors, is sometimes lower than assuming the opposite. Essentially, this means that when judging someone’s actions, it is often preferable to assume that their behavior is more affected by their personality than it actually is, than it is to assume the opposite.

In addition, other reasons can also prompt people to display the fundamental attribution error. For example, a neuroscientific study showed that one potential reason why people display this bias is that, when they try to understand other people’s intentions, they engage in mentalizing, by spontaneously processing the other person’s mental state.

Finally, note that various factors have been shown to influence the likelihood that people will display the fundamental attribution error, as well as the degree to which they display it. This includes both factors that have to do with the person making the judgment, such as their nationality or mood, as well as factors that have to do with the person who is being judged, such as whether their actions are perceived in a positive or negative manner. This is in line with research on the general attribution process, which shows that this process can be biased in various ways and for various reasons, and can be affected by various situational and personal factors.

Overall, people display the fundamental attribution error primarily because this form of thinking serves as a mental shortcut, that allows them to render judgments faster and more easily. Furthermore, other factors can also lead people to display the fundamental attribution errors; this includes, for example, the fact that it is often preferable to overestimate, rather than underestimate, the impact of personality-based factors on people’s behavior.

Accounting for the fundamental attribution error

How to avoid the fundamental attribution error

There are several things that you can do to avoid the fundamental attribution error.

First, simply learning about this phenomenon and keeping it in mind can help reduce it to some degree.

Second, in situations where you notice yourself displaying this phenomenon while judging someone, you can further reduce it by actively thinking of similar situations where it was clear that people were strongly influenced by situational factors. When doing this, you can also ask yourself if you have ever acted in a similar manner under similar circumstances, and then examine the reasons that you had for acting the way you did.

Third, you can also try to come up with a number of possible explanations—including situational ones—for the behavior of the person that you’re judging.

In addition, actively explaining the rationale behind your judgment of someone can further help you reduce the likelihood that you’ll display the fundamental attribution error. This works both by making you feel more accountable for your reasoning, and by helping you identify and avoid the mental shortcuts that lead you to display this bias in the first place.

Finally, you can also benefit from using general debiasing techniques, such as slowing down your reasoning process. In particular, you will often benefit from using debiasing techniques that are effective against similar types of cognitive biases, such as the egocentric bias and the empathy gap. This includes, for example, trying to consider the situation from the other person’s perspective.

Overall, to avoid the fundamental attribution error, you should keep this cognitive bias in mind when judging others, and use techniques such as considering relevant past situations, coming up with multiple explanations for people’s behavior, and explaining the rationale behind your judgment; you can also use general debiasing techniques, such as slowing down your reasoning process.

Note: to avoid the fundamental attribution error, a useful principle to keep in mind is Hanlon’s razor, which suggests that when someone does something that leads to a negative outcome, you should avoid assuming that they acted out of an intentional desire to cause harm, as long as there is a plausible alternative explanation for their behavior.

How to respond to the fundamental attribution error

If you notice that someone else is displaying the fundamental attribution error, you can attempt to debias their thinking, by using similar techniques that you would use to avoid this bias yourself.

For example, you can encourage the person who’s displaying this bias to think of similar situations where they’ve acted like the person that they’re judging, because of situational factors. Similarly, you can ask the person displaying this bias to think of environment-based reasons why the person in question might be engaging in the behavior that’s being judged.

It’s important to note that such methods are intended to work primarily on people who are displaying the fundamental attribution error unintentionally, as a cognitive bias. However, some people intentionally use fallacious patterns of reasoning that are similar to this bias, for various reasons.

For example, someone might argue that a certain person who did something negative must have done so simply because they’re a bad person, rather than because they were pushed to do it by their environment, in order to promote the fundamental attribution error in others.

To handle cases where this happens, it is often best to demonstrate the logical issues with the argument in question. You can achieve this by demonstrating the issues associated with such logic using various approaches, such as explaining that people’s actions aren’t necessarily driven just by their personality, and by providing examples that support this claim.

A potential exception to this are cases where there’s an audience to the discussion where this kind of fallacious argument is being used, and you care primarily about the opinion of the audience, rather than about the opinion of the person who’s intentionally using this argument. In such cases, you might choose to focus on debiasing the audience members using the previously mentioned debiasing techniques, instead of—or in addition to—demonstrating the logical issues with such arguments.

