Что это за ошибки такие

Когнитивные искажения случаются, когда мы принимаем нерациональные решения, основываясь на инстинктах, чувствах или прошлом опыте.

Вообще, в нерациональных решениях нет ничего плохого, мы принимаем сотни таких решений каждый день — как бы «на автомате». Но порой они мешают, особенно если ошибку не удаётся распознать вовремя.

Типичный пример когнитивного искажения — это желание доделать начатое. Например, доесть в ресторане еду, которую уже принесли, — «чтобы не пропала». Или, к примеру, кто-то идёт в кино, даже если устал и не хочет: ведь билет уже куплен. Это типичное когнитивное искажение. Если в обоих случаях сесть и сказать себе: «Блин, зачем я это делаю?» — ошибки удастся избежать. И ладно если это кино, а часто люди годами доучиваются в нелюбимом вузе или месяцами изо всех сил пилят стартап просто потому, что привыкли и хотят «довести до конца».

С когнитивными искажениями борются с помощью методов рационального мышления. Сторонники таких методов стараются как можно чаще задавать себе вопросы, «тормозят» автоматические действия.

У «рационалистов» есть своя звезда — писатель и философ Элиезер Юдковский. Он написал несколько сотен постов в свой блог LessWrong — фанаты перевели самые важные на русский язык. А ещё он написал книгу «Гарри Поттер и методы рационального мышления» — в ней Юдковский «исправляет» нерациональные действия героев любимой книжки. Это весело и интересно, советуем почитать.

Ошибка планирования

Она же субъективная оценка сроков

Павлу предложили проект и попросили обозначить сроки выполнения. Он мысленно разбил задачу на этапы и прикинул, сколько времени потребуется на каждый из них. Сложил их вместе и пообещал сдать работу ровно через месяц. Но что-то пошло не так, и проект он сдал с двухнедельной задержкой.

Не поддавайтесь соблазну оценить задачу поэтапно и просуммировать оценки Есть риск получить слишком оптимистичный срок — без учёта неожиданных задержек и непредвиденных ситуаций. Так что только оценка целиком, только хардкор.

Комбо. Ошибка планирования работает в обе стороны. Если вы скажете, что выкатите модуль за 3–4 недели, то можете ошибиться с верхней оценкой — и задача займёт 5–6 недель. А собеседник услышит вас так: «Через три недели будет готово». Так случится к-к-комбо, которое может превратиться в фаталити: результат разойдётся с ожиданиями в два раза!

Совет. Не оценивайте сроки сразу. Коллеги понимают, что это важное дело и нужно всё взвесить. Можно победить когнитивную ошибку, всегда отвечая: «Я не могу дать быстрый ответ, вернусь с оценкой сроков позже». Главное — не забыть вернуться.

Эффект эгоцентричности

Михаил каждый день перерабатывает, хотя его коллеги заканчивают вовремя и по вечерам флудят в чате. Михаил уверен, что их проекты проще, они не потянут его задачи, и продолжает делать всё сам. На дейликах говорит, что дела супер. Через полгода он не выдерживает и увольняется.

Чтобы такого не допустить, помните, что вы субъективно оцениваете уровень сложности задач. Не стесняйтесь обсуждать подобные вопросы с коллегами. Вместе ищите способы оптимизировать работу.

Совет. Учиться делегированию полезно даже начинающему разработчику. Джун быстро становится сеньором, а желание всё тянуть на себе может стать фатальным для карьеры: выгорание никто не отменял.

Эвристика доступности

Команда выбирает, на какой платформе проводить ежедневные созвоны: Zoom, Discord или Google Meet. Последний вариант исключают сразу же, потому что каждый член команды хотя бы раз слышал о нём негативный отзыв. Большинство голосуют за Zoom: это «чуть ли не самый популярный сервис» для видеозвонков. Discord никто не пользовался, поэтому его даже обсуждать не стали.

Эвристика доступности — склонность оценивать частоту или вероятность чего-либо по тому, насколько легко вспоминаются примеры произошедшего. Главная ловушка здесь в том, что выборка получается маленькой. А это значительно упрощает процесс оценки и принятия решения для мозга.

Чтобы не дать себя обмануть, анализируйте, оценивайте, собирайте статистику.

Совет. Рационально выбирать помогают таблички. Сделайте этап составления табличек с решениями и их оценкой — плюсы, минусы, особенности — обязательным, чтобы не торопиться с выбором.

Эффект социальной желаемости

Алина — разработчица в команде, которая пилит важный для бизнеса KYC-модуль. Модуль почти готов, осталось только протестировать его перед продакшном. Алина — сторонница автоматизированного тестирования. Однако другие разработчики любят тестировать продукты вручную. Поэтому Алина решает не писать автотесты, чтобы команде было «приятно».

Обычно эффекты социальной желаемости ярко проявляются в коллективах и обществах, где не принято спорить, а своё мнение приходится держать при себе.

Яндекс — компания с другими принципами. Здесь любой сотрудник или сотрудница может сказать: «Ребята, слушайте, мне кажется, тут будет быстрее и эффективнее покрыть всё автотестами, а мы лучше займёмся интеграционкой и юнит-тестированием». Смело спрашивайте, предлагайте, спорьте, пробуйте: это приветствуют и этого ждут.

Проклятие знания

Когда считаешь неочевидные вещи очевидными

Василий давно в IT. Сейчас он тимлид, а под его крылом несколько менти, у которых заканчивается испытательный срок. Задача Василия — тщательно подготовить ребят к тестам. Он уверен, что все знают базу, поэтому сразу перешёл к сложному. Ребятам неловко задавать уточняющие вопросы. В итоге они заваливают тесты

Убедитесь, что вы с коллегами находитесь на одном уровне восприятия и используете одни и те же термины. Если же нет — постарайтесь проложить путь от простого к сложному. В ходе разговора опирайтесь на аргументы и понятия, которые уже были проговорены и приняты собеседниками. Как только цепочка разрывается, вас перестают понимать.

Совет. Такая когнитивная ошибка часто возникает во время обсуждения идей. Полезно спрашивать собеседников: «Коллеги, а я сейчас не слишком погружаюсь в технические детали?» Или: «Возможно, я говорю слишком общие вещи? Может, стоит добавить разговору хардовости, если мы все на одной волне?»

Мы уже рассказывали о механизмах когнитивных искажений — ошибок мышления, из-за которых мы видим мир не совсем таким, каким он является. Список типичных когнитивных ошибок огромен — «ловушек» десятки, но многие обманывают нас по одному и тому же принципу. Кроме того, каждый человек может быть более или менее склонен к искажениям определенного рода. Мы приведем несколько примеров распространенных когнитивных ошибок. Выберите три своих «любимых» искажения, а в конце вы узнаете, по какому принципу вас проводит собственный мозг.

- Предвзятость подтверждения. Допустим, вы уверены, что гомеопатия работает, и обращаете внимание только на аргументы, подтверждающие ее эффективность. Рассказывая о гомеопатии соседке, вы будете описывать случаи, когда метод помог, игнорируя те ситуации, когда толку не было.

- Вера в справедливый мир. Вы считаете, что мир в целом справедлив, каждый получает по заслугам, и хорошим поведением можно заслужить награду. Если кто-то пострадал, например, от насилия, значит, сам в чем-то виноват — недосмотрел или спровоцировал. С хорошими людьми, которые делают все правильно, плохие вещи не случаются.

- Кажущееся постоянство. Вы вспоминаете своего одноклассника, который стал владельцем бизнеса. Вы говорите, что он всегда был амбициозным и талантливым (хотя на самом деле он был троечником-прогульщиком).

- Ошибка выжившего. Вы рассказываете всем, что сами добились всего — поступили в хороший вуз, построили карьеру. Другие люди тоже могли бы так сделать, это несложно, надо было только попробовать! Вы не в курсе, что многие старались так же, как и вы, — но вам повезло, а у них не получилось.

- Фундаментальная ошибка атрибуции. Вы злитесь на то, что коллега постоянно опаздывает. За глаза вы называете ее ленивой и несобранной. В то же время себя вы считаете человеком пунктуальным. Конечно, вы тоже периодически опаздываете, но виной всему пробки, а не ваша несобранность.

- Иллюзия истины. Вас спрашивают, нужно ли пить антибиотики при простуде. Вы вспоминаете, что ваш друг говорил, как антибиотики помогли ему при гриппе. Вроде бы вы ничего не слышали о том, что антибиотики могут навредить при ОРВИ, поэтому вы уверены, что пить их нужно.

