|

Максим Коллегин |

|

|

Статус: Сотрудник Группы: Администраторы Сказал «Спасибо»: 21 раз |

X86 версия 1с c отключённой службой xtacache должна работать. Пробовали? |

|

Знания в базе знаний, поддержка в техподдержке |

|

|

WWW |

|

Jumuro |

|

|

Статус: Новичок Группы: Участники Сказал(а) «Спасибо»: 1 раз |

Автор: Максим Коллегин X86 версия 1с c отключённой службой xtacache должна работать. Пробовали? Да, пробовал. Перед запуском 1С (x86) останавливал (но не отключал поностью) службу. |

|

|

|

Максим Коллегин |

|

|

Статус: Сотрудник Группы: Администраторы Сказал «Спасибо»: 21 раз |

Если предоставите удаленный доступ — посмотрю. |

|

Знания в базе знаний, поддержка в техподдержке |

|

|

WWW |

|

|

Jumuro

оставлено 07.06.2022(UTC) |

|

Jumuro |

|

|

Статус: Новичок Группы: Участники Сказал(а) «Спасибо»: 1 раз |

Автор: Jumuro Здравствуйте, коллеги! Уже в который раз пытаюсь заставить работать следующую связку: В самой оснастке криптопро всо ок — шифруется и расшифровывается без проблем. Цитата: Язык описания абстрактного синтаксиса данных. Базовый код ошибки кодирования сертификата. 1С:Предприятие 8.3 (8.3.20.1838) (пробовал и x86 и x64) Автор: Максим Коллегин Если предоставите удаленный доступ — посмотрю. Проблема была решена, за что огромное спасибо Максиму Коллегину. |

|

|

|

Максим Коллегин |

|

|

Статус: Сотрудник Группы: Администраторы Сказал «Спасибо»: 21 раз |

Мы перевыложили дистрибутив, проблема должна уйти, единственное, если была установлена очень старая версия CSP — желательно перед установкой CSP её деинсталлировать. |

|

Знания в базе знаний, поддержка в техподдержке |

|

|

WWW |

|

docent_963 |

|

|

Статус: Новичок Группы: Участники

|

Возникла идентичная проблема на 11 Винде. Платформа 20.1914 |

|

|

|

Максим Коллегин |

|

|

Статус: Сотрудник Группы: Администраторы Сказал «Спасибо»: 21 раз |

1С — 32-х битная? CSP установлен с нуля? |

|

Знания в базе знаний, поддержка в техподдержке |

|

|

WWW |

|

docent_963 |

|

|

Статус: Новичок Группы: Участники

|

Платформа х64. CSP скачал поставил (версия дэмо. Кл в процессе приобретения). Что такое xtacache ? |

|

|

|

Максим Коллегин |

|

|

Статус: Сотрудник Группы: Администраторы Сказал «Спасибо»: 21 раз |

Прочитайте пожалуйста первое сообщение в этой теме. |

|

Знания в базе знаний, поддержка в техподдержке |

|

|

WWW |

|

docent_963 |

|

|

Статус: Новичок Группы: Участники

|

Автор: docent_963 Платформа х64. CSP скачал поставил (версия дэмо. Кл в процессе приобретения). Что такое xtacache ? Оказывается при переносе с VIPNET надо было сертификат копировать с форматом шифрования AES. Скопировал заново, передобавил в Крипто про, перезапустил 2 раза базу и заработало. Теперь другие ошибки, но это уже надеюсь не крипто про. |

|

|

| Пользователи, просматривающие эту тему |

|

Guest |

Быстрый переход

Вы не можете создавать новые темы в этом форуме.

Вы не можете отвечать в этом форуме.

Вы не можете удалять Ваши сообщения в этом форуме.

Вы не можете редактировать Ваши сообщения в этом форуме.

Вы не можете создавать опросы в этом форуме.

Вы не можете голосовать в этом форуме.

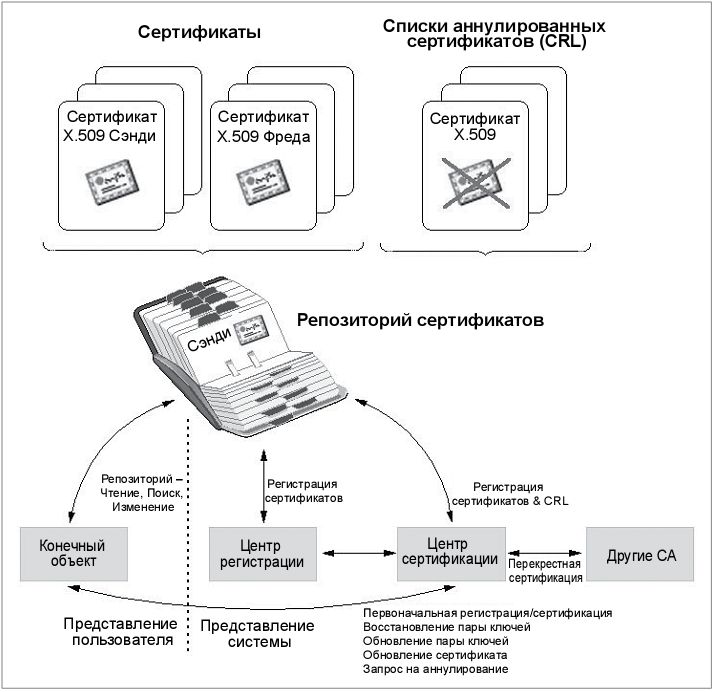

6.2.2 Компоненты инфраструктуры открытых ключей (PKI)

Перед тем как мы подробно коснемся отдельных, предлагаемых PKI служб, в этом разделе мы дадим описание компонентов PKI.

Первоначально «PKI» было общим термином, который просто обозначал набор служб, использующих криптографию на основе открытых ключей. В наши дни «PKI» больше ассоциируется с предоставляемыми инфраструктурой открытых ключей службами либо в виде приложений, либо в виде протоколов. Некоторыми примерами таких служб являются:

- протокол безопасных соединений SSL (Secure Socket Layer);

- безопасный протокол передачи электронной почты S/MIME (Secure Multimedia Internet Mail Extension);

- протокол IPSec (IP Security);

- протокол защищенных электронных транзакций SET (Secure Electronic Transactions);

- программа шифрования PGP (Pretty Good Privacy).

Давайте рассмотрим, что необходимо для обеспечения этих служб, а также те компоненты, которые требуются современной инфраструктуре открытых ключей.

Основные компоненты инфраструктуры открытых ключей (PKI), как показано на рис. 6.17, включают:

- конечные объекты [ End Entity (EE) ];

- центр сертификации [ Certificate Authority (CA) ];

- репозиторий сертификатов [ Certificate Repository (CR) ];

- центр регистрации [ Registration Authority (RA) ];

- цифровые сертификаты [ Digital Certificates (X.509 V3) ];

Далее следуют подробные определения этих компонентов.

Рис.

6.17.

Компоненты PKI

Конечный объект [End-Entity (EE)]

Конечный объект лучше всего определить как пользователя сертификатов PKI либо как систему конечного пользователя, которые являются субъектами сертификатов. Другими словами, в системе PKI конечный объект является общим термином для определения субъекта, который использует некоторые службы или функции системы PKI. Это может быть владелец сертификата (к примеру, человек, организация или какой-либо другой объект) или сторона, запрашивающая сертификат или список аннулированных сертификатов (к примеру, приложение).

Центр сертификации [Certificate Authority (CA)]

Центр сертификации [ Certificate Authority (CA) ] по существу, является подписчиком сертификатов. Центр сертификации, зачастую совместно с центром регистрации (описанным далее), имеет своей обязанностью обеспечивать надлежащую идентификацию сертификата конечного объекта ( ЕЕ ). Логический домен, в котором СА выпускает сертификаты и управляет ими, называется доменом безопасности (security domain), который может быть реализован для защиты множества различных групп разных размеров, начиная от одного контрольного пользователя вплоть до департамента и далее до уровня всей организации. Основные проводимые СА операции включают: выпуск сертификатов, обновление сертификатов и аннулирование сертификатов.

Выпуск сертификатов

СА создает цифровой сертификат путем подписывания его цифровой подписью. По существу пара открытого и секретного ключей генерируется запрашивающим клиентом ( ЕЕ ). После этого клиент передает СА на рассмотрение запрос на выпуск сертификата.

Запрос на выпуск сертификата содержит по меньшей мере открытый ключ клиента и некоторую другую информацию, такую, как имя клиента, адрес электронной почты, почтовый адрес или другую относящуюся к делу информацию. Когда установлен центр регистрации ( RA ), СА делегирует ему процесс верификации клиента и другие функции управления. После подтверждения запроса клиента СА создает цифровой сертификат и подписывает его.

В качестве альтернативы СА может генерировать пару ключей клиента, а впоследствии и подписанный сертификат для этого клиента. Однако этот процесс выполняется достаточно редко, так как секретный ключ необходимо пересылать от СА к клиенту, что может стать слабым местом. Как правило, более безопасным представляется случай, когда клиенты генерируют свои собственные пары ключей, при этом секретные ключи никогда не покидают своей зоны полномочий.