Caveats regarding the fundamental attribution error

As with similar psychological phenomena, there are some important caveats that should be taken into account with regard to the fundamental attribution error.

First, it’s important to note that some research on the topic has called into question the degree to which people display the fundamental attribution error and related phenomena, such as the actor-observer asymmetry in attribution. Furthermore, such research has also called into question the reasons why people display these phenomena in the first place.

Second, it’s important to keep in mind that this is a complex phenomenon, that can be affected by various factors. As such, you should expect there to be significant variability with regard to the exact manner in which people display this phenomenon, in terms of factors such as how strongly they underestimate the influence of situational factors.

Related concepts

There are several psychological phenomena that are often mentioned in relation to the fundamental attribution error. These include, most notably:

- The correspondence bias. The correspondence bias is a cognitive bias that causes people to draw conclusions about a person’s disposition, based on behaviors that can be explained by situational factors. Some people use the terms ‘fundamental attribution error’ and ‘correspondence bias’ interchangeably, but the two terms refer to two separate—though closely related—phenomena.

- The actor-observer asymmetry in attribution. The actor-observer asymmetry in attribution is a cognitive bias that causes people to attribute their own behavior to situational causes and other people’s behavior to dispositional factors.

- Self-serving bias. The self-serving bias is a cognitive bias that causes people to take credit for their successes and positive behaviors by attributing them to dispositional factors, and to deny responsibility for failures and negative behaviors by attributing them to situational factors. In addition, the term ‘self-serving bias’ is sometimes used to refer to any type of cognitive bias that is prompted by a person’s desire to enhance their self-esteem.

- The ultimate attribution error. The ultimate attribution error is a cognitive bias that makes people more likely to attribute positive acts to situational factors when they’re performed by someone from an outgroup than by someone from their ingroup, and also makes people more likely to attribute negative acts to dispositional factors when they’re performed by someone from an outgroup than by someone from their ingroup.

- The just-world bias. The just-world bias is a cognitive bias that causes people to assume that people’s actions always lead to fair consequences, meaning that those who do good are eventually rewarded, while those who do evil are eventually punished. For example, the just-world hypothesis can cause someone to assume that if someone else experienced a tragic misfortune, then they must have done something to deserve it.

In addition, there are three frameworks that are often mentioned in relation to the fundamental attribution error:

- Situationism, which involves heavily favoring situational factors when it comes to explaining human behavior.

- Dispositionalism, which involves heavily favoring dispositional factors when it comes to explaining human behavior.

- Interactionism, which suggests that when it comes to explaining human behavior, both situational and dispositional factors strongly matter.

Most researchers show support for interactionism, rather than to the other frameworks, under the belief that both situational and dispositional factors play a major role in guiding human behavior.

Summary and conclusions

- The fundamental attribution error is a cognitive bias that causes people to underestimate the influence of environment-based situational factors on people’s behavior, and to overestimate the influence of personality-based dispositional factors.

- For example, the fundamental attribution error can cause someone to assume that if some stranger looks angry, then they must be an angry person in general, even though this person might have been driven to temporary anger by something, such as someone else being rude to them.

- The main reason why people display the fundamental attribution error is that it’s easier and faster to assume that people’s behavior is driven only by their personality, than to try and account for the various situational factors that could affect it.

- To avoid the fundamental attribution error, you should keep this bias in mind when judging others, and use techniques such as considering relevant past situations, coming up with multiple explanations for people’s behavior, and explaining the rationale behind your judgment; you can also use general debiasing techniques, such as slowing down your reasoning process.

- To help others avoid the fundamental attribution error, you can debias their thinking using similar techniques that you would use to debias yourself; however, if they’re using similar patterns of reasoning intentionally for some reason, it might be preferable to focus on explaining the logical issues with their argument instead.

The fundamental attribution error is a mental shortcut that involves explaining another person’s behavior in terms of their personality (rather than attributing their behavior to a situational context).

We use the fundamental attribution error because it is easier to think about something in terms of a person’s personality rather than the complex situation from which their behavior emerged.

In this sense, it is a cognitive shortcut that makes our thinking efficient.

It is also used because we often do not have detailed information about another person’s history or the various situational factors involved.