- Генерализация частных случаев. Вы знаете двух людей, которые болели депрессией, но смогли вылечиться без таблеток и психолога. Теперь вы говорите всем, что каждый может справиться с депрессией самостоятельно.

- Эффект Барнума. Вы прочитали описание своего типа по соционике — удивительно, как все совпадает! Теперь вы рассказываете всем новым знакомым, что вы — Дон Кихот, чтобы знали, как себя с вами вести.

- Иллюзия конца истории. Вы рассказываете, что ваше отношение к жизни и ценности менялись уже несколько раз. Но вы уверены, что сейчас вы уже окончательно сформировались как личность и в будущем не измените своих убеждений.

Robson#/flickr.com/CC BY 2.0

Что из этого больше всего похоже на вас?

Если вы выбрали пункты 1, 4 и 7, то ваши когнитивные ошибки связаны с обработкой информации. При предвзятости подтверждения человек замечает исключительно те факты, которые соответствуют его убеждениям.

Ошибка выжившего говорит о том, что вы видите только случаи успешного исхода, не зная, что многие в том же деле потерпели поражение, — ведь о проигравших никто не говорит. А при генерализации частных случаев человек склонен обобщать один-два-три известных ему примера на все возможные ситуации.

Зачастую искажения, связанные с обработкой информации, возникают просто потому, что у человека мало исходных данных. Чем больше вы будете знать, тем меньше будет ваша склонность совершать подобные когнитивные ошибки. При изучении информации важно сохранять критическое мышление. Помните, что человек консервативен — мозг будет пытаться все упростить и подсунуть вам факты, которые подтверждают вашу правоту.

Ваши «любимые» искажения — 2, 5 и 8? Значит, вы склонны к социальным когнитивным ошибкам. Чаще всего они связаны с ошибкой атрибуции — приписыванием определенных характеристик себе или другим. Фундаментальная ошибка атрибуции проявляется в том, что в поведении других вы обращаете больше внимания на их личность, недооценивая влияние внешних факторов. А когда думаете о собственном поведении, все наоборот: личность отходит на второй план, а ситуация становится определяющим фактором.

При вере в справедливый мир человек приписывает жертвам ужасных событий отрицательные черты, чтобы в своей голове как-то рационализировать произошедшее.

Посмотрите интересные факты о теле, которые вас удивят:

Эффект Барнума — это склонность видеть в очень размытых описаниях свои черты. Такой эффект часто проявляется при чтении гороскопов, толкований имен, соционических типов и так далее. Кажется, будто эти тексты написаны именно про вас — но на самом деле они настолько общие и размытые, что практически каждый человек может найти в них себя. Попробуйте прочитать гороскоп другого знака, думая, что это про вас, — вы наверняка и там найдете много своих черт.

Ошибки атрибуции появляются из-за эгоцентричности, предубеждений, нехватки информации о других людях. Чтобы избежать таких ошибок, стоит меньше опираться на стереотипы и уделять больше внимания конкретному человеку и ситуации. Люди разные, ситуации бывают разные, и чаще всего это не поддается простой классификации — как бы мозгу ни хотелось сделать мир «черно-белым».

Наконец, ошибки 3, 6 и 9 возникают из-за проблем с памятью. Иллюзия истины заставляет вас верить, что нечто является правдой, только потому, что вы это где-то уже слышали. А вы проверяли, что это правда? Из-за кажущегося постоянства человек склонен думать, что в прошлом другие люди и события были примерно такими же, как сейчас. Даже если все было совсем не так, вы будете подгонять воспоминание под текущий образ. Это работает и в отношении самих себя — например, когда взрослые люди говорят, что они никогда не были такими распущенными, как нынешние подростки (хотя они были именно такими).

Бриджет Райли, Current

Иллюзия конца истории — это когнитивная ошибка, из-за которой люди думают, что в прошлом сильно изменились, но в будущем останутся примерно такими же, как сейчас. Причем эта иллюзия проявляется в любом возрасте. На самом деле человек просто не помнит, что пять лет назад он тоже думал, что уже не поменяется, — а сейчас говорит всем, как вырос за эти пять лет.

Единственный способ бороться с такими ошибками — это почаще напрягать память. Откуда вы это знаете? Вы точно помните, что все было именно так? А если повспоминать получше?

Бороться с когнитивными искажениями можно, если вы хотите иметь более трезвый взгляд на мир. Впрочем, эти ошибки возникли именно для того, чтобы защитить ваш мозг от огромного количества информации, упростить непредсказуемую реальность, дать иллюзию контроля. Так что избавляться от когнитивных ошибок или оставить все как есть, — решать вам.

О других когнитивных искажениях читайте здесь.

Обнаружили ошибку? Выделите ее и нажмите Ctrl+Enter.

«Thinking errors» redirects here. For faulty reasoning, see Fallacy.

A cognitive distortion is an exaggerated or irrational thought pattern involved in the onset or perpetuation of psychopathological states, such as depression and anxiety.[1]

Cognitive distortions are thoughts that cause individuals to perceive reality inaccurately. According to Aaron Beck’s cognitive model, a negative outlook on reality, sometimes called negative schemas (or schemata), is a factor in symptoms of emotional dysfunction and poorer subjective well-being. Specifically, negative thinking patterns reinforce negative emotions and thoughts.[2] During difficult circumstances, these distorted thoughts can contribute to an overall negative outlook on the world and a depressive or anxious mental state. According to hopelessness theory and Beck’s theory, the meaning or interpretation that people give to their experience importantly influences whether they will become depressed and whether they will experience severe, repeated, or long-duration episodes of depression.[3]

Challenging and changing cognitive distortions is a key element of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

Definition[edit]

Cognitive comes from the Medieval Latin cognitīvus, equivalent to Latin cognit(us), ‘known’.[4] Distortion means the act of twisting or altering something out of its true, natural, or original state.[5]

History[edit]

In 1957, American psychologist Albert Ellis, though he did not know it yet, would aid cognitive therapy in correcting cognitive distortions and indirectly helping David D. Burns in writing The Feeling Good Handbook. Ellis created what he called the ABC Technique of rational beliefs. The ABC stands for the activating event, beliefs that are irrational, and the consequences that come from the belief. Ellis wanted to prove that the activating event is not what caused the emotional behavior or the consequences, but the beliefs and how the person irrationally perceive the events that aids the consequences.[6] With this model, Ellis attempted to use rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT) with his patients, in order to help them «reframe» or reinterpret the experience in a more rational manner. In this model Ellis explains it all for his clients, while Beck helps his clients figure this out on their own.[7] Beck first started to notice these automatic distorted thought processes when practicing psychoanalysis, while his patients followed the rule of saying anything that comes to mind. Aaron realized that his patients had irrational fears, thoughts, and perceptions that were automatic. Beck began noticing his automatic thought processes that he knew his patients had but did not report. Most of the time the thoughts were biased against themselves and very erroneous.[8]

Beck believed that the negative schemas developed and manifested themselves in the perspective and behavior. The distorted thought processes lead to focusing on degrading the self, amplifying minor external setbacks, experiencing other’s harmless comments as ill-intended, while simultaneously seeing self as inferior. Inevitably cognitions are reflected in their behavior with a reduced desire to care for oneself, to seek pleasure, and give up. These exaggerated perceptions, due to cognition, feel real and accurate because the schemas, after being reinforced through the behavior, tend to become automatic and do not allow time for reflection.[9] This cycle is also known as Beck’s cognitive triad, focused on the theory that the person’s negative schema applied to the self, the future, and the environment.[10]

In 1972, psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, and cognitive therapy scholar Aaron T. Beck published Depression: Causes and Treatment.[11] He was dissatisfied with the conventional Freudian treatment of depression, because there was no empirical evidence for the success of Freudian psychoanalysis. Beck’s book provided a comprehensive and empirically-supported theoretical model for depression—its potential causes, symptoms, and treatments. In Chapter 2, titled «Symptomatology of Depression», he described «cognitive manifestations» of depression, including low self-evaluation, negative expectations, self-blame and self-criticism, indecisiveness, and distortion of the body image.[11]

Beck’s student David D. Burns continued research on the topic. In his book Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy, Burns described personal and professional anecdotes related to cognitive distortions and their elimination.[12] When Burns published Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy, it made Beck’s approach to distorted thinking widely known and popularized.[13][14] Burns sold over four million copies of the book in the United States alone. It was a book commonly «prescribed» for patients who have cognitive distortions that have led to depression. Beck approved of the book, saying that it would help others alter their depressed moods by simplifying the extensive study and research that had taken place since shortly after Beck had started as a student and practitioner of psychoanalytic psychiatry. Nine years later, The Feeling Good Handbook was published, which was also built on Beck’s work and includes a list of ten specific cognitive distortions that will be discussed throughout this article.[15]

Main types[edit]

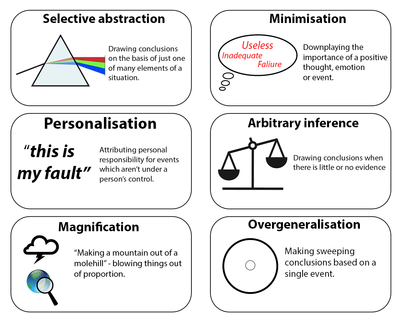

Examples of some common cognitive distortions seen in depressed and anxious individuals. People may be taught how to identify and alter these distortions as part of cognitive behavioural therapy.