В целях обеспечения правильной работы инфраструктуры открытых ключей основным предположением является то, что любая сторона, которая желает проверить сертификат, должна доверять СА, который произвел его цифровую подпись. В инфраструктуре открытых ключей «А доверяет Б» означает, что «А доверяет центру сертификации, который подписал сертификат Б». Соответственно, в общих чертах, «А доверяет центру сертификации» означает, что «А» имеет локальную копию сертификата этого центра сертификации.

К примеру, при установке безопасного HTTP-соединения посредством SSL основные Web-браузеры имеют список сертификатов нескольких, заслуживающих доверия СА (обычно упоминаемых как Trusted Roots или Trusted CAs), уже зарегистрированных при добавлении и таких, как (но необязательно только их) VeriSign, Entrust, Thawte, Baltimore, IBM World Registry и т. д. Если Web-сервер использует сертификат, который подписан подобным доверенным CA, браузеры будут полностью доверять серверу, за исключением тех случаев, когда пользователь умышленно удаляет сертификат CA-подписчика из списка доверенных СА.

СА способен выпускать определенное количество различных типов сертификатов, таких, как:

- Сертификаты пользователей. Они могут выпускаться для обыкновенного пользователя или для объекта другого типа, такого, как сервер или приложение. После получения сертификата пользователя эти конечные объекты станут доверенными для СА. Если частью инфраструктуры является центр регистрации RA, то он также должен иметь этот сертификат. Сертификат пользователя может быть ограничен до специфических случаев применения и целей (таких, как безопасная электронная почта, безопасный доступ к серверам и т. д.).

- Сертификаты центров сертификации ( СА ). Когда СА выпускает сертификат для самого себя, такой сертификат называется самоподписанным сертификатом или корневым сертификатом для этого СА. Если СА выпускает сертификат для подчиненного СА, то этот сертификат также называется сертификатом СА.

- Перекрестные сертификаты. Они используются для перекрестной сертификации, которая представляет собой процесс аутентификации между доменами безопасности.

Обновление сертификатов

Каждый сертификат имеет период достоверности и связанной с ним датой истечения срока действия. Когда срок действия сертификата истекает, то может быть инициирован процесс его обновления, после одобрения которого для конечного объекта будет выпущен новый сертификат.

Аннулирование сертификатов

Максимальный срок службы сертификата ограничен датой истечения его срока действия. Однако в некоторых случаях возникает необходимость аннулировать сертификаты до наступления этой даты. Когда это случается, CA включает сертификат в список аннулированных сертификатов [Certificate Revocation List ( CRL )]. На самом деле, если быть более точным, CA включает в этот список серийный номер сертификата вместе с некоторой другой информацией. Клиенты, которым необходимо знать о достоверности сертификата, могут осуществлять в CRL поиск по любому уведомлению об аннулировании.

Репозиторий сертификатов (CR)

Репозиторий сертификатов [Certificate Repository ( CR )] является хранилищем выпущенных сертификатов и аннулированных сертификатов в CRL. Несмотря на то что CR необязательный компонент инфраструктуры открытых ключей, он значительно способствует доступности и управляемости PKI.

Так как формат сертификатов X.509 нормально приспособлен к каталогу X.500, то соответственно наилучшим образом будет реализовать CR как каталог (Directory), который затем может быть доступен посредством наиболее общего протокола доступа – облегченного протокола доступа к каталогам LDAP (Lightweight Directory Access Protocol), последней версией которого является LDAP v3.

LDAP является наиболее эффективным и наиболее распространенным методом, с помощью которого конечные объекты или СА извлекают или модифицируют хранящиеся в CR сертификаты и информацию CRL. LDAP предлагает команды или процедуры, которые делают это эффективно и равномерно, такие, как bind, search или modify и unbind. Также для поддержки со стороны сервера LDAP, действующего как сервер CR, определены классы объектов и атрибутов [называемые схемами (Schemas)].

Для получения сертификатов или информации CRL, если в каталоге не реализован CR, существуют альтернативные методы. Однако их применять не рекомендуется, и после рассмотрения требований, которым должен соответствовать CR, все сводится к тому, что каталог на самом деле является лучшим местом для хранения информации CR. Эти требования включают: простую доступность, доступ на основе стандартов, сохранение новейшей информации, встроенную безопасность (если требуется), вопросы управления данными и возможность объединения подобных данных. В случае инфраструктуры открытых ключей в Интернете на основе Domino репозиторием сертификатов является каталог Domino (Domino Directory).

Центр регистрации (RA)

Центр регистрации [Registration Authority ( RA )] является необязательным компонентом инфраструктуры открытых ключей. В некоторых случаях роль RA выполняет CA. Там, где используется отдельный RA, он является доверенным конечным объектом, который сертифицирован CA и действует как подчиненный сервер CA. CA может делегировать некоторые из своих функций управления RA. К примеру, RA может выполнять персональные задачи аутентификации, сообщать об аннулированных сертификатах, генерировать ключи или архивировать пары ключей. Однако RA не производит выпуск сертификатов или CRL.

6.2.3 Сертификаты X.509

Ключевой частью инфраструктуры открытых ключей (и достойной собственного раздела для описания) является сертификат X.509.

Несмотря на то что для сертификатов открытых ключей было предложено несколько форматов, большинство доступных сегодня коммерческих сертификатов основаны на интернациональном стандарте, рекомендации ITU-T X.509 (ранее X.509 организации CCITT).

Сертификаты X.509 обычно используются в защищенных интернет-протоколах, таких, как те, которые мы рассматриваем в настоящей лекции, а именно:

- SSL (Secure Sockets Layer);

- S/MIME (Secure Multipurpose Internet Message Extension).

Что такое стандарт X.509?

Первоначально основной целью стандарта X.509 было определить средства для проведения аутентификации на основе сертификатов по отношению к каталогу X.500. Аутентификация каталогов в X.509 может проводиться с использованием либо техники секретных ключей, либо техники открытых ключей. Последняя основана на сертификатах открытых ключей.

В настоящее время определенный в стандарте X.509 формат сертификата открытого ключа широко используется и поддерживается в мире Интернета определенным количеством протоколов. Стандарт X.509 не устанавливает особого криптографического алгоритма, хотя и производит впечатление, что RSA является единственным наиболее широко используемым алгоритмом.

Краткая история сертификатов X.509

RFC, касающиеся электронной почты повышенной защиты [Privacy Enhanced Mail (PEM)] в Интернете, которые были опубликованы в 1993 г., включают спецификации для инфраструктуры открытых ключей на основе сертификатов X.509 v1 (за подробностями обратитесь к RFC 1422). Опыт, приобретенный при осуществлении попыток использовать RFC 1422, ясно выявил, что форматы сертификатов v1 и v2 были не совсем полными в некоторых отношениях. Наиболее существенной была необходимость в большем количестве полей для размещения требуемой и нужной информации. Для удовлетворения этих новых требований организации ISO/IEC/ITU и ANSI X9 разработали формат сертификата X.509 версии 3 (v3). Формат v3 расширил формат v2 за счет обеспечения дополнительными полями расширения.

Эти поля предоставляют большую гибкость по причине того, что они могут сообщать дополнительную информацию вдобавок к наличию только ключа и связанного с ним имени. Стандартизация основного формата v3 была завершена в июне 1996 г.

Содержимое сертификата X.509

Сертификат X.509 состоит из следующих полей:

- Версия сертификата;

- Серийный номер сертификата;

- Идентификатор алгоритма цифровой подписи (для цифровой подписи выпускающего сертификат);

- Имя выпускающего сертификат (это имя СА);

- Период достоверности;

- Имя субъекта (пользователя или сервера);

- Информация об открытом ключе субъекта: идентификатор алгоритма и значение открытого ключа;

- Уникальный идентификатор выпускающего сертификат – только для версий 2 и 3 (добавлено в версии 2);

- Уникальный идентификатор субъекта – только для версий 2 и 3 (добавлено в версии 2);

- Расширения – только для версии 3 (добавлено в версии 3);

- Цифровая подпись выпускающего сертификат для полей выше.

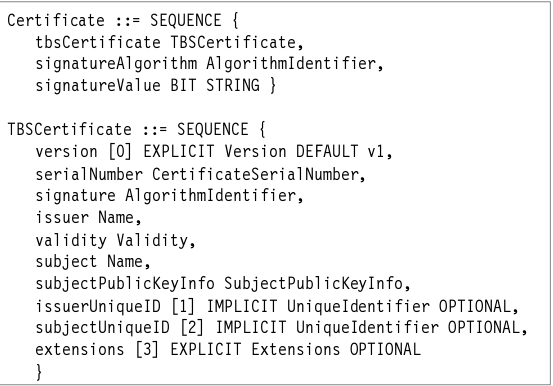

Стандартные расширения включают среди прочих атрибуты субъекта и выпускающего сертификат, информацию о политике сертификации, ограничения в использовании ключей. Структура сертификата X.509 V3 проиллюстрирована на рис. 6.18.