There are many examples of the fundamental attribution all around us. We may see poor people as lazy or unmotivated. Or, someone we meet for the first time seems cold and distant so we conclude they are a rude person.

Definition of Fundamental Attribution Error

Although there is some debate about who first identified the fundamental attribution error, Ross (1977) offered a very straightforward definition:

“The tendency for attributers to underestimate the impact of situational factors and to overestimate the role or dispositional factors in controlling behavior” (p. 183).

This is a cognitive bias and heuristic example (mental shortcut), which is a sub-category of the base rate fallacy.

This cognitive bias has been well-researched over the years. Interestingly, it turns out that people from an individualistic culture are more inclined to engage in the fundamental attribution error than those from a more collectivist one (Miller, 1984).

Collectivist cultures emphasize situational factors and the interdependence of people. While individualistic cultures emphasize independence and dispositional influences.

1. Getting Cut-Off in Traffic

When we get cut off in traffic, we might be inclined to yell profanities at the person and call them all sorts of names: “this person is terrible!” In this situation, we’re extrapolating from a one-off behavior and assigning them a personality based upon an isolated instance.

Nothing is more irritating than getting cut-off in traffic. Not only can it cause a serious accident and send people to the hospital, it is just bad driving etiquette. If you are like most people, you might be inclined to make a few comments about the person that just cut you off.

One common remark might be that the other person “is a bad driver.” If we analyze that comment what we see is that we are assigning a long-term attribute to someone based on one instance of their behavior. We know nothing about the person and definitely don’t have access to their driving record, but yet we have inferred that they possess the disposition of being a bad driver.

However, maybe they were just trying to avoid an accident. Or, perhaps a dog ran into the street and so they swerved out of the way.

2. A Bad First Day at Work

A person’s first day at work is a stressful time. They’re likely to behave in ways that are inconsistent with their regular personality due to the situation.

There are a lot of things that can go wrong on your first day at work. The new employee doesn’t know how things are usually done. Even finding where various departments are or understanding basic office customs can be a challenge.

Of course, it is understandable if someone might begin to feel a bit frustrated. That frustration might even boil over to an outright display of irritation that doesn’t help at all.

Our tendency to engage the fundamental attribution error would lead us to conclude the “new guy” isn’t a person that handles stress very well, or perhaps is even a hothead. These are both assigning dispositional qualities to someone based on a very small sample of their behavior.

3. The Angry Server

Anyone who has worked serving behind a bar or at a restaurant knows that serving rude people all day can take a toll. Yet, if a server finally cracks and snaps back, they’re assumed to be a rude person.

In this instance, the server shouldn’t be seen as a rude person for the rest of their life necessarily! Rather, a sympathetic interpretation would attribute the behavior to the situation (they’re sick of being treated poorly) rather than the personality of the person.

The server may, in fact, be very laid-back and has managed to absorb a lot of negativity for a long time until, as a one-off, they finally snapped and got upset. I’m sure most people would agree that this isn’t a true reflection of the person’s longer-term personality traits.

4. Entrepreneurs with the Golden Touch

Often if an entrepreneur has had one successful business, they can get very easy access to investor funds for future ventures.

The assumption of the investors is that the entrepreneur is an “excellent businessperson” who has the golden touch.

This is a fundamental attribution error because they’re making assumptions about the personality of the entrepreneur (they’re supposedly a great businessperson) rather than examining their business plan to see if it’s genuinely on solid foundations.

The same happens in reverse: if an entrepreneur’s startup business fails, chances are they’ll struggle to get funding for the next one. Here, there have been assumptions made about the businessperson’s personality without examining why the first business idea failed.

5. Poor People are Lazy

This is the quintessential fundamental attribution error. When we meet a poor person, we assume they’re lazy rather than attributing it to situational factors in their lives.

Driving by a food kitchen for the homeless can give us a view of another world. We can see others that are struggling to survive and at the worse times in their lives.

A lot of us might conclude that they are homeless because they are lazy, or perhaps because they are convicted criminals that no one wants to hire. These are all examples of the fundamental attribution error.

We have given an explanation for their predicament without knowing anything about them or their situation at all. If we were to do a little investigation, we just might discover that some of them were victims of pension fraud and so they lost all of their savings right after their company downsized and laid off thousands of managers.