John C. Gibbs and Granville Bud Potter propose four categories for cognitive distortions: self-centered, blaming others, minimizing-mislabeling, and assuming the worst.[16] The cognitive distortions listed below[15] are categories of automatic thinking, and are to be distinguished from logical fallacies.[17][18]

All-or-nothing thinking[edit]

The «all-or-nothing thinking distortion» is also referred to as «splitting»,[19] «black-and-white thinking»,[2] and «polarized thinking.»[20] Someone with the all-or-nothing thinking distortion looks at life in black and white categories.[15] Either they are a success or a failure; either they are good or bad; there is no in-between. According to one article, «Because there is always someone who is willing to criticize, this tends to collapse into a tendency for polarized people to view themselves as a total failure. Polarized thinkers have difficulty with the notion of being ‘good enough’ or a partial success.»[19]

- Example (from The Feeling Good Handbook): A woman eats a spoonful of ice cream. She thinks she is a complete failure for breaking her diet. She becomes so depressed that she ends up eating the whole quart of ice cream.[15]

This example captures the polarized nature of this distortion—the person believes they are totally inadequate if they fall short of perfection.

In order to combat this distortion, Burns suggests thinking of the world in terms of shades of gray.[15] Rather than viewing herself as a complete failure for eating a spoonful of ice cream, the woman in the example could still recognize her overall effort to diet as at least a partial success.

This distortion is commonly found in perfectionists.[13]

Jumping to conclusions[edit]

Reaching preliminary conclusions (usually negative) with little (if any) evidence. Three specific subtypes are identified:[citation needed]

Mind reading[edit]

Inferring a person’s possible or probable (usually negative) thoughts from their behavior and nonverbal communication; taking precautions against the worst suspected case without asking the person.

- Example 1: A student assumes that the readers of their paper have already made up their minds concerning its topic, and, therefore, writing the paper is a pointless exercise.[18]

- Example 2: Kevin assumes that because he sits alone at lunch, everyone else must think he is a loser. (This can encourage self-fulfilling prophecy; Kevin may not initiate social contact because of his fear that those around him already perceive him negatively).[21]

Fortune-telling[edit]

Predicting outcomes (usually negative) of events.

- Example: A depressed person tells themselves they will never improve; they will continue to be depressed for their whole life.[15]

One way to combat this distortion is to ask, «If this is true, does it say more about me or them?»[22]

Labeling[edit]

Labeling occurs when someone overgeneralizes characteristics of other people. For example, someone might use an unfavorable term to describe a complex person or event.

Emotional reasoning[edit]

In the emotional reasoning distortion, it is assumed that feelings expose the true nature of things and experience reality as a reflection of emotionally linked thoughts; something is believed true solely based on a feeling.

- Examples: «I feel stupid, therefore I must be stupid».[2] Feeling fear of flying in planes, and then concluding that planes must be a dangerous way to travel.[15] Feeling overwhelmed by the prospect of cleaning one’s house, therefore concluding that it’s hopeless to even start cleaning.[23]

Should/shouldn’t and must/mustn’t statements[edit]

Making «must» or «should» statements was included by Albert Ellis in his rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT), an early form of CBT; he termed it «musturbation». Michael C. Graham called it «expecting the world to be different than it is».[24] It can be seen as demanding particular achievements or behaviors regardless of the realistic circumstances of the situation.

- Example: After a performance, a concert pianist believes he or she should not have made so many mistakes.[23]

- In Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy, David Burns clearly distinguished between pathological «should statements», moral imperatives, and social norms.

A related cognitive distortion, also present in Ellis’ REBT, is a tendency to «awfulize»; to say a future scenario will be awful, rather than to realistically appraise the various negative and positive characteristics of that scenario.

According to Burns, «must» and «should» statements are negative because they cause the person to feel guilty and upset at themselves. Some people also direct this distortion at other people, which can cause feelings of anger and frustration when that other person does not do what they should have done. He also mentions how this type of thinking can lead to rebellious thoughts. In other words, trying to whip oneself into doing something with «shoulds» may cause one to desire just the opposite.[15]

Gratitude traps[edit]

A gratitude trap is a type of cognitive distortion that typically arises from misunderstandings regarding the nature or practice of gratitude.[citation needed] The term can refer to one of two related but distinct thought patterns:

- A self-oriented thought process involving feelings of guilt, shame, or frustration related to one’s expectations of how things «should» be.

- An «elusive ugliness in many relationships, a deceptive ‘kindness,’ the main purpose of which is to make others feel indebted», as defined by psychologist Ellen Kenner.[25]

Blaming others[edit]

Personalization and blaming[edit]

Personalization is assigning personal blame disproportionate to the level of control a person realistically has in a given situation.

- Example 1: A foster child assumes that he/she has not been adopted because he/she is not «loveable enough».

- Example 2: A child has bad grades. His/her mother believes it is because she is not a good enough parent.[15]

Blaming is the opposite of personalization. In the blaming distortion, the disproportionate level of blame is placed upon other people, rather than oneself.[15] In this way, the person avoids taking personal responsibility, making way for a «victim mentality».

- Example: Placing blame for marital problems entirely on one’s spouse.[15]

Always being right[edit]

In this cognitive distortion, being wrong is unthinkable. This distortion is characterized by actively trying to prove one’s actions or thoughts to be correct, and sometimes prioritizing self-interest over the feelings of another person.[2][unreliable source?] In this cognitive distortion, the facts that oneself has about their surroundings are always right while other people’s opinions and perspectives are wrongly seen.[26][unreliable source?]

Fallacy of change[edit]

Relying on social control to obtain cooperative actions from another person.[2] The underlying assumption of this thinking style is that one’s happiness depends on the actions of others. The fallacy of change also assumes that other people should change to suit one’s own interests automatically and/or that it is fair to pressure them to change. It may be present in most abusive relationships in which partners’ «visions» of each other are tied into the belief that happiness, love, trust, and perfection would just occur once they or the other person change aspects of their beings.[27]

Minimizing-mislabeling[edit]

Magnification and minimization[edit]

Giving proportionally greater weight to a perceived failure, weakness or threat, or lesser weight to a perceived success, strength or opportunity, so that the weight differs from that assigned by others, such as «making a mountain out of a molehill». In depressed clients, often the positive characteristics of other people are exaggerated and their negative characteristics are understated.

- Catastrophizing – Giving greater weight to the worst possible outcome, however unlikely, or experiencing a situation as unbearable or impossible when it is just uncomfortable.

Labeling and mislabeling[edit]

A form of overgeneralization; attributing a person’s actions to their character instead of to an attribute. Rather than assuming the behaviour to be accidental or otherwise extrinsic, one assigns a label to someone or something that is based on the inferred character of that person or thing.

Assuming the worst[edit]

Overgeneralizing[edit]

Someone who overgeneralizes makes faulty generalizations from insufficient evidence. Such as seeing a «single negative event» as a «never-ending pattern of defeat»,[15] and as such drawing a very broad conclusion from a single incident or a single piece of evidence. Even if something bad happens only once, it is expected to happen over and over again.[2]

- Example 1: A young woman is asked out on a first date, but not a second one. She is distraught as she tells her friend, «This always happens to me! I’ll never find love!»