Данные сертификата записываются согласно правилу синтаксиса системы обозначений для описания абстрактного синтаксиса 1 (ASN. 1), как это можно увидеть на рис. 6.19.

Рис.

6.19.

Представление сертификата X.509 согласно системе обозначений для описания абстрактного синтаксиса 1 (ASN. 1)

После этого они конвертируются в двоичные данные в соответствии с характерными правилами кодирования ASN.1, который является языком описания данных и определен организацией ITU-T как стандарты X.208 и X.209. Эта операция позволяет сделать данные сертификата независимыми от правил кодирования каждой конкретной платформы.

В некоторых полях сертификата для представления специальной последовательности значений параметров используется идентификатор объекта [object identifier ( OID )]. К примеру, на рис. 6.19 можно увидеть AlgorithmIdentifier для signatureAlgorithm, который фактически состоит из идентификатора объекта ( OID ) и необязательных параметров. Этот OID представляет конкретный алгоритм, используемый для цифровых подписей выпускающего сертификат ( СА ). Приложение, которое проверяет подпись сертификата, должно понимать OID, который представляет алгоритм шифрования и алгоритм сборника сообщений наряду с другой информацией.

| Abstract Syntax Notation One | |

| Status | In force; supersedes X.208 and X.209 (1988) |

|---|---|

| Year started | 1984 |

| Latest version | (02/21) February 2021 |

| Organization | ITU-T |

| Committee | Study Group 17 |

| Base standards | ASN.1 |

| Related standards | X.208, X.209, X.409, X.509, X.680, X.681, X.682, X.683 |

| Domain | cryptography, telecommunications |

| Website | https://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-X.680/ |

Abstract Syntax Notation One (ASN.1) is a standard interface description language for defining data structures that can be serialized and deserialized in a cross-platform way. It is broadly used in telecommunications and computer networking, and especially in cryptography.[1]

Protocol developers define data structures in ASN.1 modules, which are generally a section of a broader standards document written in the ASN.1 language. The advantage is that the ASN.1 description of the data encoding is independent of a particular computer or programming language. Because ASN.1 is both human-readable and machine-readable, an ASN.1 compiler can compile modules into libraries of code, codecs, that decode or encode the data structures. Some ASN.1 compilers can produce code to encode or decode several encodings, e.g. packed, BER or XML.

ASN.1 is a joint standard of the International Telecommunication Union Telecommunication Standardization Sector (ITU-T) in ITU-T Study Group 17 and ISO/IEC, originally defined in 1984 as part of CCITT X.409:1984.[2] In 1988, ASN.1 moved to its own standard, X.208, due to wide applicability. The substantially revised 1995 version is covered by the X.680 series.[3] The latest revision of the X.680 series of recommendations is the 6.0 Edition, published in 2021.

Language support[edit]

ASN.1 is a data type declaration notation. It does not define how to manipulate a variable of such a type. Manipulation of variables is defined in other languages such as SDL (Specification and Description Language) for executable modeling or TTCN-3 (Testing and Test Control Notation) for conformance testing. Both these languages natively support ASN.1 declarations. It is possible to import an ASN.1 module and declare a variable of any of the ASN.1 types declared in the module.

Applications[edit]

ASN.1 is used to define a large number of protocols. Its most extensive uses continue to be telecommunications, cryptography, and biometrics.

| Protocol | Specification | Specified or customary encoding rules | Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interledger Protocol | https://interledger.org/rfcs/asn1/index.html | Octet Encoding Rules | |

| NTCIP 1103 — Transport Management Protocols | NTCIP 1103 | Octet Encoding Rules | Traffic, Transportation, and Infrastructure Management |

| X.500 Directory Services | The ITU X.500 Recommendation Series | Basic Encoding Rules, Distinguished Encoding Rules | LDAP, TLS (X.509) Certificates, Authentication |

| Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP) | RFC 4511 | Basic Encoding Rules | |

| PKCS Cryptography Standards | PKCS Cryptography Standards | Basic Encoding Rules and Distinguished Encoding Rules | Asymmetric Keys, certificate bundles |

| X.400 Message Handling | The ITU X.400 Recommendation Series | An early competitor to email | |

| EMV | EMVCo Publications | Payment cards | |

| T.120 Multimedia conferencing | The ITU T.120 Recommendation Series | Basic Encoding Rules, Packed Encoding Rules | Microsoft’s Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) |

| Simple Network Management Protocol (SNMP) | RFC 1157 | Basic Encoding Rules | Managing and monitoring networks and computers, particularly characteristics pertaining to performance and reliability |

| Common Management Information Protocol (CMIP) | ITU Recommendation X.711 | A competitor to SNMP but more capable and not nearly as popular | |

| Signalling System No. 7 (SS7) | The ITU Q.700 Recommendation Series | Managing telephone connections over the Public Switched Telephone Network (PSTN) | |

| ITU H-Series Multimedia Protocols | The ITU H.200, H.300, and H.400 Recommendation Series | Voice Over Internet Protocol (VOIP) | |

| BioAPI Interworking Protocol (BIP) | ISO/IEC 24708:2008 | ||

| Common Biometric Exchange Formats Framework (CBEFF) | NIST IR 6529-A | Basic Encoding Rules | |

| Authentication Contexts for Biometrics (ACBio) | ISO/IEC 24761:2019 | ||

| Computer-supported telecommunications applications (CSTA) | https://www.ecma-international.org/activities/Communications/TG11/cstaIII.htm | Basic Encoding Rules | |

| Dedicated short-range communications (DSRC) | SAE J2735 | Packed Encoding Rules | Vehicle communication |

| IEEE 802.11p (IEEE WAVE) | IEEE 1609.2 | Vehicle communication | |

| Intelligent Transport Systems (ETSI ITS) | ETSI EN 302 637 2 (CAM) ETSI EN 302 637 3 (DENM) | Vehicle communication | |

| Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM) | http://www.ttfn.net/techno/smartcards/gsm11-11.pdf | 2G Mobile Phone Communications | |

| General Packet Radio Service (GPRS) / Enhanced Data rates for GSM Evolution (EDGE) | http://www.3gpp.org/technologies/keywords-acronyms/102-gprs-edge | 2.5G Mobile Phone Communications | |

| Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (UMTS) | http://www.3gpp.org/DynaReport/25-series.htm | 3G Mobile Phone Communications | |

| Long-Term Evolution (LTE) | http://www.3gpp.org/technologies/keywords-acronyms/98-lte | 4G Mobile Phone Communications | |

| 5G | https://www.3gpp.org/news-events/3gpp-news/1987-imt2020_workshop | 5G Mobile Phone Communications | |

| Common Alerting Protocol (CAP) | http://docs.oasis-open.org/emergency/cap/v1.2/CAP-v1.2-os.html | XML Encoding Rules | Exchanging Alert Information, such as Amber Alerts |

| Controller–pilot data link communications (CPDLC) | Aeronautics communications | ||

| Space Link Extension Services (SLE) | Space systems communications | ||

| Manufacturing Message Specification (MMS) | ISO 9506-1:2003 | Manufacturing | |

| File Transfer, Access and Management (FTAM) | An early and more capable competitor to File Transfer Protocol, but its rarely used anymore. | ||

| Remote Operations Service Element protocol (ROSE) | ITU Recommendations X.880, X.881, and X.882 | An early form of Remote procedure call | |

| Association Control Service Element (ACSE) | ITU Recommendation X.227 | ||

| Building Automation and Control Networks Protocol (BACnet) | ASHRAE 135-2020 | BACnet Encoding Rules | Building automation and control, such as with fire alarms, elevators, HVAC systems, etc. |

| Kerberos | RFC 4120 | Basic Encoding Rules | Secure authentication |

| WiMAX 2 | Wide Area Networks | ||

| Intelligent Network | The ITU Q.1200 Recommendation Series | Telecommunications and computer networking | |

| X2AP | Basic Aligned Packed Encoding Rules |

Encodings[edit]