The fundamental attribution error can make our explanations for the world around us a bit simplistic and at times far too harsh.

6. Being Late for a Job Interview

Nothing starts an interview off on the wrong foot than being late. It creates a bad first impression, especially given the importance of the situation, and could lead the interviewer to make assumptions about your personality.

If the person conducting the interview is like most of us, then they may conclude that the applicant is “not a punctual person.” That can also lead to the conclusion that they are irresponsible and unreliable. Ouch. None of that is helpful to someone looking for employment.

If truth be known however, the applicant got stuck in traffic because of a crash between two large delivery trucks. Or, maybe they had to take their first-grader to school and that was the morning he decided to throw an extended temper tantrum because he wasn’t allowed to wear his Batman costume.

There could be a lot of very reasonable explanations for someone being late, none of them involving dispositional characteristics.

7. Blaming the Victim

Sometimes, people will try to explain a victim’s situation by saying that it was their personality that got them into that situation. For example, we might say a girl was accosted because of the clothing she was wearing.

When enduring a great injustice there is nothing worse than having others point the finger at us and say we deserved it. It is adding insult to injury in its ugliest form.

Unfortunately, this can happen a lot. There is a tendency for people to assign blame to the victim of a crime. It has been a well-documented phenomenon in the social sciences for decades.

If a person gets mugged in an alley at night, some might say that only a fool would take that path to their car. If a colleague gets scammed in a stock market venture, then we might say they deserved it for being a greedy person.

These are very unpleasant, and unfortunate, examples of the fundamental attribution error.

8. Drinking Too Much at a Party

If the first time someone meets you you’ve had too much to drink at a party, chances are this first impression is going to last! They might not take into account situational factors.

Everyone loves a good party. Having a few drinks with friends or colleagues is a great way to release a little stress. Let’s say a friend invites us to a party on Friday evening thrown by someone we don’t really know. Of course, we say yes because it is a great way to make new friends.

You stay late at work to get a few extra things done before the weekend. About an hour after at the party you start to feel a bit queasy. We all know what happens next.

This situation is ripe for the fundamental attribution error. One person remarks to their friend that you are a lightweight. Another person comments that you drink too much.

However, what really happened is that you didn’t stop to eat after work and drank on an empty stomach. That’s a perfectly reasonable explanation, and one that involves a situational factor.

9. Trying a New Recipe When Meeting the Parents

The first meal you cook for someone is likely to have high stakes. If it works out, you’re instantly assumed to be an amazing chef. Otherwise, you might be seen as no good at cooking – and the assumption will stick!

Dating can be so much fun. The excitement of meeting someone new and learning about them can be a wonderful process. If the stars are aligned, you might just get lucky and find your soulmate.

Eventually that means meeting each other’s parents. So, because you are an excellent cook, you invite them over prepare a delicious meal that is native to their homeland. After spending a lot of time researching different recipes you find one that seems perfect.

Unfortunately, the meal is a complete disaster. It happens.

Although your partner knows you are a great cook because you have cooked for her before, her parents have a different opinion. Instead of considering the multitude of situational factors that might explain the horrible meal, they conclude that you “shouldn’t quit your day job.”

It is a clear indictment of what they consider to be a skill that you do not possess. It’s also an example of the fundamental attribution error.

10. Cultural Misunderstandings

When we travel, sometimes our impression of the culture is clouded by lack of cultural understanding. When this happens, we can erroneously attribute culturally normal behaviors as ‘rude’.

Traveling abroad can be the adventure of a lifetime. Not only do we get to see a new land and taste different cuisine, we also get to explore an unfamiliar culture and learn new ways of thinking.

That all sounds great. If we are not careful however, it can also mean that we experience some cultural misunderstandings as a result of the fundamental attribution error.

For example, in some countries it is not customary for a server to place a glass of water on the table or be emotionally expressive with patrons.

This can easily lead to tourists concluding that people in that country don’t like foreigners. This may not be true at all. It is just that the culture prescribes a different way of interacting between restaurant servers and customers. In this case, the behavior of the server leads to a scaled-up version of the fundamental attribution error.

11. Failing Exams at School

If someone we know is not doing well at school, we might conclude that they are just not a very smart person. “Not a very smart person” is an explanation that ascribes an enduring characteristic in the person. It is dispositional and signifies a long-term stable trait.