- Example 2: A woman is lonely and often spends most of her time at home. Her friends sometimes ask her to dinner and to meet new people. She feels it is useless to even try. No one really could like her. And anyway, all people are the same; petty and selfish.[23]

One suggestion to combat this distortion is to «examine the evidence» by performing an accurate analysis of one’s situation. This aids in avoiding exaggerating one’s circumstances.[15]

Disqualifying the positive[edit]

Disqualifying the positive refers to rejecting positive experiences by insisting they «don’t count» for some reason or other. Negative belief is maintained despite contradiction by everyday experiences. Disqualifying the positive may be the most common fallacy in the cognitive distortion range; it is often analyzed with «always being right», a type of distortion where a person is in an all-or-nothing self-judgment. People in this situation show signs of depression. Examples include:

- «I will never be as good as Jane»

- «Anyone could have done as well»[15]

- «They are just congratulating me to be nice»[28]

Mental filtering[edit]

Filtering distortions occur when an individual dwells only on the negative details of a situation and filters out the positive aspects.[15]

- Example: Andy gets mostly compliments and positive feedback about a presentation he has done at work, but he also has received a small piece of criticism. For several days following his presentation, Andy dwells on this one negative reaction, forgetting all of the positive reactions that he had also been given.[15]

The Feeling Good Handbook notes that filtering is like a «drop of ink that discolors a beaker of water».[15] One suggestion to combat filtering is a cost–benefit analysis. A person with this distortion may find it helpful to sit down and assess whether filtering out the positive and focusing on the negative is helping or hurting them in the long run.[15]

Conceptualization[edit]

In a series of publications,[29][30][31] philosopher Paul Franceschi has proposed a unified conceptual framework for cognitive distortions designed to clarify their relationships and define new ones. This conceptual framework is based on three notions: (i) the reference class (a set of phenomena or objects, e.g. events in the patient’s life); (ii) dualities (positive/negative, qualitative/quantitative, …); (iii) the taxon system (degrees allowing to attribute properties according to a given duality to the elements of a reference class). In this model, «dichotomous reasoning», «minimization», «maximization» and «arbitrary focus» constitute general cognitive distortions (applying to any duality), whereas «disqualification of the positive» and «catastrophism» are specific cognitive distortions, applying to the positive/negative duality. This conceptual framework posits two additional cognitive distortion classifications: the «omission of the neutral» and the «requalification in the other pole».

Cognitive restructuring[edit]

Cognitive restructuring (CR) is a popular form of therapy used to identify and reject maladaptive cognitive distortions,[32] and is typically used with individuals diagnosed with depression.[33] In CR, the therapist and client first examine a stressful event or situation reported by the client. For example, a depressed male college student who experiences difficulty in dating might believe that his «worthlessness» causes women to reject him. Together, therapist and client might then create a more realistic cognition, e.g., «It is within my control to ask girls on dates. However, even though there are some things I can do to influence their decisions, whether or not they say yes is largely out of my control. Thus, I am not responsible if they decline my invitation.» CR therapies are designed to eliminate «automatic thoughts» that include clients’ dysfunctional or negative views. According to Beck, doing so reduces feelings of worthlessness, anxiety, and anhedonia that are symptomatic of several forms of mental illness.[34] CR is the main component of Beck’s and Burns’s CBT.[35]

Narcissistic defense[edit]

Those diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder tend, unrealistically, to view themselves as superior, overemphasizing their strengths and understating their weaknesses.[34] Narcissists use exaggeration and minimization this way to shield themselves against psychological pain.[36][37]

Decatastrophizing[edit]

In cognitive therapy, decatastrophizing or decatastrophization is a cognitive restructuring technique that may be used to treat cognitive distortions, such as magnification and catastrophizing,[38] commonly seen in psychological disorders like anxiety[33] and psychosis.[39] Major features of these disorders are the subjective report of being overwhelmed by life circumstances and the incapability of affecting them.

The goal of CR is to help the client change their perceptions to render the felt experience as less significant.

Criticism[edit]

Common criticisms of the diagnosis of cognitive distortion relate to epistemology and the theoretical basis. If the perceptions of the patient differ from those of the therapist, it may not be because of intellectual malfunctions but because the patient has different experiences. In some cases, depressed subjects appear to be «sadder but wiser».[40]

See also[edit]

- Cognitive bias – Systematic pattern of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment

- Cognitive dissonance – Stress from contradictory beliefs

- Defence mechanism – Unconscious psychological mechanism that reduces anxiety arising from negative stimuli

- Delusion – Firm and fixed belief in that which is based on inadequate grounding

- Destabilisation – Attempts to undermine political, military or economic power

- Emotion and memory – Critical factors contributing to the emotional enhancement effect on human memory

- Illusion – Distortion of the perception of reality

- Language and thought – The study of how language influences thought

- List of cognitive biases – Systematic patterns of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment

- List of fallacies – Reasoning that are logically incorrect or unsound

- Negativity bias – Tendency to give more importance to negative experiences

- Parataxic distortion – Inclination to skew perceptions of others based on fantasy

- Rationalization (psychology) – Psychological defense mechanism

References[edit]

- ^ Helmond, Petra; Overbeek, Geertjan; Brugman, Daniel; Gibbs, John C. (2015). «A Meta-Analysis on Cognitive Distortions and Externalizing Problem Behavior» (PDF). Criminal Justice and Behavior. 42 (3): 245–262. doi:10.1177/0093854814552842. S2CID 146611029.

- ^ a b c d e f Grohol, John (2009). «15 Common Cognitive Distortions». PsychCentral. Archived from the original on 2009-07-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ «APA PsycNet». psycnet.apa.org. Retrieved 2020-06-29.

- ^ «Cognitive». Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d. Retrieved 2020-03-14.

- ^ «Distortion». Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2020-03-14.

- ^ McLeod, Saul A. (2015). «Cognitive Behavioral Therapy». SimplyPsychology.

- ^ Ellis, Albert (1957). «Rational Psychotherapy and Individual Psychology». Journal of Individual Psychology. 13: 42.

- ^ Beck, Aaron T. (1997). «The Past and Future of Cognitive Therapy». Journal of Psychotherapy and Research. 6 (4): 277. PMC 3330473. PMID 9292441.

- ^ Kovacs, Maria; Beck, Aaron T. (1986). «Maladaptive Cognitive Structure in Depression». The American Journal of Psychiatry: 526.

- ^ Beck, Aaron T. (1967). Depression Causes and Treatment. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 166.

- ^ a b Beck, Aaron T. (1972). Depression; Causes and Treatment. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-7652-7.

- ^ Burns, David D. (1980). Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy.

- ^ a b Burns, David D. (1980). Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy. New York: Morrow. ISBN 978-0-688-03633-1.

- ^ Roberts, Joe. «History of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy». National Association of Cognitive Behavioral Therapists Online Headquarters. National Association of Cognitive Behavioral Therapists. Archived from the original on 2016-05-06. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Burns, David D. (1980). The Feeling Good Handbook: Using the New Mood Therapy in Everyday Life. New York: W. Morrow. ISBN 978-0-688-01745-3.

- ^ Barriga, Alvaro Q.; Morrison, Elizabeth M.; Liau, Albert K.; Gibbs, John C. (2001). «Moral Cognition: Explaining the Gender Difference in Antisocial Behavior». Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 47 (4): 532–562. doi:10.1353/mpq.2001.0020. JSTOR 23093698. S2CID 145630809. Retrieved 2022-02-07.

Gibbs and Potter’s…four-category typology: 1. Self-Centered…2. Blaming Others…3. Minimizing-Mislabeling…[and] 4. Assuming the Worst[.]

- ^ Maas, David F. (1997). «General Semantics Formulations in David Burns’ Feeling Good». ETC: A Review of General Semantics. 54 (2): 225–234. JSTOR 42579774. Retrieved 2022-02-07.

1. All-or-Nothing Thinking … 2. Overgeneralization … 3. Mental Filter, or Selective Abstraction … 4. Reverse Alchemy or Disqualifying the Positive … 5. Mind-Reading … 6. Mind-Reading as Fortune Telling … 7. Magnification or Minimization … 8. Emotional Reasoning … 9. Should/Shouldn’t Statements…Dr. Albert Ellis (1994) has labeled this…as Must-urbation … 10. Labeling … 11. Personalization and Blame[.]

- ^ a b Tagg, John (1996). «Cognitive Distortions». Archived from the original on November 1, 2011. Retrieved October 24, 2011.

- ^ a b «Cognitive Distortions Affecting Stress». MentalHelp.net. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ Grohol, John M. (17 May 2016). «15 Common Cognitive Distortions». PsychCentral. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ «Cognitive Distortions: Jumping to Conclusions & All or Nothing Thinking». Moodfit. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ «Common Cognitive Distortions: Mind Reading». Cognitive Behavioral Therapy — Los Angeles. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Schimelpfening, Nancy. «You Are What You Think».