ASN.1 is closely associated with a set of encoding rules that specify how to represent a data structure as a series of bytes. The standard ASN.1 encoding rules include:

| Encoding rules | Object identifier | Object descriptor value |

Specification |

Unit of serialization |

Encoded elements |

Octet aligned |

Encoding control |

Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dotted | IRI | ||||||||

| Basic Encoding Rules (BER)[4] | 2.1.1 | /ASN.1/Basic-Encoding | Basic Encoding of a single ASN.1 type | ITU X.690 | Octet | Yes | Yes | No | The first specified encoding rules. Encodes elements as tag-length-value (TLV) sequences. Typically provides several options as to how data values are to be encoded. This is one of the more flexible encoding rules. |

| Distinguished Encoding Rules (DER)[5] | 2.1.2.1 | /ASN.1/BER‑Derived/Distinguished‑Encoding | Distinguished encoding of a single ASN.1 type | ITU X.690 | Octet | Yes | Yes | No | A restricted subset of the Basic Encoding Rules (BER). Typically used for things that are digitally-signed because, since the DER allow for fewer options for encoding, and because DER-encoded values are more likely to be re-encoded on the exact same bytes, digital signatures produced by a given abstract value will be the same across implementations and digital signatures produced over DER-encoded data will be less susceptible to collision-based attacks. |

| Canonical Encoding Rules (CER)[6] | 2.1.2.0 | /ASN.1/BER‑Derived/Canonical‑Encoding | Canonical encoding of a single ASN.1 type | ITU X.690 | Octet | Yes | Yes | No | A restricted subset of the Basic Encoding Rules (BER). Employs almost all of the same restrictions as the Distinguished Encoding Rules (DER), but the noteworthy difference is that the CER specify that many large values (especially strings) are to be «chopped up» into individual substring elements at the 1000-byte or 1000-character mark (depending on the data type). |

| Basic Packed Encoding Rules (PER) Aligned[7] | 2.1.3.0.0 | /ASN.1/Packed‑Encoding/Basic/Aligned | Packed encoding of a single ASN.1 type (basic aligned) | ITU X.691 | Bit | No | Yes | No | Encodes values on bits, but if the bits encoded are not evenly divisible by eight, padding bits are added until an integral number of octets encode the value. Capable of producing very compact encodings, but at the expense of complexity, and the PER are highly dependent upon constraints placed on data types. |

| Basic Packed Encoding Rules (PER) Unaligned[7] | 2.1.3.0.1 | /ASN.1/Packed‑Encoding/Basic/Unaligned | Packed encoding of a single ASN.1 type (basic unaligned) | ITU X.691 | Bit | No | No | No | A variant of the Aligned Basic Packed Encoding Rules (PER), but it does not pad data values with bits to produce an integral number of octets. |

| Canonical Packed Encoding Rules (CPER) Aligned[7] | 2.1.3.1.0 | /ASN.1/Packed‑Encoding/Canonical/Aligned | Packed encoding of a single ASN.1 type (canonical aligned) | ITU X.691 | Bit | No | Yes | No | A variant of the Packed Encoding Rules (PER) that specifies a single way of encoding values. The Canonical Packed Encoding Rules have a similar relationship to the Packed Encoding Rules that the Distinguished Encoding Rules (DER) and the Canonical Encoding Rules (CER) have to the Basic Encoding Rules (BER). |

| Canonical Packed Encoding Rules (CPER) Unaligned[7] | 2.1.3.1.1 | /ASN.1/Packed‑Encoding/Canonical/Unaligned | Packed encoding of a single ASN.1 type (canonical unaligned) | ITU X.691 | Bit | No | No | No | A variant of the Aligned Canonical Packed Encoding Rules (CPER), but it does not pad data values with bits to produce an integral number of octets. |

| Basic XML Encoding Rules (XER)[8] | 2.1.5.0 | /ASN.1/XML‑Encoding/Basic | Basic XML encoding of a single ASN.1 type | ITU X.693 | Character | Yes | Yes | Yes | Encodes ASN.1 data as XML. |

| Canonical XML Encoding Rules (CXER)[8] | 2.1.5.1 | /ASN.1/XML‑Encoding/Canonical | Canonical XML encoding of a single ASN.1 type | ITU X.693 | Character | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Extended XML Encoding Rules (EXER)[8] | 2.1.5.2 | /ASN.1/XML‑Encoding/Extended | Extended XML encoding of a single ASN.1 type | ITU X.693 | Character | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Octet Encoding Rules (OER)[9] | 2.1.6.0 | Basic OER encoding of a single ASN.1 type | ITU X.696 | Octet | No | Yes | A set of encoding rules that encodes values on octets, but does not encode tags or length determinants like the Basic Encoding Rules (BER). Data values encoded using the Octet Encoding Rules often look like those found in «record-based» protocols. The Octet Encoding Rules (OER) were designed to be easy to implement and to produce encodings more compact than those produced by the Basic Encoding Rules (BER). In addition to reducing the effort of developing encoder/decoders, the use of OER can decrease bandwidth utilization (though not as much as the Packed Encoding Rules), save CPU cycles, and lower encoding/decoding latency. | ||

| Canonical Encoding Rules (OER)[9] | 2.1.6.1 | Canonical OER encoding of a single ASN.1 type | ITU X.696 | Octet | No | Yes | |||

| JSON Encoding Rules (JER)[10] | ITU X.697 | Character | Yes | Yes | Yes | Encodes ASN.1 data as JSON. | |||

| Generic String Encoding Rules (GSER)[11] | 1.2.36.79672281.0.0 | Generic String Encoding Rules (GSER) | RFC 3641 | Character | Yes | No | An incomplete specification for encoding rules that produce human-readable values. The purpose of GSER is to represent encoded data to the user or input data from the user, in a very straightforward format. GSER was originally designed for the Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP) and is rarely used outside of it. The use of GSER in actual protocols is discouraged since not all character string encodings supported by ASN.1 can be reproduced in it. | ||

| BACnet Encoding Rules | ASHRAE 135 | Octet | Yes | Yes | Yes | Encodes elements as tag-length-value (TLV) sequences like the Basic Encoding Rules (BER). | |||

| Signalling Specific Encoding Rules (SER) | France Telecom R&D Internal Document | Octet | Yes | Yes | Used primarily in telecommunications related protocols, such as GSM and SS7. Designed to produce an identical encoding from ASN.1 that previously-existing protocols not specified in ASN.1 would produce. | ||||

| Lightweight Encoding Rules (LWER) | Internal document by INRIA. | Memory Word | Yes | Originates from an internal document produced by INRIA detailing the «Flat Tree Light Weight Syntax» (FTLWS). Abandoned in 1997 due to the superior performance of the Packed Encoding Rules (PER). Optionally Big-Endian or Little-Endian transmission as well as 8-bit, 16-bit, and 32-bit memory words. (Therefore, there are six variants, since there are six combinations of those options.) | |||||

| Minimum Bit Encoding Rules (MBER) | Bit | Proposed in the 1980s. Meant to be as compact as possible, like the Packed Encoding Rules (PER). | |||||||

| NEMA Packed Encoding Rules | Bit | An incomplete encoding rule specification produced by NEMA. It is incomplete because it cannot encode and decode all ASN.1 data types. Compact like the Packed Encoding Rules (PER). | |||||||

| High Speed Coding Rules | «Coding Rules for High Speed Networks» | Definition of these encoding rules were a byproduct of INRIA’s work on the Flat Tree Light Weight Syntax (FTLWS). |

Encoding Control Notation[edit]

ASN.1 recommendations provide a number of predefined encoding rules. If none of the existing encoding rules are suitable, the Encoding Control Notation (ECN) provides a way for a user to define his or her own customized encoding rules.

Relation to Privacy-Enhanced Mail (PEM) Encoding[edit]

Privacy-Enhanced Mail (PEM) encoding is entirely unrelated to ASN.1 and its codecs, but encoded ASN.1 data, which is often binary, is often PEM-encoded so that it can be transmitted as textual data, e.g. over SMTP relays, or through copy/paste buffers.

Example[edit]

This is an example ASN.1 module defining the messages (data structures) of a fictitious Foo Protocol:

FooProtocol DEFINITIONS ::= BEGIN

FooQuestion ::= SEQUENCE {

trackingNumber INTEGER,

question IA5String

}

FooAnswer ::= SEQUENCE {

questionNumber INTEGER,

answer BOOLEAN

}

END

This could be a specification published by creators of Foo Protocol. Conversation flows, transaction interchanges, and states are not defined in ASN.1, but are left to other notations and textual description of the protocol.

Assuming a message that complies with the Foo Protocol and that will be sent to the receiving party, this particular message (protocol data unit (PDU)) is:

myQuestion FooQuestion ::= {

trackingNumber 5,

question "Anybody there?"

}

ASN.1 supports constraints on values and sizes, and extensibility. The above specification can be changed to

FooProtocol DEFINITIONS ::= BEGIN

FooQuestion ::= SEQUENCE {

trackingNumber INTEGER(0..199),

question IA5String

}

FooAnswer ::= SEQUENCE {

questionNumber INTEGER(10..20),

answer BOOLEAN

}

FooHistory ::= SEQUENCE {

questions SEQUENCE(SIZE(0..10)) OF FooQuestion,

answers SEQUENCE(SIZE(1..10)) OF FooAnswer,

anArray SEQUENCE(SIZE(100)) OF INTEGER(0..1000),

...