In reality however, there may be a multitude of other explanations, all of which are situational.

For example, maybe the person is living in a home environment that is stressful and makes it difficult to concentrate on studying. Perhaps that person is just not interested in academics and has a long-term goal involving sports instead. Or, maybe they are suffering from dyslexia and don’t know it yet.

The point is that there are many possible explanations for their poor academic performance other than a lack of intelligence. Unfortunately, the fundamental attribution error makes us not very understanding of others.

12. The Bad Mother

Too often, mothers are blamed and accused of being bad parents because their child is screaming or the mother has been very stern with her child.

This is an unfair assumption that outside observers make when watching on. Often, these are people who have never raised children and are too quick to judge.

Similarly, others might frown upon the mother’s sternness, without taking into account the fact that the mother has slowly escalated the consequences and didn’t just jump to being stern or harsh.

Parents, on the other hand, might watch on and not make rash assumptions about the mother being a ‘bad parent’. Rather, they might understand the situation of parents is often tough, and they may be more willing to see it as an isolated incident that they shouldn’t judge too quickly.

13. Police Bias

Police need to be particularly careful about making fundamental attribution errors. If they make assumptions about a person’s personality, they may make poor decisions that can fundamentally affect someone’s life.

If the police make assumptions about a person’s personality when deciding whether to give a warning or a fine, then they are letting fundamental attribution errors interfere with their work.

For example, if a person is quiet and nervous while talking to police, they might assume that the person is a bad person and needs to be taken off the streets. However, they may not understand that in the situation, this person is feeling uncomfortable and that’s why they’re nervous – it has nothing to do with their personality!

14. Obesity

Many people who struggle with obesity eat healthily and exercise regularly. However, they may be genetically predisposed to being overweight.

Unfortunately, many people in society assume that any obese person is overweight due to their diet and lack of exercise. This may be true for some people, but not everyone.

If you have made an assumption about an obese person’s personality based upon their weight, then we are making an attribution error. We’re attributing their weight to their personality, rather than biological factors.

15. The Great First Date

Fundamental attribution errors can also work in our favor. For example, if you make a great impression on a first date, your date might think you’re a happy-go-lucky lovely person. They clearly haven’t yet seen the real you!

Here, your date is attributing your behavior during the date to your personality (that you are a really friendly person) rather than to the fact that you were on your very best behavior due to the situation.

Over time, people who start dating start to get to know the ‘real’ version of one another (i.e. their actual longer-term personality), and the relationship starts to break down.

In fact, this is the whole reason we have dating! People date each other for months or years hoping to get to know each other at a deeper level and see a longer-term personality. If we were to get married at first sight, we might accidentally make a fundamental attribution error that we’ll surely regret later!

Other Examples of Heuristics

- Availability Heuristic Examples

- Representativeness Heuristic Examples

- Halo Effect Examples

Conclusion

Focusing on dispositional explanations of people’s behavior can lead to a fundamental attribution error. It is much easier to ascribe personal characteristics as being the source of a person’s actions.

Taking in to account situational factors is time-consuming, mentally demanding, and involves information that simply may not be available to observers.

Unfortunately, this can lead to blaming the victim of a crime, not giving others the benefit of the doubt that they deserve, and ascribing a lot of negative characteristics to people that we know nothing about.

Although it is an unfortunate bias for many, it appears to be, at least partially, a function of culture. People from collectivist cultures are less likely to engage in the fundamental attribution error due to their emphasis on understanding situational factors and the interdependence of people.

References

Cowley, E. (2005). Views from consumers next in line: the fundamental attribution error in a service setting. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 33(2), 139-152. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070304268627

Felson, R.B., & Palmore, C. (2018). Biases in blaming victims of rape and other crime.

Psychology of Violence, 8(3), 390–399. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000168

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: Wiley.

Miller, J. G. (1984). Culture and the development of everyday social explanation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(5), 961–978.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.46.5.961 PMID 6737211

Pultz, S., Teasdale, T. W., & Christensen, K. B. (2020). Contextualized attribution: How young unemployed people blame themselves and the system and the relationship between blame and subjective well-being. Nordic Psychology, 72(2), 146-167. https://doi.org/10.1080/19012276.2019.1667857 Ross, L. (1977). The intuitive psychologist and his shortcomings: Distortions in the attribution process. In Berkowitz, L. (Ed.). Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 10, (pp. 173–220). New York: Academic Press.