- ^ Graham, Michael C. (2014). Facts of Life: ten issues of contentment. Outskirts Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-4787-2259-5.

- ^ «How to Savor Gratitude and Disarm «Gratitude Traps»«. The Objective Standard. 2020-05-20. Retrieved 2021-02-11.

- ^ «15 Common Cognitive Distortions». PsychCentral. 2016-05-17. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- ^ «Fallacy of Change: 15 types of distorted thinking that lead to massive anxiety 10/15». Abate Counseling. 2018-08-30.

- ^ «Disqualifying the Positive». Palomar. Retrieved 2020-01-03.

- ^ Franceschi, Paul (2007). «Compléments pour une théorie des distorsions cognitives». Journal de Thérapie Comportementale et Cognitive. 17 (2): 84–88. doi:10.1016/s1155-1704(07)89710-2.

- ^ Franceschi, Paul (2009). «Théorie des distorsions cognitives : la sur-généralisation et l’étiquetage». Journal de Thérapie Comportementale et Cognitive. 19 (4): 136–140. doi:10.1016/j.jtcc.2009.10.003.

- ^ Franceschi, Paul (2010). «Théorie des distorsions cognitives : la personnalisation». Journal de Thérapie Comportementale et Cognitive. 20 (2): 51–55. doi:10.1016/j.jtcc.2010.06.006.

- ^ Gil, Pedro J. Moreno; Carrillo, Francisco Xavier Méndez; Meca, Julio Sánchez (2001). «Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural treatment in social phobia: A meta-analytic review». Psychology in Spain. 5: 17–25. S2CID 8860010.

- ^ a b Martin, Ryan C.; Dahlen, Eric R. (2005). «Cognitive emotion regulation in the prediction of depression, anxiety, stress, and anger». Personality and Individual Differences. 39 (7): 1249–1260. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.06.004.

- ^ a b Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association., American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Task Force. (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. 2013. ISBN 9780890425541. OCLC 830807378.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Rush, A.; Khatami, M.; Beck, A. (1975). «Cognitive and Behavior Therapy in Chronic Depression». Behavior Therapy. 6 (3): 398–404. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(75)80116-X.

- ^ Millon, Theodore; Carrie M. Millon; Seth Grossman; Sarah Meagher; Rowena Ramnath (2004). Personality Disorders in Modern Life. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-23734-1.

- ^ Thomas, David (2010). Narcissism: Behind the Mask. ISBN 978-1-84624-506-0.

- ^ Theunissen, Maurice; Peters, Madelon L.; Bruce, Julie; Gramke, Hans-Fritz; Marcus, Marco A. (2012). «Preoperative Anxiety and Catastrophizing» (PDF). The Clinical Journal of Pain. 28 (9): 819–841. doi:10.1097/ajp.0b013e31824549d6. PMID 22760489. S2CID 12414206.

- ^ Moritz, Steffen; Schilling, Lisa; Wingenfeld, Katja; Köther, Ulf; Wittekind, Charlotte; Terfehr, Kirsten; Spitzer, Carsten (2011). «Persecutory delusions and catastrophic worry in psychosis: Developing the understanding of delusion distress and persistence». Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 42 (September 2011): 349–354. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.02.003. PMID 21411041.

- ^ Beidel, Deborah C. (1986). «A Critique of the Theoretical Bases of Cognitive Behavioral Theories and Therapy». Clinical Psychology Review. 6 (2): 177–97. doi:10.1016/0272-7358(86)90011-5.

«Thinking errors» redirects here. For faulty reasoning, see Fallacy.

A cognitive distortion is an exaggerated or irrational thought pattern involved in the onset or perpetuation of psychopathological states, such as depression and anxiety.[1]

Cognitive distortions are thoughts that cause individuals to perceive reality inaccurately. According to Aaron Beck’s cognitive model, a negative outlook on reality, sometimes called negative schemas (or schemata), is a factor in symptoms of emotional dysfunction and poorer subjective well-being. Specifically, negative thinking patterns reinforce negative emotions and thoughts.[2] During difficult circumstances, these distorted thoughts can contribute to an overall negative outlook on the world and a depressive or anxious mental state. According to hopelessness theory and Beck’s theory, the meaning or interpretation that people give to their experience importantly influences whether they will become depressed and whether they will experience severe, repeated, or long-duration episodes of depression.[3]

Challenging and changing cognitive distortions is a key element of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

Definition[edit]

Cognitive comes from the Medieval Latin cognitīvus, equivalent to Latin cognit(us), ‘known’.[4] Distortion means the act of twisting or altering something out of its true, natural, or original state.[5]

History[edit]

In 1957, American psychologist Albert Ellis, though he did not know it yet, would aid cognitive therapy in correcting cognitive distortions and indirectly helping David D. Burns in writing The Feeling Good Handbook. Ellis created what he called the ABC Technique of rational beliefs. The ABC stands for the activating event, beliefs that are irrational, and the consequences that come from the belief. Ellis wanted to prove that the activating event is not what caused the emotional behavior or the consequences, but the beliefs and how the person irrationally perceive the events that aids the consequences.[6] With this model, Ellis attempted to use rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT) with his patients, in order to help them «reframe» or reinterpret the experience in a more rational manner. In this model Ellis explains it all for his clients, while Beck helps his clients figure this out on their own.[7] Beck first started to notice these automatic distorted thought processes when practicing psychoanalysis, while his patients followed the rule of saying anything that comes to mind. Aaron realized that his patients had irrational fears, thoughts, and perceptions that were automatic. Beck began noticing his automatic thought processes that he knew his patients had but did not report. Most of the time the thoughts were biased against themselves and very erroneous.[8]

Beck believed that the negative schemas developed and manifested themselves in the perspective and behavior. The distorted thought processes lead to focusing on degrading the self, amplifying minor external setbacks, experiencing other’s harmless comments as ill-intended, while simultaneously seeing self as inferior. Inevitably cognitions are reflected in their behavior with a reduced desire to care for oneself, to seek pleasure, and give up. These exaggerated perceptions, due to cognition, feel real and accurate because the schemas, after being reinforced through the behavior, tend to become automatic and do not allow time for reflection.[9] This cycle is also known as Beck’s cognitive triad, focused on the theory that the person’s negative schema applied to the self, the future, and the environment.[10]

In 1972, psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, and cognitive therapy scholar Aaron T. Beck published Depression: Causes and Treatment.[11] He was dissatisfied with the conventional Freudian treatment of depression, because there was no empirical evidence for the success of Freudian psychoanalysis. Beck’s book provided a comprehensive and empirically-supported theoretical model for depression—its potential causes, symptoms, and treatments. In Chapter 2, titled «Symptomatology of Depression», he described «cognitive manifestations» of depression, including low self-evaluation, negative expectations, self-blame and self-criticism, indecisiveness, and distortion of the body image.[11]

Beck’s student David D. Burns continued research on the topic. In his book Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy, Burns described personal and professional anecdotes related to cognitive distortions and their elimination.[12] When Burns published Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy, it made Beck’s approach to distorted thinking widely known and popularized.[13][14] Burns sold over four million copies of the book in the United States alone. It was a book commonly «prescribed» for patients who have cognitive distortions that have led to depression. Beck approved of the book, saying that it would help others alter their depressed moods by simplifying the extensive study and research that had taken place since shortly after Beck had started as a student and practitioner of psychoanalytic psychiatry. Nine years later, The Feeling Good Handbook was published, which was also built on Beck’s work and includes a list of ten specific cognitive distortions that will be discussed throughout this article.[15]

Main types[edit]

Examples of some common cognitive distortions seen in depressed and anxious individuals. People may be taught how to identify and alter these distortions as part of cognitive behavioural therapy.

John C. Gibbs and Granville Bud Potter propose four categories for cognitive distortions: self-centered, blaming others, minimizing-mislabeling, and assuming the worst.[16] The cognitive distortions listed below[15] are categories of automatic thinking, and are to be distinguished from logical fallacies.[17][18]

All-or-nothing thinking[edit]

The «all-or-nothing thinking distortion» is also referred to as «splitting»,[19] «black-and-white thinking»,[2] and «polarized thinking.»[20] Someone with the all-or-nothing thinking distortion looks at life in black and white categories.[15] Either they are a success or a failure; either they are good or bad; there is no in-between. According to one article, «Because there is always someone who is willing to criticize, this tends to collapse into a tendency for polarized people to view themselves as a total failure. Polarized thinkers have difficulty with the notion of being ‘good enough’ or a partial success.»[19]

- Example (from The Feeling Good Handbook): A woman eats a spoonful of ice cream. She thinks she is a complete failure for breaking her diet. She becomes so depressed that she ends up eating the whole quart of ice cream.[15]

This example captures the polarized nature of this distortion—the person believes they are totally inadequate if they fall short of perfection.