}

END

This change constrains trackingNumbers to have a value between 0 and 199 inclusive, and questionNumbers to have a value between 10 and 20 inclusive. The size of the questions array can be between 0 and 10 elements, with the answers array between 1 and 10 elements. The anArray field is a fixed length 100 element array of integers that must be in the range 0 to 1000. The ‘…’ extensibility marker means that the FooHistory message specification may have additional fields in future versions of the specification; systems compliant with one version should be able to receive and transmit transactions from a later version, though able to process only the fields specified in the earlier version. Good ASN.1 compilers will generate (in C, C++, Java, etc.) source code that will automatically check that transactions fall within these constraints. Transactions that violate the constraints should not be accepted from, or presented to, the application. Constraint management in this layer significantly simplifies protocol specification because the applications will be protected from constraint violations, reducing risk and cost.

To send the myQuestion message through the network, the message is serialized (encoded) as a series of bytes using one of the encoding rules. The Foo protocol specification should explicitly name one set of encoding rules to use, so that users of the Foo protocol know which one they should use and expect.

Example encoded in DER[edit]

Below is the data structure shown above as myQuestion encoded in DER format (all numbers are in hexadecimal):

30 13 02 01 05 16 0e 41 6e 79 62 6f 64 79 20 74 68 65 72 65 3f

DER is a type–length–value encoding, so the sequence above can be interpreted, with reference to the standard SEQUENCE, INTEGER, and IA5String types, as follows:

30 — type tag indicating SEQUENCE

13 — length in octets of value that follows

02 — type tag indicating INTEGER

01 — length in octets of value that follows

05 — value (5)

16 — type tag indicating IA5String

(IA5 means the full 7-bit ISO 646 set, including variants,

but is generally US-ASCII)

0e — length in octets of value that follows

41 6e 79 62 6f 64 79 20 74 68 65 72 65 3f — value ("Anybody there?")

Example encoded in XER[edit]

Alternatively, it is possible to encode the same ASN.1 data structure with XML Encoding Rules (XER) to achieve greater human readability «over the wire». It would then appear as the following 108 octets, (space count includes the spaces used for indentation):

<FooQuestion> <trackingNumber>5</trackingNumber> <question>Anybody there?</question> </FooQuestion>

Example encoded in PER (unaligned)[edit]

Alternatively, if Packed Encoding Rules are employed, the following 122 bits (16 octets amount to 128 bits, but here only 122 bits carry information and the last 6 bits are merely padding) will be produced:

01 05 0e 83 bb ce 2d f9 3c a0 e9 a3 2f 2c af c0

In this format, type tags for the required elements are not encoded, so it cannot be parsed without knowing the expected schemas used to encode. Additionally, the bytes for the value of the IA5String are packed using 7-bit units instead of 8-bit units, because the encoder knows that encoding an IA5String byte value requires only 7 bits. However the length bytes are still encoded here, even for the first integer tag 01 (but a PER packer could also omit it if it knows that the allowed value range fits on 8 bits, and it could even compact the single value byte 05 with less than 8 bits, if it knows that allowed values can only fit in a smaller range).

The last 6 bits in the encoded PER are padded with null bits in the 6 least significant bits of the last byte c0 : these extra bits may not be transmitted or used for encoding something else if this sequence is inserted as a part of a longer unaligned PER sequence.

This means that unaligned PER data is essentially an ordered stream of bits, and not an ordered stream of bytes like with aligned PER, and that it will be a bit more complex to decode by software on usual processors because it will require additional contextual bit-shifting and masking and not direct byte addressing (but the same remark would be true with modern processors and memory/storage units whose minimum addressable unit is larger than 1 octet). However modern processors and signal processors include hardware support for fast internal decoding of bit streams with automatic handling of computing units that are crossing the boundaries of addressable storage units (this is needed for efficient processing in data codecs for compression/decompression or with some encryption/decryption algorithms).

If alignment on octet boundaries was required, an aligned PER encoder would produce:

01 05 0e 41 6e 79 62 6f 64 79 20 74 68 65 72 65 3f

(in this case, each octet is padded individually with null bits on their unused most significant bits).

Tools[edit]

Most of the tools supporting ASN.1 do the following:

- parse the ASN.1 files,

- generates the equivalent declaration in a programming language (like C or C++),

- generates the encoding and decoding functions based on the previous declarations.

A list of tools supporting ASN.1 can be found on the ITU-T Tool web page.

Online tools[edit]

- ASN1 Web Tool (very limited)

- ASN1 Playground (sandbox)

Comparison to similar schemes[edit]

ASN.1 is similar in purpose and use to protocol buffers and Apache Thrift, which are also interface description languages for cross-platform data serialization. Like those languages, it has a schema (in ASN.1, called a «module»), and a set of encodings, typically type–length–value encodings. Unlike them, ASN.1 does not provide a single and readily usable open-source implementation, and is published as a specification to be implemented by third-party vendors. However, ASN.1, defined in 1984, predates them by many years. It also includes a wider variety of basic data types, some of which are obsolete, and has more options for extensibility. A single ASN.1 message can include data from multiple modules defined in multiple standards, even standards defined years apart.

ASN.1 also includes built-in support for constraints on values and sizes. For instance, a module can specify an integer field that must be in the range 0 to 100. The length of a sequence of values (an array) can also be specified, either as a fixed length or a range of permitted lengths. Constraints can also be specified as logical combinations of sets of basic constraints.

Values used as constraints can either be literals used in the PDU specification, or ASN.1 values specified elsewhere in the schema file. Some ASN.1 tools will make these ASN.1 values available to programmers in the generated source code. Used as constants for the protocol being defined, developers can use these in the protocol’s logic implementation. Thus all the PDUs and protocol constants can be defined in the schema, and all implementations of the protocol in any supported language draw upon those values. This avoids the need for developers to hand code protocol constants in their implementation’s source code. This significantly aids protocol development; the protocol’s constants can be altered in the ASN.1 schema and all implementations are updated simply by recompiling, promoting a rapid and low risk development cycle.

If the ASN.1 tools properly implement constraints checking in the generated source code, this acts to automatically validate protocol data during program operation. Generally ASN.1 tools will include constraints checking into the generated serialization / deserialization routines, raising errors or exceptions if out-of-bounds data is encountered. It is complex to implement all aspects of ASN.1 constraints in an ASN.1 compiler. Not all tools support the full range of possible constraints expressions. XML schema and JSON schema both support similar constraints concepts. Tool support for constraints varies. Microsoft’s xsd.exe compiler ignores them.

ASN.1 is visually similar to Augmented Backus-Naur form (ABNF), which is used to define many Internet protocols like HTTP and SMTP. However, in practice they are quite different: ASN.1 defines a data structure, which can be encoded in various ways (e.g. JSON, XML, binary). ABNF, on the other hand, defines the encoding («syntax») at the same time it defines the data structure («semantics»). ABNF tends to be used more frequently for defining textual, human-readable protocols, and generally is not used to define type–length–value encodings.

Many programming languages define language-specific serialization formats. For instance, Python’s «pickle» module and Ruby’s «Marshal» module. These formats are generally language specific. They also don’t require a schema, which makes them easier to use in ad hoc storage scenarios, but inappropriate for communications protocols.

JSON and XML similarly do not require a schema, making them easy to use. They are also both cross-platform standards that are broadly popular for communications protocols, particularly when combined with a JSON schema or XML schema.

Some ASN.1 tools are able to translate between ASN.1 and XML schema (XSD). The translation is standardised by the ITU. This makes it possible for a protocol to be defined in ASN.1, and also automatically in XSD. Thus it is possible (though perhaps ill-advised) to have in a project an XSD schema being compiled by ASN.1 tools producing source code that serializes objects to/from JSON wireformat. A more practical use is to permit other sub-projects to consume an XSD schema instead of an ASN.1 schema, perhaps suiting tools availability for the sub-projects language of choice, with XER used as the protocol wireformat.

For more detail, see Comparison of data serialization formats.

See also[edit]

- X.690

- Information Object Class (ASN.1)

- Presentation layer

References[edit]

- ^ «Introduction to ASN.1». ITU. Archived from the original on 2021-04-09. Retrieved 2021-04-09.

- ^ «ITU-T Recommendation database». ITU. Retrieved 2017-03-06.

- ^ ITU-T X.680 — Specification of basic notation

- ^ ITU-T X.690 — Basic Encoding Rules (BER)

- ^ ITU-T X.690 — Distinguished Encoding Rules (DER)

- ^ ITU-T X.690 — Canonical Encoding Rules (CER)

- ^ a b c d ITU-T X.691 — Packed Encoding Rules (PER)

- ^ a b c ITU-T X.693 — XML Encoding Rules (XER)

- ^ a b ITU-T X.696 — Octet Encoding Rules (OER)

- ^ ITU-T X.697 — JavaScript Object Notation Encoding Rules (JER)

- ^ RFC 3641 — Generic String Encoding Rules (GSER)

External links[edit]

- A Layman’s Guide to a Subset of ASN.1, BER, and DER A good introduction for beginners

- ITU-T website — Introduction to ASN.1

- A video introduction to ASN.1

- ASN.1 Tutorial Tutorial on basic ASN.1 concepts

- ASN.1 Tutorial Tutorial on ASN.1

- An open-source ASN.1->C++ compiler; Includes some ASN.1 specs., An on-line ASN.1->C++ Compiler

- ASN.1 decoder Allows decoding ASN.1 encoded messages into XML output.