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

Fundamental attribution error is a bias people display when judging the behavior of others. The tendency is to over-emphasize personal characteristics and under-emphasize environmental and situational factors.

Understanding fundamental attribution errors

Fundamental attribution error – sometimes referred to as the attribution effect or correspondence bias – is a bias that was first described by social psychologist Lee Ross in 1977.

Research on the topic started much earlier, however, thanks to psychologists Fritz Heider and Gustav Ichheiser who investigated ordinary peoples’ understanding of the causes of human behavior.

In a nutshell, fundamental attribution error describes how people over-emphasize dispositional factors and downplay or ignore situational factors when judging someone’s behaviors.

Put in more simple terms, the individual believes that someone else’s personality traits are more of an influence on their actions than factors over which the person has no control.

Suppose someone is late for a meeting. Many of us may jump to the conclusion that the individual is constantly late to important events or does not take their job seriously.

We do not consider that the person could have been stuck in traffic or was required to collect a sick child from school on the way.

Conversely, when we are the ones late to a meeting, we use the excuse of being stuck in traffic and ignore what our late attendance says about us as a person.

Here, fundamental attribution error describes a double standard where we judge others harshly but do not hold our own behavior to the same account.

What is attribution?

The term attribution simply refers to how someone explains the behavior of another person.

In other words, what we attribute their behavior to. The fundamental attribution error occurs when the individual connects the cause of an individual’s action with the incorrect attribution.

There are two types to choose from:

Dispositional attribution

Where someone’s actions are explained by their beliefs, opinions, personality, or any other inherent characteristic.

For example: Tom is always late to work because he is disorganized.

Situational attribution

Where someone’s actions are explained by their circumstances, environment, or even other people.

For example: Claire lost her temper with another staff member at lunch because she just walked out of a less-than-complimentary performance review.

Despite having only two options to choose from, most people will make the wrong choice and default to dispositional attribution when attempting to explain the actions of others.

But why should this be so?

For one, humans are better able to reconcile someone else’s actions if they believe the person is bad in some way.

We also tend to default to dispositional attributes because it is easier than seeking out the real cause of someone’s behavior.

Avoiding fundamental attribution error entirely may be difficult, but here are a few ways we can at least reduce its impact:

Empathy and rationalization

While we can never be privy to the cause of all human behavior, we can at least default to empathy and take the stance that there is more to a person’s actions than meets the eye.

We may also rationalize their behavior by remembering how we acted in a similar situation and what caused us to do so.

Remain positive

It can also be helpful to remember that inherent to all people are good and bad traits and, even if someone’s actions are undesirable, they are not necessarily representative of their overall character.

Key takeaways

- Fundamental attribution error is a bias people display when judging the behavior of others. The tendency is to over-emphasize personal characteristics and under-emphasize environmental and situational explanations.

- Despite having only two options to choose from, most people will default to dispositional attribution. This is because we like to believe someone is bad and often, it is easier and more convenient than discovering the real cause.

- To avoid fundamental attribution errors, it is important to develop a mindset that is positive, empathic, and rational.

Connected Thinking Frameworks

Convergent vs. Divergent Thinking

Critical Thinking

Systems Thinking

Vertical Thinking

Maslow’s Hammer

Peter Principle

Straw Man Fallacy

Streisand Effect

Heuristic

Recognition Heuristic

Representativeness Heuristic

Take-The-Best Heuristic

Biases

Bundling Bias

Barnum Effect

First-Principles Thinking

Ladder Of Inference

Six Thinking Hats Model

Second-Order Thinking

Lateral Thinking

Bounded Rationality

Dunning-Kruger Effect

Occam’s Razor

Mandela Effect

Crowding-Out Effect

Bandwagon Effect

Read Next: Biases, Bounded Rationality, Mandela Effect, Dunning-Kruger

Read Next: Heuristics, Biases.

Main Free Guides:

- Business Models

- Business Competition

- Business Strategy

- Business Development

- Digital Business Models

- Distribution Channels

- Marketing Strategy

- Platform Business Models

- Revenue Models

- Tech Business Models

- Blockchain Business Models Framework