In order to combat this distortion, Burns suggests thinking of the world in terms of shades of gray.[15] Rather than viewing herself as a complete failure for eating a spoonful of ice cream, the woman in the example could still recognize her overall effort to diet as at least a partial success.

This distortion is commonly found in perfectionists.[13]

Jumping to conclusions[edit]

Reaching preliminary conclusions (usually negative) with little (if any) evidence. Three specific subtypes are identified:[citation needed]

Mind reading[edit]

Inferring a person’s possible or probable (usually negative) thoughts from their behavior and nonverbal communication; taking precautions against the worst suspected case without asking the person.

- Example 1: A student assumes that the readers of their paper have already made up their minds concerning its topic, and, therefore, writing the paper is a pointless exercise.[18]

- Example 2: Kevin assumes that because he sits alone at lunch, everyone else must think he is a loser. (This can encourage self-fulfilling prophecy; Kevin may not initiate social contact because of his fear that those around him already perceive him negatively).[21]

Fortune-telling[edit]

Predicting outcomes (usually negative) of events.

- Example: A depressed person tells themselves they will never improve; they will continue to be depressed for their whole life.[15]

One way to combat this distortion is to ask, «If this is true, does it say more about me or them?»[22]

Labeling[edit]

Labeling occurs when someone overgeneralizes characteristics of other people. For example, someone might use an unfavorable term to describe a complex person or event.

Emotional reasoning[edit]

In the emotional reasoning distortion, it is assumed that feelings expose the true nature of things and experience reality as a reflection of emotionally linked thoughts; something is believed true solely based on a feeling.

- Examples: «I feel stupid, therefore I must be stupid».[2] Feeling fear of flying in planes, and then concluding that planes must be a dangerous way to travel.[15] Feeling overwhelmed by the prospect of cleaning one’s house, therefore concluding that it’s hopeless to even start cleaning.[23]

Should/shouldn’t and must/mustn’t statements[edit]

Making «must» or «should» statements was included by Albert Ellis in his rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT), an early form of CBT; he termed it «musturbation». Michael C. Graham called it «expecting the world to be different than it is».[24] It can be seen as demanding particular achievements or behaviors regardless of the realistic circumstances of the situation.

- Example: After a performance, a concert pianist believes he or she should not have made so many mistakes.[23]

- In Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy, David Burns clearly distinguished between pathological «should statements», moral imperatives, and social norms.

A related cognitive distortion, also present in Ellis’ REBT, is a tendency to «awfulize»; to say a future scenario will be awful, rather than to realistically appraise the various negative and positive characteristics of that scenario.

According to Burns, «must» and «should» statements are negative because they cause the person to feel guilty and upset at themselves. Some people also direct this distortion at other people, which can cause feelings of anger and frustration when that other person does not do what they should have done. He also mentions how this type of thinking can lead to rebellious thoughts. In other words, trying to whip oneself into doing something with «shoulds» may cause one to desire just the opposite.[15]

Gratitude traps[edit]

A gratitude trap is a type of cognitive distortion that typically arises from misunderstandings regarding the nature or practice of gratitude.[citation needed] The term can refer to one of two related but distinct thought patterns:

- A self-oriented thought process involving feelings of guilt, shame, or frustration related to one’s expectations of how things «should» be.

- An «elusive ugliness in many relationships, a deceptive ‘kindness,’ the main purpose of which is to make others feel indebted», as defined by psychologist Ellen Kenner.[25]

Blaming others[edit]

Personalization and blaming[edit]

Personalization is assigning personal blame disproportionate to the level of control a person realistically has in a given situation.

- Example 1: A foster child assumes that he/she has not been adopted because he/she is not «loveable enough».

- Example 2: A child has bad grades. His/her mother believes it is because she is not a good enough parent.[15]

Blaming is the opposite of personalization. In the blaming distortion, the disproportionate level of blame is placed upon other people, rather than oneself.[15] In this way, the person avoids taking personal responsibility, making way for a «victim mentality».

- Example: Placing blame for marital problems entirely on one’s spouse.[15]

Always being right[edit]

In this cognitive distortion, being wrong is unthinkable. This distortion is characterized by actively trying to prove one’s actions or thoughts to be correct, and sometimes prioritizing self-interest over the feelings of another person.[2][unreliable source?] In this cognitive distortion, the facts that oneself has about their surroundings are always right while other people’s opinions and perspectives are wrongly seen.[26][unreliable source?]

Fallacy of change[edit]

Relying on social control to obtain cooperative actions from another person.[2] The underlying assumption of this thinking style is that one’s happiness depends on the actions of others. The fallacy of change also assumes that other people should change to suit one’s own interests automatically and/or that it is fair to pressure them to change. It may be present in most abusive relationships in which partners’ «visions» of each other are tied into the belief that happiness, love, trust, and perfection would just occur once they or the other person change aspects of their beings.[27]

Minimizing-mislabeling[edit]

Magnification and minimization[edit]

Giving proportionally greater weight to a perceived failure, weakness or threat, or lesser weight to a perceived success, strength or opportunity, so that the weight differs from that assigned by others, such as «making a mountain out of a molehill». In depressed clients, often the positive characteristics of other people are exaggerated and their negative characteristics are understated.

- Catastrophizing – Giving greater weight to the worst possible outcome, however unlikely, or experiencing a situation as unbearable or impossible when it is just uncomfortable.

Labeling and mislabeling[edit]

A form of overgeneralization; attributing a person’s actions to their character instead of to an attribute. Rather than assuming the behaviour to be accidental or otherwise extrinsic, one assigns a label to someone or something that is based on the inferred character of that person or thing.

Assuming the worst[edit]

Overgeneralizing[edit]

Someone who overgeneralizes makes faulty generalizations from insufficient evidence. Such as seeing a «single negative event» as a «never-ending pattern of defeat»,[15] and as such drawing a very broad conclusion from a single incident or a single piece of evidence. Even if something bad happens only once, it is expected to happen over and over again.[2]

- Example 1: A young woman is asked out on a first date, but not a second one. She is distraught as she tells her friend, «This always happens to me! I’ll never find love!»

- Example 2: A woman is lonely and often spends most of her time at home. Her friends sometimes ask her to dinner and to meet new people. She feels it is useless to even try. No one really could like her. And anyway, all people are the same; petty and selfish.[23]

One suggestion to combat this distortion is to «examine the evidence» by performing an accurate analysis of one’s situation. This aids in avoiding exaggerating one’s circumstances.[15]

Disqualifying the positive[edit]

Disqualifying the positive refers to rejecting positive experiences by insisting they «don’t count» for some reason or other. Negative belief is maintained despite contradiction by everyday experiences. Disqualifying the positive may be the most common fallacy in the cognitive distortion range; it is often analyzed with «always being right», a type of distortion where a person is in an all-or-nothing self-judgment. People in this situation show signs of depression. Examples include:

- «I will never be as good as Jane»

- «Anyone could have done as well»[15]

- «They are just congratulating me to be nice»[28]

Mental filtering[edit]

Filtering distortions occur when an individual dwells only on the negative details of a situation and filters out the positive aspects.[15]

- Example: Andy gets mostly compliments and positive feedback about a presentation he has done at work, but he also has received a small piece of criticism. For several days following his presentation, Andy dwells on this one negative reaction, forgetting all of the positive reactions that he had also been given.[15]

The Feeling Good Handbook notes that filtering is like a «drop of ink that discolors a beaker of water».[15] One suggestion to combat filtering is a cost–benefit analysis. A person with this distortion may find it helpful to sit down and assess whether filtering out the positive and focusing on the negative is helping or hurting them in the long run.[15]

Conceptualization[edit]

In a series of publications,[29][30][31] philosopher Paul Franceschi has proposed a unified conceptual framework for cognitive distortions designed to clarify their relationships and define new ones. This conceptual framework is based on three notions: (i) the reference class (a set of phenomena or objects, e.g. events in the patient’s life); (ii) dualities (positive/negative, qualitative/quantitative, …); (iii) the taxon system (degrees allowing to attribute properties according to a given duality to the elements of a reference class). In this model, «dichotomous reasoning», «minimization», «maximization» and «arbitrary focus» constitute general cognitive distortions (applying to any duality), whereas «disqualification of the positive» and «catastrophism» are specific cognitive distortions, applying to the positive/negative duality. This conceptual framework posits two additional cognitive distortion classifications: the «omission of the neutral» and the «requalification in the other pole».