- ASN.1 syntax checker and encoder/decoder Checks the syntax of an ASN.1 schema and encodes/decodes messages.

- ASN.1 encoder/decoder of 3GPP messages Encodes/decodes ASN.1 3GPP messages and allows easy editing of these messages.

- Free books about ASN.1

- List of ASN.1 tools at IvmaiAsn project

- Overview of the Octet Encoding Rules (OER)

- Overview of the JSON Encoding Rules (JER)

- A Typescript node utility to parse and validate ASN.1 messages

| Abstract Syntax Notation One | |

| Status | In force; supersedes X.208 and X.209 (1988) |

|---|---|

| Year started | 1984 |

| Latest version | (02/21) February 2021 |

| Organization | ITU-T |

| Committee | Study Group 17 |

| Base standards | ASN.1 |

| Related standards | X.208, X.209, X.409, X.509, X.680, X.681, X.682, X.683 |

| Domain | cryptography, telecommunications |

| Website | https://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-X.680/ |

Abstract Syntax Notation One (ASN.1) is a standard interface description language for defining data structures that can be serialized and deserialized in a cross-platform way. It is broadly used in telecommunications and computer networking, and especially in cryptography.[1]

Protocol developers define data structures in ASN.1 modules, which are generally a section of a broader standards document written in the ASN.1 language. The advantage is that the ASN.1 description of the data encoding is independent of a particular computer or programming language. Because ASN.1 is both human-readable and machine-readable, an ASN.1 compiler can compile modules into libraries of code, codecs, that decode or encode the data structures. Some ASN.1 compilers can produce code to encode or decode several encodings, e.g. packed, BER or XML.

ASN.1 is a joint standard of the International Telecommunication Union Telecommunication Standardization Sector (ITU-T) in ITU-T Study Group 17 and ISO/IEC, originally defined in 1984 as part of CCITT X.409:1984.[2] In 1988, ASN.1 moved to its own standard, X.208, due to wide applicability. The substantially revised 1995 version is covered by the X.680 series.[3] The latest revision of the X.680 series of recommendations is the 6.0 Edition, published in 2021.

Language support[edit]

ASN.1 is a data type declaration notation. It does not define how to manipulate a variable of such a type. Manipulation of variables is defined in other languages such as SDL (Specification and Description Language) for executable modeling or TTCN-3 (Testing and Test Control Notation) for conformance testing. Both these languages natively support ASN.1 declarations. It is possible to import an ASN.1 module and declare a variable of any of the ASN.1 types declared in the module.

Applications[edit]

ASN.1 is used to define a large number of protocols. Its most extensive uses continue to be telecommunications, cryptography, and biometrics.

| Protocol | Specification | Specified or customary encoding rules | Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interledger Protocol | https://interledger.org/rfcs/asn1/index.html | Octet Encoding Rules | |

| NTCIP 1103 — Transport Management Protocols | NTCIP 1103 | Octet Encoding Rules | Traffic, Transportation, and Infrastructure Management |

| X.500 Directory Services | The ITU X.500 Recommendation Series | Basic Encoding Rules, Distinguished Encoding Rules | LDAP, TLS (X.509) Certificates, Authentication |

| Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP) | RFC 4511 | Basic Encoding Rules | |

| PKCS Cryptography Standards | PKCS Cryptography Standards | Basic Encoding Rules and Distinguished Encoding Rules | Asymmetric Keys, certificate bundles |

| X.400 Message Handling | The ITU X.400 Recommendation Series | An early competitor to email | |

| EMV | EMVCo Publications | Payment cards | |

| T.120 Multimedia conferencing | The ITU T.120 Recommendation Series | Basic Encoding Rules, Packed Encoding Rules | Microsoft’s Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) |

| Simple Network Management Protocol (SNMP) | RFC 1157 | Basic Encoding Rules | Managing and monitoring networks and computers, particularly characteristics pertaining to performance and reliability |

| Common Management Information Protocol (CMIP) | ITU Recommendation X.711 | A competitor to SNMP but more capable and not nearly as popular | |

| Signalling System No. 7 (SS7) | The ITU Q.700 Recommendation Series | Managing telephone connections over the Public Switched Telephone Network (PSTN) | |

| ITU H-Series Multimedia Protocols | The ITU H.200, H.300, and H.400 Recommendation Series | Voice Over Internet Protocol (VOIP) | |

| BioAPI Interworking Protocol (BIP) | ISO/IEC 24708:2008 | ||

| Common Biometric Exchange Formats Framework (CBEFF) | NIST IR 6529-A | Basic Encoding Rules | |

| Authentication Contexts for Biometrics (ACBio) | ISO/IEC 24761:2019 | ||

| Computer-supported telecommunications applications (CSTA) | https://www.ecma-international.org/activities/Communications/TG11/cstaIII.htm | Basic Encoding Rules | |

| Dedicated short-range communications (DSRC) | SAE J2735 | Packed Encoding Rules | Vehicle communication |

| IEEE 802.11p (IEEE WAVE) | IEEE 1609.2 | Vehicle communication | |

| Intelligent Transport Systems (ETSI ITS) | ETSI EN 302 637 2 (CAM) ETSI EN 302 637 3 (DENM) | Vehicle communication | |

| Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM) | http://www.ttfn.net/techno/smartcards/gsm11-11.pdf | 2G Mobile Phone Communications | |

| General Packet Radio Service (GPRS) / Enhanced Data rates for GSM Evolution (EDGE) | http://www.3gpp.org/technologies/keywords-acronyms/102-gprs-edge | 2.5G Mobile Phone Communications | |

| Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (UMTS) | http://www.3gpp.org/DynaReport/25-series.htm | 3G Mobile Phone Communications | |

| Long-Term Evolution (LTE) | http://www.3gpp.org/technologies/keywords-acronyms/98-lte | 4G Mobile Phone Communications | |

| 5G | https://www.3gpp.org/news-events/3gpp-news/1987-imt2020_workshop | 5G Mobile Phone Communications | |

| Common Alerting Protocol (CAP) | http://docs.oasis-open.org/emergency/cap/v1.2/CAP-v1.2-os.html | XML Encoding Rules | Exchanging Alert Information, such as Amber Alerts |

| Controller–pilot data link communications (CPDLC) | Aeronautics communications | ||

| Space Link Extension Services (SLE) | Space systems communications | ||

| Manufacturing Message Specification (MMS) | ISO 9506-1:2003 | Manufacturing | |

| File Transfer, Access and Management (FTAM) | An early and more capable competitor to File Transfer Protocol, but its rarely used anymore. | ||

| Remote Operations Service Element protocol (ROSE) | ITU Recommendations X.880, X.881, and X.882 | An early form of Remote procedure call | |

| Association Control Service Element (ACSE) | ITU Recommendation X.227 | ||

| Building Automation and Control Networks Protocol (BACnet) | ASHRAE 135-2020 | BACnet Encoding Rules | Building automation and control, such as with fire alarms, elevators, HVAC systems, etc. |

| Kerberos | RFC 4120 | Basic Encoding Rules | Secure authentication |

| WiMAX 2 | Wide Area Networks | ||

| Intelligent Network | The ITU Q.1200 Recommendation Series | Telecommunications and computer networking | |

| X2AP | Basic Aligned Packed Encoding Rules |

Encodings[edit]

ASN.1 is closely associated with a set of encoding rules that specify how to represent a data structure as a series of bytes. The standard ASN.1 encoding rules include:

| Encoding rules | Object identifier | Object descriptor value |

Specification |

Unit of serialization |

Encoded elements |

Octet aligned |

Encoding control |

Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dotted | IRI | ||||||||

| Basic Encoding Rules (BER)[4] | 2.1.1 | /ASN.1/Basic-Encoding | Basic Encoding of a single ASN.1 type | ITU X.690 | Octet | Yes | Yes | No | The first specified encoding rules. Encodes elements as tag-length-value (TLV) sequences. Typically provides several options as to how data values are to be encoded. This is one of the more flexible encoding rules. |

| Distinguished Encoding Rules (DER)[5] | 2.1.2.1 | /ASN.1/BER‑Derived/Distinguished‑Encoding | Distinguished encoding of a single ASN.1 type | ITU X.690 | Octet | Yes | Yes | No | A restricted subset of the Basic Encoding Rules (BER). Typically used for things that are digitally-signed because, since the DER allow for fewer options for encoding, and because DER-encoded values are more likely to be re-encoded on the exact same bytes, digital signatures produced by a given abstract value will be the same across implementations and digital signatures produced over DER-encoded data will be less susceptible to collision-based attacks. |

| Canonical Encoding Rules (CER)[6] | 2.1.2.0 | /ASN.1/BER‑Derived/Canonical‑Encoding | Canonical encoding of a single ASN.1 type | ITU X.690 | Octet | Yes | Yes | No | A restricted subset of the Basic Encoding Rules (BER). Employs almost all of the same restrictions as the Distinguished Encoding Rules (DER), but the noteworthy difference is that the CER specify that many large values (especially strings) are to be «chopped up» into individual substring elements at the 1000-byte or 1000-character mark (depending on the data type). |