Cognitive restructuring[edit]

Cognitive restructuring (CR) is a popular form of therapy used to identify and reject maladaptive cognitive distortions,[32] and is typically used with individuals diagnosed with depression.[33] In CR, the therapist and client first examine a stressful event or situation reported by the client. For example, a depressed male college student who experiences difficulty in dating might believe that his «worthlessness» causes women to reject him. Together, therapist and client might then create a more realistic cognition, e.g., «It is within my control to ask girls on dates. However, even though there are some things I can do to influence their decisions, whether or not they say yes is largely out of my control. Thus, I am not responsible if they decline my invitation.» CR therapies are designed to eliminate «automatic thoughts» that include clients’ dysfunctional or negative views. According to Beck, doing so reduces feelings of worthlessness, anxiety, and anhedonia that are symptomatic of several forms of mental illness.[34] CR is the main component of Beck’s and Burns’s CBT.[35]

Narcissistic defense[edit]

Those diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder tend, unrealistically, to view themselves as superior, overemphasizing their strengths and understating their weaknesses.[34] Narcissists use exaggeration and minimization this way to shield themselves against psychological pain.[36][37]

Decatastrophizing[edit]

In cognitive therapy, decatastrophizing or decatastrophization is a cognitive restructuring technique that may be used to treat cognitive distortions, such as magnification and catastrophizing,[38] commonly seen in psychological disorders like anxiety[33] and psychosis.[39] Major features of these disorders are the subjective report of being overwhelmed by life circumstances and the incapability of affecting them.

The goal of CR is to help the client change their perceptions to render the felt experience as less significant.

Criticism[edit]

Common criticisms of the diagnosis of cognitive distortion relate to epistemology and the theoretical basis. If the perceptions of the patient differ from those of the therapist, it may not be because of intellectual malfunctions but because the patient has different experiences. In some cases, depressed subjects appear to be «sadder but wiser».[40]

See also[edit]

- Cognitive bias – Systematic pattern of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment

- Cognitive dissonance – Stress from contradictory beliefs

- Defence mechanism – Unconscious psychological mechanism that reduces anxiety arising from negative stimuli

- Delusion – Firm and fixed belief in that which is based on inadequate grounding

- Destabilisation – Attempts to undermine political, military or economic power

- Emotion and memory – Critical factors contributing to the emotional enhancement effect on human memory

- Illusion – Distortion of the perception of reality

- Language and thought – The study of how language influences thought

- List of cognitive biases – Systematic patterns of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment

- List of fallacies – Reasoning that are logically incorrect or unsound

- Negativity bias – Tendency to give more importance to negative experiences

- Parataxic distortion – Inclination to skew perceptions of others based on fantasy

- Rationalization (psychology) – Psychological defense mechanism

References[edit]

- ^ Helmond, Petra; Overbeek, Geertjan; Brugman, Daniel; Gibbs, John C. (2015). «A Meta-Analysis on Cognitive Distortions and Externalizing Problem Behavior» (PDF). Criminal Justice and Behavior. 42 (3): 245–262. doi:10.1177/0093854814552842. S2CID 146611029.

- ^ a b c d e f Grohol, John (2009). «15 Common Cognitive Distortions». PsychCentral. Archived from the original on 2009-07-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ «APA PsycNet». psycnet.apa.org. Retrieved 2020-06-29.

- ^ «Cognitive». Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d. Retrieved 2020-03-14.

- ^ «Distortion». Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2020-03-14.

- ^ McLeod, Saul A. (2015). «Cognitive Behavioral Therapy». SimplyPsychology.

- ^ Ellis, Albert (1957). «Rational Psychotherapy and Individual Psychology». Journal of Individual Psychology. 13: 42.

- ^ Beck, Aaron T. (1997). «The Past and Future of Cognitive Therapy». Journal of Psychotherapy and Research. 6 (4): 277. PMC 3330473. PMID 9292441.

- ^ Kovacs, Maria; Beck, Aaron T. (1986). «Maladaptive Cognitive Structure in Depression». The American Journal of Psychiatry: 526.

- ^ Beck, Aaron T. (1967). Depression Causes and Treatment. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 166.

- ^ a b Beck, Aaron T. (1972). Depression; Causes and Treatment. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-7652-7.

- ^ Burns, David D. (1980). Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy.

- ^ a b Burns, David D. (1980). Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy. New York: Morrow. ISBN 978-0-688-03633-1.

- ^ Roberts, Joe. «History of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy». National Association of Cognitive Behavioral Therapists Online Headquarters. National Association of Cognitive Behavioral Therapists. Archived from the original on 2016-05-06. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Burns, David D. (1980). The Feeling Good Handbook: Using the New Mood Therapy in Everyday Life. New York: W. Morrow. ISBN 978-0-688-01745-3.

- ^ Barriga, Alvaro Q.; Morrison, Elizabeth M.; Liau, Albert K.; Gibbs, John C. (2001). «Moral Cognition: Explaining the Gender Difference in Antisocial Behavior». Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 47 (4): 532–562. doi:10.1353/mpq.2001.0020. JSTOR 23093698. S2CID 145630809. Retrieved 2022-02-07.

Gibbs and Potter’s…four-category typology: 1. Self-Centered…2. Blaming Others…3. Minimizing-Mislabeling…[and] 4. Assuming the Worst[.]

- ^ Maas, David F. (1997). «General Semantics Formulations in David Burns’ Feeling Good». ETC: A Review of General Semantics. 54 (2): 225–234. JSTOR 42579774. Retrieved 2022-02-07.

1. All-or-Nothing Thinking … 2. Overgeneralization … 3. Mental Filter, or Selective Abstraction … 4. Reverse Alchemy or Disqualifying the Positive … 5. Mind-Reading … 6. Mind-Reading as Fortune Telling … 7. Magnification or Minimization … 8. Emotional Reasoning … 9. Should/Shouldn’t Statements…Dr. Albert Ellis (1994) has labeled this…as Must-urbation … 10. Labeling … 11. Personalization and Blame[.]

- ^ a b Tagg, John (1996). «Cognitive Distortions». Archived from the original on November 1, 2011. Retrieved October 24, 2011.

- ^ a b «Cognitive Distortions Affecting Stress». MentalHelp.net. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ Grohol, John M. (17 May 2016). «15 Common Cognitive Distortions». PsychCentral. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ «Cognitive Distortions: Jumping to Conclusions & All or Nothing Thinking». Moodfit. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ «Common Cognitive Distortions: Mind Reading». Cognitive Behavioral Therapy — Los Angeles. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Schimelpfening, Nancy. «You Are What You Think».

- ^ Graham, Michael C. (2014). Facts of Life: ten issues of contentment. Outskirts Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-4787-2259-5.

- ^ «How to Savor Gratitude and Disarm «Gratitude Traps»«. The Objective Standard. 2020-05-20. Retrieved 2021-02-11.

- ^ «15 Common Cognitive Distortions». PsychCentral. 2016-05-17. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- ^ «Fallacy of Change: 15 types of distorted thinking that lead to massive anxiety 10/15». Abate Counseling. 2018-08-30.

- ^ «Disqualifying the Positive». Palomar. Retrieved 2020-01-03.

- ^ Franceschi, Paul (2007). «Compléments pour une théorie des distorsions cognitives». Journal de Thérapie Comportementale et Cognitive. 17 (2): 84–88. doi:10.1016/s1155-1704(07)89710-2.

- ^ Franceschi, Paul (2009). «Théorie des distorsions cognitives : la sur-généralisation et l’étiquetage». Journal de Thérapie Comportementale et Cognitive. 19 (4): 136–140. doi:10.1016/j.jtcc.2009.10.003.

- ^ Franceschi, Paul (2010). «Théorie des distorsions cognitives : la personnalisation». Journal de Thérapie Comportementale et Cognitive. 20 (2): 51–55. doi:10.1016/j.jtcc.2010.06.006.