| Basic Packed Encoding Rules (PER) Aligned[7] | 2.1.3.0.0 | /ASN.1/Packed‑Encoding/Basic/Aligned | Packed encoding of a single ASN.1 type (basic aligned) | ITU X.691 | Bit | No | Yes | No | Encodes values on bits, but if the bits encoded are not evenly divisible by eight, padding bits are added until an integral number of octets encode the value. Capable of producing very compact encodings, but at the expense of complexity, and the PER are highly dependent upon constraints placed on data types. |

| Basic Packed Encoding Rules (PER) Unaligned[7] | 2.1.3.0.1 | /ASN.1/Packed‑Encoding/Basic/Unaligned | Packed encoding of a single ASN.1 type (basic unaligned) | ITU X.691 | Bit | No | No | No | A variant of the Aligned Basic Packed Encoding Rules (PER), but it does not pad data values with bits to produce an integral number of octets. |

| Canonical Packed Encoding Rules (CPER) Aligned[7] | 2.1.3.1.0 | /ASN.1/Packed‑Encoding/Canonical/Aligned | Packed encoding of a single ASN.1 type (canonical aligned) | ITU X.691 | Bit | No | Yes | No | A variant of the Packed Encoding Rules (PER) that specifies a single way of encoding values. The Canonical Packed Encoding Rules have a similar relationship to the Packed Encoding Rules that the Distinguished Encoding Rules (DER) and the Canonical Encoding Rules (CER) have to the Basic Encoding Rules (BER). |

| Canonical Packed Encoding Rules (CPER) Unaligned[7] | 2.1.3.1.1 | /ASN.1/Packed‑Encoding/Canonical/Unaligned | Packed encoding of a single ASN.1 type (canonical unaligned) | ITU X.691 | Bit | No | No | No | A variant of the Aligned Canonical Packed Encoding Rules (CPER), but it does not pad data values with bits to produce an integral number of octets. |

| Basic XML Encoding Rules (XER)[8] | 2.1.5.0 | /ASN.1/XML‑Encoding/Basic | Basic XML encoding of a single ASN.1 type | ITU X.693 | Character | Yes | Yes | Yes | Encodes ASN.1 data as XML. |

| Canonical XML Encoding Rules (CXER)[8] | 2.1.5.1 | /ASN.1/XML‑Encoding/Canonical | Canonical XML encoding of a single ASN.1 type | ITU X.693 | Character | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Extended XML Encoding Rules (EXER)[8] | 2.1.5.2 | /ASN.1/XML‑Encoding/Extended | Extended XML encoding of a single ASN.1 type | ITU X.693 | Character | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Octet Encoding Rules (OER)[9] | 2.1.6.0 | Basic OER encoding of a single ASN.1 type | ITU X.696 | Octet | No | Yes | A set of encoding rules that encodes values on octets, but does not encode tags or length determinants like the Basic Encoding Rules (BER). Data values encoded using the Octet Encoding Rules often look like those found in «record-based» protocols. The Octet Encoding Rules (OER) were designed to be easy to implement and to produce encodings more compact than those produced by the Basic Encoding Rules (BER). In addition to reducing the effort of developing encoder/decoders, the use of OER can decrease bandwidth utilization (though not as much as the Packed Encoding Rules), save CPU cycles, and lower encoding/decoding latency. | ||

| Canonical Encoding Rules (OER)[9] | 2.1.6.1 | Canonical OER encoding of a single ASN.1 type | ITU X.696 | Octet | No | Yes | |||

| JSON Encoding Rules (JER)[10] | ITU X.697 | Character | Yes | Yes | Yes | Encodes ASN.1 data as JSON. | |||

| Generic String Encoding Rules (GSER)[11] | 1.2.36.79672281.0.0 | Generic String Encoding Rules (GSER) | RFC 3641 | Character | Yes | No | An incomplete specification for encoding rules that produce human-readable values. The purpose of GSER is to represent encoded data to the user or input data from the user, in a very straightforward format. GSER was originally designed for the Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP) and is rarely used outside of it. The use of GSER in actual protocols is discouraged since not all character string encodings supported by ASN.1 can be reproduced in it. | ||

| BACnet Encoding Rules | ASHRAE 135 | Octet | Yes | Yes | Yes | Encodes elements as tag-length-value (TLV) sequences like the Basic Encoding Rules (BER). | |||

| Signalling Specific Encoding Rules (SER) | France Telecom R&D Internal Document | Octet | Yes | Yes | Used primarily in telecommunications related protocols, such as GSM and SS7. Designed to produce an identical encoding from ASN.1 that previously-existing protocols not specified in ASN.1 would produce. | ||||

| Lightweight Encoding Rules (LWER) | Internal document by INRIA. | Memory Word | Yes | Originates from an internal document produced by INRIA detailing the «Flat Tree Light Weight Syntax» (FTLWS). Abandoned in 1997 due to the superior performance of the Packed Encoding Rules (PER). Optionally Big-Endian or Little-Endian transmission as well as 8-bit, 16-bit, and 32-bit memory words. (Therefore, there are six variants, since there are six combinations of those options.) | |||||

| Minimum Bit Encoding Rules (MBER) | Bit | Proposed in the 1980s. Meant to be as compact as possible, like the Packed Encoding Rules (PER). | |||||||

| NEMA Packed Encoding Rules | Bit | An incomplete encoding rule specification produced by NEMA. It is incomplete because it cannot encode and decode all ASN.1 data types. Compact like the Packed Encoding Rules (PER). | |||||||

| High Speed Coding Rules | «Coding Rules for High Speed Networks» | Definition of these encoding rules were a byproduct of INRIA’s work on the Flat Tree Light Weight Syntax (FTLWS). |

Encoding Control Notation[edit]

ASN.1 recommendations provide a number of predefined encoding rules. If none of the existing encoding rules are suitable, the Encoding Control Notation (ECN) provides a way for a user to define his or her own customized encoding rules.

Relation to Privacy-Enhanced Mail (PEM) Encoding[edit]

Privacy-Enhanced Mail (PEM) encoding is entirely unrelated to ASN.1 and its codecs, but encoded ASN.1 data, which is often binary, is often PEM-encoded so that it can be transmitted as textual data, e.g. over SMTP relays, or through copy/paste buffers.

Example[edit]

This is an example ASN.1 module defining the messages (data structures) of a fictitious Foo Protocol:

FooProtocol DEFINITIONS ::= BEGIN

FooQuestion ::= SEQUENCE {

trackingNumber INTEGER,

question IA5String

}

FooAnswer ::= SEQUENCE {

questionNumber INTEGER,

answer BOOLEAN

}

END

This could be a specification published by creators of Foo Protocol. Conversation flows, transaction interchanges, and states are not defined in ASN.1, but are left to other notations and textual description of the protocol.

Assuming a message that complies with the Foo Protocol and that will be sent to the receiving party, this particular message (protocol data unit (PDU)) is:

myQuestion FooQuestion ::= {

trackingNumber 5,

question "Anybody there?"

}

ASN.1 supports constraints on values and sizes, and extensibility. The above specification can be changed to

FooProtocol DEFINITIONS ::= BEGIN

FooQuestion ::= SEQUENCE {

trackingNumber INTEGER(0..199),

question IA5String

}

FooAnswer ::= SEQUENCE {

questionNumber INTEGER(10..20),

answer BOOLEAN

}

FooHistory ::= SEQUENCE {

questions SEQUENCE(SIZE(0..10)) OF FooQuestion,

answers SEQUENCE(SIZE(1..10)) OF FooAnswer,

anArray SEQUENCE(SIZE(100)) OF INTEGER(0..1000),

...

}

END

This change constrains trackingNumbers to have a value between 0 and 199 inclusive, and questionNumbers to have a value between 10 and 20 inclusive. The size of the questions array can be between 0 and 10 elements, with the answers array between 1 and 10 elements. The anArray field is a fixed length 100 element array of integers that must be in the range 0 to 1000. The ‘…’ extensibility marker means that the FooHistory message specification may have additional fields in future versions of the specification; systems compliant with one version should be able to receive and transmit transactions from a later version, though able to process only the fields specified in the earlier version. Good ASN.1 compilers will generate (in C, C++, Java, etc.) source code that will automatically check that transactions fall within these constraints. Transactions that violate the constraints should not be accepted from, or presented to, the application. Constraint management in this layer significantly simplifies protocol specification because the applications will be protected from constraint violations, reducing risk and cost.

To send the myQuestion message through the network, the message is serialized (encoded) as a series of bytes using one of the encoding rules. The Foo protocol specification should explicitly name one set of encoding rules to use, so that users of the Foo protocol know which one they should use and expect.

Example encoded in DER[edit]

Below is the data structure shown above as myQuestion encoded in DER format (all numbers are in hexadecimal):

30 13 02 01 05 16 0e 41 6e 79 62 6f 64 79 20 74 68 65 72 65 3f

DER is a type–length–value encoding, so the sequence above can be interpreted, with reference to the standard SEQUENCE, INTEGER, and IA5String types, as follows:

30 — type tag indicating SEQUENCE

13 — length in octets of value that follows

02 — type tag indicating INTEGER

01 — length in octets of value that follows

05 — value (5)

16 — type tag indicating IA5String

(IA5 means the full 7-bit ISO 646 set, including variants,

but is generally US-ASCII)

0e — length in octets of value that follows

41 6e 79 62 6f 64 79 20 74 68 65 72 65 3f — value ("Anybody there?")

Example encoded in XER[edit]

Alternatively, it is possible to encode the same ASN.1 data structure with XML Encoding Rules (XER) to achieve greater human readability «over the wire». It would then appear as the following 108 octets, (space count includes the spaces used for indentation):

<FooQuestion> <trackingNumber>5</trackingNumber> <question>Anybody there?</question> </FooQuestion>

Example encoded in PER (unaligned)[edit]

Alternatively, if Packed Encoding Rules are employed, the following 122 bits (16 octets amount to 128 bits, but here only 122 bits carry information and the last 6 bits are merely padding) will be produced:

01 05 0e 83 bb ce 2d f9 3c a0 e9 a3 2f 2c af c0

In this format, type tags for the required elements are not encoded, so it cannot be parsed without knowing the expected schemas used to encode. Additionally, the bytes for the value of the IA5String are packed using 7-bit units instead of 8-bit units, because the encoder knows that encoding an IA5String byte value requires only 7 bits. However the length bytes are still encoded here, even for the first integer tag 01 (but a PER packer could also omit it if it knows that the allowed value range fits on 8 bits, and it could even compact the single value byte 05 with less than 8 bits, if it knows that allowed values can only fit in a smaller range).

The last 6 bits in the encoded PER are padded with null bits in the 6 least significant bits of the last byte c0 : these extra bits may not be transmitted or used for encoding something else if this sequence is inserted as a part of a longer unaligned PER sequence.

This means that unaligned PER data is essentially an ordered stream of bits, and not an ordered stream of bytes like with aligned PER, and that it will be a bit more complex to decode by software on usual processors because it will require additional contextual bit-shifting and masking and not direct byte addressing (but the same remark would be true with modern processors and memory/storage units whose minimum addressable unit is larger than 1 octet). However modern processors and signal processors include hardware support for fast internal decoding of bit streams with automatic handling of computing units that are crossing the boundaries of addressable storage units (this is needed for efficient processing in data codecs for compression/decompression or with some encryption/decryption algorithms).

If alignment on octet boundaries was required, an aligned PER encoder would produce:

01 05 0e 41 6e 79 62 6f 64 79 20 74 68 65 72 65 3f

(in this case, each octet is padded individually with null bits on their unused most significant bits).

Tools[edit]

Most of the tools supporting ASN.1 do the following:

- parse the ASN.1 files,

- generates the equivalent declaration in a programming language (like C or C++),

- generates the encoding and decoding functions based on the previous declarations.

A list of tools supporting ASN.1 can be found on the ITU-T Tool web page.

Online tools[edit]

- ASN1 Web Tool (very limited)

- ASN1 Playground (sandbox)

Comparison to similar schemes[edit]

ASN.1 is similar in purpose and use to protocol buffers and Apache Thrift, which are also interface description languages for cross-platform data serialization. Like those languages, it has a schema (in ASN.1, called a «module»), and a set of encodings, typically type–length–value encodings. Unlike them, ASN.1 does not provide a single and readily usable open-source implementation, and is published as a specification to be implemented by third-party vendors. However, ASN.1, defined in 1984, predates them by many years. It also includes a wider variety of basic data types, some of which are obsolete, and has more options for extensibility. A single ASN.1 message can include data from multiple modules defined in multiple standards, even standards defined years apart.

ASN.1 also includes built-in support for constraints on values and sizes. For instance, a module can specify an integer field that must be in the range 0 to 100. The length of a sequence of values (an array) can also be specified, either as a fixed length or a range of permitted lengths. Constraints can also be specified as logical combinations of sets of basic constraints.

Values used as constraints can either be literals used in the PDU specification, or ASN.1 values specified elsewhere in the schema file. Some ASN.1 tools will make these ASN.1 values available to programmers in the generated source code. Used as constants for the protocol being defined, developers can use these in the protocol’s logic implementation. Thus all the PDUs and protocol constants can be defined in the schema, and all implementations of the protocol in any supported language draw upon those values. This avoids the need for developers to hand code protocol constants in their implementation’s source code. This significantly aids protocol development; the protocol’s constants can be altered in the ASN.1 schema and all implementations are updated simply by recompiling, promoting a rapid and low risk development cycle.

If the ASN.1 tools properly implement constraints checking in the generated source code, this acts to automatically validate protocol data during program operation. Generally ASN.1 tools will include constraints checking into the generated serialization / deserialization routines, raising errors or exceptions if out-of-bounds data is encountered. It is complex to implement all aspects of ASN.1 constraints in an ASN.1 compiler. Not all tools support the full range of possible constraints expressions. XML schema and JSON schema both support similar constraints concepts. Tool support for constraints varies. Microsoft’s xsd.exe compiler ignores them.

ASN.1 is visually similar to Augmented Backus-Naur form (ABNF), which is used to define many Internet protocols like HTTP and SMTP. However, in practice they are quite different: ASN.1 defines a data structure, which can be encoded in various ways (e.g. JSON, XML, binary). ABNF, on the other hand, defines the encoding («syntax») at the same time it defines the data structure («semantics»). ABNF tends to be used more frequently for defining textual, human-readable protocols, and generally is not used to define type–length–value encodings.

Many programming languages define language-specific serialization formats. For instance, Python’s «pickle» module and Ruby’s «Marshal» module. These formats are generally language specific. They also don’t require a schema, which makes them easier to use in ad hoc storage scenarios, but inappropriate for communications protocols.

JSON and XML similarly do not require a schema, making them easy to use. They are also both cross-platform standards that are broadly popular for communications protocols, particularly when combined with a JSON schema or XML schema.

Some ASN.1 tools are able to translate between ASN.1 and XML schema (XSD). The translation is standardised by the ITU. This makes it possible for a protocol to be defined in ASN.1, and also automatically in XSD. Thus it is possible (though perhaps ill-advised) to have in a project an XSD schema being compiled by ASN.1 tools producing source code that serializes objects to/from JSON wireformat. A more practical use is to permit other sub-projects to consume an XSD schema instead of an ASN.1 schema, perhaps suiting tools availability for the sub-projects language of choice, with XER used as the protocol wireformat.

For more detail, see Comparison of data serialization formats.

See also[edit]

- X.690

- Information Object Class (ASN.1)

- Presentation layer

References[edit]

- ^ «Introduction to ASN.1». ITU. Archived from the original on 2021-04-09. Retrieved 2021-04-09.

- ^ «ITU-T Recommendation database». ITU. Retrieved 2017-03-06.

- ^ ITU-T X.680 — Specification of basic notation

- ^ ITU-T X.690 — Basic Encoding Rules (BER)

- ^ ITU-T X.690 — Distinguished Encoding Rules (DER)

- ^ ITU-T X.690 — Canonical Encoding Rules (CER)

- ^ a b c d ITU-T X.691 — Packed Encoding Rules (PER)

- ^ a b c ITU-T X.693 — XML Encoding Rules (XER)

- ^ a b ITU-T X.696 — Octet Encoding Rules (OER)

- ^ ITU-T X.697 — JavaScript Object Notation Encoding Rules (JER)

- ^ RFC 3641 — Generic String Encoding Rules (GSER)

External links[edit]

- A Layman’s Guide to a Subset of ASN.1, BER, and DER A good introduction for beginners

- ITU-T website — Introduction to ASN.1

- A video introduction to ASN.1

- ASN.1 Tutorial Tutorial on basic ASN.1 concepts

- ASN.1 Tutorial Tutorial on ASN.1

- An open-source ASN.1->C++ compiler; Includes some ASN.1 specs., An on-line ASN.1->C++ Compiler

- ASN.1 decoder Allows decoding ASN.1 encoded messages into XML output.

- ASN.1 syntax checker and encoder/decoder Checks the syntax of an ASN.1 schema and encodes/decodes messages.

- ASN.1 encoder/decoder of 3GPP messages Encodes/decodes ASN.1 3GPP messages and allows easy editing of these messages.

- Free books about ASN.1

- List of ASN.1 tools at IvmaiAsn project

- Overview of the Octet Encoding Rules (OER)

- Overview of the JSON Encoding Rules (JER)

- A Typescript node utility to parse and validate ASN.1 messages

1 пользователь поблагодарил Максим Коллегин за этот пост.

1 пользователь поблагодарил Максим Коллегин за этот пост.