- ^ Gil, Pedro J. Moreno; Carrillo, Francisco Xavier Méndez; Meca, Julio Sánchez (2001). «Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural treatment in social phobia: A meta-analytic review». Psychology in Spain. 5: 17–25. S2CID 8860010.

- ^ a b Martin, Ryan C.; Dahlen, Eric R. (2005). «Cognitive emotion regulation in the prediction of depression, anxiety, stress, and anger». Personality and Individual Differences. 39 (7): 1249–1260. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.06.004.

- ^ a b Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association., American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Task Force. (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. 2013. ISBN 9780890425541. OCLC 830807378.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Rush, A.; Khatami, M.; Beck, A. (1975). «Cognitive and Behavior Therapy in Chronic Depression». Behavior Therapy. 6 (3): 398–404. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(75)80116-X.

- ^ Millon, Theodore; Carrie M. Millon; Seth Grossman; Sarah Meagher; Rowena Ramnath (2004). Personality Disorders in Modern Life. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-23734-1.

- ^ Thomas, David (2010). Narcissism: Behind the Mask. ISBN 978-1-84624-506-0.

- ^ Theunissen, Maurice; Peters, Madelon L.; Bruce, Julie; Gramke, Hans-Fritz; Marcus, Marco A. (2012). «Preoperative Anxiety and Catastrophizing» (PDF). The Clinical Journal of Pain. 28 (9): 819–841. doi:10.1097/ajp.0b013e31824549d6. PMID 22760489. S2CID 12414206.

- ^ Moritz, Steffen; Schilling, Lisa; Wingenfeld, Katja; Köther, Ulf; Wittekind, Charlotte; Terfehr, Kirsten; Spitzer, Carsten (2011). «Persecutory delusions and catastrophic worry in psychosis: Developing the understanding of delusion distress and persistence». Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 42 (September 2011): 349–354. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.02.003. PMID 21411041.

- ^ Beidel, Deborah C. (1986). «A Critique of the Theoretical Bases of Cognitive Behavioral Theories and Therapy». Clinical Psychology Review. 6 (2): 177–97. doi:10.1016/0272-7358(86)90011-5.

Ошибки мышления — или когнитивные искажения — это такие мыслительные установки, которые срабатывают автоматически.

Они помогают быстрее обработать поступающую информацию, особенно в условиях угрозы. Это жирный плюс для выживания, поэтому они есть у всех людей. Когнитивные искажения звучат очень убеждающе, насыщены верой, выглядят, как факты.

Однако в большинстве случаев когнитивные искажения описывают реальность некорректно, и ладно если бы они ни на что дальше не влияли. К сожалению, бывает, что мы принимаем важные решения, базируясь только на искажениях.

Когнитивные искажения провоцируют плохое настроение и негативные эмоции.

Полезно знать, каковы твои самые излюбленные когнитивные искажения, потому что тогда ты их быстрее замечаешь и можешь вовремя на ходу исправить.

Как бороться с когнитивными искажениями

Избавиться от искажений вообще, в принципе, свести их к нулю не получится, потому что эта функция встроена в наше мышление много тысяч лет назад. Но вполне можно научиться их обнаруживать и не давать им влиять на важные вещи.

Появление искажения — знак, что прямо сейчас что-то обрабатывается некорректно.

Как это делать:

- Заметил искажение?

- Не воспринимай его всерьез как руководство к действию. Оспорь, подвергни сомнению, подумай, как будет корректнее или объективнее.

Никакого лучшего способа пока не придумали. Если применять регулярно, то со временем есть шанс, что пункт «оспорь-подвергни-подумай» станет ненужным. Сам факт появления когнитивного искажения будет поводом перенаправить ход мыслей.

🔗 На ту же тему: ABC-анализ в когнитивно-поведенческом подходе

Список когнитивных искажений

📌 Сверхобобщение. Берется одна ситуация, один случай, одна вещь — и её исход переносится на большую категорию ситуаций и вещей.

- Я хуже Василия, потому что он идеально катается на лыжах.

- Я плохой психолог, потому что не смог помочь этому клиенту.

📌 Персонализация. Причина всего, что бы не случилось, приписывается себе лично. Случайным событиям придаётся личная значимость.

- Я разорвала пальто, это мне указание от судьбы на то, что нельзя тратить так много денег на вещи.

- Она выглядит недовольной, скорее всего потому что я сделал что-то не то.

📌 Антропоморфизм. Неживые предметы и понятия становятся живыми и действующими.

- Госпожа Удача была против меня, поэтому я проиграл всю зарплату.

- Моя машина как будто бы не хотела туда ехать, надо было прислушаться к ней.

📌 Мышление «Все-или-ничего», черно-белое мышление, дихотомическое мышление. События, люди, результаты и пр. оцениваются по принципу либо круто, либо никак. Либо прекрасный, либо ужасный — середина не существует.

- Этот проект будет полный провал.

- Они абсолютно все не уважают, не ценят и не любят меня, это совершенно ясно.

- Ты или победитель, или проигравший — в этой жизни других вариантов нет.

- Если я не устроюсь на работу в течение двух недель, я перестану себя уважать.

🔗 На ту же тему: Тест, насколько вы перфекционист (Многомерная шкала перфекционизма Хьюитта-Флетта)

📌 Долженствование. Превращение «хочу» в «должен», «обязан», «надо».

- Они должны понимать, что для меня этот вопрос очень важен.

- Я должен ее вернуть во что бы то ни стало.

- Я всегда должен точно понимать, какой смысл или долгосрочная польза от всего, чем я занимаюсь.

📌 Катастрофизация. Предвидится и предполагается только наихудший из возможных исходов.

- Эта боль означает, что у меня рак.

- Каждый раз, когда муж задерживается, я думаю, что он завел интрижку на стороне.

📌 Чтение в головах. Предположения, о чем думают другие люди, становятся фактами.

- Они думают обо мне, что я странный. Что значит «думают ли по-другому»? Нет, конечно. Это факт, они думают, что я странный.

- Если новое начальство меня уволит, все коллеги и знакомые совершенно точно решат, что я — лузер.

📌 Навешивание ярлыков. Раздача людям, событиям, предметам глобальных, общих характеристик. Самый «вред» — от негативных ярлыков.

- Он отвратительный человек, вор, подлец — раздобыл где-то десять пар новых спортивных костюмов с бирками.

- Я бездарь, неуч и лентяй.

📌 Объяснение через эмоции. Объяснение, почему происходит то или иное, делается на базе чувств и эмоций:

- Я чувствую себя тупым, значит, так и есть.

- Мне страшно летать на самолетах, следовательно, летать — небезопасно.

- Нашим отношениям уже ничего не поможет, потому что я очень сильно расстроена.

📌 Туннельное зрение. Обращать внимание только на небольшую часть, деталь, отбрасывая остальные части и целое. Иногда выбираются только негативные детали, а иногда те, которые согласуются с некоей идеей.

- Встретившись, я сразу же начинаю искать и замечать в девушке все недостатки. Через некоторое время мне хочется уже просто сбежать — ведь очевидно, что у нас с ней ничего не получится.

- У них на кухне лежит какая-то видавшая виды губка, а детские игрушки разбросаны по полу. Просто жуткая грязь.

📌 Преувеличение и преуменьшение. Что-то плохое раздувается, а одновременно с этим что-то хорошее — занижается. Собственные результаты обесцениваются и сводятся просто к счастливому стечению обстоятельств.

- Я вставал в 6 утра, в 7:30 начинались репетиторы по английскому, математике и русскому. Да, я сдал экзамены на 290 баллов, но мне просто повезло.

- Менеджер сказал, что он очень доволен моими результатами за квартал. Однако, он заметил, что я иногда опаздывал, и задержал тот проект на неделю. Я плохой работник.

Можно встретить ещё с десяток других логических и когнитивных ошибок, например, то же психологизирование «Я забыл, как его зовут — очевидно, я вытеснил эту информацию», мультяшная вера в силу «Всё, что тебе нужно — это Сердце», априорное мышление, уход в сторону, апелляция к авторитетам и т.п. и т.д.

Одна из попыток систематизировать все косяки нашего мышления на картинке ниже.

Всё это, конечно, весело почитать-посмеяться, но на практике использовать невозможно — слишком уж их много.

Золотая пятерка когнитивных ошибок, которые должен знать наизусть 😄 каждый КПТ-терапевт:

- долженствование,

- дихотомическое мышление,

- сверхобобщение,

- катастрофизация,

- навешивание ярлыков. Ну или чтение в головах — не могу выбрать только одну 😄 .